#Koker trilogy

Text

On the Life and Work of Acclaimed Iranian Filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami

Speaking to critic and scholar Godfrey Cheshire ahead of the Belcourt’s Abbas Kiarostami: A Retrospective

CRAIG D. LINDSEY

OCT 10, 2019

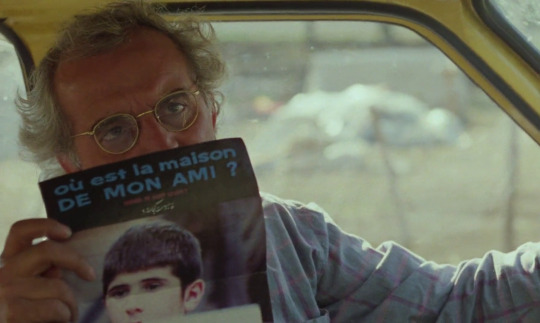

Where Is the Friend’s Home?

On Oct. 11, the Belcourt will host a two-week retrospective dedicated to the features and shorts of late Iranian filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami. This traveling tribute will feature 2K and 4K restorations of Kiarostami’s most poignant, most enigmatic, most essential work, including his acclaimed Koker Trilogy (Where Is the Friend’s Home?, And Life Goes On and Through the Olive Trees) and Taste of Cherry, the latter of which was awarded the Palme d’Or at the 1997 Cannes Film Festival.

And who better to talk with about Kiarostami than Godfrey Cheshire, the film critic/writer/filmmaker who knew him best? Quite possibly the foremost stateside authority on Iranian cinema, Cheshire (who has written for The New York Times, New York Press, Film Comment and RogerEbert.com) had a bond with the filmmaker that began back in the ’90s. The interviews they did over the years have now been collected in a new book, Conversations With Kiarostami. (He has another book, In the Time of Kiarostami: Writings on Iranian Cinema, scheduled for release next year.) Cheshire also served as a consultant on the retrospective, which — before coming to Nashville — showed in Los Angeles, New York City and elsewhere. He answered our questions via email.

OK, this retrospective. How did it come about, and how did you get roped into it?

In 2017, following Kiarostami’s death the previous year, the French company mk2 acquired the rights to almost all of his films and embarked on a two-year restoration project in collaboration with the U.S. company Janus Films/Criterion Collection. Ahmad Kiarostami, the director’s son, told Janus/Criterion that they should work with me because I’m virtually the only person in the U.S. who knows about the many films in the first third of Kiarostami’s career. That’s partly due to the interviews I did with him that are in my book. I have worked with Criterion on the DVD releases of Close-Up, Taste of Cherry, Certified Copy and the new Koker Trilogy box set.

Taste of Cherry

While I was reading your book, I was taken aback by how serious he was as an artist — but it seemed he could take or leave filmmaking. He said he wasn’t a big cinephile. There’s that story where he won the Palme d’Or at Cannes for Taste of Cherry and said he felt “nothing.” Considering his love for poetry and photography, what can you say is the thing that drove him to be a filmmaker?

I think filmmaking was his primary focus because it combined all of the qualities of the other arts and interests he had. It was visual and auditory, but also could be poetic, psychological, dramatic, philosophical and so on.

Kiarostami said there are Iranian filmmakers far more successful than he. In your opinion, what is it about Kiarostami that makes him such an emblematic figure in Iranian cinema?

When I first visited Iran in the late ’90s, I learned that many Iranians didn’t consider him their greatest director. I think he gradually became recognized as such when critics and audiences in other parts of the world embraced the films of his middle period, due to their very subtle and psychologically astute stories and distinctively poetic film language.

In the book, you break down his career into three periods: his work with the Institute for Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults (better known as Kanoon), his Koker Trilogy/Masterworks period, and his experimental later-years period. What are the essentials from each period?

In the first period, you see an artist who has a very strong sense of a poetic kind of cinema (evident in his first four films, the shorts “The Bread and Alley” and “Breaktime,” the short feature The Experience and the feature The Traveler) and one who is also experimenting in various ways while mainly making films about children and teenagers. In the second period, he demonstrates a kind of mastery that has emerged from his earlier work while making films, mostly about adults, that continued to make artistic leaps. In the third period, it’s like he ceased to care about making masterpieces and returned to the more personal, low-key and experimental aspects of his first period. The experimentation here included making films in other countries and languages, Certified Copy (Italy) and Like Someone in Love (Japan).

