#jules germain cloquet

Text

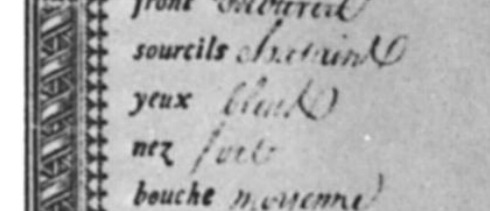

La Fayette's eye colour

A while ago I stumbled over this post where different passages from secondary sources were compiled in order to determine La Fayette’s physical appearance. These different books quote him as having blue, brown or green eyes of varying shades. Since three different eye colours is a bit much for one person and since I rather confidentially answered a question about La Fayette’s eye colour in the past, I thought it worthwhile to revisit the topic.

I had based my original answer on the existing portraits painted of La Fayette. In portraits taken from life (or portraits that were direct copies of portraits taken from life) we see him with distinctively brown eyes.

I hope we all can see why I thought brown eyes were the forgone answer to the question. But it appears that I was wrong. This time I also turned to the memoirs of Jules Germain Cloquet, La Fayette’s close friend and family physician. He wrote:

His head was large; his face oval and regular; his forehead lofty and open; his eyes, which were full of goodness and meaning, were large and prominent, of a greyish blue, and surmounted with light and well-arched, but not bushy eyebrows.

Jules Germain Cloquet, Recollections of the Private Life of General Lafayette, Baldwin and Cradock, London, 1835, p. 8.

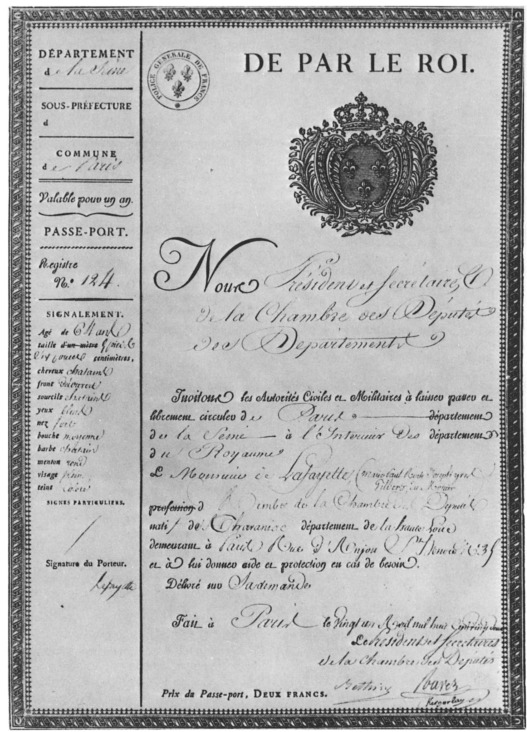

We see that Cloquet was certain that La Fayette’s eyes were not brown but blue. But there is more. Here is the excerpt of a passport given to La Fayette on April 20, 1822:

Daniels, M. F. (1972). The Lafayette Collection at Cornell. The Quarterly Journal of the Library of Congress, 29(2), 95–137. http://www.jstor.org/stable/29781504 (05/02/2023).

I think there is rather little evidence to back the claim that La Fayette had green eyes. While I feel more inclined to believe the written sources, I am also confused as to why so many artists, over the span of roughly fifty years, painted La Fayette with brown eyes. I do know that the lighting and the angle can have a huge impact at the colour you perceive … but still?

Unknown title [La Fayette as a teenager], by unknown artist, 1773 or earlier

Unknown title [Portrait of La Fayette on the occasion of his wedding], by unknown artist, 1773/1774

Gilbert du Motier de La Fayette, en uniforme de l'armée continentale by Charles Wilson Peale, 1779

Marie Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert Motier, Marquis De Lafayette by Charles Wilson Peale, 1779/1780

Washington, Lafayette & Tilghman at Yorktown by Charles Wilson Peale, 1784

Marquis de Lafayette by Ary Scheffer, 1822

Portrait of Lafayette by Ary Scheffer, 1823

Marquis de Lafayette by Samuel Finley Breese Morse, 1825

Portrait of Marquis de Lafayette by Samuel Finley Breese Morse, 1826

Portrait of Lafayette as an old man by Louise-Adéone Drölling, 1830

#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#correction#art#charles willson peale#samuel finley breese morse#french history#american history#american revolution#tour of 1824 1825#jules germain cloquet#eye colour

47 notes

·

View notes

Photo

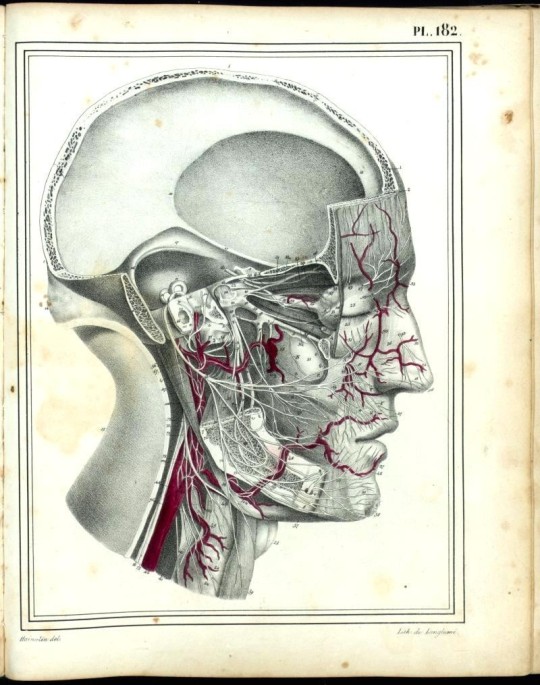

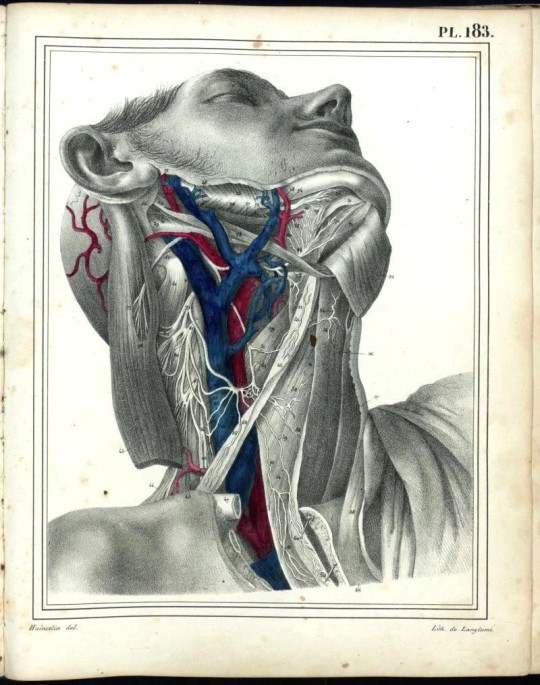

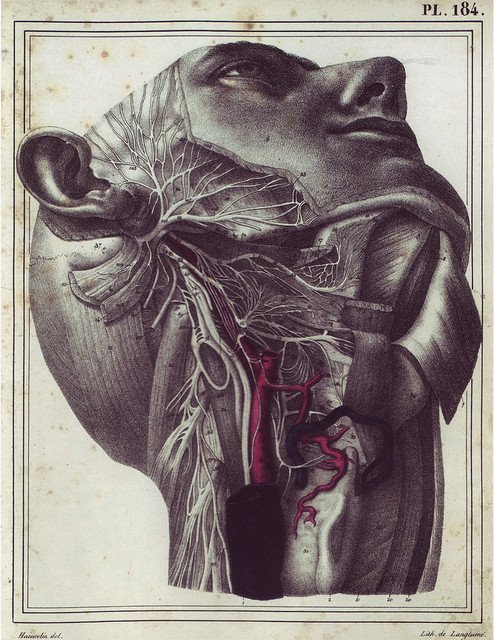

Manuel D'Anatomie Descriptive Du Corps Humain by Jules Germain Cloquet (1790-1883)

