#wildlife biology

Text

This lady was watching me and my friend very intently as we walked past her nest

#canada goose#goose#geese#canadian geese#birds#bird nest#mine#ornithology#nature#wildlife#naturalist#nature photography#photography#ecology#north america#animals#bird watching#birding#bird photography#birdwatching#bird#ecologist#biology#wildlife biology#biologist#original photography#original photographers#wildlife photography

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

MY SUCKERS (rescue mission successful)

242 notes

·

View notes

Text

Does anyone know if crows have developmental disabilities (if so, can anyone point me in the direction of some studies on this) and also do crows ever care for their disabled family members?

315 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pair of Gibbons | Olaus Murie (1889-1963)

#olaus murie#olaus johan murie#animals#mammals#wildlife biology#zoology#hylobatidae#lesser apes#gibbons#vintage art

191 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some non-fanart for you all! Thought all the wildlife enjoyers might like this! It’s going to be hung in my lab space to make my windowless room a little more pretty 🐟🦋

#art#artists on tumblr#digital aritst#entomology#aquatic biology#biologist#biology#bugs#loon#ornithology#birds#aquatic#gen art#fanartists on tumblr#biology art#entomology art#wildlife#wildlife biology#biology grad school

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

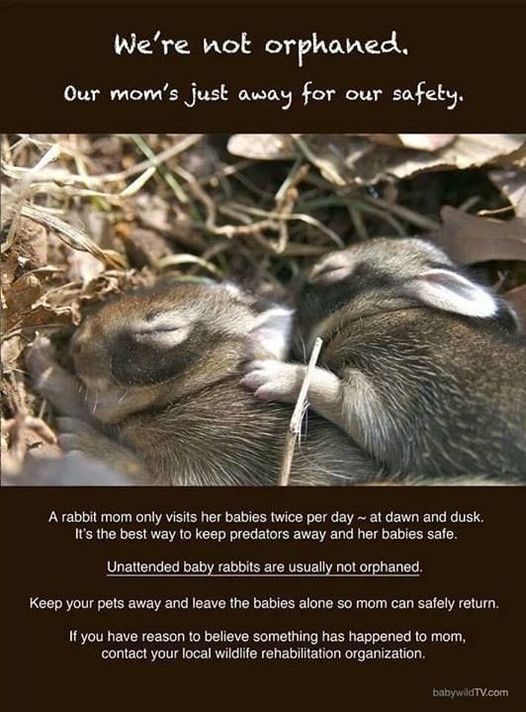

#rabbit#lagomorph#mammal#animals#nature#wildlife rehab#animal rehabilitation#animal welfare#science#wildlife biology

171 notes

·

View notes

Text

I know this blog is lichen focused, but I also consider it a science blog and a space where I can talk about my experiences in science and academia. My most recent field work involved catching, handling, and ringing birds at a bird observatory, and I wanted to talk a little about the harsh realities of working with wild animals that I feel like don't get represented enough. I think it's important to paint a fair and realistic picture of what the world of animal research looks like, as it often gets misrepresented in media.

Wild animals do not like being handled. You have probably heard some story or seen some movie that makes it seem like you are somehow gonna connect to the animals you are working with and reassure them that you mean them no harm. No no, you are a big scary predator and they have no idea what is happening, and they scream, bite, and fight like hell to get away from you. This runs the gambit from kinda funny to mildly annoying to actually making it hard for you to work to making you feel bad for putting these animals through this stress. There will be no special magical wild animal friendships, trust me.

Animals are DIRTY. Like I know you know that on some level, but you don't really know it until you are up close and personal with them. In the case of the birds I work with, this usually means shit. Lots and lots of shit. On them, or you, on every surface and article of clothing you have. And you may think "in the grand scheme of poops, bird poops aren't so bad." But let me tell you: in sheer quantity and viscosity, bird shit beats them all.

PARASITES. Now we are not anti-parasite on this blog in general, they have their place in the ecosystem just like everything else. But personally, I don't really enjoy having to see them or experience them up close and personal. I'm talking ticks, fleas, mites, intestinal worms, louse flies, etc. Just . . . no thanks.

Animals get injured, and having to see these injuries up close and knowing there isn't anything I can do about it is hard. Be they old wounds, new, or the very rare wound that can occur during the catching and handling process, it can really get you down looking at an animal that you can't help.

Animals are unpredictable. Like, most of this field is about *trying* to predict their behavior, but animals are true disciples of Murphy's Law, and I swear they get off on frustrating scientists and their well laid plans and hypotheses. For me, this meant that the birds I was working with just didn't show up in the predicted numbers. This was frustrating to me on a how-the-fuck-is-my-project-gonna-work-out-now? level, but also on a worried-for-the-health-of-the-birds-and-the-planet level. If you enjoy work that is predictable and dependable, wildlife biology isn't for you.