And Life Goes On

As you continued to explore Iranian cinema and continued your relationship with Kiarostami, did it start to become a kindred-spirit thing where both of you had the same mission — to show the most ambitious cinema Iran has to offer?

I think our friendship, which began in 1994 and continued until his death, was a kind of kindred-spirits relationship. It had to do with the fact that he realized that I’d studied his films in detail, but it also was just personal — I liked him and he liked me. I would say that I had (and have) a mission to tell people about the genius of Iranian cinema and culture, while his only mission was to continue doing work that he considered challenging and meaningful.

What would you like people to take with them after attending this retrospective?

Recently in New Orleans, I spoke with a renowned art curator who said: “In the art world, Warhol was the last giant. In cinema, Kiarostami is the last giant.” I think you can certainly say that he was the last cinematic titan of the 20th century, the century of cinema. At the beginning of the 1990s, probably no American critic had ever heard of him; at the end of the ’90s, American critics polled by Film Comment voted him the decade’s most important filmmaker. I think people attending the retrospective will see the evidence of a multifaceted artist whose distinctively poetic way of filmmaking places him in the company of such figures as Chaplin, Welles, Rossellini, Bergman and Kurosawa.

#Iran#Cinema#Godfrey Cheshire#Abbas Kiarostami#CRAIG D. LINDSEY#Where Is the Friend’s Home?#Janus Films#Koker Trilogy#And Life Goes On#Through the Olive Trees#Taste of Cherry#Criterion Collection#Ahmad Kiarostami#Palme d’Or#The Bread and Alley#Breaktime#The Experience#The Traveler#Certified Copy#Like Someone in Love#Chaplin#Welles#Rossellini#Bergman#Kurosawa.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

'In his 1987 Nobel lecture, Joseph Brodsky said, anthropologically speaking, a human being is primarily a creature of aesthetics, and only after, an ethical one.

This assertion sounds true in the case of J. Robert Oppenheimer. The scientific leaps in the field of quantum physics fascinated Oppenheimer. He was driven to follow the path of Niels Bohr and Werner Heisenberg. Returning from Cambridge to expand his research in Berkeley, he fell into the arms of the American state and became part of the Manhattan Project to develop an atomic bomb.

It is comic irony that Lewis Strauss, who secretly plotted against Oppenheimer, was forced to work as a shoe salesman during the recession, while Oppenheimer achieved the distinction of Edward Teller calling him, “the great salesman of science.” This explains the moral turn in the life of Oppenheimer. Christopher Nolan likened his character to the titan Prometheus, though midway he seemed to metamorphose into Frankenstein. The hamartia of Oppenheimer’s life, Aristotle’s term for the Greek tragic hero’s fatal flaw, turned into a modern horror story.

The poet Joseph Brodsky’s distinction becomes relevant at this point: Oppenheimer abandoned the moral for the aesthetic. My scholar friend (who wishes to remain unnamed) shared the opinion that Oppenheimer, initially lost in the beauty of pure theory, transforms that aesthetic obsession into a monstrous one. She added the sharp insight: “Oppenheimer tells himself a lie. That the bomb has a moral end.” The act of lying to oneself produced a psychic wound within Oppenheimer. He lost sight of the moral aspect within his aesthetic pursuit. The lie made the transformation possible. The sublime beauty of studying quantum physics was ruined the moment Oppenheimer decided to use his expertise for a detrimental cause.

The sale of his scientific skills to the American state for making the bomb had a clear political objective for Oppenheimer: to finish off Hitler. This logic led him to overcome the moral dilemma behind his job. Any force that can destroy evil is legitimate. The destructive power of science was a seductive option to nullify the power of fascism. The Jewish Oppenheimer did not have his revenge over the Nazis (who were already defeated when the bomb was ready). The American state used it against a weakened Japan to declare its omnipotence.

