#rawcliffe

Video

Star Wars Plate Rail by Darth Ray

Via Flickr:

This plate rail started as a Hamilton - Star Wars Plates collection, but with the lack of space I've added other collections to it: 1. JusToys - Star Wars Bend-Ems 2. Hasbro - Bounty Collection figures 3. Rawcliffe - Pewter figures

#plate#rail#started#Hamilton#Star#Wars#Plates#collection#plate rail#Star Wars#JusToys#Bend-Ems#Hasbro#Bounty#figures#Bounty Collection#Rawcliffe#Pewter#flickr

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The Astrologer" LTD #2409/2500, Rawcliffe 1988 Pewter

Listing includes small wizard trinket box. Sculpture approximately 4.5" x 4.25".

Source:

Glendale, AZ

EJ's Auction & Appraisal

#the astrologer#wizard#ponder the orb#pewter#limited edition#1988#sculpture#miniature#auction#arizona#rawcliffe#bidding#online#estate

1 note

·

View note

Text

It took me until I was almost through with Game of Thrones to figure this out, but I figured out another reason the urban setting of King’s Landing was bothering me. I obviously have a lot to say about GRRM’s medievalism, but King’s Landing isn’t even pseudo-medieval as much as it is Dickensian.

This felt like a great epiphany to me. The crowds, the rumors about dysfunctional politics, the police king’s guards everywhere, the travesty of formal justice as spectacle... this could be a Tale of Two Cities/Bleak House mashup. Now, I love Dickens, who is commenting both on the Bad Old Days™ of a few generations earlier and on the injustices of his own time, and who is always very specific about both of these and his urban settings. King’s Landing is barely sketched out in comparison (all we need to know, apparently, is that it is dirty and policed) but in its crowding and its iniquity, it owes more to the cities of nineteenth-century European literature than to the cities of medieval Europe.

#me haunting grrm: medieval! cities! didn't! have! police!#read! carole! rawcliffe! on! public! health!#a medievalist does got#grrm critical#is a tag this site has#ned's death also reminds me of vingt ans après but that's another story

127 notes

·

View notes

Text

A view along Moore Street from the junction with Rawcliffe Street, South Shore, over 100 years apart from the exact same location.

On the left of the junction you can see the Ebenezer Chapel Methodist Church, and opposite on the right corner stood a pair of Sunday Schools, all have long since been removed for housing.

1 note

·

View note

Video

Walk by the Ouse by Allan Harris

Via Flickr:

From Rawcliffe to Beningbrough

0 notes

Text

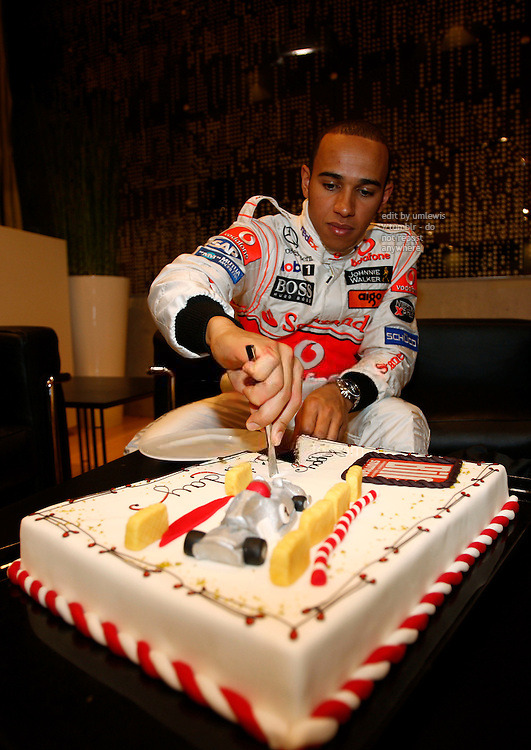

lewis hamilton enjoys a slice of birthday cake at the launch of the mp4-23 - january 7, 2008

📷 david rawcliffe / propaganda-photo.com

#op took 2+ hours manually removing the watermarks and will slingblade you if you steal these :)#lewis hamilton#f1#formula 1#flashback fic ref#flashback fic ref 2008#not a race#2008 not a race#pre-season#pre-season 2008#car launch#car launch 2008#tw food#cw food

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

Medieval people were very concerned about how to deal with those in their midst who had leprosy, now called Hansen's disease. It's assumed today that sufferers were shunned from society, forced onto the margins, and generally hated.

