#The London Mozart Players

Text

When Poetry Meets Music

There’s a natural affinity between music and poetry, each using sound to create meaning and texture. Even the genius of Goethe’s poem ‘Erlkönig’ becomes more powerful when Schubert uses its words to create a Lieder.

I’m always thrilled if my work is performed or set to music. So I was delighted to hear my poem ‘Refuge’ transformed into a piece of music at this year’s Edinburgh Fringe Festival,…

View On WordPress

#Anna Kisby#Bishopstone#Claire Booker#Clare Best#contem#contemporary poetry#Edinburgh Fringe Festival#JS Bach#Keats#Mary Noonan#new poetry#Nicola Burnett Smith#poetry inspired music#Sebastian Comberti#Shelley#Sylvia Paskin#The London Mozart Players#WB Yeats

1 note

·

View note

Text

Trompeten-Sinfonie

Franz Xaver Richter (1° dicembre 1709 - 1789): Sinfonia in re maggiore VB 53, Trompeten-Sinfonie. London Mozart Players, dir. Matthias Bamert.

Allegro

Andantino [4:37]

Presto assai [8:35]

youtube

View On WordPress

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

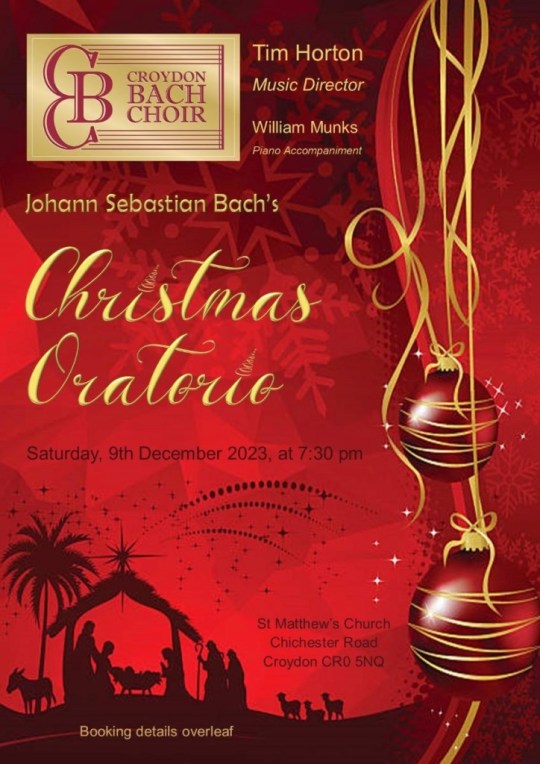

Bach-to-Bach Christmas concerts for long-established choir

The Croydon Bach Choir, one of the longest-established classical choral societies in the area, is looking for new members in all voice parts, but particularly tenors.

Over the autumn, the Croydon Bach Choir has been working towards a performance of Bach’s magnificent Christmas Oratorio, which they will be performing this Saturday, December 9, at their regular venue, St Matthew’s Church,…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-91) - Concerto No. 20 for Piano and Orchestra in d-minor, KV 466, III. Allegro assai. Performed by Melvyn Tan, fortepiano, and Roger Norrington/London Classical Players on period instruments.

#wolfgang amadeus mozart#classicism#classical music#piano#pianist#orchestra#period performance#period instruments#piano concerto#concerto#fortepiano#pianoforte#mozart#strings#string orchestra#woodwinds#band

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Move with the Melody (1/1) (jegulus)

Regulus was walking home from the library. While he had on a long coat and boots, his forgotten mitts left his hands to be bitten by the frigid air. It was sunny, but deceptively so. He could not wait for warmth of the fire to thaw his skin and a cup of tea to curl his hands around. He walked, trying not to sound too out of breath when strangers passed. As music flooded his ears, he fell too deep into the lyrics.

I watch you go, go away, go away, miles more than before

I’ll watch and wait, watch and wait, watch in place, where we were before

He blinked and brought himself out of it. If his phone wasn’t underneath his many layers he would’ve changed it. He should’ve changed it anyway but Regulus never did what he should do.

You'll settle down, settle down in your town, with new friends, to hold

Hold, hold me down, with your smile and with your frown, Oh those times were yesterday

Oh and those days, they weren't gold, they were fine, take your fool's gold

I won't settle down, for the past and not the now

I'll move on

Fuck, Regulus thought. Today was too much of James. James did live rent free in Regulus’ mind, but the eviction was long overdue. He tried to shake it away as he tugged his zipper down haughtily and searched for his phone, quickly switching it to the next. He didn’t care what played, as long as it wasn’t that.

