#yong’an

Text

Xiao Xingchen is an interesting character, but he’s not entirely unique in his disposition and subsequent downfall. The most obvious parallel is the one that Wei Wuxian makes between himself and Xiao Xingchen (“In that moment, Wei Wuxian saw himself in Xiao Xingchen…” pg. 156). However, Xiao Xingchen has a lot in common with Xie Lian, specifically his first ascension and fall. Everything that Xue Yang says to Xiao Xingchen in their final confrontation can be said of Xie Lian.

Xue Yang says, “if you don’t know how this works works, then don’t enter it” (153). This sums up the criticism Xie Lian largely received when interfering in the Xianle/Yong’an war. He didn’t understand that you can’t walk away from a war with no casualties, and he didn’t understand how to effectively govern a kingdom. Furthermore, the Holy Temple in which he trained was literally on a mountain, much like Xiao Xingchen’s origins.

Xue Yang says, “save the world! What a joke, you can’t even save yourself!” and “you’ve accomplished nothing! Failed utterly! You only have yourself to blame! You reap what you sow!” (156). This is fairly self-explanatory in the context of Xie Lian’s first fall from grace and the period of struggle directly after.

The fact that Xiao Xingchen parallels two of the MXTX protagonists is interesting. I very vaguely remember hearing that the Xiao Xingchen story was something MXTX had come up with in high school. Then, it makes sense that his character is as such, and might point to somewhat formulaic (not that it’s bad) writing on the part of MXTX.

Thought complete, goodbye.

#mdzs#tgcf#xie lian#mxtx#mxtx novels#heaven official's blessing#the grand master of demonic cultivation#xiao xingchen#xue yang#wei wuxian#wei ying#daozhang#mxtx meta#xianle#crown prince of xianle#yong’an

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

i've been wanting to show off my crown prince design since november of last year lmao / follow for more xianle epic fail compilations

#i started drawing taizi dianxia and this meme popped into my head#the second panel is based off of the time the trio spent in the quarantine zone before xianle fell#when xl was trying to figure out the cure for the human face disease and bringing rain to yong’an#lemme find my favorite quotes from this book#its either#Your Highness#why do you think you can achieve anything you want to do? Rather than putting my fate in your hands#I choose to put it in my own.#… Throughout all their past meetings#this was the very first time Xie Lian had steeled his heart to kill Lang Ying.#orrrr#You don’t have a third path amd there is no second cup of water. Wake up#Your Highness! You’re running out of time.#tgcf#heaven official’s blessing#tian guan ci fu#tgcf meme#xie lian#hob#lmao#art#digital art#my art#doodle#tgcf spoilers#blood

815 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi 👋. Saw your recent take on how fandom interpret MQ. And I would to here your thoughts about him being the tsundere people try to make him out to be.

MQ trying to make it up to XL when really FX was the only one still sincere. I've only read up to vol. 4 and reread vol. 1 and 2 to get a better look at details. But there are some concerning lines that even XL noticed. Like MQ seems excited at the prospect of XL becoming this mass murder during the Guoshi FangXin reveal. Even the first introductions in the book was him mocking XL's helpful nature.

"Mu Qing’s eyes were glimmering, however, and his

restrained shock contained a faint underlying excitement." TGCF Vol. 2 chapter 18

"Since his third ascension, there could only be one phrase to describe the

way Mu Qing treated him: passive-aggressive. It always felt like he was waiting

for Xie Lian to get booted for the third time so he could make snide remarks. Yet

now that Xie Lian might actually get booted that third time, he suddenly became

pleasant—he even came specially to deliver medication. This complete reversal

in attitude made Xie Lian feel quite disconcerted." TGCF Vol.2 chapter 19

Even XL was freaked out by MQ acting nice to him.

"Mu Qing suddenly asked, “Was everything Lang Qianqiu said true? Did

you really kill those Yong’an royals?”

Xie Lian looked up and met his gaze. Even if Mu Qing had been forcibly

hiding it, Xie Lian still detected a trace of uncontrollable excitement in his eyes.

He seemed highly interested in the details of Xie Lian’s massacre at the Gilded

Banquet—he followed with another question.

“How did you kill them?” TGCF Vol. 2 chapter 19

And after XL half lied about his involvement.

"Feng Xin paled. Mu Qing loathed that expression of his the most and said

in annoyance, “All right, put that face away. After everything, for who are you

looking so pained?”" TGCF vol. 2 chapter 19

I'm not reading this wrong to think MQ is just a very entitled b****** that got high on his position of power and is looking down on XL for coming from a place which is lower than what most people would go through? Is it appropriate for me to interpret him being downright hostile and reveling in XL's disgrace? Because the stans take for MQ questionable character is bothering me a lot. He is not some prickly cat with a soft heart. He is sharp thorns all the way inside and a heart colder than most.

Unless something changes in further volumes I haven't read which is unlikely. Considering MXTX penchant for consistent character writing.

Thoughts?

