#if you like historical fiction or characters deeply in love but with difficult histories between them. read this book. right now

Text

Vampires of El Norte by Isabel Cañas

Nine years divided them, but time meant nothing to hands: her fingers interlaced with his as naturally as if they were eight years old, or ten, or thirteen. Palm to palm, thumb over thumb. A bridge between them.

#vampires of el norte#isabel canas#litedit#new adult books#historical fiction#romance novels#bookedit#my edit#this is one of my favorite books i read last year#like in the top 3. stellar writing. incredible characters with flaws and so much tension#i adore how the setting/time period was written with the fantasical elements of magic/vampires#if you like historical fiction or characters deeply in love but with difficult histories between them. read this book. right now

29 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello, I am a huge fan of your work and I’ve been following you for a while!

I am a gay Greek student at the History & Mythology department from Aristotle University. I had to do a lot of research and homework regarding certain subjects and one of them was Κρόκος (Krokos/Crocus). Crocus was in fact in love with a nymph named Smilax, but was never, in any valid story, involved with Hermes romantically. Contrary to popular belief, homosexuality was something that was condemned in the majority of most city-states of ancient Greece, especially Athens. In fact, they even had the derogatory term for gay people “kinaidos” (κίναιδος) and they were banned from participating in politics, banned from the Olympics, banned from participating in the war, banned from being priests and in worse cases, they were sentenced to death. :(

“Αν τις Αθηναίος εταιρήση, με έξεστω αυτω των εννέα αρχόντων γενέσθαι, μηδέ ιερωσύνην ιερώσασθαι, μηδέ συνδικήσαι τω δήμω, μηδέ αρχήν αρχέτω μηδεμιάν, μήτε ενδημον, μήτε υπερόριον, μήτε κληρωτήν, μήτε χειροτονητήν, μηδέ επικυρήκειαν αποστελλέσθω, μηδέ γνώμην λεγέτω, μηδέ εις τα δημοτελή ιερά εισίτω, μηδέ εν ταις κοιναίς σταφονοφορίες σταφανούσθω, μηδέ εντός των της αγοράς περιρραντηριων πορευέσθω.

Εάν δε ταύτα τις ποιή,καταγνωσθέντως αυτού εταιρείν, θανάτω ζημιούσθω.”

Translation:

“If an Athenean performs this, he will not be allowed to become member of the 9 lords, he will not be able to become a priest, he will not be able to become an advocate of the people, he will have no authority inside or outside of Athens, he cannot become a war preacher, he will not be able to express his opinion, he will not be allowed to enter the sacred public temples, he will not be able to take walks happening in Agora. If he ignores any of these laws he will be sentenced to death.”

- Solon Laws in book 5, chapter 5

Also, the term “Pederastry” actually meant “Mentoship” and it had nothing to do with sexual relationship between a male teacher and a male student.

Many of the homosexual depictions regarding historical and mythological figures are created in modern times without any evidence to back it up. For instance, Achilles and Patroclus are often assumed to be lovers in modern media when in all actuality they were just cousins. Patroclus’ father Μενοίτιος (Menoetius) and Achilles’ father Πηλέας (Peleus) were brothers.

Alexander the Great was never in a relationship with his best friend Hephaestion as there’s no evidence to back it up besides him telling him his secrets and mourning his death.

The only historical figure that could be a legit bisexual was Sappho from the island Lesbos (which is why Greece now calls the island “Mytelene” to avoid any association with lesbians, despite it being the name of one of the cities there). She was accused of being a promiscuous woman who was sleeping with many men and that she was a woman-lover due to her poems, but this is still up to debate to this day.

The worst of all is that most pictures involving homosexual activity used as evidence to prove queerness have been modern remakes of an ancient artifacts depicting heterosexuality (or even the rape of women). Eros Kalos is responsible for many of these “queer copies”.

This deeply saddens me as I am a homosexual myself, but I don’t think Ancient Greece deserves credit for being “open-minded” on the subject knowing that they would treat me badly if I was born in my country in that era. I don’t feel comfortable with people trying to prove that it was gay when that’s not true at all. Anyway, I am very happy that artists like you exist and make their own fictional versions of the characters in ways that feel comfortable for us to look at. Stay amazing. <3

Wow, this was a super interesting read !!! Thanks for all the helpful info :3 It's sometimes difficult to discern what "love" between gods and mortals means in the translated texts, as sometimes it can mean romantic/sexual love, and other times it just means godly love, i.e. mortals who were "chosen" by gods to be their patrons (so just having a very strong spiritual connection in the same way the Christian God "loves his children") and I feel like sometimes those two things become conflated a lot in discussion around those stories, but that's why it's always important to listen to other interpretations and translations to try and get the most accurate recounting possible.

Mind you, I am not Greek so take ALL of my opinions on this topic with OLYMPUS-SIZED-MOUNTAINS OF SALT LOL

I actually had no idea about the Alexander the Great x Hephaestion thing, and upon searching it up, it brought up articles about a Netflix production? Would I be wrong in assuming that's what motivated you to clarify on that ? 😆 (or is it just a common sentiment these days? genuinely asking haha I'm not so sharp on my Alexander the Great lore these days 😔🤡)

I absolutely agree that Greece itself isn't exactly a pillar of LGBTQ+ representation or rights (it is, after all, predominantly Orthodox Christian and they just legalized gay marriage in this, the year of our suffering 2024) and it's important not to put on blinders or use our connection to the gods and myths to erase what's going on historically. It's certainly not a magical imperfect wonderland - no culture or country is - and the more people are aware of that, the more they can become aware of ongoing issues and fight for things like equal rights (as they should!) so they can move towards positive change.

I think there's definitely lots to be said about the fandomification of Greek myth as well, where a lot of people take fun in the cute / funny / easy-to-headcanon parts of the myths without recognizing where they come from, why they were written, and who they were written for. It's easy to be a non-Greek person consuming and engaging with all the fun parts of the myths, because we get the privilege of being outsiders looking in who can interpret the myths in our own way free of consequences or the reality of the culture these myths are from. And I say that as someone who's not Greek and absolutely falls into that camp! Some of us use that privilege responsibly, others... not so much. And again, that's something that can happen with any culture (though I can definitely name a handful that have become notorious for how fandomified they've become through pop culture cough Japan cough Korea cough Canada, yes I fucking said Canada-)

That said, as with any culture that becomes more popularized with people outside of it, as much as that can lead to harm and misrepresentation in many ways, it can also lead to a lot of joy and appreciation. I'm glad that so many people have found themselves in the myths and find their hope through them and reclaim their power through them even if they've had a messy history. I see this sort of reclamation thriving in Christian mythology as well, through those who want to reclaim the beauty of many of its stories and messages and express the joy and love and compassion in them, rather than using them for hate and discrimination as they're so commonly and systematically used. In that way I think you can easily have adaptions that aren't historically accurate, but are more reflective of the culture and hopes and dreams of the people who are retelling them in the modern day. I think it's important to keep both in mind.

IMO it's one of those "if we don't find joy in it and use it to spread love to others, that means the bigots get to use it for harm" type things, if that makes sense :'0 But that doesn't mean we should pretend like history never happened, because in doing so, we're doomed to repeat it. We should always do our best to respect where these stories came from, and do more to learn about them when we get the opportunity to do so, because not doing so is how we end up with adaptions and "retellings" that are so far removed from the source material - but still ingrain themselves so seriously without a shred of transparency - that they almost become erasure in and of themselves. As I say a lot here, balance is key, and we should always be making efforts to learn ( ´ ∀ `)ノ~ ♡

#idk if any of this was actually worded well it's like 3 AM here lmao#ama#ask me anything#anon ama#anon ask me anything

63 notes

·

View notes

Note

i thoght the yaoi thing was joke? :(

its /hj. tbc i haaaate most yaoi the majority of it is tasteless voyeuristic erotica which isnt like an evil thing to make but still extremely bad. i think its funny and i mostly read it cos its hilarious. more thoughts under the cut

it's misrepresented and #misunderstood especially by western gay people. its not representation, it's not 'led by queer people', and the difference between 'yaoi' and 'boy's love' is marginal. it's predominantly heterosexual women who enjoy writing drawing reading two (or more..) guys fuck which is fine. yaoi vs bl is often used as both a categorical distinction (yaoi is erotica, bl isn't) and a moral one (yaoi is cringe/homophobic/bad and bl is pure/wholesome/untainted) which is like fundamentally so wrong if you know anything about the genre.

the history is really interesting. It's roots are firmly in shojou manga, as in, explicitly for young women. early works are often taboo-breaking and deal with sexual abuse, incest, etc. an early muse for the genre was bjorn andressen as tadzio in the film 'death in venice' and if you know anything about that film and andressen says A Lot. shonen ai (literally boy love) was originally a term which was pederastic in nature but became the name for the genre. to crib from the wikipedia article cos it summarises it well:

While the term shōnen-ai historically connoted ephebophilia or pederasty, beginning in the 1970s it was used to describe a new genre of shōjo manga (girls' manga) featuring romance between bishōnen (lit. "beautiful boys"), a term for androgynous or effeminate male characters. Early shōnen-ai works were inspired by European literature, the writings of Taruho Inagaki, and the Bildungsroman genre Shōnen-ai often features references to literature, history, science, and philosophy; Suzuki describes the genre as being "pedantic" and "difficult to understand", with "philosophical and abstract musings" that challenged young readers who were often only able to understand the references and deeper themes as they grew older.