His ears were filled quickly with a piano concerto. He sighed deeply, and took in a sharp breath of the cold air, focusing on the instruments. No. 21, he thought, hmmm C Major, Mozart obviously. He scrunched his nose, but this version was likely the London Mozart Players. He didn’t mind this version, and loved playing this piece honestly.

He focused on the music as he walked and walked, playing it over and over again until finally he reached his flat. Maybe Remus would be home and want to play chess with him. He needed to distraction, because just stepping through the doorway brought memories of James pushing him up against it. He didn’t want to think about James--couldn’t think about James. James didn’t want him anymore, and he needed to move on.

He wished he could just play through the missing him part like song, skipping it when it was too loud or too annoying or he simply did not want to hear it anymore. Everyone keeps telling him its his own fault, or well maybe its his own thoughts, he can’t really tell anymore. His thoughts spiralled into berating himself as the kettle boiled and clicked off.

He finished making his tea, his thoughts landing on: you shouldn’t even be surprised, who could love you anyways, and moved to sit at the piano. He needed to get out of himself. Aside from scratching all of his skin off, playing was the only thing that would let out the bubbling in his blood. He let his attachment, his physicality of the music, the muscles and arch of his back lead him out of his mind.

Remus came home to a terribly solemn tune, and immediately understood why. Remus moved quickly to sit with him, and the pair may have been the suffer in silence type, they often found comfort in each other’s shared silence.

By the end of the night, Remus had only asked one question: “Do you want to talk about?”

Regulus had only given one response: “It is James,”

So they both knew that meant it was better off left unsaid.

I watch you go, go away, go away, miles more than before

But I, I won't wait, I won't wait, I won't wait

I've moved on

#I watch you go by creepmouse#also creepmouse's lead singer does a mean Remus Lupin cosplay on TikTok#@writtenbyapoet#tag him if y'all are sneaky and know his tumblr#jegulus#bite me I love classical music#sunseeker#starchaser#marauders#james x regulus#fanfic#lgbtq+#break up#regulus arcturus black#regulus plays piano#remus lupin#james fleamont potter#fluff and angst

58 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Colin Bradbury, who has died aged 90, was the BBC Symphony Orchestra clarinettist whose dazzling cadenza in Sir Henry Wood’s Fantasia on British Sea Songs held audiences breathless at the Last Night of the Proms for many years. He became principal clarinet in the orchestra in 1960, and continued until his retirement in 1993.

During the 1970s, with Pierre Boulez as the principal conductor, the orchestra achieved worldwide prominence. Bradbury described it as “a unique time, musically and orchestrally – a golden age”. Away from the orchestra, he became an outstanding exponent of the clarinet’s lesser-known 19th-century repertory, in recital and on record.

He was born in Blackpool, the younger child of Jim Bradbury, a railway clerk, and his wife, Nellie (nee Cookson), both amateur singers. Encouraged to sing from an early age by his mother (his father died when he was four), Colin began to learn the piano at seven and soon bagged the only B flat clarinet at his primary school. Using his initiative, he worked out the transposition and was soon playing along with the school recorder group.

At Blackpool grammar school he started clarinet lessons with a local semi-professional, Tom Smith, and acquired a pair of simple-system Barret-action Albert clarinets. In 1947 he auditioned for the newly established National Youth Orchestra, becoming a founder member.

His sister Jean went to university, intending to become a teacher, and Colin assumed he would follow. A career in music had not crossed his mind, so when the viola player Bernard Shore came to the second NYO course to talk to young musicians intending to enter the profession, he did not attend. Ruth Railton, director of the NYO, took him for a long walk, four times around the Leys school in Cambridge, where the course was being held, and by the end he was persuaded. She went on to offer him the opportunity to play the Mozart Clarinet Concerto with the NYO at the Edinburgh festival in 1951, on condition that he left school that Easter and began studying with the clarinettist Frederick Thurston.

This he did, missing his A-levels, and started at the Royal College of Music in London in the autumn of 1951, funded by a Blackpool festival scholarship. After a year he left to join the Irish Guards, then returned to the college and completed his national service concurrently with the rest of his music studies. He won the Tagore gold medal for the best male student of his year.