Something does change about Mu Qing’s character near the end of the novel, but it’s just character growth. You aren’t misreading any of his actions in the earlier parts of the story. What kills me is that yes, Mu Qing is a terrible person who is petty and jealous and insecure and thinks that the only problem with hierarchy is that he isn’t at the top, but he changes and people ignore that! In the best interest of not introducing spoilers, I will say that Mu Qing does explicitly, using clear language, acknowledge his mistakes and how wrong he was about how he viewed Xie Lian and his treatment of the other man. He acknowledges this on his own under no threat and with no prompting. And people ignore this because it does not fit into their perception of Mu Qing as either right or at least well-meaning. He is neither of those things. He knows it. Xie Lian knows it. But he can be those things if he puts effort into it, and for all people call me a hater about his character (which, yeah lol), I for one think he tries by the end.

So no, Mu Qing isn’t a tsundere because he’s not being mean or rude or petty to those he loves to hide a mushy middle. He’s doing it because he thinks he is right to and that eventually people will see that he is right. The story does not agree he is right and duly punishes him for his fuckery, and he changes into a better person who is actually nicer to his friends because he wants to be their friends and not their superiors. That’s his character.

#tgcf asks#anon#and yeah mq was weirdly happy about the idea of xl committing a massacre#he is weirdly obsessed with the idea of xl going on a killing spree#cause he hasn’t gotten over xl telling HIM that genociding the people of yong’an just because they were fighting them was wrong#but don’t worry#mq gets what’s coming to him#i hope you enjoy that part when the volume drops anon

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eight eps into Yongan Dream and the word “mid” was invented for this drama.

(Which is still several orders of magnitude better than what I thought it was going to be like based on trailers.)

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

i’ve only read chapter 1 of book 3 but it’s already like. i feel like i’m watching a car crash in slow motion they’re like “oh my god look at how amazing xie lian is!! look at how incredible his kingdom is! look at all his followers and his temples look look!!” and it’s like girl you and i both know that this is going to end horribly. it’s just a matter of waiting for when and how this car is going to flip and roll down a hill into a thorny ravine that’s also on fire

#i’m so curious as to what happens#like i know it’s bc of him getting involved with yong’an and everything but i wanna know the exact details#like this man is about to go to war and die and watch his kingdom fall and i need to see it happen in hd#tgcf#mine

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

xie lian practising swordsmanship =/= being violent.

#he is the strongest martial god and uses these skills by fighting off demons and other vermin#afaik he only killed once and that was the king of yong’an#in order to prevent the massacre of xianle#anyways just bc xl can wipe the floor doesnt necessarily mean he will#he vowed a life of pacifism and over and over again showed his determination in this#minus qirong. qirong got his shit rocked

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

LISTEN shi qingxuan is not simply a victim of he xuan.

the black water arc is telling a story that complicates notions of victim and abuser, which fits very well into the exploration of that theme in the novel as a whole. Think of the entire political conflict that happens between yong’an and xian le – who is the guilty party? They both are, but they are also both justified. It’s complicated and paradoxical, nuanced and difficult. Of He Xuan and Shi Qingxuan who is the victim? They both are. Who is the perpetrator? They both are.

And it’s very interesting that many readers of the black water arc, like the characters in tgcf responding to these moments, like the common people praising xie lian at one moment and destroying his temples the next, select the details that affirm the one they favour and condemn the one they don’t, and ignore the nuance and complexity and contradiction that is actually there.

227 notes

·

View notes

Text

the parallels between qi rong and lang qianqiu and their relationship with xie lian are soooo interesting to me tbh…

both were young people who idolized xie lian and then became bitter towards him, the difference (until the events of this episode) is that qi rong’s bitterness towards xie lian turned into bitterness and disillusionment towards the whole world and shot him down the path of being evil and awful and full of desire for revenge…

while for lang qianqiu, xie lian taking on the blame for the golden banquet and suffering the consequences yes caused bitterness towards xie lian himself, but protected lang qianqiu’s hopeful view of the world and the future of the yong’an and xianle people… until it all comes out and lang qianqiu is just as consumed with a desire for revenge as qi rong is.

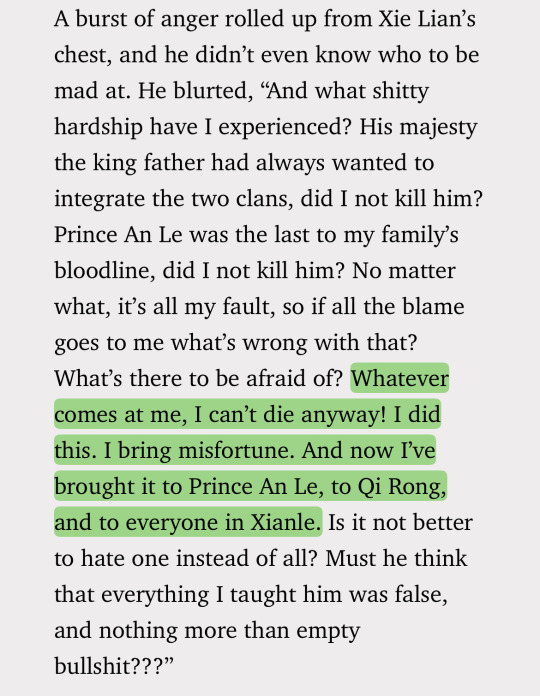

which leads to xie lian breaking down and i want to look at the novel passage in particular bc it emphasizes the way that he feels he is the one who brought misfortune to all of them… and so of course he should be to blame .

