#Napoleon's Spanish disaster

Text

Article behind a paywall. Google translated this from Spanish.

link

#Manuel Godoy#Napoleon's Spanish disaster#Godoy was kind of cute if nothing else#Except in a Goya painting where he looks awful#And Goya was his friend

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Spanish Series: El Dos De Mayo 1808 - Francisco Goya (1814)

"There was an insurrection in Madrid on May 2. Thirty of forty thousand persons assembled in the streets and in houses and fired from the windows. Two battalions of fusiliers of the Guard and 400 or 500 cavalrymen brought things back to normal..."

Letter by Napoleon Bonaparte to his son, 6 May 1808

In the French emperor's view at the time, the 2nd of May was a disaster for the Spanish rebels. He would quickly learn that it was in reality a disaster for him. The ensuing Peninsular War became the disaster before the disaster of Russia, the straw that only fractured the camel's back.

One particularly interesting aspect of Goya's painting is the amalgamation between the rebels and the French soldiers. It is somewhat difficult to tell which side will emerge victorious, as one can see both French soldiers and Spaniards lying on the ground in pools of blood. The painting is chaotic, disorderly, and almost overt in its graphic depiction of gore.

Perhaps what Goya truly wanted to do was paint a very real form of war at its worst. The battles of the Napoleonic Wars were often painted with a more orderly manner of warfare, in which Napoleon sat on his horse, victorious above the fallen soldiers of the Coalition.

#spanish art#napoleon bonaparte#napoleonic wars#oil on canvas#oil painting#art#art history#francisco goya#peninsular war#painting#history

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spicy Napoleon Opinions

Because with Ridley Scott's film coming soon, now seems like a good time to put them out there.

Napoleon betrayed the French Revolution. Sure, there's a school of thought that says that it probably needed to end, but if Napoleon had used his time as First Consul to defend France, achieve peace with Britain and then transition into a democracy - basically any form of democracy - he'd rightly be regarded as a hero of liberty and the enlightenment. Instead, in declaring himself Emperor, he fundamentally betrayed everything it stood for.

Napoleon lost any right to be considered 'enlightened' when he brought back slavery and walked back women's rights. Instead it took until 1848 (ironically, under the rule of his nephew, Louis-Napoleon, soon to be Napoleon III) for France to finally abolish slavery, over a decade after Britain.

Despite this, Napoleon was not Hitler. That's a common bit of hyperbole. What Hitler did was almost unique in history, in that he planned and executed an industrialised genocide right down to the train timetables. Napoleon, for all his faults, wasn't generally genocidal.

At worst, the wars between Napoleon and the Coalitions were between morally equal parties. By the time Napoleon invaded Spain, he was morally the worst of the two. The war of 1805-07 can at least be said to have been forced on France by Britain, Austria and Russia. This can't be said for the invasion of Spain and later of Russia, which were acts of naked aggression whatever the geopolitical rationale.

Napoleon would wipe the floor with Washington. It wouldn't even be close. I have no idea what Deadliest Warrior was thinking. (Then I realise they tried to argue that gatling guns were superior to machine guns and I remember they probably just fixed it in favour of the Americans.)

The Napoleonic Wars were won and lost in Spain. Okay, this is a bit hyperbolic, but the 'Spanish Ulcer' was a quagmire that deprived Napoleon of valuable reinforcements at critical moments and influenced his decision-making process in 1812 (leading to the Russian disaster.)

And while we're on this period...

Andrew Jackson might be the most overrated general in American history. Congratulations, you defended a fortified position against an enemy advancing frontally across a marsh. Bravo. Anybody could have done it, and that the Battle of New Orleans propelled such an odious figure to national prominence is a crying shame.

36 notes

·

View notes

Note

For the ask game: 31, 61, 62 and 98?

Asks come from this post: https://www.tumblr.com/soapkaars/742324378777403392/weird-asks-that-say-a-lot

31. what outfit do you wear to kick ass and take names?

I think I love this question now because I went through my selfies and I found so many fun outfits I’ve worn that I feel so much better about myself now! It’s hard to pick a favourite, but I think my favourite outfit range is between divorced Parisian femme and con-artist/disgraced nobility masc

61. favorite line you heard from a book/movie/tv show/etc.?

Oh there are so many great films I’ve seen that it’s hard to choose one but here are few that I often mutter to myself:

‘Impossible? Napoleon said that word isn’t French!’ (Dr Gogol, Mad Love)

‘Morirá!’ (He will die) ‘murió’ (he died) ‘ha muerto’ (he is dead) from a video art installation by two old Spanish artists who shown sitting on two plastic chairs and listing off all the celebrities who had died or who will die

‘Tell their mother they’re doing quite well and they will leave us soon, yes they will be going on a journey… how did Shakespeare say it? Ah yes, From which no man returns.’ (Abbott from The Man Who Knew too Much, said with a typical Peter Lorre shit-eating grin)

The whole cerulean sweater speech from The Devil wears Prada

62. seven characters you relate to?

Definitely Abbott from the Man Who Knew too Much, that man is goals… as well as David Suchet’s Hercule Poirot. I’ve even got the arrogance and grandiosity down pat! For the rest I relate too much to loser men like Marcello Mastroianni in Eight and a Half and Joel Cairo from the Maltese Falcon. Other characters would be terrible women like Miranda Priestly from the Devil Wears Prada, Cruella de Ville (she only wanted to fulfill her vision of a fur coat made from puppies!), and Helen Sharp from Death Becomes Her (played by Goldie Hawn!)

98. favorite historical era?

Oh definitely the Weimar era - I am in love with Dadaism and artists like George Grosz and Otto Dix from that period of time. It fascinates me to no end and almost all of the art movements from that time have been a huge influence on my own style of drawing and art. Other close contenders are late 17th century Netherlands (1672, the ‘disaster year’ when the country was invaded by the French and a prime minister was eaten up by an angry mob who were also part of a coup d’etat carried out by the Prince of Orange), the French Revolution, and the Cold War era, particularly from the 70s to the 80s with the rise of counterculture and the fall of the Berlin Wall which released an explosion of art, design, architecture (post modernism babeyyyy!!)… I have this fascination with periods of transition and I always love learning more and more about them!

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Joseph’s correspondence of 1810

I’ve just given this chapter in DuCasse’s edition a closer look. From what I have counted, out of a total of 176 letters we have

44 written by Joseph

2 adressed to Joseph

and 130 neither to nor from Joseph.

Out of those written by Joseph

21 were adressed to Napoleon

16 to Julie

5 to Berthier

2 to others

Those not coming from or sent by Joseph were written by:

Napoleon: 92

Soult: 17

Berthier: 9

others: 12

Obviously this cannot be right. But where’s the rest? Even if we count Soult’s missives (mostly reports to Berthier) as coming from Joseph: Where are all the reports adressed to the king, the administrative decrees, Joseph’s orders to his officials and the generals who - at the beginning of 1810 - still were under his command?

Was all of this lost during the disaster of Vittoria? Was it left behind in Madrid? Captured by the Brits? Is it in London? Has it been burned by the insurgents? Or has it already been published elsewhere?

In any case this does not feel like the correspondence of Joseph Bonaparte but rather like the correspondence of Napoleon, Spanish edition.

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

Could I have a fun fact on this lovely Friday, please?

Today You Learned about Agustina of Aragon!

In Spain, during the Siege of Zaragoza by Napoleon’s forces in 1808, things were pretty dire. The French army was storming the city, getting in close to the defenders’ artillery lines. Agustina went to the Spanish soldiers to deliver food, but she witnessed them getting gored by French bayonets and fleeing in terror. What’s a woman to do?

Well, if you’re Agustina, you light the cannon fuse and open fire on the invading French.

The Spanish defenders, touched and inspired by her courage, regained their wits and took back their posts. They temporarily managed to drive off the invaders. It didn’t last–eventually the city was captured, and the Spanish were killed or imprisoned, including Agustina, but she had already become an inspirational figure in the war.