Yaoi, on the other hand:

Coined in the late 1970s by manga artists Yasuko Sakata and Akiko Hatsu, yaoi is a portmanteau of yama nashi, ochi nashi, imi nashi (山[場]なし、落ちなし、意味なし), which translates to "no climax, no point, no meaning".[f] Initially used by artists as a self-deprecating and ironic euphemism, the portmanteau refers to how early yaoi works typically focused on sex to the exclusion of plot and character development; it is also a subversive reference to the classical Japanese narrative structure of introduction, development, twist, and conclusion

by the way, that [f] note is: "The acronym yamete, oshiri ga itai (やめて お尻が 痛い, "stop, my ass hurts!") is also less commonly used."

Like the term fujoshi, meaning 'rotten girl', is the same it's very silly and self-deprecating. That's so fun! I think the yaoi genre in general is a really interesting phenomena that's rooted so deeply in Japan as a culture. I think it's great that women are able to sincerely enjoy something fun, I think it's great that women were able and continue to have successful careers in writing, and I also think it's mostly bad.

A lot of modern stuff, especially the works getting pumped out of korea by genuinely evil webtoon companies, suffer from the fundamental problems with serialisation. It putters from chapter to chapter and every single one is the same as the other. A lot of Japanese bl/yaoi is in the form of short fiction, about 5-10 chapters, and again there are fundamental problems with this. they often suffer from too much crammed in AND from so little stretched thin.

I also think yes morally or 'representationally' or whatever they are like Pretty cringe. like sorry uke/seme is BAD. sexual assault is not even handled so much as it is kicked around. Women are non-existent at best and horrifically sexist at worst. Also the writing, though ofc i read (often fan-) translated works, just sucks.

You guys don't know how bad it gets. like ok example.... it's hard giving examples cos most of its just boring or bad in a lame way. okay there's this korean rom-com drama webtoon about a boss and his employee and the boss is actually an immortal snake-deity who fell in love with this guy and his employee is the reincarnation of that guy. sounds fine right? well the snake boss has two dicks. So.

#ask#Anonymous#look i know this ask is a joke but i love overexplaining stuff. i love being a nerd. im sowwy🫶

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Recs

Thank you @revewrites for the tag!!

(Okay this is actually very difficult. I read a ton of books and picking favorites is always a nightmare... These are only a sample of my tastes.)

The Castle (1926) - Surprisingly, the one Kafka book that impressed me the most is this unfinished novel. His works are integral to my tastes both as a reader and a writer and this is the one that sticks with me to this day. It also inspired one of my all-time favorite movies (Kafka by Steven Soderbergh, 1991).

Gormenghast (1950) - The second (and best) volume of a trilogy that truly blew my mind when I discovered it last year. A true work of art built like a labyrinth in which being lost is both a pleasure and an anxiety-inducing experience. Its colorful cast of characters and majestic prose are a delight.

Hadès Palace (2005) - It's very frustrating for me to talk about this book since it hasn't been translated from French (as far as I know; it's sadly not even well-known here). It's a gorgeous novel, marvelously written, full of interesting and bold ideas, clever references, and a raw beauty that shattered my heart in a million pieces from admiration alone.

The Watchmaker of Filigree Street (2015) - This book makes me genuinely happy. It does cater to some of my special interests, but even beyond that, the story itself and the characters are lovely and comforting in a way I wouldn't have suspected. Its sequel, The Lost Future of Pepperharrow, is equally beautiful.

The Piano Tuner (2002) - It's about music and love and the spaces in-between. This novel touched me deeply on a personal level, and although I read it only last year, I feel like I've known it forever.

Seven Pillars of Wisdom (1926) - A bit of a legend, this one. It's the book that inspired the movie Lawrence of Arabia. While not as engaging as the movie itself, it's a rather fascinating plunge into WWI and a side of it that tends to be overlooked. It's not an easy read, and it's a partial account of historical facts, but nonetheless a book that's worth exploring.

The Devil in the White City (2003) - An interesting mix between non-fiction and novelization about the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition. I have countless history books that I could recommend, but this one might be the most engaging, not being strictly academic.

The Magic Mountain (1924) - A mammoth of a book if I ever read one. I remember it took me a whole month to read it. I was 19 and it was wintertime, and my brain kept thinking about it as I studied religious iconography and architecture and history, and I thought; this book is about all of it.

The Hound of the Baskervilles (1902) - Although an avid detective stories reader since I've been around nine, I came to Sherlock Holmes rather late. It defied my expectations pleasantly and this novel is my favorite of the bunch.

Tagging friends @a-simple-kazoo @dreamyonahill @rapturezoo and anyone who wants to give this a shot!

#tag game#book recommendations#literature#favorite books#reading#no pressure if y'all don't want to do it#but i'd be curious to find out more about your tastes!

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nineteen Eighties Chanel Gilt Belt

We love what we do and we are deeply passionate about it. Our enterprise was born out of a genuine love for beautiful things and the need to protect them. So that they can be enjoyed for generations to come back. Save your measurement and filter the items with just one click. https://skel.io/replica-designer-belts/chanel-belt-replica.html Selling your designer gadgets with Labellov is easy. Drop off your items in our showroom in Antwerp, visit a pop-up near you or schedule a free private pick-up at residence.

Along with pearlized hip belts, the brand additionally debuted hip chains made out of its iconic handbag straps. A single black leather-based and gold metal chain belt made for a extra understated tackle the look, whereas chunkier, layered chain belt choices went for the extra daring version. Chanel closed her style operations throughout World War II, then returned to the industry in 1954 to design for the useful needs of recent ladies. Structure and wearability endured in all of Chanel’s clothes and niknaks, just like the quilted leather-based 2.55 handbag introduced in 1955 with its gold-chain shoulder strap that freed up a woman’s palms.

Gold Chanel belts under $800 with the cc brand or “Chanel” written promote shortly. If you have a big difference in your hip and waist measurement like I do, go for an adjustable belt. I can wear mine on my hips, high waist, and anyplace in between. There are many different variations of Chanel belts, and a few are tougher to search out than others. Belts like mine are one of the more difficult kinds to search out. I knew I favored the idea of a Chanel belt, but I had no thought how a lot use I would get out of it till I started styling it.

Lagerfeld studied drawing and historical past before winning a design competition which led to a job with Pierre Balmain. He spent three years there before shifting on to Jean Patou the place he designed for their haute couture collections. After launching his personal label, he began to achieve traction, changing into identified for his provocative and sometimes shocking style.

And with fashion’s preoccupation with the ’90s, the type lexicon of our favorite fictional characters have made for seasonal tendencies that have come and gone with the seasons. The newest of the lot brings us again to a wardrobe signature of Fran Fine from The Nanny. Second solely to her infectious cackle, Fine’s maximalist style holds its own ground in tv history. From glitter to neon brights and fur, Fine’s done it all. But on the rare event that Fine dials down on her #ootd, a chain belt would hug her waist for a touch of pizzazz. wikipedia belt Chanel's chunky leather and gold waist chain introduced parts of the home's in style luggage' straps into ready-to-wear.

This belt is made with Chanel’s signature gold-tone steel interlaced with black leather with charms alongside the entrance. The belt features an adjustable hook closure and lots of types of lu... Vintage Chanel chain link fig leaf belt designed by Karl Lagerfeld. Multiple layered leather chain belt adorned with two pure gold plated fig leaves from Chanel's... This purchasing guide was written by Byrdie contributor Hayley Prokos. A seasoned commerce writer and editor, she’s constantly on the hunt for stylish and versatile equipment.

