#State Museum of Egyptian Art

Text

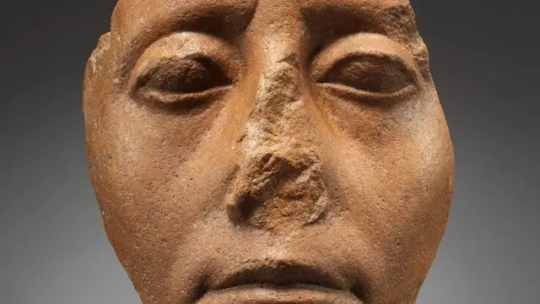

Head of the ancient Egyptian king Khufu (Cheops), originally from a limestone statue. Artist unknown; ca. 2400 BCE (4th Dynasty, Old Kingdom). Now in the State Museum of Egyptian Art, Munich, Germany. Photo credit: Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP/Wikimedia Commons.

#art#art history#ancient art#Egypt#Ancient Egypt#Egyptian art#Ancient Egyptian art#4th Dynasty#Fourth Dynasty#Old Kingdom#Khufu#Cheops#sculpture#portrait sculpture#limestone#stonework#carving#State Museum of Egyptian Art

103 notes

·

View notes

Note

when i visited Egyptian antiquities it was shocking how lax the security was. Many visitors at every site i visited scratched the wall reliefs and paintings or climbed the bases of sculptures. It seems like at this rate there will be nothing left in 100 years it’s such a shame. An egyptologist also told me that the new Egyptian museum wasn’t properly acclimatised and test-run empty for a year like is customary to ensure the artefacts are safely kept. You’re right that Egyptian institutions and the government control their heritage but i feel like they could preserve it a little better. And it’s not like antiquities are such a small priority to the state, because they derive a lot of nationalist symbolism + cultural and economic capital from it, so it doesn’t make sense to me even in a utilitarian way.

(I don’t mean this in a xenophobic way btw i love Egypt and Egyptian culture, things are just badly run. And i’m not just saying that as a tourist, Egyptians always talk about how fucked the government is in other ways.)

I don’t have a solution i just wish the researchers and museums and sites good luck in carefully preserving this heritage.

This really is just repackaged 'the Egyptians can't take care of their own heritage and history' nonsense. It is xenophobic whether you intended it or not.

Many sites around the world have people clamber over them every day. The sites in Egypt have stood for over 4000 years, and yet you imagine they'd be gone in less than 100? Are you kidding me?

Museums don't need to be left to acclimatise for a whole year. That's nonsense. You can acclimatise the cases for about a week, but you don't need to leave the whole building empty. Most artefacts would be in cases, and those would be already acclimatised before objects were brought in and then continually monitored. Anything outside that would be stone and thus not affected by climate control within the museum. The Grand Egyptian museum isn't even open yet. They're still working on it. But some artefacts have been moved over and are being cared for and conserved in brand new state of the art facilities.

No, the government in Egypt isn't the best. No, they don't have all the state of the art facilities that other countries might have. But they're not actively damaging their heritage. Artefacts are well looked after.

Finally, if you claim you saw that many people actively damaging sites by scratching into the walls and you sat by and did nothing, then that makes you as bad as them.

269 notes

·

View notes

Text

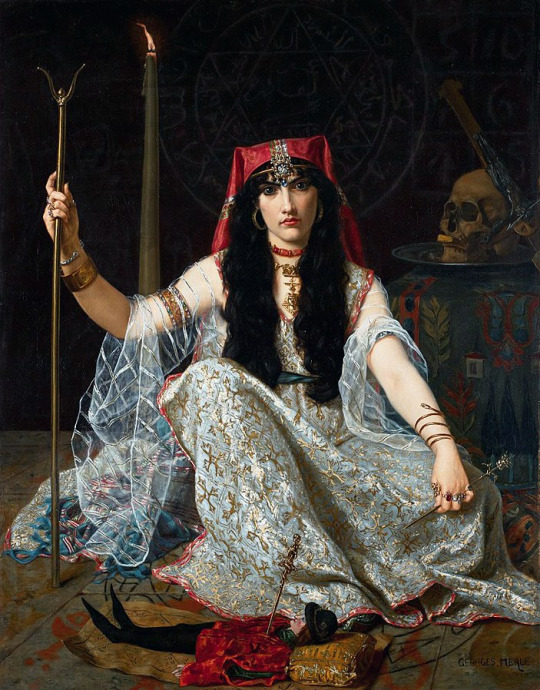

Georges Merle (1851-1886)

"Une sorcière au xve siècle" ("A Fifteenth-century Sorceress") (1883)

Oil on canvas

Located in the Birmingham Museum of Art, Birmingham, Alabama, United States

The commanding figure depicted in the middle of performing a spell is likely a subject from literature, although the source has yet to be identified. The mysterious symbolism, including a voodoo doll, pentacle, Egyptian imagery, and more, can be clarified when the origin of the story is known. Until then, the secrets of "The Sorceress" remain fascinating and perplexing.

#paintings#art#artwork#literary painting#halloween#georges merle#oil on canvas#fine art#museum#art gallery#october#female portrait#portrait of a woman#black hair#blue dress#dresses#skull#skulls#magic#costume#costumes#clothing#clothes#1880s#late 1800s#late 19th century#aesthetic#aesthetics#red

501 notes

·

View notes

Text

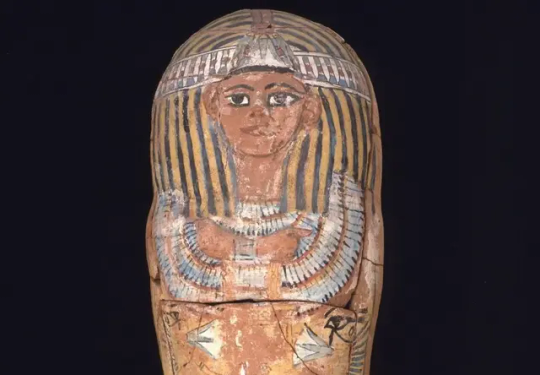

MFA Boston Returns Stolen Egyptian Child Sarcophagus to Sweden

The coffin was taken from the collection of a museum in Uppsala.