And she wasn’t done. Legend says that her son was also in captivity with her and died, and, deciding she had enough of crappy French food, Agustina busted out of prison. She became a fighter for the resistance against Napoleon’s forces. She and other rebels got support from Wellington’s forces as the war went on.

There are stories that she was the only female captain by the end of the war, but I think that’s just legend. But Agustina WAS an inspiration to the Spanish people, both at the time and since, and she remains a folk heroine to this day. She is the only recognizable figure in Goya’s Disasters of War print series, and had a self-titled silent film in the late 20’s. She’s often called “the Spanish Joan of Arc.”

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Events 12.24

502 – Chinese emperor Xiao Yan names Xiao Tong his heir designate.

640 – Pope John IV is elected, several months after his predecessor's death.

759 – Tang dynasty poet Du Fu departs for Chengdu, where he is hosted by fellow poet Pei Di.

1144 – The capital of the crusader County of Edessa falls to Imad ad-Din Zengi, the atabeg of Mosul and Aleppo.

1294 – Pope Boniface VIII is elected, replacing St. Celestine V, who had resigned.

1500 – A joint Venetian–Spanish fleet captures the Castle of St. George on the island of Cephalonia.

1737 – The Marathas defeat the combined forces of the Mughal Empire, Rajputs of Jaipur, Nizam of Hyderabad, Nawab of Awadh and Nawab of Bengal in the Battle of Bhopal.

1777 – Kiritimati, also called Christmas Island, is discovered by James Cook.

1800 – The Plot of the rue Saint-Nicaise fails to kill Napoleon Bonaparte.

1814 – Representatives of the United Kingdom and the United States sign the Treaty of Ghent, ending the War of 1812.

1818 – The first performance of "Silent Night" takes place in the church of St. Nikolaus in Oberndorf, Austria.

1826 – The Eggnog Riot at the United States Military Academy begins that night, wrapping up the following morning.

1846 – British acquired Labuan from the Sultanate of Brunei for Great Britain.

1865 – Jonathan Shank and Barry Ownby form The Ku Klux Klan.

1868 – The Greek Presidential Guard is established as the royal escort by King George I.

1871 – The opera Aida premieres in Cairo, Egypt.

1906 – Reginald Fessenden transmits the first radio broadcast; consisting of a poetry reading, a violin solo, and a speech.

1913 – The Italian Hall disaster in Calumet, Michigan results in the deaths of 73 striking workers families at a Christmas party participants (including 59 children) when someone falsely yells "fire".

1914 – World War I: The "Christmas truce" begins.

1918 – Region of Međimurje is captured by the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes from Hungary.

1920 – Gabriele D'Annunzio surrendered the Italian Regency of Carnaro in the city of Fiume to Italian Armed Forces.

1924 – Albania becomes a republic.

1929 – Assassination attempt on Argentine President Hipólito Yrigoyen.

1929 – A four alarm fire breaks out in the West Wing of the White House in Washington, D.C.

1939 – World War II: Pope Pius XII makes a Christmas Eve appeal for peace.

1941 – World War II: Kuching is conquered by Japanese forces.

1941 – World War II: Benghazi is conquered by the British Eighth Army.

1942 – World War II: French monarchist, Fernand Bonnier de La Chapelle, assassinates Vichy French Admiral François Darlan in Algiers, Algeria.

1943 – World War II: U.S. General Dwight D. Eisenhower is named Supreme Allied Commander for the Operation Overlord.

1944 – World War II: The Belgian Troopship Leopoldville was torpedoed and sank with the loss of 763 soldiers and 56 crew.

1945 – Five of nine children become missing after their home in Fayetteville, West Virginia, is burned down.

1951 – Libya becomes independent. Idris I is proclaimed King of Libya.

1952 – First flight of Britain's Handley Page Victor strategic bomber.

1953 – Tangiwai disaster: In New Zealand's North Island, at Tangiwai, a railway bridge is damaged by a lahar and collapses beneath a passenger train, killing 151 people.

1964 – Vietnam War: Viet Cong operatives bomb the Brinks Hotel in Saigon, South Vietnam to demonstrate they can strike an American installation in the heavily guarded capital.

1964 – Flying Tiger Line Flight 282 crashes after takeoff from San Francisco International Airport, killing three.

1966 – A Canadair CL-44 chartered by the United States military crashes into a small village in South Vietnam, killing 111.

1968 – Apollo program: The crew of Apollo 8 enters into orbit around the Moon, becoming the first humans to do so. They performed ten lunar orbits and broadcast live TV pictures.

1969 – Nigerian troops capture Umuahia, the Biafran capital.

1971 – LANSA Flight 508 is struck by lightning and crashes in the Puerto Inca District in the Department of Huánuco in Peru, killing 91.

1973 – District of Columbia Home Rule Act is passed, allowing residents of Washington, D.C. to elect their own local government.

1974 – Cyclone Tracy devastates Darwin, Australia.

1994 – Air France Flight 8969 is hijacked on the ground at Houari Boumediene Airport, Algiers, Algeria. Over the course of three days three passengers are killed, as are all four terrorists.

1996 – A Learjet 35 crashes into Smarts Mountain near Dorchester, New Hampshire, killing both pilots on board.

1997 – The Sid El-Antri massacre in Algeria kills between 50 and 100 people.

1999 – Indian Airlines Flight 814 is hijacked in Indian airspace between Kathmandu, Nepal, and Delhi, India. The aircraft landed at Kandahar in Afghanistan. The incident ended on December 31 with the release of 190 survivors (one passenger is killed).

2003 – The Spanish police thwart an attempt by ETA to detonate 50 kg of explosives at 3:55 p.m. inside Madrid's busy Chamartín Station.

2005 – Chad–Sudan relations: Chad declares a state of belligerence against Sudan following a December 18 attack on Adré, which left about 100 people dead.

2008 – The Lord's Resistance Army, a Ugandan rebel group, begins a series of attacks against civilians in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, massacring more than 400.

2018 – A helicopter crash kills Martha Érika Alonso, first female Governor of Puebla, Mexico, and her husband Rafael Moreno Valle Rosas, former governor.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

BLOG 6

Comment on Readings

Chapters 2-3 from Susan Sontag's Regarding the Pain of Others (2004) and

Judith Butler's blog post "Precariousness and Grievability—When Is Life Grievable?" (2015)

In the late 19th century, the agonies of the battlefield became present as never before to those who read about them only in the press, and it was thought that one could know what happened daily worldwide. Despite this, it was not like one could really know what happened in the whole world in this way, just by reading newspapers. And the same holds for our times. The first important wars of which there are accounts by photographers are the Crimean War and the American Civil War. However, photographs of conflicts usually depicted the aftermath, such as landscapes left after warfare. It was the Spanish Civil War (1936-39) the first to be covered in the modern sense by professional photographers in the towns under bombardment, whose content could be found immediately in newspapers in Spain and abroad.

In the early 19th century, a famous concentration on the horrors of war and the crude actions of soldiers is Los Desastres de la Guerra (The Disasters of War) – a sequence of 83 prints created between 1810-1820, by Spanish painter and printmaker Francisco Goya – first published in 1863. This collection shows the atrocities committed by Napoleon's soldiers who invaded Spain in 1808. Goya's images attack the viewer’s sensibility, moving them almost to horror. The cruelties shown in Los Desastres de la Guerra are intended to shock, wound, and awaken the viewer. All the embellishments portraying war as a spectacle have been removed: the landscape is barely sketched, creating an atmosphere of a darkness.

Since it it so profound, original, and demanding, Goya's art marks a turning moment in the history of moral feelings and of sorrow. While the caption of a photograph is traditionally merely informative and neutral (a name, place, or date), and the image is an invitation to look, Goyas’s captions point out the difficulty of only looking. Every image in Goya's print series has a brief caption lamenting the evilness of the invaders, and the inhumanity of the pain they caused. Provocative phrases ask the viewer questions as “can you bear to look at this?”. With Goya, a new “standard for responsiveness” to pain is introduced.

