Text

Vaughan Mazursky, the Czarina

Those souls brave enough to phone the lady who ruled over middle schoolers with an iron fist probably found it disconcerting to hear that Vaughan Mazursky’s voicemail greeting was a low-quality recording of ABBA she had made by holding the receiver up to the stereo: "Mamma mia, here I go again!" In that musical limbo before the beep, former students might be forgiven for pondering the absurdity of having to reconcile the piped-in Swedish ballad with scenes of remembered terror from GAWA: the Czarina charging, at almost a 45-degree angle, toward the disobedient student’s desk, gaining momentum and fury as she closed the distance. Personally, my thoughts waiting for the beep hovered not over her classroom by the Ashley but over the land of ABBA — Stockholm in particular: I had come to deeply love my captor.

Outré incongruities were the A’s and T’s, C’s and G’s of Ms. Mazursky, who was nothing if not surprising, contradictory, weird, and beautiful. After all, one does not become the Czarina by having even a single fleeting worry about what others might think.

Ms. Mazursky died this morning, threading a cosmic needle: she held on just long enough to see her Democrats succeed in Kentucky, Ohio, and Virginia — and left just early enough to avoid the Republican debate.

No teacher ever challenged me in the precise way the Czarina did. So unabashedly herself — it was the Czarina who, just a few years ago, broke the indecisive lull on the dancefloor at my sister’s wedding, rushing out after just a few chords of Marvin Gaye — Ms. Mazursky had no patience for artificiality, conformity, or normality. Her mere existence gave weird kids the permission to be themselves. Indeed, so far removed from the normal and typical was she that she frequently ignored normal, typical things like bells and closed doors. Sharon Tate had fewer unwelcome guests than Dr. Slayton, whose classes the Czarina — more often than not halfway through a sentence before the door had fully opened — routinely annexed with talk of NCAA shakeups or political shakedowns.

Thinking of her as I look out at my own students writing essays, I am grateful that among the most critical skills she taught generations of eighth graders was how to distinguish between reliable and unreliable sources, invaluable for navigating messy global affairs. Such a practice feels extra handy today, though, because it can be hard to distinguish between fact and legend upon hearing any Mazoo story: Did she once extol the value of Hammurabi’s Code as a classroom management device? (Yes.) Did she swear us to silence while she went to the copy room only to hear us talking upon her return and proceed to ask each student, one by one, to swear, on their mother’s life, that they had not violated the silent sanctum of the Czarina? (Also yes.) Had she indeed pioneered the medically inadvisable no-water-only-TAB diet? (Probably yes.) Did she antagonize a Soviet tank to spark a revolution? (Absolutely yes.)

A rule of thumb I’ve found helpful over the years is a simple substitution: if the story still sounds feasible after having swapped out “the Czarina” for “the Trunchbull,” then, with few exceptions, the story is probably true.

Teaching us the poetry of the Enlightenment, Wesley Moore began with a stunning visual: Alexander Pope clocked in at four-and-a-half feet of bone-crunching fury. In short, as it were, we sophomore English students should imagine Alexander Pope as an Augustan Vaughan Mazursky. But, while Pope was many things, to my knowledge he never insisted that flocks of middle schoolers swear an oath of undying fealty to serve him as his boyars, never arranged his social and academic schedule around the ‘Hoos, and — despite his fair share of quirks and eccentricities — did not grow up in the splash radius of a nuclear power plant.

Vaughan Mazursky, the Czarina of Porter-Gaud, did.

More than anyone else, Ms. Mazursky taught me that the political is personal. Uninformed or unexamined political belief was not ideology, she taught us, but instinct. (She did go on to explain that, because many of us were genetically undifferentiated from the apes of Borneo, instinct was, in fairness, the closest we could get to an actual ideology.) When I thought that I could skate by on cruise control as a fellow liberal, the Czarina put an end to any such illusion. For Latin, I had made a poster of politicians I admire — in a reactionary, teenaged kind of way, I decided to paint with too broad a brush — the Czarina ripped it from my hands, took a sip of Diet Coke, pointed out Ted Kennedy, pointed at me, pointed back at Ted Kennedy, and, squinting up at my face, said: “Werrell, you dingbat. He killed a woman. Read a newspaper or open a book before you decide to admire someone.”

Politics was the backbone of her life and of her classes. George McGovern, sun-faded and looking down from the bulletin board, was the perpetual teacher’s aide in the classroom, part of each conversation: “Well, George, how about that?” A few years later, she emerged from Senator Obama’s speech cistern yard at College of Charleston and landed on national newspapers, arms triumphantly up and looking like she was in a montage from “Rocky.”

Despite the urban legends generations of eighth graders shared with younger students, I feel like I can confidently say that Ms. Mazursky never killed any student — though even that would not curtail my admiration for her.

0 notes

Text

Affirmative Action

Dissenting in Students for Fair Admission, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson describes the pernicious way that, in the wake of any law aimed at establishing meaningful equality, certain white Americans feel “slighted.”

This is nothing new; Justice Jackson illustrates this by citing the disastrous Civil Rights Cases of 1883, in which an 8-1 majority found the Civil Rights Act of 1875 to be unconstitutional, bringing an end to Reconstruction and an unconscionable halt to legal protections for Black Americans. The language of that majority opinion is eerily prescient; the author, Justice Joseph Bradley, writes what one might easily mistake for an evening monologue on Fox:

“When a [Black American], by the aid of beneficent legislation, has shaken off [enslavement], there must be some stage in the progress of his elevation when he takes the rank of a mere citizen,” Bradley the Bootstrapper writes on behalf of the Court, “and ceases to be the special favorite of the laws.” Bradley displaces responsibility for inequality from those who wrote the laws to those who were captives of the laws, complaining that, owing to the progressives’ insatiable appetite for equality, the scales of justice tipped too far toward favoring Black Americans. (It is all too easy to project more contemporary debates — the stubborn resistance to Martin Luther King, Jr. Day and Juneteenth as Federal holidays, for instance, or the mere existence of Black History Month — onto this one-hundred-forty-year-old opinion.)

Having defined the present injustice, Bradley then pivots to a two-part redefinition of the past. He first hearkens back to those halcyon days of racial harmony during slavery — “There were thousands of free colored people in this country before the abolition of slavery enjoying all the essential rights of life, liberty, and property the same as white citizens” — before lamenting the divisive overreach that indoctrinated ill will and sowed the seeds of racial discord: “yet no one at that time thought that it was any invasion of his personal status as a freeman because [the Black American] was not admitted to all the privileges enjoyed by white citizens.” Remember those bucolic days on the plantations when we just got along, when we weren’t taught to hate one another or ourselves simply because of the color of our skin?

If they hadn’t banned every book that mentions race (and weren’t incapable of stringing together a coherent compound-complex sentence), Moms for Liberty could have written that sentence. After all, white victimhood and wistful appeals to fake memories are not endemic to judicial arguments; they instead are so pervasive as to be the very bedrock undergirding American conservatism and the platform of major candidates.

Memory is a powerful, malleable, fallible thing, and, as a shepherd wields a crook, Republicans employ treacly glosses of the past to lull voters into a terminal nostalgia, one that has substituted “Leave it to Beaver” for actual childhood memories. Nikki Haley, spastic conservative colon of South Carolina and bush-league politician, is good for more than just compromising the Social Security Numbers of every South Carolinian; her rhetoric, clumsier and more obvious than Larry Craig in an airport bathroom, lays bare the big game: “Do you remember when you were growing up, do you remember how simple life was, how easy it felt? It was about faith, family, and country. We can have that again, but to do that, we must vote Joe Biden out.”

Life is never simple. Life has never been easy. But the “Again” in MAGA is nevertheless conjured up daily by conservative lotus eaters on Facebook who share insipid “copypasta” about how they rode their bikes for hours around the neighborhood and weren’t afraid of anything and school was mandatory and teachers were people you could trust and respect and how they watched their mouths around their elders and dressed respectably and how their angelic mothers wielded both fresh cookies and her wooden spoon and always stood there lovingly at the end of curfew with her arms akimbo when her boys showed up muddy.

