#western heritage of literature

Text

“There is a wisdom that is woe; but there is a woe that is madness. And there is a Catskill eagle in some souls that can alike dive down into the blackest gorges, and soar out of them again and become invisible in the sunny spaces. And even if he for ever flies within the gorge, his lowest swoop the mountain eagle is still higher than other birds upon the plain, even though they soar.”

—Herman Melville, Moby-Dick

#great lines#great writing#herman melville#moby dick#great stories#western heritage of literature#great writers#19th century literature#wisdom

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

We are not immune to the lure of wonder and mystery and awe: we have music and art and literature, and find that the serious ethical dilemmas are better handled by Shakespeare and Tolstoy and Schiller and Dostoyevsky than in the mythical morality tales of the holy books.

- Christopher Hitchens

I love the pugilistic intelligence combined with the acerbic wit of Hitchens, but in this case, no. Religion was always his fatal blind spot. On the contrary, it’s precisely because Shakespare, Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, and Schiller were themselves not immune to the lure of wonder and mystery and awe of the bible and the Judeo-Christian heritage that they were born into that they gave us a language to wrestle with serious ethical dilemmas for every age.

#hitchens#christopher hitchens#quote#ethics#shakespeare#tolstoy#dostoyevsky#schiller#Christianity#judeo-christian heritage#heritage#books#learning#society#Religion#western civilisation#music#art#literature#culture#icon

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

PAN-AFRICAN SERIES: CULTURALLY CASTRATED: WHY LITERATURE SHOULD NURTURE US BACK TO CULTURAL HEALTH?

View On WordPress

#African Education System#Cultural Heritage#Cultural Identity#Culture#Literature#Okot p&039;Bitek#Western Education System

0 notes

Text

just a very quick explanation about eastern european melancholy because it seems important to me -- this term as well as the general concept of melancholy can often be found in art and literature analysis and basically describes how the general depiction of eastern europe is... less than favourable. for example, eastern european characters like in bram stoker's dracula are characterised as being distincly different and not as culturally advanced compared to "modern" western cultures, a trend that is sometimes still seen today when looking at cultural stereotypes.

in the context of the movie damon and kris watched as well as historically, this term now more often refers to a general feeling of hopelessness that is caused by unstable political as well as economic conditions due to the situation post wwii and then the dissolution of the soviet union as well as yugoslavia.

the fact that damon and kris both felt that it was important to illustrate this cultural aspect not just through art but by choosing to evoke a female figure, a slavic babushka, means a lot to me, personally. i was joking with @izpira-se-zlato that damon made kris look like my grandma -- but, as with a lot of people here i assume, my grandma was born in post-war eastern europe and was a young girl during the same time period this movie takes place in and was also forced to experience and live through a lot of hardships in early communist poland.

i do believe that kris feels a strong connection to his slavic heritage and culture (he was the one rambling about interslavic, after all) and the fact that damon felt something, too, while watching the movie and that they wanted to express it together is something that feels very, very important to me and i honestly love and appreciate them so much for doing that.

#joker out#i enjoyed the memes but i was also having a breakdown because this is so very important to me#sometimes i realise i have a degree that is indeed also focused on culture and not just literature can you believe#i guess the meaning is also very very apparent for a lot of slavic people here because well#we all live(d) through it#there's a reason why my parents emigrated#anyway#kris gu��tin#damon baker

138 notes

·

View notes

Text

I had it up to here. This is a review of the Iliad (!) and this person (White Anglophone, their country, US, controls Greece to a large degree) says Madeline Miller's work is better than a national epic??

And they evaluate - nay, reduce - the content of an epic my people have been making and preserving for centuries as "competition among men, petty gods, and long list of male family trees with some poetic snippets."

Excuse us stupid Greeks for respecting and recording family lines and tracing our lineage from the gods since time immemorial, I guess. Why don't you piss on our cultural figures and gods while you're at it, too? (Oh, wait, you did)

And you didn't even read the poetry of the original, which is honestly stunning at its phrasing, so, your loss. I guess your mind (and edition you read?) only caught "some" poetic snippets.

Typical behaviour of many Madeline Miller fans, unfortunately.

Honestly, honey, avoid the Odyssey and any other cultural epic. They don't deserve your eyes looking at their pages made by generations of my ancestors. And get outta here with your "I hate the all-male stuff" attitude. You have no idea of the huge contribution of our women of all ages to our literature and folklore.

I get if reading Epics isn't for you and if you don't enjoy them. But don't make it a problem of the Epics and people's cultural heritage. Placing "hot boy romance" and "(western) female rage" WASP feminism fantasies over ancient Epics is totally a you problem.

I feel like I'm going hard on that person but no, actually. They disrespected part of the Greek culture sooo much that I don't care, especially knowing more and more people are gonna have this attitude in the future. While shouting "I'm against colonialism and imperialism!" at that. (σε πιστεύουμε γλυκιά μου μη χτυπιέσαι)

But worry not! For the low price of $19.99 you too can have the colonialist attitude of a 19th century dandy!

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today “Dom Bohuna / Дім Богуна” celebrates its 4th anniversary

Perhaps, it is a proper moment for some summing-up reflections. I admit that I have created this blog 15.04.2020 only for fun. It was during the COVID-pandemic times, I was closed at home, recovering from a long illness. In such circumstances, some people return to their childhood fairy-tales. So I have returned to Bohun and “Ogniem i mieczem”. I was searching on the Internet for all possible groups of H. Sienkiewicz’s “Trilogy” fans, just to make friends with them, and I have found such a group here, on Tumblr and at the same time – some breathtakingly beautiful English stories about Helena, Jurko & Jan on AO3. For me, as a non-heterosexual person, their greatest value (for which I will be eternally grateful to their Authors!) was adding to my beloved “Trilogy” universe the motif of same-sex love and relationship. I wanted to contribute to it, so I have created my own Tumblr blog and an account on AO3, where I have published some from my own stories.

