#;; SANCTUARY! [ quasimodo: on notre dame de paris ]

Text

quasimodo tag dump!

#;; THIS TWISTED FLESH AND BONE [ quasimodo ]#;; NO SANCTUARY WITHOUT HER [ quasimodo: on esmeralda ]#;; MY DEFENDER [ quasimodo: on frollo ]#;; CAPTAIN OF THE GUARD [ quasimodo: on phoebus ]#;; SANCTUARY! [ quasimodo: on notre dame de paris ]#||x WHAT DO YOU KNOW OF ALL THE THINGS I FEEL? [ quasimodo: musings ]#||x WHO IS IT THAT YOU SEE? [ quasimodo: headcanon ]#||x WHAT I’D GIVE! WHAT I’D DARE! [ quasimodo: likes & interests ]#||x I DARE TO DREAM [ quasimodo: desires ]#||x QUASIMODO SAY SOMETHING! [ quasimodo: answered asks ]#||x FORGET YOUR SHYNESS [ quasimodo: starter call ]#(quasimodo) v; to live one day#(quasimodo) v; half formed#(quasimodo) v; stay in here#(quasimodo) v; no sanctuary#(quasimodo) v; hungry for the histories they show me#(quasimodo) v; modern#(quasimodo) v; freely walk about there#(quasimodo) v; when we have learned#(quasimodo) v; crossover#||x sheer calculated silliness [ ooc ]

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you have links to any good hunchback of Notre Dame fanfics??

BEHOLD!!! My favorite Hunchback fics!!

Most of these are Phoebus/Esmeralda since they’re my favorite characters/ship. There used to be a Quasimodo/Madeleine fic that I absolutely ADORED, but it seems it was wiped 😭 If I ever find it again I will update the post!

The Reason Why by chocolafied

Rated: G

Synopsis: Esmeralda is trapped in Notre Dame with nowhere to go. And to makes things worse, the very man who trapped her there returns to "pray" at the church. Will she still hate him, even though he tells her why he did it?

Mirrors are Liars, Armor Twice So by afterandalasia

Rated: T

Synopsis: Phoebus de Chateaupers died in the River Seine. It was particularly impressive considering he had never been born at all.

while the city slumbers by boltlightning

Rated: T

Synopsis: While Paris burns, Esmeralda pulls a traitor from his watery grave. (Or: how Esmeralda and Phoebus made their way to Notre Dame after Phoebus' impromptu dismissal.)

Into the Sunlight by HauntedTerrarium

Rated: T

Synopsis: The smoke clears, and Paris struggles to be reborn. In the aftermath of terrible tragedy, however, there is hope. The heroes of our story begin to rebuild, to heal, and to leave the world a better place than how they found it.

Restless by bronwe-iris

Rated: T

Synopsis: Married, and now most recently having become a father, it has been years since Phoebus has seen battle. And yet, some horrors never truly leave a person. Who does one turn to when the nightmares come?

Lastly, a shameful plug for my own fic 🫣

holy ground

Rated: T

Synopsis: As the city begins to hunt for Esmeralda, she seeks sanctuary within the stone walls of Notre Dame, and a chance encounter with Phoebus takes her by surprise.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1996)

As observed in the last post, when the Disney Renaissance period "ends" isn't always entirely clear. Even after the high water mark of The Lion King, the animated films were still making money (esp. on the merchandising end) and getting good reviews, just somewhat less effusive ones depending on the film. Perhaps no film during this period was regarded with more curiosity and suspicion than their attempt at adapting Victor Hugo's classic French novel The Hunchback of Notre Dame (though if you want to get technical, that's the title of most adaptations, whereas the original French title is Notre Dame de Paris). The story of Quasimodo is often a dark one, after all, full of themes like religious hypocrisy and discrimination against minorities. Could Disney handle that, critics seemed to ask, or should they even TRY? Well, they ultimately did, and we have the film in front of us to judge. Let's dig in.

(Quick note: the film uses the outdated g-slur to refer to Roma characters throughout. I will not be doing so for sensitivity purposes.)

We open in 15th century Paris, as Clopin (Paul Kandel), leader of the city's Roma begins to narrate a story, "a tale of a man...and a monster." Twenty years ago, Judge Claude Frollo (Tony Jay) murdered a Roma woman when pursuing her for a presumed theft. The cargo turns out to be her son, who Frollo classifies as a monster for his hunchbacked deformities, and he nearly murders him to boot. But the Archdeacon of Notre Dame (David Ogden Stiers) stops him, warning that the "eyes" of Notre Dame, and possibly God Himself, will witness this crime. A shaken Frollo agrees to raise Quasimodo (Tom Hulce), but shuts him away in the bell tower. As the present day opens, Quasimodo yearns to join the outside world, with his gargoyle friends Hugo (Jason Alexander), Victor (Charles Kimbrough), and Laverne (Mary Wickes, in her final film role) as his only companions. But Frollo insists they would never accept him, and Quasimodo nearly seems ready to accept that lonely lot in life, so much has he internalized this abuse. His friends, however, encourage him to sneak out to the yearly Feast of Fools, just for one day. He works up the courage to do so, only to encounter the beautiful Roma Esmeralda (Demi Moore) and be crowned the King of Fools. After the crowd turns on him, Esmeralda comes to his rescue, only to be pursued by Frollo and the goodhearted captain Phoebus (Kevin Kline), who convinces her to take sanctuary in the church. Things quickly become a waiting game as Quasimodo and Esmeralda begin to bond over sharing an outsider status, and he begins to consider a potential life "out there", as Frollo's anger begins to twist into hatred...and lust.

The first thing that has to be said about Hunchback is that it's one of the best-looking films the studio ever made. Like Tarzan after it, CGI techniques were heavily used to give Notre Dame a real sense of place and atmosphere previously though unachievable. You truly FEEL the vastness of the cathedral and Paris, occasionally feeling just a bit of awe in the process, but thankfully directors Gary Trousdale and Kirk Wise (Beauty and the Beast, Atlantis: The Lost Empire) never let them overwhelm the characters and their emotions. Some of this hasn't aged gracefully (the CGI crowds are definitely a little ropey when you look close), but the overall effect remains outstanding.

So too does the character animation, which is remarkable in its complexity. Quasimodo alone would be a challenge for most animators, but James Baxter is not most animators, and he gives the hunchback a genuine soulfulness in addition to making that seemingly impossible body move with pencils. Kathy Zielinski, meanwhile, takes what could have felt like a caricature in Frollo and makes him into a real, terrifying person. You feel his pain...and gape in horror at his cruelty. Tony Fucile's Esmeralda is vivacious and vibrant, Russ Edmonds makes Phoebus a little rougher than most handsome Disney leading men even with his good heart, and Mike Surrey grants Clopin an intriguing ambiguity; right up until the end, you're never totally sure what he's after.

The story is just as good as the visuals. I will admit upfront that it probably bites off more than it can chew. There is a LOT to cover here in terms of the intersections of racism, religious hypocrisy, and othering of people deemed "monsters" because of their disabilities. Especially since smarter people than me have pointed out this was NOT wholly Victor Hugo's original intent, but that the story transformed into a parable about discrimination thanks to Hollywood and other adaptations. It's possible that anyone could balk at it, much less the largely-compositionally-white Disney animation studio of the 1990s. Yet it has to be said that a genuine, earnest effort is made here even with some fumbles (which we'll get to later).

A useful comparison point is the previous year's Pocahontas. I can genuinely say I kind of hate that film outside of a few caveats, and one big reason why is that the characters feel so flat in their assigned roles. Nobody surprises or does anything unexpected, there's no nuance in the colors of the wind there, and even the characters you think could have affecting arcs are unbearably stiff. Not so here. Quasimodo is an excellent lead, for starters; even if he's gentler and less outright antisocial than other adaptations or the source material, he's allowed to be flawed in terms of parroting assumptions about Roma planted in him by Frollo and initially feeling entitled to Esmeralda's love because she was kind to him. He rises to heroism instead of having it be assumed. Frollo, too, is more complex than most Disney villains. Not sympathetic, precisely, but you get the sense that he really is just a miserable person at the end of the day, directing that misery outward as the contradictions between his religious piety, his racism, and his lust tear him up inside. Esmeralda is a little sexualized, it's true, and perhaps a little more noble than she might truly be in the situation, but she's a passionate, driven adult with a sense of humor. Which feels rare even now in animated kid's movies. The triangle that develops between her, Quasimodo, and Phoebus is intriguing because we can see it going either way, rather than having Phoebus be an obvious bad egg. I like his arc, too, as the Roma gain a human face and he grows increasingly uncomfortable with his complicity.