Of course, such memories are patently fake: the middle of the century in America was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of civility, it was the age of sit-ins and German shepherds, it was the epoch of scientific wonder and space, it was the epoch of thalidomide and Agent Orange, it was the golden era of nonviolence, it was the bloated body of Emmett Till, it was afternoons spent without care, it was the Lavender Scare, it was the summer of flowers and love, it was the summer of assassinations.

Any glancing familiarity with or conversations about these wildly heterogenous realities, however, would eliminate the win condition for Republicans: that voters are stupid enough to conflate fake memories with real values. A Republican win requires willful denial, a blind embrace of a whitewashed past. Republicans need a “Mandela effect”: a fake memory in which Nelson does not die but instead publicly voices that he’s cool with Apartheid.

And because Republicans like DeSantis and Trump need an electorate with as complete a knowledge of American history as a CCPedia article on Tiananmen Square, they are hellbent on destroying education in America. As the “Woke Mind Virus” throws up cannons to the right, left, and front of the White Brigade, Republicans rush to codify provisos and slash budgets to ensure that only the most anemic history and only the most anodyne perspectives appear on any syllabus. (Shoutout to Mary Wood, ratted out by her students for daring to assign them Ta-Nehisi Coates.) As allegations of “grooming” and “indoctrination” abound in schoolboard debates, Charlie Smirk leads his benighted crusaders against college campuses, those petri dishes of communism and hedonism.

Affirmative action — to such empty suits the death knell of classical meritocratic education — was among the largest targets for conservatives; a less diverse campus, after all, means more “free speech” (i.e., bigoted speech without repercussion or consequence). All told, “Students for Fair Admissions, Inc.” is a grand old victory for the Republicans in their war against education.

The case was brought before the Supreme Court by an incorporated body of mediocre students, helicopter parents, alums who never framed their degrees, and the racist windbag Edward Blum — all purporting to have been treated unfairly, all bemoaning an imbalance in admissions. The only possible explanation for why they were rejected from Harvard or UNC, this corporation argues, is that their dream school lowered standards in order to admit a less-qualified and undeserving Black student — solely because of that applicant’s race. (Note that Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. did not target legacy and donor admissions. Makes you think!)

What is their “evidence” for this?

The existence of a Black student at any institution that has ever rejected a white applicant (or, with kudos to Blum’s excellent ventriloquism and shameless manipulation, an AAPI applicant).

In his opinion eliminating affirmative action, Chief Justice John Roberts directly rebukes Justice Jackson with a lengthy excerpt from a case thirteen years after “Civil Rights Cases”:

‘Justice Harlan knew better,’ one of the dissents decrees. Indeed he did: ‘[I]n view of the Constitution, in the eye of the law, there is in this country no superior, dominant, ruling class of citizens. There is no caste here. Our Constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens.’

Most anyone who has written a high school paper will recognize Roberts’ brackets, which indicate a writer has meddled with a quotation. Roberts’ alteration here may seem small — the streamlining of a quotation; the weird APA practice of capitalizing after a colon — however, its diminutive size on paper belies its unbelievably large admission. Because in the full text of Harlan’s famous dissent to “Plessy v. Ferguson,” the word before “in” is “But”:

The white race deems itself to be the dominant race in this country. And so it is in prestige, in achievements, in education, in wealth and in power. So, I doubt not, it will continue to be for all time if it remains true to its great heritage and holds fast to the principles of constitutional liberty. But in view of the Constitution…

Harlan, born to a Kentucky family that purchased, owned, and sold humans, believed that, barring any perverse swerve away or premature exit from white “heritage,” white people were comfortably on cruise control in the United States. Such a supposition reveals his belief in a fair and balanced order of races, and that that “natural” hierarchy dictates that the white person — even an Abigail Fisher — “naturally” dominates non-whites.

The underlying belief of this corporation and the majority of the Supreme Court is not that different from Justice Harlan’s opinion (the portion, that is, John Roberts did not excerpt) and not that different from Justice Bradley’s: most anything past abolition and enfranchisement is undue overcompensation, the special treatment and even coddling of Black Americans. Race blindness in admissions, they believe, will restore the “fair and balanced order” that affirmative action jolted askew. Race blindness will ensure that only the most qualified applicants — which is to say the white applicants — receive large envelopes, thereby rectifying the imbalance and diminished standards of college campuses.

Top: Daniel A. Varela / Miami Herald via AP file

Bottom: AP Photo / Jose Luis Magana

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thinking about MLK

In his sixth thesis on The Philosophy of History, Walter Benjamin warns of violent conformists “overpowering” history and transforming it into yet another “tool of the ruling class”; the only successful historian, Benjamin prophesies, is that one “who is firmly convinced that even the dead will not be safe” from such enemies. But the Martin Luther King, Jr. — murdered at the hands of a vicious white supremacist, a man who enacted the silent wish of so many — whom we resurrect on the third Monday in January each year is too often a tool of the very same interests he spoke against: those who would disenfranchise our neighbors and cordon off our democracy, those who dream of a government only big enough to take care of the wealthy. It is important to remember every day, but especially today, that King was not a carefully curated collection of politically palatable quotations, not an anodyne activist who spoke dreamingly of a colorblind America. King and his legacy do not belong to the conformists.

King was a radical.

In her elegy In Memoriam: Martin Luther King, Jr, June Jordan makes the appropriately radical decision to abjure punctuation and traditional form; instead, her words slip, spill, and drip down the page:

honey people murder mercy U.S.A.

the milkland turn to monsters teach

to kill to violate pull down destroy

the weakly freedom growing fruit

from being born

America

tomorrow yesterday rip rape

exacerbate despoil disfigure

crazy running threat the

deadly thrall

appall belief dispel

the wildlife burn the breast

the onward tongue

the outward hand

deform the normal rainy

riot sunshine shelter wreck

of darkness derogate

delimit blank

explode deprive

assassinate and batten up

like bullets fatten up

the raving greed

reactivate a springtime

terrorizing

death by men by more

than you or I can

STOP

They sleep who know a regulated place

or pulse or tide or changing sky

according to some universal

stage direction obvious

like shorewashed shells

we share an afternoon of mourning

in between no next predictable

except for wild reversal hearse rehearsal

bleach the blacklong lunging

ritual of fright insanity and more

deplorable abortion

more and

more

Blake wrote that “to create a little flower is the labour of ages,” but here, that labor is violently interrupted: Americans are taught to become monsters and to rip out the “freedom growing fruit” by the stem while it is weak, before it can ripen. In a perversion of growth, “rip” is permitted the fertile soil, light, and warmth to blossom into “rape” and “exacerbate.” The fruit is spoiled, humans are despoiled, and, as chaos and hatred rush exhaustingly rush down the stanzas, rest comes not for the wicked, but the privileged: those who know their place amid the universe’s “stage direction[s],” those for whom the world is rightside-up, those for whom a traffic stop is not a death sentence. All that is left, then, is a sleepless and never-ending “afternoon of mourning,” a dress rehearsal for death.

Today, I linger especially on a single line from the poem, a chasmically tragic sentiment: “no next predictable / except for wild reversal.” The only constant, Jordan writes, is vertiginous upheaval: the likelihood that one might, one April night, speak out about the dignity of labor and, the next day, bleed out on a motel balcony. But Jordan reminds us that these are, to misquote Hamlet, “the slings and arrows” not of outrageous fortune but of daily life.