Natural distressing, if any, is characteristic to the wonder of use. It continues to be in good situation for an merchandise from a previous time. Any particular flaws shall be noted on individual listings. This merchandise is pre-owned with minor indicators of pure put on and tear. May embody but not restricted to signs of laundering/dry cleaning.

#chanel look alike belt#chanel belt women#cc belt#chanel cc belt#faux chanel chain belt#cheap chanel belt replica#chanel replica belt#knockoff cc belt#fake chanel belt

0 notes

Text

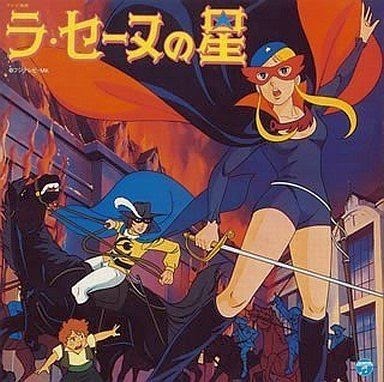

JACOBIN FICTION CONVENTION MEETING 1: La Seine no Hoshi (1975)

1. Introduction

Well, dear reader, here it is. My first ever official review. And, as promised, this is one of the pieces of Frev media that you have likely never heard of before.

So, without further ado, sit down, relax, grab drinks and snacks and allow me to tell you about an anime called “La Seine no Hoshi” (The Star of the Seine).

“La Seine no Hoshi” is a children’s anime series made by Studio Sunrise. It consists of 39 episodes and was originally broadcast in Japan from April 4th to December 26th of 1975.

Unlike its more famous contemporary, a manga called “Rose of Versailles” that had begun being released in 1972 and is considered a classic to this day, “La Seine no Hoshi” has stayed relatively obscure both in the world of anime and among other Frev pop culture.

Personally, the only reason why I found out about its existence was the fact that I actively seek out everything Frev-related and I just happened to stumble upon the title on an anime forum several years ago.

So far, the anime has been dubbed into Italian, French, German and Korean but there is no English or even Spanish dub so, unfortunately, people who do not speak fluent Japanese or any other aforementioned language are out of luck ( if anyone decides to make a fandub of the series, call me). That being said, the series is readily available in dubs and the original version on YouTube, which is where I ended up watching it. The French dub calls the anime “La Tulipe Noire” (The Black Tulip), which could be an homage to the movie with the same name that takes place in the same time period.

Unfortunately, while I do speak Japanese well enough to maintain a basic conversation and interact with people in casual daily situations, I’m far from fluent in the language so the version I watched was the French dub, seeing as I am majoring in French.

So, with all of this info in mind, let’s find out what the story is about and proceed to the actual review.

2. The Summary

(Note: Names of the characters in the French dub and the original version differ so I will use names from the former since that’s what I watched)

The story of “La Seine no Hoshi” revolves around a 15-year old girl called Mathilde Pasquier - a daughter of two Parisian florists who helps her parents run their flower shop and has a generally happy life.

But things begin to change when Comte de Vaudreuil, an elderly Parisian noble to whom Mathilde delivers flowers in the second episode, takes her under his wing and starts teaching her fencing for an unknown reason and generally seems to know more about her than he lets on.

Little does Mathilde know, those fencing lessons will end up coming in handy sooner than she expected. When her parents are killed by corrupt nobles, the girl teams up with Comte de Vaudreuil’s son, François, to fight against corruption as heroes of the people, all while the revolution keeps drawing near day by day and tensions in the city are at an all time high.

This is the gist of the story, dear readers, so with that out of the way, here’s the actual review:

3. The Story

Honestly, I kind of like the plot. It has a certain charm to it, like an old swashbuckling novel, of which I’ve read a lot as a kid.

The narrative of a “hero of the common folk” has been a staple in literature for centuries so some might consider the premise to be unoriginal, but I personally like this narrative more than “champion of the rich” (Looking at you, Scarlet Pimpernel) because, historically, it really was a difficult time for commoners and when times are hard people tend to need such heroes the most.

People need hope, so it’s no surprise that Mathilde and François (who already moonlights as a folk hero, The Black Tulip) become living legends thanks to their escapades.

Interestingly enough, the series also subverts a common trope of a hero seeking revenge for the death of his family. Mathilde is deeply affected by the death of her parents but she doesn’t actively seek revenge. Instead, this tragedy makes the fight and the upcoming revolution a personal matter to her and motivates her to fight corruption because she is not the only person who ended up on its receiving end.

The pacing is generally pretty good but I do wish there were less filler episodes and more of the overarching story that’s dedicated to the secret that Comte de Vaudreuil and Mathilde’s parents seem to be hiding from her and maybe it would be better if the secret in question was revealed to the audience a bit later than episode 7 or so.

However, revealing the twist early on is still an interesting narrative choice because then the main question is not what the secret itself is but rather when and how Mathilde will find out and how she will react, not to mention how it will affect the story.

That being said, even the filler episodes do drive home the point that a hero like Mathilde is needed, that nobles are generally corrupt and that something needs to change. Plus, those episodes were still enjoyable and entertaining enough for me to keep watching, which is good because usually I don’t like filler episodes much and it’s pretty easy to make them too boring.

Unfortunately, the show is affected by the common trope of the characters not growing up but I don’t usually mind that much. It also has the cliché of heroes being unrecognizable in costumes and masks, but that’s a bit of a staple in the superhero stories even today so it’s not that bothersome.

4. The Characters

It was admittedly pretty rare for a children’s show to have characters who were fleshed out enough to seem realistic and flawed, but I think this series gives its characters more development than most shows for kids did at the time.

I especially like Mathilde as a character. Sure, at first glance she seems like a typical Nice Pretty Ordinary Girl ™️ but that was a part of the appeal for me.

I am a strong believer in that a character does not need to be a blank slate or a troubled jerk to be interesting and Mathilde is neither of the above. She is essentially an ordinary girl with her own life, family, friends, personality and dreams and, unfortunately, all of that is taken away from her when her parents are killed.

Her initial reluctance to participate in the revolution is also pretty realistic as she is still trying to live her own life in peace and she made a promise to her parents to stay safe so there’s that too.

I really like the fact that the show did not give her magic powers and that she was not immediately good at fencing. François does remark that her fencing is not bad for a beginner but in those same episodes she is clearly shown making mistakes and it takes her time to upgrade from essentially François’s assistant in the heroic shenanigans to a teammate he can rely on and sees as an equal. Heck, later there’s a moment when Mathilde saves François, which is a nice tidbit of her development.

Mathilde also doesn’t have any romantic subplots, which is really rare for a female lead.

She has a childhood friend, Florent, but the two are not close romantically and they even begin to drift apart somewhat once Florent becomes invested in the revolution. François de Vaudreuil does not qualify for a love interest either - his father does take Mathilde in and adopts her after her parents are killed so François is more of an older brother than anything else.

Now, I’m not saying that romance is necessarily a bad thing but I do think that not having them is refreshing than shoehorning a romance into a story that’s not even about it. Plus most kids don’t care that much for romance to begin with so I’d say that the show only benefits from the creative decision of not setting Mathilde up with anyone.

Another interesting narrative choice I’d like to point out is the nearly complete absence of historical characters, like the revolutionaries. They do not make an appearance at all, save for Saint-Just’s cameo in one of the last episodes and, fortunately, he doesn’t get demonized. Instead, the revolutionary ideas are represented by Florent, who even joins the Jacobin Club during the story and is the one who tries to get Mathilde to become a revolutionary. Other real people, like young Napoleon and Mozart, do appear but they are also cameo characters, which does not count.

Marie-Antoinette and Louis XVI are exceptions to the rule.

(Spoiler alert!)

Marie-Antoinette is portrayed as kind of spoiled and out of touch. Her spending habits get touched on too but she is not a malicious person at heart. She is simply flawed. She becomes especially important to the story later on when Mathilde finds out the secret that has been hidden from her for her entire life.

As it turns out, Marie- Antoinette, the same queen Mathilde hated so much, is the girl’s older half-sister and Mathilde is an illegitimate daughter of the Austrian king and an opera singer, given to a childless couple of florists to be raised in secret so that her identity can be protected.