181 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fun headcanon: what if Hua Cheng’s silver butterflies are actually the Xianle resentful spirits that Xie Lian was about to unleash on Yong’an? Xie Lian taught them to hate, told them to despise these people who lived on while they died. What if Wu Ming, as he was torn apart, taught them to love? To love his highness the way he did?

110 notes

·

View notes

Text

Poisonous Grief

There are a lot of really fucked up things that happen in TGCF, but there’s one chain of events in particular that really just makes me sad. We like to talk a lot about the Human Face Disease, but I find it equally horrifying and sad that Lang Ying used his son as the source of the curse upon Xianle, desecrating both his body and soul in the process. Xie Lian talks about how the victims of the disease are innocents, and the first innocent to suffer is Lang Ying’s son. His son is described as being only two or three years old at his time of death. Shortly after the Human Face Disease emerges, Xie Lian and co. find the gravesite of Lang Ying’s son. Not only does it smell so rancid and rotten as to make many of those present vomit, it’s also swollen up so much that nevermind looking like a child’s body, it doesn’t look human at all! Lang Ying himself likely never saw what the curse did to his son’s body, but choosing to use his remains as the anchor for a curse speaks volumes as to his mental state and priorities at the time.

And it doesn’t get better. We all know what happens to Lang Ying in the end; he dies of Human Face Disease after either allowing or asking Bai Wuxiang to plant the resentful souls of his wife and child within him. But why is his son a resentful spirit? The spirits used in the Human Face Disease have strong animosity towards Xianle, but Lang Ying’s son was a toddler. He wasn’t old enough to know things like the difference between Yong’an and Xianle, why there was no food or water, or what it means to hate. His son lingers as a resentful spirit because, as Xie Lian explains, there’s a stage where the souls of the departed are confused and easily influenced by the sentiments of their families and lovers. Lang Ying’s resentment is so great as to twist his own child into a resentful spirit, not old enough to know right or wrong, but made to hate when he never knew how to in life.

And Lang Ying continues this desecration by forcing his son(and wife) to remain in this state, plastering the whole of his newly-obtained palace with defensive arrays to force his wife and son to remain with him, rather than depart and hopefully find peace. He is completely unable to let go of them, perverting the cycle of life and death by forcing them to linger. It is also very, very, super amazingly fucked up. Jesus Christ Lang Ying, your child is dead and yet you are somehow, posthumously, the worst father in the entire novel.

#illuspeaks#lang ying#tgcf#tian guan ci fu#heaven officials blessing#heaven official's blessing#hob#tgcf meta

118 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay. I need to talk about Xie Lian. This is gonna be a bit rambly, jumbled, and unedited because I am kinda sleep-deprived right now.

Out of every fictional character I’ve read about… Xie Lian stands out as possessing the most remarkable mental fortitude and resilience I’ve ever seen. He’s such a brave and stubborn man. He’s, well… a diamond in the rough.

I always thought him to be really mature for his age in the flashbacks. He was what, only around 16-17? And then after he descended down to save his kingdom, he was around the mental age of 20. He was barely an adult. Yet he had his whole kingdom’s fate on his shoulders, and the way he was treated was beyond horrible.

That’s the problem with getting assigned the role of a leader… a general even. The number of deaths, their successes, their losses all fall upon the one who had the most status, most importance. So many people blamed Xie Lian for the fall on Xianle, but really, none of that was on him. Xianle was gonna fall either way due to all the politics and strife. But my goodness. To put all that blame on a child??? It’s so despicable.

It made me terribly sad to see Xie Lian blame himself for what happened to Xianle and his people, when they were the ones who put him on a pedestal and did nothing to help ease his burdens. I think Xie Lian has natural charisma and could be a good leader, however he does not have the heart for it. He cares too much. He’s the type who wants to save everyone. He doesn’t like or want to see people suffer, even those considered his enemies.

Xie Lian suffers a lot. He goes through so much, goes to unimaginable suffering constantly for 800 years. However, the core message of the series is that Xie Lian, as an individual, has the power to decide his own fate. He has the power to decide to remain pure at heart in the face of immeasurable suffering and to not give into Bai Wuxiang’s manipulations.

His suffering can’t even be put into words. To be blamed for a whole kingdom dying. To blame himself for the horrifying Human-Face disease. Then he was banished and cursed and hunted by the Yong’an’s people. He became extremely depressed on top of trying to survive and take care of his parents each day. Mu Qing helped a lot, but he too eventually left. He resorted to stealing, which went completely against his morals. He was cornered by 33 Heavenly Officials, who humiliated and bullied him, Mu Qing being one of the people involved as well. All the while being haunted bu Bai Wuxiang, who’s truly a sadistic, unredeemable monster. Then he was brutally stabbed fatally hundreds of times in the most horrific way possible and the recovery-time was just two months of pain with the monster who made it all happen keeping him for company. Then Feng Xin left because Xie Lian changed too much, was too hurt and numb and lashed out.

