#postcolonial

Text

DECOLONIAL ACTION READING

I recently compiled these to add to a comrade’s post about Land Back, but actually I think they deserve their own post as well.

Amílcar Cabral - Return To The Source

Frantz Fanon - The Wretched Of The Earth

Hô Chí Minh - archive via Marxists.org

Thomas King - The Inconvenient Indian

Abdullah Öcalan - Women’s Revolution & Democratic Confederalism

Edward Said - The Question Of Palestine

Thomas Sankara - archive via Marxists.org

Eve Tuck & K. Wayne Yang - Decolonization Is Not A Metaphor

Other key names in postcolonial theory and its practical application include:

Sara Ahmed

Homi K. Bhabha

Aimé Césaire

Albert Memmi

Jean-Paul Sartre

Léopold Séder Senghor

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak

All of these will help you interpret and confront the realities of colonisation, and ideally help us understand and extend solidarity to comrades around the globe. Decolonise your mind, and don't stop there!

#land back#postcolonial#postcolonialism#postcolonial theory#decolonization#decolonize#decolonise#decolonisation#Edward Said#Tuck & Yang#Frantz Fanon#Amilcar Cabral#Free Ocalan#Sankara#Ho Chi Minh#Thomas Sankara#Abdullah Ocalan#original#Thomas King#Eve Tuck#K. Wayne Yang

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

The portrayal of the precolonial and early colonial women babaylan as oppositional to patriarchal colonization configured them as protofeminists... Mangahas claims that whereas the women babaylan were annihilated, assimilated, or compromised by the colonial order, the power of Philippine women was not fully lost... Many present-day women professionals, mostly from urban and/or diasporic middle-class backgrounds, have been attracted to the image of the babaylan and have ascribed the babaylan title to themselves... These developments have inspired many in the face of ongoing violence and discrimination against women, immigrants, and other minorities, in domestic and work places, in the homeland and in the diaspora.

Scholars like Zeus Salazar, however, observe the alienation between what he calls the "babaylan of the elite and the babaylan of the real Filipino [who] still sit with their backs against each other." Salazar warns that the "Babaylan tradition could be co-opted by new-age type spirtuality-seeking affluent, middle class Filipinas whose end goal is individual spiritual enlightenment.

...Not a few have pointed out the problem of extracting the babaylan title as though it were a commodity to be acquired without first going through Indigenous channels and protocols... To abstract the title from the process and relationships just because one is attracted to images of Indigenous women that converge with feminist models or because one has the privilege to do so is facile and demonstrates a lack of respect for Native ritual specialists and their communities.

- Babaylan Sing Back by Grace Nono

#philippines#indigenous#precolonial#postcolonial#history#yes yes yes finally someone said it#early on in my precolonial philippine research#i kept coming across these websites and articles about how we should embody our inner babaylan#and it felt so strange that most of the writers of these pieces were diasporic and actually had no babaylan training#it just felt so... exploitative to me#i'm so glad to hear that scholars have been criticizing this movement all along

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Decolonize Sorbian Settlement Area'

Digital Collage, 375 x 375 mm, 2024

Fine Art Pigment Print under Acrylic Glass,

Black Aluminium Art Box

Lets talk about decolonization of the sorbian settlement area. My recent project of artistic research.

#neue sorbische kunst#nsk#bernhard schipper#leipzig artist#nsk folk art#sb2130#sorbian artist#nsk state lipsk#Decolonization#anti colonialism#SorbianSettlementArea#SorbischesSiedlungsbebiet#SerbskiSydlenskiRum#SerbskiSedleńskiRum#autochthon#indigen#artisticresearch#selfdetermination#fundamentalrights#Indigenous#postcolonial#Dekolonisierung