The way Marie-Antoinette and Mathilde are related and their further interactions end up providing an interesting inner conflict for Mathilde as now she needs to reconcile this relationship with her sister and her hatred for the corruption filling Versailles.

The characters are not actively glorified or demonized for the most part and each side has a fair share of sympathetic characters but the anime doesn’t shy away from showing the dark sides of the revolution either, unlike some other shows that tackle history (*cough* Liberty’s Kids comes to mind *cough*).

All in all, pretty interesting characters and the way they develop is quite realistic too, even if they could’ve been more fleshed out in my opinion.

5. The Voice Acting

Pretty solid. No real complaints here. I’d say that the dub actors did a good job.

6. The Setting

I really like the pastel and simple color scheme of Paris and its contrast with the brighter palette of Versailles. It really drives home the contrast between these two worlds.

The character designs are pretty realistic, simple and pleasant to watch. No eyesores like neon colors and overly cutesy anime girls with giant tiddies here and that’s a big plus in my book.

7. The Conclusion

Like I said, the show is not available in English and those who are able to watch it might find it a bit cliché but, while it’s definitely not perfect. I actually quite like it for its interesting concept, fairly realistic characters and a complex view of the French Revolution. I can definitely recommend this show, if only to see what it’s all about.

Some people might find this show too childish and idealistic, but I’m not one of them.

I’m almost 21 but I still enjoy cartoons and I’m fairly idealistic because cynicism and nihilism do not equal maturity and, if not for the “silly” idealism, Frev itself wouldn’t happen so I think shows like that are necessary too, even if it’s just for escapism.

If you’re interested and want to check it out, more power to you.

Anyway, thank you for attending the first ever official meeting of the Jacobin Fiction Convention. Second meeting is coming soon so stay tuned for updates.

Have a good day, Citizens! I love you!

- Citizen Green Pixel

#review#french revolution#anime#history#television#frev media#Jacobin Fiction Convention#marie antoinette#French Revolution anime#la seine ni hoshi#la tulipe noire dessin animé#la tulipe noire

25 notes

·

View notes

Note

no ones saying you cant enjoy daniil? people like him as a character but mostly Because he’s an asshole and he’s interesting. the racism and themes of colonization in patho are so blatant

nobody said “by order of Law you are forbidden from enjoying daniil dankovsky in any capacity”, but they did say “if you like daniil dankovsky you are abnormal, problematic, and you should be ashamed of yourself”, so i’d call that an implicit discouragement at the least. not very kind.

regardless, he is a very interesting asshole and we love to make fun of him! but i do not plan to stop seeing his character in an empathetic light when appropriate to do so. we’re all terribly human.

regarding “the racism and themes of colonization in patho”, we’ve gotta have a sit-down for this one because it’s long and difficult. tl;dr here.

i’ve written myself all back and forth and in every direction trying to properly pin down the way i feel about this in a way that is both logically coherent and emotionally honest, but it’s not really working. i debated even responding at all, but i do feel like there are some things worth saying so i’m just going to write a bunch of words, pick a god, and pray it makes some modicum of sense.

the short version: pathologic 2 is a flawed masterwork which i love deeply, but its attempts to be esoteric and challenging have in some ways backfired when it comes to topical discussions such as those surrounding race, which the first game didn’t give its due diligence, and the second game attempted with incomplete success despite its best efforts.

the issue is that when you have a game that is so niche and has these “elevated themes” and draws from all this kind of academic highbrow source material -- the fandom is small, but the fandom consists of people who want to analyze, pathologize, and dissect things as much as possible. so let’s do that.

first: what exactly is racist or colonialist in pathologic? i’m legitimately asking. people at home: by what mechanism does pathologic-the-game inflict racist harm on real people? the fact that the Kin are aesthetically and linguistically inspired by the real-world Buryat people (& adjacent groups) is a potential red flag, but as far as i can tell there’s never any value judgement made about either the fictionalized Kin or the real-world Buryat. the fictional culture is esoteric to the player -- intended to be that way, in fact -- but that’s not an inherently bad thing. it’s a closed practice and they’re minding their business.

does it run the risk of being insensitive with sufficiently aggressive readings? absolutely, but i don’t think that’s racist by itself. they’re just portrayed as a society of human beings (and some magical ones, if you like) that has flaws and incongruences just as the Town does. it’s not idealizing or infantilizing these people, but by no means does it go out of its way to villainize them either. there is no malice in this depiction of the Kin.

is it the fact that characters within both pathologic 1 & 2 are racist? that the player can choose to say racist things when inhabiting those characters? no, because pathologic-the-game doesn’t endorse those things. they’re throwaway characterization lines for assholes. acknowledging that racism exists does not make a media racist. see more here.

however, i find it’s very important to take a moment and divorce the racial discussions in a game like pathologic 2 from the very specific experiences of irl western (particularly american) racism. it’s understandable for such a large chunk of the english-speaking audience to read it that way; it makes sense, but that doesn’t mean it’s correct. although it acknowledges the relevant history to some extent, on account of being set in 1915, pathologic 2 is not intended to be a commentary about race, and especially not current events, and especially especially not current events in america. it’s therefore unfair, in my opinion, to attempt to diagnose it with any concrete ideology or apply its messages to an american racial paradigm.

it definitely still deals with race, but it always, to me, seemed to come back around the exploitation of race as an ultimately arbitrary division of human beings, and the story always strove to be about human beings far more than it was ever about race. does it approach this topic perfectly? no, but it’s clearly making an effort. should we be aware of where it fails to do right by the topic? yes, definitely, but we should also be charitable in our interpretations of what the writers were actually aiming for, rather than reactionarily deeming them unacceptable and leaving it at that. do we really think the writers for pathologic 2 sat down and said “we’re going to go out of our way to be horrible racists today”? i don’t.

IPL’s writing team is a talented lot, and dybowski as lead writer has the kinds of big ideas that elevate a game to a work of art, particularly because he’s not afraid to get personal. on that front, some discussion is inescapable as pathologic 2 deals in a lot of racial and cultural strife, because it’s clearly something near to the his heart, but as i understand it was never really meant to be a narrative “about” race, at least not exclusively so, and especially not in the same sense as the issue is understood by the average American gamer. society isn't a monolith and the contexts are gonna change massively between different cultures who have had, historically, much different relationships with these concepts.

these themes are “so blatant” in pathologic 2 because clearly, on some level, IPL wanted to start a discussion. I think it’s obvious that they wanted to make the audience uncomfortable with the choices they were faced with and the characters they had to inhabit -- invoke a little ostranenie, as it were, and force an emotional breaking point. in the end the game started a conversation and i think that’s something that was done in earnest, despite its moments of obvious clumsiness.

regarding colonialism, this is another thing that the game is just Not About. we see the effects and consequences of colonialism demonstrated in the world of pathologic, and it’s something we’re certainly asked to think about from time to time, but the actual plot/narrative of the game is not about overcoming or confronting explicitly colonialist constructs, etc. i personally regard this as a bit of a missed opportunity, but it’s just not what IPL was going for.

instead they have a huge focus, as discussed somewhat in response to this ask, on the broader idea of powerful people trying to create a “utopia” at the mortal cost of those they disempower, which is almost always topical as far as i’m concerned, and also very Russian.

i think there was some interview where it was said that the second game was much more about “a mechanism that transforms human nature” than the costs of utopia, but it’s still a persistent enough theme to be worth talking about both as an abstraction of colonialism as well as in its more-likely intended context through the lens of wealth inequality, environmental destruction & government corruption as universal human issues faced by the marginalized classes. i think both are important and intelligent readings of the text, and both are worth discussion.

both endings of pathologic 2 involve sacrifice in the name of an “ideal world” where it’s impossible to ever be fully satisfied. in the Diurnal Ending, Artemy is tormented over the fate of the Kin and the euthanasia of his dying god and all her miracles, but he needs to have faith that the children he’s protected will grow up better than their parents and create a world where he and his culture will be immortalized in love. in the Nocturnal Ending, he’s horrified because in preserving the miracle-bound legacy of his people as a collective, he’s un-personed himself to the individuals he loves, but he needs to have faith that the uniqueness and magic of the resurrected Earth was precious enough to be worth that sacrifice. neither ending is fair. it’s not fair that he can’t have both, but that’s the idea. because that “utopia” everyone’s been chasing is an idol that distracts from the important work of being a human being and doing your best in a flawed world.

because pathologic’s themes as a series are so very “Russian turn-of-the-century” and draw a ton of stylistic and topical inspiration from the theatre and literature of that era, i don’t doubt that it’s also inherited some of its inspirational literature’s missteps. however, because the game’s intertextuality is so incredibly dense it’s difficult to construct a super cohesive picture of its actual messaging. a lot of its references and themes will absolutely go over your head if you enter unprepared -- this was true for me, and it ended up taking several passes and a bunch of research to even begin appreciating the breadth of its influences.

