#and yes even being an internationalist

Text

Some Musings on Avoiding Empire (OLD ESSAY)

This essay was originally posted on July 14th, 2021.

In this essay, I continue my musings on how a democratic socialist state engages in warfare in support of like-minded allies and partners and peoples across the world without falling into the trap of becoming the same as the empires it wishes to both forsake and combat. I don't pretend to have the answers completely, but I at least try to get the ball rolling.

(Full essay under the cut).

When I first started writing these essays, the earliest topics that I covered – and the ones that I keep returning to consistently throughout the overall thread of my work – is that a.) war isn’t going anywhere, and b.) it’s something that we need to understand and be prepared for on the left, even under a different system to the one we live under now. To that end, I’ve talked about the circumstances under which it may be necessary for us to go to war.

However – disregarding those who are acting in bad faith or have ulterior motives – there are still many people who have justifiable misgivings about the idea of the United States or any great power or superpower using force, even under a hypothetically more just governing system and even if it is defendable as the right thing to do under specific circumstances. I’ve had a number of conversations with friends on this topic, which has come up sporadically as various events and crises unfold in the world and the topic of outside intervention invariably arise. While I hold a different view, I can understand why some folks may be suspicious of or hesitant to suddenly get behind the idea of a powerful state notionally using its military power for “good” – especially those who live in other countries and have had to live at the whims of U.S. foreign policy or that of other foreign powers. To some, it may simply seem like empire under a different name.

That raises a question that I felt was worth an essay in its own right: in that hypothetical future I try to think about from getting too bummed out with the present, how do you conduct a global foreign and defense policy without being an empire? While I don’t think the idea of a changed-United States or any country using military power in a more just fashion is equivalent to empire in its own right, I feel like the danger of backsliding into imperialistic attitudes is still very much present and a danger. I see how it could be very easy to make a poor decision here, an exception there, and end up doing the same sort of foreign policy that got us where we are today.

After spending some time pondering this, I’ve come up with an extremely non-scientific, purely vibes-based set of principles that – while I make no claims towards being definitive, exhaustive, or foolproof – seem like a good starting point for how to carry out the kinds of concepts I rail on about without just being what we currently have and have had before but in a different guise. Those four principles, which I will go into more detail on each below, include: being selective of allies and partners, respecting countries’ consent, promoting countries’ self-sufficiency, and maintaining a minimal international footprint. Some or all of these may seem obvious to some, but I’ve found in this day and age, I can’t take anything like this for granted. So, let us begin.

1. Being Selective of Allies and Partners

To be a good leftist or socialist or however you label yourself, one almost by definition needs to be a good internationalist. You should care not only about improving the lives of everyone in your own community, city or country, but also about improving the lives of all people, everywhere. Thus, part of this naturally should entail establishing partnerships and forging alliances with countries that are similarly inclined in order to defend one another from hostile forces and to continue to try and improve things the world over (yes I realize this may sound a bit sappy and idealistic as I type this out, especially in the current environment, but I have to believe that something like this is achievable and that life is not endless sorrow and agony).

Note, that the key terms here are finding allies in countries that have similar principles, those principles of course being things like a democratic system of government, freedom of expression, freedom of the press, a legal and judicial system that isn’t draconian and doesn’t grind a bootheel into the neck of its citizens, supporting said citizens from want and deprivation, etc. etc. All that good stuff that we’re into, and that some governments claim they’re about.

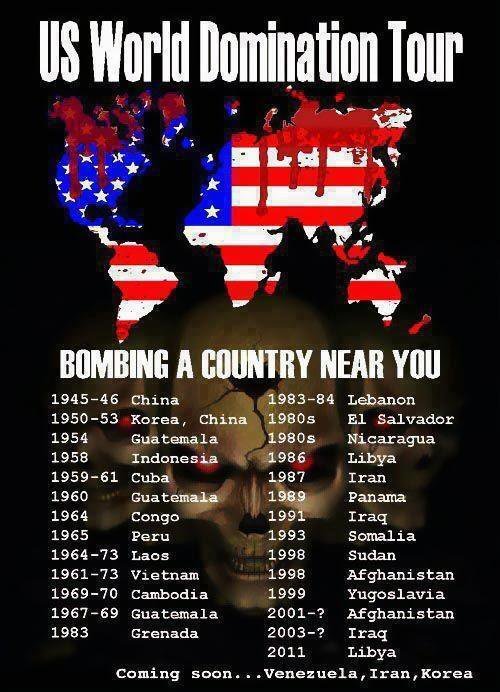

When you look back at the history of the United States and other great powers from the past, you’ll find that the track record of finding allies based on these principles is “spotty” if I’m going to be charitable. The Cold War is an excellent example of this. When the United States searched for partners across the globe in its competition against the Soviet Union, its criteria were more about whether or not governments or leaders opposed communism rather than sharing any sort of affinity towards the principles that the United States claimed to value. What this resulted in was the United States supporting or installing regimes that were extremely right-wing or even fascistic purely on the basis of them hating communism (or any form of leftism) and doing everything they could to oppose it – including mass oppression, imprisonment, and murder of their own citizens. From Latin America, to Africa, to the Middle East and the Far East, you’d be hard pressed to find an area where the United States didn’t support a questionable regime in the course of great power politics.

This practice found new life to a different ideological end following the September 11th Attacks and the outbreak of the Global War on Terrorism. This time, the enemy wasn’t communism, but Islamic fundamentalist terrorism. If the United States wasn’t choosy about its allies during the Cold War, it was even less so in finding allies and partners to help it fight al Qaeda and similar groups – some of which were about just as bad as al Qaeda, had a role in its formation, or were even actively supporting them or other similarly minded or aligned groups like the Taliban.

This is a very long-winded way of me saying, in the future, if we want to conduct ourselves justly in the world of international relations, it means thinking critically about who our friends are. This is a problem that not only conservatives and liberals have, but far too many people on the left have when it comes to uncritically supporting unabashedly authoritarian regimes just because they’re aesthetically leftist or just anti-American. If we don’t want to be morally bankrupt to our own beliefs, then we’ll have to take a long, hard look at any country we consider as an ally and about whether aligning ourselves to them is the right thing to do, or something we’re doing purely out of self-interest or for political or ideological street cred.

2. Respecting the Consent of Other Countries

Our being more selective of allies and partners based on our principles and beliefs is only one part of the equation when it comes to working with other countries throughout the world. The flip side to aligning ourselves to countries more in sync with what we believe, is also realizing that countries and their populaces may not always necessarily want to be our ally, even if we think they have much in common with us and we’d like to help them. As with many other things in life, the magic word here is consent. If a country and its people do not consent to accepting help from us, then forcing the issue is simply adopting a paternal or imperialistic attitude.

There may be a myriad of reasons for this. Part of it may be the suspicion and wariness that I spoke of earlier, which may take generations to pass for some – or may potentially never pass for others. But there may be other reasons as well. The reasons matter less though, then what a country – but more importantly, its people – want. At the end of the day, if a government does not want anything to do with us or any other country offering help, and this is a genuine reflection of the will of its people as a whole, then that’s that. Unless they change their mind at some point in the future, any further efforts are simply trying to unjustly impose your will on another country – the very thing we’re supposed to be trying to avoid.

This same sort of logic applies to supporting movements seeking liberation, whether they are trying to establish an independent state for their people, or to overthrow a government that is oppressing them. Even if we have much in common with the principles of a liberation movement and want to help them, if they want nothing to do with us, we really have nothing else we can do other than cheer them on and wish for the best and hope maybe they change their minds. If I’ve found one thing out from being active on the internet as an artist and writer for most of my adult life, it’s that you can’t force people to be you friends. Sometimes, things just don’t ‘click’ from one end, and you just have to accept you’ll never be as close as you’d like things to be. Sometimes people may warm up to you over time or under different circumstances, but the key thing is that’s up to them, not you. In my eyes, the same thing applies to this case.