According to S. Sontag, there is a link between photography and death, as there is always a little bit of the element of death present in any picture depicting people. Since the invention of the cameras (1839), photography has gone hand in hand with death. Being the audience of the suffering occurring elsewhere is a “quintessential modern experience”. It is precisely modernity and mass media that have brought mediated spectatorship. Before the advent of mass media, spectatorship of pain was not possible in this way. Camera's reach was limited, until the camera evolved to be equipped and portable, allowing close shots from a distant point, gaining superiority over verbal tools in delivering the horror of mass killings. In modern times, when we are surrounded by information and imagery, a photograph is a quicker and more impactful mean of apprehending something and remembering it. In other words, images stick to our minds and memories better than words. Obviously, language has a weight, but pictures are more eye-catching, thus, they shock in a different way, through an element of trigger and surprise.

Sontag refers to today’s wars as “living room” wars because they are made of sounds and sights, and people can follow them from the comfort of their couch on their living room. The argument is that violence leads to audience, and to a response in some cases. The most compelling news has always been war. Spreading awareness about what happens in other countries draws attention on, and shapes, violence and wars. This is because the understanding of war in people that have not experienced it is a product of the impact that the news and images circulating have on them. The knowledge of the pain going on in other places is constructed. In this sense, an event becomes real to those who are not physically there as a result of watching news and photographs. As long as one does not get informed about a war, by seeing pictures, it is like it does not feel real; thus, they are less affected and touched by it. Nevertheless, experiencing agonies and tragic events rarely look like how they are depicted. Just as stated above that one could not really know what happened just by reading newspapers, the same holds for photographs, if not worse. An image is considered fake when it deceives the viewer about the scene it portrays. Many of the iconic news images from the past – including some of the most remembered photos of WWII – were found to have been staged. In the era of digital photography, with Photoshop and applications to edit pictures, it is easier than ever to make manipulate photographs in order to misrepresent conflicts.

The image as shock can soon become cliché image. The understanding of war mediated by cameras is characterized by shocking images of ruin or atrocities that become “ultra-celebrated”, becoming familiar to most people. This can end up anesthetizing the viewer, who becomes always less and less shocked by images of this kind.

Pictures of tragic events are perceived as more authentic if they do not look lighted and composed, while photographs that look not edited seem less manipulative. All images of pain widely circulating are under that suspicion, thus are less likely to spark empathy and compassion easily. A photograph’s meaning and the viewer's response depends on how the picture is read or misread, identified or misidentified; ultimately, on words. For this reason, in the past, on newspapers it was the picture to accompany the story, but later, the war photograph published in a newspaper was surrounded by words. It is the interpretation, or sometimes misinterpretation, of a picture that makes a difference. The intention that the photographer has in mind when taking the picture does not determine the meaning of the photograph, which rather will be dictated by the emotions, sympathies, and biases of the various groups that see it. For example, some people do not question the motivations given by the government for waging or continuing a war. It takes some particular circumstances for a war to become unpopular. If a war becomes criticized, the content of the conflict gathered by photographers can play an important role. For example, antiwar photographs – thought by someone to unmask the harsh reality of the war – might be read by someone else as showing heroism of young men doing their unpleasant duty in a necessary struggle, fighting for victory.

Memory is mostly local, and also memory of war, in the sense that people of a nationality will remember very well a genocide committed against their people. However, most wars do not acquire the fuller meaning necessary for it to become subject of international attention, that is being regarded as an exception, representing more than the clashing interests of those soldiers.

This is enough to understand that there are some sufferings that are perceived as more shocking, and others less. For instance, the suffering often deemed worthy of representation is those understood to be the product of human evil, as opposed to suffering from natural causes, as childbirth illnesses, which is rarely represented in art’s history, and perceived as destiny beyond contesting.

According to Butler, recognizing that a life can be injured, and destroyed, implies to acknowledge that a life is finite – the certainty of death soon or later – but also its precariousness, meaning that a life requires certain social and economic conditions to be sustained. Everyone potentially has the power to be destroyed and to destroy. In a way, humans are bound one to another in this precariousness: "we are all precarious lives". Given that a human being might die, it must be cared for in order for it to survive. The worth of life only becomes apparent when the loss of life would actually matter. Therefore, grievability is a prerequisite for a meaningful life. This raises the question of whose lives are regarded as valuable, mourned, and whose are deemed ungrievable. During armed conflict, populations are split into those grievable and those ungrievable. Ungrievable existences are those that cannot be mourned because they have never counted as a lives in the first place. From the viewpoint of those who wage war to defend the lives of some communities – even if by taking lives of others — we can see the world's division into grievable and ungrievable lives.

From a political point of view, the uneven distribution of public grief is incredibly important. Open mourning is linked to outrage, which in front of unjust treatment and loss is a huge political tool. Open grief and outrage bring affective reactions controlled by power structures, and in some cases subject to censorship. For instance, following 9/11 attacks, graphic images of the victims appeared in the media with names, biographies, and the reactions of the relatives. Since public grieving was dedicated to make these images iconic for the country, there was way less public grieving for non-US citizens, and zero for people working illegally.

Similarly, despite the differences of the contexts, when Abu Ghraib photos depicting torture carried out by US personnel were first made public in the US, conservative television figures claimed that it would be anti-American to broadcast them. For them, the public was not meant to have access to such graphic evidence and have knowledge of US's human rights violations, nor knowledge about what was going on during the war. Knowing that it would cause the public to turn against the war in Iraq, those trying to reduce the power of the photographs were attempting to reduce the power of outrage.

Certain interpretive frameworks have the power to subtly control our moral reactions that initially manifest as affect. According to Talal Asad, under some circumstances, we experience more horror and moral revulsion when faced with the loss of some lives, compared to others' lives. How we perceive the world has an impact on how we feel, and the way in which we interpret our feelings alter the feeling itself. This raises the question of whether recognizing that interpretive schemes shape affect can help us understand why we experience horror in response to some losses, but indifference in response to others. In the current climate of conflict and nationalism, individuals tend to feel that their life is bound with those with whom they share national identity, who are identifiable with us, and who adhere to certain culturally specific ideas. This framework works by implicitly making a difference between the populations seen as threatening one's life, from populations on which one's life relies. For example, in the case of Rodney King’s beating by the police, taken by the racist interpretative framework, King was seen by the white paranoid audience as a threat just for being a black man. Thus, the court did not empathize with his pain. Even worse, King's suffering inflicted by the police’s violence was understood as just and necessary.

Think about how this applies to the Western perception that Islam is "barbaric" and has not yet attained the civilization standards. The deaths of those killed do not fill Westerners with the same outrage as the deaths of people who share the same nationality or religion because they considered as not fully human. A further recent instance is provided by Europeans being more touched and showing more support to victims of the war in Ukraine – since Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022 –, with large coverage in Western media than it has ever been shown for other ongoing conflicts outside of Europe. People in European countries, even unconsciously, tend to feel more moral outrage for losses of Ukrainian lives than for example victims of war in Yemen, due to the fact that they feel closer to Ukrainians, as being more geographically close, and supposedly sharing the same European values and background. For example, CBS News senior foreign correspondent Charlie D’Agata claimed that Ukraine “isn’t a place, with all due respect, like Iraq or Afghanistan, that has seen conflict raging for decades. This is a relatively civilized, relatively European – I have to choose those words carefully, too – city, one where you wouldn’t expect that, or hope that it’s going to happen”. The Guardian article "They are ‘civilised’ and ‘look like us’: the racist coverage of Ukraine" by Moustafa Bayoumi deals with the problem that many seem to think that Ukrainians are more deserving of sympathy than Afghans and Iraqis.

Although some populations are portrayed as threats to life by the rationale of self-defense, they are living populations with whom cohabitation implies a certain degree of interdependence. As Butler puts it, war tries to deny the unavoidable ways in which we are all dependent on one another, exposed to the destruction of the other, and in need of protection through international agreements founded on the recognition of "shared precariousness".

