#propraetor

Text

فيلم سكس عربي مصري جديد مسرب

Busty gf Rachel Starr fucking

First Time Sexy Phillipina with a Perfect Body only wanting to suck and deepthroat a Big White Cock

Gay stories straight boys and fucking hard fast I asked the guys to

Jillian Janson Loves To Fuck Karla Kush

Haley Reed and Marie Mccray sluts share dick on camera

Gang bang teen anal brutal and carter cruise slave Adrian Maya is a

Captivating sweetheart gives an awesome pov blowjob and tit fuck

Innocent babe Kara Lee slammed by bad guys monster cock

Peta Jensen Cumshot on Belly

#Webster#furied#Faunia#howlet#excruciate#nonsimular#Meo#embroidery#Barack#uncoifed#hysterogenic#Kissiah#Slavonically#monoplanist#gray-grown#demicadence#propraetor#German-jewish#varnsingite#ragazze

0 notes

Text

You can always tell when somebody isn't giving their Roman senator proper enrichment. They're a working breed, people. Give him a decemvirate committee or aqueduct to build or else he'll start bringing in packs of gladiators for attention.

And you need to resist the urge to adopt a whole litter. Sure, it's cute to watch all the quaestors skitter off to their provinces, but if they're the same age they'll fight when the consulships come up, and that's how you get mob violence and rigged elections.

Do you have enough territory for all of them to become propraetors and proconsuls? Do you have a wall of client states to prevent Parthians and Marcomanni from invading? Don't get me started on people who let their senators roam the provinces unsupervised. Your dear Lucius Tiddlypuss might not bring extorted art and gold into your house, but rest assured, he is decimating the local tax base.

I know it's hard, but you need to discipline your senator. Limit the length and scope of his provincial commands so the legions remain loyal to the Senate instead of him. Establish independent courts with clear accountability so his personal feuds won't escalate into civil wars. With a bit of research and attention, your Roman senator can have a long and forgettable career!

I mean, apart from the sex scandals. Yeah. They kind of just do that.

136 notes

·

View notes

Text

she res on my gestae until i in my nineteenth year, on my own initiative and at my own expense, i raised an army with which i set free the state, which was oppressed by the domination of a faction. for that reason, the senate enrolled me in its order by laudatory resolutions, when gaius pansa and aulus hirtius were consuls, assigning me the place of a consul in the giving of opinions, and gave me the imperium. with me as propraetor, it ordered me, together with the consuls, to take care lest any detriment befall the state. but the people made me consul in the same year, when the consuls each perished in battle, and they made me a triumvir for the settling of the state

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

i let him hit because at the age of nineteen, on his own responsibility and at his own expense he raised an army, with which he successfully championed the liberty of the republic when it was oppressed by the tyranny of a faction. in that account the senate passed decrees in his honour enrolling him in its order in the consulship of gaius pansa and aulus hirtius, assigning him the right to give his opinion among the consulars and giving him imperium. it ordered him as a propraetor to provide in concert with the consuls that the republic should come to no harm. in the same year, when both consuls had fallen in battle, the people appointed him consul and triumvir for the organization of the republic. he drove into exile the murderers of his father, avenging their crime through tribunals established by law; and afterwards, when they made war on the republic, he twice defeated them in battle. he undertook many civil and foreign wars by land and sea throughout the world,

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

So, regarding the debate on the date of issue of this Pompey aureus, I've collected the arguments for the different proposed dates (aka the dates of Pompey's triumphs) because well, it's interesting!

Usually, the arguments are based on 3 clues:

the head of Africa

the inscriptions "Magnus" and "proconsul"

Gnaeus being represented

DATE OF ISSUE: 81-79 BC (first triumph)

Supported by: Mommsen

The head of Africa relates to, well, Pompey's victories in Africa

Pompey had already been acclaimed "Magnus" by his soldiers and possibly liked it very much :)

[ This goes against Plutarch's statement that Pompey only started using "Magnus" in the Sertorian war ]

Although Pompey was granted the title "proconsul" only three years later, "propraetor" and "proconsul" are basically the same titles with only a difference in prestige

[ These arguments are summarized in Coins of the Roman Republic in the British Museum book (1910) where Grueber disagrees with Mommsen's theory on the basis that it "would have been an act of supreme arrogance" for Pompey to call himself a proconsul ]

DATE OF ISSUE: 71 BC (second triumph)

Supported by: Cavedoni (1831?), Crawford (1974), and the British Museum

cf Crawford's arguments in the original post

[ The BMCRR book finds it unlikely on the basis that Pompey shared this triumph with Metellus Pius and that Metellus doesn't seem to have issued his own coins ]

DATE OF ISSUE: 61 BC (third triumph)

Supported by: Eckhel (1798), Lenormant (1975), the CRRBM book (1910), Sydenham?

Lenormant's argument: Pompey was only proconsul in the war against the pirates and Mithridates + Gnaeus's presence hints towards the wars in Asia (which he apparently participated in (??))

Gnaeus being born in 80-76 BC and the first campaign in which he took part having been against the pirates in 67 BC, he could not have appeared on a coin issued in 81 BC and the BMCRR finds it unlikely for him to appear on one issued in 71 BC

The head of Africa is a callback to the title "Magnus", not so much to the campaign itself

(Additionally the book argues that the coin must have been struck in the East because its quality resembles that of Sulla's coins in the East)

Crawford arguing for 71 BC means Gnaeus would have been 5-9 yo for this triumph. For comparison, Marius's son appears as rider on a denarius issued for his father's triumph, and he would have been 8 at the time. Additionally, I may be wrong but I don't believe children had to have participated to their father's campaign for them to appear in the triumph?

Haven't found how to access the other references listed by the Brit Museum besides the BMCRR book (which provides a very long argumentation) and Crawford, but I'll edit the post if I find anything new for these three dates.

Now, I've kept it for the end because it's a little out of pocket but also kinda fascinating, but this article from 1963 by Harold Mattingly argues that the aureus wasn't issued for any of the three triumphs. His arguments are the following:

The strange choice of Africa for 61 BC

The absence of signature from the moneyer

The "proconsul" inscription

Instead, he suggests that the coin may have been issued during the civil war, paralleling the ones issued by Caesar and spiting him with the "proconsul" inscription (aka a magistracy that had been approved by the Senate). The head of Africa would relate to the African campaign of Cato and Scipio, meaning the coin would have been issued on their order after Pompey had already been killed. I don't know how likely this hypothesis is but I do like how it ties with some analysis I've read of the decisions made by Scipio (and to a much lesser extent Cato) like sending Gnaeus to Spain rather than other commanders so he could benefit from the Pompeius name.

#the romanity#pompey magnus#gnaeus pompeius jr#and uh#coins#well that's a niche post if i've ever made one#long post#?#my posts

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

propraetor anatoly takes florence to his province ohohoho it’s all coming together

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nitimur in Vetitum

chapter five: chalybe (steel)

The Battle of Mutina took place on 21st April 43 BCE between the forces loyal to the Senate under Consuls Gaius Vibius Pansa and Aulus Hirtius, supported by the forces of Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus, and the forces of Marcus Antonius which were besieging the troops of Decimus Brutus. -The Battle of Mutina

7th Day Before the Ides of Ianuarius (7th January, 43 BCE)

GAIVS IVLIVS CAESAR. Pisae, Italia

Gaius was bored. It had been days since anything has happened in Pisae. A week ago Gaius had received a letter from his beloved sister that contained a single phrase and informed him of the war beginning but nothing had really changed in the material. Agrippa and Gaius had travelled to the coastal town of Pisae and gathered more men from the area but with no news from the north there wasn't really much the two friends could do.

"Lord?" the voice of one of his personal guards, Vinnius, came from outside the door.

