#civility: a cultural history

Text

“The idea of the woman as a ‘submissive and pretty creature,’ put there to minister to her husband’s comfort and pleasure, is the simplified retrospective version of the Victorian conception of womanhood. In actuality, women were regarded as important socializing agents for their husbands as well as their children. John Ruskin’s 1865 lecture of Queens’ Gardens expressed very well the moral and emotional valuation of women as spiritual guides of their husbands: His intellect is for speculation and invention; his energy for adventure, for war, and for conquest, wherever war is just, wherever conquest is necessary. But the woman’s power is for rule, not for battle – and her intellect is not for invention or creation, but for sweet ordering, arrangement, and decision. (1902–12, 1:111–12)

The suggestion that the woman possessed socializing powers beyond those of the male was quite a radical idea for the mid-nineteenth century. It was one thing to affirm that a woman lacked the talents of a man, but quite a different thing to suggest that she possessed qualities that a man did not. It was this idealization of a woman’s power to be a tempering force in the family that led to the myriad civility rituals intended to ‘protect’ women from ‘danger.’ Even feminist writers, such as George Eliot and Beatrice Potter Webb, who passionately argued for women’s suffrage, were careful to affirm the moral influence of women and the vital role they played in the family.

A culture’s attitude towards sexuality is always noticeable in its courtesy practices. Since courtesy is a practice that involves contact between two or more people it also involves the human body and its subtle language. As soon as an act of courtesy is exchanged between two people there is awareness on the part of both that they have come into personalized contact with each other. A courtesy practice based on deference to propriety and a stiff gravity says as much about its practitioner’s attitude towards sensuality as it does about his or her relationship to morality. There may be a connection between sensual inhibition (or sensual privatism) and formalism.

Certainly, what is kept unstated in conversations (of the verbal and bodily sort) points to what is considered inappropriate, or even shameful. The moral triumph of the Victorian middle class had important consequences on the practice of sexuality. What has come down to us as the ‘prudish’ Victorian attitude to sex was really the attitude of the middle class. The upper and lower classes initially followed their own freer and less shame-imbued codes (Porter and Hall 1995). But even they became influenced by Victorian sexual codes by the end of the nineteenth century. The education of the upper-middle-class and upper-class male became an arduous process, requiring segregation from girls within all-boys’ schools.

Discipline was strict – the goals of these schools were not, as in the French system, to produce intellectuals, but men able to fit in and conform to the standards of ‘gentlemen of breeding.’ Paxman (1998) explains the aristocratic schoolboy attitude (something later imitated in public schools) as a particularly male mentality that fuelled patriarchal dominance:

What the Breed represented was a certain ideal, a carefully selected number of the strengths and weaknesses of the male taken and raised to Platonic heights. They were bold, unreflective and crashingly pragmatic, men you could trust. It has been the misfortune of the English male that, just as he found himself living in a country different to the one he imagined himself to be living in, so the so-called English ideal excluded most of the population from the identity with which they had been born. (177–8)

Building such a restrained character required considerable discipline. Eton’s reputation for forming young men of character was not built without pain: The champion flogger was the Reverend Dr. John Keates, appointed headmaster of Eton in 1809, who beat an average of ten boys each day (excluding his day of rest on Sundays). On 30 June 1832 came his greatest achievement, the thrashing of over eighty of his pupils. At the end of this marathon, the boys stood and cheered him. It says something about the spirit of these places that he was later able to tell some of the school’s old boys of his regret that he hadn’t flogged them more often ... In the circumstances, is it surprising that the products of these schools were skilled at hiding their emotions? (179)

What was also being sought was a sexual ethic that would facilitate and preserve the strength and longevity of the family by restraining the sexual impulse. School sports, for example, were a means of keeping the minds of youth off sensual temptations by exhausting their libidinal urges through tiring physical exertion. Just as importantly, sports taught them fair conduct, discipline, and the understanding and respect of the ‘rules of the game,’ abilities that could be applied to the demanding area of diplomacy and commerce. The civility required of the English in sports – such as cricket – hearkened back to the early Christian values of justice, concern for the dignity and comfort of the other, and the avoidance of taking extreme cruel pleasure in victory.

The English constitutional monarchy and the religious institutions of England helped bring forth a new civility philosophy: the right to enjoy personal liberty could not be achieved in a socially isolated setting; freedom required discipline of the kind acquired through sports such as golf, tennis, and cricket – sports requiring a civil submission to the referee and the ethic of fair play. While it was the objective of the player to win, he was not to do so at all cost nor fail to honour his or her opponents for courageous performances during the play.