(i’d argue this is ultimately a good thing; i would never have gone and picked up Camus or Strugatsky, or even known who Antonin Artaud was at all if i hadn’t gone in with pathologic! my understanding is still woefully incomplete and it’s probably going to take me a lot more effort to get properly fluent in the ideology of the story, but that’s the joy of it, i think. :) i’m very lucky to be able to pursue it in this way.)

anyway yes, pathologic 2 is definitely very flawed in a lot of places, particularly when it tries to tackle race, but i’m happy to see it for better and for worse. the game attempts to discuss several adjacent issues and stumbles as it does so, but insinuating it to be in some way “pro-racist” or “pro-colonialist” or whatever else feels kind of disingenuous to me. they’re clearly trying, however imperfectly, to do something intriguing and meaningful and empathetic with their story.

even all this will probably amount to a very disjointed and incomplete explanation of how pathologic & its messaging makes me feel, but what i want -- as a broader approach, not just for pathologic -- is for people to be willing to interpret things charitably.

sometimes things are made just to be cruel, and those things should be condemned, but not everything is like that. it’s not only possible but necessary to be able to acknowledge flaws or mistakes and still be kind. persecuting something straight away removes any opportunity to examine it and learn from it, and pathologic happens to be ripe with learning experiences.

it’s all about being okay with ugliness, working through difficult nuances with grace, and the strength of the human spirit, and it’s a story about love first and foremost, and i guess we sort of need that right now. it gave me some of its love, so i’m giving it some of my patience.

#meta#discourse#long post#ipl#writing#Anonymous#slight edit for colonialism#untitled plague game#pathologic

109 notes

·

View notes

Note

How would you rate Sabatini's biography on Cesare? I love it, but I wondered if you had any other (English) recommendations? Also take a shot everyone Sabatini interrupts his narrative to talk about how hot Cesare was sfhttjjggj

I think as far as Cesare bios goes, I’d rate his biography 7/10.

I have conflicted feelings with Sabatini’s work, because I love his writing style, his sense of humour is great, it matched mine right away, and he has such a genius way of pointing out the hypocrisy and double standards applied to the Borgia family. He cleverly shows how much of the Borgia myths and general accusations thrown their way are connected to politics (shocker!) and to their Spaniard, and less nobly origins. Not to mention how he exposes the historical bias against Cesare, and general dishonesty with him, from primary sources to modern historians such as Gregorovius, that paragraph Sabatini wrote about him was truly a moment in the Borgia historical literature for me, I'm glad he said it.

I just wish he hadn't fallen so hard for the Machiavellian Prince archetype about Cesare. The more I re-read his work, the more it becomes clear to me he took Machiavelli’s writings about Cesare at face value, fell in love with the image presented by him, and then proceeded (whether consciously or unconsciously) to apply this interpretation, one that has its limitations and flaws on their own, to all the facets of Cesare’s character, and all the other aspects of his life lol, which resulted in this too strict, robot-like persona. There is no nuance, no deepth to Cesare’s Sabatini, he exists only as the stoic, unscrupulous, unfeeling Machiavellian Prince. It’s a mistake I see being made time and again by most of Cesare’s biographers, many who follow Sabatini too blindly, or just Borgia biographers in general tbh, but Sabatini’s bio acutely illustrates this particular issue better than the other bios I’ve read I think, (with the exception perhaps of Beuf’s “work”, who somehow managed to outdone Sabatini in this Machiavellian presentation of Cesare, taking it to new extremes with super dramatic and misleading writing, for the most part).

And you know, I always get the impression Sabatini had his own conflicted feelings in regards to The Prince, and its clear-headed, pragmatic politics. He seemed to admired it and feel repulsed by it at the time. And those mixed feelings sometimes ended up leaking into his view and writing about Cesare and some historical events, and what he believed had happened (e.g., the take of Urbino), and I find that very interesting. In any case, the point is: Sabatini’s Cesare is unrealistic, and it constantly enters into conflict with what Sabatini also presents as evidence for his history. I mean, he insists throughout the book in reaffirming Cesare was a utter egoist, cold man. Only moved by his ambition and thirst for power. He was incapable of kindness, or of being considerate with others, of feeling compassion, without ulterior motives involved. All of his actions were always calculated to only serve his own interests. Everyone around him were pawns to be used and discarded when they were no longer of any use to him. We are to believe he was a cynic, a block of ice, essentially. We are also to believe he never had genuine emotional bonds with anyone, much less with women. Women were interchangeble to him. Sabatini was convinced he was a man incapable of having a sentimental side, of loving or of having any connection with them beyond the physical aspect.

But then, in between chapters, sometimes pages, he also tell us how Cesare seems to have deeply grieved the death of his cousin, Giovanni Borgia, whom he refers as Mio Fatre in his letters. He gives an honest, if quick, account about the marriage and relationship between Cesare and Charlotte d’Albret, in which Cesare’s obvious feelings for her can be seen, as well as his kindness and respect towards her. Sabatini admits the evidence shows they may well have loved each other, and that when leaving Charlotte in charge of all his affairs in France, as the governor and administrator of his lands and lorships there, as well as his heiress in case of his death, Cesare shows “his esteem of her and the confidence he reposed in her mental qualities.”

And of Cesare’s policies and behavior as its ruler in the Romagna, it reaches a point where his mere self-interest doesn’t quite alone explain his relationship with this romagnese subjects and many of his decisions. It undermines Sabatini’s claim that it was for show and for his political gain. Last but not least, what is one supposed to make of the hypothesis he posits to the what I like to call, the Dorotea affair? This event is the peak of his contradiction and his mental gymnastics, because to be sure, his hypothesis is not far-fetched. I will concede I thought it was the first I read his bio. But over the years, between carefully separating fiction from history and reading other sources, then going back to his bio, I recognized his hypothesis is one of the plausible ones, certainly more plausible than the official sensationalistic narrative of Cesare simply abducting the innocent maiden Dorotea out on a whim, to satisfy his lust, (the fact Borgia scholars are still repeating this narrative with a straight face is beyond my comprehension), I can see Cesare doing what he proposes, it def. aligns better with my understanding of him, and all the historical material I’ve read about him and his times, however, this hypothesis is completely irreconcilable with Sabatini’s Cesare.

So, he says one thing, then he says another that’s incompatible with the first thing he said, and then proceeds to show evidence that either puts into doubt or confirms the opposite of his characterization of Cesare. And that’s only considering the historical info he dedided to include in his bio. If he had included some of the info Alvisi presents in his Duca di Romagna, a work he must have checked out, if not read it all, given one of the languages he spoke was Italian, and Alvisi’s bio is the best and most authoritative historical work made to date about Cesare and his life, I believe he would have struggled a lot more than he did. It just seems like he enters into a trap of his own making. Turning an already difficult task more difficult than it needs to be, honestly. Ironically, his stance is as messy and contradictory as the aforementioned Gregorovius in his Lucrezia Borgia, where you also have two Cesare(s): the one he sees and wants to present versus the one that emerges from the his own writing at times and historical material he himself exposes it.

Overall, his work frustrates on some fronts, and I think it could have been better. It has its faults, some the typical faults/vices fond in Borgia biographies, others very much his own, but nevertheless I have a fondness for his bio which I do not share with others bios on Cesare, or the Borgia family. It is the only bio in the English language I find myself reading again and again, and the one I would put it first as better, or more decent, in this language about Cesare. I admire his honesty, and his bravery in challenging a little bit of Cesare’s dark legend, and the baseless accusations attached to his name. I appreciate what he tried to do, the very least of what I expect from a serious historian when dealing with figures as infamous in popular imagination as Cesare and Rodrigo Borgia. There is no denying his work was one of the main works which advanced Cesare’s historical literature, and the approach to his figure. Moving slightly from the literary, colorful, villain-like character of the Italian Renaissance, towards starting to be more seriously studied as a historical figure properly.

