Text

How To Smut And Have Your Editor Thank You For It.

I plead with the mighty writing Gods that this reaches every smut writer (especially the male ones) in the writerverse. Ready? Okay.

Whether you're diving into erotica, romantic escapades, or thrilling adventures with a spicy twist, we've got you covered. Strap in for a journey through the tantalizing realms of smut crafting, where every word is a brushstroke on the canvas of desire.

Unveiling the Law of Erotic Fiction

Let's begin with a golden rule: The Law of Erotic Fiction. Remember Isaac Asimov's Law of Science Fiction? Well, this one's its sultry cousin. Here's the gist: if you can pluck the smut out of your story and still have a compelling tale, you missed the mark. We're talking about integrating smut so seamlessly into your narrative that it becomes the beating heart of your plot.

The Perils of Pandering

Ah, the temptation to sprinkle smut atop a pre-existing storyline like confetti. Resist it! Pandering is the siren song of desperation, luring unsuspecting writers onto the rocks of mediocrity. Don't be that writer. Smut deserves better than being tacked on as an afterthought. It demands its own stage, its own spotlight.

Navigating Plot Shifts

You set sail on the SS Smut, but somewhere along the voyage, your characters mutiny, steering the plot into uncharted waters. Fear not! We've got a litmus test for you. Can you swap out those steamy scenes with tender kisses without capsizing your story? If yes, it's time to hoist a new narrative flag.

Crafting Smut-Driven Stories

Now, let's delve into the nitty-gritty of smut storytelling. Brace yourself for a whirlwind tour of genres, from erotica to bodice-ripping adventures. Each genre has its own GPS, guiding you through the twists and turns of plot and passion.

Erotica: Here, smut isn't just the icing on the cake—it's the whole darn confection. Short, sweet, and to the point, like a decadent truffle melting on the tongue.

Adult Pulp Fiction/Erotic Romance: Consider this a roller-coaster ride through the peaks of passion and the valleys of danger. Every smutty escapade propels your characters deeper into the heart of the adventure.

Romance: Ah, love! Here, smut plays second fiddle to the symphony of emotions. Detailed, yes, but always through rose-colored glasses. After all, it's not just about physicality—it's about the heartstrings.

Bodice Rippers: Enter the realm of forbidden desires and dangerous liaisons. But tread carefully! This genre is a double-edged sword, enticing some readers while repelling others. Know your audience like the back of your hand.

Mastering Descriptive Nuance

Ah, the age-old question: how much is too much? When it comes to smut, the devil's in the details. Female readers crave immersion—every sight, scent, and sensation laid bare before them. Male readers, on the other hand, prefer the silver screen treatment, with just enough detail to fuel their fantasies.

Charting Your Course

Armed with this arsenal of smut-crafting wisdom, you're ready to set sail on your own literary odyssey. Remember: smut isn't just about getting down and dirty—it's about crafting a narrative that leaves readers breathless and begging for more.

So go forth, intrepid writer, and may your smut be as spicy as it is sublime!

#writing tips#creative writing#writing blog#how to write#writing advice#writing tips and tricks#writing fiction#writing help#author tips#author advice#writeblr#writers community#creative writers#writing community#writers on tumblr#writing#writers of tumblr#on writing#writers#writing life#writerscommunity#writing inspiration#writer stuff#novel writing#writer community#writer things#writer problems#resources for writers#helping writers#smut

130 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you have any nicknames? Not stereotypical ones like “honey, sweetie”, but ones that maybe a character won’t like at first but grows to love??

Charcter Nickname Ideas

Hmmm this is actually a tricky one to answer.

Each character will have their own set of cultural backgrounds, quirks, strengths, weaknesses and relationship dynamics, which can all contribute to a nickname.

Here are some common things writers do for nicknames:

Shorten their given name. Mireya becomes Rey. Christopher becomes Chris.

Alter their given name. If you add a “y” sound, it implies the person using the nickname thinks of the character as young or childlike. So Alexa becomes Lexie. William becomes Billy.

Base their nickname on a physical trait. This can be straightforward or ironic. The large man is Tiny. The pretty girl named Honor is Bell/Beauty.

Pick a personality trait. School kids might call your main character Sassy Cassy. The con man might be called Prince Charming because of his smooth-talking skills.

Base their nickname on their profession or an accomplishment. So many characters are called Doc, Prof, or Chairman.

Base it on Monsters: ie. Balrog, Loch, Golen, Orthros, Baal, etc.

Base it on Mythology. Lots of authors have used names from Greek/Roman mythology, and readers have loved it!

Here are two personal examples:

Use initials. My name is Junhui Lee, and those who aren't familar with Asian names struggle to pronoun it correctly. So I just go by "JH"

In Korean culture, (1) people's names are usually three chracters: ie. Jun+hui+Lee and (2) We put surnames in front, not at the back of our names: ie. Lee Junhui, not Junhui Lee. Close friends would address each other as "surname + first character of the given name". So my friends would call me Lee Jun.

A character not liking their nickname

Doesn't necessary mean it has to be a funny nickname. They can dislike it because they somehow feel like only their parents/siblings call them that, or they feel childish, or the tone in which the other person says it is too teasing.

Depends on the origin and meaning behind the nickname. Was it made up by bullies in primary school and its just happened to stick? Was it given to them by their late grandparents? The anme

That said, here are some examples!

Vivienne: Vivvy, Vienne, Viv, Vee

Niamh: Nia, Neeve, Iya

Athena: Ath, Thea

Hazel: Haze, Zelly, Elle

Bloom: Bee, Bloomy, Blommer, Bloo

Coral: Cora, Coralie, Cori, Coral-B

Alaric: Larry, Lars

Ulysses: Ollie, Ulie

Adin: Ade, Ad, Bin, Dinny

Nicolas: Nick, Nico, Nicky

Daniel: Dan, Danny, Dannyboy, Niel

Adreil: Ad, Adri, Riel, El

Louisa: Lulu

+ this list because I've been trying to come up with nicknames for my bloothirsty character...

Steelshot

Crank

Rigs

Skinner

Skull Crusher

Wardon

Zero

Ironclad

Iron Heart

Billy the Butcher

Mr. Blonde

K-6

Hell-Raiser

Harbinger

Finisher

I hope this helps :)

#writing tips#creative writing#writing blog#how to write#writing advice#writing tips and tricks#writing fiction#writing help#author tips#author advice#writeblr#writers community#creative writers#writing community#writers on tumblr#writing#writers of tumblr#on writing#writers#writing life#writerscommunity#writing inspiration#writer stuff#novel writing#writer community#writer things#writer problems#resources for writers#helping writers

263 notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing Mental Health With Compassion

I've gotten a few questions regarding depicting characters with mental health challenges and conditions and I wanted to expand a little more on how to depict these characters with compassion for the real communities represented by these characters.

A little about this guide: this is, as always, coming from a place of love and respect for the writing community and the groups affected by this topic at large. I'm also not coming at this from the outside, I have certain mental illnesses that affect my daily life. With that, I'll say that my perspective may be biased, and as with all writing advice, you should think critically about what is being told to you and how.

So let's get started!

Research

I'm sure we're all tired of hearing the phrase "do your research," but unfortunately it is incredibly important advice. I have a guide that touches on how to do research here, if you need a place to get started.

When researching a mental health condition that we do not experience, we need to do so critically, and most importantly, compassionately. While your characters are not people, they are assigned traits that real people do have, and so your depiction of these traits can have an impact on people who face these conditions themselves.

I've found that reddit is a decent resource for finding threads of people talking about their personal experiences with certain illnesses. For example, bipolar disorder has several subreddits that have very open and candid discussions about bipolar, how it impacts lives, and small things that people who don't have bipolar don't tend to think about.