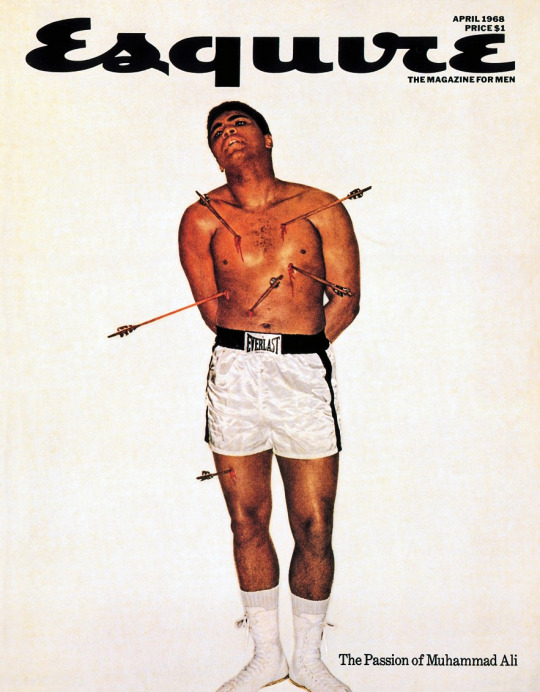

Just a few days before King was shot and killed, the April issue of Esquire hit newsstands. For the cover, Carl Fischer, with direction from George Lois, styled and photographed Muhammad Ali as St. Sebastian:

Here, before the assassination, those “slings and arrows” are literalized. Reactionary racial, religious, and political abuses — pro-Black, Islam, and Vietnam — penetrate the heavyweight; his face, not so much a rictus of agony as it is a plea, fades backward into the horizontal plane. Just as those arrows converge on their target, tools of violence and destruction intersecting with Black flesh, so, too, does this photograph represent a convergence of identities and discrimination.

“I am reaching for the words to describe the difference between a common identity that has been imposed,” Jordan, who was a bisexual, writes in Report from the Bahamas, “and the individual identity any one of us will choose, once she gains that chance.” Those dual, dueling identities strike at the heart of Jordan’s works, of life in the liminal space between harmony and honesty, between fidelity and conformity — a pained existence that Walt Whitman, in an early “Calamus” poem, describes as finding a balance between the true “soul” and “the life that exhibits itself” — and are made manifest in this magazine cover.

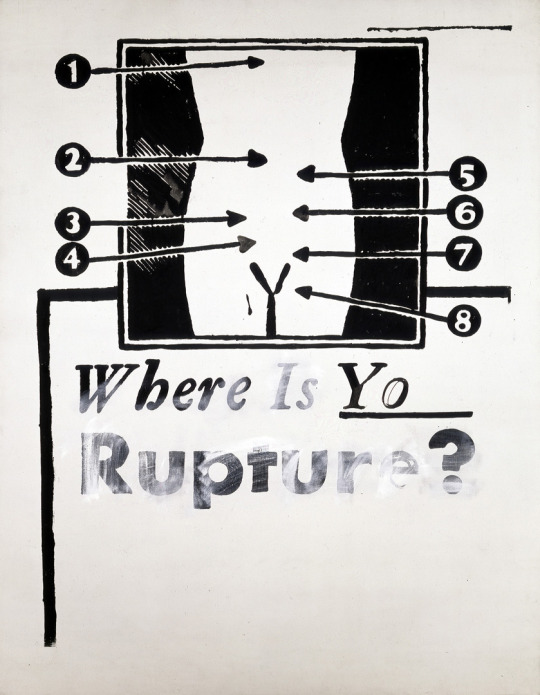

St. Sebastian — whose feast day is this Friday — has long been considered a gay saint. While Freudian critics and readers might find this genesis primarily in the role penetration plays in St. Sebastian’s martyrdom, more basically St. Sebastian was a man with a secret: he was, behind closed doors and despite the wishes of his employer, his colleagues, his friends, and his neighbors, someone or something different, a worshipper of Jesus Christ. Upon turning away from “the life that exhibits itself” and revealing his “soul,” so to speak, St. Sebastian was tortured, suffered, and then was killed. One might see this affinity in Oscar Wilde’s pseudonym, “Mr. Sebastian Melmoth,” and throughout the oeuvre of, to name a few, Marsden Hartley, Jasper Johns, and Andy Warhol, whose piece Where is Your Rupture? is below.

Like King, Jordan recognizes that, despite so many of the oppressed’s sharing a common enemy, too many toil in solitude rather than in solidarity: “As long as there are [queer] Americans who view sexuality as the first and last defining facet of their existence, and who, therefore, do not defend immigrants against the savagery of xenophobic hatred, as long as there are [queer] Americans who view sexuality as the first and last defining fact of their lives, then for that long I am not one with you and you are not one with me.”

Benjamin closes his sixth thesis by writing that “this enemy [who would conquer and coopt the dead] has not ceased to be victorious.” If there is a colorblind aspect of King’s dream for America, it is colorblind only insofar as it is a vision of harmonious collaboration in dismantling oppression: the only way to defeat the enemy is through intersectional solidarity.

0 notes

Text

T

“Kiyaala mooko kufwa kò.”

“The man who extends his hands will never die.”

– Bakongo proverb

It is known among the Yoruba that whenever a man advances, he leeches Àshe away from the people around him; the measure of a man, then, is taken not by his station, but by how much Àshe he gives back to others and the world around him. A generous man will never die because he will live on in the memories he shared with others. Robert Farris Thompson extended his hands to all his students, sharing more than memories.

T gave his students a new future by teaching them a new way of seeing.

For me, T’s lessons were vertiginous inversions of the world I had understood beforehand. There was no gradual erosion of my Western- and white-centric education; instead, a seismic upheaval changed the topography of my bookshelf and life. “Primitive” became a four-letter word, an adjective for use only in emergencies of extreme ignorance (or to describe the Harvard football team). When a music historian at Yale commented that the interlocking of vocal lines in Mande music was primitive and reminiscent of undeveloped medieval music in Europe, T erupted like Vesuvius. “A hocket isn’t primitive, motherfucker,” he patiently explained to our class. “A hocket is the democrati-fucking-zation of sound.”

T, who had excelled at Phillips Andover and then at Yale, detested nothing more than the cultural myopia and closed-mindedness that surrounded him in his studies. Thus positioned as an inside-outsider, he had very little patience for the tightly-wound and overly-proper, for those who saw academia as the opposite of the universe: as an entity whose borders should not expand but shrink. Before he became just the second professor of African Art in the United States, Africa and the Afro-Atlantic were firmly circumscribed by the classroom walls of the Anthropology Department; and, even as he became established at Yale, T struggled against his colleagues’ habit of tethering Black art to white analogues—as if art needed a corresponding contrast to justify its existence as art and not as mere object.

T fought against this small-mindedness every day of his life. To the chagrin of many traditionalists in his department, T began his survey of Western art on the wrong side of the Alps: with the ways in which Gallic and Germanic craftspeople manipulated intense heat and molten lead around their village fires. Far from the Druidic and Gothic roughness most of my classmates and I imagined, T highlighted the intricacy and, indeed, delicacy of this craftwork. Rome could make as much cement as its imperial heart desired, but all the cement in the world would not cast the magnificent technicolor light of the rose windows at Chartres. And each one of his lectures cast that same light into the darkest recesses of our learning, expelling ignorant biases. “There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio,” than were taught in your classroom before.

The world was T’s classroom, and his lectures—kinesthetic and calisthenic, with mandatory dancing, jumping, and moving around—spilled out from the Gallery and onto the streets. (Sometimes conversations would stretch all the way to T’s car, but woe betide the student who hitched a ride, as T’s compact car would glide freely across the street, for the steering wheel was among his preferred percussive instruments.) The dining hall was a mambo hall and salsa lounge, a bomba floor and tango club. Bringing in dancers, singers, and bands from all over the world, from young lindyhop champions to wizened salsa experts he’d once twirled at the Palladium, T reminded us at every opportunity that “tango” meant “love.” Learning such a suave dance, he assured us, would turn any “weenie, stumped for a comeback to ‘Hello,’ into a guy or woman of attraction.” (One night, when we danced until close to eleven, T climbed atop a dining table to get a better photographic angle of the dancefloor; he wanted to capture Facundo Posadas, the great Afro-Argentine tango expert, in action. When he lifted a chair to climb even higher, Jalal and I coaxed him down like a cat out of a tree and lifted him off the table.)

Even the clothes he wore were an extension of his work: rarely would T emerge from the gates of Timothy Dwight without at least three clashing patterns. He often imagined the horror of the clothiers at J. Press, which he called “J. Squeeze,” at seeing madras shorts against a paisley tie, striped shirt, and green jacket, but dismissed any such concerns: his combinations of conflicting patterns were, he insisted, an imitation of and homage to the multiple meter of the African and Afro-Atlantic music with which he had long ago fallen in love. He took a perverse pleasure in conquering Union League Café in such attire, where, on numerous occasions, he horrified other diners by demonstrating the complexities of multiple meter with a steak knife and three wine glasses.

