Text

Zeus & Hera

#a lil something for theogamia#zeus#hera#greek gods#hellenistic polytheist#theogamia#greek mythology#hellenic polytheism#more on my patreon page#zeus greek mythology#hera greek mythology#digital art#illustration

74 notes

·

View notes

Photo

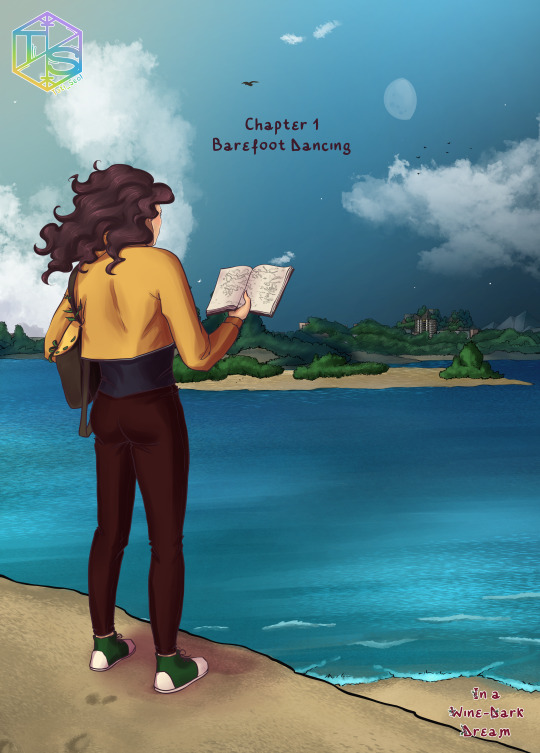

Dionysus’ journey begins

Missed Episode 3 of In a Wine-Dark Dream?

Read it here: https://www.webtoons.com/en/challenge/in-a-wine-dark-dream/list?title_no=619872

#dionysus#dionysus greek god#greek myth#greek mythology#greek myth retellings#greek gods comic#no one asked but that big bird is the eagle of zeus#it's important for the plot#webtoon canvas#webtoon

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

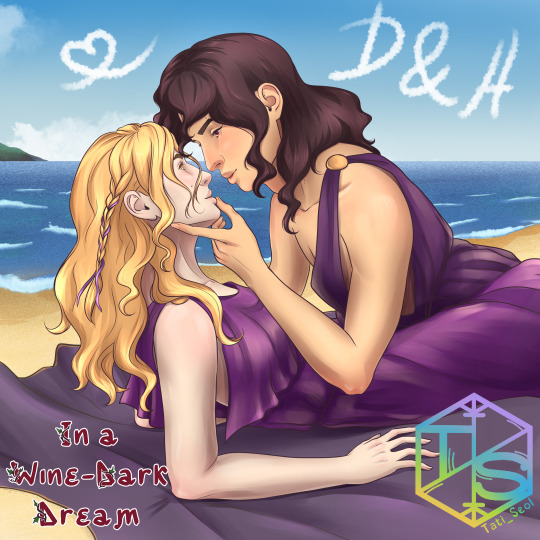

Dionysus x Ariadne

from Episode 3 of my comic, In a Wine-Dark Dream

Read it here: https://www.webtoons.com/en/challenge/in-a-wine-dark-dream/list?title_no=619872

#dionysus x ariadne#dionysus#ariadne#greek gods#greek gods comic#greek myth retellings#greek god#greek goddess

41 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Classic Dionysus VS Modern Dionysus

#drawing Dionysus is self-care#Dionysus#dionysus devotee#devotional art#hellenic gods#hellenic polytheism#hellenistic polytheism#greek gods#dionysus greek god#dionysus deity#bacchuss

240 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Classic Hermes VS Modern Hermes

#hermes deity#devotional art#hermes#hermes greek god#greek god#hellenic polyhteism#hellenistic polytheism#greek mythology#hellenic gods#hellenic pagan

52 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Selene’s Midnight Rendezvous

#Selene#selene greek goddess#Greek Mythology#greek goddess#greek myth#greek gods comic#webtoon canvas#can't wait to show her in the episodes

0 notes

Text

I am no classicist either, but I’ll elaborate on this and touch on some other things we often ignore when reading Greek mythology. Most of us treat it as if Greek Gods and Greek mythology are one and the same, but the connection itself is not that simple.

What are the sources?

We push every written piece roughly from 800 BCE to 500 CE under the umbrella of “Greek Mythology”.

