#what if we acknowledge and represent the people who ALSO made up early america and directly influenced it to such a degree that we can

Text

And if I said I don’t give a fuck about the Puritans in relation to Nyo + Canon America…..?

#like pls its such a snorefest to write#ITS THE SAAAAAAME FKN THING LIKE OK YES FINE BORING LIFE NOT ALLOWED TO DO ANYTHING SCARED OF GOD FINE#but what if…… we DIDNT pretend that colonial america had only one group of people.?#what if we acknowledge and represent the people who ALSO made up early america and directly influenced it to such a degree that we can#still see it today…..#i love virginian america theyre my cutey pie#but pls#middle colonies#quakers#catholics#ANYONE BUT THE PURITANS PLEASE

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Trump’s Covid: Empathy for the World’s Least Empathetic Person?

For about a minute today I found myself feeling sorry for Donald Trump. The poor man is now “battling” Covid-19 (the pugilistic verb is showing up all over the news). He’s in the hospital. He’s out-of-shape. He’s 74-years old. His chief of staff calls his symptoms “very concerning.”

Joe Biden is praying for him. Kamala Harris sends him heartfelt wishes. President Obama reminds us we’re all in this together and we want to make sure everyone is healthy.

But hold on: Why should we feel empathy for one of the world’s least empathetic people?

Out of respect. He’s a human being. And he’s our president.

Yet there’s an asymmetry here. While the Biden campaign has taken down all negative television advertising, the Trump campaign’s negative ads continue non-stop.

And at almost the same time that Biden, Harris, and Obama offered prayers and consoling words, the Trump campaign blasted “Lyin’ Obama and Phony Kamala Harris” and charged that “Sleepy Joe isn’t fit to be YOUR President.”

Can you imagine if Biden had contracted Covid rather than Trump? Trump would be all over him. He’d attack Biden as weak, feeble, and old. He’d mock Biden’s mask-wearing – “See, masks don’t work!” – and lampoon his unwillingness to hold live rallies: “Guess he got Covid in his basement!”

How can we even be sure Trump has the disease? He’s lied about everything else. Maybe he’ll reappear in a day or two, refreshed and relaxed, saying “Covid is no big deal.” He’ll claim he took hydroxychloroquine, and it cured him. He’ll boast that he won the “battle” with Covid because he’s strong and powerful.

Meanwhile, his “battle” has distracted the nation from revelations that he’s a tax cheat who paid only $750 in taxes his first year in office, and barely anything for fifteen years before that; and that he’s a failed businessman who’s still losing money.

And from his vicious, cringeworthy debate performance last week, in which he didn’t want to condemn white supremacists.

It even takes our mind off the major reason Covid is out of control in America: because Trump blew it.

He downplayed it, pushed responsibility onto governors, and then demanded they allow businesses to reopen – too early -- in order to make the economy look good before the election.

He has muzzled and disputed experts at the CDC, promoted crank cures, held maskless campaign events, and encouraged followers not to wear masks. All of this has contributed to tens of thousands of unnecessary American deaths.

Trump’s “battle” with Covid also diverts attention from his and Mitch McConnell’s perversions of American democracy.

This is where the asymmetry runs deeper. McConnell is now moving to confirm Trump’s Supreme Court nominee Amy Coney Barrett, after having prevented Obama’s nominee from getting a Senate vote for almost a year on the basis of a concocted “rule” that the next president should decide.

Yet Biden won’t talk about increasing the size of the court in order to balance it, and Democratic leaders have shot down the idea.

Nor do Biden and top Democrats want to suggest making Washington, D.C. and Puerto Rico into states -- a step that would remedy the bizarre inequities in the Senate where a bare majority of Republicans representing 11 million fewer Americans than their Democratic counterparts are able to confirm a Supreme Court justice.

It would also help rebalance the Electoral College, which made Trump president in 2016 despite losing the popular vote by more than 3 million.

Democrats worry this would strike the public as unfair.

Unfair, when Trump won’t even commit to a peaceful transition of power and refuses to be bound by the results?

When he’s already claiming the election is rigged against him and will be fraudulent unless he wins?

When he’s now readying slates of Trump electors to be certified in states he’ll allege he lost because of fraud? When he’s urging his followers to intimidate Biden voters at the polls?

Whether responding to Trump’s hospitalization this weekend or to Trump’s larger political maneuvers, Democrats want to act decently and fairly. They want to protect democratic norms, values, and institutions.

This is admirable. It’s also what Democrats say they stand for.

But the other side isn’t playing the same game. Trump and his enablers will do anything to retain and enlarge their power.

It’s possible to be sympathetic toward Trump during his “battle” with Covid-19 while acknowledging that he is subjecting America to a profound moral test in the weeks and perhaps months ahead.

What kind of society do we want: one based on decency and democracy, or on viciousness and raw power?

219 notes

·

View notes

Text

La Fayette - an American Citizen?

As promised, @msrandonstuff :-)

The question weather La Fayette was an American citizen had for quite a time been the subject of debates - both during La Fayette’s lifetime as well as long after his death. Not only La Fayette’s own status was up for debate but also the legal status of his descendants.

We start off with the fairly simple, La Fayette had been made an honorary American citizen on August 06, 2002 (that is the date where President George W. Bush signed the resolution, the bill however had been first introduced on April 24, 2001, you can find the timeline of the bill here.)

The Congress of the United States has a very detailed (and research-friendly) free online archive. You can read the wording of the original bill here and here you can see the amendments that were made. The speeches and procedures that accompany the bill the day it was passed in the House of Representatives are to be found here.

Here is the text of the resolution for everybody who has no interest or time to go through my jungle of links :-)

Joint Resolution

Conferring honorary citizenship of the United States posthumously on Marie Joseph Paul Yves Roche Gilbert du Motier, the Marquis de Lafayette.

Whereas the United States has conferred honorary citizenship on four other occasions in more than 200 years of its independence, and honorary citizenship is and should remain an extraordinary honor not lightly conferred nor frequently granted;

Whereas Marie Joseph Paul Yves Roche Gilbert du Motier, the Marquis de Lafayette or General Lafayette, voluntarily put forth his own money and risked his life for the freedom of Americans;

Whereas the Marquis de Lafayette, by an Act of Congress, was voted to the rank of Major General;

Whereas, during the Revolutionary War, General Lafayette was wounded at the Battle of Brandywine, demonstrating bravery that forever endeared him to the American soldiers;

Whereas the Marquis de Lafayette secured the help of France to aid the United States' colonists against Great Britain;

Whereas the Marquis de Lafayette was conferred the honor of honorary citizenship by the Commonwealth of Virginia and the State of Maryland;

Whereas the Marquis de Lafayette was the first foreign dignitary to address Congress, an honor which was accorded to him upon his return to the United States in 1824;

Whereas, upon his death, both the House of Representatives and the Senate draped their chambers in black as a demonstration of respect and gratitude for his contribution to the independence of the United States;

Whereas an American flag has flown over his grave in France since his death and has not been removed, even while France was occupied by Nazi Germany during World War II; and

Whereas the Marquis de Lafayette gave aid to the United States in her time of need and is forever a symbol of freedom: Now, therefore, be it

Resolved by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That Marie Joseph Paul Yves Roche Gilbert du Motier, the Marquis de Lafayette, is proclaimed posthumously to be an honorary citizen of the United States of America.

Now, this honorary citizenship does only involve La Fayette himself. His heirs have nothing to do with this act. It does however acknowledge that La Fayette had already been made a citizen by the state of Maryland and the Commonwealth of Virginia (they left out the, somewhat questionable, declarations by the State of Connecticut and the State of Massachusetts.) Let us therefor go back to the 18th century and have a look at both of these resolutions. First is Maryland:

The General Assembly of the state of Maryland passed the following resolution on December 28, 1784.

CHAP. XII.

An ACT to naturalize major-general the marquis de la Fayette and his heirs male for ever.