#anatomy#human anatomy#anatomy illustration#medicine#medical illustration#jules germain cloquet#medical art#medical lithograph#medical humanities#medical history#history of medicine#dissection#human dissection#medic#anatomical illustration#anatomical diagram#human biology#biology#science#scientific illustration

746 notes

·

View notes

Link

I hope that’s the person who wrote about Lafayette, but I’m not so sure..🤔 🤔

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jules Germain Cloquet

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

Georges de La Fayette's Reaction to the Death of his Father

La Fayette only son Georges was everything that a father could have wished for. Georges was the perfect picture of filial devotion – to the point where some historians and authors (including me) have argued that George almost lost himself in his devotion to his father. He was named after his father’s friend and parenteral figure, he followed his father into the army and into politics, his fathers believes where his believes. He went to America, first alone as a refugee and later as a companion of his father in La Fayette’s moment of triumph. He risked his life to retrieve his father’s sword and married the daughter of his father’s friend.

While the death of La Fayette was a terrible hard blow to all his children, grand-children, great-grand-children, relatives, and friends, let us have a look at the man who, on this day in 1834, became the new Marquis de La Fayette:

From every side burst forth the sobs of the bystanders, which had hitherto been checked by their religious respect and by their fear of disturbing the last moments of Lafayette. Piercing and stifled shrieks strongly expressed the grief to which every heart was a prey. George Lafayette, his eyes motionless and bathed in tears, remained for some time in a state of stupor, from which he recovered only to address to his father his adieux, that were scarcely audible through the sobs torn from him by despair His wife endeavored to sustain and aid him to support the blow which had smitten him, but, insensible to every other feeling than that of poignant anguish, he heeded not the consolations lavished on him by her tenderness. How noble was his grief! How deeply he felt his loss! And oh! how fervently had he prayed that his father’s parting breath might still be spared, or that his spirit, as it hovered on the verge of eternity, might be joined his own.

Jules Germain Cloquet, Recollections of the Private Life of General Lafayette, Baldwin and Cradock, London, 1835, p. 279.

This scene is utterly heartbreaking to read, and it is not only now, with the distance of almost 200 years, that Georges strong affection was noted. His deep grief and total devotion to his father were already noted by a family friend at the time of La Fayette’s passing:

On the painful occasion which I have just described, M. George Lafayette, the worthy and modest heir of his father’s virtues, presented us with an admirable example of filial piety. He entertained for his parent that religious respect which is usually granted only to the memory of beloved individuals. He knew by experience his high qualities, his domestic virtues, and proved his affection for him by unbounded devotion to his slightest wishes. But if he was justly proud of the author of his days, the General on his side felt the value of such a son, and reaped the reward of the care which he had taken of his education, and of the advice and example which he had given to him.

M. George Lafayette had long attached himself as it were to his father’s steps, had followed him in his travels, and had been witness to his triumph at the period of his last visit to the United States. How heartfelt must have been his gratification, at seeing that great nation confer on his parent such striking and unanimous marks of gratitude: -- at seeing the American people mingle their prayers with his for the happiness and the preservation of the friend of Washington and Franklin! M. George Lafayette, the worthy pupil of Washington, was gifted with a mild but at the same time a firm and frank disposition. He bore with courage the apprehensions by which he was assailed during his father’s illness, concealed from him his anguish, and like a consoling genius never once quitted his bedside. It was thus that he discharged the duties of filial love, -- those sacred duties, a feeling of which has been deeply implanted by nature in every virtuous heart, and the performance of which presents an affecting example at the present day, when respect for old age, love of parents, and the ties of blood, have so great a tendency to be weakened; when a selfish spirit of unlimited and mistaken independence hardens the heart, and tends to produce errors no less fatal than those which were caused by abuse of authority in days of ignorance and degradation.

Jules Germain Cloquet, Recollections of the Private Life of General Lafayette, Baldwin and Cradock, London, 1835, pp. 277-278.

Georges is nobodies first association with the title “Marquis de La Fayette” and while he is not forgotten by history, he forever stands in his father’s shadow. Not only does he stand unjustly in his father’s shadow (for Georges was a fascinating and intriguing person in his own right), no, he stands there completely voluntarily. And while I can deeply resonate with this kind of devotion, I also have to admit, that it is a crying shame that there is not more about Georges, Marquis de La Fayette, as an individual. Not only in relation to his father or famous godfather, not in relation to anyone but himself.

#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#georges de la fayette#french history#american history#history#1834#on this day in history#otd#otdih#jules germain cloquet#poor georges :-(

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

I love him with too much tenderness to make any distinction between his desires and mine; and I am too great an enemy to oppression of every description to place a restraint on the wishes of a beloved son nearly twenty years of age.

La Fayette about his son Georges in a letter to his friend Joseph Masclet.

Jules Germain Cloquet, Recollections of the Private Life of General Lafayette, Baldwin and Cradock, London, 1835, p. 131.

#quote#letter#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#georges de la fayette#joseph masclet#jules germain cloquet#1799#french history#history

34 notes

·

View notes

Note

How did Adrienne’s death affect Lafayette?

Dear @mxtallmadge,

thank you for the question! La Fayette was greatly affected by Adrienne’s death. She was his partner after all and although Adrienne was not particularly old when she died, the two of them had been married for 34 years at that point. Together they had danced at balls in Versailles and languished in a wretched cell in Olmütz. They had endured separation due to war and travels as well as public scrutiny – they also have carefully raised their children as a family. Despite all his flaws as a husband, La Fayette loved Adrienne dearly and deeply and her death shattered him. I believe things were made worse because La Fayette believed himself (at least partially) guilty for Adrienne’s death. Adrienne became ill while voluntarily sharing his imprisonment at Olmütz. When she and her two daughters, Anastasie and Virginie, first joined La Fayette, he naturally was overjoyed to be reunited with his family, but he soon urged them to leave him alone and stay somewhere more comfortable. The women refused. When Adrienne became ill (and the prison doctor proofed to be rather useless) the director of the prison offered Adrienne to leave the prison and visit a doctor in the city – under the condition that if she were to leave, she may never return to the prison and thus to her husband. La Fayette practically begged Adrienne to go but she once again refused.