"Yes?"

"A messenger, Lord, from the Senate." Vinnius bowed and stepped aside, allowing another man to enter the room.

The man was older than Gaius but still seemed young for a magistrate, he was wearing the white tunic and toga that denoted his status. The man paused a few steps into the room and Gaius stepped forward to meet him. "Gaius Julius Caesar, it is a pleasure to make your acquaintance, I am Manius Tarquitius, I have a letter from Consul Pansa and Consul Hirtius."

"Greetings, it is a pleasure to make your acquaintance as well," Gaius said with a fake smile that he hoped looked real. Manius handed him a scroll, still sealed with a red wax seal of the consul. The sound of footsteps made Gaius pause in his movements. Vinnius, who had stepped back into the doorway to guard, placed his hand on his sword but relaxed when Agrippa came into view. Agrippa nodded to Vinnius as he passed him and walked around Manius to reach Gaius' side. "Agrippa, this is Manius Tarquitius, a messenger from the consuls," Gaius nodded to the older man. Agrippa smiled at Manius and mumbled a greeting but only moved to step closer to Gaius. Manius greeted Agrippa back but looked slightly put out by the offhand greeting.

Gaius simply ignored the other man and with another look at Agrippa, cracked the seal and opened the letter. There was a small letter and a smaller piece of parchment wrapped up in the scroll.

'By the order of Consul Gaius Vibius Pansa and Consul Aulus Hirtius, Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus, son of Gaius Julius Caesar, is hereby named propraetor and given all benefits that title allows.

Senatus Populusque Romanus'

Gaius blinked, oh... he hadn't expected that. To be named propraetor meant that the small army he had built here in Pisae was now legal and not an illicit bodyguard. Agrippa let out a soft chuckle beside him and Gaius looked up at him to share a smirk before schooling his expression and turning back to the letter in his hand.

'Dear Caesar Octavianus,

We have not met but I was informed by Marcus Tulius Cicero that you are in support of Senatorial action against the former consul Marcus Antonius. As such, Consul Pansa and I have decided to, with the senate's approval, declare you a propraetor and request that you march to the Via Cassia and wait for the arrival of myself and my troops for a march on Mutina to relieve the siege of Decimus Brutus.

I will be intrigued to meet the son of my good friend Gaius Julius Caesar,

Consul Aulus Hirtius of Rome.'

Gaius smiled, the time of boredom was over and the war was beginning. "Agrippa, Vinnius, gather the men and prepare to move west." Agrippa nodded, bowed slightly and he and Vinnius left the room to gather their soldiers. Gaius turned to Manius, "you know what these letters say?"

"I do," Manius nodded.

"And they sent you because?"

"I am to serve as your camp assistant until the consul arrives," Manius bowed and Gaius smiled.

"Well, let us prepare to march, Manius, we have a war to win."

--

On the Day Before the Kalends of Maius (30th April)

LVCRETIA IVLIA CAESARIS. Rome, Italia

Three months since the consuls had left for war and only scattered letters from her brother and lover. Lucretia was bored, her husband was complaining about the war against Antonius and Lucretia was without the men who made her feel wanted and gave her the pleasure she craved.

Luckily today had changed her boredom, a letter had arrived from Gaius with good news, Antonius had been defeated in Mutina. Even better news had accompanied it at the end of the letter, both Hirtius and Pansa had died leaving a space for the consul and Gaius had an army. He and Agrippa would head south now to the city. Though it had not been stated in the letter the subtext was obvious, Gaius would be consul, or his army would take the city and make him consul.

"What does it say?" Silvius' annoying voice cut through her thoughts.

"Hmm? oh, Antonius has been defeated and fled. Hirtius and Pansa are dead and Gaius is coming home," Lucretia said off-handedly. Silvius blinked as he thought over what she had said.

"Antonius lost?" He asked softly.

"Yes, quite handily according to Gaius."

"Wait... Hirtius and Pansa are dead?" Silvius raised a hand and ran it through his hair.

"Mhm, Gaius is now the highest ranking man in the north... he marches south with his army." Lucretia stood and walked towards her husband, "look happy husband, my brother is coming home." She kissed his cheek and left the room with a smile on her face.

--

The streets were peaceful, the news of Antonius' defeat and Gaius' march had not yet reached the plebeians and probably wouldn't until the army arrived at their gates. The senate would scramble to find a way to appease Gaius without making him consul. It wouldn't work of course, he would be consul and Lucretia would see the vengeance she desired brought upon her father's killers.

"Lucretia Caesaris! It is lovely to see you again," Livia Drusilla's voice made Lucretia turn her head to see the girl coming out of a side street.

"Livia Drusilla, a pleasure to see you," Lucretia stepped forward and kissed the younger woman's cheeks, "I hear that your father announced your betrothal to Tiberius Claudius Nero recently, congratulations."

Livia grimiced slightly but smiled, "yes, we are to marry in three months in September, I am quite sure you and your husband will be invited of course."

"Of course," Lucretia paused, "marriage was rarely a happy topic of discussion for roman women so she decided to change the topic, "what brings you to the streets this day Livia?"

"Simply looking for some new jewellery, you?"

"Just a short walk, my brother recently sent a letter informing me of his return and I was considering buying him a gift."

"Oh, Gaius Julius is coming back to Rome," she stopped for a moment, "I assume that means that he won the battle with Marcus Antonius."

"That he did," Lucretia smiled proudly, "he tells me that it was an easy and good victory."

"That is good, Marcus Antonius was a traitor and Gaius Julius was right to join the fight against him... to betray your father's memory by trying to remove the man that he appointed as governor is horrid," Livia said, her voice getting slightly softer near the end.

"Yes, he was never the most... loyal or smart man."

Livia giggled slightly, "you agree with my father on that point, he never liked Antonius and never understood why Caesar did."

"Hah, your father must be a smart man himself then," Lucretia narrowed her eyes, "especially if he thinks that it is proper to talk about politics around his daughter."

Livia blushed, "oh he... doesn't often... he's not improper, he-"

"-I was not attacking him for educating you Livia, it is wise, I think, to teach daughters the basics of politics at least, after all, we raise the next generation of politicians don't we?" Lucretia smirked at the end and Livia responded with her own.

She opened her mouth to continue but a short slave girl with darker skin stepped up beside Livia, "I apologise for interrupting domina but, your father wanted you home early and the sun-"

"-yes, of course Antigone. Apologies Lucretia but I must go," Livia smiled apologetically.

"Go home Livia Drusilla, it was a pleasure to speak with you again," Lucretia waved goodbye to the younger woman and she turned and left. ' hmm, an interesting girl.'

