#pie metas

Photo

A very young Stanley Kwan 關錦鵬 (right) directing Leslie Cheung 張國榮 (left) and Anita Mui 梅艷芳 (middle) for Rouge 胭脂扣 (1987). Kwan would win the Best Director title for the film at the Hong Kong Film Awards.

Stanley Kwan 關錦鵬 is not only a famous director from Hong Kong, but also the first well-known openly gay figure in Hong Kong entertainment. He came out of the closet in 1996 (before Leslie Cheung, who did so in 1997), in the documentary he directed for the British Film Institute named Yang ± Yin: Gender in Chinese Cinema 男生女相:華語電影之性別. His works had garnered accolades for their in-depth portrayal of female characters, at the time when women in local movies often did little more than being pretty and screaming a lot.

(Under the cut: Director Kwan's own words on one of his most famous works and a gay film classic in Chinese-language cinema, Lan Yu (2001), in 2022 after BL culture has entered mainstream)

Most BL fans know Director Kwan via his gay-themed film Lan Yu 藍宇 (2001), about the eponymous Bejing university student falling in love with a wealthy, closeted businessman, Chen Handong. The film, based on a popular online novel Beijing Story 北京故事, has remained censored in mainland China for its queer content and its mentions of the 1989 Tiananmen Massacre. Its fate of being perennially censored was never a surprise—the film was shot in Beijing in secret, with the crew pretending to be shooting commercials around the capital. Digital filming also didn't exist then, and so the 100,000 ft + of film had to be smuggled out of China later to be developed.

Lan Yu was a project about love. Of love.

The poster of Lan Yu in Cannes Film Festival (left), Hong Kong (center), Taiwan (right), at the time of its original release.

In 2022, Lan Yu celebrated its 20th anniversary with a 4K remastered version. Among the interviews of Director Kwan made for the celebration was one by The Initium 端傳媒, during which Kwan shared some of his views on Lan Yu, in the context of how public reception of queer media has changed over the years after the film's release.

These views may deviate from what some fans, especially those in BL circles, would expect. Precisely because of that, however, I'm posting them here. After all, maybe, hopefully, Kwan will collaborate with Dd (and Gg) one day. Maybe, fans like ourselves will interact with Kwan on social media spaces one day.

I hope Kwan's views will be kept in mind, considered and respected.

Due to the length of the full interview **, I'm only translating the two parts that are relevant (lazy turtle here 😊):

1.

《藍宇》 雖為華語電影同志片的經典,但過去廿年,關錦鵬卻在不少訪談中提過,電影改編自當年於大陸風行一時的網絡同志小說《北京故事》,而最初他其實並不喜歡那篇小說。

「原著基本上是用偷窺角度去看一段同志關係,特別是集中描寫男體的情色關係,有很多露骨的性愛場面。作者本身是知道這些描寫會令小說受歡迎。」關錦鵬接著說:「但在拍這部電影前,我在 1996 年已經出櫃。而我覺得作為一名同志導演,就更不應該去消費這個題材,所以當我看到原著小說將情色描寫,譬如肛交、口交的過程放大,當時我便跟製片人說,如果要原封不動將小說內容拍出來,我就不做了。」

Although Lan Yu is a classic Chinese-language gay film, in many interviews in the past 20 years, Kwan has mentioned that the film was adapted from the online gay novel Beijing Story, popular in mainland China at the time, and that he actually didn't like the novel at first.

"The original novel basically looks at a gay relationship from a voyeuristic point of view, especially the erotic relationship between male bodies, and there are many explicit sex scenes. The author (of the novel) himself knows that these descriptions will make the novel popular."

Kwan continued, "But before making this movie, I had been out of the closet since 1996. And I thought, as a gay director, I shouldn't exploit this subject, so when I saw the original novel expanding, zooming in on the eroticism -- the processes of anal sex and oral sex, for example -- I told the producer at the time that if the novel's content is to be filmed without changes, I won't do it.”

2.

在《藍宇》面世的年代,電影確實意識大膽。但二十年後,當電影得以重新修復,社會氛圍其實亦有了翻天覆地的轉變。近年不但多了同志題材的作品,甚至大行其道,人人消費,成為一種時令的商業元素。譬如人氣男團會拍 BL 電視劇,而過去幾年的華語電影節,最快售罄的場次,都一定是同志電影。

此情此景,在《藍宇》剛上映的年代簡直不可思議,電影當年在香港的票房談不上亮眼,普羅大眾對同性戀故事有所抗拒,而本身就是同志的觀眾,想看卻不敢購票入場,怕被旁人標籤。二十年後世界變了樣,甚至總會看到「腐女」在 BL 電影的宣傳海報前打卡拍照。關錦鵬笑說:「是呀,前陣子的確有朋友跟我說,她其實是一名腐女。腐女族群喜歡看男同志電影,但到底喜歡看什麼呢?她某程度上都承認,想看的就是身體,是兩個好看的男人身體如何做愛。」

然而,這恰恰就是他當初對執導《藍宇》有所卻步的顧慮。當同志題材今日已走入主流,變成一種受歡迎的商業元素,關錦鵬則仍然有所警惕,跟潮流保持距離:「可能有些腐女都會喜歡《藍宇》,但我想未必完全是她們那杯茶。它真正要說的是兩個男人從色情買賣演變成一段感情關係,尤其是魏紹恩替我改編劇本之後,陳捍東這個角色,在我看來不一定是男同志,而是他在藍宇身上找到一些連自己都不知道的感覺。」

但關錦鵬也承認,從好的方向去看,在 BL 作品蔚然成風的助力之下,至少令同志以及 LGBT 性少數族群,相對容易被今日的大眾主流接受:「這是令人開心的。近幾年,特別是年輕人,確實會用比較開放的態度去對待 LGBT 族群。」稍頓,關錦鵬解釋道:「換個說法,關於 LGBT 議題的重點,現在就不再放在色情之上,而更多是感情關係,甚至是性少數族群認清自己身份之後,於生活上如何面對社會。那起碼是朝著一個正確的方向。」

In the era when Lan Yu was released, the film was indeed bold in its ideology. Twenty years later, however, at the time when the film gets its restoration, the social atmosphere has actually undergone earth-shaking changes. In recent years, not only have there been more gay-themed works, they have even become very popular and consumed by all, becoming a kind of fashionable commercial element. For example, popular boyband members are willing to make BL TV dramas, and in the past few years of Chinese-speaking film festivals, the fastest sold-out shows have all been gay movies.

[Pie note: The reporter was unlikely to be referring to Gg and Dd with their mention of "popular boyband members". Instead, they were probably thinking of Edan Lo and Anson Lo from Hong Kong's local boyband MIRROR, who starred in the BL drama Ossan's Love.]

This phenomenon is unbelievable in the era when Lan Yu was first released. The box office of the film in Hong Kong couldn't be said to be impressive. The general public resisted gay stories [Pie note: Hong Kong hadn't decriminalised homosexual relationships until 1991, 10 years before], and the audience who were gay wanted to watch it but didn't dare to purchase tickets, for fear of being labeled by others. Twenty years later, the world has changed -- BL fans can be seen photographing themselves in front of the promotional posters of BL movies.

Kwan smiled and said, "Yes, a friend told me a while ago that she's actually a "rotten woman" (Pie note: = woman BL fan, translated from the Japanese term fujoshi). The "rotten women" group likes to watch gay movies, but what do they like to watch? She admitted, to a certain extent, that it's the body. It's the body, how two good-looking men's bodies make love."

And yet, this was precisely the concern that made Kwan hesitant to direct Lan Yu at the beginning. As gay themes enter the mainstream and become a popular commercial element, Kwan has remained vigilant, and has kept his distance from the trend: "Maybe some "rotten women" enjoy Lan Yu, but I don't think (the film) is entirely their cup of tea. What the film really wanted to express was how two men evolved from a transactional sex relationship to an emotional relationship, especially after Wei Shaoen adapted the script for me. The character of Chen Handong, in my opinion, didn't necessarily have to be a gay man; instead, he found on Lan Yu a feeling that even he himself couldn't understand.”

