#Middle Ages

Text

Mitre made for Bishop Conor O'Dea of Limerick, Ireland in 1418

from The Hunt Museum

156 notes

·

View notes

Text

Victorian Mourning Jewelry

Often containing hair, teeth, and other physical remains of the dead, these pieces peaked in popularity in the Victorian era. Mourning jewelry is one of earliest sartorial expressions of the gothic romanticism which has defined many famed modern designers, from Alexander McQueen to Ann Demeulemeester to Lieve Van Gorp. The genre is made up of broaches, necklaces, rings, and other adornments meant to celebrate loved ones who had passed away. However, the pieces from that period rather simply served to underscore the concept of "memento mori" ("remember you will die")

#victorian#victorian era#middle ages#weirdcore#goth#gothic#aesthetic#dark#darkcore#fashion#jewelry#antique#vintage#1800s#art#gold#hair#alexander mcqueen#queen victoria#princess alice#death#life and death#deathcore#skeletons#eyes#creepy#beauty#dark beauty#dark aesthetic#gothic aesthetic

132 notes

·

View notes

Text

Margaret of Anjou Taken Prisoner after the Battle of Tewkesbury by John Gilbert

#battle of tewkesbury#wars of the roses#margaret of anjou#art#john gilbert#england#medieval#middle ages#tewkesbury abbey#house of york#house of lancaster#english#history#gloucestershire#europe#european#mediaeval#knights#knight#soldiers#palfrey#horses#sky#landscape#clouds#edward iv#edward of westminster#sir john gilbert

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

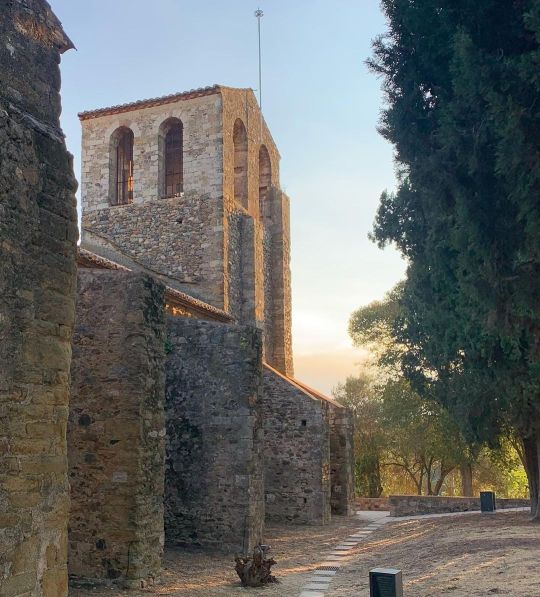

Sant Miquel de Cruïlles monastery and village around it. Comarques Gironines, Catalonia.

This monastery was built around the year 1035, and was abandoned after 1835 with the government confiscations of church possessions. As a result, some parts of the monastery have been completely lost, such as the cloister. The little village that grew around the monastery is still inhabited.

Photos by medievalismes (Instagram, TikTok).

#sant miquel de cruïlles#cruïlles monells i sant sadurní de l'heura#catalunya#fotografia#travel#medieval#middle ages#village#monastery#romanesque#europe#rural#catalonia#wanderlust#travel photography#historical#curators on tumblr

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

A new discovery in Kazakhstan uncovers 4,000-year-old petroglyphs in the Karatau Mountains, revealing the rich cultural history of Bronze Age peoples. The rock carvings offer a pictural commentary through epochs, with the most recent being added in the Middle Ages.

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mélusine.

#art#my art#artwork#concept art#artists on tumblr#illustration#draw#drawing#paint#painting#watercolor#watercolour#gouache#markers#mixed media#landscape#surreal#fantasy ambient#ambient#myth#french myth#legend#dark#snake#middle ages#mermay#colorful

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

A murder mystery film set in a medieval village. After an outbreak of plague, the villagers make the decision to shut their borders so as to protect the disease from spreading (see the real life case of the village of Eyam). As the disease decimates the population, however, some bodies start showing up that very obviously were not killed by plague.

Since nobody has been in or out since the outbreak began, the killer has to be somebody in the local community.

The village constable (who is essentially just Some Guy, because being a medieval constable was a bit like getting jury duty, if jury duty gave you the power to arrest people) struggles to investigate the crime without exposing himself to the disease, and to maintain order as the plague-stricken villagers begin to turn on each other.

The killer strikes repeatedly, seemingly taking advantage of the empty streets and forced isolation to strike without witnesses. As with any other murder mystery, the audience is given exactly the same information to solve the crime as the detective.

Except, that is, whenever another character is killed, at which point we cut to the present day where said character's remains are being carefully examined by a team of modern archaeologists and historians who are also trying to figure out why so many of the people in this plague-pit died from blunt force trauma.

The archaeologists and historians, btw, are real experts who haven't been allowed to read the script. The filmmakers just give them a model of the victim's remains, along with some artefacts, and they have to treat it like a real case and give their real opinion on how they think this person died.

We then cut back to the past, where the constable is trying to do the same thing. Unlike the archaeologists, he doesn't have the advantage of modern tech and medical knowledge to examine the body, but he does have a more complete crime scene (since certain clues obviously wouldn't survive to be dug up in the modern day) and personal knowledge from having probably known the victim.

The audience then gets a more complete picture than either group, and an insight into both the strengths and limits of modern archaeology, explaining what we can and can't learn from studying a person's remains.