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

STALEY BRIDGE STALYBRIDGE

STALEY BRIDGE STALYBRIDGE

this is Staley bridge

my father's birthplace

here is a picture

of me in a pram

my sister

in a pram

on a big bridge

crossing the Tame river

this is not

that Staley bridge where

the Saxons crushed the

Vikings

rushing back to

meet my

Norman ancestors at Hastings

and we

know what happened there

****

Yes, here we are

up front Mossley

in that picture, my

Mother

daughter of a war hero

pushing our pram

and there, no doubt,

the great cotton mills

still

doing their job though

not now in

their hey day

postmodernity,

postcoloniality

what landscape altering modes

of production ushered

in in

their wake

and here is Engels incliding

text on this place in his seminal

work on

the working class

in England

and here I am

years later, studying satire living

in his monument house

in Oxford Street Manchester

water

under this bridge, water

connecting

us all

Tipperary, Stalybridge,

Mahikeng South Africa

figures

in a Lowry paintimg

they come

and they go

water

under this bridge then

so much water we

tend to

forget about

water headed

to the port of slavery

same water in the skiffle

psychedelia of those

Sergeant Pepper people

magicians of the airwaves

conjurors of

a whole new

line

in identity

fruit of the clash of

working class proclivities

with

transcendental

mind

clash, I say,

but what a melding, beloved

blending

without which

no way this space, or place,

or room

to talk

gone these guys

or finally fading

gone

those mills of my childhood

Spitfire stories

of how

we stood alone

everything reconfigured,

outright repurposed

voices (and their words)

I fail to recognise, alien

strange

elevated above whilst

so out of frame

somehow talking all

necessities of suppression

commandeering everything

stretching

the distance below

to above

to breaking point

viewed from

the Southern tip of Africa, product

victim of

all that this is metonym of

all this place

this life

of which

I speak

ths

shock

could not be more

extreme

(so dark

these river with

their druid name

we cross

all our lives

each

every day

so quietly all

determining)

#childhood#history#life#humanity#mode of production#Liverpool#Ths Beatles#poem#poetry#Tameside#Manchester#Engels#postcolonial#Empire

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Manhattan is a Lenape Word

by Natalie Diaz

It is December and we must be brave.

The ambulance’s rose of light

blooming against the window.

Its single siren-cry: Help me.

A silk-red shadow unbolting like water

through the orchard of her thigh.

Her, come—in the green night, a lion.

I sleep her bees with my mouth of smoke,

dip honey with my hands stung sweet

on the darksome hive.

Out of the eater I eat. Meaning,

She is mine, colony.

The things I know aren’t easy:

I’m the only Native American

on the 8th floor of this hotel or any,

looking out any window

of a turn-of-the-century building

in Manhattan.

Manhattan is a Lenape word.

Even a watch must be wound.

How can a century or a heart turn

if nobody asks, Where have all

the natives gone?

If you are where you are, then where

are those who are not here? Not here.

Which is why in this city I have

many lovers. All my loves

are reparations loves.

What is loneliness if not unimaginable

light and measured in lumens—

an electric bill which must be paid,

a taxi cab floating across three lanes

with its lamp lit, gold in wanting.

At 2 a.m. everyone in New York City

is empty and asking for someone.

Again, the siren’s same wide note:

Help me. Meaning, I have a gift

and it is my body, made two-handed

of gods and bronze.

She says, You make me feel

like lightning. I say, I don’t ever

want to make you feel that white.

It’s too late—I can’t stop seeing

her bones. I’m counting the carpals,

metacarpals of her hand inside me.

One bone, the lunate bone, is named

for its crescent outline. Lunatus. Luna.

Some nights she rises like that in me,

like trouble—a slow luminous flux.

The streetlamp beckons the lonely

coyote wandering West 29th Street

by offering its long wrist of light.

The coyote answers by lifting its head

and crying stars.

Somewhere far from New York City,

an American drone finds then loves

a body—the radiant nectar it seeks

through great darkness—makes

a candle-hour of it, and burns

gently along it, like American touch,

an unbearable heat.

The siren song returns in me,

I sing it across her throat: Am I

what I love? Is this the glittering world

I’ve been begging for?

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hello people of the universe.

Welcome to the Cybergardenities Archive, please read this post to get a hold what we’ll be doing here.

On this page I will be posting my artistic research in the field of anti and posthumanities. There will be several types of posts. Expect source text repositories (links to texts I’m working with), cool art I find (both relating to specific project and appealing to my general interests) and finally my own projects. I will also share music recommendations, and different thoughts I have about state of our world, but I want to maintain focus on documenting creative and research processes I’m doing.

I do my research to inform myself and others on different aspects of solarpunk, here understood as a modern, multi-faceted counterculture movement that seeks to overthrow and replace current socioeconomic system with one that respects everything that lives (or not).

Discussion and suggestion is encouraged <33. Bear in mind that transphobes, racists, antisemites, queerphobes, ableists and all bigots will be banned relentlessly, human rights are not up for discussion, respect people here.

Video editing and color grading commissions are welcome, please check at the portfolio post if you want to know more.

Thank you and wish you a pleasant stay.