And oh my god, yes, interrupting the narrative to talk about how hot Cesare was. It’s funny you mentioned that, because I don’t remember him doing that so much (time for a re-read!), but that's one of the characteristics of the Borgian/Cesarean historical literature heh. I’m yet to read a bio where authors do not feel the need to take a moment to talk about how hot he was, some even a poetic way lol, it’s so amusing, and always the one thing I know I will agree with them, if nothing else. Also, I think Borgia bios have huge potential for drinking games! Like: take a shot of tequila every time Cesare gets badmouthed for no reason, or baselessly asserted guilty of questionable murders, fratricide, rape, and abduction. Or when Juan and Cesare envied and hated each other narrative is repeated. Or when Guicciardini, Sanuto, Cappello and Giustinian are uncritically used as credible sources for Rodrigo and Cesare. Every time Lucrezia gets painted as the Good Borgia, the pretty, passive doll who was the helpless victim of the terrible Borgia men. Or when authors get uncomfortably shippy with the Cesare/Lucrezia relationship resulting in exaggerated claims such as: Lucrezia was Cesare’s only exception, or they were unusually close as siblings, etc. And of course, whenever Cesare’s hotness and allure has to be talked about dsjdsjsj, the list is long, and I think it will get you drunk very quickly. I know I couldn’t keep up back when I was reading Sacerdote’s bio, and I was drinking wine so.

As for recs in the English language, I would say Woodward’s bio has its value in terms of sources and historical documents. I also think his analysis about politics, about Cesare’s goverment in the Romagna, and also concerning the conclave of 1503 are generally good. His last five, four chapters are the best ones imo, so if you are interested in these points I mentioned, it might be worth checking out. I would just open a caveat saying that as far as a biography about the person of Cesare Borgia is concerned, it is weak and to be read with a grain of salt. I was mostly unimpressive by his work on that front, and I thought about quitting time and again. He likes presenting himself as the impartial historian, (a big red flag that only makes me twice as cautious when reading any historical work) writing in a mostly sober tone, but of course like all scholars, all people, he has his bias, and they do come to surface from time to time. He displays an peculiar antipathy and ill will towards Cesare at times, which leads to harsh, confusing, unsubstantiated claims about his character and some of the events about his life. In contrast, you can see he is more benevolent and fair towards Rodrigo Borgia, and a constant thought I had while reading his bio was that he obviously chose the wrong Borgia to write a bio on. Had he chose Rodrigo as his Borgia subject, I believe we would have had a pretty good bio about him and his papacy.

#ask answered#anon ask#cesare borgia#césar borgia#house borgia in history#auth: rafael sabatini#long text#i thought many times about making this shorter#but as it is said: yolo djsdjsdjs#i have many thoughts about sabatini#and the influence of his Cesare in followers scholars' works#i also think he had an interesting mind of his own#and i think that's part of the reason why i love his writings so much#despite their flaws#so yeah

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

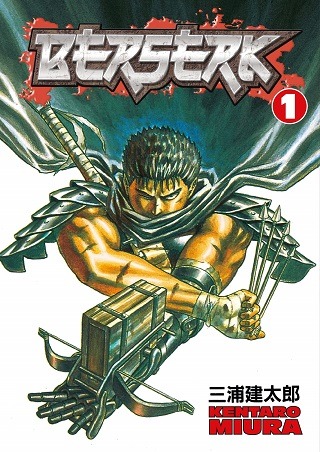

ESSAY: Berserk's Journey of Acceptance Over 30 Years of Fandom

My descent into anime fandom began in the '90s, and just as watching Neon Genesis Evangelion caused my first revelation that cartoons could be art, reading Berserk gave me the same realization about comics. The news of Kentaro Miura’s death, who passed on May 6, has been emotionally complicated for me, as it's the first time a celebrity's death has hit truly close to home. In addition to being the lynchpin for several important personal revelations, Berserk is one of the longest-lasting works I’ve followed and that I must suddenly bid farewell to after existing alongside it for two-thirds of my life.

Berserk is a monolith not only for anime and manga, but also fantasy literature, video games, you name it. It might be one of the single most influential works of the ‘80s — on a level similar to Blade Runner — to a degree where it’s difficult to imagine what the world might look like without it, and the generations of creators the series inspired.

Although not the first, Guts is the prototypical large sword anime boy: Final Fantasy VII's Cloud Strife, Siegfried/Nightmare from Soulcalibur, and Black Clover's Asta are all links in the same chain, with other series like Dark Souls and Claymore taking clear inspiration from Berserk. But even deeper than that, the three-character dynamic between Guts, Griffith, and Casca, the monster designs, the grotesque violence, Miura’s image of hell — all of them can be spotted in countless pieces of media across the globe.

Despite this, it just doesn’t seem like people talk about it very much. For over 20 years, Berserk has stood among the critical pantheon for both anime and manga, but it doesn’t spur conversations in the same way as Neon Genesis Evangelion, Akira, or Dragon Ball Z still do today. Its graphic depictions certainly represent a barrier to entry much higher than even the aforementioned company.

Seeing the internet exude sympathy and fond reminiscing about Berserk was immensely validating and has been my single most therapeutic experience online. Moreso, it reminded me that the fans have always been there. And even looking into it, Berserk is the single best-selling property in the 35-year history of Dark Horse. My feeling is that Berserk just has something about it that reaches deep into you and gets stuck there.

I recall introducing one of my housemates to Berserk a few years ago — a person with all the intelligence and personal drive to both work on cancer research at Stanford while pursuing his own MD and maintaining a level of physical fitness that was frankly unreasonable for the hours that he kept. He was NOT in any way analytical about the media he consumed, but watching him sitting on the floor turning all his considerable willpower and intellect toward delivering an off-the-cuff treatise on how Berserk had so deeply touched him was a sight in itself to behold. His thoughts on the series' portrayal of sex as fundamentally violent leading up to Guts and Casca’s first moment of intimacy in the Golden Age movies was one of the most beautiful sentiments I’d ever heard in reaction to a piece of fiction.

I don’t think I’d ever heard him provide anything but a surface-level take on a piece of media before or since. He was a pretty forthright guy, but the way he just cut into himself and let his feelings pour out onto the floor left me awestruck. The process of reading Berserk can strike emotional chords within you that are tough to untangle. I’ve been writing analysis and experiential pieces related to anime and manga for almost ten years — and interacting with Berserk’s world for almost 30 years — and writing may just be yet another attempt for me to pull my own twisted-up feelings about it apart.

Berserk is one of the most deeply personal works I’ve ever read, both for myself and in my perception of Miura's works. The series' transformation in the past 30 years artistically and thematically is so singular it's difficult to find another work that comes close. The author of Hajime no Ippo, who was among the first to see Berserk as Miura presented him with some early drafts working as his assistant, claimed that the design for Guts and Puck had come from a mess of ideas Miura had been working on since his early school days.

写真は三浦建太郎君が寄稿してくれた鷹村です。

今かなり感傷的になっています。

思い出話をさせて下さい。

僕が初めての週刊連載でスタッフが一人もいなくて困っていたら手伝いにきてくれました。

彼が18で僕が19です。

某大学の芸術学部の学生で講義明けにスケッチブックを片手に来てくれました。 pic.twitter.com/hT1JCWBTKu

— 森川ジョージ (@WANPOWANWAN) May 20, 2021

Miura claimed two of his big influences were Go Nagai’s Violence Jack and Tetsuo Hara and Buronson’s Fist of the North Star. Miura wears these influences on his sleeve, discovering the early concepts that had percolated in his mind just felt right. The beginning of Berserk, despite its amazing visual power, feels like it sprang from a very juvenile concept: Guts is a hypermasculine lone traveler breaking his body against nightmarish creatures in his single-minded pursuit of revenge, rigidly independent and distrustful of others due to his dark past.

Uncompromising, rugged, independent, a really big sword ... Guts is a romantic ideal of masculinity on a quest to personally serve justice against the one who wronged him. Almost nefarious in the manner in which his character checked these boxes, especially when it came to his grim stoicism, unblinkingly facing his struggle against literal cosmic forces. Never doubting himself, never trusting others, never weeping for what he had lost.

Miura said he sketched out most of the backstory when the manga began publication, so I have to assume the larger strokes of the Golden Arc were pretty well figured out from the outset, but I’m less sure if he had fully realized where he wanted to take the story to where we are now. After the introductory mini-arcs of demon-slaying, Berserk encounters Griffith and the story draws us back to a massive flashback arc. We see the same Guts living as a lone mercenary who Griffith persuades to join the Band of the Hawk to help realize his ambitions of rising above the circumstances of his birth to join the nobility.