And I mean, every single piece.

It’s a huge chunk of time (1300 years!), with different cultural and political situations. We don't think the same as folks from 1920s, why do we assume people from the 5th century CE would have the same views and values as people from the 8th century BCE.

Not only this, but we start to judge Gods on comedies, on satires, on tragedies, on all kinds of pieces of fiction. Yes, some of these were written by actual practitioners of Greek religion (who knew what their Gods were and were not), but somewhere on the way we all got very unlucky and the most popularized versions of myths turned out to be by a Roman guy who just wanted to cash out on lewd (and sometimes very gross) stories.

Also, people usually read (or watch) summaries. And here's the thing. Summaries are mostly based on that Roman guy's versions.

Moreover, there is this another guy, who had enough confidence to write "Read only my retellings of myths". Guess what? We do! I've seen tons of summaries of his versions and they're treated like the only versions in existence.

If you read his versions of myths side by side with earlier sources, you’ll quickly start to guess what he wrote in the other myth retelling.

Theoi website is very good for this since they have a lot of sources and fragments sorted by a specific theme and divine figure.

Villains vs Antagonist

Greek Gods were never villains in mythology, but antagonists. (Well, maybe except for Typhon). There’s the whole Hero-God antagonism, to the point of a hero looking very similar to the God they’re antagonistic with. Like Achilles and Apollo, Odysseus and Athena, Pentheus and Dionysus, etc.

So, in modern terms, they were partially just a plot device to make a “human” into an actual Hero. And, of course, into a cult hero, because they were worshipped, even though not on the same level as actual Gods. And often they were worshipped alongside the God/dess they were antagonistic with. We wouldn’t expect this if one party was a villain, right?

Even our perception of Hera as a jealous wife, who had to deal with her husband’s affairs, crumbles, when we think about her actions as a making of a Hero. We wouldn’t have so many heroes if it wasn’t for her. And heroes were a major part of Ancient Greek culture. I dare to say, without heroes Greece as we know it wouldn’t be the same. Heroes were kings and queens, skilled warriors, initiates of mystic cults, founders of nations. But would’ve they become as great if they had all the glory from the beginning? Or it’s thanks to Hera they overcame their obstacles and became Heroes?

Symbolism

We, as most of us are not Ancient Greek speakers, missing a lot of symbolism.

There's a very common theme of making everything catastrophically wrong in myth, so we, as practitioners of religion in Ancient Greece (or modern practitioners now), would do everything right in real life. Every word and every action was so carefully chosen to reflect a mystic ritual, or even a common religious or social practice, without spelling out that it is, in fact, a ritual. While we treat it like stories, that thanks to these extreme metaphors and analogies can get really weird, a practitioner, especially initiated in a mystery cult, would treat it like a secret code. Why they did it this way? I don't think we'll ever find out!

Homeric Hymn 2 to Demeter, the one with the actual story about Demeter, Persephone, and Hades, is an example of it. It was a part of their mystery cult (Still is, if we assume the cult was operating without being public throughout the centuries, which is a possibility, and people reconstruct it in modern times, too). When we start looking for the meanings in it, we can easily see that it’s such a multidimensional story.

It's cultural, as a marriage of a girl was often tied with death and lament. It also can be viewed as a mother's attempt to deal with the sudden loss of their child. It can be interpreted as agricultural seasonal change, even though we tend to forget that actual seasons also exist in this pantheon. And it can be viewed as a romantic story, because love, especially the tragic one, is such a common theme in ancient Greek literature.

It can be extremely empowering, both from Demeter's pov (as a mother who fights back for the right to see her daughter after she got married. Again, cultural thing), and Persephone's pov (as a woman who turns a questionable or bad situation to her benefit).

We can interpret this story as the worst possible thing happening, or as the best story ever. Just don't forget to give the same treatment to other myths as well, okay? It’s really not cool when people choose the best version of the myth (or even invent one) for one God, because it fits their interests, but then decide to choose the worst versions of myth for another God, just because.

Another thing to add here is that this particular myth centers around Demeter. Her feelings, her stress, her wanderings, her love for her daughter. Not around Hades, not around Persephone, or at least not to a degree in which we can sweep Demeter away as some background character that stands in a way of true love. Well, we can, but should we really?

I can’t stress enough that we treat the myths as literal most of the time, ignoring the fact that Gods are not... Physically humans? They’re not corporeal. Which is a hard concept to grasp since they are personified in myths.