WHEREAS the general assembly of Maryland, anxious to perpetuate a name dear to the state, and to recognize the marquis de la Fayette for one of its citizens, who, at the age of nineteen, left his native country, and risked his life in the late revolution; who, on his joining the American army, after being appointed by congress to the rank of major-general, disinterestedly refused the usual rewards of command, and sought only to deserve what he attained, the character of patriot and soldier; who, when appointed to conduct an incursion into Canada, called forth by his prudence and extraordinary discretion the approbation of congress; who, at the head of an army in Virginia, baffled the manœuvres of a distinguished general, and excited the admiration of the oldest commanders; who early attracted the notice and obtained the friendship of the illustrious general Washington; and who laboured and succeeded in raising the honour and the name of the United States of America: Therefore,

II. Be it enacted, by the general assembly of Maryland, That the marquis de la Fayette, and his heirs male for ever, shall be, and they and each of them are hereby deemed, adjudged, and taken to be, natural born citizens of this state, and shall henceforth be entitled to all the immunities, rights and privileges, of natural born citizens thereof, they and every of them conforming to the constitution and laws of this state, in the enjoyment and exercise of such immunities, rights and privileges.

Interesting piece of legislature, we are now not only talking about La Fayette but also about “his male heirs forever” - keep that in mind for later. On to Virginia:

The Journal of the House of Delegates of the Commonwealth of Virginia, yr. 1781-1786 states for Thursday, December 16, 1784:

Ordered, That leave be given to bring in a bill “for the naturalisation of the Marquis De la Fayette;” and that Messr. Henry Lee, and Turberville, do prepare and bring in the same.

We can read for Monday, October 31, 1785:

Mr. Henry Lee presented, according to order, a bill, “for the naturalisation of the Marquis De la Fayette;” and the same was received and read a first time, and ordered to be read a second time.

We can further read on that day that:

A bill, "for the naturalization of the Marquis de la Fayette;" was read the second time, and ordered to be com- mitted to a committee of the whole House immediately. The House, accordingly, resolved itself into a committee of the whole House, on the said bill ; and after some time spent therein, Mr. Speaker resumed the chair, and Mr. Braxton reported, that the committee had, according to order, had the said bill under their consideration, and had gone through the same, and made several amendments thereto, which he read in his place, and afterwards delivered in at the clerk's table, where the same were again twice read, and agreed to by the House.

The next day, on Tuesday, November 1, 1785, we can read in the Journal:

An engrossed bill. “for the naturalization of the Marquis de la Fayette;" was read the third time.

Resolved, That the bill do pass; and that the title be, "an act, for the naturalization of the Marquis de la Fayette.'”

Ordered, That Mr. Henry Lee do carry the bill to the Senate, and desire their concurrence.

On Friday, November 11, 1785 we can read:

A message from the Senate by Mr. Harrison

Mr. Speaker, — The Senate have agreed to the bill (…) “for the naturalization of the Marquis de la Fayette;" (…) And then he withdrew

And finally on Saturday, January 7, 1786 we can read:

The Speaker signed the following enrolled bills: (…) “An act, for the naturalization of the Marquis de la Fayette."

At this point now we have two citizenships, one of them including his male heirs - so why was there any need for the honorary citizenship of 2002? I let Mr. Sensenbrenner, from the Committee on the Judiciary, who also submitted the amendments to the 2002 bill, explain it:

The Marquis de Lafayette was granted citizenship by the States of Maryland and Virginia before the Constitution was adopted. In 1935, a State Department letter addressed the question of whether the citizenship conferred by these States could be interpreted to have ultimately resulted in the Marquis de Lafayette being a United States citizen. Their determination was that it did not. The State Department provided an excerpt from the Journals of the Continental Congress in 1784 which stated in the Congress' farewell to the Marquis that ``as his uniform and unceasing attachment to this country has resembled that of a patriotic citizen of the United States . . . [emphasis added]'' as proof that the citizenship was not considered to have translated to a Federal level.

Simply speaking, a “state citizenship” does not equal a “real American citizenship”. Nevertheless, two decadents of La Fayette tried to obtain an American citizenship by using the Maryland resolution. Count René de Chambrun in 1932 and Count Edward Perrone di San Martino a few years later – I think the years was 1935 and he was the reason the State Department wrote their letter. As you all can very well imagine, both men were denied. Beside the rather obvious reason for their denial, the descendants were faced with even more legal obstacles. They had to rely solely on the Maryland resolution. That resolution was passed in 1784 under the Articles of Confederation. This set of laws was replaced on March 4, 1789 by the United States Constitution. Some people argue that La Fayette and all his male heirs born up until March 4, 1784 were made US citizens by the Maryland resolution but new citizenships could not be granted to any male heirs born after the Constitution became effective, because the Maryland resolution was passed under the Articles of Confederation and not under the Constitution. Some people argue however, that the Constitution still provides the same legal margin for a citizenships according to the Maryland resolution.

It furthermore has to be taken into consideration, that the term “and his heirs male forever” generally implies that there has to be an uninterrupted line of male decadents and heirs. From father to son to grand-son, great-grandson and so on and so forth. The problem is, that the male line of the La Fayette’s died out quite some time ago. La Fayette himself had one son, Georges Washington Louis Gilbert de La Fayette. He in turn had two sons of his own. Oscar Gilbert Lafayette and Edmond de La Fayette. None of them had any surviving male children of their own.

But these two incidents were not the only times that trouble and uncertainty arose from the States grant of citizenship - far from it. When La Fayette was arrested during the French Revolution by the Austrian troops, he tried to avoid imprisonment by declaring himself an American citizen. Neither the Austrians nor the Prussians bought into that and the Americans were also a bit uneasy about La Fayette’s claim. Later, when Adrienne send her son Georges Washington de La Fayette over to America, she wrote a very “subtle” letter, reminding the American people that her son was included in the resolution from Maryland. Meanwhile, James Monroe, the American ambassador to France at the time, had obtained passports for Adrienne and her two daughters to travel to America as well. The papers were for “Mrs. Motier of Hartford, Connecticut”. Here is the catch; the town of Hartford in Connecticut (not the state itself, only that single town) had declared La Fayette and his entire family as citizen. The passports were made on a very shaky legal ground and Monroe was fully aware of that - but he simple did not care, nor did anybody else. They wanted to help the family and if questionable passports were the way to go, so be it.

So there you have it. La Fayette was made a citizen of the United States only once, but he was made twice the citizen of different States.

#lafayette#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#general lafayette#historical lafayette#france#america#2002#1782#1785#1786#1824#1789#american revolution#american history#french history#history#house of representatives#united states senate#congress#george w bush#honorary citizenship#legal#articles of confederation#united states constitution#georges washington de lafayette#oscar gilbert de lafayette#edmond de la fayette#maryland#virginia

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 4 – It is always 1895 [TAB 1/1]

TAB is my favourite episode of Sherlock. It is a masterpiece that investigates queerness, the canon and the psyche all within an hour and a half. Huge amounts of work has been done on this episode, however, so I’m not going to do a line by line breakdown – that could fill a small book. A great starting point for understanding the myriad of references in TAB is Rebekah’s three part video series on the episode, of which the first instalment can be found here X. I broadly agree with this analysis; what I’m going to do here, though, is place that analysis within the framework of EMP theory. As a result, as much as it pains me, this chapter won’t give a breakdown of carnation wallpaper or glass houses or any of those quietly woven references – we’re simply going in to how it plays into EMP theory.

Before digging into the episode, I want to take a brief diversion to talk about one of my favourite films, Mulholland Drive (2001).

If you haven’t seen Mulholland Drive, I really recommend it – it’s often cited as the best film of the last 20 years, and watching it really helps to see where TAB came from and the genre it’s operating in. David Lynch is one of the only directors to do the dream-exploration-of-the-psyche well, and I maintain that a lot of the fuckiness in the fourth series draws on Lynch. However, what I actually want to point out about Mulholland Drive is the structure of it, because I think it will help us understand TAB a little better. [If you don’t want spoilers for Mulholland Drive, skip the next paragraph.]

