#and the serpent motifs are clearly visible

Text

Coming up with Athena's design. Not the final result but definitely the start

#hope she looks like an owl#and the serpent motifs are clearly visible#not only with her cloak but bracelets as well#greek mythology#ancient greek mythology#greek myths#athena#greek gods#ptero art#art

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

talking abt wigfrid and critisism but the further you go the less coherent it becomes. no i will NOT simplify it. read my flop analysis boy.

Something very interesting about Wigfrid that I don't really see in characterizations a lot is the concept of her having... I don't really know what to call it. Not 'a thinner skin', but I suppose the concept of her being wary of how people perceive her.

A lot of interpretations of Wig that I see tend not to go beyond the surface of her persona, that being a confident and overzealous warrior. And to an extent, that is what she is. But I also feel as though it's very important to her character to consider how she got to embracing that persona the way she has to begin with.

'Wigfrid' the actress- whoever she may have been- was clearly incredibly concerned with how she was perceived by others... Most of them being complete strangers to her- people who she'll never meet or get to know, who will never know her in turn. Hell, the opinions of those strangers were the driving force to her accepting Maxwell's deal to begin with! Yes, she wanted her popularity back, but were it not for the people who tore her down with their words alone, she never would have lost it to begin with!

I think the snake motif in Curtain Calls was a very interesting choice for Klei, if only because to me it feels deliberate. The giant serpent she fought within her fantasies manifested itself from her newspapers... The term 'snake' is frequently used to describe individuals who are deceitful and dishonest. To me it doesn't really feel like a coincidence that- of all the beasts, that is the one they choose. A creature who's very title is a double meaning, used to represent the critics who so viciously tear her down, fangs dripping with venomous lies that she can only fight against within the safety of her mind.

"Oh, Savvy-" I can hear you cry, "-Savvy, I think you're reaching a little bit here". Normally I would be inclined to agree. Very frequently I find myself grasping for straws to prop up Klei's otherwise sparse characterizations. However, if the snakes = liars = critics theory isn't enough on its own, I would also like to remind you of what happens after Wigfrid defeats the snake in Curtain Calls. She falls back into reality at the sound of a disembodied voice, and from the newspapers manifests a silhouette of Maxwell. A direct parallel to her fantasy, the news has yet again taken the image of a 'snake'... Of a deceiver. To me, that seems incredibly intentional.

NOT TO MENTION that if the theory is true that MAXWELL MADE UP THE NEWSPAPERS TO BEGIN WITH in an attempt to emotionally manipulate her, then the snake metaphor would make EVEN MORE SENSE because he is LITERALLY making himself tangible out of HIS OWN lies. but i'm NOT GETTING INTO THAT RABBIT HOLE right now because i'm ALREADY DIGRESSING!!!!!

So, now that we can ALL AGREE that Wigfrid's hatred of snakes stems from a bit of self projecting, we can bring up Wigfrid's current, in game hatred of snakes, and perhaps draw a couple of conclusions about how criticism may be effecting her now, as opposed to how it was pre-Constant:

Her unabashed hatred is visibly obvious. She goes about engaging with snakes in a VERY unique way she does the rest of her quarry. She takes great pleasure in their destruction, and goes so far as to label them her enemies, specifically. I looked it up, and as far as I can glean this wouldn't be a pre-establised trait of her persona. This vitriolic snake hatred is entirely stemming from the person underneath.

So. With the context we previously gathered that implies that maybe the reason she sees snakes in such a way is due to the fact that they are practically synonymous with critics and 'liars' to her, I can safely conclude that. um. No, I really do not think she has grown any more of a hide against criticism than she had before accepting Maxwell's deal.

Wigfrid's hatred of snakes was a big part of her character from even before Curtain Calls (obviously, bc shipwreck released way before her refresh did), but I feel like them taking this specific facet of her character- one that's lesser known from her, buried behind her more stereotypical motifs- and adding such important context to it was a intentional act. I refuse to think otherwise.

Even outside of the whole. Snake Thing I spent two hours describing, though. To me it still seems plausible for Wigfrid to act all tough, but take insults very poorly. Yes, in a prideful sort of way- where she feels the need to actively defend herself and her 'honor'- but also just in a... regular way. I don't think it'd show up much in the Constant because. i mean, there's more important things for the survivors to do. but i really do feel like scathing insults would bite her more than someone would expect it to.

Also I just think it would be funny and help flesh out her nuance. Is that a crime. To want to give my girl some nuance. Is that a sin.

#wigfrid: when you've been in the industry for as long as i have you develop a thick skin#maxwell: navy blue is *not* ur color#wigfrid: NAVY BLUE BRINGS OUT MY EYES YOU PRICK#anyways. can you tell i've been wanting to talk abt the snake motif thing for like. months.#idk. if this doesn't make sense yes it does.#you don't know her like i do. i know her flawlessly though. klei told me that all this is true btw#also whoever wrote her hamlet quotes and didn't give her vitriolic lines for the pugalisk DROPPED the ball and should lose their job /j#YEAH. i GUESS you could see her snake hatred as stemming from a personal hatred of poison#but not every snake IS poisonous and she hates them all the same#also impo i kinda feel like. poison. is ALSO a metaphor for critics. when u rlly think abt it.#bitter and venomous words. that insidiously sneak into your mind. killing you slowly. and you can't even fight against them.#to 'spit poison/venom' is to speak maliciously/with intent to harm.#would NOT be surprised if thats how she took slights against her#am i making ANY sense here. idk#“dst wigfrid”

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Been thinking about Voyage of the Dawn Treader, and its nature as a story about journeys. Not just the physical journey the ship is on, but the inner journeys each of our main characters experiences. Lewis even described it as a spiritual journey, with Reepicheep as the main example. It’s a pilgrimage that changes each of them.

