#aladdin's mother

Note

So I remember you said in your Disney-Verse you were going to use the scrapped plot line of Aladdin and Mozenrath learning they were long-lost brothers and that got me wondering how Cassim and Mozenrath's mother met and ended up having relations that ended in the conceiving of Mozenrath.

@rememberingmermaids Yea! Sorry for the wait, I had some other projects I needed to finish first.

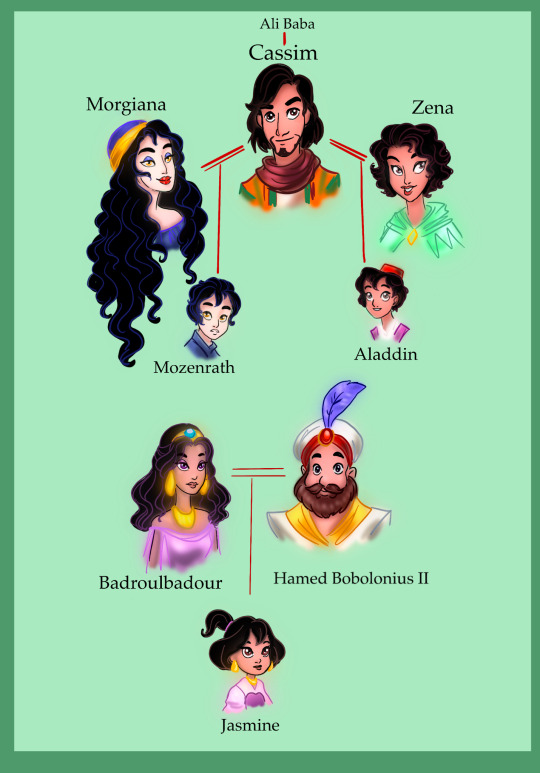

So in the og story of Ali Baba and the 40 Thieves, Ali Baba's brother is named Cassim, and he dies when the theives discover him stealing from their cave. And Ali Baba ends up later marrying his son to his servant girl Morgiana after she helps save the family from the thieves when they try and sneak into his home to get revenge for stealing from them.

And since we know that some version of this story does happen in Aladdin's reality as Genie mentions it, I thought it made a ton of sense to have our Cassim be the son of Ali Baba. He's named for his uncle, he grew up poor and despised, so him talking about being called a streetrat and wanting more still totally works. Then his family finally gets a taste of the good life. Wealth and the comfort and security it brings.

But then something goes wrong.

Somehow the wealth fails. Maybe bad investments, bad luck. Whatever faitytale tropes befall once wealthy families to bring them low. Ali Baba can't find the magic cave again, it's moved to a new location (being magic and all). Cassim watches all that security fall away and his family that was so well respected when they were rich goes right back to being shunned once they're poor again.

His wife even leaves him. Though tbf to her, it had been an arranged marriage set up by his father. A reward for Morgiana, so he thought. Now she was a member of the family and not a servant! Never mind if maybe she'd wanted something else from her life. Like actual freedom.

Not that Cassim was a bad husband per se, he just wasn’t what she chose, nor he her. And when she sees an opportunity to forge her own life for once, she takes it.

Neither of them realize she's carrying his child.

So Cassim, desperate to regain a taste of what he'd had, goes on a desperate search to find that magical cave his father had told him stories of so many times.

Along the way he makes many friends and foes, more the later, which causes him to take up several aliases. Its under the guise of a lamp seller named "Hamid" that he meets a young adventuress named Zena, and the two soon fall in love and marry (after he's told her who he really is of course).

And for a while he's content.

But once they have a baby on the way, the old need,want,obsession comes back. He's got to find the treasure cave for the baby, for his family. To prove that he's not delusional and hasn't wasted most of his life on this.

He leaves. Fails. Comes back. They're both gone. He leaves again. And this time he finally succeeds. It doesn't feel like the success he hoped it would. But with nothing else to live for but gaining more gold, he claws his way to the top of this new incarnation of the 40 Thieves, and tries to block out the memories of his old life.

Morgiana meanwhile, has always had a talent for magic, and she uses it and her wits to get by in the world. For herself and her son. It's a hard life, constantly on the move, but it's a free one. And her young son it turns out shares her magical talent. For several years they're happy together.

Until they catch the eye of the sorcerer Destane, ruler of the Land of the Black Sand. He coveted Morgiana's power, and her beauty. When she refused him both, he turned his wrath on her, and unfortunately, his power was greater. Her son he took as his slave, and something of an apprentice, though only to make him more useful. The boy hated his captor, but was cunning, biding his time until he had learned enough in secret to overthrow him and take his place as the lord sorcerer of the Black Sands. His hatred of his erstwhile master and desperation to be his own, led him to greater and greater schemes of power. At one point to trade his true name in order to possess a magical gauntlet that would triple his power, a boon he would need if he were to achieve his goal of conquering the Seven Deserts.

And from ever on, he was known as Mozenrath.

***

Meanwhile on Jasmine's side, young sultan Hamed Bobolonius II (who's name we know from a deleted line in an earlier song draft x) was smitten the instant he saw his intended bride, the beautiful Princess Badroulbadour of Sherabad.

(So smitten, in fact, that he ended up picking a flower for his new bride from an enchanted garden, an act that ended up getting him into some hot water later on.)

The princess was unsure of her new betrothed at first but was so won over by his kindness and enthusiasm. Their story might not have as many twists and turns as Aladdin's parents did, but it had a lot of love. They were very happy together, especially when their daughter was added to their family, and were grateful for each moment they had together up until the Sultana's untimely death, soon after the appointment of the Sultan's new Royal Vizir.

(Badroulbadour, it may be supposed, was a much better judge of character then her overly trustful husband, and therefore was better off "out of the picture" in the schemes of Jafar)

#asks#disney#disneyverse#disney parent backstory#disney parents#disney headcanons#aladdin#aladdin 3#aladdin zena#aladdin cassim#aladdin's mother#mozenrath#aladdin the animated series#aladdin the sultan#princess jasmine#jasmine aladdin#Jasmine's mother#Badroulbadour#ali baba and the forty thieves#arabian nights#1001 nights

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ok I get that you should not make fun of people interpretation of characters and that character playlist are not that deep but whoever put a god damn Taylor swift song on a spiderpunk playlist should never be allowed near spotify ever again

#No tiktok user Spiderpunk would not listen to mother mother#or lemon demon#or weezers#or katy perry#or tally hall#or tv girl#or Mariah Carey#or hamilton#or heathers#or the will smith song from the live action Aladdin#or roar#or the lovejoys#or the arctic monkeys#or liana flores#spiderman atsv#spiderman across the spiderverse#spider punk#across the spiderverse#hobie brown#spiderverse#spiderman

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Currently pirating Disney movies

#disney#Ursula#jafar#dr. facilier#Gaston#hades#maleficent#cruella de vil#mother gothel#the evil queen#the little mermaid#aladdin#the princess and the frog#beauty and the beast#Hercules#sleeping beauty#101 dalmatians#tangled#snow white and the seven dwarfs

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

#polls#tumblr polls#hellfire#the hunchback of notre dame#be prepared#the lion king#friends on the other side#the princess and the frog#poor unfortunate souls#the little mermaid#gaston#beauty and the beast#aladdin#emperors new groove#the great mouse detective#mother knows best#tangled

911 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you have any headcanons about the other parents of the VKs?