But in this episode of Gone Medieval, Dr. Eleanor Janega finds out from Professor Carole Rawcliffe about what was it really like to live with leprosy, both as a sufferer or as a member of the communities that needed to care for them.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Man, some folks need to read a book or two on the history of medicine.

Try Roy Porter, Carole Rawcliffe, or Steven Cherry. There are also great articles often available for free on Pubmed. If not, email the first author - they'll get it to you.

(Hey, did you know the debate about whether consciousness was stored in the heart or the brain continued until the 18th century? And that the father of neuroscience, Santiago Ramón y Cajal, lived until the 1930s? That an understanding of Mendelian genetic inheritance in humans - an "inborn error of metabolism" - was postulated based on a family in London with Alkaptonuria, aka "black urine disease," and that that research was not published until 1902 (by Archibald Garrod). Between 1902 and the present, basically everything we know about chromosomal-level genetic inheritance and mutation was discovered? Did you know that the reason calico and tortoiseshell cats are always female is due to the presence of Barr bodies, which is an inactive X chromosome, and this can also be seen in humans, including in males with Klinefelter Syndrome [XXY] and in sterile male calico/tortoiseshell cats? And that even more rarely, a male calico/tortie is not sterile?)

(Do you know why the Hippocratic Oath is called the Hippocratic Oath? Who Galen is? The age of the oldest known eyeglasses? The four humors, and what they were believed to represent? Why medicine stagnated during the first few centuries of Christian dominance in Europe? What the link is between sickle cell anemia and resistance to malaria? What is the modern treatment for bubonic plague? Who Phineas Gage was? What animal Luigi Galvani used to study the role of electricity in neural connections? Who frickin' Rosalind Franklin is???)

Seeing that post about arguing against there not being enough research into hormonal and surgical treatments for trans men and women... Man. That one hurt my head.

Since 1990, we've learned how to keep HIV all but dormant and to stop it passing from a parent to child. Chemotherapy for cancer treatment was first developed in the 1940s, and radiation is actually older than chemotherapy. Hemophilia B can be treated now quite simply by injections and transfusions to introduce Factor IX, a clotting factor, when before the 1950s it was a death sentence. The structure of DNA wasn't discovered until 1953 - now, students in basic biology labs can play around with splicing and inserting sequences into genetic codes!

My point is... a lot of what we understand about medicine has, for various reasons, only become established and accepted in the last 200 years or so. And with gene therapy, it's likely to explode again.

Read up on the history of medicine. Especially if you question its use in certain people to help them physically become who their conscious mind knows they are. You might learn something!

And honestly, the history of medicine is insanely grim-and-gross fun. If you're into that. 😉 The Mütter Museum is also out there!

69 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Nicola Bulley: Body found in river confirmed as that of missing mum

The 45-year-old disappeared during a riverside dog walk in St Michael's on Wyre more than three weeks ago, sparking a major search operation. Ms Bulley, who worked as a mortgage adviser, was last seen walking her springer spaniel Willow after dropping her daughters, aged six and nine, off at school. Her dog was found shortly after, along with her phone - still connected to a work conference call - on a bench by a steep riverbank. Ms Bulley's disappearance sparked a major search operation by Lancashire Police.

On Sunday 19th February, officers were called to the River Wyre close to Rawcliffe Road at about 11:35 GMT following reports that dog walkers thought they had found a body in the water about one mile away from where she was last seen on the morning of 27 January.

"An underwater search team and specialist officers have subsequently attended the scene, entered the water and have sadly recovered a body," police said. The force has consistently said they believed the 45-year-old had gone into the river and that her disappearance was not suspicious.

Briefing the media at police headquarters, Assistant Chief Constable Peter Lawson said Ms Bulley's family were "of course devastated".

Ms Bulley's family paid tribute to "the one who made our lives so special" before criticising media intrusion. "We will never be able to comprehend what Nikki had gone through in her last moments and that will never leave us," the family said in a statement.

Read the full statement from Nicola Bulley's family

The family also questioned the role of some sections of the media during the investigation and accused journalists of "misquoting and vilifying" Ms Bulley's partner Paul Ansell, relatives and friends.