Thus, complex rituals of face-saving and ministering to others in victory and defeat made the English of the nineteenth-century world authorities in sports etiquette. It was an educational system that moved Ford Madox Ford (1907) to comment: ‘That a race should have trained itself to such a Spartan repression is none the less worthy of wonder’ (147–8). This high valuation of discipline at the best schools certainly appealed to many upper-middle-class and middle-class families who sent their children to boarding and finishing schools, hoping that they would emerge with good breeding.

Certainly, this separation between parents and children placed in boarding schools created some additional reserve in parent– child relations. The development of an individualistic and disciplined young man or young lady required absence from home; the youth was in the tutelage of teachers who were not kin and less disposed to be informal. It was not surprising that by the late nineteenth century, kissing between fathers and sons had been prohibited because it was considered not manly enough. It was perhaps thought that too much physical affection would undo the discipline that had been instilled through great effort.

Manliness required stoicism, and stoicism required a restraint of the emotions, even when one was experiencing a painful flogging. Paxman (1997) reminds us that social certainty fares better in England than in some other countries because England continued to possess an aristocracy: ‘Once such a master-class existed everyone else knew their place in the pecking order’ (265). And the values of the aristocracy did provide the rising middle classes with rationalizations for stoicism, discipline, and moderation, in sexual as well as domestic matters.

No culture that does not hold the family as an ideal institution will seek to establish repressive sexual mores that prohibit premarital sex. The limitation of sexual experience outside marriage is a tool by which men and women are motivated to accept legalized co-habitation and its accompanying duties. Young men and women who are able to enjoy the emotional and physical rewards of marriage without limiting themselves to one partner may not be motivated to enter a contract meant for life; they certainly might be motivated to prolong their sexual experimentation and delay marriage before committing to it.

So the connection between the rise of the middle-class nuclear family and the restriction of sexuality is profoundly deliberate. So are changes in fashion. Victorian fashion ensured that the entire body of a woman was covered without the accentuation of those parts considered provocative. The ‘hourglass’ figures of Victorian women were constructed to project the image of a sexually modest and morally conscientious gender. Similar standards were imposed on the male; the dressed-up ‘dandy’ was considered a dangerous exhibitionist, an irresponsible social parasite (Yeazell 1991).

This high valuation placed on behavioural and sensual modesty, the precondition for marriage, was evident in the life of Queen Victoria. Unlike Elizabeth I, who had chosen to remain celibate despite her affections for one man, Queen Victoria had contracted a marriage that turned out to be quite affectionate. Prince Albert’s love letters to the queen reveal that they had a very loving relationship. The deep feelings that she held for him drove her into a protracted mourning following his death in 1861.

Her withdrawal from social life left the middle classes in a quandary. What sort of sexual ethic were they to embrace when the queen herself was now celibate? She had already distinguished herself as a strict and efficient queen capable of obtaining extraordinary global success for her country – that she was imitated and respected went without saying. Her withdrawal into dour self-pity had its effects on middle-class attitudes towards sexuality. Her model marriage had acted as a confirmation of the middle-class idealization of marriage and the family.

Her withdrawal now left a vacuum that was quickly filled by a Church that revived the Christian value of sexual moderation and abstinence. Frustrated with the queen’s protracted mourning and withdrawal from public life, the upper classes turned to Prince Edward, the Prince of Wales, for leadership. And he provided it obligingly considering that he loved being in the company of beautiful women, many of them readily available singers and actresses. Using his lifestyle as justification, the upper classes adopted a liberal attitude towards sex, one more in keeping with that of their eighteenth-century predecessors.

Sexual promiscuity in the upper classes was tolerated as long as it was not discussed outside aristocratic circles. As for the lower classes, they also lived relatively free from the sexual restraints of the middle class. In the East End of London, where adolescents slept as many as six or eight to a bed, there were plenty of opportunities for sexual intimacy. Incest was present, and no properly enforced legislation existed against it. The young girls selling matches in Trafalgar Square and around Piccadilly Circus were very often child prostitutes. Certain brothels even specialized in providing young virgins to men.

The Victorian propensity to depict middle-class and aristocratic children in scenes of innocence stood in stark contrast to the lot of lower-class children left free to roam the streets at the mercy of strangers (Walkowitz 1980, Marcus 1966, Mason 1994, Porter and Hall 1995). Fyodor Dostoevsky ([1862] 1955) and Hippolyte Taine ([1863] 1957) were both horrified by the poverty and prostitution they witnessed in the Haymarket sector of London.

