#margaret rosenblatt

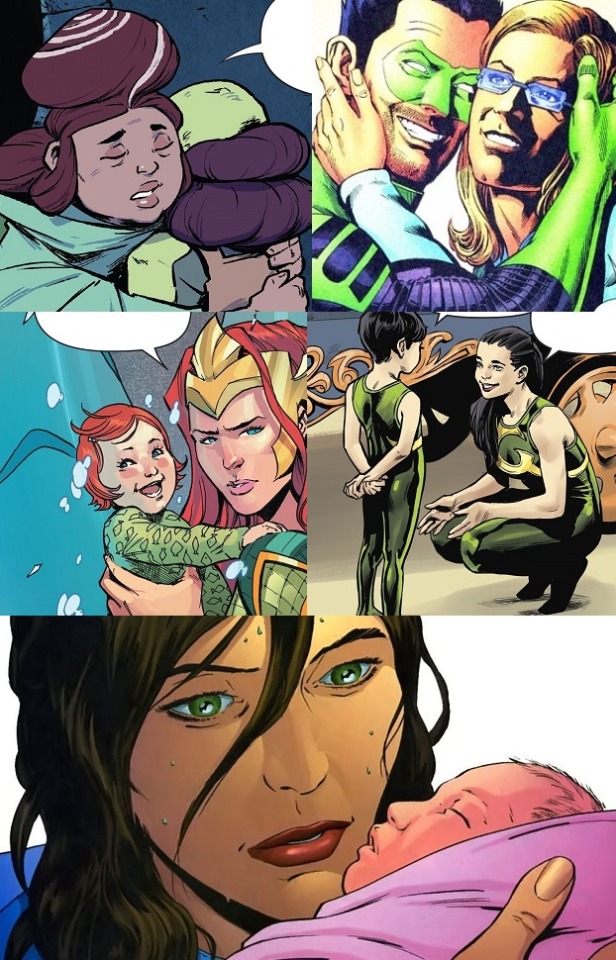

Photo

Happy Mother’s Day!

#comics#holidays#mother's day#rio morales#martha wayne#martha kent#bianca reyes#scarlet witch#big barda#lara lor-van#margaret rosenblatt#starfire#harley quinn#lois lane#selina kyle#mera#mary grayson#molly of pipetown#maura rayner#dolphin#queen ramonda#queen hippolyta#muneeba khan#princess annelle#tanya fox#rocket#spider-woman#linda park west#jessica jones#manhunter

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

do you guys think that post-Kaiju reveal (after the big homecoming dance/fight), Duncan starts to get increasingly worried about going back to school despite having saved them because what they think he’s a monster??? what if everyone hates him because of his dad? etc.

only for him to get to the school and see a shit ton of posters all over the hallways and doors about a brand new club. Everyone is talking about it, which confuses Duncan. Even more so because they talk about it alongside Duncan’s parents. Not even Duncan himself, but his parents??

The club was made over the weekend. The name? Monster Lovers Unite!

#firebreather#duncan rosenblatt#i really like the idea that#in an attempt to make duncan feel accepted#isabel makes a club for kaiju fanatics like her#but she severely underestimated the level of fanatism some people had#accidental monsterfucker club#but#monster lovers#cuz they’re in high school#isabel finds it hilarious#but vaguely disturbing#Duncan is downright horrified#especially when he learns that most club members voted for his mom as their sponser or idol or whatever#members keep going up to him asking- basically begging- him to introduce them to his mom#margaret finds it endearing and also funny#’highschoolers haha’#margaret rosenblatt#kaijus#duncan expected a killer mob after him#he got a mob alright#he’s unsure whether he wouldve prefered the killer one

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The OG monsterfucker.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Monster Fucker of the Day is Margaret Rosenblatt from Firebreather!

Margaret fell hard for the King of Kaijus, and honestly, who could blame her?

#mfotd#Firebreather#Margaret Rosenblatt#terato#btw SHE FUCKED A KAIJU#and if you look to your left you can see some of the Pacific Rim fandom sigh in envy

887 notes

·

View notes

Note

Sync, you haven't seen Firebreather did ya? Just look up Belloc and Margaret Rosenblatt from Firebreather. This two are married and had a KID. Credo and Evette banging is more plausible than that.

I hadn’t heard of that before today lol, so I went and googled the characters and.... is one of them a dragon? Like a straight up dragon? I...

