#womanist discourse

Text

Today I heard someone say that there is an "insecurity epidemic among young men" and I am just so fucking happy someone has FINALLY given me the words to describe what is happening to the world.

I keep hearing whinging about "men's mental health crisis" and "male loneliness" and "male suicide rates" blahblah in spite of the fact that none of that stuff is actually an issue. Women's depression and rates of suicide attempts have remained consistently higher than men's over the years, and if we look at sex stats you'll see that the rise of loneliness is actually affecting women at very similar rates to men (12% and 14% celibacy rates in the US, respectively). Not to mention the suicide attempts of young women and girls have sky-rocketed in the last couple of years. Suicidal ideation in girls in my country is currently double that of boys. In spite of all this we still see males lashing out en masse, claiming that "men are under attack", "women are privileged", and feminism is "ruining men's lives".

Even though none of their claims have any basis in reality there is still an obvious problem here- something is very disturbed in the modern male psyche; but I have not seen anyone accurately label the issue until today.

There is an insecurity epidemic among men.

Women are finally attending classes, entering the workplace, and gaining voting rights in most countries around the world. These changes are a recent development and they are making modern men question their place in society- as they should. Sadly, instead of taking this time to self reflect, men are desperately trying to stop women's suffrage and cry "abuse" whenever we hold firm. What we are seeing is a big, glorified tantrum, not a "mental health crisis".

I am not sure how we would go about fixing this problem but I'm glad that I am finally able to name it!! I thank D'Angelo Wallace for the help.

#sources in hyperlinks#shout out to saudi women finally gaining the right to vote in 2016#sorry for how US-centric this post is#it isnt easy to find “involuntary celibacy” statistics for the entire globe#feminist#feminism#womanist#womanism#womanist discourse#misandry#mra#mens rights activists#mens rights#mens rights to shut the fuck up#feminist discourse#girl blogger#girl blogging#femcel#femcel actually

995 notes

·

View notes

Note

brown marxist feminist here, you are seriously brainwashed if you think critique of gender is comparable to naziism, an ideology which killed millions IRL.

putting a naziism aside, here's a quote that explains the difference between feminist critiques of gender and the far rights insistence on traditional gender roles:

gender critical feminist: "sex is a material reality. gender is constructed to oppress and control females. there is no requirement for a link between male and female and masculine and feminine. indeed, gender should be eliminated."

far right, conservative: "strict association between sex and gender. men are masculine, women are feminine. departures from this are morally deviant expressions. inferior gender roles for females inevitable."

many gender critical feminists were trans identified at one point, including myself. hope this helps!

do i need to add "feminists dni" to my pinned? as a black, queer, womanist who has received much harassment from "gender critical feminists" who don't recognize intersex people and nonbinary genders, or even non-western gender roles for men and women... this ask is only adding more affirmation and positivity to conservatives. being trans doesn't mean you are incapable of being transphobic. we all have our own personal journey with unlearning the misinformation and propaganda we've been taught, just like we have to relearn Our history from HIStory. if you think being gender critical is not in alignment with actual third reich research and conservative ideology, please expand your approach to learning about eugenics, hegemony in society, and the benefits of functional gender criticism. learn intersex history. broaden your studies on queer history among non-white people. can you explain how this ask moves away from serving, or aiding, conservative goals and intentions of actual nazis throughout history? what is your intention in sending a message like this to a fellow trans person?

i'm tired of seeing gender critical, transphobic, feminists recruiting teens and young women into this hatred fueled culture of discourse. i don't send hate to anyone. i don't send messages like this to people who may think differently than me. why are you actively contacting me? for what purpose?

are you upset that many feminists are in complete agreement with nazi ideology? why is this a matter to message Me about??? do you think fascist leaning feminism will not take away all of our rights? do you think feminism, in all it's white-washed conservative glory, is not responsible for contributing to the loss of many people who would still be here otherwise?

because this sounds exactly like the hate and harassment i get from conservatives, yet you claim to believe in the rights of all women- including women like me.

if you wanted to have a serious and honest conversation, you wouldn't have opened with name-calling me "brainwashed". you began with a level of immaturity and disrespect, showing your narrow mindedness in discussing big topics in a healthy, responsible, and mature way. if people have approached you and said things to make you feel bad about certain issues, please go to a public library and ask for someone there to help you learn more about how political propaganda and recruitment for their movements to push an agenda works. this is not how adults speak to each other.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Desire and Death in Erotic Gay Film

-A Semi-Marcusean Meditation-

While this “discourse” is primarily an issue in online spaces, I continue to be flummoxed by the online visibility of the “no kink at Pride” sentiment. This will not be an examination of that issue or “debate,” as in my mind there’s nothing to debate. Instead, I want to use some media that’s been intriguing me as a way of meditating on what kink and the politics of queer sexual practice can teach us about love and death as erotic beings.

This meditation will require a brief summary of a few ideological trends, namely: Freudo-Marxism and the writings of Herbert Marcuse. I am not a Freudian or a Marxist, but I am an anarchist and someone interested in *some* of the ways people have riffed on Freud’s ideas. Freudo-Marxism or Freudian Marxism is an umbrella term for the various attempts to apply some of Freud’s ideas on psychology to the study of society from a Marxist perspective. Herbert Marcuse in particular is a favorite of mine within this field. His book, Eros and Civilization, takes Freud’s ideas about eros and thanatos, the life and death drives, and puts them in a political context. He argues that Eros, also known as the pleasure principle, is the underlying liberative drive in humanity, defined as sensuality, play, aestheticism and affection/affectation. By contrast, the “reality” principle (thanatos) is sublimation and subjugation for the purposes of work and civilizational development. This quickly leads into social control, oppression and the like, but we are in a capitalist society where such sublimation of our authentic yearning for love is necessary to keep the machine of capitalism running. The solution, therefore, is not merely a class struggle of bourgeoisie vs proletariat, but a struggle of love and liberating desire against the forces of death and power to control.