#cybergardenities#posthumanism#biohacking#transhackfeminism#xenofeminism#art#new materialism#research art#cybergarden#counterculture#artist research#queer#trans#transfeminism#postcolonial#glitch feminism#glitch art#punk

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Would anyone be able to point me to a good Indigenous/postcolonial analysis of From Dusk Till Dawn, either the movie(s) and/or show? 'Cause it's something I've been wondering about for a while now.

#my complex feelings on tarantino#quentin tarantino#robert rodriguez#from dusk till dawn#indigenous issues#indigenous#indígenas#mesoamerica#postcolonialism#postcolonial

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hearing that now the British prime minister want to come to Israel/Palestine is like

What, he wants to come to finish the job?

[Moment of history: the British colonization in Israel/Palestine is also known by elitist idiots as the British mandate because the UN gave them authority on this land until the local, or idiot laymen as they thought of us, will be able to operate as one or two states. SO, basically, when they arrived here, they manifested what was called as "the white book agenda", it's also common on other british-controlled areas, and it just states their policies, distribution of finances, and basically their plans for the place. And so, they singlehandedly distributed the idea that this is a zero sum game -- if Arabs get something it means Jewish people can't and vise-versa. Now, the white book agenda did change every now and again according to British wants and needs, so it made everything here extremely more difficult and unstable. And basically, if you want to trace down where the jewish-arab hate for one another began -- START WITH THE FUCKING BRITISH]

#israel#palestine#british empire#britain#mandate#colonization#war#postcolonial#fuck i hate this bullshit

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

after the deluge

endings

The first of the buildings fell today. The salt had eaten away at the foundations, the water churned and crashed into the walls, until it buckled under the weight of sixteen storeys of concrete and collapsed. We don’t see it happen, but we hear the groaning, the almighty crack, and we walk down and hang from the fourth floor windows and snatch at the fruits that rush down from the ruins before they’re swept out to sea.

Sarah has a real find. We walk back into the living room and I smack the thick layer of dust off the table with a cushion, and she puts down the small, coconut-green fruits.

“Guavas!”, she says, wiping her arm off on her dress. “Now we can have guavas. I’m so happy. Let’s go plant these now.”

“I haven’t had these in forever”, I say. A roach skitters past, and I stomp on it. The air in the room is heavy, it smells like dust, and like rot, and like everything else it smells like the sea. I’m concerned for a second. The same ocean would be rotting our walls, the same salt rusting away the iron that held us upright, and it was only a matter of time before we crashed down too. I’d thought it wouldn’t be for a long time yet, but everyone thinks that. You learn to ignore the worry, like you learn to ignore the constant rolling roar of the sea, and the thick wet weight of the air that leaves you slick with sweat.

“How do you reckon M and L are doing now?”, Sarah says.

“I’m sure they’re doing alright”, I say. I’m not sure.

“Yeah.” She’s not sure either, they may be alright, or they may be floating and bobbing on the waves miles out in the middle of the ocean, and the fish may be pecking at their eyes and the fish may be pecking at her belly.

Leaving the buildings isn’t easy. You need ropes and hooks and guts, the water chops and snarls below you, sharks circle, and at night pale pink lights pace over the water. None of us even know for sure if there’s somehow past the buildings where you can be picked up and flown to the continent. We’ve heard of it, but that’s no guarantee it exists. That isn’t why we stay; the buildings are our home, and no great imperial cities in the continents will ever change that, not when they did this to us in the first place.

Rashida told us how the grand cities have not buildings but towers, hundreds of storeys high, shining like jagged shards in the sun. They’d be around for hundreds of years, and the voices of children would bounce off their stairwells and the feet of children would thump on their roofs long after we’ve all drowned. The water keeps rising, and the pillars below us keep crumbling. M had to leave.

There’s an old, old folk tale Rashida told us: a sea-demon would rise every month on the full moon and demand the sacrifice of a daughter from the island. Every month the families would draw lots and send off a daughter to wait in the palace by the sea, and every month they’d find her dead body, untouched but for the scrapes of dried salt over her elbows and behind her knees. One month, a Moroccan explorer and Sufi mystic was travelling through the island when he heard about the sea-demon. He volunteered to put on a woman’s dress and wait in the palace in a daughter’s stead, and as the demon rose out the sea, he read passages of scripture, sealed the demon in a bottle, and cast it out to sea.