To be honest, the encounter with the Western “Ogniem i mieczem” fandom, seeing, how some people there perceive “Trilogy” characters, was a VERY shocking experience for me. One of these events, that are leaving you for years with a question circulating in your mind: “WHY??? What is wrong with this content, that people react to it (and to you, its admirer) in SUCH a way?” It is obvious, that H. Sienkiewicz’ “Trilogy”, created in the 19th century and telling about the historical events in the Eastern Europe from the mid-17th century, for contemporary readers can be in many aspects at least problematic (or difficult to accept). In general, it shouldn’t be, it can’t be taken uncritically now. But on the other side, it is not something worthless. Or “dirty”. Its characters (in their majority based on the real people from the past) can commit deeds viewed now as crimes, but they are still HUMANS. What is more, H. Sienkiewicz’ “Trilogy” is part of many people’s cultural heritage, entangled with countless events, heroes, myths, motifs from the Polish history (and in its first part, “Ogniem i mieczem” – also from the Ukrainian history). It is a part of MY OWN heritage and history. And I have felt uncomfortable with a thought, that in such an international community with a world-wide scope like Tumblr, someone, not having any basic knowledge about my culture/s, can think that this heritage is a “sluttish trash”. It is a reason why my blog has become “Dom Bohuna”, “Bohun’s Home”. I believe that the best way to solve such misunderstandings is spreading Knowledge and telling the Truth, so I try to show Bohun in his “natural environment”, on the one side: within H. Sienkiewicz’s “Trilogy” universe (with diverse masterpieces from the Polish culture related to it), on the other: within the Ukrainian tradition of Cossack Heroes (with various treasures of the Ukrainian culture related to it), with the Polish Romantic Cossack myth somewhere between them. I know that for a Western eye, they are all rather “distant islands”, but many parts of them are really worthy to have a closer look.

The next turning point was the February 2022. Here, no further explanation is required, I think. It was a time, when the whole our World has changed unimaginably and abruptly. And in these new circumstances, I realized one day, that I had a blog thematically related not only to the Polish literature/culture, but above all – to the Ukrainian Cossack Hero. I am deeply grateful to all my Ukrainian and Polish Friends for encouraging me to put here more content about the real Bohun and the history of the Cossack State (Hetmanate). You have given me courage. Because I hesitated, for two reasons. First: I know that I don’t have such in-depth knowledge about the Ukrainian culture, I have about the Polish one (so I can always make some hurtful mistakes). Second: I think that my blog, created for fun/fandom reasons, is not an entirely proper place for such an important content. But after all: it is a place, where one can just talk about the Ukrainian cultural heritage and turn some people's attention to it. That is why I try, as much as my limited skills and knowledge let me, to sing here about the Ukrainian Cossacks Glory. Just as Bohun himself used to do a long time ago.

#theophan-o talks#trylogia#ogniem i mieczem#with fire and sword#trylogia sienkiewicza#trylogia sensem życia#ukrainian culture#polish culture

50 notes

·

View notes

Note

https://www.tumblr.com/vavandeveresfan/723154446639661056/lore-olympus-gets-greek-mythology-wrong?source=share

It's posts like this that make me frustated. LO is a fiction comic BUT it's based on Greek mythology and Rachel downgraded and exploited so much it has nothing Greek to it and straight up disrespects our culture.

They can read it if they want, but don't complain when many people, especially Greeks say they don't like the series.

To address some things in the post:

As if we don't know western academia and the way westerners are taught about the Greek myths is imperialistic and gives them a sense of false ownership. If anything, "uneducated" people know more than op.

Also... does this person imply that Greeks and other people who call the comic out are not educated about the Greek myths? It's another thing to see the myths as Dr. Seuss's stories and another for them to be your freaking heritage. And they further prove how skewed their perspective is when saying this.

implying that the religion of our ancients is the same as a FUCKING COMIC

calling Roman literature on religion and the gods "fanfics"

Are they fucking 12 years old? the fuck??

#uugh the tone in the origincal post just killed me#lo defenders think they're the shit dont they#anti lo#anti lore olympus#answered

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

Meadow near 91st and Central Park West

Meadow near 91st and Central Park West

Central Park West, often abbreviated as CPW, is a prominent and prestigious avenue located along the western edge of Central Park in Manhattan, New York City. It is one of the city's most iconic and sought-after residential addresses, known for its historical significance, architectural grandeur, and cultural importance. Here are some key details about Central Park West:

Location: Central Park West runs parallel to Central Park, starting at 59th Street in the south and extending to 110th Street (also known as Cathedral Parkway) in the north. It forms the western boundary of Central Park and offers stunning views of the park's landscape.

Historical Significance: Central Park West is lined with a diverse array of architectural styles and historic buildings, many of which date back to the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It is often considered a showcase of New York City's architectural history.

Architectural Diversity: Along Central Park West, you'll find a mix of architectural styles, including Beaux-Arts, Renaissance Revival, Art Deco, and more. Notable buildings include The Dakota, The San Remo, The Eldorado, and The Beresford, all of which are famous for their architectural splendor and the notable residents who have called them home.

Cultural Institutions: Central Park West is home to several renowned cultural institutions, including the American Museum of Natural History, one of the largest and most prestigious natural history museums in the world. The Museum of Arts and Design (MAD) and the New-York Historical Society are also located along this avenue.

Residential Prestige: Central Park West has long been associated with luxury living. The buildings along this avenue often feature spacious apartments with park views, elegant pre-war details, and a high level of service. Many notable individuals, including celebrities and business moguls, have chosen to reside in this area.

Transportation: Central Park West is well-connected to the rest of Manhattan via public transportation. It is served by several subway lines, including the A, B, C, D, and 1 trains, making it relatively easy to access other parts of the city.

Scenic Beauty: Residents and visitors of Central Park West enjoy breathtaking views of Central Park, with its lush greenery, serene lakes, and iconic landmarks. The proximity to the park provides a sense of tranquility and natural beauty amidst the bustling city.

Cultural and Entertainment Events: Due to its proximity to Central Park and its cultural institutions, Central Park West is often a focal point for cultural and entertainment events, including parades, concerts, and film screenings.

