#jockeys

Text

Avel de Knight (American, 1923-1995), Untitled. Gouache on paper, 23⅝ × 13 in.

179 notes

·

View notes

Text

Daydreaming in Jockey Y Fronts.

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

This guy is his own worst enemy. 😂😈

#fully exposed and ruined#public embarrassment#petticoat humiliation#depantsed#white briefs#beta sissy#beta sub#jockeys#loser humiliation#pathetic loser#sissy loser

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

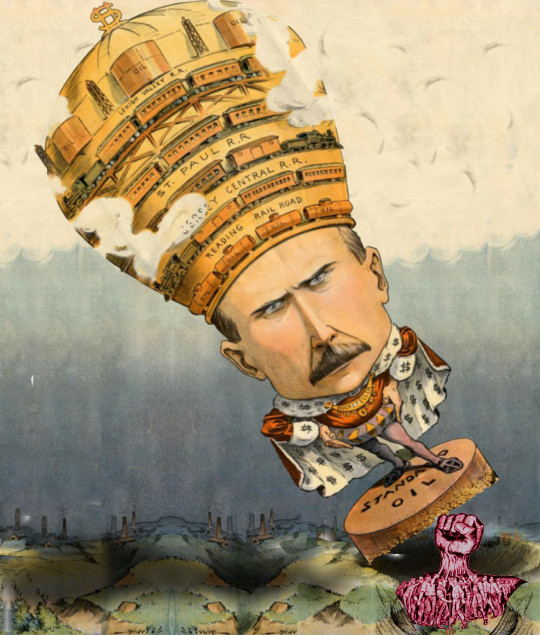

Is antitrust anti-labor?

If you find the word “antitrust” has a dusty, old-fashioned feel, that’s only to be expected — after all, the word has its origins in the late 19th century, when the first billionaire was created: John D Rockefeller, who formed a “trust” with his oil industry competitors, through which they all agreed to stop competing with one another so they could concentrate on extracting more from their workers and their customers.

If you’d like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here’s a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/04/14/aiming-at-dollars/#not-men

Trusts were an incredibly successful business structure. A bunch of competing companies would be sold to a new holding company (“the trust”), and the owners of those old standalone companies would get stock in this new trust. The trust would operate as a single entity, hiking prices and suppressing wages. If anyone tried fight the trust with a new, independent company, the trust could freeze them out, by selling goods below cost, or by doing exclusive deals with key suppliers and customers, or both. Once a trust sewed up an industry, no one could compete. The trust barons were rulers for life.

The first successful trust was Rockefeller’s Standard Oil, which amassed a 90% share of all US oil. Other “capitalists” got in on the game, forming the Cotton Seed Oil Trust (75% market share), the Sugar Trust (85%). Then came the Whiskey Trust and the Beef Trust. America was becoming a planned economy, run by a handful of unelected “industrialists” with lifetime appointments and the power to choose their successors.

A century after overthrowing the King, America had new kings: “kings over the production, transportation and sale of the necessities of life”. That’s how Senator John Sherman described the situation in 1890, when he was campaigning for the passage of the Sherman Act, the first “anti-trust” act. The Sherman Act wasn’t the first time American lawmakers tried to protect competition, but it was the first law passed after the failure of competition law led to the hijacking of the nation by people Sherman called the “autocrats of trade.”

https://marker.medium.com/we-should-not-endure-a-king-dfef34628153

The Sherman Act — and its successors, like the Clayton Act, are landmark laws in that they explicitly seek to protect workers and customers from corporate power. Antitrust is about making sure that no corporation gets so powerful that it’s too big to fail, nor too big to jail — that a company can’t get so big that it subverts the political process, capturing its own regulators:

https://doctorow.medium.com/small-government-fd5870a9462e

If American workers are derided as “temporarily embarrassed millionaires” who won’t join the fight against the rich because they assume they’ll soon join their ranks, then the American rich are “temporarily embarrassed aristocrats” who would welcome hereditary rule, provided they got to found one of the noble families. The goal of the American elite has always been to create a vast and durable dynasty, wealth so vast and well-insulated that even the most Habsburg-jawed failson can’t piss it away.

The American elite has always hated antitrust. In the 1980s, Ronald Reagan, abetted by Robert Bork and his co-conspirators at the Chicago School of Economics gutted antitrust through something called the “consumer welfare standard,” which ended anti-monopoly enforcement except in instances where price hikes could be directly and unarguably attributed to market power, which is, basically, never.