But there's this myth, for example, where Olympian Gods carry twenty (or twelve) daughters of Asopos away from him and "marry" them. But... Asopos presided over two huge rivers both called after him, and technically he was a literal river, a geographic place, not a human. His daughters are the smaller rivers that stem from him. And the whole act of "marriage" is just people founding cities in the banks of these rivers with certain Gods as their patrons. In one of the myths surrounding this, Zeus specifically throws a lightning bolt into Asopos who tries to get one of his daughters back. Is this a king misusing his power or a God of order taking action against something that tries to prevent an establishment of a city? Is it a description of natural phenomena, in which a river was averted from its unintended course by a bolt of lightning?

Should we call out a God for literally being a patron of a city? I doubt it.

From this perspective, it’s okay for us, in general, to not get it. When we read a myth for the first time there is no way we would know what it refers to, what its hidden meaning is, or who those people in the myth actually are. Especially, when the most obvious meaning for us reading the translations is not the one that was intended in Ancient Greek.

But it’s not okay to attack Greek Gods and especially their followers based on myths, the meaning of which we, as individuals, might not understand completely.

Gods’ domains

Greek Gods are multidimensional and not just cookie cutters of their domains. In fact, no Olympian has strict one-domain boundaries. (I can't say all Greek Gods, because there's too many of them and I bet some actually have more or less strict boundaries)

So it’s really hard to say Artemis is wild and ruthless because of this one domain she rules over. Apart from nature, she's also the Goddess of childbirth, of all things related to womanhood (except the lewd stuff).

But she can be angry and ruthless nevertheless, because she, even as a goddess, has feelings and consciousness. (Depending on your religious views, this still holds true both to Ancient Greek literature and to religion itself)

Compare her to Pan, a God more closely identified with nature and often described as wild and panic-inducing, but in 90% of myth he's... Kind of just there, playing on his pipes or flute (and chilling with Ekho). Shouldn't this difference show us that Artemis' wrath in myth is there for a reason that we need to figure out? Sure, some stories may be cautionary tales of not going too far into the woods, but we can’t expect every single story about Artemis’ wrath to be about nature’s destructive powers.

Another problem is when we constantly dilute Artemis to a wee lesbian, Apollo to a femboy who writes bad poetry, Dionysus to a drunk party animal, Aphrodite to a vain beauty, Hades to a sad soft goth boy, and so on. We then get exceptionally surprised to find myths where they show not only their wrath but just any sort of emotion or action that doesn't fit this box we put them into.

(Next point is kind of reaching, but it’s fun to think about)

The timeline

If we chose to judge Gods on myths (because that's what we, as casual people, have access to) we're also missing an important aspect of the timeline. We can argue that it doesn't exist, but it’s there for us to decipher.

There are two major points that people are missing when talking specifically about how awful Zeus is, but they also concern other Gods in general.

Firstly, yeah he doesn’t do the baby-making thing anymore. Moreover, Gods stopped falling for mortals altogether for a reason. Aphrodite along with Eros used to make every God and Goddess fall for mortals, but there's a myth in which she finally fell in love with a mortal herself. Why? Because Zeus had enough of this whole falling-in-love thing. Yeah, the same Zeus people love to hate on for being "too affectionate". Thanks to this, Aphrodite realized that it's really not fun to fall in love with a mortal so she promised to stop making Gods and Goddesses fall for humans. (Hint: it happened before the Trojan war) (It's from Homeric Hymn 5 to Aphrodite. Very beautiful stuff and interesting to read too)

So, it’s really up to us to decide how to treat the myths about Gods’ mortal lovers after the Trojan war happened. Were they just made up so a person can look cooler as a king? (Looking at you, Alexander the Great) And if they weren’t, what about Aphrodite’s promise? We all know that nothing good happens when a God or a mortal breaks their oath. Is there maybe a deeper symbolism for this that we don’t notice because we read these texts as literal?

Secondly, there's this goddess called Ate. She's a personification of delusion, error, rash decisions. In Illiad, it is said that she is a daughter of Zeus, while Hesiod calls her the daughter of Eris, no father mentioned.

She had the power to lead both men and Gods down the path of ruin. When she tricked Zeus into making an oath that screwed Herakles' future, he realized what is she capable of and banished her from Olympus. Do you know what that means? Illiad spells it out. Olympians used to be rash and making mistakes, but not anymore (or at least not to a catastrophic degree). And since this was mentioned in Illiad, we can place Ate’s banishing somewhere before the Trojan War, and after the birth of Herakles. So all the rash things and bad decisions happening during and after this were either caused by us, humans, because Ate is now with us, or we had much less catastrophic things happening with Gods, because, again, they still have their own interests and desires as conscious beings.