At the end of the film, after the killer is revealed and the main plot is resolved, we then get to see the archaeologists get shown the actual scenes where their 'victims' were killed, so they can see how well their conclusions match up with what 'really' happened.

#film ideas#plotbunny#murder mystery#detective stories#period dramas#middle ages#history#archaeology

20K notes

·

View notes

Text

“Every Italian noble in the medieval commune era” - ENGLISH SUBTITLES

20K notes

·

View notes

Text

17K notes

·

View notes

Text

Medieval Scooby

71K notes

·

View notes

Text

25K notes

·

View notes

Text

L'amant et l'Amour

13K notes

·

View notes

Text

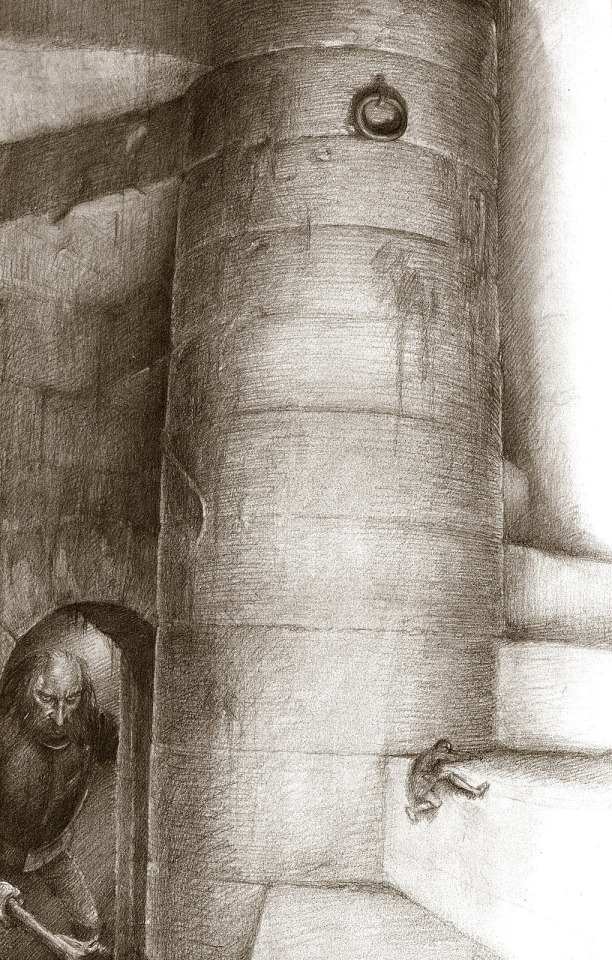

Castles - art by Alan Lee (1984)

#alan lee#castles#80s fantasy art#arthurian legends#fairy tales#gormenghast#medieval art#knights#middle ages#fantasy books#david day#1980s#1984

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

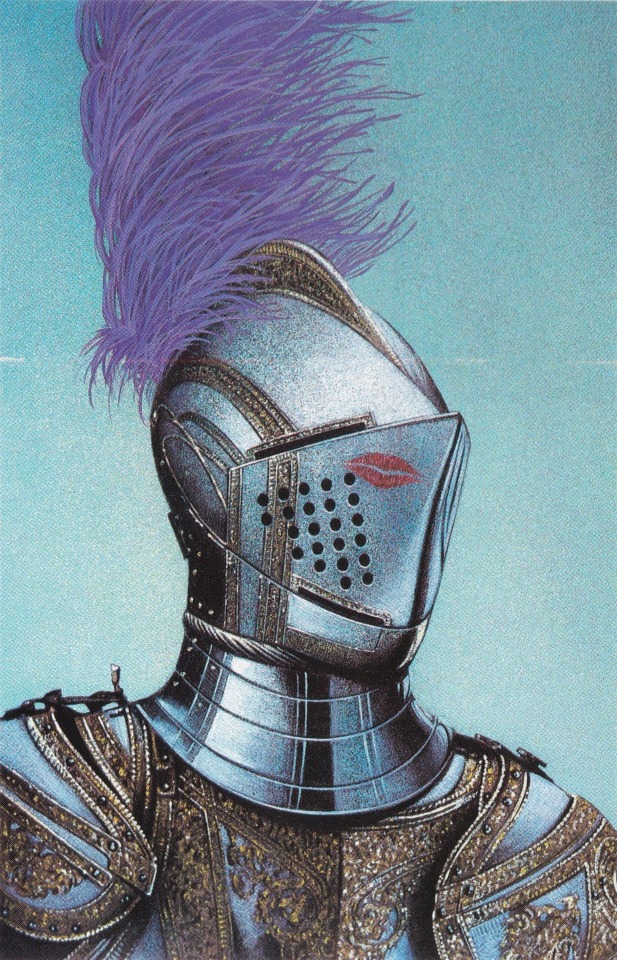

#knight#knights#art#illustration#david michael beck#david m beck#1984#helmet#armour#medieval#middle ages#kiss#lipstick#kisses#plumes#plume#chivalry#helmets#feather#feathers#history#europe#european#cavalier#chevalier#mediaeval

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Hellelil and Hildebrand (The Meeting on the Turret Stairs), Frederic William Burton, 1864

#art#art history#Frederic William Burton#historical painting#Middle Ages#medievalism#Irish art#19th century art#Victorian period#Victorian art#watercolor#gouache#watercolor on paper#National Gallery of Ireland

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Carved walrus ivory comb with scenes from the life of King David and Bathsheba, France, 15th century

from The Hunt Museum, Limerick

2K notes

·

View notes