His wife’s death was an incredible hard blow for La Fayette, but in the more than 25 years that he survived Adrienne, he learned to deal with his grieve. Nevertheless, Adrienne was still a very prominent figure in the family’s life. Here is what La Fayette’s family physician and friend wrote:

He [La Fayette] always spoke with respect and tenderness of both his parents, whom he lost almost in his infancy. In his children he cherished the memory of their mother, (Mademoiselle de Noailles,) whom he had loved most tenderly, and whose name he never mentioned but with visible emotion. One day during his last illness, I surprised him kissing her portrait, which he always wore suspended to his neck in a small gold medallion. Around the portrait were the words “Je suis à vous”, and on the back was engraved this short and touching inscription, “Je vous fus donc une douce compagne: eh bien benissez moi.” I have since been informed that regularly every morning Lafayette ordered Bastien [his valet] to leave the room, in which he shut himself up and taking the portrait in both hands, looked at it earnestly, pressed it to his lips, and remained silently contemplating it for about a quarter of an hour. Nothing was more disagreeable to him than to be disturbed during this daily homage to the memory of his virtuous partner.

Jules Germain Cloquet, Recollections of the Private Life of General Lafayette, Baldwin and Cradock, London, 1835, p. 35.

The account continues:

The room which now serves for the Museum was formerly the entrance to the apartment of Madame Lafayette. After the death of his wife, Lafayette walled up the door of communication, and the apartment, such as it was at that period, has since remained closed. On certain stated days, however, the General repaired thither by a back door, either alone or in company with his children, to pay homage to the memory of Madame Lafayette, who was, in every respect worthy of the tender and respectful recollections of her whole family. On approaching the sanctuary, the visitor is seized with a feeling of pious respect (…)

Jules Germain Cloquet, Recollections of the Private Life of General Lafayette, Baldwin and Cradock, London, 1835, p. 211.

La Fayette also had bust of Adrienne in his private chambers.

La Fayette wrote in his reply to his friend Masclet’s letter of condolence:

I willingly admit that under great misfortunes I have felt myself superior to the situation in which my friends had the kindness to sympathize; but at present I have neither the power nor the wish to struggle against the calamity which has befallen me, or rather to surmount the deep affliction which I shall carry with me to the grave. It will be mingled with the sweetest recollections of the thirty-four years during which I was bound by the tenderest ties that perhaps ever existed, and with the thought of her last moments, in which she heaped upon me such proofs of her incomparable affection.

Jules Germain Cloquet, Recollections of the Private Life of General Lafayette, Baldwin and Cradock, London, 1835, p. 36.

Letters from this time in particular give us a deep insight into La Fayette’s inner life. During January of 1808, right after Adrienne’s death, La Fayette wrote a very long letter to his friend and the brother of his son-in-law (Anastasie’s husband), La Tour-Maubourg – probably one of the longest letters he ever wrote. There he detailed Adrienne’s last days and how she, how he, how the whole family felt and what they experienced. It is a truly touching and emotional letter that bears witness to an extraordinary relationship. I have posted a full transcript of the letter here, but since the letter is rather long, here are some particularly memorable lines:

I have not yet written to you, my dear friend, from the depth sees of misery in which I am plunged. You have already heard of the angelic end of that incomparable woman.

I feel I must again speak of it to you. My grieved heart loves to open itself to the most constant, the dearest confident of all its thoughts. As yet you have always found me stronger than circumstances, but now this event is stronger than me. Never shall I recover from it. During the thirty - four years of an union in which her tenderness, her goodness, the elevation of her mind, charmed, adorned, honoured my life, I felt myself so used to all that she was to me, that I could not distinguish it from my own existence. She was fourteen, and I was sixteen, when her heart amalgamated itself with everything that could interest me. I knew I loved her, I knew I needed her, but it is only now that I can distinguish what life which I had thought was to have been entirely devoted to worldly matters. The foreboding of her loss had never crossed my mind before, when, on leaving Chavaniac with George, I received a note from Mme de Tessé. I was struck to the heart. On arriving in Paris after a rapid journey, we found her very ill; there was a slight improvement the next day, which I attributed to the pleasure of seeing us; but soon afterwards her head was affected. (…)

She often begged of me to remain in the room because my presence calmed her. Sometimes, however, she would ask me to go and attend to my business, and when I answered that I had nothing else to do than to take care of her: “How good you are, she would exclaim with her feeble though pénétrante voice, you are too kind, you spoil me, I do not deserve all that; I am too happy.” (…)

On all these last evenings, when she thought I was going to leave her, she would ask me for my blessing. I spoke to her of the happiness of our union, of my tenderness; she took pleasure in hearing me repeat the assurance of my love. “Promise me, she said, to preserve that affection well believe that I promised. (…)

The next day, before she became quite speechless, Mme de Montagu and my daughters, fearing that my presence might prevent her from praying at her ease, asked me to leave them. My first impulse was to refuse their request, however tenderly and timidly made; I had a passionate de sire to occupy her thoughts exclusively. However, I repressed my feelings, and gave up my place to her sister. I was scarcely gone, when she called me back. So soon as I got nearer, she again took my hand in hers, saying: “Je suis toute à vous”. These were her last words.

Mme de Lasteyrie, Life of Madame de Lafayette, L. Techener, London, 1872, pp. 397-432.

Another thing that I would like to mention is the fact that La Fayette never remarried. When Adrienne died and even after a suitable mourning period was over, he was still young enough to remarry and there certainly was no shortage of women who would have been very happy to become the second Marquise de La Fayette. Yet, that never happened. La Fayette did not live like a monk after Adrienne’s death – he always had been a ladies’ man. While we can be quite certain that there were no further affairs, he liked to occasionally flirt with young women (and they liked to flirt with him.) His hands probably also wandered here and there. Things were different at La Grange though. La Grange had been brought into the marriage by Adrienne and she loved the chateau in the country. Here, La Fayette was much more reserved and not at all flirty. La Grange was still Adrienne’s place.

I hope the answer was useful and I hope you have/had a great day!

#ask me anything#mxtallmadge#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#adrienne de lafayette#adrienne de noailles#virginie de lafayette#french history#history#french revolution#letter#american history#american revolution#sebastien wagner#jules germain cloquet

36 notes

·

View notes

Note

georges was really badly wounded during his military time, what was the injury??

Dear Anon,

Georges was indeed wounded during the first Battle of the Mincio River, also known as the Battle of Pozzolo on December 25 and 26, 1800. He was hit by three bullets and while this at first seems like grievous injuries, they really were not. La Fayette said so himself and he was not in the habit of making light of his children’s health. He wrote in a letter to his friend Joseph Masclet on February 17, 1801:

I have not this long while heard from you, my Masclet: sure I am, nevertheless, that you do not your friend, and that you have been pleased with George’s good fortune on the Mincio. He was in the wing, and under the general who fought and won the action. The eleventh regiment of hussars was the most distinguished. My son had for his share three bullets, but slight wounds. General Dupont tells me he had named him in the account of the battle. George insisted on the suppression of the mention made of him, unless the same was done in favour of his wounded comrades. His wounds would have been sooner cured, had he not remained with the regiment as long as there was something to do, which caused an inflammation and a dépôt in his arm. But when the eleventh hussars made the blockade of the forts of Verona, which put them out of the way of danger, George got into the city, where he was very well taken care of. When General Dupont saw him last he was in good train of recovery, although he yet wore a scarf. His side was still less damaged than the arm So that the danger of the battle, which has been great, being over we have had nothing to fear. and much to rejoice at. I give you those details as I know you will enjoy them. Here is a good, honourable, solid peace.