But Kwan also admitted that, from a better perspective, with the aid of popular BL works, it has become relatively easy for gays and LGBT sexual minorities to find acceptance in today's mainstream: "This is a happy thing to see. In recent years, especially young people have indeed treated the LGBT community with a more open attitude.” After a short pause, Kwan explained: “In other words, the focus of LGBT issues is now no longer on salacity, but more on emotional relationships, and even, on how sexual minorities face society in their daily lives after recognising their (sexual) identities. At least it's moving in the right direction.”

** None of you see this footnote, but a copy of the interview without a paywall can be found here. 😊

146 notes

·

View notes

Text

Calling all BL academics! You should check out Intersections: Gender and Sexuality in Asia and the Pacific Issue 49, June 2023. It's devoted to Thai BL and it's Thai scholars, publishing in English, and available free. So basically everything I ever wanted.

Thai Boys Love (BL)/Y(aoi) in Literary and Media Industries: Political and Transnational Practices

- This is the introductory article. One interesting takeaway is that there's a market for western M/M romance in Thailand and I'm dying to know what sort of titles have gotten Thai releases.

Chinese Historical BL by Thai Writers: The Thai BL Polysystem in the Age of Media Convergence

- I didn't read this one. It's about the phenomenon of Thai writers writing danmei set in ancient China.

Authorial Revisions of Boys Love/Y Novels: The Dialogue between Activism and the Literary Industry in Thailand

- This one was super intersting. It was about how the backlash to certain problematic tropes affected both revisions to Y novels and their tv adaptations. It uses Jittirain as a case study and includes passages from 2gether that were rewritten.

Boys Love (Yaoi) Fandom and Political Activism in Thailand

- This article has a lot about Not Me, both about the backlash to the novle due to it being originally a GOT7 fanfic (allegedly) and the political context for the series. It also discusses a few other series related to the youth movement and marriage equality.

Heterosexual Reading vs. Queering Thai Boys' Love Dramas among Chinese and Filipino Audiences

-This really only covers up to 2019 and as we all know everything is changing fast. I'll be interested in future scholarship that covers the current period. Basically expands on some of Baudinette's work.

Provincialising Thai Boys Love: Queer Desire and the Aesthetics of Rural Cosmopolitanism

-I just skimmed this since I'm not familiar with either series mentioned or the rural culture of Isan.

#bl meta#bl scholarship#thai bl#2gether#2gether the series#not me#not me the series#the eclipse#the eclipse the series#cutie pie#cutie pie the series#you can take me out of academia but not the academic out of me

798 notes

·

View notes

Text

I like to think that one of Mobius' past habits, before he was reset, was to go to this tva room to eat his delicious slice of pie at the most stressful times. Unconsciously he guided and welcomed Loki into his comfort zone, but not only that, he managed to communicate his anger and fears to Loki.

#mobius#owen wilson#loki#lokius#tom hiddleston#time husbands#husbands#loki 2x02#pie room#mobius analysis#loki meta

336 notes

·

View notes

Note

Herewiss is right- I too would be more interested in a steak pie than the boobs of some girl who I don't know

(chuckle) He’s the voice of pragmatism, that lad. As regards the steak pie, the recipe for that will be going into the Food and Cooking of the Middle Kingdoms site eventually.

…It occurs to me suddenly that the test shots I did of him in the set that was going to stand in for his room at that inn never did progress to a finished version. Well, whatever… here’s one. (Just re-rendered, as the original image was rendered using an out-of-the-box camera and not a custom one, and hence was blurry.) (No cat in this one, unfortunately. Cat now included. ...And why not? He's got lines, after all...) :)

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

speedpaint vid

Colour wheel challenge I did using suggestions from Instagram. Was fun but I took almost a year to finish it lol

Individual images under the cut

#drawing#digital art#fanart#fan art#krita#colour wheel challenge#color wheel challenge#knuckles the echidna#garfield the cat#spongebob squarepants#kermit the frog#bluey heeler#meta knight#eduardo#pinkie pie#veez art

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

i could VERY well be overthinking this especially because MtG is not necessarily BG canon, but learning zevlor is officially UBR / blue, black, red in MtG makes me look at all his lines of dialogue with a new light, hes very strategic yes but also rather scheming i think. i get as a hellrider he probably Had to be for the sake of survival at any cost, but definitely some of his phrasing sounds "make them think its their idea" style of manipulation.

For reference: Zevlor, Elturel Exile

very cool.

after the above dialogue he says implicating kagha is initially the problem you can suggest HE "get rid of her" which causes these:

they seem so carefully phrased to:

not get his own hands dirty

not put the tieflings in his command at risk

you are an outsider to BOTH groups and thus the potential neutral third party to be blamed rather than him or the tieflings, especially good if you fail and/or die.

also, if you ask him to pay you he doesnt bat an eye, he just shrugs and says he'll scrape together what he can.

His mtg artwork seems to imply being controlled by the absolute, but he also has this quote when you try to tell him it's not his fault he was enthralled by the Absolute:

I'm always a fan of black in mtg used as a 'good' color when its so often interpreted as evil and i think Zevlor here is a cool example of it.

#zevlor#bg3#mtg#GRANTED. his mtg artwork seems to imply being controlled by the absolute#BUT ALSO. he did say that it takes control of something that likely starts from within#NOT evil btw. do not misinterpret me#always a fan of black in mtg used as a 'good' color when its so often interpreted as evil and i think zev is a cool example of it#interesting implications because white is usually the 'community' color so i wonder if he instead views the tieflings#as an extension of himself or similar#although. his card i as i said i think implies the absolute's control so he could probably be just. nongreen regularly#which is HILARIOUS btw.#nongreen tiefling from hell: fuck druids#but again im overthinking silly mtg coloring#*clenching fist barely containing my excitement for color pie interpretations*#bg3 meta

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

few months ago i made these lil designs based from the mane 6 and some elementals (some may look little bit messy due to the lines showing- SORRY-)

#fanart#kirby#mlp#crossover#design#meta knight#my little pony#pinkie pie#rainbow dash#rarity#twilight sparkle#applejack#fluttershy#mane 6#fanartist#elemental powers

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

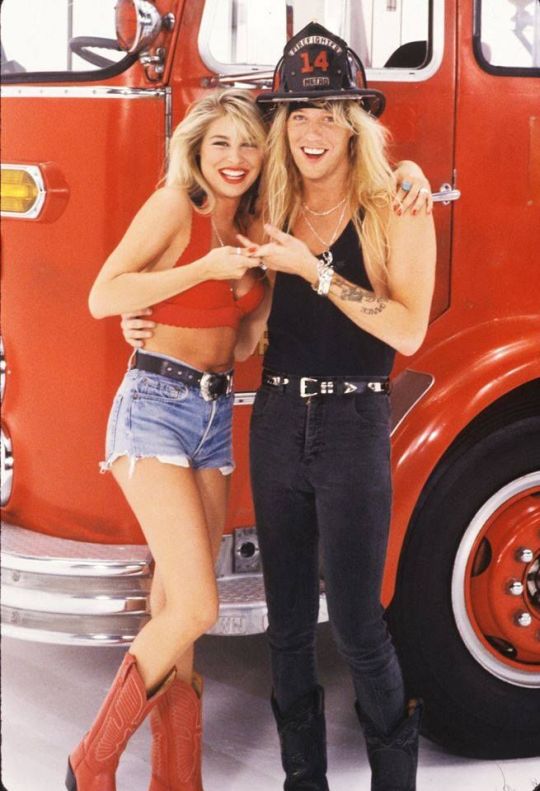

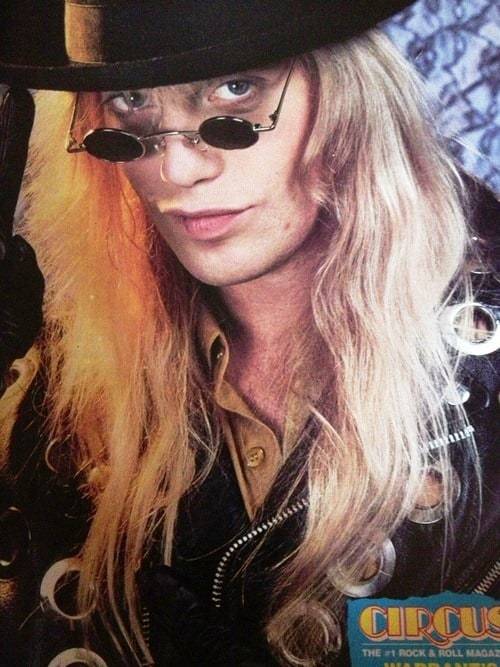

You are not immune to Jani Lane and his sweet face

#Jani lane#bobbie brown#cherry pie#cherry pie warrant#Warrant#warrant band#warrant 80s#hair metal#glam meta#glam rock#80s hair metal#80s hard rock#80s rock#this is propoganda <3