A coffin that was used to bury an Egyptian child named Paneferneb between about 1295 and 1186 B.C.E., which has been in the hands of the Museum of Fine Arts Boston since 1985, has been returned to a museum in Sweden after MFA staff discovered that the piece was stolen from the Gustavianum, Uppsala University Museum, around 1970.

The British School of Archaeology in Egypt unearthed the coffin in 1920 at Gurob, Egypt. Overseeing the dig was Flinders Petrie, who, with his wife, Hilda Urlin, excavated numerous important archaeological sites. Among his most significant finds was the Merneptah Stele in 1896; he also discovered the Proto-Sinaitic script, the ancestor of almost all alphabetic scripts, in 1905.

At the time, the Egyptian government had put in place a system of “partage,” or a division of finds, whereby it distributed the results of archaeological excavations between Egypt and the foreign parties sponsoring the digs. As part of that system, the coffin went in 1922 to Uppsala University’s Victoria Museum of Egyptian Antiquities, as it was then called. But the sarcophagus, made of pottery and measuring about 43 inches in length, went missing by at least 1970.

The coffin resurfaced in 1985, when the MFA bought it from one Olof S. Liden, who claimed to represent the artist Eric Ståhl. He presented a forged letter in which Ståhl supposedly recounted having excavated the coffin at Amada, Egypt, in 1937. Liden also presented falsified documents authenticating the coffin, purportedly from experts in Sweden. Ståhl, noted the museum in its announcement of the return of the coffin, “is not known to have participated in any excavation in Egypt.”

Curators at the MFA first smelled a rat upon finding a photograph of the coffin in the process of excavation in the 2008 book Unseen Images: Archive Photographs in the Petrie Museum, which noted that it went to Uppsala. When they noted the discrepancy, they contacted the staff at the Gustavianum, and the process of returning the piece began; the museum’s website stated that it was deaccessioned in October.

“It has been wonderful working with our colleagues in Uppsala on this matter, and it is always gratifying to see a work of art return to its rightful owner,” said Victoria Reed, senior curator of provenance at the MFA. “In this case, we were fortunate to have an excavation photograph showing where and when the coffin was found, so that we could begin to correct the record. Anytime we deaccession and restitute a work of art from the museum, it serves as a good reminder that we need to exercise as much diligence as possible as we build the collection.”

The MFA Boston’s department of the art of ancient Egypt, Nubia, and the Near East includes some 65,000 artifacts, including sculpture, jewelry, coffins, mummies, mosaics, and more, placing it among the world’s largest collections of such items, along with institutions like the Grand Egyptian Museum in Giza and London’s British Museum. The Gustavianum houses a collection of about 5,000 examples.

By Brian Boucher.

#MFA Boston Returns Stolen Egyptian Child Sarcophagus to Sweden#Egyptian child named Paneferneb#sarcophagus#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#ancient egypt#egyptian history#egyptian hieroglyphs#egyptian art#egyptian antiquities#looted art#stolen art

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

So-called "Ivory of Shapash" (North-Semitic Sun Goddess)

Origin: Syro-Phoenician, ca. 8th century BCE

Found in palace of Ashurnasirpal II

Nimrud, Iraq (Assyria)

(Met Museum 59.107.7, Pub Domain, Enhanced)

Built by the Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II, the palaces and storerooms of Nimrud housed thousands of pieces of carved ivory. Most of the ivories served as furniture inlays or small precious objects such as boxes. While some of them were carved in the same style as the large Assyrian reliefs lining the walls of the Northwest Palace, the majority of the ivories display images and styles related to the arts of North Syria and the Phoenician city-states. Phoenician style ivories are distinguished by their use of imagery related to Egyptian art, such as sphinxes and figures wearing pharaonic crowns, and the use of elaborate carving techniques such as openwork and colored glass inlay. North Syrian style ivories tend to depict stockier figures in more dynamic compositions, carved as solid plaques with fewer added decorative elements. However, some pieces do not fit easily into any of these three styles.

Source: The Met Museum

#shapash#shamash#goddess#sun goddess#winged sun#lion#costume#phoenician costume#syrian costume#egypt#egyptian gods#canaan#canaanite gods#phoenicia#phoenician gods#aram#aramean gods#syria#syrian gods#levantine gods#mesopotamia#mesopotamian gods#pagan gods#polytheism#archeology#magic#witchcraft#witchblr#paganblr#occult

107 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sigh.

Heavy sigh.

I haven’t stated my thoughts on the movie trailer yet. Instead I have been watching different reaction trailers and reading articles and blurbs on it. Luckily I have not ventured into the dumpster fire that is Twitter and its reactions.

But it is frustrating. This article frustrates me. I have been studying Napoleon for (ahem 30+ years) and to say that Napoleon is too often portrayed is laughable. Why does that not feel so to the Napoleonic Community? Bill and Ted’s , Night At The Museum, doesn’t count in my book because Napoleon is basically charactured.

I am not here to argue Napoleon was a saint, he was not. I am not even interested in that debate anymore as it’s been done to death. But I am also alarmed, as a history geek and as a historian, of this movement that we should only study those who are deemed “good” by society’s whims at the given moment. From some of the reactions (or over reactions) that seems to be somewhat what I hear. Or jealousy that your favorite historical whoever has not yet had a film dedicated to them. I know, it sucks and is frustrating. Napoleon scholars can sympathize.