Taine wrote: I recall Haymarket and the Strand at evening, where you cannot walk a hundred yards without knocking into twenty streetwalkers; some of them ask you for a glass of gin, others say ‘it’s for my rent, mister.’ The impression is not one of debauchery but of abject, miserable poverty. One is sickened and wounded by this deplorable procession in those monumental streets. (31)

Despite the fact that London had no less than 50,000 prostitutes on the street, summary declarations regarding the Victorian middle-class family and its sexual mores need be tempered by recognitions of exceptions. There were enough deviations from the strict preservation of marriage and the social stigma attached to co-habitation to indicate that many were unpleased with the prudery of their own class (Jackson 1994, Hammerton 1992, Bland 1995, Johnson 1979). Charles Dickens, who supported the morality of his period, left his wife and co-habited with a young actress named Ellen Terman, who, in deference to Dickens’s reputation, agreed to remain virtually invisible.

Mary Ann Evans, a well-known moralist who published under the male pseudonym of George Eliot, lived with a man who was unable to get a divorce. So to say that all middle-class Victorian men and women were hapless sexual partners would be almost like saying that they had managed to extinguish the sexual impulse. Even so, many Victorian men remained ignorant of a woman’s sexual needs. Some men reported in their personal journals that upon hearing their wife have an orgasm for the first time they concluded, with considerable alarm, that she was having a fit; some called in a physician (Hall 1991).

This was not surprising considering that many women were conditioned into believing that a ‘good’ woman distracted her mind to non-sexual thoughts during the act of intercourse in order not to fall into the type of behaviour ascribed to a licentious woman. They certainly had frightening advice from Dr William Acton, who catalogued the many medical ills supposedly caused by sexual desire (1857 [1968]). Moreover, many Victorian husbands would have been sorely worried had they seen their wives actually enjoying sex, for that might have meant that a woman was sexual enough to be attracted to extra-marital adventures.

The ideal that a good woman ‘does not move in bed’ was the unspoken rule in many Victorian families. A man ‘took his pleasure’ from a woman. Many women even considered the sexual act as an unpleasant experience and submitted to it in order to satisfy their husbands’ conjugal ‘rights’ or their mutual need to have children. This double standard originated from the ‘classical’ idea of sexuality which posited that men had a much more active sex drive than women. Nevertheless, a ‘moral’ man was expected to control his sensuality for the sake of ‘gentlemanly conduct’ (Comfort 1967).

Yet, there were also bedrooms where these rules were being ignored and where men and women were constructing a romantic view of marriage that very much rejoined the words of the courtly writers who had advised that periodic abstinence and the development of a mind–heart spiritual affinity could only make sexual union that much better when it did occur. The frequency of sexual activity might have been lower compared with what it is in contemporary times, but there is no guarantee that passion was lacking.

In fact, if one refers to the romantic love stories of the period, one is impressed with the heartfelt sensuality of Victorian love and its ideas of devotion and loyalty. So, ironically enough, paralleling the association of sexuality with shame and moral lassitude was a rise in the idealization of romantic courtship and love. Also paradoxical was the existence of so many prostitutes and brothels in a country in which the integrity of the family was being promoted as a non-negotiable social ethic. That there were so many prostitutes does not indicate how many married middle-class men visited them.

The accusation made against the Victorians that they held a hypocritical double standard does not take into account that there existed different factions with varying sexual mores and thresholds of tolerance – so the practice of looking at the English of the period collectively as ‘the Victorians’ is misleading. One thing is certain: there was concern shown in middle-class circles as to how much vice should be tolerated. The middle-class Victorian matron who was passionately against prostitution and pornography was not hypocritical at all; she was found working on projects that were committed to rescuing ‘fallen women’ from their profession (Mahood 1990). Different social classes faced different problems and turned to different solutions.”

- Benet Davetian, “England and the Victorian Ethic.” in Civility: A Cultural History

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Two Etruscan sarcophagi showing embracing couples.

#ancient history#ancient culture#etruscans#etruscan civilization#ancient art#etruscan art#etruscan history

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Roman Glass Bowl

1st century B.C.

The J. Paul Getty Museum.

#Roman Glass Bowl#1st century B.C.#glass#ancient glass#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#ancient rome#roman history#roman empire#roman art#blue

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

#black history month#black excellence#african american history#black heritage#celebrating black history#black culture#black leaders#civil rights#black achievements#black pride#historical legends#black lives matter#black empowerment#black history 365#trailblazers#black history facts#our history#black history celebration#empowering black voices.#021224

418 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Hanfu · 漢服]China's national Important Cultural Relics Impression Series By Artist @陆曼陀

China Neolithic Period:The Hongshan culture(4700-2900 BC)Relics<玉猪龙/Pig dragon>

China Shang dynasty / Western Zhou dynasty(1200–800 BC) · Shu state Relics < 太阳神鸟金饰/Golden Sun Bird>

China Western Han Dynasty (202 BC – 9 AD)Artifact Relics<长信宫灯/oil lamp in the shape of a kneeling female servant>

After the lamp is lit, the soot enters the base of the palace lantern through the sleeve to achieve the purpose of cleaning the air.