The voice cast helps with this considerably, giving stellar performances across the board. Helping is that they have one of the best soundtracks in the Disney canon backing them up, with Alan Menken and Stephen Schwartz giving us banger after banger. "The Bells of Notre Dame" stands out especially for getting across a ton of story and character notes as elegantly as the likes of "Belle", "Circle of Life", and "The Family Madrigal." (Credit to Kandel, too, for hitting that insane high D note at the end of both it and the final reprise) Plus, I'm always a sucker for Badass Ominous Latin Chanting, and that's all over this score. We also get TWO "I Want" songs for the price of one, with "Out There" and "God Help The Outcasts" being excellent mission statements for Quasimodo and Esmeralda. "Hellfire" is the most chilling Villain Song in the entire canon, taking us down a road of darkness and flame. And "Topsy Turvy" feels underrated as a comedy song, feeling almost like something you could hear in another Hugo-derived musical, Les Miserables, in the clever rhyming and archaic word usage. (I'm also partial to "The Court of Miracles", which is short, but has a nicely sinister bounce)

In terms OF the actors, Tom Hulce is honestly an interesting choice for Quasimodo given that his best-known performance otherwise is as Mozart in Amadeus. A great film, and great acting, but Mozart is a markedly different character in that he is cheerfully obnoxious even whilst remaining in our sympathies. Here, Hulce finds a wistful quality in his tones, childlike without ever being childish, which is a hard balance to strike. And he knocks "Out There" out of the park, as it were. Tony Jay, meanwhile, gives the performance of his lifetime as Frollo, mining every scrap of loathsome humanity he can without ever losing the reality of the man. His rendition of "Hellfire" always leaves me awestruck. Moore has a distinct, smoky tone that aids Esmeralda spectacularly even if we can question the ethics of casting a white woman as a dark-skinned Roma in retrospect, and Kline matches her well in terms of being funny and down-to-Earth, making us believe in Phoebus' turn.

(Also, I'd be remiss if I didn't mention Stiers' cameo at least a little bit. He was a good luck charm for Disney in this period, and he gives the Archdeacon genuine warmth to contrast Frollo's bigotry, a necessary one given how brutal that becomes)

Now there are some fumbles, even if they don't blemish the film overmuch for me. The first is the depiction of the Roma, which can run a little inconsistently. It's laudable that the movie is sympathetic to their plight and doesn't make any mealy-mouthed both-sides statements about it the way Pocahontas tries to run with an ill-defined "hatred" as the Aesop. Frollo is just straight-up racist and that's how we're doing this. But they also get played as comic relief and we don't get much internal dialogue on them outside of Esmeralda and Clopin (though as said, I appreciate that he has purposeful ambiguity in seeming like a gleeful jester one moment, then a tough street boss the next).

The second is the gargoyles, who you may have noticed haven't been mentioned much up to now. That's because I'm of two minds about them. On the one hand, I don't think they're bad characters. The animation on them is as good as the rest of the film, and you could tell the animators had fun figuring out how to move stone figures around. Alexander, Kimbrough, and Wickes all give excellent comedic performances, and especially in the early part of the film, they serve a useful function as keeping the mood light and confidants for Quasimodo. There are much worse Disney sidekicks purely on the merits (fuck you, Gurgi, go to hell). Nor do I object to comic relief on its face. I adore comedy-as-characterization, and Disney sidekicks can often be a useful counterbalance.

What I dispute is the usage here. To me, there's an obvious arc of Quasimodo shedding his comfort levels as he grows up and decides to engage in the outside world. But the gargoyles...keep showing up past a point where it feels necessary. You get the sense the filmmakers were nervous about just HOW dark and adult the rest of the film was, and were hedging their bets. This is best exemplified in their song "A Guy Like You." On its face, it's a funny, catchy number that the actors sing the hell out of. And the dramatic purpose (building Quasimodo's confidence about his romance before learning that Esmeralda has fallen for Phoebus) is solid. But it's just...too much. These guys aren't the Genie or Timon and Pumbaa, and they shouldn't be. Also between them and Esmeralda's pet goat Dhjali, who's also Fine mechanically, and Clopin already being funny in cleverer ways, it begins to feel a smidge crowded.

One quibble I DON'T have is with the ending. This remains the most criticized part of the film, given that the book ends tragically with Frollo, Quasimodo, and Esmeralda all dead, and some variation on this tends to stick for a lot of adaptations (in fact, both Disney's later German and English-language stage adaptations hewed closer to the novel, if not exactly in terms of circumstances). By contrast, here we get an uplifting ending where not only is Frollo the only casualty (and with a bitchin' variation on the Disney Villain Death to boot), Quasimodo is accepted by the citizens of Paris. Unrealistic? Maybe. Does my heart melt every time that little girl comes up to feel Quasimodo's face? Absolutely. Look, I'm not someone who thinks we need to treat minorities/disadvantaged people like glass dolls in narratives. We can have bad things happen to them without it being Le Problematique. But given the history, is it really so terrible to give a hunchback a happy ending on occasion? I think not, and for this version of the story, they absolutely arrive at the correct decision.

The mood around the film was slightly more muted upon its release. It made money, the critical reception was generally positive-even in France!-and some critics like Roger Ebert gave it effusive reviews. But it was usually agreed that Disney had done its usual thing of simplifying a popular narrative for mass consumption the way they did for fairy tales and such. Hard to totally argue against that point, but I would posit that, as said, the story had already mutated into a very different form thanks to various other adaptations. You'd hardly think Les Miserables would be a good crowd-pleasing musical either at first glance. Even if it totally doesn't stick the landing, this remains one of my favorite Disney films because it TRIED, damn it. It's imperfect, but beautiful.

Could say that about our hunchback, couldn't we?

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

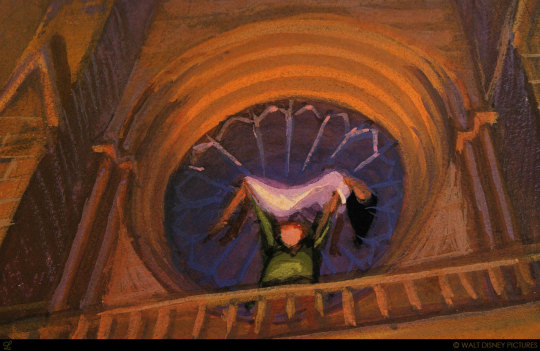

"Sanctuary!"

The concept art for Disney's "The Hunchback of Notre Dame".

#notre dame de paris#the hunchback of notre dame#nddp movies#nddp#hond#la esmeralda#esmeralda#quasimodo and esmeralda#esmeralda and quasimodo#quasimodo#disney#notre dame cathedral#notre dame#sanctuary#disney concept art#concept art#hond concept art

121 notes

·

View notes

Text

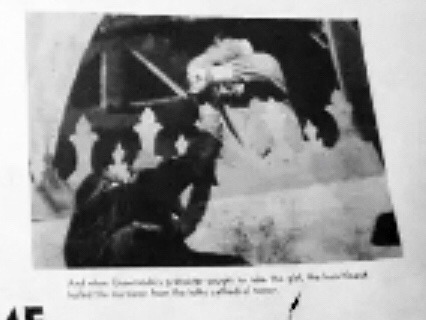

1939 Hunchback of Notre Dame Deleted Scenes:

The following scenes are present within the screenplay, dated around July 1939 (shortly before principal photography began on the film). Some of these may have been shot, while others may have never been filmed.

- When the band of Gypsies are halted from entering Paris at the city border, the patriarch of them points out how the guards who are forbidding them are of non French ethic backgrounds, groups that were once persecuted like the Gypsies, but the soldiers continue to refuse their entrance. In the film, this scene is much shorter. (“You came yesterday, we come today”)

- alternate scene of the woman being frightened by Quasimodo. In the script she is a pregnant woman who is mildly concerned, and in the film she is terrified and runs to her grandmother for comfort.

- Frollo and the king converse in the king’s private box during the festival. Frollo is bigoted and dismissive of the heresy of the festivities, and the king is surprised to see Frollo accidentally smile at a person balancing on a ball.

(The shot of a man balancing on a ball is used during the festival montage sequence. This, to me, suggests that this scene was filmed, but removed and altered in the editing process.)

- The introduction of Captain Phoebus. He, along with his fiancé Fleur de Lys, her friend Aloise, and the soldier Philippe exchange small talk at the Festival of Fools. Aloise thinks Gringoire is handsome, and Phoebus belittles him, saying that anybody can write verse poetry.

(A publicity still exists of the scene, implying that it may have been filmed)

- Pierre Gringoire’s play is a much longer sequence, and is politically subversive, showing how the laboring classes provide for society while the clergy and nobility do nothing. The nobles are outraged by the heresy, but the king argues that such offensive ideas are important to listen to. The play also contains scenes of the roman gods.

