#telegraph wire

Text

young lex luthor looking exactly like tintin sure is something.

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

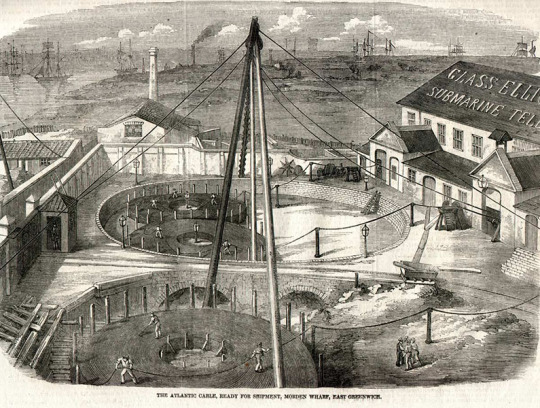

George Elliot – Scientist of the Day

George Elliot, an English manufacturer, was born Mar. 18, 1814.

read more...

#George Elliot#transatlantic cable#wire rope#telegraph#histsci#histSTM#19th century#history of science#Ashworth#Scientist of the Day

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

January 2007 PDX Portland Oregon U.S.A.

■Calendar of 2022 December

© KOJI ARAKI Art Works

#2007#January 2007#PDX#Portland#Oregon#Calendar of 2022 December#Calendar#2022 December#2022#neighborhood#Mt Foot#roadside tree#tree#street light#electrical wires#telegraph pole#photographers on tumblr#original photography#b&w photography#black and white photography#photography#koji araki art works#street photography#PENTAX *istD#smc PENTAX-FA* 80-200mm F2.8 ED[IF]#PENTAX

160 notes

·

View notes

Text

Telegraph pole getting in a twist over the electrics.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

photos.billsmugs.com

#original photographers#photography#photographers on tumblr#telegraph pole#communication#wires#cables

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Starlings taking advantage of phone lines at Cleveleys. Copper wires are to be retired over the next few years, so the starlings will have to use fibre broadband lines.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I made a post about this somewhere on my main but I can't find it so here I go again-

In the setting of Skysail there is little-to-no infrastructure for electrical power. No lightbulbs, generators, heating elements, that sort of stuff.

This is directly because of more frequent and intense solar flares making that sort of technology way more unreliable.

But you know what's way more resistant to being disrupted by solar flares? Living things.

This has led several worlds in the setting to invest in Fucked Up Meat Science. Other worlds do not like this, if you can believe it.

Oh and this also extends to plant life. Small livestock population? Hunters didn't bring in enough food? That's fine just harvest one of the Meat Trees.

#ramblings#skysail#body horror#kinda?#the vibe im going for is like. the Leviathan series#sometimes you're full on fusing DNA together to get a literal living breathing airship#othertimes you're just growing some nerves in a petri dish to act like wires so you can send a telegraph#Jovian nobility clutching their pearls about it but they cant enjoy near-instant communication without risking The Radio Ghosts