What is also slightly amusing to jarring is the armchair commentators who know “something” but often by their commentary show they know nothing. The video yesterday I posted of the two historians commenting, albeit in pro British ways, were talking about how they knew nothing of the Survivor’s Balls that happened after the Terror. That women would cut their hair short and wear a red ribbon around their neck. This all goes to prove I guess that even the big not so accurate Hollywood movies can have their teachable moments. The Napoleonic period of course is so wide that historians focus on different areas to study and concentrate on too. Josephine isn’t an unknown character, like these commentators seemed to be suggesting, they just haven’t picked up a biography on her or turned their eye to that part of Napoleonic history.

I will close with this last example. I was watching a reaction video to the trailer where when the Egyptian scene came on the person shook their head in disgust. Afterwards they said with all the authority that their know-how afforded them: “So let me say, Napoleon was a racist. Okay? I know that. That is why he shot at the pyramids. That is why he shot the nose off the Sphinx. It had an African face with African features and he destroyed it because he hated it. “

Sigh. Okay. I get that you want to be outraged at Napoleon for political points, but at least be outraged at things he actually did, and there are a few, than made up things you have read from questionable sources. Point one, Napoleon did not shoot at the Pyramids. He did make his way to them eventually but the Battle of the Pyramids happened miles away from the location where they stand. About three hour walk or so. The Pyramids were not shot at for target practice or because Napoleon and the French Army found them repulsive. Second, Napoleon had nothing, absolutely nothing, to do with Sphinx’s nose. Theory holds that ancient statues, ancient even in Napoleon’s time, weaken and one of the first places they start to crumble is in the nasal area. Napoleon did not shoot the nose off personally because he was a racist mofo who saw the Sphinx and it made him mad because it had Egyptian features.

These are teachable moments but it would be nice before you get riled up or get your viewers riled up, you at least had accurate history. Here is what Napoleon did do in Egypt…he brought along scholars and artists and they discovered new species (to them) and new art (to them) and discovered and little old thing called the Rosetta Stone that helped crack hyroglyphics. Did they loot? You bet. Did they take off with things? Sure did. That you can debate on, but not shooting the nose off the Sphinx.

#napoleon bonaparte#napoleon#bonaparte#joaquin phoenix#movie time#napoleon movie#ridley scott#napoleon the movie#my thoughts#my musings#thanks for your attention

68 notes

·

View notes

Photo

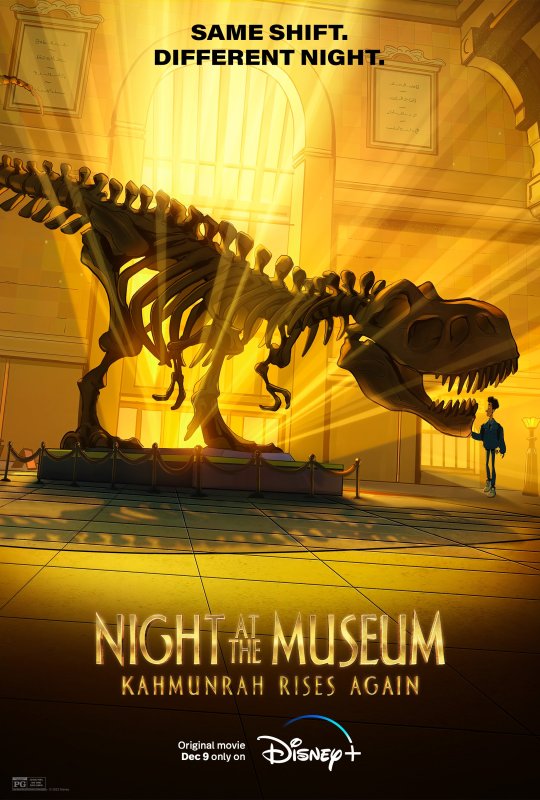

Walt Disney Pictures Unveils Trailer and Key Art Of Night At The Museum: Kahmunrah Rises Again.

Same Shift, Different Night

The 10-day countdown to the debut of the Original Movie Night at the Museum: Kahmunrah Rises Again is on, and to celebrate, Disney+ released the trailer and poster for the all-new animated adventure. Based on the popular film franchise, Night at the Museum: Kahmunrah Rises Again debuts exclusively on Disney+ on December 9, 2022.

Every night at the American Museum of Natural History when the sun goes down. Nick Daley’s summer gig as night watchman at the museum is a challenging job for a high school student, but he is following in his father’s footsteps and is determined not to let him down. Luckily, he is familiar with the museum’s ancient tablet that brings everything to life when the sun goes down and is happy to see his old friends, including Jedediah, Octavius, and Sacagawea, when he arrives. But when the maniacal ruler Kahmunrah escapes with plans to unlock the Egyptian underworld and free its Army of the Dead, it is up to Nick to stop the demented overlord and save the museum once and for all.

Night at the Museum: Kahmunrah Rises Again features the voices of Joshua Bassett (High School Musical The Musical: The Series),Jamie Demetriou ( Warner Bros Barbie,Dead End: Paranormal Park),Alice Isaaz (Savage state), Gillian Jacobs (Invincible),Joseph Kamal (Call Of Duty:Blac Ops III), Thomas Lennon (20th Century Studios Night At The Museum Trilogy), Zachary Levi (Tangled Franchise), Akmal Saleh (Tracey McBean), Kieran Sequoia (Netflix’s Daybreak),Jack Whitehall (Jungle Cruise), Bowen Yang (Fire Island), and Steve Zahn (20th Century Family’s & 20th Century 2000 Pictures Diary of a Wimpy Kid Trilogy)

Night at the Museum: Kahmunrah Rises Again is directed by Matt Danner (Legend Of The Three Caballeros) the writers are Ray DeLaurentis & Will Schifrin (Nickelodeon’s The Fairly Odd Parents); the producer is Shawn Levy (20th Century Studios Night At The Museum Trilogy); the executive producers are Emily Morris, Chris Columbus, Mark Radcliffe, and Michael Barnathan; and the music is by John Paesano (20th Century Animation’s Diary Of A Wimpy Kid Franchise).