1 note

·

View note

Text

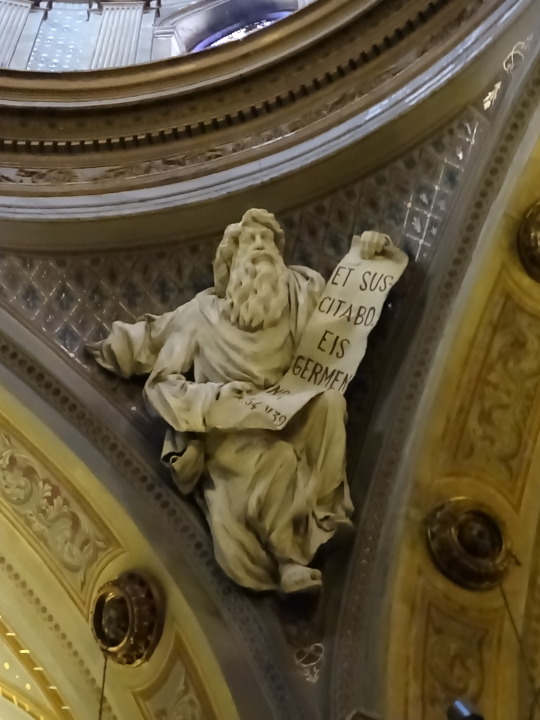

Solsona Cathedral, Spain (No. 6)

There is evidence of a pre-Romanesque temple dating 977. the Romanesque church was consecrated in 1070 and it is stated that it was “a most famous temple in the entire world”. From this time the three apses, the bell tower, some pieces from the cloister, the cellar and the canons’ dining hall, (these days used for different events) have been preserved.

The cathedral today is Gothic and it was begun at the end of the 13th century and finished in the 17th century and finished in the 17th century. On the left of the transept there is the chapel of Mercè with a Baroque altar from the artist Carles Morató. On the right there is the venerated image of la Marededéu del Claustre from the 12th century and catalogued as one of the most important Catalan Romanesque sculptures.

It is easy to imagine the upheaval that the creation of a bishopric in Solsona in 1593 meant for the beautiful medieval Collegiate Church of Santa Maria, which was now to become a cathedral, particularly in regard to renewal of ornamental elements and the making of new altarpieces.

THE HIGH ALTAR (DEDICATED TO THE VIRGIN MARY)

The high altar dedicated to the Virgin Mary was commissioned from the Majorcan sculptor Miquel Vidal (1634), but it was not completed, except for six large panels sculpted in low relief from the predella, which are conserved in the Solsona Diocesan and Regional Museum. Nor does anything remain of the second high altar, commissioned from Jacint Morató in 1730: the dreadful fire caused by Napoleon’s troops in 1810 destroyed it along with many other works. Following this disaster a new high altar was made (1854-1856), the third. However, it was short-lived, as it too was burnt during the Spanish Civil War. Fortunately, six of eight paintings by the distinguished Nazarene artist Claudi Lorenzale survived.

THE CHAPEL OF OUR LADY OF MERCY AND THE SACRISTY FURNISHINGS (TWO BAROQUE WORKS THAT SURVIVED THE FIRE OF 1810 AND THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR)

Only two sets of works from the modern period escaped the fire of 1810 and the later ravages of the Spanish Civil War on the cathedral. These are the Chapel of Our Lady of Mercy and the walnut cupboard and drawers in the canons’ sacristy. The first contains the dynamic altarpiece sculpted around 1750 by Carles Morató, although the sculptural elements were lost. The sacristy holds a beautiful cupboard with painted doors and the reliquary busts of Saint Victoria and Saint Secunda, of fine quality. Unfortunately, the artist is unknown. However we do know that the author of the colourful doors of the reliquary cupboard was Antoni Bordons.

THE CHAPEL OF OUR LADY OF THE CLOISTER

The Chapel of Our Lady of the Cloister (1727-1776), designed to house the prized Romanesque carving, was destroyed on several occasions. Its complex construction, which was also to have an altarpiece and mural paintings, was commissioned from Jacint and Carles Morató—who worked in collaboration with sculptor Josep Sunyer i Raurell. It disappeared due to damage incurred in 1810, 1822 and 1936, but from old descriptions one gathers that it must have been a most impressive example of Catalan Baroque.

OTHER NOTEWORTHY ELEMENTS FROM THE MODERN PERIOD

Elements that should not escape our notice are the modest baroque reredos at the foot of the nave, the work of Isidre Clusa, classical in style and decorated with naive reliefs showing from the life of Saint Martin, originally from the Church of Sant Martí de Riner, although it is disconcerting to see it now topped by a Saint Michael; and the fine groups of sculptures decorating the cathedral’s late eighteenth-century facades, with representations of ‘The Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary’ (1768) and ‘The Ecstasy of Saint Augustine’ (1780).

Source

#Cathedral of Santa María de Solsona#Cathedral of Solsona#España#Southern Europe#Nucli antic#travel#original photography#vacation#tourist attraction#landmark#architecture#cityscape#exterior#detail#old town#summer 2021#Northern Spain#interior#tree#courtyard

1 note

·

View note

Text

Worthy Brief - April 14, 2023

Stand on the wall!

Ecc. 1:5-6;9 The sun rises and the sun sets, and hurries back to where it rises. 6 The wind blows to the south and turns to the north; round and round it goes, ever returning on its course. 9 The thing that hath been, it is that which shall be; and that which is done is that which shall be done: and there is no new thing under the sun.

This week could be prophetically significant as events are unfolding throughout the world.

The writer of Ecclesiastes was aware of cycles in nature, how they repeat themselves. Some have noticed another interesting historical cycle that awakens our awareness at this time of year. The dates April 15th-21th contain an interesting pattern. This is a time frame that has seen the birth of much havoc in the world. Historically this is when the birth of Rome and the Roman empire took place, the birth of Napoleon, and the birth of Hitler and Nazi Germany occurred. Currently, in our day, Iranians will celebrate the birth of their leader Ali Khamenei who has called for the annihilation of the Jewish state on April 19th.

This time frame is also key in American history as these dates mark times when wars have begun; among them, The Revolutionary War, the Civil War, the Mexican-American War, and the Spanish-American War.

Historically, this time frame also includes when Abraham Lincoln was assassinated, the Titanic sank, America abandoned the gold standard, the Waco Branch Davidian debacle, the Oklahoma City Bombing, the Columbine High school massacre, the Virginia Tech shootings, the Boston Marathon bombing, and finally, the ecological disaster of BP Oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico.

Anniversaries can be positive, and awaken joyful memories, or…they can recall difficult moments which cause us to brace inwardly and wonder if some kind of trouble will arrive once again. God is the Lord of history and His purposes stand for our good in any case, so we needn't fear the future under His care. During this season when much trouble has been seen in history, let us be watching and ready to stand in the gap and to unleash prayers as the need arises -- for truly it is the season for believers to standing on the wall.

Your family in the Lord with much agape love,

George, Baht Rivka, Obadiah and Elianna (Going to Christian College in Dallas, Texas)

Arad, Israel

Editor's Note: Worthy Wrap-Up Episode recorded from Israel: Convergence of Events … Is this a water breaking moment? - https://worthynews.us12.list-manage.com/track/click?u=b94ae97bb66e693a4850359ec&id=9174afb092&e=546629276c

0 notes

Text

16th January

The Burial of Sir John Moore by Charles Wolfe

Wolfe’s poem became a staple in English public and private schools in the nineteenth and early twentieth century. It relates the burial of Sir John Moore, general in charge of the British army in Spain during the Napoleonic wars. Moore was killed at the battle of Corunna which took place on this day in 1809 and was hailed as a hero by British public opinion. Wolfe’s poem did much to cement Moore’s status as a fallen heroic figure. The first four stanzas of the poem follow below.

The Burial of Sir John Moore. Source: Look and Learn magazine stock images

The Burial of Sir John Moore

Not a drum was heard, not a funeral note,

As his corse to the rampart we hurried;

Not a soldier discharged his farewell shot

O’er the grave where our hero we buried.

