#Black Nationalism

Text

#talkin#tik tok#black nationalism#🇨🇩#the democratic republic of the congo#🇧🇪#belgium#antisemitism#xiandivyne#king leopold

178 notes

·

View notes

Text

Finding out the creator of Kwanzaa tortured two black women, beat them with an electrical chord, put detergent in their mouths.

Wait till you all find out that that corny-ass negro also was a key informant for the FBI during COINTELPRO and he played an instrumental part in taking down the Black Panthers and had multiple Black Panther members killed.

He also founded Kwanzaa on the weird ideology that black Americans have no culture, so he used multiple cultures from, just, other random cultures, other African cultures, but also other cultures to make Kwanzaa. And it was all based on this ideology that black Americans have no culture.

He and his wife were also the leaders of cults.

This is the autobiography of Huey P. Newton, who was the founder of the Black Panthers, and he literally has an entire page where he writes about how bad Karenga was.

I feel like celebrating Kwanzaa and internalizing it as a black American culture or ritual is such a bad thing because Ron Karenga was such a bad person. And celebrating it gives credence to him and his ideologies.

==

So, there are now two rules if you celebrate or legitimize Kwanzaa. If you're going to defend it on the basis of something like, "well, that origin doesn't matter, it's okay to celebrate it anyway," then...

... you can never complain about "cultural appropriation" ever again.

... you can never complain about the origins of Thanksgiving ever again.

This has been my TED Talk.

#Ron Karenga#Kwanzaa#fake holidays#Happy Kwanzaa#holiday of torture#cultural appropriation#black nationalism#cultural nationalism#religion is a mental illness

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

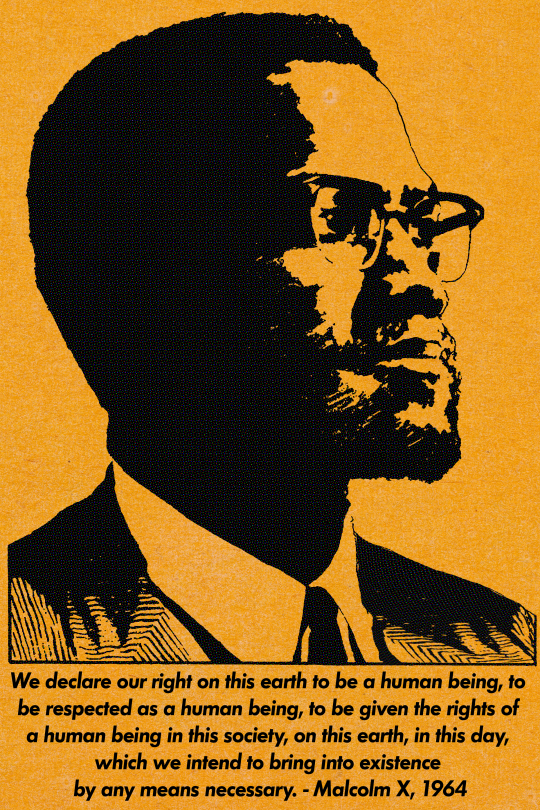

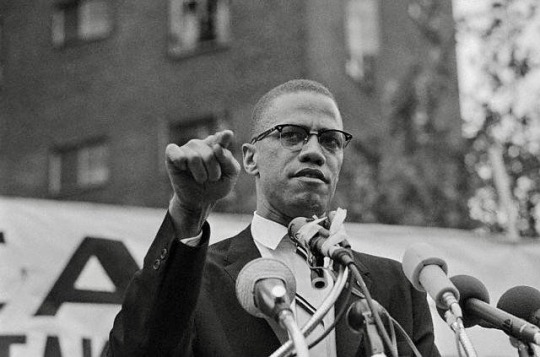

"We declare our right on this earth to be a human being, to be respected as a human being, to be given the rights of a human being in this society, on this earth, in this day, which we intend to bring into existence by any means necessary." - Malcolm X, 1964

#malcolm#X#malcolm X#black panther#black nationalism#mlm#communism#socialism#marxism#marxism-leninism#marxism leninism#marxist#maoism#leninism#mao#maoist#lenin#marx#agitprop#malcomx#huey newton#fred hampton#black panther party#leftism#anti capitalism#MLK#socialist#anti imperialism#ML#black history month