I wat to be clear that I LOVE what I do, and I wouldn't trade it for the world. The work I and other wildlife biologists do is incredibly important and I am not saying this to cast a disparaging light on the field. But so many wildlife biologists I have interacted with are not like, bleeding heart, sensitive babies like me, and didn't adequately prepare for the mental and emotional toll of working with wildlife. I think the field selects for folks who are able to compartmentalize their love and empathy for animals, and I don't like that. I think we need people like me in the field, but I think they should be prepared for the reality of it, that's all. Or maybe I just need to vent lol.

#not lichens#biology#wildlife biology#field work#biologist#wildlife biologist#graduate student#biology phd#nature#tw animal harm#tw parasites

178 notes

·

View notes

Text

Its the year of the Cicada! So I decided to design a new tattoo for the occasion! >:) I hope everyone enjoys it! This was definitely a super fun challenge for me!

#nature#animals#bugs#entomology#cicada#cicadas 2024#tattoo design#bug tattoo#I love the these lil screaming things#periodical cicada#cicada life cycle#i love bugs#bug art#wildlife#wildlife biology

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

I might be going back to school...

I can't believe it. At 32, I am looking into wildlife biology and conservation programs. This is all your fault, Tumblr.

The bird blogs, especially @todaysbird and @herpsandbirds, are big factors in my decision as well as the wonderful experts and enthusiasts and citizen scientists on this site. You all inspire the heck out of me and now it looks like I'm actually making that into action.

I have the good nerves right now 😂

#dark academia#schooling#university#birds#wildlife#wildlife biology#ecology#animals#studyblr#conservation

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss, at Monterey Bay aquarium

#fish#rainbow trout#monterey bay aquarium#monterey bay#aquarium#aquariums#nature#wildlife#nature photography#naturalist#mine#photography#ecology#north america#animals#wildlife biology#ichthyology#biology#wildlife biologist#ecologist#biologist#fishes

804 notes

·

View notes

Text

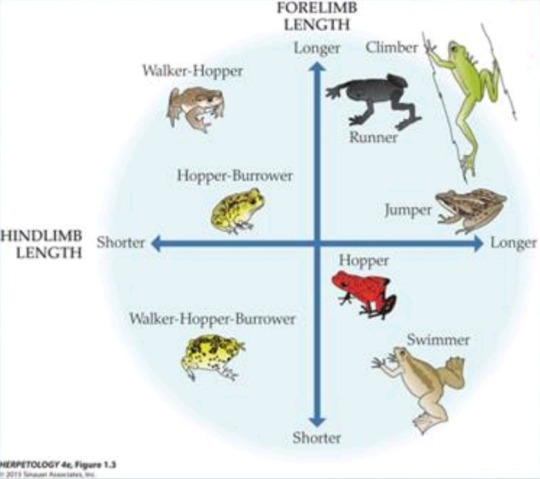

BUILD A FROG AND FIND OUT THEIR METHOD OF MOVEMENT

#frogs#anura#anura limb length and their adaptations#herpetology#fisheries and wildlife science#wildlife biology#poll#frog#toad

107 notes

·

View notes

Text

Video of coho salmon holding in a pool. Saw this on my survey the other day, it's always so exciting to get to watch the salmon so close! If you live in the PNW try to get out and see them spawning! The Chinook are winding down but coho are in (and hopefully we get some more big rains so they keep moving upstream as the smaller streams get bigger flows) and chum are next. It's a pink salmon year as well!

#fish#fisheries#pnw#animals#nature#salmon#there are many advantages to being a marine biologist#wildlife biology#biologist#biology#washington#oregon

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cow and Calf Elk | Olaus Murie (1889-1963)

#olaus murie#vintage art#animals#wild animals#animals in art#mammals#wildlife biology#zoology#elk art#elk#cervus canadensis

117 notes

·

View notes

Text

hi there! 🌿

im an aspiring wildlife biologist intending to major in wildlife bio and minor in applied ecology. I'd like to go to grad school studying wolves or canines in the future as well. i created this blog to motivate me with my studies and to reblog posts relating to my interests 🍄

i would love to chat if you have similar goals or if you are majoring/already majored in what i mentioned above! I really want to make more friends with similar interests! 🍃

#studyblr#biology#wildlife#wildlife biology#zoology#science#science major#biology major#plant biology#botany#animal science#study blog#study motivation#studyspiration#introductory post#blog intro#ecology#canines#canidae#wolves#conservation#environment#biodiversity

123 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why Have All the Birds Stopped Singing?

