#1750s court attire

Text

Blue Silk Court Dress with Silver Embroidery, ca. 1750, British.

Met Museum.

#court dress#court attire#1750s#1750s britain#extant garments#1750s extant garment#1750s dress#1750#blue#silk#silver#womenswear#dress#British#met museum#1750s court attire#embroidery

173 notes

·

View notes

Text

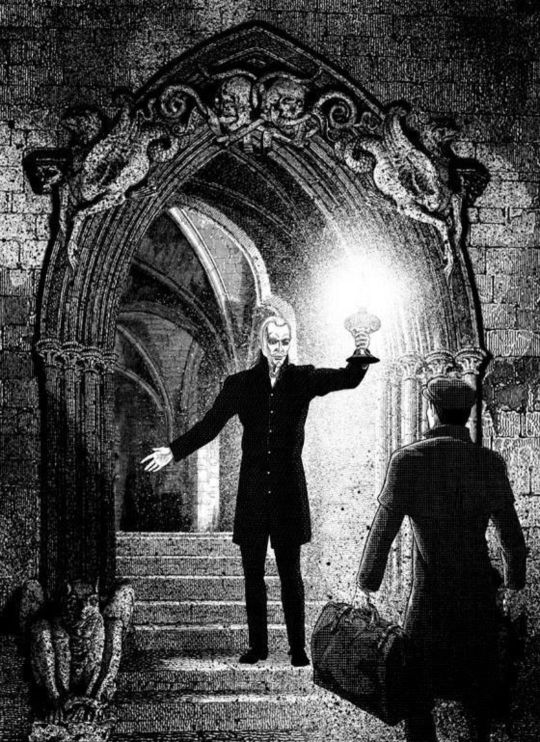

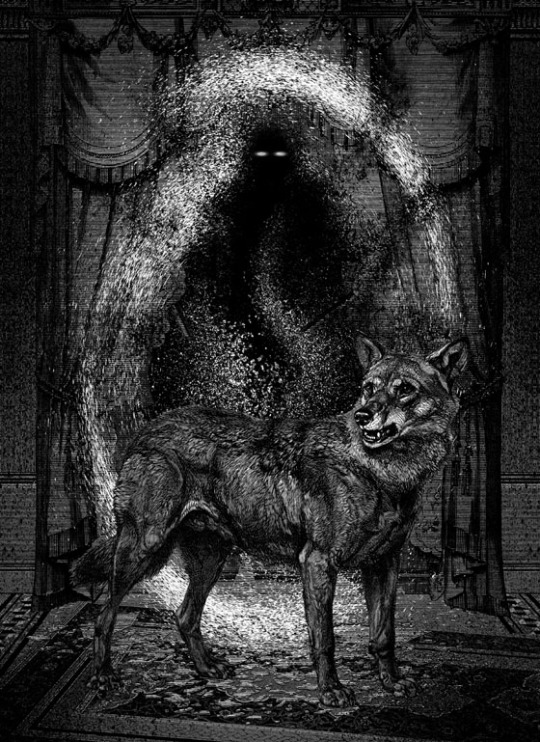

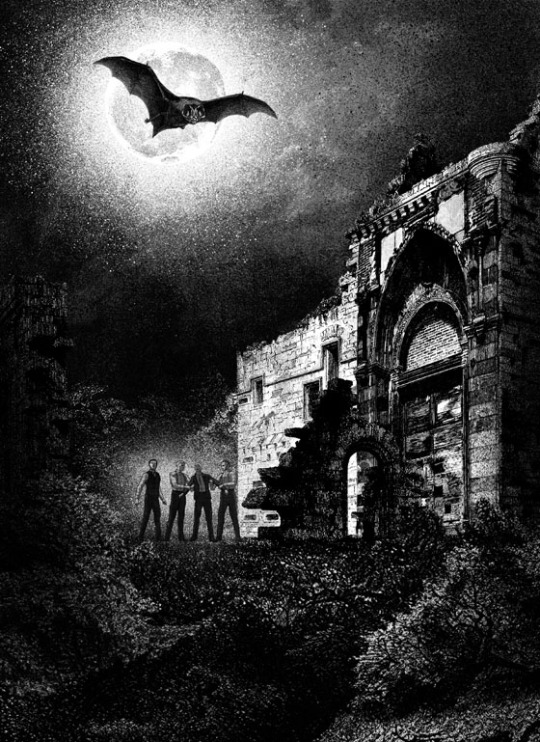

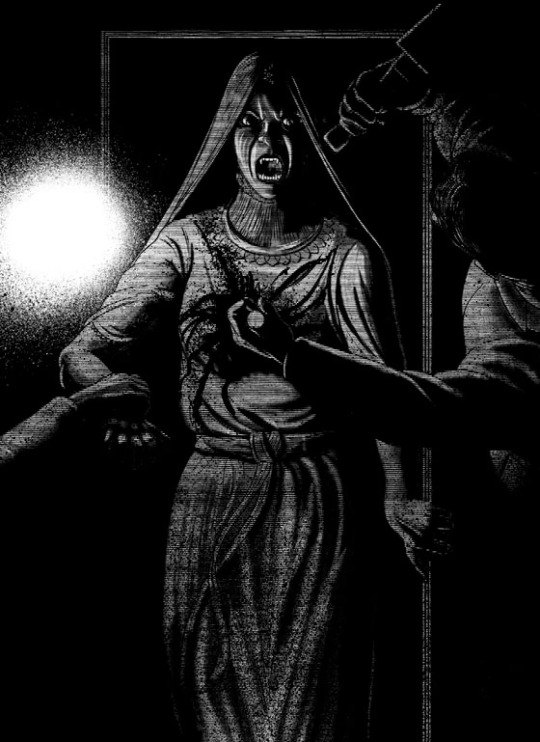

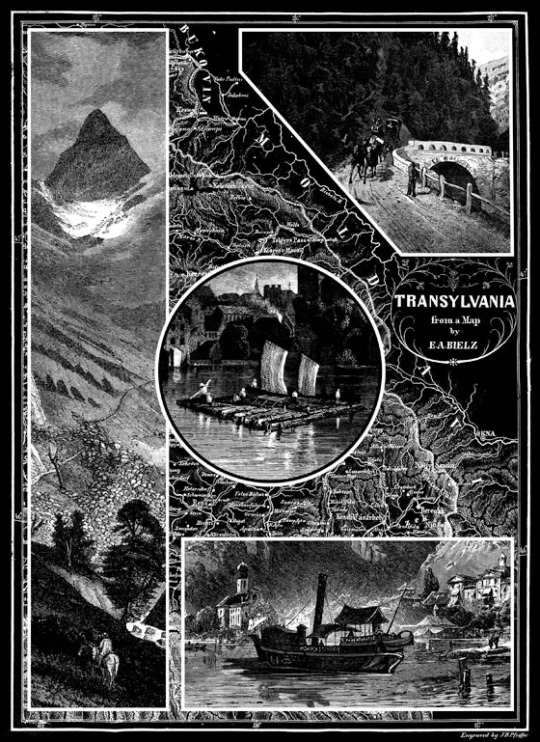

#unhallowedarts - "I spread it over centuries, and time is on my side" - Bram Stoker's Dracula

“You reason well, and your wit is bold, but you are too prejudiced. You do not let your eyes see nor your ears hear, and that which is outside your daily life is not of account to you. Do you not think that there are things which you cannot understand, and yet which are, that some people see things that others cannot? But there are things old and new which must not be contemplated by men's eyes, because they know, or think they know, some things which other men have told them. Ah, it is the fault of our science that it wants to explain all, and if it explain not, then it says there is nothing to explain. But yet we see around us every day the growth of new beliefs, which think themselves new, and which are yet but the old, which pretend to be young, like the fine ladies at the opera.“

(Bram Stoker “Dracula”)

It was a indeed a dark and stormy night, the one in the year without Summer back in 1816, when the Shelleys, Byron and his physician John Polidori sat down to make pop culture history. Cut off from the world, bored witless and full to the brim with laudanum, his lordship challenged the gathered Romantic enfants perdu to lift the burden of ennui with telling ghost stories in the German fashion. And while both Byron and Shelley brought off rather nothing except consuming more narcotics that night, Mary famously began to write “Frankenstein” and Polidori engendered the other treasured dread, the aristocratic, suave, blood sucking king of the undead, the vampire. The myth itself was, of course, centuries old and only two generations before, a downright mass hysteria ran through Europe when repeated cases of vampirism were reported in the Balkans along the Austro-Turkish military border.