90 notes

·

View notes

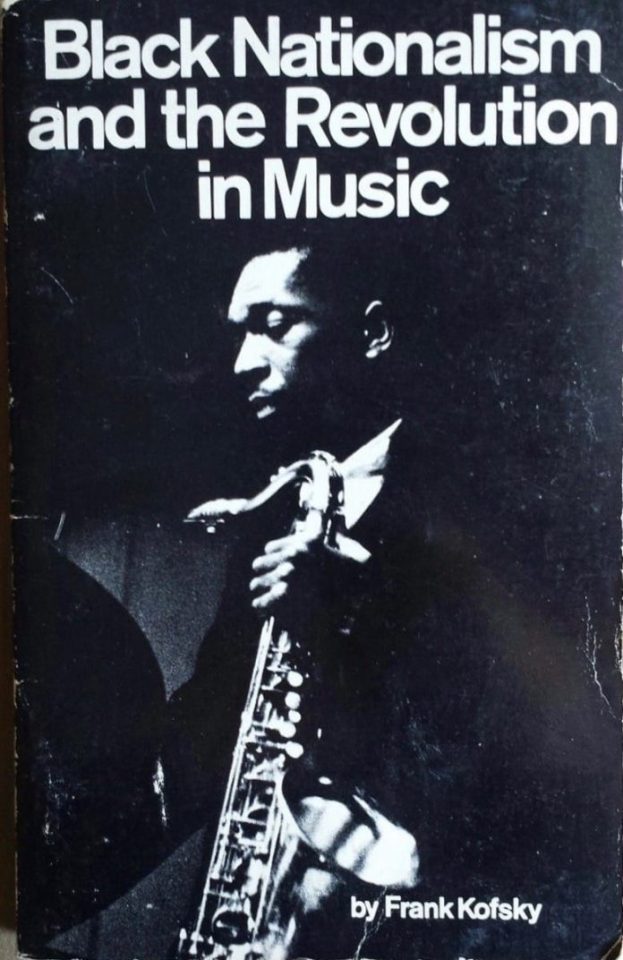

Photo

(via JJ 04/71: Black Nationalism And The Revolution In Music - Jazz Journal)

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jersey Club Black History Month Challenge Day 28

Ok, so today's challenge I want you to know that I'm Ra-Ra from BantuOtaku Your Local(609) Problack(BN), Black Queer Otaku & so much more…🌾🚪🐈⬛🐾🐾

I wanna say Thanks to everyone who Sees Me, It's truly appreciated…👏🏿💐💖

As an growing Blk Anarchist I want you to never forget to always celebrate Yourself, Speak Up, Speak Out & #Look2Bttm!🧱

We're Not free until ANTIBLACKNESS is ADMONISHED!!!😈

Your IMPACT is undeniable & Moves EVERYTHANG!!!🐈⬛🥷🏿

SHARE UR STORIES

SAY UR NAMES

BUILD

REPAIR

PROVIDE MUTUAL AID

READ

GROW

THROW SHADE

STAND UR SQ

FIGHT BACK

& REST N POWER!!!

