#animal communication

Text

These Parrots Won’t Stop Swearing. Will They Learn to Behave—or Corrupt the Entire Flock?

A British zoo hopes the good manners of a larger group will rub off on the eight misbehaving birds

A few years ago, a zoo in Britain went viral for its five foul-mouthed parrots that wouldn’t stop swearing. Now, three more birds at Lincolnshire Wildlife Park have developed the same bad habit—and zoo staffers have devised a risky plan to curb their bad behavior.

“We’ve put eight really, really offensive, swearing parrots with 92 non-swearing ones,” Steve Nichols, the park’s chief executive, tells CNN’s Issy Ronald...

#parrot#zoos#bird#ornithology#animal behavior#animal communication#nature#animal intelligence#science

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

2023 commissions reservation list is officially OPEN!

-> http://tinyurl.com/5n7nsx94 <-

Please read carefully all the informations included in the form. If you have any questions don't hestitate to ask!

#pet commissions#animal commission#commissions open#commissions#animal communication#posterdesign#wildlife drawing#feline art#canineart#bird illustration#fantasy illustration#commission open

527 notes

·

View notes

Text

Scientists figured out chimpanzees have a rudimentary language by pranking them with snakes 🧑🏼🔬🐒🐍🙈

Want an awesome book about how primates communicate and see the world? Check out Baboon metaphysics:

140 notes

·

View notes

Text

Across human cultures and languages, adults talk to babies in a very particular way. They raise their pitch and broaden its range, while also shortening and repeating their utterances; the latter features occur even in sign language. Mothers use this exaggerated and musical style of speech (which is sometimes called “motherese”), but so do fathers, older children, and other caregivers. Infants prefer listening to it, which might help them bond with adults and learn language faster.

But to truly understand what baby talk is for, and how it evolved, we need to know which other animals use it, if any. The great apes don’t seem to vocally, but might use a gestural equivalent. Squirrel monkeys and rhesus macaques use special calls when talking to youngsters, but they’re very different from human baby talk, which is a modified version of normal speech. Zebra finches are closer to us: When singing in front of juveniles, adults add longer pauses between musical phrases and repeat introductory notes. Greater sac-winged bat mothers also change their pitch and timbre when signaling to pups, but again, it’s hard to tell if they’re using a distinct call or doing something analogous to baby talk. To make an inarguable case for the latter, you’d need to study a species that talks with both infants and older peers using the same standardized, identifiable call. In other words, you’d need a dolphin.

Every bottlenose dolphin produces its own unique signature whistle, which is the closest thing any animal has to a human name. Dolphins can recognize individuals through these whistles and will sometimes copy one another’s, perhaps as a form of address. They use their whistles frequently, to announce their position when separated from their pod, or as an introduction when meeting up with new groups. Calves develop their own signature whistles based on those they hear around them, and once learned, the whistles can go unchanged for at least 12 years.

Laela Sayigh, a zoologist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, has been studying the signature whistles of bottlenoses in Sarasota Bay, Florida, since 1986 as part of the world’s longest-running study of wild dolphins. She and her colleagues regularly catch these animals, check their health, and record their calls before releasing them. Sometimes, they catch mothers and calves together, and the animals exchange signature whistles throughout the process. By analysing 19 such moments, recorded over 34 years, Sayigh’s student Nicole El Haddad showed that mothers raised and widened the pitch of their signature whistles when calling to their calves, just as humans do when talking to their babies.

“We were just blown away by how consistent the effect was,” Sayigh told me. Between their intelligence and strong personality, dolphins behave unpredictably enough that scientists who study them are used to gleaning faint patterns amid messy data. But in this study, every mom changed its signature whistle around its calf in the same way. “The data are extraordinary and impressive,” Sabine Stoll, who studies language evolution at the University of Zurich, told me.