I call this a semi-Marcusean meditation because I admittedly play somewhat fast and loose with Marcuse’s ideas. My understanding of Eros and Thanatos are informed as much by my own spiritual traditions and political impulses as they are by critical theory. Furthermore, my ideas on Eros in particular are deeply informed by the work of queer womanist Audre Lorde and queer black writer-activist James Baldwin. With that in mind, I want to talk about the work of four gay filmmakers. All of these filmmakers produce erotic films, both in the conventional sense of the word and in the sense that they all make some statement on Eros. Three of these directors make porn films, while one makes films that are not explicitly pornographic, but certainly sexualized in interesting ways. As I reflect on these artists, I will also try to illuminate what their respective works might say about the flow of kink practice between tropes of Eros and Thanatos. I will discuss these artists in a rough order, moving from the film most preoccupied with Thanatos to the one most preoccupied with Eros. While the erotic is ultimately the liberative theme, often insight is revealed by examining its opposite. And so we examine the film most steeped in the symbols of death and alienation, and see what might be revealed.

João Rodrigues

I begin with the newest film and director on this list. João Rodrigues directed the porn film O Fantasma in the year 2000. The film details the journey of a trash collector, Sergio, in his increasingly high-stakes/’transgressive’ sexual exploits. He advances through a continuum. First indulging his curiosity for sex with men, then into semi-public and public sex, fetish acts with discarded underwear and other objects, rubber/gimp suit play, etc. At the conclusion of the film, he has become a faceless gimp roaming the city’s trash dump, a vast landscape depicted as the nadir of civilization.

O Fantasma is a difficult film to pin down on the Eros-Thanatos dialectic, but I place it here first because it is the film that deals most explicitly in the symbols of Thanatos. I will argue down the line that the usage is somewhat subversive in its subtext, but there is no ambiguity about the symbols themselves.

Sergio is a horny, sexually repressed worker under capitalism. His work as a trash collector brings him into contact with the waste of capitalist society. He is an essential part of maintaining the life of people in society, and yet he feels alienation from the social world due to his relative invisibility under the valuation of capitalism (among other things). In this feeling of alienation, he resorts to increasingly transgressive sexuality according to conventional societal mores. As he does so, he becomes more enmeshed in the social symbols of alienation and death, until by the end he is an integrated part of the vast alienated landscape that is the city dump. Is he content? Has he been annihilated, personally or socially? The film does not tell us whether this is, in Sergio’s mind, a desired destiny. It only shows us the slow unraveling of his already frayed relationship to capitalist society.

I see the depiction of Sergio’s journey as a kind of queer prophetic fable, which holds up a mirror to the alienation of capitalist society, particularly in its relationship to Eros. There is a tendency among conservatives to frame the pursuit of desire and erotic fulfillment as something that inevitably leads to extremes and annihilation. This is an ancient fear, going at least back to Greco-Roman society in the pre-Christian and Christian era. There was an anxiety in those times and places that homosexuality was an inevitable temptation for bored straight men. In the conservative view, such experimentation would, if indulged, naturally lead to increasingly anti-social and self-destructive sexual practices. This attitude has persisted into the modern day. Think of the conservative canard about gay marriage, “People will be marrying their dogs next!” That frame of logic only follows if you believe that human sexuality exists as a vector of continuous growth which must be kept “in check” by the fabric of social order and repression of impulses. In reality, of course, non-hetero sex embraces a wide range of symbolic play, and has a variety of spaces wherein fantasy and experimentation with “taboo” elements can be explored safely between consenting adults in ways that transfigure and energize the erotic self. It is the conservative insistence against “excess” that gives rise to repression, which then creates an environment for suppression, self-loathing, abuse, etc.

O Fantasma explores the question of what happens when an alienated person is only able to explore Eros in Thanatotic situations. There is nothing about Sergio’s journey that would be inherently harmful to himself or others. However, rather than having a space or community to explore his desires, he is forced to operate in the shadows, and slowly loses what little status he had as a person in his community. There is a sense that he has achieved a certain apotheosis with this. The ending scenes are lonely, but not judgmental of his trajectory. There is no harm or shame in being a trash gimp, but the situation created for him means that this sexual apotheosis is only possible through completely relinquishing ties to humanity. Apotheosis is possible only through Thanatos.

There are queer theorists who argue that the death drive ought to be the guiding force of queer praxis, that the ephemerality and mortality of queerness is its only gift to personal/political resistance. I reject this idea, and have dealt with its implications elsewhere. Despite being steeped in symbols of decay and refuse, I feel that O Fantasma ultimately suggests that this idea is a flawed one. There is erotic potential in reclaiming the symbols of Thanatos, but to capitulate to a situation we queers have been forced into by oppressive white capitalist patriarchy, to say that we exist only to die and witness to anti-capitalism by our deaths, is the theme the film revolts against.

Kenneth Anger

Anger is perhaps the most complicated artist on this list. While he is a gay filmmaker who makes films that have an erotic edge to them, he does not make pornographic films. He has attempted throughout his career to deal with the themes of Eros and Thanatos, although when interviewed about his films, he is cagey about discussing their themes.

His three films which have the most to say about Eros and Thanatos are probably, in chronological order, Fireworks (1947), Scorpio Rising (1963) and Lucifer Rising (1972). Of these, Fireworks and Scorpio Rising are, to my mind, most effective. Lucifer Rising is an interesting thought experiment, about the dawn of the New Age of Aquarius ruled by a light-bringer Satan figure. It is perhaps Anger’s only attempt to make a film about pure Eros. However, this attempt is muddled by the film’s occult Thelema tropes. While occultism is certainly a valid sphere within which to express erotic themes, Aleister Crowley’s inconsistency in declaring the symbols of Thelema means that Thelema is historically more effective at rejecting institutional religion than at saying anything definitively about what should be.

Fireworks is a dreamlike short film which depicts a young Navy cadet and his homoerotic escapades with a crew of seamen who ultimately beat him to death. Though Fireworks is rather obtuse with regards to themes, it is clearly at least a satire on American militant masculinity and its preoccupation with the forces of death and aggression. The title, the Navy setting, the occasional flashes to abstract imagery of American Christmas celebrations, all point to a skewering of a particular brand of heternormative masculinity. Like O Fantasma, it holds up a mirror to the power of Thanatos in capitalist society, but unlike O Fantasma, there is no apotheosis. There is only death. In 1947, it’s easy to imagine that this sort of bluntness would have been necessary to make a statement in the face of the hegemonic norms. William S. Burroughs’ short story, “Twilight’s Last Gleamings,” (1938) a farce about a sinking American cruise ship interspersed with lines from “The Star-Spangled Banner” in all capital letters, hits similar beats.