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

These are from like 10 months ago at the beginning of my current Kirby hyperfixation, but I still like these funny little doodles hehehe

#familial affection#Kirby and bandee are the sweetest brothers to each other#also I love the Kirby anime pie monster episode so much haha#Kirby#bandana waddle dee#bandee#meta knight#art

235 notes

·

View notes

Note

Between Dean and Sam: who prefers to be liked, and who prefers to be right?

Hi Nonny, thank you so much for the ask!

I think the easy answer is that Dean prefers to be liked and Sam prefers to be right. Dean has more friends, is more malleable, and has a huge, life-destroying fear of aloneness at his core, while Sam is Mr According to the Lore Research Boy who is often distant and intellecualizing, so this is a natural conclusion.

But actually I think that, like many people in high stress occupations, they both vastly prefer to be right and don't actually care that much about whether people like them or not.

In nursing, it's a truism that certain sub-disciplines--ICU, PCU, NICU, OR, ER--are full of "strong personalities"; which is what we call people who are excessively competent, just want to get the job done and get it done right, and don't really give a fuck about much else. Partly this is because people who are at baseline inclined towards a combination of technical competence and adventure tend to go into those difficult and high stress disciplines and partly it's because once you're there the job winnows everything else out of you.

That, to me, is Sam and Dean. They are "strong personalities". It's not that they don't have friends (although it's canon that in the early years part of the job is explicitly stated to be leaving your friends behind and not getting too close); it's that their friends are expendable, they themselves are expendable, everything is expendable except family and the job--and the job involves getting things right or dying.

Look at how they treat their friends. Look at Kevin, Garth, Rowena, Crowley, often Cas, even each other. They are frequently mean, insulting, belittling of others' value, and interacting with their friends like autistic children who bond through parallel play; except the play is "bleed for the Winchesters".

They both of course do have the basic human need to be seen and loved--which each expresses in their own natural way-- but that isn't at all the same as wanting to be "liked", and they both largely confine their need to be loved to a few select people. Everyone else goes in the "to sell for a corn chip if my brother is hungry" resource pile.

This is very much not me insulting them or saying that they're deranged or actually the bad guys or whatever. The way the universe of the show is set up, they are right. Their world is a huge ICU full of dying patients that's also on fire. In some ways the whole show is just a 15 year argument about how to be right when everyone is dying around you. Give up? Throw out your phone? Push it all down until it comes out in violence and alcoholism? "Like" is small and easily sacrificed compared to wading through the big stuff and doing your best.

#sam winchester#dean winchester#spn meta#my stuff#asks from the awesome headcanon nonny#even in heaven where dean could see whatever dead friend he wanted whenever he wanted#he decided to go for a drive until sam died instead#and even in the kinder gentler world of the 'prequel' when he got bored and wanted to leave heaven#he went looking for wtf was wrong with his parents#and ended up saving the universe again#instead of like... having pie with jo and ellen?#that man doesnt give af

52 notes

·

View notes

Photo

孤鴻號外野,翔鳥鳴北林。

徘徊將何見?憂思獨傷心。

— 魏晋·阮籍 《咏怀八十二首·其一》

The lone swan goose wails in the wilderness,

The flying birds call in the northern forests.

What’s there to see in the lingering?

Worried thoughts and a solitary, wounded heart.

— Ruan Ji (210-263 AD) “82 Songs of Dispositions, No. 1”

孤雁不飲啄,飛鳴聲念羣。

誰憐一片影,相失萬重雲?

— 唐·杜甫 《孤雁》

The lone swan goose doesn’t drink or eat,

Flying, wailing its longing for its flock.

Who would pity that piece of shadow,

Lost in the million layers of clouds?

— Du Fu (712-770AD) “The Lone Swan Goose”

Happy New Year everyone! 🎉🧧

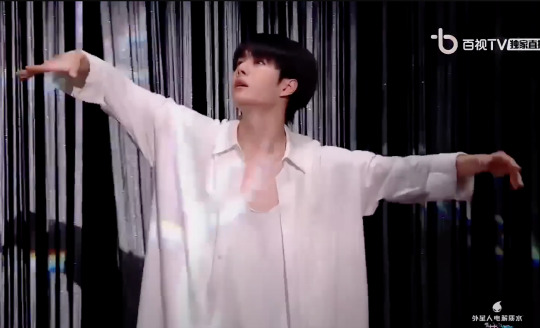

Below the cut, I’m offering my interpretation of Like the Sunlight, based on the lyrics and Dd’s performance on NYE. Unlike other interpretations I’ve worked on, I’m keeping this one free from the influence of what I’ve found on the Chinese internet, whether they are interpretations from fellow fans, explanations from those involved in the production, or reviews by the media—for reasons I shall explain afterwards.

This is strictly the product of my brain, my senses, based on the words, the stage art, the choreography.

As a warning of sorts, my interpretation isn’t one of positivity, or even, one of blissful happiness. It also isn’t candy-ish. However, I do believe this song, this performance is deeply personal for Dd, revealing, sharing a facet of him that with his fame, he can no longer say in words. And in doing so with music and movements, and on one of China’s biggest stages no less, he’s letting us see that side of him, and fulfilling what he sang in Nian:

為溫暖 也為尋常的人間 Stand up.

For warmth, and for the ordinary humankind, stand up.

(Under the cut: Yes, this meta is also very, very long. :) )

For reference, I’m using the English lyrics translation by Xiaoman, and the official performance video posted by SMG. I'll denote the time of the lyrics (Xiaoman) video by the notation “LV 1:00″ for the 1st minute mark, and PV 1:00 for the same time mark in the performance (SMG) video. Sorry this is a little clumsy! I haven’t thought of a better way to do this.

To start, perhaps we can start with the simplest questions? As with any story, we’d like to figure out the time, the place, and the characters.

Time is the easiest—it’s provided in the first line of the lyrics (LV 0:20). There’s a slight mistranslation in the video; the line actually specifies two solar terms in the Chinese calendar—清明 Qingming, which falls on the 4th or 5th of April, and the one immediately after, 谷雨 Guyu, which falls on the 20th or 21st of the same month. Hence, this line of lyrics is better translated as: The Qingming winds are blowing, waiting for Guyu to sow the seeds. The time of when the conversation in the lyrics happens can therefore be estimated as around mid-April.

Is there a significance to this? Yes. The Chinese calendar divides the seasons differently from the Gregorian calendar, and Guyu is the last solar term associated with Spring. Spring is well on its way at the time of the song. It’s almost over.

Next, the place. This one is quite simple as well. It’s the wilderness, with wide open air where the the starry skies can be seen, with forests and its many trees, with mountains where beasts can roam.

The characters. This one a little trickier ... far trickier. The lyrics never specified who they are—in fact, the narrator doesn’t even know the name of who he’s talking to.

Who is the narrator, by the way? There are three pronouns in the lyrics — “I” (我), “You” (你), and “It” (它). Can we identify them?

Let’s start with the “It”, because the syntax actually makes it quite clear what “It” is — it’s the Lonely Nights. While Lonely Nights is plural in English, it’s introduced more as a character in the lyrics. Hence, the use of “it” rather than “they”.

