#because these cultural norms are formed by placing increased importance on white ways of doing things

Text

Maybe I'll go into more detail on this later but I was in class last week and we were talking about how to incorporate social justice into our pedagogy and curriculum as math teachers (because there's a lot of people who think social justice doesn't belong in the math classroom and should be left to the social studies teachers and those people would be wrong)

So we were looking at the development of racial identity and how it's impacted by education because education is currently built on a lot of structures that stem from white supremacy and we were looking at a framework that lays out a lot of the cultural features of white supremacy and uh...

Let me just say that a lot of "cancel culture" and the anti mentality is really, disturbingly aligned with the cultural facets of white supremacy, and I don't think it's coincidental.

This is the pdf that our field instructor gave us to give us a foundation to build our discussion on: link to pdf.

This isn't to say that everyone who ascribes to these ideologies of cancel culture or antis is a white supremacist. I'm not making any statements on anyone's motivations or intentions here.

I just want to say that it's important to educate yourself on these things, because it's very easy to go into something with good intentions and find those who want to take advantage of that.

#hashtag rambles#do not let tumblr be your education on social justice#i say as i try to educate people on social justice using tumblr#basically i mean you need to go to sources outside of tumblr#reputable sources#and you know examine multiple sources and make informed decisions that way#and yes sometimes that means looking at sources you disagree with#so like this document isn't about any kind of hate groups or blatant hate actions#it's about cultural norms that stem from white supremacy#because these cultural norms are formed by placing increased importance on white ways of doing things#and enforcing these norms is a way of upholding white supremacy#just want to clarify that because my class was a little confused as well

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here is why conventional healthful-thinking is not working on Millennials.

Have you ever had that terrifying dream where you are stuck in a dark forest or sketchy alley, frantically running for your life from some kind of feral monster or mad man? Most of us can personally recall at least once being roused from sleep in a cold sweat because their brain had spent the last few hours perfecting the latent image of a made-to-order nightmare. While that experience is certainly not exclusive to Millennials (rather quite the opposite), the waking reaction or at least how it is processed later by this roughly categorized group of mislabeled people is unique to say the least.

For years now, people in marketing have been fervently dissecting and attempting to recreate what has been loosely categorized as "Millennial Humor". And in all of their efforts to connect with this flock of black sheep, the grand majority of them seem to be missing a key factor in the psychology at work here. For all the unwarrantable bilge that modern advertising haphazardly cobbles together, only a small percentage of the nonsense is seasoned perfectly with the secret ingredient. What is this singular spice? Well, while indulgent to profess and speculative, from someone "sitting in millennial class”, it's obvious: A touch of salt.

Never will I sit here and cry to the general public about how unhappy I am that the modern advertising industry is just not scratching my itch for the wares it’s peddling, but I think it's important for us now to look at how this systemic lack of understanding is reaching beyond the world of subliminal profiteering. Society has other significant quality-of-life effecting systems that are also missing the mark when trying to aim and reach out to help this specific group of people. Puns aside, "a touch of salt" as I quipped, is flavoring the lives of a lot of people in their mid to late 20's and early 40's. And the most frustrating and difficult to reconcile attempts that I personally have made to better myself, have been those that were guided by people who just cannot seem to put their brain into that salty head space.

For example, trying to focus on and internalize a well-organized medical presentation about the encompassing negative effects of stress or insomnia and its seemly simple solution of just "changing your thinking", is about as easily digestible as a two-decade-year-old fruitcake for someone who is imprisoned daily by the symptoms of chronic stress. While I may sit there and give listening (ironically) "the old college try", the sound quickly turns to fuzzy white noise the deeper the lecture dives into positive thinking.

You see, Millennials are not generally fluent in positive thinking. More and more of them seem to be speaking a very distinctive dialect of realism, which incorporates a robustly cultivated sense of sarcasm and a somewhat grim shade of hopelessness. A lot of millennials grew up with a laughably poetic twist on "Growing Up" and "Being Successful", which in turn has colored their day-to-day interactions and created this defeatism-culture. Millennials will openly joke about their death as a needed release, their eulogy as a retirement card, or emotionally decompile themselves over something simple like saying "you too" in a situation that doesn't warrant it.

A good percentage of Millennials were old enough to understand the destructive consequences of the most recent housing market disaster on a very personal level; At an impressionable age, watching their own parents, who may have worked excruciatingly hard at the expense of any number of personal or family goals, lose just about everything resonated in a way that cannot be unheard. Then add the borderline criminal and unscrupulous "sheep-shearing" that became common place when the generation was herded off to college, trade school, or other form of career-building education. Not to mention the fact that upon completing said programs, a proverbial "step-in-the-right direction", a substantial number of these "hopeless wanderers" were faced with yet another barbed-wire hurdle when the job market in countless fields were oversaturated with potential employees. Many positions had not been vacated as they normally would have been with the age of retirement being stretched further and further down the road due to increased cost of living and financial demands; the finish line or lap marker was just not getting any closer. To add insult to injury, Millennials, sometimes unbelievably hardworking, are frequently being listed as perpetuators of the clashing reality we have today. This being what the modern media is calling "The Great Resignation"; a dubious combination of a labor shortage amidst an unemployment spike fueled by uncompetitive wages left unchecked, the government's inability to reel in the situation, and a general devaluing of laborers overall.

Oh. And also, we were killing the diamond industry at the same time. Or was it simultaneously the marriage and divorce industry? Wait! I think it was cinema? Or no....maybe it was fabric softener. For a complete dissertation of all the things Millennials brutally murdered over the last two decades, perhaps I'll include a link below if for no other reason to drive my point home.

You have this group of people who are conditioned to endlessly swimming upstream, against the current, with nothing but chastising and bitterness to listen to. So, when it comes to something universal like learning to "sleep better" or "problem solving", the indifferent but somehow time-honored approach of saying "it's as easy as just taking control" is over time if not immediately rejected as dissonant information.

These people don't feel like they have control; some of them feel like they never had any to begin with.

Why is this a problem?

Our society is not developing a taste for "salt" at a pace in which it can prepare social-sustenance for its population. We're not getting any younger, and neither are the generations in front of us.

Millennials are already, by some definitions the mass-population of workers, voters, and other titles that we've yet to embrace. And our lack of interest is not because we do not have a passion for positive change (even on a global scale). Millennials have voiced over time that they feel they are the silent majority amidst a group of people who will not give them breathing room and don't respect the validity of their opinions and ambitions. And it is by no means restricted to one region or country on this planet. This is a global phenomenon.

I could spin a vast yarn about the political ramifications of continuing to exclude the Millennials from the metaphoric Counsel of Elders, but I'm more concerned about the neglect that is spreading elsewhere. We need our leaders in the medical and social fields to really respect and dig deep into how to incorporate "Millennial Thinking" into their treatment and development plans. A large amount of the global population is going to need carefully tailored treatment for things as old as depression, bi-polar tendencies, or schizophrenia as well as newly discovered mental encumbrances like imposter-syndrome.

While “positive-thinking” may have been easily cultivated in the past, we may need to start from a more negative approach and build from there to educate and treat a group of down-on-their-luck millions. Pumping drugs into a populace is not going to permanently patch the leak either, so there truly is precedence for a rehashing of how we should prioritize mental health in modern society.

Stop spending so much time and energy assigning blame to modern technologies and social norms. Are these going away? No? In that case, those things are much like our other daily stresses that are unavoidable. Yes, you can change your nightly routine to de-stress the same way that you can change a job or a daily commute, but there needs to be a fundamental shift in accountability divvied to circumstances out of a person's control rather than scolding them for not being able to manage it.

Do I have all the answers? No.

But this was less about offering a solid a solution and more about opening a dialogue. A starting point.