Further Reading🔗

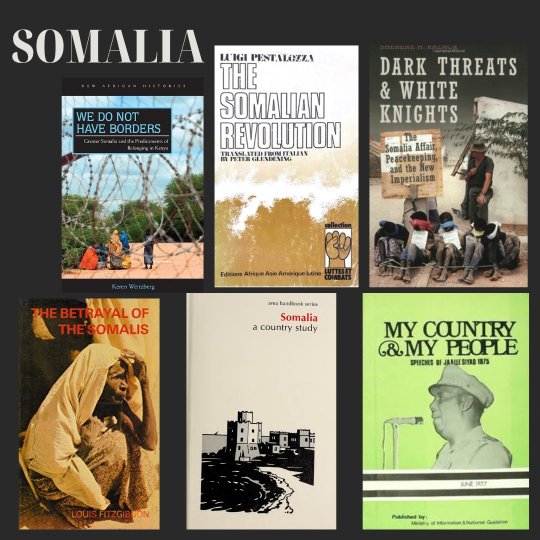

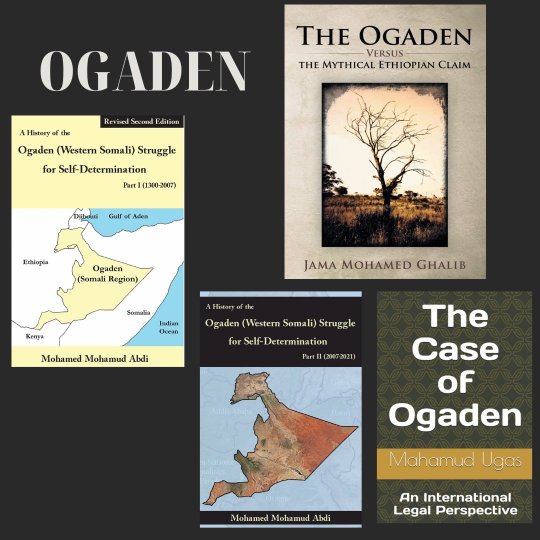

Black Nationalist Bookshelf Pt.1

Black Nationalist Bookshelf Pt.2

Black Nationalist Bookshelf Pt.3

Jersey Club Tech Support⚗️

Reddit

🌑Theme Music🌕

Side B.

DONT FORGET ABOUT YOUR LOVED ONES WHO ARE FREE!!!!!

Some of us are free but aren’t “free” mentally.

You never know you could be saving someone else from self destruction.

Moral of the story: Let your people know you love them and are wishing for their peace and happiness.

CHECK ON YOUR PEOPLE!

PEACE AND LOVE!

Mike Gip

#bantuotaku#jersey club#music#edm#house music#soundcloud#jersey club music#dance music#electronic music#jerseyclub#club music#newark new jersey#newark nj#newark#brick city#club#dance & edm#black history month#black history#black nationalism#pro black#black books#books and reading#books#SoundCloud

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rev. Albert Cleage

#uploads#videos#black history#Albert cleage#black power#1960s#60s#decade: 1960s#naacp#civil rights movement#black economics#black nationalism#black nationalist#black families#black family

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

East African History and Politics.

#nation of gods and earths#supreme mathematics#five percent nation#allah school in mecca#Tigrey#hip hop#5% nation of gods and earths#black women#father allah#black people#black men#east africa#somaliland#Tigray#Ogaden#kenya#pan africanism#Black Nationalism#african spirituality#african diaspora

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Conservaturd Candace Owens And Her Hatred Of The Black Race

She justifies historical White racism. When she says George Floyd was a “horrible human being” she robs him and US, of our humanity. The idea that Blacks are less than human, or two steps from being apes. Other far-fetched ideas can be found in fringe religions. Christian Identity adherents believe that Adam was not the first man but the first WHITE man. They believe Blacks were pre-adamite…

View On WordPress

#antiblackracism#bed wenches#black nationalism#BLACK UNITY#candace owens#george floyd#police brutality

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Moynihan Report met a hostile reception from many liberals and leftists who otherwise supported the goal of progressive welfare reform. By the mid-1960s, a coalition of middle-class liberals and radical leftists had united around the cause of pushing for a more generous and activist expansion of welfare than that envisaged by Johnson's rather tepid Great Society reforms. This coalition included established labor unions, welfare associations, religious charities, civil rights groups, social workers on the liberal spectrum, and, farther to the left, more radical groups such as the Black Nationalist movement, the emerging National Welfare Rights Organization, and feminist activists. Independently, these activists had developed an analysis of racial injustice that responded to precisely the kind of malaise identified by Moynihan, but whose causes they had carefully located outside of the African American community itself, in the enduring nature of structural discrimination. Many of these people responded angrily to the tone of Moynihan's report, accusing him of pandering to existing psychocultural explanations of African American oppression. It is this hostile reaction that is most often recalled in contemporary accounts of the Moynihan Report. And yet, as the historian Marisa Chappell has recently argued in some detail, the anathema surrounding Moynihan's name has tended to obscure the considerable affinity between Moynihan's family wage ideology and leftist and liberal conceptions of welfare reform at the time. The liberal and left coalition for welfare reform may have quibbled with the causes of African American disadvantage adduced by Moynihan, yet they were in fundamental agreement that any long-term solution to racism would therefore require an effort to restore the African American family and the place of men within it.