Originally posted on my website at https://rebeccalexa.com/why-have-all-the-birds-stopped-singing/

Summer is nearly halfway through, and while the days are still long there are already changes hinting at fall’s arrival. The heat causes some of the leaves on trees and shrubs to begin to turn just a little, and the sunset is a bit earlier each evening. One phenomenon that often startles people is when they realize that–seemingly overnight–the birds stopped singing.

Now, it’s not unusual for them to quiet down when a predator passes by (that includes us big, scary humans, by the way.) After all, they don’t want to be noticed by something that would happily turn them into a snack. But with each passing week there are fewer birdsongs in the daily chorus, and by the end of August pretty much all the birds stopped singing. Why is that?

Well, first we need to look at why birds sing in the first place. I start noticing songs late in winter, and then the diversity and frequency build up throughout spring. This is correlated with nesting season. Both male and female birds sing, though male songs have historically been given more attention.

Songs serve to establish and protect territory in which mated pairs of birds build their nests; birds of the same species know that this spot is taken, move along, please–or else. And they also help birds to attract their mate for the year; male songs in particular have been studied in this regard. So what sounds like lovely music to us is serious business for birds, meaning either “Hey, baby, check ME out!” or “GET OFF MY LAWN!” (Birdsong is also more surprisingly complex than we had assumed!)

The singing continues throughout nesting season. Some species of bird only raise one clutch of young a year, especially those whose young may take several weeks to fledge. Others, especially many songbirds, can raise two or even three clutches a year, seeing their young fledge and leave the nest within two weeks of hatching. As long as the nest is active, the parent birds work actively to protect it, to include re-establishing residency through song.

There is, of course, a risk associated with singing. Birds aren’t the only animals noticing the singer; predators also use these songs to home in on a potential meal. Singing does increase the likelihood of becoming prey, but it’s effective enough in helping spread one’s genes that it’s worth the risk from an evolutionary perspective. A bird that gets nabbed while singing near a nest is more likely to have passed its genes through at least one clutch of eggs, and if the surviving parent can get some of the young to fledgling age, then they have a good chance of surviving to spread the singing genes on to the next generation.

As soon as the nest is empty for the year, and the last batch of young have successfully fledged, the birds stopped singing. Why keep bringing attention to yourself when you no longer need to? It’s time to transition to non-breeding behavior patterns, whether that means a solitary existence, or a social group for winter.

But there’s another reason birds quiet down this time of year. By this point, their feathers are pretty beat up from their spring migration (even many resident species still engage in local migrations), and then defending their nests and literally running themselves ragged getting food for demanding, hungry young. They have to prepare for the fall migration, which for many species is a marathon thousands of miles long to their wintering grounds.

If you’re a bird whose flight feathers in your wings and tail are torn and even broken, you aren’t going to be a very efficient flier. Each wingbeat is going to cost you more energy, and on a long journey that inefficiency can be fatal. So July and the first part of August are prime times for North American birds to molt, shedding out old feathers and growing fresh new ones. By the time they’re ready for liftoff for the fall migration–or simply surviving winter’s cold right here–those shiny, undamaged feathers are going to be the perfect tools for energy-efficient flight. By saving valuable calories, they increase the likelihood that they’ll survive to see another breeding season next year.

This northern mockingbird (Mimus polyglottos) looks a little sad with a bare head–but don’t worry, those feathers will grow back soon!

But while they’re molting, they’re going to be additionally hindered in flight. That makes them even more vulnerable to predation. So this is another great reason for birds to quiet down as summer winds on. (They also may look a little silly, and while they probably don’t feel embarrassed about losing all the feathers on their head, I wouldn’t blame them if they were, in fact, a little self-conscious about it.)

Never fear, though–once late winter arrives next year, we’ll get to start hearing our birds warming up their syrinxes again, and soon the mornings will be full of the dawn chorus, fresh and new.

Did you enjoy this post? Consider taking one of my online foraging and natural history classes or hiring me for a guided nature tour, checking out my other articles, or picking up a paperback or ebook I’ve written! You can even buy me a coffee here!

#birds#birdblr#ornithology#birdsong#birbs#nature#wildlife#animals#animal behavior#wild animals#ecology#phenology#science#sci comm#science communication#biology#wildlife biology

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

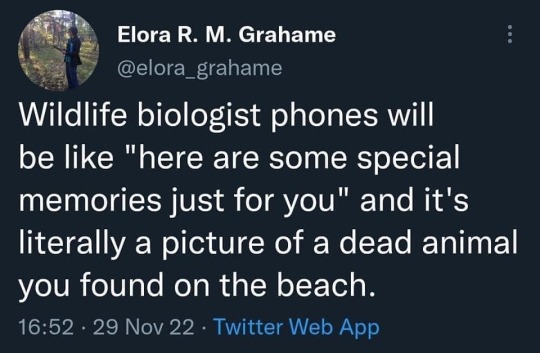

I feel so seen by this.

173 notes

·

View notes