YES

Evil Queen used Evie as a servant for most of her life, only stopping when she realized how dirty Evie was getting

Cruella tried to train Carlos with a dog whistle and a spray bottle - but with the water on the Isle being so dirty and likely toxic it caused Carlos to get sick. While Cruella didn't care about that, she didn't want to get sick, so she stopped with the spray bottle, and then with the whistle after finally realizing that he couldn't hear it. (The Isle made her a lot more unstable)

Jafar has tried to arrange marriages for Jay with those on the Isle who might be able to have wealth in Auradon, such as the Evil Step-Granddaughters and the Queen of Hearts daughter, but it never worked out. He's tried multiple times to pair Jay off with Mal.

Gaston takes his boys out "hunting"... make of that what you will.

Gaston also managed to bribe one of the Auradon guards to bring over some chickens and a rooster so each of his boys, and himself, can have five dozen eggs a day.

Hans is actually a pretty decent father. If you ignore the fact that he's taught his kid(s) all his manipulation tactics. That aside, he's also taught them how to read, write, mathmatics, history, etiquet, etc.

Smee loves his kids, but he isn't exactly always there for them. Because of this, Sammy took care of his brothers growing up more than his father did.

Anastasia is a good mom. Along with taking care of her own kids, she takes care of a lot of the orphans on the island. And Dizzy has practically become hers.

On a similar note, Drizella is not a good mother and has A LOT of children, all girls. Some of her girls are as high-strung and rotten as she is, but the younger ones (like Dizzy) have become little "Cinderella's".

Surprisingly, Lady Tremaine tried to stop it, but never succeeded.

Ursula taught Uma all the Greek myths and legends, and would repeatedly tell her that one day they'd get off the island.

While he's an amazing father to Celia, Dr. Facilier wasn't the greatest dad to Freddie and does regret it (even if he won't admit it)

Like Hans, Captain Hook made sure his kids knew how to read and write. He also taught Harriet and Harry how to read maps, create maps, as many constellations as he could remember (many drawn out on paper), swordfighting, and pretty much everything that goes along with being a pirate. (He would have taught CJ, but after his wife's death he pulled away from her - CJ looks the most like the siblings mother)

Mother Gothel treats Ginny like a maid, but isn't the worst parent. The worst she's done is drag on Ginny's appearance to make herself look better (which is bad, but on an island of villains, better than a lot of kids get). Somewhere in her, she might love Ginny, but at the end of the day Mother Gothel is an incredibly selfish woman.

(A similar headcanon that can also be true is that Mother Gothel is actually Ginny's grandmother, and Ginny is Cassandra's daughter only Cassandra willingly let her mother raise Ginny in order to protect her as Cass isn't the most popular on the Isle)

The Huntsman has taught his kids everything he knows and they do animal control - they can't really harm the original hyenas who were thrown on the Isle, but they can take care of the never ones.

Morgana kept having children in hopes that eventually one would transform while under the barrier, but it never happened. Over the course of twenty years, she managed to have 15 children and had to open up her own school.

Edgar lives quietly in his very run down apartment in the square where he and his son run an animal grooming business. With how many "evil animal sidekicks" there are, it goes surprisingly well. He has to leave the room whenever a cat comes in, though, so Eddie does a lot of the word.

Yzma tends to conduct very dangerous experiments in her attempt to do magic.

The Stabbington Brothers have raised their children together, so the Stabbington Cousins are really more like siblings. With that said, the brothers have been determined to raise children who will become better thieves than Flynn Rider, and better fighters than themselves. The fighting has gone good, but the they're never satisfied with the Cousins thievery thanks to Jay always managing to beat them.

#disney descendants#descendants#descendants headcanons#disney villains#mother gothel#lady tremaine#disney gaston#jafar aladdin#the evil queen#cruella de vil#prince hans#captain hook#the isle of the lost

235 notes

·

View notes

Text

More than "Sheer Coincidence": The Antisemitism of Disney's Animated Villains

This is a paper I wrote for a Jewish studies class. It was inspired by a tumblr post, so I thought it was fitting to share here. Most will be under a "read more" link, as it is about 25 pages including the bibliography. Please feel free to ask questions, and enjoy.

_______

On June 19, 2022, Tumblr user fantastic-nonsense published a post about Disney’s 2010 animated film Tangled, and the film’s villain, Mother Gothel, which starts, “*sigh* the ‘Mother Gothel is an anti-semitic caricature’ discourse is going around again.” They argue that, because Mother Gothel’s appearance was based on two non-Jewish women, Gothel’s voice actress Donna Murphy and singer Cher, any claim that Mother Gothel’s large nose or dark, curly hair resemble antisemitic caricatures was simply projection. The goal of Gothel’s design was to make her as visually distinct as possible from Rapunzel, not to make her “look Jewish.” They continue with a question:

“[I]f Gothel was blonde with a ‘normal’ nose…but literally nothing else about her changed, would you be saying that she’s an anti-semitic stereotype?...All I’m saying is that Gothel (and thus Tangled) is unreasonably linked to those tropes…There is a very distinct difference between being actively anti-semitic and Tangled, which has anti-semitism being projected on it because its villain bears passing similarity to anti-semitic caricatures out of sheer coincidence.”

The user has since deleted the original post, but a reblog remains further arguing their point. In an attempt to defend the film from criticisms of antisemitism, fantastic-nonsense stumbles upon a fundamental conundrum of analyzing villainous characters such as Mother Gothel: Is it possible to create a villainous character that avoids all potential antisemitic pitfalls? And, despite fantastic-nonsense insisting it’s a “sheer coincidence,” why do so many Disney villains have stereotypically Jewish traits?

Unmasking Antisemitism: The Origins of Disney’s Jewish Villains

Jewish people have long been viewed as villainous in various gentile European cultures, a view brought to the United States through colonization. Accusations of blood libel go back to the 12th century and have been noted from eastern Europe to England. Famous authors and playwrights such as Charles Dickens and William Shakespeare indicate a centuries-long trend of villainous characters defined by their Jewishness, and infamous business magnate Henry Ford published accusations of predatory banking practices and fervent Christian hatred in his pamphlet series The International Jew in the early 1920s, before Disney was a studio. With centuries of association between Jews and villainy as a backdrop, there is little surprise that Disney turned to antisemitic tropes in the construction of one of its earliest villains.

The 1933 short Three Little Pigs is remembered as one of the most successful shorts from Disney’s Silly Symphonies series. Not only was the film the source of the song “Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?” which became an anthem to “Depression-weary audiences,” but the film was a milestone in character development, versus the characters existing only to serve gags. Walt Disney was so proud of the finished film, he said, “At last we have achieved true personality in a whole picture.” Part of developing the characters’ personalities was creating a menacing villain, an archetype Disney would come to be known for, and the Big Bad Wolf is one of its earliest successes on this front. The film follows the typical narrative of the fairy tale, with a trio of pigs each building their own house, one of straw, one of sticks, and one of brick. We see the Wolf approach them as the first two are frolicking after constructing their flimsy houses, drool pouring from his mouth filled with sharp teeth. While the Wolf is able to simply blow away the straw house, the house of sticks proves to be a bit stronger, and he resorts to trickery, pretending to give up and leave the pigs alone before returning dressed as a sheep and asking for shelter. The pigs sees through this disguise, refuse him entry, and his anger gives him the strength to blow down the house of sticks. When the pigs flee to the house of bricks, the Wolf returns with a new disguise: a Jewish peddler.