This consensus reached across the spectrum of liberal and left participants in the welfare reform movement. Reformist civil rights leaders such as Martin Luther King were sympathetic to the findings of the report, while Black Muslim and Black Nationalist leaders were in frank agreement with its suggestions of pathological matriarchy and male castration. But even those on the radical labor left were receptive to Moynihan's arguments. A few years after the publication of Moynihan's report, a new kind of labor activism would erupt on Detroit's auto plants as African American workers, both men and women, adopted strike tactics outside the wage bargaining framework of the New Deal labor unions. Brought together under the umbrella of the League of Revolutionary Black Workers in 1969, these unions openly repudiated the reformist and assimilationist methods of civil rights activism on the one hand and the white New Deal labor unions on the other. But they were by no means hostile to the family wage arguments proffered by Moynihan; indeed, even while the first wildcat strikes were initiated by women, the Revolutionary Unions saw the restoration of African American manhood, via an extension of the New Deal family wage to black men, as the ultimate aim of their extralegal activism.

Melinda Cooper, Family Values: Between Neoliberalism and the New Social Conservatism

#feminism#melinda cooper#neoliberalism#league of revolutionary black workers#moynihan#daniel patrick moynihan#martin luther king jr#black nationalism#civil rights#the welfare state

8 notes

·

View notes

Link

"What makes revolutionary nationalism, well, revolutionary? It is the desire to overthrow rather than reform the current political economic system. In the same way that Kwame Ture remarks that a house is not transformed unless all of the pieces of the old structure are replaced, the revolutionary nationalist desires that the capitalist system be completely abolished and replaced by something else. We do not want black capitalism or a so-called 'autonomous economy' unless that economy involves the establishment of a worker’s state and the control of the means of production by the New Afrikan working masses. The cultivation of well-being entails having a structure that abolishes all barriers to obtain the materials necessary for that cultivation. Capitalism, a system where there is a class who controls the productive forces and benefit from the accumulation of wealth through the appropriation of surplus-value, makes it so that there will always be a battle between the haves and have-nots. Revolutionary nationalism calls for an end to domination of man by man, and it doesn’t matter if this domination is by the White man or the Black."

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Francesca Block

Published: Jan 15, 2024

In the 1960s, when Clarence Jones was writing speeches for Martin Luther King Jr., he used to joke with the civil rights leader: “You don’t deserve me, man.”

“Why?” King would ask.

“I hear your voice in my head. I hear your voice in perfect pitch,” Jones would respond. “So when I write, I can write words that accurately reflect the way you actually speak.”

King would agree. “Man, you are scary. It’s like you’re right in my head.”

And Jones is still, in his mind, having conversations with his friend, who was assassinated at the age of 39 on a Memphis hotel balcony in 1968. Especially now, as America’s racial climate seems to have worsened, despite the fact that King successfully fought to ensure all Americans are given equal protection under the law, regardless of their skin color. A poll from 2021 shows that 57 percent of U.S. adults view the relations between black and white Americans to be “somewhat” or “very” bad—compared to just 35 percent who felt that way a decade ago.

Jones knows exactly what King would have felt about that. He says it out loud, and directs it to his late mentor: “Martin, I’m pissed off at you. I’m angry at you. We should have been more protective of you. We need you. You wouldn’t permit what’s going on if you were here.

“We are trying to save the soul of America.”

[ Jones, behind Martin Luther King Jr. in 1963, wrote: “I saw history unfold in a way no one else could have. Behind the scenes.” ]

I spoke to Jones, 93, two weeks ago as he sat on a beige couch in the humble second-floor apartment in Palo Alto, California, that he shares with his wife. A black-and-white close-up of King sits directly above his head, almost like a north star.

“Regrettably, some very important parts of his message are not being remembered,” Jones said, referring to King’s belief in “radical nonviolence” and his eagerness to build allies across ethnic lines.

“Put in a more negative way,” he added, King’s messages “have been forgotten.”

Jones was a young, up-and-coming entertainment lawyer when he first met King in February 1960. The preacher had turned up on the doorstep of his California home and tried to convince him to move to Alabama to defend him from a tax evasion case. But Jones wasn’t interested.

“Just because some preacher got his hand caught in the cookie jar stealing, that ain’t my problem,” he said in a talk, years later.

