#little women analysis

Text

The Color Concept on Little Women (2022)

Part 2: Earthenspoon and Nospoon

Earthenspoon and Nospoon is refer to Injoo and Hwayoung's conversation (in Korean dialogue; in Eng sub it was changed) at 1st ep

Injoo call her social status as "Earthenspoon"

Hwayoung call herself as "No Spoon"

This Earthenspoon and Nospoon conversation even become the title of one of Little Women OST

youtube

At South Korea, there's "spoon" term to differentiate each socioeconomic classes (highest class is diamond spoon; lowest class is dirt/earthen spoon)

Those social status were shown in series through color pallete of clothes

***

Earthenspoon = Earth Colors: Injoo's main color pallete

Of course it will be hard if i am collecting all Injoo's clothes from 12 episodes, so i will give some sample only from some episodes lol

As you can see, most color of Injoo's clothes (mostly at her home country South Korea) are Earth colors:

Various shades of Brown (and little bit greenish)

Those earth colors symbolising Injoo's social status: the earthen/dirt spoon

In some special occassion, mostly if relate to Hwayoung, Injoo wears Green color more dominant:

When Injoo investigate Hwayoung's apartment

When Injoo went to auction at Singapore (and in hope could met Hwayoung)

When Injoo save Hwayoung from Sangah

The Green color probably refer to unbloomed color of Princess of Thieves: which is dominated with green color

Green also color of Robinhood, the most known legendary thief

Meanwhile at Singapore (on climax scene) and when Injoo "playing" rich, Injoo's color pallete changed from earth color into pink; which is part of color of the bloomed Princess of Thieves

It's like symbolising how the earthenspoon and unbloomed Injoo is bloomed into pink part of Princess of Thieves

***

Nospoon = Colorless: Hwayoung's main color pallete

Hwayoung's color pallete (mostly when she's at South Korea) is colorless/no color, such as: Black, White, Grey

It's symbolized how Hwayoung is not belong to everything; she is excluded from any social class (no spoon)

The color also symbolized how Hwayoung is neither good or bad (no color/colorless)

At Singapore, Hwayoung's dress color is Purple, the part of color of Princess of Thieves. On 1st episode, there's a little glimpse of purple color on Hwayoung's clothes, like indicated she's secret part of Princess of Thieves

One of Hwayoung's name meaning is Shadow of Flower. The colorless pallete probably also refer to how Hwayoung is the shadow part of the flowers:

Princess of Thieves: to Injoo

Blue Ghost Orchid: to Sangah

(See more explaination in Part 1: Princess of Thieves)

***

The Color Swapped Between Earthenspoon and Nospoon

Interestingly, there's color pallete swap between Earthenspoon's Injoo and Nospoon's Hwayoung, during great aunt's house scene

Hwayoung's color pallete become earth color (earthenspoon), while Injoo is black (nospoon)

If try to look back at some scenes on previous episodes, actually it's not first time their color pallete were swapped, and it happen on certain scenes:

Injoo's earthenspoon color pallete become nospoon color pallete, when she's with her sisters, with Hwayoung, or when she's alone

Hwayoung's nospoon color pallete changed into earthenspoon, when she's talk to public and when she's opening up to Injoo

Injoo daily life color is earth, but when she want to act though, Injoo become colorless

Hwayoung daily life color mostly colorless, but when she opened herself, Hwayoung become earth color

***

The Earthenspoon and Nospoon on Shoes Exchange

The color swapped meaning also visible on the shoes that Hwayoung and Injoo exchanged on Singapore climax scene on ep 8

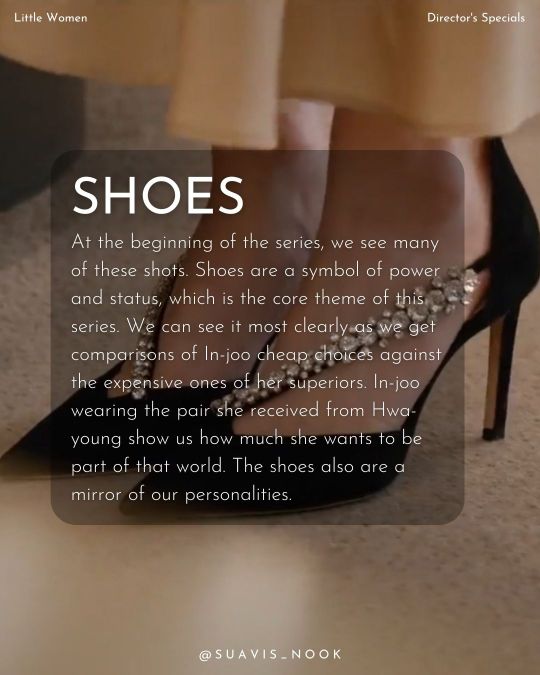

On this series, shoes have meanings:

Heels = rich life, but there's danger and risk

Sneakers = simple, but comfortable life

(See more explaination on Shoes Exchange lore)

But the sneakers, that symbolized comfortable and simple life (injoo's earthenspoon), have no spoon color: black, instead of earthenspoon color

Meanwhile the heels, that symbolized rich but there's risk (hwayoung's nospoon), have earthenspoon color: earth, instead of no spoon color

It's like symbolising on how Injoo's earthenspoon and Hwayoung's nospoon, how their fate got swapped, through their ritual of shoes exchange

#little women#tvn little women#little women 2022#little women korea#kim go eun#choo ja hyun#jin hwa young#oh in joo#youngjoo#choo jahyun#kim goeun#ggonekim#작은아씨들#추자현#김고은#sapphic ships#화영인주#진화영#오인주#little women analysis#little women theory#hwayoung x injoo#tvn drama#kdrama#netflix series

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Do you ever think about how sad and messed up it is to grow up in this world as a little girl who likes to read. Because you are a child, and you don't get that there's a difference in who writes the books, you read everything you like, you read the adventures and the fantasy and the mysteries and the traumatic stuff and if you're also very isolated and lonely, these books build your worldview. Because why wouldn't they? They're written by humans, so they have the attitudes, opinions, perceptions, morals and spirits of human beings in them, they're telling you what humans think and feel about things, how they go about situations, what they imagine, what they desire. What your role in all this is, or what it could potentially be.