"Our girls will get the support they need from the people who love them the most," the family said "And it saddens us to think that one day we will have to explain to them that the press and members of the public accused their dad of wrongdoing [and] misquoted and vilified friends and family.

The family also criticised Sky News and ITV, whom they said had contacted them despite their appeal for privacy on Sunday.

"Finally, Nikki, you are no longer a missing person, you have been found, we can let you rest now. We love you, always have and always will, we'll take it from here xx."

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lilly, from Hull, says she was told to lift up her blouse - along with classmates - so the staff member could make sure their uniform was bought exclusively from the school's official provider. Holderness Academy student Lilly was found to have been wearing a pleated £7 number from the high street supermarket instead of the near identical mandatory £17.99 version - so she was sent to learn in isolation.

Lilly's mum Katie told Hull Live: "She wore a Sainsbury's skirt last year and had no problems. Katie and Lilly's dad, Wayne, say that due to her slim physique, they failed to find a skirt to fit her from Rawcliffes Schoolwear and instead purchased one from Asda.

Katie added: "We originally did try to get her the right skirt but Lilly is tiny, it kept falling off her. The skirts are between £17.99 and £21.99 each from Rawcliffes, but we managed to find black pleated skirts from Asda, which cost £7 for two.

"This year, teachers have been asking pupils to lift up their blouses so they can see the label in the waistband. When Lilly was found to have an Asda skirt, she was put in isolation and came home very upset."

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Prairie Star Dental

youtube

Dr. Thomas Rawcliffe seeks to provide excellent and quality care, by ensuring that his patients feel comfortable, informed, and appreciated. With each patient's long-term well-being in mind, he strives to provide comprehensive, personalized treatment in a calming atmosphere. Contact our Round Rock TX dentist's office for an appointment.

Dental Implants

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

CHAUCER’S VOICING OF THE ‘WOMAN OF GREAT AUTHORITY’

“Chaucer’s dramatisation of the docile body of Mary is, as Reames argues, evidence of the orthodox Mariology articulated in his works. She asserts that the poet conforms to dominant Christian doctrine, since he avoids ‘the theological error of setting her in competition with the Trinity, as if she were a goddess, a supernatural being with power all of her own’. Notwithstanding Reames’s convincing argument, textual evidence suggests that, instead of enclosing Mary within the ideological walls of an inescapable doctrine, Chaucer’s texts open up a debate on Mariology with a specific concern for her status, power and agency in relation to Christ and the Trinity in general.

Alongside Marian doctrinal orthodoxy, founded on the concept of the merciful ‘vicaire’ of God, the poet’s work appears to accommodate variant doctrinal stances which are largely dependent on the emerging cultic standing of Mary in the later Middle Ages, especially within the practices of affective piety. This development is testified, for instance, in the establishment of the cultural and theological trope of Mary the Physician.

As Diane Watt explains in her essay for this collection, the emergence of this trope is consistent with women’s heavy involvement in healing practices, so much so that Carole Rawcliffe, among others, points out that ‘in an age before the establishment of a professional monopoly wise women, empirics and herbalists actually constituted the great majority of practitioners at work’.

Monica Green’s survey of medieval female practitioners reaches a similar conclusion on the ubiquity of women in the care of patients: Although they were not represented on all levels of medicine equally, women were found scattered throughout a broad medical community consisting of physicians, surgeons, barber-surgeons, apothecaries, and various uncategorizable empirical healers.

Although her work focuses on the Early Modern period, Margaret Pelling’s findings on the role played by women in ‘medical families’ give insights into a socio-cultural context that undoubtedly started to develop in the Middle Ages and is therefore relevant to the times in which Chaucer was writing his Marian texts. Pelling gathers compelling evidence that supports a re-assessment of the influence that women exerted on male members of their families during the domestic formative years that preceded their formal training as physicians.

Despite their ubiquity, the cultural and professional standing of women as providers of care and cure was decidedly inferior to many of their male counterparts and was met with much resistance from the medical academic establishment and society in general. For instance, in his categorisation of medical practitioners, Huling E. Ussery places women among the ‘lesser practitioners’ and, more specifically, among the ‘unlicensed and unaffiliated practitioners’ such as leeches, midwives, ‘wise women’, herbalists and quacks.