Night at the Museum: Kahmunrah Rises Again is produced by 20th Century Animation & Atomic Cartoons in association with 21 Laps Entertaiment and Alibaba Pictures with Walt Disney Pictures being the distributor.

youtube

#Night at the Museum#Night At The Museum: Kahmunrah Rises Again.#Night At The Museum Kahmunrah Rises Again.#Matt Danner#Ray DeLaurentis#Will Schifrin#Shawn Levy#20th Century Animation#Walt Disney Pictures#Disney+#Disney Plus#Disney+ Originals#Disney Plus Originals#Disney+ Original Movies#Disney Plus Original Movies#Disney+ Original Animated Movies#Disney Plus Original Animated Movies

339 notes

·

View notes

Text

Portrait of Monsieur G. Giving his Daughter a Geography Lesson, 1812, Napoleonic era

Louis-Léopold Boilly, French

“This portrait was shown in 1812 and in 1814 at the Paris Salon, the highly publicized, state-sponsored exhibition of contemporary art. Boilly titled the painting M[onsieur] G* * * giving his daughter a geography lesson; the sitter, whose identity remains unknown, was likely a Napoleonic administrator. Historical geography was promoted as a field of study for both boys and girls in Napoleonic France, whose maps were subject to frequent revision with each new conquest. Here the sphinx and pyramid in the cartouche of the map no doubt refer to Napoleon’s Egyptian expedition of 1798–1801; the globe shows Europe and Africa. The fine detail of the Geography Lesson is indebted to Dutch domestic genre paintings of the seventeenth century, many incorporating maps and books into middle-class homes. Boilly himself had a notable collection of works by Dutch masters such as Gerard Terborch and Gabriel Metsu.”

Source: Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas

#Kimbell Art Museum#Louis-Léopold Boilly#boilly#painting#napoleonic era#napoleonic#napoleon#louis leopold boilly#first french empire#history#19th century#1800s#french empire#france#French art#art#genre art#1800s art#fine art

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

If you had told me that there was a three and half thousand year old Egyptian obelisk in Central Park I would have thought you were crazier than some of the people I’ve encountered in Harlem. But now that I’ve seen it with my very own eyes I guess I have no choice but to believe it…

The Obelisk (known as Cleopatras Needle) was created around 1425 BC in Heliopolis - an area north of modern day Cairo in Egypt - but now sits upon a rocky hill known as the Greywacke Knoll located behind the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This is the third place that this 220 ton monolith could call home. Originally it was located at the Temple of the Sun in Heliopolis after having been commissioned by Pharaoh Thutmose III and subsequently carved out of a single piece of stone.

When the ancient Romans discovered it in 12 BC it had toppled over and was partially buried in the sand. The Romans then transported it to Alexandria and built the bronze crabs that act as supports for the damaged obelisk before having it installed at the entrance to a temple dedicated to Julius Caesar - a temple which had been built by Cleopatra (hence the name Cleopatra’s Needle)

It then found its way to NYC in the 1870s when the Egyptian government gifted the obelisk to the United States in commemoration of the opening of the Suez Canal.

60 notes

·

View notes

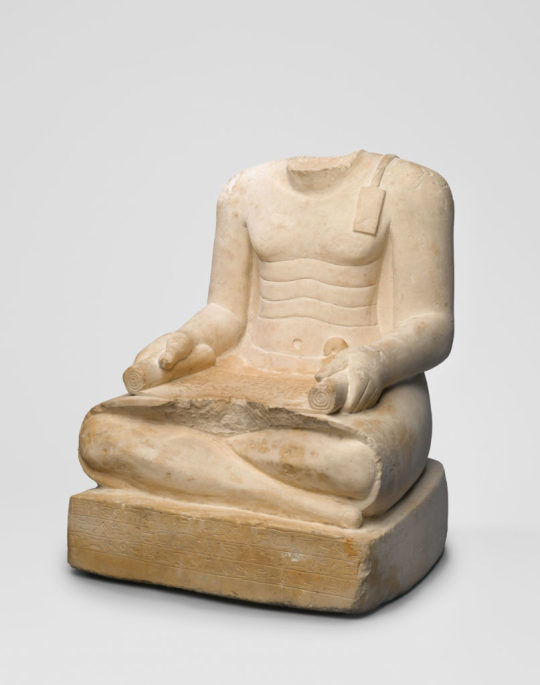

Text

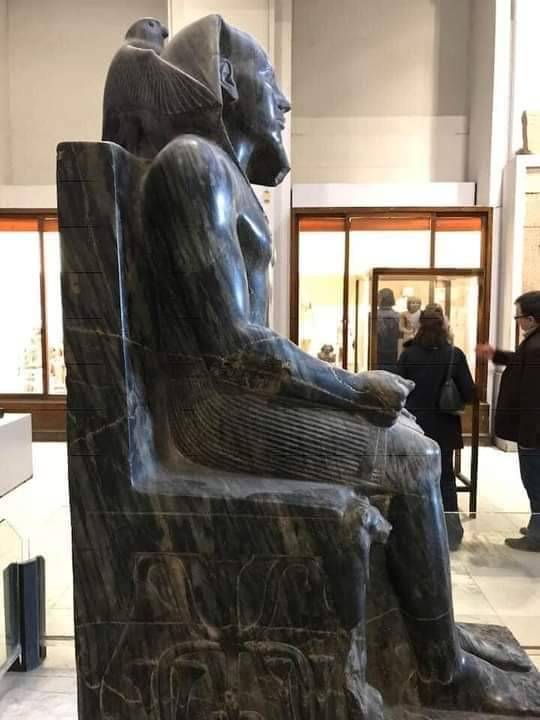

Statue of King Khafre

This statue of "Auguste Marit" was found in his valley temple in Giza. It dates back to the ancient state "Fourth Dynasty".