Then his parents left him too in a way. And Xie Lian probably blames himself for that. So at that point, Xie Lian just craved death. But he couldn’t even die because of the cursed shackle.

But still. Still. Even after going after Lang Ying and having Wu Ming burn down the palace and could release the Human-Face disease all over the Yong’an kingdom.

He still chose to pin himself on the ground outside with the same sword that killed him hundreds of times… and waited for three whole days for one, just one person, one samaritan to help him. He still had a dredge of hope in humanity. In people. Because in the end, Xie Lian is an empathetic and kind person. He believes and has hope in people- because he is a pure-hearted person himself, and has to believe there are other people like him out there. Because he can’t be the only one. (He’s not, but a person like him is one out of millions.)

And deep inside he starts to believe Bai Wuxiang’s words when he come on the third day to convince him that this test/social experiment he was doing was pointless. That it is all so hopeless, and these people aren’t worth living, not after how much Xie Lian suffered at their hands.

But all it took was one person. He was waiting. To be proved wrong. He wanted to be proved wrong, even after everything. That truly… I don’t have words for how amazing that is.

And then. Even after 800 years of having literally nothing. 800 years of loneliness, suffering, and depression. Being nailed through the heart and buried alive for an undetermined time. Just so he could save more people again. He still remained the same. So pure of heart. So sweet and kind. He even asked for his second shackle to take away his luck so other people more “deserving” than him can take it.

He still has his problems. His mental health is terrible. He’s very depressed. He chose to stay in a coffin for what could be a hundred years because of self-flagellation probably.

He has no self-esteem, except he’s so interestingly contradictory. He loathes himself, but he also believes he’s completely right. If Xie Lian had to do everything over again, I have no doubt he would do the same thing, except the second-time, maybe blame himself less, because he knows deep down what he is doing is right. He has a simple, but strict moral code. All he wants to do is the right thing. That means saving the common people. Interfere and help if he sees someone suffering. If he can save one person, he will save one person. If he can save a hundred people, he will save a hundred people.

What a stubborn, beautiful person.

Book 8: “I won’t! I won’t I won’t change!”… He’s been pent up for far too long. It was as though he’d been waiting for a chance like this all these years, and tears rolled as he screamed. “I won’t change! Even if it’s painful, even if I die, I won’t change, I will never change!”

And he didn’t. He has more than proven that he won’t change even if he died a hundred times. He won’t change even if he died a million times. Even as a young adult, he stood in front of a whole village of people after experiencing what is it like to feel stabbed fatally hundred of times already and was ready to do it all over again willingly. With even more people, even a whole kingdom of people.

Insane does not even begin to cover it. What an extraordinary resilient and compassionate person.

Xie Lian is truly… something else. Something beyond words. He is also the only type of God I would willingly pray to.

I understand why Hua Cheng would go to any extent for him.

#tgcf#xie lian#xie lian rant#my favorite character#tian guan ci fu#heaven official's blessing#mo#mo xiang tong xiu#mxtx#brilliant character#analysis?

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Another semi-coherent rant on climate change, the value of idealism, and TGCF (I finally finished!)

Well, I finished Tian Guan Ci Fu. And, oh man, if you read my last post, you’ll know that I was terrified that the entire novel would be a criticism of blind idealism. But I am SO glad I was wrong!!! Looking back on what I wrote before… it’s kind of hilarious how worried I was. I was so sure that I knew where it was going, was so busy preparing myself to be offended/emotionally crushed, that I wouldn’t even entertain the idea that maybe MXTX had a similar worldview to me all along.

In my defense, aside from the line, “Something like saving the common people… although foolish, it is brave,” everything seemed to point toward the idea that trying to do good is pointless. I mean, up until the moment when Xie Lian was lying with a sword in his chest on the streets of Yong’an, all of his efforts to do good had essentially been in vain. He hadn’t been able to help anyone.

And then, when the one guy stopped and gave Xie Lian his hat, I dunno, I just cried. It was so perfect! Like, ugh, damn you, MXTX! So sneaky… destroying us, just to bring us back later!! It was such a small, insignificant win, but it was exactly what Xie Lian (and I) needed. I love the line, “Just one person was enough!” Just one person doing something selfless. It’s enough to give us hope.

It really resonates with me because I think a lot about how to maintain hope. In terms of the climate crisis, I feel like Xie Lian—completely powerless. I want to stop eating meat, use less plastic, spend more time on environmental activism, but honestly, what do any of these things matter? The meat industry is not going to change because I choose to stop consuming. Even my activism has a completely negligible effect—whether or not I join a protest or write a letter to my congressman will almost certainly not be the deciding factor for any climate legislation, no matter how much effort I put in.

And yet, I still want to. I love the moment when Xie Lian chooses to get stabbed over and over rather than create a second plague of Human Face Disease, and White No-Face asks him in shock, “Why??”—as in, why would you ever do that? And Xie Lian responds: “I don’t have a reason—just because I want to! Even if I explained it to you… Useless trash like you wouldn’t understand.” This line is so great. Xie Lian can’t explain it to White No-Face, because, in truth, it isn’t entirely logical. It can’t be explained by reason. I want to do my measly, unimportant part to help the world… because I want to. Because it feels right. Because it’s my way of keeping my heart, of maintaining faith that there is some good in this world worth upholding. (As an aside, I love how the English title of the live action drama—which we may never get to see, God damn censorship!!!!—is called “Eternal Faith.” Of course it refers to Hua Cheng and Xie Lian’s faith in each other, but I think it also means having eternal faith in the value of doing good, despite centuries of experience that seem to show its pointlessness.)