China Eastern Han Dynasty(25–220 AD)Artifact Relics<铜奔马 or the Galloping Horse Treading on a Flying Swallow (馬踏飛燕)>

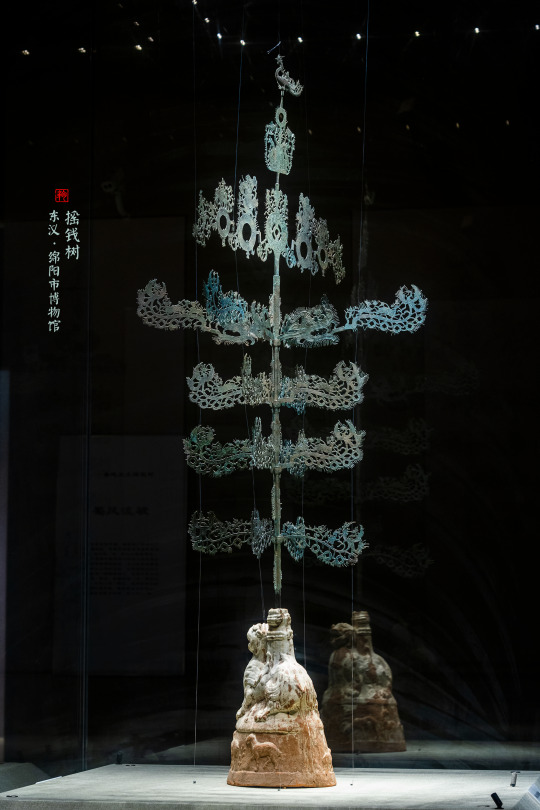

China Eastern Han Dynasty(25–220 AD) Artifact Relics<摇钱树/Money tree (myth)>

China Tang Dynasty(618–907CE) Artifact Relics<女立俑/Female standing figurine >

China Song Dynasty (960–1279) Artifact Relics<汝窑天蓝釉刻花鹅颈瓶/Ru kiln sky blue glaze carved gooseneck bottle>

China Song Dynasty (960–1279) Painting<千里江山图/A Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains>by 王希孟(Wang Ximeng)

China Yuan dynasty (1279–1368) Artifact Relics<霁蓝釉白龙纹梅瓶/Ji blue-glazed plum vase with white dragon pattern>

【Artist:陆曼陀 Social Media】

————————

Twitter:https://twitter.com/LuDanling

Weibo:https://weibo.com/u/2846691957

Post Source:https://weibo.com/2846691957/NzQ9IyzKL

————————

#chinese hanfu#陆曼陀#China history#chinese art#hanfu illustration#hanfu accessories#hanfu#hanfu history#china#chinese#history#chinese aesthetics#culture relic#汉服#漢服#heritage#civilization

427 notes

·

View notes

Text

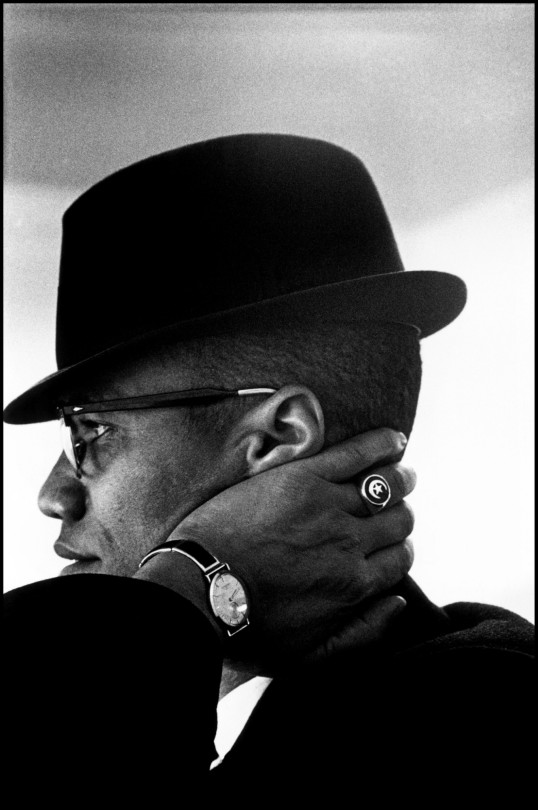

Malcolm X, 1961, Chicago by Eve Arnold.