It’s been 40 years since Reagan took antitrust out behind the Lincoln Monument and shot it in the guts, and America has turned into the kind of aristocratic kleptocracy that Sherman railed against, where “great families” control the nation’s wealth and politics and even its Supreme Court judges:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/04/06/clarence-thomas/#harlan-crow

Anything that can’t go on forever will eventually stop. Monopoly threatens the living standards, health, freedom and prosperity of nearly every person in America. The undeniable enshittification of the country by its guillotine-ready finance ghouls, tech bros and pharma profiteers has led to a resurgence in antitrust, and a complete renewal of the @FTC and @JusticeATR:

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2021/08/party-its-1979-og-antitrust-back-baby

Key to the new and vibrant FTC is Commissioner Alvaro Bedoya, who, along with Commissioner Rebecca SlaughterFTC and Chairwoman Lina Khan, is part of the Democratic majority on the Commission. Bedoya has a background in tech and privacy and civil rights, and is a longtime advocate against predatory finance. He’s also a law professor and a sprightly scholarly writer.

Earlier this week, Bedoya gave a prepared speech for the Utah Project on Antitrust and Consumer Protection conference, entitled “Aiming at Dollars, Not Men.” It’s a banger:

https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/ftc_gov/pdf/bedoya-aiming-dollars-not-men.pdf

Criticisms of the new antitrust don’t just come from America’s oligarchs — the labor movement is skeptical of antitrust as well, and with good cause. Antitrust law prohibits collusion among businesses to raise prices, and at many junctures since the passage of the Sherman Act, judges have willfully perverted antitrust to punish labor organizers, treating workers demanding better working conditions as if they were Rockefeller and his cronies conspiring to raise prices.

This is the subject of Bedoya’s speech, whose transcript is painstakingly footnoted, and whose text makes it crystal clear that this is not what antitrust is for, and we should not tolerate its perversion in service to crushing worker power. The title comes from a 1914 remark by Democratic Congressman Thomas Konop, who said, of antitrust: “We are aiming at the gigantic trusts and combinations of capital and not at

associations of men for the betterment of their condition. We are aiming at the dollars and not at men.”

Konop was arguing for the passage of the Clayton Act, a successor to the Sherman Act, which was passed in part because judges refused to enforce the Sherman Act according to its plain language and its legislative intent, and kept using it against workers. In 1892, two years after the Sherman Act’s passage, it was used to crush the New Orleans General Strike, an interracial uprising against labor exploitation from longshoremen to printers to carpenters to hearse drivers.

Bosses went to a federal judge asking for an injunction against the strike. Though the judge admitted that the Sherman Act was designed to fight “the evils of massed capital,” he still issued the injunction.

The Sherman Act was used to clobber the Pullman Porters union, which organized Black workers who served on the Pullman cars on America’s railroads. The workers struck in 1894, after a 25% wage-cut, and they complained that they could no longer afford to eat and feed their families, so George Pullman fired them all. The workers struck, led by Eugene Debs. Pullman argued that the strike violated the Sherman Act. The Supreme Court voted 9:0 for Pullman, ordered the strike called off, and put Debs in prison.

In 1902, mercury-sickened hatters in Danbury, CT demanded better working conditions — after just a few years on the job, hatters would be disabled for life with mercury poisoning, with such bad tremors they couldn’t even feed themselves. 250 hatters at the DE Loewe company tried to unionize. Loewe sued them under the Sherman Act, and went to the Supreme Court, who awarded Loewe $6.8m in today’s money, which allowed Loewe to seize his former workers’ homes.

This is what sent Congress back to the drawing board to pass the Clayton Act. Though the Sherman Act was clear that it was about trustbusting, the courts kept interpreting it as a charter for union-busting. The Clayton Act explicitly permits workers to form unions, call for boycotts, and to organize sympathy strikes.

They made all this abundantly clear: writing in language so plain that judges had to understand the legislative intent. And yet…judges still managed to misread the Clayton Act, using it to block 2,100 strikes in the 1920s. It appears that passing the Clayton Act did not save a single strike that would have been killed by the bad (and bad faith) Sherman Act precedents that led to the Clayton Act in the first place.