Polidori though took the revenant peasant prowling around his former home and sucking the blood of his family, clad him in evening attire and modelled him after the pattern of his employer into a Byronic hero. Polidori’s Lord Ruthven became the ancestor of the 19th and 20th century’s vampires that haunted the imaginations of countless readers and the pages of Gothic literature from the likes of Gogol and Merimee to the infamous penny dreadfuls. One of these featured a creature called “Varney the Vampire” who brought in the fangs and the tell-tale bite marks and Sheridan Le Fanu’s “Carmilla” from 1872 gave the myth the structure of a long dead noble á la Coleridge’s “Christabel” haunting a damsel in distress and a group of heroes bringing the creature to bay with the help of ancient lore and occult paraphernalia. The groundwork was laid and along came Bram Stoker.

As a child, Stoker was bedridden until the age of seven, rose as from the dead after his mysterious illness all of a sudden ceased, became a football star at college, graduated in mathematics and ended up a pen-pusher in Dublin Castle. Not satisfied with his lot, naturally, Stoker changed his career to theatre critic at the Dublin Evening Mail, owned by Sheridan Le Fanu, and attracted the attention of the famous actor Sir Henry Irving with a favourable review, the two became friends and Stoker followed Irving to become his manager. Meanwhile he had won the hand of Florence Balcombe, a celebrated beauty, courted by Stoker’s acquaintance form Trinity College Oscar Wilde as well as a host of other suitors. Stoker would bring these experiences into a literary form in his opus magnum “Dracula” with Sir Henry Irving acting as model for the undead count as Byron did for Polidori 80 years before.

Stoker had never been to Romania, during the 1890s a part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, but he did a thorough research on his subjects that he would add with iconic effects to the imagery of the literary Gothic, from local legends of the 1750s, the late 15th century Wallachian Prince Vlad III. Drăculea who was famed in western European sources for his cruelty and other inspirations from Central Europe like Princess Eleonore von Schwarzenberg, rumoured to be a vampire during her lifetime at the beginning of the 18th century and already an inspiration for German poet Gottfried August Bürger to his poem “Leonore”. Well-known enough known to Stoker and everyone else who read and wrote Gothic literature.