0 notes

Text

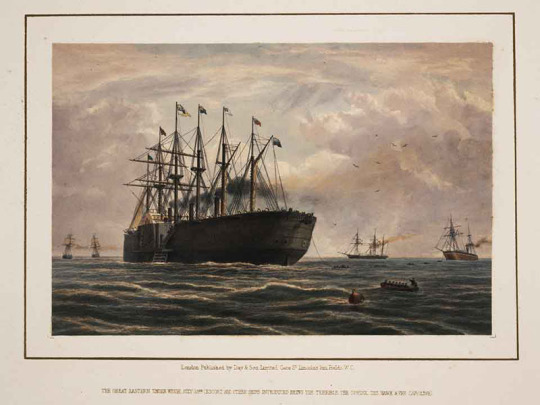

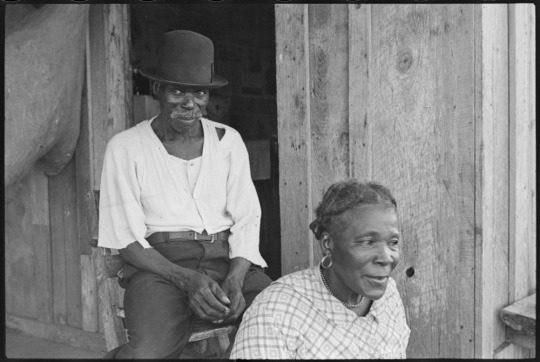

Sharecropping: Slavery Rerouted

Though slavery was abolished in 1865, sharecropping would keep most Black Southerners impoverished and immobile for decades to come.

— Published: August 16, 2023 | By Jared Tetreau | The Harvest: Integrating Mississippi's Schools | Article | Sunday August 20, 2023

Sharecropper's children. Montgomery County, Alabama, 1937, photographer Arthur Rothstein, Library of Congress

“The White Folks had all the Courts, all the Guns, all the Hounds, all the Railroads, all the Telegraph Wires, all the Newspapers, all the Money and nearly all the Land – and we had only our Ignorance, our Poverty and our Empty Hands.” — an anonymous Sharecropper, Elbert County, Georgia, ca. 1900

On January 1, 1867 in Marshall County, Mississippi, Cooper Hughes and Charles Roberts entered into an agreement. In their contract with landowner I.G. Bailey, Hughes and Roberts, both formerly enslaved men, agreed to work 40 acres of corn and 20 acres of cotton on Bailey’s land, along with “all other work…necessary to be done to keep [the farm] in good order,” for the duration of 1867. In exchange for their labor, Hughes, Roberts and their families would be “furnished” with stipends of meat, a mule for plowing, a plot of land to grow a garden, separate cabins and one-third and one-half of the corn and cotton crops respectively.

On that first day of 1867, Hughes and Roberts joined a growing number of newly freed African Americans turning toward a new agricultural arrangement in the South. It would come to be called “sharecropping.” In the decades that followed, sharecropping would grow into what scholar Wesley Allen Riddle called the “predominant capital-labor arrangement” in the region, defining how hundreds of thousands of Black Southerners made a living and supported their families. But once up and running, sharecropping itself would deny the formerly enslaved their rights and liberties as free American citizens for nearly one hundred years.

Sharecropper "Mother Lane" Pulaski County, Arkansas,1937, United States Resettlement Administration, photographer Ben by Shahn, Library of Congress

What is Sharecropping?

Sharecropping is a system by which a tenant farmer agrees to work an owner’s land in exchange for living accommodations and a share of the profits from the sale of the crop at the end of the harvest.

The system emerged after the Civil War, when the southern economy lay in ruins. With the Confederate monetary system wiped out, farm land decimated, and slavery abolished under the 13th Amendment, access to labor and capital was extremely limited among Southern landowners. For former slaves, federal proposals to redistribute land fell apart in the 1860s, leaving millions without the promises of full citizenship guaranteed to them by the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments.

Pitched as a solution for both groups, sharecropping was presented to the formerly enslaved as land ownership by proxy. It put an end to work in “gangs” under an overseer, while keeping Black workers within the agricultural sector, preferably on the same land where they had been held captive, and incentivizing high crop yields, benefitting landowners. But even though the old plantation system had changed and some day-to-day activities were delegated to sharecroppers, sharecropping proved a fundamentally unequal arrangement, organized to keep Black farmers from ever achieving economic or social mobility.

As writer Doug Blackmon notes, many white southerners after Emancipation were determined not to pay for something they had once had for free—Black labor.

Many landowners at the end of the Civil War were furious at the idea of paying Black workers whom they’d owned only months before. As a result, landowners developed systems adjacent to slavery. On the plantations, this took the form of sharecropping, though the transformation did not happen overnight.