During the summer of 1956 he drove an ice-cream delivery truck to get himself out of debt, having not quite paid for a 22-litre Jaguar with his earnings from a West End run of Summer Song that had folded unexpectedly.

That September, he joined the Sadler’s Wells orchestra as second clarinet, becoming principal in 1957. Playing in the pit was enjoyable, but also “frustrating for an extrovert, conceited character like me, but I learned a great deal”. He married Janet Forbes, the principal flute, in 1959.

During the 1959-60 season he began working with John Carewe and the New Music Ensemble and took part in Schönberg’s Pierrot Lunaire in the second of the new series of BBC Thursday Invitation Concerts. He was also invited to give some solo recitals for the BBC Home Service; at the first concert he played Seiber’s Andantino Pastorale and the Sonatine by Honegger.

In September 1960 he joined the BBC Symphony Orchestra (BBCSO) as principal clarinet. When the orchestra appointed co-principals in 1963, Bradbury shared the position with Jack Brymer for seven happy years. During that period, with more flexible working hours, he was able to play with other orchestras such as the LSO and the Philharmonia and take part in recordings. He also performed as a soloist, playing the Mozart Concerto, the Nielsen Concerto, the Weber Concertino and the Debussy Première Rhapsodie at the Proms.

During the 70s the structure of the BBCSO was changed and Brymer moved on to the LSO. It was during this period that Bradbury was elected chair of the orchestral committee, representing his fellow players’ interests.

In 1979, Bradbury’s old teacher, Smith, sent him his collection of amusing 19th-century pieces, the sort that the younger Bradbury had been rather snobbish about. Together with the pianist and scholar Oliver Davies, he produced The Victorian Clarinettist – the repertoire of the 19th-century virtuoso Henry Lazarus. This was followed by three more LP records: The Drawing-Room Clarinettist, The Italian Clarinettist and The Edwardian Clarinettist; selections from these LPs were reissued in CD format as The Virtuoso Clarinettist (1990), and The Art of the Clarinettist (1994).

In 1993, Bradbury retired from the BBCSO, and made the CDs The Bel Canto Clarinettist (1996), a sequence of 19th-century opera paraphrases, and The Victorian Clarinet Tradition (1998), linking Bradbury to Lazarus through Lazarus’s pupil Charles Draper, and Draper’s pupil Thurston. An interest in computer music software took Bradbury on to publishing good editions of these 19th-century works under his own imprint, Lazarus Edition.

From 1963 to 2000 he was professor of clarinet at the Royal College of Music, eventually becoming head of woodwind. His greatest joy was the RCM Wind Ensemble. Having no love of wind bands (which add saxophones and brass to woodwinds), he created a Harmonie ensemble – woodwinds and horns, as for the wind music of Mozart – which toured extensively, with visits to Japan and Vienna.

In 1999 he revived an earlier partnership with the pianist Bernard Roberts to record both Brahms sonatas together with the Hindemith Sonata. A review in BBC Music magazine commented: “Bradbury plays in a beautifully natural way without resorting to the forced rubato adopted by some artists in a contrived attempt to be different, and he allows the music to speak for itself.”

Bradbury is survived by Janet and their five children, Keith, Louise, Paul, John and Adrian, and 15 grandchildren.

🔔 Colin Bradbury, clarinettist, born 4 March 1933; died 28 May 2023

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at http://justforbooks.tumblr.com

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Francois-Joseph Gossec (1734-1829) - Symphony in F Op 12 No 6

Matthias Bamert, London Mozart Players

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

On the Force and force users and jedi...

I was actually really interested in the suggestion that being a force user (or even a Jedi) can be defined in different ways to those we've seen. Previously, we've been shown what it's like to be a trainee with innate talent, someone naturally strong in the force. So it's been like the standard thing with most fictional magic systems: it's something you Have first, and something you Do second.

I've always found this have/have not binary approach kind of... well we're taking about magic but even so, unrealistic is still the right word. Because pretty much any other skill doesn't work like that. I remember reading a Ben Aaronovitch interview where he said that he'd purposefully built the Rivers of London magic system to NOT be like that, but to be more like music: it's something that some people ARE innately better at, but it's ultimately something that can be achieved through application and work, also. Training makes everyone better; it's just that some people have a natural gift and a headstart.