Scorpio Rising is less satirical but perhaps more pointed in its imagery. It depicts members of a neo-Nazi biker gang and their sado-masochistic rituals as they haze a new member. While it is not a “documentary” in the contemporary sense of the word (no interviews or metatextual narrative framing), the scenes with the biker gang were real and not simulated. Anger notes that the bikers’ girlfriends were present for many of the scenes at the pre-hazing party. The bikers didn’t want their girlfriends on camera, but were apparently all too happy to let Anger film the stripping, touching, and beating of the initiate, along with several other homoerotic gestures at the party. Of course, the idea of “macho” men having repressed gay urges is old hat. One is reminded of the phrase “You construct elaborate rituals that allow you to touch the skin of other men.” While gay repression is one drive that can be at play in these kinds of rituals, I feel it’s reductive to chalk up such rituals (as many liberals are wont to do) to merely repressed homosexuality. Rather, I would argue that these incidents are an example of the thanatotic consuming the erotic. Various theorists and activists comment on this phenomenon. Christopher Hall, a masculinity studies scholar, notes that men are socialized to have relationships in a capitalist patriarchy that are “sadomasochistic in almost every sense but the sexual.” Toxic masculinity promotes the relentless pursuit of power and control, and this often is coupled with the inflicting of pain on others as a way of asserting and maintaining power. I argue that the sexualized nature of many of these rituals comes from the suppression of the erotic itself, not necessarily of a queer sexual orientation. James Baldwin suggests in his essay, “Here Be Dragons,” that boys in America are not encouraged to grow up and mature into emotionally available men. Thus, men who embrace patriarchal masculinity are not able to develop a healthy connection to their own Eros. What they fear and hate, says Baldwin, is not ultimately the possibility of homosexuality in themselves, but the reality of queer men living a more liberated erotic life without having to struggle to control or possess the objects of their desire. The macho man has struggled so hard to maintain a simulacrum of love immersed in death, and the idea that someone less “man” than he is able to have the fullness of mutual love with comparatively no effort is terrifying and emasculating. Queer womanist Audre Lorde notes that when the erotic is suppressed, it spills over into other spheres. Sexualized comings-together in the absence of Eros take place under the pretext of other meanings: “Playing doctor,” religion, or in this case, frat boy rituals. The pursuit of power and control becomes sexualized, while at the same time lacking any trace of erotic feeling. It is this dynamic that Anger captures very effectively in Scorpio Rising. The initiation takes place in a decommissioned church, and images of Jesus and the church interspersed with Hitler and Nazi images flash on the screen as the young man is whipped and abused. While I find Anger’s critique of Christianity to be shallow, in the context of the “All-American Jesus” of the 50s and 60s in white America, the juxtaposition becomes more effective.

In Anger’s work, the power of hegemonic sexual normativity is revealed as a tool of power, more specifically white power in the case of Scorpio Rising. While kink and BDSM take the symbols of violent power and use them for erotic liberation, Thanatos creates an obsession with violent power so virulent that it takes on a sexual cast without becoming actually erotic. The end stages of Thanatos are apathy and cold hatred, regarding more and more beings as inhuman to the point where it becomes difficult to feel anything at all. It is a kind of alienation and numbness at the lonely heights of power. O Fantasma shows the collective social effect of this end stage on a bystander individual. Scorpio Rising, by contrast, shows the consumptive power of Thanatos’ early stages on those who actively court and cultivate it within themselves. It suggests that we must be wary whenever someone suggests that the presence of “deviant” sexual practice in consenting adult relationships is bad for the community. Oppressive power seeks to sublimate all sexuality and desire into hatred, rage and apathy that is useful to its cause. By continuing to embrace space for subversive erotic exploration (both in the bedroom and in the political sphere), we embrace our deepest humanity and maintain a powerful weapon against death.

Fred Halsted

Halsted’s filmography and politics could take up an entire essay, many essays even. In many ways, while more openly erotic and sexual than Kenneth Anger, Halsted represents perhaps the most complex blend of Eros and Thanatos of all these four filmmakers. This is for two reasons: first, the politics of his art; and second, the politics of his own self-confession regarding his art. This is to say, what his art (to me as a queer interpreter) says and what his art, according to him, means.

Halsted was a porn star, director, sex worker, and sex club owner most active in the 1970s. He considered himself “a pervert first, a homosexual second.” Much of his work is dedicated to showcasing the transgressive power of BDSM, “rough” gay sex, and other queer sexual practices at a time when sexual liberation was ascendant in the popular imagination.

Though one could approach any of Halsted’s work and find rich material to analyze, Sex Tool (1975) is perhaps the best for the theme of this essay. The central plot of the work is a series of vignettes, each showcasing the kinky interests of various socialites at a party (ie, what they get up to and get off to in their free time). The vignettes are held together by the two leads, a young man and his trans female lover who shares the relevant gossip about these socialites and their tastes with him.

The tastes in question include watersports, sadomasochism (including blunt force and piercing), mild blood play, burlesque drag, and public sex. I will first cover what Halsted said about his own work, and then my take on it.

Halsted mentions that the theme of Sex Tool is “sexual politics.” He also said elsewhere that sex and the erotic were inherently emotional, sacramental, spiritual realities for him. In an oft repeated quote he notes “I don’t fuck to get my rocks off, I fuck to get my head off, my emotions off.” All in all, with his emphasis on “perversion,” Halsted is interested in the subversive power of kink to reveal existing power structures of respectability. He was often as frustrated with integrationist elements in the gay rights movement as he was with the pearl clutching of the straights. In this respect, Sex Tool is about exposing Thanatos through transgressive Eros. The film may subtly judge its subjects, but if so, it judges them for their phoniness. For their investment in the veneer of respectability when their desires are just as “taboo” as anyone else’s. Halsted does not seem to have a message beyond this point. There is no “...and then what?” Only the prophetic exposure of sexual civility for the sham that it is, and the unspoken invitation to pursue a greater erotic honesty in all spheres of life.