(All of the actors and their character-appropriate costumes appear in the final film, which means that these scenes could conceivably been filmed, and later deleted for pacing reasons.)

- When Esmeralda first claims “sanctuary” in Notre Dame, there is a notably etended scene of her talking to King Louis XI. The script makes it clear that she wishes for the king to advocate for the rights of the Gypsies, and of herself. Only a small portion of this scene is in the final film.

- Gringoire wanders the streets after his play is failed and city doesn’t pay him for it. He offers to write poetry for a serving of chicken, but the food vendor cannot read so he refuses the offer.

- during the trial of Gringoire, several candidates, one of them named “ugly Madeline” show vague interest in the poet but don’t want to marry him because he’s not attractive enough.

- as a wedding present, Esmeralda is given a monkey named bimbo. The monkey is seen and even named in the final film, but the context of its presence is never given.

- during the pillory sequence, a pair of nuns recite Quasimodo’s backstory (told in flashbacks), how he was adopted by Frollo and outcast by the world.

(The 1996 restored score to the film has the music run much longer than the filmed scene, implying that the pillory sequence was originally longer)

- The planning of the birthday party of Fleur de Lys. She and her companions dream of the party later that night, and Fleur demands a fortune teller be invited. Phoebus brings her a birthday gift.

- after being whipped, Quasimodo sulks in the bell tower to lick his wounds.

-The party of the nobles is extended. More scenes of Fleur de Lys and her companions

- Clopin and the beggar Queen show up to the party, disguised as the count and countess of Mendozza. They steal a jewel from Fleur’s mother.

- Love scene between Phoebus and Esmeralda is extended. More romantic dialogue. She has him pose and walk around to look tall, as in the novel. Esmeralda eventually tries to refuse him, because she suspects that he is in love with Fleur de Lys.

- Quasimodo watches the events of the party from the heights of Notre Dame, as he is still processing his feelings of love for Esmeralda. When she is arrested, that is when he begins to madly ring the bells of the church as in the film.

- extended sequence of Quasimodo trying to take the blame for Phoebus’ murder. The jury is thrilled at the prospect of Quasimodo being executed. Frollo dismisses this evidence on the grounds that the hunchback was ringing the bells at the time and sends him to be held in his office.

- While Esmeralda is being tortured, Frollo watched from a secret door in his office. Quasimodo keeps trying to convince Frollo that he is the murderer, by presenting his master with a knife that he supposedly used.

- After the procurator reads Esmeralda’s sentence in Latin, the king remarks how unfair it is that criminals are not even allowed to know what they are guilty of in their own language and how this issue must be reformed.

- During the preparation to execute Esmeralda, Fleur feels sorry for the Gypsy girl. She says that if she never invited her to her party, then both she and Phoebus would have lived. Her mother, named Heloise in this version, chastises her for such pity.

- After rescuing Esmeralda, Quasimodo rings the bells in triumph while she is asleep. Frollo enters, trying to find the Gypsy, and Quasimodo threatens him by using the rope of a bell like a bullwhip.

- When Clopin rallies his people to seige the church, a character named Mathias (Mathias hungadi?) stirs up support by mentioning all of the plunder to be had.

- The archbishop, on his way to warn the king of the upcoming uprising, runs into Clopin, and tries to talk him out of assaulting the church.

- Clopin’s death was originally much closer to the novel, where he would be killed by the king’s soldiers while swinging a sickle and urging his people to fight on.

- The original ending. Frollo tries to assault Esmeralda and Quasimodo intervenes. The hunchback, though stabbed by Frollo, pushes his master off the cathedral. Frollo dangles on an architectural projection, and eventually falls to his death, like in the book.

- Before she leaves, Esmeralda comforts Quasimodo, unaware he is dying.

- Quasimodo rings the bells one final time before he dies alone of his injuries.

(This scene is described in a rare set of press materials, and the following photo that accompanied it imply that it was filmed. In addition, some of the shots of Quasimodo in the final film feel like insert shots in hindsight. The image quality is quite poor, but these are the only images I have been able to discover.)

Side note: This deleted ending is taken almost beat for beat from the 1923 silent version, which this film was greenlit and advertised as a direct remake of. Ironically enough, most of the elements of this version that were inspired from that film, such as the ending and the addition of a Beggar Queen character, were largely excised from the final product.

#hunchback of notre dame#deleted scenes#victor hugo#1939#charles laughton#research#this isn't an exhaustive list#but I think its more than passable#playing historian can be fun

44 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Notre Dame is the kind of place you think will always be there...because it’s always been there. And now it’s odd to think I am now one of the lucky people who will have known it as it once was...who went to mass there, strolled on top of the towers, lit candles in its alcoves, joked about Quasimodo while standing next to the gargoyles, and marveled over the sunset from the roof. I never went to Paris until 2015 — no time/money/childcare/anyone to go with — and besides, it wasn’t going anywhere. I’d tell myself, “Maybe next year when I get more money/time/childcare/someone to go with, I’ll go.” Years of that. And then I survived breast cancer and knew Paris couldn’t wait. A few months later I arrived in the city all alone and with just enough money to snack on Nutella crepes. The first place I went was Notre Dame. I cried when I stood in front of it because I was standing in front of a witness to history. There it was, the physical embodiment of sacrifice and spirit, of humanity and heart—and it was alive. This was no cold sanctuary or relic of the past. Instead it hummed with life and love. I’ve gone back to Paris four times since and always stay within a couple blocks so I can see the spire from my room, and hear the bells as I wake up, and so I can visit every day. And now heartbreak. I feel bereft, I’m still at al loss, and yet so grateful for the memories. I cannot imagine the grief of the average Parisian. But I’ve already donated to the rebuilding fund. That’s the least I can do for a cathedral and a city that has saved my heart and soul so many times. #notredame #notredamedeparis #paris #parisjetaime (at Notre Dame de Paris) https://www.instagram.com/p/BwTyvGtgdUy/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=5dznvaidwtsm

1 note

·

View note

Text

This will kill That: historical preservation, Victor Hugo, and Notre Dame Cathedral

Early in the novel Notre Dame De Paris by Victor Hugo, Claude Frollo utters this line in seeming agonized frustration, terrifying in its meaning. He directs the eyes of two visitors from a book on his desk to the massive silhouette of Notre Dame cathedral beyond his door, then announces: "This will kill that."

“This” is the book. The arrival of printing, mass produced information and the dissemination of it to the populace, “That” is the cathedral, and all that goes along with it. "Small things overcome great ones," Frollo laments, "the book will kill the building."

For Hugo, the language of mankind to that point has and had been architecture. While the language of the scholar and the educated elite was Latin, the language of the common people was architecture. The grandeur of the cathedral pointed eyes to the glory of heaven, the humbleness of their common dwelling, to the state of man in the sight of his deity.

That language reaches a sort of climax in the Gothic Cathedral and, indeed, the grandeur of Notre Dame. Hugo asserts; in a sort of righteous fervor; that priests had controlled even that language for centuries. From the reflected dogmatic oppression of the squared, Romanesque cathedral, to the flying Gothic architecture that lifts men’s souls, giving wings to poetic liberation with flying buttresses, large stained glass windows, and the awe-inspiring flight of high towers and distant bells.

It is fitting then, that this behemoth of man’s invention and vision should fall to the singular smallness of something so common as movable type. A post-enlightenment sort of David and Goliath. It is fairly easy to see then if we interrogate the style and concepts of this book that Hugo felt architects had nothing left to say. All was neo-this and neo-that, and a sort of re-imagination of the past.

“This” would kill “That.”

And yet, Notre Dame De Paris includes a sort of plea within its pages to acknowledge everything the then-crumbling building represents and to save it from the future ravages of time. By Hugo’s time and the beginning of the research done for the novel, the Cathedral was over 500 years old and had become something of a ruin.

Broken and desecrated after changing governments, lack of repair, and perhaps most notably ravaged by the Huguenots for being idolatrous, AND THEN all the beheading of all the kings of Israel for supposedly being “French Aristocrats and Royalty” during the Revolution, Notre Dame was quite a mess. And, unfortunately, would remain a mess until Hugo could finish the novel; there’s some fun gossip and shade there if you look into the writing-of; and other people began to take interest. This has also been credited as beginning the concept of Historical Preservation, which really only began to take hold in America and the UK post-WW2. (Some people also blame Robert Moses. It sort of depends on your point of view.)

The general theme of the novel is that Notre Dame will and has outlived countless lives of humanity, and all their ineptitude, terrible decisions, and flaws, will pale in comparison to the edifice and it’s lifespan.... should we care to preserve it.

The grand irony, however, is that the book itself became a NEW “This” and was destroyed itself by a new “That” : the advent of movies and hollywood. The story changed, sometimes drastically, cutting and adding characters and changing their motivations, throughout each successor to the story that came before. Frollo became something other than a priest.