Margaret, I don’t know who you is, but hats off to you, ma’am. You’re living the dream. 🤣🤣

Also thank you nonnie for the reassurance. 💖 I’m really happy there’s support for Evette taking that Angelo weenie. 😭🙏

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

What Does the Word “Liberal” Mean? – Law & Liberty

The West is facing its most profound identity crisis since World War II. Events and movements like Brexit, President Donald Trump’s promotion of American nationalism, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s celebration of “illiberal democracy,” and Poland’s Euroskeptic Law and Justice Party have unsettled Western elites. This anxiety is compounded by threats from increasingly aggressive autocratic oligarchies in Russia and China. Furthermore, there’s been a recent spate of popular books heralding, and even celebrating, the end of liberalism, such as Patrick Deneen’s Why Liberalism Failed (2018), Rod Dreher’s The Benedict Option (2017), and Yoram Hazony’s The Virtue of Nationalism (2018).

These works, written from a broadly conservative viewpoint, have exposed a rift within American conservatism. On the one hand, some conservatives defend a form of classical liberalism (what I and others have called Natural Law Liberalism; see here and here) exemplified in the principles of the American Founding, and regard modern liberalism (or progressivism) as a corruption of classical liberalism. On the other side of the conservative divide are the new anti-liberals, who reject liberalism tout court as a destabilizing, despotic, or even incoherent public philosophy.

Those who follow this debate will be interested in what historian Helena Rosenblatt of the City University of New York has to say on the subject. Rosenblatt’s The Lost History of Liberalism: From Ancient Rome to the Twenty-First Century, while ultimately disappointing, helps highlight the formidable challenge, if not impossibility, of settling on a single meaning of liberalism.

Multiple Definitions

When an ancient Roman heard the word “liberal” he thought of someone who possess the virtue of “liberality,” or generosity. When most Americans hear the word “liberal” they think of Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton. When most Europeans hear the word “liberal” they think of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan. Some scholars trace the roots of liberalism to Christianity, whereas others trace it to a “battle against Christianity,” to quote Rosenblatt (emphasis in original). This makes one wonder whether the word has any meaning at all.

According to the author, most scholars make the mistake of first defining liberalism and then recounting its history, but this “is to argue backward.” We human beings cannot, like Humpty Dumpty proposed, make words mean whatever we choose them to mean. “If we don’t pay attention to the actual use of the word,” Rosenblatt writes, “the actual histories we tell will inevitably be different and even conflicting. They will also be constructed with little grounding in historical fact and marred by historical anachronism.”

She points out, for example, that “the word ‘liberalism’ was not coined until the 19th century, and for hundreds of years prior to its birth, being liberal meant something very different.” For Rosenblatt, this means that the application of the concept to figures like John Locke, Thomas Jefferson, and Adam Smith is already problematic. Moreover, she usefully reminds her readers that many of the most prominent advocates of liberalism, although hostile to the ancien régime, were no friends of democratic government. The anti-democratic suspicions of most of the American Founders—not to mention more recent arguments like Jason Brennan’s Against Democracy (2016)—are at the service of liberal concerns.

So Rosenblatt proposes to determine the “meaning of liberalism” by attending to “how liberals defined themselves and what they meant when they spoke about liberalism. This is a story that has never been told.”

The story Rosenblatt tells is an engaging one, and her effort to pin down the meaning of liberalism with history is commendable. But her project ultimately founders against two obstacles, one formal, the other substantive.

Semantics and Social Realities

The formal problem is that the meaning of a word cannot be determined by history—or even by etymology—any more than it can be determined by ahistorical philosophy. As Rosenblatt herself indicates in the passage quoted above, meanings are determined by “actual use.” But the actual use of language, as F.A. Hayek often pointed out, is largely determined by rules which are (to use one of Hayek’s favorite lines from Adam Ferguson) “the result of human action but not of human design.” That is, although these rules are made by human beings, they not imposed a priori, but emerge spontaneously from the actions of individuals. Thus anachronisms can become idioms, so that just as a word like “Puritan” can be meaningfully applied to contemporary individuals and events, a word like “liberalism” can be meaningfully applied to earlier ones.

This semantic difficulty is compounded by the fact that the word “liberalism”—unlike, say, “tree”—has no objective, or extra-mental, referent to which we can point. It is what John Searle calls a “social reality,” whose meaning is constituted entirely by our intentional use of it.