But, since you are not capable of differentiating the material, and you just read what is available to you, you end up reading a lot of books written by m*n. You also have to go thru the required reading at school - 90% written by m*n. And so slowly, since young age, without even socializing or learning it thru interaction, you find yourself in a world shaped by minds who do not have empathy for women, especially not for little girls. You find yourself relating to the male protagonists, but you also find out that girls only play a passive role in their stories. You find that m*n problems are centered, made important, their suffering and violence critical points in the story, while women are cast aside as helpers, servants, givers, caretakers, and generally just exist in the background, not a thought given to what they are going thru.

You learn thru books written by m*n, that your experience is secondary. Even if you cast yourself as the adventuring, immensely important and struggling protagonist, even then the other women in your mind end up being just background characters, caregivers who do not need a thought spared for their suffering.

Books written by m*n, even for children, will trivialize female suffering to the point where they shape the child's mind into one that looks at the world from a male perspective. Where women either don't matter, or are capable only of giving and aiding, to be cast aside for more important matters, such as male aspirations for their own lives.

Thinking back, I understand why I felt myself unimportant and trivial in any social setting - I understood my role from the written word, and I knew adults found me trivial, secondary, only a background figure to someone else's adventure or mission. As much as I could fight it in my fantasies, and make myself the main character, it felt like a pipe dream, like something that was incredible self-indulged and selfish and would never translate to reality.

I wish it had been different. I wish I had been introduced specifically and only to books written by women, for women. I wish I had found empathy for myself in those books. I wish I had found myself standing on high ground, equal ground, with other women, our desires centered, our lives translated into tales of epic importance - because that's what they are. I wish I had been born into a world where female perspective is available from the start, not after years of growing up and finding feminist literature and having to re-write my own role in my brain, from all of those years of reading male perspective as the default.

I don't think any little girl should be exposed to literature that shape her world as a place where she doesn't matter. I don't think books written by males and shaped by their worldview should be allowed into children's literature, or teenage or for young adults. Girls should not be learning from fiction that their most important value is empathy and understanding for male problems, and their second, to be desired and/or helpful to them, all while being treated as nothing but service and background noise until you're desired for something. We need to open books and find out that we matter too. That our lives can be the center of our existence, rather than being in the service of someone else's life.

#reading as a little girl#analysis of male written literature#radical feminism#feminism#worldview shaped by books#radfem#radblr#thinking of all of the books i absorbed in my childhood where women didn't matter :(#and how messed up thoughts i ended up having of trying to be helpful and useful in order to have value#but i would never have value#because i was a girl in a misognystic world#and the books were informing me of that#and all i wanted was a bit of escape from reality#fiction written by men is garbage :(

668 notes

·

View notes

Text

One day if I'm really bored I'll figure out what percent of pages in the 3 existing Locked Tomb novels have Gideon and Harrow physically in the same room and talking to each other. I bet it's like 20%

#'oh so you're doing that thing where you desperately ship two characters who only share a small amount of screentime?'#NO it's DIFFERENT they're DIFFERENT i swear this is NOT THAT#'if they haven't even talked for two whole books -'#they're fucked-up little soulmates ok this is NOT like shipping two background women on a show with all men main characters. I SWEAR#the locked tomb#nonasbirthday#maybe someone has already done this analysis. link me if you've got it lmao

60 notes

·

View notes

Note

How many posts do you have on dotc? also, i havent seen it before if you have, but you talked about the huge battle where starclan spontaneously pops into existence in order to tell everyone to stop fighting

TONS. It's the most frequent canon material I post about here. It's usually tagged #Warrior Cats Analysis.

I am also doing a live re-read and have been for a couple months. It started on this blog as #Bonefall Reads DOTC, and continued over on my other blog @bonebabbles as #Bones Reads DOTC, so that I was spamming my followers less.

I usually tag my harshest posts with #DOTC Hate out of respect to the main tag.

#Yes i have talked about the Firbst Babble before#I want to break it down into a serious analysis because it was during my read#And I was mostly just screaming. I want to articulate my thoughts on it#Because every character is so *fucking stupid* during that exchange it's oscar-worthy#Gray has the KING of worthless ideas to attempt Appeasement 4: It Will Totally Work This Time#And it turns out the big ass plan that he came up with. The closer. The silver bullet...#Is blinking puppydog eyes at the sadistic tyrant and going ''do you remember how we used to run''#But also youre unfortunately a little wrong about how the fight ends.#Clear ends it because killing women and children is fine but not his bootlicking brother. HIM he'll just emotionally abuse.#You see this is because hes misunderstood and was good all along but just very scared of not having jesus.#Or something.#Dotc hate

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some “Little Women” thoughts – In defense of Meg’s marriage

@littlewomenpodcast, @thatscarletflycatcher, @joandfriedrich

Whether Little Women is a feminist book or an anti-feminist book will probably be debated forever.

Most of the debate seems to center around the character of Jo: whether she’s depressingly “tamed” in the end or matures in a healthy way, whether her marriage is anti-feminist or not, and whether or not it’s “anti-feminist” that in the end she’s a schoolmistress instead of a famous author. (Though of course she’ll eventually be a famous author in Jo’s Boys.) But similar debate surrounds the other March sisters too, for various reasons.

Not even Meg, the sister whom readers most often seem to overlook, is spared from these debates. Many feminist critics, such as (but not limited to) Samantha Ellis in her book How to Be a Heroine, have criticized the chapters depicting Meg and John Brooke’s married life in Part II. They label those chapters “depressing,” and they feel as if Meg and John are constantly at odds with each other and miserable. They argue that each of their marital conflicts ends with Meg learning to be a more submissive wife who placates and effaces herself for her husband. And they despise John, labeling him “selfish” and “disrespectful.”

Sometimes I wonder if I read the same book that they did.

It seems obvious to me that Meg and John’s marriage is a happy and healthy one: Alcott is just honest about the fact that even the happiest marriage includes conflict and requires work. Some of these critics seem to think fictional marriages only exist in two forms, “perfect” and “toxic,” with no in-betweens. Nor does John deserve half the negative commentary he gets, nor does Meg’s personal growth within her marriage consist of learning to be a submissive or self-effacing wife. On the contrary, much of her growth consists of her learning that she doesn’t need to be a “perfect” housewife and mother who gives and demands too much of herself, and their marriage becomes more of an equal partnership by the end, not less of one.