But King wasn’t one to give up easily. He invited Jones to attend his sermon at a nearby Baptist church in a well-to-do black neighborhood of Los Angeles. Standing at the pulpit, King spoke to a congregation of over a thousand people, delivering a message that seemed almost tailor-made for Jones.

Jones remembers King talking about how black professionals needed to help their less fortunate “brothers and sisters” in the struggle for equality. He realized, then and there, what an incredible speaker King was, and felt compelled to join his cause.

“Martin Luther King Jr. was the baddest dude I knew in my lifetime,” Jones says.

Jones moved down to Alabama to join King’s legal team. He helped free King of any charges in Alabama, and quickly became one of the leader’s closest confidants, and ultimately, his key speechwriter.

Jones refers to himself and King as “the odd couple,” because, he says, “we were so different.” King was the son of a preacher from a middle-class family in the South. Jones grew up the son of servants, raised by Catholic nuns in foster care in Philadelphia, who he credits with instilling in him “a foundation of self-confidence that was like a piece of steel in my spine.”

He said this confidence propelled him to graduate as the valedictorian from his mixed-race high school just across the border in New Jersey, and then on to Columbia University, where he earned his bachelor’s degree in 1953. After a brief stint in the army, where he was discharged for refusing to sign a pledge stating that he was not a member of the Communist Party, Jones enrolled at the Boston University School of Law, graduating in 1959.

Though Jones was mainly a background figure in the 1960s civil rights movement, it might not have been possible without him. He fundraised for King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference so successfully that Vanity Fair later called him “the moneyman of the movement.” In 1963, when King was in prison, Jones helped smuggle out his notes, stuffing the words King scrawled on old newspapers and toilet paper into his pants and walking out.

Later, he helped string those notes together into King’s famous address, “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” which argued the case for civil disobedience, and was eventually published in every major newspaper in the country.

Jones then wooed enough deep-pocketed donors, including New York’s then-governor Nelson Rockefeller, to raise the bail needed to release King and many other young protesters from jail.

Jones also helped write many of King’s most iconic speeches—“not because Dr. King wasn’t capable of doing it,” Jones emphasized—“but he didn’t have the time.” Jones crafted the opening lines of King’s “I Have a Dream” speech from his D.C. hotel room on the eve of the 1963 March on Washington. In his book, Behind the Dream, he recounts how he penned their shared vision for a better nation onto sheets of yellow, lined, legal notepaper, many of which ended up crumpled on the floor.

But he didn’t write the most famous words: “I Have a Dream”—that was all King, his book notes. “I would deliver four strong walls and he would use his God-given abilities to furnish the place so it felt like home,” Jones writes about their speech-writing dynamic.

The day after he wrote that speech, Jones stood just fifty feet behind King as he delivered it to the hundreds of thousands gathered on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. “I saw history unfold in a way no one else could have,” Jones writes. “Behind the scenes.”

The movement King led with Jones by his side helped achieve school integration, the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

So, when asked if America has made any progress on race, Jones is dumbstruck. “Are you kidding?” he said, with shock in his voice. “Any person who says that to the contrary, any black person who alleges themselves to be a scholar, or any white person who says otherwise, they’re just not telling you the truth.

“Bring back some black person who was alive in 1863, and bring them back today,” he adds. “Have them be a witness.”

But after the death of George Floyd in 2020, 44 percent of black Americans polled said “equality for black people in the U.S. is a little or not at all likely.” And “color blindness”—the once aspirational idea of judging people by their character rather than their skin color, which King famously espoused—has fallen out of fashion. The dominant voices of today’s black rights movement argue that people should be treated differently because of their skin color, to make up for the harms of the past. One of America’s most prominent black thinkers, Ibram X. Kendi, argues that past discrimination can only be remedied by present discrimination.

Jones makes it clear he doesn’t want to live in a society that doesn’t see race. “You don’t want to be blind to color. You want to see color. I want to be very aware of color.”

But, he emphasizes: “I just don’t want to attach any conditions to equality to color.”

He adds that it’s possible to read Kendi’s prize-winning book, Stamped from the Beginning, and “come away believing that America is irredeemably racist, beyond redemption.”

It’s a theory he vehemently disagrees with. “That would violate everything that Martin King and I worked for,” he said. It would mean “it’s not possible for white racist people to change.”

“Well, I am telling you something,” Jones adds. “We have empirical evidence that we changed the country.”