Jules Germain Cloquet, Recollections of the Private Life of General Lafayette, Baldwin and Cradock, London, 1835, pp. 229-230.

Georges had injuries to his arm and side, followed by an inflammation and swelling – nothing too pleasant but also nothing that put him in great danger. There is no mentioning of any permanent damage to his arm or upper body.

I hope I could help you and I hope you have/had a great day!

#ask me anything#anon#georges de la fayette#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#french history#napoleonic wars#sixth coalition#1800#1801#letter#joseph masclet#battle of minico#battle of pozzolo#jules germain cloquet#general dupont

17 notes

·

View notes

Note

Since you made a post about Gorges attachment to his father and there relationship, I wanted to ask how his relationship with his mother was like?

I’m sure Adrienne loved her son and cared for him very deeply so much so as to make a hard decision to let him go all the way to America, but I think we never get to see his thoughts and(or) actions towards his mother.

Plus Adrienne died the day before his birthday, that’s something one is going to remember for the rest of his life. The only thing that I now of is that he cried the day after his mothers death, but I don’t know were I saw that… (if you know pleas tell me!)

Dear Anon,

that is a very fitting question, thank you for that.

Georges’ relationship with his mother was, in my understanding, different but not less affectionate than the relationship he had with his father. These differences are based on two main factors.

First, Adrienne died on Georges 28th birthday – and you are absolutely right, these events fundamentally changed the family’s perception of that day. While, with 28 years of age, Georges was not any longer a small child, he still was fairly young. Now without a mother, he could devote the next 26 years of his adult life to his father and his father alone. After her death, Adrienne was almost worshipped like a saint by her family, a sentiment that La Fayette championed and installed in his children. She was still as well their beloved mother, but La Fayette must have felt more “real” to Georges.

In his children he [La Fayette] cherished the memory of their mother, (Mademoiselle de Noailles,) whom he had loved most tenderly, and whose name he never mentioned but with visible emotion.

Jules Germain Cloquet, Recollections of the Private Life of General Lafayette, Baldwin and Cradock, London, 1835, p. 35.

Second, Georges could follow his father’s steps in a way that he could not do with his mother. La Fayette’s life was marked by a few very distinctive parameters like the military, his political opinions, and his relations to America. These were all things that Georges could relatively “easy” emulate. Adrienne’s life on the other hand was marked by more “vague” aspects such as religious piety, domestic virtuous and charity. That is not to say that Adrienne had no political opinions or the like or that Georges did not share his mother’s more private qualities – on the contrary. These were simply less measurable, less obvious.

La Fayette and Adrienne were uncommonly close involved in their children’s upbringing for a couple of their station and time. Adrienne especially thrived in her love for her children. There is a quote in Virginie’s writings about Adrienne that gives a clear picture of Adrienne’s affection for Georges and his devotion to her:

Twice only her [Adrienne’s] excitement became intense. It was then the wanderings of maternal love. One day George, to prevent her speaking too much, had, for several hours, kept away from her room. When he came in again, she evidently thought he had just returned from the army. The wildness of her joy on seeing him made her heart beat in a fearful manner. Another time she fell into an ecstasy of joy at the thought of an anniversary dear to our hearts, of the day when twenty-eight years before she had given me [La Fayette] George. That anniversary was the day of her death.

Mme de Lasteyrie, Life of Madame de Lafayette, L. Techener, London, 1872, pp. 413-414.

While both Adrienne and La Fayette loved all their children deeply and never discriminated based on their children’s sex, it probably was Adrienne who was the happiest that Georges was a son and not another daughter.

Adrienne was very anxious for Georges whenever he was away with the army, and I have always wondered if her anxiety may have played a small role in his decision to ultimately quit the military. Regardless, the times when he was on leave and at home with the rest of the growing family, were among the happiest of her life.

Several times during his life, most remarkably during the French Revolution, was Georges parted from his family. These partings were almost always (exceptions being travels and his time in the army) organized by Adrienne. It was not only her who send him to America, it was also her who arranged for him to be educated away from home.

My mother then made a painful sacrifice. She thought that my father’s constant occupations and that his high position might be prejudicial to her son’s education if he remained at home, by unavoidably diverting him from his studies and causing feelings of pride and vanity to arise in his heart. She hired therefore for M. Frestel and his pupil, then six years old, a small lodging, rue Saint Jacques, where she frequently visited them.

Mme de Lasteyrie, Life of Madame de Lafayette, L. Techener, London, 1872, p. 178.

These partings, in times of peace and in times of war, were always hard on Adrienne (and the rest of the family as well, Virginie wrote that the sisters had the “happy lot” of being able to remain with their mother) but she always did what she thought was best for Georges and her children in general.

As to the passage you read, that sadly does not ring any bells for me, but Georges probably cried an awful lot around this time. I can certainly have a look and see if I can find the passage for you, but I would need a few more information for that. Did you read that on the internet, in a book or a letter? Was it a primary or secondary source?

This answer feels a bit like all over the place and I apologize for that. In my head, I have a fully fleshed out picture of Adrienne’s and Georges’ relationship, but I had a hard time finding the right words to express this relationship. I hope this helped you nonetheless and I hope you have/had a great day!

#ask me anything#anon#adrienne de lafayette#adrienne de noailles#georges de la fayette#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#jules germain cloquet#virginie de lafayette#1807#books#french history#american history#french revolution#history

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

The characters of Lafayette’s writing were small and well formed, and yet rather difficult to be read; and it is a remarkable fact, that his English was much more legible than his French writing.

Jules Germain Cloquet, Recollections of the Private Life of General Lafayette, Baldwin and Cradock, London, 1835, p. 18.

I sometimes feel so validated by Cloquet’s writing. :-)

27 notes

·

View notes

Note

also, you were talking about georges' feats in the military; could you share those stories if ya have 'em? i don't think I've ever read any of them before

thank youu :))

Dear @msrandonstuff,

of course I can!

Many of the sources I am going to rely upon are La Fayette’s letters to friends and family members. Because like every proud Papa, La Fayette liked to tell everybody what his son did and accomplished.

Georges was a good officer who took his role very serious and who not only freely choose this occupation for himself and enjoyed it, but who also understood how his military conduct was connected to his and his family’s honour. Here is a description of Georges’ military qualities from an undated letter La Fayette wrote his friend Amé Thérèse Joseph Masclet:

The fact is, that George, who is a republican patriot, -- and I have met with few such in my lifetime, -- has, besides a passion for the military profession, for which I think him adapted, as he possesses a sound and calm judgment, a just perception, a strong local memory, and will be equally beloved his superiors, his comrades, and his subordinates. I love him with too much tenderness to make any distinction between his desires and mine; and I am great an enemy to oppression of every description place a restraint on the wishes of a beloved son twenty years of age. I could joyfully see him with honourable scars, but beyond that supposition have not the courage to contemplate existence.