Yet despite this radical refusal of meaning, which might ordinarily coincide with a kind of death drive, Halsted’s own spiritual investment in his eroticism imbues these scenes with a kind of verve that feels inexplicable purely as Thanatos. They are rough, bawdy, often violent scenes but they are also full of throbbing, pulsing life. The lovers depicted may not always seem to “like” each other. More often, there is a kind of love/hate dynamic (whether between dom and sub, or between closeted john and cross-dressing sex worker), but this is not the annihilating indifference of O Fantasma, nor the fear-turned-hatred of Scorpio Rising and Fireworks. Rather, it is the dynamism of Eros surviving and working itself out on the fringes of conformity, of authentic desire welling up to the surface and crackling like lightning across the scene. As drag queen Trixie Mattel notes about “hate fucking,” “If you wanna fuck someone, you don’t hate them that much.” In Halsted’s work, one sees an alchemical explosion of rage, desire, yearning, anger and love. It is the wrestling of Thanatos (Conformity threatening alienation, dissolution, and dis-identification) and Eros (Desire promising transcendence and the vibrancy of life). In that respect, it is also a powerful refusal of hatred, though portrayed through characters who are still wrestling with the politics of their queer, “perverse” desires.

Wakefield Poole

Finally, we come to the hauntingly luminous Eros of Wakefield Poole. Poole was an artist who made a number of different gay films. The two most famous, Boys in the Sand (1971) and Bijou (1972), are works of vivid Elysian beauty. Bijou is the “darker” of the two, following the protagonist as he infiltrates a surreal, dreamlike sex club and has several sensual sexcapades within its twilight, psychedelic halls. Boys in the Sand is...well, exactly what it sounds like. Filmed on Fire Island, it consists of three segments of gay men having tender, intimate, and playful gay sex. By the beach, at the pool, at the beach house. Notably, it was one of the reasons for Fire Island becoming a gay destination.

It’s almost difficult to analyze Poole’s films because they’re so earnest and uncomplicated. At the same time, it’s clear that Poole has an eye for elegant settings, lighting, and filming his actors’ bodies with a tender, erotic gaze. Poole’s inspiration for Boys in the Sand came after seeing a more gritty film called Highway Hustler (1971). He found the film distasteful, and wanted to make a film “that gay people could look at and say, ‘I don’t mind being gay – it’s beautiful to see those people do what they’re doing.’”

While this may seem like a low bar to aim for, there is something deeply erotic and beautiful about Poole’s approach and execution. One of the segments was filmed with Poole’s lover, Peter Fisk, and Poole instructed his actors much of the time to do what they would naturally do in a sexual scenario, not dictating their “moves” or poses. While it is acting inasmuch as it’s part of a porno, the sex in Boys in the Sand is as authentic as the medium allows, framed by lush natural beauty and the sparkle of light on water and skin. As I mentioned above, Bijou is less bright but no less colorful, and Poole’s methods were similar. When filming screen tests for Bijou, the actors were encouraged to “seduce the camera,” and masturbate to climax. The commitment to arousing genuine pleasure throughout the process of creating these films bathes them in an erotic glow.

Though less kinky than Halsted’s filmography, Poole’s work still provides a radical example of queer Eros in action. So much of the effort to make gays “respectable” has gone into de-sexualizing and de-eroticizing us to the point of emotional sterility. This is a phenomenon which is easily manipulated by the Thanatos of repressive society. Conservative American sexuality considers the mere existence of same-gender fucking to be “kinky,” to be a taboo which brings shame on its practitioners. When gays are tolerated, it is only when we are flayed of any hint of sexualized “flesh,” and our existence as social beings is as dry and lifeless as bleached bones.

Lest this be seen as purely a matter of homosexuality, it’s important to name that this stripping of flesh is quickly turned on the straights as soon as they don’t have gay targets to focus on. BDSM between cishet couples is taboo in “polite” society, and frequently seen as a sign or cause of emotional trauma, a phenomenon that is popular enough to make lots of money for the author of the Fifty Shades of Grey trilogy, for example. Anal sex among cishet couples is seen as taboo, even oral sex was taboo as recently as the 1950s.

Wakefield Poole imbues his work with counter-cultural Eros by posing and answering the question: What if we showed gay love on screen, as something both profoundly, unapologetically beautiful and profoundly, unapologetically sexual? Indeed, Poole shows what I would call the transcendent, paradisiac, or Elysian approach to depicting queer Eros. The erotic at its most potent is profoundly subversive of the forces of death, but it can be so in a variety of different ways. One way is through the transgressive approach, liberating the “negative” symbolism by embracing it in creative ways. Another way is to display the ways that healthy queer sexuality can be even more radiant, luminous, transcendent, and vital than some straight sex. It is to show the echo of the heavenly and the divine in freely given gay desire fulfilled. Straights too can experience this deified Eros (both in sexual and non-sexual spheres), but only if they reject the cultural conditioning of heteropatriarchy. Poole’s work shows the light that shines through human beings in love and sex when we lay down our arms and allow ourselves to fully delight in mutual pleasure in its myriad forms. It shows the ways that earnest Eros can reveal the divine image in us all.

#film studies#Marcuse#Freud#gay cinema#queer theory#queer theology#Kenneth anger#Fred Halsted#Wakefield Poole#Joao rodrigues

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thanks for the tag @jemgirl86 !

Last Song:

Currently cooking, so it played Wake Me Up Before You Go Go. Before that it was Tears for Fears (Shout) and Before that Carole King with I Feel the Earth Move. Damn Carole really messing up the 80s vibe tbh.

Currently Watching:

Tried watching Japanese Tales of the Macabre on Netflix and the second episode fucked me up so bad that I had to turn it off.

I'm still slowly making my way through succession (on s2) and avoiding spoilers and hence also avoiding discourse which is nice. Strange New Worlds just finished and absolutely failed to cheer me up about new trek. Still following wwdits but have nothing to say about it.