Now, I feel like there are potentially exceptions here. One big one that comes to mind is when humanitarian intervention comes up, such as intervention to provide aid to a starving populace or to stop the genocide of a group of people by a state – something behind the basis of the United Nations concept of Responsibility to Protect (something that is invoked far too little in my opinion). These are cases where you can strongly argue that its acceptable to intervene without a request for help – or that it is actually necessary to do so in order to prevent further death and destruction. That all being said, I also think if you look back through history, you’ll be very hard pressed to find any situation where a people were being brutally massacred or were starving to death and were flatly refusing any assistance and aid rather than begging any country with the means to do so to save them from being wiped out. But I felt I should bring that one up regardless just for the sake of being intellectually honest on the issue of consent.

We see the repercussions of ignoring the idea of consent across twenty years of Forever War, in particular Afghanistan and Iraq. While the United States may have initially been welcomed as liberators in both countries and both the Taliban in Afghanistan and Ba’athist state in Iraq were objectively terrible regimes, at the end of the day there was no genuine, country-wide mass movements or representatives of said movements requesting that the United States aid them in their liberation. Our invasions of those countries were forced on them from the outside, and that is part of why they were doomed to failure from the start – as most regime changes are.

3. Promoting Self-Sufficiency

Throughout the modern era, great powers have lavished military aid and arms sales upon allies and partners that suited them. Such aid could be made under the claims of ensuring that country’s ability to defend itself or being out of some notion of brotherhood and comradeship. Of course, like so many things, this aid is also about the game of great power politics and serves just as much as an instrument of influence and control as it did as a means of self-defense – if not more. As much great powers have an interest in ensuring certain countries could defend themselves and their regimes, they also had a vested interest – for many reasons – in making sure said countries were dependent upon them in some shape or form for defense.

There are some glaring examples of this seeding of dependence in how the United States provides military aid or sells arms to other countries currently, especially in an age of more complicated and technologically sophisticated weapons. Often the United States provides arms and armaments to an ally or partner without going through the effort of teaching and enabling them how to maintain them. Instead, it will simply employ contractors or even U.S. military personnel to maintain the equipment for the country, meaning that country is dependent upon the U.S. and U.S. companies (who also naturally have a vested interest in continuing to make money from servicing said equipment) for their defense – putting them in a precarious position.

Under a more just system, the intent of such aid prior to a conflict actually breaking out, would be the exact opposite. The primary purpose of our support to a country in bolstering its defense should be to make it self-sufficient as possible in its own defense, so that it will only need outside help under the most dire of circumstances. We should be genuinely trying to help a country stand on its two feet and not be beholden to any outside power for its survival (and this should be the case in general with all things, though obviously I’m focusing on defense and the military here as that is my wheelhouse and the focus of this blog, but felt it needed calling out). This would mean not only providing arms to a country, but also teaching them how to maintain them, helping them build the means to maintain them domestically, or even setting up their own domestic ability to produce weapons and material, and more – if they are able to do so.

The old adage goes that if you love something, set it free. Well, if we truly care about the well-being of an ally, then we should be building them up so that at the end of the day, they either don’t need us at all or only need us when things get really bad. If we treat them well and help them earnestly and in good faith, then even when they don’t need us, they will want to stand alongside us in defense of the same, shared ideas and belief. Likewise, we’ll have made that community of like-minded peoples and governments stronger by increasing the overall ability to defend itself as a whole against hostile, reactionary forces.

4. Maintaining a Minimal Footprint

One of the aspects of U.S. imperial attitudes that is brought up much on the left is the expansive, worldwide U.S. military presence. The United States maintains bases and troops to varying degrees in a wide swath of countries across the globe – around 40% of the world’s countries in 2019. These bases can serve as a point of serious contention even in countries where their presence is more welcome or at least not reviled. Even if they are not significantly or directly affecting the country they are located in, overseas bases are a lightning rod for their role in perpetuating conflict and U.S. imperialism. As a result, what I often have heard on the left is a desire for the United States to vacate all of its overseas military bases and bring all of its troops back home. While I completely understand this desire and empathize with it, I also feel it is unrealistic if in the future we want to be anything other than isolationist and inward looking – something that is incompatible with the very idea of socialism.

Contemporary warfare is a fast-moving endeavor, under which reacting quickly can mean the difference between victory and defeat – as well as how much destruction is visited and how many lives are lost. Even if we wish to spurn being an imperial power, if we want to be in any position to help other countries that come under attack by an aggressor and are unable to defend themselves on their own and request assistance, we need to be able to react swiftly so that our solidarity doesn’t end up coming too late to be of any help to those under attack. Having a military that can rapidly deploy, rather than be permanently or semi-permanently forward-deployed – may actually deter potential conflict better anyway.

Of course, rapid deployment of forces this still means crossing vast distances of time and space to get to wherever an ally may be in danger. So, in my typical wishy-washy, “enlightened centrist leftist” fashion, I advocate there has to be some kind of middle ground. If we want to be of any help to allies and partners but still avoid empire, any overseas military installations we maintain need to be kept to a bare minimum. They need to be limited only to what we think we really need. What we “need” should be based on doing actual analysis and assessment of what our stated national security goals are, who are allies and partners are that we anticipate we may need to come to the aid of, where they are located, and etc. It basically just requires us going through the effort of thinking critically about what we need to do what we think is important and in line with our principles and not just gobbling up bases left and right in order to further our own power, influence, control as an imperial power does.

This can’t account for every instance, of course. There may be a case when we need to come to the aid of a country or group that we did not anticipate. This is just a risk you run when planning for various scenarios of war. You set yourself up to be ready for the most likely cases, and then when the least likely or unexpected ones occur, you make do best you can. In those instances, we may be able to lease bases or request temporary access for the duration of a campaign from a third country along the way to the operational area – packing up and going home ASAP once our (hopefully) very clearly defined objectives have been completed.

With that in mind, we should be viewing these bases as being temporal in general. None of them should be thought of as “permanent.” We should be planning out our needs with the idea that they will change over time. We should be reassessing on a regular basis as to what ones we still need, based on the abilities of our allies and partners, the various threats we face, and so on. Over time, it may make more sense to leave one base and set up shop somewhere else. Not only does it make good strategic sense, but it also aids in avoiding digging in roots and fostering imperial attitudes towards the lands that we’re supposed to be guests in – not overlords of.

At the end of the day, no matter how good of relations you have with a country, over time you’re going to wear out a welcome. That in itself is not a good reason to not have military forces stationed overseas at all, but it is a good reason to make sure we only maintain the bases and troops we really need to honor our principles and commitments – especially in peacetime. Despite our widespread military presence currently, most of the military still is stationed in the United States, so it really wouldn’t be that huge of a change. It would just mean thinking harder about what paths and processes we need to rapidly move it to a conflict zone. Really, a lot of this is about thinking harder in general, not only about what we believe as leftists, but also about practical applications of military force and the challenges that involves. We just need to think.

We Can Try (And We Should)

One of the things I grapple with when I try to think of a more ethical and just use of military power is, no matter how I try to dress it, there are always going to be people that I otherwise express solidarity with that are going to be suspicious of it and opposed to it. Some people may take a very long time to come around to the idea and may only do so in part. Some may never come around to it. Frankly, I’ve come to accept that. As much as I want to try and educate and elaborate on why I think this is the realistic and right thing to do, I know that I can’t convince everyone and that ultimately, I can only do so much to try and convince people and the rest is up to them and is their own choice. That, and I can’t blame people – especially those living overseas who have been more directly affected by imperialism than I ever have – for having these attitudes towards the idea of foreign military intervention.

While that is definitely a little discouraging and demoralizing, I try not to let it get me down too much. God knows there so many traps I can fall into – and still fall into – on a daily basis that can lead to depression, discouragement, and borderline “doomerism” and “black pilled” thought with how the state of the world is and the likelihood for change. But I have to believe in something. I have to believe there can be a better world, and I also have to believe I can somehow use what I know from my professional life to contribute to that.