And what does this “It” do? How does it interact with the other two characters, “I”, the narrator, and “You”? The lyrics says, Lonely Nights drifts away like fallen leaves of Autumn, and renews itself, like new leaves budding in Spring, on the tree branches (LV 1:17). It has a cycle then, a routine—usual as, the narrator says, the world will go on (LV 1:29). The time of renewal, he says, decides when and the narrator, the “I”, and the unnamed “You”, will meet.

This means the narrator is familiar, comfortable with Lonely Nights. He’s someone who has accepted Lonely Nights as part of life, as the way things are, as like the seasons, which may appear to come and go but don’t really, truly leave.

Nights, of course, share the same cyclic character as the seasons. They leave at dawn, return in the evening. But the narrator is specific about the kind of nights he is referring to.

They are lonely. Not only are his nights like clockwork. His loneliness is also like clockwork.

What else do we know about the narrator? We know that he has been going on long journeys, journeys that are always restricted by time, that force him to hasten his pace (LV 0:08). The translation of 趕路 (literally, rushing the road) as “rush” is technically correct, but what “rush” doesn’t convey—no single English word can convey it, to my knowledge—is the implied nature of the journey. It’s long; it invites the image of the traveller hurrying day and night without rest, whose time and effort can afford to make the journey happen and not much else. Who sees, as the journey happens, the journey being his primary task.

Such journeys, expectedly, often serves important purposes. They are often related with something life-changing, or critical for survival. Swinging by the coffee shop before work isn’t 趕路, for example, even though the coffee-deprived person may be very rushed, and may feel they can’t live without the coffee.

The narrator has gone on such long, hastened or “rushed” journeys many times. He has done it while the “You” he was talking to have dreamt for a long time.

This still isn’t specific enough, isn’t it? Not for us to understand why the narrator’s perspective is the way it is; why he equates the Lonely Nights with seasons, talks in the language of nature and not of urban life, of civilisation. The Chinese word corresponding to the most … civilised word in the English translation, “campfire” (LV:58), is 篝火. “Camp” is associated with human activity; it sounds artificial. 篝火, nonetheless, doesn’t originally mean campfire. It’s a smaller fire, lantern-like, protected by a cover weaved from bamboo. Likewise, the light in the narrator’s palm (LV 1:56), the gift for “You”, is actually specified in the lyrics as 螢火—the light from fireflies. The narrator being a member of nature is further suggested by his not being afraid of the mountain beasts—he watches the starry skies with them (LV 0:29).

Do other places in the lyrics offer more clues to who, or rather, what he is? Is there another spot in the lyrics that refers to something journey-related, and dreams? If so, that would allow us to draw a parallel and perhaps, deduce the identity of the narrator and “You”.

There is. It can be found near the end of the song (LV 3:49): Like the green grass having a dream of falling snow; like the flying bird passing through layers and layers of dark clouds.

If we apply this parallel in description, the conclusion would be …

The narrator is a bird.

Hence, his comfort around with the beasts, while, notably, also not being one of them. While the contemporary Chinese word for animals, 動物, includes birds and mammals, the lyrics’ word choice of 獸, translated as beasts, generally refers to the four-legged, big and fearsome creatures and excludes members of the avian family, which has its own word, 禽.

The narrator being a bird is implied by the dance choreography, the most obvious being at PV 2:59 where he flaps his wings:

What about the “You” the narrator is talking to then? Applying the same parallel, it would be the green grass, or something like the green grass—young (green), helpless in its inability to escape the seasons, the weather. It’s fearful. Anxious. Dreaming of and already dreading the winter snowfall in April. It’s vulnerable; depressed, some may say, prone to cry with the knowledge, the sadness that Spring will soon leave, not caring enough to stay (LV 4:16) to keep it warm.

But the “You” can’t be just the green grass. The early parts of the song make clear that this “You” not only doesn’t have a name, it shares certain qualities with the night. It’s found among the shadows of the trees under the starry skies (LV 0:29-0:47). It’s awake, if silent, in the night hours (LV 0:47). Dawn is the time the narrator asks for it to tell its name (LV 2:26), implying that the narrator is not expecting it to stay after sunrise.

More importantly, this “You” is who the narrator asks to wake up, like the sunlight. This critical line (LV 3:18) that leads to the climax of the song, that is the song’s namesake, is a suggestion, a plea. This may not be obvious in the English translation, because English doesn’t have an equivalent sentence building block in Chinese known as the sentence-final particle. Such particles—the 吧 (pronounced “ba”) after 像陽光那樣醒來 Wake up like the sunlight in this case—serve the important role of conveying the tone of the speaker. Punctuation marks were not introduced into standard Chinese texts until the early 20th century, and so, such particles are critical in communicating what the speaker actually means in written texts.

Here, the narrator is suggesting. He isn’t commanding. 吧 is softer, more polite than that. He’s asking. Hoping.

The suggestion, the plea for “You” to wake up like the sunlight also implies something important: the waking up hasn’t actually happened. That is only the wish of the narrator; the wish of the narrator that “You” will, one day, be like sunlight and be everywhere, on the crossroads, in the journeys, at sunrise, while dancing in the wind (LV 3:30). The “You”, therefore, has so far remained in the night. Echoing this interpretation, in Dd’s dance, at sunrise (PV 3:28) the “I”, the narrator’s movements turn frantic; he runs around and reaches, searches, grabs, until he finally collapses on the floor, curled up in a fetal position, despaired (PV 4:04):

He made a desperate attempt to hold on, and failed.

If the narrator is a bird—a lone bird—the lone bird is alone again. He has lost his companion for the night, his “You”. We know something more about the relationship between the narrator and “You” from this: the narrator doesn’t have the power to change the nocturnal nature of “You”; he doesn’t have the ability to transform “You”, overnight, into his company under the sun. All he can do is to bring “You” small morsels of light, in the form of small fires under bamboo covers, of lights from fireflies. The lyrics tell us what these two lights, both much dimmer, and weaker than sunlight, stand for: the stories the narrator can chat about, the small joys he has picked up during his (daytime) journey.

The narrator and “You” are not soulmates. Not yet. Their separation at sunrise explains why the narrator doesn’t know certain things about “You”, such as “You”s name. That the narrator wishes for happiness for “You” (LV 3:57), no matter where one goes (the lyrics actually doesn’t specify who’s the one going)—the phrasing making this a well-wish—not only suggests that the narrator and “You” are parting ways, it also suggests the narrator doesn’t always have a clear knowledge of where “You” will be.

But the narrator wants them to be soulmates. Exchange not only their heart 心, but their true heart 真心 (LV 1:14). Despite his unfamiliarity with certain parts of “You”, he also has insights about “You” that run deeper than names and locations; he knows “You” hasn’t made peace with the Lonely Nights like he has—it’s one of the reasons of “You”’s sadness, along with the passage of time, along with the carelessness of Spring (LV 4:07). He comforts “You”, tells “You” not to cry (LV 4:17). The tree branches where Lonely Nights renews itself, he says in the end, will not only be the time they shall meet again, but where beauty and goodness 美好 returns, along with Spring (LV 4:21).

This doesn’t sound like a happy story, does it? Moreover, some of you must be thinking, mumbling as well — Huh??? So Dd is singing a song about a bird and some … nighty grassy thing? What does that have to do with him? With anything?

Here’s when I refer to the poems at the start of the post. They are there, of course, for a reason.

You see, the lone bird — the lone migratory bird, in particular — has had a long history of symbolising uprooted people in Chinese literature. By uprooted, I mean the people have been separated from their homes, their home towns, and it doesn’t matter whether the separation is voluntary. Natural disasters like floods, man-made disasters like wars may have forced them to leave, or they have moved because better opportunities present themselves elsewhere.

Like the Sunshine is, I believe, about this lone bird, this displaced group of people.

True, the lyrics never specifies the kind of bird, but the narrator’s awareness of the seasons is the first, if faint clue of its migratory nature. The second, more significant clue is in the stage art — the existence of wide bodies of water and the creatures living in it, neither of which are found, or even implied, in the lyrics.