Real Estate: Real estate along Central Park West is highly sought after and can command some of the highest prices in the city. The area is known for its co-op and condominium buildings, each with its own unique character and charm.

Historic Preservation: Many of the buildings along Central Park West are designated as New York City landmarks or are part of historic districts, ensuring their preservation and protection. This commitment to preserving the architectural heritage of the avenue contributes to its enduring charm.

Cultural Impact: Central Park West has been featured prominently in literature, film, and television, further cementing its status as an iconic New York City location. The Dakota, in particular, gained worldwide fame as the residence of John Lennon and Yoko Ono and was the site of Lennon's tragic shooting in 1980.

Parks and Recreation: In addition to Central Park itself, the avenue offers access to several smaller parks and green spaces, making it a desirable place for residents who value outdoor activities and leisure.

Educational Institutions: Central Park West is also home to some educational institutions, including the Fiorello H. LaGuardia High School of Music & Art and Performing Arts, renowned for its performing arts programs.

Shopping and Dining: The avenue features a mix of upscale shops, restaurants, and cafes, offering residents and visitors a range of dining and shopping options within walking distance.

Central Park West Parades: Central Park West is a popular route for parades and processions in New York City. One of the most famous parades is the annual Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade, which passes through this avenue on its way to Herald Square.

Transportation Hub: Central Park West provides convenient access to various transportation options, making it easy for residents to explore other parts of Manhattan and beyond. It's also a popular location for taxi and rideshare pick-ups.

Community and Neighborhood: The avenue is surrounded by vibrant neighborhoods, including the Upper West Side and Morningside Heights. These neighborhoods offer a mix of cultural attractions, dining, and shopping options that enhance the quality of life for those living on or near Central Park West.

In summary, Central Park West is a quintessential New York City avenue known for its historical significance, architectural beauty, cultural institutions, and luxurious residential offerings. It provides residents and visitors with a unique blend of urban living and access to the natural beauty and cultural richness of Central Park.

Central Park West remains a symbol of New York City's cultural and architectural richness, offering a blend of history, luxury, and natural beauty. Whether you're strolling along the avenue, enjoying the views of Central Park, or exploring the cultural institutions and dining options, Central Park West provides a unique and enriching experience in the heart of Manhattan.

#Meadow#Central Park#Central Park West#New York City#new york#newyork#New-York#nyc#NY#manhattan#urban#city#USA#buildings#visit-new-york.tumblr.com

216 notes

·

View notes

Note

Not gonna lie, I used to be one of the people who irreverently compared fanfiction to classical/classic literary works as a joke, but now it's gone too far for people in some circles. I do think there's a major problem with denigrating hobby-writers who like writing fanfiction. This especially goes for writers and readers who are women, not white, queer, etc. I do not think the Western anglophone literary canon should only be limited to White men because there are literary canons all over the world, and many in the anglophone West were, in fact, not written by strait White men. But I think I just got tired of the performative anti-intellectualism of it all that might speak to a larger insecurity with one's own hobby. Fanfiction is a very specific thing that couldn't exist without the concept of copyright. A part of the creation of fanfiction is that it's written with the intention to be read by fans of the same thing removed from the canonical events of the series or franchise. No, a fairy tale or myth retelling isn't fanfiction. An alternative history novel isn't fanfiction. A biographical historical fiction novel isn't fanfiction. Novels featuring appearances by real-life figures aren't fanfiction. And that's okay! I used to degrade all the Western literary "masters" because I was insecure about enjoying fanfiction, too, even though I also enjoy classical and classic works, so much so that I've gone on to get two degrees related to literature. I don't think someone has to like The Aeneid, but I do think to discuss it, we should have knowledge of the circumstances in which Virgil wrote it because works are time machines that are products of their time. Ultimately, I think if someone has to strip away the sociocultural and historical contexts behind things like The Aeneid first to compare it to fanfiction, it definitely says a lot more about how little that person thinks of fanfiction. How about for the future no one disrespects others' hobbies and interests to make themselves feel better?

--

Yes, it's a pity when people do the "everything is fanfic" thing...

Not least because there are some works that are genuinely interesting to analyze that way, like Raffles or all of the "Where is Watson's wound?" in jokes in Holmes adaptations. There absolutely are works that are riffing off of specific older things in a pointed way rather than just being retellings or using common cultural heritage.

But if we reduce all works that even vaguely reference anything older to this, we flatten that distinction, and it's boring.

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

not to code gotham as eastern europe but eastern europe is the gothic literature locus classicus so i'm in full right to do it and it's just such a good parallel because. for westerners/outsiders it looks like a literal nightmare but the locals find comfort and humour in all things that throw the foreigners off. you have to find hope in a place that the others claim to be unlivable. if you give up and leave, it will always stay in your heart like an open wound.

also it just never ceases to amaze me how there are so many similarities between gothic lit & eastern european lit of the period that we would never call 'gothic' because our ghosts and our supernatural elements are not portrayed as the Other most of the time. they're there to bring you closer to your culture and heritage. they are horrors that bring you home and connect you with your people. tell me this is not the perfect approach for gotham.

i think this is also why i hate the portrayal of the city as some unsalvageable monstrosity with no kidness to be found. often places where the circumstances seem the most dire, the cultures that are branded gruesome because of the focus on the dead produce the most loving communities, as they are needed.