The similarities between these two are pretty straightforward; the most common reading of Mulholland Drive is that an actress commits suicide by overdose after causing the death of her ex-girlfriend, who has left her for a man, and that the first two-thirds of the film are her dream of an alternate scenario in which her girlfriend is saved. The last third of the film zooms in and out of ‘real life’, but at the end we see a surreal version of the actual overdose which suggests that this ‘real life’, too, has just been in her psyche. Sherlock dying and recognising that this may kill John is an integral part of TAB, and the relationships have clear parallels, but what is most interesting here is the structural similarity; two-thirds of the way through TAB, give or take, we have the jolt into reality, zoom in and out of it for a while and then have a fucky scene to finish with that suggests that everything is, in fact, still in our dying protagonist’s brain. Mulholland Drive’s ending is a lot sadder than TAB’s – the fact that, unlike Sherlock, there is no sequel can lead us to assume that Diane dies – and it’s also a lot more confusing; it’s often cited as one of the most complicated films ever made even just in terms of surface level plot, before getting into anything else, and it certainly took me a huge amount of time on Google before I could approach anything like a resolution on it!

Mulholland Drive is the defining film in terms of the navigating-the-surreal-psyche subgenre, and so the structural parallels between the two are significant – and definitely point to the idea that Sherlock hasn’t woken up at the end of TAB, which is important. But we don’t need to take this parallel as evidence; there’s plenty of that in the episode itself. Let’s jump in.

Emelia as Eurus

When we first meet Eurus in TST, she calls herself E; this initialism is a link to Moriarty, but it’s also a convenient link to other ‘E’ names. Lots of people have already commented on the aural echo of ‘Eros’ in ‘Eurus’, which is undeniable; the idea that there is something sexual hidden inside her name chimes beautifully with her representation of a sexual repression. The other important character to begin with E, however, is Emelia Ricoletti. The name ‘Emelia’ doesn’t come from ACD canon, and it’s an unorthodox spelling (Amelia would be far more common), suggesting that starting with an ‘E’ is a considered choice.

When TAB aired, we were preoccupied with Emelia as a Sherlock mirror, and it’s easy to see why; the visual parallels (curly black hair, pale skin) plus the parallel faked death down to the replacement body, which Mofftiss explicitly acknowledge in the episode. However, I don’t think that this reading is complete; rather, she foreshadows the Eurus that we meet in s4. The theme of ghosts links TAB with s4 very cleanly; TAB is about Emelia, but there is also a suggestion of the ghosts of one’s past with Sir Eustace as well as Sherlock’s own claims (‘the shadows that define our every sunny day’). Compare this to s4 – ‘ghosts from the past’ appears on pretty much every promotional blurb, and the word is used several times in relation to Eurus. If Eurus is the ghost from Sherlock’s past, the repressive part of his psyche that keeps popping back, Emelia is a lovely metaphor for this; she is quite literally the ghost version of Sherlock who won’t die.

What does it mean, then, when Jim and Emelia become one and the same in the scene where Jim wears the bride’s dress? We initially read this as Jim being the foil to Sherlock, his dark side, but I think it’s more complicated than this. Sherlock’s brain is using Emelia as a means of understanding Jim, but when we watch the episode it seems that they’ve actually merged. Jim wearing the veil of the bride is a good example of this, but I also invite you to rewatch the moment when John is spooked by the bride the night that Eustace dies; the do not forget me song has an undeniable South Dublin accent.* This is quite possibly Yasmine Akram [Janine] rather than Andrew Scott, of course, but let’s not forget that these characters are resolutely similar, and hearing Jim’s accent in a genderless whisper is a pretty clear way of inflecting him into the image of the bride. In addition to this, Eustace then has ‘Miss Me?’ written on his corpse, cementing the link to Moriarty.

[*the South Dublin accent is my accent, so although we hear a half-whispered song for all of five seconds, I’m pretty certain about this]

Jim’s merging with Emelia calls to mind for me what I think might be the most important visual of all of series 4 – Eurus and Jim’s Christmas meeting, where they dance in circles with the glass between them and seem to merge into each other. I do talk about this in a later chapter, but TLDR – if Jim represents John being in danger and Eurus represents decades of repressed gay trauma, this merging is what draws the trauma to the surface just as Jim’s help is what suddenly makes Eurus a problem. It is John’s being in danger which makes Sherlock’s trauma suddenly spike and rise – he has to confront this for the first time – just like Emelia Ricoletti’s case from 1895 only needs solving for the first time now that Jim is back.

At some point I want to do a drag in Sherlock meta, because I think there’s a lot more to it than meets the eye, but Jim in a bride’s dress does draw one obvious drag parallel for me.

If you haven’t seen the music video for I Want to Break Free, it’s 3 minutes long and glorious – and also, I think, reaps dividends when seen in terms of Sherlock. You can watch it here: X

Not only is it a great video, but for British people of Mofftiss’s age, it’s culturally iconic and not something that would be forgotten when choosing that song for Jim. Queen were intending to lampoon Coronation Street, a British soap, and already on the wrong side of America for Freddie Mercury’s unapologetic queerness, found themselves under fire from the American censors. Brian May says that no matter how many times he tried to explain Coronation Street to the Americans, they just didn’t get it. This was huge controversy at the time, but the video and the controversy around it also managed to cement I Want to Break Free as Queen’s most iconic queer number – despite not even being one of Mercury’s songs. There is no way that Steven Moffat, and even more so Mark Gatiss would not have an awareness of this in choosing this song for Moriarty. Applying any visual to this song is going to invite comparisons to the video – and inflecting a sense of drag here is far from inappropriate. Moriarty has been subsumed into Eurus in Sherlock’s brain – the male and the female are fused into an androgynous and implicitly therefore all-encompassing being. I’m not necessarily comfortable with the gendered aspect of this – genderbending is something we really only see in our villains here – but given this is about queer trauma, deliberately queering its form in this way is making what we’re seeing much more explicit.

Nothing new under the sun

“The thing that hath been, it is that which shall be; and that which is done is that which shall be done: and there is no new thing under the sun” (Ecclesiastes)

"Read it up -- you really should. There is nothing new under the sun. It has all been done before." (A Study in Scarlet, Sherlock Holmes)

“Hasn’t this all happened before? There’s nothing new under the sun.” (The Abominable Bride, Jim Moriarty)

This is arguably the key to spotting that TAB is a dream long before they tell us – when TAB’s case is early revealed to be a mixture between TRF (Emelia’s suicide) and TGG (the five pips), and we see the opening of ASiP repeated, we should be questioning what on earth is going on. This can also help us to recognise s4 as being EMP as well though – old motifs from the previous series keep repeating through the cases, like alarm bells ringing. Moriarty telling Sherlock that there is nothing new under the sun is his key to understanding that the Emelia case is meant to help him understand what happened to Jim, that it’s a mental allegory or mirror to help him parse it. This doesn’t go away when TAB ends! Moving into TST, one of the striking things is that cases are still repeating! The Six Thatchers appeared on John’s blog way back, before the fall – you can read it here: X. It’s about a gay love affair that ends in one participant killing the other. Take from that what you will, when John’s extramarital affection is making him suicidal and Sherlock comatose. Meanwhile, the title of The Final Problem refers to the story that was already covered in TRF and the phone situation with the girl on the plane references both ASiB and TGG, and the ending of TST is close to a rerun of HLV. It’s pretty much impossible to escape echoes of previous series in a way that is almost creepy, but we’ve already had this explained to us in TAB – none of this is real. It’s supposed to be explaining what is happening in the real world – and Mofftiss realised that this was going to be difficult to stomach, and so they included TAB as a kind of key to the rest of the EMP, which becomes much more complex.

However, if we want to go deeper we should look at where that quote comes from. I’ve given a few epigraphs to this section to show where the quote comes from – first the book of Ecclesiastes, then A Study in Scarlet. It’s one of the first things Holmes says and it is during his first deduction in Lauriston Gardens. This is where I’m going to dive pretty deep into the metatextual side of things, so bear with the weirdness.

[we’re going deeper]

Holmes’s first deduction from A Study in Scarlet shows that he’s no great innovator – he simply notices things and spots patterns from things he has seen before. This is highlighted by the fact that he even makes this claim by quoting someone before him. If our Sherlock also makes deductions based on patterns from the past, extensive dream sequences where he works through past cases as mirrors for present ones makes perfect sense and draws very cleverly on canon. However, I think his spotting of patterns goes deeper than that. Sherlock Holmes has been repressed since the publication of A Study in Scarlet, through countless adaptations in literature and film. Plenty of these adaptations as well as the original stories are referenced in the EMP, not least by going back to 1895, the year that symbolises the era in which most of these adaptations are set. (If you don’t already know it, check out the poem 221B by Vincent Starrett, one of the myriad of reasons why the year 1895 is so significant.) My feeling is that these adaptations, which have layered on top of each other in the public consciousness to cement the image of Sherlock Holmes the deductive machine [which he’s not, sorry Conan Doyle estate] come to symbolise the 100+ years of repression that Sherlock himself has to fight through to come out of the EMP as his queer self.