Jules Germain Cloquet, Recollections of the Private Life of General Lafayette, Baldwin and Cradock, London, 1835, p. 131.

While, as La Fayette wrote, he thought Georges very much suited for the military and although he liked the idea of Georges following in his steps, he was above forcing his son to follow a certain path. La Fayette believed children should make their way, independent of their parents’ wishes – although the parents should support and guide their child because a father for example knows his son differently than the child knows itself.

Georges joined the military and was made a sous-lieutenant around the time of the Battle of Marengo. He served in succession as an aide-de-camp to the Generals Canclaux, Dupont and Grouchy. Towards the end of Georges’ military career, Marshal Joachim Murat wanted to appoint Georges as his officier d’ordonnance but Napoléon was against it and the appointment never came to pass.

Georges was wounded in the Battle of Minico/Battle of Pozzolo on December 25, 1800. La Fayette wrote the following about his son’s injuries and conduct to Masclet on 28 Pluviôse [February 17] [1801]:

I have not this long while heard from you my dear Masclet: sure I am, nevertheless, that you do not forget your friend, and that you have been pleased with George’s good fortune on the Mincio. He was in the wing and under the general who fought and won the action. The eleventh regiment of hussars was the most distinguished. My son had for his share three bullets, but slight wounds. General Dupont tells me he had named him in the account of the battle. George insisted on the suppression of the mention made of him, unless the same was done in favour of his wounded comrades. His wounds would have been sooner cured, had he not remained with the regiment as long as there was something to do which caused an inflammation and a dépôt in his arm. But when the eleventh hussars made the blockade of the forts of Verona, which put them out of the way of danger, George got into the city, where he was very well taken care of. When General Dupont saw him last, he was in good train of recovery, although he yet wore a scarf. His side was still less damaged than the arm. So that the danger of the battle, which has been great, being over, we have had nothing to fear, and much to rejoice at. I give you those details as I know you will enjoy them. Here is a good honourable solid peace.

Jules Germain Cloquet, Recollections of the Private Life of General Lafayette, Baldwin and Cradock, London, 1835, pp. 229-230.

Georges wounds were without serious consequences, and he fully recovered. He next distinguished himself during the Battle of Eylau on February 7-8, 1807. La Fayette again wrote to Masclet:

George was on the eve being appointed to the rank of captain, and even the Emperor, before he went to Italy. had promised his promotion to Generals Grouchy and Canclaux and to M de Tracy [Georges’ father-in-law]. Since that period, my son has served as volunteer aide de camp at the embarkation at Helder, at Ulm, at Udine, and in the new war at Prenzlaw, at Lubeck, at Eylau, where he had the good fortune to save his general; and at Friedland, where Grouchy commanded the wing of the cavalry which routed the Russians only at the seventh charge. The promotion promised before all these events, and for which several applications had been made by the principal ministers and general officers, has been constantly refused, so that George, although the senior lieutenant of the division, has abandoned all idea of advancement. The peace will bring him back to us, as he is a volunteer: we expect him immediately.

Jules Germain Cloquet, Recollections of the Private Life of General Lafayette, Baldwin and Cradock, London, 1835, p. 106.

La Fayette also wrote to his friend Thomas Jefferson regarding Georges’ conduct at Eylau. The Marquis wrote on April 29, 1807:

My Son and Son in Law are in the Army of Poland under the Emperor’s Command, the one as a Volunteer Aid de Camp to General Grouchy, the other as an Aid de Camp to General Beker, Both my personal friends—George Had the Happiness at the Bloody Battle of Eylaw to save the Life of His General Whose Horse Had been killed and fell on His Bruised thigh, at a Moment when our troops were Overpowered and the Russians Giving No Quarter—My Son Lept down, disengaged Grouchy from Under His Horse, Gave Him His own, and so Both Got of. Since which time, and probably on that Account, there Has been a new Manifestation of a Sentiment already and I may say officially Expressed after the Affair of Prentzlaw when George Had the Good fortune to be Approved for His Conduct—it is that not only He Never Has Any promotion to Expect from the Emperor But that His Zeal in the Active Army is so far displeasing as to put Him in immediate danger to be sent, in His Rank of Lieutenant, to Some Remote Regimen—He Has Consequently determined to Return to Us, either to Serve in an interior Staff, or to Rest Himself at La Grange, as Soon as the Circumstances of the Army will permit His Leaving the division to which He is Attached, unless a proper Explanation Speedily takes place.

“To Thomas Jefferson from Marie-Joseph-Paul-Yves-Roch-Gilbert du Motier, marquis de Lafayette, 29 April 1807,” Founders Online, National Archives, [This is an Early Access document from The Papers of Thomas Jefferson. It is not an authoritative final version.] (05/24/2023)

To top the list off, La Fayette also wrote to James Madison on June 10, 1807:

My Son and Younger Son in Law are in the Grand Army, The later an aid de Camp to our friend Gnl. Becker Now Chef d’Etat Major to the Wing Under Mal. Massena, George a Volonteer aid de Camp to Gnl. Grouchy. In that Independant Situation He Has determined to Go on, Very Happy in the Esteem and Kindness of our Numerous friends at the Army and Among its Chiefs, But Having Had Strong Reasons Not to Expect Even the Usual and Common Course of promotion. It Has been His fortunate lot, at the Bloody Battle of Eylaw, to Save the life of His Beloved General, Brother in law to Mr. Cabanis.

“To James Madison from Marie-Adrienne-Françoise de Noailles, marquise de Lafayette, 10 June 1807,” Founders Online, National Archives, [This is an Early Access document from The Papers of James Madison. It is not an authoritative final version.] (05/24/2023)

Georges had put himself in great danger during the Battle of Eylau and his courage was noted. Even beside that, Georges had done very well in the past and was respected by his superiors – the only problem; he was a La Fayette and Napoléon was petty. He and his brother-in-law (the husband of his younger sister Virginie) therefore quitted the military after the end of the military season in 1807 – to the infinite joy of his mother Adrienne.

She [Adrienne] bore with gentle fortitude the anxieties of which my brother and my husband were the object during the campaigns of 1805 and 1806. She heard with joy of George’s good fortune when he saved his general’s life at the battle of Eylau. The peace which followed brought on for her a period of unmingled happiness. I [Virginie] shall not attempt to describe it to you. I have scarcely dwelt upon those peaceful years we passed at Lagrange, although, during that whole period, I was my mother's daily companion. But I could only repeat to you that we were happy. At the end of the spring of 1807, it seemed that God had accomplished all my mother’s desires in this world. As for myself I cannot fancy it possible to be happier than I was during the period which elapsed from the peace and my eldest daughter’s birth up to the beginning of the fatal malady.

Mme de Lasteyrie, Life of Madame de Lafayette, L. Techener, London, 1872, pp. 391-392.