Dolphin baby talk isn’t exactly the same as ours—dolphin whistles don’t get more repetitive—but it’s certainly “the most convincing case of child-directed communication found in nonhuman animals to date,” Mirjam Knörnschild from the Museum of Natural History in Berlin, who led the study on sac-winged bats, told me. And its existence in a species separated from us by more than 90 million years of history is likely a “stunning” example of convergent evolution, Stoll said.

If both species evolved baby talk independently, perhaps they did so for similar reasons. Human parents can better grab their infants’ attention through high-pitched baby talk than through normal speech, and dolphin mothers might do the same. Keeping her signature whistle but raising its pitch “would be a pretty foolproof way for the mom to say ‘This whistle is meant for you’ to the calf, and for the calf to know My mom is talking to me right now and no one else,” Sayigh said. That specificity would allow both of them to keep close contact in a raucous ocean where many dolphins might be sounding off at once.

Human baby talk is also thought to strengthen a baby’s bond with its caregivers, and to help it learn language by exaggerating important features of the spoken word. The same could well apply to dolphins, which also stay with their mother for a long time, and learn calls by listening to their peers. But testing these ideas would be incredibly hard without separating mothers and their calves—an experiment that Sayigh said would cross an ethical line. She showed that dolphin baby talk exists; its exact role “is just one of those things that might have to go unanswered,” she said.

#zoology#animals#animal behaviour#ethology#bioacoustics#animal communication#psychology#child psychology#child development#dolphins

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tripping on LSD at the Dolphin Research Lab

How a 1960s interspecies-communication experiment went haywire.

by Benjamin Breen

In the 1930s, the married anthropologists Gregory Bateson and Margaret Mead had seen themselves as scientists seeking to expand the accepted limits of “normal” human behavior, communication, and consciousness. By the 1940s they came to believe that their project could help ensure the survival of humanity itself, threatened as it was by the spread of fascism and the advent of atomic warfare. They regarded both as a product of “pathogenic” cultural patterns — ideas that drive you insane.

By 1963 Bateson and Mead were divorced. But Bateson continued to see himself as pushing the boundaries of science to prevent feedback loops of conflict, which led him to the psychoanalyst John C. Lilly’s Communications Research Institute on St. Thomas in the U.S. Virgin Islands. By then Lilly’s professional résumé was impeccable: degrees from Caltech and Dartmouth, a stint teaching at Penn, previously the head of a government research lab at the NIH, and now running his own lavishly funded institute. Moreover, for reasons that remained somewhat mysterious, he had managed to persuade NASA to fund his efforts to teach dolphins how to speak English.

READ MORE

5 notes

·

View notes

Quote

I remember I had this plant. From this plant, these little people came. They would visit me and they would tell me where to hide when my uncle was drinking or I sensed that something's going to happen or that he would try to kill me. It happened many times. But my guides, the little people, they would tell me; 'Go hide in the barn. Do this. Rush here. Go to this person.' I wasn't scared. I was always guided; 'You have to hide here. You have to go this way'. Animals would hide me (too). They would tell me; 'Come here'.

I felt grateful. I feel grateful for this now. I didn't realize it was something extraordinary. I thought it was a normal thing.

Akerke Muratova’s Pre-birth Memories and other spiritual experiences as a child (source)

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cats have nearly 300 facial expressions, including a 'play face' they share with humans

Researchers recorded hundreds of facial expressions in cats, finding they're not quite as aloof as previously thought.

Over the course of a year, researchers recorded a total of 276 distinct facial expressions used among a colony of 50 cats living at a cat cafe in Los Angeles. The felines' faces ranged from playful to aggressive and everything in between, according to the study, published Oct. 18 in the journal Behavioural Processes.

This is one of the first studies to do a deep dive into the ways felines communicate beyond the obvious purring and meowing.