NiV masterlist / full masterlist

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Hellfrost and Fire | Fire, Frost and Hell | 18th March, 2022

International Death Metal

Artwork by Propraetor

https://hellfrostandfire.bandcamp.com/album/fire-frost-and-hell-death-metal

#Hellfrost and Fire#Fire Frost and Hell#International Death Metal#Death Metal#Old School Death Metal#OSDM#music#band#art#artwork#artist#Propraetor#TOR#Transcending Obscurity Records

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Patreon | Ko-fi

#studyblr#notes#history#historyblr#world history#roman history#rome#roman empire#gaius octavius#propraetor#praetor#quaestor

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

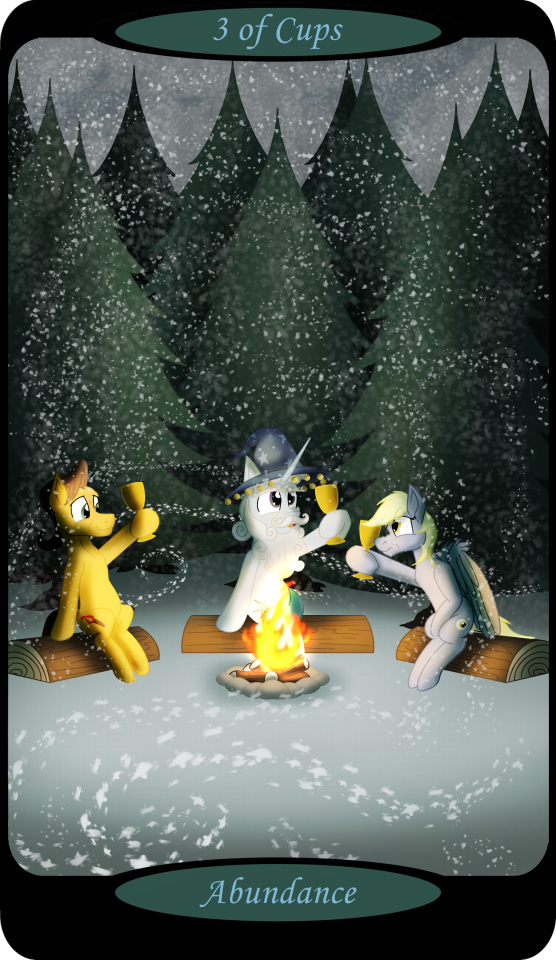

Updated pony tarot 13/26

Ace of Cups

Compassion

UPRIGHT: Love, new relationships, compassion, creativity.

REVERSED: Self-love, intuition, repressed emotions.

The Ace of Cups is a card of intuition and love, of awakening your spirit to the beauty and love that can be found in the world around you.

Two of Cups

Love

UPRIGHT: Unified love, partnership, mutual attraction

REVERSED: Self-love, break-ups, disharmony, distrust.

Ah, young love — her barely out of graduate school, him only on his eighth incarnation. When the name of the card is 'Love', what am I supposed to do if not put my OTP in? Anyway, here they are, Ditzy and the Doctor, stargazing together on a crisp winter evening, keeping one another warm as the lights of the city twinkle below.

Three of Cups

Abundance

UPRIGHT: Celebration, friendship, creativity, collaborations.

REVERSED: Independence, alone time, hardcore partying, ‘three’s a crowd’.

I like to think that not every pre-unification pony was as xenophobic as their leaders were. In the midst of the windigos, there were sparks of heat and light. Here, Star Swirl the Bearded meets with high-ups in the pegasus and earth pony camps to plan how to avoid needless conflict and bloodshed.

#My Little Pony#tarot#Tree Hugger#Ditzy Doo#Eighth Doctor#Doctor Whooves#Starswirl the Bearded#Torch Wood#Propraetor Cyclone#OCs#Pony Tarot

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

the last sentence in question (cicero’s philippics 14.36-38), clocking in at 328 words in the latin, roughly translated by me:

But, so that before too late I should sum up my thoughts, I say thus: as C. Pansa, consul & imperator, made a beginning of fighting with the enemies in the battle in which the legion of Mars defended the liberty of the Roman people with admirable and incredible virtue, which the legions of recruits did the same; and as C. Pansa himself, consul & imperator, when he was moving among the weapons of the enemies, received wounds, and as A. Hirtius, consul & imperator, when he heard the battle [and] understood the situation, led his army with the bravest and most excellent spirit out of the camp and made an attack on M. Antony and his army and cut down his troops in a slaughter, with his army thus unharmed that he did not lose even one soldier, and when C. Caesar, propraetor & imperator, with resolve and diligence auspiciously defended his camp and overthrew [and] cut down the enemy troops which had approached the camp: for these reasons the senate considers and concludes that by the virtue, power, resolve, dignity, perseverance, greatness of spirit, [and] good fortune of these three their imperators, the Roman people were freed from the vilest and meanest enslavement, and that as they have saved the republic, the city, the temples of the immortal gods, [and] both the good fortunes and the children of everyone, with struggle and danger to their own lives, thus on account of these things done well, bravely, and auspiciously, may C. Pansa [and] A. Hirtius, consuls & imperators, one or both, or if they should be absent, M. Cornutus, urban praetor, set up supplications at all the couches for fifty days: and as the virtue of the legions has shown itself as worthy to the most illustrious generals, the senate will pay that which they previously promised to the legions and the armies, with great eagerness, now that the republic is restored, and as the legion of Mars clashed with the enemies first, and contended thus with a greater number of enemies that they slaughtered many and some few fell, and as without any retreat they poured out their lives for their country; and as soldiers of the remaining legions encountered death with similar virtue for the safety and liberty of the Roman people, may it please the senate that C. Pansa [and] A. Hirtius, consuls & imperators, one or both, if it seems good to them, arrange for the greatest monument possible to be contracted and built for those who poured out their blood for the life, liberty, and fortunes of the Roman people, for the city [and] the temples of the immortal gods: and may they order the urban quaestors to give, grant, and unbind money for this matter, so that it may testify for the everlasting memory of our descendants to the wickedness of those most cruel enemies and the divine virtue of our soldiers, and so that those rewards, which the senate previously set up for the soldiers, may be paid out to the parents, children, wives, [and] brothers of those who fell in this battle for their country: and let it be paid to them what ought to have been paid to the soldiers themselves, if they who won by death should have won living.

#i am sorry for this post.#CICERO YOU FORGOT TO END THE SENTENCE. CICERO PLEASE YOU CANT KEEP DOING THIS#i still dont understand whats going on with 37 with the senatum existimare et iudicare#like grammatically i cannot account for that but i think i understand what he means? i hope?#ribbits

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

“…It is at this point that we find the first reference in the sources to Livia’s father, Marcus. He was evidently an energetic opportunist, for he hitched his wagon to the triumvirate and was sent—or at least had reasonable expectations of being sent—on a mission to Alexandria in 59 bc to raise funds. Marcus had perhaps just shortly before married Alfidia, and on January 30 of either 59 or 58 he became a father, with the birth of his daughter, Livia.

The month and day of Livia’s birth are established by inscriptions of the post-Julian period as a.d.III Kal. Febr., the third day before the first of February, reckoned inclusively. This date is by convention given as January 30 in the modern calendar system, although there is in reality no truly satisfactory way of expressing it, because in the pre-Julian calendar January had only twenty-nine days. The year is more problematic. The place of birth is even more obscure; we have no direct hint of where it might have been. The absence of any boast in extant inscriptions from a town proudly claiming distinction as her birthplace, and the lack of speculation in the literary sources, suggest that she might have been born in Rome.

Livia’s father is next heard of in 54, when he was prosecuted for improper legal practices (depraevaricatione) but acquitted through the efforts of Cicero— the kind of case, as Tacitus notes, that does not later arouse much interest. In any event, the publicity does not seem to have impeded his career. By 50 he was praetor, or iudex quaestionis (president of a court), presiding over a case being tried under the Scantinian law, which covered prohibited sexual activity.

Although there are grounds for suspecting that he might have been wealthy, through his adoptive father or his wife, he seems to have fallen into some financial difficulties at about this time, and we later find him trying to sell his gardens to Cicero. Marcus was a hard bargainer, but he met his match in the famous orator, who was determined to come out best in the deal. …on the Ides of March, 44 bc, Caesar was assassinated. It was probably not long after this pivotal moment in Roman history that a pivotal event took place in Livia’s life also, her first marriage. Indeed, because nothing at all is known of Livia’s early life apart from her birth, this is the first incident that the historian can infer.