As I talked about in my last post, if you zoom out far enough, nothing really seems to matter. Everything we love and care about will one day be gone. And yet, I believe we still have to act like it matters. This is the basic tenant of existentialism, and I think MXTX portrays this philosophical paradox really beautifully.

It’s funny, because I think MXTX has a lot of profound things to say, but in an interview I read, she warned against viewing her work too deeply, saying, “I am not a guru.” I get that she may not want the responsibility of giving people spiritual advice, but I do think she presents some really fascinating, really novel, philosophical ideas. So, sorry MXTX, but I’m about to analyze TGCF like it’s a piece of freakin scripture. Soo here we go…

The main theme she comes back to again and again is that fortune is limited, so the only way you can do good for others is by taking fortune from somebody else. Which leads the characters to a bunch of ethically impossible choices: the people of Yong’an and the people of Xianle can’t all be saved (Xie Lian must choose who to help), neither can the people of Wuyong and the surrounding kingdoms (Prince of Wuyong must choose), and Shi Wudu can’t save his brother from a tragic fate without taking fortune from an innocent person. When the characters try to avoid choosing, and try to “play God” by creating a “third path,” it just invites disaster.

But is this really true? Is fortune actually limited? It’s an idea that reminds me of Buddhism and Daoism, but also seems kind of revolutionary… (I like to think I know something about Chinese philosophy but it could certainly be a thing and I don’t know). I don’t believe in fate, but I do believe in limited resources, and the idea that nature tends toward balance. I think conceiving of it this way, as a pool of fortune, is really interesting.

It reminds me of this Meme:

In other words, who is the protagonist and who is the villain is entirely based on perspective. And, according to the laws of nature, we all must survive by eating others, or causing others to starve (i.e. avoiding being eaten).

I tried to think if this is really true in all areas of life. I’m a teacher, and one of the ways I convince myself that I am doing good in the world is by helping my students—preparing them well for college so that they can get into good schools and follow their dreams. But then, is this just taking fortune from others? If I do prepare my students well, and as a result they all get into top universities, does that mean they are taking spots away from other students? Am I simply just helping “my own,” at the expense of others?

One place where I see this concept play out very clearly is with our modern, industrialized society. As I mentioned in my last post, we live in a world of abundance. Most of us have enough food to eat, live in houses with electricity and running water, and don’t worry about a whole host of diseases endured by our ancestors. It seems we have done what Xie Lian couldn’t—we have expanded the well of fortune for most of humanity.

But this fortune wasn’t spontaneously created. It was taken from other species. It was borrowed against our own future, when climate change will likely destroy this world of abundance we have created, causing untold suffering. In truth, when it comes to prosperity, there is no such thing as a free lunch.

Even now, when we ought to be enjoying our fortune, most of us are not happy. We want other things. We take food, clothing, and shelter for granted, creating even bigger, more lofty demands—a bigger car, a better house, a machine that’s sole purpose is to make bread. In fact, it seems like whenever we make things “better,” the goalposts just move. I recently read a book called Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals, which mentioned that with the advent of washing machines and vacuum cleaners, everyone assumed there would be more free time. Yet, the real outcome was that standards of cleanliness just changed. Suddenly, people expected you to wear fresh clothes every day and have a perfectly dust-free home, which meant spending just as much time cleaning as in the past.

And according to psychologists, getting what we want doesn’t really make us happier. Instead, something like getting a promotion causes our happiness to spike, before it quickly returns to baseline. The psychologist Dan Gilbert writes that the purpose of our emotions is to act like a compass—to tell us which direction to go in. If you feel good, you can continue the way you are going. If you feel bad, you should probably turn—make a change. But if you get what you want and become permanently happy, your compass is now broken. It’s stuck in one direction and becomes useless.

All of this is very Buddhist, of course. Suffering is not caused by our external circumstances, but our desire to change them.

Like I said, I don’t necessarily believe in “fate” or “fortune.” But I believe this all points to something deeper that MXTX is getting at: which is that we cannot fundamentally make a better world, for the common people, or for anyone. This idea of “better” doesn’t really exist. The world is as it is. Trying to alter that is like playing God. And like Xie Lian says, “In this world, there are no true gods…”

So, what do we do? How can we survive this absurdist tragedy of life? I don’t think we can just throw up our hands and not give a shit—that way lies depression and Jun Wu-style cruelty. We cannot lose our heart. But we also can’t try to fix everything.

One thing I find a bit difficult about MXTX is she is very clear about the impossible situations our characters find themselves in, but not really clear about the solution. She seems critical of the characters’ actions (I’m thinking also of Wei Wuxian here), but what exactly does she think they should have done? In other words, what is the point?