One of the last times I saw T, we were returning to the nursing home from dinner and a double-header movie—and, as ritual required—late-night/early-morning ice cream. That night, we found his grandparents’ Texas home on my phone’s map; he spent fifteen minutes walking down their streets with his fingers and through his memories. We pulled up to the nursing home at close to one in the morning, about eleven days before COVID barred the door to loved ones. “Well, it’s regression time here at the ranch,” he said as I wheeled his walker to the passenger door of the car. Because it was well past midnight, we had to wait for the night watchman to let us in from the cold; T sat in his walker with his gloves, his knit cap, and his tweed jacket poking out from under his winter coat, cursing up a storm.

“You know these people go to bed at 7? They’re like fucking babies.”

I walked T to the elevator, said goodnight, and heard the familiar clanging as the doors closed. In the last decade of his life, you could always hear him before you saw him and after you could no longer see him. I don’t mean the whistle of his hearing aid, which he always put in incorrectly, but rather the constant noises he made, the constant beat he plucked from the world around him. The digital tracker marked the change in floors to the sound of his tapping his ring against the metal bar of the elevator; the beat I recognized as one of Anibal Troilo’s tangos.

T grew old, but he never aged.

My first year at Yale, when he found out that I came from Charleston, I was immediately promoted to an unofficial research assistant. Armed with a banged-up digital camera and hand-drawn maps on paper napkins, I zigzagged through the Lowcountry, having as much trouble understanding the local Tidewater and Gullah as I did deciphering T’s handwriting, which resembled the death-crawl of a worm. His maps led me through Awendaw and Beaufort, from Georgetown to St. George.

When I heard of his death, my thoughts wandered back to these places of sweetgrass and saltwater, of cottonfields and sharecropper cottages. Writing about Black graveyards of the Carolina Lowcountry in “Flash of the Spirit,” Master T discusses a visual pun found in front of the headstones of Kongo descendants: flowerpots planted upside down, into the earth. This tradition, he writes, stems from the double-meaning of the Ki-Kongo verb “bikinda,” which means both “to die” and “to be upside down.” To be planted into the ground is to grow again—this time toward the realm of the ancestors. Most significant, T writes, is the root of “bikinda”: “kinda,” the Ki-Kongo word for “strength.” The dead grow strong once again as their roots travel through the earth toward the timeless eternity of the ancestors.

T is strong again, strong because he walked to the clave of his heart.

He was a bright light, a bolt of lightning.

He was Àshe incarnate.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Abortion

An old family friend who is voting for Trump fought with my mother yesterday. Stubbornly insisting that of course she was tired of Trump’s unsuitability and immorality—she even nodded towards the fact that there are at least 545 children in cages who may never see their parents again because of the government’s casual cruelty—she argued that all of that was white noise: she had to vote for Trump because of his staunch stance against abortion.

Our friend is not some weird outlier, not the only voter who is willing to make this inhumane bargain. Though Trump and many of his voters are the strangest and unlikeliest of bedfellows, the prospect of overturning “Roe v. Wade” makes what would otherwise be a bitter pill easily and readily swallowed.

But abortion was not invented by the Supreme Court in 1973 and, should “Roe v. Wade” be overturned, abortion will not disappear.

Abortions will continue no matter how draconian Republicans’ restrictions become.

What will change—and change dramatically—is the number of preventable and frequently fatal medical accidents and the prosecution of women, particularly women of color and women without financial means.

Sadly, the well-documented data that prove this are either ignored by the “pro-life” movement or considered an acceptable outcome.

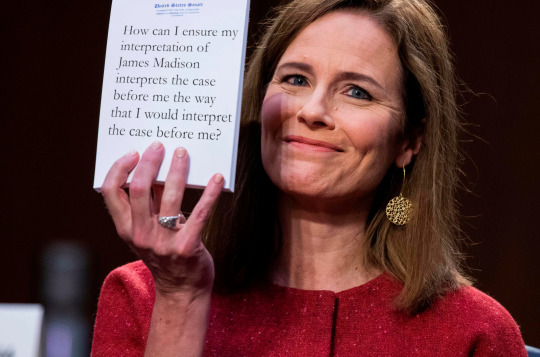

At her confirmation hearing before the Judiciary Committee, Amy Coney Barrett remarked: “When I write an opinion resolving a case, I read every word from the perspective of the losing party. I ask myself how would I view the decision if one of my children was the party I was ruling against.”

Even a cursory glance at Barrett’s judicial record, however, reveals just how hollow these words ring. Unfortunately for the nation, Judge Barrett suffers from the same empathetic myopia that plagues much of today’s Republican party: too few are able to see the world beyond and outside of themselves.*

Too many on the far right, fueled by the gross tenets of Ayn Rand’s selfishness, tend to see themselves invariably as different, as special, as unique. From this distorted perspective, the vicissitudes of fortune visited upon them—unemployment during a pandemic, for instance—are extraordinary and fundamentally different from anything the hoi polloi might possibly encounter. Welfare in such a case as theirs is not an economics of dependency; rather, it is simply a bit of help to bridge the gap.

How might such a short-sighted, empathy-starved person react to an unplanned pregnancy?

Well, look no further than the number of wealthy, “pro-life” conservatives who procure abortions in the reddest of states. The statistics are as shocking as they are not.

So many of our laws and so much of our politics, purported to be black-and-white, contain amounts grey commensurate with income and power.

Even the language of pregnancy and abortion shifts according to one’s familial and financial circumstances:

The poor and powerless are “careless,” but the rich and powerful understand that “accidents happen.”

The poor and powerless are “horny,” but the rich and powerful understand that sometimes people get “carried away.”

A young woman without means must own her mistake and usher in a little life, but a young woman with a powerful father is helped to understand that we all make mistakes sometimes—that it would be unfair to let a single moment of indiscretion derail a life full of promise.

But we should make no mistake: the different worlds of experience following conception would not stop if abortion were criminalized.

For the rich, there are trips across the border: a Danish vacation, a weekend in Mexico.

For those unable to afford such an expense should the doors of Planned Parenthood no longer be open, there are hangers, knitting pins, and catheters flowing with Lysol—sepsis, nephrosis, and death.

Sadly, “pro-life” is just a clever marketing scheme: it sounds better than “anti-abortion” and, as a bonus, the label brilliantly implies that anyone who argues against such a stance must, perforce, be “pro-death.” As a label, it contains within it the extent of its argument.

But, like so many marketing schemes, “pro-life” is misleading and duplicitous! For truth in advertising, one should call “pro-life” instead “restricted access.” In the minds of so many on the far right, abortion should be an absolutely illegal activity—absolutely illegal except for those already well-versed in bending the rules to accommodate their own needs.

If, indeed, those who proclaim themselves to be “pro-life” actually believed all lives to be sacred and equally valuable, the Venn diagram of those opposed to abortions, to capital punishment, to cost-prohibitive healthcare, to drone strikes, to children in cages, and to sterilizations in ICE detention centers would be a circle.**

If “pro-life” voters are serious about their ethical beliefs, they should investigate the well-documented reasons women seek abortions. They might be interested to learn that many women who “choose” to have an abortion do not feel that they, in fact, have a choice.

That’s because a choice predetermined by economic circumstances or by physical and mental health requirements is not a choice!

Knowing that, and if they were serious about their professed ethics, they would be in the front lines agitating for paid parental leave; affordable childcare; universal, cost-free Pre-K education; access to fresh, healthy food; comprehensive sex education in public schools; and restrictions on pollutants and weapons.

But they’re not.

And the politicians they elect proceed accordingly: they care more about exerting control over the bodies of women—particularly over women of color and women without financial means—than they care about life after birth.

Support a woman’s right to choose.

To do that, support policies that make such a personal choice truly a choice.