And I love that analogy. Like there are the Paganinis, the "standard" Jedi we're used to, who are the hero players and soloists. Those are usual protags of the star wars stories. Anakin is like Mozart, with all the charm and raging ego to match. The Jedi order is the equivalent of a top conservatoire - they select and hone those with the biggest talent, because they're destined for particular roles and that requires a selection to find those who'll benefit from the particular training style they offer.

But where are the 10th desk footsloggers, the second violins? These are not the heroes of the story, they just did a LOT of boring practice and put in the hours until they got to a competent standard. But they also have an important role to play. Vital, even.

I think Sabine is the viola player of force users, and I say that with love (and as a violist). She's just trying to play the wrong instrument and hasn't connected enough with who she is as a "musician" to figure it out yet...

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Karajan: a new film – and the controversy continues

Tom Service

The Guardian

London, UK

Thu 4 Dec 2014 @ 03:00 EST

The conductor – who led the Berlin Philharmonic from 1956 to 1989 – is the subject of a new BBC documentary. But he remains an enigmatic figure, whose musical approach sounds a false note in today’s world.

📸 Visionary? Conductor Herbert von Karajan in 1976. Photograph: Bettmann/Corbis

Herbert von Karajan. He’s both an icon and an enigma in the story of 20th century music. Baton aloft, hair expertly coiffed, shot in soft-focus lighting from the left (he insisted he was photographed from what he thought was his best side), he is the familiar face of millions of records, videos, laserdiscs, and now DVDs and downloads, the person who arguably did more to turn symphonic music into a commodity in the postwar era. He is also the despotic maestro of imperialistic ambition, who wanted to conquer every available media possibility and turn them into publicity-generating – and commercially lucrative – opportunities for him and his orchestra, the Berlin Philharmonic.

But Karajan the man remains elusive: a conductor who didn’t – and possibly couldn’t – form friendships with the musicians he led for more than 30 years, whose political past (he was a member of the Nazi party) was a dark halo over his reputation throughout his life, and whose music-making itself, for all its gigantic success, has now become a legacy that most of today’s conductors openly repudiate. Karajan’s approach, they say, represents an ideology in which the superficial gloss, finish and perfection of orchestral sonority is an end in itself, a one-size-fits all solution for repertoires from Bach to Berg, from Mozart to Mahler, which ironed out the expressive edges of everything he conducted. Simon Rattle, for one, has talked about how he was “slightly repelled” by the Karajan sound when he heard it in the flesh for the first time, and he’s just one conductor who feels that Karajan – “the emperor of legato” – belongs to a musical world that has no place in today’s orchestral culture.

It’s all of those myths, cliches, and phenomena that John Bridcut’s new film – Karajan’s Magic and Myth, broadcast on BBC4 on 5 December – interrogates, in the BBC’s first commissioned film on the conductor, 25 years after his death. There are some fascinating moments: interviews with musicians from the Philharmonia in London in the early 1950s, from the Berlin Phil, fellow conductors Nikolaus Harnoncourt (who played as a cellist for Karajan in the Vienna Symphony Orchestra) and Mark Elder, and a handful of the starry soloists he worked with in the later stages of his career, Placido Domingo, Anne-Sophie Mutter, and Jessye Norman.

Most illuminating of all are the glimpses you’re given of a man and musician who didn’t conform to the one-dimensional caricature he has become for some: far from a dead-eyed perfectionist, Karajan actually ignored obvious imperfections, such as a magnificently obdurate fluffed note from the fourth trumpet in one of his recordings of Strauss’s Alpine Symphony, in favour of the overall sweep of a longer take in the studio – or possibly because it was cheaper not to patch it up.

Karajan’s undoubted vanity comes over as one of the strongest indictments of his personality: not just the whole left-side-is-my-best-side thing, but making sure that his principal flute James Galway wasn’t visible in his films, because Karajan didn’t like Galway’s facial hair. Conversely, he didn’t like baldness either in himself or his orchestral players, and he made follicly challenged musicians wear wigs for the filmed sessions – even if they were often invisible since the camera focused for the vast majority of the time on Karajan and his closed-eye conducting, and on the instruments rather than the actual players.

But the biggest issue of all, the question of how Karajan actually produced the performances he did, remains unanswered in Bridcut’s film, as it does in the other Karajan documentaries that have been made. There are the crazy facts of his contract with the Berliners – that they were to be at his beck and call around the clock whenever he was in Berlin, summonable at a moment’s notice for a recording, rehearsal, or film session – but even accounting for Karajan’s famed magnetism and charisma on the podium, it’s hard to completely understand how he was able to command such complete authority over his musicians and orchestral culture all over the world.