The extent to which greedy bosses used the Clayton Act to attack their workers is genuinely ghastly. Bedoya describes one coal strike, against the Red Jacket Coal Company of Mingo, WV. The mine’s profits had grown by 600%, but workers’ wages weren’t keeping up with inflation. The miners sought a raise of $0.10 on the $0.66 they got paid for ever carload of coal they mined. The company didn’t even pay the workers with real money — just “company scrip”: coupons that could only be spent at the company store. Red Jacket gave its workers a $0.09/car raise — and raised prices at the company store by $0.25/item.

The workers struck, Red Jacket sued. The Fourth Circuit refused to apply the Clayton Act, following a precedent from a case called Duplex Printing that held that the Clayton Act only applied to people who stood “in the proximate relation of employer and employee.”

Congress was pissed. They passed the Norris-LaGuardia Act of 1932, with LaGuardia spitting about judges who “willfully disobeyed the law…emasculating it, taking out the meaning intended by Congress, making the law absolutely destructive of Congress’s intent.” Norris-LaGuardia creates an antitrust exemption for labor that applies “regardless of whether the disputants stand in the proximate relation of employer and employee.” So, basically: “CONGRESS TO JUDGES, GET BENT.”

And yet, judges still found ways to use antitrust as a cudgel to beat up workers. In Columbia River Packers, the court held that fishermen weren’t protected by the exemption for workers, because they were selling “commodities” (e.g. fish) not their labor. Presumably, the fish just leapt into the boats without anyone doing any work.

The willingness of enforcers to misread antitrust continued down through the ages. In 1999, the FTC destroyed the hopes of the some of the country’s most abused workers: “independent” port truckers, who worked 80 hours/week and still couldn’t pay the bills. Truckers were only paid to move trailers around the ports, but they were required to do hours and hours of unpaid work — loading containers, hauling equipment for repair, all for free. The truckers tried to organize a union — and the FTC subpoenaed the organizers for an investigation of price-fixing.

But the problem wasn’t with the laws. It was with judges who set precedents that — as LaGuardia said, “willfully disobeyed the law…emasculating it, taking out the meaning intended by Congress, making the law absolutely destructive of Congress’s intent.”

Congress passed laws to strengthen workers and judges — temporarily embarrassed aristocrats — simply acted as if the law was intended to smash workers. But by 2016, judges had it figured out. That’s when jockeys at the Camarero racetrack in Canóvana, Puerto Rico went on strike, demanding pay parity with their mainland peers — Puerto Rican jockeys got $20 to risk their lives riding, a fifth of what riders on the mainland received.

Predictably, the horse owners and racetrack sued. The jockeys lost in the lower court, and the court ordered the jockeys to pay the owners and the track a million dollars. They even sued the jockeys’ spouses, so that they could go after their paychecks to get that million bucks.

The case went to the First Circuit appeals court and Judge Sandra Lynch said: you know what, it doesn’t matter if the jockeys are employers or contractors. It doesn’t matter if they sell a commodity or their labor. The jockeys have the right to strike, period. That’s what the Clayton Act says. She overturned the lower court and threw out the fines.

As Bedoya says, antitrust is “law written to rein in the oil trust, the sugar trust, the beef trust…the gigantic trusts and combinations of capital…dollars and not at men.” Congress made that plain, “not once, not twice, but three times, each time in a louder and clearer

voice.”

Bedoya, part of the FTC’s Democratic majority, finishes: “Congress has made it clear that worker organizing and collective bargaining are not violations of the antitrust laws. When I vote, when I consider investigations and policy matters, that history will guide me.”

There's only three days left in the Kickstarter campaign for the audiobook of my next novel, a post-cyberpunk anti-finance finance thriller about Silicon Valley scams called Red Team Blues. Amazon's Audible refuses to carry my audiobooks because they're DRM free, but crowdfunding makes them possible.

