#lyndall gordon

Text

This is an informative and entertaining talk about “Five Women Writers Who Changed the World” by the award winning South African author and Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature and Fellow of St. Hilda’s College, Oxford, Lyndall Gordon. The five women writers are Mary Shelley, Emily Brontë, George Eliot, Olive Schreiner, and Virginia Woolf. Press the play button in the link to start the talk. You can see the talk in full screen mode directly from YouTube.

Near the end of the talk, Lyndall Gordon relates a wonderful proposition by Virginia Woolf’s Quaker aunt, Miss Stevens, for a third House of Parliament, a consultative body composed of women and elected by women who would eschew the traditional framework of adversarial government and would instead employ the tenets of preservation, nurture, sympathy, compromise, and listening.❤️

youtube

0 notes

Text

Introduction: Frog Conjunctions

The Pregnant Virgin is a study in process. In its conception, it was called Chrysalis. By the time it was born, the baby had outgrown its chosen name. Its skeleton—the process of metamorphosis from caterpillar to chrysalis to butterfly—was intact. The whole, however, had become more than the sum of its parts. The parts concentrate on the periods in the chrysalis when life as we have known it is over. No longer who we were, we know not who we may become. We experience ourselves as living mush, fearful of the journey down the birth canal. The whole has to do with the process of psychological pregnancy—the virgin forever a virgin, forever pregnant, forever open to possibilities.

The analogy between the virgin with child and the chrysalis with butterfly does not originate with me. In ancient Greece, the word for soul was psyche, often imaged as a butterfly. The emergence of the butterfly from the chrysalis was analogous to the birth of the soul from matter, a birth commonly identified with release, hence a symbol of immortality. The Divine Child, the Redeemer, the child of the spirit shaping in the womb of the virgin, finds a natural image in the winged butterfly transforming in the chrysalis, preparing to be free of the creature that crawls on its belly. This book does not, however, make the traditional body/soul distinction between caterpillar and butterfly, mortal and immortal life. Rather it explores the presence of the one in the other, suggesting that immortality is a reality contained within mortality and, in this life, dependent upon it. The Pregnant Virgin, that is, looks at ways of restoring the unity of body and soul.

Flora, one of the figures in Botticelli's Primavera, captures the paradoxical external stillness and internal kindling of pregnancy. She embodies the evanescent beauty of the maiden blossoming into womanhood. As the shy earthnymph Chloris, she has surrendered to the breath of Zephyr, and is now being awakened into the calm, luxuriant Flora. Like Mary, impregnated by the Holy Spirit, she stands radiant and full of grace, her femininity forthright and lyrically tender as she looks the beholder straight in the eye.

Writing The Pregnant Virgin has been a nine months' pregnancy. The book rejected its preconceived pattern; it evolved in its own metamorphic process. Last August in my second month, I suffered severe morning sickness. One look at an expanse of white paper made me ill. I feared a miscarriage. Then, as usually happens when I am conscious enough to ask the right question, the answer came in a dream:

I am sitting on steps near the waters of Georgian Bay. I am attempting to roll a big lily pad into the shape of a cylinder. It won't do what I want it to do. One end keeps falling open as I hold the other end rolled. Behind me is an old hotel. Two men are fighting on the balcony. I can feel their blows in my bones. I think I should try to do something about that, but a voice says, "Fashion your pipe."

I continue with the lily pad, and suddenly one man throws the other off the balcony, right over my head. Now I really must do something. I am about to rise when the voice commands again, "Fashion your pipe."

Now I understand—I am creating an instrument. I see beside me and a little behind, a huge smiling frog sitting in a po of green eggs, immensely proud of herself and waiting for me to finish the piccolo-pipe so the eggs can go through and be played into meaningful sounds.

I woke up knowing what the problem was. Instead of putting my full concentration into making the "pipe," I was allowing my energy to be drained by the blows of the two men on the balcony. Their voices I knew well enough: "Forget writing. Live your life as you always have. You can't write anyway." But there was another voice, a submerged feminine voice, tenacious and proud: "I want to write, but I don't want to write essays. I want to write my way." There was the impasse.

I walked through the bush to Iris Bay. I thought about the water lily—the Canadian lotus, whose blossom carries much the same symbolism as the rose. Its roots grow deep in the life-bestowing mud, sending nourishment up the sturdy stem to the leaves and flowers. Serene in its creamy white simplicity, the blossom opens petal by petal to the sun, symbolic of the Goddess—Prajnaparamita, Tara, Sophia—Creation opening herself to Consciousness. She is the blossom in the heart, the knowing, the dawning of God in the soul. Her divine wisdom brings release from the passion and pain of ego desire.