I spent a long time thinking about this. And I realized that Xie Lian was able to get back on his feet, find happiness and make peace with himself. How did he do this? Ultimately, I see Xie Lian’s solution as having three parts: self-sacrifice, gratitude, and purpose. Which all sounds very academic and maybe not that profound on an emotional level. But hear me out. Because, in the end, I think these choices are incredibly beautiful. They are the kind of thing that make me feel like reading TGCF was actually a spiritual experience, no matter what MXTX says. That makes me admire Xie Lian and want to follow him (like the God he is).

Okay so first: self-sacrifice. If fortune is limited, and the only way to make others’ lives better is to take fortune from someplace else, then there is really only one place you can take it from without hurting others—yourself.

So, part of Xie Lian’s solution is to take fortune from himself and give it to others. It’s why he asks for a cursed shackle that disperses his fortune, so that his fortune will naturally flow to those around him. It’s, of course, a very small thing. He is no longer playing God, or trying to “fix” the world on a grand scale. He is simply, in his own, quiet way, serving the common people.

My desire to give up meat and to spend more time on activism—these things feel like big sacrifices for me. And yet, they will have a very small impact on the greater situation in the world. They’re a drop in the ocean. I still want to do it, but it’s hard. It’s hard to care, or think that these things matter. Yet, this is the trade-off Xie Lian was willing to make. I really admire him for it.

I believe self-sacrifice is actually a really important, beautiful thing, that our society has forgotten the value of. We are individualistic—obsessed with our own wants. As I mentioned previously, our expectations have risen, so we buy and buy and buy. We are unwilling to rein in our consumption. I know a lot of people baulk at lifestyle changes as a solution to the climate crisis, and I agree that putting pressure on individuals instead of governments or corporations is misguided. But, first of all, there simply aren’t enough resources on earth to sustain our current levels of consumption. And, second… I don’t think we can completely let individuals off the hook. What is society anyway, but a collection of individuals? If we are going to address this thing, it’s going to take a massive movement—bigger than the civil rights movement or the works’ rights movement or the women’s movement. It’s going to take millions of people worldwide getting out of their own heads, their own lives, and concerning themselves with the greater good. That requires immense sacrifice.

Which takes me to gratitude. In order to be willing to sacrifice, you have to appreciate what you already have.

People often talk about gratitude these days as a path to mental health. Instinctively, it sounds like an uplifting, positive thing. And it is… but it also entails having a relatively negative worldview. It means remembering all the horrible things that exist in this world which we are lucky enough to avoid on a daily basis. You stepped in some dog shit? Well, that sucks, but you could have stepped into an open manhole and broken your neck! So! That’s something to be grateful for.

We are all so lucky. I’m sure everyone reading this has pains and traumas and challenges. This isn’t to diminish those, but, I hope, at least we all have at least one person to love. That’s all Hua Cheng had, and it’s what kept him going. Just one person was enough. And most of us, I hope, get to eat food every day, get to sleep in a bed, get to play video games or read novels or write poetry when we are sad. Not everyone gets those things.

Xie Lian, of course, was the king of low expectations, because he knew his future was going to be bad. He had intentionally accepted bad luck for a lifetime. So, there was no point in hoping for things to get better.

I think this attitude is best shown by his interaction with the Venerable of Empty words. The Venerable of Empty Words feeds off people’s fears. But Xie Lian didn’t really have any. When the Venerable of Empty Words warned him that his hut will collapse in two months, his response is, “Two months? If it’s still standing in seven days, then it’ll be a real miracle.” Because his expectations are so low, he’s essentially immune to fear. I can’t help but think that if you could really think this way, it would be a kind of superpower. It reminds me of the famous quote by spiritual teacher Krishnamurti, “Do you know what my secret is? You see, I don’t mind what happens.”

And so Xie Lian is okay with everything. He can sleep anywhere, crash boulders on his chest for money, not eat for three days, regularly suffer corpse poisoning, and still be okay.

Which leads to my third point: purpose. Xie Lian is able to endure such hardship because his expectations are low, but also he knows all his suffering has a purpose. “If I am to become a God of misfortune, then so be it,” he says. “As long as I know deep down that I am not.” He is okay with being laughed at or avoided for his bad luck, because deep down he knows he is doing the right thing. People can withstand a great deal if they feel their suffering has meaning. In Man’s Search for Meaning, the psychiatrist Victor Frankl’s writes about the horrors of living through a concentration camp, and how over and over, it was creating purpose that allowed him, and others, to find motivation to survive. Which I think has an important lesson for self-sacrifice. People are willing to sacrifice a lot, if they feel their sacrifice has purpose.

I get it when MXTX says that she is not a guru, and maybe it’s a lot to ask of a danmei novel to take spiritual advice from it. The book wasn’t necessarily perfect, and I do have some critiques (which I was gonna add here, but this thing is already wayyy too long). But… I do think I found something really meaningful in this story—some inspiration. I want to follow Xie Lian’s example, and live with gratitude and acceptance, while keeping my faith in doing the right thing. In other words, WWXLD! (What Would Xie Lian Do?)