Reepicheep and Eustace are the most obvious examples here. Reepicheep is questing for Aslan’s Country, and when he reaches it in the end, he throws away his sword, the very symbol of who he is (well, that and his tail), in order to be unencumbered on the final stage.

Then there’s Eustace, who first transforms into the worst version of himself, an literal, physical dragon to match his dragonish inside, and then is transformed by Aslan into a human, whose journey afterward is one of steady upward growth. He’s not magically perfect, but he consistently tries to do better, even if it’s in small ways and even if his attempts fail at times (breaking Caspian’s second-best sword on the sea serpent ...)

But what about the other three? What is their inward journey that matches up with their outward one?

For Caspian, it’s growing into his kingship. It’s learning to accept responsibility. It’s growing less like Miraz, and more like Aslan. We see him in all his pomp and glory in rescuing the other and ending the slave trade in the Lone Islands, but ultimately sailing off and leaving them to clean up after him. Then comes Deathwater, where he falls right into temptation, sliding oh-so-easily into pride, selfishness, and greed. He recovers from that, but the effects linger, leading him to the ultimate struggle as they near the World’s End, when he attempts to abrogate his kingly responsibility in order to pursue a personal quest. Here, the ultimate good for Reepicheep is shown to be not the ultimate good for Caspian--he has to learn how to behave as a king. He is even described as looking like Miraz at one point during the argument, and it isn’t until he sees Aslan’s face that he truly repents and accepts the whole burden of kingship--going back when you’d rather go forward; being responsible when you’d rather have an adventure; following duty even if it means saying goodbye to your friends. That’s Caspian’s journey.

Lucy’s is a bit more subtle. We know that she still “needs” something from Narnia when they arrive, or she wouldn’t have had the adventure. Likewise, we know that she gained whatever it was she needed by the end, or she wouldn’t have been told her time in Narnia was at an end. So what was it? I think it’s fairly obvious that her crisis, the turning point of her journey, came on the Dufflepuds’ Island, with perhaps a secondary crisis at the Dark Island. So let’s look at those.

We see the courage of Queen Lucy the Valiant when she takes the Dufflepuds’ challenge to undo the invisibility spell. And then we see something interesting: she faces an enormous temptation to make herself beautiful/desirable. When she sees Aslan’s face in the middle of the spell, she resists that temptation, but falls to a lesser one, to find out what her friends really think of her. Shortly after that, she makes Aslan visible, shows her true beauty in her joy at seeing him, repents of her wrongdoing, is forgiven and also accepts the consequences. So what’s the underlying theme here? The Disney movie would have it that Lucy needs to love herself. Accepting yourself and not comparing yourself to others is certainly laudable, and certainly Lucy needs to learn the difference between false worth and true worth, but I don’t think that’s the only thing Lewis is getting at here. I think that for Lucy, growing up is bringing a whole lot of new challenges that she hasn’t had to face before, and her particular struggle is seeing Aslan even when it looks like he’s not there. Keeping her focus on him even when she’s tempted to fall into the trap of wanting worldly approval, of finding value in other people’s opinion of her rather than finding her value in Aslan alone. This need to see Aslan even when it looks like he isn’t there is emphasized by the Dark Island, where she is tempted to fall into despair, but retains enough faith to call upon Aslan--and he comes to lead them out of the pit of nightmares. In Prince Caspian Lucy learned to follow Aslan even when no one else could see him: now she has learned to follow him even when she can’t see him.

And Edmund? Edmund is even harder to read than Lucy, in large part because he faced his major spiritual crisis back in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, and he’s only continued to grow in steadfast faith ever since. Yet clearly, as with Lucy, there was something more he needed to take from Narnia before he was ready to leave it behind for his own world. We don’t see much of the story from Edmund’s perspective: when Eustace is undragoned is about it. The only other times he’s not wholly in the background are at Deathwater, on Ramandu’s Island, and chiding Caspian at the end. I will admit it’s difficult for me to pick up on any kind of thread that holds these four instances together. We see him at his best with Eustace, reassuring him and pointing him toward Aslan. He’s at his worst with Caspian on Deathwater, holding his position as one of the ancient Four above the other king’s head. His past with the White Witch makes it hard for him to trust Ramandu’s Daughter, especially with the Witch’s knife reminding him of that past, and then we see him as not a king but a counselor, a mentor, reminding Caspian of his duty, at the World’s End. So what’s Edmund’s journey? The best I can come up with is moving from a kingly role to a priestly role, letting go of past glories to stand as a guide to others; but I’ll admit that doesn’t seem to take into account his discomfort on Ramandu’s Island. If anyone else has any ideas, I’ll gladly hear them.