Let’s look in depth all three of Meg and John’s marital conflicts.

First there’s the jelly incident.

Here we see the first of a recurring theme: Meg is determined to be the perfect housewife and is "over-anxious to please.” She wants to do everything right and do it all by herself, because she’s afraid that otherwise, she'll be a failure. In terms of her personality type, I agree with @funkymbtifiction that Meg is an ESFJ. In the book, if not in all adaptations, Meg and Amy are both ESFJs: Amy is more of the sparkling “Glinda in Wicked” variety, while Meg, apart from her streak of vanity, is more of the down-to-earth, motherly, “Mrs. Potts in Beauty and the Beast” variety. But Meg in particular shows what @alittlebitofpersonality calls the ESFJ Type Angst. Her eagerness to manage her marriage and motherhood in the most pleasant, correct way (her strong Fe and Si) and her fear of possible failure (her weak Ne and Ti) give her, in A Little Bit of Personality’s words, a “frantic desire to do everything and get it done right now,” so she drives herself too hard.

She shouldn’t have promised John that he could bring home a dinner guest at any time; that’s unrealistic. Nor should she have tried to make jelly for the first time in her life using only the memory of watching Hannah make it; she should have invited Hannah over to help her. Nor should she have become so absorbed in making and re-making the jelly that she didn’t cook dinner; nor should she have let herself be so distraught about the failed jelly, or lost her temper with John and then run to her room, leaving him to improvise a bread-and-cheese dinner and entertain Mr. Scott alone.

John is also at fault and acknowledges it. He shouldn’t have forgotten that Meg was making jelly that day and brought home a guest without warning. He shouldn’t have laughed at Meg’s anguish over the failed jelly, nor should he have joked that he and Mr. Scott “won’t ask for jelly” with dinner. But let’s be fair to John. His laughter is probably just as much out of relief as out of amusement, because when he first comes home and finds Meg sobbing, he worries that something terrible has happened. Then, when he realizes no food has been cooked, he’s understandably annoyed because he’s come home from work tired and hungry, with a guest too, and Meg hasn’t done what she promised she would. But he doesn’t lose his temper; he stays calm and amiable and accepts a cold-cut meal; he just gives his annoyance a tiny vent with his joking barb about the jelly. Then Meg overreacts in response.

In the hours afterwards, he and Meg are still polite to each other, just a bit distant, each sorry but waiting for the other to apologize first. Then, when Meg finally breaks the ice, they both apologize (not just Meg – in fact only John verbally apologizes, Meg just does it with a kiss), everything is fine again, and from then on they both laugh about the incident.

Maybe by modern standards, it is problematic that Marmee has urged Meg to be careful not to make John angry and to always apologize first when they’re both at fault. But it’s not because John has “a volcanic temper,” as Samantha Ellis inexplicably claimed– he so clearly doesn’t! Nor is Marmee’s message “Men are less forgiving than women so we need to placate them.” She’s not talking about “men,” but about John the individual, and she’s not urging Meg to placate him either. All she means is that John’s anger doesn’t flare up and die quickly like the March women’s, but simmers much longer because he represses it.

Then there’s the silk incident.

Say what you will about vanity-shaming and other gendered implications (which of course are valid), but Meg didn’t need an expensive silk dress, and she shouldn’t have ordered it without telling John. It’s not that a wife should ask her husband’s permission to spend money; it’s that no one, regardless of gender, should do anything behind their spouse’s back that they’re ashamed to admit. And again, John doesn’t get angry. He accepts the expense without complaining. He’s just hurt; he works so hard to provide for Meg, and the fact that what he provides isn’t good enough for her, that she says “I’m tired of being poor,” makes him feel inadequate. Yet he tries not to show his hurt and is willing to let Meg have the dress. He cancels his own order for a new overcoat so they can afford it; he’s willing to sacrifice something he needs for something Meg wants but doesn’t need. When Meg sells the silk and buys the overcoat for John instead, she’s only repaying his selflessness in kind.

Finally, we reach the chapter “On the Shelf.”

I’ve read several feminist articles that criticize this chapter and especially John’s behavior in it. But I don’t agree with any of them. John isn’t being selfish the way Meg briefly thinks he is; he’s not jealous of her attention to the twins. By all appearances, Meg genuinely neglects him and overwhelms herself too, because she devotes every waking moment to her two toddlers and thinks no one can properly take care of them but herself. Again she’s trying to be superhuman because she’s afraid of failure. She doesn’t let John be a parent to his own children, or take any time to relax either, and she spoils the twins and makes things harder for herself by giving in to their tantrums. I understand why some feminists are rankled when John starts spending his evenings elsewhere, Meg feels ignored, and Marmee tells her it’s her own fault for forgetting ‘her duty to her husband.” But even if that wording isn’t ideal by modern standards, it's arguably true. To blame John for “not bothering” to help take care of the twins and “forcing” Meg to do it all alone, as some of these critics do, is just the opposite of what the chapter means to convey.

And again, John doesn’t get angry or complain. Nor, unlike what some of these critics seem to think, does he cheat on Meg, either physically or emotionally. He just goes to visit the Scotts rather than feel lonely and useless at home (where Samantha Ellis got the idea that he goes to “what sounds like a dodgy establishment” is beyond me; it’s a friend’s house), and just because Meg worries that his eye is roving to pretty Mrs. Scott doesn’t mean it is.

Arguably, this chapter has a very feminist message about egalitarian marriage and co-parenting. Instead of doing all the work alone and sacrificing her own wellbeing, Meg learns to share her parenting duties with John, and to let Hannah babysit often so they can have much-needed time to themselves too. She also starts to converse with John about politics, so he doesn’t constantly feel the need to seek out a male friend to discuss them, and he returns the favor by conversing with her about domestic subjects too. Traditional gender divides are relaxed. By the end of the chapter, their marriage is more balanced and equal than ever.

I’ve also read complaints about John’s co-parenting. The fact that Meg is portrayed as too soft-hearted, spoiling rowdy Demi and needing John to discipline him. The fact that John and therefore Alcott advocates the potentially traumatic “cry it out” method of sleep training. The fact that John insists on handling Demi’s tantrum in his own way despite Meg’s objections and Meg reluctantly gives in, with references to John’s “masterful tone” and Meg’s “docility.” The possible sexist implication that John knows how to parent better than Meg does.