Pitting his research-wise well founded mythical Count and his ancient evil that bears strong resemblances to the feared syphilis as well as despicable moral liberties against the forces of the modern age, trains, the telegraph, typewriters, repeating rifles and established processes and organised teamwork, based on thorough research. Published in 1897, “Dracula” became an instant success and the standard followed to this day, even if Stoker and “Dracula” act only as powers behind the throne of “Urban Fantasy”.

All artwork above is by John Coulthart from his 2018 take on "Dracula" and nicked from his blog linked below

#unhallowedarts#dark art#dark literature#dark academia#gothicliterature#gothic art#victorian gothic#gothic aesthetic#bram stoker#bram stocker's dracula#dracula novel#vampire art

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dear @sanguinarysanguinity, I received your questions for the ask game, but Tumblr was being mean about letting me post my full reply, so I will try again in this format:

7. Favourite historical dressing, uniform, or costume?

Hm, there are several eras of (fashion-)history that appeal to me.

For men's fashion, I think the mid- to later 18th century is particularly pleasing to the eye (think 1750s to late 1780s).

As for women's fashion, I have similar sentiments, with an added love for later 15th century Burgundian fashion and baroque court gowns of the late 17th/early 18th century.

A particular type of clothes that I find interesting is the riding habit, and how for the longest time, it was styled similarly to menswear. Not only do I simply like the look, I enjoy reading about how people, especially men, reacted to these outfits. Some genuinely felt threatened or offended by women donning clothes cut in a similar fashion to and inspired by male attire (and in cases of the late 17th/early 18th century, also men's wigs).

I am fascinated by them, and the societal implications of (upper class, it has to be said) women adapting men's clothes to a) functional sportswear and b) a fashion statement that ruffled quite a few conservative feathers and pushed the boundaries of strictly gendered clothing.

Different eras (1670s and c. later 1770s- early 1780s), but these are both looks.

The sitter is quite famous and has featured a couple of times on my blog; though with the hint of skirts showing below the broad-brimmed, plumed hat cut off, it suddenly grows way harder to tell at first glance whether the person in the allonge wig and lace jabot is a man or a woman.

I do however sometimes dress up as a regency lady, so there's that, too. Not my all-time favourite era of (sartorial) history, but one that it was easy getting into costuming and finding events for even as a beginner.

8. What is the last thing you have read, listened to, or spoken of with historical reference?

I read a slew of ads on used book sites to finally get my hand on 1910s physical copies of Marjorie Bowen's William of Orange triology. Not very popular around these parts, it seems, alas.

I have also tried and failed to get my hands on D. K. Broster's Jacobite triology, with a similar success rate.

9. Favourite historical film?

Depending on the mood, it's either Master and Commander, or Persuasion (the 1995 film; we don't talk about the most recent adaption). Both stand out to me for the attempt at realism in trying to depict the period, the story, and great set and casting.

I do however also love the not as historically faithful Le Roi Danse, which is one of my go-to comfort movies, and Das Boot (1981, not the soulless 2018 series), which will always hold a special place in my heart for having been the first piece of media set in a historical context that I recall having consumed, and which I suspect was the gateway to an interest in naval warfare that at last led me to where I am now- having an almost forgotten admiral of the American Revolutionary War as my blog icon (sorry to everyone who thought that's me! ;)).

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Research - Fashion Design Movements Through Time

Here I am going to look into the era - picking out key elements about the fashion at the time to see how I can apply them to my type design. To mirror this I will also be looking at the times with how type was designed then to - the combination of these things will help me access how to begin my initial sketches.

I will highlight key words that will help when designing.

1600–1650

Characterized by the broad lace or linen collars. Waistlines rose through the period for both men and women. Other notable fashions included full, slashed sleeves and tall or broad hats with brims. For men, hose disappeared in favour of breeches.

The silhouette, which was essentially close to the body with tight sleeves and a low, pointed waist to around 1615, gradually softened and broadened. Sleeves became very full, and in the 1620s and 1630s were often paned or slashed to show the voluminous sleeves of the shirt or chemise beneath.

1650–1700

Characterized by rapid change. The style of this era is known as Baroque. Following the end of the Thirty Years' War and the Restoration of England's Charles II, military influences in men's clothing were replaced by a brief period of decorative exuberance which then sobered into the coat, waistcoat and breeches costume that would reign for the next century and a half. In the normal cycle of fashion, the broad, high-waisted silhouette of the previous period was replaced by a long, lean line with a low waist for both men and women. This period also marked the rise of the periwig as an essential item of men's fashion.

1700–1750

This era is defined as late Baroque/Rococo style. The new fashion trends introduced during this era had a greater impact on society, affecting not only royalty and aristocrats, but also middle and even lower classes. Clothing during this time can be characterised by soft pastels, light, airy, and asymmetrical designs, and playful styles. Wigs remained essential for men and women of substance, and were often white; natural hair was powdered to achieve the fashionable look. The costume of the eighteenth century, if lacking in the refinement and grace of earlier times, was distinctly quaint and picturesque.

1750-1775

Fashion in the years 1750–1775 in European countries and the colonial Americas was characterised by greater abundance, elaboration and intricacy in clothing designs, loved by the Rococo artistic trends of the period. The French and English styles of fashion were very different from one another. French style was defined by elaborate court dress, colourful and rich in decoration, worn by such iconic fashion figures as Marie Antoinette.