Let's know who is King Khafre 👇

He is the owner of the second largest pyramid in Giza and it is called the Pyramid of Khafre. He is the son of King Khufu, the owner of the Great Pyramid. He ruled for 25 years and built his funeral group in Giza.

This statue is one of the most prominent pieces of art in the Egyptian Museum. The king appeared seated in an official form on the throne, wearing a nemes hair cover, and adorning his forehead with a royal uraeus for protection, and wearing a royal false beard. He appears wearing a short royal apron.

The king is depicted placing his left hand on his knee and the right hand on the knee as well, but he is held and holding a piece of leopard skin with it. Opinions differ about what he holds in his hand, either a handkerchief or a papyrus, and some believe that it is a legal document of his sitting on the throne. Here the statue appeared through his looks and his body in a position of strength and firmness, and the artist drew a simple smile on his lips, and the artist excelled in showing him the ideal form of the king and the muscles of his body.

Standing behind the head of the falcon King Horus, spreading his wings

On the legs of the throne seat appeared the form of lions for protection, as well as the two sides of the throne, the symbol of unity that appears in the form of a trachea and two lungs, and the papyrus and lotus were linked to them, symbolic of the tribal and marine face. The name of Khafre and his titles such as “Khafre, the master of the crowns” were engraved on the throne’s base.❤️🇪🇬

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

A major interest in that work [...] was the era of post-war decolonization, and how archaeology connected with it (or not). As the territory of what became the Arab Republic of Egypt emerged from various forms of British rule and Egyptian monarchy, I wanted to know how that process impacted upon archaeology, a field that had been dominated by Euro-Americans (and whose major official institution, the Egyptian Antiquities Service, had been run entirely by French men). [...] The book revolves around, but is not limited to, a major event in the development of what became World Heritage, at least in UNESCO’s -- and, put bluntly, many other people’s -- telling.

UNESCO promotes its International Campaign to Save the Monuments of Nubia, which took place in the adjoining regions of Egyptian and Sudanese Nubia from 1960 until 1980, as central to the development of the 1972 World Heritage Convention. The campaign -- to a large, but not total, extent staffed by teams from the Euro-American institutions who had long excavated in Egypt -- sought to preserve and record ancient temples and archaeological sites in Nubia. Those sites were due to be flooded by the construction of the Aswan High Dam, which, despite having been planned many years earlier, became a centerpiece of Nasser-era modernization plans. Among them the temples at Abu Simbel and Philae, the monuments on the Egyptian -- but not Sudanese -- side of the Nubian border were listed as part of the second tranche of World Heritage sites in 1979, and today Nubian temples are located around the world: “gifts-in-return” for financial contributions to UNESCO’s project, perhaps most famous among them the temple of Dendur at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The World Heritage Convention, meanwhile, remains the major international piece of legislation in the heritage arena, and at the time of writing has been ratified by 194 States Parties. Oddly, however, beyond an official history published in the 1980s, there has never been a book-length, critical treatment of the Nubian campaign, nor have the articles and book chapters written about the event really addressed it in terms of the “local” (which is to say Egyptian and Sudanese) perspective, let alone the Nubian one.

Flooded Pasts discusses how, in combination with the politics of irrigation and development, UNESCO’s Nubian campaign built on and transformed colonial-era archaeological understandings of Nubia as a region of picturesque ruination: a place filled with ancient, Nile-side ruins, and not a place where people -- Nubians -- lived.

---

During the early decades of the twentieth century (and before and after the British declaration of nominal Egyptian independence in 1922), the building and heightening of the original Aswan Dam had, to increasingly destructive levels, flooded Nubian settlements on the Egyptian side of the Nubian border. These settlements were located alongside the many ancient ruins located in the region, which were also increasingly submerged. Eventually receiving some compensation from the Egyptian government, Nubia’s population were forced to move their homes higher up the Nile’s banks, and many Nubians moved to Cairo and Alexandria to work in domestic service. Meanwhile, Egypt’s antiquities service launched two archaeological surveys directed by colonial officials that sought to record ancient sites before they were flooded.

This process, I argue, made it much easier to separate an ancient Nubian past from the region’s present: one dominated by a territorially novel kingdom of Egypt whose permanence was extrapolated backwards in time.

---

Accordingly, as Egypt and Sudan signed the Nile Waters Agreement of 1959 and confirmed the impending construction of the High Dam, that process precipitated a continuation of earlier archaeological work [...]. Simultaneously, separate “ethnological” surveys either side of the newly hardened Egyptian-Sudanese border prepared for the relocation of the now-separated Nubian population to new, government-planned settlements elsewhere (the Egyptian survey was supported by the Ford Foundation and based at the American University in Cairo; the Sudanese one was supported by the Sudan Antiquities Service).

Even in the face of Nubian demonstrations -- particularly strong in Wadi Halfa in the very north of Sudan -- this forced, state-backed process of migration made the job of archaeological survey easier, constituting further representations of the desolate desert dotted by ancient monuments that earlier work had made possible.

That those monuments -- and that “desert” -- clearly had a far more complex history was a fact elided by most involved.

To a great extent, too, that elision continues, even as the Nubian diaspora has in recent years become much more vocal about its plight. [...]