It's important to note that these spaces are not for you. They are spaces for people to talk about their experiences in a place without judgment or fear or stigma. These are not places for people to give out writing advice. Do NOT flood subreddits for people seeking support with questions that may make others feel like an object to be studied. It's not cool or fair to them for writers to enter their space and start asking questions when they're focused on getting support. Be courteous of the people around you.

Diagnosis

I have the belief that for most stories, a diagnosis for your characters is unnecessary. I have a few reasons for thinking this way.

Firstly, mental health diagnoses are important for treatment, but they're also a giant sign written across your medical documents that says, “I'm crazy!” Doctors may try to remain unbiased when they see mental health diagnoses, but anybody with a diagnosis can say that doctors rarely succeed. This translates to a lot of people never getting diagnoses, never seeking treatment, or refusing to talk about their diagnosis if they do have one.

Secondly, I've seen posts discuss “therapy speak” in fiction, and this is one of those instances where a diagnosis and extensive research may make you vulnerable to it. People don't tend to discuss their diagnoses freely and they certainly don't tend to attribute their behaviors as symptoms.

Finally, this puts you, the writer, into a position where you treat your characters less like people and story devices and more like a list of symptoms and behavioral quirks. First and foremost, your characters serve your story. If they don't feel like people then your characters may fall flat. When it comes to mental illness in characters, the people aspect is the most important part. Mentally ill people are people, not symptoms.

Those are my top three reasons for believing that most characters will never need a specific diagnosis. You will likely never need to depict the difference between bipolar and borderline because the story itself does not need that distinction or to reveal a diagnosis at all. I feel that having a diagnosis in mind for a character has more pitfalls than advantages.

How does treatment work?

Treating mental health conditions may appear in your story. There are a number of ways treatments affect daily life and understanding the levels of care and what those levels treat will help you depict the appropriate settings for your characters.

The levels of care range from minimally restrictive and minimal care to intensive in-patient care in a secure hospital setting.

Regular or semi-regular therapy is considered outpatient care. This is generally the least restrictive. Your characters may or may not also take medications, in which case they may also see a psychiatrist to prescribe those medications. There is a difference between therapists, psychiatrists, and psychologists. Therapists do not prescribe medications, psychiatrists prescribe medications after an evaluation, and psychologists will (sometimes) do both. (I'm US, so this may work differently depending where you are. You should always research the specific setting of your story.) Generally, a person with a mental illness or mental health condition will see both an outpatient therapist and an outpatient psychiatrist for their general continuing care.

Therapists will see their patients anywhere from once in a while as-needed to twice weekly. Psychiatrists will see new patients every few weeks until they report stabilizing results, and then they will move to maintenance check-ins every 90-ish days.

If the patient reports severe symptoms, or worsening symptoms, they will be moved up to more intensive care, also known as IOP (Intensive Outpatient Program). This is usually a group-therapy setting for between 3-7 hours per day between 3-5 days a week. The group-therapy is led by a Licensed Professional Counselor (LPC) or Licensed Professional Social Worker (LPSW). Groups are structured sessions with multiple patients teaching coping mechanisms and focusing on treatment adjustment. IOP’s tend to expect patients to see their own outpatient psychiatrist, but I've encountered programs that have their own in-house psychiatrists.

If the patient still worsens, or is otherwise needing more intensive care, they'll move up to PHP (Partial Hospitalization Program). This can look different per facility, but I've seen them to be more intensive in hours and content than IOP. They also usually have in-house psychiatrists doing diagnostic psychological evaluations. It's very possible for characters with “mild” symptoms to go long periods of time, even most of their lives, without having had a diagnosis. PHP’s tend to need a diagnosis so that they can address specific concerns and help educate the patient on their condition and how it may manifest.

Next step up is residential care. Residential care is a boarding hospital setting. Patients live in the hospital and focus entirely on treatment. Individual programs may differ in what's allowed in, how much contact the patients are allowed to have, and what the treatment focus is. Residential programs are often utilized for addiction recovery. Good residential programs will care about the basis for the addiction, such as underlying mental health issues that the patient may be self-medicating for. Your character may come away with a diagnosis, or they may not. Residential programs aren't exclusively for addictions though, and can be useful for severe behavioral concerns in teenagers or any number of other concerns a patient may have that manifest chronically but do not require intensive inpatient restriction.

Inpatient hospital stays are the highest level of care, and this tends to be what people are talking about when they tell jokes about “grippy socks.” These programs are inside the hospital and patients are highly restricted on what they can and cannot have, they cannot leave unless approved by the hospital staff (the hospital's psychiatrist tends to have the final say), and contact with the outside world is highly regulated. During the days, there are group therapy sessions and activities structured very carefully to maintain routine. Staff will regulate patient hygiene, food and sleep routines, and alone time.

Inpatient hospital programs are controversial among people with mental illness and mental health concerns. I find that they have use, but they are also not an easy or first step to take when dealing with a mental health condition. Patients are not allowed sharp objects, metal objects, shoelaces, cutlery, and pens or pencils. Visitors are not allowed to bring these items in, staff are not allowed these items either. This is for the safety of the patients. Typically, if someone is involuntarily admitted into the inpatient hospital program, it is due to an authority (the hospital staff) deeming the patient as a danger to themselves or others. Whether they came in of their own will (voluntary) or not does not matter in how the program operates. Everyone is treated the same. If someone is an active danger to themselves, then they may be on 24-hour suicide watch. They are not allowed to have any time alone. No, not even for the bathroom, or while sleeping, or during group sessions.

Inpatient Hospital Programs

This is a place of high curiosity for those who have never been admitted into inpatient care, so I'd like to explain a little more in detail how these programs work, why they're controversial, but how they can be useful in certain situations. I do have personal experience in this area, but as always, your mileage may vary.

When admitting, hospital staff are the final say. Not the police. The police hold some sway, but most often, if someone is brought in by the police, they are likely to be admitted. They are only involuntarily admitted when the situation demands: the staff have determined the person to be an imminent danger to themselves or others. This is obviously subjective, and can easily be abused. A good program with decent staff will do everything they can to convince the patient to admit voluntarily if they feel it is necessary, but ultimately if the patient declines and the staff don't feel they can make the clinical argument that admittance is necessary, the patient is free to leave. It should be noted that doctors and clinicians have to worry about possibly losing their licenses to practice. They don't want to fuck around with involuntary admittance if they don't have to, and they don't want potentially dangerous people to walk away.

Once admitted, the patient will have to remove their clothing and put on a set of hospital scrubs. These are mostly made of paper, and most often do not have pockets, but I have seen sets that do have pockets (very handy, tbh). They are not allowed to take anything into the hospital wing except disability-required devices such as glasses, hearing aids, mobility aids, etc. Most programs will require removing piercings, but not all of them, in my experience.

The nurses will also do a physical examination, where they will make note of any open wounds, major scars, tattoos, and other skin abrasions that may be relevant.

The patient will then be led to their bed, where they will receive any approved clothing items from outside, a copy of their patient rights, and a copy of the floor code of conduct and rules, a schedule, and any other administrative information necessary for the program to run efficiently and legally.

Group sessions include group-therapy, activities, coping skills, anger management, anxiety management, and for some reason, karaoke. There is a lot of coloring involved, but only with crayons. A good program will focus heavily on skills and therapeutic activities. Bad programs will phone it in and focus on karaoke and activities. Most hospitals will have a chaplain, and some will include a religious group session. I've never attended these, so I can't speak for them.