I strongly believe war isn’t going anywhere even if we do (and I hope we do) affect political change. I think we’re going to want to help people beyond our own borders and that will sometimes require providing military aid or carrying out military action. Doing so runs the risks of falling back into old habits unknowingly. While the ideas I’ve laid out here are by no means a panacea for avoiding that sliding back into imperialism, I feel like its maybe a solid starting point. Even if there are going to be people who will still be justifiably suspicious of trying to use military power throughout the world for any sort of positive ends – and that may create stumbling blocks towards doing so, I still think we owe it to try and be a global force for good in that hypothetical future even if it may be difficult and frustrating at times. Why? Because it’s still the right and necessary thing to do. If there’s one thing we know as lefties, it’s that doing the right thing is sometimes a demoralizing pain in the ass – but that doesn’t make it any less right.

#essay#War Takes#War Takes Essay#leftism#leftist#socialism#democratic socialism#international relations#IR#national security#national defense#international security#foreign policy#foreign affairs#military intervention#internationalism#war#empire#imperialism

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

2024/03/19 English

BGM: Jesus Jones - International Bright Young Thing

I worked early today. This morning, I enjoyed the morning English meeting on Zoom as usual. There, a participant taught us that her personal computer had been infected by a computer virus. The other members and I tried to help her by giving various suggestions as advice. I wish her situation would get better… and also, I also felt this is a power of our connection/friendship.

During today's work, I've thought about the novel I am writing - Through this writing, I want to try to keep on asking this to myself. It is simply "Why have I been learning English?". It can be the core of this trial. Why… To become an internationalist? Or just being fluent in English seems really cool? I can't langh at these questions because these ideas are also the ones I have once had in this foolish mind.

Besides that writing, I have been thinking about diversity. One of the reasons why is because April has the "World Autism Awareness Day," therefore I need to think about what autism does mean generally. About this issue, we have to look at the "neurodiversity", which means our brains must have plenty of variety/variation.

Indeed, I am now living my life as having a sense of confidence/self-esteem with this autism. But, how could I have built this esteem? I ask this myself… and find that it must have been built by the various connections I can have had. Once, I had been bullied by a lot of (almost ALL of) classmates. But, now I have so many friends in this "global" world. What connections have enabled me to become this person?

What if I hadn't started learning English like this? Then, I couldn't understand how large this world is… I could even shut this self from any outer actual world, and become a hikikomori - with trying to think that my life is just on my own therefore I must live this life by myself alone.

But, as you can see, it must be wrong. Our life, this lovely life, must have been built by the associations with others I believe. Learning/speaking English actually always reminds me of that principle. Yes, we're not alone.

1 note

·

View note

Note

Got a theory on how socialism went from “working class idpol” to “PMC idpol”, while still claiming to be the former?

There is, as they say, a lot to unpack here.

So first of all, calling socialism ‘working class idpol’ isn’t necessarily wrong but a) phrasing it like that makes me physically cringe and b) it’s really pretty reductionist. The official Marxist doctrine isn’t that the proletariat is especially virtuous or enlightened or deserving, its that it’s exploitation is necessary to the functioning of capitalism, meaning that as capitalism becomes ever more universal workers will have both the means and motive to overthrow it. Though, like, not to say that there isn’t a lot of ‘working class idpol’ in there. If you want to get all Early Christian Heresy about it, I think that got denounced as I want to say Workerism at some point? Something like that.

(Though, like, the period of early Soviet history where people’s class histories was explicitly taken into account in court when determining how harsh a sentence to give them is just very funny in terms of ‘American conservative fever dreams that turn out to have actually happened’. I have a weird sense of humour. Though come to think of it Ascribing Class is actually a pretty useful read in terms of how identity is socially constructed and assigned from on high).

But honestly, well socialism has always been for the working class, the critique that it’s actually by a bunch of genteel delinquents cosplaying as revolutionaries is basically as old as the term. Like, ‘came from a well-to-do family, radicalized when they joined an illicit reading group in school and found Marx’ is basically a cliche of early Bolshevik biographies, and the closest to industrial labour quite a lot of them got was volunteering to teach night schools for the actual proletariat. Like, it was something of an embarrassment for a while the degree that the movement of the working class was actually composed almost entirely of professional revolutionaries and radical intelligentsia – the creation of a socialist labour movement was a deliberate and conscious project which took a decent amount of time to really work, with many (many, many, many) failures along the way. (Too radical and anti-religious and feminist and internationalist for the salt of the earth working types, you understand)

But anyway, all that’s mostly tangential, mostly to say that lawyers and teachers being strident Marxists isn’t even close to new. To at least approach answering your actual question – okay, with apologies to Barbara Ehrenreich, I really feel like ‘Professional-Managerial Class” as a term has gotten so warped by The Discourse that it’s actual use is fairly limited. Like, the Wikipedia article somehow includes ‘teachers’ and ‘nurses’ as central examples (even leaving aside accuracy if you’re a serious socialist on I feel like preemptively disavowing one of the only halfway vital sections of the American labour movement is anathema on a purely tactical level). A lot of the use is just, well, vulgar identity politics – imagining class divides based on culture and affect rather than material circumstances. And to the people the term is actually useful for – wait, have you seriously met many managers or corporate lawyers who call themselves socialists? Like, seriously? I mean, I guess so did Louis Napoleon, but I wouldn’t exactly call him central to the movement.

Alright, sorry, I’m being intentionally obtuse, here. So to answer the question I think you’re asking-

The contemporary boost in the prominence of socialism (in the discourse and in terms of number of publications, if nothing else) has been largely driven by the downwardly mobile children of relatively comfortable parents, both white collar workers and yes, of the professional-managerial class. Due to shifts in economics, culture, and government policy over the last several decades, they overwhelmingly at least attempted to get a college degree. Generally speaking, they were radicalized at least as much by the fact that the system that supported their parents has singularly failed to do so for them as by any particular points of history or theory. Once a significant number in various social circles and cultural scenes were genuinely radicalized, it just became a generally fashionable or acceptable stance to strike, and a useful vocabulary for anyone with even vaguely compatible issues or interests to articulate themselves in.

The natural and inevitable consequence of this is that the modern, western iteration of the socialist movement (such as it is) is generally expressed in the cultural vernacular of people raised as comfortable, liberal children of the American dream, or people directly reacting and responding to that culture. It also means that the focuses and idiosyncratic neuroses of the movement are going to have at least as much to do with the culture as with the ideology – such is human nature, unfortunately.

#reply#anon#political theory#socialism#in this essay I will#this is theoretically a writing blog#long#Anonymous

81 notes

·

View notes

Note

the style council for the band ask! :)

am i a fan? yes !!

first song i heard by them? when i was 12 i was watching an episode of pop quiz where they were playing snippets of the biggest hits of 1983, and one of the songs they played was long hot summer. i really loved how it sounded and that was the first time i had ever heard of the style council or even paul weller :')

favourite song? my ever changing moods, headstart for happiness, here's one that got away, internationalists, speak like a child, long hot summer, a stone's throw away

favourite album? café bleu - it's just one of my favourite albums of all time in general

favourite music video? oh it's absolutely the mv for come to milton keynes. there are so many Questionable Moments but also the 4 unit hsc english student in me is having a field day with analysing the symbolism throughout it. i've been meaning to gif it for ages !!

have any merch? i have café bleu and our favourite shop on vinyl, as well as the 7" of speak like a child. every day i regret not buying home and away at this one record shop bc it was so cheap and every copy i've seen since has cost twice as much :/ apparently my dad also had it on cassette but he doesn't know where it is smh

seen them live? no :(

favourite member? not to be hideously predictable but paul weller <3 although with that being said, dee c lee could absolutely step on me and i would thank her

send me a band!