#tgcf#mxtx#heaven official's blessing#tgcf meta#tian guan ci fu#climate change#xie lian#hualian#danmei#chinese bl

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

I really love how in the breadth of range Xie Lian shows, never does he ever defer to power. One of the earliest (chronologically) scenes we see with this is when he was still just a beloved prince. For one, Xie Lian disregards everyone telling him that he should have let Hong Hong’er fall to his death to continue the parade, because letting a child die to preserve a festival tradition is morally bankrupt. Then later, Qi Rong is injured by Feng Xin—indirectly on Xie Lian’s orders—and despite the fact that Qi Rong was in the wrong (causing chaos, destruction, and injury in the capital streets, attempting to publicly murder a small child, acting above the law and against the direct royal family for his own whims), Qi Rong still demands that Feng Xin’s arm be broken, to which the king agrees because “a servant should never injure royalty.” Xie Lian, seeing the blatant corruption in this, tells his father that if he really thinks Feng Xin was wrong, then Xie Lian, most beloved prince of his kingdom, should be punished in his stead for giving him those orders. Xie Lian never backs down from this, using his status to attempt to cow his own father THE KING into admitting fault and backing down, and it was only because Feng Xin broke his own arm and kowtowed to end the dispute (“you shouldn’t fight with your father, Xie Lian”) that it was “resolved.”

After his ascension, we see him refuse to listen to the older, more “experienced” gods—including Jun Wu—who mock him for attempting to save his kingdom, telling him people are only good for the worship they provide while their actual lives mean nothing. When his kingdom is destroyed and he is at his lowest after being abandoned by his family and friends, he refuses to give in to Bai Wuxiang goading him into destroying Yong’an, despite the fact that none of the people stopped to help him as he lay for days with a sword through him (which by his own stipulations, meant they deserved death). When he ascends again and Jun Wu offers him his place back in the heavens, he rejects the offer, choosing to wander as a powerless, fortune-less immortal amongst the people over living comfortably as a powerful but removed god.

During his third ascension, he refuses to allow the other more popular and powerful gods to escape accountability for their actions, even as he is threatened for it. He goes after Pei Xiu despite everyone saying that it would get him on Pei Ming’s bad side, because he refuses to allow Banyue to take the blame for another’s actions, just because she is a ghost and he is a god. He refuses to stop associating with Hua Cheng despite everyone telling him to because, again, their hatred of the ghost king was based on bias and superiority complexes rather than the reality of who Hua Cheng was.

I could really go on and on, but you get the point: Xie Lian never bows to power or hierarchy to dictate his morality. He knows what’s right and wrong, and he’s gonna do the right thing, status quo and societal expectations be damned.

#tgcf#this was written way before my reread#think i was saving it for spoilers#no concerns about that anymore lol

235 notes

·

View notes

Text

reread volume 6 and god. fuck. xie lians arc is so so so important to me. because without all the magic and curses and stuff this is the story of a man going through a severe depressive episode. and i’ve been there. i’ve been there. in middle school i was so convinced people were all inherently selfish and cruel. we all deserved to be wiped out. and part of my recovery was rejecting that idea and realizing no, my friends text me when i can’t get out of bed. someone on my block writes nice messages in chalk all along the sidewalk. people are kind and people are good.

the first time i read “just one person. just one person was enough.” i started sobbing. one person is enough.

and it means so much that it was a stranger that gave him that kindness. with anyone who knows him, xie lians brain can find a way to reject it. pity, a sense of duty, whatever, when anyone close to him is kind to him xie lian believes he doesn’t truly deserve it. they’ll leave eventually.

but this man. this man didn’t know him. this man had no motivation. xie lian has done nothing to “earn” this small bit of kindness, because he doesn’t need to. being human being alive being a person means he inherently deserves to be treated with common decency. he deserves to be respected. he’s been in this spiral about how he and everyone else deserves to die for everything they’ve done, and he couldn’t live up to anyone expectations, but he doesn’t deserve to suffer for existing, and neither do the people of yong’an. he is a person who deserves respect and basic kindness, and so are the people of yong’an. fuck

#desperately waiting for my partner to reach it so i can ramble to them#tgcf#tian guan ci fu#heaven official's blessing#xie lian

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

TGCF and the Detachment from Outcomes

in Buddhism, detachment refers to the relinquishing of attachment to desires and the outcomes of actions. it is the understanding that attachment leads to suffering. (re: suffering, i have also written a meta about it in relation to the pursuit of dreams in TGCF.)

it seems paradoxical to say that given dreams are what we use to makes sense of our suffering and create meaning for our life, we should detach ourselves from it, especially since Xie Lian stubbornly persists in (which has the connotation of latching onto) his dream, and so does Hua Cheng, whose obsession maintains his existence after his death. but there is a nuanced distinction between deeply engaging with the process of chasing one’s dream and not caring about the outcome of it. i would like to argue that both Hua Cheng and Xie Lian don’t “care” about their dreams in this latter regard, and that the crown prince of Wuyong’s downfall lies with him caring too much.

starting with Hua Cheng, in being Xie Lian’s most devoted believer, he does not expect any reciprocation on Xie Lian’s part. even though Xie Lian is his dream, he does not care about whether he “achieves” his dream or not. he does not allow his sense of fulfillment to depend on the extrinsic nature of what his god could give him in return, though of course, he would be extra happy if Xie Lian did acknowledge him, the key is that he does not depend on it to motivate himself. instead, he is good to Xie Lian, respects his wishes such as praying without kneeling, develops himself to be strong enough so that he can protect his god.