This is pure speculation on my part, but I could imagine that Georges’ leave from the military could also have been influenced by family reasons. In the above quoted letter to Madison, La Fayette mentioned that Georges’ little daughter of four weeks had just died and I could imagine that, just like Henriette’s death was a waking-call for a Fayette, Georges’ wanted to be closer to his wife, children and family.

Adrienne also was not the only one who was frequently anxious for Georges and Louis (Virginie’s husband). La Fayette wrote on October 16, 1805 to James Madison:

My Son Serves in the Grand Army as an Aid de Camp to General Grouchy—My Son in Law Louïs Lasteyrie Serves there also as an officer of dragoons—two Young Wives, a Sister, and Mother Are With Me at La Grange—and While I Consider their Anxiety and My Own for the Sake of our Young Soldiers, I am inclined to feel Less Regret, and I know You Will find More Cause to Approve me for Having Yelded to the Opinion of the Ambassadors and Mine Respecting the present obstacles to An immediate Voyage (…).

“To James Madison from Lafayette, 16 October 1805,” Founders Online, National Archives, . [Original source: The Papers of James Madison, Secretary of State Series, vol. 10, 1 July 1805–31 December 1805, ed. Mary A. Hackett, J. C. A. Stagg, Mary Parke Johnson, Anne Mandeville Colony, and Katherine E. Harbury. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2014, pp. 434–436.] (05/24/2023)

I hope I could answer your question and I hope you have/had a wonderful day!

#ask me anything#msrandonstuff#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#georges de la fayette#virginie de lafayette#joachim murat#napoleon bonaparte#napoléon#marshal grouchy#thomas jefferson#james madison#joseph masclet#founders online#french history#american history#history#jules germain cloquet#battle of eylau#battle of minico#napoleonic wars#adrienne de lafayette#adrienne de noailles#1800#1801#1805#1806#1807#letters

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

btw I dom't know if I'm misremembering these things so 1. I've read somewhere that lafayette died holding that necklace of Adrienne, but I can't find it anymore, is that true? and 2. I don't know if I read here or not, but did lafayette used to they stories to the girls in Olmütz? and in another notez do we have records on what they did in Olmütz to like, pass some time and stuff?

Thank you <3

Dear @msrandonstuff,

let us tackle your questions one by one, shall we? :-)

First, yes, that is true. La Fayette’s physician and family friend Jules Cloquet Germain for example wrote in his book:

One day during his last illness, I surprised him kissing her portrait, which he always wore suspended to his neck in a small gold medallion. Around the portrait were the words, “Je suis à vous” and on the back was engraved this short and touching inscription, “Je vous fus donc une douce compagne: eh bien! benissez moi.” I have since been informed that regularly every morning Lafayette ordered Bastien to leave the room, in which he shut himself up, and taking the portrait in both hands, looked at it earnestly pressed, it to his lips, and remained silently contemplating it for about a quarter of an hour. Nothing was more disagreeable to him than to be disturbed during this daily homage to the memory of his virtuous partner.

Jules Germain Cloquet, Recollections of the Private Life of General Lafayette, Baldwin and Cradock, London, 1835, p. 35.

Second, again, yes, La Fayette used to read to his daughters in the afternoons during their shared imprisonment. Virginie described their life in her book the following:

This explains how save in the beginning of the illness we found pleasure in our quiet life My sister supplied the place of outdoor workmen she even made shoes for my father But her principal occupation was to write under his dictation on the margins of a book My mother attended to my education and used to read with me but the margins of a book the tooth picks and the bit of Indian ink were things too precious for my use In the evening my father used to read aloud to us I still remember the pleasure of those moments.

Mme de Lasteyrie, Life of Madame de Lafayette, L. Techener, London, 1872, p. 359-360.

Virginie mentions that they were not allowed to celebrate mass but mass was celebrated in a little church right by the prison and I think they were able to hear at least a little bit of that. Letter writing was generally permitted but only a few letters, written under supervision, to a selected of people. Adrienne busied herself with writing her mother biography in the margin of a book, letter writing (as far as it was permitted) and lobbying for the prisoners, overseeing the education of her daughters and practicing her religion. Anastasie and Virginie were crafty, made and mended cloths, were educated, both of them practiced their religion and Anastasie “painted” with what little they had available. La Fayette was only allowed to see his wife and children for a few hours in the evening and probably did nothing “more” with them than reading and talking. He himself had otherwise no company and even less to do, especially since privileges like letter writing, books and the likes were continuously granted to him and then again taken away from him.

When you look into their time in Olmütz (and La Fayette’s time in prison before that), you can not help but admire their inner strength and resilience. This is also true for Georges, he might have not been imprisoned, but the situation was not necessarily easier for him!

I hope this helps and I hope you have/had a great day!

#ask me anything#msrandonstuff#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#adrienne de lafayette#adrienne de noailles#anastasie de lafayette#virginie de lafayette#georges de lafayette#jules germain cloquet#olmütz#lafayette in prison#french history#french revolution#history

23 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey! How are you doing? Hope you're having a lovely day whenever you read this!!

So, I have two different things to ask, but I'll make them both, sorry to be bothering and hope this doesnt get too long lol

1st. I know that Adrienne was a deeply Christian woman from birth to death, and I know that in some time in her life she helped out Protestants (?). So, my question here is basically, did she always helped people from other religions like that? or that was just something she used to do out of charity without caring too much about those people? Did she always sort of have it in her or did she only started it because of everything that was happening in the country? (dont know if i worded that in a understandable way, if i didnt let me know)

2nd. did the lafayette's (and their respective families) owned any sort of pets? (I've heard of that dog that Gilbert had and when he died, it went to live with his valet (?), but when did he got that dog too? did it simply appear in front of the house and it stayed? so many questions... so many questions... lmao)

Dear @msrandonstuff,

Don’t you worry, I am never bothered by asks! :-)

For the first question, Adrienne was a devout catholic. She was taught by her mother and the duchess d’Ayen always allowed Adrienne, her sisters and later La Fayette, when he moved in with the family, to question things. In my opinion that is not only a very healthy way to teach religion but also reduces prejudges. Adrienne's husband La Fayette was a great champignon of religious freedom. He wrote to George Washington on May 11, 1785:

102 ⟨Protestants⟩ in 12 ⟨France⟩ are under intolerable 80 ⟨Despotism⟩—altho’ oppen persecution does not now Exist, yet it depends upon the whim of 25 ⟨king⟩; 28 ⟨queen⟩, 29 ⟨parliament⟩, or any of 32 ⟨the Ministers⟩—marriages are not legal among them—their wills Have no force By law—their children are to Be Bastards—their parsons to Be Hanged—I Have put it into My Head to Be a 1400 ⟨Leader⟩ in that affair, and to Have their Situation changed—with that wiew I am Going, under other pretences to Visit their chief places of abode, With a Consent of 42 ⟨Castries⟩, and an other—(…) it is a Work of time, and of Some danger to me, Because none of them Would give me a Scrap of paper, or Countenance whatsoever—But I Run My chance—(…).