#also the whole headcanon that people in gotham don't smile that is a thing in many fanfics#seems so silly but i'll stand behind it because this is how EE is#foreigners just being perpetually stunned at how people don't smile at them but are also the most hospitable folks you will ever meet#but yeah this is the thing you NEED to show the societal mentality in gotham as more collective#also this is why while i can see the appeal i don't really like the concept of jason just leaving gotham and starting a completely new life#without ever feeling like he assassinated a part of himself by never going back#*standing in the corner* they don't understand the depth of the emotional attachment to the fucked up place you come from#gotham is actually something that can be so personal#an extremely niche post#dear followers today i offer meta that caters specifically to ME#gotham#dc comics#batman#gotham love letters

223 notes

·

View notes

Text

As a fact of history and problem of contemporary geopolitics, Russia’s nature as an imperial power is incontrovertible. After World War I, the Russian Empire avoided the permanent dismemberment that befell other multi-ethnic land empires, such as the Ottoman Empire and Austria-Hungary. The Soviet Union not only reconquered most of the non-Russian lands that had declared independence from Moscow in the wake of the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution (including Ukraine, Belarus, Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan)—but even expanded the empire in the course of World War II, annexing Moldova, the western part of Ukraine, and other lands. Nor did the Soviet Union participate in the decolonization era. Even as the French and British empires were being dissolved, the Soviet Union was expanding its colonial reach, tightening its grip deep into Eastern and Central Europe with bloody crackdowns and military actions.

[...]

During the Cold War, Western universities, research institutions, and policy think tanks opened numerous centers and programs for Soviet, Russian, and Eurasian studies in a bid to better understand the Soviet Union and its heritage. However, these efforts had a strategic flaw: Born in an era when Moscow’s control reached far beyond today’s Russian borders, these programs inevitably framed the region through a Moscow-centric lens. Today, even as they dropped “Soviet” from their name, most of these programs have inherited this old Moscow-centric framing, effectively conflating Russia with the Soviet Union and downplaying the rich histories, varied cultures, and unique national identities of Eastern Europe, the Baltic States, the Caucasus, and Central Asia—not to mention the many conquered and colonized non-Russian peoples inhabiting wide swathes of the Russian Federation.

[...]

In many cases, Western academic programs require students to study the Russian language—often including courses in Moscow or Saint Petersburg—before they have the option of studying any of the region’s other languages, if they are so inclined and if those languages are even offered. A similar problem affects cultural studies, including literature and art, where the many ways Russian works—including the classics read by countless high school and university students—transport Moscow’s imperial ideology are rarely addressed. This only perpetuates the habit of looking at the former Soviet-controlled and Russian-occupied space through the prism of the world’s last unreconstructed imperial culture. Unwittingly, today’s Russia studies in the West still replicate the worldview of an oppressor state that has never examined its history and is nowhere near having a debate about its imperial nature at all—not even among the Russian intellectuals or so-called liberals with whom Western students, academics, and analysts generally interact and cooperate.

Finally, Western academia also presents Russia itself as a monolith, with little or no attention paid to the country’s Indigenous peoples. By now, many who study Russian history are at least vaguely familiar with the Stalin-era genocide of the Crimean Tatars and their replacement on the peninsula by Russian settlers. But why not shed more light on the Russian conquest and subjugation of Siberia, one of the most gruesome episodes of European colonialism? Or Russia’s 19th-century mass murder of the Circassians, Europe’s first modern-era genocide? What have we learned about the short-lived Idel-Ural state, a confederation of six autonomous Finno-Ugric and Turkic republics crushed by the Bolsheviks in 1918? Why not highlight Tatarstan, which proclaimed its independence from Russia in 1990? Nascent efforts to give Russia’s Indigenous peoples a voice have gotten underway, including the Free Peoples of Russia Forum that last convened in Sweden in December 2022—but they have hardly registered in Western academia. Not only are Western scholars’ interests and relationships Russia-centric; within Russia, those relationships and contacts are Moscow-centric. It’s as if Russia’s highly diverse regions didn’t exist.

#russia#russian culture#russian inmperialism#slavic studies#slavic tradition#slavic culture#decolonisation#postcolonialism#imperialism#rashism#rushism#academia

196 notes

·

View notes

Note

Could you talk about Gaelic? How many people are speak it today?

Indeed I can!

SCOTTISH GAELIC

"Gaelic" as a term can refer to any of the Goidelic branch of languages, which includes Irish, Scottish Gaelic, and Manx. HOWEVER, since today (November 30th) is Saint Andrew's Day, Scotland's national day, let's talk about Gàidhlig na h-Alba, or Scottish Gaelic! Latha Naomh Anndra sona dhuibh!

When referring to Scottish Gaelic, we pronounce the word "Gaelic" not as "gey-lick" but as "gal-lick", owing to its native pronunciation (which you can listen to here).

BEFORE THIS POST GETS TOO LONG, I urge the reader to consider learning this language! It's the source of my name after all ("Ian" is a form of "Iain" or "Eòin", both Gaelic forms of "John") and is the heritage language of as many as 40 million people worldwide. Even if you don't claim any Scottish ancestry, it's a beautiful and poetic language tied to an equally beautiful and poetic culture! Use it as a code language with your friends, read some classic Gaelic literature, or even pay a visit to Scotland and smugly read Gaelic road signs off to your friends/family/tour guide! (They'll love it, I promise.) I personally have been learning via Duolingo and other online resources for about 8 months now. And remember, "Is fheàrr Gàidhlig bhriste na Gàidhlig sa chiste" (better broken Gaelic than Gaelic in the coffin).

As of the 2011 Census, the total number of people within Scotland itself that can speak the language is about 57,000 people, or 1.1% of the population [1]. This is indeed a relatively small number, and according to the Endangered Languages Project the language is "Threatened", but the Scottish Government has produced Gaelic Language Plans about every five years since the passage of the Gaelic Language (Scotland) Act 2005. These plans ensure government commitment to the survival and growth of the language, and indeed the decline in speakers has slowed since 2000, and with luck these trends will reverse in the coming years.

In fact, on October 14 of this year, the Scottish Government released an updated language plan outlining the next five years of government initiatives for the language.

But what is this language?

WARNING: INCOMING HISTORY LESSON!