But I don’t think Alcott meant to imply that John is a better parent than Meg or meant us to see him as lording over her. Even though he won’t let her give in to Demi’s demands, what finally stops Demi’s tantrum is a kiss from Meg after he’s been allowed to cry for a few minutes. They solve the problem together by combining John’s discipline with Meg’s tenderness. Then John shows tenderness of his own by lying down on the bed and holding Demi as he falls asleep, so it’s not a straightforward “cry it out” that he (or Alcott) advocates for sleep training, but something closer to the Ferber Method.

Of course there is an old-fashioned, traditional aura to Meg and John’s marriage and to their roles in the house: Meg as homemaker and John as breadwinner, Meg as nurturer and John as disciplinarian to the twins, and her fondness for sitting in his lap. But of the four March sisters, Meg was always the most traditional young woman of her era. Her marriage dynamic might not be what Jo or even Amy would want, but it’s just right for Meg. And Alcott shows us that with the right effort, even a basically traditional marriage can be egalitarian and mutually healthy.

The one feminist complaint I might sympathize with is that all three of these episodes do revolve around Meg learning to be a better wife. In each instance, Meg is portrayed as being more at fault than John, and she’s the one who learns the chief lesson. But I don’t consider this a sexist choice either. The March sisters are the protagonists of Little Women. Their coming-of-age journeys and personal growth are the focal point. John is a supporting character, so it’s arguably only natural that the “married life” chapters focus more on Meg’s personal growth than on his.

These are the reasons why I personally enjoy the chapters revolving around Meg and John’s marriage, and why I don’t consider them problematic or “depressing.” They’re just a realistic portrayal of the struggles, mistakes, and conflicts that occasionally rise within a happy marriage, which are resolved in a healthy way when both partners put in the necessary work. I understand where the critics who dislike those chapters are coming from, but I can’t bring myself to agree.

#little women#louisa may alcott#meta#analysis#meg march#john brooke#marriage#parenting#feminism#rambling

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

i think there’s something in tuor being the effectively the opposite of húrin. favored by a god vs. hated and condemned by a god…divinely called to action vs. divinely removed from it…fathered a notably fair-haired child of prophecy vs. a notably dark-haired child under a curse…escaped over the sea and out of history in an act of hope vs. consumed by the sea and by history in an act of despair..

#united in their love for tough-cookie wise women from doomed peoples#húrin#tuor#the silmarillion#the children of húrin#every day i wake up + get on my little soapbox#brought to you by me#meta + analysis#the professor's world#tcoh#edain

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

Little Women - director's specials 🎬

~directed by Kim Hee Won

#little women#little women 2022#little women kdrama#littlewomenedit#kdrama#kdramaedit#cinematography#film analysis#kim hee won#movie blog#kim go eun#wi ha joon#nam ji hyun#park ji hu#uhm ji won

428 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think everyone should be required to have at least one improvisational rp experience before they can have an opinion on qsmp characters actually.

#especially when it’s about the women on the server#improv is HARD yall#nevermind when it’s in your non native language#you can’t approach character analysis in improv the same way you can in scripted media#anyways this was sparked by Baghera saying she felt insecure about her rp you’re doing great queen#qsmp#discourse#qsmp discourse#baghera jones#little rant over im just annoyed especially by Twitter

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

jo march blossomed into a world where the end all for women is romantic love. a world where romance is prized and valued over friendships, sometimes even familial bonds, leaving those who do not dwell on such subjects to feel isolated. loneliness for jo is not the lack of a romantic partner. it is the cold tones of an empty attic that is haunted by the memory of one filled with the golden light of laughter from best friends and sisters. Not much has changed from past to now with the idea that love is all a woman is fit for.

it's seen as taboo for a strong coded female character to admit to wanting to be loved. years of cultural messaging made many women associate independence or female autonomy with being stoic, being emotionless, the weapon-wielding, frequently assumed heterosexual heroine should be alone or else she is risking exhibiting subordination or dependence. as if her coexistence with a man automatically diminishes her to a secondary character. the emotional burden of romance, in most mainstream media, is often carried by the female character. even in the arc of the male hero, his love interest is written solely to fulfill a function as a stepping stone to self-actualization or a precursor is his "man pain."

jo march is terrified of change. she finds no comfort in the future. jo would prefer to stay young and play in the attic till the children’s last breaths because what was can feel better than what is. however, change is forever linked to the wheel of time. suddenly, all this change came in rapidly in her life, as it does for all people when nearing the endings of childhood. everything is happening so quickly, and it can not be undone.

jo has a desperate desire- need to be alone, however not to be lonely. she is a woman fueled by passion, a passion that has consumed her entire being into a state of delusion. delusion in the sense that she lives in hopes that her and loved ones will stay youthful to play with her. jo's passion is bound by the inevitable, time. the little world that she had created with her sisters had shattered from the "curse" of aging. therefore, she actively tries to keep that same spark in her writing. her fantasy is better than the burden of reality. jo march is grieving the loss of innocence and childhood. as everyone else is going along with their individual lives, jo has either consciously or subconsciously chosen to never emotionally grow up.

(all based of the 2019 version)

#jo march#little women#little woman 2019#little woman movie#amy march#amy x laurie#laurie laurence#beth march#strong women#women#aromantic#strong female#strong female characters#character analysis

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

After finishing She-Ra 2018 I'm trying to work on my unified theory for why CatDora bothers me as the endgame ship. Cause as CEO of mentally ill cartoon women, there's something about it that feels a disservice to Catra's psychology and trauma. She is genuinely such an interesting character to watch because they so clearly lay out the abusive dynamic that informs her entire character, but by the kiss, I feel like they lost steam with it.

The biggest thing to me is the simple fact that Adora is basically a trigger for her. Adora's personality as someone who is constantly self-sacrificing and forgiving is something Catra has a deep hatred for because she believes she is worthless and unforgivable, and when people try to help her she feels they're using her to look better while she fails to get better.