---

[T]here is no doubt that the Nubian campaign, and the Nubian archaeological surveys before it, affected tens of thousands of lives for the worse. [...] I would hope that Flooded Pasts enjoys a readership beyond the academic, not least because issues around heritage -- what it is, who has a say in it, how its governance operates -- have become so salient in the last few years [...]. There has been a growing amount of work on the histories of archaeology and heritage -- and a corresponding amount of discussion around what it might mean to decolonize those fields [...]. More pressingly, then, I hope that the book catalyzes discussion around the lives of contemporary Nubians [...].

---

All text above are the words of William Carruthers. As interviewed by staff at the Jadaliyya e-zine. Transcript titled “William Carruthers, Flooded Pasts: UNESCO, Nubia, and the Recolonization of Archaeology (New Texts Out Now).” Published online at Jadaliyya. 22 December 2022. [Image from the cover of the book. Bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me.]

#orientalism#deserts are not empty#this is exactly what ann laura stoler talks about in Imperial Debris#about especially victorian and early 20th century scientists and historians having#socalled imperial nostalgia for ruins and ruination#ecology#abolition#imperial#colonial

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sculpture of Antony and Cleopatra's twin babies

A Sculpture that has been idling in a museum for ages. Egyptologist Giuseppina Capriotti of the Italian National Research Council believes a statue in the Cairo Museum depicts the twin children of Mark Antony and Cleopatra, Alexander Helios and Cleopatra Selene. The sandstone statue was discovered near the temple of Hathor in Dendera on the west bank of the Nile in 1918. Cleopatra VII is known to have commissioned works in that temple, most famously a monumental pharaonic relief of herself and her son by Julius Caesar, Ptolemy XV Philopator Philometor Caesar, aka Caesarion.

The Cairo Museum bought the five-foot-tall statue but didn’t pay it a great deal of attention, thinking it a representation of the twin gods Shu and Tefnet, son and daughter of the sun god Atum-Ra.

The statue is of two nude children, one male, one female, who bear the attributes of sun and moon respectively. They have an arm over each other’s shoulders while they hold a serpent in their other hands. The coils of two snakes wind around their legs and the base of the statue.

Capriotti noticed that the boy has a sun-disc on his head, while the girl boasts a crescent and a lunar disc. The serpents, perhaps two cobras, would also be different forms of sun and moon, she said. Both discs are decorated with the udjat-eye, also called the eye of Horus, a common symbol in Egyptian art.

“Unfortunately, the faces are not well preserved, but we can see that the boy has curly hair and a braid on the right side of the head, typical of Egyptian children. The girl’s hair is arranged in a way similar to the so-called melonenfrisur (melon coiffure) an elaborated hairstyle often associated with the Ptolemaic dynasty, and Cleopatra particularly,” said Capriotti.

The statue dates to between 50 and 30 B.C. Mark Antony and Cleopatra’s twins were born in 40 B.C. so the timing fits, but it’s the unusual iconographic choices which suggest this is not just a statue of Shu and Tefnet. In the Egyptian pantheon, Tefnet, the sister, wears the solar disk, but in this piece the female twin wears the crescent moon and the male wears the sun, in keeping with the Greek tradition of the female moon goddess Selene and the male incarnation of the sun, Helios.

The twins’ embrace could suggest a solar eclipse, which is significant because when Mark Antony officially recognized the twins as his children three years after their birth, the event was marked by a solar eclipse. That’s when Cleopatra changed their names from plain Cleopatra and Alexander to Cleopatra Selene and Alexander Helios.

If these are Antony and Cleopatra’s twins, it’s the first representation of the two together ever discovered. The only other image we have is of an adult Cleopatra Selene on coins minted during her reign as Queen of Mauretania. Alexander Helios does not appear to have survived into adulthood, nor his younger brother Ptolemy Philadelphus.

After their parents’ suicides, all three of Antony’s children by Cleopatra were taken to Rome by Octavian in 30 B.C. to march in his triumph as royal captives in gold chains. He handed the three of them over to his sister Octavia, Antony’s third wife, to raise. The boys disappear from the historical record, perhaps dead at Augustus’ hand. Cleopatra Selene, on the other hand, was married around 20 B.C. to King Juba of Mauretania, a north African client state.

#alexander helios#cleopatra selene#mark antony#marcus antonius#cleopatra#cleopatra vii#antony and cleopatra#ancient egypt#rome#cairo egyptian museum#art history#ptolemaic egypt#ptolemaic dynasty#history

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Hello! If you are interested in Egyptology and the Fayum “mummy portraits,” do I have the virtual event for you! This event is on Zoom and completely free.

Face to Face: Conservation Research on 'Mummy Portraits' in the Detroit Area

February 28th at 6:30 PM

Virtual event on Zoom

Join us for an evening of conversation with conservators Caroline Roberts and Ellen Hanspach-Bernal who will be sharing their research on Egyptian "mummy" panel portraits at the Kelsey Museum of Archaeology and the Detroit Institute of Arts.

Register via link http://bit.ly/3JSJb7F

Speaker Profiles:

Caroline Roberts

Talk title: Reengaging with Roman Egyptian portraits and panel paintings through technical research at the Kelsey Museum

Bio: Caroline Roberts is an archaeological conservator and a graduate of the Winterthur / University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation. Carrie’s professional background includes post-graduate fellowships at the Kelsey Museum of Archaeology at the University of Michigan, the J. Paul Getty Museum, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Her research interests include the conservation of stone artifacts and architecture in museum and field settings, the characterization of ancient polychromy, and preventive conservation. Carrie’s conservation fieldwork experience includes seasons at Kaman-Kalehöyük in Turkey, Selinunte in Sicily, El-Kurru in Sudan, and Abydos in Egypt. She is a Professional Associate of the American Institute for Conservation.