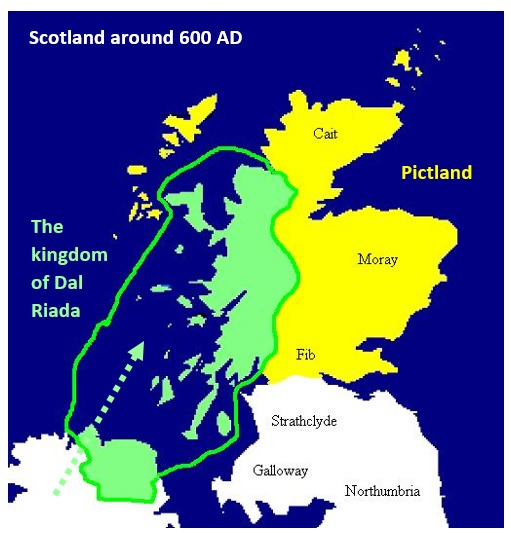

Scottish Gaelic is a Celtic language that was brought to the west coast of Scotland from Ireland by settlers (named "Scoti" by the Romans) sometime between 300 and 500 CE. These settlers soon established the Kingdom of Dál Riata (a name which means "Riata's territory"). This kingdom maintained close ties with Ulster (roughly modern Northern Ireland), and it was during this early period that Christianity began to take hold across Scotland, with such figures as Saint Columba founding monasteries and institutions of learning. What is today Scotland was fractured between four broad people groups at this point - the Gaels in the west, the Picts in the east, the Angles of Northumbria and Berenicia in the southeast, and the Britons of Strathclyde in the south.

With Christianity came the rapid spread of the Gaelic language into lands outside Gaelic control, especially into the Kingdom of the Picts. Eventually, in the 860s-870s, a certain group called the Vikings appeared. (You may have heard of them.) It was at this time that Scotland unified against a common threat, solidifying the bond between the (likely) Brittonic-speaking Picts and the Gaelic-speaking Scots. Over time, Pictish identity was completely lost (leaving behind difficult-to-decipher standing stones scattered across the countryside), and a unified Kingdom of Alba appeared. (Alba means Scotland - and it's not pronounced how you might think.) Between about 1000 and 1200, Gaelic reached its greatest geographic extent, being spoken across Scotland (the islands at this time were ruled by Vikings, which I'll cover in a later post; however, Gaelic was still spoken, at least in the Western Isles). Some people argue that it was never spoken south of Lothian, but place-name evidence from the Borders calls this into question somewhat (name prefixes such as "bal-" and "kil-" are telltale signs of Gaelic settlements).

Malcolm III (of Macbeth fame), also known as Malcolm Canmore ("ceann mòr", or "big head"), married an Anglo-Saxon princess named Margaret, who had no Gaelic. It was at this time, around 1070, that the first signs of a decline in the language began to appear. Margaret brought English-speaking monks to the Lowlands, in effect drawing a cultural border between Lowlands and Highlands.

By the mid-1300s, Scots, a sister language of English (NOT a dialect!), had become the language of the courts and of the parliament. England, in all its ambition, turned its eyes northward, necessitating an independence struggle (or two, or three...), although this resistance was carried out using Scots (then dubbed "Inglis"), not Gaelic (then "Scottis").

By the time the above image was current (c. 1400), Scottish Gaelic had almost completely split away from Irish, though the written languages were (and to a rough extent, still are) rather mutually intelligible.

Over time, Gaelic became further and further marginalized by Scots. Various government initiatives worked expressly against the language, incentivizing or otherwise encouraging Highlanders to speak the "educated tongue" of the Lowlands. In Scots, Gaelic was called "Erse" (roughly, "Irish"), in a popular effort to "de-Scottify" the language. James VI (and I)'s reign marked a significant downturn in the language's usage. The language was seen as backwards, rebellious, and Catholic (a big no-no in an officially Protestant nation). The language was looked down upon in schools (not to mention broader society) from the 1600s up through the early 1900s, and English became the language of upward mobility for Highlanders and Islanders.

Fuadaichean nan Gàidheal, the Highland Clearances, were a result of the failed Jacobite rebellions throughout the 1700s and the imposition of new systems of land management and ownership. Many Highland families emigrated to the far corners of the British Empire, particularly Canada, the United States, Australia, and New Zealand. Highland culture, for all intents and purposes defunct back home in Scotland, survived in these places into the modern era.

In Canada, Gaelic found much success, especially initially. At one point, Gaelic was the third-most commonly spoken language in Canada, though usage declined markedly between the 1800s and more recent revival efforts in the late 20th century. According to the 2011 Canadian Census, 7,195 people claim "Gaelic languages" as the language they use at home (though this term also includes Irish, Welsh, and Breton, the latter two of which are not Gaelic, but Brythonic). Scottish Gaelic is taught in schools (on an opt-in basis) from primary to university level in Nova Scotia, a province whose name means "New Scotland" in Latin. In Nova Scotia, especially on Cape Breton Island, Highland culture is still very much alive.

What goes on within Gaelic?

Gaelic and its other Celtic cousins are quite unique in the European context, as they place the verb first within sentence structure. It's also quite interesting as its nouns can still inflect for the dual number (at least vestigially), a feature lost in a great many other Indo-European languages (oh, did I mention it's an Indo-European language?). If you've ever seen any written Irish or Scottish Gaelic, you may have noticed they like to put "h" after the first letter of a lot of words. This is a linguistic phenomenon known as mutation, and in this case more specifically as lenition. It changes the pronunciation of the first consonant of the word. This phenomenon has been present in the language since the days of Old Irish (and perhaps even further back into the days of Proto-Celtic).

In terms of spelling and pronunciation, it's astonishingly regular... once you figure out all the rules. There are 11-ish vowel sounds (depending on dialect), and 30 (or so) consonant sounds, a step down from Old Irish's 46 distinct consonants.

To conclude:

If you're committed to learning the language, I would recommend finding fellow learners or even native speakers online, and if you're really, REALLY committed to learning the language, I would doubly recommend making the effort to find a tutor in-person or over Zoom or another video calling service if it's within your means (although this advice goes without saying for learning any language). An institution known as Sabhal Mòr Ostaig, based in the Isle of Skye in the Western Isles of Scotland, must be mentioned in any discussion about learning Gaelic, however. According to their website, they are the "only centre of Higher and Further Education in the world that provides its learning programmes entirely through the medium of Gaelic in an immersed, language-rich environment." (This post is not sponsored.) If you have the time, the money, and the willpower, perhaps give them a look! They work closely with projects such as Tobar an Dualchais and Soillse to preserve, maintain, and revitalize Gaelic language and culture for future generations.