#1960s#eve arnold#photography#malcolm x#black history#islam#black pride#muslim#civil rights#blm#style#b&w#jazz#hip hop#people#black excellence#culture#60s#fashion#black tumblr#📚

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

#black history#black tumblr#black literature#black excellence#black community#civil rights#blackexcellence365#black history is american history#black americans#americans#equal#equality#black pride#black people#black history month#all black everything#black archives#black culture#black lives matter

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

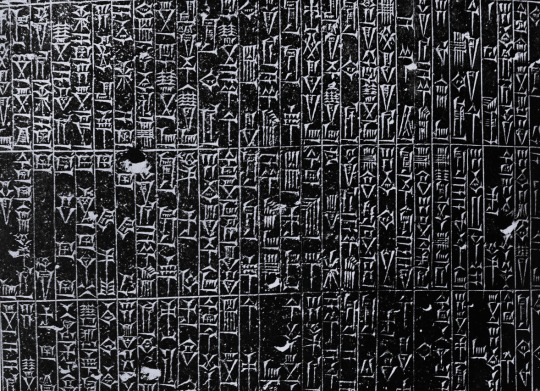

Code of Hammurabi detail

#history#mesopotamia#language#b&w#b&w photography#black and white#ancient#culture#art history#void#image#ancient civilizations

861 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ogrodzieniec Early Medieval Festival, Poland

© Aleksander Gabrysiak

#ogrodzieniec#castle#medieval festival#medieval#middle ages#poland#polska#polishcore#polish culture#europe#european culture#knights#early medieval#slavic#slavcore#western civilization#castle ruins#slavs#history#historical clothing#*

273 notes

·

View notes

Text

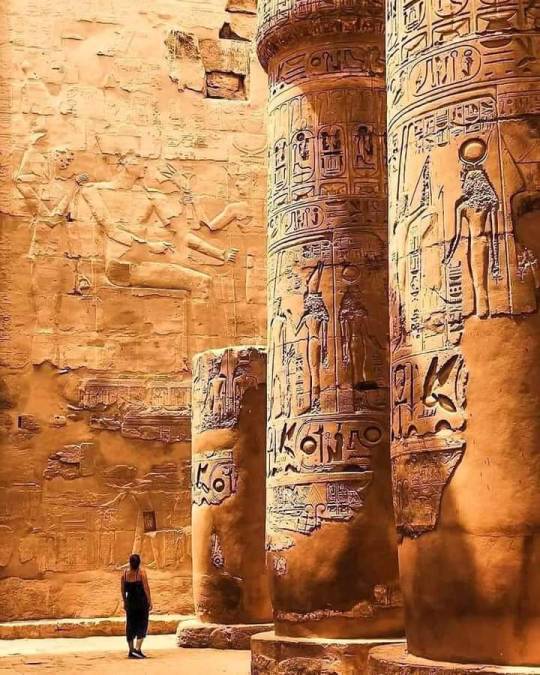

Karnak Temple And Its Gigantic 134 Columns

#ancient egypt#egyptology#history#luxor#culture#egipto#ეგვიპტე मिस्र Єгипет Civilization Egito Ägypten Եգիպտոս Αίγυπτος Egyiptom

270 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Members of the socially active middle class did not lack compassion for the ‘fallen woman.’ A woman seduced by a man who had proposed marriage to her and subsequently broken his promise to her was held in considerable sympathy (Frost 1995). The mid-eighteenth-century Foundling Hospital was already admitting illegitimate babies mothered by women who had good cases regarding the circumstances surrounding their impregnation (Barret-Ducrocq 1991). In The Making of Victorian Sexuality (1994), Michael Mason has calculated that there were nearly 300 institutions (asylums) for prostitutes by the end of the nineteenth century.

Different institutions specialized in different levels of rehabilitation, ranging from those that took in girls who needed to be protected from resorting to prostitution to those that housed unrepentant prostitutes under guard. Yet, the existence of institutions should not in any way give the impression that the Victorian family washed its hands of an errant daughter and sent her away pregnant and destitute. The family’s honour counted as much as the girl’s virtue. In most cases, a stay away from home was arranged and the child subsequently disposed of.

Even the staunch, sexually conservative moralist Dr Acton, who headed a commission investigating prostitution, was careful to distinguish between housemaids who had been seduced by a member of the household staff (or by a member of the employing family) and those women who charged for their services. He recommended that the unfortunate housemaids be employed as wet nurses ([1857] 1968). While from a retrospective position we may find these facilities as little else than places of incarceration that put citizens under the increased control and surveillance of the state, they were, nevertheless, a better alternative than condemnation to utter destitution in the streets.