After reaching their maximum size in the 1750s, hoop skirts began to reduce in size, but remained being worn with the most formal dresses, and were sometimes replaced with side-hoops, or panniers. Hairstyles were equally elaborate, with tall headdresses the distinctive fashion of the 1770s. For men, waistcoats and breeches of previous decades continued to be fashionable.

English style was defined by simple practical garments, made of inexpensive and durable fabrics, catering to a leisurely outdoor lifestyle. These lifestyles were also portrayed through the differences in portraiture. The French preferred indoor scenes where they could demonstrate their affinity for luxury in dress and lifestyle. The English, on the other hand, were more "egalitarian" in tastes, thus their portraits tended to depict the sitter in outdoor scenes and pastoral attire.

1775–1795

Fashion in the twenty years between 1775 and 1795 in Western culture became simpler and less elaborate. These changes were a result of emerging modern ideals of selfhood, the declining fashionability of highly elaborate Rococo styles, and the widespread embrace of the rationalistic or "classical" ideals of Enlightenment philosophies.

1795–1820

Fashion in the period 1795–1820 in European and European-influenced countries saw the final triumph of undress or informal styles over the brocades, lace, periwigs and powder of the earlier 18th century. In the aftermath of the French Revolution, no one wanted to appear to be a member of the French aristocracy, and people began using clothing more as a form of individual expression of the true self than as a pure indication of social status. As a result, the shifts that occurred in fashion at the turn of the 19th century granted the opportunity to present new public identities that also provided insights into their private selves. Katherine Aaslestad indicates how "fashion, embodying new social values, emerged as a key site of confrontation between tradition and change."

For women's dress, the day-to-day outfit of the skirt and jacket style were practical and tactful, recalling the working-class woman. Women's fashions followed classical ideals, and stiffly boned stays were abandoned in favor of softer, less boned corsets. This natural figure was emphasized by being able to see the body beneath the clothing. Visible breasts were part of this classical look, and some characterised the breasts in fashion as solely aesthetic and sexual.

This era of British history is known as the Regency period, marked by the regency between the reigns of George III and George IV. But the broadest definition of the period, characterized by trends in fashion, architecture, culture, and politics, begins with the French Revolution of 1789 and ends with Queen Victoria's 1837 accession. The names of popular people who lived in this time are still famous: Napoleon and Josephine, Juliette Récamier, Jane Austen, Percy Bysshe Shelley, Lord Byron, Beau Brummell, Lady Emma Hamilton, Queen Louise of Prussiaand her husband and many more. Beau Brummell introduced trousers, perfect tailoring, and unadorned, immaculate linen as the ideals of men's fashion.

1820s

During the 1820s in European and European-influenced countries, fashionable women's clothing styles transitioned away from the classically influenced "Empire"/"Regency" styles of c. 1795–1820 (with their relatively unconfining empire silhouette) and re-adopted elements that had been characteristic of most of the 18th century (and were to be characteristic of the remainder of the 19th century), such as full skirts and clearly visible corseting of the natural waist.

The silhouette of men's fashion changed in similar ways: by the mid-1820s coats featured broad shoulders with puffed sleeves, a narrow waist, and full skirts. Trousers were worn for smart day wear, while breeches continued in use at court and in the country.

1830s

1830s fashion in Western and Western-influenced fashion is characterized by an emphasis on breadth, initially at the shoulder and later in the hips, in contrast to the narrower silhouettes that had predominated between 1800 and 1820.

Women's costume featured larger sleeves than were worn in any period before or since, which were accompanied by elaborate hairstyles and large hats.

The final months of the 1830s saw the proliferation of a revolutionary new technology—photography. Hence, the infant industry of photographic portraiture preserved for history a few rare, but invaluable, first images of human beings—and therefore also preserved our earliest, live peek into "fashion in action"—and its impact on everyday life and society as a whole.

1840s

1840s fashion in European and European-influenced clothing is characterized by a narrow, natural shoulder line following the exaggerated puffed sleeves of the later 1820s and 1830s. The narrower shoulder was accompanied by a lower waistline for both men and women.

Shoulders were narrow and sloping, waists became low and pointed, and sleeve detail migrated from the elbow to the wrists. Where pleated fabric panels had wrapped the bust and shoulders in the previous decade, they now formed a triangle from the shoulder to the waist of day dresses.

Skirts evolved from a conical shape to a bell shape, aided by a new method of attaching the skirts to the bodice using organ or cartridge pleats which cause the skirt to spring out from the waist. Full skirts were achieved mainly through layers of petticoats. The increasing weight and inconvenience of the layers of starched petticoats would lead to the development of the crinoline of the second half of the 1850s.

Sleeves were narrower and fullness dropped from just below the shoulder at the beginning of the decade to the lower arm, leading toward the flared pagoda sleeves of the 1850s and 1860s.

1850s

1850s fashion in Western and Western-influenced clothing is characterized by an increase in the width of women's skirts supported by crinolines or hoops, the mass production of sewing machines, and the beginnings of dress reform. Masculine styles began to originate more in London, while female fashions originated almost exclusively in Paris.

In the 1850s, the domed skirts of the 1840s continued to expand. Skirts were made fuller by means of flounces (deep ruffles), usually in tiers of three, gathered tightly at the top and stiffened with horsehair braid at the bottom.