Unspoken rules are the hidden pieces of the inpatient programs that patients tend to find out during their first visit. There is no leaving the program until the doctor agrees to it. The doctor will only agree to it if they deem you ready to leave, and you are only ready to leave if you have been compliant to treatment and have seen positive results in the most dangerous symptoms (homicidal or suicidal ideations). Noncompliance can look like: refusing your prescribed medications (which you have the right to do at any time for any reason. That does not mean that there won't be consequences. This is a particularly controversial point.), refusing to attend groups (chapel is not included in this point, but that doesn't mean it's actually discounted. Another controversial point.), violent or disruptive outbursts such as yelling or throwing things, and refusing to sleep or eat at the approved and appointed times. All of this may sound like the hospital is restricting your rights beyond reason, but I've seen the use, and I've seen the abuse. Medications are sometimes necessary, and often patients seriously prefer having medication. Groups are important to a person's treatment, and refusing to go can be a sign of noncompliance or worsening symptoms. If someone is too depressed or anxious to go to group, then they're probably not ready to leave the hospital where the structure is gone and they must self-regulate their treatment. Violent or disruptive outbursts tend to be a sign of worsening symptoms in general, but even the best of us lose our tempers from time to time when put into a highly stressful situation like an inpatient hospital stay. The hospital is supposed to be a place of healing, for many it is. But for many more, it is a place of systematic abuse and restriction.

Discharge processes can be long and arduous and INCREDIBLY stressful for the patient. Oftentimes, they won't know their discharge date until the day of, or perhaps the day before. Though the date can change at any time. The discharge process requires the supervising psychiatrist to meet with the treatment team and then the patient to determine if the patient had progressed enough to be safely discharged. Discharge also requires a set outpatient plan in place, such as a therapy appointment within a week, a psychiatrist visit, or admittance into a lower level of care. This is where social workers are involved. Patients are not allowed access to cell phones or the internet. They cannot make their own appointments with their outpatient care providers without a phone number and phone access. Some floors will have phone access for this reason, others will insist the social worker arrange appointments and discharge plans. Social workers are often incredibly overworked, with several patients on their caseload.

The patient cannot be discharged until the social worker has coordinated the discharge plan to the doctor's approval. Most often, unfortunately, the patient rarely receives regular communication regarding the progress of their discharge. I've been discharged with as much as a day's notice to two hours notice.

Part 2 Coming Soon

This guide got longer than expected! Out of respect for my followers dashboard, I will be cutting it here and adding a Part 2 later on.

If you find that there are more specific questions you'd like answered, or topics you'd like covered, send an ask or reply to this post with what you'd like to see in Part 2.

– Indy

#writing tips#creative writing#writing blog#how to write#writing advice#writing tips and tricks#writing fiction#writing help#author tips#author advice#writeblr#writers community#creative writers#writing community#writers on tumblr#writing#writers of tumblr#on writing#writers#writing life#writerscommunity#writing inspiration#writer stuff#novel writing#writer community#writer things#writer problems#resources for writers#helping writers#writing resources

137 notes

·

View notes

Text

8 Signs your Sequel Needs Work

Sequels, and followup seasons to TV shows, can be very tricky to get right. Most of the time, especially with the onslaught of sequels, remakes, and remake-quels over the past… 15 years? There’s a few stand-outs for sure. I hear Dune Part 2 stuck the landing. Everyone who likes John Wick also likes those sequels. Spiderverse 2 also stuck the landing.

These are less tips and more fundamental pieces of your story that may or may not factor in because every work is different, and this is coming from an audience’s perspective. Maybe some of these will be the flaws you just couldn’t put your finger on before. And, of course, these are all my opinions, for sequels and later seasons that just didn’t work for me.

1. Your vague lore becomes a gimmick

The Force, this mysterious entity that needs no further explanation… is now quantifiable with midichlorians.

In The 100, the little chip that contains the “reincarnation” of the Commanders is now the central plot to their season 6 “invasion of the bodysnatchers” villains.

In The Vampire Diaries, the existence of the “emotion switch” is explicitly disputed as even existing in the earlier seasons, then becomes a very real and physical plot point one can toggle on and off.

I love hard magic systems. I love soft magic systems, too. These two are not evolutions of each other and doing so will ruin your magic system. People fell in love with the hard magic because they liked the rules, the rules made sense, and everything you wrote fit within those rules. Don’t get wacky and suddenly start inventing new rules that break your old ones.

People fell in love with the soft magic because it needed no rules, the magic made sense without overtaking the story or creating plot holes for why it didn’t just save the day. Don’t give your audience everything they never needed to know and impose limitations that didn’t need to be there.

Solving the mystery will never be as satisfying as whatever the reader came up with in their mind. Satisfaction is the death of desire.

2. The established theme becomes un-established

I talked about this point already in this post about theme so the abridged version here: If your story has major themes you’ve set out to explore, like “the dichotomy of good and evil” and you abandon that theme either for a contradictory one, or no theme at all, your sequel will feel less polished and meaningful than its predecessor, because the new story doesn’t have as much (if anything) to say, while the original did.

Jurassic Park is a fantastic, stellar example. First movie is about the folly of human arrogance and the inherent disaster and hubris in thinking one can control forces of nature for superficial gains. The sequels, and then sequel series, never returns to this theme (and also stops remembering that dinosaurs are animals, not generic movie monsters). JP wasn’t just scary because ahhh big scary reptiles. JP was scary because the story is an easily preventable tragedy, and yes the dinosaurs are eating people, but the people only have other people to blame. Dinosaurs are just hungry, frightened animals.

Or, the most obvious example in Pixar’s history: Cars to Cars 2.

3. You focus on the wrong elements based on ‘fan feedback’

We love fans. Fans make us money. Fans do not know what they want out of a sequel. Fans will never know what they want out of a sequel, nor will studios know how to interpret those wants. Ask Star Wars. Heck, ask the last 8 books out of the Percy Jackson universe.

Going back to Cars 2 (and why I loathe the concept of comedic relief characters, truly), Disney saw dollar signs with how popular Mater was, so, logically, they gave fans more Mater. They gave us more car gimmicks, they expanded the lore that no one asked for. They did try to give us new pretty racing venues and new cool characters. The writers really did try, but some random Suit decided a car spy thriller was better and this is what we got.

The elements your sequel focuses on could be points 1 or 2, based on reception. If your audience universally hates a character for legitimate reasons, maybe listen, but if your audience is at war with itself over superficial BS like whether or not she’s a female character, or POC, ignore them and write the character you set out to write. Maybe their arc wasn’t finished yet, and they had a really cool story that never got told.

This could be side-characters, or a specific location/pocket of worldbuilding that really resonated, a romantic subplot, whatever. Point is, careening off your plan without considering the consequences doesn’t usually end well.

4. You don’t focus on the ‘right’ elements

I don’t think anyone out there will happily sit down and enjoy the entirety of Thor: The Dark World. The only reasons I would watch that movie now are because a couple of the jokes are funny, and the whole bit in the middle with Thor and Loki. Why wasn’t this the whole movie? No one cares about the lore, but people really loved Loki, especially when there wasn’t much about him in the MCU at the time, and taking a villain fresh off his big hit with the first Avengers and throwing him in a reluctant “enemy of my enemy” plot for this entire movie would have been amazing.

Loki also refuses to stay dead because he’s too popular, thus we get a cyclical and frustrating arc where he only has development when the producers demand so they can make maximum profit off his character, but back then, in phase 2 world, the mystery around Loki was what made him so compelling and the drama around those two on screen was really good! They bounced so well off each other, they both had very different strengths and perspectives, both had real grievances to air, and in that movie, they *both* lost their mother. It’s not even that it’s a bad sequel, it’s just a plain bad movie.

The movie exists to keep establishing the Infinity Stones with the red one and I can’t remember what the red one does at this point, but it could have so easily done both. The powers that be should have known their strongest elements were Thor and Loki and their relationship, and run with it.

This isn’t “give into the demands of fans who want more Loki” it’s being smart enough to look at your own work and suss out what you think the most intriguing elements are and which have the most room and potential to grow (and also test audiences and beta readers to tell you the ugly truth). Sequels should feel more like natural continuations of the original story, not shameless cash grabs.