Jones is the first to admit King and his circle didn’t change the country on their own.

“As powerful as he was at moving the country, I tell everybody, there’s no way in hell that he or we would have achieved what we achieved without the coalition support of the American Jewish community.”

Jones especially gives credit to Stanley Levinson, who also advised King and helped write his speeches, and Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, who marched alongside King in Selma, Alabama. He remembers being on the picket lines and talking to Jewish protesters who told him about their own families’ experiences in the Holocaust.

“There would have been no Civil Rights Act of 1964, no Voting Rights Act of 1965, had it not been for the coalition of blacks and Jews that made it happen,” Jones says.

Now, in the wake of Hamas’s October 7 terrorist attack against Israel, Jones said he fears that relations between the Jewish and the black communities in America are beginning to unravel.

He said he has seen how, days after the attack, college students—many of them black—marched on campus, chanting for the death of Israel.

“It pains me today when I hear so-called radical blacks criticizing Israel for getting rid of Hamas. So I say to them, what do you expect them to do?”

He continues: “A black person being antisemitic is literally shooting themselves in the foot.”

Long before October 7, Jones has proudly shown his allegiance to the Jewish people: a gold mezuzah—the small decorative case, which Jews fix to their door frames to bless their homes—is nailed outside his Palo Alto apartment.

“I’m like an old dog who’s just not amenable to new tricks right now,” Jones says. “I have to go on the tricks that I’ve been taught, that got me where I am at 93 years of age. And those old tricks are: you stay with an alliance with the American Jewish community because it’s that alliance that got us this far.

“I am damn sure, at this time in my life, I’m not going to turn my back. This time is more urgent than ever.”

Meanwhile, Jones worries that some of today’s social justice measures have strayed too far from King’s original message. He points to an ethnic studies curriculum for public schools in California, proposed in 2020, which sought to teach K–12 students about the marginalization of black, Hispanic, Native American, and Asian American peoples.

Jones fiercely opposed the new curriculum recommendations, calling them, in a letter to Governor Gavin Newsom, a “perversion of history” that “will inflict great harm on millions of students in our state.” He wrote that the proposed curriculum excluded “the intellectual and moral basis for radical nonviolence advocated by Dr. King” and his colleagues.

“They were promoting black nationalism,” he told me. “They were promoting blackness over excellence.”

California later passed a watered-down version of the curriculum.

At the same time, Jones feels more conflicted about affirmative action, a policy he believes was grounded in “the most genuine, the most beautiful, the most thoughtful” intentions, and that it helped to “accelerate the timetable. . . to truly give black people equal access.”

Even so, he is pragmatic about the Supreme Court’s decision to strike it down last year. “You had to stop the escalator somewhere.”

[ Jones is still working. He released his autobiography, The Last of the Lions, in August, and is now recording the audiobook. ]

In the immediate years after King’s death in 1968, Jones struggled to find a path forward. He was angry and even considered “taking up arms against the government,” which he blamed for allowing King’s death to happen.

For a while, Jones dabbled in politics—serving as a New York State delegate at the 1968 Democratic Convention—and then in media, purchasing a part of the influential black paper New York Amsterdam News. In 1971, he acted as a negotiator on behalf of some of the inmates behind the Attica prison uprising, unsuccessfully trying to seek a peaceful resolution.

But King’s voice—always in his head—eventually steered him back toward his original purpose.

A father of five, Jones lives with his wife, Lin, just a five-minute walk from the Stanford campus where he maintains an affiliation with the Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute. In 2018, Jones co-founded the University of San Francisco’s Institute for Nonviolence and Social Justice to teach the lessons of King and Mahatma Gandhi “in response to the moral emergencies of the twenty-first century.”

He is also the chairman of Spill the Honey, a nonprofit founded in 2012 to honor the legacies of King and Holocaust survivor and Nobel laureate Elie Wiesel. And in August 2023, he released his autobiography, The Last of the Lions, so named because he is possibly the only member of King’s civil rights circle still alive. “There’s an African saying that I often reflect upon when I think about his legacy and my own part in his movement,” Jones writes in his book. “If the surviving lions don’t tell their stories, the hunters will take all the credit.”

Although the eight years he spent with King happened more than half a century ago, Jones told me he now sees his mission as clearly as ever. Asked if he has a message for young black Americans on this Martin Luther King Jr. Day, he doesn’t hesitate.