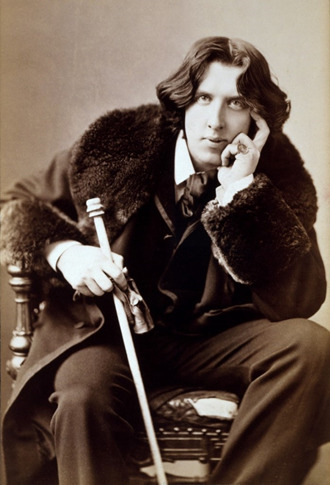

This is one of the reasons that the year 1895 is so important; it was the year of Oscar Wilde’s trial and imprisonment for gross indecency, and this is clearly a preoccupation of Sherlock’s consciousness in TFP with its constant Wilde references, suggesting that his MP’s choice of 1895 wasn’t coincidental. Much was made during TAB setlock of a newspaper that said ‘Heimish The Ideal Husband’, Hamish being John’s middle name and An Ideal Husband being one of Wilde’s plays. But the Vincent Starrett poem, although nostalgic and ostensibly lovely, for tjlcers and it seems for Sherlock himself symbolises something much more troubling. Do search up the full poem, but for now let’s look at the final couplet.

Here, though the world explode, these two survive

And it is always 1895

‘Though the world explode’ is a reference to WW1, which is coming in the final Sherlock Holmes story, and which is symbolised by Eurus – in other chapters, I explain why Eurus and WW1 are united under the concept of ‘winds of change’ in this show. Sherlock and John survive the winds of change – except they don’t move with them. Instead, they stay stuck in 1895, the year of ultimate repression. 2014!Sherlock going back in his head to 1895 and repeating how he met John suggests exactly that, that nothing has changed but the superficial, and that emotionally, he is still stuck in 1895.

Others have pulled out similar references to Holmes adaptations he has to push through in TAB – look at the way he talks in sign language to Wilder, which can only be a reference to Billy Wilder, director of TPLoSH, the only queer Holmes film, and a film which was forced to speak through coding because of the Conan Doyle estate. That film is also referenced by Eurus giving Sherlock a Stradivarius, which is a gift given to him in TPLoSH in exchange for feigning heterosexuality. Eurus is coded as Sherlock’s repression, and citing a repressive moment in a queer film as her first action when she meets Sherlock is another engagement by Sherlock’s psyche with his own cinematic history. My favourite metatextual moment of this nature, however, is the final scene of TFP which sees John and Sherlock running out of a building called Rathbone Place.

Basil Rathbone is one of the most iconic Sherlock Holmes actors on film, and Benedict’s costume in TAB and in particular the big overcoat look are very reminiscent of Rathbone.

Others have discussed (X) how the Victorian costume and the continued use of the deerstalker in the present day are images of Sherlock’s public façade and exclusion of queerness from his identity. It’s true that pretty much every Holmes adaptation has used the deerstalker, but the strong Rathbone vibes that come from Ben’s TAB costume ties the 1895 vibe very strongly into Rathbone. To have the final scene – and hopefully exit from the EMP – tie in with Sherlock and John running out of Rathbone Place tells us that, just as Sherlock cast off the deerstalker at the end of TAB (!), he has also cast off the iconic filmic Holmes persona which has never been true to his actual identity.

Waterfall scene

The symbol of water runs through TAB as well as s4 – others have written fantastic meta on why water represents Sherlock’s subconscious (X), but I want to give a brief outline. It first appears with the word ‘deeper’ which keeps reappearing, which then reaches a climax in the waterfall scene. The idea that Sherlock could drown in the waters of his mind is something that Moriarty explicitly references, suggesting that Sherlock could be ‘buried in his own Mind Palace’. The ‘deep waters’ line keeps repeating through series 4, and I just want to give the notorious promo photo from s4 which confirms the significance of the motif.

This is purely symbolic – it never happens in the show. Water increases in significance throughout – think of Sherlock thinking he’s going mad in his mind as he is suspended over the Thames, or the utterly nonsensical placement of Sherrinford in the middle of the ocean – the deepest waters of Sherlock’s mind. Much like the repetition of cases hinting that EMP continues, the use of water is something that appears in the MP, and it sticks around from TAB onwards, a real sign that we’re going deeper and deeper. I talk about this more in the bit on TFP, but the good news is that Sherrinford is the most remote place they could find in the ocean – that’s the deepest we’re going. After that, we’re coming out (of the mind).

Shortly after TAB aired, I wrote a meta about the waterfall scene, some of which I now disagree with, but the core framework still stands – it did not, of course, bank on EMP theory. You can find it here (X), but I want to reiterate the basic framework, because it still makes a lot of sense. Jim represents the fear of John’s suicide, and Jim can only be defeated by Sherlock and John together, not one alone – and crucially, calling each other by first names, which would have been very intimate in the Victorian era. After Jim is “killed”, we have Sherlock’s fall. The concept of a fall (as in IOU a fall) has long been linked with falling in love in tjlc. Sherlock tells John that it’s not the fall that kills you, it’s the landing, something that Jim has been suggesting to him for a while. What is the landing, then? Well, Sherlock Holmes fell in love back in the Victorian era, symbolised by the ultra repressive 1895, and that’s where he jumps from – but he lands in the 21st century. Falling in love won’t kill him in the modern day. What I missed that time around, of course, was that despite breaking through the initial Victorian layers of repression, he still dives into more water, and when the plane lands, it still lands in his MP, just in a mental state where the punishment his psyche deals him for homosexuality is less severe. This also sets up s4 as specifically dealing with the problem of the fall – Sherlock jumps to the 21st century specifically to deal with the consequences of his romantic and sexual feelings. There’s a parallel here with Mofftiss time jumping; back when they made A Study in Twink in 2009, there was a reason they made the time jump. Having Sherlock’s psyche have that touch of self-awareness helps to illustrate why they made a similar jump, also dealing with the weight of previous adaptations.

Women

I preface this by saying how incredibly uncomfortable I find the positioning of women as the KKK in TAB. It’s a parallel which is unforgivable; frankly, invoking the KKK without interrogating the whiteness of the show or even mentioning race is unacceptable. Steven Moffat’s ability to write women has consistently been proven to be nil, but this is a new low. However, the presence of women in TAB is vital, so on we go.

TAB specifically deals with the question of those excluded from a Victorian narrative. This is specifically tied into to those who are excluded from the stories, such as Jane and Mrs. Hudson. Mrs. Hudson’s complaint is in the same scene as John telling her and Sherlock to blame the problems on the illustrator. This ties back to the deerstalker metaphor which is so prevalent in this episode; something that’s not in the stories at all, but a façade by which Holmes is universally recognised and which as previously referenced masks his queerness. Women, then, are not the only people being excluded from the narrative. When Mycroft tells us that the women have to win, he’s also talking about queer people. This is a war that we must lose.

I don’t think the importance of Molly in particular here has been mentioned before, but forgive me if I’m retreading old ground. However, Molly always has importance in Sherlock as a John mirror, and just because she is dressed as a man here doesn’t mean we should disregard this. If anything, her ridiculous moustache is as silly as John’s here! Molly, although really a member of the resistance, is able to pass in the world she moves in in 1895, but only by masking her own identity. This is exactly what happens to John in the Victorian era – as a bisexual man married to a woman, he is able to pass, but it is not his true identity. More than that, Molly is a member of the resistance, suggesting not just that John is queer but that he’s aware of it and actively looking for it to change.