We discover the horrific abuses of Guts’ adoptive father and eventually learn that Guts, Griffith, and Casca are all victims of sexual violence. The story develops into a sprawling semi-historical epic featuring politics and war, but the real narrative is in the growing companionship between Guts and the members of the band. Directionless and traumatized by his childhood, Guts slowly finds a purpose helping Griffith realize his dream and the courage to allow others to grow close to him.

Miura mentioned that many Band of the Hawk members were based on his early friend groups. Although he was always sparse with details about his personal life, he has spoken about how many of them referred to themselves as aspiring manga authors and how he felt an intense sense of competition, admitting that among them he may have been the only one seriously working toward that goal, desperately keeping ahead in his perceived race against them. It’s intriguing thinking about how much of this angst may have made it to the pages, as it's almost impossible not to imagine Miura put quite a bit of himself in Guts.

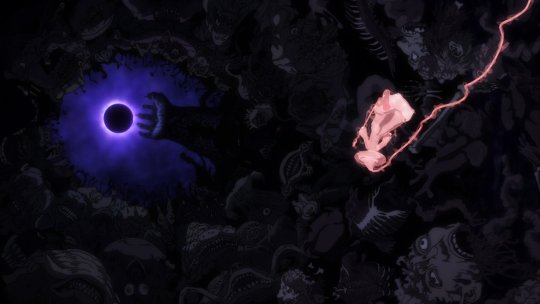

Perhaps this is why it feels so real and makes The Eclipse — the quintessential anime betrayal at the hands of Griffith — all the more heartbreaking. The raw violence and macabre imagery certainly helped. While Miura owed Hellraiser’s Cenobites much in the designs of the God Hand, his macabre portrayal of the Band of the Hawk’s eradication within the literal bowels of hell, the massive hand, the black sun, the Skull Knight, and even Miura’s page compositions have been endlessly referenced, copied, and outright plagiarized since.

The events were tragic in any context and I have heard many deeply personal experiences others drew from The Eclipse sympathizing with Guts, Casca, or even Griffith’s spiral driven by his perceived rejection by Guts. Mine were most closely aligned with the tragedy of Guts having overcome such painful circumstances to not only reject his own self enforced solitude, but to fearlessly express his affection for his loved ones.

The Golden Age was a methodical destruction of Guts’ self-destructive methods of preservation ruined in a single selfish act by his most trusted friend, leaving him once again alone and afraid of growing close to those around him. It ripped the romance of Guts’ mission and eventually took the story down a course I never expected. Berserk wasn’t a story of revenge but one of recovery.

Guess that’s enough beating around the bush, as I should talk about how this shift affected me personally. When I was young, when I began reading Berserk I found Guts’ unflagging stoicism to be really cool, not just aesthetically but in how I understood guys were supposed to be. I was slow to make friends during school and my rapidly gentrifying neighborhood had my friends' parents moving away faster than I could find new ones. At some point I think I became too afraid of putting myself out there anymore, risking rejection when even acceptance was so fleeting. It began to feel easier just to resign myself to solitude and pretend my circumstances were beyond my own power to correct.

Unfortunately, I became the stereotypical kid who ate alone during lunch break. Under the invisible expectations demanding I not display weakness, my loneliness was compounded by shame for feeling loneliness. My only recourse was to reveal none of those feelings and pretend the whole thing didn't bother me at all. Needless to say my attempts to cope probably fooled no one and only made things even worse, but I really didn’t know of any better way to handle my situation. I felt bad, I felt even worse about feeling bad and had been provided with zero tools to cope, much less even admit that I had a problem at all.

The arcs following the Golden Age completely changed my perspective. Guts had tragically, yet understandably, cut himself off from others to save himself from experiencing that trauma again and, in effect, denied himself any opportunity to allow himself to be happy again. As he began to meet other characters that attached themselves to him, between Rickert and Erica spending months waiting worried for his return, and even the slimmest hope to rescuing Casca began to seed itself into the story, I could only see Guts as a fool pursuing a grim and hopeless task rather than appreciating everything that he had managed to hold onto.

The same attributes that made Guts so compelling in the opening chapters were revealed as his true enemy. Griffith had committed an unforgivable act but Guts’ journey for revenge was one of self-inflicted pain and fear. The romanticism was gone.

Farnese’s inclusion in the Conviction arc was a revelation. Among the many brilliant aspects of her character, I identified with her simply for how she acted as a stand-in for myself as the reader: Plagued by self-doubt and fear, desperate to maintain her own stoic and uncompromising image, and resentful of her place in the world. She sees Guts’ fearlessness in the face of cosmic horror and believes she might be able to learn his confidence.

But in following Guts, Farnese instead finds a teacher in Casca. In taking care of her, Farnese develops a connection and is able to experience genuine sympathy that develops into a sense of responsibility. Caring for Casca allows Farnese to develop the courage she was lacking not out of reckless self-abandon but compassion.

I can’t exactly credit Berserk with turning my life around, but I feel that it genuinely helped crystallize within me a sense of growing doubts about my maladjusted high school days. My growing awareness of Guts' undeniable role in his own suffering forced me to admit my own role in mine and created a determination to take action to fix it rather than pretending enough stoicism might actually result in some sort of solution.

I visited the Berserk subreddit from time to time and always enjoyed the group's penchant for referring to all the members of the board as “fellow strugglers,” owing both to Skull Knight’s label for Guts and their own tongue-in-cheek humor at waiting through extended hiatuses. Only in retrospect did it feel truly fitting to me. Trying to avoid the pitfalls of Guts’ path is a constant struggle. Today I’m blessed with many good friends but still feel primal pangs of fear holding me back nearly every time I meet someone, the idea of telling others how much they mean to me or even sharing my thoughts and feelings about something I care about deeply as if each action will expose me to attack.

It’s taken time to pull myself away from the behaviors that were so deeply ingrained and it’s a journey where I’m not sure the work will ever be truly done, but witnessing Guts’ own slow progress has been a constant source of reassurance. My sense of admiration for Miura’s epic tale of a man allowing himself to let go after suffering such devastating circumstances brought my own humble problems and their way out into focus.

Over the years I, and many others, have been forced to come to terms with the fact that Berserk would likely never finish. The pattern of long, unexplained hiatuses and the solemn recognition that any of them could be the last is a familiar one. The double-edged sword of manga largely being works created by a single individual is that there is rarely anyone in a position to pick up the torch when the creator calls it quits. Takehiko Inoue’s Vagabond, Ai Yazawa’s Nana, and likely Yoshihiro Togashi’s Hunter X Hunter all frozen in indefinite hiatus, the publishers respectfully holding the door open should the creators ever decide to return, leaving it in a liminal space with no sense of conclusion for the fans except what we can make for ourselves.

The reason for Miura’s hiatuses was unclear. Fans liked to joke that he would take long breaks to play The Idolmaster, but Miura was also infamous for taking “breaks” spent minutely illustrating panels to his exacting artistic standard, creating a tumultuous release schedule during the wars featuring thousands of tiny soldiers all dressed in period-appropriate armor. If his health was becoming an issue, it’s uncommon that news would be shared with fans for most authors, much less one as private as Miura.

Even without delays, the story Miura was building just seemed to be getting too big. The scale continued to grow, his narrative ambition swelling even faster after 20 years of publication, the depth and breadth of his universe constantly expanding. The fan-dubbed “Millennium Falcon Arc” was massive, changing the landscape of Berserk from a low fantasy plagued by roaming demons to a high fantasy where godlike beings of sanity-defying size battled for control of the world. How could Guts even meet Griffith again? What might Casca want to do when her sanity returned? What are the origins of the Skull Knight? And would he do battle with the God Hand? There was too much left to happen and Miura’s art only grew more and more elaborate. It would take decades to resolve all this.

But it didn’t need to. I imagine we’ll never get a precise picture of the final years of Miura’s life leading up to his tragic passing. In the final chapters he released, it felt as if he had directed the story to some conclusion. The unfinished Fantasia arc finds Guts and his newfound band finding a way to finally restore Casca’s sanity and — although there is still unmistakably a boundary separating them — both seem resolute in finding a way to mend their shared wounds together.