Her husband, Tiberius Claudius Nero, belonged to the less distinguished branch of the patrician Claudians. As we have seen, the last consulship the family could claim was in 202 bc. Very little has been passed down about Tiberius Nero’s immediate forebears, although we know from a very fragmentary inscription that his father was also a Tiberius. The older Tiberius Nero served in 67 bc as legate of Pompey against the pirates, with command at the Straits of Gibraltar, and in 63 made a speech against the summary execution without trial of the associates of Catiline, who had been exposed by Cicero in a major conspiracy. Their family names leave little doubt that Livia and her husband must have been related.

How closely is far from clear, although some scholars assert with confidence that they were cousins. Tiberius Nero might have seemed a good marriage prospect. Cicero speaks of him having the qualities of an adulescentis nobilis, ingeniosi, abstinentis (a young man of noble family, of native talent, and moderation) and remarks that there was no one among the noble families he regarded more highly. (Of course, these warm testimonials appear in a letter of recommendation, a common repository of inflated praise.) Tiberius Nero makes his own entry into history in 54 bc.

In that year a Pompeian supporter, Aulus Gabinius, returned from Syria after a governorship that seems to have been marked by administrative incompetence and large-scale bribery, a common enough situation in many of the provinces of the late republic. Gabinius became the celebrity of the year, denounced by Cicero and hounded in a series of showy trials. Before his trial for extortion (de repetundis) there was a scramble for the high-profile role of prosecutor, and Tiberius Nero competed against Gaius Memmius and Mark Antony. The contest was keen and Cicero comments on Tiberius Nero’s fine effort and the quality of his supporters. But Cicero anticipated that Memmius would win out, and was proved right. The outcome marked Tiberius Nero down in this first highly public incident as a worthy failure, a characterization that could probably be applied to his whole career.

In late 51 or early 50 he visited Asia, where he had a number of clients, and he called on Cicero during the latter’s governorship of Cilicia. At this time the tortuous negotiations for the third marriage of Cicero’s daughter Tullia were under way. Tiberius Nero seems to have made a strong impression on his host, to judge from the warm letter of recommendation that Cicero wrote for him to Gaius Silius, propraetor of Bithynia and Pontus.

The young man declared an interest in Tullia and obtained her father’s consent for the match. Messengers were despatched to Rome to give mother and daughter the happy news. Unfortunately, Tiberius’ hostile daemon intervened—it seems that before he left, Cicero had told Tullia and her mother to arrange the negotiations in Rome themselves, and because he was going to be away for so long in his province, not to feel obliged to refer the issue to him. The messengers arrived in Rome just in time to miss Tullia’s engagement party.

Tiberius Nero would probably have been a better choice than his successful rival, the seedy Dolabella, a ruthless adherent of Caesar’s and a man whose career was enlivened by dissipation and debts. Cicero had approved of Tiberius Nero as a potential prosecutor in the Gabinius case because of his stand against the power block represented by Caesar and Pompey (and Crassus). By 48 bc he was doubtless dismayed when his young champion displayed the often crass opportunism typical of the period. Putting his support behind Julius Caesar, Tiberius Nero signed up as his quaestor and commanded the fleet at Alexandria. As a reward for his services he received a senior priesthood and in 46 was given responsibility for founding colonies at Caesar’s behest in Narbonese Gaul, including Narbo and Arelate.

He might have seemed to the outside world to be on an upward trajectory, but cruel fate intervened. The Ides of March in 44 and the assassination of Caesar changed the destiny of many besides Caesar himself. Tiberius Nero had to make a career choice, and characteristically made the wrong one. Perhaps under the influence of Livia’s father, he followed the course of many Caesarian supporters and jumped sides, hitching his wagon to the assassins’ team, even proposing special honours for the killers.

We do not know for certain when Tiberius Nero and Livia were married. The normal age of marriage for women at this period seems generally to have been in the late teens, but in upper-class families marriage at fifteen was probably the norm, and even earlier marriages were common in aristocratic circles, when there was a political advantage to the match. By this reckoning Livia, depending on her date of birth, might have reached a marriageable age in 46 or 45. But this earlier date may not have been possible if Tiberius Nero was serving in Gaul at that time. The birth of their first son in November 42 gives us a limit, and places the marriage probably in 43, when Livia was fifteen or sixteen. Her husband would likely have been in his late thirties. The marriage took place during the dramatic aftermath of Caesar’s assassination.

Two men competed to fill the vacuum left by his death. One was Caesar’s lieutenant Mark Antony. The other was his great-nephew, Octavian, named his heir and adopted son in his will, the man destined to transform the character of the Roman state and to become Livia’s second husband. He was born Gaius Octavius, on September 23, 63 bc, in Rome. Although malicious gossip claimed that his great-grandfather was a freedman and rope maker, the family, though not distinguished, was well-to-do. The Octavii originated from the Volscian town of Velitrae, two days’ journey south of Rome. His father, also Gaius Octavius, was a prosperous banker, a member of the entrepreneurial middle class that largely constituted what is known as the equestrian order.

…Octavius had been in Apollonia for a few months only when a messenger arrived from his mother with the dramatic news that Caesar had been murdered. He decided to return to Italy at once with a few friends, including Marcus Agrippa. In Brundisium he learned from letters sent by his mother and stepfather that he had inherited most of Caesar’s estate and, more significantly, had been adopted as his son. His family advised him to decline the adoption, perceptively anticipating the political firestorm that it would create. He did not follow their advice and proceeded to Rome. He now began to style himself Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus, following the Roman custom of assuming the name of the adoptive parent with a form of the original gens appended.

The adoption fuelled Octavian’s ambitions, and its importance to him is demonstrated by his desperate efforts to have it confirmed. The adoption of relatives or even of nonrelatives was a well-established tradition in Rome, and adopted sons and daughters naturally styled themselves henceforth as children of the adoptive, not the natural father. But testamentary adoption, which later played a significant part in Livia’s own career, seems to have been in a dubious category of its own. The ancient evidence is not explicit, and the ancient jurists are silent on the matter, but it seems that adoption stipulated in a will was almost certainly not an adoption in the full sense of the word, but mainly a device to allow for the inheritance of property on condition that the adopted child assume the name of the legator.

This ambiguity explains why Octavian was determined at all costs to have the status of the adoption legally ratified. He attempted to do this soon after his arrival in Rome and took on as an ally in his campaign Antony, who pretended to be making every effort to have the appropriate law passed but was in fact doing everything he could to block it. When Octavian became consul, in May 43, one of his first measures was to have the proposed law presented to the popular assembly. The symbolic importance of the adoption cannot be stressed enough. In practice he ignored the final element of his name, Octavianus, and preferred to use only Gaius Julius Caesar. Although clearly an unfriendly source, Antony was not far off the mark when he said of him et te, o puer, qui omnia nomini debes (and you, lad, who owe everything to a name).

And more was to come. There is evidence that Caesar might have received divine honours even before his death. At all events, in 42 posthumous divine honours were granted him. Henceforth, Octavian could style himself not only as the son of Julius Caesar but as the son of Divus (the deified) Julius. The following years did in a sense vindicate his parents’ reservations, for conflict arose between Octavian and Antony in their zeal to assume Caesar’s mantle, a struggle that was punctuated by a series of pacts but was not resolved finally until the suicide of Antony in 30 bc following the decisive battle of Actium.

The struggle between powerful and ambitious Roman political and military leaders in the last century of the republic inevitably embroiled the rest of the population, especially Romans of prominence, who, as is usually the case in a civil war, found it impossible to stand on the sidelines of the conflict. It also brought tragedy into Livia’s life. Nothing explicit is known about her father Marcus’ stand during the clashes between Caesar and Pompey or during the ascendancy of Caesar. Shackleton-Bailey has tentatively suggested that Marcus was a Caesarian, but whatever loyalty he might have felt certainly did not survive the dictator’s death, when he emerges as a champion of the tyrannicides. In 43 we find him one of the sponsors of a senatorial decree to give command of two legions to the assassin Decimus Brutus.