Follow for more linguistics and share this post! If you have any questions, feel free to ask!

#scotland#scottish#gaelic#irish language#scottish gaelic#indo european#linguistics#language#history#culture#celtic#celts#vikings

313 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is the first English translation of Jangar, the heroic epic of the Kalmyk nomads [...]. A tribute to [...] the mythical country Bumba, Jangar reflects the hopes and aspirations of the Kalmyk people as well as their centuries-long struggle for their cultural existence. Saglar (Saga) Bougdaeva was born and raised in Kalmykia. Central to Bougdaeva’s work as a scholar of the Eurasian studies is a commitment to identifying and preserving the nomadic oral and written heritage of the Great Eurasian Steppe. Before receiving a PhD in Sociology from Yale University, Bougdaeva studied Mongolian-Tibetan-Mandarin linguistics at Saint Petersburg State University. [...]

I grew up in the Republic of Kalmykia, a Mongolic-speaking region on the Volga River and Caspian Sea. In ancient and medieval times, Kalmyks were called Oirads. From the nomadic perspective, this location was the most western post of the Eurasian steppe road. [...]

If we think beyond the recent modernist and nationalist [...] terms and expand our time frame, Kalmykia is located at the point where west meets east and east meets west. [...] Oirad nomads easily crossed manmade borders not only geographically, but also conceptually and linguistically. All their aesthetic creations were valuable for that capability of polyglossia. They absorbed a myriad of influences without losing their own nomadic core, forming a multi-cultural buffer zone along the Eurasian steppe.

There are many perspectives on this particular region and field, but what is missing are the voices of the nomads themselves. [...]

---

It is widely assumed that nomads were neither aesthetically developed nor literate. I disagree with that position. When I read Jangar, I heard nomadic voices of heroic humans, horses, birds, half-human giants, and semi-gods. I found my comfort in nomadic shelters [...]. I visited nomadic cities, bazaars and public plazas for meetings and festivals [...]. I travelled through the roads with planted poplar trees that connected seventy khanates [...]. Clearly the social worlds of nomads were very different from what is generally known about them. [...]

What we know about the vast territories and populations across the Eurasian steppe road, from the wall of Beijing to the wall of Berlin, is in the hands of the Russian government. Our knowledge about existing polities is scarce, and our knowledge about destroyed nomadic polities is even more threatened.

There is a link between literature and political freedom. [...]

---

Jangar is a meditative imagination. As in dreams, there is not a strong sense of time. In the absence of time, movement is captured in relation to memorable events, such as a compelling call for a heroic act. In reading Jangar, our mind merges with a hero, who is a moving point in space; they become a hero while navigating the Eurasian steppe road. Along this road, which stretches between the Mingi (Caucasus) and the Ganga (Ganges), the epic pinpoints the Altai Mountains as the original homeland of the Oirad-Kalmyks. [...]

Jangar is very much about feelings and sensibilities. My favorite feeling from the book is the sense of freedom of global travels, from east to west and back again. This archaic language allows us to become witnesses to the global movement along the Great Steppe Road. The quintessential elements of this exciting global flow of people were groundwater well (ulgen) stops, “tea and sleep” (chai-honna) stops, diners (khotan), soup kitchens (sholun) for monks and the poor, horse-exchange and postal stations (yam), watchtowers and storm shelters (bolzatin boro), golden and silver bridges over rivers, and jade gates marking the entrances and exits of khanates. [...]

---

Jangar was expressed by heart and memory. Treasures of nomadic art and literature were expressed in ways that made sense to nomadic cultures but are unexpected for a modern reader. For example, if you decide to live in a mobile home called ger, it makes more sense to leave wall paintings behind and bring exquisite carpet art, which you can roll out and find more value in its utility.

Similarly, if treasures of “literature” are not written with black ink on white paper, but express an exquisite aesthetic of creative narration, shouldn’t we celebrate it based on its brightness and not its format?

Today, the problem with our definition of literature is its focus on written works. It means we often throw out whatever is outside of that frame. Jangar is only one of many examples of what we have almost lost.

---

Words of: Saglar Bougdaeva. “Q&A with Saglar Bougdaeva, translator of Jangar.” UC Press Blog (University of California Press). 5 March 2023. [Bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me. The first paragraph in this post was published as a sort of introduction along with the article, and I’ve italicized to distinguish it from Bougdaeva’s responses and identify them as the words of UC Press Blog interviewers/editors.]

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

At the National Opera of Ukraine in Kyiv recently, I watched a performance of an opera by the Ukrainian composer Mykola Lysenko. The work, charming and comic and an escape from the grimness of Russian missile attacks, is called Natalka Poltavka, based on a play by Ivan Kotliarevsky, who pioneered Ukrainian-language literature in the late-18th and early-19th centuries. Operas by Verdi, Puccini and Mozart, and ballets such as Giselle and La Sylphide, are on the playbill, despite the almost daily air raid sirens. But there is no Eugene Onegin in sight, nor a Queen of Spades, and not a whisper of those Tchaikovsky staples of ballet, Sleeping Beauty or Swan Lake. Russian literature and music, Russian culture of all kinds, is off the menu in wartime Ukraine. It is almost a shock to return to the UK and hear Russian music blithely played on Radio 3.

This absence, some would say erasure, can be hard to comprehend outside Ukraine. When a symphony orchestra in Cardiff removed the 1812 Overture from a programme this spring, there was bafflement verging on an outcry: excising Tchaikovsky was allowing Vladimir Putin and his chums the satisfaction of “owning” Russian culture – it was censorship, it was playing into Russia’s hands. Tchaikovsky himself was not only long dead, but had been an outsider and an internationalist – so the various arguments went. It took some careful explanation to convey that a piece of music glorifying Russian military achievements, and involving actual cannons, might be somewhere beyond poor taste when Russia was at that moment shelling Ukrainian cities – particularly when the families of orchestra members were directly affected.