Currently Reading:

I've been reading some audre lorde essays (someone gave me a book that's a compilation) and I like it and feel like I'm leaning a lot that was missing from my own education, but, well, it's a collection of feminist/womanist essays from the 80s. It's not exactly a hoot.

On the more fun side, I guess comic books? Although, aside from keeping up with new shit, I'm only really reading 70s cap stuff and that is on hold because I got to that awful "snap wilson" retcon and it just takes it out of you.

In general, I am terrible at reading. Something in me broke when I was a student and now I cannot read for fun. I was supposed to read six books this year. I've managed one and a half.

Current Obsessions:

Pickled red onions. Like, seriously.

Tagging @sammysdewysensitiveeyes @catboy-sinister @kwxnnxn but no pressue

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

reading a book about women in pre-conquest america that claims to be womanist/challenging systems/structures but still uses the pre/history dichotomy without even acknowledging that that framing explicitly privileges written sources couched within a dominant european AND male discourse. it's fine

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

as a Jew who converted to Christianity currently serves as a lay minister for a progressive church and studied queer womanist theology under Kelly Brown Douglas if I never have to read another winter holidays discourse post ever again I stg y’all

#tumblr is not theory#everyone calm down#and I mean everyone#you’re all right#and therefore being completely annoying

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Womanism gives black women the freedom to define an express their femininity and womanhood under their own terms.

“Black womanism is a philosophy that celebrates black roots, an the ideals of black life, while giving a balanced presentation of black womanhood”.

- Chikwenye Okonjo Ogunyemi

#hoodoo#the love witch#black femininity#aphrodite#black glamour#haitianvodou#leveling up#black witches#african american folk magick#black feminism#womanism#womanist#feminism#intersectional politics#intersectional feminism#intersectionality#witchblr#erzuliefreda#lgbt discourse#witches of color#brujasdeinstagram#brujas of tumblr#brujeria#paganism#green witch#divine feminine#venus#mother goddess#matriarchy

341 notes

·

View notes

Text

Women don’t need to be beautiful. Beauty is not the only thing women have to offer, nor should it be expected of us, or revered as the most valuable thing about a woman. When you compliment a woman, try not to make her appearance the main focus. When you interact with women, don’t focus on her outer shell. Connect with women as people, not objects on display.

#inclusive feminism#feminism#feminist discourse#feminist theory#postmodern feminism#womanist#womanism#terfs dni

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

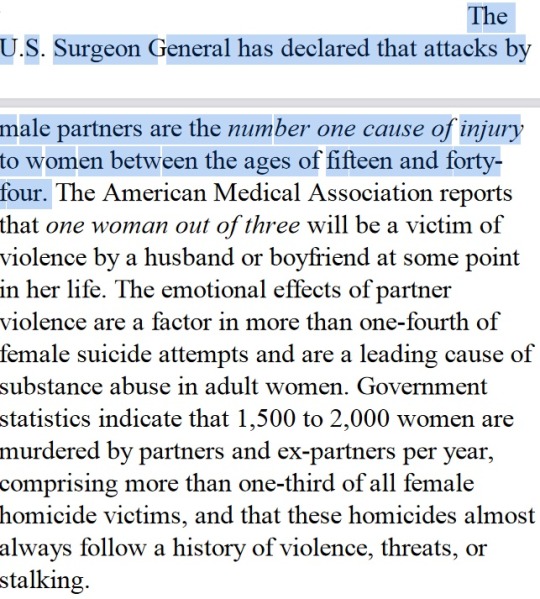

~ 2002 Domestic abuse stats from: Why Does He DO That? by Lundy Bancroft

Day One

While I was reading this phenomenal book I decided that I would start screenshotting excerpts and post them to tumblr for those who could be helped by exposure to this information. over the course of the next few weeks I will be posting daily statistics and excerpts from the book and occasionally I may add commentary (though the author already does a perfectly fine job of that himself honestly).

#why does he do that#feminism#feminist#womanism#womanist#feminist discourse#womanist discourse#abuse#abuse prevention#domestic violence

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

hey, i hope youʼre having a good day! i saw you mention a while ago that you were taking a queer theology class - do you have any reading recs about that? it sounds like a really cool field and iʼd love to know more but donʼt have any idea where to start haha

Hey! So it’s harder than it perhaps should be to recommend good introductory texts to queer theology (in a lot of ways because many of the standards are either operating at a really precise level within philosophical/theoretical discourse and some are just, well, Not Great), but Linn Tonstad’s Queer Theology: Beyond Apologetics and Pamela Lightsey’s Our Lives Matter: A Womanist Queer Theology are solid to begin with

#it's worth noting that both of these are specifically Christian queer theology texts#I am less familiar with nonchristian ones and am not in a place to give recommendations

17 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello, I read your message but unfortunately I cannot reply you because you have restricted the replies to mutuals only, so i'll reply your question: it was indeed 8 years ago (sadly i have forbiden to send links in the question section) but TL;DR: you said that you don’t use the word oppression because it implies a "privilege" dynamic in order to explain the anti-ace bias. As you considered "privilege" was not a viable concept in this regard.