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

i absolutely love your modern!Heartrender husbands! did they have any growing pains when they got in a relationship/got married cause of their different backgrounds (fedyor being a “posh city boy” and ivan a blue collar factor worker).

Obviously i’d imagine so but i didnt know if we’d see any of this in their appearance in your fantastic helnik story since they’re already so established by then.

Oh, there absolutely were moments of Extreme Struggle. Fedyor's family isn't rich, but they're closer to the well-off end of the spectrum than they are to Ivan's family, and his dad was one of those who actually made out pretty well during Russia's decade of chaotic post-communism privatization. The Kaminskys were at a respectable level of nomenklatura (in other words, members of the family held various government and Party functionary posts during the Soviet Union) and Fedyor had an important uncle or two and ways to get special treats. This means he grew up in relative comfort in Nizhny Novgorod, got admitted to the prestigious Moscow State University, and turned out as a Western-sympathetic internationalist bleeding-heart liberal, who is fluent in English, familiar with the outside world, a fierce critic of the Putin regime, and while he's proud of being Russian, he doesn't consider that to be first and foremost his only identity. In Phantom!Verse, he's 24 in 2010, when he first meets Ivan, which means that he was born in 1986. He barely remembers the USSR, though he probably has a very hazy memory of hearing about the fall of the Berlin Wall and then the end of the whole thing in 1991. This wasn't really a scary thing or an existential threat to him/his family, though, since as noted, his dad did well for himself afterward.

Ivan, on the other hand, is from a dirt-poor working-class family in Krasnoyarsk, Siberia, and his views are very different. He doesn't necessarily agree with how things have gone, politically speaking, but he's still deeply traditionalist, conservative, and nationalist, and he is VERY proud of being Russian and will always see that as his foremost loyalty. In all the cases where he perceives that Russia as a country is being slighted (the Olympics, accusations of Western election interference, etc), he will still more naturally take the Russian side, even if he doesn't always agree with it or personally like Putin. Ivan is 26 in 2010, when he meets Fedyor, so he was born in 1984 and has... a few more memories of the Soviet Union, the fears of the late-term Cold War, the delicate negotiations with Gorbachev and Reagan and the beginning of glasnost and perestroika, and the end of Soviet superpowerdom. Hence the fall of the USSR was terrifying for him, not exciting like it was for Fedyor. His dad and brothers are all of the same "we can't let crazy America get domination over us again, even if Putin is a dick" mindset, and Ivan shares it to some degree.

Of course, Ivan had his own struggles with growing up in a deeply conservative, macho culture/family and realizing that he was gay, which is why he left Krasnoyarsk and moved to Moscow when he was 21 (since he tells Fedyor he's been there for 5 years). He only has a high school diploma and hasn't traveled outside of Russia except to former Soviet countries that also speak Russian, so he's not that familiar with the West except from how it's given to him through the news. He doesn't trust it and doesn't see them as some shining beacon of hope (which you know, Ivan, totally fair). He also thinks that the valiant efforts of Fedyor and his fellow activists are idiotic, doomed, completely pointless, and will only get them into a ton of trouble, but he faithfully turns up at every protest anyway to protect Fedyor, and they have learned how to accept it.

So yes, when they first started living together, it was a bit of a car crash. Fedyor is a night owl who stays up late and then sleeps late in the morning, while Ivan, having worked since he was 16, gets up at 5:00 am every single day (and since they're sharing a bed, his alarm always wakes up Fedyor, which Fedyor doesn't like). Fedyor is messy, while Ivan is obsessively neat and gets stressed out by Fedyor NOT PICKING THE FUCK UP AFTER HIMSELF. They have the aforementioned clash of cultures/personal views to work through, though Ivan is (by the time PEL starts) a lot more liberal than he used to be, at least in some ways. The two of them are married and living (pretty happily) in Brighton Beach, Brooklyn, where Fedyor is still a member of the Russian international resistance in exile and Ivan just likes the fact that everywhere he goes in the neighborhood can speak Russian and it's a decent facsimile of being at home. Which is where they are when they come into PEL in chapter 8. I am on chapter 9 now, so there will probably be another update batch after I finish 10.

As ever, I am excited. For many reasons. So yes.

#ivan x fedyor#heartrender husbands#a phantom in enchanting light#pel asks#i have Many Headcanons about them in phantom!verse#as you can see#anonymous#ask

15 notes

·

View notes

Quote

This is the sound of dancing architecture

“I get to corner Ralf Hütter in a cluttered backwater of EMI house, for a conversational nexus in which we poke theories at each other through the language barrier… Frank Zappa said “writing about music is like dancing about architecture.” This is the sound of dancing architecture…“

An interview with Ralf Hütter by Andrew Darlington, 1981 (the taped conversation is written up later).

Red man. Stop. Eins, Zwei, Drei, Vier. Green man. Go. People respond, regulated by the mechanical switch of coloured lights. Crossing the Pelican towards EMI House it’s easy to submerge in a long droning procession of Kraftwerkian images, pavement thick with lumbering showroom dummies reacting to Pavlovian stimuli, parallel lines of thruways, multi-legged ferroconcrete skyways, gloss-front office-blocks waterfalling from heaven, individuality drowned, starved to extinction, etc, etc. This could get boring. This could be cliché. Ideas prompt unbidden, strategies of sending my cassette recorder on alone to talk to the Kraftwerk answering machine. That’s Kraftwerk, isn’t it? I got news for you. It ain’t.

Ralf Hütter (electronics and voice) is neat, polite, talks quietly with Teutonic inflection, and totally lacks visible cybernetic attachments. He’s dressed in regulation black — as per stereotype — slightly shorter than me which makes him five-foot-eight-inches, or perhaps nine, hair razored sharp over temples not to allow traces of decadent side-burns. Shoes are black, but sufficiently scuffed to betray endearingly human imperfections. He walks up and down reading review stats thoughtfully provided by EMI’s press division. Seems it’s a good review in The Times? Strong on technical details… yes? "No. The writer says we play exactly as on the records, which is not so.” He is evidently chagrined by this particular line of criticism, which is an interesting reaction. I file it for reference. But then again he’s just got up and come direct from his hotel. He wants breakfast. Coffee and cakes. An hour or so to talk to me, then down to Oxford for the dauntingly exacting Kraftwerk sound check rituals. The other Kraftwerkers — Florian Schneider (voice and electronics), Karl Bartos and Wolfgang Flür (both electronic percussion) are otherwise occupied. So every vowel must count. I extend a tentative theory. The image Kraftwerk project of modernity, it seems to me, is largely derived from twenties and thirties originals: the Futurist dedication to movement and kinetic energy; the Bauhaus emphasis on clean, strictly functional lines; the Fritz Lang humans-as-social-ciphers thing. Even an album ‘inspired’ by Soviet Constructivist El Lissitzky with all the machine-art connotations that implies. Doesn’t Hütter find this contradictory? “No. In the twenties there was Futurism in Italy, Germany, France. Then in the thirties it stopped, retrograded into Fascism, bourgeois reactionary tendencies, in Germany especially…” And time froze for forty years. Until the Kraftwerk generation merely picked up the discarded threads, carried on where they’d left off. After the war “Germany went through a period with our parents who were so obsessed with getting a little house, a little car, the Volkswagen or Mercedes in front, or both All these very materialistic orientations turning Germany into an American colony, no new idea were really happening. We were like the first generation born after the war, so when we grew up we saw that all around us, and we turned to other things.” Kissing to life a dormant culture asleep four decades?

But computers only print out data they’re programmed with, so working on this already grossly over-extended mechanistic principle I aim to penetrate Kraftwerk motivations. The dominant influences on them then were — what? American Rock? “No.” In that case, do Kraftwerk fit into the Rock spectrum? “No. Anti - Rock'n'Roll.” So their music is a separate discipline? “Yes, in a way, even though we play in places like Hammersmith. We are more into environmental music.”