So yeah. I've had that dream of being chased through the woods by a life-leeching alien. It felt very similar to being sucked dry of my pitiful wages for an education that was at the time, barely panning out. Even now, as a 32-year-old, slightly more successful version of the starving student I've become, I still feel as though my rat race will end when my heart gives out; and all I can hope for is enough money when I drop to cover the ambulance ride to the over-crowded emergency room and a large pit to rot in. But I just hope that the generation behind me has the benefit of a system that understands how to create and sustain “Millennial Inspired” social structures that will allow them to flourish in what little we can leave behind for them.

Also, could you pass the salt?

1 note

·

View note

Text

CHSA Interns Respond: What does AAPI Heritage mean to us?

This month, we asked our interns to share their reflections on AAPI Heritage, answering the question, “What does AAPI Heritage mean to you?” Here’s what they wrote:

AAPI Heritage Is…

...a living history

Shou Zhang, Research Intern (We Are Bruce Lee)

I am a 1.5 generation Han Chinese American.

I believe our communities' diverse and beautiful history lives through us like water flowing from the past into the present and onwards to the future. Our very existence in this country is a testament to the resilience of those who came before us. When I can go to a Chinese grocery store and buy goods that satisfy my taste for the Chinese Lu culinary cooking style, that experience is the legacy of our lived history. When I cook the dishes that my family taught me, the very act of it is a celebration of my Han Chinese culture.

Examples of China’s Lu cuisine, originating in Shandong. (PC: China & Asia Cultural Travel).

To me, the AAPI history of my community is a lived experience. I recognize that the Han Chinese and Han Chinese American community in America are members of a wider community whose struggles and experiences intersect with our own. So for me, AAPI History Month means going beyond protecting, sustaining, and sharing the history of the culture of my community – it means finding the emotional space to listen to the stories of other AAPI communities.

In my journey as someone who grew up and emigrated from the People's Republic of China, I have been particularly invested this month in learning more about the lived experiences of other ethnic and indigenous communities who emigrated from mainland China, who have had a drastically different experience than my own.

...a way to understand my identity

Samantha Vasquez, Research Intern (Chinese in the Richmond)

Being Asian American is integral to my identity, as I have spent almost twenty-one years attempting to understand what it meant to be Asian and American. I am a Chinese adoptee with a third-generation Chinese American mom and a first-generation Mexican American dad. I learned about the term "third-culture kid" in a Multiracial Americans course in college, and I found it to describe my experiences almost perfectly. This experience is defined as the phenomenon in which a child grows up with their parents' culture and the culture of the place they grew up. Both of my parents grew up in the U.S. and have navigated what it means to be American. For me, I have my Chinese heritage, through which I participate in traditions and cuisine, and I also have my Mexican culture, through which I understand Spanish phrases and attend religious ceremonies.

There are so many nuances with my identity that I had trouble understanding when I was younger, but I embrace being Asian American because it can encompass these nuances. I want to give my children the tools to begin to understand their identities, no matter what their culture is. I want them to know my parents and their cultures' influence on my upbringing. I want them to embrace all cultures and realize how interconnected we all are.

...a source of political strength

Katherine Xiong, Community Programs Intern

I have to admit that I struggle a lot with the term “AAPI.” Doubtless, the lived experience of individuals grouped together under the AAPI umbrella are extremely disparate -- even within ethnicities, there’s so much diversity that it’s hard to say that people belong ‘together.’ Take the term “Chinese” for example: It’s fuzzily defined. It can (or can not) include diaspora from the mainland, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore, etc., many of whom chafe under the label “Chinese American” because of political connotations in their countries of origin. It can include descendants of the first railroad workers, migrant workers, and communities facing gentrification, but can also include some of the richest people in America, many of whom have become the gentrifiers. We don’t all have the same history, or the same political issues, either. Questions of affirmative action that my conservative parents are thinking about and questions of media representation my friends are thinking about are not the same problems that massage workers or Chinese American elders in large cities are facing. Zoom out to all of the ‘AAPI’ umbrella, and the differences grow still vaster. Yet outsiders often read us as “all the same.”

A protestor displays her support for solidarity between the Black and AAPI communities. (PC: NBC News).

As I interpret it, the power of the term “AAPI” has less to do with identity and more to do with politics. And it’s not about having the same political ‘issues’ or racial/ethnic stereotypes. It’s about coalition-building and solidarity in spite of difference -- building from communities up, across ethnic and class lines. It’s about recognizing the ways in which we all get ‘read’ as one people from the outside and leveraging those misconceptions to say, ‘If you treat us all as one people, fine. Then we’ll face our problems together, and support each other in each other’s problems, no matter how different we are. We are not the same, but our communities do not have to form around divisions and differences. We can borrow each other’s strength. We can -- and will -- make change.”

...the past (and the people) who shaped our present

Samantha Lam, Development Intern

As Asian Americans, we have been taught to believe that we are the model minority, and thus a greater ‘proximity to whiteness.’ AAPI history tells us the exact opposite. For example, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was the first immigration ban towards a specific ethnic group, and was only fully repealed with the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, which abolished the National Origins Formula. Discrimination towards Asian Americans is not as much a “thing of the past,” as some people like to think.

I cannot stress how important it is to know about how we as Asian Americans have reached our current status, thanks to the sacrifices of people like early Chinese laborers, who came to the U.S. hoping to find work, and Asian American activists who fought for our civil rights. I know more about this thanks to heritage museums and cultural institutions like CHSA. I am so grateful to CHSA for filling in the blanks for me and many other young Asian Americans who may not have been taught Asian American history in school.

High school students in Oakland at Black Panther Party funeral rally for Bobby Hutton. (PC: Asian American Movement 1968).

AAPI Month this year has been far sadder than I think anyone anticipated with increasing reports of hate crimes towards Asians. However, I can see a silver lining in the uptick in Asian American activism and with more resources being made available online discussing topics like intersectionality and the history behind the model minority myth. I believe learning and connecting with Asian American history has allowed me to better understand the struggles other minority groups have faced here in the U.S., and I know I need to do more with the privileges I have.

…a diverse community with many voices

Kimberly Szeto, Education & Research Intern

Real talk: I am not the biggest fan of umbrella labels like AAPI, API, etc. There is so much to being Asian American or being Pacific Islander that just gets bunched up into one monolithic category. As people, we are more than what labels and stereotypes define us to be.

But what the labels such as “AAPI” and “API” do instead is bring together a community of people with similar but different backgrounds and give a space to embrace and celebrate who we are, as well as giving us a voice. Yes, May is the month to celebrate AAPI, but why don’t we celebrate all year round? As Asian Americans, we should not have to conform to what “societal norms” in the U.S. constrain us to be, for us to stay quiet and not rock the boat in fear of backlash. Furthermore, we must debunk the model minority myth stereotype, where Asians are seen as uniformly more prosperous, well-educated, and successful than other groups of people. This is a dangerous generalization of vastly different groups of people, one that allows the white majority of America to avoid responsibility for racist policies and beliefs. We need to embrace who we are and educate those who may not know or are less aware.

I started hearing the term AAPI more prominently when I got to college and found a place in the AAPI community at UC Santa Cruz. I think this is where I started to feel more comfortable and began to champion my Asian American identity because I felt like my community was a safe space. I was no longer embarrassed by my family out in public and the customs of our culture that others may have found foreign.

As an Asian American, I think it is very important to keep history and customs alive. That includes our lives here in America as well as the history of those who came before us, and all the triumphs, struggles, and little things in between. These are the experiences that should form the narratives of any human being, no matter where you are from and who you are.

I invite you to celebrate AAPI Month with me, and to encourage you to embrace your own heritage and to educate and support yourselves and others.