(this is the post that the asker is referencing)

initially when i was writing a response, i wrote a whole long thing about what informs my current position as well as previous positions. then I actually read the post you're referencing, and i don't agree with what i wrote in 2012 (and neither does the friend who askboxed me in that post).

so instead I'm going to describe what 2012 was like, in order to give you context for that post.

in 2011-12, i didn't know about how oppressions that lack a privilege/oppression dynamic worked, and if you wrote the word "oppression" to describe something on this site, a lot of people would assume that you also believed that the oppression proliferated via a privilege dynamic. oppression is defined in every sociology class I've ever taken as prejudice plus power—which people often said as "prejudice plus privilege" (today i realize that privilege is only one possible form of "power" that can exist). so that's why i assumed that the word oppression implied a privilege model.

the privilege model was developed in critical race theory specifically as a way to explain why racism is invisible to white people and how it continues to proliferate. white people continue to reinforce racist structures of society because they are incapable of independently noticing the unearned benefit (privilege) granted to them by a society built on white supremacy. i knew this at the time i wrote the post you're talking about.

the privilege model entered feminist discourse via an essay by a white woman (whose name i honestly forget) called "Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack," where she listed examples of her own white privilege and then decided to apply a privilege model to describe how sexism is invisible to men, who benefit from it. that's how the term male privilege came into being. i read this essay in 2009 in an intro women's studies class. (I have not read Black feminist and womanist commentary on the term but I want to, because many things I've seen white women categorize as male privilege are things that don't apply to Black men.)

so that was my own intellectual background to the post from 2012. now I'm going to describe the context of asexual discourse i was participating in at the time.

prior to 2010, sometimes the question of "are we oppressed for being asexual" would arise. different aces put forth all different answers about this, but it was mainly an intellectual exercise that didn't affect our ability to talk about asexual issues. even if it got heated, this was a question discussed among asexual communities. there was no consensus. there wasn't pressure for consensus. that pressure took center stage after 2010.

efforts to prove that Asexuals Are Oppressed began because of people who refused to take asexual issues seriously unless we could prove we were Oppressed. when we described our issues in ways that could be understood as oppression, they moved the goalposts and told us that it wasn't enough and that we had to prove that our issues could not be due to any other structural oppression that they already accept.

if someone did make an argument for the existence of a specific anti-asexual oppression, it was never seriously evaluated by these goalpost-shifters. and it was taken by those people as evidence of LBGTQ asexuals being homophobic. (most of the asexual people involved in 2011-12 ace discourse were not heteroromantic, in my memory. many of us were trying to talk about issues we experienced within LGBTQ spaces as LGBTQ asexuals.)

i want to repeat: the whole reason 'Are Asexuals Oppressed' is still a question at all is because of bad-faith actors knowingly demanding an impossible standard because they were never interested in taking asexual issues seriously.

so today, I take the position that asexuals shouldn't have to prove there's a specific anti-asexual oppression built into society in order to have asexual issues taken seriously. because the people who demand that standard are bad-faith actors who are only trying to stop asexual people from talking about our experiences.

asexual people should be able to say "this happened because I'm asexual" without being told "no, it was because of misogyny." even if it was 100% provable that the event was explainable by misogyny alone, denial of sexual agency is still affects asexual people in a specific way (sometimes multiple ways at once, as with BIPOC asexual people) that we need to be able to talk about.

what i meant in 2012 was "if oppression means a privilege dynamic, and a privilege model doesn't work to explain bad stuff happening to asexual people, I'm not going to use the word oppression anymore to describe asexual issues"

on the subject of why I think a privilege/oppression model doesn't work wrt asexuality today, this is what I mean:

non-asexual trans women experience no unearned benefit compared to asexual trans women, because transmisogyny involves stripping all of them of sexual agency

non-asexual autistic people experience no unearned benefit compared to asexual autistic people, because ableism involves stripping all disabled people of sexual agency.

non-asexual LGBQ people experience no unearned benefit in society compared to asexual LGBQ people. heterosexism categorizes all of us as inadequately heterosexual.

hypersexualization and desexualization are aspects of racism that strip BIPOC of sexual agency (they are tools of other oppressions as well)

because so many oppressions, especially racism and misogyny, involve stripping people of sexual agency, it does not make sense to claim that there exists a system granting unearned benefit to non-asexual people ("allosexual privilege"). it is also racist to apply a framework developed for understanding racial dynamics in a way that denies the impact of racial dynamics.

privilege of a majority group isn't the only framework that can ever exist to explain an oppression. all oppressions work together, but all work differently.

"Are Asexuals Oppressed" is a question that has been deliberately wielded by bad-faith actors to distract us from discussion of concrete asexual issues (like: white asexual people describing asexual issues in ways that marginalize Black asexual issues). "Are Asexuals Oppressed" is a question that reopens a lot of old wounds i got during 2011-12 as a prominent ace discourser. and that's why i refuse to try answering that question anymore.

because there shouldn't need to be a concept of a specific institutionalized anti-asexual oppression in order to have people take asexual issues seriously.

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Soul 2 Soul Sister

This is one of the few organizations in the U.S.A. that unapologetically intersects Black faith/spiritualities, radical reproductive justice, increasing the power of Black voters, and reparations. Providing a Black Womxn-led, faith-based response to the anti-Black violence in the U.S., S2SS engaged groups of white interfaith participants in anti-racism programming called Facing Racism, as well as groups of Black Womxn in self-healing work. Providing a Black Womxn-led, faith-based response to the violent preservation of anti-Blackness in the U.S.A., S2SS engaged groups of white interfaith participants in anti-racism programming called Facing Racism, as well as groups of Black Womxn in healing self-liberation work. Through this synchronous racial justice approach, S2SS promotes holistic processes of self and communal health toward engaging in authentic discourse and egalitarian relationship-building. Ultimately, the organizational aim is for people of all racial/ethnic groups to work together to dismantle personal and systemic racism toward developing healthy, just and liberative communities. Based in Denver, Colorado, Soul 2 Soul Sisters is a grassroots nonprofit that is informed by womanist theology. S2SS's womanist-based work includes Black Womxn-centered education, organizing, leadership development, as well as self and sisterly care and healing. S2SS strives to provide a sacred space for Black Womxn to rest, share their experiences, and develop and implement strategic plans for individual and collective peace, power and liberation.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Giving Visibility to Women to Better the Movement for Racial Justice