The explorer ended up settling in the island, the royals became his disciples, and the island learnt at his feet. When he died, he was buried in a grand tomb of blue and white marble. The tomb is submerged below the waves now, and inside his coffin his remains would be floating in sea-water.

histories

We knock gently at Rashida’s door and wait for her to croak out a welcome. She lives on the seventh floor, right below us on the eighth, where we can climb out onto the roof from right across our door. Rashida always wears a bottle-bright dress in green or red, with fine filigree around the neck and sleeves. They were what islanders used to wear decades ago, and Rashida is a traditionalist. She’s woven filigree into all Sarah’s dresses too.

Sarah sits down on the floor in front of Rashida and places the three guavas on her lap. Rashida smiles, and strokes Sarah’s hair. Her face is like paper crumpled up and smoothed out again, and the frame of shadows around her wrinkles flicker and dance in at the corners around her eyes and lips. Rashida is from the last generation before the waters rose, the generation that straddled the centuries before the world arrived and these years after the sea pushed the world back away. We know all we know of the world and all we know of the islands through Rashida. Rashida was young before the days when the global Internet linked up to our islands; she remembered how we used to be, how we had been for centuries before.

Rashida told us of the holidays when she hid up in trees and threw bags of colourful paint-water at revellers, until her cousin pulled her down and burst a bright red stain onto her dress. She told us of how the fishermen came back an hour before sunset and the children looked for dried-out coconut husks to fill the stone pits as the women rubbed chilli salt into the freshly-caught fish that shone silver and slick in the light of the setting sun, and of sitting on slanting shelves of sand that eased into the sea, watching the sun sink and the ocean suck up all the fire from the sky and glow golden, watching the fish on spears grilling above the glowing red coconut-coals, the silver skins turning a coralline pink with charred edges, breathing in spicy smoke mixed with the salt in the air and the salt on the men’s bodies.

And then with the new millennium came the world, beamed to us through satellites like the ones we can still see in the night sky from the glinting of their wings, and we beamed back, and then the tourists came to marvel at our seas and to sun themselves on the sandy slopes that are now deep below the surface, somewhere off behind where the buildings end, and the fishermen packed up the fish to ship to far-away countries where the buildings were a dozen times as tall and still touched the earth.

In Rashida’s teens nobody bothered with bags of paint-water. Nobody wore filigreed dresses; they weren’t fashionable and such a concept as fashion mattered, for a brief time. She went to rock shows, because there were rock bands now, and stores with guitars, and stores with screens and machines you could plug into the Internet and talk to anyone around the world, and watch anything that happened anywhere else, and for a while the world was the biggest it ever was, and our islands the smallest. But she’d barely reached her twenties before the sea began to lap first at the streets, then the doorways of houses, the stages of rock venues. Everyone wealthy left. Everyone left turned to anger, and then to reclamation, and as the waters rose and spilled in through the boarded windows of museums and libraries islanders broke in, took back the copper plates and old books, took back their stories and their history. They threw their guitars into the rising oceans, threw everything foreign into the sea.

The dragonflies came back after twenty years gone, and they’re still here. The scorpions came back after forty years, and they’re still here. They dart between the leaves and crouch between the plant-pots on our roofs.

One night everyone woke up to find they were trapped in their homes on the fourth and fifth and sixth floors of their buildings. We were starting over, in atolls of concrete islands jutting out of the sea. The memories of the world faded and we went back to being islanders.

presents

Sarah nudges Rashida. “Look what we’ve got”, she says.

Rashida holds a guava up to her foggy eyes, presses it with her fingers, nods, and smiles at us. “I haven’t had these in forever”, she says.

Sarah laughs. “That’s what he said, too.”

“This is good”, Rashida says. “Will you grow them?”

“Tonight.”

“Good.”

I bring Rashida a knife from the sink, and she expertly cuts up the guava into slices, looking straight ahead all the while, scooping out the lines of seeds and putting them by her feet. The smell fills the room as she cuts and the first whiff hits me with how new it smells, a heady mix of flowers and sugar and musk and dusk and the colour pink, and then I take another breath and I’m hit again, this time with a flooding recognition that hurls me back into a time when the walls weren’t moulting scales of paint and there were more of us in the building, to sitting at the end of a full dinner table, content and happy and full-bellied, biting into dessert. I realize that the air feels different now that it did then. There’s only the three of us in the building now.

Rashida hands each of us a slice, and then bites into one herself. A rivulet of juice snakes through the wrinkles down the corner of her mouth. I sit down next to Sarah, and she reaches out a hand and clasps mine. We look at each other, and at our slices of fruit, pulpy and the pale green-white colour of plantain slices, and at the sticky syrup on our fingers. She sinks her teeth in slowly and closes her eyes as a smile spreads across her lips. I laugh at her pleasure in the moment and she laughs back, and sultrily closes her mouth over another bite of fruit, slowly, so her lips glisten with the juice that dewed on the surface of the guava.