5. You walk back character development for ~drama~

As in, characters who got together at the end of book 1 suddenly start fighting because the “will they/won’t they” was the juiciest dynamic of their relationship and you don’t know how to write a compelling, happy couple. Or a character who overcame their snobbery, cowardice, grizzled nature, or phobia suddenly has it again because, again, that was the most compelling part of their character and you don’t know who they are without it.

To be honest, yeah, the buildup of a relationship does tend to be more entertaining in media, but that’s also because solid, respectful, healthy relationships in media are a rarity. Season 1 of Outlander remains the best, in part because of the rapid growth of the main love interest’s relationship. Every season after, they’re already married, already together, and occasionally dealing with baby shenanigans, and it’s them against the world and, yeah, I got bored.

There’s just so much you can do with a freshly established relationship: Those two are a *team* now. The drama and intrigue no longer comes from them against each other, it’s them together against a new antagonist and their different approaches to solving a problem. They can and should still have distinct personalities and perspectives on whatever story you throw them into.

6. It’s the same exact story, just Bigger

I have been sitting on a “how to scale power” post for months now because I’m still not sure on reception but here’s a little bit on what I mean.

Original: Oh no, the big bad guy wants to destroy New York

Sequel: Oh no, the big bad guy wants to destroy the planet

Threequel: Oh no, the big bad guy wants to destroy the galaxy

You knew it wasn’t going to happen the first time, you absolutely know it won’t happen on a bigger scale. Usually, when this happens, plot holes abound. You end up deleting or forgetting about characters’ convenient powers and abilities, deleting or forgetting about established relationships and new ground gained with side characters and entities, and deleting or forgetting about stakes, themes, and actually growing your characters like this isn’t the exact same story, just Bigger.

How many Bond movies are there? Thirty-something? I know some are very, very good and some are not at all good. They’re all Bond movies. People keep watching them because they’re formulaic, but there’s also been seven Bond actors and the movies aren’t one long, continuous, self-referential story about this poor, poor man who has the worst luck in the universe. These sequels aren’t “this but bigger” it’s usually “this, but different”, which is almost always better.

“This, but different now” will demand a different skillset from your hero, different rules to play by, different expectations, and different stakes. It does not just demand your hero learn to punch harder.

Example: Lord Shen from Kung Fu Panda 2 does have more influence than Tai Lung, yes. He’s got a whole city and his backstory is further-reaching, but he’s objectively worse in close combat—so he doesn’t fistfight Po. He has cannons, very dangerous cannons, cannons designed to be so strong that kung fu doesn’t matter. Thus, he’s not necessarily “bigger” he’s just “different” and his whole story demands new perspective.

The differences between Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi are numerous, but the latter relies on “but bigger” and the former went in a whole new direction, while still staying faithful to the themes of the original.

7. It undermines the original by awakening a new problem too soon

I’ve already complained about the mere existence of Heroes of Olympus elsewhere because everything Luke fought and died for only bought that world about a month of peace before the gods came and ripped it all away for More Story.

I’ve also complained that the Star Wars Sequels were always going to spit in the face of a character’s six-movie legacy to bring balance to the Force by just going… nah. Ancient prophecy? Only bought us about 30 years of peace.

Whether it’s too soon, or it’s too closely related to the original, your audience is going to feel a little put-off when they realize how inconsequential this sequel makes the original, particularly in TV shows that run too many seasons and can’t keep upping the ante, like Supernatural.

Kung Fu Panda once again because these two movies are amazing. Shen is completely unrelated to Tai Lung. He’s not threatening the Valley of Peace or Shifu or Oogway or anything the heroes fought for in the original. He’s brand new.

My yearning to see these two on screen together to just watch them verbally spat over both being bratty children disappointed by their parents is unquantifiable. This movie is a damn near perfect sequel. Somebody write me fanfic with these two throwing hands over their drastically different perspectives on kung fu.

8. It’s so divorced from the original that it can barely even be called a sequel

Otherwise known as seasons 5 and 6 of Lost. Otherwise known as: This show was on a sci-fi trajectory and something catastrophic happened to cause a dramatic hairpin turn off that path and into pseudo-biblical territory. Why did it all end in a church? I’m not joking, they did actually abandon The Plan while in a mach 1 nosedive.

I also have a post I’ve been sitting on about how to handle faith in fiction, so I’ll say this: The premise of Lost was the trials and escapades of a group of 48 strangers trying to survive and find rescue off a mysterious island with some creepy, sciency shenanigans going on once they discover that the island isn’t actually uninhabited.

Season 6 is about finding “candidates” to replace the island’s Discount Jesus who serves as the ambassador-protector of the island, who is also immortal until he’s not, and the island becomes a kind of purgatory where they all actually did die in the crash and were just waiting to… die again and go to heaven. Spoiler Alert.

This is also otherwise known as: Oh sh*t, Warner Bros wants more Supernatural? But we wrapped it up so nicely with Sam and Adam in the box with Lucifer. I tried to watch one of those YouTube compilations of Cas’ funny moments because I haven’t seen every episode, and the misery on these actors’ faces as the compilation advanced through the seasons, all the joy and wit sucked from their performances, was just tragic.

I get it. Writers can’t control when the Powers That Be demand More Story so they can run their workhorse into the ground until it stops bleeding money, but if you aren’t controlled by said powers, either take it all back to basics, like Cars 3, or just stop.

—

Sometimes taking your established characters and throwing them into a completely unrecognizable story works, but those unrecongizable stories work that much harder to at least keep the characters' development and progression satisfying and familiar. See this post about timeskips that take generational gaps between the original and the sequel, and still deliver on a satisfying continuation.

TLDR: Sequels are hard and it’s never just one detail that makes them difficult to pull off. They will always be compared to their predecessors, always with the expectations to be as good as or surpass the original, when the original had no such competition. There’s also audience expectations for how they think the story, lore, and relationships should progress. Most faults of sequels, in my opinion, lie in straying too far from the fundamentals of the original without understanding why those fundamentals were so important to the original’s success.

#writing tips#creative writing#writing blog#how to write#writing advice#writing tips and tricks#writing fiction#writing help#author tips#author advice#writeblr#writers community#creative writers#writing community#writers on tumblr#writing#writers of tumblr#on writing#writers#writing life#writerscommunity#writing inspiration#writer stuff#novel writing#writer community#writer things#writer problems#resources for writers#helping writers#writing resources

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

How To Identify Active vs Passive Voice In Your Sentences

To clarify, active voice is when the subject is performing the action, experiencing the emotion, etc. and passive voice is when the subject undergoes the action, emotion, etc. These basically come up in sentence structure as a way to make a character feel like they have more or less agency

The way to identify the difference, or at least the way I’ve used for years, is to put ‘by zombies’ after the verb. If it’s coherent, it’s passive voice, and if it isn’t, it’s active. Let’s use some examples:

“She was killed (by zombies)” -> coherent, passive

“Zombies killed (by zombies) her” -> incoherent, active

And the effect of these techniques in your writing is to make the subject read as though they have more or less agency depending on the situation, even without changing what’s going on in the scene. Neither is necessarily better than the other, it’s all about utilisation in the correct circumstances

Now some longer, Tumblr friendly examples, and you can try and practice identifying active and passive voice if that can help you:

“You kneel before my throne unaware that it was built on lies”

“It may not be that deep, but the ground is soft and I’m ready to dig”

“I hope I make it a little softer here for someone”

“If they won’t match your effort, they don’t want to be in your life”

“God may judge you but his sins outweigh your own”

#writing tips#creative writing#writing blog#how to write#writing advice#writing tips and tricks#writing fiction#writing help#author tips#author advice#writeblr#writers community#creative writers#writing community#writers on tumblr#writing#writers of tumblr#on writing#writers#writing life#writerscommunity#writing inspiration#writer stuff#novel writing#writer community#writer things#writer problems#resources for writers#helping writers#passive voice

156 notes

·

View notes

Text

How to Write Stakes that Aren't Life vs. Death

Writing strong stakes is critical for any story. But a question that often comes up for newer writers is, "How do I create stakes other than life vs. death?" Or essentially, "How do I write stakes that aren't life or death, yet are still effective?"