By the end of that year he had been proscribed by the triumvirs. He fled east to join Brutus and Cassius and shared with them their final defeat at Philippi. He personally survived, but afterwards reputedly died a courageous death. Refusing to ask for mercy, he committed suicide in his tent. We do not know what happened to Marcus Livius’ property. Livia may have been his only natural child, but there are strong grounds for believing that in the absence of a natural son, Marcus before his death arranged in his will for the adoption of Marcus Livius Drusus Libo (consul in 15 bc). Libo’s natural father, Lucius Scribonius Libo, later demonstrated powerful political connections.

…In the meantime, the conduct of Livia’s husband, Tiberius Nero, highlighted the two dominant traits in his makeup: an inordinate opportunism and a penchant for guaranteeing that whatever opportunity he seized, it would be an injudicious choice. He did not follow Marcus in sticking to his principles to the bitter end. Once he recognised that the plight of the assassins was hopeless, he broke away from his father-in-law’s position. The struggle for supremacy now clearly lay between Octavian and Marc Antony, and Tiberius Nero opted to back Antony. He was elected to the praetorship in 42, but following a dispute that arose among the triumvirs, he refused at the end of his term to leave office and stayed in place beyond his legally defined period.

Early in the same year, Livia became pregnant. It is said that she was very keen to bear a boy and used a method of determining the sex common among young women of the time: she took an egg from under a brooding hen and kept it warm against her breast. Whenever she had to yield it up, she passed it to her nurse under the folds of their dresses so as not to interrupt the warmth. A cock with a fine crest was hatched, a portent of a vigorous son. Later in the year we have the first specific recorded evidence of her whereabouts. On November 16, 42, the first of her two sons, Tiberius, was born on the Palatine in Rome.

…After the successful campaign against Caesar’s assassins at Philippi, the triumvirs had agreed on areas of command. Marcus Lepidus was restricted to Africa. Antony took the East, where he launched a campaign against the Parthians. Octavian commanded in the West. His task was to restore order in Italy and keep a check on Sextus Pompeius, the younger son of Pompey, who had set himself up with a large fleet in Sicily and had established a haven for fugitives from the triumvirs. Octavian also undertook the grim task of confiscating territory in Italy for the retiring veterans. Antony’s brother Lucius Antonius, and Antony’s wife, Fulvia, became the champions of the dispossessed Italians and sought to instigate an uprising against Octavian; Tiberius Nero joined the effort, and Livia and her son followed him to Perusia, the main centre of opposition.

When Perusia fell in early 40, Tiberius Nero escaped with his family first to Praeneste and then to Naples, where he sought to instigate a slave uprising, helped by Gaius Velleius, the grandfather of the historian. That effort collapsed and the family had a hair-raising escape. As Octavian’s forces broke into the city, the family decided to make a break for it. Velleius, by now old and infirm, was too weary and ran himself through with his own sword. Tiberius Nero and his family set out to make their way stealthily to a ship, avoiding the regular routes and going off into the wilds of the countryside.

On the journey little Tiberius started to cry. There was panic that he might give them away. Livia snatched him from the nurse, and when he still did not settle down, one of her followers seized him from her and apparently saved the day. The ancient authors were quick to spot the irony of Livia fleeing the man she would eventually marry, with a son who would eventually succeed him.

The family did in the end make their escape and went to Sicily. They perhaps hoped that family connections, through Marcus Libo, the brother-in-law of Sextus Pompeius, would stand them in good stead. But if this connection did exist, it did the couple little good, and their reception in Sicily must have been a considerable disappointment. Sextus Pompeius found Tiberius Nero something of an embarrassment and was reluctant even to grant him an audience. Also, perhaps to avoid unnecessary provocation, he ordered Tiberius Nero not to display the fasces, the rods of the office of praetorship, which he had illegally retained in his possession.

Sextus’ sister, perhaps motivated by personal rather than political concerns, was more welcoming, and even gave the little Tiberius a cloak with a clasp and some gold studs. These survived as celebrity items and were exhibited for tourists in the resort town of Baiae until Suetonius’ day. But Tiberius Nero now fell foul of the complex and shifting tide of Roman politics. Octavian, faced with the prospect of a confrontation with Antony, sought to move closer to Sextus Pompeius. Tiberius Nero was obliged to pack his bags once again and go with his wife and infant son to join Antony in the East, where the Claudii Nerones seem to have acquired a large number of clients.

It might have been at this time that Tiberius Nero was proscribed. We certainly know that it happened at some point—Tacitus states so unequivocally, although without providing a date. We cannot be sure why Livia followed her husband into exile, unless for the uncomplicated reason of personal affection. It was certainly expected that wives would either accompany proscribed husbands or stay at home and work on their behalf. But they could not be compelled. By now it must have been apparent to Livia that her husband was not destined for greatness, and it perhaps says something for her strength of character that as a young mother of eighteen or so she seems to have put duty before personal convenience.

The couple were able to get safe passage by joining a distant kin of Livia’s, Lucius Scribonius Libo, who left Sicily to accompany Antony’s mother, Julia, to Athens and allowed Tiberius Nero and his family to sail with him. Antony was perhaps no more eager than Sextus to be lumbered with someone so tainted by failure, and he quickly despatched Tiberius Nero to Sparta, where the Claudii had long enjoyed patronage. Sparta, perhaps because of its ties to the Claudians, offered the couple an extremely cordial welcome, in contrast to their earlier experiences.

Livia was later able to acknowledge their support by rewarding the community for the loyalty it had shown her in times of trouble. But Tiberius Nero was unable to break the habit of a lifetime. Once again they had to flee—the reasons are not known. This time it was by night, through a forest where a fire broke out. The family barely escaped. The event would have been especially memorable to Livia, who ended up with burning hair and a charred dress. In ad 40 Antony and Octavian settled their differences at the Peace of Brundisium, and the compact was sealed by the marriage of Antony and Octavian’s sister, Octavia.

A further, even shorter-lived compact, the Treaty of Misenum, was reached by the triumvirs and Sextus Pompeius in mid-39 bc. It promised an amnesty to those who had sided with Sextus. Livia and her husband were thus able to return to Rome at the same time as Mark Antony. Livia’s mood is not recorded, but it must have been sombre enough. Her father was dead, and she must by now have recognised that her husband’s star had started to set even before it had properly risen.”

- Anthony A. Barrett, “Family Background.” in Livia: First Lady of Imperial Rome

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

SPQB

The more I think about it the more I see similarities between Bayern and the Roman Republic.

We have two consuls : Hainer and Kahn

A bunch of proconsuls and propraetors : Hoeness, Beckenbauer, Scherer, Rauch...

A senate with the supervisory board.

Two praetors with Andreas Jung and Hasan Salihamidzic.

All sort of magistrates with the different departments (scooting, medical unit, media, finance...).

And of course comitia with the general assembly.

1 note

·

View note

Note

🌻 >:)

marcus tullius cicero's actiones in verrem, commissioned by the sicilians against known thief gaius licinius verres for bribery, extortion and stealing of private and public works of art and valuables all over sicily during his time as propraetor, was composed of seven parts: the divinatio, the actio prima, after which verres fled the country in shame, and the actio secunda in five parts, which cicero published anyways just for spite. the first of these, and the one most often forgotten, is the divinatio in quintus caecilius, essentially a rap battle to decide who should be the one to go up against verres and his attorney hottest-bitch-in-the-forum hortalus in the trial: cicero easily won it, likely because quintus caecilius was either a sockpuppet for verres himself or just a really bad orator.