Ellen Hanspach-Bernal

Talk title: Deconstructing an Ancient Egyptian Mummy Portrait at the Detroit Institute of Arts

Bio: Ellen Hanspach-Bernal is a 2006 graduate of the art conservation program at the Hochschule für Bildende Künste, Dresden. From 2006 to 2009 she was the Andrew W. Mellon Fellow in painting conservation at the Menil Collection in Houston, Texas. She has worked for Klassik Stiftung Weimar and for the Conservation Centre for the Museums of the City of Erfurt, Thüringen, in Germany. In 2015 she returned to the United States to work as Conservator of Paintings at the Detroit Institute of Arts.

Image credit: 25.2, Egyptian, Head of a Woman at the Detroit Institute of Arts

#fayum mummy portraits#fayum#Egypt#egyptology#Ancient Egypt#faiyum#Egyptian Archaeology#archaeology#faiyum mummy portraits

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

For when you can't decide between #FishFriday and #FrogFriday:

David Gilhooly (American, 1943-2013)

Merfrog and her Pet Fish, 1979

white earthenware & glazes, 7 x 6 x 7 3⁄8 in. (17.8 x 15.2 x 18.7 cm)

Smithsonian American Art Museum & Renwick Gallery 2007.47.12

"David Gilhooly made his first ceramic frog during a friendly mug-making competition among classmates at the University of California–Davis. This inspired the artist to create a whole civilization composed entirely of frogs, ranging from Napoleon-inspired frog busts to frog-Egyptian gods. Gilhooly originally thought about making pigs, but decided not to, stating: "The trouble with making a PigWorld rather than the FrogWorld was that pigs are 'loaded.' That is, people have a lot of negative ideas that are attached to pigs...." In Merfrog and her Pet Fish, Gilhooly refers to one of his favorite themes, fertility, by creating an absurdly voluptuous frog surrounded by devoted singing companions." (Artist's website, www.davidgilhooly.com, January 2006)

#animals in art#20th century art#David Gilhooly#sculpture#frog#fish#Frog Friday#Fish Friday#American art#Smithsonian American Art Museum#fantastic creatures#frogworld#ceramics#pottery

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

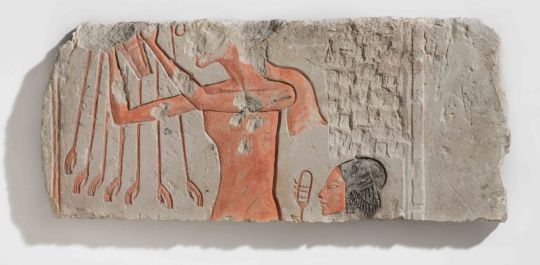

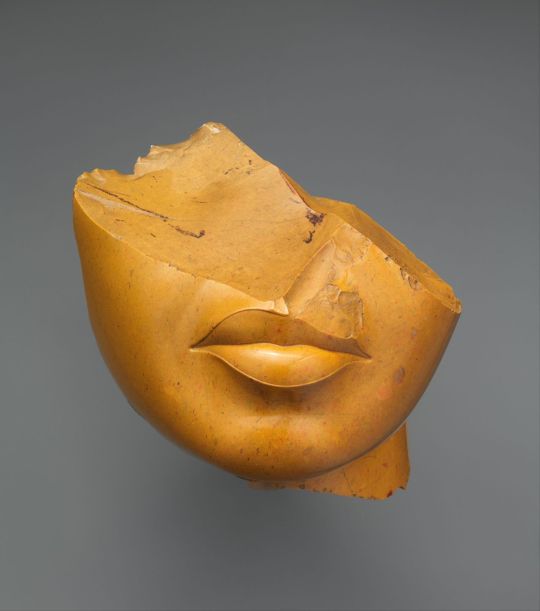

Why Do So Many Egyptian Statues Have Broken Noses?

The most common question that curator Edward Bleiberg fields from visitors to the Brooklyn Museum’s Egyptian art galleries is a straightforward but salient one: Why are the statues’ noses broken?

Bleiberg, who oversees the museum’s extensive holdings of Egyptian, Classical and ancient Near Eastern art, was surprised the first few times he heard this question. He had taken for granted that the sculptures were damaged; his training in Egyptology encouraged visualizing how a statue would look if it were still intact.

It might seem inevitable that after thousands of years, an ancient artifact would show wear and tear. But this simple observation led Bleiberg to uncover a widespread pattern of deliberate destruction, which pointed to a complex set of reasons why most works of Egyptian art came to be defaced in the first place.

Bleiberg’s research is now the basis of the poignant exhibition “Striking Power: Iconoclasm in Ancient Egypt.” A selection of objects from the Brooklyn Museum’s collection will travel to the Pulitzer Arts Foundation later this month under the co-direction of the latter’s associate curator, Stephanie Weissberg. Pairing damaged statues and reliefs dating from the 25th century BC to the 1st century AD with intact counterparts, the show testifies to ancient Egyptian artifacts’ political and religious functions – and the entrenched culture of iconoclasm that led to their mutilation.

In our own era of reckoning with national monuments and other public displays of art, “Striking Power” adds a germane dimension to our understanding of one of the world’s oldest and longest-lasting civilizations, whose visual culture, for the most part, remained unchanged over millennia. This stylistic continuity reflects – and directly contributed to – the empire’s long stretches of stability. But invasions by outside forces, power struggles between dynastic rulers and other periods of upheaval left their scars.

“The consistency of the patterns where damage is found in sculpture suggests that it’s purposeful,” Bleiberg said, citing myriad political, religious, personal and criminal motivations for acts of vandalism. Discerning the difference between accidental damage and deliberate vandalism came down to recognizing such patterns. A protruding nose on a three-dimensional statue is easily broken, he conceded, but the plot thickens when flat reliefs also sport smashed noses.