#chsa#chsamuseum#chsacomcon#community connections#aapiheritagemonth#AAPIHM#reflections#heritage#asian america#pacific islander

5 notes

·

View notes

Link

My article “Why is Everything Liberal?” has gotten a great deal of attention. See in particular thoughtful commentary from Bryan Caplan and Robby Soave at Reason.

This post is a followup, with two main goals. First, I’ve discovered additional evidence that liberals care more about politics, which I will just add on to what already was an extremely strong case.

Second, some people criticized the piece for not addressing what has changed recently. I think I’ve found the answer to that too, which is that the mobilization gap increased precipitously in 2016. It is at that time that we see Democrats overtake Republicans in fundraising, liberals overtake conservatives in signing petitions, and the left’s already sizable lead in protesting become much larger. While it seems that liberals have always cared more about politics if we are looking at the tail end of the distribution–i.e., those who become activists, journalists, or academics–it is only in 2016 that we see more noticeable and significant gaps open up in the next level down in the pyramid.

Since 2016, liberals have achieved true mass mobilization in a way conservatives never have in the modern era.

…

In 2016, fewer than 1% of conservatives had been to a protest in the last year, compared to 15% of extreme liberals, 10% of regular liberals, and 5% of the slightly liberal. Even moderates, at 2.4%, protested more than conservatives. Remember, this was before the Women’s March and the peak of BLM! The estimates for protest size used in the original post were pretty crude, but it’s nice to see self-reported data match what we see in the real world. Petitions tell the same story, but the differences are not as extreme: 61% of very liberal individuals had signed one in the last year, compared to just 26% of the very conservative.

…

Liberals already tended to protest more in the years leading up to 2012. But conservatives used to at least hold their own. This matches what we know from the real world, as this was the height of the Tea Party. Glenn Beck’s largely forgotten “Restoring Honor Rally” in summer 2010, for example, drew a lot of people, though nobody really knows how many. Wikipedia says “a scientific estimate placed the crowd size around 87,000, while media reports varied wildly from tens of thousands to 500,000.” This was also the time of Occupy Wall Street, so liberals weren’t exactly sitting on their hands, but conservatives at least made a showing. By 2016, conservative protesting had collapsed to practically nothing, while liberal protesting stayed at similar levels or, more likely, increased (hard to know for sure because of the time frame of the 2012 question being different).

…

In 2012, liberals were more likely to sign petitions than conservatives, but the gap was pretty small and there were many more conservatives in the country, which meant the right actually had more total people signing petitions. By 2016, more Americans than before were calling themselves liberals, and liberals were more mobilized, giving the left a substantial advantage.

Another thing we can do to see how relative mobilization has changed over time is to look at campaign donations. In the previous essay, I went all the way back to 2012, and showed that for every recent presidential election cycle Democrats brought in more money. I didn’t go back to 2008, as I was sure Obama outraised McCain, and I was of course right.

However, if you expand the analysis to midterm elections and all federal candidates, we see the Democrat advantage does not open up until 2016. Here are numbers I’ve gathered from Open Secrets for every election from 1990, as far back as data go.

…

In response to my piece, Ezra Klein argued that liberal domination of institutions was better explained by age and education polarization than liberals caring more. This is an argument I’ve seen him make elsewhere before (see also this and this from Josh Barro on Woke Capital).

…

Romney won college educated whites by somewhere between around 5% and 15%, while according to CNN’s 2020 exit polls, Biden won the same demographic by 12%. CNN actually has Trump barely winning college educated whites in 2016 (48%-45%). Education polarization is real, and the fact that college educated whites vote something like 15-30% more Democrat than they did in 2012 should be having some effects on board rooms and the larger mobilization gap. Yet educational differences do not seem nearly massive enough to explain the total liberal domination of institutions, as Republicans hold their own well enough with degree holders.

As far as the age gap, it can cut both ways. When I was growing up in the 1990s, the stereotype was that retirees had a lot of time on their hands and were therefore politically powerful, while young people were largely indifferent. Old people certainly have more money, and so you’d expect age polarization to actually give Republicans an advantage in donations. Yet since 2016 the trend has been the opposite. As parties have polarized more by age, Democrats have started winning the competition over fundraising. Maybe young people are inherently more likely to protest, but wouldn’t you expect old people to be just as capable of signing petitions? Thus, I’m pretty confident that age and education gaps are less important than the simple fact that liberals care more about politics.

…

The left has always had an advantage in committed activists. Yet, no matter whether you look at donations, protests, or signing petitions, the mobilization gap increased in 2016. Liberals had always protested more, but in 2016 the ratio was absolutely massive, being around 3.7x larger than it was around the time of the invasion of Iraq. This was before an upsurge of liberal protest activity that has included BLM, March for Our Lives, and most importantly, the Women’s March. Finally, the parties raised about an equal amount of money from 1990 until 2016, when Democrats took a lead that has now lasted three straight election cycles (2008 was an exception to the rule of parity in the pre-2016 era, when Democrats ran a fresh faced Barack Obama against John McCain, who seemed good at exciting Republican elites and MSNBC pro-war centrist types but not actual voters).

So what about “Woke Capital”? In many ways, business was the last domino to fall. Yes, liberals have always had more noisy activists, and corporations tended to bow to them on some issues when they got really agitated, like MLK day. But big business is more directly answerable to a wider swath of the population than are schools or non-profits, and so held out the longest. Coca-Cola and Walmart care more about what the median citizen thinks than does Harvard, The New York Times, or the ACLU. Yet after 2016, when the mobilization gap exploded, almost nothing in society could remain neutral, and pressure has come from both within and outside corporations for them to take a stand on almost all hot button issues.

Why was 2016 the year everything changed? Take a wild guess.

…

Just as the previous post raised further questions, this one does too. The most interesting thing to me is not simply protests and donations, but why one side has for over half a century now drawn more idealistic people who want to dedicate their lives to changing the world. The journalist-academic-activist complex is ultimately where power lies, and it has grown much stronger in the last 5 years because it has started to engage many more people at the intermediate level in the mobilization pyramid, among those who give money, sign petitions, and go to protests, and who find themselves between true elites on top and the mass of the largely indifferent voting public at the bottom.

If the rise of Trumpism explains the last five years, why did the left begin with such a strong built-in advantage? I hope to explore this question soon.

…

Moreover, right-wing protest culture has collapsed since the time of the Tea Party. It’s hard to know for sure, but other forms of conservative activism may have fallen off too. So even the degree to which Trump has actually mobilized the right must come with a caveat: he has turned out more Republican voters and gotten more people to donate small amounts of money, but few seem to want to make more substantial sacrifices, even compared to 2012.

Overall, the Trump era has provided mixed electoral results for Republicans. They won unified control of government in 2016, lost the House but kept the Senate in 2018, and came extremely close to winning again in 2020. Yet it has been an awful 4 years for conservatives who care about controlling institutions, or at least keeping them neutral, although even here it hasn’t been a complete loss. After all, the Trump era has given conservatives a comfortable majority on the Supreme Court, probably the most important single institution of all.

Federal court appointments last until death, while the widening of the mobilization gap is relatively new. Best case scenario for Republicans is that Amy Coney Barrett and Brett Kavanaugh live for a very long time, while the Trump era ends up being an anomaly in mobilizing the left to an unusual degree, with things going back to something resembling the pre-2016 historical norm. Worst case scenario is that things continue as they have for the last 4 years, with anti-Trump hysteria combining with the Great Awokening having created a class permanently mobilized for confronting racism and other evils, plus Republicans not even getting the mobilization on their own side that Trump gave them. A generation shaped by the experience of Trump and a party currently led by such uninspiring figures as Kevin McCarthy and Liz Cheney may end up giving conservatives the worst of all worlds.

1 note

·

View note

Text

A Growing Number of People Are Identifying or Presenting Outside of the Gender Binary – Why?