So if not Rock, then what? — Berio? Stockhausen? “Yes and no. We listened to that on the radio, it was all around. Especially the older generation of electronic people, the more academic composers — although we are not like that. They seem to be in a category within themselves, and only circulating within their own musical family. They did institutional things — while we are out in the streets. But I think from the sound, yes. From the experimenting with electronics, definitely. The first thing for us was to find a sound of Germany that was of our generation, that was the first records we do. First going into sound, then voices. Then we went further into voices and words, being more and more precise. And for this we were heartily attacked.” He mimics the outrage of his contemporaries — “You can’t do that… Electronics? What are you doing? Kraftwerk? German group — German name? It’s stupid. Music is Anglo-American — it has to be, even when it is in Germany.” The incredulity remains: “Still today, you know. Can you imagine? — German books with English titles, German bands singing English songs. It’s ridiculous!”

Of course it is. But didn’t the Beatles do some German-language records at one time? “Sure” shrugs Hütter, friendly beyond all reasonable expectations. “They were even more open than most of the Germans…” I’d anticipated some mutual incomprehensibility interface with his broken English and my David Hockney Yorkshire. You find the phrasing strange? I’ll tell you… when the possibility of doing this interview first cropped up I ransacked my archives and dug out everything on Kraftwerk I could find. Now it occurs to me that each previous press chat-piece, from Creem to Melody Maker, have transposed Herr Hütter’s every utterance into perfect English. Which is not the case. His eloquence is daunting, but it inevitably has very pronounced Germanic cadences. Sometimes he skates around searching for the correct word, other times he uses the right word in the wrong context. When he says “we worked on the next album and the next album, and just so on”, it really emerges as “ve vork on ze next album und ze next, und just zo on”. It might be interesting to write up the whole interview tape with that phonetic accuracy, but it would be difficult to compose and impossible to read. Nevertheless, I’m not going to bland out his individuality by disinfecting his speech peculiarities, or ethnically cleansing his phrases entirely…

But now he’s in flight and I’m chasing, trying to nail down details. In my head it’s now turn of the decade — sixties bleeding into the seventies, and this thing is called Krautrock. Oh, wow! Hard metallic grating noises, harder, more metallic, more grating and noisier than Velvet Underground, nihilistic Germanic flirtations with the existential void. Amon Düül II laying down blueprints to be electro-galvanised into a second coming by PiL, Siouxsie & The Banshees and other noise terrorists. Cluster. Faust. Then there is the gratuitous language violence of Can, sound that spreads like virus infection from Floh de Cologne and Neu, and Ash Ra Temple who record an album with acid prophet and genetic outlaw Timothy Leary. Was there a feeling of movement among these bands? A kinship?

“No.” One note on the threshold of audibility, shooting down fantasies. “In Germany we have no capital. After the war we don’t have a centre or capital anymore. So instead we have a selection of different regional cultures. We — Kraftwerk — come from industrial Düsseldorf. But Amon Düül II came from Munich, which has a different feeling. Munich is quite relaxed. There’s a lot of landscape around.”

Now for me it’s not just some off-the-top-of-the-head peripheral observation, but the corner-stone of my entire musical philosophy that this affable German is effortlessly swotting, and I’m not letting him off lightly. I restate histories carefully. American Rock'n'Roll happened in 1954 — Memphis, Sun Studios. From there it spread in a series of shock waves, reaching and taking on the regional characteristics of each location it hit. By the mid-sixties a distinctive UK variant had come into being, identifiably evolving out of exposure to US vinyl artefacts, but incontrovertibly also home-grown. Surely Krautrock was evidence that Germany had also acquired its own highly individual Rock voice? It seems to me there is a common feeling, a shared voice among these diverse groups. But he’s not buying. You don’t think so? “No. At least not as far as we were concerned.”

When they started out they recorded in German-language. „We always record in German” he corrects emphatically. „Then we do — like in films, synchronised versions for English. The original records are all German, but we also do French, and now Japanese versions. We are very into the internationalist part.” Continuing this trans-Europe theme he suddenly suggests „Britain is a very historical society. The Establishment. The hierarchy. We come here and we feel that immediately. On the one hand you have this very modern…” he tails off. Starts again, „it’s a schizophrenic country, a modern people, new music and everything, but on the other hand the… how can I say it, a theatrical establishment.” I retaliate, yes — but surely it could equally be argued that all Europe forms a common cultural unit attempting to survive between the historic power-block forces of the USA and the old Soviet Union? Indeed, to journalist Andy Gill, Kraftwerk’s music is „promoting the virtues of cybernetic cleanliness and European culture against the more sensual, body-orientated nature of most Afro-American derived music” (‘Mojo’s August 1987). Europe shares a common heritage uniting Britain, Germany and France, which are all being subtly subverted by a friendly invasion of American Economic and McCultural influences, movies, records, clothes? Witter himself once said „in Germany, Pop music is a cultural import”. „Yes, I know. Certainly when we came to Birmingham (England) we thought it was similar to Düsseldorf. There’s no question. But in Germany it happens even more though, because here in England at least you notice, you know the language and everything. In Germany they don’t notice, it was just taken over.”

I’d always considered the German language to be a defence against foreign influence. It was far easier for mainstream British culture to be accessed, and infiltrated because of a common American-English language. In France, for example, the Government is actively resisting the 'Anglicisation’ of their language through 'Franglaise’, because they rightly see its corruption as the thin end of the wedge. “Maybe. That should be checked. But you, together with the Americans had another situation to start with. After the war, Germany was finished. I’m not saying why or whatever, that’s OK. But when I grew up we used to play around the bomb-fields and the destroyed houses. This was just part of our heritage, part of our software. It was our education and cultural background…” The spectre of Basil Fawlty springs unbidden. Earlier an entirely innocent question about Kraftwerk’s origins had dislodged similar sentiments. He’d spoken of Germany’s Fascist years — “in Germany especially, that’s what I mostly knew about, then all the (artistic / creative) people emigrated, Einstein had to leave, and everybody knows the reasons. And then only after the war — he came back. But I think Germany went through a period, with our parents, who had never had anything. They went through two wars…”

Breakfast becomes manifest. Mushroom quiche — no meat — followed by a choice of apricot or apple flan, plus two coffees. I sit opposite him, tape machine on the floor between us picking up air, the windows of EMI House blanding out over the trees of Manchester Square. I’m marshalling scores. So for, not content with winning each verbal exchange hands down, Ralf Hütter has also squashed each of my most cherished illusions about Krautrock. But on the plus side, massive giga-jolts of respect are due here. Long before the world had heard of Bill Gates or William Gibson, when Silicon Valley was still just a valley and mail had yet to acquire its 'e’ pre-fix, Kraftwerk were literally inventing and assembling their own instruments, expanding the technosphere by rewiring the sonic neural net, and defining the luminous futures of what we now know as global electronica. So perhaps it’s time to probe more orthodox histories?

It seems to me there are two distinct phases to Kraftwerk’s career. Or perhaps even three. The first five years devoted purely to experimental forays into synchromeshed avant-electronics, producing the batch of albums issued in Britain through Vertigo — Kraftwerk in 1972, Ralf Und Florian the following year, the seminal Autobahn in 1974, and the compilation Exceller 8 in 1975. Then they switch to EMI, settle on a more durable line-up and the subsequent move into more image-conscious material, a zone between song and tactile atmospherics. The third, and current phase, involves a long and lengthening silence.