Conclusion

Greek Gods can be whatever we want them in myth and retellings because we write them. So wouldn't it make more sense to say "This Roman guy sucks because he wrote such and such" instead of "This God/dess as a whole is bad (because of a few popular pieces that were written about them)"?

Judging a divine figure only by their domain or by the stories written about them without a full understanding of the purpose of these stories, and without consideration of historical and cultural influences on them, has little to no sense.

Even across Greek Mythology as a whole, there are sources that portray Gods and Goddesses with generally bad domains, as forces of justice, punishing those, who were indulging in the things they preside of. (Like a vase painting of Hybris, the goddess of insolence and excessive pride, where she was portrayed dressed as a Maenad, and described as an avenging spirit driving Dionysus to punish the hubris of men: https://www.theoi.com/Gallery/N21.1.html)

I’m not a classicist, but I suspect one of the reasons so many of the Greek gods are portrayed so unflatteringly was less because they were seen as villains than because they represented their domains. Of course Zeus sometimes misuses his power, that’s what a king does. Of course Artemis’s wrath is wild and painful, that’s what nature can be. Of course Hades snatched away a young girl from her mother’s arms, that’s what death does. This is one of the reasons callout posts for some gods comparing them negatively to ‘nicer’ gods are kind of missing the point.

#greek mythology#greek gods#hellenistic polytheism#hellenic gods#hellenic polytheism#hellenic pagan#zeus#zeus deity#artemis#aphrodite#demeter#persephone#hades#dionysus#apollo#hybris#ate deity#oh look i cant express my thoughts without writing a whole essay#i hope you know the authors i mentioned cuz I'm not gonna tell you their names#im sorry i read too much ancient greek literature and cant shut up about it

148K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Classic Apollo VS Modern Apollo

According to my calendar today is Apollo’s birthday (Thargelion, 7th), so here’s a new drawing of him, in my current style.

You can buy both as a print here: https://www.teepublic.com/user/tati-seol

#apollo deity#apollo#Apollo Devotee#hellenic gods#hellenic pagan#hellenistic polytheism#hellenic polytheism#greek god#greek mythology#olympian gods#i can't wait to put it on his altar#I feel bad for not drawing Artemis yet but I posted her design on insta yesterday

84 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Persephone And Hades

Read In a Wine-Dark dream here: https://www.webtoons.com/en/challenge/in-a-wine-dark-dream/list?title_no=619872

#Persephone#Hades#persephone x hades#kore#greek mythology#greek gods#digital art#webtoon canvas#illustration#i told you Im not going for the stereotypical representations of the gods#in a wine-dark dream

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Dionysus x Ariadne (from Episode 1)

Read In a Wine-Dark Dream here: https://www.webtoons.com/en/challenge/in-a-wine-dark-dream/list?title_no=619872

#Dionysus#Ariadne#maenads#bacchus#greek mythology#greek gods#in a wine-dark dream#webtoon canvas#webtoon#comic page#digital art

83 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Dionysus And Ariadne

Read In a Wine-Dark Dream here: https://www.webtoons.com/en/challenge/in-a-wine-dark-dream/list?title_no=619872

#Dionysus#Ariadne#dionysus x ariadne#bacchus#greek mythology#greek gods#mythology#digital art#my art#webtoon canvas#illustration#in a wine-dark dream

93 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In a Wine-Dark Dream

Do you like Greek Mythology retellings but tired of constant stereotypical portrayals of the Gods? Annoyed that Ares is always the villain? Exhausted to see Demeter as a helicopter mother, vain Aphrodite, unattractive Hephaestos, and not to mention the media’s favorite opinion about Zeus? Want to see more of Hestia, or, maybe even the Titans?

Then “In a Wine-Dark Dream” is a comic for you!

It covers the stories of all major Gods with a focus on Dionysus and his ultimate journey from the underdog to the Olympian.

I based this story not only on the mythology, which is too broad of a term anyway, but also on some archeological finds, religious views from Hellenistic Polytheism, and my personal understanding of the Gods.

You can read it on Webtoon Canvas here: https://www.webtoons.com/en/challenge/in-a-wine-dark-dream/list?title_no=619872

This story is mostly my love letter to Dionysus, who appeared in my life when I needed him most. The least I can do is to write a story about him that doesn’t make me, as a Hellenistic polytheist, cringe.