In the Western world, the gender binary has played a huge role in society. Gender roles have determined how people act, what they wear, what jobs they can get, and even what place they hold in society. Even in modern societies people are punished for going against the gender norms; men are attacked for wearing ‘feminine’ clothing and are often called gay for feeling comfortable in themselves and in expressing how they feel. However, despite this, in recent years the number of people expressing themselves in ways that do not fit the status quo, and doing so openly, have been increasing, and with this increase the number of people who are supportive of this are doing the same. Here, I will be discussing why I think that this is becoming the case.

It is important to note that this is in no way a new phenomenon. Some people have been going against the grain throughout recorded history, although for this topic more modern examples are more easily applicable. In the twentieth century, many ‘celebrity icons’ were seen to be breaking the stereotypes, and in some genres of music men dressing in ‘feminine’ clothing was part of the genre or band’s image. One of the most notable people to have been challenging these norms at this time was music legend David Bowie, who was recognized for incorporating aspects of both masculinity and femininity into his androgynous look, and who also wore a dress on the cover of his album ‘The Man Who Sold the World’. Even then, as aforementioned he is certainly not the earliest example of this idea of ‘breaking the norm’ when it comes to gender, and this outlook of what is expected of people in terms of gender roles is a very Western one.

Many non-Western cultures often have gender systems that work differently to how gender is seen elsewhere, most notably different from mainstream Western culture. Generally, in the Western world, gender is traditionally seen as the same as biological sex of a person at birth (usually characterized by sex characteristics and chromosomes, although this can differ for intersex people), however in recent years the existence of binary transgender (trans men and trans women) people has become more accepted. One of the most well-known examples of cultures where the gender system is different to what we are used to is among Indigenous and Native American communities. The term Two-Spirit is one that is reserved for people within native cultures, who are both masculine and feminine. These people can also have very specific spiritual or societal roles [Gender Identity, University of South Dakota website]. This identity, and many others across other cultures, is rooted in not only their culture but their traditions also. Despite this, they are almost unheard of due to the forced teaching of Western ideals that occurred predominantly due to colonization.

I present this example to prove that Western examples of gender are not inherently ‘correct’. If, for example, these differences were not seen anywhere in the world, and all cultures’ ideas of gender were the exact same, one could make the argument that gender identities, and therefore gender roles, are entirely based on biological sex, however, as there are clear differences seen between cultures, I would instead argue that this link is, at least partially, social. In cultures where it is more accepted to identify and present in ways that go against the idea of a binary gender system, people feel comfortable in openly doing so. This explains why, in today’s society, where it is slowly becoming more acceptable to do such things, more and more people are beginning to comfortably present and identify how they wish.

Another point I will make, before moving on to why it is that I think this change in what is acceptable is occurring, is that this is not the only time such a change in traditional ideas of what is associated with a certain gender has occurred. When thinking about the most stereotypical ideas of what differences there are between the two sexes by societal standards, some of the most obvious I can think of are the following. Blue is for boys; pink is for girls. Boys wear trousers, girls wear dresses. Women should shave and wear makeup to be presentable, but men are not required to shave and are often discouraged to wear makeup. However, these have all been very different at various points in time. The colours blue and pink were first used as gender signifiers at around the 1940s, however prior to this the colours were often not gendered, and in many cases when they were associated with a gender, pink was associated with boys and blue with girls. Skirts were not gendered until reasonably recently also, with men across history wearing skirt-like cloth wraps or forms of kilts. In fact, it is argued that the only reason men stopped wearing skirts is because they were the ones who rode horses most often, and skirts were simply impractical for this purpose. Makeup has been worn by all throughout history, most notably being given to the male workers in ancient Egypt along with ancient skin care products as a form of payments, and also being worn by the nobility for centuries, particularly in eighteenth century France. Women were not required to shave until after the Victorian era of long dressed that would cover all skin, and even then, the only reason that they did was because shaving companies made the realization that they could make more money by targeting razors at the young women who were now wearing clothing that was more revealing.

If these ideas of what is normal are constantly shifting, then why do they play such a large role in societies today? And why are other cultures’ ideas of gender systems being stifled by predominantly white Western cultures? I believe that these realizations are one of the reasons that an increasing number of people are beginning to openly present or identify outside of the norms of the gender binary. As more people become aware that the norms that they are confined to have little to no genuine reasoning behind them, they are beginning to feel less pressured to conform to these roles. The growing number of people at the forefront of popular culture who are also making this realization and are challenging these norms are simply providing a way for people to see that there is nothing wrong with presenting or identifying in a way that is not seen as ‘normal’, and so I believe that this is at least partially responsible for the increasing number of people choosing to break these norms. I also believe that the national lockdowns due to the coronavirus pandemic have played at least some role in this change, particularly in those identifying outside of the gender binary. Nonbinary individuals are in no way new, however the amount of people who have come out as nonbinary in recent times is increasing. I believe that this is because, while stuck inside away from other people, these people have not been subjected to the pressures and judgements of society. They have not had to conform to how they ‘should’ be, and I believe that this time has given many people, particularly young people, a way to reflect on their identity and whether or not they truly fit into what is expected of them. This, along with the more frequent use of the internet due to not being allowed to do ‘normal’ activities in the lockdowns have, in my opinion, hugely impacted young people’s sense of identity in an almost entirely positive way.

In conclusion, I believe that a growing number of people are identifying or presenting in ways that are outside of the gender binary because of a lack of pressures and expectations from the rest of society, and because of a growing understanding that many of these expectations are not formed on any logical or reasonable basis and are instead simply kept up due to outdated traditions which, in this instance, are causing more harm than good. As this is entirely my own opinion, it is important to note that this is not applicable to everyone that identifies or presents in this way and is instead built upon my own beliefs and interpretations of what I have seen around me.

https://www.usd.edu/diversity-and-inclusiveness/office-for-diversity/safe-zone-training/gender-identity

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

How Indie Beauty Brands Practice Inclusivity

In this edition of Beauty Independent’s ongoing series posing questions to beauty entrepreneurs, we ask 17 brand founders and executives: What is your brand’s approach to inclusivity?

KETHLYN WHITE | COO, Coil Beauty

Our brand was created to give a face to beauty that has not always been considered beautiful. When we create graphics for our marketing, we strive to look for the nontraditional beauties because we know how important representation is to everyone, even on a subconscious level.

One of my favorite things as an adult is to be able to watch a show like "Insecure" or "Black-ish," and say, “Oh, there’s my hairstyle for next week.” As a kid, I was trying to use the Topsy Tail and, if you remember what that is, then you, my friend, are aging gracefully. So, for me, my brand aims to be inclusive of the people who weren’t always included, and I think our website and social media pages do a good job of that. Of course, we are always trying to do more. For us, this is a marathon not a sprint.

ADA JURISTOVSKI | Co-Founder, Nala

We strive to be inclusive of forms of sexual identification, body types, cultures and race. To us, it means being mindful of representation in our brand, but also being open-minded to continually learning about how we can widen that representation. It can be something as detail-oriented as updating our copy from “women” to “womxn,” or deliberate decisions we make such as intentionally having our packaging represent body forms that are fluid, androgynous and ambiguous with the hope that anyone can identify with it and see a part of themselves within the art.

KAILEY BRADT | Founder and CEO, OWA Haircare

Inclusivity has to mean something personally to a founder and, therefore, a brand. I've always been mindful of inclusivity because I've always felt a bit on the outside. It's important to think of inclusivity with a holistic perspective. It's not just about appearance. Inclusivity goes beyond age, gender, ethnicity. I always felt judged without saying a word. As I got older, especially when I first got to college, I felt even more out of place because I was studying engineering and my appearance didn't say "engineer."