"Stakes" refer to what your character has to lose, what is at risk in the story. And obviously, potentially losing one's life, is a pretty big risk.

To address the questions, let's first look at why life vs. death stakes are so effective.

I know, it sounds obvious, like common sense even, and you may be rolling your eyes.

But understanding why they almost always work, will help you see how to create other similar stakes.

The thing about death is, it has a finality to it that almost nothing else has.

No one can come back from the dead.

That's it.

Death is the end of the road.

Done.

Gone.

Game over.

. . . Except that unlike "Game over," you can't restart the game.

In storytelling, this is one of the main reasons many of us want to grab life vs. death stakes. Everyone reading the book innately understands this. Death is final, you can't come back from that. It's a "point of no return." It can't be undone.

Great stakes will create a similar effect.

It's not literally life or death. But to some degree, there exists a figurative life-or-death situation.

For example, in The Office, after Michael accidentally hits Meredith with his car, he organizes a fun run on her behalf. Michael is driven by the desire to be liked by others. And after he hits Meredith, people don't like him. (I am simplifying the actual story just a bit.) With the fun run, he's hoping to redeem himself. He wants to be liked (or even admired) by others. To Michael, that hinges on his success with the fun run. If it's a success, people will like him again. If it's a failure, they won't (or they will dislike him even more).

There are seemingly only two outcomes: Success = liked. Failure = (forever) disliked.

From Michael's perspective, he can't have both.

Whichever path the fun run takes, the other path "dies."

You can't go back in time and change the outcome of the fun run.

It's final.

End of the road.

Done.

Gone.

The situation also, to some degree, feels like figurative life or death to Michael. He's driven to be liked, and that makes him feel alive. If he's disliked, it feels like "death." It mars him psychologically, and he feels like he can't come back from that. It feels like the end of the road.

The Office is not a high-stakes story (which is one of the reasons I'm using it), but it still has effective stakes that convey why what's happening (the fun run) matters (liked vs. disliked), which is something all good stakes do.

This example also shows two components related to crafting effective stakes: plot and character.

Let's dig a bit deeper into each.

One of Two Paths Forward

If you've been following me for a while, you may know that I like to define stakes as potential consequences. It's what could happen, if a condition is met. As such, any stake should be able to fit into an "If . . . then . . ." sentence.

If the fun run is a success, then Michael will be liked.

If the fun run is a failure, then Michael will be disliked.

Others may argue the stake is only what is at risk in the story--and that's fair.

But notice when we lay out potential consequences, they convey (directly or indirectly) what is at risk. In the example sentences above, we see that Michael's popularity (or the lack thereof) is what is at risk.

Potential consequences convey what will happen if a specific outcome is reached. And this lays out at least two possible paths forward.

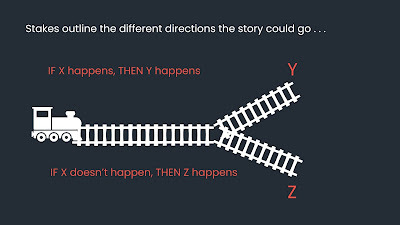

If X happens, then Y happens.

Which also implies, if X doesn't happen, then Y doesn't happen.

Or, we may be more specific and say, if X doesn't happen, then Z happens.

In any case, by laying out the potential consequences, we lay out two paths forward.

I like to imagine it as laying down railroad tracks, which shows the paths the train could go.

But notice the train can't travel down two paths at the same time.

It's an either-or situation.

That's what we want to set up in our stories, when it comes to stakes.

Covering every aspect of this topic is beyond the scope of this article, but at the basic level, it works like this.

The character has a goal (of which there are three types). Something opposes that goal (antagonist). And this creates conflict, which escalates.

There should be consequences tied to getting or not getting the goal.

If the character gets the goal, Y happens.

For example, if Harry successfully stops Voldemort from getting the Sorcerer's Stone, the Wizarding World will be saved.

If the character doesn't get the goal, then Z happens.

For example, if Harry fails to stop Voldemort from getting the Sorcerer's Stone, then Voldemort will return to power and the Wizarding World won't be saved.

These are potential consequences that the writer should convey before, or at least near the start of, the conflict.

Notice they also convey what's at risk (the Wizarding World's safety).

So these are the pathways the story could go.

But we can only travel down one.

We can't go two directions at once.

This creates a sense of either-or, similar to life or death. (Although admittedly, in my example, if Voldemort returns to power, there will eventually be death involved, but, generally speaking . . . )

This will also create a sense of finality, in the same way death does.

Figuratively speaking, the path we don't travel on "dies," because it is no longer an option. We can't go back and get on that train track. We've passed it. (We now have to deal with the consequences.)

When we hit an outcome--a condition--the pathway is selected.

Harry successfully stops Voldemort, so the Wizarding World is saved.

Harry successfully stopping Voldemort is also a turning point (a.k.a. a plot turn). It turns the direction of the story, it turns the story onto the path we laid out (since its condition was met).

With this, I like to think of the turning point as being the track that switches the direction of the train.

This switch also creates what some in the community call a "point of no return." (We can't go back and go down a different path. It's done. We are on a different trajectory now. (And yes, I am simplifying a bit.))

Stakes don't literally have to be life or death. But you need to set them up so that the pathways the story could go, look like either-or pathways. You need to set them up, so that outcomes can't be easily, foreseeably undone.

So let's look at a less dramatic example.

Your character needs to deliver an invitation to a royal wedding (goal). This isn't a life-or-death situation. In fact, it arguably sounds a little boring.

But when we tie potential consequences to it, not only does it become more interesting, but whether or not the character successfully does this, matters, because it changes the path, the trajectory of the story.

So, maybe we say . . .

If Melinda successfully delivers the invitation, then she'll be able to go to the royal wedding as well, which is where she'll have the chance to meet her hero.

I would need to communicate more contextual info to make this more effective. I would need to explain more about the stakes. Let's say her aunt said she'd take Melinda as her +1, if Melinda does this task for her (because the aunt really doesn't want to, because she has some high-priority things she needs to get done). Melinda's hero is from another continent, and she'll likely never have the opportunity to meet this person again. We could build it out more, so that she wants to get feedback on a project from her hero, and doing that could change Melinda's career path for the better.

We could even make her vocational situation more dire. If her current project isn't a success, then she'll be doomed to work for her father as his secretary (which she'd hate).

Now a lot hinges on successfully delivering this invitation.

If she successfully delivers the invitation, then Melinda can go to the wedding and get feedback from her hero, which will result in her not having to work for her father.

If she fails to deliver the invitation, not only will she not get to meet her hero at the wedding, but she'll have to work a job she can't stand.

Two paths forward.

She can't travel down both.

Now, we give her a lot of obstacles (antagonists) in the way of her delivering this invitation, so we have conflict (which should escalate).

Whether or not she delivers the invitation, is a turning point, because it turns the direction of the story, it turns her pathway. (Simplistically speaking, I could get more complex.) It's in some sense "a point of no return."

You can make almost any goal work, even a boring one, if you tie proper stakes to it.

The goal to survive (life vs. death stakes) is innately immediately effective, because we already understand it holds a "point of no return." If you die, you don't come back from that. There will also eventually be a point where, if you reach your goal, you won't be at risk of dying (at least, simplistically speaking, you won't die right at that moment.)