moving on to Xie Lian, there are two lines from the novel that stood out to me:

1. from when xie lian was conversing with Ban Yue outside Puqi Shrine, 【This phrase [that his dream is to save the common people] was clearly his favorite before he turned seventeen. In the centuries that followed, he shouldn't have mentioned it at all!】

2. during the ultimate battle with Jun Wu, and actually throughout his history with Bai Wuxiang, 【He's probably right. Xie Lian cannot win. But even if he can't win, he must fight!】

it doesn’t matter if he can’t win, doesn’t matter if he can’t “achieve” his dream, the important thing is in trying itself, in which Xie Lian no longer talks the talk of “i want to save the common people!” but instead embodies it, taking action in saving people whenever he gets the opportunity. his dream ceases to be a distant outcome but a way of living.

in contrast, the crown prince of Wuyong was adamant about sacrificing people, albeit criminals, into the kiln in order to stop the volcano from erupting, because he was attached to the outcome of saving the common people as well as the image of a god who never fails. in order to achieve this outcome and sustain his image, he gradually deviated from his principles, saying that he wants to save people while killing them. (i will not personally assert that this is wrong, though, because this is just a utilitarian framework of ethics, and i believe that people are free to adhere to their own ethical frameworks without any standard being intrinsically more valuable than another, but i will say that under TGCF’s narrative, Jun Wu’s actions seem to be at odds with his ideals, which is what led to his dissonance and dichotomy.)

by the way, i don’t think this analysis would be possible under the old version of TGCF, because while i can sense that a deontological/Kantian argument is what the story hints at given the two lines i quoted above, Xie Lian at times expresses inconsistent standards. i do not wish to get into this, mainly because back then it gave me a headache. just know that in the revised version, 1. Xie Lian did not kill any soldiers in the Yong’an war and 2. Xie Lian did not kill Lang Qianqiu’s parents.

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

sharing some books I read recently and recommend for women in translation month!

for more: @world-literatures

Two Sisters by Ngarta Jinny Bent & Jukuna Mona Chuguna (Translated from Walmajarri by Eirlys Richards and Pat Lowe)

The only known books translated from this Indigenous Australian language, tells sisters Ngarta and Jakuna's experience living in traditional Walmajarri ways.

2. Human Acts by Han Kang

(Translated from South Korean by Deborah Smith)

Gwangju, South Korea, 1980. In the wake of a viciously suppressed student uprising, a boy searches for his friend's corpse, a consciousness searches for its abandoned body, and a brutalised country searches for a voice.

3. Things We Lost in the Fire by Mariana Enriquez

(Translated from Spanish by Megan McDowell)

Short story collection exploring the realities of modern Argentina. So well written - with stories that are as engrossing and captivating as they are macabre and horrifying.

4. Portrait of an Unknown Lady by Maria Gainza

(Translated from Spanish by Thomas Bunstead)

In the Buenos Aires art world, a master forger has achieved legendary status. Rumored to be a woman, she seems especially gifted at forging canvases by the painter Mariette Lydis, a portraitist of Argentine high society. On the trail of this mysterious forger is our narrator, an art critic and auction house employee through whose hands counterfeit works have passed.

5. My Brilliant Friend by Elena Ferrente (Translated from Italian by Ann Goldstein)

My Brilliant Friend is a rich, intense and generous-hearted story about two friends, Elena and Lila. Through the lives of these two women, Ferrante tells the story of a neighbourhood, a city and a country as it is transformed in ways that, in turn, also transform the relationship between her two protagonists.

6. Childhood by Tove Ditlevsen

(Translated from Danish by Tiina Nunnally and Michael Favala Goldman)

Tove knows she is a misfit, whose childhood is made for a completely different girl. In her working-class neighbourhood in Copenhagen, she is enthralled by her wild, red-headed friend Ruth, who initiates her into adult secrets. But Tove cannot reveal her true self to her or to anyone else.

7. La Bastarda by Trifonia Melibea Obono

(Translated from Spanish by Lawrence Schimel)

The first novel by an Equatorial Guinean woman to be translated into English, La Bastarda is the story of the orphaned teen Okomo, who lives under the watchful eye of her grandmother and dreams of finding her father. Forbidden from seeking him out, she enlists the help of other village outcasts: her gay uncle and a gang of “mysterious” girls reveling in their so-called indecency. Drawn into their illicit trysts, Okomo finds herself falling in love with their leader and rebelling against the rigid norms of Fang culture.

8. Strange Beasts of China by Yan Ge (Translated from Chinese by Jeremy Tiang)

In the fictional Chinese city of Yong’an, an amateur cryptozoologist is commissioned to uncover the stories of its fabled beasts. Aided by her elusive former professor and his enigmatic assistant, our narrator sets off to document each beast, and is slowly drawn deeper into a mystery that threatens her very sense of self.

#women in translation#translated fiction#booklr#book recommendation#books#mine#i sort of forgot it was this month which feels bad but#I mean I read translated women all the time but still I wanted to do smething

56 notes

·

View notes