My approach to inclusivity is to look beyond the physical attributes of a person and take into consideration their experience, education, career, etc. My approach with our brand is to give real people a genuine voice. I really enjoy working with up-and-coming professionals and giving people opportunities they might not have been given otherwise. I know others who have done this for me in my career, and I wouldn't be where I am today if people didn't believe in me and present me those opportunities that challenged the norm.

RANAY ORTON | Owner, Glow by Daye

My approach of being mindful of inclusivity in my brand is to try and create multiple physical avatars of my customers. Many books and experts say to have one exact avatar, an icon or figure that represents your key demographic. Well, the reality is that, yes, you can have a go-to person in mind for key decision-making on your brand and it's positioning, but all your customers do not look alike.

People want to see some physical resemblance of themselves when they see your website, marketing and social media. As a company, we have to be conscious of that as we serve many different people with different ethnicities, hair types/textures and/or complexions, but all have the same goal of achieving healthy, thriving hair.

PAAYAL MAHAJAN | Founder, Essential Body

Inclusivity is not just a term for me. I am a brown woman who has faced a lot of discrimination while living and working in the U.S. I have faced assumptions around my background with no thought or interest in where I come from or what my heritage is. I have dealt with the blows of white privilege in the workplace and personally. I was also judged for my size for a majority of my life. I am someone who has fought and continues to fight for the rights of the marginalized and oppressed.

I am not interested in tokenism. I smell it from a mile away. You can’t fake your way into being inclusive. My authenticity and my voice are the most powerful ways for me to communicate that my brand is me, and it espouses my values and my perspective on the world. It never was, and is certainly not enough now, to do a rainbow of ethnicities in your imagery. I see brands appropriating cultures, not giving thought to messaging and imagery. None of that is for me. You can’t be mindful of inclusivity unless you fundamentally shift your mindset. This is not something businesses can phone in.

ADA POLLACEO, Alchimie Forever

We strive to be inclusive in everything we do. From the people we use in our marketing materials (fun fact: They’re all family members, team members or friends.) to the way we train our brand ambassadors, we focus on skincare concerns rather than gender, skin color or other identifiers. We don’t say, “Hey, we’re inclusive." Rather, we strive to behave in a way that makes everyone feel welcome and comfortable, and that our products were made for them.

KATONYA BREAUX | Founder, Unsun Cosmetics

As a black founder and consumer, I have firsthand knowledge of what it feels like to not be considered by companies providing skincare and makeup products. I wanted to make sure that not only women that looked like me, but women in general had the benefit and knowledge that there is a product that is made with them in mind, and not only as an afterthought. In this very inclusive environment, the companies that aren't getting on the bandwagon are the ones that are standing out.

NISHA DEARBORN | Founder and CEO, Fresh Chemistry

I teach my kids that the only difference between skin of different colors is the amount of melanin in it. As a daughter of a dermatologist, I can attest to this very simple, yet still profound truth. So, when it comes to my brand, I choose models or repost user-generated content that represents who the freshly activated serums are best suited for: all skin types and colors.

JULIE PEFFERMAN | Founder, The Lab and Co.

We have always thought about inclusivity from the customers perspective and our employee perspective. In the near future, inclusivity won't be a buzzword. Instead, it will be something every brand must do. It will be the authenticity that inclusivity is delivered that will distinguish us from the rest.

On the employee internal side, since we are a lab, it makes sense that our one-word company philosophy is "mix," which guides us as we grow. Mix in kindness in everything you do. Mix with other kinds of people/thinkers to expand your mind and life. When something isn't working, mix it up with a new approach. There is always a way. Work hard, take pride in what you bring to the mix. Take the risk, failure is valued, speak up and mix in your ideas, and see what bubbles to the top.

On the customer side, we try to rethink target customers and find meaningful ways to include others. Our brand, Cleantan, was the first self-tanning brand to showcase full-figured models of various skin colors. We encourage people to be as tan as they want to be with our color controlling concentrate. Our brand Equal By Nature was birthed out of inclusivity, encouraging everyone to celebrate their differences. We aim to create luxurious hero products that fit into anyone's routine at a reasonable price. We call it inclusive luxury.

AMBER FAWSON | Co-Founder, Saalt

Inclusivity is a central and all-important topic in the world of period care. It is actually one of the reasons we love period care. There is something about period talk that brings people together regardless of background or belief. We all share struggles with period management. We all agree that no one should feel confused and alone about their period and their body. We all agree that we want students around the world to have period care that allows them to attend school when they are on their period.

At Saalt, we believe in being period positive and, by focusing on period positive topics, we can do some incredible things with the help of our audience. Our audience helps us break stigmas and also connects us with impact organizations who are doing incredible work around the world. Every part of our brand is about being welcoming and adding people to our tribe regardless of any variety of personal backgrounds or beliefs.

MELISSA REINKING | Chief Marketing Officer, BioClarity

We always try to stay grounded in knowing that the consumers who discover us all have different starting points and skin goals in mind. Step one to being inclusive is being individualized. If we can help people get to where they want to be by understanding their individual needs, desires and starting points, and if we can customize their experience around these attributes, not some idealized version of what we think a consumer might need, this helps us remain not only inclusive, but also very mindful of the evolving needs of those who become part of our brand.

BRANDON GARCIA | Co-Founder, Mira

My co-founder Jay Hack and I wanted to ensure that anyone, no matter who they are, what they look like or what their interests are is able to find what works best for them. The incredible diversity of beauty consumers has driven not only the increased fragmentation of beauty products and trends in the industry, but also the heightened demands for personalization.

Diversity and inclusivity are not only baked into our very core, but they are also the primary factors driving the need for a platform like this. We've worked hard to build an expansive data catalog of over 60,000 products and millions of reviews and videos that can be leveraged to help consumers from all walks of life find what works for them.

In the long term, we hope that it becomes a platform for beauty brands, content creators, and consumers to engage in authentic, meaningful conversation. By doing so, we seek to help advance the industry in co-developing products that best speak to the amazingly diverse individuals that comprise the beauty community.

RENAE MOOMJIAN | Founder and CEO, NipLips

We are vocal in all touch points with our community that everyone is welcome. Whether it is a photoshoot, new brand ambassador or activity, we are continually looking for ways to bring diversity in race, ethnic background, religion, sexual preference, sexual indentification, age, size (large to small and everything in between) into our brand.

Our company tag line is “Beautiful, Authentic You!” and our goal is to help people look within to define not only their unique beauty, but who they really are at their core. So, for example, by using our app, doing a color scan of your nipples, and matching to one of our vegan, organic, lip colors, you are using your body to define what looks good on you rather than social media or celebrities. True beauty and inclusivity starts with embracing your uniqueness and, then, sharing it with the world. We work very hard to promote that message.

FEISAL QURESHI | Founder, Raincry

My personal view is that beauty is not real, it doesn't exist. It's all perspective. That perspective evolves, changes and means different things to different people at different times in our lives. Just look at the 80s. We looked ridiculous, but were full of confidence.

So, beauty is not about the things we buy or how we look, but rather how that thing makes us feel when we wear it, use it or experience it. Therefore, beauty is about emotions and, as a beauty brand, you become a custodian of those emotions to help better people's lives.

KRISTEN BOWEN | Founder & CEO, Living The Good Life Naturally

My entire life I have been on a diet or searching for the perfect diet. I just wanted to be skinny and equated that with being healthy. I will never forget the day that I was sitting in my wheelchair feeling pretty sorry for myself and wondering if I would ever feel good again. A friend walked up and asked me how I was doing. Instead of the usual, “Oh, I am fine,” I answered her honestly. “I am so tired of being sick and having seizures and stressing my family out.”

She looked at me and said something that would shatter and change the course of what I was searching for when it came to my health. She patted my leg after I told her how tired I was and replied, “But Kristen, at least you are skinny.” I had achieved my lifelong dream of being skinny, but it was not what I wanted. I wanted vibrant energy.