The upshot is that although “liberalism” has a determinate range of meanings, the differences within that range can never be settled in an objective or impartial way. Within that range, the best we can do is make clear what we mean when we use the term.

The substantive problem is the bias Rosenblatt brings to her story of liberalism. Despite their pretenses to objectivity, histories are usually determined by a (usually unacknowledged) non-historical theoretical and evaluative framework that dictates which “facts” to highlight and how they should be ordered in relation to one another. Rosenblatt’s framework shows through in significant ways, of which I will highlight just two.

First, although she claims a purely academic interest in the meaning of liberalism (there is no mention in her book of the political developments with which I began this review), her tone reveals a more polemical purpose: to oppose a liberalism that affirms individualism, self-interest, and rights, and to promote a liberalism that affirms “duties, patriotism, self-sacrifice, [and] generosity to others.” This for Rosenblatt means downplaying the Anglo-American writers and thinkers, and highlighting the Continental ones.

Thus she writes: “The idea that liberalism is an Anglo-American tradition concerned primarily with the protection of individual rights and interests is a very recent development in the history of liberalism.” Again: “The truth is that France invented liberalism in the early years of the nineteenth century and Germany reconfigured it half a century later. America took possession of liberalism only in the early twentieth century, and only then did it become an American political tradition.” And once more: “At heart, most liberals are moralists. Their liberalism had nothing to do with the atomistic individualism we hear of today. They never spoke of rights without stressing duties.”

These are questionable assertions, both as history and as political advice. If she had read Paul A. Rahe’s Soft Despotism, Democracy’s Drift (2009), she would have traced the original sources of French liberalism to Anglo-liberalism through the singularly influential writings of the Baron de Montesquieu, who, as if with Brexit on his mind, predicted that “in Europe the last sigh of liberty will be heaved by an Englishman.” (This quote is to be found in Rahe.) Surprisingly, Rosenblatt mentions Montesquieu only twice, and in passing reference.

She also would have seen how French liberals like Jean-Jacques Rousseau explicitly repudiated the Anglo model, with adverse consequences for French political history from the Revolution of 1789 to the present day. Rosenblatt relates much of that unfortunate 19th century history: the “brutal dechristianization campaign”; the Reign of Terror; the alternating cycles of mob violence and autocracy. Rahe puts it in larger perspective:

In the period since 1789, [France] has known five republics, two monarchies, two empires, and a dictatorship far more popular initially than anyone in postwar France was inclined to admit. Moreover, in this period, the French have lived under so many different constitutions—some say sixteen—that it is hard to keep count. Under each and every one of these regimes and constitutions, however, there has been one crucial element of continuity. Through thick and thin the administrative apparatus of the State has steadily grown in weight, in power, and scope. Today, more than one-quarter of those in the French laboring force work for the State, and the functionaries of that entity regulate daily life in minute detail.[1]

Yet this is the country we are to look to for a salubrious model of liberalism? It is strange that Rosenblatt focuses here, rather than following the French liberal Alexis de Tocqueville to the liberalism of England and America. There she could have found, alongside the promotion of individual and political liberty, a real, if more sober, endorsement of “duties, patriotism, self-sacrifice, [and] generosity to others.”

Liberalism’s Deepest Root

Secondly, there is the manner in which The Lost History of Liberalism addresses Christianity. Although Rosenblatt refers to “liberalism’s fraught relationship with religion” as “perhaps the most important issue of all,” and although she relates many of the historical conflicts between orthodox Christianity and liberalism, it is not clear she understands what is really at issue.

The author is keen to highlight continuities between liberalism and the ancient political tradition, which is where she hopes to ground a more ennobling, public-spirited version of it. Thus she strains to establish a conceptual and etymological link between liberalism and the classical moral virtue of “liberality” (liberalitas), which she describes as “the moral and magnanimous attitude that the ancients believed was essential to the cohesion and smooth functioning of a free society.” She also points out that “liberals saw themselves as fighting for the common good and continued to see this common good in moral terms.” But she completely overlooks the profound rupture Christianity makes in the ancient conception of politics and the common good, and the enormous task of coming to grips with that rupture. While she devotes pages to 19th century liberal Christianity, Rosenblatt never once mentions Francisco Suárez or the School of Salamanca, which speaks volumes about her blind spot on this subject.