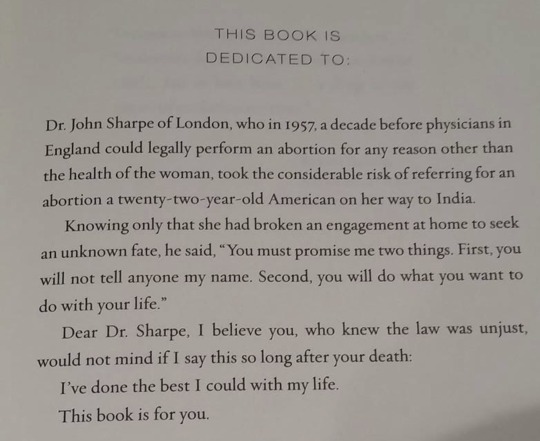

Pictured below is the dedication to Gloria Steinem's memoir "My Life on the Road."

* Some, however, are saved when their eyes are opened by events outside their control. To take Tennessee Williams out of context: “They had failed their eyes, and so they were having their fingers pressed forcibly down on the fiery Braille alphabet” of understanding. Some aspect of their life — unseen and unanticipated on the radar — appears, altering a carefully constructed way of seeing. Maybe it’s a son who comes out of the closet and helps a conservative mother to see and to understand how narrow the confines of her empathy are when compared to her love for him. Or maybe it’s the seemingly ubiquitous epiphany among elected Republicans — “What if that happened to my daughter?” — that nudges them towards addressing workplace harassment and gendered wage discrepancies.

** It is not a circle.

0 notes

Text

Being There

When I was training to become a teacher, a mentor gave me a book about problems teenagers face. The book detailed the types of obstacles and addictions and challenges that teens often feel they have to face alone, issues ranging from anorexia to divorce, from imposter syndrome to a stammer, from test anxiety to parental pressure.

Overwhelming as the book felt, there was, at its heart, one common thread, as simple as it was heartbreaking: loneliness.

Maybe there’s really nothing new in this great big world of ours. Maybe the problems that lap at our feet and begin steadily to rise are troubled waters others have navigated before. And maybe there’s hope to be found in that: people have gone through this and have come out alive.

But when you’re at your lowest, perspective seems to disappear in a puff.

And when you’re fighting something inside of you—when you’re distressed by or disgusted with a part of yourself—the horizon grows dimmer and the world closes in around you. There’s no outside; there’s only inside.

Nobody knows you when you’re down and out.

That book taught me that the most important kindness is simply to be there.To be there to listen. To be there to help pick up the pieces and try again. To be there to see them.

To be there even if it’s just to remind them that you know they are there, too.

I think again of that lesson as Donald Trump and his reelection team have begun to release stolen photographs, text messages, and emails in an attempt to smother the airwaves with scandal. Caught up in this political mudslide is Joe Biden’s only surviving son: Hunter Biden, whose life has been punctuated largely by loss and, lately, by his struggle with drug addiction.

This disgusting smear campaign is the perfect and tragic distillation of the plain meanness of Trumpism.

Trump is so selfish and so narcissistic that he does not understand suffering—at least not beyond how to try to wield it against others. Trump does not know and cannot imagine the ways in which suffering can spread like ripples in a pond around a rock’s impact — as if those who grapple with mental illness are the only ones who suffer because of it! But because Trump cannot imagine anything beyond himself, he has taken a gamble that the American people will react just as he and Giuliani have: by “laughing [their asses] off.”

There is no plainer distinction between Biden and Trump than how they approach someone who feels powerless to his addiction, who feels caught up in a storm not of his making, who shares the struggle so many in our country face. Imagine the pain Hunter must feel; imagine the pressure.

Trump looks at such a personal plight and laughs. He does not perceive a man who needs help, who needs someone in his corner. He sees only an opportunity to try to humiliate his opponent.

But humiliation only works if one can reveal something about which the other is ashamed.

And Joe Biden is not ashamed of his son. There’s no shame, no pity, no anger.

There is only a loving pillar there to help support his son, a proud father who recognizes the difficulty of the fight Hunter faces and the requisite bravery it takes every morning to get out of bed, to stand up, and to fight.

That kind of love, the fierce kind of love that Joe feels for his son, is not an easy or usual love.

And that’s because the loneliness many people suffering from mental illness face is not an easy or usual loneliness. Sometimes it feels so intense as to be lovelessness: "How could others possibly love me?" or "How could someone love anyone who behaves or feels this way?"

People who suffer sometimes build up walls of resistance, forcibly shutting others out and wrapping themselves in solitude. Sometimes they shut even themselves out: their moods or behaviors make them feel incapable of self-love.

When people are at their lowest, it can be hard to love them.

At the end of “A Raisin in the Sun,” Beneatha scoffs at her mother’s request to love her brother, Walter, who has squandered the family’s hopes, dreams, and money:

“Love him? There’s nothing left to love!”

Mama responds:

“There is always something left to love. And if you ain’t learned that, you ain’t learned nothing. Have you cried for that boy today? I don’t mean for yourself and for the family ‘cause we lost the money. I mean for him: what he been through and what it done to him. Child, when do you think is the time to love somebody the most? When they done good and made things easy for everybody? Well then, you ain’t through learning—because that ain’t the time at all. It’s when he’s at his lowest and can’t believe in hisself ‘cause the world done whipped him so! When you start measuring somebody, measure him right, child, measure him right. Make sure you done taken into account what hills and valleys he come through before he got to wherever he is.”

Love is a radical act—an act of defiance, even.

We are better than Trump.

#election2020#politics#trump#biden#hunterbiden#giuliani#depression#mentalhealth#mental illness#scotus#america#usa

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Trojan horse of Originalism

It would be difficult to misunderestimate* just how stupid “originalism” is.

And yet, Amy Coney Barrett claims to believe in such a philosophy: “The text is text and I understand it to have the meaning that it had at the time people ratified it. It does not change over time, and it is not up to me to update it.”

Any American with a basic and clear-eyed knowledge of civic history can recognize just how pedantic and problematic originalism is. The ratification of the Constitution, after all, was not a series of easy agreements: it was rife with disagreement and characterized by difficult consensus. On what did these white men agree? On the enslavement of humans as chattel, on counting Black bodies as 3/5 the value of white bodies, on the demarcations of civil liberties and enfranchisement—just to name a few.

Originalism insists that a judge discard centuries of American history, precedent, and progress – and disregard the silence and the outcries of millions of Americans – and instead make a decision as if one were living in 1787 and not terribly talented at inferring meaning beyond the literal.

Though clothed in the Federalist Society’s finest robes with pretensions of profound scholarship, originalism is, at its core, shallow anti-intellectualism: a failure of imagination and a failure of interpretation.

Unfortunately, like cholesterol and fatty deposits, originalism has sticking power.

That’s in part because its adherents and practitioners deflect any criticism of their judicial philosophy through self-canonization: they purport to be but vessels for the Constitution. To find any fault in their rulings, then, is to find fault with the founding documents of our nation. Its most famous advocates—Antonin Scalia, Clarence Thomas,** and Amy Coney Barrett—even practice a kind of abnegation, stripping away their own agency: though their opinions might be praised for their literary quality,*** the writer is simply a Ouija board through which the Rule of Law speaks.

(This unqualified admiration for the nation’s founders is catnip for the conservative who views himself as a modern Cincinnatus. Mark my words: we are only ten years away from Ted Cruz or Tom Cotton interviewing a hologram of James Madison in a committee hearing to defund Planned Parenthood.)

But, like insufferable answers to interview questions about weaknesses—"I care too much!” or “I work too hard!”—this is a transparent arrogance designed to deflect attention from the reality. Never mind Judge Barrett’s Gertrude Stein-like proclamation that “the text is text”: originalism, though praised for its supposed impartiality and consistency, is nothing more than an uncreative disguise for bald partisanship.

As it is actually practiced, originalism is something like the Great Wall Buffet of jurisprudence: practitioners pick and choose what they want, disregarding whatever it is they find unappetizing at the time, leaving it to linger under the heat lamps.**** Why are some words more equal than others? Why are some precedents ironclad while others are itching to be overturned?

What would Madison or Jefferson say?

Why, whatever Amy Coney Barrett thinks they would say!