Now, when clients start to work with me, I ask them to write out what healthy looks like to them. That way they have a specific goal in mind of what they are wanting to create. Because of that one exchange, we make sure to include all body types in our marketing. Being healthy is so much more than being skinny.

JEAN BAIK | Founder and Creative Chief Officer, Miss A

One of our biggest missions as a business is to #justhavefun with makeup and beauty. So, we always offer as many shades as possible and offer products that would work for a young teen all the way into late adulthood.

JASMIN EL KORDI | CEO, Bluelene

Cellular health is gender, age and ethnicity neutral, and our brand reflects that philosophy. We ensure that our packaging and messaging appeal to a wide human audience, and that we incorporate that variety into the imagery we use.

Source: Beauty Independent

#beauty#cosmetics#makeup#beauty industry#beauty brands#skincare#inclusivity#makeup lovers#beauty lovers#entrepreneur

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

Intersex people are born with chromosomal, hormonal, gonadal, or genital variations that differ from social expectations of what male and female bodies should be like. Even as we begin or continue to challenge binary understandings of gender and sexuality in the anti-violence movements, many of us have not stopped to question the assumption that there are only two biological sexes – and anything else is not “normal” or acceptable. Social discomfort with this aspect of human diversity has resulted in discrimination and marginalization of intersex people, including medically unnecessary surgeries that they have not consented to.

While there has been a shift away from seeing intersex conditions as a problem to be dealt with medically (a practice that became popular in the medical community in the 1960s), these types of unwanted “corrective” surgeries do continue today. Adults who have experienced these medically unnecessary surgeries, also known as Intersex Genital Mutilation (IGM), experience trauma common to many adult survivors of child sexual abuse. The impact of such surgery includes shame, stigmatization, physical harm, and emotional distress. Anti-violence advocates should be prepared to provide trauma-informed care to those who have experienced trauma surrounding IGM.

As you reflect during Pride Month on your efforts to reach out to LGBTQ+ communities, consider ways you can increase your capacity to meet the needs of intersex individuals who may be dealing with trauma related to IGM.

Intersex Community & Inclusion

https://youtu.be/cAUDKEI4QKI

There is great diversity of experience in the intersex community, and diverse ways intersex individuals think about community, activism, needs, and goals. There is also a wide-ranging response to whether or not intersex people should inherently be considered part of the LGBTQ+ communities. One reason that someone might take the position that intersex identity is not part of LGBTQ+ communities may be the opinion that LGBTQ+ movements have, at least in recent history, been primarily concerned with relationship recognition and concerns around identity, and not as much with bodily autonomy.

On the other hand, including intersex as part of LGBTQ+ communities can lead to more visibility of intersex experiences, and can address a common root cause of discrimination: harmful adherence to the gender binary and related gender norms. Writer and intersex advocate Hida Viloria makes this case in the article The Forgotten Vowel: How Intersex Liberation Benefits the Entire LGBTQIA Community:

“When we recognize the rights of intersex people to have their identities recognized, we dismantle the very foundation of the binary sex and gender system which has harmed LGBTQIA people for centuries.”

For more reading on this topic, check out this blog post by Viloria and another intersex activist, Dana Zzyym, which explores many of the diverse ways intersex individuals approach issues of identity.

Note the distinction between being transgender and being intersex. Being transgender has to do with having an internal understanding of one’s gender that is different than what was assigned at birth. This assignment typically has to do with the external anatomy – babies with a vagina are assigned female at birth and babies with a penis are assigned male. A transgender person has a gender identity that is different from that assignment, whether female, male, non-binary, or other genders.

People who have intersex conditions, though, have anatomy that has not been historically considered by societies to be typically male or female. An intersex individual may be transgender, but the majority of intersex individuals do not identify as transgender, and the majority of transgender individuals do not identify as intersex.

Living at the Intersections

Intersex people of color are disproportionately impacted by physical, psychological, and medical violence. Historically, people of color have faced unspeakable atrocities including exploitation at the hands of the medical industrial complex. Activist Sean Saifa Wall reflected on these intersecting identities in a recent interview with NBC:

"I draw a very distinct parallel between how the medical community has inflicted violence on intersex people by violating their bodily integrity, and how state violence violates the bodily integrity of Black people… My desire for intersex liberation is totally [entwined] with Black liberation. They cannot be teased apart.” (2016)

Additionally, intersex activists and survivors of color are marginalized within the intersex movement itself – facing underrepresentation in leadership roles, lack of visibility and voice in public spaces, and limited opportunity to engage with other intersex people of color.

By honoring and lifting up the unique experiences of intersex people of color, by asking them what they need to feel heard and to feel safer in our collective spaces, we can build a more intersectional, anti-racist, trauma-informed movement. For more information, read the Statement from Intersex People of Color on the 20th Anniversary of Intersex Awareness Day and the Intersex People of Color for Justice Statement for Intersex Awareness Day (IAD) 2017, which emphasizes, "We are a just movement that has our vision set on attaining bodily autonomy for all."

The Experiences of IGM Survivors

To explore what intersex advocates are saying about intersex genital mutilation, check out this video from Teen Vogue in which three intersex advocates address what some forms of IGM specifically entail, and how they’re unnecessary and nonconsensual.

One of the advocates in the video, Pigeon Pagonis, discloses the experience of having the clitoris removed, and later having a vaginoplasty at age 11. Pagonis makes the connection that one of the underlying reasons for these operations was to make the vagina “more accommodating to my future husband’s penis” – underscoring one example of how harmful societal assumptions about what male and female bodies should look like (and how sex should happen between men and women) forms justification for these invasive medical surgeries. One of the other advocates in this video, Hanne Gaby Odiele, helps make the connection to trauma, by claiming, “Those surgeries need to stop because they bring so much more complications and traumas.”

A 2017 report from Human Rights Watch called “I Want to Be Like Nature Made Me”: Medically Unnecessary Surgeries on Intersex Children in the US contains information on the history and impact of IGM, including insight into the trauma mentioned by Odiele in the video. In one testimonial from an adult survivor of intersex genital mutilation, Ruth, age 60, shares: “I developed PTSD and dissociative states to protect myself while they treated me like a lab rat, semi-annually putting me in a room full of white-coated male doctors, some of whom took photos of me when I was naked.” The report goes on to illustrate forms of psychological harm and emotional distress that adult survivors of intersex genital mutilation may experience.

When working with a survivor of intersex genital mutilation, consider that control was taken away from the survivor in the nonconsensual, medically unnecessary surgery. These surgeries may receive legitimacy simply because they take place in a medical context, which we tend to view as being associated with consent and authority. But the root of the perceived “need” for this surgery is embedded in social standards about what male and female bodies should look like, not medical need. We need to move away from the notion that there might be an underlying medical justification for this abusive touching (Tosh, 2013).

Shifting Our Culture

Working to end false binaries of sex, gender, and sexuality can be an important first step in preventing IGM and many forms of violence. Developing an understanding of intersex peoples’ experiences by reading intersex history and listening to intersex people share their stories when offered can deepen your understanding of who is part of our communities and how we can provide trauma-informed care to everyone who needs our services. A first step can be to become familiar with intersex organizations like Intersex Society of North America, interACT, and Intersex Campaign for Equality. Another can be to educate colleagues on trauma related to IGM, and to make efforts to directly engage the community in which your agency wants to provide welcoming and relevant services to intersex people. Shifting our culture to end the shame, secrecy, exploitation, and abuse of intersex people will require broad level systemic change driven by all of us.

What can you do to positively impact the lives of intersex survivors in your community?