Black Americans in the South were eager to exercise their newfound freedoms after the war. As historian Wesley Allen Riddle writes, “the most basic and symbolic” of these freedoms was “mobility” itself. The formerly enslaved left their plantations in droves, some looking for work in the South’s devastated cities, while others looked for—and were given by the Union Army—vacant land on which to raise a farm. But work in cities was hard to come by. Only about 4 percent of Freedmen were able to find work in southern cities after the war, and many who came there were relegated to shantytowns of the formerly enslaved. As for those that were given vacant lands by the army, they were forced out when President Andrew Johnson canceled Field Order No. 15 in the fall of 1865, returning these properties to their white owners.

While many formerly enslaved did leave the plantations after the war, many others could not. Those trying to leave faced horrific violence and intimidation from their former owners. As Union General Carl Schurz reported in his testimony to Congress in 1865, “In many instances, negroes who walked away from plantations, or were found upon the road, were shot or otherwise severely punished.”

With land ownership all but closed to them, and urban service work extremely limited, many Freedmen had little choice but to return to the plantations by the end of the 1860s. Their motives for this were mixed. Though economic pressures were strong, many wanted to reunite with loved ones who had been sold during slavery, and saw some appeal in working in an agricultural sector that they were familiar with.

Twenty to 50 acre plots, a cabin to live in and farming supplies were promised to them, all in exchange for about 50 percent of their harvest. Freedmen envisioned a self-sustained life working a plot of land, raising a garden, and providing for their families as they wanted. But these hopes were dashed as the pitfalls of sharecropping quickly became clear.

Sharecroppers, Pulaski County, Arkansas. 1937, photographer Ben by Shahn, United States Resettlement Administration, Library of Congress

Life as a Sharecropper

By design, sharecropping deprived Black farmers of economic agency or mobility. Although they were no longer legally enslaved, sharecroppers were kept in place by debt. As their income was dependent on both the profits from the sale of the crop and the whims of the landowners, sharecroppers had to find means to sustain themselves during the rest of the year. They were forced to purchase food, seed, clothing and other goods on credit, typically from a plantation “commissary” owned by the landlord.

At the end of the harvest, when revenue from the crop was “settled up,” the sharecroppers’ portion of the profits was calculated against their debts. As a result, sharecroppers often ended the year owing their landlords money. What could not be paid off was carried into the next year, creating a cycle of indebtedness that was often impossible to break.

Sharecroppers in debt to their landlord were subject to laws that tied them to the land. If they attempted to move, any new tenancy contracts they signed with other landlords could be voided by their existing ones. If they ran away, they could be brought back to their landlord in chains, and made to work as a prisoner for no pay at all.

Even if sharecroppers did not try to leave, they still faced massive obstacles in achieving any kind of solvency. For instance, many Southern states limited how and to whom sharecroppers could sell their part of the crop. In Alabama, cotton had to be sold and transported during the day, and could only be purchased by a state-defined “legitimate” merchant. As sharecroppers couldn’t afford to lose a day’s work to take their crop to market, these laws curtailed their ability to sell their product at the best possible price.

In addition, individual freedoms were crushed by tenancy contracts, many of which included arbitrary clauses forbidding alcohol consumption, speaking to other sharecroppers in the fields or allowing visitors on rented land.

Black sharecroppers could not seek redress through the political system either. Despite the ratification of the 14th and 15th Amendments, the southern “Redemption” that followed the withdrawal of Union troops from the South in 1876-7 ensured that the federal government would not enforce Black voting rights. Black elected officials disappeared from Congress and state legislatures, and attempts at organizing Black voters were brutally suppressed, as in New Orleans in July of 1866, where a convention of Black voters was attacked by a white mob under police protection that killed an estimated 200 people.

Educational opportunities were also sparse. In 1872, white Southerners pressured Congress to abolish the Freedmen's Bureau, a federal agency designed to provide food, shelter, clothing, medical services and land to newly freed African Americans. With the dissolution of the Bureau, few resources remained for the approximately 80 percent of Black people who were illiterate.