Notwithstanding her attempt to re-assign agency to Early Modern women in medical practice, Pelling concedes that, precisely because of the profound interconnection between domesticity and medical care, women’s engagement with medical practice remains largely confined to the domestic space. Far from being a result of women’s lack of skill in matters of care and cure, their professional subordination to male physicians is largely due to ideological and institutional resistance to women’s access to the profession.

The gendered rationale behind such resistance becomes apparent in the petition presented before Parliament in England in 1421 demanding that ‘no Woman use the practyse of Fisik’. Validated by theological and scientific discourse, hostility to recognising the centrality of women’s contribution to medical practice is illustrated by Bruno of Calabria’s contemptuous pronouncement that ‘vile and presumptuous women usurp the office to themselves and abuse it, since they have neither learning nor skill’.

Clerical and professional homosociality traps women in an ambiguous professional position in which their agency is undermined. As the posthumous representations and mis-representations of Trotula of Salerno testify, women at the heart of the cure and care of the sick were ostracised and their authority usurped by male practitioners.

As Green demonstrates, from the Middle Ages onwards women were gradually excluded from medical practice and, in the areas of care traditionally associated with female practitioners, such as midwifery and gynaecology, they were ‘gradually restricted to a role as subordinate and controlled assistants in matters where, because of socially constructed notions of propriety, men could not practice alone’.

This is, therefore, a gender-specific issue of authority and power which resonates with the doctrinal debate on orthodox Mariology to which I alluded earlier. Despite institutional hostility to women and their subordinate professional status, Watt’s essay shows that the trope of Mary the Physician advanced the cause of female medical practitioners by giving female acts of care a devotional prominence.

In fact, the Virgin’s assistive function dramatised in Custance’s prayer to Mary in The Man of Law’s Tale or in the ABC positions Chaucer’s texts within doctrinal orthodoxy, but does not account for the heterogeneity of the late medieval debate on Mary’s authority. Hilda Graef ’s extensive mapping of Marian theology demonstrates that, if eminent Christian thinkers such as Aquinas rejected the very possibility of endowing Mary and the Trinity with equal agency, St Bonaventure and other medieval auctores argued for the Virgin partaking in God’s redemptive plan.

A much earlier precedent to Chaucer’s engagement with this variant Marian doctrine is the experience of Christina of Markyate, a twelfth-century English visionary and hermit. In the account of her life we find further evidence of the cultural currency of Mary’s authority. In her essay for this collection, Watt discusses an event narrated in the Life of Christina of Markyate which unequivocally frames the interconnection between spiritual and medical practices within a discourse of power.

Afflicted by illness, Christina was tended to by a number of male physicians who, however, failed to cure her. Healing could only be effected by a female practitioner who appeared as a vision to one of Christina’s companions while she was dreaming. The text describes the physician as an agent of authority and power whose medical skills clearly exceed those of her male counterparts. The ‘magne auctoritatis matronam’ [woman of great authority] is firmly identified as the Virgin Mary, as Watt explains.

While the vision preserves Mary’s traditional feminine attentiveness in the act of providing care (‘Quod cum delicatissime prepararet. ut cibaret illam’ [‘While she was daintily preparing to give it to her’]), her power is articulated through her silent gravitas and self-assured disregard for warnings about an inevitable failure of the cure.

It is in this context of multifarious Marian devotion that Chaucer’s heterodox Mariology can be situated. In her analysis of the ABC, Reames normalises Chaucer’s ‘extravagant’ attempts to endow Mary with redemptive authority by restoring his orthodox credentials: ‘he resists the most serious excesses of Marian piety … the temptation to set Mary against God, to glorify her at His expense’.

I would, instead, contend that, rather than dramatising mere ‘extravagant’ exceptions, Chaucer’s literary Mariology engages with the heterogeneous debate on Mary’s authority and presents the reader with a vision of the Virgin that is strikingly consistent with Christina’s ‘woman of great authority’. The ABC opens with an invocation to the Virgin that unequivocally endows her with a degree of authority normally only associated with God: ‘Almighty and al merciable queene’ (1).