We buried him darkly at dead of night,

The sods with our bayonets turning;

By the struggling moonbeam’s misty light

And the lantern dimly burning.

No useless coffin enclosed his breast,

Nor in sheet nor in shroud we wound him,

But he lay like a warrior taking rest

With his martial cloak around him.

Few and short were prayers we said,

And we spoke not a word of sorrow;

But we steadfastly gazed on the face that was dead,

And we bitterly thought of the morrow.

The battle of Corunna in Galicia took place at the end of a British fighting retreat across Spain, pursued by a French army under Marshal Soult. The British were able to repel French attacks allowing the army to evacuate back to England, but Moore was killed during the fighting. Despite the attempts to promote Corunna as a glorious retreat and Moore as a tragic hero, the Spanish campaign of 1808/09 was one of the biggest disasters in British military history.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Ikevamp AU where everything is the same except no one really understands French.

The only ones who can consistently speak French are the French Fries (Napoleon, Jean and Charles) and Comte.

Mozart and Faust still talk in so much German and they are so happy to find each other so they can finally speak in German to someone. But Mozart will think and speak in German until he finally hears someone speaking in French and he's like "ahh yes...I'm in this horrible country"

Leonardo almost only speaks Italian. To himself. To Comte. To anyone. It takes him a moment to understand why no one can understand him, because he is going OFF in Italian and no one can even keep up even if they knew Italian.

Luckily the brothers can still speak dutch. Theo is better at French than Vincent since he goes out and works. It takes Vincent a minute or two to process and translate in his head, so occasionally Theo has to translate something for him (yes ik Vincent lived in France before he died but idc)

Arthur's Scottish accent gets in the way and no one can tell me otherwise. There's words he simply can't say no matter how hard he tries. But if he happens to be in a conversation while trying to write, he can't process both languages simultaneously, so sometimes he starts typing in French and it messes everything up.

Isaac is a disaster while teaching and grading papers. He can solve all these damn equations but please don't speak to him. Not only because of his anxiety but because when he doesn't know the French word, he says the English word without hesitation. He will be grading papers and start writing notes in English. Or he won't know a French word and has to go to Napoleon. His students are also helping him get better with French.

Dazai learned Spanish instead of French and that head canon is staying with me until I die. However he's oddly good at French. He learned it very quickly but can have a hard time writing in anything other than Japanese.

Will forgets French so much. He's alone in this Villa, with only Puck. If it wasn't for the theater he would forget everything he's learned. He goes out into town speaking English until he suddenly remembers where he is.

Sebastian has too many languages going on in his head. He knows French very well but in the morning after just waking up it takes him longer to process and translate.

VLAD. OHMYGOD he knows as much French as a 4 year old French child. He's horrible at French. In the morning he's reading the newspaper and is yelling in Romanian how those aren't even words and every morning Charles has to explain to him that they are in France.

Faust needs his morning coffee before he can process anything that isn't German. Most of the Castle is yelling in Romanian and German and occasionally some French.

Jean actually has a bit of a hard time with "modern" french. It's different from what he's used to and there's a lot of new words he doesn't know. So technically he is still learning too

#ikevamp#ikemen vampire#ikevamp mozart#ikevamp vincent#ikevamp theo#ikevamp arthur#ikevamp dazai#ikevamp jean#ikevamp shakespeare#ikevamp comte#ikevamp faust#ikevamp Napoleon#ikevamp charles#ikevamp leonardo#ikevamp isaac#ikevamp vlad#ikevamp sebastian

211 notes

·

View notes

Text

Encanto history head-canons Bc I can’t imagine a family of basically Gods who had it drilled into their heads since they were young they had to use their gifts to help and service people just hung out when they were alive during two world wars, even if Colombia never sent actual soldiers into battle during either war

In addition to Spanish being their native language, Pepa speaks French, Julieta speaks Italian, Bruno speaks German, and Alma speaks Russian and English. She made them all learn different languages when WW1 broke out and she was concerned about an influx of refugees not being able to speak Spanish that well and she wanted to make sure they were taken care of as well if they found themselves in the Encanto. When WW2 broke out she also made the entire family, in laws and grandchildren included, learn Hebrew for the same (heartbreaking) reason

The worst blizzard in Russian history happened twice. When Napoleon tried to invade, and when Hitler tried to invade. The first time was natural. The second was Pepa sneaking into Russia and forcing herself to imagine her children and husband dead to stop him

The medics could not, for the life of them, figure out how a teenage girl in WW1 and then untrained woman in WW2 was a better nurse then every single trained military surgeon and medic, or how she could bring people back from the brink of death in a matter of minutes (or why she carried around a shit ton of arepas in her pack)

Bruno did his best to share the future and let the Allied leaders know which way the battles would go without letting them know he could tell the future but the first time a general ignored him and got his entire platoon slaughtered, Bruno couldn’t take that amount of guilt and heartache again so he just shared his visions with Julieta and Pepa so they could know when and where they needed to be to help

Camilo wanted to go to Germany with his mother and Tia. He was a shapeshifter, do you know what kind of amazing spy he would make and fuck up different orders? Alma was all for it but Pepa and Felix refused and threatened to cut Abuela out of their and their kids lives if she sent Camilo overseas without their permission

Dolores and Isabela also wanted to help but their parents all agreed they were also too young. When they pointed out the triplets were only 16 when they were sent to help during the first war, they agreed they could come help when they were 16. They considered the fact that VE Day happened 3 months before Isabela turned 16 and 5 months before Dolores turned 16 nothing short of a miracle

You would think 16-18 year old Pepa around a bunch of young good looking GIs would be a recipe for disaster but she had her boyfriend Félix waiting for her at home. It was actually Julieta who fell in love with a Colombian-American GI. She swore up and down she was in love with him until she had to go back home and she realized it was more lust than love

The sheer amount and the content of racy letters Pepa and Félix sent one another when she was overseas, both when she was an older teen and as an adult would have made a whorehouse blush

Pepa and Julieta shared a little apartment in Germany during WW2. One night, three years after Bruno’s disappearance, they got a frantic phone call from a man named ‘Jernando’ who knew way too much about them and their family for it to be a prank, telling them to get out of the apartment and get out !NOW! because the Germans had been getting intel reports that two women who seemed to be supernatural lived there and they were coming for them. Not even an hour after they left, the girls watched, safely from a roof across the street, their apartment being raided by German soldiers

#encanto#encanto headcanons#Encanto thoughts#madrigal triplets#julieta madrigal#pepa madrigal#bruno madrigal#history#ww1 history#ww2 history

109 notes

·

View notes

Photo

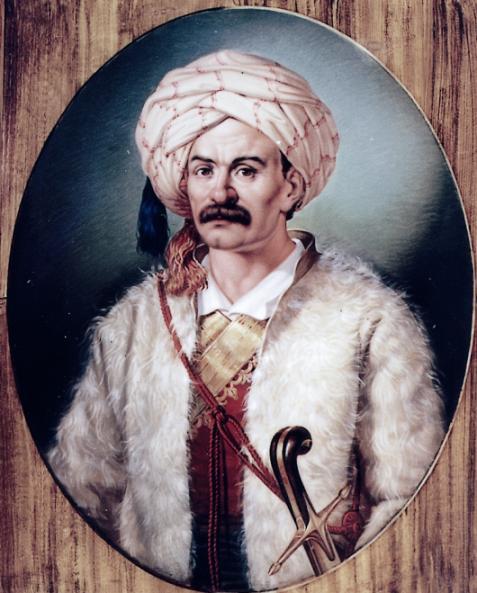

Time for a post about my favorite improbable romance of the Napoleonic era!

Maria de las Nieves Dominique Antoinette Rita Josèphe Louise Catherine Martinez de Hervas was barely fourteen when she married Géraud Christophe Michel Duroc in 1802. The daughter of a Spanish banker and diplomat, she had been educated at Madame Campan’s school along with Hortense de Beauharnais, Caroline Bonaparte, and several other young women who would go on to marry marshals or generals.