The ancient Egyptians, it’s important to note, ascribed important powers to images of the human form. They believed that the essence of a deity could inhabit an image of that deity, or, in the case of mere mortals, part of that deceased human being’s soul could inhabit a statue inscribed for that particular person. These campaigns of vandalism were therefore intended to “deactivate an image’s strength,” as Bleiberg put it.

Tombs and temples were the repositories for most sculptures and reliefs that had a ritual purpose. “All of them have to do with the economy of offerings to the supernatural,” Bleiberg said. In a tomb, they served to “feed” the deceased person in the next world with gifts of food from this one. In temples, representations of gods are shown receiving offerings from representations of kings, or other elites able to commission a statue.

“Egyptian state religion,” Bleiberg explained, was seen as “an arrangement where kings on Earth provide for the deity, and in return, the deity takes care of Egypt.” Statues and reliefs were “a meeting point between the supernatural and this world,” he said, only inhabited, or “revivified,” when the ritual is performed. And acts of iconoclasm could disrupt that power.

“The damaged part of the body is no longer able to do its job,” Bleiberg explained. Without a nose, the statue-spirit ceases to breathe, so that the vandal is effectively “killing” it. To hammer the ears off a statue of a god would make it unable to hear a prayer. In statues intended to show human beings making offerings to gods, the left arm – most commonly used to make offerings – is cut off so the statue’s function can’t be performed (the right hand is often found axed in statues receiving offerings).

“In the Pharaonic period, there was a clear understanding of what sculpture was supposed to do,” Bleiberg said. Even if a petty tomb robber was mostly interested in stealing the precious objects, he was also concerned that the deceased person might take revenge if his rendered likeness wasn’t mutilated.

The prevalent practice of damaging images of the human form – and the anxiety surrounding the desecration – dates to the beginnings of Egyptian history. Intentionally damaged mummies from the prehistoric period, for example, speak to a “very basic cultural belief that damaging the image damages the person represented,” Bleiberg said. Likewise, how-to hieroglyphics provided instructions for warriors about to enter battle: Make a wax effigy of the enemy, then destroy it. Series of texts describe the anxiety of your own image becoming damaged, and pharaohs regularly issued decrees with terrible punishments for anyone who would dare threaten their likeness.

Indeed, “iconoclasm on a grand scale…was primarily political in motive,” Bleiberg writes in the exhibition catalog for “Striking Power.” Defacing statues aided ambitious rulers (and would-be rulers) with rewriting history to their advantage. Over the centuries, this erasure often occurred along gendered lines: The legacies of two powerful Egyptian queens whose authority and mystique fuel the cultural imagination – Hatshepsut and Nefertiti – were largely erased from visual culture.

“Hatshepsut’s reign presented a problem for the legitimacy of Thutmose III’s successor, and Thutmose solved this problem by virtually eliminating all imagistic and inscribed memory of Hatshepsut,” Bleiberg writes. Nefertiti’s husband Akhenaten brought a rare stylistic shift to Egyptian art in the Amarna period (ca. 1353-36 BC) during his religious revolution. The successive rebellions wrought by his son Tutankhamun and his ilk included restoring the longtime worship of the god Amun; “the destruction of Akhenaten’s monuments was therefore thorough and effective,” Bleiberg writes. Yet Nefertiti and her daughters also suffered; these acts of iconoclasm have obscured many details of her reign.

Ancient Egyptians took measures to safeguard their sculptures. Statues were placed in niches in tombs or temples to protect them on three sides. They would be secured behind a wall, their eyes lined up with two holes, before which a priest would make his offering. “They did what they could,” Bleiberg said. “It really didn’t work that well.”

Speaking to the futility of such measures, Bleiberg appraised the skill evidenced by the iconoclasts. “They were not vandals,” he clarified. “They were not recklessly and randomly striking out works of art.” In fact, the targeted precision of their chisels suggests that they were skilled laborers, trained and hired for this exact purpose. “Often in the Pharaonic period,” Bleiberg said, “it’s really only the name of the person who is targeted, in the inscription. This means that the person doing the damage could read!”

The understanding of these statues changed over time as cultural mores shifted. In the early Christian period in Egypt, between the 1st and 3rd centuries AD, the indigenous gods inhabiting the sculptures were feared as pagan demons; to dismantle paganism, its ritual tools – especially statues making offerings – were attacked. After the Muslim invasion in the 7th century, scholars surmise, Egyptians had lost any fear of these ancient ritual objects. During this time, stone statues were regularly trimmed into rectangles and used as building blocks in construction projects.

“Ancient temples were somewhat seen as quarries,” Bleiberg said, noting that “when you walk around medieval Cairo, you can see a much more ancient Egyptian object built into a wall.”

Such a practice seems especially outrageous to modern viewers, considering our appreciation of Egyptian artifacts as masterful works of fine art, but Bleiberg is quick to point out that “ancient Egyptians didn’t have a word for ‘art.’ They would have referred to these objects as ‘equipment.’” When we talk about these artifacts as works of art, he said, we de-contextualize them. Still, these ideas about the power of images are not peculiar to the ancient world, he observed, referring to our own age of questioning cultural patrimony and public monuments.

“Imagery in public space is a reflection of who has the power to tell the story of what happened and what should be remembered,” Bleiberg said. “We are witnessing the empowerment of many groups of people with different opinions of what the proper narrative is.” Perhaps we can learn from the pharaohs; how we choose to rewrite our national stories might just take a few acts of iconoclasm.

By Julia Wolkoff.

#Why Do So Many Egyptian Statues Have Broken Noses?#statues#egyptian sculpture#egyptian statues#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#ancient egypt#egyptian history#egyptian art#long reads

50 notes

·

View notes

Note

Versace should partner up with the new egyptian state museum and have king tut strut down the catwalk on top of a boston dynamic ammit while wearing designer mummy bandages

I'm going to hunt you down and cut you apart like art

61 notes

·

View notes