One of the final chapters features Guts drinking around the campfire with the two other men of his group, Serpico and Roderick, as he entrusts the recovery of Casca to Schierke and Farnese. It's a scene that, in the original Band of the Hawk, would have found Guts brooding as his fellows engage in bluster. The tone of this conversation, however, is completely different. The three commiserate over how much has changed and the strength each has found in the companionship of the others. After everything that has happened, Guts declares that he is grateful.

The suicidal dedication to his quest for vengeance and dispassionate pragmatism that defined Guts in the earliest chapters is gone. Although they first appeared to be a source of strength as the Black Swordsman, he has learned that they rose from the fear of losing his friends again, from letting others close enough to harm him, and from having no other purpose without others. Whether or not Guts and Griffith were to ever meet again, Guts has rediscovered the strength to no longer carry his burdens alone.

All that has happened is all there will ever be. We too must be grateful.

Peter Fobian is an Associate Manager of Social Video at Crunchyroll, writer for Anime Academy and Anime in America, and an editor at Anime Feminist. You can follow him on Twitter @PeterFobian.

By: Peter Fobian

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

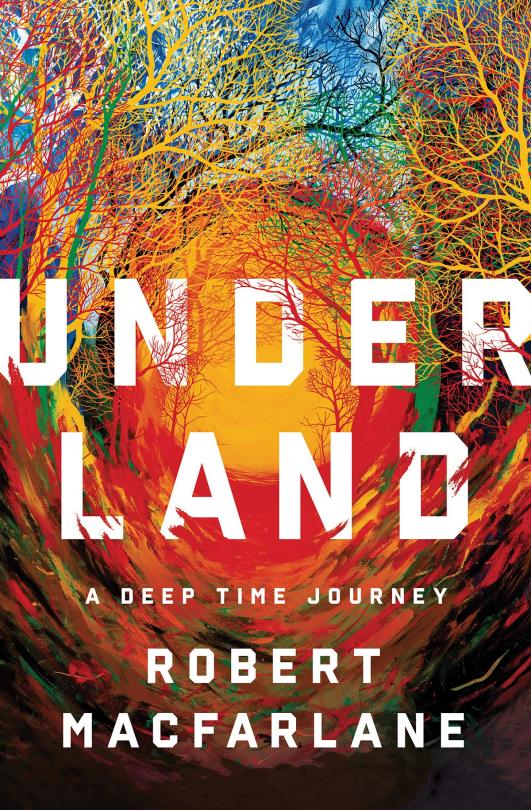

The Doll Factory

Author: Elizabeth Macneal

First published: 2019

Pages: 336

Rating: ★★★★★

How long did it take: 3 days

I felt that this book, while perhaps not exceptional, was very well put together. It was paced just right and the sense of growing dread escalates in a way which kept me glued to the page. Truly well written historical fiction.

Heaven and Hell: A History of the Afterlife

Author: Bart D. Ehrman

First published: 2020

Pages: 352

Rating: ★★★★☆

How long did it take: 2 days

I am rather conflicted about this book. Firstly, as a Christian bordering on agnosticism (I have never been a part of any church and my family is completely atheistic), I felt both somehow comforted by Ehrman´s deductions and somewhat resentful at the same time. Not because he very convincingly talks about the changing of religious perspectives (I am a historian myself so that information was only natural), but because he is clearly working with the notion of non-existence of God, not really treating it as a possibility. That, however, is my own personal issue. Objectively speaking, this is a very good book. Though academic in tone, it reads quite easily and is obviously well researched. The title, however, is misleading. Like many others, I had expected this to be a study of VARIOUS theories of afterlives, but 80% of the book is focused on early Christianity only. Not that isn´t fascinating, but for people hoping to learn something about other religions and cultures and their post-mortem ideas, it can only represent a big disappointment. So - know what you are getting, have an open mind and you might find this book a worthy addition to your personal library.

Wuthering Heights The Graphic Novel

Author: Emily Brontë, John M. Burns

First published: 2011

Pages: 160

Rating: ★★★★☆

How long did it take: 1 day

I don´t think there is much to review. I love the original book. I enjoyed its re-imagining here.

The Vanishing

Author: Sophia Tobin

First published: 2017

Pages: 390

Rating: ★★☆☆☆

How long did it take: 3 days

This was sort of OK I guess??? The beginning was promising, but I lost interest in the latter half, which also became somewhat convoluted. Not very memorable, though Sophia Tobin´s writing style is fine. I would not mind trying another book by her in the future.

The Mercies

Author: Kiran Millwood Hargrave

First published: 2020

Pages: 352

Rating: ★★★★☆

How long did it take: 7 days

Stunningly-written and deeply moving, this book has really only one weakness. It somewhat drags in the middle. But the atmosphere is alive and palpable and the emotions pure and real. There are many other books dealing with the topic of witch-trials, but few manage to be as powerful as well as respectfully restrained. Hargrave as an author knows how to keep the balance and her book beautiful.

The Wizard of Oz and Other Wonderful Books of Oz: The Emerald City of Oz and Glinda of Oz

Author: Frank L. Baum

First published: 1900, 1910, 1920

Pages: 432

Rating: ★★★☆☆

How long did it take: 5 days

This book is not commonly known in my country and so I have only read it for the first time now when I am over thirty. It definitely has its charm, especially the first volume, which holds some beautiful truths one wishes to teach the children (or adults). The Emerald City of Oz and Glinda of Oz are both mostly just a flight of fancy with no actual conflict. In fact, the danger to any of the characters is so nonexistent it begs the question of "why should I care". Not bad, but perhaps I would have loved it more if I was 5, not 33. Mea culpa.

Vasilisa the Wise and Other Tales of Brave Young Women

Author: Kate Forsyth

First published: 2017

Pages: 103

Rating: ★★★★☆

How long did it take: 1 day

Very sweet retelling of several classic fairytales in which the girl saves herself (even if she needs some help by others, and the others are never the prince).

S.

Author: J.J. Abrams, Doug Dorst

First published: 2013

Pages: 456

Rating: ★★★★★

How long did it take: 19 days

This book felt like an acid trip with Umberto Eco or something in a similar vein to me. I was rather terrified that the whole thing would be completely dependant on the unusual format, but to my delight, the format merely enhances and enriches the actual novel, which in itself is dark, confusing, moving, terrifying, philosophical and weirdly fascinating. I am sure a lot has escaped my attention or flew over my head, but I welcome it because it gives me more reason to return to the book in the future.

It was not all flawless though. My biggest gripe, as an actual Czech person, is that even though so much effort and thought went into the creation of this book, the author decided that Google translate will do just fine - and no surprise - it did not. There are not many instances of the Czech language being used, but when it is... it is all wrong. The Czech language is quite difficult and complex and Google translate does not know how to deal with it most of the time. Just one example: In the book, Eric writes OPICE TANCE on the wall and says it is Czech for "MONKEY DANCES". Yeah. Yeah, it is. IF THE WORD "DANCES" IS TAKEN AS A NOUN IN PLURAL. The correct translation would be "OPICE TANČÍ" and trust me it IS a big big difference. (Do not get me started on the vintage newspaper article....)

You definitely need a lot of brainpower and focus when reading, this is not an easy book to follow. You also need to accept that not all questions are answered. I am glad I read it though. I found it an interesting experience.

The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring

Author: J.R.R. Tolkien

First published: 1954

Pages: 407

Rating: ★★★★★

How long did it take: 3 days

What can I say? Yet again I had goosebumps and tears in my eyes. Few, very few books have the power of this one.

Mexican Gothic

Author: Silvia Moreno-Garcia

First published: 2020

Pages: 301

Rating: ★★★★☆

How long did it take: 12 days

I don´t have much to say but I was a bit bored at the beginning, but it turned out to be a pretty wild ride.

Aristokratka u královského dvora

Author: Evžen Boček

First published: 2020

Pages: 184

Rating: ★★★☆☆

How long did it take: 1 day

Miluji celou tuto sérii, bohužel tento díl mi, ač stále zábavný, přišel prozatím nejslabší... Měla jsem pocit, že první polovina knihy opustila můj oblíbený, laskavý humor teenagerky, která se musí potýkat s výstřední rodinou a situací, a sklouzává spíše trochu k upřímné krutosti... Doufám, že další pokračování se vrátí ke své laskavosti.

The Splendid and the Vile: A Saga of Churchill, Family and Defiance During the Blitz

Author: Erik Larson

First published: 2020

Pages: 608

Rating: ★★★★☆

How long did it take: 2 days