Also, Chaucer’s verse accommodates slippages in meaning that open up the text to counter-hegemonic descriptions of Mary’s power and agency: Soth is that God ne granteth no pitee Withoute thee; for God of his goodnesse Foryiveth noon, but it like unto thee. He hath thee maked vicaire and maistresse Of al this world, and eek governouresse Of hevene, and he represseth his justise After thi wil; and therfore in witnesse He hath thee corowned in so rial wise. (137–44)

Grammatically and ideologically, the Virgin’s agency is obliterated by identifying God/‘he’ as the subject of sentences describing Mary’s function rather than Mary/‘thee’ who is, instead, the object of such clauses (‘He hath thee maked’; ‘He hath thee corowned’). At the same time, however, the text speaks her authority, since she dominates a secular and spiritual hierarchy of which she is both ‘maistresse’ and ‘governouresse’.

Most importantly, her will appears to inform God’s justice, as the verb ‘represseth’ suggests a variant power relation in which the Creator chooses to position Himself as a subject to Mary’s authority. In other words, the ABC dramatises a doctrinal stance on the Virgin that can be aligned to the emerging Marian piety in the tradition of Christina of Markyate’s vision. In The Prioress’s Prologue this strand of Mariology becomes apparent: ‘For she hirself is honour and the roote / Of bountee, next hir Sone, and soules boote’ (VII. 465–6 my emphasis).

The ‘soules boote’ and Mother of Christ is here portrayed not in the assistive role of Mary the nurse, as Henry of Lancaster posits, but as Mary the Physician who partakes in God’s salvific plan in an equal position of power. Mary’s authority, nonetheless, distinguishes her from the vengeful and aloof God represented in the ABC. The speaker addresses Mary because God appears unreachable for the mortal sinner trapped in a secular world; the Virgin, on the contrary, is the ‘vicaire’ or incarnated divinity.

The extract from the ABC which I quoted above articulates Mary’s dual potency through the use of anaphora, as she is at once ‘[o]f al this world’ and ‘[o]f hevene’. The incarnational power of Mary is also apparent in Pearl, a key example of literary Marian figuration in the Middle Ages. In her analysis of the poem, Teresa Reed identifies the Virgin as a devotional locus in which the spiritual and the carnal can be negotiated as one: ‘[i]n the same way that Mary articulated the Word − that is, gave it intelligibility by giving it the jointed form of the human body − this poem attempts to make the transcendent intelligible through the physicality of form and sound’.

In The Prioress’s Prologue such physicality is endowed with an unmistakably carnal connotation: O mooder Mayde, O mayde Mooder free! Of bussh unbrent, brennynge in Moyses sighte, That ravyshedest doun fro the Deitee, Thurgh thyn humblesse, the Goost that in th’alighte. (VII. 467–70) Chaucer’s text liberates Mary from the Irigarayan ‘envelope’, a docile text perpetually written and re-written, and stripped of agency.

Here she transcends her configuration as mere semblance to become a chiasmus, that is, a space open to multiple, often paradoxical subject positions; she is at once mother/ maiden and maiden/mother, the burning bush of hope and the un-burnt (untouched) virgin, and humble yet capable of ravishing the Ghost. In sum, in The Prioress’s Prologue Mary is the meek virgin inducing spiritual ecstasy, but also the woman of great authority exerting sensual power.”

- Roberta Magnani, Medicine, Religion and Gender in Medieval Culture

#medicine religion and gender in medieval culture#roberta magnani#religion#christian#medieval#medieval literature#geoffrey chaucer#medicine#gender

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dragon Wizard figurine pewter dungeons D&D Perth spoontiques rawcliffe valentine

0 notes

Text

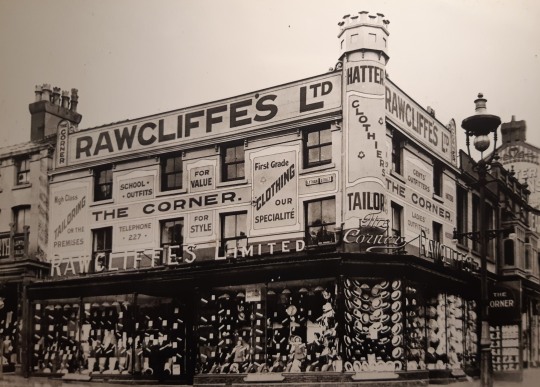

The Rawcliffe's building at the junction of Corporation Street and Church Street, famous for providing every schoolkid with their uniforms.

The building was rebuilt in 1914 with Rawcliffe's later moving to a new premises. A variety of businesses have been housed here since then including Dixons, Currys and now most recently Costa Coffee, the building however still bares the Rawcliffe's name upon its roof.

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

0 notes