"No, it wasn’t like that” says Hütter. “It was…” his hand indicates a level plane. 'There was never a break. It was a continual evolution. We had our studios since 1970, so we always worked on the next album, and the next album, and so on. I think Düsseldorf therefore was very good because we brought in other people, painters, poets, so that we associated ourselves with…“ his sometimes faulty English — interfacing with my even more faulty German — breaks down. The words don’t come. So he switches direction. “Also we had some classical training before that [Ralf and Florian met at the Düsseldorf Conservatory], so we were very disciplined.” Others in this original extended family of neo-Expressionist electro-subversives included Conny Plank (who was later to produce stuff for Annie Lennox’ The Tourists, and Ultravox), Thomas Homann and Klaus Dinger (later of Neu), artist Karl Klefisch (responsible for the highly effective Man Machine sleeve), and Emil Schult (who co-composed Trans-Europe Express). In the subsequent personnel file, as well as Hütter, there is Florian Schneider who also operates electronics and sometimes robotic vocals. While across the years of their classic recordings they are set against Karl Bortos and Wolfgang Flür who both manipulate electronic percussion.

I ask if they always operate as equal partners. “Everybody has their special function within the group, one which he is good at and likes to do the most.” It was never just Ralf und Florian plus a beatbox rhythm section? “No. It’s just that we started historically all that time ago and worked for four years with about twenty percussionists, and they would never go into electronics, so we had to step over, banging away and things like that. And then Wolfgang came in.”

With that sorted out I ask if he enjoyed touring. „Yes, basically, because we don’t do it so often. But we also enjoy working in our studios in Düsseldorf, we shouldn’t tour too much otherwise… we get lost somewhere, maybe! We get too immunised. When you have too much you must shut down because you get too many sounds and visions from that tour. For the first five years we toured always in Germany on the Autobahns — that’s where that album came from. Since 1975 we do other countries as well.” They first toured the USA in March 1975, topping the bill over British Prog-Rockers Greenslade, then — leaving an American Top Thirty hit, they went on to play eight British dates in June set up for them by manager Ira Blacker.

How much of that early music was improvised? Was the earlier material 'freer’? Kraftwerk numbered Karl Klaus Roeder on violin and guitar back then, so are the newer compositions more structured? „No. We are going more… now that we play longer, work longer than ten years, we know more and every afternoon when we are in the Concert Hall or somewhere in the studio we just start the machines playing and listen to this and that. Just yesterday we composed new things. Once in Edinburgh we composed a new piece which we even included in that evening’s show. New versions on old ideas. So we are always working because otherwise we should get bored just repeating. And it’s not correct what he (the hostile gig reviewer) was saying — that we play on stage exactly like we sound on the record. That’s complete rubbish. It means people don’t even notice and they don’t listen. They go instead over to the Bar for a drink! We, our music is very basic, the compositions are never complex or never complicated. More sounds — KLINK! KLUNK!! Metallic sound. We go for this sound composition more than music composition. Only now they are thematically more precise than they were before.”

After so long within the genre don’t they find electronics restricting? „No, just the opposite.” Words precise with the sharp edge of Teutonic resonance. „We can play anything. The only restrictions we do find are, like in writing, as soon as you have a paper and pen — or a computer or a cassette recorder and a microphone, and you bring ideas, you find the limitation is in what you program rather than what is in the microphone or the cassette. You — as a writer, writing this interview, can’t say that the piece you are writing is not good because the word processor did not pick out the right words for you. It’s the same with us. If we make a bad record it’s because we are not in a good state of mind.”

Change of tack. There’s a lot of Kraftwerkian influence around. Much of current electro-Dance seems to be plugged directly into the vaguely 'industrial’ neuro-system that Hütter initially delineated, while dedicated eighties survivalist cults Depeche Mode and Human League also have Kraftwerk DNA in their gene-code. He nods sagely. “There’s a very good feeling in England now. It was all getting so… historical.” Is the same thing happening in Germany now? Is there a good Rock scene there? “No. But New Music (Neu Musik).”

Hütter’s opinions on machine technology have been known to inspire hacks of lesser literary integrity to sprees of wild Thesaurus-ransacking adjectival overkill, their vocabularies straining for greater bleakness, more clone-content, 'Bladerunner’ imagery grown bloated and boring through inept repetition. And sure, Kr-art-werk is all geometrical composition, diagonal emphasis, precision honed etc, but their imagery is not entirely without precedent. Deliberately so. Their 'Man-Machine’ album track “Metropolis” obviously references German Fritz Lang’s 1926 proto-SF Expressionist movie. The sleeve also acknowledges the 'inspiration’ of Bauhaus constructivist El Lissitzky. I went on to hazard the connections with German modern classical music bizorro Karlheinz Stockhausen — particularly on Kraftwerk’s Radio-Activity album, where they use the 'musique concrete’ technique of surgical-splicing different sounds together from random areas. Radioland uses drop-in short-wave blips, bursts and static twitterings, Transistor has sharp pre-sample edits, alongside the pure found-sound audio-collage The News. A technique that resurfaces as late as Electric Cafe, where The Telephone Song is made up of 'phone bleeps and telecommunication bloopery. He’s familiar with the input. Immediately snaps back the exact location of the ideas — Kurzwellen, from Stockhausen’s back-catalogue. And what about the aural applications of Brion Gysin/William Burroughs’ literary cut-up experiments? Is there any interaction there? “Maybe” he concedes. “'Soft Machine’, contact with machines. But we are more Germanic.” He pauses, then suggests “we take from everywhere. That’s how we find most of our music. Out of what we find in the street. The Pocket Calculator in the Department Stores.”

The music is the message — 'the perfect Pop song for the tribes of the global village’ as Hütter once described it. The medium and the form? “If the music can’t speak for itself then why make music? Then we can be writers directly. If I could speak really everything I want with words then I should be working in literature, in words. But I can’t, I never can say anything really, I can’t even hardly talk to the audience. I don’t know what to say. But when we make music, everything keeps going, it’s just the field we are working in, or if we make videos we are more productive there.”

I quote back from an interview he did with Q magazine in July 1991 where he suggests that traditional musical skills are becoming increasingly redundant. “With our computers, this is already taken care of,” he explains. “So we can now spend more time structuring the music. I can play faster than Rubenstein with the computer, so it [instrumental virtuosity] is no longer relevant. It’s getting closer to what music is all about: thinking and hearing.”

So technology should be interpreted as a potentially liberating force? “Not necessarily. I don’t always find that. Dehumanising things have to be acknowledged. Maybe if you want to become human, first you have to be a showroom dummy, then a robot, and maybe one day…” An expressive wave. “People tend to overestimate themselves. I would never say I am very human. I still have doubts. I can project myself as a semi-god. I can do that. The tools exist for me to achieve that. But I’d rather be more modest about this, about our real function in this society, in these blocks here,” indicating out through the plate glass, across the square, to the city towers of finance and global commerce beyond. “People overestimate themselves. They think they are important. They think they are human.”

I’m out of synchronisation again. Surely, if people have to extricate themselves from the machinery they have created, to become human, then it’s due to the imperfections of the technology — not the people. Machines are intended to serve, if they do otherwise, they malfunction. “Not so. They should not be the new slaves. We are going more for friendship and co-operation with machines. Because then, if we treat them nice, then they treat us nice. You know, there are so many people who go in for machines, who when you come to their homes their telephones are falling to pieces, their music centres don’t function, the television set is ruined. But if you take care of your machines then they will live longer. They have a life of their own. They have their own life-span. They have a certain hour of duration. There are certain micro-electronics which work a thousand hours. Then there is a cassette recorder battery which operates ten or twelve hours.” The mentality you oppose, then, is that of conspicuous consumption, planned obsolescence, the psychology of 'a spoilt child’?

“The energy crisis, the whole thing is a result of thinking that everything is there, we just have to use it, take this, and — PTOOOOFFF! — throw it away. But make sure that the neighbours see! This whole attitude of disassociating oneself from machines — humans here and machines over there. When you work so much with machines — as we do — then you know that has to change.”

Earlier he’d spoken of growing up 'playing around the bomb-fields and destroyed houses’ in the wake of WWII, so this respect for material possessions is perhaps understandable. But he sees beyond this. He sees machines having the potential to free people physically from unnecessary labour, and culturally to create whole new thinking.