Sharecropping, with its prohibitive restrictions on physical and economic mobility, its use of violence and intimidation and its emphasis on maximum production, denied Black Southerners the ability to gain wealth, to exercise the freedom granted them by Emancipation and to gain the education they were deprived of during enslavement. The system existed, in conjunction with other institutions, to exploit Black labor at a minimum “relative loss” to white landowners while keeping the Black population underfoot.

As Black sharecropper Ed Brown said of his experience, “hard work didn’t get me nowhere.”

Sharecropper's cabin, Southeast Missouri Farms. 1938, photographer Russell Lee, Library of Congress

Sharecropping’s Decline and Legacy

After dominating the southern agricultural economy for decades, sharecropping was, like most other farming practices, upended by the rise of new technologies. While these changes were delayed by the Great Depression, sharecropping had become obsolete in many areas of the South by the mid-twentieth century. With increased mechanization, white planters’ demand for Black labor dried up.

Also during this time, Jim Crow obstructions to Black enfranchisement, as well as state-sanctioned violence against Black people, were directly challenged by the Civil Rights Movement and the landmark legislation it helped enact. The Civil Rights Acts of 1964 and 1968 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 deconstructed de jure segregation across the South in housing and public accommodation, while empowering the federal government to secure the right to vote for Black Southerners.

As scholars Paru Shah and Robert S. Smith note, enfranchisement, desegregation and the decline of sharecropping weakened “the broader agenda of White Supremacy to crush African American socioeconomic mobility,” but did not destroy it. The effects of centuries of Black economic and social oppression, represented in part by sharecropping, are still felt today. Limited access to capital, to mobility, and to representation during Jim Crow and before it denied Black Americans the ability to save, invest or accumulate wealth, concentrating inherited fortunes in the hands of white families and shaping the present class makeup.

For nearly a century, sharecropping defined Southern agriculture and hindered Black economic advancement. The system reflected a multidude of attempts by the white power structure to keep Black workers stagnant, achieving this through intimidation, physical violence and exploitation. Ultimately, aided by organized action, shifting technological and economic conditions and the determination of sharecroppers themselves, the oppressive reality of sharecropping ended. But in the endemic inequities of American political and economic life, its legacy persists.

#NOVA | PBS#Sharecropping#Slavery Rerouted#Black Southerners#The Harvest#Integration#Mississippi's Schools#Jared Tetreau#Article#White Folks | Possessor of Courts | Guns | Railroads | Telegraph Wires | Newspapers | Money | Land#Marshall County | Mississippi#Cooper Hughes | Charles Roberts#Landowner | I.G. Bailey#Sharecropper | Ignorence | Poverty | Empty Hands#African Americans#Civil War#Confederate Monetary System#Doug Blackmon#Emancipation#Historian | Wesley Allen Riddle#Union General Carl Schurz#Southern States | Alabama#Redemption#Educational Opportunities#Freedmen's Bureau#Black Sharecropper | Ed Brown#Civil Rights Movement#Civil Rights Acts of 1964 & 1968 | Voting Rights Act of 1965#Scholars: Paru Shah | Robert S. Smith

0 notes

Video

youtube

Steven Crowder EXPOSES Daily Wire Contract in "it's time to stop..."

#youtube#louder with crowder#crowder#the daily telegraph#the daily wire#conservatives#liberals#republicans#democrats#big con#conservative media#broadcasting#liberal media#libs#andrew tate#ben shapiro#joe biden#donald trump#hunter biden#react video#reaction#funny#self own#conservative self own#hilarious#comedy#politics#political comedy#political reactions#political discussion

0 notes

Text

something that will remain eternally funny to me is how they FINALLY debut booster gold in legends of tomorrow after years of playing tug-o-war with DC entertainment because michael seem to ALWAYS have upcoming projects springing up and they always fall apart. on the very finale that michael debuts, the show immediately gets cancelled. YOU! ARE! CURSED! MICHAEL!