For other situations, you often need to build out and explain the stakes, for them to feel meaningful. You may need to provide contextual information, and you may need to walk the potential consequences out further so the audience understands everything that is at risk.

Let's talk about this from a character angle though . . .

Putting the Right Thing at Risk

One of the reasons the fun run Office example works, is because the writers put at risk what Michael cares about most: being liked. It's what motivates the majority of his actions on the show. It's what drives him. It's the want that he holds closest to his heart, his deepest personal desire.

Because it matters so much to him, the personal risk feels greater.

Michael feels, on some level, he will "die" psychologically, if he isn't liked or admired. (Which is also why he feels he will "die" if he is alone. (Even if he, himself, isn't fully conscious of either of these points.))

When the character cares about something that deeply, whether or not the character gets it, matters more.

Main characters should have at least one major want that drives them--something they want desperately, something they keep close to their hearts and deep in their psyches. It's often their most defining motivator. Michael wants to be liked. Harry wants to be where he belongs and is loved (the Wizarding World). Katniss wants to survive. Barbie wants to maintain a perfect life. Luke wants to become something great. Shrek wants to be alone so he can avoid judgment.

When we put any of those at risk, it raises the stakes.

. . . Because the characters not getting their deepest, heartfelt desires, has big personal ramifications on their psyches.

If what matters most to Shrek in his world is to be alone, and other fairytale creatures are being sent to his swamp, then the potential consequences are threatening what he holds most dear to his heart. Life as he knows it will figuratively "die" if he doesn't put a stop to it. (Of course, in order to complete his character arc, he has to be willing to let that part of him "die" so he can become something greater, someone more "whole.") It feels figuratively like "life or death" to him.

Ironically, putting the character's deepest desire at risk, can often be more effective than life or death stakes, because if you handled this right, you made sure to give the character a want that he will do almost anything to try to fulfill--even risk death for. Harry is willing to risk death to save the place where he is loved. Barbie is willing to risk death (well, at least her "life") in the real world to get her perfect life back. Luke is willing to risk death to become or be part of something great. Shrek is willing to risk death to get his swamp back (facing a dragon).

Recently I saw another great example of this while rewatching The Umbrella Academy. Hazel and Cha Cha kidnap Klaus and torture and threaten to kill him (to try to get information from him). But the torture and threats have no effect on him. In fact, Klaus gets off on it. Hazel and Cha Cha are at a loss as to how to break him.

While this is going on, Klaus eventually comes down from a drug-induced high. His superpower is that he can see and talk to the dead, but he hates that he has this ability--in fact, he's been traumatized by it (in a literal "ghost" story). It's actually the reason he's a drug addict to begin with. When he's high, he can't see or hear ghosts. Avoiding them is his deepest desire.

Torture and death don't break Klaus. What breaks Klaus is being unable to get away from the ghosts. It's only when Hazel discovers his stash of drugs and starts destroying it, that Klaus gets desperate. Not only are the drugs expensive (and he's broke), but worse, without them, Klaus has to face his greatest fear. He has to be surrounded by the dead. This is the exact opposite of his deepest desire.

In fact, to Klaus, this is something worse than death.

Some things are worse than death. And often, those things include your character's deepest desire, the want he holds closest to his heart.

Now sometimes, those things may overlap (like with Katniss being driven to survive), but most of the time, they will be different things. If you think about yourself, there are probably some things you would risk death for. Your first thought is probably your loved ones, and that is another risk you could consider for your characters, but I also bet, if we took that away as an option, you could think of a few other things, like a belief or way of life. Something you would uphold or defend when it's threatened. Something that would get you to do what you wouldn't ordinarily do, if it was at risk.

From there we create pathways again. Barbie can choose to risk the real world to get her perfect life back, or she can choose to remain in Barbieland and have her perfect life continue to deteriorate. She can't have both. Klaus can give up any information he has to try to save his remaining drugs, or he can resist and suffer a plague of ghosts. Shrek can let the fairytale creatures "kill off" his way of life, or he can go on a quest that could get rid of them.

This is still simplistically speaking, but the point is, you've put what the character cares deeply about at risk, and have laid out two paths forward, and the character can only choose one. She can't go in two directions at once.

Stakes don't literally need to be life vs. death to be effective, and in fact, as I've pointed out, some things are worse than death. One of those things is whatever the character wants most.

The idea is to lay out potential consequences--different pathways that appear as either-or trajectories. Either the story goes down path Y or it goes down path Z. The character then has to deal with the consequences of the path; she can't travel in reverse. She can try to diminish or compensate for the consequences (if they are undesirable), but she can't go back and change the track her train is on.

For most stakes that aren't life vs. death, you will need to convey to the audience what those potential pathways are, because they won't be built in like they are for life-or-death situations. One way to do this, is to literally write "If . . . then . . . " sentences into the story ("If X happens, then Y happens"), but you can convey them indirectly as well. The point is that you do communicate them to the audience, because if you don't, the audience won't see or feel the stakes, and so they won't be effective. And in that case, they will never be as impactful as life vs. death stakes.

Also, if you're interested in learning more about my take on stakes, I'm teaching a class on it at the Storymakers conference this May (virtual tickets are available for those who can't attend in person). I also get more into stakes (and plot) in my online writing course, The Triarchy Method (though the course is currently full, I'll offer it again in the future, so I still wanted to mention it. 😉).

Happy Writing!

#writing tips#creative writing#writing blog#how to write#writing advice#writing tips and tricks#writing fiction#writing help#author tips#author advice#writeblr#writers community#creative writers#writing community#writers on tumblr#writing#writers of tumblr#on writing#writers#writing life#writerscommunity#writing inspiration#writer stuff#novel writing#writer community#writer things#writer problems#resources for writers#helping writers

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing Tips - Beating Perfectionism

1. Recognising writing perfectionism. It’s not usually as literal as “This isn’t 100% perfect and so it is the worst thing ever”, in my experience it usually sneaks up more subtly. Things like where you should probably be continuing on but if you don’t figure out how to word this paragraph better it’s just going to bug you the whole time, or where you’re growing demotivated because you don’t know how to describe the scene 100% exactly as you can imagine it in your head, or things along those lines where your desire to be exact can get in the way of progression. In isolated scenarios this is natural, but if it’s regularly and notably impacting your progress then there’s a more pressing issue

2. Write now, edit later. Easier said than done, which always infuriated me until I worked out how it translates into practice; you need to recognise what the purpose of this stage of the writing process is and when editing will hinder you more than help you. Anything up to and including your first draft is purely done for structural and creative purposes, and trying to impose perfection on a creative process will naturally stifle said creativity. Creativity demands the freedom of imperfection

3. Perfection is stagnant. We all know that we have to give our characters flaws and challenges to overcome since, otherwise, there’s no room for growth or conflict or plot, and it ends up being boring and predictable at best - and it’s just the same as your writing. Say you wrote the absolute perfect book; the perfect plot, the perfect characters, the perfect arcs, the perfect ending, etc etc. It’s an overnight bestseller and you’re discussed as a literary great for all time. Everyone, even those outside of your target demographic, call it the perfect book. Not only would that first require you to turn the perfect book into something objective, which is impossible, but it would also mean that you would either never write again, because you can never do better than your perfect book, or you’ll always write the exact same thing in the exact same way to ensure constant perfection. It’s repetitive, it’s boring, and all in all it’s just fearful behaviour meant to protect you from criticism that you aren’t used to, rather than allowing yourself to get acclimated to less than purely positive feedback