Early in the decade, bodices of morning dresses featured panels over the shoulder that were gathered into a blunt point at the slightly dropped waist. These bodices generally fastened in back by means of hooks and eyes, but a new fashion for a [jacket] bodice appeared as well, buttoned in front and worn over a chemisette. Wider bell-shaped or pagoda sleeves were worn over false undersleeves or engage antes of cotton or linen, trimmed in lace, broderie anglaise, or other fancy-work. Separate small collars of lace, tatting, or crochet-work were worn with morning dresses, sometimes with a ribbon bow.

1860s

1860s fashion in European and European-influenced countries is characterized by extremely full-skirted women's fashions relying on crinolines and hoops and the emergence of "alternative fashions" under the influence of the Artistic Dress movement.

In men's fashion, the three-piece ditto suit of sack coat, waistcoat, and trousers in the same fabric emerged as a novelty.

By the early 1860s, skirts had reached their ultimate width. After about 1862 the silhouette of the crinoline changed and rather than being bell-shaped it was now flatter at the front and projected out more behind. This large area was largely occupied by all manner of decoration. Puffs and strips could cover much of the skirt. There could be so many flounces that the material of the skirt itself was hardly visible. Lace again became popular and was used all over the dress. Any part of the dress could also be embroidered in silver or gold. This massive construct of a dress required gauze lining to stiffen it, as well as multiple starched petticoats. Even the clothes women would ride horses in received these sorts of embellishments.

1870s

1870s fashion in European and European-influenced clothing is characterised by a gradual return to a narrow silhouette after the full-skirted fashions of the 1850s and 1860s.

By 1870, fullness in the skirt had moved to the rear, where elaborately draped overskirts were held in place by tapes and supported by a bustle. This fashion required an underskirt, which was heavily trimmed with pleats, flounces, rouching, and frills. This fashion was short-lived (though the bustle would return again in the mid-1880s), and was succeeded by a tight-fitting silhouette with fullness as low as the knees: the cuirass bodice, a form-fitting, long-waisted, boned bodice that reached below the hips, and the princess sheath dress. Sleeves were very tight fitting. Square necklines were common.

1880s

1880s fashion in the in Western and Western-influenced countries is characterized by the return of the bustle. The long, lean line of the late 1870s was replaced by a full, curvy silhouette with gradually widening shoulders. Fashionable waists were low and tiny below a full, low bust supported by a corset. The Rational Dress Society was founded in 1881 in reaction to the extremes of fashionable corsetry.

1890s

Fashion in the 1890s in European and European-influenced countries is characterized by long elegant lines, tall collars, and the rise of sportswear. It was an era of great dress reforms led by the invention of the drop-frame safety bicycle, which allowed women the opportunity to ride bicycles more comfortably, and therefore, created the need for appropriate clothing.

Another great influence on women's fashions of this era, particularly among those considered part of the Aesthetic Movement in America, was the political and cultural climate. Because women were taking a more active role in their communities, in the political world, and in society as a whole, their dress reflected this change. The more freedom to experience life outside the home that women of the Gilded Age acquired, the more freedom of movement was experienced in fashions as well. As the emphasis on athleticism influenced a change in garments which allowed for freedom of movement, the emphasis on less rigid gender roles influenced a change in dress which allowed for more self-expression, and a more natural silhouette of women's bodies were revealed.

The 1890s brought the beginnings of a change in how fashion was presented as well. While illustrations still dominated fashion magazines, printed fashion photographs first appeared in French magazine La Mode Pratique in 1892, where they would continue be a weekly feature.

1900s

Fashion in the period 1900–1909 in the Western world continued the severe, long and elegant lines of the late 1890s. Tall, stiff collars characterize the period, as do women's broad hats and full "Gibson Girl" hairstyles. A new, columnar silhouette introduced by the couturiers of Paris late in the decade signalled the approaching abandonment of the corset as an indispensable garment.

With the decline of the bustle, sleeves began to increase in size and the 1830s silhouette of an hourglass shape became popular again. The fashionable silhouette in the early 20th century was that of a confident woman, with full low chest and curvy hips. The "health corset" of this period removed pressure from the abdomen and created an S-curve silhouette.

1910s

Fashion from 1910 to 1919 in the Western world was characterized by a rich and exotic opulence in the first half of the decade in contrast with the somber practicality of garments worn during the Great War. Men's trousers were worn cuffed to ankle-length and creased. Skirts rose from floor length to well above the ankle, women began to bob their hair, and the stage was set for the radical new fashions associated with the Jazz Age of the 1920s.

1920s

Western fashion in the 1920s underwent a modernization. For women, fashion had continued to change away from the extravagant and restrictive styles of the Victorian and Edwardian periods, and towards looser clothing which revealed more of the arms and legs, that had begun at least a decade prior with the rising of hemlines to the ankle and the movement from the S-bend corset to the columnar silhouette of the 1910s. Men also began to wear less formal daily attire and athletic clothing or 'Sportswear' became a part of mainstream fashion for the first time. The 1920s are characterized by two distinct periods of fashion: in the early part of the decade, change was slower, and there was more reluctance to wear the new, revealing popular styles. From 1925, the public more passionately embraced the styles now typically associated with the Roaring Twenties. These styles continued to characterise fashion until the worldwide depression worsened in 1931.