America has a long history of relying on the fruitful labor of women, whilst simultaneously rejecting their existence. The roots of this dismissiveness can be traced to the very systems and values that this country was founded on and are upheld by this country: capitalism, racism, ableism, the patriarchy, to name a few. Yet, it remains to be a surprise to many when this oppression is brought to light in the context of existing oppressed groups, specifically black people. There was a sentiment that was expressed during the class discussion of Black Feminism that centered around the fact that it is common to view infringements on one’s multiple identities can be a attacked only one at a time. This mindset is harmful but unfortunately has been the tone set by preceding movements organized to better the conditions of black Americans in regards to dealing with the oppression of identities besides race. It is important to make note of the very issue that oppression is not only limited to the traditional actor, the rich white male, but can take many shapes and forms, which is inclusive of those who are traditionally stigmatized to a certain extent. It remains, though, that black women have historically always been the ones to take up the laborious task of effectively organizing for their interests, yet their efforts have constantly been appropriated for a man to occupy the leadership positions and they fade into the backdrop. The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin is a very good example of this sentiment in the sense that while it is a beautifully composed narrative of the troubles of being a black person in the US, there is a noticeable lack of women in the book which is strikingly similar to the previously explained themes of black women lacking visibility. It signals that the pattern of denying black women roles in which their efforts can be attributed back to them, is rare in terms of history; but can be beneficial in finding successes through unity. Black women should not have to resort to infrapolitics within the movement for black lives, as movements like the black feminist movement arose to show that women’s rights are everyone’s rights, therefore need visibility to maintain an inclusive movement.

As it is rather unsurprising that black women have been left out of discourses that apply to their identities as black and women, in The Fire Next Time it can be argued that the

illustration of the experiences of a black woman are minute but also relegated to traditional gender roles. This statement is divisive in a sense, but it also holds a lot of truth when considering that there are very little instances, in comparison with the various mentions of the black male experience, where the reader will find Baldwin take the black woman’s experience into account. This is not to say that there is no mention of women at all in the book, but that their roles besides being caregivers and needing protection are not simply enough. Take the meeting with Elijah Muhammad into account, where he is cognisant of the division in gender when he is at Muhammad’s house.Upon arrival to the residence, he notices that the women are sitting on the opposite side of the room and playing with a baby and the men are sitting with him having a discussion, until Muhammad walks into the room. He mentions how Muhammad acts a little flirtatious towards the women and they are responsive to it. The way he portrays this is interesting because while it is evident that he is knowledgeable of the simplistic role of the woman in the Nation of Islam, he doesn’t really expand on the experience as a . This is in stark contrast to the time that he spends expanding on the tumultuous experience of being a young black man. It is interesting to compare his dear regards for his nephew, in his letter My Dungeon Shook, where he takes the time out to speak on the transitional experiences of growing up as a black man, but he doesn’t pay much mind to the women that exist around him, what he does tell him to do is reiterate the amount of love his mother and grandmother have for him. This is a constant theme throughout the book, in which the portrayal of women in this book are loving but also somewhat patronizing. One could argue that it could be that there is a difference in experiences, that the absence of the female characters could be attributed to the fact that men had more visibility to Baldwin. That lack of visibility, however, does not reflect on the amount of agency practiced by black women in the past.

Looking at the actions of black women through an infra-political lens may be helpful in understanding the not visible but powerful roles that black women have played in the movement for black lives. As discussed in class, infrapolitics was introduced as a concept of examining resistance tactics of oppressed individuals acting within their means, which often was a method used by women who were confined to repressive jobs and could not participate in other organizing methods. Robin D. G. Kelley’s We Are Not What We Seem explains the spaces dominated by infrapolitical action as, “the social and cultural institutions and ideologies that ultimately informed black opposition placed more emphasis on communal values and collective uplift than the prevailing class-conscious, individualist ideology of the white ruling classes.” This draws on a sentiment voiced during our class about the women’s era, in that the organizing model that these working class women embodied focused on what could be done in the confines of their positions rather than a traditional model that had centralized authority. Black women looked for more reform, rather than political rights. They did not seek to overturn hierarchies because they were barely recognized because of persisting gender roles. Although there was a move to during the progressive era to tried to change language from strict gender roles. Another common theme during this period was the aspiration of a level of respectability to achieve racial equality, which was gained significant participation by black women. While there were many black men that championed this ideal and created the “Talented Tenth”, women adhered to this hierarchy but also took the ideal a step further by using the idealism of respectability as a motivation to promote the theory of racial justice through furthering education. This is a widely touted solution to many problems, that was championed by women by the likes of Anna Julia Cooper and the motives were to get an education, move to south, challenge respectability politics (unfortunately not the level they were perpetuating) and challenge white womanhood morality through different representations of womanhood. While this provides an opportune framework for upward mobility, it was arguably limiting to those who did not have the resources to pursue this course of action. This was also inherently exclusionary of the working class women who were already organizing within their positions of marginalization and disregarding to the contexts in which they already existed within, whether it was class, family life, geographical location, etc.

This exclusionary behavior has persisted regardless of recognition of the exclusionary themes that have existed in organizing in the movement for black lives. While the root of problem could be attributed to being socialized in systems that inherently oppress people. In attacking this issue, one can draw from Audre Lorde’s Age, Race, Class, and Sex to understand that without able to acknowledge that relying on traditional lines separating certain identities is weak, there is an inherent discord in a resistance movement. Audre argues that rejecting difference denies one the ability to be able to be apart of an effective movement that is inclusive of all because it is led through the perspective of the higher ups . This is true for the many walks of lives that are covered in the movement for racial justice in the US, because with a traditionally male leadership, it has shown that many of the interests of women were disregarded. It can be argued that while using this perspective provided more unified and streamlined framework to draw objectives from, but is exclusionary of the many people that benefit from this movement.