References:

Human Rights Watch, interACT. (2017, July). “I Want to Be Like Nature Made Me”: Medically Unnecessary Surgeries on Intersex Children in the US. Retrieved from https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/report_pdf/lgbtintersex0717_web_0.pdf

Tosh, J. (2013). The (In)visibility of Childhood Sexual Abuse: Psychiatric Theorizing of Transgenderism and Intersexuality. Intersectionalities: A Global Journal of Social Work Analysis, Research, Polity, and Practice. Retrieved from http://journals.library.mun.ca/ojs/index.php/IJ/article/view/739/743

Image from InterACT Advocates for Intersex Youth.

256 notes

·

View notes

Text

An analysis of Bill Clinton and the Cultural Wars that shaped him and influenced the 1992 election.

*this is a topic I find really interesting and it is a quick informative amateur post which is just my interpretation. Of course, I am condensing it and not putting everything in here*

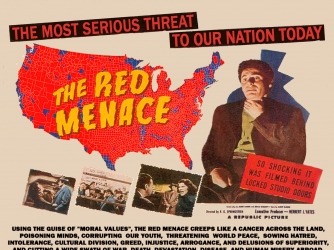

Bill Clinton was born in 1946, after the Second World War and during the time in which the Second Red Scare had begun in the United States. Given that during the Red Scare, tensions with the Soviet Union were at large and the United States Government tried to seek out Soviet spies, there became a definition of what it meant to be “a true American.” This can be seen in that this was also the age of McCarthyism, where Senator Joe McCarthy tried and accused many American citizens without regard to evidence. Senator McCarthy spent almost five years trying in vain to expose communists and other left-wing “loyalty risks” in the U.S. government. Many thousands of Americans faced congressional committee hearings, FBI investigations, loyalty tests, and sedition laws; negative judgements in those arenas brought consequences ranging from imprisonment to deportation, loss of passport, or, most commonly, long-term unemployment. It is no secret that immigrants were targeted, civil rights activists, and people of color in general (as well as the LGBTQ community) This is due to the fact that they were an easily defined “other” and previous paranoia of the Japanese Empire and the attack on Pearl Harbor had already stigmatized anyone who didn’t appear to be a White American.

This was the root of the Culture War that would define Bill Clinton and come to full form in the 60s because though McCarthyism died out around 1957, it contributed to the uniformity of the 50s and the culture. This is due to the fact that many people tried to prove themselves American enough and they did this by conforming in a way in which they deemed standard for all Americans to behave. During the 1950s, a sense of uniformity pervaded American society. Conformity was common, as young and old alike followed group norms rather than striking out on their own. Though men and women had been forced into new employment patterns during World War II, once the war was over, traditional roles were reaffirmed. Men expected to be the breadwinners; women, even when they worked, assumed their proper place was at home. Sociologist David Riesman observed the importance of peer-group expectations in his influential book, The Lonely Crowd. He called this new society "other-directed," and maintained that such societies lead to stability as well as conformity. Television contributed to the homogenizing trend by providing young and old with a shared experience reflecting accepted social patterns.

What McCarthyism and the 1950s deemed as a “true American” consisted of these traits:

Being White

Following traditional gender roles

A pride in the military and serving in war (this is due to the pride and support of WWII).

This became the common theme of the 1950s and became known as the “conservative culture”. Though rebellion against these norms came into play in many ways, music is one example: ll. Tennessee singer Elvis Presley (it should be noted that Bill identified with Elvis and enjoyed his music). popularized black music in the form of rock and roll, and shocked more staid Americans with his ducktail haircut and undulating hips. In addition, Elvis and other rock and roll singers demonstrated that there was a white audience for black music, thus testifying to the increasing integration of American culture, this served as a foreshadowing to the culture wars that would come to light in the 60s.

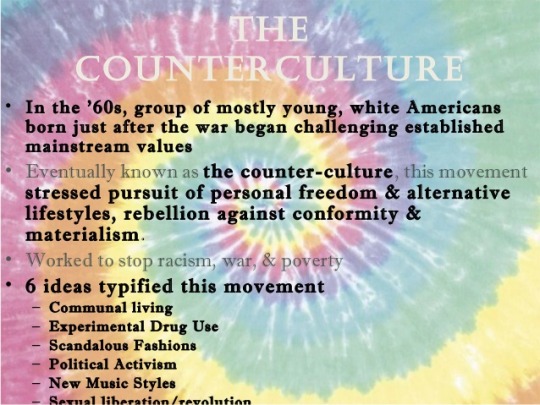

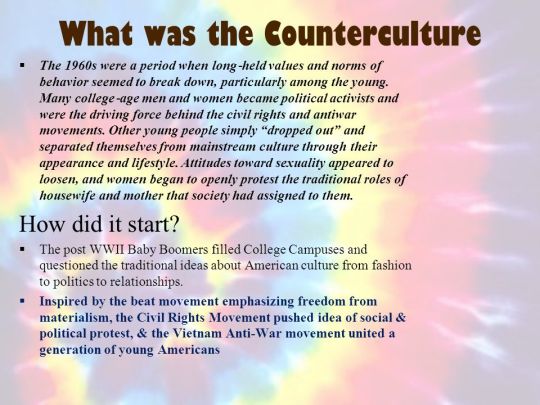

The Baby Boomer Generation became the “counterculture” in many ways going against the norms set by the “conservative culture.” This can be seen that in the 60s movements by marginalized groups suppressed during the McCarthy and 50s era, gained more support amongst young people.

How Bill Clinton was shaped by The CounterCulture: Like many, Bill Clinton was influenced by the Counter Culture and became a part of it. This can be seen in his admiration of Martin Luther King support for Civil Rights, and his opposition to the Vietnam War.

How this influenced the 1992 election:

George H.W. Bush belonged to the generation that lived through WWII and supported the conservative culture that was the norm in the 1950s.

Bill Clinton belonged to the baby boomer generation and the Counterculture that took place in the 1960s that rebelled against the culture of the 1950s.

The 1992 election was very much representative of the “conservative culture” vs. the “counterculture” war that had happened between the two cultures in the 60s.

This can be seen in how the candidates spoke of one another and the issues that were brought up in the election.

The main issues that were discussed were character, moral values, and service in the military.

1. The issue of character shows how the 1992 election was representative of a cultural war. George H.W. Bush’s strategy was to portray Bill Clinton as a promiscuous, pot-inhaling, stereotypical hippie. Though Bill Clinton was rather promiscuous in his youth, the fact that Bush chose to highlight on it was evident of a cultural war being present in the election because it fed into the 1950s norm that sex should be reserved only for marriage, in contrast to the counterculture 60s trait of sexual liberation. The issue of pot was also evident of a culture war in the election because again this fed into the 1950s conservative culture norm that recreational drug use was bad under any circumstance, vs the 1960s counter culture trait of experimentation with drug use. Remember Bill Clinton’s iconic quote: “When I was in England, I experimented with Marijuana a time or two and I didn’t like it, and I didn’t inhale and never tried it again.” This fed into the hippie stereotype and though while it is hard for some to imagine now, many of those who belonged to the older generation “looked at Bill Clinton and saw every hippie they ever wanted to sock in the jaw.” In the same way, Bill Clinton portrayed Bush as stagnant and unchanging, a product of the 1960s counter culture where the youth felt that the government didn’t do enough or progress enough change.

2. The issue of moral values also demonstrates how the 1992 election was influenced by the conservative culture vs. counter culture war. This can be seen in the attacks on Hillary Clinton and family values. The Bush campaign often attacked Hillary’s previous work as a lawyer. This demonstrates how the election was influenced by the culture wars because the Bush campaign was sticking to the traditional gender roles of the 1950s society where “women, even when they worked, assumed their proper place was at home.” Hillary being very independent and outside of the home represented the 1960s counter culture trait in which women began to liberate themselves more and were free to both work and be involved in domestic life and not have to choose between one or the other. The Bush campaign also criticized Hillary’s active role Bill’s campaigning.