“To George Washington from Lafayette, 11 May 1785,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Confederation Series, vol. 2, 18 July 1784 – 18 May 1785, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1992, pp. 550–551.] (10/01/2022)

La Fayette was not lying, when he said that the undertaking could be somewhat dangerous to him. He wrote his letter in ciphers, tasked John Quincy Adams with delivering the letter personally because Adams was just returning to the States and asked Washington not to reply to his portion of the letter. Washington urged La Fayette to be carful and to that La Fayette replied on February 11, 1786:

(…) I thank you most tenderly, my dear General, for the Caution You Give me, which I will improve, and find that Satisfaction in my prudence to think it is dictated By You—I Hope, Betwen us, that in the Course of Next winter the affair of the protestants Will take a Good turn (…)

“To George Washington from Lafayette, 6 February 1786,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Confederation Series, vol. 3, 19 May 1785 – 31 March 1786, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1994, pp. 538–547.] (10/01/2022)

I got a bit distracted here so back to the question at hand. Adrienne was not opposed to Protestants gaining civil rights, but she was very opposed to every action that was directed against the Roman Catholic religion. She absolutely and staunchly refused to take mess from a priest who had sworn the civil oath and when La Fayette, himself more or less reluctantly, received the new Bishop of Paris for dinner, Adrienne made it a point to not partake. That was not just a private dispute about religious customs, but her absence at the dinner table made national headlines.

La Fayette was not happy about Adrienne’s behaviors during this time as he himself was between a rock and a hard place. He believed in religious freedom but was forced to carry out the politics of the assembly – politics that he often did not fully support. Adrienne was normally his strength and stay but in matters of religion she refused to bow even to her husband.

Adrienne had a firm stand on religious matters and she was willing to face serious repercussions for following her faith. I could not recall a specific event where Adrienne helped Protestants in particular and I also think that she did not knew a great many Protestants personally (simply because they were not in her private circles.) But Adrienne was also a gentle and carrying soul, a mother and someone who deeply believed in Christian charity, and I therefore can not imagine that she would have turned away someone needing or seeking her help, solely because of their religion.

As to the second question, yes, the La Fayette’s owned a number of animals but we have to differentiate here. After his release from prison and return to France, La Fayette started farming at La Grange. From Jules Germain Cloquet’s book we know that during the height of the farm, La Fayette owned 1000 – 1200 sheep, 30 – 40 cows and 100 – 150 pigs. Cloquet described the animal population of La Grange in great detail. How they came to the farm, how they were housed, how they were feed, how they smelled (the pigs emitted no “disagreeable smell”) and what not.

La Fayette also had a little ménagerie at La Grange for more exotic animals that he was gifted. Cloquet wrote:

One is a grated enclosure, a sort of ménagerie, in which Lafayette kept such foreign animals as were sent to him. After his return to France, he had received, from Governor Clarke, a young gray bear from the Missouri territory. Ever animated with the desire of being useful to his fellow-citizens, he refused to keep so rare an animal at Lagrange, and made a present of it to the professors of the Museum of Natural History, to be placed in their ménagerie.

Jules Germain Cloquet, Recollections of the Private Life of General Lafayette, Baldwin and Cradock, London, 1835, p. 213.

As to more domestic animals, you already mentioned La Fayette’s little white dog. Cloquet wrote:

During his malady, Lafayette was very fond of a small white bitch, which he had received, I believe, from Madame de Bourck, and which never quitted him. The animal, which was gifted with a remarkable degree of instinct, permitted nobody, except Bastien, to approach her master’s clothes when he was in bed, expressed joy or sorrow according as he felt better or worse, and might have served as a thermometer to indicate the state of his health. Since the General’s death, she has followed Bastien to Lagrange, but has never resumed her gaiety.

Jules Germain Cloquet, Recollections of the Private Life of General Lafayette, Baldwin and Cradock, London, 1835, p. 274.

La Fayette most likely owned more dogs during his lifetime, but I have neither numbers nor names for you. He was, however, quite knowledgeable about the different breeds and sometimes got his hands on dogs that his friends in America wanted to purchase. He was also a lover of horses and while he owned several horses during his lifetime, one is especially famous: Jean Le Blac – I wrote about him in a post on here but thanks to tumblr’s *exceptional* search-engine I can not even find my own post.

Hope that helped and I hope you day was/is just as lovely as mine was! :-)

#ask me anything#msrandonstuff#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#french history#french revolution#history#letter#adrienne de lafayette#adrienne de noailles#animals#founders online#religion#jules germain cloquet#memoirs#1785#1786#jean le blanc#tumblr being tumblr

22 notes

·

View notes

Note

has the marquis and thaddeus kosciusko ever met?

Hello Anon,

yes, La Fayette and Tadeusz Kościuszko did meet. Tadeusz was actually a frequent and well liked guest at La Fayette’s house while the former was in France. They seem to have been getting along very well, having made similar experiences and being a similar type of person. Despite their apparent closeness, there is not much published about their relationship.

The two of them also meet during the American War for Independence. They were probably among the most famous officers, especially among the most famous foreign officers. Tracking their respective actions during the war and going through La Fayette’s correspondences shows that they did not had that much contact during the Revolution.

La Fayette had furthermore an engraving of Kościuszko opposite his bed in his chamber:

Opposite to the bed may be seen a fine portrait of Marshal de Noailles. Among the engraved or sketched portraits are those of Fox, General Fitzpatrick, Thomas Clarkson, Henry Clay, the Duke de Noailles, Kosciusko, Jackson, Jefferson, Clinton, Crawford, Calhoun, Van Ryssel, the Count de Mun, Necker, Madame de Staël, Madame d Hénin, Madame de Tessé, General Knox, General Foy, Léon Dubreuil the physician and the master and friend of Cabanis, &c. I must also notice a small silhouette of Judge Peters of Philadelphi, and a handsome portrait of Lally Tolendal tearing off the crape which covers the bust of his father, whose memory he had just vindicated.

Jules Germain Cloquet, Recollections of the Private Life of General Lafayette, Baldwin and Cradock, London, 1835, p. 177. (Emphasis added.)

I hope you have/had a gorgeous day!

#ask my anything#anon#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#french history#american history#american revolution#polish history#tadeusz kościuszko#france#jules germain cloquet#yes lafayette had an aweful lot of engarvings in his chamber

46 notes

·

View notes

Note

I searched up Adrienne's name and on wikipedia her death date is listed as December 25th. Wasn't her death date the 24th or I misremembered the date right now? 'Cause didn't she died at the same day as Georges' birth, that was Dec. 24th?

Dear @msrandonstuff,

that is a very good question because both dates are sometimes wrongly given, and this matter caused me more than one headache when I first started focusing on the La Fayette’s.

In very short, Adrienne died on her sons 28th birthday, the 24th of December 1807.