When we’re done Rashida pulls out a tome from by her bed and opens it to a bookmark, to a spell she’s done for us many times by now. It’s old magic, from handwritten books by island mystics of a generation before her, who learnt it from a generation before them, and so on to the first Sufi travellers who perhaps learnt them from desert mystics, or perhaps came across them in fits of divine inspiration as they prayed, or crafted it themselves after decades of learning all there was to know in the world, but it doesn’t matter where it began because now it keeps us alive and here, in our homes.

The spell Rashida is writing down on a scroll of paper is for fertility. We wrap it around the seeds before we put them into the soil and it keeps them growing. Before Rashida re-learnt our ancestral magic the adults that came before us had tried to make fertilizer out of fruit peels and fish bones and the waste they’d otherwise let float away with the waves, but there was never enough for the trees to keep growing. Rashida filigreed their dresses, pulled out the stitches on their pants and sewed them into sarongs. She would not go gently into the angry sea. So Rashida learnt old magic off old books, magic that had been common before the world came to us, magic like the Sufi had used to cast out those that tried to take from us. And we stayed here, defiantly ourselves, refusing to be assimilated into empire.

“I should start teaching you these things”, Rashida tells Sarah, as she hands over the spell. “I’m not going to live forever, you know.”

Sarah’s face drops, as if she’d never considered the possibility.

“Yeah, of course”, she says. “You should. I should learn these things.”

When we leave, Sarah closes the door behind her and sits down on the floor and pulls me down to her. She wiggles over and lays her head down on my lap, face buried into my stomach, and she lies still for a while as I stroke her hair.

beginnings

Planting has been our little ritual, ever since the others left. Rashida’s too old to climb up here so Sarah and I are the only ones that ever go up to the roof anymore, and that means we’re the ones who plant the seeds and tend to the saplings, weigh down the pots so the growing trees don’t topple them over. Tonight she’s kneeling over a pot, scratching a line into the soil and smoothing the thin scroll over the bottom, pressing the seeds into the paper, smoothing the earth back over. I pour water over her clasped hands and into the soil as she reads the words Rashida’s taught up, and the water slides in through her fingers and over the sides of her hands and sinks into the soil.

“In the name of the most merciful, come forth with life”, she says, and closes her eyes for a few long moments.

“Is it done?”

“I think it’s done.”

We go sit down at the end of the roof, the rustling, whistling canopy to our backs, looking out over the city. Moonlight bathed everything in silvery-blue. Shadows pooled under windows, in the spaces between buildings, around the trees on the rooftops below us. The buildings themselves look translucent, like they’re made up of moonlight and shadow. Each of the masses rising up out of the water is dead still except for the shimmering shadows of the trees, but the ocean below is a whirl of activity, choppy and roaring and foaming at the teeth. Off in the west, a couple of djinn float over the water with their long red dresses and jet-black hair falling down to their ankles. One leads a child by the hand, a child as pale as any of them but who, instead of a smooth glide, bobs along like a bird. Slices of grey cut through the water in restless circles. Dragonflies dart and dip feet above the surface.

Sarah rests her head on my shoulder. She still smells of guava, the juice from the seeds on her hands, and she smells of mossy earth and sweat.

“Today was a good day”, she says.

“Yeah.”

We sit there in silence, breathing each other in, and listen to the crashing of the waves.

“Do you think they see us from there?”

I look up at the sky, at the endless scatter of stars and the line of soft bruises that flare out across the night sky.

“Where?”

She points at a bright white spot arcing over us. I know they’re satellites, but I’m not really sure what they do.

“I don’t know”, I say, “but if they do I’m glad they leave us alone, for once.”

“Yeah.”

I pull her in closer.

“Hey”, she says.

“Yeah?”

“How long do you think we have? Before-“

“This building isn’t falling anytime soon”, I say. The ocean below us has started to glow an electric green. A surfacing is coming. Rashida told us they’ve been part of life in the islands for centuries, that fishermen traveling from island to island would get trapped in a surfacing and feel like they’d been traveling for days, but then it’d fade, and only a few hours would have passed. When the sea took us back, surfacing came to us, along with the returning scorpions and dragonflies and djinn.

“Yeah, but what do you mean by soon?”, she says. “Because it’ll be in our lifetimes, definitely, even if it’s not the next few years. We’re the last generation of islanders. Definitely.”