The moral worry over unwed mothers was related to two positions taken by middle-class Victorians: (1) a woman had to be a virgin upon marriage, and (2) marriage was the ideal state for a woman wishing to be protected from the dangers of society. These two positions, when put together, did not leave much of a middle-class future for either a single mother or a woman who remained single and experimented sexually. Middle-class feminists, for their part, were not struggling for sexual freedom outside marriage as much as they were seeking rights to equal education and work. They continued to uphold the values of the family even while arguing that women did possess sexual needs (Maynard 1993, Russet 1989, Dyhouse 1989).

Those who were part of the ‘sex reform’ movement, although they argued against the idea of a ‘classical sexuality’ (which concurrently rationalized prostitution by stating that men’s and women’s sexual needs differed substantially), remained committed to the idea of a monogamous marriage, albeit one in which sexuality was not repressed (Bland 1995). This fear of the sexually active woman was reflected in the precarious status of the woman of marriage age who had no husband.

In The Spinster and Her Enemies: Feminism and Sexuality 1880–1930 (1985), Sheila Jeffreys describes the limited opportunities available to a woman without a husband. If she was at all attractive she had to live under the suspicious gaze of ‘respectable’ women who wondered if her celibacy was not an excuse for sexual promiscuity. She was either relegated to a position without status in her own family or had to accept a position as a governess or maid. The entry of women in the teaching and nursing professions in the latter part of the century was the first instance in which spinsters were able to meet their own subsistence needs while holding a relatively acceptable position in society.

Some of the Victorian rules of etiquette between men and women in public reveal this penchant for keeping the woman in an asexual role and decreasing the male’s opportunities for making sexual advances on her. They also reveal the extent to which the woman has been idealized as a sensitive being in need of protection. The following rules were embedded in the novels of the period, especially those of Jane Austen: • Walking along the street, the lady always walks along the wall. (This kept the lady away from the danger of the street and away from other men’s physical proximity.)

• Meeting a lady in the street whom a man knows only slightly, he must wait for her to acknowledge him. Only then may he tip his hat to her. A man never speaks to a lady unless she speaks to him first. (This excluded the possibility of a man verbally flirting with a strange woman on the street.)

• If you meet a lady who is a good friend and who indicates that she wishes to talk to you, you must turn and walk with her if you wish to talk to her. You must not keep her standing on the street. (This was to prevent the woman from appearing as if she were habituated to being on the street along with ‘loose’ women.)

• When they are going up a flight of stairs, the man must precede the lady. (This allowed the man to clear the way for the woman and defend her from all possible harm.) • If alone in a carriage, a man does not sit next to a woman unless he is her husband, brother, father, or son. (The privatization of body space was connected to an increasing distancing between men and women.)

• If unmarried and under thirty, a woman is never to be seen without a chaperone in the company of a man. Except for a walk to church or a park in the early morning, she may not walk alone, but should always be accompanied by another lady, a man, or a servant. (The rule existed in order to diminish amorous encounters as well as vulnerability to crime.)

• A woman must never call on a man when she is alone, unless she is consulting that man on a professional or business matter. (Again, the motive is sexual distancing and the exclusion of possibilities of damaging gossip.) • At a public exhibition or concert, the man is expected to go in first in order to find the lady a seat. Leaving a carriage, he is expected to help the lady out while making sure that her skirts do not become soiled.

At a social function, it is always the man who is introduced to the lady and never the other way around – this, because it was considered an honour for a man to meet a woman who was considered the morally superior gender. Nor is a man allowed to cut someone verbally. This privilege is reserved for a woman who feels her dignity has been slighted or a moral imperative transgressed.

The campaign against sexual enjoyment received the support of a considerable number of medical professionals. Themselves of middle-class backgrounds, they accelerated the middle-class project of chastity by publishing articles and books stating that frequent sexual enjoyment led to senility and an early death. Some of them, citing cases from the lunatic asylums, helped rationalize the denial of the natural drives of the body. Ornella Moscucci (1990), in The Science of Woman: Gynaecology and Gender in England, 1800–1929, and Cynthia Eagle Russett (1989), in Sexual Science: The Victorian Construction of Womanhood, have discussed the collusion of the medical sciences in the promotion of an asexual female.

In the 1860s, Dr Isaac Baker Brown even suggested that many female medical problems were related to masturbation. He caused a scandal when he suggested that clitoridectomy be performed on such women. The public outrage was caused not only by the barbarity of his suggestion, but by the fact that many middle-class women took offence to the accusation that they were practising self-gratification in considerable numbers. Some companies even manufactured special corsets for men to wear so that they could not reach their sexual organs without undressing first.