Wearing a large brown overcoat, green-tinted glasses and a skullcap, and adorned with a fake beard and long nose, the Wolf knocks on the door of the brick house with a rack of brushes around his neck, proclaiming in a Yiddish accent, “I’m the Fuller Brush man, I’m giving a free sample!” The pig from the brick house, quickly seeing through his tricks, proceeds to hit him with said free sample before pulling a welcome mat from beneath the Wolf’s feet, causing him to land on his face and his false nose to bend 90° towards the sky. The Wolf rips off the disguise in anger, and the short continues.

The association of Jews and the peddling profession arose during the 19th century, as peddling helped facilitate the mass migration of Jews across the globe during that time. Peddling was more accessible to poor immigrant Jews than owning a store, and the freedom of self-employment allowed them to maintain their own schedule and keep Shabbat, unlike factory jobs. As most peddlers did not maintain the job for more than a decade, nor pass it down to their sons, peddlers represented a lack of assimilation, perpetually tying the occupation to otherness, which facilitates the villainization of peddlers through their Jewishness.

The stock character of the “Jew peddler” quickly entered popular culture, giving all manner of creatives, from commentators to novelists, a new punching bag in their library of cultural symbols. As Hasia Diner describes the figure in her book Roads Taken: The Great Jewish Migrations to the New World and the Peddlers Who Forged the Way, “Sinister and shadowy, exotic or absurd, he made a good subject for mockery, with his odd accent, his clothing, his lack of a fixed abode, and his distinctive bodily features: in this milieu, a prominent hooked nose was a sure sign of Jewishness, a long beard a likely trait as well.”

Director Burt Gillett created a costume for the Disney short’s villain which ticked off every box in the “Jew peddler” playbook. A symbol of “trickery, otherness, and greed,” and pervasively believed to be dishonest, the peddler costume serves not only as a disguise for the Wolf, but to highlight those traits in his villainous hunt of the pigs. Audiences would have had a pre-existing cultural understanding of the Jewish peddler as a costume. Throughout the 19th and into the early parts of the 20th century in the United States, local newspapers reporting on masquerade parties described “Jew peddler” costumes among princesses and pirates. With his two costumes being a play on the phrase “a wolf in sheep’s clothing” and the known manipulative figure of the Jewish peddler, the characterization of the Wolf is clear: He is so manipulative, even his choice in costumes shows off his deviousness.

There is a more intelligent side to the gag of the Jewish peddler costume; not only would the Wolf seem less threatening dressed as a Jewish peddler, but the pigs would assume he kept kosher and didn’t eat pork, easing their worries. Still, the use of antisemitic stereotypes to emphasize the Wolf’s dangerous and manipulative nature has been recognized as offensive, including by the company itself. A 1948 re-release of the short edited the animation to remove the antisemitic costume. The Wolf still dresses as a peddler, but without any Jewish signifiers, maintaining the overcoat but swapping the skullcap and green-tinted glasses for a bowler hat and clear ones, and forgoing the nose and beard altogether. Initially, the original audio was maintained, as the new animation of the wolf still matches the original dialogue, but a new version of the Wolf’s audio was recorded and replaced the Yiddish accent at a later date. Instead of hawking his wares in a Yiddish accent, the Wolf puts on a low, unintelligent-sounding voice and tells the pigs, “I’m working my way through college!” This is the version of the short that is available on Disney+, where no mention is made of the short’s history or the edits that were made to it. Although the Wolf does not have the same notoriety as many of Disney’s villains from feature-length films, he didn’t fall into complete obscurity, making a cameo in Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988) alongside the pigs, and appearing in the 2002 direct-to-video film Mickey’s House of Villains. 90 years after his first appearance, the Wolf’s legacy resonates in the designs and characterization, which Walt so highly praised, of the villains who came after him.

Hooked-Nosed Hags and Mincing Manipulators: Jewish-coding in 20th Century Disney Films

Disney took its first leap into feature-length animation in 1937 with Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Released only four years after Three Little Pigs, the film displayed a marked improvement in many areas of animation, particularly character design. While previous Disney shorts had largely starred animals, Snow White featured an entirely human or human-like cast. Unable to differentiate between hero and villain by species, designers needed other visual signifiers to indicate a character’s villainy or heroism to the audience. As former Disney character animator Andreas Deja wrote on his blog, where he frequently catalogs stories from Disney’s older films, “[Walt] Disney insisted on strong contrast between good versus evil, and that needed to be clear in the characters' design as well as their acting.”

In 1749, German philosopher and playwright Gotthold Ephraim Lessing wrote in his play Die Juden (The Jews), “And is it not true, their countenance has something that prejudices one against them? It seems to me as if one could read in their eyes their maliciousness, unscrupulousness, selfishness of character, their deceit and perjury.” For centuries, antisemites have posited that Jews not only are evil, but look evil based on their natural physical appearances. This idea quickly made its way into Disney’s understanding of character design. Although Three Little Pigs’ Wolf is the only villain who takes on an explicitly Jewish appearance, Disney has designed its villains with stereotypically Jewish traits as a visual indicator since its first feature film. This notion of visual signifiers of internal traits is derived from race science, a concept the American government had latched onto with the Dillingham Commission, a Congressional committee analyzing immigration in the United States at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century. In the Commission’s Statistical Review of Immigration, published in 1911, the “Hebrew” people were the third-lowest ranked group in the “Caucasian race.” As Jews were considered one of the least desirable groups of white people, common traits amongst them were quickly associated with villains, regardless of their background.

Snow White’s Queen Grimhilde does not have many stereotypically Jewish traits upon first glance. This is essential to the story, as the Queen was previously the “fairest one of all” until her title was taken by Snow White, whose beauty outshone hers even while dressed in rags. Because she is also beautiful, she could not be designed with ugly, villainous, “Jewish” traits. However, when she finds out the Huntsman failed to kill Snow White, she adopts a disguise in order to poison her without being recognized, much like the Wolf in The Three Little Pigs. Her disguise transforms her from a beautiful, regal woman into a decrepit witch, with a massive, hooked nose and deep eye bags, both common traits in antisemitic caricatures, marking her new form as Jewish. Her transformation marks her change into a more active villain role, pursuing Snow White herself instead of sending a henchman to find her. By the end of the film, the Queen’s internal ugliness, through her vanity and envy of Snow White, has physically manifested, showing that she was never really as beautiful as the kind-hearted and button-nosed Snow White.