1930–1945

The most characteristic North American fashion trend from the 1930s to 1945 was attention at the shoulder, with butterfly sleeves and banjo sleeves, and exaggerated shoulder pads for both men and women by the 1940s. The period also saw the first widespread use of man-made fibers, especially rayon for dresses and viscose for linings and lingerie, and synthetic nylon stockings. The zipper became widely used. These essentially U.S. developments were echoed, in varying degrees, in Britain and Europe. Suntans (called at the time "sunburns") became fashionable in the early 1930s, along with travel to the resorts along the Mediterranean, in the Bahamas, and on the east coast of Florida where one can acquire a tan, leading to new categories of clothes: white dinner jackets for men and beach pajamas, halter tops, and bare midriffs for women.

1945–1960

Fashion in the years following World War II is characterized by the resurgence of haute couture after the austerity of the war years. Square shoulders and short skirts were replaced by the soft femininity of Christian Dior's "New Look" silhouette, with its sweeping longer skirts, fitted waist, and rounded shoulders, which in turn gave way to an unfitted, structural look in the later 1950s.

1960s

In a decade that broke many traditions, adopted new cultures, and launched a new age of social movements, 1960s fashion had a nonconformist but stylish, trendy touch. Around the middle of the decade, new styles started to emerge from small villages and cities into urban centers, receiving media publicity, influencing haute couture creations of elite designers and the mass-market clothing manufacturers. Examples include the mini skirt, culottes, go-go boots, and more experimental fashions, less often seen on the street, such as curved PVC dresses and other PVC clothes.

Mary Quant popularized the mini skirt, and Jackie Kennedy introduced the pillbox hat; both became extremely popular. False eyelashes were worn by women throughout the 1960s. Hairstyles were a variety of lengths and styles. Psychedelic prints, neon colors, and mismatched patterns were in style.

US First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy arrives in Venezuela, 1961 In the early-to-mid 1960s, London "Modernists" known as Mods influenced male fashion in Britain. Designers were producing clothing more suitable for young adults, leading to an increase in interest and sales. In the late 1960s, the hippie movement also exerted a strong influence on women's clothing styles, including bell-bottom jeans, tie-dye and batik fabrics, as well as paisley prints.

1970s

Fashion in the 1970s was about individuality. In the early 1970s, Vogue proclaimed "There are no rules in the fashion game now" due to overproduction flooding the market with cheap synthetic clothing. Common items included mini skirts, bell-bottoms popularised by hippies, vintage clothing from the 1950s and earlier, and the androgynous glam rock and disco styles that introduced platform shoes, bright colours, glitter, and satin.

New technologies brought advances in production through mass production, higher efficiency, generating higher standards and uniformity. Generally the most famous silhouette of the mid and late 1970s for both genders was that of tight on top and loose on bottom. The 1970s also saw the birth of the indifferent, anti-conformist casual chic approach to fashion, which consisted of sweaters, T-shirts, jeans and sneakers. One notable fashion designer to emerge into the spotlight during this time was Diane von Fürstenberg, who popularised, among other things, the jersey "wrap dress". von Fürstenberg's wrap dress design, which was among the most popular fashion styles of the 1970s, would also be credited as a symbol of women's liberation. The French designer Yves Saint Laurent and the American designer Halston both observed and embraced the changes that were happening in the society, especially the huge growth of women's rights and the youth counterculture. They successfully adapted their design aesthetics to accommodate the changes that the market was aiming for.

1980s

Fashion of the 1980s was characterised by a rejection of 1970s fashion. Punk fashion began as a reaction against both the hippie movement of the past decades and the materialist values of the current decade. The first half of the decade was relatively tame in comparison to the second half, which was when apparel became very bright and vivid in appearance.

Hair in the 1980s was typically big, curly, bouffant and heavily styled. Television shows such as Dynasty helped popularise the high volume bouffant and glamorous image associated with it. Women in the 1980s wore bright, heavy makeup. Everyday fashion in the 1980s consisted of light-coloured lips, dark and thick eyelashes, and pink or red rouge (otherwise known as blush).

The early 1980s witnessed a backlash against the brightly colored disco fashions of the late 1970s in favor of a minimalist approach to fashion, with less emphasis on accessories. In the US and Europe, practicality was considered just as much as aesthetics. In the UK and America, clothing colours were subdued, quiet and basic; varying shades of brown, tan, cream, and orange were common

1990s

Fashion in the 1990s was defined by a return to minimalist fashion, in contrast to the more elaborate and flashy trends of the 1980s. One notable shift was the mainstream adoption of tattoos, body piercings aside from ear piercing and, to a much lesser extent, other forms of body modification such as branding.

In the early 1990s, several late 1980s fashions remained very stylish among both sexes. However, the popularity of grunge and alternative rock music helped bring the simple, unkempt grunge look to the mainstream by 1994. The anti-conformist approach to fashion led to the popularization of the casual chic look that included T-shirts, jeans, hoodies, and sneakers, a trend which continued into the 2000s. Additionally, fashion trends throughout the decade recycled styles from previous decades, notably the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s.

Due to increased availability of the Internet and satellite television outside the United States, plus the reduction of import tariffs under NAFTA, fashion became more globalised and homogeneous in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

2000s

2000s fashion is often described as being a global mash up, where trends saw the fusion of vintage styles, global and ethnic clothing (e.g. boho), as well as the fashions of numerous music-based subcultures. Hip-hop fashion generally was the most popular among young people of all sexes, followed by the retro inspired indie look later in the decade.