3. Service in the military. Perhaps the most distinct and demonstrative issue on how the conservative and counter culture came into play in the 1992 election, this was significant because Bill was the first president in several years who had not been alive to witness WWII. So naturally when it came to light that Bill had been opposed to the Vietnam War, the Bush campaign jumped on this. This is due to the fact that Bush, having served in WWII, could not understand Bill’s opposition to the Vietnam war. Bush himself even said in the 2nd debate “I don’t know if that’s a generational thing or what,” when describing anti-war protests American students would go to abroad. This demonstrates the cultural wars influence because it was very WWII generation vs. the counter culture generation of baby boomers because they were seeing the wars from a different perspective. The WWII conservative culture saw military service as something to take pride in and that all wars were just. While the 1960s counter culture questioned the government’s involvement in Vietnam.

In conclusion, despite this cultural war Americans aged 60 and over showed a clear bias in favor of Bill Clinton, according to the polls. He also ran well among other demographic groups, including half of the military veterans, (despite the furor over his draft status during the Vietnam War), half of the first-time voters, and more than half of union members.

Of course there were other influences in the 1992 election and other factors that influenced Bill Clinton but the culture wars of the 50s-60s really did shape his political beliefs and eventually his run for the presidency.

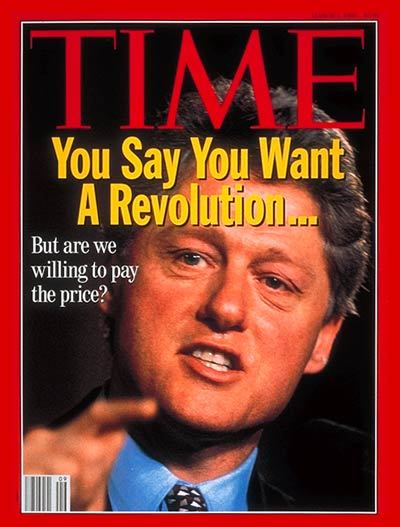

Bonus: This is my favorite magazine cover of Bill because it makes reference to the 1968 Beatles song ‘Revolution’ which came out while Bill was in college and the Beatles were a very counter culture band:

#i checked for typos but the semester is over and my brain is fried so sorry if there is#this is like my favorite thing ever to talk about though so I made a post on it#bill clinton#1992 election#wjc#William Jefferson Clinton#president of the united states#president clinton#60s#50s#the clintons#billclinton#history#american history#american presidents

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gods

Religious Worlds (1994)

“This book is a good introduction to the phenomenology of religion. Stressing that religions are not just systems of belief, but forms of behavior…William E. Paden focuses on four key complementary categories: myth, ritual, gods and systems of purity.”

This book is something of a landmark work within its field. "From gods to ritual observance to the language of myth and the distinction between the sacred and the profane, Religious Worlds explores the structures common to the most diverse spiritual traditions.” In other words, Paden is studying the concept of religion itself and how it manifests across the spectrum of available world religions. He is not surveying what individual religions have to say and then comparing his findings to find a right one. Paden asks questions like: What function do rituals serve across all religions? And, what about sacred writings and histories (properly called "myth" within comparative religion); how do these shape and fashion religion?

From his perspective, Paden is attempting to let each religion speak on its own terms and simply listen to what each is saying. Paden seeks to classify these facts, or "phenomena," in the search for religious structures, or "forms of expression," from any emerging patterns. Throughout the process, respect must be given to each religion's complexity of contexts (geographic, historical, sociological, etc.); each one sees the world in its way because of these dynamics, what Paden calls a "religious world," and engages the world accordingly. Only when we shed our "religious world" and enter into those of others can we truly understand them. Finally, Paden also stresses sensitivity for the sacred while surveying religions to help discern what is religious by nature. His goal is to understand and survey each world's respective landscape in a spirit of tolerance and diversity, and let the reader evaluate from there as necessary.

William E. Paden University of Vermont, Professor Emeritus

Area of expertise: Cross-cultural patterns of religious behavior.

Professor Paden had been a member of the Department from 1965 until his retirement in the spring of 2009. He served as Chair from 1972-78 and 1990-2005. His M.A. and Ph.D. (1963, 1967) in comparative religion are from Claremont Graduate University, and his B.A. (1961) from Occidental College (philosophy). He has been a visiting scholar at Wolfson College, Oxford (1999, 1992), and spent time as a research fellow and lecturer in Japan (1999, 1992).

Contents

Preface to the 1994 Edition vii

Preface to the 1988 Edition xiii

Introduction 1

One: Religion and Comparative Perspective

1 Some Traditional Strategies of Comparison 15

2 Religion as a Subject Matter 35

3 Worlds 51

Two: Structures and Variations in Religious Worlds

4 Myth 69

5 Ritual and Time 93

6 Gods 121

7 Systems of Purity 141

8 Comparative Perspective: Some Concluding Points 161

Notes 171

Index 187

Preface to the 1994 Edition

In the five years since Religious Worlds was published, the need to understand the plurality of culture and religion has become even more apparent. Issues of pluralism indeed seem to have become part of the tasks and riddles of civilization itself. The profound differences between human worldviews have not been erased by information technology or international business networks, with their appearance of having so easily unified the surface of the globe. Beneath the surface, the earth is still a patchwork of bounded loyalties and hallowed mythologies, a checkerboard of collective, sacred identities. The theater of ethnic and religious diversity has not gone away. The variety of human worlds, with all their conflicts, is still there despite the facade of unity.

Pluralism refers not only to cultural diversity but also to the many kinds of “knowledges” or lenses humans use to perceive and construe their universe. With increasing clarity we see how inevitably the world forms itself according to our different frames of reference. A chemical lens will only register a chemical world; a poetic lens uncovers a poetic world; a religious lens yields a religious world. These multiple frames whereby telescopes picture the universe one way and religious symbols picture it another simply coexist. Alter the lens and you alter the data; change the receiving channel and you change the program; switch groups and you exchange one world for another.

Models of knowledge based on an exclusive, privileged, single lens—whether that of the sciences or the religions or white middle-class Americans—have come under challenge. In a new, pluralistic setting, in this new openness to the many architectural possibilities of what we take to be the world, the study of religious diversity has a definite role to play.

When in 1963 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against the practice of prayer in public schools, it advocated at the same time that the comparative study of religions should be an indispensable part of education. Yet the study of religion has long been controlled by what might be called the interests of private ownership, that is, the religious groups themselves, so that the subject matter of “the gods” has until recent times lacked an appropriately unbiased vocabulary parallel to those in the study of the physical and social worlds. There cannot be a study of religion that is not at the same time the study of all religion, just as one cannot have a “geology” based only on impressions of the rocks in one’s backyard. Religious Worlds, which works at broadening, purging, and reshaping our otherwise provincial language about religious life, is a small contribution to this new globally oriented era of religious studies and I am gratified that it has found a wide readership in college classes and in Japanese and German translations.

I continue to be impressed by how useful, synthesizing, and far-reaching the concept of “world” is as an organizing category for the study of religion. “World” is not just a philosophical abstraction nor a word for the endless galactic stardust. In more human, experiential terms, it is an actual habitat, a lived environment, a place. It is what we need to understand about others in order to understand their life and behavior.

A “world” is the operating environment of language and behavioral options that persons presuppose and inhabit at any given point in time and from which they choose their course of action. The term has enough flexibility to refer to the scripts and horizons of an entire culture, a subculture, or an individual. Within a single tradition like Christianity, there are thousands of religious worlds, because of the many ways they are packaged by cultures and history. “World,” then, becomes a tool for getting at the shaping power of context in the fullest sense of the word, and the idea of multiple worlds helps us to recognize and take seriously the distinctive life-categories of the insider, however different they may be from our own.