The fact that ADORA herself was the one in that original dynamic that traumatized the hell out of her makes me uncomfortable with how Catra eventually just... stops getting set off by things. I just can't imagine how what happened leading up to their kiss would desensitize Catra enough to that trauma response that she'd be in love with her. Like in that same season she was fucking death gripping the table at hearing Adora's name, and in seasons earlier she straight up like dissociated when people brought up her heroics. Not only the unearned healing, but the "I've loved you all along" feels a bit patronizing to her past. That all her emotionality was complicated romantic feelings, and not... having really nasty childhood trauma.

#shut the heck up#she ra#that damn cat#show was good btw#not a masterpiece - it was kinda corny in a bad way sometimes - but was fun#it felt like it wanted to be there and had ideas it was interested in#and i really like catra she is my fave as you can see#mentally ill cartoon women#im actually still getting my little pea brain around it cause her trauma and dynamic with adora is a lot#i like that the show was patient with her i wish it wasnt patient just cause it wanted her to kiss adora#imo she should be with someone else who is willing to stick up for her as adora does but isnt her#isnt the woman who's name and face can send her into self-destructive hysterics#something that is bad and needs ro change but she needs more time for than was given#wheres she-ra future where we recontextualize the casts trauma and show happy endings still need more time?#tag talking#media analysis

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

The chapter in the book Little Women/Good Wives, and the scene in the movies of Jo's proposal and married life are So Important. They show the heroine living a happy and unconventional lifestyle: It says that this life she leads with work, marriage, and very little money is a good, wholesome life. That is so important.

But - I think an overlooked chapter in the books (not depicted in the films that I have seen) is the one in which Meg tries to cook and preserve currant jam. She has a miserable day, turned even worse when her husband John brings home a friend for dinner. For once, Meg snaps at him and he snaps back when provoked.

Eventually, Meg takes some good advhice from Marmee, and she brings peace. The chapter ends with a line about married life foe these two not being perfect - it will always have its difficulties, but peace has been preserved and quarrels will be managed.

In another chapter, after Meg has had twins, she understandable becomes so wrapped up in them that she neglects both herself and her husband. Neither the book nor I are saying that one partner should be a servant to the other. But in marriage, we have promised something of ourselves to them*. Meg has isolated herself from the world and grown irritable while she rarely sees John who spends time at his friend's house instead of being nagged at home.

Again, Meg takes initiative and fixes it. This is a bit of a pattern that we see the world over today, in which women usually take the emotional burden in the home. I have no comment to make on that, it's not the point of this post.

The point is: The book has made a few excellent points through everyday, domestic scenes about marriage which are not (or only rarely) shown on film. The glamour, unpredictability and excitement of Jo's publishing, marriage to the Professor, work and, from a plot-based POV, the fact that she is the main character, mean that her storyline is in the spotlight. I love her storyline. But I also think that Meg's has something important to teach us: If you choose the more traditional path, your life is just as full of adventure and growth, difficulties, pain and pleasures.

*talking about non-toxic nd non-abusive relationships.

#meg marg#little women#meg brooke#john brooke#marmee#book little women#book analysis#book to film#film adaptation#louise may alcott#bookaholic#stories#book

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Nancy Wheeler woman lover agenda has been here since the beginning. Or at least, Nancy, even at that point, was so displeased with the idea of marriage and settling down with a Man and having kids. And oh my good golly gee, do I have quite the solution for your Ms. Wheeler! Woman! Robin Buckley! Not a man! No kids! Operation Croissant?! Go travel with Robin to Paris ! (From Rebel Robin) You can’t even legally get married to her until your in your 50’s so you’d have a solid reason not to! (However I do believe she just doesn’t like the idea of marriage as she has seen with her parents)

#ronance#nancy wheeler#st nancy#robin buckley#nancy stranger things#robin stranger things#st#st1#st analysis#st parallels#cinematic parallels#little women#stranger things 4#stranger things season 4#stranger things#st4#lgbtqia#lesbian Nancy wheeler#bisexual nancy wheeler#nancy wheeler headcanons#girl kisser Nancy wheeler#Natalia dyer#Maya hawke#robin and nancy#nancy and robin#robin x nancy#nancy x robin#robin/nancy#nancy/robin#robin buckley x nancy wheeler

382 notes

·

View notes

Text

sometimes i write kotoko to cope with my perpetual anger at the world/system i live under which is rly funny in concept every time i think about it. girl who was like 5 inches away from realising the problems with the justice system was the entire rest of the system as a whole and then immediately was thrown headfirst into an innocent verdict that completely fucked her up even worse. girl whose beliefs clash against each others so harshly (black and white view of "good" and "evil", the "weak" and the "strong") vs

like. god "we" really did that to her huh. she really did believe that it was possible some of the prisoners were wrongly accused. she saw how bad the justice system is. and then "we" spun it around in a complete 180 because "we" failed to look deeper at her and affirmed the worst parts of her instead.

her beliefs were not "its fine to do whatever to people who have done something wrong"!!! that was not her fucking beliefs!! IN FACT SHE SEEMED TO ACTIVELY BE A BIT AGAINST THAT IDEAL IN TASK. "WE" DID THAT. THOSE WERE THE "BELIEFS" OF THOSE WHO VOTED HER INNOCENT IN T1 WITHOUT LOOKING DEEPER AT HER. "WE" TAUGHT HER THAT HUH...DONT WORRY GIRL ILL REMEMBER YOUR BELIEFS I PROMISE. ILL WRITE UR ANGER/FRUSTRATION AT THE GENUINE "UNFAIRNESS" OF THE WORLD VS HOW YOU STILL HOLD SUCH BLACK AND WHITE OR "CHILDISH" VIEWS. FOREVER. ITS IMPORTANT 2 ME.