One’s subscription to a stupid and hollow belief system presents two options about a person: either they themselves are stupid, or they don’t actually believe what they profess. Republicans have wasted no time assuring Americans that Barrett is extremely intelligent. (For her part, Barrett brought no notes to the hearing to demonstrate her knowledge—and then was unable to name the five freedoms guaranteed by the First Amendment.)

The only logical conclusion, then, is that a very intelligent scholar such as Judge Barrett does not actually believe in originalism, but rather relies upon it to accomplish her political goals as a judicial activist. And her judicial record clearly indicates what that agenda is:

Judge Barrett does not believe in a woman’s right to make decisions about her body and health.

Judge Barrett does not believe that voter suppression is a problem.

Judge Barrett does not believe that affordable healthcare is a right.Judge Barrett does not believe in the state’s recognition of marriage for non-heterosexual couples.

Judge Barrett does not believe that a hostile work environment is…a hostile work environment.

Call your senators and tell them to vote “No!” on Judge Barrett’s confirmation, donate to Planned Parenthood, and phone bank for Democratic candidates in competitive races!

----

* painter/wordsmith/war criminal g.w.b.

** never mind that Ginni Thomas can only leave heavy-breathing, Chardonnay-scented voicemails for Anita Hill because of the Reconstruction amendments and SCOTUS precedent.

*** Michele Bachmann: “Reading a Scalia dissent was akin to reading a Shakespearean sonnet. RIP”

**** in the timeless words of Bill Davis: “Republicans misquote the Constitution like it’s the Bible.”

#scotus#politics#election2020#amy coney barrett#law#Planned Parenthood#roe vs wade#confirmation#hearings

0 notes

Text

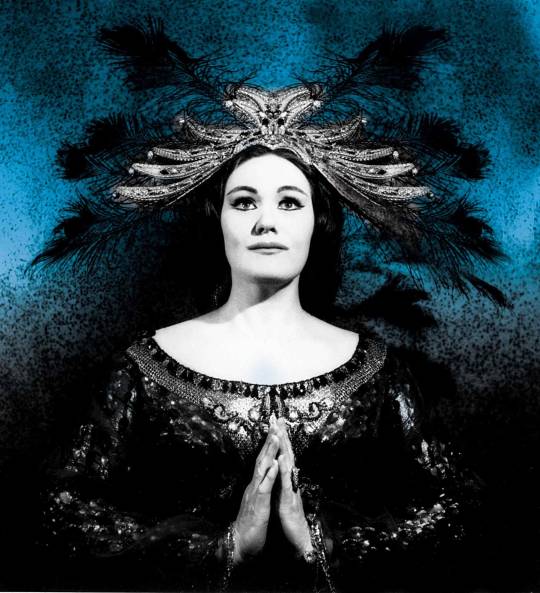

La Stupenda - 10 Years Later

Dame Joan Sutherland, “La Stupenda,” died ten years ago today: 10/10/10. To me, there is no other voice that comes close. Listening to the beauty of her soaring voice today fills me with as much wonder as the first time I heard her E-flat.

With a technique equaled by few and surpassed by none, Dame Joan sang lengthy legato phrases effortlessly, raced through the most complicated passages and runs, and sustained a magnificent trill as no one had before and has since. The size of her voice, best captured in her live recordings, was seismic: not thinning above the staff, but blossoming. Her timbre was golden and round and never harsh.

Dame Joan’s early life bore striking resemblances to an opera: her father died on her sixth birthday after taking her to the beach to enjoy the swimsuit he had given her; her sister, who had long suffered with depression, committed suicide quite young; on the night of Dame Joan’s debut in New York City, she learned via telegraph that her mother had died unexpectedly.

Those tragedies might be heard in Dame Joan’s most serious roles—the heartbroken and betrayed Beatrice, the confused Amina, the crazed Lucia, the noble and lovelorn Gilda. Her mad scenes, farewells, and lovesick arias are among the most beautiful and haunting recordings of opera.

Outside of those roles, however, she was as buoyant as her hair. She was a natural in comedies and light opera. In between “heavies”—what she called “Norma,” “Lucia,” and “I Puritani”—she loved to embrace her lighter side onstage: “It’s for my equilibrium,” she explained to Norma Major. “I die so often.��

She enjoyed needlepointing and playing poker with stagehands in the wings as she awaited her various onstage executions, banishments, and betrayals. She was self-effacing and funny and giggled with the same titanic force she brought to the stage.

Her voice has been an inextricable part of my life since I first began listening to opera. As clichéd as it might sound, I feel as if I hear an old friend whenever I listen to her sing.

Hers was the voice of the century, a singular wonder.

0 notes

Photo

“I heard a Fly buzz -- when I lied --”

Michael Dickinson, the reclusive poet laureate and homophobe of Indiana.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ayn Rand’s Jesus

In one of the few years he paid anything, Donald Trump paid seven hundred and fifty dollars in tax in 2016 and 2017.

The President of the United States, who brags about his billions, paid only $750 towards Medicare & Medicaid, Social Security, the veterans he called “suckers,” and the infrastructure he complains about at his super-spreader rallies.

You paid more.

Your neighbor paid more.

The person who empties the garbage cans on your curb paid more.

And then Trump, citing business expenses such as his hair and his daughter, received a $72,900,000 tax return.

This comes as no surprise, for we have all seen what Trump values, privileges, and cares for: his own family’s* financial well-being. (*void if named “Tiffany”—I don’t make the rules)

What hurts more than the sheer inequality of this is the high probability that he broke no laws in so doing. Rather, he spent many of the millions he has received in loans or refunds to hire some soulless subterranean accountant to burrow through the tax code’s loopholes like some insatiate mole.

Mack the Knife, awaiting his execution, wonders aloud in his damp cell: “What’s picking locks compared to shorting stocks? What’s burgling a bank compared to founding one?”

Bertolt Brecht laments how quickly ethical bedrock can crumble under the appealing pressure of profit. At the faintest whiff of money to be had, the greedy and the powerful will bend the law to accommodate their worship of Mammon. Whenever an opportunity for profit presents itself to the rich and mighty, ordinary people must watch as the gap between what is legal and what is ethical grows larger and larger—grows until the two become distinct beasts.

But one needn't worry about this damning divergence: what Ayn Rand preaches and what Republican-Jesus teaches is that making money is far more important than your neighbor—and your soul.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Meritocratic Trap

One’s ability to perform a particular job is the baseline requirement for any employment — not the alpha and the omega.

Yet a major delusion in today’s politics is that the mere presence of qualifying credentials is somehow enough to mitigate real concerns about politics, character, and suitability.

A pure meritocracy, a society in which people hold office based solely on their ability, is a nightmare. Like utilitarianism, a pure meritocracy might sound appealing in the abstract — until one considers that there is a lot more to every job than prerequisite qualifications and credentials.

After all, plenty of people have the right degrees from the right institutions and have checked the right boxes among the right circles. Ted Cruz received a degree from Princeton, but that degree did not magically bestow the gift of transubstantiation, converting a walking pustule into a saintly man. Rather, it simply took a garden-variety asshole and made him into a credentialed asshole.

Or take Bart Kavanaugh, who did everything a college counselor might advise a student to do: graduated near the top of his class in high school, applied and got into Yale, leveraged connections to attend Yale Law School, clerked for Kennedy, worked in the White House.

To be sure, Kavanaugh was qualified to be nominated to serve on the Supreme Court of the United States.

But all the qualifications, credentials, and perfumes of Arabia could not make Kavanaugh a man worthy of power.

Amy Coney Barrett is likewise qualified to be nominated to serve on the Supreme Court.

The only consideration worth the precious little time we have left before Mitch McConnell railroads this nomination through is what Judge Barrett has chosen to do with her qualifications. And a survey of that makes it clear that Judge Barrett has leveraged her qualifications to take the United States backwards, away from justice and equality

.My family taught me that good people were those who punched up: who fought to protect those who were forgotten, ignored, manipulated, silenced, or abused by the big and mighty.