#I hope you read it in 50s advertisement voice#Also its Dionysia ta astika and i just had to throw this story into the world during this festival#Dionysus#Greek mythology#hellenistic polytheism#Ariadne#dionysus x ariadne#greek gods#webtoon#webtoon canvas#in a wine-dark dream#new comic series#bacchus

107 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Pride Month!

Here is a selection of posts I’ve made on topics pertaining to LGBT+ history. Bear in mind that some of these were written quite some time ago, when I was less well informed than I am now, and I might word them differently in hindsight. I hope they’re still interesting enough and show that LGBT+ people existed in the ancient world too.

On Gilgamesh and Enkidu’s relationship

Homosexuality in the Ancient Near East (including a link to a conference)

Lesbian and bisexual Ancient Greek poetry

An Ancient Greek transgender person (cw: potential misgendering due to contradictions in how the person refers to themself)

Inanna’s genderqueer priesthood

How to write your name in cuneiform as a nonbinary person

Artemis as an aromantic asexual in ancient texts

For the Ancient Near East specifically, I highly recommend @mostlydeadlanguages who has a queer history tag full of interesting content.

Also, here are a few novels set in the Late Bronze Age, and one in the Iron Age, which feature same-sex attracted characters. Sadly, I’m not aware of any with characters of other LGBT+ identities (let me know if you have some recommendations!). Note that I haven’t read all of them, so I can’t vouch for their quality.

The Troy series by David Gemmell (two women, one man)

The Boudica series by Manda Scott (apparently multiple men)

The Song of Achilles by Madeline Miller (two men)

Circe by Madeline Miller (multiple men)

I The Sun by Janet Morris (two men; cw for sexual abuse of women)

The Amazon Chronicles by Jane E. M. Robinson (apparently at least one woman)

154 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! There is a question about the cult of the Greek gods I wanted to ask. Beyond the 12 Olympians plus Persephone and Dionysus, the other gods weren't given much attention or temples, right?

Oh no, they definitely were!

I think one of the big misconceptions people have about Hellenic polytheism is that it is functionally dodekatheism*, that is, the worship of twelve deities. The Twelve are portrayed as central to the religion, with all others being less significant or even forgotten. But this overlooks several elements of Ancient Greek cult.

The first is that, even in Antiquity, nobody could quite agree on who the Twelve were. Was Hestia among them? Was Dionysos? Was Herakles? A lot of the time, “the Twelve Olympians” weren’t even named; so this may have been more of an expression, a nice round number to designate the most important deities while leaving room for local interpretations of who was among them.

It’s certainly true that there are some deities who received more worship than others, and who are better known nowadays because of it. If I were to write an approximate list, it would be the following:

Zeus

Hera

Poseidon

Demeter

Hades

Hestia

Persephone

Hermes

Dionysos

Hephaistos

Athena

Ares

Artemis

Apollon

Aphrodite

Hekate

Herakles

Asklepios

Pan

You’ll notice immediately that there are far more than twelve - nineteen, in fact - and the list could be expanded even further to include deities like the Muses or Eros. My point here is that, while “the Twelve Olympians” was shorthand for the major Gods, to limit cultic importance to just twelve, or even to just Olympians, is disregarding the broadness of the Hellenic pantheon - and the fact that it is polytheism, not dodekatheism. The Ancient Greeks may have called on the Twelve when necessary**, but their worship included many more deities than that.

And this leads on to my second point: the Ancient Greek religion was not orthodox. Each city, town or even village had its own pantheon, composed of the major Olympians, locally important deities, like Aphrodite in Kythera or Artemis in Ephesos, and deities specific to the area, like nymphs and river Gods. This means that Sparta’s pantheon was not the same as Thebes’, Thebes’ pantheon was not the same as Corinth’s, and so on.

As a result, deities that were given minor importance in one place could be given major importance in another. Take Ares, for example: though he had a sanctuary in Athens, he didn’t play a particularly large rule in the local cult outside of war times - but he was highly worshipped in northern Greece. Other than deities, heroes also need to be taken into account: Helen and Menelaus were revered as Gods in Sparta (likely as the remnant of an early cult), though practically everywhere else they were viewed as human and not worshipped. So while it would be accurate to say that Athenians paid far more attention to the Twelve than to Helen, a Spartan would bristle at the thought!