The water begins to churn, and the wind picks up. Thick shadows hover under the surface of the green, outlines soft under the glow.

“I don’t want us to end with us. I mean- you don’t either, do you?”

“What do you mean?”

“Do you see a future for us? When it’s just us here. Are we going to- like M and L, are we going to ever, you know, have a family. Go on. We can’t stay here forever. A child can’t grow up here, we can’t have a family here.”

The wind slows to a stop, and the air is still. The rustling of the leaves falls silent. The roaring of the waves quiet down to a murmur.

“I know you hate the idea of ever leaving”, she says. “And I do too. And of all the ways to see a world end, staying here with you, just the two of us, until this building collapses into the sea is a good one, but we want a family someday, don’t we?”

Shrouded figures rise to the surface and float, facedown, on the still water.

“We’ve got a few days before sunrise now”, she says, and kisses me. Her lips still taste sweet, and her mouth is hot against mine. “Just think about it, okay?”

Everything is slowing to a stop and the world is as silent as death, and I can hear her heart beating through her chest, hear her breath in and out. I hold her, and we stare out into the dark.

#climate fiction#cli-fi#climate crisis#climate change#maldives#magical realism#postcolonial#short story#lit

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Nefertiti and the challenges of reexamining the past when it was done negatively for so long. A white man of europe wants to investigate into Kemet's past but Kemet doesn't want it , regardless to his arguments.

https://aalbc.com/tc/profile/6477-richardmurray/?status=2135&type=status

#rmaalbc

1 note

·

View note

Text

Edward Said

I always struggle to decide which of Edward Said's works to recommend first, so:

Orientalism

The Question Of Palestine

Culture And Imperialism

See also:

The Politics of Dispossession (PDF unavailable)

Peace And Its Discontents (PDF unavailable)

#his writing on music is also incredibly rich and interesting btw#Edward Said#postcolonial literature#postcolonial theory#postcolonial#postcolonialism#postcolonialist#postcolonial reading#🍉#Palestine#free Palestine#original

148 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eine Uni, ein Buch, ein deutsches Bedürfnis

Für die Jungle World haben wir einen Essay über den Holocaust relativierenden »postcolonial turn« verfasst, den die MLU in Halle hingelegt hat, indem sie ganze zwei Semester dem Buch »Den Schmerz der Anderen begreifen« von Charlotte Wiedemann und ihrem revisionistischen Erinnerungsansatz mit fakultätsübergreifenden Veranstaltungen gewidmet hat. Als Antwort auf die für das Wintersemester 2023/24 geplante Ringvorlesung »Erinnerung in Komplexität. Weltgedächtnis und Solidarität« hatten wir Anfang November Alex Gruber eingeladen, um seinen Vortrag »Die Shoah entsorgen, um Israel zu kritisieren. Zur Funktion des ›Historikerstreits 2.0‹« zu halten. Der Artikel befasst sich mit den Gründen für die Begeisterung über Wiedemanns Buch und enthält auch eine Analyse des Buches selbst, die verständlich machen soll, warum Wiedemann eine Anhängerin der linken »Schuldkult«-Legende ist. Er kann hier in Gänze gelesen werden:

AG Antifa Halle: Entprovinzialisierung in Halle.

Die Martin-Luther-Universität liest Charlotte Wiedemann;

Jungle World Ausgabe 2024/17

https://agantifa.com/2024/04/jungleworld-charlotte-wiedemann-eine-uni-ein-buch-ein-deutsches-beduerfnis/

0 notes

Text

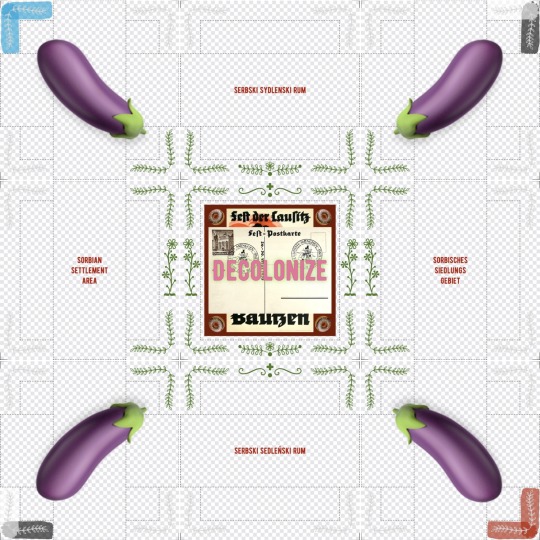

'Decolonize - Die Ravensteiner Gurke'