This bird flies across, or above the waters (PV 3:49):

Still, you may ask, there are many migratory birds. Why have I picked poems about the lone swan goose? Why am I imagining it as the narrator of the lyrics? My reasoning is this: while two species of migratory birds have made frequent appearance in ancient Chinese poetry—the sparrows and swan geese—it’s often the latter that was alone. Poets of old tended to depict the sparrows as happy birds, with the sight of their migration signalling the arrival of Spring. As importantly, perhaps, they were usually portrayed as flying in pairs. The swan geese, on the other hand, were associated with the autumn migration, the impending winter and the less-than-happy sentiments from long journeys away from home. Their calls were described as wails. They were often portrayed as messengers carrying morsels of news, of deep yearning, from loved ones who were too far away. Swan geese naturally fly in flocks. They also mate for life. The lone swan goose therefore suggested separation and abandonment. Loss.

But but but ..., you may argue. Why can’t it be … single and available?

* Smiles *. As a culture that heralds collectivism, being alone is rarely, if ever, considered a choice in traditional Chinese thinking. In the old times, in particular, it was considered, assumed to be a less-than-ideal thing that had happened upon the individual. At best, it was some sort of misfortune; at worse, it was a bout of irresponsibility. Both poems about the lone swan goose that started this post are more than a thousand years old. Both are depressing.

This has something to do with what a home means in traditional Chinese culture.

In the Western world and in the 21st century, we associate flying away alone from our childhood homes as part of growing up. It has its challenges, but it’s also exciting. It’s about having an adventure and seeing the world. People don’t think of it as an act of abandoning one’s home, or one’s home abandoning them. The location of the physical home doesn’t matter as much as where those who love you, and those who you love back are.

Home is where the heart is. That’s the saying.

Meanwhile, home in traditional Chinese culture is more accurately described as where the bloodline is. It’s where your ancestors are buried, where you bow before row after row of memorial tablets on Qingming. Where the elders expect their descendants to not only take care of them, but shoulder the responsibilities of maintaining the house and the bloodline, and bring glory to them all.

To be away from home for any reason, even if it’s out of necessity, therefore evokes feelings of guilt, in addition to the sadness and loneliness of being a permanent stranger somewhere else. The longstanding belief that home is where one’s ancestors are means assimilation is next to impossible, both socially and emotionally. Others in the new place don’t think of the migrant as one of them. The migrant doesn’t think of themselves as one of them.

The traditional term for people who live away from their birthplace, their ancestral hometown, is 羈旅. Many of you may be familiar with 羈 — it’s the same character as in Wuji 無羈, and originally means a bridle. 旅 means to travel. Putting the characters together, 羈旅 is a bridled traveller. In ancient times, a bridled traveller could’ve lived in his new town for years—decades, even—and be still considered a guest in the town and his house, little more than a restraint that had kept him there. The consequence of such lifelong alienation was that the deathbed wish of many such migrants was to be taken back to their home towns for burial. 落葉歸根, they called it. The fallen leaf returning to its roots.

Fallen leaves are considered uprooted, rootless.

Fallen leaves appear in the lyrics of Like the Sunshine as well (LV 1:17), describing the passing of Lonely Nights.

In 2023, China has, inevitably, absorbed some of the Western perspectives about leaving home, the independence and self-reliance it nurtures, the freedom it brings. But the old thinking remains, stubborn and at constant war with the new. The Chinese word for freedom 自由 didn’t enter the Chinese lexicon until the 19th century, as an import from Japan. Chasing one’s dream, often the cause of leaving home, is also a contemporary concept—in old Chinese usage, to dream is not a particularly good thing. Ancient Chinese preferred something more tangible. More practical.

The dream in Like the Sunshine is an example. The dream isn’t a particularly good one—snow is a danger for the green grass.

Whereas, Confucius was already preaching filial piety, laying out its rules and rituals 2,500 years ago.

Government policies also reinforce the feelings, and “guest” status, of the modern bridled traveller. Chinese are attached to the provinces of their birth by their 户口 hukou, a household registration system that allows the government to control the flow of its population within the country, which is arguably necessary due to the vast disparity in resources from province to province, and between the villages and the big cities. When a Chinese moves somewhere else—to a big city like Beijing, for example—their hukou doesn’t move with them. Without a Beijing hukou, the migrants’ rights to buy a house, even a car, in the city are restricted. They are often overlooked by companies, which prefer to hire Beijing hukou holders, while the migrants already have little safety net should they fall into economic hardship, not being eligible for most of the local government assistance programmes. Children must go back to their hukou’s province for their college entrance exams, when top universities admit students with a Beijing hukou at a much, much higher rate — in 2011, Beijing University’s admission rate for Beijing hukou holders was almost 30 times that of Dd’s home province, Henan.

While a points system is in place for those who wish to apply for a Beijing hukou, the latter remains so difficult to get, so coveted that there is a black market for it—the price tag justified by the need to “make the right connections within the government”, i.e., to bribe. The current price isn’t something I’m privy to, but back in 2012, the state media reported that it was already at 500,000 RMB (72,480 USD).

It’s a sum of money the poor can't afford, not to say such a purchase is, of course, not exactly legal.

Yet, there are still so many modern bridled travellers in China that they have a collective descriptor: 漂族 The drifting race. 漂, meaning to drift and pronounced “piao”, also appeared in the lyrics, describing the fallen leaves that, in turn, describe the Lonely Nights (LV 1:17). Fallen leaves, as mentioned before, have been used to describe the rootless—and specifically, those approaching the end of their lives.

Drifters who have drifted to Beijing are known as 北漂 — 北, or North, is from 北京 Beijing, which literally means The Northern Capital. In 2021, this population amounted to more than 8 million people, or 38.5% of the city’s permanent residents.

This population also includes Dd and Gg. Dd and Gg may be stars, but at the end of the day, they are just another two youngsters who have left their homes for a big city to try their luck.

For Dd, in particular, Beijing isn’t even the first place he has drifted to. His first was not only another city, but another country—South Korea. Of his short 25 years on this planet, he has spent 14 of them as a bridled traveller, and many of these days he wasn’t even bridled, his home being a hotel room somewhere. Everywhere. Meanwhile, expectations remain that he should view his birthplace, the city of Luoyang in Henan, as his home. He has been repeatedly asked to perform in Luoyang / Henan’s dialect, even though he has, also repeatedly, said he isn’t fluent in it (two examples from CQL’s promotional period alone: Vid 1, 1:55; Vid 2, 5:47). His selection of Cola Chicken Wings as his favourite dish for Chinese New Year (Vid, 3:56), being a cute candy aside, also suggested a certain degree of detachment from his supposed home city. Most people would have named a dish from their home place without prompting.

Yet, strangely perhaps, Dd has also exhibited a strong affinity to Home, as a concept. When it matters, his connection to his ancestral home seems almost tighter than other’s. There are hints, too, that he’s meant to be living in a home-is-where-the-heart-is home, when, with his history, many may assume that he’s comfortable, if not more comfortable with being uprooted, being rootless.

Dd was there to help with the rescue effort for the floods in his ancestral home of Henan. He was there despite of the skepticism he must know he would get, and he did get it. Meanwhile, his years drifting in S. Korea, in Beijing haven’t appeared to have assuaged his fear of the dark, which may, perhaps, be as well understood as his need for companionship. Not the “let’s go party together” kind of companionship—Dd doesn’t have a reputation as being a party animal, not even in the most gossipy, most vile of YXH blogs—but the “let’s-be-together-when-it’s-dark-and-silent” kind of companionship, the kind that requires far more closeness … intimacy, if one will, and trust. As night falls, he appears to require the presence of another human being to feel safe, to fall sleep. On record, he had sought such presence by tactile confirmation, as his old team mate once pointed out (0:44), or by finding an imitation—the voice from a non-hostile, trusted source such as the CCTV Sports Channel (23:15).

I can’t help but feel: both of these are pale substitutes of what Dd can get from a home-is-where-the-heart-is home.

Some people don’t mind being alone. Some even enjoy being uprooted. Dd doesn’t seem to be one of them.