It is imperative that to continue an effective movement for black lives, that there is a move to be more inclusive not only of the laborious community of women that have been building the movement since the beginning. Black women have gone on to create more inclusive spaces and movements, such as the Black feminist movement and the womanist movements to organize. However if these perspectives are not recognized on a leadership level,

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

A BLACK FEMINIST/WOMANIST BOOK LIST

1. All About Love-Bell Hooks

2. Women, Race & Class-Angela Y. Davis

3. The Bridge Called My Back-Rosario Morales

4. The Invention of Women: Making an African Sense of Western Gender Discourses-Oyeronke Oyewumi

5. When Chickenheads Come Home To Roost: A Hip Hop Feminist Breaks It Down-Joan Morgan

6. Playing In The Dark-Toni Morrison

7. The Black Woman, An Anthology-Toni Cade Bambara

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Giving Visibility to Women to Better the Movement for Racial Justice

America has a long history of relying on the fruitful labor of women, whilst simultaneously rejecting their existence. The roots of this dismissiveness can be traced to the very systems and values that this country was founded on and are upheld by this country: capitalism, racism, ableism, the patriarchy, to name a few. Yet, it remains to be a surprise to many when this oppression is brought to light in the context of existing oppressed groups, specifically black people. There was a sentiment that was expressed during the class discussion of Black Feminism that centered around the fact that it is common to view infringements on one’s multiple identities can be a attacked only one at a time. This mindset is harmful but unfortunately has been the tone set by preceding movements organized to better the conditions of black Americans in regards to dealing with the oppression of identities besides race. It is important to make note of the very issue that oppression is not only limited to the traditional actor, the rich white male, but can take many shapes and forms, which is inclusive of those who are traditionally stigmatized to a certain extent. It remains, though, that black women have historically always been the ones to take up the laborious task of effectively organizing for their interests, yet their efforts have constantly been appropriated for a man to occupy the leadership positions and they fade into the backdrop. The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin is a very good example of this sentiment in the sense that while it is a beautifully composed narrative of the troubles of being a black person in the US, there is a noticeable lack of women in the book which is strikingly similar to the previously explained themes of black women lacking visibility. It signals that the pattern of denying black women roles in which their efforts can be attributed back to them, is rare in terms of history; but can be beneficial in finding successes through unity. Black women should not have to resort to infrapolitics within the movement for black lives, as movements like the black feminist movement arose to show that women’s rights are everyone’s rights, therefore need visibility to maintain an inclusive movement.

As it is rather unsurprising that black women have been left out of discourses that apply to their identities as black and women, in The Fire Next Time it can be argued that the

illustration of the experiences of a black woman are minute but also relegated to traditional gender roles. This statement is divisive in a sense, but it also holds a lot of truth when considering that there are very little instances, in comparison with the various mentions of the black male experience, where the reader will find Baldwin take the black woman’s experience into account. This is not to say that there is no mention of women at all in the book, but that their roles besides being caregivers and needing protection are not simply enough. Take the meeting with Elijah Muhammad into account, where he is cognisant of the division in gender when he is at Muhammad’s house.Upon arrival to the residence, he notices that the women are sitting on the opposite side of the room and playing with a baby and the men are sitting with him having a discussion, until Muhammad walks into the room. He mentions how Muhammad acts a little flirtatious towards the women and they are responsive to it. The way he portrays this is interesting because while it is evident that he is knowledgeable of the simplistic role of the woman in the Nation of Islam, he doesn’t really expand on the experience as a . This is in stark contrast to the time that he spends expanding on the tumultuous experience of being a young black man. It is interesting to compare his dear regards for his nephew, in his letter My Dungeon Shook, where he takes the time out to speak on the transitional experiences of growing up as a black man, but he doesn’t pay much mind to the women that exist around him, what he does tell him to do is reiterate the amount of love his mother and grandmother have for him. This is a constant theme throughout the book, in which the portrayal of women in this book are loving but also somewhat patronizing. One could argue that it could be that there is a difference in experiences, that the absence of the female characters could be attributed to the fact that men had more visibility to Baldwin. That lack of visibility, however, does not reflect on the amount of agency practiced by black women in the past.

Looking at the actions of black women through an infra-political lens may be helpful in understanding the not visible but powerful roles that black women have played in the movement for black lives. As discussed in class, infrapolitics was introduced as a concept of examining resistance tactics of oppressed individuals acting within their means, which often was a method used by women who were confined to repressive jobs and could not participate in other organizing methods. Robin D. G. Kelley’s We Are Not What We Seem explains the spaces dominated by infrapolitical action as, “the social and cultural institutions and ideologies that ultimately informed black opposition placed more emphasis on communal values and collective uplift than the prevailing class-conscious, individualist ideology of the white ruling classes.” This draws on a sentiment voiced during our class about the women’s era, in that the organizing model that these working class women embodied focused on what could be done in the confines of their positions rather than a traditional model that had centralized authority. Black women looked for more reform, rather than political rights. They did not seek to overturn hierarchies because they were barely recognized because of persisting gender roles. Although there was a move to during the progressive era to tried to change language from strict gender roles. Another common theme during this period was the aspiration of a level of respectability to achieve racial equality, which was gained significant participation by black women. While there were many black men that championed this ideal and created the “Talented Tenth”, women adhered to this hierarchy but also took the ideal a step further by using the idealism of respectability as a motivation to promote the theory of racial justice through furthering education. This is a widely touted solution to many problems, that was championed by women by the likes of Anna Julia Cooper and the motives were to get an education, move to south, challenge respectability politics (unfortunately not the level they were perpetuating) and challenge white womanhood morality through different representations of womanhood. While this provides an opportune framework for upward mobility, it was arguably limiting to those who did not have the resources to pursue this course of action. This was also inherently exclusionary of the working class women who were already organizing within their positions of marginalization and disregarding to the contexts in which they already existed within, whether it was class, family life, geographical location, etc.

This exclusionary behavior has persisted regardless of recognition of the exclusionary themes that have existed in organizing in the movement for black lives. While the root of problem could be attributed to being socialized in systems that inherently oppress people. In attacking this issue, one can draw from Audre Lorde’s Age, Race, Class, and Sex to understand that without able to acknowledge that relying on traditional lines separating certain identities is weak, there is an inherent discord in a resistance movement. Audre argues that rejecting difference denies one the ability to be able to be apart of an effective movement that is inclusive of all because it is led through the perspective of the higher ups . This is true for the many walks of lives that are covered in the movement for racial justice in the US, because with a traditionally male leadership, it has shown that many of the interests of women were disregarded. It can be argued that while using this perspective provided more unified and streamlined framework to draw objectives from, but is exclusionary of the many people that benefit from this movement.

It is imperative that to continue an effective movement for black lives, that there is a move to be more inclusive not only of the laborious community of women that have been building the movement since the beginning. Black women have gone on to create more inclusive spaces and movements, such as the Black feminist movement and the womanist movements to organize. However if these perspectives are not recognized on a leadership level,

1 note

·

View note