The judicial record of Judge Barrett reveals someone who prefers to punch down. In this article, Nathan J. Robinson took on the unenviable task of wading through Judge Barrett’s odious rulings and dissents. He outlines the many and diverse reasons why Judge Barrett, while eminently qualified for the job, fails to meet any sort of ethical, moral, social, or empathetic standard to hold a chair that will disproportionately affect the arc of American policy. Her rulings and dissents have focused like a laser on the powerless: on the poor, on immigrants, on the wrongly imprisoned, on the uninsured, on the un-organized employee, on debtors, on African-Americans, on Latinos, on the LGBTQ+ community, on the women fenced in by draconian and inconsiderate regulations.

Punching down is cowardly. It is what small people do to feel big. It is wrong and it has no place in the America I want for my children and students.

The Senate should vote down the nomination of Judge Amy Coney Barrett.

0 notes

Text

Cancel Kavanaugh

Plus ça change, plus c'est la même chose:

Two years ago today, Dr. Christine Blasey Ford and then-Judge Brett Kavanaugh testified before the Senate Committee on the Judiciary.

Brett Kavanaugh’s reflexive defensiveness — “Do you drink too much?” in response to Senator Klobuchar’s questions about his drinking — reeks of the delusional alcoholic unwilling to admit that he has a problem, convinced that the problem is one manufactured by those who simply don’t understand or know him.

His petulant behavior—smarmy, bellicose, privileged—his refusal to answer questions, and his bald attempts to manipulate the already-farcical time restraints represent the worst of what the insularity of childhood education can provide: a world in which one can sail through without ever being questioned or checked or asked to be a half-decent person.

He is so accustomed to sitting pretty and unchallenged in all he does that he honestly and fervently believes we are stupid enough to believe that his yearbook note “Renate alumnius [sic]” is not sexually charged.

He is so arrogant that he can say, with a straight face, that being a “graduate” of a girl named Renate was not a joke among guys to make her seem loose, easy, or “slutty.”

This type of sexual shaming is the tip of the iceberg; it is a malignant tumor, not some sideshow.

Plain and simple, Brett is an unctuous ass. Watching him play the martyr while peddling horrendous theories—Clintonian revenge, e.g. — is sickening. He is lying about his drinking, just as he has lied about his credit card debts, his personal debts, his mortgage, his White House work, his connections to Trump’s lawyers, and his willingness to use illegally obtained opposition research.

If a man will lie about all that—and sit there smugly with beautifully blooming gin blossoms despite all the evidence to the contrary—why wouldn’t he lie about the ultimate act of selfishness? Why wouldn’t he lie about the ultimate act of privilege—that what’s yours is mine, no matter what you may think to the contrary? Why wouldn’t he lie about the solipsistic act of sexual assault?

I believe Dr. Christine Blasey Ford. I believe that Brett Kavanaugh is a dangerous liar.

A morally bankrupt Supreme Court is a threat to the Republic.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Shame, shame, shame.

Hypocrisy rankles only those capable of shame. For Mitch McConnell, there are no principles that check power; there is only power.

When my sister and I were little, our mother liked to tell us the story of an old schoolteacher who lived with his students in a run-down temple. One day, the walls of the temple began to crumble, so the wise schoolteacher gathered his students and told them that he had devised a plan: the students should go to town and steal money so that they could afford the necessary repairs. The schoolteacher assured them there was no need to worry about the morality of such an act—provided that each was exceedingly careful in ensuring that no one witnessed the theft.

The students returned one by one to the temple, each with pilfered goods and stolen money. All but the last student, who showed up empty-handed. Her peers looked at her with disdain: did she not care about the temple and their teacher? When the teacher asked her why she had not stolen, she responded simply: “You told us not to let anyone see us steal. But whenever I tried to steal, I saw myself.”

The teacher burst into tears and embraced her, for she had understood all he had taught.

My mother wanted my sister and me to know that what we do and what we say determine what we see in the mirror. If we want to like the reflection staring back at us, we should be sure that our actions and words are not the sort that distort, mangle, or warp what we see or want to see. While we learned at church that no one could hide from an omniscient God, our mother taught us a secular truth:

We cannot hide from ourselves.

But this parable always came with a familiar reminder: life is neither fair nor a fairytale.

Some people, after all, gaze into funhouse mirrors of morality, which—with a little willpower and a lot of self-deception—can show us not as we are but as we want to seem. These warped mirrors stretch lies into truths, flatten unconscionable actions into justified behavior, clothe base beliefs in dignified dress. The relentless mental gymnastics of rationalization, however, take their toll; inconvenient truths stubbornly refuse to stay subsumed forever. These wishful gazers may one day see themselves as they really are and must reckon with what they see.

But there are those who simply cannot care less what they see in the mirror. They change positions like a kama sutric weathervane, they betray their friends, their dastardliness beggars belief. They shrug at their own words, they care not for their own promises.Because what cares Mitch McConnell today what Mitch McConnell said yesterday—what good has a conscience ever done him? As Falstaff asks:

"Can honour set to a leg? no: or an arm? no: or take away the grief of a wound? no. Honour hath no skill in surgery, then? no. What is honour? a word. What is in that word honour? what is that honour? air. A trim reckoning! Who hath it? he that died o' Wednesday. Doth he feel it? no. Doth he hear it? no."

Does following a moral compass pack courts with Federalist Society drones and Bircher bees?

Does any sort of ethical code dismantle the safety net or cut taxes?

No.

And Mitch McConnell has hundreds of concerns that weigh infinitely more heavily than something as impractical as honor.

Democrats need to stop showing up to Congress like it's a Debate Tournament In Ladson, South Carolina with handshakes, time limits, and evidence-based determinations. Expecting the Majority Leader to honor his own words is like expecting Lucy to hold the football steady.

To quote the great American poet: “There’s an old saying in Tennessee—I know it’s in Texas, probably in Tennessee, too—that says, ‘Fool me once… shame on… shame on you. Fool me.... You can’t get fooled again!”

0 notes

Text

RBG

“I had it of Leah when I was a bachelor,” Shylock remarks upon hearing that his daughter had traded away his treasured turquoise ring. “I would not have given it for a wilderness of monkeys.”

Despite the caricatured and antisemitic ugliness of Shylock throughout “The Merchant of Venice,” this exchange is a tender and heartbreaking moment, unique in that the value of this singular object lies not in its price but in its emotional weight. Though the ring might have been worth a monkey to some stranger in some foreign bazaar, the ring was dear to Shylock because it symbolized Leah, his dead wife. In many ways, Leah’s gift was a synecdoche—one small part of Shylock that stood in for something much larger: his heart.

In her letter to my class, Ruth Bader Ginsburg points out the strange syntax of Shylock’s despair: “’I had it of Leah,’ instead of ‘Leah gave it to me.’” But what a large difference such a small change makes! While we might associate “of” most frequently with possession or belonging, here Shylock emphasizes that the ring was quite literally “of” Leah: a part of her, the only tangible piece of his beloved wife that remains. The ring, then, is representative not just of Shylock's heart, but also of Leah: his love for her, hers for him, and their life together.

This careful and heartfelt reading was no surprise from someone as thoughtful as Justice Ginsburg, whose beautifully written opinions dispelled any notion that Supreme Court cases were about arcane rules and regulations. Rather, each case before the highest Court was, in her eyes, about the lives, livelihoods, and humanity of men and women across the United States. She believed in and fought for a more inclusive “We the People,” from her years in law school—in which every single class was an act of defiance for a Jewish woman—to her final days on the Supreme Court.

“Justice,” to Justice Ginsburg, was a hopeful thing and an aspiration. She was the opposite of a “strict constructionist,” for she knew that true justice was something better than what we had when the Constitution was written and better than what we have now. She believed that our amendments help us to make amends: to correct the wrongs of the past, to fix that which is broken. In so many ways, Justice Ginsburg embodied that ideal of justice in her courageous and oftentimes lonely dissents, her unrelenting standards for her own work and that of others, and her undying fight for equal protections and benefits for all.

She was a colossus and a firebrand, a role model and beautiful human. And she was patient and kind: she took the time to read and answer my letters, sharing her thoughts about Strauss’s operas (her dream role was die Marschallin in “Der Rosenkavalier”) and Shakespearean justice (she wanted Hamlet to be tried for his role in Ophelia’s suicide), about voting rights and gay marriage. Tonight, I will listen to “Der Rosenkavalier” and enjoy a little too much red wine—just like RBG at the State of the Union.