He isn’t the only one. There are many other young Chinese drifters who have elected to drift, but also wish for an ancestral home, a home-is-where-the-heart-is home, to return to at the end of the day. The hardship of the drifting race has been well documented. Many spend the night alone in the tinniest, cheapest apartments in their new city, exhausted from a day of “rushing”, depressed from missing their loved ones and anxious about their new environment, their new job, their being from a poor province that big cities tend to look down upon.

They worry. Many have promised their families back home that they will mail back money with their higher income in the city. After all, a good fraction of them only manage to secure employment in the big cities after their family—their parents, their grandparents—exhausted most of their savings to pay for their college education. They want to repay these elders who love them. They want to bring glory to their blood line. These expectations, both from others and from themselves, have never gone away.

They cry. At night, mostly, when nobody can see them, because they must put on a brave, mature face when the sun is up. With the guilt associated with leaving home, with the investment of time and money and effort required, the decision to leave is seldom made lightly, and many of them are set on making their journey a worthwhile one.

As one Beijing Drifter from Chongqing said: Even if I have to get on my knees, I’ll take this path to its end. (Vid,13:38)

If time and space are limited, how would I succinctly describe these drifters? How would I depict them with a simple piece of artwork? I’m no artist, and so, Google is my friend and perhaps, this is what I'll find and show:

(An off-angle shot of this in the performance is found at PV 4:28)

The hunched back, overladen with guilt and anxiety, and often, too, with the weight of expectations. The paper plane, representing their pursue for a better life. Flying high while being small, childlike and vulnerable.

The last three years of Zero COVID policy have not helped with the drifting race’s predicament. Chinese New Year is usually the time the drifters travel home to visit their family, but many didn’t for the last three years. Leaving the capital city, especially, had been heavily discouraged by the local government, for fear those who did would bring back the virus when they returned. Travelling also created a risk of being subjected to involuntary quarantine, or of being given a yellow or red COVID health code that would bar them from returning to the city, too often for long enough to jeopardise their employment.

These lone, migratory birds are, I believe, what Like the Sunlight is about, and who Like the Sunlight is for. The teary faces these drifters don’t allow to see the day, that stay awake and silent after night falls, is the “You” of the song — young (green), worried about their future and the challenges it will undoubtedly bring (winter snow), still not used to the lonely nights and wondering if anyone cares, realising that even the kindest souls can only do so much for them with their own obligations to keep, their own routines to follow (Spring).

The “You” doesn’t have a name because it’s actually a part of the lone migratory bird, the narrator. The “You” is both familiar and unfamiliar to the narrator because it harbors his deepest, most hidden if also the most unadorned and sincere feelings—feelings that must leave, return to the dark when the sun is up.

The Chinese work environment is very much survival-of-the-fittest. Competition is fierce. Work load is brutal. Youth and immaturity, sadness and fears have no place there.

I imagine, Dd chose this song because he, too, has been one of these migratory birds, one who left home at an even earlier age than others, who flew even further away than others. At 25, he has already spent more than half of his life drifting, and this experience must have left a mark on him, he who was (is) so adversed to being in the dark and being alone. One may argue that Dd is so much luckier, that his job now pays so handsomely that the financial woes that plague most other drifters will never touch him again. That is true, but no compensation can alter the fact that his job is also among the most isolating. His every move is watched, his every associate placed on a scale and judged—is Dd too good for him, or not good enough? His hastened journey, his flight through the stormy clouds of c-ent is further darkened by the thick wall of hounding paparazzis and sasaeng fans.

As turtles, we believe his heart has found actually found a home. But we also know that he’s separated from that person for most of the year. We know, too, that because of the common practices in his line of work, because of cultural norms and government policies, he can’t turn himself from a lone migrating swan goose into half of a pair of happily migrating sparrows. He can’t even be seen in the same camera shot with his him. He may not have to worry about money, but he has to worry about the ever fickle, ever brutal public opinion. He may not be anxious about his next pay check, but his industry has been ailing, and many relies on him, directly or indirectly, for their pay check.

At some point, I imagine, there’s got to be a “You” in Dd too. A “You” that is his actual age, not the age of his maturity. A “You” that, after the night falls and all is still and quiet, frets about what will come and that, just like other humans, is prone to being brokenhearted when its trust is misplaced.

A “You” that still doesn’t want to be in the dark, to be alone.

And he must have talked to this “You”, comforted this “You” inside him. He must have done so in the lonely nights, which he has made peace with after so many years of travelling, the lonely nights that he now sees as benign—always returning, true, but isn’t it just like the seasons, with their falling, drifting leaves, followed by their constant renewal on the branches? He must have shown this “You” the morsels of joy he picked up during his day time journeys. A cool skateboard trick he mastered, maybe. A new dance move. A freshly delivered box of limited edition Lego. The company he kept when these things happened; the company that made these thing happen.

He must have wished his “You” happiness. He must have wished it to be like sunlight, to be something that can be out there in the open for all to see and is light and free enough to dance on the journeys with him after the sun rises, at the many crossroads he must pass. To me, what this performance practically shouts to the world is: Dd may be taciturn, but he’s expressive. There are things deep inside him that he wants people to know, to understand, if just so that others who feel the same can whisper “Me too”. He must have been disappointed before, despaired that that hasn’t happened, that his “You” has remained in the night, that this soft, gentle part of him has to be wrapped up and hidden from public eye and he must put on a brave, mature face when dawn breaks. But he’s making peace with that too. After all, the “You” that stays in the night keeps him company when there’s no one else. He recalls the small joys of his life for it, recounts the small joys of his life to it. He exchanges his true heart with it, acquaints himself with his deepest, most unadorned, natural feelings—feelings that he keeps from other humans, from civilisation.

Despite dreading winters, this “You” in him has helped him through the winters.

I would insist that Like the Sunlight is a positive song, in that it’s about acceptance and healing—not the outcome of healing, but the process of healing. At the same time, I also recognise that it isn’t a positive song the way positivity is conventionally defined in their country: that everyone is living a happy, inspirational life, that wounds are no more than plot points leading to a climatic preaching scene. I see open wounds in the dance performance. I see pain, and I appreciate it not because I enjoy seeing anyone hurting, but because unlike so much of their country’s entertainment, it doesn’t pretend that such wounds don’t exist, or that they can be healed and numbed by some stock phrases of encouragement, a few slogans, a chant of core socialist values.

To pretend such things is to make light of pain, to diminish the humanity that makes the pain.

Healing isn’t a game of mathematics, in which fortune in one area cancels out the misfortune in another. Just because one has an illustrious career, or even, an enviable romantic life, doesn’t mean they can’t be hurting somewhere still. Healing is slow. Healing is difficult. Healing is patching a wound, the deep hollowness within, with one firefly light after another. Healing is to have the wound ripped open again and again at the most unexpected, most inconvenient of times, and still believing, insisting that the wound will close one day.

Healing is learning to accept that the hollow is there. To make peace with it. To see it as part of oneself.

Healing is to wait, to be patient season after season.

These aren’t viewpoints that public figures in China can express freely, or at least, without great care. Recognition of the existence of real, open wounds, of the pain they inflict, may be misconstrued as dissatisfaction about the country’s way of life, and the powers that be that make their way of life the way it is. Public figures in entertainment, in particular, are far better off in 2023 being talked about as role models of the government-approved kind of positivity, their work as vehicles for warm fuzziness and slogan-y life lessons. Sunlight is everywhere, always. Sunlight is a reality, never just a wish. Embraces happen under the sun and with the sun, not in and with the darkness (PV 0:40). And such things are to be represented as observations, as what the audience sees, even though the lyrics doesn’t say it, the stage art doesn’t show it, the dance choreography doesn’t suggest it.

Chairman Mao was the Red Sun.

How far does this insistence of positivity go? The following is a digital banner photographed in a Chinese hospital a week ago. The bright red banner looks, and is, congratulatory. Something very happy has happened! What is it about?

This: Good News! On 2022 December 21st, Our ER department has served more than 2 million people (Source).

The surge in patient visits was due to the country’s 180-degree turn in its Zero COVID policy, and the associated surge in hospitalisations and yes, deaths.