4. Faulty comparisons. Comparing your writing to that of a published author’s is great from an analytical perspective, but it can easily just become a case of “Their work is so much better, mine sucks, I’ll never be as good as them or as good as any ‘real’ writer”. You need to remember that you’re comparing a completely finished draft, which likely underwent at least three major edits and could have even had upwards of ten, to wherever it is you’re at. A surprising number of people compare their *first* draft to a finished product, which is insanity when you think of it that way; it seems so obvious from this perspective why your first attempt isn’t as good as their tenth. You also end up comparing your ability to describe the images in your head to their ability to craft a new image in your head; I guarantee you that the image the author came up with isn’t the one their readers have, and they’re kicking themselves for not being able to get it exactly as they themselves imagine it. Only the author knows what image they’re working off of; the readers don’t, and they can imagine their own variation which is just as amazing

5. Up close and too personal. Expanding on the last point, just in general it’s harder to describe something in coherent words than it is to process it when someone else prompts you to do so. You end up frustrated and going over it a gazillion times, even to the point where words don’t even look like words anymore. You’ve got this perfect vision of how the whole story is supposed to go, and when you very understandably can’t flawlessly translate every single minute detail to your satisfaction, it’s demotivating. You’re emotionally attached to this perfect version that can’t ever be fully articulated through any other medium. But on the other hand, when consuming other media that you didn’t have a hand in creating, you’re viewing it with perfectly fresh eyes; you have no ‘perfect ideal’ of how everything is supposed to look and feel and be, so the images the final product conjures up become that idealised version - its no wonder why it always feels like every writer except you can pull off their visions when your writing is the only one you have such rigorous preconceived notions of

6. That’s entertainment. Of course writing can be stressful and draining and frustrating and all other sorts of nasty things, but if overall you can’t say that you ultimately enjoy it, you’re not writing for the right reasons. You’ll never take true pride in your work if it only brings you misery. Take a step back, figure out what you can do to make things more fun for you - or at least less like a chore - and work from there

7. Write for yourself. One of the things that most gets to me when writing is “If this was found and read by someone I know, how would that feel?”, which has lead me on multiple occasions to backtrack and try to be less cringe or less weird or less preachy or whatever else. It’s harder to share your work with people you know whose opinions you care about and whose impressions of you have the potential of shifting based on this - sharing it to strangers whose opinions ultimately don’t matter and who you’ll never have to interact with again is somehow a lot less scary because their judgements won’t stick. But allowing the imaginary opinions of others to dictate not even your finished project, but your unmoderated creative process in general? Nobody is going to see this without your say so; this is not the time to be fussing over how others may perceive your writing. The only opinion that matters at this stage is your own

8. Redirection. Instead of focusing on quality, focusing on quantity has helped me to improve my perfectionism issues; it doesn’t matter if I write twenty paragraphs of complete BS so long as I’ve written twenty paragraphs or something that may or may not be useful later. I can still let myself feel accomplished regardless of quality, and if I later have to throw out whole chapters, so be it

9. That’s a problem for future me. A lot of people have no idea how to edit, or what to look for when they do so, so having a clear idea of what you want to edit by the time the editing session comes around is gonna be a game-changer once you’re supposed to be editing. Save the clear work for when you’re allocating time for it and you’ll have a much easier and more focused start to the editing process. It’ll be more motivating than staring blankly at the intimidating word count, at least

10. The application of applications. If all else fails and you’re still going back to edit what you’ve just wrote in some struggle for the perfect writing, there are apps and websites that you can use that physically prevent you from editing your work until you’re done with it. If nothing else, maybe it can help train you away from major edits as you go

#writing tips#creative writing#writing blog#how to write#writing advice#writing tips and tricks#writing fiction#writing help#author tips#author advice#writeblr#writers community#creative writers#writing community#writers on tumblr#writing#writers of tumblr#on writing#writers#writing life#writerscommunity#writing inspiration#writer stuff#novel writing#writer community#writer things#writer problems#resources for writers#helping writers#perfectionism

296 notes

·

View notes

Note

how do you write a liar?

How to Write Liars Believably

Language

The motive of every goal is the make the lie seem plausible while taking blame off the speaker, so liars will often project what they say to a third party: "Katie said that..."

Referring to third parties as "they" rather than he or she

In the case of a deliberate lie prepped beforehand, there will be an overuse of specific names (rather than pronouns) as the speaker tries to get the details right.

Overuse of non-committal words like "something may have happened"

Masking or obscuring facts like "to the best of my knowledge" and “it is extremely unlikely," etc.

Avoiding answers to specific, pressing questions

Voice

There's isn't a set tone/speed/style of speaking, but your character's speech patten will differ from his normal one.

People tend to speak faster when they're nervous and are not used to lying.

Body Language

Covering their mouth

Constantly touching their nose

fidgeting, squirming or breaking eye contact

turning away, blinking faster, or clutching a comfort object like a cushion as they speak

nostril flaring, rapid shallow breathing or slow deep breaths, lip biting, contracting, sitting on your hands, or drumming your fingers.

Highly-trained liars have mastered the art of compensation by freezing their bodies and looking at you straight in the eye.

Trained liars can also be experts in the art of looking relaxed. They sit back, put their feet up on the table and hands behind their head.

For deliberate lies, the character may even carefully control his body language, as though his is actually putting on a show

The Four Types of Liars

Deceitful: those who lie to others about facts

2. Delusional: those who lie to themselves about facts

3. Duplicitious: those who lie to others about their values

Lying about values can be even more corrosive to relationships than lying about facts.

4. Demoralized: those who lie to themselves about their values

Additional Notes

Genuine smiles or laughs are hard to fake

Exaggerations of words (that would normally not be emphasized) or exaggerated body language

Many savvy detectives ask suspects to tell the story in reverse or non-linear fashion to expose a lie. They often ask unexpected, or seemingly irrelevant questions to throw suspects off track.

#writing tips#creative writing#writing blog#how to write#writing advice#writing tips and tricks#writing fiction#writing help#author tips#author advice#writeblr#writers community#creative writers#writing community#writers on tumblr#writing#writers of tumblr#on writing#writers#writing life#writerscommunity#writing inspiration#writer stuff#novel writing#writer community#writer things#writer problems#resources for writers#helping writers

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Importance of Body Language

Describing a character’s body language can be very important and helps your story from being too “telly”. You end up showing your readers how your characters are feeling instead of constantly telling them what’s going on. For example, if someone’s face “burns bright red”, you know they’re either angry or embarrassed (or perhaps a combination of both). Depending on context, your readers can figure out how your character is reacting. Using these simple techniques can help improve your story and make it much more entertaining.

A character that is over confident (possibly the antagonist) will most likely stand taller, put hands on his or her hips, or bark orders at others. The way they sit will also reveal a lot about their character. Their legs will probably be unfolded and they might sit up straighter to show dominance.

Someone who is shy and closed off will slump his or her shoulders or wrap their arms around their legs if they are sitting. They will do anything to remain unnoticed, which will come across in their body language. Submissive people tend to smile a lot because they might not want to engage in conversation.

Anger can be described through clenched teeth, reddening skin, heavy breathing, or crossing arms. If a character feels physically threatened, he or she might ball her fists as if ready for a fight.

When people lie they tend to touch their face or avoid eye contact. They will try any physical action that might distract people from the fact that they are lying and it will often be subtle.

I once read that when you’re attracted to someone or open to conversation with them, you’ll point your knees in their direction. Your knees will often face the person who you wish to talk to. If someone is not open to conversation or feels uncomfortable, they will turn their body away from the person to show they aren’t interested.

There are a lot of clues in everyday life as long as you pay attention to them. If you want to learn more about body language, all you have to do is analyze the people around you or even yourself. What do you do when you lie? How do people know when you’re happy? Take a look around and observe.