I picked a lily pad. I concentrated on fashioning my pipe. I remembered my grinning frog. Surely the lotus leaf was the right instrument to pipe her eggs. But how? How does one put psychological concepts through a lotus leaf? What would frog syntax sound like? How would it conjunct? Certainly not with "and," "but," and "for." It would have much more to do with leaping through the air from lily pad to lily pad, leaping intuitively with the imagination, or swimming through water. Leap—leap—out of sheer faith in my froggy instincts. Leap—trusting in another lily pad. Leap—knowing that other frogs would understand. Leap—leap—remembering my journal that looks like a Beethoven manuscript—blots, blue ink, red, yellow and green, pages torn by an angry pen, smudged with tears, leaping with joy from exclamation marks to dashes that speak more than the words between, my journal that dances with the heartbeat of a process in motion. How does one fashion a pipe that can contain that honesty, and be at the same time professionally credible? How can a woman write from her authentic center without being labeled "histrionic" or ''hysterical"? Splat! Long Pause!

And then my frog spoke from the mud.

"Why don't you write as you feel? Be a virgin. Surrender to the whirlwind and see what happens."

"Impossible!" I replied. "I'm not going to make a fool of myself. I'm not going to set myself up to be shot down. I know the guns too well."

That conversation put Chrysalis into a cocoon. For weeks I tried to find a syntax that could simultaneously contain the passion of my heart and the analytic detachment of my mind.

I was encouraged by a picture of an Indian Goddess holding her hands in a gesture that would contain the lily pad. Known as "link of increase," meaning "marriage" or "coronation," its highly differentiated fingers seem to cradle a pearl or flower. The tips of the two middle fingers, gently brought together, symbolize a coincidence of opposites. Some firm, gentle, androgynous style seemed to be indicated.

Further enlightenment came with Nietzsche's essay "Truth and Falsity," in which he writes, "I'm afraid we are not rid of God because we still have faith in grammar." Yes, I did feel answerable to that hatchet god—Jehovah, by whatever name—that god who stares down with his "thou shalts" writ in stone, a demonic parody of the creative imagination. Unaware of leaping, he keeps everything concrete and literal.

And then I read Carolyn Heilbrun's review of Lyndall Gordon's biography of Virginia Woolf. Heilbrun points out that Woolf was, like all women, trained to silence, that "the unlovable woman was always the woman who used words to effect. She was caricatured as a tattle, a scold, a shrew, a witch." Women felt "the pressure to relinquish language, and 'nice' women" were quiet. She concludes that "muted by centuries of training, women writers especially have found that when they attempted truthfully to record their own lives, language failed."

If that is true of the artist, it is no less true of any woman attempting to speak with her own voice. It is also true of the man who dares to articulate his soul process. The word "feminine," as I understand it, has very little to do with gender, nor is woman the custodian of femininity. Both men and women are searching for their pregnant virgin. She is the part of us who is outcast, the part who comes to consciousness through going into darkness, mining our leaden darkness, until we bring her silver out.

Anyone who tries to work creatively understands this. I remember, for example, when I was directing creative theater with high school students. We worked without a script for months before the show. Students who were trained to "give a good performance" found the process intolerable. Their rigidity, their fear of being "the hole in the program" blocked their creativity. They waited to be told what their lines were, what their moves had to be, what their attitudes should be. The quiet introverts who were accustomed to dropping into their own space had no difficulty concentrating until the images that sprang from their own bodies came alive. They loved being free. They loved to play. They loved to be challenged to go deeper into the darkness, to allow whatever wanted to happen to happen.

And things did happen. The whole theater came alive with roars, tears, laughter, movements of poignant beauty and hilarious irony. The curious visitors who ventured through the theater door shook their heads and fled from the chaos. But for those of us inside, it was contained chaos. We were used to the intensity. Two months before the show, the students, the dance director, the music director and I decided what movements we wanted to explore further, what poems, what music. This basic skeleton was added to and subtracted from until the very last performance.

All of us involved, whether actors, directors or stagehands, were responsible for our own process. As our confidence grew, for example, our energies increased, and our student stage manager had to look within himself to find new ways of keeping discipline backstage without destroying the fire. At the time, I had no conceptualized idea of what was going on. In retrospect, however, I see our theater as the womb of the Great Mother in which the virgin souls of the students came to birth in their own bodies and emerged to a level of psychological consciousness, confident enough and flexible enough to allow the wind of the spirit to blow through. Part of their process was to recognize in themselves and in each other whether their poem or dance was being allowed to live its own life or whether they were obstructing it with "a good performance."

What we were interested in was individual process, group process and eventually process between the audience and the cast. Since it was theater-in-the round, the students usually seated their parents so that at some point in the program they would kneel two feet away and look them straight in the eye. More than one parent found the naked encounter with their own adult-child overwhelming, and struggled to choke back the unexpected tears.