I know I was joking about Molly and John’s moustaches, but putting such a silly moustache on Molly links to the silliness of John’s moustaches, which only appear when he’s engaged to a woman and in the Victorian era. He has also grown the moustache just so the illustrator will recognise him, and Molly has grown her moustache so that she will be recognised as a man. In this case, Molly is here to demonstrate the fact that John is passing, but only ever passing. Furthermore, Molly, who is normally the kindest person in the whole show, is bitter and angry throughout TAB – it’s not difficult to see then how hiding one’s identity can affect one’s mental health. I really do think that John is a lot more abrasive in TAB than he is in the rest of the show, but that’s not the whole story. Showing how repression can completely impair one’s personality also points to the suicidal impulses that are lurking just out of sight throughout TAB – this is what Sherlock is terrified of, and again his brain is warning him just what it is that is causing John this much pain and uncharacteristic distress.

This is just about the loosest sketch of TAB that could exist! But TAB meta has been so extensive that going over it seems futile, or else too grand a project within a short chapter. Certain theories are still formulating, and may appear at a later date! But what this chapter (I hope) has achieved has set up the patterns that we’re going to see play out in s4 – between the metatextuality, the waters of the mind and the role of Moriarty in the psyche, we can use TAB as a key with which to read s4. I like to think of it as a gift from Mofftiss, knowing just how cryptic s4 would be – and these are the basic clues with which to solve it.

That’s it for TAB, at least in this series – next up we’re going ever deeper, to find out exactly who is Eurus. See you then?

#tjlc#emp theory#thewatsonbeekeepers#my meta#meta#mine#chapter four: it is always 1895#vincent starrett#mofftiss#1895#bbc sherlock#johnlock#tjlc is real

79 notes

·

View notes

Link

MARTY GODDARD’S FIRST FLASH OF INSIGHT CAME IN 1972. It all started when she marched into a shabby townhouse on Halsted Street in Chicago to volunteer at a crisis hotline for teenagers.

Most of the other volunteers were hippies with scraggly manes and love beads. But not Marty Goddard. She tended to wear business clothes: a jacket with a modest skirt, pantyhose, low heels. She hid her eyes behind owlish glasses and kept her blond hair short. Not much makeup; maybe a plum lip. She was 31, divorced, with a mordant sense of humor. Her name was Martha, but everyone called her Marty. She liked hiding behind a man’s name. It was useful.

As a volunteer, Ms. Goddard lent a sympathetic ear to the troubled kids then called “runaway teenagers.” They were pregnant, homeless, suicidal, strung out. She was surprised to discover that many weren’t rebels who’d left home seeking adventure; they were victims who had fled sexual abuse. The phones were ringing with the news that kids didn’t feel safe around their own families. “I was just beside myself when I found the extent of the problem,” she later said.

She began to formulate questions that almost no one was asking back in the early ’70s: Why were so many predators getting away with it? And what would it take to stop them?

Ms. Goddard would go on to lead a campaign to treat sexual assault as a crime that could be investigated, rather than as a feminine delusion. She began a revolution in forensics by envisioning the first standardized rape kit, containing items like swabs and combs to gather evidence, and envelopes to seal it in. The kit is one of the most powerful tools ever invented to bring criminals to justice. And yet, you’ve never heard of Marty Goddard. In many ways she and her invention shared the same fate. They were enormously important and consistently overlooked.

I was infuriated when I read a few years ago about the hundreds of thousands of unexamined rape kits piled up in warehouses around the country. I had the same question that many did: How many rapists were walking free because this evidence had gone ignored?

Take for example, the case of Nathan Ford, who sexually assaulted a woman in 1995. Although a rape kit was submitted to the police, it went untested for 17 years.

During that time, he went on to assault 21 other people, before being convicted in 2006.

And I had another question: How could a tool as potentially powerful as the rape kit have come into existence in the first place? For nearly two decades, I’d been reporting on inventors, breakthroughs and the ways that new technologies can bring about social change. It seemed to me that the rape-kit system was an invention like no other. Can you think of any other technology designed to hold men accountable for brutalizing women?

As soon as I began to investigate the rape kit’s origins, however, I stumbled across a mystery. Most sources credited a Chicago police sergeant, Louis Vitullo, with developing the kit in the 1970s. But a few described the invention as a collaboration between Mr. Vitullo and an activist, Martha Goddard. Where was the truth? As so often happens in stories about rape, I found myself wondering whom to believe.

Mr. Vitullo died in 2006. Ms. Goddard, as far as I could tell, must still be alive — I couldn’t find any obituaries or gravestones that matched her name. An interview in 2003 placed her in Phoenix, and so I collected phone listings for Martha Goddard in Arizona and called them one after another. All those numbers had been disconnected.

Little did I know that I would have to hunt for six months before I finally solved the mystery. I would learn she had transformed the criminal-justice system, though her role has never been fully acknowledged. And I would also discover that Louis Vitullo — far from being the inventor of the rape kit — may have taken credit for Ms. Goddard’s genius and insisted that his name be put on the equipment.

I pieced together dozens of obscure marriage and death notices to try to find her family members; read through hundreds of newspaper articles to establish the timeline of events; and even hired a researcher to dig through an archive of Chicago police department files from the ’70s. Finally, I managed to speak to eight people who knew or worked with her. From these sources, and two oral-history tapes in which she told her life story, I cobbled together what happened.

Back in that Chicago crisis center, Marty Goddard encouraged teenagers to confide in her, and she began to realize just how many of them had been molested.

At the time, most people believed that sexual abuse of children was rare. One psychiatric textbook from the 1970s estimated that incest occurred in only about one in every million families, and claimed that it was often the fault of girls who initiated sex with their fathers. Meantime, it was still legal in every state in America for a husband to rape his wife. Sexual violence that happened within a family was not considered rape at all. A real rape was a “street rape.” It happened to women stupid enough to be in the wrong places at the wrong times.

In Chicago, rape seemed like some sort of natural disaster, no different from the arctic winds that could kill you if you wandered out in the winter without a coat. “Chicago was not a city you wanted to venture out into after dark,” wrote the activist Naomi Weisstein. “Rape was epidemic.” In 1973, an estimated 16,000 people were sexually assaulted in and around Chicago. Only a tenth of those attacks were reported to the police and fewer than a tenth of those cases went to trial; an infinitesimal fraction of perpetrators ended up in prison.

It was a time — much like our own — when millions of people felt that the police had failed them. Chicago was still reeling from the 1969 killing by the cops of Fred Hampton, the chairman of the Illinois Black Panther Party, while he’d been sleeping in his own bed. The Chicago Police Department was notorious as a brutal, occupying force in black neighborhoods. Citizens’ groups were demanding review boards to reform officers’ behavior.

Amid all that, Ms. Goddard began asking questions that might seem so obvious to us today, but were radical in her own time: What if sexual assault could be investigated? What if you could prove it? What if, instead of a “she said” story, you could persuade a jury with scientific evidence?

A lot of men didn’t like her style. But Ray Wieboldt Jr., heir to a Chicago department-store fortune, did, and in 1972 she was hired as an executive at the Wieboldt Foundation, a charitable family fund that rained down money on progressive causes.

The Wieboldt name became her secret weapon. “I could say, ‘I’m Marty Goddard from the Wieboldt Foundation’ and people would just let me in their doors,” she recounted. And so she Wieboldt-ed her way in to meet with hospital managers and victims’ groups and began asking her relentless questions about rape.

Crime labs did not yet have the ability to test DNA; the first use of DNA forensics would not come until 1986, when British investigators used the technology to hunt down a murderer who raped his victims. But they could analyze pieces of glass, fingerprints, splatter patterns, firearms and fibers. Police investigators could find biological clues to help establish the identity of a suspect by, for instance, comparing blood types.

Ms. Goddard wanted to figure out why — even with all this evidence — no one seemed able to prove that a sexual assault had occurred. She learned that victims usually ended up in a hospital after an assault. The cops might dump a shivering, weeping woman in the emergency room and yell out, “We got a rape for you.” As they cared for the victim, the nurses might wash her off or throw away her bloody dress, inadvertently destroying evidence.

The cops didn’t seem to care. Instead, they would isolate the victim in a room and lob questions at her to try to determine whether she was lying. A Chicago police training manual from 1973 declared, “Many rape complaints are not legitimate,” and added, “It is unfortunate that many women will claim they have been raped in order to get revenge against an unfaithful lover or boyfriend with a roving eye.” Officers would routinely ask women what they’d been wearing, whether they’d provoked the attack by acting in a seductive manner, and whether they had enjoyed the sex. “An actual rape victim will generally give the impression of a person who has been dishonored,” according to the manual.