The next day, a crematorium’s notice wrote the following about the doubling of corpses it had processed over the course of a week: 受到了群眾的好評和領導的肯定 ... 確保年底前各項工作任務圓滿收官、爭創佳績. (The work) has been well received by the masses and affirmed by the leaders... (we shall) ensure all our year-end responsibilities will have a perfect curtain call, and strive for the best results.

This is how strong the country’s insistence on positivity is. Humans are behind the banner, the notice. Do they understand the less-than-happy, less-than-inspirational sentiments behind the ER visits, the deaths? Of course they do. But this is how much people are being pressured into saying happy, inspirational things these days. This is the length people are going to avoid saying things that are otherwise, at the intersection between 2022 and 2023.

And so, I shall say this again—the above interpretation is entirely my own, from my angsty fic writer’s brain, and have nothing to do with any interpretation, explanation or review available on the Chinese social media, which are all happily, inspirationally and most importantly, appropriately positive. It’s my being obstinate and ridiculous and delusional that makes me disagree with them, that makes me confess the following:

I have doubts about the … honesty of certain things that have been said.

The explanation offered by the studio about the stage art, for example. The explanation says, the art depicts a fantasy, which culminated to the narrator finding his lost home and that union leads to a finale of golden light passing through the clouds, waking up millions of lives and souls.

I have doubts because I have trouble matching it to what I saw. While the exact moment can’t be pinpointed due to the camerawork, the shade of red on Dd’s face suggested that the sun, the golden light, started shining at the PV 3:28 mark. At that moment, the creatures, the lives and souls remain on screen, thriving in the dark, in the nature. As the sun continues to rise, they are lost, transformed into (lifeless) objects from civilisation—things like furniture and laundry lines. Finally (PV 4:24), the lone man appears, united with his home in that he’s carrying it like a burden on his back. Not one life or soul appears after the man and the house did. Dd’s final interaction with the stage art is to walk towards the man, the uprooted house that just had a paper plane fly out of its window.

The stage art thus presents a story that is almost opposite of the explanation given: the rising sun, in fact, drives away the creatures, the lives and souls and nature that accompanied the narrator before. The civilisation the narrator returns to has nothing but a home that is rootless—in contrast its being rooted at the beginning of the performance (PV 0:10)—and its paper plane carrying, one may presume, a fragile childlike dream.

Winter is turning the corner, the explanation says in its conclusion. Warmth has arrived, unexpected. The stage effect, meanwhile, is a wild dance of drifting, yellow autumn leaves. Winter may indeed be turning a corner, but it’s more likely to be doing what the green grass has been dreaming of, afraid of. It is lurking, waiting for the right moment to bring in the cold, the snow.

As such, the stage art goes well with the lyrics—assuming my interpretation isn’t too off the mark. As such, the stage art also, in my (obstinate, ridiculous, delusional) opinion, sets the explanation’s pants on fire.

The thing I can say about the explanation is … it’s positive; it’s a good thing to say on record. Even the flood isn’t real.

Another thing I can say is: to everyone reading this, please trust your senses. Please believe whatever the performance makes you feel is real. Don’t let anyone tell you, this is the proper interpretation. Don’t listen to anyone who says, this is how you’re supposed to think. Including me. Including this post. Even if a language barrier exists, music is universal. Art is universal. Movements are universal.

Okay, this is getting ridiculously long, which is hardly surprising 😊. One last thing. Some may be asking (assuming you haven’t all fallen asleep)—do I think there are candies in this performance?

Frankly, I don’t think there are any on the surface. Not in what was sung, or illustrated, or danced. However …

If you’re a lover / follower of LRLG like I do, you may remember the famous episode (#6, published 2020/12/25) that talked about Dd keeping Gg’s ring in his pocket while he sang. Another confession: the ring part was never my favourite from the episode. Instead, it was this tiny piece of conversation that few likely recall:

(Context: Dd had to make an overnight car trip to somewhere else after the show. Gg was staying. They just joked / wishful thought about Dd bringing Gg with him.)

❤️: You know what to do after you get on the car?

💚: Didn’t you say you’re leaving with me?

❤️: Turn on video conferencing. I’ll watch you sleep.

While fake rumours are officially fake, certain elements have made repeated appearances—such as, Gg and Dd often have their video conferencing on, even when they are doing their own things. They keep each other company that way. And this snippet from LRLG isn’t the only one that further specifies what happens at night—that when they are apart, Gg and Dd would have their video conferencing on when Dd goes to bed, and Gg turns it off after Dd falls asleep. This candy made a strong impression on me because I recalled how much Dd disliked the dark, and being alone, and I thought, how comforting it must be to him for that dislike to be acknowledged, to be taken seriously as a thing to be addressed. I’m an aroace; I can’t say I know much about romantic love. But something I do know about love—any kind of love—is this: it’s to give the other person what they need and not what I think they need; it’s to not question why they need it, to not brush the need off because it doesn’t apply to me, because I don’t understand it.

This three-line conversation was filled with love. Gg, offering what Dd needed matter-of-factly. Dd, being comfortable enough with the offer for him to keep the silliness going.

This offer had to have been made many times before. This offer had to have been received, and appreciated, many times before.

Imagine Dd on his journey after this conversation, him drifting off into slumber while clutching his cellphone, the latter dimly glowing in the dark vehicle as Gg watched him. Who can say that Gg wasn’t, at that moment and at every other moment like this, being the firefly light in Dd’s palm?

He must have made so many firefly lights for Dd. The firefly lights that Dd shows his “You” in lonely nights.

He must have been the fire under the woven bamboo. He in his long coat and oversized scarf, his eyes playful and twinkling like embers, his smile bright and warm and sweet like the fallen petals that mark the passage of time. He must be very good at fighting off winters—he who can’t make a proper snowball to save his life.

And when the lonely nights visit again, when Dd’s “You” is awake and silent and waiting to hear stories, Dd gets chatty.

We all know this, right? Dd always gets annoyingly, adorably chatty when this fire under the bamboo lights up. 💚💚💚

133 notes

·

View notes

Photo

some interesting jelly quotes pt. 2

pt. 1 / pt. 3 / pt. 4

#cookie run#cookie run ovenbreak#metas stuff#blueberry pie cookie#lilac cookie#sour belt cookie#string gummy cookie#lychee dragon cookie#white ghost cookie

262 notes

·

View notes

Note

i like your interesting take on tsumugi as a protagonist. i don't hear tsumugi a lot in terms of meta reasons and appreciation and i'd like to hear your though about tsumugi being a main protagonist please. :)

I'd LOVE to. Protagonist Tsumugi is something I really do think fondly of and often wish for.

Firstly, I think Tsumugi is really the only mastermind who you feasibly could play in a perspective of without making them forget they're the mastermind (a la Izuru). So much of V3 is either pre-planned or run by others on Team Danganronpa that her actual involvement as a mastermind is essentially nil - she's just doing damage control. It would be very easy to foreshadow the reveal without outright revealing that she's involved, the same way as with Kaede in the first trial.

Tsumugi is also the V3 character who has the most vested interest in keeping the trials going and making sure they get solved, because if the trial ends there, then there's no show. I could absolutely see Tsumugi's protagonist interventions ("No, that's wrong!") as being subtle interventions to make sure that the group is on the right track, but justified in her not quite knowing the answers because she isn't an ace detective, she's just a cosplayer with a mic in her ear to tell her when she needs to get everyone back on track.

I also think that playing as Tsumugi would play into V3's greater theme of culpability and the control of the audience. By playing as the mastermind, you are directing the killing game. Within the fiction, you, the player, are personally responsible for what happens here. Again, Kaede plays into this in a lot of ways as well (I think a version of the game where you still play as Kaede at first would serve this AU best), but the slow burn of it all makes the realization that much more horrifying, in the same way as the realization that everyone is Remnants at the end of SDR2. Kiibo as protagonist could also accomplish this, since you'd be more connected to the in-universe audience, but I think Tsumugi would provide an interesting take unique to her where the player is really taking on the role of Team Danganronpa itself.