Before Christianity, religion and politics were, even if differentiated into distinct spheres, integrated into a comprehensive unity of membership. In the ancient world, each city had its own gods and its own cult, and so blasphemy was also treason. Even the freest city, Athens, put Socrates to death for bringing strange gods into the city.

Christianity—a universal, transpolitical, comprehensive and salvific religion—fundamentally transforms the meaning of politics, citizenship, and the common good. After its arrival, political membership can no longer be the highest form of membership, and the common good of the polis can no longer be the most comprehensive common good. This does not mean that political life no longer has a common good; it only means that the political common good will be limited and instrumental to modes of human flourishing that are not themselves political. Civil society is largely the ramification of Christianity.

Arguably, this separation of religion from politics is the deepest root of liberalism, and it has taken two millennia of thought and action to work out what it means in practice, a work that is not yet finished. It is precisely this separation that bothered the French liberals whom Rosenblatt admires, and their animosity led to the “brutal dechristianization campaign” of which she speaks. Thus Rousseau writes in The Social Contract (1762):

By separating the theological system from the political system, [Christianity] brought about the end of the unity of the State, and caused the internal divisions that have never ceased to stir up Christian peoples . . . Everything that destroys social unity is worthless. All institutions that put man in contradiction with himself are worthless.

Remarkably, in this long history, the author never directly raises (much less answers) the question of the proper scope and limits of political power. But we ought not forget that, for most people, this is the question at liberalism’s heart. This vast gap renders the book’s appeals to duties, patriotism, and the common good empty and equivocal. Reading it to the very end, one still does not know what liberalism is.

The Lost History of Liberalism is a timely, ambitious work. While it cannot be completely blamed for failing to settle the true meaning of liberalism, it can be blamed for its Continental partiality. I share Helena Rosenblatt’s desire to ground a humane, non-individualistic form of liberalism; I only wish she would have looked more closely at the deep resources within her own Anglo-American tradition.

[1] Paul A. Rahe, Soft Despotism, Democracy’s Drift: Montesquieu, Rousseau, Tocqueville, and the Modern Prospect (Yale University Press, 2009), pp. 230-231.

!function(f,b,e,v,n,t,s)if(f.fbq)return;n=f.fbq=function()n.callMethod? n.callMethod.apply(n,arguments):n.queue.push(arguments);if(!f._fbq)f._fbq=n; n.push=n;n.loaded=!0;n.version='2.0';n.queue=[];t=b.createElement(e);t.async=!0; t.src=v;s=b.getElementsByTagName(e)[0];s.parentNode.insertBefore(t,s)(window, document,'script','https://connect.facebook.net/en_US/fbevents.js'); (function(d, s, id) var js, fjs = d.getElementsByTagName(s)[0]; if (d.getElementById(id)) return; js = d.createElement(s); js.id = id; js.src = "http://connect.facebook.net/en_US/sdk.js#xfbml=1&version=v2.5"; fjs.parentNode.insertBefore(js, fjs); (document, "script", "facebook-jssdk"));

The post What Does the Word “Liberal” Mean? – Law & Liberty appeared first on NEWS - EVENTS - LEGAL.

source https://dangkynhanhieusanpham.com/what-does-the-word-liberal-mean-law-liberty/

0 notes

Text

Asian American Real Estate Association of America (AREAA) Will Hold Their Fourth Annual East Meets West Real Estate Connect Conference

New Post has been published on https://is.gd/c9j0j9

Asian American Real Estate Association of America (AREAA) Will Hold Their Fourth Annual East Meets West Real Estate Connect Conference

NEW YORK/ SEPTEMBER 13, 2018 (STL.News)

AREAA, the Asian American Real Estate Association of America, will hold their Fourth Annual East Meets West Real Estate Connect conference on September 26, 2018, at The New Yorker. Every year, East Meets West shines with an array of prestigious speakers, a fast-paced, interesting itinerary and great networking opportunities.

“East Meets West was created to serve as a starting point for foreigners looking for real estate advice to engage with local experts in the industry. It has since evolved into an all-day event loaded with real estate professionals ranging from developers, owner/operators, investors, lenders, and service providers, mingling with attendees eager to learn,” says Dorian Lam, President, Board of Directors, Asian Real Estate Association of America (AREAA) NY Manhattan Chapter.