It’s possible that Karajan is a phenomenon that today’s musical culture just couldn’t tolerate (although the fetishisation of the conductor figure continues unabated; just think of the adulation, marketing and hype around Gustavo Dudamel, for example), but the other side of it is the sheer scale of Karajan’s achievement. In rejecting Karajan’s recordings, we risk underestimating both the sheer intensity and indelible power of the sound world he created, and the sophistication of what he was doing musically. He also made visionary use of the latest media.

A few examples: watch his films with Henri-Georges Clouzot, rehearsing and performing Schumann’s Fourth Symphony and Beethoven’s Fifth. Karajan and Clouzot turn the art of orchestral rehearsal and music analysis into sensual filmic experiences. Of course, Karajan is performing for the cameras, but the substance of what he is saying when he tutors the hapless student conductor is rivetingly insightful, as is his forensic, multi-dimensional explosion of the start of Schumann 4.

These are suggestions (and there are others in the surprising amount of Karajan rehearsal footage on YouTube) of an essential approach to music-making, a way of building an orchestral score and a symphonic sound world from the bottom up, so that the symphony or opera or tone poem is generated from the basics – and the bass lines – of its harmonic momentum.

Karajan seemed to feel each piece he conducted as a single sweep of musical momentum made up of interconnecting lines of melody and harmony. His closed eyes, by the way, aren’t only about a mystical communion with an internal world of the music (and an incomprehensible mode of communication for Simon Rattle, and most other conductors), but a way of recalling the score, which, it’s said, he could see in his mind’s eye, turning the pages in his imagination. He had to keep them shut, otherwise he would lose his concentration.

But it’s his physical gestures that really tell this story of what he’s doing. So often, Karajan is reaching down with his hands, moulding and kneading a kind of sonic plasma that seems to begin somewhere beneath his podium, in the bowels of the earth – or at least with the Berlin Phil’s double bass players – and emerges upwards with volcanic force. That’s why his Bruckner, his Brahms, his Sibelius, his Wagner is so thrillingly powerful, because the music seems to be made of elemental energy, not simply orchestral sonority.

Well, that’s how it seems to me when Karajan is at his best – you can hear that too, in Karajan’s essential years with the Philharmonia in the 1940s and 50s; the Beethoven cycle they made together is arguably the most exciting of all his Beethovenian surveys. And it’s worth remembering how radical Karajan’s experiments with music and film were: yes, the fixed rows of musicians seem uncomfortably like a musical-modernist version of a Riefenstahl-like sense of order and abstraction, but they are achieved with a remarkable sense of filmic possibility, and with the essential idea that classical music on film should not simply be a filmed version of concerts, but a new medium, a new kind of experience.

The best of all is a film that Karajan didn’t like, directed not by the maestro himself but by Hugo Niebeling. It’s a version of Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony, made in 1968, in which the cinematography is as powerful an interpretation of the piece as the performance, so that you feel the storm and the stream, the architecture and the physicality of Beethoven’s music with your eyes as well as your ears. Forty-six years after it was made, it’s a film that is infinitely more radical than the vast majority of classical music films made today.

A quarter century on from his death, Karajan remains a seismic figure in classical music, and even in a film of the range of Bridcut’s, the man himself remains hard to fathom. But as a new generation of listeners discover his legacy, especially in China and Japan, where his records still sell as the acme of classical music, he’s an unavoidable presence. In the questions that his life and music-making pose, you might not like him, but you have to deal with him. The Karajan controversy continues.

Karajan’s Magic and Myth is on BBC4 at 730pm on Friday 5 December, and then on iPlayer until 4 January.

#Herbert von Karajan#Berlin Philharmonic#Jessye Norman#Gustavo Dudamel#Placido Domingo#Anne-Sophie Mutter#Henri-Georges Clouzot#Hugo Niebeling#Bruckner#Brahms#Sibelius#Wagner

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

#aFactADay2024

#1124: Henri and Marius Casadesus were a violist and violinist (resp.) who wrote pieces of music and attributed them to popular composers. Marius claimed to have found the "Adélaïde Concerto" manuscript by Mozart in 1931 and re-orchestrated and performed it. it was given a place in Köchel (the standard catalogue of the aforementioned pianist's works) and recorded by Yehudi Menuhin, a renowned player. when Marius failed to present the autograph he stumbled upon, and scholars realised that Mr Wolfgang was not in Versailles at the date claimed on the original, suspicions arose, and in a 1977 copyright court case, Marius admitted to having penned it. similarly, Henri devised concertos accreditted to CPE Bach, JC of the same family, GF Handel and Boccherini. from the beginning people supposed that they could have been by Henri and he never denied it. the concerti are still often referred to in double-barrel between the two alleged artists.