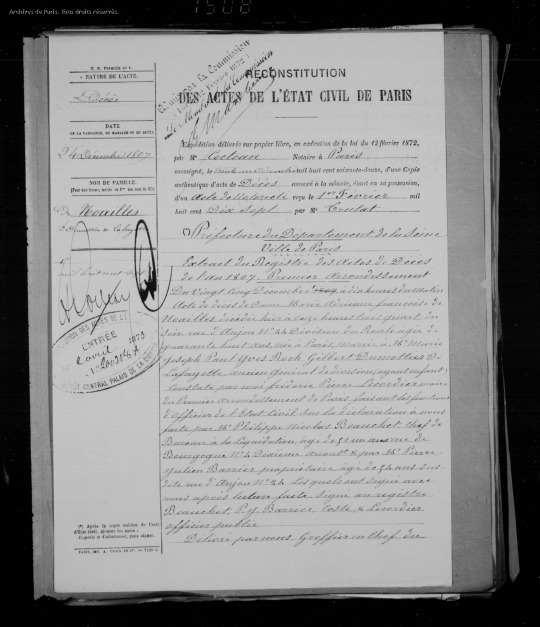

The best proof we have is the official registration of Adrienne’s death. The original document has been destroyed (with many, many more documents) but there is a reconstruction of the document.

In the top left-hand corner, we can read the date of death as “24 Décembre 1807”. In the main text we can read that the death was registered on December 25, but that Adrienne died “hier” meaning “yesterday”.

This official document should be enough to secure the date, but on top of that we also have a letter from La Fayette to his dear friend La Tour-Mauburg, written throughout January of 1808:

Another time she [Adrienne] fell into an ecstasy of joy at the thought of an anniversary dear to our hearts, of the day when, twenty-eight years before, she had given me George. That anniversary was the day of her death.

Mme de Lasteyrie, Life of Madame de Lafayette, L. Techener, London, 1872, p. 414.

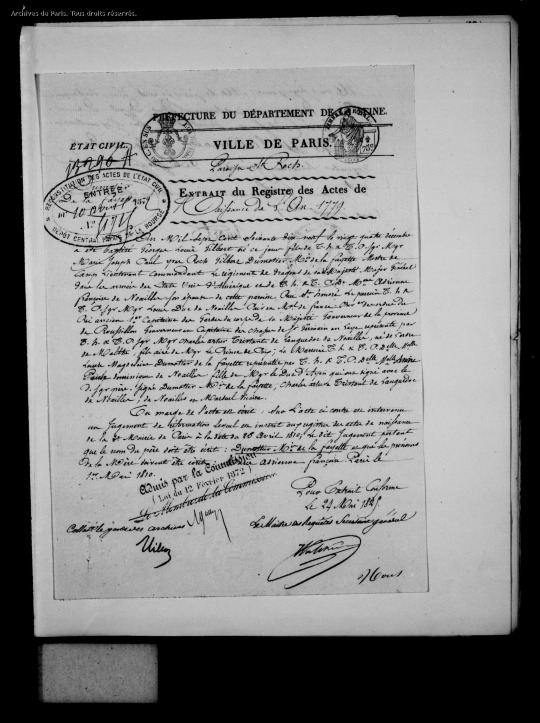

Here is Georges’ Acte de Naissance to verify the date.

We also have a quote from Jules Cloquet Germain’s book. Germain was a close family friend and La Fayette’s physician. He certainly knew when Adrienne died.

She was a model of heroism, and likewise of every virtue. During her captivity and her misfortunes, her blood imbibed the poison which, after protracted sufferings, terminated her existence on the 24th December, 1807.

Jules Germain Cloquet, Recollections of the Private Life of General Lafayette, Baldwin and Cradock, London, 1835, p. 211.

You see, we have official documentation and the accounts from close family members. The only accounts that differ slightly, is from Adrienne’s sister Pauline. Her Memoirs suggest at one point the 25th (technically the 26th, because Pauline says that Adrienne died fifteen minutes past midnight) and a few pages later it reads as if Adrienne died on the 24th.

So why all this confusion? First if all, the English Wikipedia entry that you mentioned is the only one to give the 25th as the day she died. The French, Spanish and Simple English version for example all cite the 24th. In this case, it probably was just a mistake, a typo or something along the line. We see something similar in one of the earliest and most readily available English translations of Life of Madame de Lafayette. Here, Georges’ birthday is given as the 23rd of December 1779 while the French original clearly states the 24th. In other words, mistakes, in the process of translating and in the process of printing, do happen. Another problem is, that many sources give Adrienne’s day of death simply as “Christmas” without a specific date. Different cultures celebrate Christmas on different days and even within the same culture there may be different practices and/or changes over time.

In France for example, the 25th of December is a public holiday, and more and more families have their main Christmas celebrations on this day while other still celebrate on the more “traditional” 24th. Many families also celebrate on both days and meet with one part of the family on the 24th and with the other on the 25th. In Germany, as another example, the 25th and the 26th are public holidays (the first and the second Christmas day) but most families will have their main celebration and gift-giving on the 24th (that is no public holiday.)

These are my two cents on why there is sometimes confusion but also the answer to when Adrienne actually died. I hope you have/had a gorgeous day!

#ask me anything#msrandonstuff#adrienne de lafayette#adrienne de noailles#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#french history#christmas#1807#1808#letters#quote#georges washington de lafayette#jules germain cloquet#la tour-maubourg#marquise de montague#virginie de lafayette#l'état civil reconstitué

17 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi!! I remember reading somewhere that Lafayette had a good sense of humour, is there any quotes or things he’s said to back this up? Thank you :)

Hello Anon,

yes, La Fayette had an excellent sense of humour - in my opinion at least. Maybe I like his humour so much because his humour is very similar to my own.

La Fayette often joked about himself or his own behaviour - that makes him quite likeable in my eyes.

One such story, which may be more myth than truth, is about an injured La Fayette right after the Battle of Brandywine. The continental doctors used every sort of flat surface to put their patients on, pews, dinner tables, unhinged door … La Fayette was places on what formerly had been a dinner table. When some officers entered the room to check on La Fayette, he asked that they please do not eat him because he was the only edible dish on the table and they looked quite hungry.

When he was taken into custody by the Austrian officers, they accused him of stealing his regiments treasure chest and asked him to hand said chest over. La Fayette, who had of course done no such thing, laughed at the request and thought the whole situation to be generally hilarious … the Austrians, did not share this sentiment.

My favourite story took place shortly prior to La Fayette’s death. La Fayette’s friend and physician Cloquet and his colleague Doctor Guersent wanted to call in some more of their colleagues, maybe some of them had any better ideas how to treat La Fayette. He however declined and as Cloquet did not seem to yield, La Fayette asked why the doctors were so insisted. Guersent said:

We think (…) that we have done what is best in your case; but were there only a single remedy that might escape us, it is our duty to seek it. We wish to restore you as soon as possible to health, for we are responsible for your situation towards your family, your friends , and the French nation, of whom you are the father.

To which La Fayette replied smiling:

Yes, (…) their father (…) on condition that they never follow a syllable of my advice.

Jules Germain Cloquet, Recollections of the Private Life of General Lafayette, Baldwin and Cradock, London, 1835, p. 274-275.

His letters are a never-ending well of hilarious anecdotes and incidents as well - have a look at them yourself and you will certainly find your own favourites. I hope until then that you have/had a great day!

#ask me anything#anon#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#french history#american history#humour#jules germain cloquet#battle of bradywine

31 notes

·

View notes