When medical practitioners announced that masturbation would have serious mental and physical consequences for men, some young men castrated themselves. Venereal disease was considered such a shame that many of those who contracted it avoided consulting a doctor. As for young women, many were taught that a single act of intercourse would produce a baby. That some young women committed suicide after succumbing to temptation was understandable. Predictably, sexual instruction of the young was almost non-existent.

There was silence in the schools, and any sexual knowledge was acquired on the sly and shared in hushed voices. This led to a socialization process that taught that sex was a nasty necessity of life, best kept silent. In the upper classes young women servants were sometimes expected to provide sexual initiation to the young master of the house, but in middle-class circles, silence was often maintained regarding anything to do with sexuality. It was even forbidden to refer to a woman’s legs as legs – the word used was ‘underpinnings,’ the same words used for the legs of an armchair.

In many of the conduct books, parents were advised to never speak of sexuality with their children. Such books warned that knowledge would lead to curiosity and curiosity to experimentation. This silence may partially explain Victorian art representations of children and youth in impossibly innocent surroundings and activities. Children were taught to see women as ‘angelic’ beings and to look upon women as they looked upon their sisters and mothers. The tendency in some Victorian literature to compare a beloved mate with the memory of a mother may be connected to this transference of love for the mother onto other women who are then idealized as pure reproductions of the uncorrupted feminine sex.

That much of this literature was male-generated seems to indicate that sex was not a top priority for many ambitions men who were busy building the empire (Hyam 1990). It is understandable that Victorians, such as Hannah More, reacted indignantly to the popularity of a bold, sensual, and seductive French literature. Enough Continental works of literature argued against marital fidelity and in favour of passionate bonds consummated for the sake of passion alone that there arose a fear that English society was in danger of losing its moral centre because of the licentiousness of a growing part of the Continental population.

This fear of sexual compromise was expressed by Tennyson in his epic poems Guinevere and The Passing of Arthur. Tennyson wrote that it was Guinevere’s infidelity towards the king that brought discord to the holy round table and caused a civil war that delivered the realm into the hands of the barbarians. Over-riding sexuality was a profound respect for romantic love. Mainstream Victorian romance novels did not emerge in order to sexually titillate their readers, but to express their authors’ belief in love as the ultimate grace. In his poems, Browning was not shy to suggest that if a person were to meet his or her true love and recoil for any worldly reason he or she would have turned life into a failure.

It is easy to discount these writings as the musings of Romantic poets. But that would be an error, for English literature became a major force in the moulding of an English consciousness and lifestyle. In fact, one of the telling autobiographical writings of the period was Charles Kingsley’s (1877) Letters and Memoirs of His Life. Kingsley confessed to having lived a youth during which he was taken in by sexual proclivity only to awaken later in life and realize that he was beset by doubt. He solved his crisis by giving himself to love with childlike simplicity. And it was a woman who saved him from his disbelief by managing to promise him that eternity was love itself (164).

The Victorian restraint on sexuality and the resulting high valuation of romantic love was a substantial return to the classic notions of chivalry and fin’ amour. By idealizing the woman as a romantic object it became possible to separate passion and virtue from outright expression of sensuality. This Romantic idealization of soul love – the idea that one must live one’s whole life in hopes of meeting that special soul mate – was ingrained in Western society long before the appearance of Romanticism in the nineteenth century. Perhaps influenced by classical writers, Victorian novels glorified love and the exciting passions of attraction, fear of rejection, and the joy of reciprocated love.

A person ‘fell into love,’ which virtually meant falling out of a rational state. And, falling into love, he or she fell out of the body and its animalistic needs and into some realm that was poetic and tender. While marriages of convenience had been tolerated prior to the Victorian restraint of sexuality, there now developed a literature that denigrated arranged marriages because they did not fulfill the highest aspirations of men and women: the joining of two souls in a life-long relationship that had love at its central motive. For the Victorians, the love of home, the strict respect for family and the authority of that family, and the important roles accorded to the mother and father became legitimized and imbued with the cementing ideal of romance.

That the parents rarely exhibited affection towards each other openly in front of their children does not indicate what took place during their private moments together, and we should hesitate before labelling the Romantic movement a hypocritical one. But we can safely say that the circumspection of sex must have had the opposing effect of stimulating the imagination of the young. The ideal of pure love is expressed in the lines of Tennyson’s poem ‘Guinevere’ (1898).

King Arthur meditates over the type of love that prevents discord and corruption: I knew Of no more subtle master under heaven Than is the maiden passion for a maid, Not only to keep down the base of man, But teach high thought, and amiable words And courtliness, and the desire of fame, And love of truth, and all that makes a man. (474–90) The campaign against sensuality affected all walks of life, including art, theatre, and dress. For a painting to include a nude it had to demonstrate that it had a good reason to do so, a reason that went beyond titillating its viewer.