#and yet i will remain his faithful fan#booster gold#michael jon carter#legends of tomorrow#telegraph wire

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

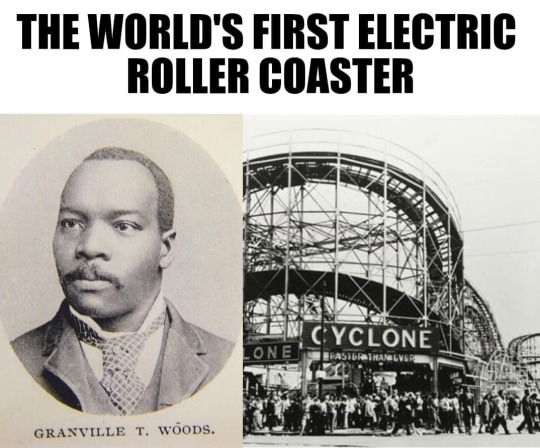

THE WORLD'S FIRST ELECTRIC ROLLER COASTER

Granville T. Woods (April 23, 1856 – January 30, 1910) introduced the “Figure Eight,” the world's first electric roller coaster, in 1892 at Coney Island Amusement Park in New York. Woods patented the invention in 1893, and in 1901, he sold it to General Electric.

Woods was an American inventor who held more than 50 patents in the United States. He was the first African American mechanical and electrical engineer after the Civil War. Self-taught, he concentrated most of his work on trains and streetcars.

In 1884, Woods received his first patent, for a steam boiler furnace, and in 1885, Woods patented an apparatus that was a combination of a telephone and a telegraph. The device, which he called "telegraphony", would allow a telegraph station to send voice and telegraph messages through Morse code over a single wire. He sold the rights to this device to the American Bell Telephone Company.

In 1887, he patented the Synchronous Multiplex Railway Telegraph, which allowed communications between train stations from moving trains by creating a magnetic field around a coiled wire under the train. Woods caught smallpox prior to patenting the technology, and Lucius Phelps patented it in 1884. In 1887, Woods used notes, sketches, and a working model of the invention to secure the patent. The invention was so successful that Woods began the Woods Electric Company in Cincinnati, Ohio, to market and sell his patents. However, the company quickly became devoted to invention creation until it was dissolved in 1893.

Woods often had difficulties in enjoying his success as other inventors made claims to his devices. Thomas Edison later filed a claim to the ownership of this patent, stating that he had first created a similar telegraph and that he was entitled to the patent for the device. Woods was twice successful in defending himself, proving that there were no other devices upon which he could have depended or relied upon to make his device. After Thomas Edison's second defeat, he decided to offer Granville Woods a position with the Edison Company, but Woods declined.

In 1888, Woods manufactured a system of overhead electric conducting lines for railroads modeled after the system pioneered by Charles van Depoele, a famed inventor who had by then installed his electric railway system in thirteen United States cities.

Following the Great Blizzard of 1888, New York City Mayor Hugh J. Grant declared that all wires, many of which powered the above-ground rail system, had to be removed and buried, emphasizing the need for an underground system. Woods's patent built upon previous third rail systems, which were used for light rails, and increased the power for use on underground trains. His system relied on wire brushes to make connections with metallic terminal heads without exposing wires by installing electrical contactor rails. Once the train car had passed over, the wires were no longer live, reducing the risk of injury. It was successfully tested in February 1892 in Coney Island on the Figure Eight Roller Coaster.

In 1896, Woods created a system for controlling electrical lights in theaters, known as the "safety dimmer", which was economical, safe, and efficient, saving 40% of electricity use.

Woods is also sometimes credited with the invention of the air brake for trains in 1904; however, George Westinghouse patented the air brake almost 40 years prior, making Woods's contribution an improvement to the invention.

Woods died of a cerebral hemorrhage at Harlem Hospital in New York City on January 30, 1910, having sold a number of his devices to such companies as Westinghouse, General Electric, and American Engineering. Until 1975, his resting place was an unmarked grave, but historian M.A. Harris helped raise funds, persuading several of the corporations that used Woods's inventions to donate money to purchase a headstone. It was erected at St. Michael's Cemetery in Elmhurst, Queens.