“Commit yourself irredeemably to the pursuit of personal excellence,” he says emphatically. “Be the very best that you can be. If you do that. . . our color becomes more relevant, because we demonstrate ‘black is beautiful’ not as some slogan, but black is beautiful because of its commitment to personal excellence, which has no color.”

==

What's going on now is what happens when activists and fanatics, such as frauds like Kendi and Nikole Hannah-Jones, construct history curriculum, not actual historians. If they teach the Jewish allyship with the Civil Rights Movements at all, it will be wrapped in conspiracy theory such as "interest convergence."

https://newdiscourses.com/tftw-conspiracy-theory/

This doctrine insists that white people (as the racially privileged group) only take action to expand opportunities for people of color, especially blacks (see also, BIPOC), when it is in their own self-interest to do so, and in which case the result is usually the further entrenchment of racism that is harder to detect and fight. Under interest convergence, every action taken that might ameliorate or lessen racism (see also, antiracism) not only maintains racism, but does so because it was organized in the interests of white people who sought to maintain their power, privilege, and advantage through the intervention.

One of the truly gross and despicable things about frauds like Kendi is that while he pulls every bogus fallacy to assert that nothing has changed - it's a tenet of Critical Race Theory that nothing has changed, racism has only gotten better at hiding itself and becoming more entrenched - his own success blows this conspiracy theory completely out of the water, given how fawning his acolytes are about his wildly overstated wisdom, and the number of white fans he's accumulated who masochistically want to be told how racist they are and how much they hurt black folk every single day.

That's not possible unless racism is both aberrant and socially and culturally unacceptable.

#Clarence B. Jones#Clarence Jones#MLK Day#MLK Jr Day#Martin Luther King Jr#Martin Luther King#Martin Luther King Day#i have a dream#Henry Rogers#Ibram X. Kendi#black nationalism#colorblindness#color blindness#colorblind#color blind#antiracism#antiracism as religion#antisemitism#am yisrael chai#pro palestine#pro hamas#islamic terrorism#israel#palestine#hamas terrorism#hamas war crimes#exterminate hamas#religion is a mental illness

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

America is just as much a colonial power as England ever was. America is just as much a colonial power as France ever was. In fact, America is more so a colonial power than they, because she is a hypocritical colonial power behind it. What is 20th… What do you call second-class citizenship? Why, that’s colonization. Second-class citizenship is nothing but 20th slavery. How you going to tell me you’re a second-class citizen? They don’t have second-class citizenship in any other government on this Earth. They just have slaves and people who are free! Well, this country is a hypocrite! They try and make you think they set you free by calling you a second-class citizen. No, you’re nothing but a 20th century slave.

Just as it took nationalism to remove colonialism from Asia and Africa, it’ll take black nationalism today to remove colonialism from the backs and the minds of twenty-two million Afro-Americans here in this country.

— The Ballot or the Bullet Speech by Malcolm X

2 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Do I see it as realistic within two lifetimes? Yes, you’re talking like 150-160 years with that kind of timeframe. As in, as far from 2022 as 2022 is from the American Civil War. You genuinely think it’s unrealistic for the tides of opinion, identity, national vs. state sovereignty, etc., to change dramatically over that period of time? Hell, I don’t think it would surprise anybody on this sub if a time-traveler came back from the year 2175 and told us al that there is no United States of America anymore at all by that time.

I believe that there is a serious constituency for black national self-determination in the black community right now. Remember that I used ti be a serious leftist, involved in activist communities. One thing that really shocked me about that experience, and that was ultimately the main driving factor behind my turn to the hard right, is realizing just how many black people really do not like white people. More specifically, how for a very large portion of American blacks, being around white people is exhausting. Making your way through the world in a country where everything around you is a constant reminder that this country wasn’t built for you, or with you in mind, and that the cherished founders of the country, pretty much to a man, thought you and your ancestors were some varying level of unwelcome and inferior, grinds a person down. If you really need me to provide you some specific examples of this I can do so, but surely you’ve read the sort of opinion pieces I’m talking about. These aren’t the thoughts of just hoteps and extremists: these are the kinds of things people like Charles Blow says often in the New York Times.