A play that contained a scene referring to sex was considered a threat to public decorum and good manners. The music halls were the only places that brazenly defi ed the Victorian censorship; naturally, attendance at these ribald shows was considered unfit for members of polite society. It was only at the end of the century that some of the avant-garde began attending such shows for distraction, and, even then, they were careful to register moral dismay through nervous giggles. The restrictions placed on overt sexuality and the idealization of romance led to the adoption of circumspect and indirect codes of courtesy between men and woman.

Many young men who took these moral codes seriously must have rationalized in their minds that attraction to a woman meant that they were feeling love for her. The erotic impulse and the romantic feeling became merged for many and love became a rationalization for sexual arousal. Guilt was avoided in this way, for love was considered noble while lust was not. As shown in some of the manners prescribed for men and women in public, the male related to the female in an ambivalent way when it came to being in her proximity without the presence of chaperones.

Being a ‘gentleman’ in the presence of a woman meant not making overt sexual advances, not with a woman of ‘good breeding’ at least. That was the meaning of modern chivalry – the gentleman was expected to protect a lady not only from other men but from his own self. So ingrained became the middle-class notion of ‘gentlemanly conduct’ that it carried over into the twentieth century, and we see it practised in America right through the 1950s before the arrival of the ‘sexual liberation’ movement.

So, what the Victorians made of sexuality is extremely important to our understanding of contemporary relations between men and women in Anglo-American cultures, for the sexual revolutions of the twentieth century were acts of resistance (and undoing) against these previous restraints. Victorian views of sexuality were not restricted to English society but managed to spread to many other countries, including those frequented by colonial missionaries. The preoccupation with ‘danger’ during the nineteenth century had a seminal influence on the manner in which people interacted with one another.

Much of the ‘reserve’ of the Victorians may have been connected to such cautiousness. A person who deviated from the norms of propriety was considered a ‘danger to society.’ For middle-class Victorians seeking propriety, it was a comfort to know that ‘danger’ was being eradicated or, at least, being put out of view. Evasion of the unpleasant and concern for public spaces became connected. Silence stepped in to ‘hush up’ disconcerting realizations. Indeed, anything that did not confirm with their cultural and political ideals might have been considered dangerous by zealous upholders of middle-class values.

The woman who lit a cigarette when most women did not was dangerous. The spinster was dangerous. Street boys were dangerous. Authors writing in favour of free love were dangerous. Meetings without chaperons between young men and women who might become lovers were dangerous. This pervasive obsession with danger was the result of a society attempting to place itself within the boundaries of a set of practices that it could believe in and replay to itself as the best of all possible worlds. Having first restrained their own selves, middle-class Victorians set out to restrain their social environment.”

- Benet Davetian, “England and the Victorian Ethic.” in Civility: A Cultural History

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Three-headed dragon of the underworld, from the Etruscan Tomb of the Infernal Chariot in Sarteano. The colours on this are stunning.

#ancient history#ancient culture#etruscan history#etruscans#etruscan civilization#etruria#wall painting

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Etruscan Bronze Helmet in the Shape of a Wolf’s Head

6th-5th centuries BCE.

#Etruscan Bronze Helmet in the Shape of a Wolf’s Head#6th-5th centuries BCE#Wolf's Head Helmet#Head of a Boar#bronze#bronze helmet#bronze sculpture#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#etruscan history#etruscan art

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

#phyllis yvonne stickney#history#misinformation#slavery#education#legacy#racism#holocaust#atrocity#film#black history#racial inequality#cultural awareness#civil rights#social justice

164 notes

·

View notes

Text

Egyptian

Cuff Bracelets Decorated with Cats

New Kingdom, ca. 1479-1425 B.C.E.

#egyptian art#Egyptian jewelry#ancient egyptian#ancient egypt#ancient art#ancient jewelry#ancient people#egyptian history#egyptian culture#egyptian cat#cat aesthetic#catblr#beautiful cats#cats in art#cat art#cat jewelry#aesthetic#beauty#jewelry#ancient civilizations#art history#aesthetictumblr#tumblraesthetic#tumblrpic#tumblrpictures#tumblr art#tumblrstyle#artists on tumblr#egyptology

336 notes

·

View notes

Text

Malcolm X - 28 May 1963 - Los Angeles . Photo by Robert Flora.

#malcolm x#nation of islam#b&w#civil rights#activism#blm#60s#muslim#1960s#icons#reading#people#black history#photos#photography#black excellence#black tumblr#black pride#culture#robert flora#📸

654 notes

·

View notes