In the early days of forensic science, the 19th century, rape exams sought primarily to test the virtue of women. A doctor would be called in to examine a woman’s vagina and then report on her motives. Was she a trollop, a harlot, or a pure-hearted innocent who spoke the truth?

In 1868, a British publication, Reynolds’s Newspaper, reported on one such exam. The surgeon “gave such evidence as left no doubt that the prosecutrix could not have been so innocent as she had represented herself to be.” The magistrate “said no jury would convict on such evidence, and he should discharge the prisoner.”

In other words, sexual-assault forensics began as a system for men to decide what they felt about the victim — whether she deserved to be considered a “victim” at all. It had little to do with identifying a perpetrator or establishing what had actually happened.

Even in the 1970s, the forensic examination remained a formality, a kind of kabuki theater of scientific justice. The police officers wielded absolute power in the situation; they told the story; they assigned blame. And they didn’t want to give up that power.

Ms. Goddard’s insight was that the only fix for this dysfunctional system would be incontrovertible scientific proof, the same kind used in a robbery or attempted murder. The victim’s story should be supported with evidence from the crime lab to build a case that would convince juries. To get that evidence, she needed a device that would encourage the hospital staff members, the detectives and the lab technicians to collaborate with the victim. On the most basic level, Ms. Goddard realized, she had to find a mechanism that would protect the evidence from a system that was designed to destroy it.

EVEN AFTER MONTHS of searching for Marty Goddard, I hadn’t been able to find her, or even figure out the names of her family members. But I did manage to track down Cynthia Gehrie, an activist who’d been swept up in Ms. Goddard’s crusade.

The two women met at a gathering for anti-rape activists in 1973 and soon they were strategizing over lunches and dinners, notebooks by their plates. At the time, Ms. Gehrie worked a day job at the A.C.L.U.; she was so impressed by Ms. Goddard that she volunteered to be her sidekick as they figured out how to force men in power to reckon with the rape epidemic.

Their timing was excellent, because 1974 was the year that everything flipped in Chicago. Women who had once been ashamed were now speaking out.

In October, a delegation of suburban women gathered before the members of the Illinois General Assembly. One described how she’d tried to fend off a sexual attacker with a fireplace poker. After the assault, she had carefully saved the bent poker and handed this piece of evidence to police detectives. Then, she recounted through tears, the police returned the poker to her straightened out. The idiots thought she had wanted them to fix it.

A mother stood before the committee and said that her little girl had been molested on her way to kindergarten. The police were already familiar with the attacker, a pedophile who had infected at least one child with venereal disease. And yet he was roaming free.

A nurse at the meeting explained how medical staff handled rape cases — and in the middle of her testimony, announced, “I am a rape victim myself.”

A few days later, about 70 women from a group called Chicago Legal Action for Women, CLAW for short, flooded into the office of State’s Attorney Bernard Carey, and plastered the walls with messages like “Wanted: Bernard Carey for Aiding and Abetting Rapists.”

The rape problem had suddenly become Mr. Carey’s problem, and he desperately needed to look as if he had an answer.

A movement was beginning — an awakening, like #MeToo. The fact that many of these activists were well-off white women forced politicians to pay attention. Black women in Chicago's poorest neighborhoods were most at risk of sexual violence, but their stories rarely made it into the newspapers, and rape was all too often portrayed as an affliction of the suburbs. Throughout her career, Ms. Goddard would wrestle with this disparity and try to overcome it. In 1982 she told an Illinois state legislative committee that “the lack of services on the South and West Sides of Chicago where a majority of our black victims reside” was “totally disgraceful.”

Now, though, in the early 1970s, she had just one obsession. She was determined to convince Bernard Carey that the problem could be solved, if he only had the will to do it. One day she showed up unannounced at his office and to her surprise, he welcomed her in. “I don’t know what the answer is,” he told her. But he had a new plan: He was going to let women like Ms. Goddard help figure out the rape problem for themselves. He appointed her and Ms. Gehrie to a citizens’ advisory panel on rape. Their mission: to investigate the failures in policing and suggest sweeping reforms.

Marty Goddard finally had what she wanted: permission to get inside the police departments.

With her new investigative powers, she headed to the Chicago crime lab building to ask police officers what was going wrong. Years later, she described what she had learned there in the oral history tapes. The cops blamed hospital workers, saying: “We don’t get hair. We don’t get fingernail scrapings.” The slides weren’t labeled, and they’d been “rubber-banded” together so that they contaminated one another. “So there goes that. It’s worthless,” the detectives told her.

The problem, she realized, was that no one had bothered to tell the nurses and doctors how to collect evidence properly.

What if hospitals could be stocked with easy-to-use forensic tools that would encourage medics, detectives and lab technicians to collaborate instead of pointing fingers? Gradually, these concepts solidified into an object: a kit stocked with swabs, vials and instructions.

Somewhere along the way, Ms. Goddard had befriended Rudy Nimocks, an African-American police officer who had handled incest cases and been horrified by what he’d seen. Ms. Goddard and Ms. Gehrie described Mr. Nimocks as a mentor. (He would be in his 90s now; I made multiple attempts to reach him without success.) According to several sources, Mr. Nimocks warned Ms. Goddard to proceed carefully. He told her that she should take care not to challenge the men in the crime lab directly. And he said that she’d need Sgt. Louis Vitullo, the head of the microscope unit, on her side.

Sergeant Vitullo was a scruffy cop-scientist, with a lab coat pulled hastily over his rumpled shirt and the pale, haunted look of a man who spent hours peering at murder weapons.

One day, Ms. Goddard found Sergeant Vitullo at his desk, introduced herself, and presented him with a written description of the rape-kit system. She must have been blindsided by what happened next.

“He screamed at her,” according to Ms. Gehrie. “He told her she had no business getting involved with this and that what she was talking about was crazy. She was wasting his time. He didn’t want to hear about this anymore.” Ms. Gerhie said Ms. Goddard called her minutes later to vent about being thrown out of Sergeant Vitullo’s office.

“Well, that didn’t go so well!” Ms. Goddard said wryly.

As far as Ms. Goddard knew at that moment, the rape-kit idea had just been killed off.

INVENTION, ARCHITECTURE, DESIGN — these are not just technical feats. They are political acts. The inventor offers us a magical new ability that can be wonderful or terrifying: to halt disease, to map the ocean floor, to replace a human worker with a machine, or to kill enemies more efficiently. And those magical abilities create winners and losers. The Harvard professor Sheila Jasanoff has observed that technology “rules us much as laws do.”

When it comes to sexual assault, there are many inventions I can think of that help men get away with it — from the date-rape drug to “stalkerware” software. More striking is how few inventions, how little technology and design, has been devoted to keeping women safe.

Think about our public spaces, and how much they reinforce the power of men. If you grew up as a girl, you were taught to map out potential sexual attacks when you walked through any city. A hidden doorway, an empty subway platform, a pedestrian bridge with high walls — such places pulse with threat.

In my high-school driving class, the instructor lectured us about the dangers that lurked in empty parking lots. “Ladies, you don’t want to be fumbling in your purse if someone jumps out of the bushes,” he said, and suggested that we hold the car keys in one hand as we hurried to the car. Even as a teenager, I remember thinking how crazy this sounded. If there were rapists lurking everywhere, couldn’t the grownups do something about that?

I learned that the streets did not belong to me. Nor did the stairwells or the empty laundry rooms at midnight. I still remember the sense of defeat my first week as a college student on a pastoral Connecticut campus in the 1980s. I’d been aching to explore its tantalizing forests and hidden ponds. But then the freshman girls were herded into a lecture hall, and the head of public safety told us that if we wanted to walk from one building to another at night, we should first call the escort service that squired females around and protected them from rape.

“No way!” I thought.

And yet, at that time I was struggling to understand — and forgive myself for — having been molested as a small child. And though I never did use the campus escort service, I also never felt that the campus was mine.

But this is not how it has to be. It’s entirely possible to create public spaces and tools for everyone. Our environment and technology can foster a sense of equality and pluralism.

At the same time that Marty Goddard was trying to reinvent forensic technology, the disabled community was radically transforming the design of cities by pushing to make streets and buildings wheelchair-accessible. A wheelchair ramp does more than just allow someone to roll into a building; it also sends out a message that the people in those wheelchairs are important and worthy of dignity. This is the power of invention.