5 notes

·

View notes

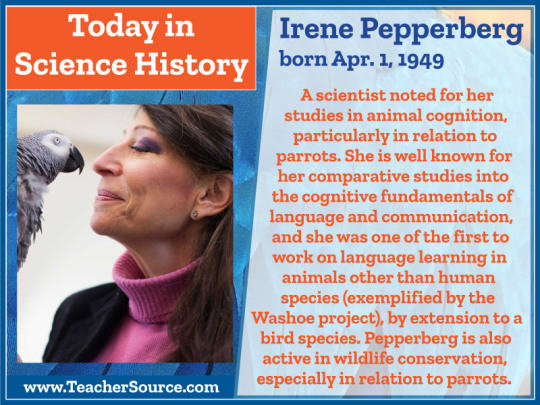

Photo

Irene Pepperberg was born on April 1, 1949. A scientist noted for her studies in animal cognition, particularly in relation to parrots. She is well known for her comparative studies into the cognitive fundamentals of language and communication, and she was one of the first to work on language learning in animals other than human species (exemplified by the Washoe project), by extension to a bird species. Pepperberg is also active in wildlife conservation, especially in relation to parrots.

#irene pepperberg#animal cognition#animal communication#animal behavior#parrots#wildlife conservation#science#science history#science birthdays#on this day#on this day in science history#women in science#women in history

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

“This animal hit me for no reason omg” *was upsetting the animal, over petting, teasing, crossing boundaries, ignoring stop signs, making the animal uncomfortable*

#animals#animal studies#animal welfare#animal wellbeing#animal care#animal communication#cat scratches

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Let’s talk about: Discovering Your Spirit Animals

Spirit animals are one of my favorite things about awakening. Finding yours and understanding how to interpret animal interactions can lend you important knowledge about your path and what areas you need to address.

Be sure to check out my post on animal communication

Spirit Animal Totems

So totem animals are animals that are connected to you throughout your life and they represent a deep connection to who you are in this life. They may also be used as messengers from your spirit team or have a connection to one of your past lives. Usually you discover this animal during a time of awakening and you recognize them as a messenger because you get an almost eerie feeling when you see them, in that it feels different from merely seeing an animal. If you call to them, you may notice that they show up. Before big moments you may find they show up as a sign of encouragement or warning. You can have multiple totem animals, but again the main thing is that they align with who you are.

My totem animal is the crow. The crow not only ties into my native ancestry but also has qualities that align with me. I found out the crow was my spirit totem animal after my grandmother died and they flew outside my bedroom window where I’d never seen crows there before. I asked them if they had a message for me to speak and they cawed. Later on, crows also showed up to warn me before my friends car blew out on the highway. Throughout my life, these birds show up to remind me I’m not alone and that I always have access to my magic.

Messenger animals

Although totem animals can serve as messengers, other animals can also serve as messengers. These are animals that seem to demand being in your presence but are animals you don’t see often. Again, for me, I can tell because there is a certain energy I feel. I don’t know the best word for it but it’s a deep knowing. These animals show up very strongly and randomly.

An example, my sister and I went to public park once a few months back and saw over 30 of them! Just put in the open. I was like damn, okay, message received. I do think they were more for her but that’s an example of them showing up. Recently for me, I went on an excursion and I had to cross over water. Someone with me told me right as I was crossing a sea turtle swam beneath me. I also noticed this when I crossed over the second time. Swimming very close to me like I could almost touch it. It wanted to get out and rest on the rock I was jumping to. I immediately looked up the turtle meaning after.

Messenger animals can also show up strongly in visions or dreams. Only you can determine what animals are totems, long term animal messengers and more one off messengers.

Resources:

What is my spiritual animal

Spirit Animal

#spiritual insight#spiritual guidance#spiritual journey#spiritualawareness#spiritual evolution#spirituality#spiritual awakening#awakening#spirit animals#animal totem#messenger animal#animal communication#animal communicator#black crows#crows#sea turtle#golden deers#long post#animals#spiritual gifts#spiritual power

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

The more we learn about elephants, the more we discover what complex inner lives they have!

This article discusses how elephants have complex communities with distinct traditions, including how they communicate:

Want to learn more about elephant communication? Check out Beyond words: What animals think and feel, about the science of animal behavior.