Digital Collage, 375 x 375 mm, 2024

Fine Art Pigment Print under Acrylic Glass,

Black Aluminium Art Box

Die Ravensteiner Gurke

Hutzenstuben, Trutzburgen, oder Oh-Oh-Oh (doch kein) Osterreiter

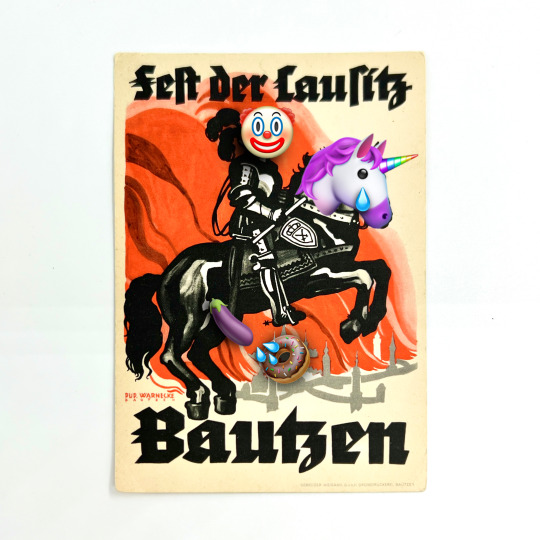

Die hölzernen - manieristisch - druckgeschwärzten - expressiv - gotischen Schnitte des tausendjährigen Bautzens von Rudolf Warnecke erfreuen sich quer durch alle bildungsverbrämten Gruppen jeglicher politischer Couleur immer noch großer Beliebtheit und sind in vielen Haushalten, die ich in der Oberlausitz kenne, noch im Original zu finden. Die Buchhandlungen sind voll dieser Trutzburgen-Heimelei, welche den wohligen Schauer dunkler Zeiten der zweimal abgefeierten (1933 und 2002) tausendjährigen Geschichte als Souvenir mit den TouristInnen den Weg nach Hause finden - nachdem die Kurzweilenden der indizierten T-Shirt Freakshow auf dem Kornmarkt überdrüssig geworden sind.

Ich bin mit diesen altertümlichen Bildern meiner Geburtsstadt aufgewachsen und empfand immer ein gewisses Unbehagen beim Anblick dieser schon zu der Zeit ihrer Entstehung aus der Zeit gefallenen Darstellungen dieser Stadt. Gewiss sind einige dieser Holzschnitte ikonisch in der Darstellung der Stadt und ich möchte dem Schöpfer nicht das Handwerk als Holzschneider absprechen. Aber es fehlt mir an kritischer Einordnung und Reflektion aller AkteurInnen in der Oberlausitzer Kulturlandschaft zu einem Künstler und seinem Werk, der noch 1942 in der ‚Großen Deutschen Kunstausstellung‘ mit der Arbeit ‚Stillende Mutter‘ vertreten war. Dann 1943 ein Titelbild für die Zeitschrift ‚Deutsche Leibeszucht‘. Anzumerken ist, dass der Künstler wegen seiner Weigerung, in die NSDAP einzutreten, gegen Ende des Krieges seine Anstellung als Ausstellungsleiter am Stadtmuseum Bautzen verlor und zum Heeresdienst eingezogen wurde. Soweit so normal: Ein Karriereknick reichte bei vielen nach dem Krieg als Beleg für den Widerstand gegen das Naziregime.

Der zugegeben härteste Triggerpunkt für mich war, als Anfang diesen Jahres in Görlitz eine kleine Ausstellung gezeigt wurde, die den Künstler in eine Reihe mit Alwin Brandes, Hanka Krawcec, Johannes Wüsten, Paul Sinkwitz und Rosa Luxemburg stellte. Das expressiv erstarrte, alle Stadtbrände überdauernde Hexenhaus, als das Symbolbild eines tausendjährigen Bautzen neben einer Abbildung aus dem Herbarium von Rosa Luxemburg schmerzt dann doch sehr. Der Diskurs darüber blieb aus oder drang nicht durch ins oberste Stübchen meines gläsernen Elfenbeinturms im fernen Leipzig.