In fact, such moments have been rare in western Europe. Chekhov and Lermontov continue to be read and Mussorgsky to be performed. Russian culture has not been “cancelled” as Putin claims, and Russian-born musicians and dancers with international careers continue to perform in the west – assuming they have offered a minimum of public deprecation of the killing and destruction being visited on Ukraine. Only the most naive would decry the removal of Valery Gergiev from international concert programmes. The conductor, who is seen as close to Putin, backed the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014 (unrecognised by most UN countries), has declined to condemn the current full-scale invasion of Ukraine, and has a history of using his artistic profile in the service of the Russian state, such as conducting concerts in Russian-backed South Ossetia in 2008 in the wake of the Russo-Georgian war.

Inside Ukraine, though, things look very different. For many, the current war with Russia is being seen as a “war of decolonisation”, as Ukrainian poet Lyuba Yakimchuk has put it – a moment in which Ukraine has the chance to free itself, at last, from being an object of Russian imperialism. This decolonisation involves a “total rejection of Russian content and Russian culture”, as the writer Oleksandr Mykhed told the Lviv BookForum recently. These are not words that are comfortable to hear – not if, like me, you spent your late teens immersed in Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina and Chekhov stories; not if you have recently rekindled your love of Russian short fiction via George Saunders’ luminous book, A Swim in the Pond in the Rain; not if you adore Stravinsky and would certainly be taking a disc of The Rite of Spring to your desert island.

The context for this rejection has to be understood, though: Ukrainians are emerging from a history in which the Russian empire, and then the Soviet Union, actively and often violently suppressed Ukrainian art. This has worked in a number of different ways. It has included the absorption of numerous Ukrainian artists and writers into the Russian centre (such as Nikolai Gogol, or Mykola Hohol in Ukrainian), and the misclassifying of hundreds of artists as Russian when they could arguably be better described as Ukrainian (such as the painter Kazimir Malevich, who was Kyiv-born but Russian, according to the Tate). It has meant that writing in Ukrainian has at times been proscribed – Ukraine’s national poet, Taras Shevchenko, was banned from writing at all for a decade by Tsar Nicholas I. This silencing has encompassed the extermination of Ukrainian artists, like the killing, under Stalin, of hundreds of writers in 1937, known as “the executed renaissance”. Behind all of this stands horrific events such as the Holodomor, the starvation of about 4.5 million Ukrainians in 1932-33 in their forced effort to produce grain on Stalin’s orders.

This history places Ukraine in a very different position in relation to Russian culture than, say, Britain found itself in relation to German and Austrian art during the second world war, when Myra Hess programmed Mozart, Bach and Beethoven in her National Gallery concerts during the Blitz. “We have had cultural occupation, language occupation, art occupation and occupation with weapons. There’s not much difference between them,” the composer Igor Zavgorodniy tells me. In the Soviet period, Ukrainian culture was allowed to be harmlessly folksy – and Ukrainians, caricatured as drunken yokels dressed in Cossack trousers, were often the butt of belittling jokes. But Ukraine was not expected or allowed to carry a high culture of its own. At the same time, Russian artistic achievement was lauded as the very apex of human greatness. “We were raised in a certain piety towards the Russian literature,” explains the playwright Natalya Vorozhbit, who was educated in the Soviet period. “There wasn’t such piety towards any other literature.”

Putin himself has effectively doubled down on all this through his constant insistence, in his essays and often rambling speeches, that Ukraine has no separate existence from Russia – no identity, no culture at all, except as an adjunct of its neighbour. Indeed, his claim of Russia’s cultural inseparability from Ukraine is one of his key justifications for invasion. At the same time the Russian instrumentalisation of its artistic history is breathtakingly blatant. In occupied Kherson, billboards proclaiming it as a “city with Russian history”, show an image of Pushkin, who visited the city in 1820. Ukrainian artists also object to how, in a more general way, the projection of Russia as a great nation of artistic brilliance operates as a tool of soft power, a kind of ambient hum of positivity that, they would argue, softens the true brutality of today’s invasion. In Ukraine, there is a generalised cry of “bullshit” in relation to the myth of the “Russian soul”.

Some Ukrainians I speak to hope that one day, beyond the end of the war, there will be a way of consuming Russian literature and music – but first the work of decolonisation must be done, including the rereading and rethinking of classic authors, unravelling how they reflected and, at times, projected the values of the Russian empire. In the meantime, “My child will be perfectly all right growing up without Pushkin or Dostoevsky,” says Vorozhbit. “I don’t feel sorry.”

For many Ukrainians I encounter, the time for Russian literature will come again – when it can be critically understood as simply another branch of world culture, and as neither an unduly oppressive, nor overwhelming, force. At the National Opera House, I ask the choreographer Viktor Lytvynov when he thinks Tchaikovsky – a composer he loves – will be back on the programme. “When Russian stops being an aggressor,” he says. “When Russia stops being an evil empire.”

70 notes

·

View notes

Note

https://www-bbc-co-uk.cdn.ampproject.org/v/s/www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-devon-66981924.amp?amp_gsa=1&_js_v=a9&usqp=mq331AQGsAEggAID#amp_tf=From%20%251%24s&aoh=16963221914273&csi=0&referrer=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.google.com

If I saw this on another site I would have thought it was satirical, but I don't think BBC News does Satire!

By: BBC News

Published: Oct 3, 2023

A degree in magic being offered in 2024 will be one of the first in the UK, the University of Exeter has said.

The "innovative" MA in Magic and Occult Science has been created following a "recent surge in interest in magic", the course leader said.

It would offering an opportunity to study the history and impact of witchcraft and magic around the world on society and science, bosses said.

The one-year programme starts in September 2024.