LEGACY

▪Baltimore City Community College established the Granville T. Woods scholarship in memory of the inventor.

▪In 2004, the New York City Transit Authority organized an exhibition on Woods that utilized bus and train depots and an issue of four million MetroCards commemorating the inventor's achievements in pioneering the third rail.

▪In 2006, Woods was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

▪In April 2008, the corner of Stillwell and Mermaid Avenues in Coney Island was named Granville T. Woods Way.

473 notes

·

View notes

Photo

January 2023

Today 20230101SUN

first sunrise of 2023

Happy New Year 2023😁🙏✨

May this year be filled with happiness for you and the world✨

© KOJI ARAKI Art Works

Daily life and every small thing is the gate to the universe :)

#2023#January 2023#Today#Today 20230101SUN#sunrise#first sunrise#sky#cloud#sun#sunlight#telegraph pole#electrical wires#photographers on tumblr#b&w photography#black and white photography#original photography#photography#koji araki art works#PENTAX K1#SIGMA 15mm 2.8 EX Fisheye#Fisheye#SIGMA#PENTAX

82 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Joseph “Uncle Joe” Clovese was the last known surviving African soldier of the Union Army in the American Civil War, and lived in Pontiac at the time of his death in 1951. Clovese, who lived to be 107 years old, was born into slavery on a plantation in St. Bernard Parish, Louisiana, and escaped slavery in his teens to join the Union Army during the Siege of Vicksburg. He stayed with the Northern Army, first as a drummer, later as an infantryman. He was a private in Co. "C", 63rd Colored Infantry Regiment.

Following the war he worked on Mississippi river steamboats, and he later worked on the crew stringing the first telegraph wires between New Orleans and Biloxi, Mississippi. At the age of 104, Clovese moved from Louisiana to Pontiac, Michigan to be near family. Once the community learned about “Uncle Joe,” the citizens of Pontiac embraced him. Large gatherings were organized for his 105th, 106th and 107th birthdays on January 30th.

For his funeral, more than 300 people were packed into Newman A.M.E. Church in Pontiac (their former location, in downtown) for the service. Hundreds more gathered at the gravesite in Pontiac’s Perry Mount Park Cemetery. Veterans from the Oakland County Council of Veterans served as pall bearers. A firing party from Selfridge Air Force Base fired the final salute and taps was sounded over the cemetery. Pontiac even named a road in his honor, that ran through the Lakeside Homes complex.

451 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE WORLD'S FIRST ELECTRIC ROLLER COASTER

Granville T. Woods (April 23, 1856 – January 30, 1910) introduced the “Figure Eight,” the world's first electric roller coaster, in 1892 at Coney Island Amusement Park in New York. Woods patented the invention in 1893, and in 1901, he sold it to General Electric.

Woods was an American inventor who held more than 50 patents in the United States. He was the first African American mechanical and electrical engineer after the Civil War. Self-taught, he concentrated most of his work on trains and streetcars.

In 1884, Woods received his first patent, for a steam boiler furnace, and in 1885, Woods patented an apparatus that was a combination of a telephone and a telegraph. The device, which he called "telegraphony", would allow a telegraph station to send voice and telegraph messages through Morse code over a single wire. He sold the rights to this device to the American Bell Telephone Company.

In 1887, he patented the Synchronous Multiplex Railway Telegraph, which allowed communications between train stations from moving trains by creating a magnetic field around a coiled wire under the train. Woods caught smallpox prior to patenting the technology, and Lucius Phelps patented it in 1884. In 1887, Woods used notes, sketches, and a working model of the invention to secure the patent. The invention was so successful that Woods began the Woods Electric Company in Cincinnati, Ohio, to market and sell his patents. However, the company quickly became devoted to invention creation until it was dissolved in 1893.