What we were not interested in was product or external performance. In the Tostal, the theater, there was no examination, no predetermined goal, no such thing as failure except betrayal of the process. In other areas of the school we might undergo dismemberment—history student in Room, poor athlete in the gym, excellent flutist in the music room. Culturally, we might also be dismembered—smelly feet in the shoe store, myopic eyes at the optometrist's, armpits in the drugstore, acne at the doctor's. In that room, we took our bodies out of the culture that tinkered with its parts. There we could be whole. We came from our own place of vulnerability, and by staying with that vulnerability we perceived our own strength and our own wounds.

The Pregnant Virgin is coming from that same place. All my analysands are a part of this book. Together we have experienced death and rebirth, together we have analyzed hundreds of dreams. Many of the repetitive motifs introduced in my two earlier books are further developed here. While many of my analysands have eating disorders and hence struggle with some form of food addiction, their psychological framework has much in common with those who are addicted in other ways—to work, alcohol, drugs, sleep, futile relationships, etc. The soul material presented here, my analysands have generously agreed to share, in the hope that it will shed some light on emerging feminine consciousness. Knowing that others are on the same demanding journey seems to ease the load.

I, too, am on the journey. The process that goes on in the kitchen in chapter I is the same process that goes on in India in chapter 7, with one crucial difference. The butterfly on the curtain (page 13) is transforming according to the laws of nature; the butterfly on the ceiling (page 178) is transforming through the fire of conscious choice. And this book too is on the journey. Two of the chapters were originally written for lectures, two for journals, and the others are attempts to wrestle light out of darkness. Each one is a prism through which the difficulties of Becoming and Being may be looked at from different angles.

I have not yet solved the problem of frog conjunctions, but my frog is still laying eggs. I think she enjoys my syntactical pregnancy. Meanwhile, this is not an apology for a polliwog. It is a challenge to myself and my readers to listen with the heart, to hear the language that lives in the Silence as surely as it lives in the Word.

--Marion Woodman en "The pregnant Virgin"

0 notes

Text

#ONCE AGAIN I AM SO FAR UP LYNDALL GORDON'S ASS THAT I HAVEN'T SEEN THE SUNLIGHT IN WEEKS#AND WE OWE IT ALL TO EMILY HALE AND HER REFUSAL TO DESTROY HIS HALF OF THE CORRESPONDENCE#T.S. ELIOT#POETRY

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

It was reported that one woman, who had undertaken not to marry unless she found the equivalent of Mr Knightley, had now put this ideal aside in favour of Professor Emanuel. Charlotte teased Cornhill, recalling George Smith’s dismay: ‘You see how much the ladies think of this little man, whom you none of you like.’

from Charlotte Brontë: A Passionate Life, by Lyndall Gordon

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

tagged by @saintflint to answer some questions 🌟

last song • sadder badder cooler by tove lo

three ships • honest to god i haven’t thought about any in a while but i guess if i had to pick some it’d be poe & finn (star wars), emily & sue (dickinson), and eduardo & mark (the social network)

currently reading • lives like loaded guns by lyndall gordon

last movie • speak no evil

craving • someone laying on top of me and/or a pretty long hug

tagging @junebuglove @ivythayer @easeupkid @onlymilkteeth @lifevialoving and @boyishs but only if u want !!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

tag 9 people you want to get to know better!

tagged by @macpye, thank you for the tag!

Three Ships of All Time:

I swear I give different answers to this every time I’m asked. This time I’m going to go with Phryne Fisher/Jack Robinson (Miss Fisher’s Murder Mysteries), Arthur/Eames (Inception) and Frank Castle/Karen Page (Daredevil/The Punisher).

First Ever Ship:

Éowyn/Faramir from The Lord of the Rings. “It reminds me of Númenor” is such a line.

Last Song:

Downtown by Macklemore & Ryan Lewis ft. Melle Mel, Grandmaster Caz, Kool Moe Dee and Eric Nally - @auntieclimactic blazed into my Discord with this bop and there is a lot going on in it. Mostly mopeds.

Last Film:

胭脂扣 (Rouge), a 1987 film by Stanley Kwan in which Anita Mui is a high-class courtesan in 1930s Hong Kong and Leslie Cheung is the wealthy playboy with whom she has a doomed romance and 53 years later she pops up as a ghost haunting some poor journalists in the 1980s. It’s very beautiful and tragic. They’re very beautiful and tragic.