The other crucial bit about VDT is the sun motif, Sol in the medieval cosmology, that which transforms all baser metals to purest gold. (I am heavily influenced here by Michael Ward’s Planet Narnia.) Even as Deathwater transformed living things to deadly gold, so Aslan’s influence throughout the story transforms all the characters to living gold--people who live in the brightness of the true Sun all the rest of their days. Reepicheep gives up earthly glory for eternal bliss. Eustace accepts the painful transformation offered by Aslan to be reborn into a new person. Caspian lets go of false pride and lust for adventure to become a true king. Lucy turns from false promises of worldly value for the value found in following Aslan. Edmund, if nothing else, becomes a little more like Aslan on this journey.

So it is that the voyage of the Dawn Treader is also a voyage of sanctification for the people aboard it, and that far from being a disjointed series of meaningless vignettes, there is a strong thread of transformation holding it all together.

#narnia#voyage of the dawn treader#cs lewis#whew#this turned a bit more intense than I'd originally expected#and I'm not sure anyone will care but me#oh well#king caspian#queen lucy#king edmund#eustace clarence scrubb#reepicheep

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Trinkets, Rings, 1: Enough rings and bands to wear three on every finger and toe while still having dozens to spare. Rings, especially magic rings are a very common item of jewelry in fiction and roleplaying. From a basic ring of protection, to the life saving ring of regeneration, the ring of the Nibelungs, the rings of the lantern corps, the ring of Gyges, any wedding ring ever depicted, the ring of Solomon, Sir Perceval's ring, Aladdin's genie housing ring, the nine rings of mortal men and the precious one ring of power, these small circular pieces of gems, metal, wood or bone always add more to the story than the sum of their parts. None of these rings are intensely magical in their own right but can serve as basis for a magical or plot relevant ring. When a DM rolls a d100, the bog standard ring of protection +1 they were going to give out now has a unique look and personality rather than just a mechanical benefit.

A gold band with three small glimmering stones set within. Two glow with a faint reddish light while the third glows pale white.

A ceramic ring that causes it's bearer feel as though gentle hands are constantly caressing their body

A burnished silver ring that shows signs of obvious wear and a few nicks and scrapes mar its surface.

A copper ring that feels abnormally light.

A copper ring that makes the bearer’s fingertips glow a barely perceivable green

A copper ring with a flat shield motif, polished to a mirror like state.

A durable ring made of bluish agafari wood

A gold ring that vibrates when the sun rises in the bearer’s location

A golden ring covered with intricate etchings of wind-blown leaves. Worn runes (possibly of Elvish origin) decorate the ring’s inner surface, but what they say is impossible to determine.

A golden ring forged in the shape of a serpent eating its own tail. The serpent is so finely detailed it eyes and fangs are visible as are the tiny scales covering its body.

---Keep reading for 90 more trinkets.

---Note: The previous 10 items are repeated for easier rolling on a d100.

A gold band with three small glimmering stones set within. Two glow with a faint reddish light while the third glows pale white.

A ceramic ring that causes it's bearer feel as though gentle hands are constantly caressing their body

A burnished silver ring that shows signs of obvious wear and a few nicks and scrapes mar its surface.

A copper ring that feels abnormally light.

A copper ring that makes the bearer’s fingertips glow a barely perceivable green

A copper ring with a flat shield motif, polished to a mirror like state.

A durable ring made of bluish agafari wood

A gold ring that vibrates when the sun rises in the bearer’s location

A golden ring covered with intricate etchings of wind-blown leaves. Worn runes (possibly of Elvish origin) decorate the ring’s inner surface, but what they say is impossible to determine.

A golden ring forged in the shape of a serpent eating its own tail. The serpent is so finely detailed it eyes and fangs are visible as are the tiny scales covering its body.

A ring made of old yellowed bone which causes the bearer to reek of rotting fish.

A golden wedding ring with the word “Always” inscribed on the inside.

A metal ring with a crystal that always hovers an inch above it.

A pair of interlocking steel rings that sometimes fuse into one or separate back into two.

A ring carved from a lump of white-flecked granite. The outer edge is jagged and uneven while the inner band is worn smooth through use. It always feels cool to the touch.

A ring of dark blue stone, that glows brightly in misty areas.

A ring that appears to contain a floating human eye.

A ring with a discrete poison reservoir for slipping into drinks and a tiny razor edge for cutting purse-strings

A signet ring emblazoned with the image of a shooting star hurtling downwards. The ring itself is of beaten gold, and the shooting star etching is picked out with silver.

A silver ring inscribed with strange sigils

A silver ring with the name “Aleena” engraved inside.

A silvery ring in perfect condition, its highly polished band glimmers in the light. Tiny esoteric symbols etched into the inner band speak of the union of magic and the natural world.

A sliver ring that always feel slippery, as if covered in oil no matter how dry it is

A small bronze ring that if flicked, will spin on its edge at great speed for precisely eleven seconds, then fall flat.

A small iron ring that causes anyone who touches it to say “Fanoshil”

A small signet ring with the emblem of a bat on it.

A spongy ring with the consistency and texture of flesh. Upon closer examination, small warts and clumps of hair can be seen upon the band.

A stone ring that mildly reduces the wearer’s sense of touch

A thick, smooth platinum ring would be heavy but for the score or so of holes punched through its band. These holes (of many different sizes) are of various geometric shapes. There doesn’t seem to be a recognizable pattern to the holes’ placement.

An ebony ring carved like entwined vines. If exposed to water the ring sprouts tiny green leaves.

An engagement ring that always looks vaguely familiar

An iron ring bearing a small rent in its side which almost split the band in twain. The repair (while not crude) is clearly visible.