While not the outright disaster that some of the other marriages that Napoleon arranged were, the couple’s relationship seems to have been distant. Duroc stayed in Paris, busy with his duties as Grand Marshal, while Hervas spent much of her time at the château de Clémery, outside Duroc’s hometown of Pont-à-Mousson in Lorraine, accompanied by her sister-in-law Jeanne Magdeleine Duroc. It was there that she met Charles Nicolas Fabvier in 1805.

Also a native of Pont-à-Mousson, Fabvier was a decade younger than Duroc; after studying at the École polytechnique, he had joined the Grande Armée as an artillery officer in 1804. What Hervas initially thought of Fabvier, we don’t know; he became a family friend, though that may have been Duroc taking an interest in a fellow officer from Pont-à-Mousson. Fabvier, however, fell hopelessly in love with Hervas.

Writing to his brother Nicolas in 1808 from Constantinople, where he had accompanied a diplomatic mission, Fabvier reflected on the intensity of his feelings: “I’m afraid it’s a disease. In the midst of my labors, while crossing the desert, on horseback, I always find her in the same place, face to face with me...”

In another letter to his brother, he continued: “I have such a veneration, such a high opinion of her that I don’t dare speak of it without permission. If you could only see, if she knew that throughout three years’ absence I thought of her every instant!...But what’s the use? She is a princess now; would she still recognize an unhappy knight, even by name? In short, that woman never leaves my thoughts, let alone my heart. May God bless her and bring her happiness.”

After returning from Constantinople, Fabvier became Marmont’s aide de camp in 1811, and fought in the Peninsular War. He rode the entire length of Europe in the summer of 1812 to bring Napoleon news of Marmont’s defeat at Salamanca, arriving on the eve of the battle of Borodino.

His long absences from France did nothing to dull his feelings for Hervas. After visiting her in Paris in the spring of 1813, he wrote to his brother, who must have had the patience of a saint: “Her presence illuminates, her approach warms; she passes by and one is content; she pauses and one is happy; to regard her is to live; she is dawn in human form; she does nothing else but be there, that suffices, she Edenizes the house, she exudes a paradise.”

As Marmont’s aide-de-camp, Fabvier took part in the campaign of 1813 in central Europe, which meant that he was present for Duroc’s death that May. Having visited the dying man once to say goodbye—”He recognized me,” he told Nicolas, “[and] bade me farewell with kindness and calm”—he returned again later that night, spending hours at Duroc’s side. He wrote to his brother a few days later: “I can’t describe to you all the grievous pains that overwhelmed me while, sitting on a bench and without him seeing me, I watched the man who had been so happy until now…I wanted to speak to him, to help him to move. I never dared.” In his journal, he was more frank about the conflicting feelings produced by seeing his beloved Hervas’s husband mortally wounded: “I fended off, or rather I avoided having, those [thoughts] that I should not have had. I owe myself this fairness. But Nives [sic], if you weep for him, why did I not die for him!”

Later, he added: “Strange fortune! Do you show me the possibility to make me feel my unhappiness all the more keenly? Her rank. Her family. The Emperor. Such obstacles that I'll never overcome…” He worried about the effect the news would have on Hervas, who had already suffered the death of her fifteen-month-old son in 1812. He told Nicolas not to mention him to her in case that would remind her of Duroc—”unless you’re asked whether I wish I could have taken the unlucky bullet; reply: yes”.

After Napoleon’s downfall, Fabvier spent much of the early 1820s getting arrested on suspicion of being involved in Bonapartist plots to overthrow the government. In 1823, after being acquitted for a second time due to lack of evidence, he left France for Greece, where he became a hero in the War of Independence. Hervas remained at Clémery, raising her young daughter Hortense, and was eventually granted a pension by Charles X. When Fabvier returned to France in the late 1820s, he found Hervas still greatly affected by the losses she had suffered, and wrote to his brother (as always) that he “trembled lest fortune send that unfortunate woman yet another horrible blow”.

His words proved prophetic: Hortense Duroc died of pneumonia in September 1829, aged just seventeen. Hervas was so overwhelmed by Hortense’s death that doctors feared for her life; ordered to travel abroad for her health, she went to Italy, accompanied by Fabvier. They visited Hortense de Beauharnais, who was living in Switzerland, and returned to France shortly before the July Revolution.

Twenty-six years after they’d first met, Hervas and Fabvier were married in Paris on May 16, 1831. Their son, Louis Charles Eugène, was born in December of that year.

Fabvier had his happy ending at last; it’s less clear what Hervas felt. Passages from Fabvier’s letters and journal survive in a pair of early twentieth-century biographies, but none of Hervas’s writing, letters or otherwise, is publicly available. Perhaps she shared Fabvier’s feelings; perhaps, after the devastating death of her daughter, she simply wanted stability. Regardless of how she felt about Fabvier, Hervas seems to have considered Hortense’s death, as well as the death of her first son, the defining events of her life. When she died in December 1871, having outlived her second husband by sixteen years, she left money for a funeral monument with the inscription “To the unhappiest of mothers”.

Images: “La baronne Fabvier,” in W. Sérieyx, Un géant de l’action: le général Fabvier (1933), which gives no information about the artist or date. “Charles Fabvier (1782-1855)”, artist unknown, The War Museum, Athens, Greece.

#this post is a mess but fabvier's letters are just So Much that i wanted to share them#maria de las nieves martinez de hervas#charles nicolas fabvier#duroc#napoleonic wars

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Knives of ill repute #2: Navaja

[Part of the series Knives of Ill Repute.]

Albacete, Spain, 19th century

With the Spanish navaja begins the legend of that most “treacherous and ignoble” weapon of the criminal underworld... the folding knife. Now folding knives have been around since antiquity, but they didn't get a bad rap until the 18th century, when the navaja got first singled out. After that, almost all knives of ill repute are folders, utility knives that were repurposed (and only very rarely redesigned) for offensive use, or just carried around for swagger™. The latter is much more common than the former.

The navaja is a characteristic example of how that came to be. When it's generally acceptable to walk around carrying knives and daggers, there's simply no need to resort to a flimsy pocket knife if you suddenly have to cut a man. Even when peasants and labourers weren't allowed to bear arms, they were allowed to carry knives and pointy farming implements, and generally did. When that's disallowed or inconvenient, the ubiquitous pocket knife becomes the only improvised edged weapon you can keep handy. Second, early folding knives didn't come with a locking mechanism, which made them extremely unsuitable for stabbing purposes. Not that a folding knife with a reliable lock can ever be an optimal method of stabbing – they're simply not made for that, they're tools! But without one, it didn't even cross people's minds to use them that way... until the modern period.

Albacete, Spain, 19th century: note the external backspring and ratchet (carraca)

So navaja in Spanish simply means "folding knife", including straight razors. It was a very common tool, and basically everyone had one. But in the 18th century a lot of things are happening at once: Some navajas are manufactured with a backspring, a locking mechanism which makes them passable stabbing instruments. The right to bear arms is still reserved for the nobility, a large chunk of which (if we count the hidalgos) cannot necessarily afford arms. The Bourbons attempt to unify a fragmented system of government under an absolutist Castilian rule, pleasing exactly no one in the process. There's war, war, and more war. What there isn't, is law and order, especially in Catalonia which got the short end of the stick. So in 1750, its military governor bans all edged weapons including poniards, daggers, bullfighting lances, big knives, small knives (with the exception of kitchen knives and pocket knives) and, very specifically, navajas de muelles – the ones with a backspring.

It's the first time that a folding knife gets treated as a dangerous weapon, and it won't be the last. Now the mythology of the navaja truly begins. Over time the knives become bigger, designs become fancier, blades get cocky inscriptions (“Valour!”, “I am from Seville!”, “Don't open me without a reason and don't close me without honour!”), handles borrow materials and decoration patterns from the more reputable arms manufacturers of Toledo and Albacete. For maximum swagger and no stealth whatsoever, some of them also have a ratchet, a cog that locks the blade in the open and closed positions, and maybe a few in between. It unlocks with a pull-ring (from c. 1850) or later a lever, and makes a hell of racket, hence its name: carraca.