“I mean — where is my music without the synthesiser? Where is it?” The music, the intelligence, is in your head. Without that the synth is just….“

"Yes, bringing it about! The catalyst. We are partners. We two can together make good music, if we are attuned to each other.” But you could operate another instrument. The vehicle you use is incidental. You could walk out this building, buy a new synth here in London, and play it just as well as your own equipment in Düsseldorf. “Yes. That is because I have this relationship with this type of thing.”

I’m reproducing this exactly as it happens, and still I’m not exactly sure what he’s getting at. Perhaps something is lost in the language gap. Like earlier, he’d said “I would never say I am very human” and I’d accepted it first as role playing — until he’d made it obvious that he equates 'becoming human’ with 'achieving freedom’. Humanity is something that has to be earned. You can’t be robot and human. But this is not a natural conversation. This is on interview. A marketing exercise designed to sell Kraftwerk records by projecting certain consumer-friendly imagery. He is playing games, and this cyber-spiel is what journalists expect from Kraftwerk? But to Ralf Hütter there seems to be more to it than that. He believes what he is saying. At least on one level. Some impenetrable levels of ambiguity are at work concerning this alleged relationship to technology.

Baffled, I skate around it. What crafty work is afoot for the future? “For me? For Kraftwerk? Well, certain things that I had to remember and memorise and think about are now programmed and stored. So there’s no restriction that we have to rehearse manually. There’s no physical restriction. I can liberate myself and go into other areas. I function more now as software. I’m not so much into hardware. I’m being much more soft now since I have transferred certain thoughts into hardware. That is why we put those two words together Software/Hardware on the album. Because it is like a combination of the two — Man/ Machine — otherwise it would not be happening. We can play anything. Our type of set-up — and group, the studio, the computers and everything. Anything.”

So what’s new in electronics, Ralf? “What we find now is like, a revolution in machines. They are bringing back all the garbage now that has been put into them for the last hundred years and we are facing a second, third and fourth Industrial Revolution. Computers. Nano-electronics. Maybe then we come back into Science Fiction? I don’t know.” Then, on inspiration, “there’s another thing coming out. 'Wet-Ware’, and we function also — in a way, as Wet-Ware.”

I’m hit by a sudden techno-blur of off-the-wall ideas, imperfectly understood concepts of some electro-erotic wet ’T’-shirt ritual in the pale blue wash of sterile monitors. What is 'Wet-Ware’, Ralf? Spoken with bated breath. And he explains. Like hardware is machines. Software is the data that is fed into them. “Wet-Ware is anything biochemical. The biological element in the machine!” The programmer? I see. Fade into intimations of cybernetic übermensch conspiracies.

So with these limitless vistas of techno-tomorrows, Kraftwerk will continue for some time yet? "Yoh. Yes.” Pause, then the laugh opens up, “… until we fall off the stage!”

Auf Wiedersehen, Ralf…

Eins, Zwei, Drei, Vier…

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

for @shitpostingfromthebarricade , who very nicely asked for an elaboration of my partial disagreement with the idea that Grantaire represents “the people” of France or Paris:

First let me say again it’s a partial disagreement; I do think he represents a specific segment of the people. But one which is not ~~**~~ The People~~**~~ which I will hopefully be able to explain here?

- As far as “the people” goes, that term-- that specific term, “the people” detached from other qualifiers-- especially in Hugo’s specific political-social group-- seems to have been used mostly to mean the workers-- workers, small artisan-merchants, maybe peasants. If someone in a socialist-writer text of the period is called a “child of the people” it means they’re from the working class; if they’re a Man Of The People , ditto. Feuilly is the representative of The People in the Amis’ group-- Enjolras even specifically says so, in the middle of one of his full-on visionary speeches--Feuilly,vaillant ouvrier, homme de peuple, hommes des peuples” (valiant working-man,man of the people--and then the transition/combo that can be read as “man of all peoples” or “men of the people” , plural (or, actually, as “the people’s man”, depending on what you’re choosing to focus on. Lamarque song rewrite go!) . For a guy with very few lines, Feuilly is specifically carrying a LOT of social/political representation here :P (and of course it’s even more Symbolic because Feuilly has no known human parents; his class background is also his family background, he’s of The People, full stop, not of any more specific background. )

We’re never given Grantaire’s exact socioeconomic background, and certainly working-class kids could go into art studies in certain circumstances-- but Grantaire also has no apparent job and has a lot of middle-class-kid hobbies (boxing, singlestick, dancing, etc etc). Everything about Grantaire marks him as middle-class in background, currently choosing to vie-boheme it up. He’s definitely not a representative of “the people” in this sense.

I also can’t go with Grantaire representing Paris, at least not Full On Spirit Of Paris. Leaving aside that Grantaire specifically disavows Paris and his own Parisian-ness in Preliminary Gayeties, Hugo sets up very specific symbolism and character for Paris in Les Mis, and he’s pretty direct about it!

Hugo’s Paris is wild, bold, anarchic, laughing, unafraid of violence, sometimes lazy or careless but essentially generous, bold, insightful and daring, and always inherently inclined to liberty (and also essentially Romantic at its heart, because this is a Hugo novel and anything good has to be essentially Romantic at heart:P) (and Hugo has a Lot of Feelings about Paris). Paris in miniature--Paris Atomized, Paris made human-- is Gavroche, not Grantaire. Even among just the Amis, the one closest to being Hugo’s Paris Avatar is Bahorel, who shares so many echoes of the gamin chapters in his intro, the group’s flâneur-- flâner est Parisien!--and connection to the city, in the same way Feuilly is their connection to the wider world and internationalist causes.

But like I said, I do really think Grantaire represents a part of the population of Paris! An important part!

Specifically, he’s representing that part of the population that wants to take a damn break. The part that feels that “of great events, great hazards, great adventures, great men, thank God, we have seen enough, we have them heaped higher than our heads”,(4.1.1) the part that having found a seat wants to sit. The perhaps selfish, but very understandable, part of the population that is secure enough itself to feel like it will do nothing but lose in another revolution, that “some one whose name is all” that says “I am young and in love, I am old and I wish to repose, I am the father of a family, I toil, I prosper, I am successful in business, I have houses to lease, I have money in the government funds, I am happy, I have a wife and children, I have all this, I desire to live, leave me in peace.” (5.1.20)

That is to say...Grantaire is representing the apathetic, the burned out, and the bourgeoisie.

This is certainly not the most flattering thing to be representing, but then Grantaire isn’t a particularly aspirational character--not until the very end of his arc, when he stands up and announces himself For The Ideal. Like the people who close their doors,like the bourgeoisie who just wants to rest, he doesn’t hate the ideal, really...but he’s had Enough Trying, he wants peace and security and to not die or see his loved ones die, and all of that is very understandable! But if he were genuinely happy with that...well he wouldn’t be with the Amis at all. He also wants that Ideal, a better kinder world, and unfortunately to get that he’s going to have to stand up.

..Well, not him, personally,of course. When he stands up he’s-a-gonna die, albeit in a super symbolic transformational/salvational way. But the Not Very Subtle At All implication is that this is where the revolution wins: when the comfortable people , and especially the bourgeoisie (well, as Hugo defines them), who have been sitting down, sleeping, wake up and take part.

(This is of course true in a grand sense-- revolutions need mass participation! -- and it’s also true in the very specific sense of what went down in 1830 vs 1832. In 1830, a lot of the bourgeoisie did get involved , and it’s a big part of why that went as smoothly as it did. But in 1832, by and large they said No Thanks We’re Good; a handful of students and some wild Romantics really was about all participation outside of the working/poor classes. But this is already so freaking long and this is not a Barricade Day post!)

So: all of that very long ramble is to say, yeah, I think Grantaire is symbolizing not The People (who are , symbolically and historically, already on the barricade) but a specific and crucial subset of The People Of France (Or Wherever), which is why I never feel like I can go either “Yeah!!” or “Ugh No” when I see a “Grantaire is the people” mention. :P

--sorry I can’t put them under a second cut >< , but these are relevant longer chunks of some of the quotes above!