Currently Reading:

I’m usually reading multiple books at once. Presently I’m at the beginning of The Hyacinth Girl by Lyndall Gordon, about T. S. Eliot and the four women who influenced his writing (most notably said “hyacinth girl” Emily Hale); in the middle of Pulp III, the third out of five volumes in Shubigi Rao’s series on book preservation and destruction; and at the end of Vertical: The City From Satellites To Bunkers by Stephen Graham, which examines the built environment from a three-dimensional perspective, up and down. I’m also listening to the audiobook of Mexican Gothic by Silvia Moreno-Garcia (evil mould: MY WORST NIGHTMARE).

Currently Watching:

Just got a free trial for Acorn TV so am powering through a Miss Fisher rewatch. Have also just finished Reservation Dogs, which I highly recommend.

Currently Consuming:

Vitamin C orange-flavoured gummies

Currently Craving:

Egg tarts, the Hong Kong style ones. I recently had something that was purportedly a Chinese egg tart but was actually sesame-flavoured? A travesty.

I’m afraid I’ve done too many of these of late to have people left to tag - I hate to inflict tagging on others! - but if you would like to do this please do! I always want to get to know people better.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

My time with Mrs. Dawson…

Vindication : a life of Mary Wollstonecraft

by Gordon, Lyndall (2006)

0 notes

Text

After visiting relatives in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and giving a lecture at the University of Minnesota, T.S. Eliot was aboard the RMS Queen Mary on this day in 1956; nearly half way to England, the poet suffered a heart attack and was tended to by ship's doctors. Upon arrival in Southampton, he would be taken off the ship in a chair [pictured] and whisked away to a local hospital. Eliot, 67, who had had experiences with heart trouble prior to his boarding the Queen Mary, would recover to live another nine years.

Source:

The Harvard Crimson

T.S. Eliot, An Imperfect Life by Lyndall Gordon

Photo: T.S. Eliot aboard the Queen Mary (Getty Images)

#rms queen mary#cunard#maritime#history#transatlantic travel#on this day#steamship#ocean liner#famous passengers#cunard white star#TS Eliot

0 notes

Quote

It was her religion to make the best of everything.

Lyndall Gordon

987 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Life is but a jest, and often a frightful dream, yet I catch myself every day searching for something serious, and feel misery from the disappointment.

Mary Wollstonecraft

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Incontri – Emily Dickinson][Thomas Govoni][Erica Dalle Luche][Lorenza De Luca][Michelle Reviglio]

La storia di Emily approfondita e scomposta in tre racconti erotici e autoconclusivi di tre periodi molto diversi della sua vita.

Emily Dickinson è stata una grande poetessa, ma solo dopo la sua morte ci si è resi conto dell’importanza delle sue opere per la letteratura statunitense e mondiale. Emily però è stata anche una donna nel XIX secolo, e non una delle più convenzionali: lesbica, con un amore impossibile e una vita ricca di avvenimenti, ha vissuto una moltitudine di eventi, alcuni tragici e altri divenuti leggenda.…

View On WordPress

#2021#comics#Emily Dickinson#Erica Dalle Luche#fumetti#graphic novel#Italia#Laura Guglielmo#letteratura gay#letteratura grafica#LGBT#LGBTQ#Lorenza De Luca#Lyndall Gordon#Michelle Reviglio#Renape#Thomas Govoni

1 note

·

View note

Text

I first heard about The Story of an African Farm (1883) by the South African writer Olive Schreiner in Vera Brittain’s memoir of the Great War, Testament of Youth. She and her fiancé, Roland Leighton were intensely interested in it, but its contents weren’t discussed, so I was curious to read it. Olive Schreiner wrote this debut novel when she was only in her 20s. The Story of an African Farm is set on an isolated farm in the South African veld. It is a coming of age story of the three children who live there, the two girls Em and Lyndall and Waldo, the farm manager’s son. Schreiner’s views are told mostly through Waldo and Lyndall as we follow their development and difficult quests. The novel is unconventional. Besides the traditional narrative sections it has the unusual features of an exposition (Times and Seasons) and an allegory as well as a lengthy letter. She describes Waldo’s spiritual journey from unquestioned religious belief to skepticism and apostasy and the replacement of the religious void with knowledge and an appreciation for the beauty and order of Nature. Olive Schreiner was raised by devout Christian missionaries but lost her religious faith after the death of her beloved 17 month old sister Ellie. Schreiner also raises the issue of gender inequality through Lyndall: the limitations on women’s education and their subservient roles in society, and she describes Lyndall’s desperate struggle for autonomy. I wasn’t surprised to learn that Olive Schreiner loved George Eliot‘s the Mill on the Floss and that she identified with Maggie Tulliver. Her views were quite progressive and controversial for her time, and the book was met with both wide appeal and opposition. I can imagine how it must have resonated with Vera Brittain’s own agnosticism and feminism. It’s a philosophical work that courageously challenges both the form of the Victorian novel and restrictive Victorian social conventions.