#i also think about how her focus on crime was always on those that endangered women or children. like huh. what a very specific niche!#did something happen kotoko? to inspire you to focus on that specifically? strange!#little guy posting#im just saying thoughts here. none of them that coherent or rly put together. but i just AAUUUUGGGHHH#perhaps a bit inspired by my frustration at people who claim shes a fascist. maybe. moment of weakness.#'nd also just my frustration at the world as stated previous. kotoko i love u i wish i could put my thoughts about u in more-#-coherent analysis posts that talk about your nuance in beliefs

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

More "Little Women" thoughts: Beth March and ableism (warning: very long)

@littlewomenchannel, @thatscarletflycatcher, @joandfriedrich

A few days ago, I was looking for articles about ableism in 19th century literature (because some of us casually do that sort of thing) when I came across this review of Little Women. It's a sad review: the author writes that Little Women was her favorite childhood book, but now, as an adult, she can't enjoy it anymore, because she's come to recognize the "ableism" of the portrayal of Beth's illness and death. As a chronically ill person herself, she used to enjoy identifying with Beth and looked to her as a role model. But now she realizes that this probably fed her own internalized ableism and taught her to suppress her feelings about her illness, because of the way Beth is admired for never complaining while she's sick. She also objects to the fact that Beth (a) has no ambitions or dreams for the future, as if sick people "aren't allowed" to have them, (b) is portrayed as "too good and pure for this earth," and (c) is used as "inspiration porn" to teach Jo and the other sisters to be better people.

I've written in the past about how much I dislike most of the commentary I've read about Beth's character. Without a doubt, critics tend to view her in ableist ways. But only in the past year, with this review as the culmination, have I considered that maybe her portrayal in the book itself is ableist. While I'm not chronically ill, I relate to Beth for different reasons, and I wish I could argue that her portrayal isn't ableist at all: not only for my own sake, but so the above reviewer could enjoy her former favorite book again. But that's impossible to argue. Still, I'd like to take some time to look at Beth's portrayal, through the lens of disability, illness, and premature death in fiction, and the complexities of how it handles those issues.

There's no denying that the book uses Beth's illnesses as a device to inspire growth in the other characters. In Part I, her scarlet fever is written chiefly as an ordeal for Meg, Jo, and Amy, which serves their coming-of-age journeys, and in Part II, her final illness and death once again serve the others' development. Namely by teaching Jo to be kinder and more patient, by reviving Jo's writing career as she works through her grief by turning back to her pen, and by finally bringing Amy and Laurie together as a couple. Of course using a sick or disabled character's suffering and death mainly to serve the healthy, able-bodied characters' personal growth is an ableist tradition, just like the "women in the refrigerator" trope (sacrificing female characters for male characters' development) is sexist.

There's also the fact that Beth is admired, both by Jo and by Louisa May Alcott's narrator voice, for being patient and uncomplaining throughout most of her sickness (though not through all of it– more on that below), rarely even asking for help or care, and "trying not to be a trouble" even as she nears death. Of course we should question the old tradition of glorifying people, especially women and girls, who efface themselves for others and who never complain no matter how much they suffer. Whether their suffering is illness, abuse, poverty, or anything else, the old-fashioned model of "bearing it cheerfully" should definitely be questioned. A chronically ill person should be allowed to fully express their pain and anger. And Beth's real-life model, Louisa May Alcott's sister Elizabeth "Lizzie" Alcott, was angry about her fatal illness – allegedly she became prone to uncontrollable rages in her painful last year of life, which her sister left out of Beth's decline to give her a more socially acceptable "good Christian death." The pressure to never complain, to "try not to be a trouble," and to be a role model of bravery for friends and family is a burden that no sick or disabled person needs! Yet as the above book review made clear, Beth's portrayal can potentially put that pressure on a sick or disabled reader. Just because it was common and accepted in the 19th century to portray illness and death this way doesn't make it any less ableist than it would be from a modern author.

Yet Beth's storyline is more than just a string of ableist 19th century illness tropes. To view it that way requires ignoring its context, both in Alcott's personal life and in the literature of her era.

First of all, there's the fact that Beth is based on a real person, Alcott's beloved sister. She's an idealized portrait, but she's still based in truth. Alcott didn't create a sickly fictional character just to kill off for the sake of the other characters' growth; Beth becomes chronically ill because Lizzie became chronically ill, and she dies because Lizzie died. By idealizing her as Beth and by portraying her life and death as inspiring her family and friends to become better people, Alcott meant to pay tribute to her sister – and maybe it also filled a need within her to find some meaning in her sister's suffering and in such a terrible, unfair loss. Of course just because Alcott loved her sister doesn't mean she couldn't have been ableist toward her, and just because she meant Beth's portrayal as a tribute doesn't mean it can't include problematic tropes. But the context is important to remember.

Besides, while Beth might seem like a figure of old-fashioned, syrupy sentimentality by modern writing standards, I would argue that compared to similar sweet, doomed female characters in other books of the same era, her portrayal is fairly progressive.

19th century fiction is full of angelic young girls, either children or teenage maidens, who, after short lives of gentle, selfless piety, waste patiently away from a drawn-out illness, and then die a "good Christian death," leaving their loved ones to become better people by their example. Two others I know besides Beth, and whom Alcott knew too, are Helen Burns in Jane Eyre and Evangeline "Little Eva" St. Clare in Uncle Tom's Cabin. (Anyone who calls Beth's death "the most maudlin death in 19th century literature" hasn't read Eva's!) Another famous example would probably be Charles Dickens' Little Nell from The Old Curiosity Shop, but I haven't read that book yet. Fairly often these characters seem to have been written as tributes to young girls in the authors' own families who had died: for example, Charlotte Brontë based Helen Burns on her sister Maria, while Dickens based Little Nell on his teenage sister-in-law Mary Hogarth. In some ways Beth is a classic example of this trope: that I'll grant. But I would argue that she's a complex example. I sincerely think Alcott set out to portray her as less of a romanticized paragon who exists to inspire others and more of a real human being than earlier authors' doomed angel-girls.

Beth is framed as a co-protagonist with her three sisters, not as a supporting character like Helen Burns or Eva St. Clare. This gets lost in the adaptations that focus more exclusively on Jo, but the book is called Little Women and not Jo for a reason. In Part I, despite idealizing her more than the other sisters and sometimes holding her up as their role model, Alcott still makes a point to say that Beth was "not an angel but a very human little girl." Just like her sisters, she dislikes tedious chores. She can be irresponsible, namely when her pet bird dies after she forgets to feed him for days. She can be moody, though it tends to manifest as tears or headaches instead of the angry snapping her sisters indulge in. And she has one big "burden" that she actively struggles with: her overwhelming shyness. She isn't a static character who inspires growth in others without needing to grow herself. Even though her flaws are minor, the idea that Alcott meant her to be a symbol of perfect goodness, too pure for this earth, doesn't ring true.