An iron ring that shines brilliantly despite being completely rusted.

An iron ring that, when worn, makes the wearer feel calm.

An unassuming black ring with a small poison reservoir for slipping into drinks and a tiny razor edge for cutting purse-strings.

An unbreakable, glass ring

A small gold ring set with a magical stone that dimly glows any color the bearer desires.

A bone ring set with a preserved and shrunken eye of a Random Color

An iron band flecked with onyx pieces that's always cold to the touch

A ring crafted from what appears to be fresh rough-cut bark. The smell of conifers and fresh pine sap constantly emanates from the band.

A black steel ring with a pair of demonic eyes etched on the interior of the band

A multicolored cloth ring seemingly created from several twisted scraps of clothing.

A pewter ring with an inlaid gold band that slowly rotates

A gold ring crafted to look like the royal crown of the local kingdom.

A Randomly Colored glass ring that when worn, teleports from finger to finger at random

A signet ring bearing an unidentifiable seal

A signet ring depicting the seal of one of the PC's distant ancestor's

A single setting holding an overly large crystal which dominates the otherwise plain, but exquisitely forged ring. The crystal glows with faint red, blue and yellow hues.

A small gold ring set with a magical stone that dimly glows any color the bearer desires.

A pale ring set with a piece of a viper’s fang. A quiet hissing sound occasionally emanates from it.

A gold ring with green enamel, worked in the shape of leaves

A golden ring affixed with a dark stone chiseled into a cat’s head. It purrs with pleasure and graces the bearer with euphoric sensations whenever a creature with canine blood is slain in its presence

A silver ring flecked with gold, with the final line of a well known poem engraved around the outside. The inside edge has a small spike which pricks the bearer's finger while the ring is worn.

A golden ring with three links of golden chain attached to it. The end of the chain holds a small emerald, with an ancient rune expertly carved into its largest facet.

A mithril ring bearing a miniature figure of wizard standing upon it. Deft fiddling will reveal that the wizard’s hat can be turned, and removed, revealing a small diamond within the figure’s head.

A glass ring which appears, in most respects very plain, However, when light is shone upon it colors weave and dance within the clear glass.

A black ring of an unfamiliar material, which has a large seal on it depicting a droplet falling into a small puddle. The substances being depicted are unclear.

A hollowed ring of transparent glass. The band is filled with water which flows clockwise around the band. Flecks of gold in the water dance and twirl in the ring's current.

A copper ring, with depictions of scales embossed around its edge.

A smooth ring of silver with a band of gold approximately half the ring’s width inlaid around the center of the ring’s outside edge.

A steel ring with several cogs built into it. These cogs are interlocking, and spin freely but have no obvious mechanical purpose.

A gold ring which splits into two bands at the crest, with a darkly tinted lens mounted between them.

A pair of twisting bands, one silver, one gold. Each wraps around the finger twice, forming a single ring.

A red copper ring, masterfully crafted to look like a fox wrapped around the bearer's finger. It has emeralds for eyes and a tail which extends back along the bearer's finger.

A square gold ring with a ruby on each of the four corners. The flat edges fit snugly around a finger.

A ring formed from an arm of gold, clasping an arm of silver, clasping an arm of copper, which in turn clasps the arm of gold.

An ivory ring carved to look like a single long finger, wrapping around in a full 360 degrees.

A ring consisting of interlocking iron bands displaying a speckled purple sphere inset.

A ring constructed of intricately curving strands of silver, supporting a flat skull of jade, painted with bright colors and wearing a large grin.

A gold coin of an ancient empire mounted on a golden ring.

A strand of steel shaped like an arrow and twisted into a ring.

A mithril ring, the exterior of which is covered in dozens of tiny spikes. In the center is a small, ocean blue sapphire, at the center of which is a tiny white sphere. It’s unclear what the sphere is and how is was placed within the gem.

A platinum ring with numerous small images engraved on its outer band. They depict a woman in many stages of life. Being born, learning to walk, growing into a woman, fighting mighty battles, bearing children, growing old, and finally dying. The last phase of life connects seemliness with being born again denoting an eternal cycle of life.

A jade ring whose signet is an elaborate flower, made of numerous gems. Rubies and sapphires make two layers of petals, wrapping around a large amber stone in the center. Within the amber is a petrified bee.

A delicate brass ring shaped to look like a feather, bent so the end of the vein meets the quill.

Carved from ivory, this ring looks like a tiny dragon’s skull with the wearer’s finger going through the skull’s mouth.

A delicate ring carved from platinum to resemble a royal tiara, which fits around a finger instead of a head.

A wooden ring, thick with bark on the outer band. At the crest of the ring, where a gem would normally sit, grows a thick pad of damp moss.

A smooth ring carved from jade with two arms extending from its crest. Between their hands, the arms hold a small ball of glass.

A red stone on whose crest perches a miniature bird exquisitely carved from sapphire.

A pair of iron rings connected by a chain of finest mithril, that are meant to be worn on adjacent fingers.

A simple silver ring with braid embossed around its edge.

A shiny silver ring with a large concave plate in place of a signet. The surface of the plate is bare, save for a ring of tiny obsidian stones around the inside edge.

A ring carved from marble with engravings of a crown, a sword, and a bull’s head along the outside edge. On the inside of the band written in ancient common is the phrase “Power through adversity.”

A gold ring with two large bumps on it, each covered in hundreds of diamond flecks. The bumps appear to be modeled after an insect’s compound eye.