Memorable excerpts (among many):

“We must have awakened sooner or later. The imagination cannot always triumph over reality, the desire over truth…Now we have no God. We have had two: The old God that our fathers handed down to us, that we hated, and never liked; the new one that we made for ourselves, that we loved; but now he has flitted away from us, and we see what he was made of – the shadow of our highest ideal, crowned and enthroned.”

“But we, wretched unbelievers, we bear our own burdens; we must say, I myself did it, I. Not God, not Satan; I myself!”

I came across a reference to Olive Schreiner in a review of Lyndall Gordon’s biographical work, Outsiders: Five Women Writers Who Changed the World. I haven’t read it, but it sounded interesting, and I have provided the link:

The edition I read is from the Limited Editions Club. The cover material is Ugandan bark cloth, Isak Dinesen provides the introduction, and it is illustrated by Paul Hogarth. I have also seen editions from Oxford World’s Classics, Penguin, Virago, and Modern Library.

Memorable excerpts :

It is a terrible, hateful ending, said the little teller of the story, leaning forward on her folded arms; and the worst is, it is true. I have noticed, added the child very deliberately, that it is only the made up stories that end nicely; the true ones all end so.

They did not understand the discourse (the charlatan’s false sermon), which made it the more affecting. There hung over it that inscrutable charm which hovers for ever for the human intellect over the incomprehensible and shadowy.

To the old German the story it was no story. Its events were as real and as important to himself as the matters of his own life. He could not go away without knowing whether the wicked Earl relented, and whether the Baron married Emelina.

Times and Seasons is a very important chapter that outlines the course of one’s experiences with religious faith (if one is willing to think for oneself): belief, questioning, skepticism, disbelief, and finally the replacement of religion with knowledge and an appreciation of the beauty and order of Nature. Some excerpts from this chapter follow:

Is it good of God to make hell? Was it kind of Him to let no one be forgiven unless Jesus Christ died?

Is it right there should be a chosen people? To Him, who is father to all, should not all be dear?

We must have awakened sooner or later. The imagination cannot always triumph over reality, the desire over truth…Now we have no God. We have had two: The old God that our fathers handed down to us, that we hated, and never liked; the new one that we made for ourselves, that we loved; but now he has flitted away from us, and we see what he was made of – the shadow of our highest ideal, crowned and enthroned. Now we have no God...

We do not cry and weep; we sit down with cold eyes and look at the world. We are not miserable. Why should we be? We eat and drink, and sleep all night; but the dead are not colder.

And we add, growing a little colder yet, ‘There is no justice. The ox dies in the yoke beneath its master’s whip; it turns its anguish-filled eyes on the sunlight, but there is no sign of recompense to be made it. The black man is shot like a dog, and it goes well with the shooter. The innocent are accused, and the accuser triumphs. If you will take the trouble to scratch the surface anywhere, you will see under the skin a sentient being writhing in impotent anguish.’ And we say further, and our heart is as the heart of the dead for coldness, ‘There is no order’: all things are driven about by a blind chance.’. p117

What a soul drinks in with its mothers milk will not leave it in a day. From earliest hour we have been taught that the thought of the heart, the shaping of the rain-cloud, the amount of wool that grows on a sheep‘s back, the length of a drought, and the growing of the corn depend on nothing that moves immutable, at the heart of all things; but on the changeable will of a changeable being, whom our prayers can alter. To us, from the beginning, nature has been but a poor plastic thing, to be toyed with this way or that, as man happens to please his deity or not; to go to church or not; to say his prayers right or not; to travel on a Sunday or not. Was it possible for us in an instant to see Nature as she is – the flowing vestment of unchanging reality? When a soul breaks free from the arms of a superstition, bits of the claws and talons break themselves off in him. It is not the work of a day to squeeze them out...

Whether a man believes in a human-like God or no is a small thing. Whether he looks into the mental and physical world and sees no relation between cause and effect, no order, but a blind chance sporting, this is the mightiest fact that can be recorded in any spiritual existence. p118

Following this, the appreciation of the acquisition of knowledge and Nature’s own beauty and order fills the void of religion. pp119-121

We have never once been taught by word or act to distinguish between religion and the moral laws on which it has artfully fastened its self, and from which it has sucked it’s vitality.

But we, wretched unbelievers, we bear our own burdens; we must say, I myself did it, I. Not God, not Satan; I myself!

The secret of success is concentration; wherever there has been a great life, or a great work, that has gone before. Taste everything a little, look at everything a little; but live for one thing. Anything is possible to a man who knows his end and moves straight for it, and for it alone.

2 notes

·

View notes

Quote

It was her religion to make the best of everything.