To complicate things further, there’s the matter of epithets. Gods were worshipped under different aspects in different areas, and those aspects were sometimes so different that they blurred the line between “same God, different epithet” and “actually a different God”. For example, Apollon Smitheus was widely worshipped in Anatolia (modern Turkey), and his cult was full of native Anatolian elements. So while it would be factually true to say Apollon was important both in Delphi and in Anatolia, it would be missing the fact that Apollon Smintheus was not important in Delphi.

Lastly, the state cult wasn’t the only influence on how much a deity was worshipped. Circumstances also mattered: the Agathos Daimon was central to the household cult, a sailor might give special honours to Nereus, a pregnant woman might give most of her offerings to Eileithyia, and any individual could love a specific deity above others, like Hippolytos with Artemis. These may not have left as many traces as state-sponsored temples, but in everyday life, they were no less significant.

In conclusion, there was a concept of twelve particularly powerful and important deities, and it did somewhat correspond to which deities were worshipped most in practise, but reality was a lot more nuanced. Any God could be more or less important depending on who you were, where you were, and in which circumstances. Ultimately, the Hellenic cult was - and still is - as rich in variety as it was in deities.

*Some modern worshippers choose to call the religion Dodekatheism, which I’m not criticising. This isn’t about the term but about its interpretation as “worship of exactly twelve deities” being incorrect.

**Interesting anecdote: my professor recently remarked on the fact that, in the Homeric epics at least, only desperate prayers are addressed to “Zeus and the other Olympians”. People call on the Twelve when they don’t know to whom specifically to turn, and as a result, these prayers are the most likely to go unanswered.

702 notes

·

View notes

Note

What are your thoughts on Zeus?

i have nothing else to add

508 notes

·

View notes

Text

There are fewer stories about Hermes.

Yes, he features in many. He makes appearances in myths. Providing aid to the hero, consulting with Zeus, ferrying souls. But always in the background, always a supporting character.

If he’s in a mood to joke– and he usually is – he’ll point to the Nords, say “now there’s a culture that knows how to treat their trickster God.”

But he loves it, really. He loves that space between tales. He loves the image of himself slipping through scrolls, living on the edges of stories.

There are fewer stories about Hermes, because Hermes does not tell them.

He prefers to be all-purpose. Hermes, the God of whatever needs divinity. Hermes, God of thieves and merchants, God of tortoises and Hawks, God of contradictions.

The joke, on Earth. A woman might be complaining about everyday troubles, and someone will say “take it to the Gods.”

“Oh really?” She’ll say. “The God of aching feet? The God of belly fat? I’ll just send a prayer to the God of spoilt milk.”

And someone will say, “just give it to Hermes.”

And everyone will laugh. Hermes, God of whatever.

But in those small moments, those small hurts, it is Hermes that they pray to. Because the messenger God listens, the messenger God carries every prayer, and sometimes that’s all that is needed.

Hermes cares about humanity because he cares about stories. He cares about the flicker of words from mouths, about the way information travels in haphazard lightning across continents.

He thinks himself the start of every tale, and often he is. The figure by the fire, the rich whisper of the narrator, the heat on enraptured faces. Hermes thinks himself the one to carry stories from reality to legend. He thinks himself the one who creates heroes. And it’s true, in a way. A hero is created only when stories are told about them.

And Hermes’ reward is the stories he doesn’t tell. The one God privy to playground myths, to bedtime legends, to the way people narrate the Gods when they aren’t in temple.

Hermes finds himself, there in the background, along the edges of stories he didn’t make. People add him in for that trace of humor, for that wicked smile. He’s delighted every time. The only God to take actors aside, to whisper congratulations on their portrayal of him.

If there is a story about Hermes, he didn’t tell it. It came, instead, from the storyteller being asked to repeat “the part where Hermes…” from children asking their mother to “do the Hermes voice again.” Even the Gods can’t reckon for how tales take on a new life down below. Even the God of messengers can’t contain the flow of a story from person to person.

If there is a story about Hermes, he has been in the audience every time, has heard it over and over.

If there is a story about Hermes, he knows it.

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

#apollo#hermes#dionysus#the best bros#done with Patrons now to the rest of the Theoi#hellenistic polytheist#hellenic pagan#hellenic gods#hellenistic polytheism#digital art#olympian gods#greek gods#greek mythology#art by me#apollon#bacchus#you can buy this artwork as a sticker tshirt mug etc in my teepublic shop

2K notes

·

View notes