Her illnesses are also portrayed with a degree of harsh realism that sets her apart from the saintly dying girls in other books. The tuberculosis that kills both Helen Burns and Eva St. Clare is just a slow, gentle weakening with occasional coughs. But Beth's scarlet fever is frightening, both for her sisters and for herself, and her final illness, although vaguely described, is emphatically painful. Her body becomes a "prison-house of pain," as Jo writes, and her formerly calm, uncomplaining demeanor crumbles in a "rebellious" period of physical and emotional torment, horrible for her family to watch. This was clearly the phase when in real life, Lizzie Alcott became prone to fits of rage and dependent on drugs to manage both her pain and her moods; even though Little Women cuts those uglier details, we still feel the tumult, which isn't negated by the fact that it eventually passes and Beth's last days are peaceful.

More importantly, even though Alcott admires Beth for rarely complaining, she still allows her to be miserable about her condition, and the journey of coming to terms with it is Beth's own journey, not just her family's. Helen Burns and Eva St. Clare both serenely embrace death and look forward to heaven. But Beth? She's distraught to have her happy life cut short. True, she tries to resign herself and hide her sadness from her family, but it's clear that she's deeply depressed, and in two different scenes she breaks down crying in Jo's arms (first in bed, before she admits the reason why, and later at the beach after her reveal that she knows she's doomed). Only gradually, over the course of a year and after the above-mentioned period of anguished "rebellion," does she find inner peace, partly thanks to her religious faith, but thanks even more to the loving care and support her family gives her. She's not just a brave role model who makes peace with her fate all alone.

Now, about her lack of dreams and ambitions... This is entirely personal, but never once have I viewed this aspect of Beth's character as Louisa May Alcott "not allowing her" to dream and aspire the way her sisters do. I've always seen it as just a part of her personality, probably taken straight from Lizzie Alcott. Of course I don't know if this is true or not: for all I know, Lizzie did have grand plans for her future which her failing health shattered, and Louisa just chose to give Beth no ambitions to make her a better foil to Jo and/or to make her death less cruel. But why assume that? It's more than possible that even if Lizzie had been healthy and lived long, she really would have been content to stay with her parents until they died, then gone to live with one of her sisters afterward, and chosen to devote her life to taking care of her family.

This is probably a good time to discuss why I relate to Beth. I've written about it before, but it's important, and it explains why I've never viewed her a just a cardboard saint, nor viewed the portrayal of her illness and death as just "inspiration porn."

Even before she becomes chronically ill, Beth is different, and not just by being angelic. "She lived in a happy world of her own," Alcott writes in Part I, "only venturing out to met the few whom she trusted and loved." As late as age fourteen, she still plays with dolls, treats them as if they were alive, and has imaginary friends. She's also been homeschooled, because her social anxiety made the classroom unbearable for her; Alcott describes her shyness as "her infirmity," implying that it's not just a character flaw, but a disability. She never wants to get married, and not only does she have no worldly ambitions, she never even wants to leave her parents' house. Her fondest wish is to "stay at home safe with Father and Mother" forever – a wish that comes true in the saddest possible way, as she dies without ever having left the nest. Yet she's not just a childlike figure, as she has high emotional intelligence from a young age, and she even composes her own music to play on the piano. From a modern perspective, it's easy to read her as neurodivergent, and it seems more than likely that Lizzie Alcott would be diagnosed as neurodivergent if she lived today. As an autistic person, I see so much of myself in Beth... and that includes her lack of ambition. Leave the safety and familiarity of home? Live far from my family, the only people who really understand me? Go out into the big, unknown, anxiety-causing world? Give up my comfortable daily routine to make massive life changes? Not me, unless I have no choice!

This is why, when I first read the book, I found it beautiful that this odd, shy, sickly homebody of a girl, so easy to overlook or dismiss, is ultimately so adored and admired. Even though she doesn't sparkle in society, or defy gender norms, or have grand ambitions, or win any man's romantic love, and even though she dies so young and would probably have never "achieved" much or lived a "normal" life anyway, she's still valuable. Her kindness, her selflessness, and the love she gives to others are enough. Her low self-esteem ("stupid little Beth") and her regret for not doing more with her life are proven wrong, as during her sickness her family and friends reveal just how much she means to them, and even after her death she still makes a positive impact, as her sisters resolve to follow her example of selfless kindness and as she inspires Jo's writing. Of course it's not her job to inspire them, but is it really so problematic that she does?

Still, I've struggled with one possibly ableist aspect of Beth's characterization: the fact that, when she confesses to Jo that she knows she's dying, she suggests that "it was never intended that I should live long." Because she's never had any desire to leave her parents' home and live a "normal" adult life, she reluctantly views her impending death as "for the best." At least it's only Beth herself who says this and not Alcott's narrator voice or any other character; but unfortunately, no one argues against it either. I'd like to think that this speech only voices Beth's low self-esteem (possibly her own internalized albleism), which her family's love, care, and gratitude toward her refute. But the possibility stands that Alcott did rationalize Lizzie's death by thinking she wouldn't have been suited to a long life because she never quite "grew up," and that she expected us to view Beth's death in the same way.

Last spring, I had my first real health crisis since early childhood. For reasons I still don't fully know (probably genetics combined with weight gain and anxiety from two years of living in a pandemic), my blood pressure went dangerously high, and I spent two days in the hospital and still have to take stabilizing pills. In my hospital bed, afraid for my life, I found myself thinking "Maybe I'm like Beth. Maybe I'm not meant to live long. I've never held a full-time job, I can't even drive, socializing is hard, I still depend on my parents and I don't know what I'll do when they're gone, I'm oversensitive, and I feel so much younger than I am. I want to live, but maybe I'm just not suited to this world." Of course that was irrational, fear-based thinking. But it showed me that I have some internalized ableism, and that Beth's view of herself as destined to die young because she's different... doesn't exactly make it better. Just like her self-effacing patience and her role of serving her sisters' character development fed the internalized ableism of the linked review's author. While it hasn't made me dislike Beth or Little Women, it did force me to view her storyline as more of a "problematic fave" than I did before.