The contrast between the Aryan features of Disney’s leading ladies and the ugly and Jewish-coded traits of their female villains continued for decades. Cinderella’s stepmother, Lady Tremaine, and her daughters are both drawn with large noses compared to Cinderella, who has a button nose similar to Snow White. Lady Tremaine is given a hooked nose and heavy-lidded eyes, just as Queen Grimhilde had in her disguise. Her less exaggerated appearance befits her more realistic villainy, portraying personal greed and child abuse rather than a magically enhanced poisoning plot. The stepsisters, on the other hand, are given bulbous noses, similarly to Snow White’s seven dwarves, largely indicating ugliness rather than Jewishness. In both cases, their designs are “more reminiscent of 101 Dalmatians male villains Horace and Jasper, rather than typical Disney female features.” All three are given features reminiscent of Disney’s male character designs, compared to Cinderella’s “proper” femininity, which, at this point in Disney’s history, was always white.

Maleficent and Aurora’s designs in Sleeping Beauty function similarly. Maleficent’s pointed nose, prominent horns, which Jews are often accused of having, and green skin make her appear inhuman compared to Aurora’s upturned nose and blonde hair. Maleficent’s appearance is also juxtaposed against the film’s good fairies, Flora, Fauna, and Merryweather, who look entirely human aside from their wings. Sleeping Beauty also furthers the concept of appearance reflecting personality, giving the cruel Maleficent an unnatural skin tone, and displaying her most powerful form, a dragon, at the climax of the film. It is important to note that both Maleficent and Queen Grimhilde use magic and potions in their villainy, while their respective princesses do not use magic on their own. Judaism and witchcraft have long been associated in European Christian concepts of witches, and these films both bring that trope into a new world of storytelling.

While Disney’s early female villains were largely coded as Jewish by their designs and the juxtaposition between them and Disney’s respective female lead’s designs meeting Euro-centric standards of beauty, male villains’ coding comes at the nexus of homosexual and Jewish male stereotypes, alongside their designs. In her description of the coverage of Leopold and Loeb’s 1924 murder trial, Sarah Imhoff wrote that “the press coverage did not often explicitly cite their Jewishness because it did not need to. Journalists and commentators were able to convey Jewishness without stating it directly. Certain characteristics—intellectual, physically weak, not fit for manual labor, perverted, and prone to illness and psychiatric imbalance—painted a gendered portrait of a Jewish man even without reference to race or religion.” Many of Disney’s male villains fit such descriptors, indicating their Jewishness to the audience without the religion ever being mentioned. Additionally, these descriptors–particularly “perverted,” which at the time was a euphemism for both religious and sexual deviance-- are often applied to gay men, while homosexuality was treated as its own psychological issue. Both queer and Jewish men are seen as feminine, not meeting the white Christian ideal of a strong, straight, and stable man. With such overlap, queercoding of male characters often coincides, intentionally or not, with Jewish-coding.

The effeminate, mentally unstable villain can be found as early as the 1950s with Peter Pan’s Captain Hook, a willowy man in a plumed hat prone to comedically anxious outbursts, with black, wavy hair and a large nose. Captain Hook is voiced with a British accent, as many of Disney’s male villains do (including Jafar, Scar, and Governor Ratcliffe, whose fitting British accent stands out against John Smith’s strangely American one), which is not typical of Jewish characters in American media. However, “unlike the good characters of the film, who are endowed with physical features more generally identified with Northern European characters, the Captain Hook character would appear to be more Southern or Eastern European…he is the villain, and the writers and artists chose to give him physical characteristics that somehow reflect his villainy.” The author does not mention Jews in his analysis, but the majority of American Jews are descended from Eastern European Jews, and the comparison is bolstered by the non-visible Jewish stereotypes Hook fits as well. Again, Hook’s features are contrasted against Peter Pan and Wendy’s straight, brown hair and upturned noses, matching his implicitly Jewish characteristics with an implicitly Jewish appearance.

The Disney Renaissance, a period from 1989-1999 which saw massive success for Disney and a notable Broadway influence on the films, also saw a barrage of male villains with notable Jewish-coded traits. While Aladdin’s Princess Jasmine has a slightly larger nose compared to her white princess predecessors, Jafar still has much more prominent and hooked nose and heavy-lidded eyes, traits even more prominent in early iterations of his design. Jafar fits many of the descriptors applied to Leopold and Loeb in lieu of calling them Jewish; he is a manipulative magician with a wiry frame, contrasted by Aladdin’s larger build and ability to run and swing around Agrabah to avoid guards, and becomes mad with power after wishing to become a genie himself. Appearance-wise, in addition to the Jewish-coded traits mentioned above, Jafar’s dress-like robe and elaborate headpiece give him a feminine appearance next to Aladdin’s pants and vest, and bare muscular chest, affirming his masculinity. Imhoff notes that, because of Jews’ intelligence and lack of physical prowess, the prevailing stereotype was that “Jews tended not to commit courageous crimes, but rather chose crimes where they did not have to confront their victims directly.” She extrapolates, “Jewish men’s crimes were crimes of intellect, not passion; manipulation, not aggression; outsmarting, not overpowering.” Jafar displays these methods of criminality multiple times, tricking Aladdin into fetching the genie’s lamp from the Cave of Wonders, lying to Jasmine about Aladdin being sentenced to death, and hypnotizing the Sultan with his staff to steal an heirloom jewel. Although Aladdin uses his wits to defeat Jafar by trapping him in the magic lamp, his physical strength both make him more attractive and capable in Jasmine’s eyes than Jafar, who pursues her for political gain.

The Lion King’s Scar is a more prominent example of the juxtaposition between the strong but simple hero and the weak but wily villain. After feminizing himself, proclaiming “I shall practice my curtsy,” when his brother King Mufasa tells him that Simba, Mufasa’s son, will one day be Scar’s king, Scar says, “Well, as far as brains go, I got the lion’s share. But when it comes to brute strength, I’m afraid I’m at the shallow end of the gene pool.” While the heroic Mufasa, and later Simba, are muscular and broad, Scar is drawn almost emaciated, his hips swinging with each step in an effeminate manner. Like Jafar, Scar rarely involves himself directly in his crimes, sending his hyena henchmen to do his dirty work while he devises a plan. While animated lions lack the physical traits associated with Jews, Scar’s strangely dark mane contrasts with Mufasa and Simba’s reddish fur, and the dark circles of fur around his eyes resemble both heavy eyelids and eyeshadow, serving as both a feminizing and Jewish trait. When Scar and Simba fight at the climax of the film, Scar resorts to gaslighting, trying to convince Simba that he is responsible for his father’s death, and tricks, throwing burning ashes into Simba’s face, rather than beating him with brute strength.

Pocahontas’ Governor Ratcliffe fits oddly into the field of simultaneously feminized and Jewish-coded villains. His purple outfit, braided hair, and posh mannerisms make him by far one of Disney’s most effeminate villains, and he is one of the most explicitly money-hungry villains in Disney’s film library, singing lyrics such as “It's mine, mine, mine/For the taking/It's mine, boys/Mine me that gold!” blatantly assigning Ratcliffe the stereotype of the greedy Jew. Yet the historical setting of the film, 17th century Virginia, makes it highly unlikely that Ratcliffe could possibly be Jewish. Still, his overwhelming greed and feminine mannerisms insert Jewish stereotypes into even the most unlikely settings, highlighting the pervasiveness of the stereotypes beyond direct acknowledgements of Judaism.