Lyndall Gordon

#lyndall gordon#lit#quotes#prose#words#inspiration#motivation#positive#life#inspirational#motivational#life quotes#wordsnquotes#feelings#emotions#wisdom#truth

944 notes

·

View notes

Text

It was her religion to make the best of everything.

Lyndall Gordon, Vindication: A Life of Mary Wollstonecraft

3 notes

·

View notes

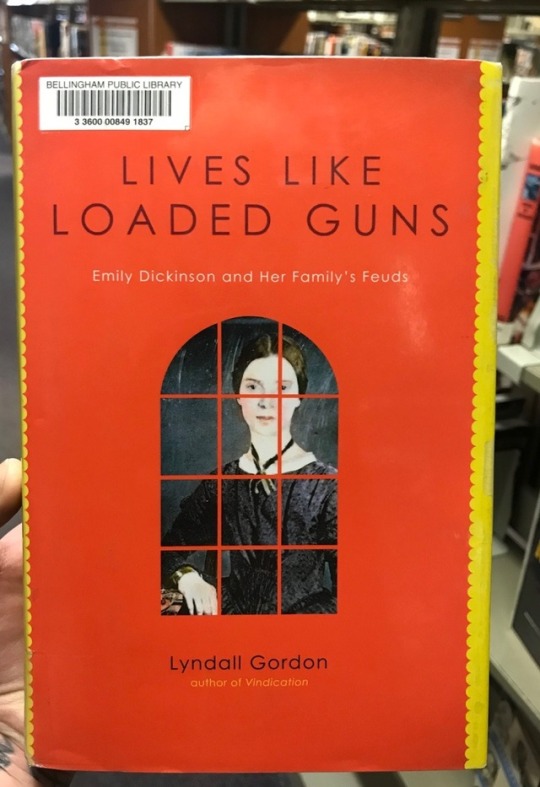

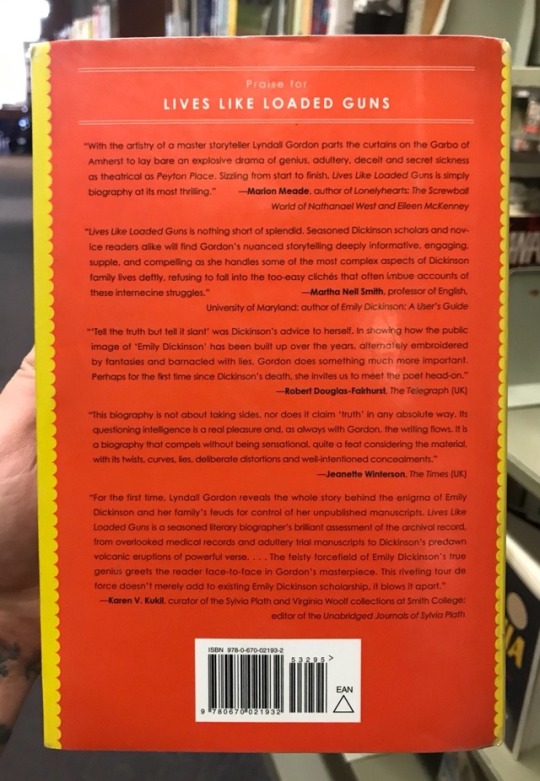

Photo

Lives Like Loaded Guns

Lyndall Gordon

Call #: 811.4 Gordon 2010

ISBN 978-0-670-02193-2

”In 1882, Emily Dickinson's brother, Austin, began an adulterous love affair with the accomplished and ravishing Mabel Todd, setting in motion a series of events that would forever change the lives of the Dickinson family. Award-winning biographer Lyndall Gordon tells the story of the feud that erupted-and that still continues today. Making unprecedented use of letters, diaries, and legal documents, Gordon proposes a groundbreaking new solution to the secret behind the poet's insistent seclusion, presenting a woman beyond her time who found love, spirituality, and immortality all on her own terms.

The first major biography of Dickinson in nearly ten years, Lives Like Loaded Guns is a highly acclaimed story of creative genius, illicit passion, and betrayal that will forever change the way we view one of America's most important literary figures.”