Those usually age 25 and older adopted a dressy casual style which was popular throughout the decade. Globalization also influenced the decade's clothing trends, with the incorporation of Middle Eastern and Asian dress into mainstream European, American and Australasian fashion. Furthermore, eco-friendly and ethical clothing, such as recycled fashions and fake fur, were prominent in the decade.

In the early 2000s, many mid and late 1990s fashions remained fashionable around the globe, while simultaneously introducing newer trends. The later years of the decade saw a large-scale revival of clothing designs primarily from the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s.

2010s

The 2010s were defined by hipster fashion, athleisure, a revival of austerity-era period pieces and alternative fashions, swag-inspired outfits, 1980s-style neon streetwear, and unisex 1990s-style elements influenced by grunge and skater fashions. The later years of the decade witnessed the growing importance in the western world of social media influencers paid to promote fast fashion brands on Pinterest and Instagram.

2020s

The fashions of the 2020s represent a departure from 2010s fashion and a nostalgia (or pseudo-nostalgia) for older aesthetics. They have been largely inspired by styles of the early to mid-2000s, late 1990s, 1980s, 1970s, and 1960s. Early in the decade, The Face remarked on the rapid nostalgia cycle in 2020s fashion: "We’re trapped in what might be called a revival spiral". Popular brands in the United Kingdom, United States, and Australia during this era include Adidas, Nike, New Balance, Globe International, Vans, Kappa, Tommy Hilfiger, Asics, Ellesse, Ralph Lauren, Forever 21, Urban Outfitters, Playboy, and The North Face.

During the 2020s, many companies, including current fashion giants such as Shein and Shekou, have been using social media platforms such as TikTok and Instagram as a marketing tool. Marketing strategies involving third parties, particularly influencers and celebrities, have become prominent promotional tactics. E-commerce platforms such as Depop and Etsy grew by offering vintage, homemade, or resold clothing from individual sellers. Their goal is to promote and support small businesses and the environment instead of major retailers. Thrifting has exploded in popularity in the fashion industry of the 2020s due to it being centered around finding valuable or staple pieces of clothing at a reasonable price.

0 notes

Note

Which was more seen at court? A Court Mantua or a robe de cour?

It’d depends on what court we’re talking about. Let’s remember that court attire was very detailed on what should be worn. So, in English court a mantua would be worn, and in France and the rest of Europe, a robe de cour would be the one.

Even though a court mantua and a robe de cour are practically the same thing, I’d like to point at the main difference between both. Here we go:

The sleeves. The mantua sleeves changes with the fashion (we see cuffs or ruffles of the same fabric of the bodice), while on a robe de cour the sleeves are of many lace ruffles.

English mantua, 1755-1760 // Queen Lovisa Ulrika’s coronation robe from 1751

Closure. The mantua is a front-opening gown, while the robe de cour is back opening.

Court mantua, 1740-45 // Robe de cour of Sofia Magdalena of Sweden, 1766

The train. The court mantua’s train was an evolution of the carefully folded one from the late 17th century mantua. On the other side, the robe de cour’s train was long and simply gathered at the waist, it could also be visible only from the back, or could seem like an overskirt at the front.

Court mantua, 1750s // Wedding gown of Princess Sophia Magdalena of Denmark for her marriage to Crown Prince Gustav of Sweden in 1766

The front. The mantua has a clear square neckline, while the robe de cour has a deep round neckline, sometimes decorated by lace.

English court mantua, 1755-60 // Robe de cour coronation dress of Queen Lovisa Ulrika of Sweden, 1751

#Anonymous#court#court attire#womenswear#robe de cour#court mantua#mantua#france#england#1750s#english court#french court

135 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Small Sword, Jean-Baptiste Oudry, c.1750-1760, Cleveland Museum of Art: Medieval Art

The hilt, pommel, and guard of this sword are richly chiseled in low relief against a stippled gold background with animals (dogs, a stag, ducks) that appear to be adapted from paintings by Jean-Baptiste Oudry (1686–1775). An elegant court sword such as this was an important accessory to a gentleman's attire, yet remained functional—it could be withdrawn for an impromptu duel.

Size: Overall: 105.4 cm (41 1/2 in.); Blade: 87.9 cm (34 5/8 in.); Guard: 7.9 cm (3 1/8 in.)

Medium: steel, gilt and russeted, copper, wood

https://clevelandart.org/art/1916.1094

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

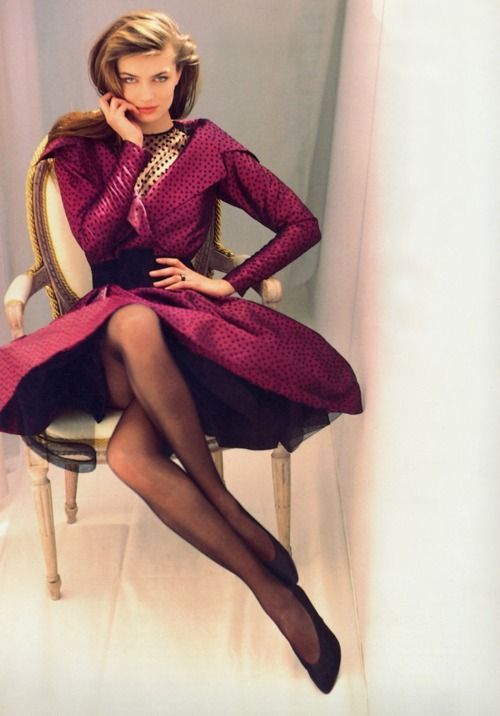

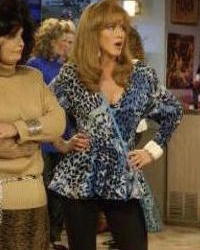

Whereas I have never heard a definite name on Meg Giry’s Masquerade costume, or explanation of what it is supposed to be, it is interesting to see different historical sources to compare it to.