62 notes

·

View notes

Quote

No matter how much we love Hope and Winter they are wild animals.

Sawyer, Dolphin Tale 2 (2014)

#dolphin tale#dolphin tale 2#winter#dolphins#wild animals#hope#2014#animallovers#disabledanimals#animalrights#movie quote of the day#quotes#based on a true story#animal companions#animal communication

12 notes

·

View notes

Link

Fascinating article, written by someone who is not stupid about language...

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s a crisp fall evening in Grand Teton National Park. A mournful, groaning call cuts through the dusky-blue light: a male elk, bugling. The sound ricochets across the grassy meadow. A minute later, another bull answers from somewhere in the shadows.

Bugles are the telltale sound of elk during mating season. Now new research has found that male elks’ bugles sound slightly different depending on where they live. Other studies have shown that whale, bat, and bird calls have dialects of sorts too, and a team led by Jennifer Clarke, a behavioral ecologist at the Center for Wildlife Studies and a professor at the University of La Verne, in California, is the first to identify such differences in any species of ungulate.

Hearing elk bugle in Rocky Mountain National Park decades ago inspired Clarke to investigate the sound. “My graduate students and I started delving into the library and could find nothing on elk communication, period,” she says. That surprised her: “Thousands of people go to national parks to hear them bugle, and we don’t know what we’re listening to.”

Her research, published earlier this year in the Journal of Mammalogy, dug into the unique symphony created by different elk herds. Although most people can detect human dialects and accents—a honey-thick southern drawl versus nasal New England speech—differences in regional elk bugles are almost imperceptible to human ears. But by using spectrograms to visually represent sound frequencies, researchers can see the details of each region’s signature bugles. “It’s like handwriting,” Clarke says. “You can recognize Bill’s handwriting from George’s handwriting.”

Pennsylvania’s elk herds were translocated from the West in the early 1900s, and today, they have longer tonal whistles and quieter bugles than elk in Colorado. Meanwhile, bugles change frequency from low to high tones more sharply in Wyoming than they do in Pennsylvania or Colorado.

Clarke isn’t sure why the dialects vary. She initially hypothesized that calls would differ based on the way sound travels in Pennsylvania’s dense forests compared with the more open landscapes of Colorado and Wyoming, but her data didn’t support that theory. Clarke hopes to find out whether genetic variation—which is more limited in Pennsylvania’s herd—might explain differences in bugles, and whether those differences are learned by young males listening to older bulls.

Clarke’s research adds a small piece to the larger puzzle of animal communication, says Daniel Blumstein, a biologist at UCLA who was not involved in the study. “It’s not as though a song or vocal learning is ‘all environmental’ or ‘all genetic,’” he says. “It’s an interplay between both.” Blumstein, a marmot-communication researcher, adds that the mechanisms behind these vocal variations deserve more study.

These unanswered questions are part of the larger field of bioacoustics, which blends biology and acoustics to deepen our understanding of the noises that surround us in nature. Bioacoustics can sometimes be used as a conservation tool to monitor animal behavior, and other studies are shedding light on how it affects animal evolution, disease transfer, and cognition.

Elk are not the only species with regional dialects. In North America, eastern and western hermit thrushes sing different song structures, and the white-crowned sparrow’s song can help ornithologists identify where it was born. Campbell’s monkeys also have localized dialects in their songs and calls, as does the rock hyrax, a mammal that looks like a rodent but is actually related to elephants.

Similar differences exist underwater, where whale songs have unique phrases that vary by location. Sperm whales in the Caribbean have clicking patterns in their calls that differ from those of their Pacific Ocean counterparts. Orcas in Puget Sound use distinctive clicks and whistles within their own pods.

Clarke also studies the vocalizations of ptarmigan, flying foxes, and Tasmanian devils. Her next research project will shed light on how bison mothers lead their herds and communicate with their calves. “They’re the heart of the herd,” she says. “What are they talking about?”

3 notes

·

View notes