Young Oppenheimer’s interest in T.S. Eliot’s ‘The Wasteland’ and the Gita has a deep connection: Eliot’s poem ends by evoking the Upanishad, “Shantih shantih shantih”, a peace of the grave that fell upon a world torn apart by the end of World War I and the flu epidemic. Oppenheimer’s translation of the line from the Gita, “I am become Death, destroyer of worlds” was what Krishna said about his divinity being time itself that destroys the world at will. It was meant to exhort a weak-kneed Arjuna (who did not want to kill his cousins, seniors and kinsmen), reminding him of his duty as a warrior to prepare him for battle. The figure of divine incarnation and warrior-prince got fused into the scientist who invented a weapon that could kill millions.

Oppenheimer’s interest in the evocative moments in the two texts shows a certain death wish he carried within himself. When you are hell-bent to destroy the enemy, you are also out to kill a part of yourself through the act of retributive justice.

Oppenheimer was not able to distinguish between the ethical difference between annihilating a system of power and annihilating people. This failure, however, is an intimate part of the modern West’s history. It produced ideas of the state – fascism, communism and imperial democracies – where the other within and outside one’s ideological fold was demonised as the absolute enemy and was meant to be exterminated. Making the bomb to be used for war, Oppenheimer not just used science as a tool for destruction, but created an ideology of science as divine power that could kill uncountable numbers of people as much as it could heal the world.

It has been acknowledged that Nolan did not glorify war by not showing the bomb being dropped on the two Japanese cities. Still, as my scholar friend pointed out, Nolan could not prevent himself from indulging in Hollywood’s fetish for spectacle. There was a clear lack of self-restraint. The slow-motion explosion of the bomb that filled the screen numbed the audience, and engulfed it into the terror of its silence.

Contrast it with Abbas Kiarostami, who did not display the earthquakes that rocked Iran in Koker Trilogy in order to portray its psycho-social repercussion on the lives of residents who suffered its impact. Kiarostami’s art of filmmaking is deeply informed by his ethical hesitation.

Nolan had more reasons to hold back from depicting the technological grandeur of an instrument of death. The temptation to recreate the spectacle is not simply an aesthetic flaw.

The euphoria of the scientific feat was viscerally exhibited by bodies of people stomping the floor of the hall celebrating Oppenheimer. It announced the coming of a new crowd in world history that took nationalist pride in mass destruction of other people. Oppenheimer looked conflicted, remorseful and eaten by guilt. But there were no indications to suggest he completely regretted his success. Truman, embodying the masculine pragmatism of the American state, lampooned Oppenheimer as “crybaby”. No one cared about the real babies in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Such is the moral indifference of war. It causes deafness of the soul.'

#Abbas Kiarostami#Koker Trilogy#Christopher Nolan#J. Robert Oppenheimer#T.S Eliot#The Waste Land#Bhagavad Gita#Niels Bohr#Lewis Strauss#Werner Heisenberg#The Manhattan Project#Hiroshima#Nagasaki

0 notes

Text

THROUGH THE OLIVE TREES:

In meta drama

Tea man tries to court actress

While acting in scene

youtube

#through the olive trees#random richards#poem#haiku#poetry#haiku poem#poets on tumblr#haiku poetry#haiku form#poetic#criterion collection#abbas kiarostami#Hossein Rezai#Koker trilogy#Youtube

1 note

·

View note

Text

'Where Is the Friend's House?' – Abbas Kiarostami's first childhood odyssey on Criterion Channel

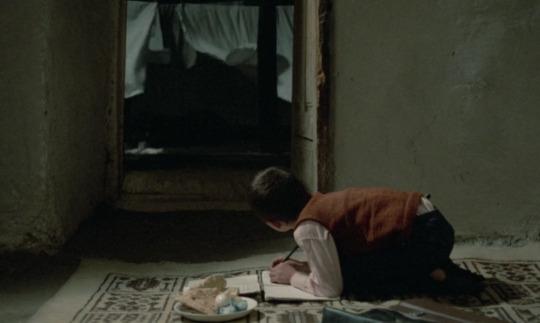

Where Is the Friend’s House? (Iran, 1987), Iranian master Abbas Kiarostami’s first and most conventional dramatic feature, is an odyssey of sorts, a sweet and simple story of childhood in rural Koker.

Ahmed (Babek Ahmed Poor) is a schoolboy who discovers he’s accidentally taken home his buddy’s homework assignment. Against the express orders of his mother he rushes off to a nearby village to…

View On WordPress

#1987#Abbas Kiarostami#Babek Ahmed Poor#Blu-ray#Criterion Channel#DVD#Iran#Koker Trilogy#VOD#Where is the Friend&039;s Home?