You can see why the idea of a rape kit might have been offensive to Sergeant Vitullo and other police officers. Like many of the great technological ideas, this one blasted through the assumptions of the day: that nurses were too stupid to collect forensic evidence; that women who “cried rape” were usually lying; and that evidence didn’t really matter when it came to rape, because rape was impossible to prove.

Now here was this proposal for a cardboard box packed with tools that would allow anyone to perform police work.

Despite his original reaction, Sergeant Vitullo mulled over Ms. Goddard’s idea. He must have found it intriguing. He studied the plans she’d shown him. And he began to see the sense in it all.

One day, Ms. Gehrie told me, Sergeant Vitullo called up Ms. Goddard and said, “I’ve got something to show you.” When Ms. Goddard arrived in his office, Ms. Gehrie recalled, “he handed her a full model of the kit with all the items enclosed.” Sergeant Vitullo had assembled a prototype for the rape kit and added a few flourishes of his own. And now, apparently, he regarded himself as its inventor.

Another friend of Ms. Goddard’s confirmed this story. Mary Sladek Dreiser, who met Ms. Goddard in 1980, told me that Ms. Goddard always praised Sergeant Vitullo in public. But in private, she described him as a petty tyrant who would “only go along with the kit if it were named after him.”

The rape-kit idea was presented to the public as

a collaboration between the state attorney’s office and the police department, with men running both sides...

..and little credit given to the women who had pushed

for reform. Ms. Goddard agreed to this, Ms. Gehrie said, because she saw that it was the only way to make the rape kit happen

In the mid-1970s, while still at the Wieboldt Foundation, Ms. Goddard began working nights and weekends to found a nonprofit group called the Citizens Committee for Victim Assistance. The group filed a trademark for the Vitullo Evidence Collection Kit in 1978, ensuring that her creation would be branded with a man’s name. For years afterward, the newspapers called the rape kit the “Vitullo kit.” When he died in 2006, an obituary headline celebrated him as the “Man Who Invented the Rape Kit.” His wife, Betty, quoted in the obituary, said that her husband was “proud” of the rape kit “but he didn’t get any royalties for it.” The obituary hailed Mr. Vitullo as a pioneer in a new form of evidence collection that transformed the criminal-justice system. There was no mention of Ms. Goddard.

Even if her name wasn’t on it, Ms. Goddard finally had permission to start a citywide rape-kit system. What she didn’t have was any money to create the kits, distribute them, or train nurses to use them. She had to raise all those funds through her nonprofit group, which represented survivors of sex crimes.

This seems strange. After all, state governments covered the cost of running homicide evidence through the crime lab, so why should sexual assault be any different?

And yet it was. And it still is.

Money problems have always haunted the rape-kit system. Testing a rape kit is expensive; today it costs $1,000 to $1,500. Except in the highest-profile cases, police departments have often pleaded underfunding, and let the kits pile up. That’s why victims themselves have had to bankroll crime labs. In the past decade, groups like the Joyful Heart Foundation have helped raise millions of dollars to test rape kits. The money sometimes comes from bake sales, Etsy crafts and feminist comedy nights.

Fundraising was even harder in the 1970s, however, when most foundations wouldn’t give money to a project with “rape” or “sex” in its title. And so Ms. Goddard had to resort to finding money wherever she could. This is where Hugh Hefner enters the story.

Chicago was built on soft-core porn, and Mr. Hefner was one of the city’s most prominent moguls. Men in suits sidled into his clubhouses for three-martini lunches, celebrities swanned into his mansion for glittering fund-raisers, and a blazing “Playboy” sign scalded the downtown skyline.

Mr. Hefner regarded the women’s liberation movement as a sister cause to his own effort to free men from shame and guilt. And so his philanthropic Playboy Foundation showered money on feminist causes. In the early 1970s, for example, the Playboy fortune provided the seed money for the A.C.L.U. Women’s Rights Project, which was co-founded by a little-known lawyer named Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

In the mid-1970s, Ms. Goddard applied to Playboy for a $10,000 grant (the equivalent of about $50,000 today) to start a rape-kit system. And she got it.

Her collaboration with the Playboy Foundation turned out to be a surprisingly ideal one, in large part because Ms. Goddard had a friend on the inside: Margaret Pokorny (then known as Margaret Standish). Ms. Pokorny brainstormed all kinds of ways to support the project that went beyond the big check. For instance, she recruited Playboy’s graphics designers to create the packaging for the kit. And when Ms. Goddard needed volunteers to assemble the kits, Ms. Pokorny came up with a creative solution: old ladies.

“I’ve got this great idea, Marty,” Ms. Goddard recalled Ms. Pokorny saying. “Everybody just loves the Playboy bunny and these older women, they want something to do.” So one day a horde of them showed up in the Playboy offices, swilling free coffee as they assembled sexual-assault evidence kits.

In 1978, Marty Goddard delivered the first standardized rape kit to around 25 hospitals in the Chicago area for use in a pilot program she had designed — “the first program of its type in the nation,” according to a newspaper article.

The kits cost $2.50 each and contained test tubes, slides and packaging materials to protect the specimens from mixing; a comb for collecting hair and fiber; sterile nail clippers; and a bag for the victim’s clothing. There was a card for the victim, giving her information about where to seek counseling and further medical services.

The New York Times, which described the initiative as a collaboration between Mr. Vitullo and Ms. Goddard, said that the “innocuous looking” box “could be a powerful new weapon in the conviction of rapists.” The Times noted that one of the most important features of the system was deceptively low-tech: “Forms for the doctor and the police officers involved are included, as are sealing tape and a pencil for writing on the slides. Anyone who handles the box must put his or her signature on printed spaces on the kit’s cover.” There would be a paper trail that showed how the evidence had traveled from the victim’s body to the crime lab.

By the end of 1979, nearly 3,000 kits had been turned over to crime labs. One of them had been submitted by a bus driver who’d been abducted and raped by 28-year-old William Johnson. He was sentenced to 60 years in prison, and the Vitullo Evidence Kit was credited with winning the day in court.

By now, Ms. Goddard’s friend Rudy Nimocks had been promoted to head the sex homicide department. He told The Chicago Tribune that the new system had improved evidence collection. But perhaps more important, the kit worked magic in the courtroom. “In addition to the kits being very practical,” he said, “we find that it impresses the jurors when you have a uniform set of criteria in the collection of evidence.”

In other words, the rape kit, with its official blue-and-white packaging and its stamps and seals, functioned as a theatrical prop as well as a scientific tool. The woman in the witness box, weeping as she recounted how her husband tried to kill her, could sound to a judge and jury like a greedy little opportunist. But then a crime-lab technician would take the stand and show them the ripped dress, the semen stains, the blood. When a scientist in a lab coat affirmed the story, it seemed true.

Ms. Goddard had invented not just the kit, but a new way of thinking about prosecuting rape. Now, when a victim testified, she no longer did so alone. Doctors, nurses and forensic scientists backed up her version of the events — and the kit itself became a character in the trials. It, too, became a witness.

That’s another reason Ms. Goddard may have been willing to trademark her idea under Sergeant Vitullo’s name. It was as if in order to invent, she also had to disappear. The rape kit simply never would have had traction if a woman with no scientific credentials had been known as its sole inventor. It had to come from a man.

The word “technology” is part of the problem. It’s a synonym for “stuff that men do.” As the historian Autumn Stanley pointed out, a revised history of technology taking into account women’s contributions would include all sorts of “unimportant” inventions like baby cribs, menstrual pads and food preservation techniques. Sometimes the only way that women could navigate this world was to let a white man in a lab coat become the face of their radical ideas, while they themselves shrank into the background.

During World War II, for instance, a team of six “girls” figured out how to operate the world’s first all-purpose electronic digital computer, called the ENIAC. In 1946, one of them, Betty Holberton, stayed up half the night to ensure that the computer would ace its debut in front of the newspaper cameras. And yet she and the others were treated like switchboard operators, mere helpers to the male engineers. Ms. Holberton went on to invent and design many of the essential tools of computing during the 1950s and ’60s almost invisibly, while her male colleagues were celebrated as geniuses of the age.