Esmeralda went from a white girl stolen by g*psies, to a g*psy herself.

Quasimodo went from deformed man to movie monster to anti hero to protagonist and back again.

Phoebus went from soldier to revolutionary and through some convoluted developments.

Gringoire is left out of most productions post-1930s.

Fleur De Lys often doesn’t feature....

The film has killed the book. This, has killed That. And time marches on.

From Lindsay Ellis: The Case for Disney’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame

From Bartleby:

It was a premonition that human thought, in changing its outward form, was also about to change its outward mode of expression; that the dominant idea of each generation would, in future, be embodied in a new material, a new fashion; that the book of stone, so solid and so enduring, was to give way to the book of paper, more solid and more enduring still. In this respect the vague formula of the Archdeacon had a second meaning—that one Art would dethrone another Art: Printing will destroy Architecture. 4

In effect, from the very beginning of things down to the fifteenth century of the Christian era inclusive, architecture is the great book of the human race, man’s chief means of expressing the various stages of his development, whether physical or mental. 5

When the memory of the primitive races began to be surcharged, when the load of tradition carried about by the human family grew so heavy and disordered that the word, naked and fleeting, ran danger of being lost by the way, they transcribed it on the ground by the most visible, the most lasting, and at the same time most natural means. They enclosed each tradition in a monument. 6

The first monuments were simply squares of rock “which had not been touched by iron,” as says Moses. Architecture began like all writing. It was first an alphabet. A stone was planted upright and it was a letter, and each letter was a hieroglyph, and on every hieroglyph rested a group of ideas, like the capital on the column. Thus did the primitive races act at the same moment over the entire face of the globe. One finds the “upright stone” of the Celts in Asiatic Siberia and on the pampas of America. 7

Presently they constructed words. Stone was laid upon stone, these granite syllables were coupled together, the word essayed some combinations. The Celtic dolmen and cromlech, the Etruscan tumulus, the Hebrew galgal, are words—some of them, the tumulus in particular, are proper names. Occasionally, when there were many stones and a vast expanse of ground, they wrote a sentence. The immense mass of stones at Karnac is already a complete formula. 8

Last of all they made books. Traditions had ended by bringing forth symbols, under which they disappeared like the trunk of a tree under its foliage. These symbols, in which all humanity believed, continued to grow and multiply, becoming more and more complex; the primitive monuments—themselves scarcely expressing the original traditions, and, like them, simple, rough-hewn, and planted in the soil—no longer sufficed to contain them; they overflowed at every point. Of necessity the symbol must expand into the edifice. Architecture followed the development of human thought; it became a giant with a thousand heads, a thousand arms, and caught and concentrated in one eternal, visible, tangible form all this floating symbolism. While Dædalus, who is strength, was measuring; while Orpheus, who is intelligence, was singing—the pillar, which is a letter; the arch, which is a syllable; the pyramid, which is a word, set in motion at once by a law of geometry and a law of poetry, began to group themselves together, to combine, to blend, to sink, to rise, stood side by side on the ground, piled themselves up into the sky, till, to the dictation of the prevailing idea of the epoch, they had written these marvelous books which are equally marvellous edifices: the Pagoda of Eklinga, the Pyramids of Egypt, and the Temple of Solomon. 9

The parent idea, the Word, was not only contained in the foundation of these edifices, but in their structure. Solomon’s Temple, for example, was not simply the cover of the sacred book, it was the sacred book itself. On each of its concentric enclosures the priest might read the Word translated and made manifest to the eye, might follow its transformations from sanctuary to sanctuary, till at last he could lay hold upon it in its final tabernacle, under its most concrete form, which yet was architecture—the Ark. Thus the Word was enclosed in the edifice, but its image was visible on its outer covering, like the human figure depicted on the coffin of a mummy. 10

Again, not only the structure of the edifice but its situation revealed the idea it embodied. According as the thought to be expressed was gracious or sombre, Greece crowned her mountains with temples harmonious to the eye; India disembowelled herself to hew out those massive subterranean pagodas which are supported by rows of gigantic granite elephants. 11

Thus, during the first six thousand years of the world—from the most immemorial temple of Hindustan to the Cathedral at Cologne—architecture has been the great manuscript of the human race. And this is true to such a degree, that not only every religious symbol, but every human thought, has its page and its memorial in that vast book. 12

Every civilization begins with theocracy and ends with democracy.

#Haven Yells About Stuff#Historical Preservation#historical architecture#Notre Dame de Paris#Victor Hugo#a truncated history of things

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Esmeralda's birth-name was Agnès. She is the love child of Paquette Guybertaut, nicknamed 'la Chantefleurie', an orphaned minstrel's daughter who lives in Rheims. Paquette has become a prostitute after being seduced by a young nobleman, and lives a miserable life in poverty and loneliness. Agnes's birth makes Paquette happy once more, and she lavishes attention and care upon her adored child: even the neighbours begin to forgive Paquette for her past behaviour when they watch the pair. Tragedy strikes, however, when Gypsies kidnap the young baby, leaving a hideously deformed child (the infant Quasimodo) in place. The townsfolk come to the conclusion that the Gypsies have cannibalised baby Agnes; the mother flees Rheims in despair, and the deformed child is exorcised and sent to Paris, to be left on the foundling bed at Notre-Dame.

Fifteen years later, Agnes—now named La Esmeralda, in reference to the paste emerald she wears around her neck—is living happily amongst the Gypsies in Paris. She serves as a public dancer. Her pet goat Djali also performs counting tricks with a tambourine, an act later used as courtroom evidence that Esmeralda is a witch.

Claude Frollo sends his adopted son Quasimodo to kidnap Esmeralda from the streets. Esmeralda is rescued by Captain Phoebus, with whom she instantly falls in love to the point of obsession. Later that night, Clopin Trouillefou, the King of the Truands, prepares to execute a poet named Pierre Gringoire for trespassing the Truands' territory known as The Court of Miracles. In a compassionate act to save his life, Esmeralda agrees to marry Gringoire.

When Quasimodo is sentenced to the pillory for his attempted kidnapping, it is Esmeralda, his victim, who pities him and serves him water. Because of this, he falls deeply in love with her, even though she is too disgusted by his ugliness even to let him kiss her hand. There, Paquette la Chantefleurie, now known as Sister Gudule, an anchoress, curses Esmeralda, claiming she and the other Gypsies ate her lost child.

Two months later, Esmeralda is walking in the streets when Fleur-de-Lys de Gondelaurier, the fiancée of Phoebus, and her wealthy, aristocratic friends spot the Gypsy girl from the Gondelaurier house. Fleur-de-Lys becomes jealous of Esmeralda's beauty and pretends to not see her, but Fleur's friends call Esmeralda to them out of curiosity. When Esmeralda enters the room, tension immediately appears—the wealthy young women, who all appear equally pretty when compared to each other, are plain in comparison to Esmeralda. Knowing that Esmeralda's beauty far surpasses their own, the aristocrats make fun of her clothes instead. Phoebus tries to make Esmeralda feel better, but Fleur grabs Esmeralda's bag and opens it. Pieces of wood with letters written on them fall out, and Djali moves the letters to spell out "Phoebus". Fleur, realizing that she now has competition, calls Esmeralda a witch and passes out. Esmeralda runs off, and Phoebus follows her.

Later that month, she meets with Phoebus and declares her love for him. Phoebus takes the opportunity to kiss her as she speaks, and he pretends to love her. He asks Esmeralda what the point of marriage is (he has no intentions of leaving his fiancée Fleur-de-Lys, he just wants to "sleep" with Esmeralda), which leaves the girl hurt. Phoebus, seeing the girl's reaction, pretends to be sad and says that Esmeralda must no longer love him. Esmeralda then says that she does love him and will do whatever he asks. Phoebus begins to undo Esmeralda's shirt and kisses her again. Frollo, who was watching from behind a door, bursts into the room in a jealous rage, stabs Phoebus, and flees. Esmeralda passes out at the sight of Frollo, and when she comes to, she finds herself framed for murder, for a miscommunication makes the jury believe that Phoebus is in fact dead. Esmeralda proclaims her innocence, but when she is threatened with having her foot crushed in a vice, she confesses. The court sentences her to death for murder and witchcraft (the court has seen Djali's spelling trick), and she is locked away in a cell. Frollo visits her, and Esmeralda hides in the corner (before this point in the book, the readers know that Frollo's lustful obsession of the girl has caused him to publicly denounce and stalk her). Frollo tells Esmeralda about his inner conflict about her, and he gives her an ultimatum: give herself to him or face death. Esmeralda, repulsed that Frollo would harm her to this extent for his own selfishness, refuses. Frollo, mad with emotion, leaves the city. The next day, minutes before she is to be hanged, Quasimodo dramatically arrives from Notre Dame, takes Esmeralda, and runs back in while crying, "Sanctuary!".