This year’s four keynote speakers, highly regarded professionals in their respective fields, are John Catsimatidis, Chairman and CEO of Red Apple Group; Streeteasy’s General Manager Susan Daimler; Adam Spies, Chairman and CEO of Cushman and Wakefield, and Jonathan Miller, President and CEO of Miller Samuel.

“More speakers not to be missed include Jessica Millet, an expert on Opportunity Zones, who will give the latest updates on the new tax program, Blockchain consultant Debbie Hoffman, and Compass Chief Evangelist Leonard Steinberg. Developers play a big role at this year’s East Meets West as well, with three sessions filled with developers and even a development case study,” says Dorian Lam.

This year, the event will be broken down into eight sessions, each covering a contemporary, highly relevant topic both in commercial and residential real estate. Highlights include a session on residential new development, the changing real estate landscape, foreign lending, and business expansion.

Here is a full overview of this year’s panels:

Residential Panels

Residential Panel 1: Business Expansion – What investments to your business actually work?

Speakers include Tyler Whitman (Triplemint), Russ Putterman (KW), Tony Oakley (Compass), and Teddy Baxter (Douglas Elliman).

Residential Panel 2: Foreign Lending (New Policies and Programs)

Speakers include Charles Ruffin (Emigrant), Henry Shih (Citi), and Yihou Han (Sterling).

Residential Panel 3: Tech Tools You Should Know

Speakers include David Friedman (Wealthx), Alyssa Soto Brody (Compass), Parish Pradhan (RealAgentz), and Noah Rosenblatt (Urbandigs).

Residential Panel 4: Condo New Developments – What Developers Want

Speakers include Sam Suzuki (Suzuki Capital), Anna Zarro (AnnaZarro), and Leonard Steinberg (Compass).

Commercial Panels

Commercial Panel 1: State of the Market

Speakers include Ari Shalam (RWN), Richard Siu (F&T), Patrick Li (TH Real Estate), Johnny Din (Cycamore Capital), and Jessica Millet (Duval & Stachenfeld).

Commercial Panel 2: Developers Panel

Speakers include Daren Hornig (Hornig Capital), Eric Brody (Wonderworks), George Xu (Century Development), and Ronald Chua (China Overseas America).

Commercial Panel 3: Capital Markets

Speakers include George Bernakis (Industrial Bank of China), Leon Wang (Acore Capital), Jason Yuen (Greystone), and Jerry Tang.

Commercial Panel 4: Development Case Studies

Speakers include Margaret Lee (Youngwoo & Associates), David Amirian (Amirian Group), Ray Gu (Anbang International), and Robert Gladstone (Madison Equities).

With such a vast variety of topics, guests and panelists alike will be able to learn, grow, and leave with a better sense of today’s real estate reality. East Meets West’s Slogan, “Real Estate Gets Real”, sums up this purpose perfectly.

About AREAA

The Asian Real Estate Association of America (AREAA) is a nonprofit professional trade organization dedicated to promoting sustainable homeownership opportunities in Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) communities. AREAA creates a powerful national voice for housing and real estate professionals that serve this dynamic market. AREAA’s membership represents a broad array of real estate, mortgage, and housing-related professionals that serve the diverse AAPI market. AREAA is the only trade association dedicated to representing the interests of the entire Asian real estate market nationwide.

_____

SOURCE: https://www.prweb.com/releases/asian_american_real_estate_association_of_america_areaa_will_hold_their_fourth_annual_east_meets_west_real_estate_connect_conference/prweb15754051.htm

#AREAA#Asian American Real Estate Association of America#Asian-American#Blockchain#Dorian Lam#East Meets West#East Meets West Real Estate Connect#keynote speakers#real estate#Residential Panels#The New Yorker#TodayNews

0 notes

Photo

(via GARN PRESS: FREE EBOOK DOWNLOAD: Great Women Scholars: Yetta Goodman, Maxine Greene, Louise Rosenblatt, Margaret Meek Spencer)