There's an overarching theme that Tsumugi fits into with previous protagonists, too; Komaru had no connection to the mastermind, Makoto was friends with the mastermind once, Kaede and Hajime were accomplices to the mastermind once, and Tsumugi is the mastermind/accomplice to the masterminds. You get the final entry into this sort of sliding scale of connection to the villain, which in current DR is kind of dangling open-ended.

And she's also the only character in V3 who really plays into Danganronpa's overarching theme of the imposter complex ("plain, plain, plain")! I think it'd be so cool to have a take on the I'm Just Some Guy nature of DR's protagonists that is actually very talented, but still has this low self esteem because of the way they think about their talent. They tried to do this with Shuichi a little bit, but imo it wasn't very effective, because it never really came up; Shuichi's arc wasn't about learning that he is actually a good detective, it was about overcoming trauma. A Tsumugi arc where she learns that her talent is valuable, that she can have an impact on the things and people she cares about - especially when we, as the audience, think she's talking about supporting the other players, but in reality she's talking about supporting the killing game? Oh. Ooooooooh. I love that shit.

I do generally think that they should have done a lot more with Tsumugi's character. And, in fairness to them, there are reasons for Tsumugi being just a quiet background character without much impact - it's the big startling counterpoint that she's secretly the mastermind, compared to the more traditional tropes of the rest of the game; Tsumugi's reveal is what really blows the game wide open and makes you rethink the entire story thus far. I just personally think that there are ways they could've done it more effectively, to really give it that oomph.

#asks#pie-a-rino#and i love tsumugi!! so of course i want her to get a more pivotal role#talk to the mod#meta#tsumugi shirogane#v3#long post#sorry for talking SO much ive just been thinking abt this a lot lmao

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

what makes kinnporsche sex different from most other BL sex scenes is that they're actually vital to the plot*

in most other BLs, the important character development and conversation happens prior to the sex, or after the sex, and not during it. in most BLs, you could do a tasteful fade to black after the shirts come off and the story wouldn't be altered at all. with kinnporsche, that's not the case. the audience needs to see what happens in the sex scenes because they develop the characters and even the plot significantly.

with the drugged sex, we cant just cut to black after porsche kisses kinn because we need to know exactly what lines were crossed so that we understand porsche's reaction afterwards. we also need to see porsche's emotions-- his joy, his teasing, his bliss, during the act-- to contrast to the blank slate of the morning after, when he is hurt and upset.

and the handjob scene has been dissected to hell and back already but it truly was the best example of non-verbal conversation i've ever seen in any show, ever. it wouldn't be enough just to see the anguish of kinn's apology and his kisses he gives as recompense. we needed to see porsche accept his affection and take control of the situation, signaling to the audience that he forgives kinn and wants to move past the hurtful things they both said.

compare this to cutie pie (no hate on it, it's just recent and has some steamy scenes to compare to). the first sex scene could have cut off way sooner-- probably right after lian asked for kuea's consent for the second time. at that point, it had been established they wanted to fuck, they knew what they were doing, and that lian wouldn't hurt kuea. we had no doubts that it would be a good experience for both of them. seeing that depicted visually didn't advance the plot or the characters. that development happened on the couch before and when they woke up the morning after.

i'm not making a moral judgement one way or another. it's totally fine if shows want to depict pretty boys having sex even if it doesn't advance the plot or characters. it's stylistic choice. but i definitely know which style i prefer.

(*ok some of them. porsche's yok-assisted strip tease was for laughs)

#original#kinnporsche#cute pie#kinnporsche meta#i could probably also talk about how kpts' sex scenes are shot a little bit like action scenes but i dont know as much about cinematography#and i dont want to sound like a dickhead#i only went through the first time and the bathroom scene bc theyre what i consider proper sex scenes#and not part of a montage like the others#plus porsche's odd seduction which is just for laughs#will update when we finally get our promised pool sex

253 notes

·

View notes

Text

I know a lot of people are frustrated with seeing old PC's or feeling like we are spending too much time on a particular arc during the BH campaign. I think the best way to engage with Campaign 3 is to recognize that it's more theme and plot driven than character driven. This is going to affect the pacing and storytelling of the campaign, and it's why we shouldn't hold similar expectations for arcs, characters, and story beats with a character driven narrative like C2.

The themes are pretty simple: fate, destiny, and choice (anger/rage/violence were also prominent early in the campaign). Can you make your own path in a world controlled by fate? Where does choice factor into destiny/fate? How has previous choices affected the current fate of our party?

Once you realize this is what's driving the narrative, it makes sense why past PCs are so heavily involved in this story.

Also their inclusion in the story shouldn't be a surprise at this point. They established in the first episode that this campaign would be interconnected with previous campaigns: Three members of EXU joined C3, Orym and Laudna's story have direct ties to VM, and Betrand brought the group together. In addition to that, FCG exists because of the Mighty Nein's actions 6-7 years ago. Ashton would be dead if Essek hadn't stolen 2 beacons, and if Yeza hadn't discovered how to extract the potion of possibility. Plus we've already visited Whitestone.

As for why this campaign feels like one long continuous arc, it's because it is. The only breaks we've had from this "arc" were to rescue Laudna and visit the Gorgynei. Even the trip to break into the museum for Hexum included new Ruidus lore. We've never experienced a campaign where every character's backstory is directly connected to one major story. Yes, even Chetney, FCG, and Laudna can trace their roots back to the Ruidus/Ludinus/solstice story in some way. The closest example of interwoven backstories from previous campaigns would be Beau and Veth's connection to Isharnai. It's as if the only way to prevent another apocalypse is to bring these wildly different characters together by an unknown force... Fate.

With all that said, it's perfectly fine to be disappointed with the narrative. Focusing on theme is a departure from past campaigns. I believe most of us were expecting a character driven story, especially from a DnD campaign. Themes have always played an important role in the show of course (that's how story telling works), but it hasn't controlled the pacing quite like this. We saw it at the end of C2 when the cast wanted to end the campaign with an arc about found family and redemption instead of exploring all other character stories. It worked because ultimately that was the story of the Mighty Nein, and we already had a strong connection with the characters.

I think it's also fine to question whether a multi-year TTRPG campaign is the best medium for a theme or plot driven narrative instead of a character driven one. But, if your theme is fate and choice, I think having the story directed by dice rolls and player choice is an interesting way to do it.

There is absolutely nothing wrong with disliking the story or comparing it to past campaigns. You're not a bad fan. But I worry too many folks, 16 months in, are still expecting a story like C1 or C2, and it's only going to lead to further frustration.

#critical role#cr spoilers#c2 spoilers#c3 spoilers#i prefer character driven stories myself#but this is where we are#could tonight's episode change all this#sure#but I wouldn't bet all my money on having multiple arcs after the solstice#i'm 100% fine with being wrong though#cr meta#cr discourse#you expected your favorite baker to make you apple pie#but they made cherry#you dont have to eat it#or you can eat and think one pie is better than the other#but dont expect cherry to turn into apple#edit: this was written before ep51

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

I feel sorry for the poor soul at DW who had to draw over Lotor in this scene. Studio Mir's style is not as easy as it looks, LOL.

Who has the pointier chin?

I’ll let the pics do the talk.

(OK, giving u some hints- no 1: in VLD there are different degrees of pointiness for each visage. There's a certain angle to their V-shaped chins, and it varies from one character to another - Allura, Pidge, Lance, Lotor, Keith etc.)

(Hint no 2: Compare the pink and the blue outlines)

In conclusion...

If anything, mommy here probably says "You deserved better".

#lotor deserved better#lotor#allura#voltron#lotura meta#vld meta#vld gifs#forget about the messed-up perspective#that's the cherry on the pie#thanks Bob now I know how to make Gifs in Photoshop#All portraits are screencaps from VLD#whoever drew over Lotor was either tired / sloppy / or did it on purpose#LOL I wouldn’t be surprised if it was on purpose#the frustration omg I can only imagine to have to butcher an amazing story#the writers were done so wrong#the truth will eventually come out#jesseblue writes

53 notes

·

View notes