Although Hercules’ Hades is less feminized than his 90s predecessors, his coding is bolstered by frequent use of Yiddish words in his dialogue, describing Hercules as “the one schlemiel who can louse” up his plan, calling him “The yutz with the horse!” when directing the titans to attack him, and convincing Hercules to fall for his scheme by telling him, “We dance, we kiss, we schmooze, we carry on, we go home happy.” Portrayed as a fast-talking swindler, calling back to the fear of peddlers Disney utilized in Three Little Pigs, Hades follows the trend of having a hooked nose and deep-set eyes, as well as being significantly weaker than Hercules, who is characterized throughout the film by his immense strength and lack of forethought. While Hades nearly succeeds in getting Hercules to kill himself by diving into the River Styx to save Megara, once Hercules achieves godhood and becomes immortal, all it takes is a single punch to knock Hades himself into the river and defeat him.

Both Hades and Jafar also play upon fears of not just homosexuality but sexually deviant heterosexuality in their respective films. While Jewish men were characterized as feminine due to circumcision in the late 19th century, “Jews were not thought to endanger society by their supposed homosexuality but rather by their evil heterosexual drives. […] But while family life was intact among the Jews themselves, it was, so racists asserted, directed against the family life of others.’” While neither Jafar nor Hades express genuine attraction toward their female leads, each interferes with their predestined heterosexual relationship with the male lead. When Jafar fails to retrieve the lamp from Aladdin before he uses it, foiling his plan to become Sultan, his parrot henchman Iago suggests that Jafar marry Jasmine as a means of becoming Sultan instead. Jafar proceeds to brainwash the Sultan into pronouncing him Jasmine’s fiance while she builds a relationship with Aladdin, and nearly succeeds in forcing her to marry him, before Aladdin interrupts his plan. Hades gained leverage over Megara after she made a deal with him for a man who left her, and has her woo Hercules only to sacrifice her, using Hercules’ emotions to manipulate him into nearly killing himself trying to save Megara. In both cases, genuine heterosexuality triumphs over “evil heterosexual drives.” Even with Aladdin’s Arabian-inspired setting and multiple mentions of Allah by the Sultan, conceptions of pure heterosexual love shaped by Christian values save the heroines from deviant, and implicitly Jewish, heterosexuality.

Across decades, genders, and settings, Disney has not only continued to rely on antisemitic stereotypes to communicate villainy through character design, but has developed its villains to incorporate increasingly specific stereotypes that have been applied to Jews for decades, if not centuries.

(Not Her) Mother Knows Best: Mother Gothel and the Blood Libel of Tangled

The 2000s was a time of experimentation for Disney Animation. As the success of the Renaissance began to fade, Disney turned to genres and technologies it hadn’t worked with before. The early 2000s saw an onslaught of films with unprecedented science fiction elements, such as Atlantis: The Lost Empire, Treasure Planet, Lilo and Stitch and Meet the Robinsons. Beginning with Dinosaur in 2000, Disney slowly made its way into the field of CGI animation, developing its technology at a rapid pace across films like Chicken Little, Bolt, and the aforementioned Meet the Robinsons. After this decade of experimentation, Disney released a film which combined the musical and princess elements of the Renaissance with the CGI it had been developing, releasing its first CGI princess film: Tangled. A reimagining of the fairytale of Rapunzel, the film has been a topic of discussion since its release for both its villain, Mother Gothel, who embodies a wide variety of traits, both in her design and characterization, that have been negatively associated with Jews; and its story, which bears striking similarity to a long-standing antisemitic canard: blood libel.

Beginning with accusations of using blood in religious rituals in the 12th century, in the 13th century, an additional accusation further vilify Jews: “Jews killed Christian children to obtain their blood, turning ‘ritual murder’ into ‘blood libel’ or ‘ritual cannibalism.’” Jews were not only accused of killing Christian children, but using their bodies for personal gain. Although Tangled forgoes any child killing, its prologue tells a chillingly familiar tale of the kidnapping and exploitation of a beautiful, blonde infant by a dark and curly-haired, crooked-nosed woman, adapting the blood libel narrative for a new audience, just as blood libel narratives have adapted to fit “changing cultural and political climates.”

In developing a story fit for a feature-length movie, Tangled adds magical elements to its narrative absent from the original fairy tale. In the film, a drop of sunlight fell to earth in the form of a flower with incredible healing capabilities. This flower is discovered by Mother Gothel, whom the audience meets as an old woman, who discovers a song which, when sung to the flower, makes her young. Her young appearance incorporates many of the antisemitic archetypes present in previous villains including long, black, curly hair, dark, hooded eyes, and a pointed nose with a bump. Gothel hides the flower to hoard its powers for herself, immediately establishing her as greedy, another common antisemitic trope. When the pregnant queen falls ill, the search party is sent for the mythical flower, hoping it will heal her. It is found, and after drinking a medicine made from it, the queen recovers and gives birth to a healthy girl, Rapunzel, with hair that is inexplicably bright blonde, as both the queen and king have brown hair. Aging and growing desperate, Gothel sneaks into the castle and cuts a lock of Rapunzel’s hair, only to discover that the hair, which has gained the flower’s magic, loses that magic when cut. She decides to kidnap Rapunzel, hiding her away and raising her as her own to continue utilizing the hair’s magic properties.

Many Disney films have utilized the contrast between villains’ and heroes’ character designs to indicate to the audience which role they play, with villains getting Jewish-coded features and heroes largely getting Western European ones. In nearly every way, Rapunzel and Gothel’s designs are completely opposites. Gothel’s frizzy dark hair could never be related to Rapunzel’s blonde, straight, silky mane. Gothel’s eyes are dark and hooded where Rapunzel’s are green and wide. Gothel’s nose is bumpy and hooked where Rapunzel’s is small and turns up. Gothel is curvaceous where Rapunzel is petite. In every way that Rapunzel fits the Aryan ideal, Gothel sits firmly in the category of other, even if both are white. Gothel’s foreign appearance was very intentional by the film’s director. In an interview, co-director Byron Howard said, “So, Gothel is very tall and curvy, she’s very voluptuous, she’s got this very exotic look to her. Even down to that curly hair, we’re trying to say visually that this is not this girl’s mother.” This goal in character design was repeated by him and co-director Nathan Greno in various interviews.

More than simply creating visual difference between Rapunzel and Mother Gothel, Gothel’s “voluptuous,” “exotic look” plays into the classic trope of the “Beautiful Jewess,” an orientalized beauty who tricks others with her alluring appearance, “‘her beauty conceal[ing] her powers of destruction.’” Gothel gaslights Rapunzel to keep her in her tower, convincing her that her naivete makes the outside world too dangerous for her to live in, and the contrast between Gothel’s curvy and sexualized body and Rapunzel’s petite frame only serves to bolster her claims. It is notable that early iterations of Gothel’s design show her without many of the visually “Jewish” traits she has in her final designs, with straighter hair tied back in a low bun, rather than the large curly hair seen in the film. Several designs have long, but not hooked, noses, and higher collars, avoiding the “Jewish seductress” aspect of her design. Yet these designs were rejected in favor of one influenced by two famous women: Donna Murphy, who voiced Mother Gothel, and Cher. Cher in particular was looked to for being “very exotic and Gothic looking,” playing into the orientalization of the Beautiful Jewess, where “the physical beauty and sensuality of the Jewish woman, her dark hair…were almost always described using orientalizing tropes and characteristics.” Although neither Cher nor Murphy is Jewish, both have the dark, curly hair and large noses associated with Jews, and the choice to base Gothel’s appearance off of them, particularly Cher’s “exotic” beauty, plays directly into pre-existing antisemitic tropes, whether intentionally or not.