0 notes

Note

do you have any movie/book recommendations? your taste is impecable

thank you for flattering me, i'm honored that you think so!!

i really just started watching movies (insofar as this is possible) so my recommendations are limited but i adore july rain, it's free on youtube in high definition. it's fantastically shot, i find it comforting and uplifting in a deeply sincere way. angel's egg is far and way the most stunning animated film i can imagine. mirror is visually and textually so dense it's remarkable. i watched the koker trilogy recently and they were just a joy to watch, really beautiful and so diligently made, at the same time incredibly simple and complex

i put links to the letterboxd pages so i can spare you me trying to describe the plot/synopsis of a film hehe

as far as books go... i really like platonov, i recommend reading one of his short stories (maybe among animals and plants) and if you connect with his writing style, read happy moscow, the foundation pit, or the collection of his short stories (usually published with the novella soul, which is not one of my favorites honestly)

i also love elizabeth bishop's poetry, my entire soul is located within the stanzas of at the fishhouses. i recommend one of her collected works

anyone, please send me any movies or books you've read and appreciated lately, i'm happy for anyone to share their recommendations!!

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

~10 (give or take) blorbos, fandoms, tags

In reverse order from present day to childhood:

Kerr Avon - Blake’s 7

Gerald Tarrant - Coldfire Trilogy by CS Friedman

Aaravos - The Dragon Prince cartoon

Iorveth - The Witcher 2 videogame

Gascon Brossard - Thronebreaker videogame

Don Simon Ysidro - James Asher novels by Barbara Hambly

Lestat - Anne Rice’s vampire novels

Methos - Highlander TV series

Old Shatterhand - Winnetou by Karl May

Zorro - Kaiketsu Zoro anime

Shredder - Ninja Turtles cartoon series

A lot of these are good bad boys, or villains with a heart. Many have some hidden dark past or secret identity. They often look elegant, swift or graceful rather than bulky; their strength tends to lie in their mind more than their body, and insofar as they’re physically strong, it’s in a way that makes them look like a figure skater rather than a wrestler. They’re all brilliant and very competent at what they do. They tend to have a certain wisdom in the way they see the world, delivering unexpected and often sarcastic insights, but with a sweet bitterness that hints at a sensitivity they are trying to hide.

Thanks for the tag @myblacksailstales Tagging with no pressure @theobscurepotato @bertilakslady @first-and-last-neocount @aretuzagradschooldropout @alter-koker @witch-and-her-witcher @vigil-of-the-red-waste @sarasade @zzzett @marnasid @she-who-drank-vodka-with-cats @between-thepages and anyone else who wants to join.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

hoping to watch the koker trilogy by abbas kiarostami next

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

tagged by @suburban--dad to do a ten characters from ten franchises thing!

(very loosely in order of how often i think about them):

Ahmad(/Babak) Ahmadpour, Koker Trilogy

Samwise Gamgee, Lord of the Rings

Omar Little, The Wire

Esker, Outer Wilds

Hess Green, Ganja & Hess

Silvio Dante, The Sopranos

Tomas Ericsson, Winter Light [from the untitled Bergman trilogy]

Zhu Bajie, Journey to the West

Annie, Halloween

Raylan Givens, Justified

i’ll tag anyone i know on here!

#this was Impossible‚ i so rarely do 'franchises'#but a fun experiment nonetheless!!#i'm aware it's a stretch to call outer wilds a franchise however i do not care

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Farhad Kheradmand and Hossein Rezai in Through the Olive Trees (Abbas Kiarostami, 1994)

Cast: Mohamad Ali Keshavarz, Farhad Kheradmand, Zarifeh Shiva, Hossein Rezai, Tahereh Ladanian, Hocine Redai, Zahra Nourouzi, Nosrat Bagheri, Azim Aziz Nia, Ostadvali Babaei, Ahmed Ahmed Poor, Babek Ahmed Poor. Screenplay: Abbas Kiarostami. Cinematography: Hossein Jafarian, Farhad Saba. Production design: Abbas Kiarostami. Film editing: Abbas Kiarostami. Music: Amir Farshid Rahimian, Chema Rosas.