#pluralistic#jockeys#antitrust#labor#history#judicial overreach#Alvaro Bedoya#consumer welfare standard#trustbusting#sherman act#new orleans general strike of 1892#pullman union#pullman porters#eugene debs#mad hatters#danbury hatters#clayton act#red jacket coal company#Fiorello LaGuardia#Norris-LaGuardia Act#duplex printing#Columbia River Packers#puerto rico#Camarero racetrack

219 notes

·

View notes

Text

138 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Credit: Chris Bair

#tack#western#cowboy#horseback riding#farm#barn#rustic#rural#countryside#horse saddle#saddle#horse#equine#equestrian#dressage#rodeo#agriculture#stables#jockeys#horse show#ranch#rancher

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Edgar Degas

Three Jockeys

ca. 1900

#edgar degas#impressionist#french impressionist#impressionism#french impressionism#impressionist painter#french artist#french art#french painting#french painter#jockeys#horse racing#horses#equestrian#beautiful horse#beautiful animals#aesthetic#art history#aesthetictumblr#tumblraesthetic#tumblrpic#tumblrpictures#tumblr art#tumblrstyle#artists on tumblr

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

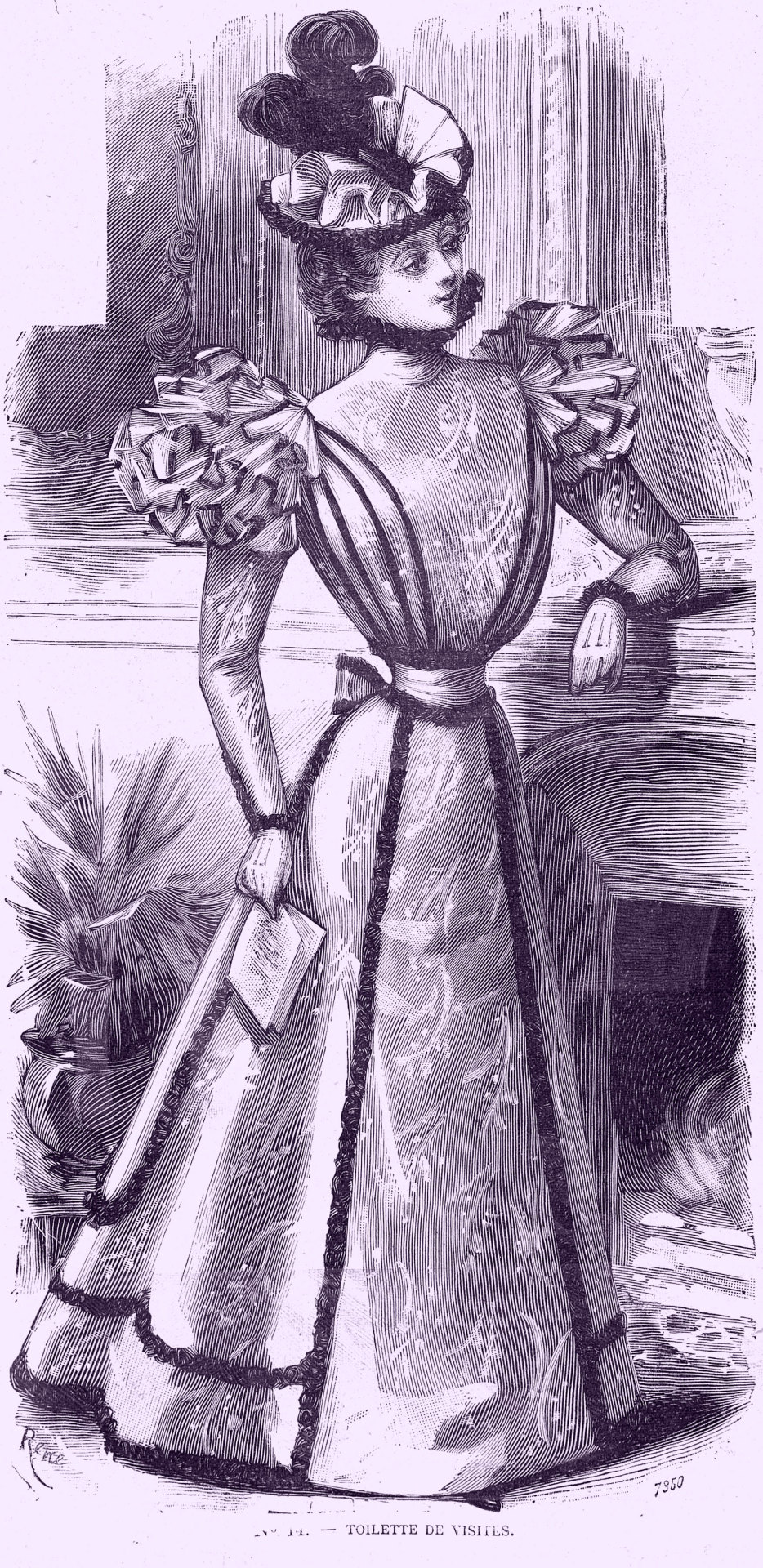

La Mode nationale, no. 12, 27 mars 1897, Paris. No. 14. — Toilette de visites. Bibliothèque nationale de France