While she stays in the cell at Notre Dame, she slowly becomes friendly with Quasimodo and is able to look past his misshapen exterior. Quasimodo gives her a high-pitched whistle, one of the few things he can still hear, and instructs her to use it whenever she needs help. One day, Esmeralda spots Phoebus walking past the cathedral. She asks Quasimodo to follow the captain, but when Quasimodo finds where Phoebus is, he sees Phoebus leaving his fiancée's house. Quasimodo tells him that Esmeralda wants to see him: Phoebus, believing Esmeralda to be dead, believes Quasimodo to be a devil summoning him to Esmeralda in Hell, and flees in terror. Quasimodo returns and says he did not find Phoebus.

For weeks Esmeralda and Quasimodo live a quiet life, whilst Frollo hides in his private chambers thinking about what to do next. One night, he brings his master key to Esmeralda's room. The girl wakes up and is paralyzed with terror until Frollo pins her to the bed with his body and tries to rape her. Unable to fight him off, Esmeralda grabs the whistle and frantically blows it. Before Frollo can make sense of her actions, Quasimodo picks him up, slams him against the wall, and beats him with the intention of killing him. Before Quasimodo can finish, Frollo stumbles into the moonlight pouring in from a far window. Quasimodo sees who Esmeralda's attacker is, and drops him in surprise. Frollo fumes with fury, and tells Esmeralda that no one will have her if he cannot, before leaving the cathedral.

Frollo finds Gringoire and informs him that the Parlement has voted to remove Esmeralda from the sanctuary, and intends to order soldiers to forcibly accomplish the task. Gringoire reluctantly agrees to save the girl, and formulates a plan with Frollo. The next night, Gringoire leads all the Parisian Gypsies to Notre Dame to rescue Esmeralda. Mistakenly responding to this assault, Quasimodo retaliates and uses Notre Dame's defenses to fight the gypsies, thinking that these people want to turn in Esmeralda. News of this soon comes to King Louis XI, and he sends soldiers (including Phoebus) to end the riot and hang Esmeralda. They reach Notre Dame in time to save Quasimodo, who is outnumbered and unable to prevent the gypsies from storming the Gallery of Kings. The gypsies are slaughtered by the king's men, while Quasimodo (who has not realised that the soldiers wish to hang Esmeralda) runs to Esmeralda's room. He goes into a panic when she is nowhere to be found.

During the attack, Gringoire and a cloaked stranger slip into Notre Dame and find Esmeralda about to sneak out of the cathedral (she had feared that soldiers were trying to take her away when she heard the battle). When Gringoire offers to save the girl, she agrees and goes with the two men. The three get into a nearby boat and paddle down the Seine, and she passes out when she hears many people chanting for her death.

When Esmeralda wakes, she finds that Gringoire is gone, and the stranger is Frollo. Frollo once more gives Esmeralda a choice: stay with him or be handed over to the soldiers. The girl asks to be executed. Angry, Frollo casts her into the arms of Gudule (Paquette Guybertaut). There, the two women realize that Esmeralda is in fact Gudule's lost child. The guards arrive, and Gudule pleads for them to show Esmeralda and herself mercy. Gudule follows the guards to the scaffold, kicking and biting along the way. A guard throws Gudule to the ground; she hits her head and dies.

Back at Notre Dame, Quasimodo is still frantically looking for his friend. He goes to the top of the north tower and finds Frollo there. Quasimodo notes Frollo's demented appearance and follows his gaze, where he sees Esmeralda in a white dress, dangling in her death throes from the scaffold.

#notre dame#Esmeralda#Quasimodo#Cosplay#Disney#disney princess#Disney cosplay#hunchbackofnotredamecosplay#hunchback of notre dame#hunchback of notre dame cosplay#costume#cosmaker#design#fantasy#fashion#geek#Geek Girl#model#corset#wig#ookamiworkroom#ookamistore

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Our Lady

I’m not French by heritage, but I often feel an honorary connection to France that goes beyond an interest in wine and black turtlenecks to enter deeper territory. The concept of laïcité is one of those strong, fundamental bonds. The word denotes “secularity” and is used to describe France’s governmental policy of separating church from state, but that simple definition doesn’t cover the nation’s complex relationship with agnosticism and faith. Or mine. Like France, I grew up Catholic but put religion to the side when I matured. Nonetheless, our memories remain, and our lives are built on a foundation of Christian habits. However empty of religious significance a cathedral may now be, the symbolic importance persists.

It’s Notre-Dame I’m thinking of, like all the world this week. Watching news coverage of it burning was an unexpectedly emotional experience, one of the most devastating things I’ve seen not involving the loss of human life. I felt dread, and shame, and at times the sense of standing at the very end of history. But the sun rose and the fire waned and the temple stood more solid and intact than any of us had dreamed it could. What had seemed a grand finale was just another chapter in a long story.

That started me thinking about all the stories that have come before this one. The fictional Caribbean cathedral of Beauséjour in Patrick Leigh Fermor’s The Violins of Saint-Jacques, "unroofed by a score of hurricanes and a score of times roofed over again”; the real-life shelling of the cathedral at Reims during World War I; the fire at York Minster in the 1980s... As Umberto Eco writes in The Name of the Rose (a book that features a terrible fire in a medieval abbey), “every story tells a story that has already been told.”

On the day of the Notre-Dame fire, a friend tweeted a prescient excerpt from Victor Hugo:

All eyes were raised to the top of the tower. What they saw was extraordinary. On the top of the highest gallery, higher than the central rose-window, rose a great flame between the two bell towers with swirls of sparks, a great, ragged, furious flame, from which at times the wind would snatch a strip into the smoke. Beneath this flame, beneath the sombre balustrade with its cut-out trefoils glowing with fire, two spouts in the form of monstrous gargoyles spewed out this burning rain, whose silvery trickle stood out against the darkness of the lower part of the façade. As they came nearer the ground, the two jets of liquid lead spread out into showers of spray, like water spurting from the countless holes of a watering can. Above the flames, the enormous towers, each showing two sharply distinct faces, one all black, the other all red, seemed bigger still with the immensity of the shadow they projected right up to the sky. Their innumerable carvings of devils and dragons took on a macabre appearance. The restless brightness of the flame made them move before one’s eyes. There were wyverns which looked as though they were laughing, gargoyles which one seemed to hear yelping, salamanders blowing on to the fire, tarasques sneezing in the smoke. And among those monsters roused from their stone slumbers by the flame, by the noise, was one walking about, who could be seen from time to time passing across the blazing front of the pyre like a bat in front of a candle.

The moving figure, of course, is the hunchbacked Quasimodo in Notre-Dame de Paris, the 1831 novel from which this passage, translated by Alban Krailsheimer, comes. Hugo wrote his book at a time when the cathedral was in decay, His love for its ancient stones, transmuted into literature, galvanized his fellow citizens into restoring and preserving it for future generations. For us.

So now it’s our turn. This catastrophe has already inspired global concern and a billion dollars in pledged support for rebuilding efforts. Within days of the trauma, we’ve already seen how we can rise to the occasion, how easily we can remedy our ills when our will is strong enough. I read another tweet, one that also referenced Victor Hugo, that spoke to me even more strongly about the collective human will:

Victor Hugo remercie tous les généreux donateurs prêts à sauver Notre-Dame de Paris et leur propose de faire la même chose avec Les Misérables.

— ollivier pourriol (@opourriol) April 16, 2019

Translated, that says:

Victor Hugo thanks all the generous donors ready to save Notre-Dame de Paris and proposes that they offer to do the same with Les Miserables.

May the restoration of Notre-Dame be more than just a symbol of hope and sanctuary for the downtrodden.