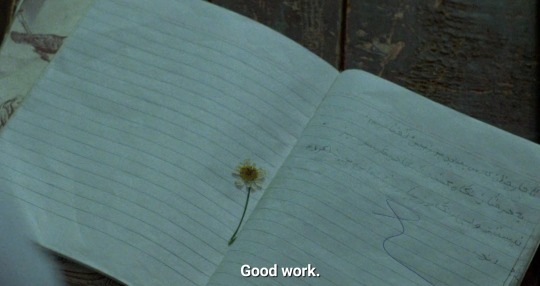

Through the Olive Trees is the concluding film in what has become known as Abbas Kiarostami's "Koker trilogy," which is made up of the neorealistic Where Is My Friend's House? (1987), the semi-documentary And Life Goes On (1992), and this lyrical, pastoral, slyly comic work. It's possible to impose a variety of shapes on the trilogy as it moves from the simple narrative of the first film, made on the eve of the 1990 earthquake that devastated northern Iran, through the anxious quest for survivors of the cast of the first film that constitutes the middle film, and into a kind of post-disaster healing that centers on both the making of a film and one of its actors' nervous, intense courtship of a young woman, also an actor in the film. Through the Olive Trees also answers a question that was raised but never answered in And Life Goes On: Did the two boys who were the focus of Where Is My Friend's House survive the quake? But like most of the questions the third film deals with, the answer is oblique or obscure to the inattentive. In this case, it's a yes: The boys, Ahmed and Babek Ahmed Poor, appear in this film bringing potted geraniums to the set of the film that's being made in post-quake Koker. Kiarostami doesn't identify them as such, but leaves the recognition to viewers familiar with the first film. In fact, it's best to watch the trilogy as a whole, as Kiarostami manages to move actors and characters around among the three films. In Through the Olive Trees, the actor/character known as Farhad is the same actor, Farhad Kheradmand, who played the director in And Life Goes On. A different actor, Mohamad Ali Keshavarz, plays the director in Through the Olive Trees. Sometimes we don't know whether we're watching actors performing in scenes for the film that's being made or the actual lives of the actors out of character -- in fact, the actors find it hard to separate the two. The third part of the trilogy is linked visually to the first by the zigzag path that people traverse to surmount the steep ridge that separates villages. And Through the Olive Trees links visually with And Life Goes On in that both films conclude with remarkable long-shot long takes in which characters from the film encounter each other at great distances from the camera. Taking the three films together, I think, only binds them into a whole masterwork -- an enigmatic, moving, frustrating, fascinating masterwork.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Life, and Nothing More. Abbas Kiarostami. 1992

#life and nothing more#koker trilogy#abbas kiarostami#iranian cinema#90s#1990s#cinema#film#documentary#movies#art

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Through the Olive Trees (1994) dir. Abbas Kiarostami

#through the olive trees#koker trilogy#abbas kiarostami#where is the friend's home#life and nothing more#zir-e derakhtan-e zaytun#under the olive trees#and life goes on#iran#iranian cinema#1990s#vintage#cinema#movie stills#film#movie#cinephile#1990s films#cinematography#criterion collection#iranian films#film stills#90s#iranian movie#asian cinema#asian movie#asian film#destiny's rainboww

108 notes

·

View notes

Text

E a Vida Continua (1992)

Abbas Kiarostami

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Where Is the Friend's Home?(1987), dir. Abbas Kiarostami

(1st part of Koker Trilogy)

#cinema#drama#family#koker trilogy#koker#part one#art#friends#abbas kiarostami#persian#persian language#cinemetography#where is the friend's home

51 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Abbas Kiarostami, Khane-ye dust kojast, 1987

#film#abbas kiarostami#Khane-ye dust kojast#where is the friend's home?#Farhad Saba#koker trilogy#iranian cinema#80s#film still

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

#through the olive trees#film#review#koker trilogy#criterion channel#criterion collection#abbas kiarostami

1 note

·

View note

Photo

112. Trilogia Koker: Através das Oliveiras (Zire darakhatan zeyton, 1994), dir. Abbas Kiarostami

#cinema#abbas kiarostami#hossein rezai#tahereh ladanian#Iranian cinema#1990s movies#classic movies#koker trilogy#drama#film crew#long shot#sequel#third part#filmmaking#earthquake#unrequited love#palme d'or nomination#world cinema#cult film#cult director#cinefilos

1 note

·

View note