A ring carved from jade depicting a mighty tiger which wraps around the bearer's finger, and bites its own tail.

A sparkling ring carved from a single large sapphire. At the crest of the ring, a tiny copper ship rests, as though it were drifting on a sapphire sea.

A black steel ring resembling a spider laying dead on its back, its eight curling legs clasp tightly to a white pearl.

An iron ring graced with the widely grinning countenance of a goblin lord. The face's wide smile sports three small rubies in place of teeth.

A mithril ring consisting of two circlets attached together by a long, articulated piece of mithril artistry, made to look like the top side of a dragon’s talon. When worn, this will cover the wearer’s entire finger.

A silver ring bearing a pyramidal obsidian inset which is held in place by four demonic claws, one from each corner of the square.

A bizarre platinum band is a sort of reverse signet ring. A large oval pad contains some type of firmly affixed clay. The clay can be smoothed over by working it with a finger for a moment, then pressed to an object so it can take its shape.

A golden ring topped with a large half-sphere of amber. Flanges of gold extend in every direction from the amber in a starburst pattern.

An oak ring with a raised, rectangular opening carved along the top edge. Small pieces of ivory have been fitted into the opening, resembling the bared teeth of a predator.

A tiny shield of steel is mounted atop this otherwise simple ring of silver.

A miniature axe blade rises from the crest of this mithril ring. The blade is quite sharp, and while it may cause the bearer minor cuts from time to time, it can also be used similarly to brass knuckles dealing 1 point of damage.

A bone ring whose inner and outer bands are completely covered in engravings which resemble a top-down map of a city. The map in not familiar to any living creature and may be of another world or so ancient that it has been forgotten entirely.

A brass ring with a miniature candlestick mounted on its crest. A very tiny candle could be mounted there, though it wouldn’t be very useful, and would likely be a burning hazard.

A ring made of layered metals, wrapped one atop the other. The bearer's finger touches the ring’s gold band, atop which is wrapped silver, then brass, and finally platinum.

A thick platinum ring with two dozen protruding stems rising from its crest. Atop each stem is a polished gemstone chip including ruby, emerald, diamond, amber, and sapphire with no two gem being repeated.

#d&d#dnd#d&d 3.5#d&d 4e#d&d 5e#d&d homebrew#d&d 5e homebrew#loot#custom loot#loot generator#random loot table#pathfinder#trinkets#roleplaying#rpg#dungeons and dragons#dungeon master#dm#d&d ideas#treasure#treasure table#d&d resources#tabletop homebrew#rings

270 notes

·

View notes

Photo

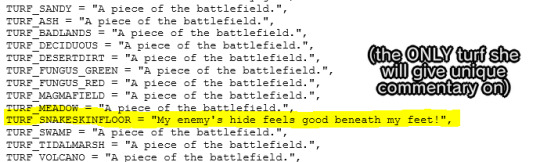

Column, Costumed Figure

Date: 8th–9th century

Geography: Mexico, Mesoamerica, Campeche

Culture: Maya

This limestone column, carved in medium relief, depicts an ornately dressed individual and a dwarf. The central figure is most likely a Maya ruler, and he wears an enormous tiered headdress with feathers splaying to the tops and sides of the column. He also wears a collar with three images of human heads, and a long beaded necklace. In his right hand, he carries a hooked blade, and his left arm is hidden behind a shield with a central knotted element. Most of his body is covered by a long apron made of square mosaic elements, and he wears high-backed sandals on his feet. On the right side of the monument stands a dwarf who wears a columnar headdress and large earflare assemblages, or ornaments worn in the earlobe (see 1994.35.591a, b for an example of an earflare set, and 1979.206.1047 for individuals wearing earflare assemblages).

Carved columns are not common in ancient Maya art, but they do appear in the Puuc region of the Yucatan Peninsula in the eighth and ninth centuries AD. Another column in the Worcester Art Museum in Massachusetts—also depicting a standing ruler with dwarves—is thought to be the pair to this column; together, the two columns probably flanked a doorway. The doorway was most likely topped by a carved lintel, which depicted two seated individuals on either side of a deity face from which water lilies emerge. The unfinished and irregular rear portion of the column suggests it may have been embedded in a wall rather than freestanding. In its original setting, this column would have been visible to people outside and entering the building, which was probably a long, low range building common in the Puuc region. The column would originally have been brightly colored, and the remains of red pigment are still visible on the ruler’s face.

The costume and accessories of the ruler refer to themes of warfare, sacrifice, and agricultural fertility. The ruler wears an enormous headdress that represents a monstrous zoomorphic head. Two central rosettes are stacked above the ruler’s head. From the upper rosette, a trapezoidal element emerges; this is the monster’s nose, and on either side of it are its eyes, with curlicue pupils. Two curved fangs are located between the upper and lower rosettes. Although there is no lower jaw on this headdress, similar headdresses on other monuments do include a lower jaw, and ancient viewers of this monument would have understood the ruler’s head as emerging from the mouth of the monster. The square plaques of the mosaic apron were probably meant to represent jade. Jade plaques also appear on the top part of the headdress between the upper and lower rosette.