#liveslikeloadedguns#lives like loaded guns#emilydickinson#emily dickinson#lyndallgordon#lyndall gordon#mabeltodd#mabel todd#literary icon#author#female author#femaleauthor#book#books

0 notes

Text

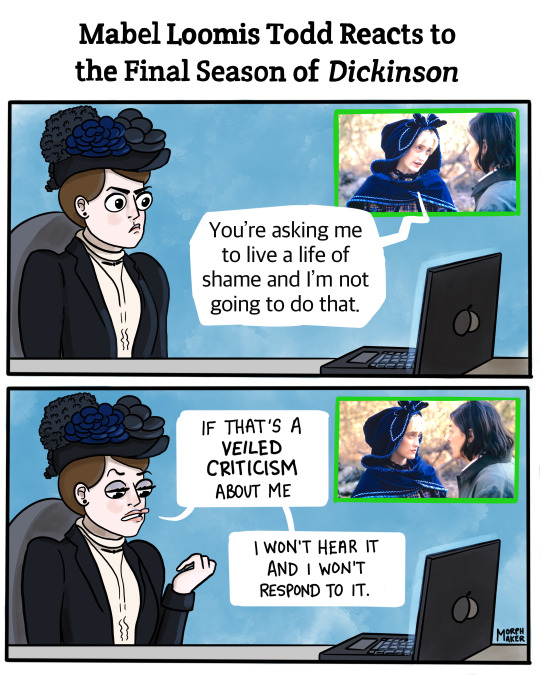

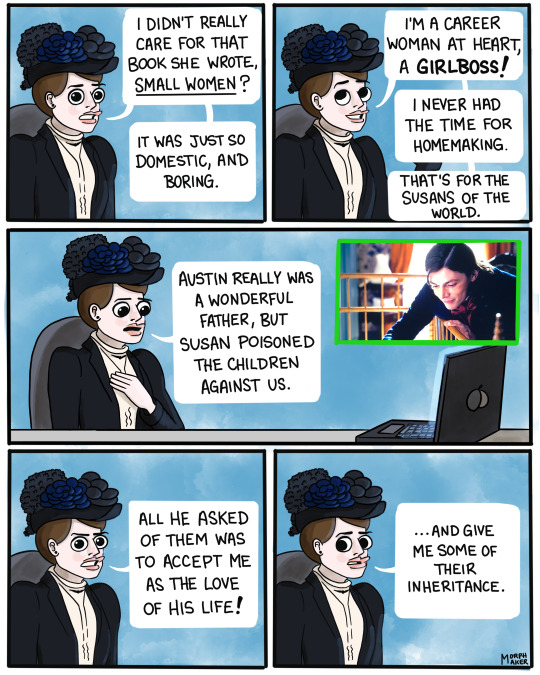

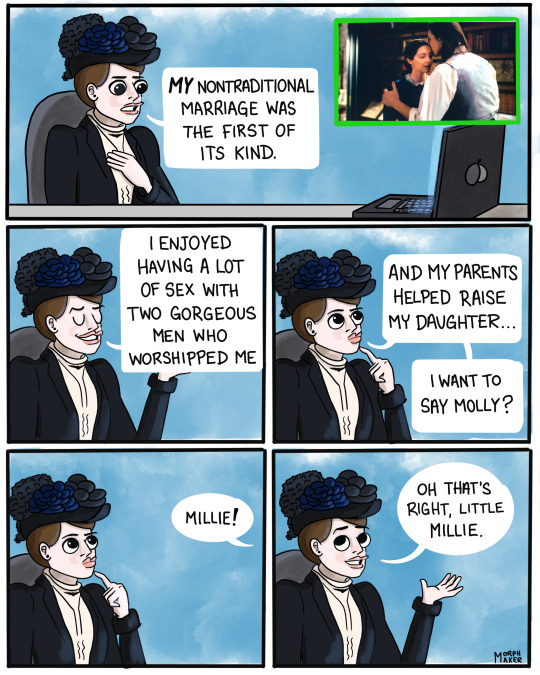

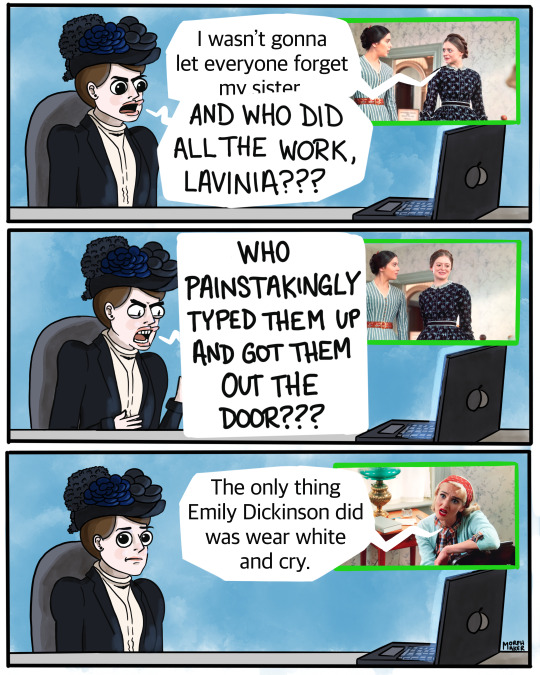

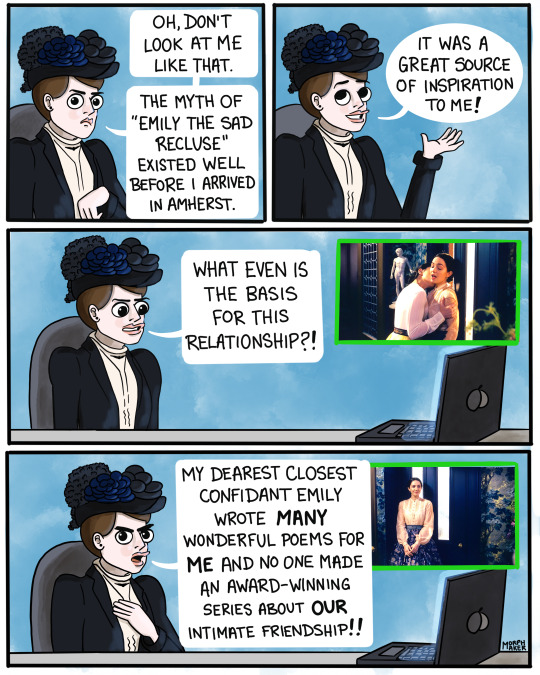

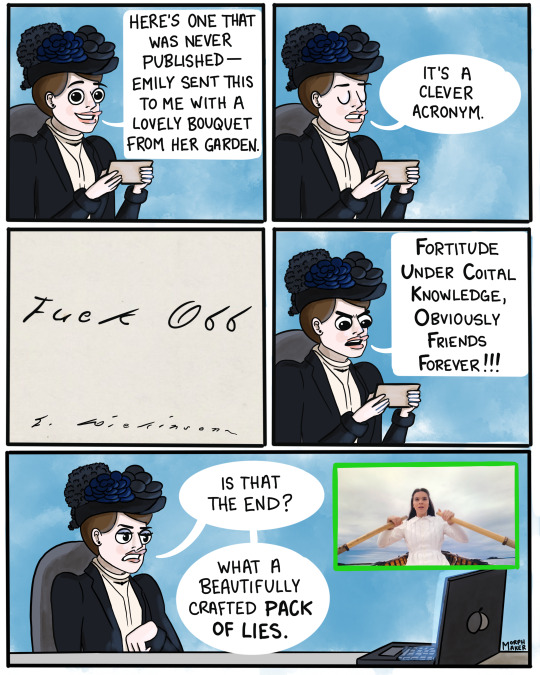

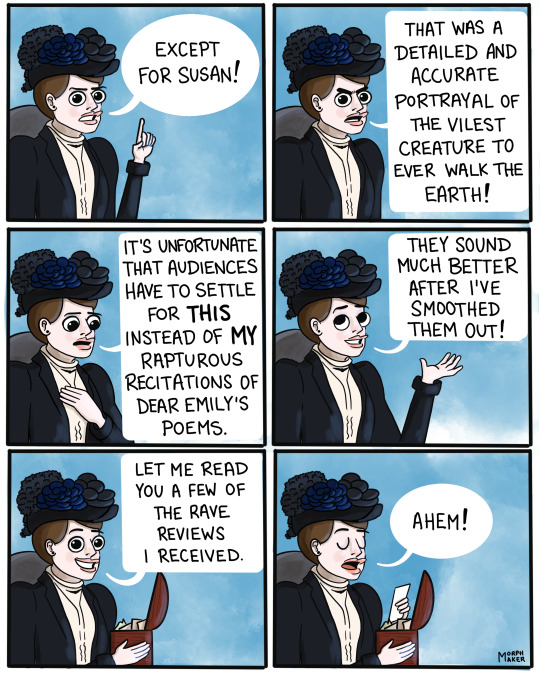

"A beautifully crafted pack of lies." – Mabel Loomis Todd Reacts to the Final Season of Dickinson

Previously: Mabel Loomis Todd Reacts to Two Seasons of Dickinson

Sources: Lives Like Loaded Guns by Lyndall Gordon, Austin and Mabel: The Amherst Affair and Love Letters of Austin Dickinson and Mabel Loomis Todd by Polly Longsworth, White Heat: The Friendship of Emily Dickinson and Thomas Wentworth Higginson by Brenda Wineapple, emilydickinson.org, Open Me Carefully by Martha Nell Smith and Ellen Louise Hart, Wild Nights with Emily movie, my own imagination

#dickinson#emily dickinson#lavinia dickinson#susan gilbert#austin dickinson#mabel loomis todd#susan dickinson#jane humphrey#Louisa May Alcott#thomas wentworth higginson#sylvia plath#morphmaker arts

61 notes

·

View notes