--James

0 notes

Photo

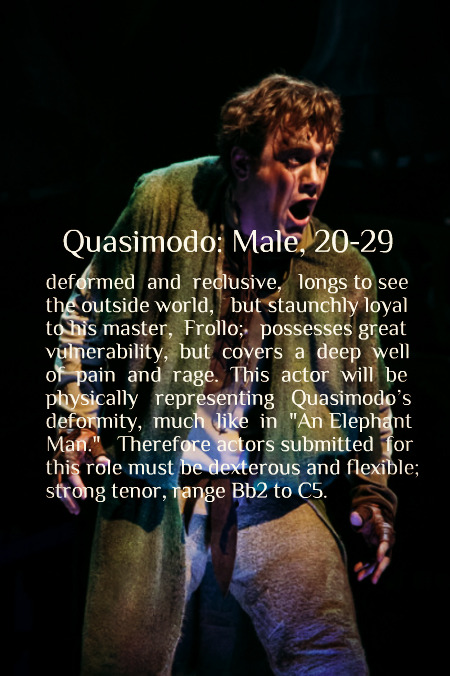

The Hunchback of Notre Dame

Official Full Synopsis (source)

Act One

A company of actors emerges, intoning a Latin chant ("Olim") with the onstage Choir. As "The Bells of Notre Dame" echo throughout the cathedral/theatre, the Congregation narrates the dawn of the Feast of Fools, a day when all – even criminals (or worse, gypsies) – are free to roam the streets of Paris without fear of reprisal. From the pulpit, Dom Claude Frollo, the most powerful cleric in Paris, warns his flock against the wickedness of the festival. In flashback, the Congregation reveals the archdeacon’s backstory. Frollo and his brother, Jehan, were taken in as orphans by the cathedral priests. Whereas Frollo thrived under the strict rules of the Church, the much wilder Jehan eventually took up with gypsies and was expelled. Many years passed, during which Frollo ascended through the ranks of the Church until he was summoned one day to his estranged brother’s deathbed. Although Jehan rejected Frollo’s offer of sanctuary, he did ask his brother to care for his gypsy baby. In grief, Frollo reluctantly agreed to do so and named the deformed child Quasimodo (“half-formed”). Frollo kept Quasimodo secluded in the cathedral bell tower for many years....

Now grown, Quasimodo is the lonely, but staunchly obedient, bell-ringer at Notre Dame. Frollo continues to offer him "Sanctuary" within the confines of the cathedral, but Quasimodo longs to be "Out There," and so he drums up the courage to defy Frollo and sneak out of the tower to attend the Feast of Fools. Down below in the square, Clopin leads the gypsies in their annual takeover of Paris ("Topsy Turvy") just as Captain Phoebus de Martin arrives from the battlefront to assume command of the Cathedral Guard. Looking forward to some "Rest and Recreation" first, Phoebus is disappointed to find himself taking his new positon early and reporting to the reproachful Frollo. Both men are instantly captivated by the arrival of the beautiful gypsy, Esmeralda, as she dances in public to the "Rhythm of the Tambourine." The frenzied crowd then joins together to crown the King of Fools ("Topsy Turvy – Part 2"). They choose Quasimodo for the mock honor, but, as Frollo predicted, the people treat him with remarkable cruelty when their celebration of his deformity turns to contempt. Hostilities rise as the mob surrounds Quasimodo, ties him up and beats him while Frollo looks on in cold silence. Esmeralda rescues Quasimodo from the abuse, enduring frustrated taunts from the crowd before she disappears in a flash of smoke amid exclamations of witchcraft. Frollo steps forward to collect a chastened Quasimodo, who promises to never again leave the tower ("Sanctuary II").

Concerned about Quasimodo’s welfare, Esmeralda ventures into the cathedral ("The Bells of Notre Dame – Reprise"), where Frollo, still overwhelmed by her beauty, offers her sanctuary and spiritual guidance. While she ponders this opportunity ("God Help the Outcasts"), Phoebus happens upon her, and they duel flirtatiously. Eventually, Esmeralda finds Quasimodo, who shows her the view from the bell tower ("Top of the World"). Frollo finds them there and confronts Esmeralda with his offer but, when she refuses, he has Phoebus escort her from the cathedral. He encourages Quasimodo to forget about the unclean gypsy.

However, Frollo cannot stop thinking about Esmeralda and roams the streets in the shadow of darkness. One night, he comes upon a tavern where the gypsies spiritedly sing and dance ("Tavern Song – Thai Mol Piyas"). Inside, a charmed Phoebus seeks out Esmeralda, and their flirtation escalates, climaxing in a kiss. The spying Frollo, enticed and horrified, runs off. Back in the bell tower, Quasimodo remains smitten by Esmeralda’s beauty and kindness ("Heaven's Light"). Meanwhile, Frollo convinces himself that Esmeralda is a demon who has been sent to tempt his very soul ("Hellfire").

The next morning, Frollo convinces King Louis XI to put out a warrant for Esmeralda’s death, and a search commences ("Esmeralda / Act I Finale"). Frollo targets a brothel that he suspects has been harboring Esmeralda. When Phoebus refuses a direct order to burn it down, Frollo has him arrested. Esmeralda appears from the crowd, and a fight breaks out. Frollo stabs Phoebus and blames Esmeralda, who escapes with the injured Phoebus. Frollo continues the hunt while Quasimodo watches the burning chaos from above.

Act Two

The Choir sings the "Entr’acte" in Latin.

In the bell tower ("Agnus Dei"), Esmeralda implores Quasimodo to hide the wounded Phoebus until he is stronger. Quasimodo agrees to help, and she offers him an amulet that will lead him to where she hides. Envisioning himself as her savior and protector ("Flight into Egypt"), Quasimodo lies to Frollo when asked if he knows where Esmeralda might be ("Esmeralda – Reprise"). Frederic interrupts to reveal that the soldiers have found the gypsy lair, and Frollo declares that they will attack at dawn. Quasimodo and the injured Phoebus use the amulet to find Esmeralda before Frollo does ("Rest and Recreation – Reprise").

Arriving at the gypsy lair, Phoebus and Quasimodo are captured by Clopin and the gypsies, who sentence them to death ("The Court of Miracles"). Esmeralda intervenes, and the two men warn of Frollo’s impending attack. As the gypsies prepare to flee, Phoebus decides to go with Esmeralda. She consents and matches his commitment to a life together while Quasimodo watches, heartbroken ("In a Place of Miracles"). Frollo barges in, sends Quasimodo back to the tower and arrests Esmeralda and Phoebus ("The Bells of Notre Dame – Reprise II").

In prison, Frollo confesses his love to Esmeralda and attacks her ("The Assault"). When Esmeralda refuses him, Frollo threatens Phoebus’ life, as well, and then has him brought into her cell so she can rethink his offer. Esmeralda and Phoebus spend their final night alive together ("Someday"). Now, bound in the tower, Quasimodo believes that he is the only one who can save Esmeralda ("While the City Slumbered"), but Frollo has made him doubt himself ("Made of Stone").

In the square the next morning, Phoebus watches from his cage as Esmeralda is tied to a wooden stake ("Judex Crederis"). Frollo again offers to save her if she will be his ("Kyrie Eleison"). Her steadfast refusal enrages him, and he lights the pyre himself. Witnessing the horror from above, Quasimodo gains courage, breaks free of his bonds and swoops down to free the badly injured Esmeralda. He then enters the cathedral with her in his arms, claims sanctuary, bars the doors and returns her to safety in his tower. Violence breaks out in the square as Phoebus and Clopin rally the crowd against Frollo. When the Cathedral Guard breaks down the church doors, Quasimodo’s last defense is to pour molten lead down on them, which ends the attack.

Quasimodo returns to Esmeralda, who declares him a good friend before she dies in his arms ("Top of the World – Reprise"). Frollo enters and tries to comfort the distraught Quasimodo ("Esmeralda – Frollo Reprise"), but he finally sees the archdeacon for the monster he is and throws him from the tower to his death ("Finale Ultimo"). Phoebus arrives, weak and broken from the battle, and collapses on Esmeralda’s body in grief. Quasimodo comforts him before picking up Esmeralda and carrying her into the square, where the Congregation has gathered to mourn.

hond musical tag & hond movie tag

#the hunchback of notre dame#hunchback of notre dame#broadway#musicals#michael arden#ciara renee#patrick page#andrew samonsky#erik liberman#hunchback disney#hunchback musical#esmeralda#quasimodo#frollo#clopin#phoebus#long post#what's a poor queue to do?

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

The Hunchback of Notre-Dame (French: Notre-Dame de Paris) is a French Gothic novel by Victor Hugo published in January 14, 1831. The title refers to the Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris, on which the story is centered. Victor Hugo began writing The Hunchback of Notre-Dame in 1829. The agreement with his original publisher, Gosselin, was that the book would be finished that same year, but Hugo was constantly delayed due to the demands of other projects. In the summer of 1830 Gosselin demanded that Hugo complete the book by February 1831. Beginning in September 1830, Hugo worked nonstop on the project thereafter. The book was finished six months later.

Synopsis

The story begins on Epiphany (6 January), 1482, the day of the Feast of Fools in Paris, France. Quasimodo, a deformed hunchback who is the bell-ringer of Notre Dame, is introduced by his crowning as the Pope of Fools. Esmeralda, a beautiful Gypsy street dancer with a kind and generous heart, captures the hearts of many men, including those of Captain Phoebus and Pierre Gringoire, a poor street poet, but especially those of Quasimodo and his adoptive father, Claude Frollo, the Archdeacon of Notre Dame. Frollo is torn between his obsessive lust and the rules of the church. He orders Quasimodo to kidnap her, but the hunchback is captured by Phoebus and his guards, who save Esmeralda. Gringoire, witnessing all this, accidentally trespasses into the Court of Miracles, home of the Truands (criminals of Paris). He was about to be hanged under the orders of Clopin Trouillefou, the King of Truands, until Esmeralda saved his life by marrying him.