#cicero i hate you but i love you but i hate you but i love you ❤️#choosing to talk about this on caro's ask because they're as much a bisexual icon as cicero

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Roman civil commanders: Lucius Gellius Publicola (d. 31 BCE)

Roman politician and general who had rather colourful career. Among other things he was accused of committing incest with his stepmother and plotting to murder his father. After Caesar’s assassination he joined republican army, but things didn’t go too well there either. After short time Gellius was namely accused of trying to assassinate both Brutus and Cassius. Thanks to the pleas of powerful relatives his life was eventually spared. After this incidence Gellius switched sided and joined triumvirs’ forces. During the civil war he issued coins in Asia Minor using title Quaestor Propraetor. The coin above with images of Marcus Antonius and Octavianus is from this era (41 BCE). The pinnacle of Gellius’ political career came a few years later when he was a consul. In a war between Octavianus and Marcus Antonius he sided with the latter. At the battle of Actium Gellius commanded the right wing of Antonius’s fleet and was killed in action.

https://smb.museum-digital.de/index.php?t=objekt&oges=155283

Source: Münzkabinett, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin - Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz; Creator: Dirk Sonnenwald ; Copyright Notice;CC BY-NC-SA

#Roman civil war commanders#history#ancient#Roman#coin#Asia Minor#1st century BCE#Berlin antikensammlung

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wordtober Day 16: Wild

A horror lite short story about the Lusitanian people fucking HATING the Romans, enjoy. And yes, it’s THAT Sertorius, this takes place immediately before his war.

-----------------------

Caetobriga slept, and the guards kept watch.

On the pathway leading to the forest beyond the city, Quintus stood tediously, body sore from the uptight position and the tightly held lance on his hand, torches burning on the dark walls of the archway, and even his neck ached from the weight of his helmet. He took a deep breath and adjusted his position, though next to him, Caelius didn’t seem slightly bothered with his slouched shoulders and the yawn he didn’t even care to conceal with a hand.

Quintus wanted to slap him on the nape, but the reckless guard took notice of the stern look on his face and straightened himself up with swiftness.

Nights in Caetobriga were boring, though the days could be filled with screams and loud voices far too irritating for him, but Quintus had followed Sulla thus far, deep into the lands of Hispania, to fight a war only to end his career as a miserable guard. Two years fending off the nagging Sertorius in the name of Gaius Valerius Flavius to keep control of the savages in Iberia had rendered him one less finger on the left hand and a blow to the leg that had left him bedridden for seventeen days, but at least the region was back in order. The stubborn propraetor had retreated south, and last Quintus had heard, he had been ransacked by pirates.

Though, being honest to himself, Quintus knew he had never been too great a soldier. Decent, certainly, enough to suffer a cut or bruise, perhaps, but nothing life-threatening. He had never gone past the rank of princeps, which was in itself a miracle as it was. Experience enough to fight in the second line, though always on foot—he’d never rise up to the demands of the cavalry. He’d be a legionary his whole life—and one guarding a Lusitanian city, of all places.

Though the peoples had been tamed, properly guided into civilized society, as they needed to. Cattle herders, most of all were; Quintus had laughed merciless at the sight of two young boys marvelled at a simple stylus and wax board. Some old hag had mumbled tales of a former slave freed from Rome having brought the toy with him some ten years ago, but that, Quintus suspected, was just her manner of acting dismissive, considering how the peoples there could be lying, cheating weasels. Even as construction was underway for the new thermae, those poor sheep-herders had looked up at the stone in marvel, blinded in delight, as if Selene rode her very own silver chariot in the skies.

The city was growing, but it was mostly just fish salting workshops everywhere, which brought about an unbearable smell of fish and salt all year round, moon after moon—either from the workshops themselves or the river. It had been charming enough the first few days, something unique to the region—Quintus had even thought it to be a pretty sight, idyllic and clean—but now, it forced him to burn herbs inside his quarters for the sake of keeping that stench away from his nose.

At least, the peoples there had been subdued, paying their dues and herded into civility. Had it not been for the mighty intervention of the Empire, those madmen would still be squabbling through their forests like wolves or bears.

Yet however Quintus knew he sounded quite dismissive towards, there was a part of him that feared a confrontation with a proper Lusitanian army as they had faced at the time of the general who had embarrassed Rome. An average legionary like him, facing warmongering people whose women were said to sleep with gladiuses under their pillows and were quicker than the men to grab a spear and impale an enemy with less mercy than man—he’d be doomed.

After all, technically the Lusitanian had never been defeated. The only way the Romans managed to conquer them was through bribery and assassination, though a man like Quintus would never say those words if he valued his life.

Quintus blinked his eyes in boredom as the light of the torch next to him flickered in the darkness, an unexpected breeze passing by, and nearly fell asleep on his feet had he not noticed something strange about Caelius next to him. Rambunctious as he was, fond of drinking and visiting local brothels wherever he was, Quintus thought him as much a coward as he sometimes could be. Reason why, he believed, they had both been left there to guard the walls of an unprotected city that, in reality, had no threats outside its walls.

The Lusitanians were gone, subdued or tamed like chickens, anyway. Sometimes he even thought the walls were useless.

Caelius squinted his eyes and gave a step forward; this time, Quintus’ cold and stern look did not send him a warning, not even as he tipped his lance and gave him a hard tap on the greaves on his shins, a soft and metallic growl fluttering for a brief moment. Caelius waved a hand, shushed him quietly, and gave another step forward, gazing into the complex mesh of trees that rose in the distance, making way to the forests ahead.

“I think I saw someone there,” he murmured. “In the forest.”

Likely, Quintus thought, though what he couldn’t understand was why he should care about it. “And? Some wanderer, chances are. A beggar or a traveller who got lost, or—” maybe someone avoiding some form of taxation—he’d heard of those, though Quintus generally minded not the mathematics behind the logistics of the Empire. “I don’t know, just don’t mind it.”

“But it looked like a woman.” Caelius’ eyes glimmered under the torches in an urgency Quintus seldom saw. “She looked in trouble.”

He sighed, peered ahead and tried to see. The forest was still and silent, with nothing interesting to it, but Quintus put some effort into it nonetheless, if only to appear concerned enough that Caelius would leave the matter be.

“I see nothing,” he replied, bored. “It’s just a f—”

“There!” Caelius shouted, not minding the hour of the night, and his finger jutted forward.

Quintus followed his eyes and saw what he meant: a woman, indeed, dressed in a dingy white, or perhaps it was grey, tunic that flapped freely about her body, torn to shreds at the shoulders and ripped apart from the knee down. He could see she had black hairs, cascading over her face in a disarray of a dancing shadow, and her arms were fully exposed—he saw a hand lifted in despair and then tumble down as she collapsed on the ground.

Before he could say anything, Caelius took off, lance in hand, rushing through the humid soil to aid the woman. Huffing—certain, this time, he was going to be sent to the front lines of whatever next war for his mistake—Quintus followed him in the darkness.

The woman fell to the ground, arms splayed about as she wept silently, and up-close, Quintus could see the damage her dress had suffered. It seemed made of some rough material, like burlap, improper for garments, and it exposed her filthy, brown feet, cut and bruised from the run. She raised her teary eyes, big and blue, glowing like the moon above, and pulled her hairs away from her pink lips as she breathed deeply.

“Help me,” she murmured, nearly out of breath. Her trembling hand pointed back, and clearly in a state of urgency and unrest, she began to heave herself, ignoring the twigs and dirt on her body, half-dragging herself towards the forest. “My child,” she mumbled—there was something about the way she spoke, Quintus thought, as if she had recently learned how to speak. “My child. There’s a boar—”

“Oof,” Quintus sighed, ready to drag her back to the city and—perhaps, who knew—arrest her for… something. He’d figure something out. Either way, he knew there was no way a mediocre legionary like himself would dare to face a boar alone—babe or no babe involved.