The strongest vibes the costume offers is equestrial ones. The style picks up clues from 18th century riding habits (top), with the tailored “justaucorps” jacket, the lace “jabot” in the neck and the ornate and often military-inspired gold decorations these often had. Similar, the 19th century riding habits kept the fitted, military style in riding jackets, but often paired it with a tilted, veiled top hat - also seen in Meg Giry’s costume.

But the late 19th century also saw a revival in Rococo fashion in general, and variants of the men’s court justaucorps made of rich fabrics and colours, lace jabot and lace engageants. It wasn’t just for fancy dress, but also for riding attires and high fashion, combined with stylish skirts. This can be seen in the two extant jackets in the second row. In the bottom row is also a photo of comedienne and actress Vernona Jarbeau in costume, where the man’s jacket, top hat, tiny draped apron/skirt, exposed legs and high boots in all ways rings a bell to the Meg design.

So we have the mid/late 18th century, and the late 19th century. In addition there’s what was actually in fashion in 1986-87, when “Phantom of the Opera” was designed. Tunics combined with tights was popular, and though here exemplified by a 1998 costume in Friends (photo 8), it’s meant to be a throwback costume back to 1987. The “power suits” for women, with tailored and often dramatic jackets towards tiny skirts, was also a huge trend, and variations of it. Add the endless love for polkadots, and there’s Meg’s costume.

Countess Sophie Marie von Voss, 1746-51, by Antoine Pesne

Riding coat, ca. 1760, The Met

Riding coat, 1750-59, V&A

Evening jacket/bodice, ca. 1890, House of Worth, The Met

Maria Bjørnson’s design

Riding ensemble with jacket and hat, ca. 1905, Morin Blossier, The Met

Ad “Un Certain Soir,” Vogue France August 1987 (Pinterest)

Jennifer Aniston from Friends, 1998 (throwback scene to 1987)

Vernona Jarbeau photographed in costume by Falk, 1885

#meg giry#meg masquerade#costume nerding#from design to costume#phantom of the opera#phantom of the opera design#maria bjørnson

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

Entry 2

The importance of providing real tangible (and intangible) sponsorship benefits and review of your club`s sponsorship packages/proposal.

Sponsorship has evolved in the past 30 years from merely placing a company logo onto the club`s playing attire to businesses able to sponsor all kinds of aspects from the traditional logo on the playing attire to having sponsored posts on the clubs social media pages and even being able to have a business to have the naming rights to the club`s home ground or court. Tangible assets are the quantitative benefits in a sponsorship package. Examples are inclusion in on-site signage, recognition on a property's website, or promotion on social media platforms (Luigi, Macchiaroli & De Mare 2017) Values for these benefits are typically based on quantity of assets, impression rates, and visibility. Intangible benefits are the qualitative benefits unique to a brand, organization, or property (Dees et al 2019). Examples of intangible sponsorship benefits are brand awareness and favorability, openness to new opportunities, and potential limitations in sponsorship experience.

This semester, we are working with our partner VAFA club, the Old Mentonians Football club, with their sponsorship. First we had to review the club`s sponsorship packages and how they used their assets. Our findings were that the Old Mentonians did not have any defined sponsorship packages and were just working with their current sponsors. Through virtual meetings with the club, we worked out that the club was underutilizing their assets. Because the club plays its home game within Mentone Grammar, any possible signage we thought of had to be portable so that it complied with the school`s policy. As the group, we put together potential sponsorship packages that were clear and defined as well as using most of the club’s assets from the clubs playing attire to their social media posts. We used a combination of two methods to find the value in each asset which were the cost-plus method and the Relative Value Method.

Reference List

Dees, W, Gay, C, Popps, N & Jensen, J 2019, ‘Assessing the impact of sponsor asset selection, Intangible rights, and activation on sponsorship effectiveness’, Sport Marketing Quarterly’, vol. 28, no. 2, pp. 91-101, viewed 28th August 2020, ProQuest.

Luigi, D, Macchiaroli, M & De Mare, G 2017, ‘Sponsorship for the sustainability of historical-architectural heritage: Application of a model`s original test finalized to maximize the profitability of private investors’, Sustainability, vol. 9, no. 10, pp. 1750, viewed 27th August 2020, ProQuest

0 notes

Text

Brown Silk Court Suit, 1750-1775, French.

Met Museum.

#met museum#silk#suit#1750#1750s#1770s france#1770s#1760s#1760s france#1750s france#ancien régime#french#France#18th century#court suit#court attire#diss#1750s suit#1760s suit#1770s suit#1750s menswear#1760s menswear#1770s menswear#1750s extant garment#1760s extant garment#1770s extant garment

7 notes

·

View notes