Woods often had difficulties in enjoying his success as other inventors made claims to his devices. Thomas Edison later filed a claim to the ownership of this patent, stating that he had first created a similar telegraph and that he was entitled to the patent for the device. Woods was twice successful in defending himself, proving that there were no other devices upon which he could have depended or relied upon to make his device. After Thomas Edison's second defeat, he decided to offer Granville Woods a position with the Edison Company, but Woods declined.

In 1888, Woods manufactured a system of overhead electric conducting lines for railroads modeled after the system pioneered by Charles van Depoele, a famed inventor who had by then installed his electric railway system in thirteen United States cities.

Following the Great Blizzard of 1888, New York City Mayor Hugh J. Grant declared that all wires, many of which powered the above-ground rail system, had to be removed and buried, emphasizing the need for an underground system. Woods's patent built upon previous third rail systems, which were used for light rails, and increased the power for use on underground trains. His system relied on wire brushes to make connections with metallic terminal heads without exposing wires by installing electrical contactor rails. Once the train car had passed over, the wires were no longer live, reducing the risk of injury. It was successfully tested in February 1892 in Coney Island on the Figure Eight Roller Coaster.

In 1896, Woods created a system for controlling electrical lights in theaters, known as the "safety dimmer", which was economical, safe, and efficient, saving 40% of electricity use.

Woods is also sometimes credited with the invention of the air brake for trains in 1904; however, George Westinghouse patented the air brake almost 40 years prior, making Woods's contribution an improvement to the invention.

Woods died of a cerebral hemorrhage at Harlem Hospital in New York City on January 30, 1910, having sold a number of his devices to such companies as Westinghouse, General Electric, and American Engineering. Until 1975, his resting place was an unmarked grave, but historian M.A. Harris helped raise funds, persuading several of the corporations that used Woods's inventions to donate money to purchase a headstone. It was erected at St. Michael's Cemetery in Elmhurst, Queens.

LEGACY

▪Baltimore City Community College established the Granville T. Woods scholarship in memory of the inventor.

▪In 2004, the New York City Transit Authority organized an exhibition on Woods that utilized bus and train depots and an issue of four million MetroCards commemorating the inventor's achievements in pioneering the third rail.

▪In 2006, Woods was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

▪In April 2008, the corner of Stillwell and Mermaid Avenues in Coney Island was named Granville T. Woods Way.

#granville t woods#black inventor#invented#world's first#electric roller coaster#1893#read about him#read about his invention#reading is fundamental#knowledge is power#black history

123 notes

·

View notes

Text

Telegraph Wires, Photo by Tina Modotti, 1928

288 notes

·

View notes

Text

Joseph “Uncle Joe” Clovese was the last known surviving Black soldier of the Union Army in the American Civil War, and lived in Pontiac at the time of his death in 1951. Clovese, who lived to be 107 years old, was born into slavery on a plantation in St. Bernard Parish, Louisiana, and escaped slavery in his teens to join the Union Army during the Siege of Vicksburg. He stayed with the Northern Army, first as a drummer, later as an infantryman. He was a private in Co. "C", 63rd Colored Infantry Regiment.

Following the war he worked on Mississippi river steamboats, and he later worked on the crew stringing the first telegraph wires between New Orleans and Biloxi, Mississippi. At the age of 104, Clovese moved from Louisiana to Pontiac, Michigan to be near family. Once the community learned about “Uncle Joe,” the citizens of Pontiac embraced him. Large gatherings were organized for his 105th, 106th and 107th birthdays on January 30th.

For his funeral, more than 300 people were packed into Newman A.M.E. Church in Pontiac (their former location, in downtown) for the service. Hundreds more gathered at the gravesite in Pontiac’s Perry Mount Park Cemetery. Veterans from the Oakland County Council of Veterans served as pall bearers. A firing party from Selfridge Air Force Base fired the final salute and taps was sounded over the cemetery. Pontiac even named a road in his honor, that ran through the Lakeside Homes complex.

Source: African Archives

125 notes

·

View notes