Like Queen Grimhilde and Jafar before her, Gothel utilizes a disguise as part of her villainy. However, Gothel’s disguise, her false youth, is constant throughout the film, rather than temporary for one evil act. The Beautiful Jewesses’ “imaginary proximity to seduction, sexuality, theater, and dance, as well as to masquerade and costumes, certainly had just as much to do with their femininity—situated outside of bourgeois gender roles—as with their Jewishness.” Both Gothel’s Jewish features and her sexualized femininity play a role in the manipulative nature of her youthful disguise.

Not only do the narrative similarities to blood libel and the design of Mother Gothel play into antisemitic tropes, but more so than previous evil mother figures in Disney films, Gothel fits the “stereotype of the overbearing, over-involved, suffocating Jewish mother.” While Queen Grimhilde and Lady Tremaine force Snow White and Cinderella, respectively, into servanthood, Gothel pretends to care for Rapunzel, as exemplified in the song “Mother Knows Best.” In addition to warning Rapunzel of the dangers of the world outside her tower, she guilts her for wanting to leave her, singing “Me, I'm just your mother, what do I know?/I only bathed and changed and nursed you/Go ahead and leave me, I deserve it/Let me die alone here, be my guest.” Her overbearing and manipulative parenting strategies were a key part of her character, and of Rapunzel’s, according to Howard and Greno. In an interview with Den of Geek, Greno said, “If it’s a story about a girl who’s stuck in a tower, and we wanted Rapunzel to be a smart character, she’s being manipulated. So, if Mother Gothel was a mean villainess…you’d be like, Why is Rapunzel staying in the tower? You needed to buy that this girl would be there for 18 years. Mother Gothel can’t be mean. She has to be very passive-aggressive,” and Howard added, “Gothel has to be more subtle…than a one-note, domineering mother.” By playing on the loving but overbearing Jewish mother trope, Tangled establishes Gothel as a convincingly threatening and manipulative villain. The movie’s narrative tropes, character designs, and character personalities that play upon antisemitic tropes, make it difficult to deny the antisemitism present in Tangled.

The Twist Villain; Or, How Every Villain is a Little Bit Jewish

In the 13 years since Tangled’s release, many of the antisemitic tropes that had become staples of Disney’s villainous characters have been absent from its films. This coincides with a trend often referred to as the “twist villain,” where the film presents a fake villain to the audience, only to reveal that a “good” character was secretly the villain the whole time. Villains like King Candy from Wreck-It Ralph, Hans from Frozen, Robert Callahan from Big Hero 6, and Mayor Bellwether from Zootopia all fall under this trope. Because these characters are not meant to be read by the audience as evil based on their design, they lack the Jewish-coded traits like dark, curly hair, hooked noses, and deep-set eyes that have been used to mark villains as evil in the past. Other films, in lieu of a proper villain, opt for a hero’s internal conflict or a non-malicious antagonistic force to drive the story, such as Moana, Frozen II, and Encanto. These new story structures seem to eliminate the antisemitism present in other Disney films. Yet the trend of villains hiding in plain sight, lulling even the audience into a false sense of security before revealing their true colors, also plays into centuries-old antisemitic tropes.

In 19th century German criminal justice literature, “the ‘Jewish crook’ (jüdischer Gauner), a code term for a type of criminal that could apply to non-Jews as well,” was defined by “dangerous criminality masked by an assumed identity—a falsely benign exterior.” Because Disney has created an association between stereotypically Jewish traits and villainy for decades, priming audiences to read such traits as evil, by creating villains who hide their true character from both audiences and other characters, both through their actions and their non-Jewish-coded appearances, the films which use a “twist villain” both reaffirm the visual villainy of such traits and play upon another antisemitic trope.

In many ways, it seems impossible for Disney to create a villain that avoids some antisemitic trope, if avoiding stereotypically Jewish character designs only leads to affirmation of another trope. Unfortunately, it may very well be impossible. As John Appel notes in Jews in American Caricature: 1820–1914, “Jews, too, have been described as penny-pinching misers, cheats and ostentatious consumers, pushy parvenus and clannish separatists, radical unbelievers and Orthodox fanatics, ‘red’ Communists and arch-capitalists, draft evading slackers and cowardly soldiers and, more recently, bloodthirsty Israeli militarist occupiers of peaceful villages.” Whether a villain is stingy or greedy, cowardly or bloodthirsty, oddly insular or the mastermind controlling everything, they fall into a Jewish stereotype. Especially when the concept of Jews being sneaky or able to trick others comes into play, it is nearly impossible to create a villain who doesn’t hit one stereotype or another. Certainly, designs and narrative beats like the ones in Tangled make the Jewish-coding of villains far more obvious, but history’s view of Jews has permanently branded them as villainous.

That doesn’t mean that every villain is equal. Hans’ duplicity in Frozen does not raise as many alarms as the multi-layered antisemitism in Tangled. Nor does it mean that every Disney film, let alone every piece of fiction influenced by centuries of antisemitism, should be disregarded. But understanding how antisemitism has influenced Disney’s villains, and, by virtue of its films’ success and cultural dominance, impacted how the American public perceives Jews because of these portrayals, these trends can be acknowledged and criticized, instead of being willfully ignored by insisting that 90 years of cinematic history is simply a “sheer coincidence.”

Bibliography

Aladdin. Walt Disney Pictures, 1992.

“Antisemitic Caricature of a Dreyfus Supporter - Collections Search - United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.” Accessed May 6, 2023. https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn545107.

Appel, John J. “Jews in American Caricature: 1820–1914.” American Jewish History 71, no. 1 (1981): 103–33.

Brew, Simon. “Byron Howard & Nathan Greno Interview: Tangled, Disney, Animation and Directing Disney Royalty.” Den of Geek, January 28, 2011. https://www.denofgeek.com/movies/byron-howard-nathan-greno-interview-tangled-disney-animation-and-directing-disney-royalty/.

Brunotte, Ulrike. “‘All Jews Are Womanly, but No Women Are Jews.’: The Femininity Game of Deception: Femme Fatale Orientale, and Belle Juive.” In The Femininity Puzzle, 1st ed., 21–54. Gender, Orientalism and the »Jewish Other«. transcript Verlag, 2022. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv371bzpp.4.

Carnevale, Rob. “IndieLondon: Tangled – Nathan Greno and Byron Howard Interview - Your London Reviews.” Accessed April 11, 2023. https://web.archive.org/web/20151128043916/http://www.indielondon.co.uk/Film-Review/tangled-nathan-greno-and-byron-howard-interview.

Climenhaga, Lily. “Imagining the Witch: A Comparison between Fifteenth-Century Witches within Medieval Christian Thought and the Persecution of Jews and Heretics in the Middle Ages.” Constellations 3, no. 2 (May 9, 2012). https://doi.org/10.29173/cons17200.