Francisco Goya, Por una navaja

After Napoleon invaded Spain in 1808, navajas were banned again, this time by the French authorities. And because this was the War of Spanish Independence, which involved a lot of pissed off insurgent peasants, we should clarify that they didn't just ban the fancy, redesigned-as-weapons navajas, they banned all of them, the simple peasant tool that everyone had (and only sometimes used to cut soldiers' throats). That's the context for Francisco Goya's iconic The Disasters of War drawings, and the one titled “Por una navaja”, where the poor village priest gets executed by garrote for the crime of having a lousy clasp knife.

Antonio María Esquivel y Suárez de Urbina, Riña de bandoleros (1830)

In the 19th century, navajas get heavily associated with the criminal underworld, urban and rural, although they remain a common tool that everyone carries. The local press and gentry treat them as the exotic weapons of the exotic lower classes. Foreign travellers, mostly French and British, are just fascinated with those red-blooded Spaniards and their fancy blades. Travel literature, mixed to an extent with rogue literature (oh those dangerous but sexy bandoleros, barateros, and pícaros), and the Romantic writings of Prosper Mérimée (Carmen, Letters from Spain) and Théophile Gautier (Wanderings in Spain) build the myth some more. Even in the 20th century, poets like Federico García Lorca are not immune to the navaja's allure.

[Part of the series Knives of Ill Repute.]

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

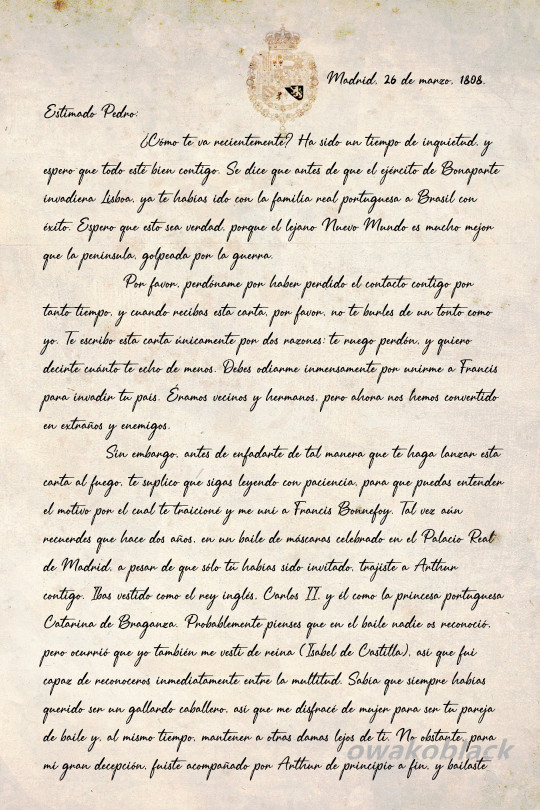

(PortSpa Fanfiction) Letters Written in 1808

Disclaimer: This is Hetalia fan fiction. I do not own anything.

Pairing: Portugal/Spain

For convenience, I use human names for nations in this fiction. Portugal is Pedro, Spain is Antonio, Arthur is England, Francis is France, and Miguel is Brazil.

The story background is at the beginning of the Peninsular War (1807–1814). These letters are between Antonio, Pedro, and Arthur.

Special thanks to (in alphabetical order):

Portuguese beta reader: Alice

Portuguese and Spanish translator: BA

Spanish beta reader: soyuncalimero

English beta reader: shark

Madrid, 26 de marzo, 1808.

Estimado Pedro:

¿Cómo te va recientemente? Ha sido un tiempo de inquietud, y espero que todo esté bien contigo. Se dice que antes de que el ejército de Bonaparte invadiera Lisboa, ya te habías ido con la familia real portuguesa a Brasil con éxito. Espero que esto sea verdad, porque el lejano Nuevo Mundo es mucho mejor que la península, golpeada por la guerra.

Por favor, perdóname por haber perdido el contacto contigo por tanto tiempo, y cuando recibas esta carta, por favor, no te burles de un tonto como yo. Te escribo esta carta únicamente por dos razones: te ruego perdón, y quiero decirte cuánto te echo de menos. Debes odiarme inmensamente por unirme a Francis para invadir tu país. Éramos vecinos y hermanos, pero ahora nos hemos convertido en extraños y enemigos.

Sin embargo, antes de enfadarte de tal manera que te haga lanzar esta carta al fuego, te suplico que sigas leyendo con paciencia, para que puedas entender el motivo por el cual te traicioné y me uní a Francis Bonnefoy. Tal vez aún recuerdes que hace dos años, en un baile de máscaras celebrado en el Palacio Real de Madrid, a pesar de que sólo tú habías sido invitado, trajiste a Arthur contigo. Ibas vestido como el rey inglés, Carlos II, y él como la princesa portuguesa Catarina de Braganza. Probablemente pienses que en el baile nadie os reconoció, pero ocurrió que yo también me vestí de reina (Isabel de Castilla), así que fui capaz de reconoceros inmediatamente entre la multitud. Sabía que siempre habías querido ser un gallardo caballero, así que me disfracé de mujer para ser tu pareja de baile y, al mismo tiempo, mantener a otras damas lejos de ti. No obstante, para mi gran decepción, fuiste acompañado por Arthur de principio a fin, y bailaste exclusivamente con él, ignorándome por completo. Al ver a mi viejo enemigo pretendiendo ser una chica del mismo modo que yo, con la diferencia de que él era capaz de acercarse a ti mientras yo no podía, me sentí mucho menos que tu "amigo para siempre" del otro lado del mar, aunque siempre había sido tu hermano vecino desde nacimiento.

Esa noche, mi corazón se llenó de celos y frustración, lo que me hizo perder la cabeza. Corrí hacia un jardín, donde me encontré con Francis. Me consoló, criticando la ciega Diosa del Destino que suele elegir los amantes equivocados para las personas, porque tú y yo habíamos sido hechos el uno para el otro. Agregó que como este amante erróneo era su enemigo, él debía ayudarme a alejarte de Arthur. Por un tiempo, Francis fue ciertamente muy amable y fiel a mí. Además de ti, nunca he conocido a nadie que me entendiera tan bien y se preocupara de mi con todo su corazón. Finalmente, atraído por sus dulces palabras, acepté unirme a él.

¡Ay, qué tonto fui! Lloré mi corazón delante de él, porque no podía ganarme tu corazón. Fue la primera vez que mostré mi debilidad a alguien aparte de ti. Aun así, por esta inesperada excepción, acabé aprisionado en la trampa tendida por Francis. Hace dos días, el ejército francés asaltó Madrid; nuestro rey se vio obligado a abdicar, y creo que el hermano de Napoleón pronto llevará la corona española en su lugar. No es hasta ahora que al fin me doy cuenta de que, aunque Francis me había prometido su asistencia en ganar tu cuerpo y alma, lo único que deseba en realidad era la totalidad de la Península Ibérica — quiere una administración unificada del continente, para poder derrotar la nación al otro lado del Canal. Usando España como trampolín, Francia puede obtener Portugal sin mayor obstáculo. Era demasiado tarde para darme cuenta de que Francis no fue realmente amable conmigo, porque sólo tiene a Arthur en mente.

Espero que estés en Brasil ahora. No te culparé aunque el pequeño Miguel esté ahora mismo en tus brazos, porque la situación en toda la Península es realmente terrible: las plagas y los desastres naturales están por todas partes; las personas no tienen alimentos que comer ni ropas que llevar; uno de los ejércitos era tan pobre que ni siquiera podía permitirse el suministro militar más básico, como un conjunto completo de uniformes. ¡A penas puedo imaginar lo difícil que debe ser tu vida si es que sigues en Lisboa! Lo más probable es que actúes como yo: a pesar de que sólo quede un pedazo de pan en casa, cuando veas niños hambrientos pasando por debajo de tu ventana, se lo darás sin dudarlo.