This headdress is derived from a motif known as the War Serpent headdress. Originally from the great Central Mexican city of Teotihuacan, the War Serpent headdress was adopted by Maya leaders beginning around 400 A.D., when Teotihuacan influence spread through the central Maya area. Classic Maya rulers wore the War Serpent headdress as a sign of military strength and to associate themselves with powerful "outsider" forces. By the time this column was carved, probably in the ninth century A.D., the headdress was a common motif that may not have been explicitly associated with Teotihuacan.

That this headdress was still associated with warfare, however, is indicated by the objects the ruler carries in his hands. The obsidian blade in the ruler’s right hand is shown as a hooked implement. Similar objects are carried by rulers on other monuments from this part of the Maya world, including the column in the Worcester Art Museum (see 1978.412.195 for an elaborate figural obsidian blade). The blade carries multiple meanings. It may refer to the rain god, Chahk, who uses an axe to break the clouds and make rain. Ensuring the continuation and fertility of agricultural cycles was one of the central duties of Maya rulers; wielding an axe, then, refers to this important role. The obsidian weapon may also be a sacrificial blade. On similar columns from the Puuc region, including columns from Sayil Structure 4B and an unprovenanced column in the Ethnologisches Museum in Berlin, rulers carry sacrificial blades with globular objects at the tip that may represent human hearts. These blades emphasize military sacrifice as one of the important duties of Maya kings. In the ruler’s left hand—presumably, since we cannot see the hand itself—is a shield. The central design in the shield is made up of crossed bands that may relate to the woven mat symbol, associated with authority and the right to rule.

Other elements of this ruler’s costume point to an interest in lineage. The ruler’s collar features one frontal head, facing toward the viewer, with three dangling celts (see Celt 1994.35.356). An additional head, in profile, adorns each shoulder (the head on the left is less visible due to damage to the monument). Maya rulers often wore the names or visages of their ancestors in their costumes, physically linking themselves to their royal predecessors and emphasizing their own dynastic legitimacy. These heads would most likely have been made of jade and strung together with jade beads and plaques to create the thick collar we see on the monument today. Below the collar, a long beaded necklace ends in a central bar pendant. Water lilies emerge from either side of the central bar and from the bottom, echoing the water lilies on the lintel that once accompanied this column.

On the right side of the column, the dwarf is framed by feathers from the ruler’s headdress. Dwarves appear in a variety of contexts in Maya art, but they are represented most prominently as courtly attendants. On Maya ceramics, dwarves hold mirrors so that rulers can see themselves in their finery (see Mirror-Bearer 1979.206.1063 for a sculptural version of this motif), while jade plaques depict dwarves seated next to rulers. Dwarves are particularly common in monumental art from the Puuc area, where they appear frequently on columns and jambs in architectural settings. On this monument, the bent arm of the dwarf may represent a gesture associated with dance.

The dwarf, the costume of the ruler, and the obsidian blade suggest that this scene depicts a ritual dance performance. Other sculptures from the Puuc area, such as Xcalumkin Jamb 4, Xcocha Columns 2 and 3, and the columns from Sayil Structure 4B1, depict richly dressed, dancing individuals holding shields and obsidian blades. Each of the two columns from Sayil also depicts a dwarf standing next to the dancing ruler, and the column in the Worcester Art Museum features two dancing dwarves. Dance was an important ritual action in ancient Maya life, and was particularly important to Maya kings, who used the movement of their body to express royal authority, communicate with supernatural powers, and symbolize community and cultural ideals. The architectural setting of this column in a doorway, moreover, suggests that dancers may have moved in and out of this building, and that the building itself may have served as a setting for ritual dances related to agricultural fertility, warfare, and sacrifice.

While the composition of this monument is largely symmetrical, a closer look reveals subtle differences that indicate at least two different artists worked on this sculpture. For example, the rectangular flanges on either side of the ruler’s face display different sculptural approaches. On the left of the face, the fret motif is orderly and restrained, and the curved lines of the feathers emerging from the flange are incised with delicate lines. On the right side, the sturdy fret motif and the lack of incised lines on the feathers indicate a sculptor interested in conveying solidity and weight. The outer line of the eyes on the headdress, too, curves downward on the right, but not on the left. The column at the Worcester Art Museum also displays this asymmetry, suggesting that the irregularities in this column reflect regular artistic practice.

Finally, the damaged faces on this monument hint at the power of carved stone in the ancient Maya world. The eyes, nose and mouth of the ruler have been intentionally damaged, as has part of the face of the dwarf. For the Maya, carved stone monuments were not static representations of the people they depicted. Instead, such sculptures shared the identity and essence of their subjects. A column with an image of a ruler, in other words, would have been understood as an extension of that ruler and that ruler’s holiness, or ch’ulel. As such, sculptures were powerful agentive beings, and that power required careful maintenance and negotiation. Chipping off the faces on stone monuments would have offered one way of terminating that power. Ancient defacers paid particular attention to the nose, which was a conduit for holy breath; destroying the nose may have been considered an effective ritual closure (see also Maya Monument L.1970.78, where the profile of the ruler Yo’nal Ahk was also defaced in antiquity). Despite the damaged faces, this monument clearly conveys the power of the ruler as a warrior, sacrificer, and dancer, ensuring the continuation of life cycles through ritual action and the presentation of military strength.

Caitlin C. Earley, Jane and Morgan Whitney Fellow, 2016

Sources and Additional Reading

Houston, Stephen D., and David Stuart. "The Ancient Maya Self: Personhood and Portraiture in the Classic Period." RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics 33(1998):73–101.