0 notes

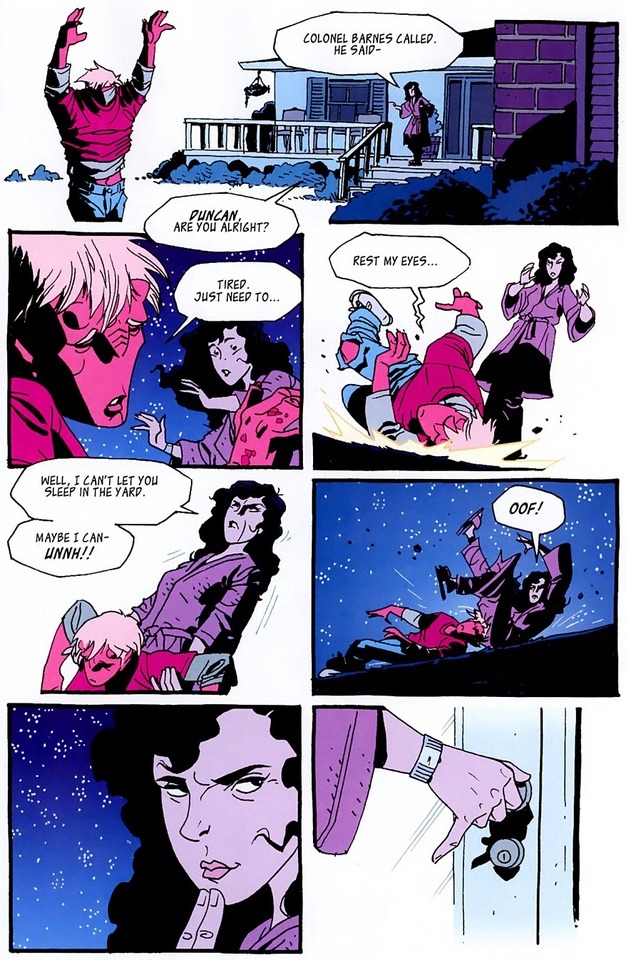

Photo

Firebreather, Vol. 2, #1

#comics#image comics#firebreather#duncan rosenblatt#margaret rosenblatt#the sheer mechanics of it are still mind-boggling

223 notes

·

View notes

Text

Firebreather x How to Train Your Dragon AU

I originally thought that Belloc should be one of the Big Dragons, but i want Belloc and Margaret to be a thing and im not going to turn to unseemly things for that to happen. SO, Human!Belloc is Stoick and Margaret is Valka. Except that there’s a twist in comparison to the original.

Valka!Margaret remains in the village as chief. Stoick!Belloc was indeed a beast of a man, but he considered Dragons to be above humans. He didnt want to control them, at first, per se, but he wanted to learn how to fight like them, how to be like them. He wanted to lead the village into being like the dragons, but when he brought this up with Margaret they had a huge fight about it. And during the next dragon raid, Belloc was “overtaken” and taken away by dragons.

Margaret is heartbroken, and regrets that the last time they ever talked was when they fought. Maybe if she had just listened. But she buries all the regret and what-if’s, substituting it for anger and hatred towards dragons.

Duncan would be Hiccup, obviously, except a lot moodier. Instead of the scar on his chin from when the dragon broke into their house, he has a burn scar that goes from his neck to down his chest. Not from the dragon’s actual firebreath, but from that liquid fire that falls from their mouths sometimes.

I feel like i could a lot more from this au, because it would be just so fun to play around with the two different plots

#firebreather#duncan rosenblatt#margaret rosenblatt#belloc#how to train your dragon#hiccup haddock#stoick the vast#valka haddock#crossover#au

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

I suggest a mfotd to be Margaret Rosenblatt from Firebreather. I mean she had a son with a FREAKIN' KAIJU....HOW?

Thank you for the submission, but Margaret’s already been featured!

But yeah, HOW DID SHE DO THAT?? Can he shapeshift?? I need answers.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

100x100 icons: Margaret from Firebreather (film)

Link to icons - Located on my Google Drive, will update over time

#icons#firebreather#firebreather rp#Margaret Rosenblatt#I'll post the links to the other icons soon#I just need to get more of them before I post the links

1 note

·

View note

Photo

(via GARN PRESS: EBOOK LAUNCH: Great Women Scholars: Yetta Goodman, Maxine Greene, Louise Rosenblatt, Margaret Meek Spencer)

0 notes

Photo

(via GARN PRESS: NOW AVAILABLE! Great Women Scholars: Yetta Goodman, Maxine Greene, Louise Rosenblatt, Margaret Meek Spencer)

0 notes

Photo

Mother’s Day | Margaret Rosenblatt

#comics#mother's day#margaret rosenblatt#firebreather#duncan rosenblatt#belloc#she landed dragon D#she deserves all the awards#and some ice for that actual burn

120 notes

·

View notes