The following day, Quasimodo is sentenced to be flogged and turned on the pillory for one hour, followed by another hour's public exposure. He calls for water. Esmeralda, seeing his thirst, offers him a drink. It saves him, and she captures his heart. Esmeralda is later charged with the attempted murder of Phoebus, whom Frollo actually attempted to kill in jealousy after seeing him trying to seduce Esmeralda, and is tortured and sentenced to death by hanging. As she is being led to the gallows, Quasimodo swings down by the bell rope of Notre Dame and carries her off to the cathedral under the law of sanctuary. Frollo later informs Gringoire that the Court of Parliament has voted to remove Esmeralda's right to sanctuary so she can no longer seek shelter in the church and will be taken from the church and killed. Clopin hears the news from Gringoire and rallies the Truands (criminals of Paris) to charge the cathedral and rescue Esmeralda.

When Quasimodo sees the Truands, he assumes they are there to hurt Esmeralda, so he drives them off. Likewise, he thinks the King's men want to rescue her, and tries to help them find her. She is rescued by Frollo and her phony husband Gringoire. But after yet another failed attempt to win her love, Frollo betrays Esmeralda by handing her to the troops and watches while she is being hanged. When Frollo laughs during Esmeralda's hanging, Quasimodo pushes him from the heights of Notre Dame to his death. Quasimodo then goes to the vaults under the huge Gibbet of Montfaucon, and lies next to Esmeralda's corpse, where it had been unceremoniously thrown after the execution. He stays at Montfaucon, and eventually dies of starvation. About eighteen months later, the tomb is opened, and the skeletons are found. As someone tries to separate them, Quasimodo's bones turn to dust.

Characters

Quasimodo, the novel's protagonist, is the bell-ringer of Notre Dame and a barely verbal hunchback. Ringing the church bells has made him deaf. Abandoned as a baby, he was adopted by Claude Frollo. Quasimodo's life within the confines of the cathedral and his only two outlets — ringing the bells and his love and devotion for Frollo — are described. He ventures outside the Cathedral rarely, since people despise and shun him for his appearance. The notable occasions when he does leave are his taking part in the Festival of Fools — during which he is elected the Pope of Fools due to his perfect hideousness — and his subsequent attempt to kidnap Esmeralda, his rescue of Esmeralda from the gallows, his attempt to bring Phoebus to Esmeralda, and his final abandonment of the cathedral at the end of the novel. It is revealed in the story that the baby Quasimodo was left by the Gypsies in place of Esmeralda, whom they abducted.

Esmeralda (born Agnes) is a beautiful young gypsy street dancer who is naturally compassionate and kind. She is the center of the human drama within the story. A popular focus of the citizens' attentions, she experiences their changeable attitudes, being first adored as an entertainer, then hated as a witch, before being lauded again for her dramatic rescue by Quasimodo. When the King finally decides to put her to death, he does so in the belief that the Parisian mob wants her dead. She is loved by both Quasimodo and Claude Frollo, but falls deeply in love with Captain Phoebus, a handsome soldier who she believes will rightly protect her but who simply wants to seduce her. She is the only character to show the hunchback a moment of human kindness: as he is being whipped for punishment and jeered by a horrid rabble, she approaches the public stocks and gives him a drink of water. Because of this, he falls fiercely in love with her, even though she is too disgusted by his ugliness even to let him kiss her hand.

Claude Frollo, the novel's main antagonist, is the Archdeacon of Notre Dame. His dour attitude and his alchemical experiments have alienated him from the Parisians, who believe him a sorcerer. His parents having died of plague when he was a young man, he is without family save for Quasimodo, for whom he cares, and his spoiled brother Jehan, whom he attempts to reform towards a better life. In the 1923 movie Jehan is the villain despite Frollo's numerous sins of lechery, failed alchemy and other listed vices. His mad attraction to Esmeralda sets off a chain of events, including her attempted abduction and Frollo almost murdering Phoebus in a jealous rage, leading to Esmeralda's execution. Frollo is killed when Quasimodo pushes him off the cathedral.

Jehan Frollo is Claude Frollo's over-indulged younger brother. He is a troublemaker and a student at the university. He is dependent on his brother for money, which he then proceeds to squander on alcohol. Quasimodo kills him during the attack on the cathedral. He briefly enters the cathedral by ascending one of the towers with a borrowed ladder, but Quasimodo sees him and throws him down to his death.

Phoebus de Chateaupers is the Captain of the King's Archers. After he saves Esmeralda from abduction, she becomes infatuated with him, and he is intrigued by her. Already betrothed to the beautiful but spiteful Fleur-de-Lys, he wants to lie with Esmeralda nonetheless but is prevented when Frollo stabs him. Phoebus survives but Esmeralda is taken to be the attempted assassin by all, including Phoebus himself.

Fleur-de-Lys de Gondelaurier is a beautiful and wealthy socialite engaged to Phoebus. Phoebus's attentions to Esmeralda make her insecure and jealous, and she and her friends respond by treating Esmeralda with contempt and spite. Fleur-de-Lys later neglects to inform Phoebus that Esmeralda has not been executed, which serves to deprive the pair of any further contact—though as Phoebus no longer loves Esmeralda by this time, this does not matter. The novel ends with their wedding.

Pierre Gringoire is a struggling poet. He mistakenly finds his way into the "Court of Miracles", the domain of the Truands. In order to preserve the secrecy, Gringoire must either be killed by hanging, or marry a Gypsy. Although Esmeralda does not love him, and in fact believes him a coward rather than a true man — unlike Phoebus, he failed in his attempt to rescue her from Quasimodo — she takes pity on his plight and marries him. But, because she is already in love with Phoebus, much to his disappointment, she will not let him touch her.

Sister Gudule, formerly named Paquette la Chantefleurie, is an anchoress, who lives in seclusion in an exposed cell in central Paris. She is tormented by the loss of her daughter Agnes, whom she believes to have been cannibalised by Gypsies as a baby, and devotes her life to mourning her. Her long-lost daughter turns out to be Esmeralda.

Louis XI is the King of France. Appears briefly when he is brought the news of the rioting at Notre Dame. He orders his guard to kill the rioters, and also the "witch" Esmeralda.

Tristan l'Hermite is a friend of King Louis XI. He leads the band that goes to capture Esmeralda.

Henriet Cousin is the city executioner, who hangs Esmeralda.

Florian Barbedienne is the judge who sentences Quasimodo to be tortured. He is also deaf.

Jacques Charmolue is Frollo's friend in charge of torturing prisoners. He gets Esmeralda to falsely confess to killing Phoebus. He then has her imprisoned.

Clopin Trouillefou is the King of Truands. He rallies the Court of Miracles to rescue Esmeralda from Notre Dame after the idea is suggested by Gringoire. He is eventually killed during the attack by the King's soldiers.

Pierrat Torterue is the torturer who tortures Esmeralda after her interrogation. He hurts Esmeralda so badly she falsely confesses, sealing her own fate. He was also the official who administered the savage flogging awarded to Quasimodo by Barbedienne.

Major themes

The novel's original French title, Notre-Dame de Paris (the formal title of the Cathedral) indicates that the Cathedral itself is the most significant aspect of the novel, both the main setting and the focus of the story's themes. With the notable exception of Phoebus and Esmeralda's meeting, almost every major event in the novel takes place within, atop, and around the outside of the cathedral, and also can be witnessed by a character standing within, atop, and around the outside of the cathedral. The Cathedral had fallen into disrepair at the time of writing, which Hugo wanted to point out. The book portrays the Gothic era as one of the extremes of architecture, passion, and religion. The theme of determinism (fate and destiny) is explored as well as revolution and social strife.[1]

The severe distinction of the social classes is shown by the relationships of Quasimodo and Esmeralda with higher-caste people in the book. Readers can also see a variety of modern themes emanating from the work including nuanced views on gender dynamics.[citation needed] For example, Phoebus objectifies Esmeralda as a sexual object. And, while Esmeralda is frequently cited as a paragon of purity — this is certainly how Quasimodo sees her — she is nonetheless seen to create her own objectification of the archer captain, Phoebus, that is at odds with readers' informed view of the man. In the novel, Hugo introduces one of several themes in the preface and the first story of book one, titled “The Grand Hall.” This theme is the exploration of cultural evolution and how mankind has been able to almost seamlessly transmit its ideas from one era to another through literature, architecture, and art. Hugo explores the cultural evolution not only between medieval and modern France but also the ancient worlds of Greece and Rome, and he continues to elaborate on this theme throughout the entirety of the first book.