Croxton, Frederick. “Statistical Review of Immigration, 1820-1910.” Immigration to the United States, 1789-1930 - CURIOSity Digital Collections, 1911. https://curiosity.lib.harvard.edu/immigration-to-the-united-states-1789-1930/catalog/39-990067954980203941.

D23. “Three Little Pigs (Film).” Accessed May 1, 2023. https://d23.com/a-to-z/three-little-pigs-film/.

Deja, Andreas. “Deja View: The Evolution of Jafar.” Deja View (blog), November 30, 2012. https://andreasdeja.blogspot.com/2012/11/the-evolution-of-jafar.html.

———. “Deja View: The Huntsman.” Deja View (blog), February 3, 2015. https://andreasdeja.blogspot.com/2015/02/the-huntsman.html.

———. “Deja View: The Stepmother.” Deja View (blog), October 1, 2012. https://andreasdeja.blogspot.com/2012/10/the-stepmother.html.

———. “Deja View: Twenty Years Ago...” Deja View (blog), March 30, 2013. https://andreasdeja.blogspot.com/2013/03/twenty-years-ago.html.

Desowitz, Bill. “Nathan Greno & Byron Howard Talk ‘Tangled.’” Animation World Network. Accessed April 11, 2023. https://www.awn.com/animationworld/nathan-greno-byron-howard-talk-tangled.

Diner, Hasia. Roads Taken: The Great Jewish Migrations to the New World and the Peddlers Who Forged the Way. Yale University Press, 2015. https://web-p-ebscohost-com.remote.slc.edu/ehost/ebookviewer/ebook/bmxlYmtfXzkzMzA5Ml9fQU41?sid=c8d1f3df-2c0a-4e45-bb29-d0a83e2c8fbb@redis&vid=0&lpid=lp_13&format=EB.

“Disney+ | Video Player.” Accessed February 22, 2023. https://www.disneyplus.com/video/ddc23c92-f7d2-481c-9d71-1332af3a8c4f.

Disney Censorship: Three Little Pigs 1933 Original vs 1948 Reanimated Scene, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BB1mMNvrUrM.

“Disney Does Diversity: The Social Context of Racial-Ethnic Imagery.” In Cultural Diversity and the U.S. Media. Albany : State University of New York Press, 1998. http://archive.org/details/culturaldiversit0000unse_o7p9.

Englund, Steven. “The Blood Libel.” Commonweal 150, no. 2 (February 2023): 34–38.

fantastic-nonsense. “Memories of Another World.” Tumblr. Tumblr (blog). Accessed April 27, 2023. https://fantastic-nonsense.tumblr.com/post/687550407752466432/perfectlynormalhumanbeing-as-a-jew-one-of-the.

Ford, Henry. “The International Jew: The World’s Foremost Problem,” June 12, 1920. Wikisource.

Goldberg, Ann. Sex, Religion, and the Making of Modern Madness : The Eberbach Asylum and German Society, 1815-1849. 1 online resource (x, 236 pages) : illustrations, map vols. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999. http://site.ebrary.com/id/10084824.

“Grimm 012: Rapunzel.” Accessed February 22, 2023. https://sites.pitt.edu/~dash/grimm012.html.

Hant, Myrna. “A History of Jewish Mothers on Television: Decoding the Tenacious Stereotype” 5 (2011).

Hercules. Walt Disney Pictures, 1997.

Imhoff, Sarah. “Bad Jews: The Leopold and Loeb Hearing.” In Masculinity and the Making of American Judaism, 244–69. Indiana University Press, 2017. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt2005vkq.16.

Kim, Jin. “Mother Gothel.” The Art of Jin Kim (blog), May 26, 2017. https://theartofjinkim.wordpress.com/2017/05/26/mother-gothel/.

koreatimes. “Dreams Come True, Disney Style,” May 15, 2011. https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/art/2023/04/689_87009.html.

Matteoni, Francesca. “The Jew, the Blood and the Body in Late Medieval and Early Modern Europe.” Folklore 119, no. 2 (2008): 182–200.

McCulloh, John M. “Jewish Ritual Murder: William of Norwich, Thomas of Monmouth, and the Early Dissemination of the Myth.” Speculum 72, no. 3 (1997): 698–740. https://doi.org/10.2307/3040759.

Mollet, Tracey Louise. Cartoons in Hard Times: The Animated Shorts of Disney and Warner Brothers in Depression and War 1932-1945. New York, New York, USA: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017.

Pocahontas. Walt Disney Pictures, 1995.

Putnam, Amanda. “Mean Ladies: Transgendered Villains.” In Diversity in Disney Films: Critical Essays on Race, Ethnicity, Gender, Sexuality, and Disability, n.d. 2013.

“Rapunzel by the Grimm Brothers: A Comparison of the Versions of 1812 and 1857.” Accessed February 22, 2023. https://sites.pitt.edu/~dash/grimm012a.html.

Rowe, Nina. The Jew, the Cathedral and the Medieval City: Synagoga and Ecclesia in the Thirteenth Century. Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Schüler-Springorum, Stefanie. “Gender and the Politics of Anti-Semitism.” AMERICAN HISTORICAL REVIEW, 2018.

Schutt, Tatum. “Why Do So Many Disney Villains Look Like Me?” Hey Alma, March 5, 2022. https://www.heyalma.com/why-do-so-many-disney-villains-look-like-me/.

Tangled. Walt Disney Pictures, 2010.

tangledbea. “It’s Bex, Not Bea.” Tumblr. Tumblr (blog). Accessed April 17, 2023. https://tangledbea.tumblr.com/post/687549550733492224/sigh-the-mother-gothel-is-an-anti-semitic.

Teter, Magda. Blood Libel. Harvard University Press, 2020. http://www.jstor.org.remote.slc.edu/stable/j.ctvt1sj9x.

“The Finaly Affair.” TIME Magazine 61, no. 11 (March 16, 1953): 79–80.

The Lion King. Walt Disney Pictures, 1994.

theartofjinkim. “Archaeology (IV): Tangled Early Designs!” The Art of Jin Kim (blog), December 18, 2017. https://theartofjinkim.wordpress.com/2017/12/18/archaeology-iv-tangled-early-designs.

Three Little Pigs. Short. United Artists, 1933.

“Three Little Pigs | Disney+.” Accessed May 1, 2023. https://www.disneyplus.com/movies/tangled/3V3ALy4SHStq.

Wills, John. “Making Disney Magic.” In Disney Culture, 14–51. Rutgers University Press, 2017. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1p0vkn3.4.