At any rate, though, I think the book's portrayal of Beth is much less ableist than most commentary written about her. From critics who insist that she is a symbol of perfect, ethereal goodness that can't survive on earth, to those who wholeheartedly agree that she dies because she's "unable to grow up," to those who view her sisters' admiration for her as inherently anti-feminist, I've read more bad remarks about Beth than I can stand! The worst is when so-called feminist critics conflate Beth's frail health both with her home-centered life and with her gender presentation, and think they're being progressive by saying, for example, "She's killed by her traditional femininity, which makes her too weak to survive," or "She has to die because her life has no meaning outside the home and a modern woman's life needs more meaning than that." Comments like those will always make me angry, but I don't blame Alcott's writing for them. I don't think those were the messages she meant to send.

So what conclusion should I draw from all this? Well, for one thing, I have to admit that Beth's storyline is a "problematic fave" for a disabled or chronically ill reader. I can't claim it's free from ableism and I understand why there's backlash against it. But I won't join fully in the backlash just yet. Alcott's use, and arguable subversion, of ableist tropes in Beth's characterization is complex. I think it's a topic that deserves to be discussed and explored, not used as a reason for readers who relate to Beth to dismiss Little Women altogether.

#little women#beth march#disability representation#chronic illness#ableism#louisa may alcott#elizabeth sewall alcott#fictional characters#characterization#analysis#long#tw: ableism#tw: illness#tw: death

126 notes

·

View notes

Text

The meaning of shoes exchange symbolism on Little Women (2022)

Shoes exchange is important element in series.

Each time someone do shoes exchange, they receive things (from act of love), but they gave away things too (result of bad omen)

The director mentioned giving shoes is act of love.

But there's old supersition that said give shoes means give bad omen.

Both indeed applied here. Let's analyze it

***

Started when Injoo's pink heels got broken. Hwayoung offering her sneakers so Injoo could comfortable walk to hills.

After arrive at hills, Hwayoung offering Injoo her Bruno Zumino, so Injoo could feel confident playing rich at resto.

Kinda back a bit to Injoo's broken pink heels, it's like foreshadow of Red Shoes and bad things around it in future.

These were first hint of symbolisms:

Heels = rich life, but there's danger

Sneakers = simple, but comfortable life

Injoo later give the sneakers back to Hwayoung, symbolizing she gave away comfortable life in exchange to have the Bruno Zumino (rich play & money)

We know what happen next after Injoo receive the heels and give away the sneakers:

Hwayoung give Injoo her luxurious yoga membership + Bruno Zumino heels + 2B Won! And hoping Injoo could live at her dream apartment with her sisters (act of love)

But in exchange, Injoo need to use it all wisely or her life in danger (bad omen)

But we know Injoo, she's reckless (and we love her for that)

When Inhye said she will going to Boston for study, Injoo immediately came to Sangah's house. She's wearing Bruno Zumino and offering the money to Sangah for Inhye's school

At this moment, Injoo's dangerous life is started; Sangah - aka the main villain - found out Injoo has the money and still close with Hwayoung all this time

Yes, seems like Sangah didn't know Hwayoung still close with Injoo all this time

Hwayoung probably realise Sangah tried to "playing" with Injoo if she know Injoo close with her.

That's why Hwayoung tried to make her friendship with Injoo as secret to fooling Sangah and to protect Injoo

But now Sangah know that Injoo still close with Hwayoung - just like what she planned since beginning for her play.

Sangah restarted her discontinued play and continuing her plan to playing Injoo's life.

Meanwhile at Singapore, Hwayoung just realise her plan to make her friendship with Injoo as secret was failed and Sangah tried to play Injoo's life, when she read the manipulated article that Sangah prepare to lure Injoo to Singapore to find her

Hwayoung knew immediately Injoo must be in danger and tried her best to protect her; by throw herself in between car and truck, tell Injoo to run, reporting Injoo's littering, and the most important thing:

Hwayoung took Injoo's heels and exchange it with her sneakers;

It's symbolism of Hwayoung took back all bad omens (heels) that Injoo received and give back the comfort (sneakers) to Injoo

Hwayoung back to Korea after recovered to save Injoo from being punished over her mistake, and receive the punishment

Injoo is now free and situation started back to normal (she wear sneakers in last ep)

But Injoo choose to leave and back to save Hwayoung, who got kidnapped by Sangah bcs she still on dangerous life zone (she still wear the heels)

Conclusion:

Shoes exchange is symbolism of series' main theme: capitalism;

Because in order to give/receive something, there's something that you need to pay

But at same time, shoes exchange is also symbolism of act of love between Injoo and Hwayoung

Both Hwayoung and Injoo are very similar. They grew up in similar poverty condition that made them understand each other and could feel each others' pain; it got symbolized on how they have same shoes size, and many of their shot are like they are half to each other, or looks same

It made them want to share things to each other because that condition; and it got symbolized through shoes exchange

But sadly, in world of capitalism, there's things that they need to pay; and it got symbolized through their matching scars - symbol of battle scars that they receive because "the shoes exchange"

#little women#tvn little women#little women korea#kim go eun#choo ja hyun#oh in joo#jin hwa young#oh injoo#jin hwayoung#youngjoo#hwayoung x injoo#k drama#kdrama#korean drama#tvn#tvn drama#theory#analysis#little women 2022#sapphic ships#ggonekim#작은아씨들#오인주#진화영#화영인주#김고은#추자현#little women theory#little women analysis

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

i know the snorkmyden B plot from episode 6 isn’t comparable to the snufmin A plot from episode 8 but i still like comparing them anyway cause i just think it’s so funny how much more mature the girls are when it comes to sorting out problems between them and quickly and clearly sharing their feelings with and apologising to each other, whereas the boys continue to dance around their feelings and are so nervous to just be completely honest and transparent with each other and i know it’s cause their relationship and individual needs and wants really are delicate and uncertain but it’s still funny to compare that pussyfooting to the girls’ no-nonsense problem solving

#i guess i also like it cause it ties into the theme this brand has always had of the women being more competent than the men gjkd#now i sound like im being mean to snufmin i dont mean to i understand their fear surrounding their relationship but i think i can both#appreciate the delicacy and rawness of it whilst also poking a little fun at how silly they can seem because of it#moominvalley#moominvalley analysis#not really an analysis but ehhh#snufmin#snorkmyden

70 notes

·

View notes