Explications des gravures:

No. 14. — Toilette de visites en soie brochée sur chaine, impressions multicolores sur fond gris. Corsage plat avec quatre petits velours noirs posés en bretelles sur les côtés; ruche noire autour du cou; manches plates, surmontées par quatre petits volants faisant jockeys sur les épaules. Jupe plate, plissée derrière, sur ceinture drapée, garni tout autour et en tablier par une ruche bouillonnée en satin noir. Chapeau canotier en paille blanche, garni en dessus par une draperie plissée vert futaie, petite ruche en satin noir autour, et deux grandes plumes d'autruche en aigrettes sur le dessus.

No. 14. — Visitor's ensemble in brocaded silk on warp, multicolored prints on a gray background. Flat bodice with four small black velvets posed as straps on the sides; black ruffle around the neck; flat sleeves, surmounted by four small flounces forming jockeys on the shoulders. Flat skirt, pleated at the back, on a draped waistband, trimmed all around and in the apron by a bubbled ruffle in black satin. Boater hat in white straw, trimmed above with a pleated drapery in forest green, small black satin ruffle around it, and two large ostrich feathers in aigrettes on the top.

#La Mode nationale#19th century#1800s#1890s#1897#periodical#fashion#fashion plate#retouch#description#Bibliothèque nationale de France#dress#toilette#ensemble#visiting#silk#warp#jockeys#collar#print#boater

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Michelle Payne

Michelle Payne was born in 1985 in Victoria, Australia. In 2015, Payne became the first woman to win the Melbourne Cup, Australia's most famous horse race. She won her first race in 2001, and has won over 700 more since. In 2021, Payne was awarded an Order of Australia medal.

Image source

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jockeys, by Edgar Degas, 1881. From edgar-degas.net (source)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

So you want to be a jump jockey?

Dramatic spills, like this one in 2022, are not uncommon at the Grand National.

Credit - Peter Powell/EPA, via Shutterstock

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“The Steeplechase”

digital collage & digital painting by Mick Mather

(click image to view full size)

#Mick Mather#digital art#digital collage#digital painting#'found' images#digital manipulation#race horses#jockeys#MickMathersARTblog

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

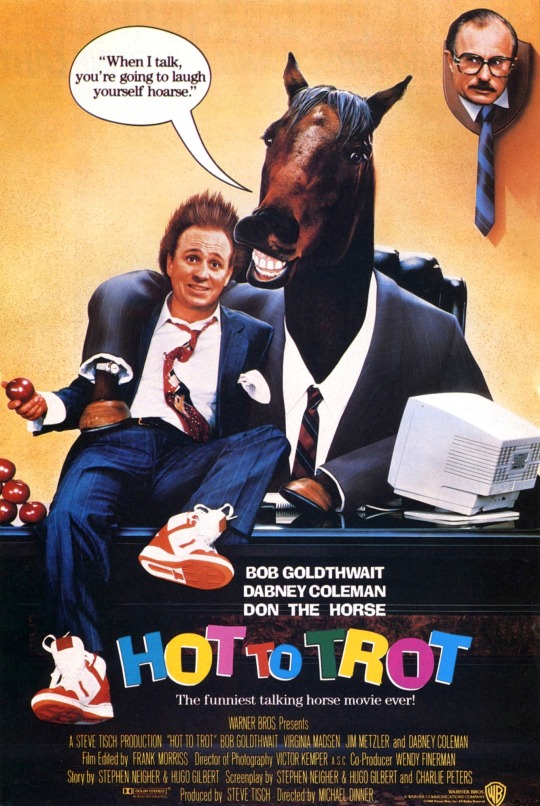

Hot to Trot (1988, Michael Dinner)

1/5/23

#Hot to Trot#Bobcat Goldthwait#Dabney Coleman#John Candy#Virginia Madsen#Cindy Pickett#Jim Metzler#Tim Kazurinsky#Mary Gross#Lonny Price#80s#comedy#horses#talking animals#stock market#yuppies#inheritance#interspecies#jockeys#horse racing#rags to riches#dreadful#unfunny#animal cruelty

3 notes

·

View notes