I have these letters of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, whose influence upon our country is indelible. I will miss her very much.

0 notes

Text

The “Mississippi Appendectomy”: Racism and Sterilization

One of the most powerful pictures from the Civil Rights era is one of the most haunting: an exhausted Fannie Lou Hamer sits on a trunk in her Mississippi home; her glazed eyes—scarred still from a policeman’s nightstick—look away from the camera, towards someone outside the frame. Next to her is a white doll baby, its limbs uncannily positioned, whose perfectly round eyes stare directly at the lens.

The doll baby is perfect: she is never exhausted, her hair never mussed, her feet never blistered, her hands never calloused from cotton plants. The doll baby is everything that any young girl should want: a perfect little someone of her own to look after, nurture, and care for.

Early on in “The Bluest Eye,” a young Claudia receives a Christmas gift she hates: a white doll not unlike the one pictured with Hamer. Her parents gave it to her expecting that it would fulfill her every wish; looking back on her disappointment and disgust, Claudia observes: “Adults, older girls, shops, magazines, newspapers, window signs—all the world had agreed that a blue-eyed, yellow-haired, pink-skinned doll was what every girl child treasured.”

What the world does not treasure, Claudia soon learns, are doll babies and real babies who do not resemble Shirley Temple or Jane Withers—doll babies and real babies who look like her.

For what plunges this photograph vertiginously into horror is the void that the white doll baby symbolically exposes. At the North Sunflower County Hospital a few years before this photograph was taken, Fannie Lou Hamer sought treatment for a simple ailment. While Hamer was unconscious, her doctor performed a hysterectomy without her knowledge or consent.

Fannie Lou Hamer went to the hospital for help; she came out sterilized.

I thought of this photograph as I read about the appalling crimes at ICE’s Irwin County Detention Center: a doctor known as the “uterus collector”; confused and powerless women violated by authority figures in white coats; medical personnel relying upon Google to convey basic health information across a language barrier. If it were not for the actions of a brave whistleblower, Dawn Wooten, these eugenic crimes would persist unchecked and unseen.

These crimes are just the latest example of eugenics in the United States—an evil history that stretches from Fannie Lou Hamer’s “Mississippi appendectomy” to the sterilization of thousands of Native women by the Indian Health Service. What undergird these crimes are pervasive racism and an intoxicating sense of power—which, in feeding one another, are inextricable from each other.

In her book “Sexuality in Europe,” the historian Dagmar Herzog writes: “[R]acism of any kind has necessarily always been also about sex.” To explain her thesis, Herzog highlights how the Nazis restricted contraception and abortion for those women who might produce “desirable” children—such devices and such procedures, they claimed, were immoral and disgusting—while they simultaneously sought to eradicate “undesirable” children through sterilization and involuntary abortions. Racism, she suggests, helps explain the inherent contradictions of far-right stances on birth control—a hypocritical discord that might be summed up simply: “Not all lives matter.”

After all, when one maintains a staunch “pro-life” stance yet defends or remains silent in the face of forcible sterilization, we must ask: is it life that this person cares about? Or is it the control that they wield over the bodies of women of color, the control that they maintain over life and death?

(Spoiler alert: it’s power they care about.)

Donate to RAICES here.

Donate to Planned Parenthood here.

0 notes

Text

Memory and Vengeance on 9/11

9/11 remains too painful to parse. The staggering horror haunts us: men and women—anxious to escape flames, suffocation, the agonizing wait for the furiously loud inevitability—cartwheeling through space towards the pavement and into eternity; fellow commuters emerging from subway tunnels only to evaporate under falling beams; voicemails and dial tones punctuating the caller’s life, their love, their imminent loss. The death toll continues to climb today, almost two decades later: lungs of survivors and first responders succumb to the toxins of fire retardant; past trauma overtakes the distractions of everyday life and people cannot go on.

Of the many faces and names I saw and read in the weeks and months after the attack—we were loading our backpacks in Ms. Settle’s homeroom; when she turned off the VCR, the television input automatically switched; we saw the smoke but didn’t understand—one face and name made something so abstract and terrifying and confusing into something concrete and heartbreaking. Asia Cottom was my age—she had turned 11, I was still 10—and she loved Tweety Bird and science class. I found her picture in “National Geographic” a month after the attacks. As a budding young scientist, she had won a trip to California to study ecology, and there she was in the issue's appendix in a picture her parents had taken of her at the airport.

Her plane crashed into the Pentagon later that morning.

I think of Asia Cottom each year on September 11th.

But 9/11 is more than the tragedy of a single day; 9/11 is a nexus of loss. In a single morning, we lost so many mothers and fathers and sons and daughters and coworkers and students and teachers, but, by the evening and in the following days, amid the clangorous calls for vengeance, we stood the risk of losing something else entirely: our humanity and our decency.

Vengeance, according to the poets, is the great equalizer: within its very act lies the ability to erode or erase the distinguishing characteristics that separate wrongdoer from victim. Embracing the sordid boon of expedient and ruthless retaliation, we rushed—accompanied by great zeal, unburdened by scrutiny—into an era of perpetual, indiscriminate war.

Our government rebranded “torture” as “enhanced interrogation”; a private military contractor—to which many government officials had extensive financial ties—rebranded so that news reports of their slaughter, torture, and humiliation of innocent civilians would not hamper business; our president called the invasion of Afghanistan a “crusade”; we created new departments of government to surveil, antagonize, and punish citizens and residents, at home and abroad.

We fetishized the killing of Muslims in video games, television shows, and blockbuster movies; radio stations nationwide played Toby Keith’s ode to Hellfire Missiles and Islamic blood ad nauseum; American citizens burned down the mosques of their neighbors and shot Sikhs, guilty of wearing turbans, at gas stations; we dispensed with any need for evidence to justify invasions, bombings, and drone strikes—scenes from Michael Bay’s “The Rock,” starring Nicholas Cage, were mislabeled and used as “evidence” to justify the invasion of Iraq.

Reckoning with these moral failures is the labor of a lifetime, but particularly essential work today, when tragedy and heartbreak, undiminished by time, feel fresh and raw—when renewed anger feels just a heartbeat away, when the calls for continued vengeance arrive tweet after tweet.

Today, I reread an article that Mrs. Chanson, my eleventh grade English teacher, highlighted at the beginning of the schoolyear in 2007: “The Black Sites,” an expose by Jane Mayer about torture, interrogation, and the banality of evil. I encourage you to do the same.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Labor Day

Nikki Haley tweeted this morning that Labor Day is about the “core of America—the good-hearted, hard-working folks who don’t ask for much yet do more than what’s asked of them.”

This is dangerously (and unsurprisingly) wrong: Labor Day is about fighting the ubiquitous bourgeois mentality that the good worker is she who doesn’t ask for much. The mentality that, the moment that worker raises her voice, she ceases to be “good-hearted."

At a party celebrating the end of the school year, a head of school pretended to choke up talking about a retiring legend who had given decades of his life to his work and to his students. The treacly affectation was obvious—the head barely knew the teacher and, indeed, hadn’t bothered to get to know him—and his remarks were accordingly quite vague with one exception:

What had made this math teacher so excellent, the head claimed, was that he had never complained about his work and had never asked for more.

What a cheapening statement! Imagine working for half a century only to be praised as an unquestioning workhorse who was content with his lot. Imagine listening to a tribute to your teaching as it becomes a clumsily passive aggressive attack against your colleagues: “Why can’t y’all behave more like him?”

My colleague and friend deserved better.

On this Labor Day, we must remember that work conditions stay the same when workers don’t speak up. Asking for equal treatment, for a living wage, and for a seat at the table is not asking for much—it’s just asking for decency.

Agitate. Organize. Unionize.

As Rosa Luxemburg said: “Workin' 9 to 5, what a way to make a livin' / Barely gettin' by, it's all takin' and no givin' / They just use your mind and you never get the credit / It's enough to drive you crazy if you let it.”

1 note

·

View note