Vor einigen Wochen fand ich eine Ansichtskarte, welche für das ‚Fest der Lausitz‘ 1935 gestaltet wurde und 1941 immer noch im Umlauf war - wie die Stempel auf mehreren erhaltenen Exemplaren belegen. Der schwarze ‚Ritter‘ auf seinem schwarzen Hengst vor dem brennenden Bautzen. Ist es eine Szene aus dem Dreißigjährigen Krieg, als die kurfürstlichen Sachsen (das Wappen auf dem Schild lässt es vermuten) die Stadt belagerten? In der Folge dieser kriegerischen Auseinandersetzungen wurde das böhmische Bautzen samt dem Markgraftum Oberlausitz 1635 den Sachsen zugeschlagen. Die Perspektive, dreihundert Jahre später, ist eine großdeutsche und Rudolf Warnecke weiß den gewünschten Ton des Regimes zu treffen, welches die geplante Kolonisierung der ‚Ostgebiete‘ mit Ereignissen wie dem ‘Fest der Lausitz’ historisch begründen will. Ab 1937 wurde sorbisches Leben systematisch unterdrückt.

In einer Region, die 79 Jahre nach Kriegsende regelmäßig in der Presse wegen rechter Verhaltensauffälligkeiten gewürdigt wird und sich darüber jedes Mal ungerecht behandelt fühlt, ist der Künstler immer noch im kulturellen Mainstream verankert. Ich empfinde diese Trutzburgen-Kreuzritter-Ästhetik als zutiefst Slawen-feindlich und nicht im geringsten die Ursprünge dieser zweisprachigen Region und Heimat einer autochthonen Bevölkerungsgruppe widerspiegelnd. Die - hoffentlich nicht - kommende blau-schwarze Regierung frohlockt ob dieser braunäugigen Sehschwäche. Regelmäßig erscheinen vor meinem inneren Auge rotierende Rundumleuchten, wenn dieser Tage der Künstler und sein Werk aufploppen. Das ist nicht zwingenderweise der Aufruf zum Bildersturm, sondern lediglich eine Aufmunterung, mal eine andere und ich betone, nicht-identitäre Perspektive einzunehmen.

#SB2130#Bernhard Schipper#Neue Sorbische Kunst#leipzig artist#nsk folk art#Decolonization#anti colonialism#SorbianSettlementArea#SerbskiSydlenskiRum#SerbskiSedleńskiRum#SorbischesSiedlungsgebiet#Bautzen#Budyšin#Wenden#Sorben#Serbja#Serby#sorbisch#Sorbs#autochthon#indigen#postcolonial#artisticresearch#RudolfWarnecke#undoingcolonialism

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

#national trust#mary beard#octavia hill lecture#colonial links#historic houses#social reformer#octavia hill#far-right#british politics#2020 report#colonial loot#slave trade#british empire#diversity#community engagement award#arts culture theatre awards#actas#royal society#london#postcolonial#wokery#british museum#classics#cambridge university#newnham college#royal academy of arts#hilary mcgrady#heritage#culture wars#historic collections

0 notes

Text

Chapter 3: If Ten Years Suffice For Somaliland … From Building States

The @UN's 1950 decision to grant #Somaliland independence within 10 years had a significant impact on other colonies. The UN Trust Territory of SL was established under Italian administration with a compromise agreement promising detailed guarantees for the population & strict restrictions on Italy's power to claim land & natural resources

Continue reading Untitled

View On WordPress

#Aid And Development#Book#Colonial#Colonial World#Colonization#Decolonization#Development#Eva-Maria Muschik#International Community#International Organizations#Libya#Postcolonial#Somaliland#Sovereign States#Sovereignty#UN Trusteeship#United Nations (UN)

0 notes

Text

Sooooooo excited to take this graduate seminar in Postcolonial Literature and Theory next semester!! There’s 13/15 spaces taken, so hopefully it doesn’t fill all the way so I can take it… Tbh, I’ve been dying to take a class focused on Postcolonial Lit/Theory. The greats: Edward Said, Frantz Fanon, Babha, Spivak, and many more… also, I took a look at the reading list for the semester, and I’m beyond excited to dive into them.

The dramatae personae of this drama:

- [ ] “Beginning Postcolonialism” by John McLeod

- [ ] “Buddha of Suburbia” by Hanif Kureishi

- [ ] “Pillars of Salt” by Fadia Faqir

- [ ] “Things Fall Apart” by Chinua Achebe

- [ ] “Season of Migration to the North” by Tayeb Salih

January get here already lol!!

😭😭

#Postcolonial#postcolonial literature#middle east#CSULA#British Literature#Anglophone Literature#Global Literature#World Literature#Literary Theory#Literary Criticism#Postcolonial Theory

0 notes