When I was a leftist I would hear my black activist friends talk about this, and I would feel genuinely terrible for them! And I would try and talk to them about what it would take for them to finally feel comfortable and at-home in America. And I realized that the scale of changes that would need to be made to American society would be so, so much deeper and more fundamental than I’d imagined. You would pretty much need to tear the whole thing down to the studs. The type of changes being demanded are things like: “Stop caring if employees show up to work on time.” “Any institution which derived literally any of its revenue from slavery or from an individual who profited from slavery at any point needs to completely remake itself and abandon any ties to its history.” “If someone decides he doesn’t want to be under arrest, police officers should just let him go.” “Expecting kids to solve math problems correctly is racist.” Again, if you want me to track down examples of all of these, it wouldn’t be hard, but I’d be shocked if you haven’t encountered each one of these arguments in one or another prestige publication. These are not fringe arguments at this point.

Barack Obama’s Dreams From My Father has a passage in which he spent three weeks traveling all around Europe, and he says that within the first week he realized that he just didn’t feel any connection to the place at all. He would look at the architecture, the signs everywhere of rich cultural heritage and cherished folkways, and he found it all beautiful and totally unaffecting. “It just wasn’t mine.” And, he’s right, it wasn’t his. He was totally justified in feeling that way. And for an increasing number of black Americans, that’s the conclusion they are reaching about America. “It just isn’t mine.” They’re never going to feel at home here, unless every last bit of its history is scrubbed away and replaced with something unrecognizable and brand-new.

For this reason, I believe that my vision could very well become a reality, because black people will actively try to make it a reality. One of the major reasons I want black people to have a country that truly is built for them is that I’ve heard so many of them say, or imply, that this is what they want. Sure, I’m not going to pretend this is the only reason - far from it. You won’t see me crying, “No, please, don’t go!” However, I think a great deal of “conservatives” will do precisely that. Republicans seem massively more invested in a “multiracial democracy” than progressives do, in many ways. While a large contingent of progressives are saying, “Race matters intimately to me, and identity categories should be able to preserve their own heritage and folkways”, the standard conservative response is, “Why are you so obsessed with race? Don’t you know that we’re all Americans, and we all bleed red?” Conservatives are more likely to go down with the ship of trying to hold this failing experiment together than progressives are, because conservatives are still - bless their hearts - emotionally invested in the American mythos, as reinterpreted post-MLK.

You’ve made a number of remarks to me along the lines of “You seem like so much of an idealist, whereas most white nationalists want a race war, or have resigned themselves to one.” And I just want to genuinely ask: Which white nationalists’ work are you reading? The “National Divorce” idea has been one of the most popular and influential ideas on the Racialist Right for decades at this point. Occidental Quarterly was publishing detailed plans for exactly how to divide the land, repatriate the families of mixed-race people, etc. back in the late 90’s and early 00’s. American Renaissance has published countless detailed arguments in favor of the same ideas. I’m well aware that there are violent and bloodthirsty white nationalists out there, but all the ones I personally know and interact with share my sincere hope and belief that something like what I’m proposing can become a reality.

Hoffmeister25

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

What Was Life Like For Black Americans In The 90s?

youtube

What was it like being black in the 1990s? Black life in the 1990s was at times beautiful, at times scary, and always complicated. The continued rise of black celebrities and culture did not translate into a rise in the black condition. What changed? What stayed the same? In this episode of Lexual Does The 90s, we’ll dive into Black Life in Clinton's America.

#intelexual media#lexual#lexual media#elexusjionde#elexus jionde#90s aesthetic#90s movies#90s#90s music#black american#black history#black americans#Youtube#neosoul#black literature#black movies#black tv shows#riot#police brutality#LA riots#black nationalism#OJ Simpson#american history#clarence thomas#Environmental Racism#naacp#mike tyson#afrocentrism#black history month#magic johnson

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Malcolm X (Malcolm Little, Malik el-Shabazz)

#history#vintage#malcolm x#malcolm little#malik el-shabazz#african american history#african american#black history#civil rights#human rights#activist#writer#black nationalism#islam#pan africanism

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

SWIRCONOMICS (a video about black interracial relationships) by F.D. Signifier

#thought provoking#racism#slavery#black nationalism#black love#black power#fetishization#anti-blackness#double standard#media manipulation#Youtube

1 note

·

View note