#writing tips#creative writing#writing blog#how to write#writing advice#writing tips and tricks#writing fiction#writing help#author tips#author advice#writeblr#writers community#creative writers#writing community#writers on tumblr#writing#writers of tumblr#on writing#writers#writing life#writerscommunity#writing inspiration#writer stuff#novel writing#writer community#writer things#writer problems#resources for writers#helping writers#editing

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

hi I'm from your pseudo-medieval fantasy city. yeah. you forgot to put farms around us. we have very impressive walls and stuff but everyone here is starving. the hero showed up here as part of his quest and we killed and ate him

#writing tips#creative writing#writing blog#how to write#writing advice#writing tips and tricks#writing fiction#writing help#author tips#author advice#writeblr#writers community#creative writers#writing community#writers on tumblr#writing#writers of tumblr#on writing#writers#writing life#writerscommunity#writing inspiration#writer stuff#novel writing#writer community#writer things#writer problems#resources for writers#helping writers#editing

30K notes

·

View notes

Text

You don’t have to pay for that fancy worldbuilding program

As mentioned in this post about writing with executive dysfunction, if one of your reasons to keep procrastinating on starting your book is not being able to afford something like World Anvil or Campfire, I’m here to tell you those programs are a luxury, not a necessity: Enter Google Suite (not sponsored but gosh I wish).

MS Office offers more processing power and more fine-tuning, but Office is expensive and only autosaves to OneDrive, and I have a perfectly healthy grudge against OneDrive for failing to sync and losing 19k words of a WIP that I never got back.

Google’s sync has never failed me, and the Google apps (at least for iPhone) aren’t nearly as buggy and clunky as Microsoft’s. So today I’m outlining the system I used for my upcoming fantasy novel with all the helpful pictures and diagrams. Maybe this won’t work for you, maybe you have something else, and that’s okay! I refuse to pay for what I can get legally for free and sometimes Google’s simplicity is to its benefit.

The biggest downside is that you have to manually input and update your data, but as someone who loves organizing and made all these willingly and for fun, I don’t mind.

So. Let’s start with Google Sheets.

The Character Cheat Sheet:

I organized it this way for several reasons:

I can easily see which characters belong to which factions and how many I have named and have to keep up with for each faction

All names are in alphabetical order so when I have to come up with a new name, I can look at my list and pick a letter or a string of sounds I haven’t used as often (and then ignore it and start 8 names with A).

The strikethrough feature lets me keep track of which characters I kill off (yes, I changed it, so this remains spoiler-free)

It’s an easy place to go instead of scrolling up and down an entire manuscript for names I’ve forgotten, with every named character, however minor their role, all in one spot

Also on this page are spare names I’ll see randomly in other media (commercials, movie end credits, etc) and can add easily from my phone before I forget

Also on this page are my summary, my elevator pitch, and important character beats I could otherwise easily mess up, it helps stay consistent

*I also have on here not pictured an age timeline for all my vampires so I keep track of who’s older than who and how well I’ve staggered their ages relative to important events, but it’s made in Photoshop and too much of a pain to censor and add here

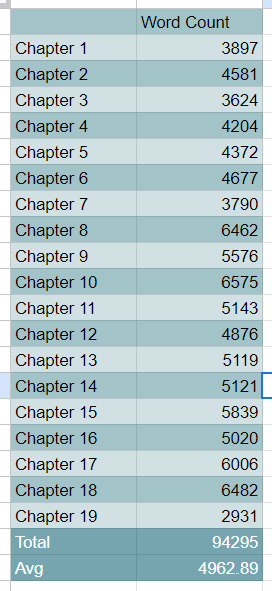

On other tabs, I keep track of location names, deities, made-up vocabulary and definitions, and my chapter word count.

The Word Count Guide:

This is the most frustrating to update manually, especially if you don’t have separate docs for each chapter, but it really helps me stay consistent with chapter lengths and the formula for calculating the average and rising totals is super basic.

Not that all your chapters have to be uniform, but if you care about that, this little chart is a fantastic visualizer.

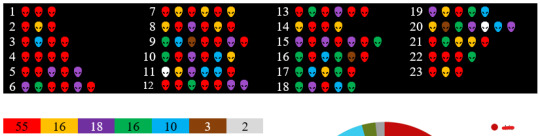

If you have multiple narrators, and this book does, you can also keep track of how many POVs each narrator has, and how spread out they are. I didn’t do that for this book since it’s not an ensemble team and matters less, but I did for my sci-fi WIP, pictured below.

As I was writing that one, I had “scripted” the chapters before going back and writing out all the glorious narrative, and updated the symbols from “scripted” to “finished” accordingly.

I also have a pie chart that I had to make manually on a convoluted iPhone app to color coordinate specifically the way I wanted to easily tell who narrates the most out of the cast, and who needs more representation.

—

Google Docs

Can’t show you much here unfortunately but I’d like to take an aside to talk about my “scene bits” docs.

It’s what it says on the tin, an entire doc all labeled with different heading styles with blurbs for each scene I want to include at some point in the book so I can hop around easily. Whether they make it into the manuscript or not, all practice is good practice and I like to keep old ideas because they might be useful in unsuspecting ways later.

Separate from that, I keep most of my deleted scenes and scene chunks for, again, possible use later in a “deleted scenes” doc, all labeled accordingly.

When I designed my alien language for the sci-fi series, I created a Word doc dictionary and my own "translation" matrix, for easy look-up or word generation whenever I needed it (do y'all want a breakdown for creating foreign languages? It's so fun).

Normally, as with my sci-fi series, I have an entire doc filled with character sheets and important details, I just… didn’t do that for this book. But the point is—you can still make those for free on any word processing software, you don’t need fancy gadgets.

—

I hope this helps anyone struggling! It doesn’t have to be fancy. It doesn’t have to be expensive. Everything I made here, minus the aforementioned timeline and pie chart, was done with basic excel skills and the paint bucket tool. I imagine this can be applicable to games, comics, what have you, it knows no bounds!

Now you have one less excuse to sit down and start writing.

#writing tips#creative writing#writing blog#how to write#writing advice#writing tips and tricks#writing fiction#writing help#author tips#author advice#writeblr#writers community#creative writers#writing community#writers on tumblr#writing#writers of tumblr#on writing#writers#writing life#writerscommunity#writing inspiration#writer stuff#novel writing#writer community#writer things#writer problems#resources for writers#helping writers#editing

819 notes

·

View notes

Note

can a villain be a good villain without having a backstory that justifies why they behave the way they do, or a backstory that helps people see where he is coming from? would my villian be a bad villain if he just desired power for the sake of having power? i dont want to write a villain where people learn about him and come to the conclusion that "hes right" or can be redeemed

No Redemption Villains

There are plenty of "good" villains with no redemption arcs!

Your villain can be the epitome of twisted ambition, power-hungry, and cruelty, with little else giving them reason to do what they do. However, they need some internal logic that justifies all of their motivations and actions in their own worldview.

This is different from the backstory in that:

The "justification" your villain has is in fact no justification at all

Only the villain (+his closest allies) believe in the "story" or "worldview"

Think of it like this: For you, the Earth is flat. Since you totally believe in this "fact", you never travel outside of your continent, never travel by plane, etc. Others may call you stupid, try to educate you, maybe even force you to get on a plane and take you somewhere that shouldn't exist in your Flat Earth. However, you're not swayed. You just keep believing what you've always believed.

This is what your villain has to be. A complete lunatic in other's eyes, but a sage in their perspective.

Look at your story world from the villain's perspective

Redefine everything from the villain's POV. No one does things that they truly don't believe in.

Each time you write your villain, believe this almost alternate universe.

#writing tips#creative writing#writing blog#how to write#writing advice#writing tips and tricks#writing fiction#writing help#author tips#author advice#writeblr#writers community#creative writers#writing community#writers on tumblr#writing#writers of tumblr#on writing#writers#writing life#writerscommunity#writing inspiration#writer stuff#novel writing#writer community#writer things#writer problems#resources for writers#helping writers#editing

181 notes

·

View notes

Text

20 Emotional Wounds in Fiction That Make Readers Root for the Character