Marius said the trick (called by some "a hoax ala Kreisler" (another famous and similar scandalist who pulled off Vivaldi, Corelli and others)) was almost an accident: he was trying out some tunes in a classical style ready to modernise, but noticed that they sounded like Amadeus. in the hearing, he held that he staged them to his friends and asked what it sounded like - everyone insisted that it was by he who i just named. so he rolled with it.

the reason i found this was because i'm playing one of Henri's concertos and i wondered why some albums listed Henri Casadesus while others listed the more well-known London composer. tbh it's much better than anything else the latter could have dreamed of.

0 notes

Text

🎵 My Top weekly artists as logged by last.fm:

Roger Waters (23 plays) Stornoway (23) Burning Spear (12) Zahia Ziouani & Divertimento (12) Vann, London Mozart Players, Crouch End Festival Chorus (7)

0 notes

Text

Events 10.17 (before 1950)

690 – Empress Wu Zetian establishes the Zhou Dynasty of China.

1091 – London tornado of 1091: A tornado thought to be of strength T8/F4 strikes the heart of London.

1346 – The English capture King David II of Scotland at Neville's Cross and imprison him for eleven years.

1448 – An Ottoman army defeats a Hungarian army at the Second Battle of Kosovo.

1456 – The University of Greifswald is established as the second oldest university in northern Europe.

1534 – Anti-Catholic posters appear in Paris and other cities supporting Huldrych Zwingli's position on the Mass.

1558 – Poczta Polska, the Polish postal service, is founded.

1604 – Kepler's Supernova is observed in the constellation of Ophiuchus.

1610 – French king Louis XIII is crowned in Reims Cathedral.

1660 – The nine regicides who signed the death warrant of Charles I of England are hanged, drawn and quartered.

1662 – Charles II of England sells Dunkirk to Louis XIV of France for 40,000 pounds.

1713 – Great Northern War: Russia defeats Sweden in the Battle of Kostianvirta in Pälkäne.

1771 – Premiere in Milan of the opera Ascanio in Alba, composed by Mozart at age 15.

1777 – American Revolutionary War: British General John Burgoyne surrenders his army at Saratoga, New York.

1781 – American Revolutionary War: British General Charles, Earl Cornwallis surrenders at the Siege of Yorktown.

1800 – War of the Second Coalition: Britain takes control of the Dutch colony of Curaçao.

1806 – Former leader of the Haitian Revolution, Emperor Jacques I, is assassinated after an oppressive rule.

1811 – The silver deposits of Agua Amarga are discovered in Chile becoming in the following years instrumental for the Patriots to finance the Chilean War of Independence.

1814 – Eight people die in the London Beer Flood.

1850 – Riots start, which lead to a massacre in Aleppo.

1860 – First The Open Championship (referred to in North America as the British Open).

1861 – Aboriginal Australians kill nineteen Europeans in the Cullin-la-ringo massacre.

1907 – Marconi begins the first commercial transatlantic wireless service.

1912 – Bulgaria, Greece and Serbia declare war on the Ottoman Empire, joining Montenegro in the First Balkan War.

1919 – Leeds United F.C. founded at Salem Chapel, Holbeck after the winding up of Leeds City F.C. for making illegal payments to players during World War I.

1931 – Al Capone is convicted of income tax evasion.

1933 – Albert Einstein flees Nazi Germany and moves to the United States.

1940 – The body of Communist propagandist Willi Münzenberg is found in South France, starting a never-resolved mystery.

1941 – World War II: The USS Kearny becomes the first U.S. Navy vessel to be torpedoed by a U-boat.

1943 – The Burma Railway (Burma–Thailand Railway) is completed.

1943 – Nazi Holocaust in Poland: Sobibór extermination camp is closed.

1945 – A large demonstration in Buenos Aires, Argentina, demands Juan Perón's release.