Another important theme in the novel is that a person cannot be judged by their looks or appearance. Since Frollo is a priest, a person would normally assume him to be a kind and righteous man. In truth, he is despicably cruel, manipulative, and evil. In contrast, most people judged Quasimodo to be the devil because of his disfigured outward appearance. Inside, however, he is filled with love and kindness. Esmeralda is also misjudged; because she is a gypsy, the people of Paris believe she is evil; but like Quasimodo, she is filled with love and kindness. Phoebus is good looking and handsome, but he is vain, selfish, villainous, and untrustworthy.

Before his story begins, Hugo establishes the theme of cultural evolution in the preface of the novel. Hugo writes that he had found the word "ANANKH" chiseled into the stone, but that it was later whitewashed over or scraped away. He continues, "These Greek capitals, black with age, and quite deeply graven in the stone, with I know not what signs peculiar to Gothic calligraphy imprinted upon their forms and upon their attitudes, as though with the purpose of revealing that it had been a hand of the Middle Ages which had inscribed them there, and especially the fatal and melancholy meaning contained in them, struck the author deeply." In chapter IV it is revealed that the word means "Fate."

In the preface, it is obvious that Hugo is already recognizing the cultural similarities between ancient and modern times. Hugo states that the ideas represented in the epochs and legends of ancient Greece are so similar to the ideas of the medieval world that it almost seems as if the ancient scribes were actually written by a medieval man himself.

Hugo implies that the reason the two eras’ ideas are so similar is their transmission from one era to another through literature and the written word. In ancient Greece, epochs and legends were often inscribed on stone tablets. Since these ancient scribes have been passed down from generation to generation, they have become a very strong influence in the medieval world, a time in which ancient European works were celebrated and cherished. Also, the idea of printing literature on a medium for one to read was transmitted through both eras. However, instead of being inscribed on stone tablets, literature was printed of paper and parchment starting in the medieval era.

In this example, Hugo describes the importance of architecture and how it is an indication of a society’s values and ideals. The ornate and illustrious architecture that lies in ruins in Paris indicates the society’s dying passion for enrichment, art, and beauty. This passion is regenerated during the Renaissance, in which ancient art and lifestyles were revered. Again, Hugo gives credit to the more ancient societies for this inherent passion. Hugo states that although the original structures and buildings of ancient France may be decrepit or in ruins, it is their architectural beauty that inspired the gothic style of the medieval era. Hugo acknowledges this inspiration when he states: “The word Gothic, in the sense in which it is generally employed, is wholly unsuitable, but wholly consecrated. Hence we accept it and we adopt it, like all the rest of the world, to characterize the architecture of the second half of the Middle Ages, where the ogive is the principle which succeeds the architecture of the first period, of which the semi-circle is the father.”

The theme of Book One of The Hunchback of Notre Dame was cultural evolution. Hugo wants to show how people of the world can show their ideals and those from earlier eras through literature and technology. Hugo continues to strengthen the idea of cultural evolution between eras of time. Hugo argues that there is another way in which ideas are passed on between different cultures and eras, and it is through architecture or literature. In Chapter One of Book One, Hugo continues to strengthen the idea of cultural evolution between eras of time. Hugo argues that there is another way in which ideas are transmitted between different cultures and eras, and it is through architecture. Setting and architecture are very prominent in The Hunchback of Notre Dame, and Hugo often goes into great detail describing the buildings and monuments of medieval Paris. Hugo relates these structures and their architectures back to their gothic roots, which date back to ancient times. In one lengthy description, Hugo states: “...very little remains of that first dwelling of the kings of France...What has time, what have men done with these marvels?

What have they given us in return for all this Gallic history, for all this Gothic art? The heavy flattened arches of M. de Brosse, that awkward architect of the Saint-Gervais portal. So much for art; and, as for history, we have the gossiping reminiscences of the great pillar, still ringing with the tattle of the Patru.” Throughout the entirety of the Book One, Hugo puts great emphasis on the transmission of ideas from one era to another through literature, architecture, and art. Hugo had a passion for the Gothic architecture of medieval France and therefore he establishes an emotionally nostalgic tone toward Gothic art that is apparent throughout the novel.

In Book Two of The Hunchback of Notre Dame, Hugo spotlights many forms of loyalty. Quasimodo displays incredible devotion to the priest in Chapter Three; he “remain[s] on his knees, with head bent and hands clasped” in front of the priest. In Chapter Four, the police squad represents allegiance to the king when its members make their rounds in the streets of Paris. During these patrols, they surround Quasimodo and rescue the gypsy who had become his prey. The gypsy’s goat is also a symbol of loyalty. It continues to follow her steadfastly, even when Quasimodo has her captive and when the gypsy flees from the squad. The three knaves take Gringoire to their ‘king,’ a beggar to whom they remain unbelievably subservient.

Esmeralda shows commitment to mankind when she marries Gringoire for the sole purpose of saving his life; even though she does not love him, she wants him to survive. Gringoire is so dedicated to poetry and philosophy that the very mention of “perhaps” or a mysterious notion is enough to give him a surge of courage or curiosity, respectively. Pierre Gringoire the poet gives Dom Claude Frollo credit for all of his intelligence and success and stays loyal to Frollo by making verbal tribute to him when he says, “It is to him that I to-day owe it that I am a veritable man of letters.” Loyalty is a crucial topic in Hugo’s second book within The Hunchback of Notre Dame and its existence and importance are represented in a variety of ways.

In Book Three, Chapter One has the theme of change from time. Book Three focuses on the Cathedral Church of Paris, and its appearance as time has worn it. The narrator describes the cathedral as a place once of beauty, now crumbling as time has passed. Stained-glass windows have been replaced with “cold, white panes” and it becomes clear that the narrator looks on the changes of the church sourly (Hugo). Improvements and modifications of the great cathedral have in a sense lessened its internal value. Staircases have been buried under the soil of the bustling city, and statues have been removed. The passing time brought immense change to the church, often in negative ways. Eras have scarred this church in ways that cannot be healed. The narrator describes, “Fashions have wrought more harm than revolutions,” (Hugo). The modifications and alterations to the cathedral are an unfortunate mark of change in time; the main theme of Book Three.

A theme that occurs in the Book Four of The Hunchback of Notre Dame is love. Love can exist in many forms. Love between mother and child, love between one and his hobby, and love between one and an object are relationships that are all present in the Hunchback of Notre Dame. Claude Frollo is the priest of Notre Dame. Growing up, he was a very intelligent boy. He was fascinated by science and medicine. He had a love of learning; it was his passion. Later in the story he even turns to science and studying when he feels his life is going downhill. Learning was Frollo’s love until the day his parents died, and he adopted his baby brother, Jehan. Then he realized “that a little brother to love sufficed to fill an entire existence.” Frollo put all of his focus into caring for Jehan, and he loved him unconditionally. He also adopted another child later named Quasimodo, for the very reason that “if he were to die, his dear little Jehan might also be flung miserably on the plank for foundlings,--all this had gone to his heart simultaneously; a great pity had moved in him, and he had carried off the child.” Although the child was hideous and no one else wanted him, Frollo promised to care for him and love him always, as he did with his brother. Quasimodo’s ugliness only strengthened Frollo’s love for him. When the foundling grew up, he was given the position of bell ringer by his master, Frollo. “He loved them [the bells], fondled them, talked to them, understood them.” Quasimodo loved his bells; his most beloved bell was named Marie (the largest one). Quasimodo also loved his father, Frollo. After all, he “had taken him in, had adopted him, had nourished him, had reared him…had finally made him the bellringer.” Even when Frollo was unkind to Quasimodo, he still loved him very much. In Book 4, a love between father and son is seen. Frollo loved both of his adopted “babies” very much, and everyone had objects and hobbies that they loved dearly too; Frollo loved to learn, and Quasimodo loved his cathedral bells.

The theme of Chapters One and Two of Book Five is that the new technologies being created during this time period were going to destroy the knowledge of the past, and hide it forever from the generations to come. France, at the time Hugo was writing this piece, was in a time of rebuilding after the French Revolution. The people began to split into two different parts; one was for the republic of France and the other was against. Many changes were occurring during this time, and people were unsure of where to fall. "The book will kill the edifice," is a quote Hugo bases much of this chapter on. "The press will kill the church." The quote in full means that the printing press, a new invention, will overpower the church. In Hugo's writing he says, "In the first place, it was a priestly thought. It was the affright of the priest in the presence of a new agent, the printing press. It was the terror and dazzled amazement of the men of the sanctuary, in the presence of the luminous press of Gutenberg." The church was afraid that once the printing press was in full swing the people of France would no longer come and listen to the priests, but rely on the paper.