#Disney#Tangled#Mother Gothel#Judaism#jumblr#antisemitism#jewish#disney villains#Aladdin#Jafar#Lion King#Scar#Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs#Queen Grimhilde#Cinderella#Lady Tremaine#Sleeping Beauty#Maleficent#Three Little Pigs

187 notes

·

View notes

Text

Disney Villain Headcanons (modern au):

Jafar spends a lot of his evenings reading, probably history

Maleficent is a complete bird mom

Like Jafar, Frollo reads a lot too, except he reads theology

Frollo like cats. Don't debate me on this

Cruella and Ursula are dramatic besties

Screw it. They all read (except Gaston). HOT PEOPLE READ THIS IS NON DEBATABLE

In case you haven't noticed, Mother Gothel is the only female disney villain with curly hair (that we know of) so she goes through curly hair struggles too

Queen Grimhilde is a vegan fitness nut

Since Snow White is set in Germany, I feel like Grimhilde would really like snowy weather

Grimhilde is a selfie magent

Speaking of snow, Jafar and Iago hate the cold. Absolutely despite it. When it's cold they bundle up and all the other villains give them a hard time about it

Maleficent likes pets in general

Junk food is Ursula's fav, and Grim always gives her a hard time

Facilier and Hook are softies. They just need a hug

Grimhilde is a selfie magent

This is all I can think of right now, I'll probably make a part 2 in the future. Bye for now!

#disney#disney villains#headcanon#modern au#aladdin#hunchback of notre dame#sleeping beauty#the little mermaid#tangled#snow white#beauty and the beast#peter pan#the princess and the frog#jafar#claude frollo#maleficent#ursula#mother gothel#the evil queen#gaston#captain hook#dr facilier

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

something that will always make me kind of sad and annoyed is that half the lyrics to reflection were cut from mulan to save time, and the missing parts were never fully restored and animated like how human again (BATB) and if i never knew you (pocahontas) were added back into those movies for various anniversary releases. i added an "extended" version from youtube that combines the song from the movie with a deleted scene of the rest of the lyrics to my spotify local files years ago and then hardly ever listened to the regular movie version again because even as a kid i thought it was just too short.

#sorry i know this is kind of silly but 😭#justice for the full version of reflection smh. at least lea always sings it live#and for that matter: justice for proud of your boy from aladdin too!!#they could've animated it and reframed it as him still dreaming of making his mother proud even though she's gone now#the same way the broadway musical eventually did#and adding it back to the animated movie would've been such a beautiful tribute to howard ashman

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Botanic Tournament : Jasmines Bracket !

Round 1 Poll 4

#botanic tournament#tournament polls#jasmines bracket#round 1#himym#how i met your mother#princess jasmine#jasmine aladdin#aladdin jasmine

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

#disney#art#jasmine#princess jasmine#aladdin#Alien#Alien Aladdin#Alien Jasmine#because I am the mother of the monster.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

its wild to me how western european beauty standards even effected me as a child. my blonde, blue-eyed ass. i'd tan and come inside to look at my skin and it was "darker" in a way thats not conventionally understood as beautiful, I thought I was "supposed" to have more red and orange pigment when I tanned

like this

but instead it was more like

this and it always made me feel insecure on a subconscious level, like i wasnt the "right type of tan" or something :/

anyways, everyone with olive skin is beautiful and fuck them other color undertones sdjkhbvsfgdvghsdfhgvdfshvgfdgshv

#fuck your red undertone ass#fuck your orange undertone ass#fuck your pink undertone ass#im green bitch and im a beautiful snake man.#im the evil swarthy bad guy type of tan not the blonde preppy barbie good girl type of tan :/#THIS is why i resonate w bruno btw bc they LITERALLY DID THE THING#everyone else has these warm or neutral skin tones besides him#and they demonize him and he has the cool olive tone and hhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh#hes just like me hes just like me fr#ok well. felix has a cool undertone. BUT ITS NOT OLIVE. its like. purple-y almost.#isabellas kinda olive toned but shes a warm olive so the Good Guy olive 😒😒😒😒😒😒😒😒😒😒😒😒😒😒😒#apparently the greyer you are in complexion the more evil you get according to disney idk#no fr look at captain hook vs peter pan. look at maleficent vs sleeping beauty. look at jafar vs aladdin!#look at scar vs mufasa!!!! repunzel vs mother gothel!!!!#like!!! every villain!!!! cooler toned or cool olive toned! disney!!!! who hurt you !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!#ik its not disney but. rasputin in anastatia. fuck even like. the bad guys who wanna marry thumbelina?#a literal green ass toad. a literal blue ass beetle. a literal brown ass mole. ok don bluth who tf hurt YOU too?

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you have any thoughts on Aladdin’s mother?

So we actually do know some info about her from a tie in comic to the Aladdin tv show!

Her name is Zena, and she appears to be quite an adventuress, being a competent fighter and more then willing to go toe to toe with magical beings to accomplish her goals.

The fact that it's revealed she named Aladdin after a dog she liked 😅 makes me very much feel they were going for an Indian Jones homage, and honestly, I can really get behind that for her.

I feel like she was someone who was very willing to go against the grain of what was expected of her, and it's likely she and Cassim had a few adventures together like, Rick and Evie from the Mummy style before they settled down to have Aladdin (and then things go downhill once Cassim leaves :/ )

I think I'd like to pull in the older concepts of Aladdin's mother for her mother. Have her be a long suffering woman who wants the best for her daughter and loves her but is worried about all this adventuring and tricks and such, and Zena wants to make her proud but isnt sure how.

And maybe I'd throw in that random evil uncle of Aladdin's who shows up once in an early comic and is never mentioned again as her good for nothing brother xD Their poor mom :/

Look at this ridiculous man and his ridiculous evil mustache as he swings away while vowing his evil vengeance. Fantastic. His name is Behan Yerbak, "Behind Your Back" because why not xD

Actually yeah this makes Zena even more like Evie even more like Evie, only Jonathan is evil xD

#asks#disney#disneyverse#aladdin#aladdin's mother#disney comics#disney concept art#aladdin zena#disney parent backstory#i have another one about cassim and her together coming up#disney headcanons#disney parents

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

It was difficult not to put them all in the center

#Disney#frozen#sleeping beauty#the princess and the frog#Hercules#101 dalmatians#tangled#the little mermaid#aladdin#beauty and the beast#peter pan#Snow White#dr facilier#hades#cruella de vil#mother gothel#Ursula#jafar#Gaston#Captain Hook#the evil queen#disney villains#tbh I think hook could go in trickster

747 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Favorite Disney Villains:

1. Captain Hook

2. Scar

3. Mother Gothel

4. Jafar

5. Gantu

6. Yokai

7. Hans

#captain hook#peter pan disney#hans frozen#mother gothel#scar Lion king#scar#lion king#the lion king#captain gantu#gantu#lilo and stitch#lilo & stitch#jafar aladdin#Jafar#yokai big hero 6#professor Callahan#big hero 6#big hero six#tangled#aladdin#frozen#Disney#Yokai#disney villains#screencap#peter pan

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’ve been working backstage for the panto my friend is directing and had a sudden question: is panto something that other cultures and countries do, or is it specifically United Kingdom based?

#for those who don’t know#it’s a very camp comedy theatre production of a family tale (Aladdin Peter Pan Cinderella dick Whittington etc)#and there’s always the dame (usually the hero’s mother) in drag and the prince is normally played by a girl#and it’s musical and heavily focuses on audience participation#it’s quite raunchy but the whole family goes and watches

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

@kriscynical @evi_021 @aladdingifs Here my finished version of Sadira mom I did , What should be her name please leave comment’s?

#disney aladdin#fanfiction#fans#sadira#nevipublishing#Sadira mother#disney fanart#my artwrok#artists on tumblr#fanfic

0 notes