Academics with expertise in history, literature, philosophy, archaeology, sociology, psychology, drama, and religion will show the role of magic on the West and the East.

The university said it was one of the only postgraduate courses of its kind in the UK to combine the study of the history of magic with such a wide range of other subjects.

'Place of magic'

Prof Emily Selove, course leader, said: "A recent surge in interest in magic and the occult inside and outside of academia lies at the heart of the most urgent questions of our society.

"Decolonisation, the exploration of alternative epistemologies, feminism and anti-racism are at the core of this programme."

The course will be offered in the Institute of Arab and Islamic Studies.

Prof Selove said: "This MA will allow people to re-examine the assumption that the West is the place of rationalism and science, while the rest of the world is a place of magic and superstition."

The university said the course could prepare students for careers in teaching, counselling, mentoring, heritage and museum work, work in libraries, tourism, arts organisations or the publishing industry, among other areas of work.

A choice of modules includes dragons in western literature and art, the legend of King Arthur, palaeography, Islamic thought, archaeological theory and practice and the depiction of women in the Middle Ages.

==

I mean, it could have been quite good, the history of magic; the effect on human imagination and storytelling; magic in literature and art; magic as metaphor for what we don't know, a stand-in for science; the evolution of societal perceptions of magic through the growth of the scientific method; the role of magic and revelation in early epistemological (truth claims) processes... this could have been a fascinating course.

Then they had to ruin it by stuffing it full of intersectional Gender Studies horseshit and making it ideologically corrupt and completely academically worthless. Except to piss off daddy, who's paying the bill.

This is the exact kind of luxury course that only bored, privileged, upper-middle class people with no real problems or ambition would take. If you take it, you have nothing better to do, and no ambition to better your future prospects. It's low-effort, academically shallow, fosters undeserved moral elitism, but still takes in tuition fees, so it's unsurprising that it exists.

You'd be getting loan forgiveness for it over my dead body, though.

#ask#Degree in Magic#Exeter University#gender studies#intersectionality#intersectional feminism#intersectional religion#religion is a mental illness

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Intro: Favorite Mongolian Authors & more

#slavic roots western mind

I've always had an interest in Mongolia, primarily because there's literally so little international news coverage, at least in my neck of the woods so to speak.

Despite my Mongolian language learning attempts being paused for the time being, I nonetheless continue to fall in love with Mongolian literature with every read, especially with poetry, which is why I've wanted to share my favourite authors.

Here's my quick list of Mongolian authors who's works I've read so far (and a few that are on my to-read radar).

1. Galsan Tschinag

My absolutely favorite poet, born in Mongolia in 1944, famous for his poetry, which interestingly enough was originally written in German, and then translated to English.

His works primarily feature the themes of a nomadic lifestyle, nature, heritage and cultural identity, so if any of these topics interest you, definitely check out his works!

2. Chadraabalyn Lodoidamba

I've only managed to read one of his novels "Тунгалаг тамир" (The Crystal Clear Tamir River), but it's definitely a worthwhile read. Set in the 20th Century, it provides an interesting insight into Mongolian history leading up to the uprising of Mongolia in 1932, with a strong focus on the struggle of the poor against the rich

There's no official English translation (there are German and Russion versions somewhere, but I didn't find them yet), but google translate helped me create a readable version from the original Mongolian.

There's also a movie split into several episodes avaliable on yt but with iffy subtitles, so if you liked the book, you can sort of follow along with the movie.

It's rare for me to hear spoken Mongolian, so watching the movie episodes has been a fascinating experience.

3. Choinom Ryenchi

Once again, I've only read one of this authors works "Buriad", written in 1973 and published in Sümtei Budaryn Chuluu [A Stone from the Steppe with a Monastery] in 1990, but it was enough to interest me.

Buriad refers to an ethnic group in Mongolia, with the poem describing their lifestyle and history. I don't know if what I've read is the entire work, as I found it in a research paper, feauturing said poem with the translation, but it was still quite beautiful.

The style is very lyrical, almost like a song or even a chant at times, and very captivating. A must-read.

4. Mend-Ooyo Gombojav

He has written quite a lot of novels, with many of them luckily translated into English.

His "The Holy One" is a great work of historical fiction, about a 19th century poet and teacher of Buddhism, whose memory and works were later persecuted by the governments fight against intellectuals and free-thinkers, all whilst his works protector attempted to save his works.

Unfortunately I've only read excerpts and bits and pieces, which is pretty frustrating because it seems so good? The style is unusual for me, but it's pretty great either way.

I've read the peom "The Way of the World", which has a rather nostalgic vibe, remembering the past warriors and their heroic deeds but also suggesting that only the stories of their victories will remain. Short but "sweet".

5. Oyungerel Tsedevdamba

I only know her "The Green-eyed Lama", co-written by her and her husband Jeffrey Lester Falt, but the plot description is enough to have me hooked. A love triangle, love and faith amidst war and rebellion... Here's me hoping that it won't be a tear-jerker, because sad endings are not my favorite genre.

Here's a link to a video about Oyungerel's and Jeffrey's writing and research process and how they wrote the novel. It's actually based on a true real-life story, so I guess I'll see how reading this novels turn out. History isn't exactly known for it's happy endings, so we shall see.

6. Combo: Mongolian Short Stories

This one is a compilation of short stories by various Mongolian authors rather than just one author, but it'll have to do because Number 6 exhausts all my knowledge of Mongolian literature.

Edited and compiled by Henry G. Schwarz, each story is about 4-15 pages long with different themes, ranging from daily life in rural Mongolia to critiques of the political situation at the time, the style is a tad over the place, as each author has their own distinct style. Nonetheless, this book gives interesting insights into what life was like in Mongolia at the time, and whether our notions and initial ideas about Mongolia reflect the literary depictions.

Here's my list so far, but chances are I'll update it soon, so watch out for any new updates!

I'll happily share any links and digital copies of these works that I have, just message me please!

#college life#literature#book blr#study blr#light academia#mongolia#slavic roots western mind#Mongolian literature#student life#student

8 notes

·

View notes