0 notes

Text

Astronomo e compositore

William Herschel (15 novembre 1738 - 1822): Sinfonia n. 12 in re maggiore (1762). London Mozart Players, dir. Matthias Bamert.

Allegro Assai

Andante non molto [4:28]

Allegro assai [6:44]

youtube

View On WordPress

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Whitgift Centre getting some new tunes from an old organ

Croydon has a working pipe organ providing music in a shopping centre, as our organs in shopping centre correspondent, DAVID MORGAN, reports

Pipe dream: your eyes are not deceiving you, it really is a functioning organ

The promo video produced by the London Mozart Players ahead of last weekend’s Mozart at the Minster concert (more than 400 people attended, since you asked, a magnificent Requiem…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

STEPHANIE COWELL joins me on my blog today. Her take on being a writer is "you are a bit like an archeologist digging a city"

Stephanie Cowell has been an opera singer, balladeer, founder of Strawberry Opera and other arts venues including a Renaissance festival and an outdoor arts series in NYC. She is the author of Nicholas Cooke, The Physician of London, The Players: a novel of the young Shakespeare, Marrying Mozart, and Claude & Camille: a novel of Monet. Her work had been translated into nine languages and adapted…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Orta Festival 2023

Giunto alla XXIII edizione, Orta Festival è un appuntamento molto apprezzato del calendario delle manifestazioni vita sulle rive del Cusio.

Il concerto d’apertura di Orta Festival di sabato 1 luglio vede come protagonista la musica di Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart e la serata si chiuderà con l’esecuzione della Serenata 48 di Čajkovskij, che riflette la sconfinata venerazione dell’autore per lo stile del tardo XVIII secolo.

Nel secondo appuntamento di domenica 2 luglio, sempre nella splendida cornice dell’Isola di San Giulio saranno protagonisti Enrico Bronzi, violoncellista tra i più importanti della sua generazione, e il suo storico collega nel Trio di Parma, il violinista Ivan Rabaglia, le viole di Francesco Fiore e Giuseppe Russo Rossi, il violoncello di Matteo Pigato e una giovanissima violinista, Misia Iannoni Sebastianini, già a capo del brillante Quartetto Werthe, per le note di György Ligeti e il magnifico Sestetto per archi Souvenir de Florence» di Čajkovskij.

È un gradito ritorno ad Orta Festival quello di Dimitri Ashkenazy, che venerdì 7 luglio avrà al suo fianco la pianista Raffaella Damaschi e il fagottista Michele Fattori che, già membro della Karajan-Akademie a Berlino, ha suonato con l’Orchestra Mozart e Claudio Abbado e collabora con la London Symphony Orchestra e la Mahler Chamber Orchestra.

È un onore ospitare Filippo Gorini, giovane interprete vincitore a soli 27 anni del Premio Abbiati, prestigioso riconoscimento della critica italiana, quale miglior solista dell’anno 2022, che sabato 8 luglio con un programma che include Ludwig van Beethoven, Johannes Brahms e la Sonata n. 20 D 959, testamento spirituale dell’ultimo Schubert.

Il giovane pianista francese Théo Fouchenneret, che ha vinto il primo premio al Concorso Internazionale di Ginevra nel 2018, venerdì 14 luglio offre un concerto che mette a confronto due mondi espressivi completamente differenti con il Quintetto op. 89 (1903-1906) di Gabriel Fauré e il

Quintetto op. 34 di Brahms.

Rossano Sportiello che si è formato in Italia, considerato dalla critica internazionale uno dei Top Stride Piano Player contemporanei a livello mondiale, sabato 15 luglio proporrà un concerto di musiche da George Gershwin a Duke Ellington.

La chiusura del festival sarà domenica 16 luglio con la violinista svizzera Esther Hoppe, acclamata dalla stampa per il suo suono, la padronanza stilistica e le interpretazioni virtuosistiche eppur sensibili e, con il suo violino del 1722, il De Ahna di Antonio Stradivari, farà ascoltare due Partite e una Sonata dall’opus per violino solo di Johann Sebastian Bach, il cui autografo risale al 1720.

L’arte di eseguire le Sonate e Partite di Bach, non si basa solo su qualità violinistiche riconducibili a un’intonazione e una tecnica perfette, dato che si deve creare una polifonia lineare su di uno strumento monodico.

Questo magnifico programma risuonerà nel luogo che più si addice alla musica di Bach, che sarà ancora una volta la Basilica dell’Isola di San Giulio.

Read the full article

0 notes