Ms. Goddard, certainly, had mastered the art of vanishing. Her friends and collaborators from the 1970s had lost touch with her, and were just as flummoxed by her disappearance as I was. But they remembered her in vivid, disconnected flashes. I often felt that I was spying on her through keyholes into other people’s minds.

“She made miniature rooms,” Margaret Pokorny said, describing how Ms. Goddard spent hours with tweezers and tiny brushes constructing fairy-tale interiors inside of boxes. The rooms were scattered all around Ms. Goddard’s apartment, as if a dollhouse had been dissected.

From Cynthia Gehrie, I learned why Ms. Goddard might have been so driven to escape into Lilliputian fantasies. Ms. Gehrie told me that in the late 1970s, her friend had flown to a resort in Hawaii for a vacation and returned to Chicago a different, and broken, person. “I was raped,” Ms. Goddard had told Ms. Gehrie, pouring out a harrowing account of how a man had abducted her.

“He drove her to a remote location,” Ms. Gehrie said. “He taunted her with the knife. She told him she would do whatever he wanted. Finally, he drove her back to the resort. She was astonished when he let her go.” Ms. Gehrie can’t remember whether Ms. Goddard reported the rape to the police, but she’s always wondered if her friend’s prominence as a victims-rights advocate had made her a target. The attacker had won her trust, Ms. Goddard said, by pretending to be a supporter of her cause.

In one obscure interview I found, Ms. Goddard herself mentioned that rape and the scars it left on her body. And, she said, the attacker had infected her with herpes.

I was heartbroken for her, and more determined to find her than ever. By now she had become “Marty” to me — I could think of her only as a friend. I surmised, from the string of addresses she’d left behind, that she had been spiraling into poverty. She would have been 79. Was anyone caring for her? I felt less and less like a journalist chasing down a story. What I really wanted was to save Marty Goddard before it was too late.

Through the 1980s, Ms. Goddard kept fighting for the rape-kit system despite her growing exhaustion. It was “one incident by one incident by one incident,” she said later. “Imagine how many years it took us to go from state’s attorney to state’s attorney to cop to detective to deputy to doctor to pediatrician to nurse to nurse practitioner” and train each person who interacted with the victim and the rape kit. “I felt I had to save the world, and I was going to start with Chicago and move to Cook County and move to the rest of the state. And there was something in the back of my mind that said, ‘Gee, maybe the circumstances will be such that at some time I can go beyond the borders of Illinois.’”

She was right. In 1982, New York City adopted Ms. Goddard’s system because “its effectiveness was demonstrated in Chicago,” according to The New York Times. Within a few years, the city had amassed thousands of sealed kits containing evidence, and the system was putting rapists in prison.

Ms. Goddard had envisioned a kind of internet of forensics at a time when the internet itself was in its infancy. The idea was to standardize practices in crime labs everywhere and encourage police departments to share data to catch perpetrators who might cross county and state lines. And she had personal reasons for grinding away at the problem, for making it her obsessive mission. The man who had brutalized her in Hawaii still walked free. She knew this because she’d seen him, she told a friend at the time.

She had been walking to the attorney general’s office in downtown Chicago when her attacker materialized out of the crowd and locked eyes with her. It must have been a waking nightmare. Had he been stalking her? Had it been a chance encounter?

I don’t know. She was under an extraordinary amount of stress; maybe she was mistaken. I am working from fragments — from bits and pieces of her friends’ memories. What I do know is that Ms. Goddard began to drink; that she depended now on cheap sherry to dull the pain. She was dragging herself from city to city, evangelizing for the rape kit, sleeping in dive motels, giving everything she had until there was nothing left.

In 1984, the F.B.I. held a conference at its training center in Quantico, Va. Expert criminologists flew in to discuss a new system that would detect the serial killers and rapists operating across state lines. But to the dismay of Ms. Goddard, who attended the conference, the country’s top lawmen demonstrated little empathy for victims.

“So, this one man gets up,” a professor known as an expert in sex crimes, Ms. Goddard remembered later. The professor flashed slides on the screen, a twisted parade of naked female corpses. He made little effort to protect the identities of the dead women. Ms. Goddard was horrified at the way he “couldn’t wait to show the bite marks on the breasts” of one victim, as if to share his titillation with the audience.

That kind of attitude might have gone unremarked at a police convention, but there were lawyers, victims’ advocates and nurses at this conference and they “didn’t appreciate it.” Just as dismaying, this so-called expert described “interrogating” women who’d been raped, as if they were the criminals.

“I went nuts,” Ms. Goddard said. She gripped the arms of her chair, “saying to myself: ‘Calm down. Don’t say anything.’”

AFTER THE PRESENTATION, Ms. Goddard approached one of the organizers and said, “Something’s wrong here, and I really object.” Working on the fly, Ms. Goddard gave a presentation about her pilot project in Chicago, explaining how the rape-kit system worked. Afterward, “two guys from the Department of Justice” approached her and asked her to replicate her program all around the country. She was finally given enough funding to travel to more than a dozen different states and help start up pilot programs.

“I don’t know how my cat survived,” she said of those years. “I was gone all the time.”

She was tired out. And “so many people were downright insulting.” They’d ask her why she was an authority on forensics: “Are you a cop? An attorney?” Ms. Goddard was drinking heavily. She began to step away from her prominent role in criminal justice. She moved to Texas, and then Arizona. And finally she faded from public view so thoroughly that I believe she must have decided to disappear.

Her friend and former colleague Mary Dreiser kept in touch. But one day in about 2006 or 2007, Ms. Dreiser was distressed to dial Ms. Goddard’s number and discover it had been disconnected. Ms. Dreiser’s husband, a lawyer, asked a detective to find Ms. Goddard. She turned up in a mobile-home park in Arizona. “She was happy I had tracked her down,” Ms. Dreiser said.

By the time I started searching for Ms. Goddard a decade later, she had moved out of that trailer and her most recent listing suggested she lived in a dumpy apartment building alongside a Phoenix highway. That phone, too, had been disconnected, so I’d assumed that she had moved on once again, perhaps to a nursing home. But just in case, I called up the building’s management office and asked if the people there could tell me anything about Marty Goddard.

“Unfortunately, I can’t,” said the woman who answered the phone. There were rules about protecting the privacy of residents.

But rules are meant to be broken. So I called back. “Listen,” I said, “just hear me out.”

I then plied the woman in the management office with a brief — and, I hoped, heart-melting — tribute to Ms. Goddard’s genius and her sacrifices.

It worked. “OK,” she said, “let me check into it.” Hours later, she called me back. Marty Goddard had indeed lived in their apartment building, she said, then paused.

“And I’m very sorry to tell you that she passed away.”

The news walloped me. Ms. Goddard had died in 2015, at the age of 74, but there had been no obituary. No announcement. I’d searched for pictures of headstones, remembrances, funeral announcements, and I’d found nothing. This woman who had done so much for the rest of us. How could this be?

Paradoxically, at the same time as Ms. Goddard was fading from sight, her name no longer in the papers, the advent of DNA forensics was giving the rape kit a new kind of superpower.

In 1988, a court ordered Victor Lopez, a 42-year-old repeat felon accused of violent attacks, to submit to a blood draw. He would be the first defendant in New York State to be linked to a crime through DNA analysis — and the case would prove the dazzling effectiveness of this new tool. The DNA test showed a strong match between Mr. Lopez’s blood and the semen collected from one of his victims. Mr. Lopez was convicted of three sexual assaults and sentenced to 100 years in prison. One juror, John Bischoff, told The New York Times that “the DNA was kind of a sealer on the thing. You can’t really argue with science.”

When Ms. Goddard began her work, crime labs could establish only a fuzzy connection between a suspect’s blood and the swabs inside the kit — for instance, by showing that the blood type was a match. But now, DNA markers could reveal the path of a perpetrator as he left his semen or blood at multiple crime scenes.

Starting in 2003, several women across the country

accused a man named Nathan Loebe of sexual assault, but

those accusations had never stuck.

After the Tucson police received a grant to test a

backlog of rape kits, they discovered that DNA from several of the kits matched Mr. Loebe. Rape-kit evidence revealed the

pattern of his attacks, and last year he was sentenced to 274 years in prison, including for 12 counts of sexual assault.