Just, Bryan R. "Modifications of Ancient Maya Sculpture." RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics 48(2005):69–82.

Looper, Matthew G. To Be Like Gods: Dance in Ancient Maya Civilization. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2009.

Mayer, Karl Herbert. Classic Maya Relief Columns. Ramona, California: Acoma Books, 1981.

Masterworks of Primitive Art, fig. 5. New York: Furman Gallery, 1962.

Miller, Mary Ellen and Megan E. O’Neil. Maya Art and Architecture. London: Thames and Hudson, 2014.

Miller, Virginia E. "The Dwarf Motif in Classic Maya Art." In Fourth Palenque Round Table, 1980, edited by Merle Greene Robertson and Elizabeth P. Benson, pp. 141–153. San Francisco: Pre-Columbian Art Research Institute, 1985.

Pollock, H.E.D. The Puuc: An Architectural Survey of the Hill Country of Yucatan and Northern Campeche, Mexico. Memoirs of the Peabody Museum, Vol. 19. Cambridge, MA: Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, 1980.

Stone, Andrea. "Disconnection, Foreign Insignia, and Political Expansion: Teotihuacan and the Warrior Stelae of Piedras Negras." In Mesoamerica After the Decline of Teotihuacan, AD 700–900, edited by Richard A. Diehl and Janet C. Berlo, pp. 153–172. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks, 1989.

The Met

#archaeology#arqueologia#maya#mesoamerica#campeche#mexico#art#arte#history#historia#puuc#yucatan#teotihuacan#sayil

49 notes

·

View notes

Photo

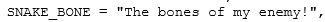

Column, Costumed Figure

8th–9th century. Campeche, Mexico. Maya

The Met

This limestone column, carved in medium relief, depicts an ornately dressed individual and a dwarf. The central figure is most likely a Maya ruler, and he wears an enormous tiered headdress with feathers splaying to the tops and sides of the column. He also wears a collar with three images of human heads, and a long beaded necklace. In his right hand, he carries a hooked blade, and his left arm is hidden behind a shield with a central knotted element. Most of his body is covered by a long apron made of square mosaic elements, and he wears high-backed sandals on his feet. On the right side of the monument stands a dwarf who wears a columnar headdress and large earflare assemblages, or ornaments worn in the earlobe (see 1994.35.591a, b for an example of an earflare set, and 1979.206.1047 for individuals wearing earflare assemblages).

Carved columns are not common in ancient Maya art, but they do appear in the Puuc region of the Yucatan Peninsula in the eighth and ninth centuries AD. Another column in the Worcester Art Museum in Massachusetts—also depicting a standing ruler with dwarves—is thought to be the pair to this column; together, the two columns probably flanked a doorway. The doorway was most likely topped by a carved lintel, which depicted two seated individuals on either side of a deity face from which water lilies emerge. The unfinished and irregular rear portion of the column suggests it may have been embedded in a wall rather than freestanding. In its original setting, this column would have been visible to people outside and entering the building, which was probably a long, low range building common in the Puuc region. The column would originally have been brightly colored, and the remains of red pigment are still visible on the ruler’s face.

The costume and accessories of the ruler refer to themes of warfare, sacrifice, and agricultural fertility. The ruler wears an enormous headdress that represents a monstrous zoomorphic head. Two central rosettes are stacked above the ruler’s head. From the upper rosette, a trapezoidal element emerges; this is the monster’s nose, and on either side of it are its eyes, with curlicue pupils. Two curved fangs are located between the upper and lower rosettes. Although there is no lower jaw on this headdress, similar headdresses on other monuments do include a lower jaw, and ancient viewers of this monument would have understood the ruler’s head as emerging from the mouth of the monster. The square plaques of the mosaic apron were probably meant to represent jade. Jade plaques also appear on the top part of the headdress between the upper and lower rosette.

This headdress is derived from a motif known as the War Serpent headdress. Originally from the great Central Mexican city of Teotihuacan, the War Serpent headdress was adopted by Maya leaders beginning around 400 A.D., when Teotihuacan influence spread through the central Maya area. Classic Maya rulers wore the War Serpent headdress as a sign of military strength and to associate themselves with powerful "outsider" forces. By the time this column was carved, probably in the ninth century A.D., the headdress was a common motif that may not have been explicitly associated with Teotihuacan.

That this headdress was still associated with warfare, however, is indicated by the objects the ruler carries in his hands. The obsidian blade in the ruler’s right hand is shown as a hooked implement. Similar objects are carried by rulers on other monuments from this part of the Maya world, including the column in the Worcester Art Museum (see 1978.412.195 for an elaborate figural obsidian blade). The blade carries multiple meanings. It may refer to the rain god, Chahk, who uses an axe to break the clouds and make rain. Ensuring the continuation and fertility of agricultural cycles was one of the central duties of Maya rulers; wielding an axe, then, refers to this important role. The obsidian weapon may also be a sacrificial blade. On similar columns from the Puuc region, including columns from Sayil Structure 4B and an unprovenanced column in the Ethnologisches Museum in Berlin, rulers carry sacrificial blades with globular objects at the tip that may represent human hearts. These blades emphasize military sacrifice as one of the important duties of Maya kings. In the ruler’s left hand—presumably, since we cannot see the hand itself—is a shield. The central design in the shield is made up of crossed bands that may relate to the woven mat symbol, associated with authority and the right to rule.