Como naciones, no tenemos más remedio que estar siempre al lado de nuestro pueblo, porque la voluntad de la gente es nuestra propia voluntad. El pueblo español consideró al ejército francés como invasor cuando Murat asaltó Madrid, y creo que pronto las revueltas contra los franceses se extenderán por todo el país. Voy a unirme a mi gente para luchar contra Francis. En lo profundo de mi corazón, sé que me encuentro en un estado miserable para combatir, pero he decidido pelear con mi gente hasta el último suspiro. No te preocupes por mí, Pedro — soy una nación, no caeré fácilmente.

Si realmente has leído mi carta hasta el final, entonces gracias a Dios, espero que ahora hayas entendido las verdaderas razones por las que te he traicionado e invadido Portugal. Sinceramente ruego por tu perdón, si no, me mataré por las tonterías que he hecho. Sabes, la causa de todos estos eventos es porque te quiero tantísimo que no quiero que nadie te aleje de mí. ¿Estás sorprendido por mi repentina confesión? Después de todo, desde el final de la Unión Ibérica, nunca te he llamado mi "hermano", y nunca me has reconocido como tu "irmão". Sin embargo, siempre he sido capaz de sentir el vínculo entre tú y yo que hace que mi vida no pueda prescindir de ti, y en un momento tan vital, me hace extrañarte incluso más.

Mi querido hermano, por favor perdóname.

Cordiales saludos,

Antonio.

P.S. Por favor, envía mis saludos a Miguel y hazle saber que le ruego que te mantenga en Brasil. Puedo manejar la situación en la Península solo.

Lisboa, 3 de Abril de 1808

Caro António,

Acabei de ler a sua carta. Na verdade, eu estive sempre em Lisboa nestes últimos dias. Felizmente, o carteiro é um conhecido meu, caso contrário a sua carta teria circunavegado o mundo antes de me ter alcançado.

É verdade que já não nos contactamos há muito tempo. Não é de admirar que você não saiba muita coisa sobre o meu paradeiro e que eu pouco saiba da sua situação atual. Fiquei surpreendido quando me contou na sua carta o quão miserável está mas já que teve algum tempo para me escrever e mostrar que tem saudades minhas e que sente a minha falta, não acho estará assim tão mal. Tem de aguentar. Encontrarei uma solução.

Infelizmente, não me deu outra alternativa a não ser ter de o perdoar. Nem toda a gente tem a pouca sorte de ter um irmão mais novo tão parvo como você.

Sinceros cumprimentos,

Pedro

Lisbon, April 3rd, 1808.

Dear Arthur,

How are you? Is the weather in England getting better? Spring has arrived earlier than Easter in Lisbon, but I have no mood, or rather, no place for flower appreciation. Last time when you visited me, you told me that you liked the golden daffodils in my backyard, for they reminded you of William Wordsworth’s poem. However, I was unable to keep them for you. This year, shortly before the flowers could come out, I gave the daffodils including their roots to hungry street urchins. Please forgive my messy handwriting, for I cannot resist my hand from shaking when I am writing this letter. I cannot continue describing the terrible situation in Lisbon after it has been occupied by Napoleon’s army. What makes me even more worried is the worse situation in Spain.

Just now, I received a letter from Antonio. Although Antonio and I are brothers and neighbours, out of a misunderstanding, we had lost contact for a long time. Yet now he has got off his high horse to write to me for my forgiveness, which means that the threat is hanging over his head. In his letter, he frankly admitted his faults: he desired me so much that he was caught into cunning Francis’ trap. He finally realized that Francis’ true purpose is not to help him to gain me, but to occupy the whole Iberian Peninsula. Once the whole Continent is under the control of France, Francis will obtain enough power to defeat you. As for the final purpose of Francis, I have never doubted, for, as far as I know, he has been always against you.

And now my little Brother is badly hurt. Last week, Madrid was invaded by the French army, the King was forced to abdicate, and Spain is enslaved by France. Antonio told me that Spain had already been tortured by plagues and natural disasters for many years, economy was severely damaged, people are without food and clothes, and yet what little is left is pillaged by the French army. My Brother stands with his people, trying desperately to fight against their enemy. Nonetheless, they cannot even afford a set of military uniform, let alone guns and cannons.

Arthur, my dear Friend, you have brothers too. Even though frictions could hardly be avoided among family members who live together under the same roof, family members are family members after all. If we do not love our family, we are incapable of loving others too. Antonio and I are not merely brothers, but also twins. Believe it or not, we have telepathy since birth. No matter how far away, I can somehow sense both his pleasure and pain. When we were small children, one day Antonio broke his leg, and I was able to feel his pain from miles away, which made me unable to walk for a whole month. Now my writing hand is shaking again--Antonio must have been injured in the battle of Madrid against the French. He did not tell me about his injury less I might get worried, but he can never conceal anything from me. I have only Antonio as my twin Brother--I am Antonio, he is always in my mind--if I lose him, I will lose my own being.

Even if you do not sympathize with my Brother for the sake of our ‘forever alliance,’ please think about yourself: if the power of France continues to spread all over Europe, it would be too late to sustain him. Since the beginning of this year, the Spaniards all over the country have shown their courage and competence in the fierce battles against French invaders, many of them having witnessed the return of the brave Antonio during the Age of Discovery. Being the brother who understands him best, I believe Antonio will defeat Francis, and turn all the French invaders away from the Peninsula. Such future will surely be realized. What he is in need is just a little help from a foreign friend in the aspects of human resource and finance, for even King Arthur cannot win a battle without the aid of his Knights of the Table Round, and Spain needs help to face such a strong enemy.

Dear Arthur, I know that my little Brother had offended you before, it was all due to his childishness and thoughtlessness. Please, for my own sake, forgive and help my poor little Brother. All he needs is just a little help, and I promise you that he will win the war against France. My dear old Friend, you are the only one that I can rely upon, otherwise I can find no solution for helping him.

I can only send some small gifts to you in a hurry. I will pay your kindness wholeheartedly in the near future.

Looking forward to your reply.

Yours sincerely,

Pedro

London, April 10th, 1808.

My dear Pedro,

Thank you very much for your letter and your gifts. I appreciate Portuguese wine--they are always with high quality. And the painting, titled ‘Allegory to the allegiance between Portugal, England and Spain,’ is stunningly beautiful. Aren’t there three of us in this picture?

The English weather is still bad, not suitable for a stroll on the seaside at all. In London, it was sunny in the early morning, but when I went out, it suddenly hailed, making passers-by scurry into shops--this was quite ridiculous. The English enjoy talking weathers, for the English weather is too bad, and therefore we all long for warm and sunny places. For me, Portugal is the heaven on earth. During the long, cold winter, every time when I think of the soft golden sand in Lagos, my heart will be filled with comfort and pleasure. What makes me miss Portugal even more is the delicious food you usually make for me: I could sail for Portugal anytime only for food.

However, after reading your letter, I suddenly realized that everything is past. I can hardly imagine that my chef and old Friend has nothing to eat, and his beautiful homeland is destroyed by war. It saddens me deeply.

You asked me to help your Brother, which I accept, but I have a condition: you must let me help you first. For I know, your situation is no better than your Brother’s. Your King abandoned you to escape to Brazil, which means the Portuguese administration is shifted from Lisbon to Rio de Janeiro, and you become Miguel’s colony. You asked me to save Antonio instead of worrying yourself--I totally understand how much you love him, even though you always deny it. However, this time, I really worry about you--please let me help liberate Portugal from that villain.

In addition, if England wants to fight battles on the Continent, the English army must have a standing point first. Please allow our army to land on Portugal so that we can proceed to a larger battle.

I am going to discuss the plan further with Duke Wellington. I will write to you later.

Yours faithfully,

Arthur

#hetalia#hetalia portugal#hetalia spain#hetalia england#PortSpa#iberian brothers#aph iberia#APH England#aph portugal#aph spain#hws portugal#hws spain

31 notes

·

View notes