Of great events, great hazards, great adventures, great men, thank God, we have seen enough, we have them heaped higher than our heads. We would exchange Cæsar for Prusias, and Napoleon for the King of Yvetot. “What a good little king was he!” We have marched since daybreak, we have reached the evening of a long and toilsome day; we have made our first change with Mirabeau, the second with Robespierre, the third with Bonaparte; we are worn out. Each one demands a bed.Devotion which is weary, heroism which has grown old, ambitions which are sated, fortunes which are made, seek, demand, implore, solicit, what? A shelter.”(4.1.1, Well Cut)

The bourgeois is the man who now has time to sit down. A chair is not a caste.

But through a desire to sit down too soon, one may arrest the very march of the human race. This has often been the fault of the bourgeoisie. (4.1.2, Badly Sewed)

And it appears that they are going to fight, all those imbeciles, and to break each other’s profiles and to massacre each other in the heart of summer, in the month of June, when they might go off with a creature on their arm, to breathe the immense heaps of new-mown hay in the meadows! Really, people do commit altogether too many follies. An old broken lantern which I have just seen at a bric-à-brac merchant’s suggests a reflection to my mind; it is time to enlighten the human race. Yes, behold me sad again. That’s what comes of swallowing an oyster and a revolution the wrong way! I am growing melancholy once more. Oh! frightful old world. People strive, turn each other out, prostitute themselves, kill each other, and get used to it!

... I don’t think much of your revolution,I don’t execrate this Government. It is the crown tempered by the cotton night-cap. It is a sceptre ending in an umbrella. In fact, I think that to-day, with the present weather, Louis Philippe might utilize his royalty in two directions, he might extend the tip of the sceptre end against the people, and open the umbrella end against heaven. ” - (Grantaire, from Premliminary Gayeties, 4.12.2)

What, then, is progress? We have just enunciated it; the permanent life of the peoples.

Now, it sometimes happens, that the momentary life of individuals offers resistance to the eternal life of the human race.

Let us admit without bitterness, that the individual has his distinct interests, and can, without forfeiture, stipulate for his interest, and defend it; the present has its pardonable dose of egotism; momentary life has its rights, and is not bound to sacrifice itself constantly to the future. The generation which is passing in its turn over the earth, is not forced to abridge it for the sake of the generations, its equal, after all, who will have their turn later on.—“I exist,” murmurs that some one whose name is All. “I am young and in love, I am old and I wish to repose, I am the father of a family, I toil, I prosper, I am successful in business, I have houses to lease, I have money in the government funds, I am happy, I have a wife and children, I have all this, I desire to live, leave me in peace.”—Hence, at certain hours, a profound cold broods over the magnanimous vanguard of the human race. (5.1.20, The Dead Are In The Right and the Living Are Not Wrong)

118 notes

·

View notes

Link

This article is a must read, and so I have posted it here. Douglas Rushkoff is a fantastic human, please follow him on twitter here. Check out his books and Ted talks, he also has interviews on Youtube.

Anyway this article is just...incredibly revealing. America is really just one big PsyOp. His comments on civilization are A+++:

“Until quite recently, films like 1954’s Abstract in Concrete were banned for American viewers. Although produced with U.S. tax dollars, this cinematic interpretation of the lights of Times Square was meant for European consumption only. Like the rest of the art and culture exported by the United States Information Agency, Abstract in Concrete was part of a propaganda effort to make our country look more free, open, and tolerant than many of us preceived or even wanted it to be. In the mid-1940’s, when conservative members Congress got wind of the progressive image of America we were projecting abroad, they almost cut the USIA’s funding, potentially reducing America’s global influence.

Well, America today is in no danger of projecting too free, open, or tolerant a picture of itself to the world. But I’m starting to wonder if maybe the nationalist, xenophobic, inward-turned America on display to the world these days might just be the real us — the real U.S. Maybe the propaganda we created to make ourselves look like the leading proponents of global collaboration and harmony was just that: propaganda.

~Once the USSR and the U.S. divided Europe into East and West and the Cold War began, America went on a propaganda effort to present itself as more enlightened and free than the communists.~

Since the great World Wars, America has had a vested interest in fostering a certain global order. President Woodrow Wilson, who had run for president on a peace platform, ended up bringing America into World War I. When it was done, he established something called The League of Nations, which was meant to keep the peace. Thanks to an isolationist Congress, however, the United States never actually joined the League of Nations. That should have been a big hint that America’s interest in global cooperation was fleeting, at best.

During World War II, Roosevelt took his shot at global harmony with his “Declaration by United Nations,” which eventually gave birth to the UN, dedicated to international peace and basic human rights around the world. To most Americans, however, the United Nations represented little more than a way of preventing the sort of war that would again require American intervention. Yes, it was in New York, and yes, it was conceived and spearheaded by Americans but this didn’t mean that America really thought of itself as part of a great international community. The UN was really just a way for us to avoid having to go “over there” again.

This was surprising to me. I grew up in the 1970s, at the height of America’s cultural outreach to Europe and the world. I remember how great Russian artists and ballet dancers would come to New York, and how American artists and writers would go to Europe. There were exchange students in my high school from Italy, France, and Germany. The outside world — the international society of musicians, writers, thinkers that America was fostering— seemed more artistic, cultural, and tolerant than what I knew here, at home. It seemed like the future.

~~~

This was by design, and part of a propaganda effort that began in the 1940's. Once the USSR and the U.S. divided Europe into East and West and the Cold War began, America went on a propaganda effort to present itself as more enlightened and free than the communists. The State Department, the CIA, and the United States Information Agency, as well as an assortment of foundations from Rockefeller’s to Fulbright’s, all dedicated themselves to painting a positive picture of America abroad. This was big money; by the late 1950’s the USIA alone spent over $2 billion of public money a year on newsreels, radio broadcasts, journalism, and international appearances and exhibitions. This included everything from Paris Review articles to Dizzy Gillespie concerts.

The problem was that the image of America that these agencies projected to the world wasn’t the image many Americans had of their country. Information agencies were busy trying to make us look like an open and free society, as sophisticated and cosmopolitan as any European one. So, abstract art exhibits and films, book collections with modernist novels, intellectuals, people of color, modern dancers, and all sorts of avant-garde culture was sent for consumption abroad.

Conservative Americans, as well as the senators who represented them, saw this stuff as gay, communist, Jewish, urban, effete, and an altogether terrible misrepresentation of who we were and what we stood for. Why, they asked, should we be spending upwards of two billion dollars exporting decadent, self-indulgent art and culture to the world?

~~~

So Congress — convinced that there was still a national security advantage, or at least a business justification, in maintaining American global outreach — passed a compromise called the Smith-Mundt Act in 1948. The law made it illegal for the USIA to release any of its propaganda within the United States. Ostensibly, this was to protect Americans from the potentially manipulative propaganda it was spreading abroad. Information is a form of PSYOPS (psychological operations), after all, and we are not going to use such weapons on our own people.

But the real reason for the Smith-Mundt act was to prevent Americans from seeing themselves represented in ways that they didn’t agree with. The books in the traveling library were titles that many Americans thought would be better burned than celebrated. And the overall ethos of the program — to promote America’s internationalism and free society — were in direct contradiction to the values that many Americans held. The Smith-Mundt act created a wall between the image of America we exported to the world, and the one we maintained about ourselves.

By the time the Internet emerged, this division became impossible to keep up. YouTube, the Internet Archive, and Facebook bring everything to everyone. So in 2012, Smith-Mundt was repealed. Concerned netizens saw a conspiracy. Did this mean the government would now be free to use its psychological warfare on U.S. citizens? Perhaps. But the real intent was to relieve the government’s communications agencies from trying to hide their messaging from Americans in an age when hiding such programming is impossible.

~~~