But Caelius seemed to have caught on to his hesitation, and quickly enough, he furrowed his brow in what was clearly a deep sense of insult that Quintus was unsure if he felt it aimed at himself or the woman.

“You’re not walking away,” he said. “She needs help.”

“She needs a javelin.”

“For Juno, you’re worse than a drunken pig.” Somehow, the peculiar insult seemed to hurt Quintus’ feelings far more than he had expected. Caelius gathered himself, patted his knees and laid out a hand for the woman to take. “Come along,” he said. “Show me where you’ve seen this boar.”

Quintus thought it strange. Caelius had always been a rowdy one, a lover of grapes and bread as much as Bacchus, his silent guardian god from the cradle. He was far too carefree for the stern rigidness of a legionary’s life, and gotten far too many a reprimand from all and any centurion whose host he’d fought under. Quintus had seen him scrubbing floors and cleaning weapons as punishment so often he had, at one point, wondered if he hadn’t been secretly assigned both duties after all.

But he was not brave. If there was one thing Caelius was not was brave. He cowered before any hint of confrontation, invoking Mars and Juno to protect him against the brutes who saw in his slender face and sleazy self a perfect punching bag, and always ran away. At the slightest drunken brawl, one could hear the tapping sound of Caelius’ sandals as he ran down the streets, with his tail between his legs. Even in the war, he had served far below Quintus—a mere light infantry soldier, though sometimes he doubted he’d done any fighting at all. Perhaps he was just the cook, or the tanner.

Quintus had seen, however, his infatuation for any a woman who pranced before his eyes, and had easily understood a nice pair of waddling hips would be enough to entice him into a night of frolicking. Though he seemed to have a peculiar taste: he always preferred Lusitanian women; though Quintus thought it strange, for he deemed them unattractive—too brute, no delicacy to their touch, and far, far too loud.

Sighing loudly this time, Quintus watched as Caelius patted the woman behind the shoulder, gently sheltering her weeping voice in his arms, almost as if he cared for her. The dog was willing to get himself mauled by a boar of all things just for a pair of Lusitanian tits. He had to follow him, of course; if anything were to happen to him, Quintus would get the end of the stick still, so he had to follow him into the forest and pray for Diana’s guidance against a ravaging beast such as a boar.

The forest was calm and still, though everywhere he could hear the snapping of twigs and crunching of leaves beneath the soles of Caelius’ sandals, and from between the soft peeping of nightly birds, came the sobs and wails of the woman. Strangely, the air felt denser there, as if the particles of humidity shifted and rubbed against each other to bring about something… different. A different smell, to begin with—the nauseating scent of fish and salt began to waft away, and Quintus was left with the pure, deep breath of a simple forest: pine trees and wet earth. How he had missed it.

When he focused on the narrow path, smashed between brambles and junipers ahead of him, he realized he had lost sight of Caelius and the woman. Startled by the sense of solitude, as if the forlorn child before a boar now was him, Quintus raised his spear and readied himself for a confrontation he wasn’t even sure was bound to happen or not, but he was never too careful. He trod on, in cautious and soft steps, muffled by the warm earth beneath his sandals, casting glances around while searching for the presence of two people that should be there.

But he heard nothing, and he saw nothing.

The forest grew denser, and soon, the path had disappeared entirely. Now, he walked down a layer of crushed leaves and broken twigs, pushing away thorny bushed that tugged at his tunic with every step, forgetting about the boar entirely and using his lance as a mere stick. The air seemed different there, and it was somehow more difficult to breathe—or perhaps he was just tired and out of shape.

Then, a fog appeared, though from where, he could not tell. A simple mantle of white and grey wafted in the air, slowly covering his vision though not enough that he could not see his path, and drifted between the leaves and the trees. Quintus stopped. “Caelius!” He shouted; his voice resonated about, echoing in the distance, but there was otherwise no answer. “Caelius, where are you?” Nothing. He then noticed the absence of something else—the sounds of crushing leaves and twigs of their footsteps had disappeared; all he could hear was his own rising breath, raging through his ears as his heart thumped rapidly against his chest, though he thoroughly denied himself the fact that he was, indeed, slightly panicked. “Caelius, if this is a prank, I swear by the stone, I’ll have you counting grains until the rest of your days in the army!”

No answer.

Quintus thought he should turn back, ignore Caelius altogether, maybe claim he had deserted instead of telling the truth, for the sake of saving his own arse at least, and turned around. He trod on, now expecting for the narrow path to appear at any moment—but he walked, and walked, and walked, and nothing appeared. All he could see was a thick mesh of vegetation curling over himself as if nature wanted him trapped, and it was somehow becoming more suffocating by the step, the thorny bushes now not just tugging his clothes, but scratching his skin. His lance was nearly useless, and Quintus used his cape to protect himself against the savage vegetation, but it was getting harder to move—and he wondered where was the bloody path he had seen.

He stopped. The density ended, giving way to a clearing; ahead of him, in a tiny spot that opened up to a canopy of branches filled with heavy, green leaves, there was a slab of white stone, standing vertically against the brown earth, and another stone lying horizontally by its feet. Quintus neared it gently; a ray of moonlight fell right in the middle of the clearing, painting the small blotch of soil a pale silver, and when he squinted his eyes he noticed the dark blotch on the second slab was old, dried blood.

It was an altar, but as he neared to read the engraving on it, he realized he didn’t know the god’s or goddess’ name on it. Banduam sacrum. Perhaps it was one of the Lusitanian’s old gods, though he had never heard of that name.

Quintus stood up and looked around, now trying to comprehend just how he had ended up there, again focused on turning back—which he nearly did, until the loud crack of a snapping twig brought him back. He looked ahead, past the altar, and thought he saw something between the trees, a dancing shape that hovered about between trunks and twigs, and with his lance hoisted, gripping it strongly, he marched on.

He passed the thick meshes of vegetation, wrapped in his cape in care, and passed through two cypresses that grew in a strange manner, like two colossuses standing before a sacred entrance—how strange he felt at the connection he made. The moonlight seemed stronger there, perhaps because the trees weren’t filled with leaves, and it cast a single branch of light onto what he was positive, absolutely certain, to be a circular house with a roof made of thatch.

Just like the people there used to build.

Now, his senses were fully active, paying attention to sight, smell and hearing, not minding any physical inconvenience of his situation. He was right—it was a thatched house, circular and inserted into a small yard, surrounded by a circular wall—and there were more. More houses, laid about, just like a proper settlement. And not just houses—people were living there. He could see thin threads of smoke escaping the shy chimneys atop the roofs, and swore he could hear a child’s giggle somewhere, yet somehow the place felt stuck in absolute desolation, as if he walked among a ghost city of the past where nothing but death and absence existed.

“Caelius?” He called again, though now not in a shout, just an octave above his regular speaking voice—and no answer. Whatever sounds there were, however, they ceased; Quintus froze and focused on one of the houses, from where he could see the trembling light of perhaps a torch coming from below the wooden door, and thought of how primitive they seemed, living like renegade farmers, with nothing but sheep and their belligerent attitudes. The light shuddered and then flickered away, and he was cast into darkness.

In fact, it seemed it was far darker than before. Quintus turned around, and nearly screamed, lance now hoisted up in the air. Before him, on jutting branches of nearby trees, corpses hung—rotting, putrid and pale, swaying about in the fresh breeze as that nauseating salty scent returned, but now it was stronger and more revolting. It smelled of blood, of putrid meat, of fish.