Other elements of this ruler’s costume point to an interest in lineage. The ruler’s collar features one frontal head, facing toward the viewer, with three dangling celts (see Celt 1994.35.356). An additional head, in profile, adorns each shoulder (the head on the left is less visible due to damage to the monument). Maya rulers often wore the names or visages of their ancestors in their costumes, physically linking themselves to their royal predecessors and emphasizing their own dynastic legitimacy. These heads would most likely have been made of jade and strung together with jade beads and plaques to create the thick collar we see on the monument today. Below the collar, a long beaded necklace ends in a central bar pendant. Water lilies emerge from either side of the central bar and from the bottom, echoing the water lilies on the lintel that once accompanied this column.

On the right side of the column, the dwarf is framed by feathers from the ruler’s headdress. Dwarves appear in a variety of contexts in Maya art, but they are represented most prominently as courtly attendants. On Maya ceramics, dwarves hold mirrors so that rulers can see themselves in their finery (see Mirror-Bearer 1979.206.1063 for a sculptural version of this motif), while jade plaques depict dwarves seated next to rulers. Dwarves are particularly common in monumental art from the Puuc area, where they appear frequently on columns and jambs in architectural settings. On this monument, the bent arm of the dwarf may represent a gesture associated with dance.

The dwarf, the costume of the ruler, and the obsidian blade suggest that this scene depicts a ritual dance performance. Other sculptures from the Puuc area, such as Xcalumkin Jamb 4, Xcocha Columns 2 and 3, and the columns from Sayil Structure 4B1, depict richly dressed, dancing individuals holding shields and obsidian blades. Each of the two columns from Sayil also depicts a dwarf standing next to the dancing ruler, and the column in the Worcester Art Museum features two dancing dwarves. Dance was an important ritual action in ancient Maya life, and was particularly important to Maya kings, who used the movement of their body to express royal authority, communicate with supernatural powers, and symbolize community and cultural ideals. The architectural setting of this column in a doorway, moreover, suggests that dancers may have moved in and out of this building, and that the building itself may have served as a setting for ritual dances related to agricultural fertility, warfare, and sacrifice.

While the composition of this monument is largely symmetrical, a closer look reveals subtle differences that indicate at least two different artists worked on this sculpture. For example, the rectangular flanges on either side of the ruler’s face display different sculptural approaches. On the left of the face, the fret motif is orderly and restrained, and the curved lines of the feathers emerging from the flange are incised with delicate lines. On the right side, the sturdy fret motif and the lack of incised lines on the feathers indicate a sculptor interested in conveying solidity and weight. The outer line of the eyes on the headdress, too, curves downward on the right, but not on the left. The column at the Worcester Art Museum also displays this asymmetry, suggesting that the irregularities in this column reflect regular artistic practice.

Finally, the damaged faces on this monument hint at the power of carved stone in the ancient Maya world. The eyes, nose and mouth of the ruler have been intentionally damaged, as has part of the face of the dwarf. For the Maya, carved stone monuments were not static representations of the people they depicted. Instead, such sculptures shared the identity and essence of their subjects. A column with an image of a ruler, in other words, would have been understood as an extension of that ruler and that ruler’s holiness, or ch’ulel. As such, sculptures were powerful agentive beings, and that power required careful maintenance and negotiation. Chipping off the faces on stone monuments would have offered one way of terminating that power. Ancient defacers paid particular attention to the nose, which was a conduit for holy breath; destroying the nose may have been considered an effective ritual closure (see also Maya Monument L.1970.78, where the profile of the ruler Yo’nal Ahk was also defaced in antiquity). Despite the damaged faces, this monument clearly conveys the power of the ruler as a warrior, sacrificer, and dancer, ensuring the continuation of life cycles through ritual action and the presentation of military strength.

Caitlin C. Earley, Jane and Morgan Whitney Fellow, 2016

Sources and Additional Reading

Houston, Stephen D., and David Stuart. "The Ancient Maya Self: Personhood and Portraiture in the Classic Period." RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics 33(1998):73–101.

Just, Bryan R. "Modifications of Ancient Maya Sculpture." RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics 48(2005):69–82.

Looper, Matthew G. To Be Like Gods: Dance in Ancient Maya Civilization. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2009.

Mayer, Karl Herbert. Classic Maya Relief Columns. Ramona, California: Acoma Books, 1981.

Masterworks of Primitive Art, fig. 5. New York: Furman Gallery, 1962.

Miller, Mary Ellen and Megan E. O’Neil. Maya Art and Architecture. London: Thames and Hudson, 2014.

Miller, Virginia E. "The Dwarf Motif in Classic Maya Art." In Fourth Palenque Round Table, 1980, edited by Merle Greene Robertson and Elizabeth P. Benson, pp. 141–153. San Francisco: Pre-Columbian Art Research Institute, 1985.

Pollock, H.E.D. The Puuc: An Architectural Survey of the Hill Country of Yucatan and Northern Campeche, Mexico. Memoirs of the Peabody Museum, Vol. 19. Cambridge, MA: Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, 1980.

Stone, Andrea. "Disconnection, Foreign Insignia, and Political Expansion: Teotihuacan and the Warrior Stelae of Piedras Negras." In Mesoamerica After the Decline of Teotihuacan, AD 700–900, edited by Richard A. Diehl and Janet C. Berlo, pp. 153–172. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks, 1989.

43 notes

·

View notes