Shuddering in dread, Quintus neared the corpses enough to look at them, and was trying to understand whether he had missed on them or they weren’t there just a moment before when he recognized two of the men. Maximus Arrius Opilio, another legionary, infantry like Caelius, who everyone assumed had deserted his post after getting into a gambling vice in a tavern that had earned him quite the debt, and Tertius Nepos Caepio, gone, simply gone, without a word or notice, from his post one night. Both had been guards in the city, though not anywhere near where Quintus and Caelius had stood—and now, they hung by the neck.

But they had not been hung, Quintus was quick to assess. They had bled—and a lot. Their clothes were ratty and thick with dried blood, and they showed several bruises and cuts—he assumed the killing blow to be the one at the neck, a swift slice across the trachea that looked clean, done by a strong hand, perhaps that of a man accustomed to war. But they showed more injuries: cuts along the arm, in precise, conspicuous places—as if they had been slowly bled out.

Quintus dreaded discovering why.

He gulped, but his mouth was dry; he looked around, studied again the thatch roof of every house, the wooden doors and even the silence—and though there was nothing, he was certain that place was inhabited still.

But it was impossible; the Lusitanians had been defeated, subdued, tamed; whatever savagery they had been up to, it couldn’t last long, and soon the Empire would crush them effectively and order would be restored, though the scene didn’t look like any sort of resistance, just a small settlement of people who refused to be civil and live under the law of Rome. Most likely, practising some sort of witchery with their gods, considering the mutilation on those poor guards and legionaries. He had to go back, he had to return and report the crime—now, Quintus only wished he could find the way there again, if he could find his way out first.

He gave a step forward, but from behind a tree, a large stick jumped and hit him in the stomach. Shoved, Quintus staggered back, and he was positive someone removed his helmet, just reaching in and casually taking it off, for a hard blow to his nape. He fell back against the ground and blinked his eyes wearily, falling dangerously to sleep. Fighting the haze, he looked up when a silhouette appeared, and saw a pale face crowned with black hairs that, a moment before, had been in complete disarray.

When he came to, he was tied with ropes and lying on a cold slab, and something warm burned to his left. Quintus wiggled in bondage, moved his head as the throbbing pain snapped behind his eyes, and found a burning bonfire right there, flames rising tall and mighty before a wave of cheers that erupted from an adoring crowd. His breath rose, his heart thumped—they all spoke a language he could not understand.

A hand grabbed him by the hairs, pulled him back and forced him to stare at the night skies. It was a full moon, he noticed, and tears popped from the lashes as he thought with certainty he was going to die. He wondered then how could no one see a bonfire that big from Caetobriga, burning right in the middle of the forest just outside its walls, or how had nobody found the hidden settlement of Lusitanian people, the same they had believed for years to have been tamed and subdued to order—even gone. The staggering, petrifying thought occurred then that he might not be in his world, but another—a world only those who served the strange god in the altar he’d found in the woods could enter.

He rolled his eyes to look at his captor, but there were two: the woman with black hairs, now far from the fragile, wailing mother who had lost a child to a boar. Instead, she appeared tall and mighty, her face contorted into a frown, corners of her lips turned into pure disgust, and a coldness to her blue eyes that made Quintus shudder in dread. But she wasn’t alone; someone else was by her side.

Caelius. His former jubilance, that had earned him so many punishments in the past, was gone, washed away by a semblance Quintus didn’t recognize anymore. Shadows were cast above his eyes, sombre and empty, as if nothing existed inside of him beyond a conspicuous objective he had set out to complete, and in his hollowness, there was a message of absolute desolation, loss and perdition. Quintus looked at his face, only partly kissed by the silver moonlight, and thought with absolute certainty that Caelius had never been the frolicking young man he had appeared to be, but a great actor set out to perform a precise play.

“Caelius,” Quintus called, his sobs coming then, so miserably crying he felt the unexpected taste of his own spit slipping through his wet lips, and his vision blurred. “What are you doing?”

“Caelius is what you roman scum call me,” he said—even his voice was different, lower somehow, and distorted, like nothing but a faint projection of a voice Quintus had grown bored of listening to in the past, brought by a gusting wind—but not his, not really his. “But my birth name is Caturo.” He looked to the side, and for the first time, shared a smile with the woman. “Meet my sister Aura, Quintus.”

“Wh—” his breath escaped him, and Quintus tried to say something logical, but there was shock and confusion only, far too much for him to completely grapple the full meaning of what was happening. “You’re betraying Rome! You’re betraying the g—”

“I’m serving my gods.” He produced a dagger from somewhere Quintus missed, though he was positive someone had passed him, and that someone had been the woman, seemingly named Aura. She smiled when she looked down at the blade, now dancing in her brother’s hand, and then at her prey, the man tied up on a slab—he finally realized—that was neither altar nor just stone, but a sacrificial table. In fact, it became so obvious to Quintus, when he looked down with an uncomfortable tilt of his head and saw dried blood all over, he wasn’t surprised.

“Those men—” Quintus mumbled. “Maximus, and Tertius—”

“Blood spilled for the glory of Bandua and Ataegina.” His lips twisted; the fire reflecting in his eyes, and Quintus thought he looked like a fresco of Vulcan he had seen in Rome in his earlier days—and though the memory was ridiculous, it made him flinch in pain. He missed his home. He missed Rome. He missed the simple life of a boy destined to become a legionary, unaware that he’d be so mediocre, at best he’d be a great sacrifice to a foreign god one day.

“You’ll b-be in… in trouble, C-caelius—”

The words fought against his beating heart, that seemed to push them down, one by one, with every flogging motion, but Quintus persisted—though it seemed useless. Caelius, or Caturo, only smiled wider, and slid a finger across the glinting blade of the dagger that now sparkled the refracted sparks of the bonfire.

“Tomorrow, I will tell Caetobriga you deserted. That you, nothing but a mediocre legionary who earned his living as a princeps, but who got so severely injured fighting a battle for Sulla his centurion simply quit him and sent him to Hispania to serve as a boring guard, saw a woman pleading for help as she ran away from a boar, and like the absolute coward you always were, Quintus, you fled. I will tell them you fled deep into the forest and were gone before I could stop you.”

“And they shan’t ever dream,” the woman said, her voice now lilting in a melodious tune of nothing short of absolute and utter joy, “that your blood ran for Bandua and Ataegina, for the strength of our men and our women, and those who will make roman blood run again.”

Quintus closed his eyes when she laughed; he thought her laugh was distorted, acute, and it hurt his ears just to listen. Now, he was panting, and from all around, strange chants in that alien tongue came, a tongue he had thought suppressed a long time ago, subdued to Rome’s will and tamed, but that now rose in a mellifluous song of sacrifice and bloodshed—and he was to be torn to shreds.

No, Quintus thought, snapping his eyes open as the blade rose, letting out a bellow before he felt it pierce deep into his flesh, tearing skin and clothes apart, and the warmth of his blood came. He wasn’t just going to be sacrificed; if the corpses of the men had told him something, it was that these Lusitanian barbarians were going to make him suffer in the name of Rome’s bloodshed.

---

A/N: The name Caturo is straight-up borrowed from Uma Deusa na Bruma, a book about the last lusitanian resistance that I cannot suggest enough.

Yes I used Aura again, it just seemed appropriate and I am lacking imagination rn

___

Past Challenges:

Wordtober Day 1: Ring

Wordtober Day 2: Mindless

Wordtober Day 3: Bait

Wordtober Day 4: Freeze

Wordtober Day 5: Build I

Wordtober Day 6: Build II

Wordtober Day 7: Enchanted (Encantada)

Wordtober Day 8: Frail

Wordtober Day 9: Swing

Wordtober Day 10: Pattern

Wordtober Day 11: Snow

(Skipped Day 12)

Wodrtober Day 13: Ash

Wordtober Day 14: Overgrown

Wordtober Day 15: Legend

4 notes

·

View notes