#portrait of pope julius ii by raphael

Text

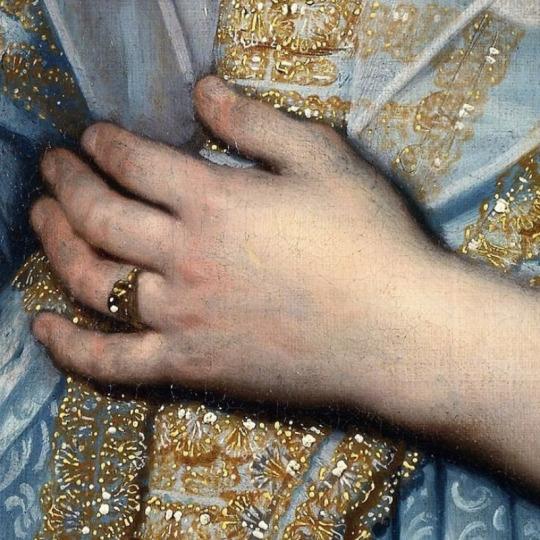

rings + art

#isabel de bourbon by rodrigo de villandrando#i cannot find the artist#portrait of jane seymour by hans holbein the younger#the sorceress by georges merle#portrait of a young woman by nicolaes eliasz pickenoy#portrait of a man by jan gossaert#portrait of johanna martens by paulus moreelse#cant find artist but the portrait is of camilla martelli#eleanora di toledo by angolo bronzino#portrait of pope julius ii by raphael#young lady by alessandro allori#princess albert de broglie by jean auguste dominique ingres#monna pomona by dante gabriel rossetti#portrait of a young zaraysk merchant woman by unknown#portrait of tomas de iriarte by joaquin inza#cant find the artist of this one#female saint holding a book by amico aspertini#looked everywhere but couldn't find artist#can't find artist#painting by lorenzo lotto#maria josepha amalia by francisco lacoma y fontanet#salome by leopold schmutzler#cant find artist nor painting name#a man with a pansy and a skull by unknown#cant find artist or painting#painter is juan pantoja de la cruz#portrait of a lady by william scrots#painter is gustave jean jacquet#portrait of a woman by maybe marie schuurman#portrait of a lady by gortzius geldorp

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Pope Julius II by Raphael, 1511.

#classic art#painting#raphael#italian artist#16th century#portrait#male portrait#indoor portrait#pope julius ii#pope#clergy#chair

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

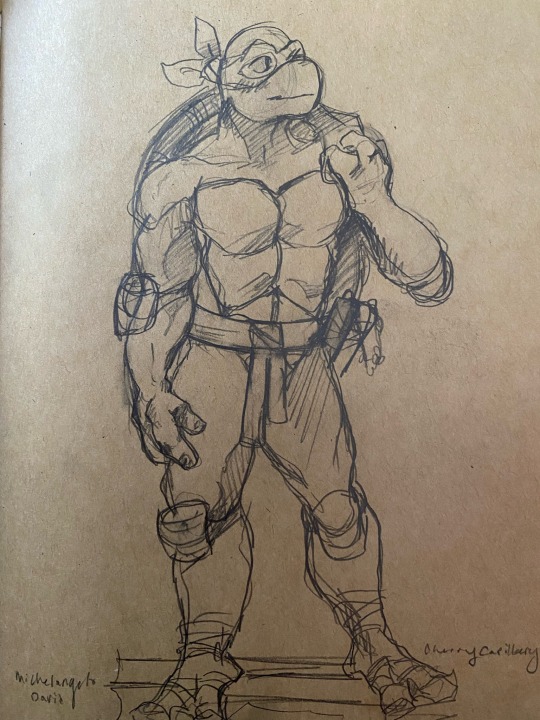

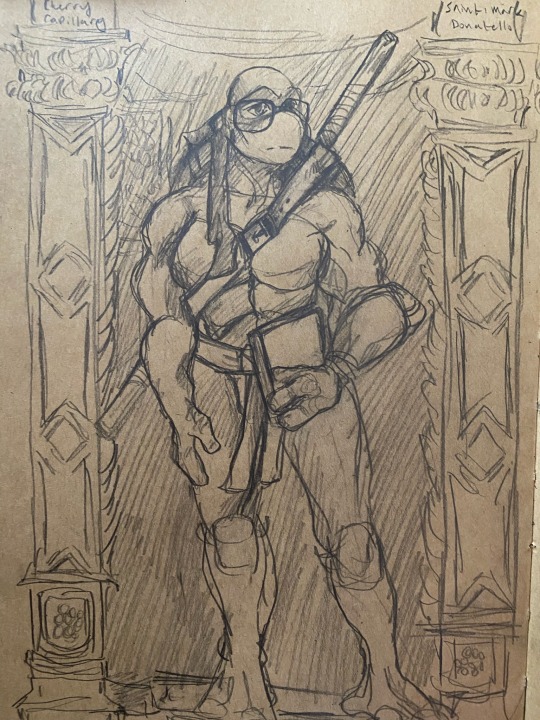

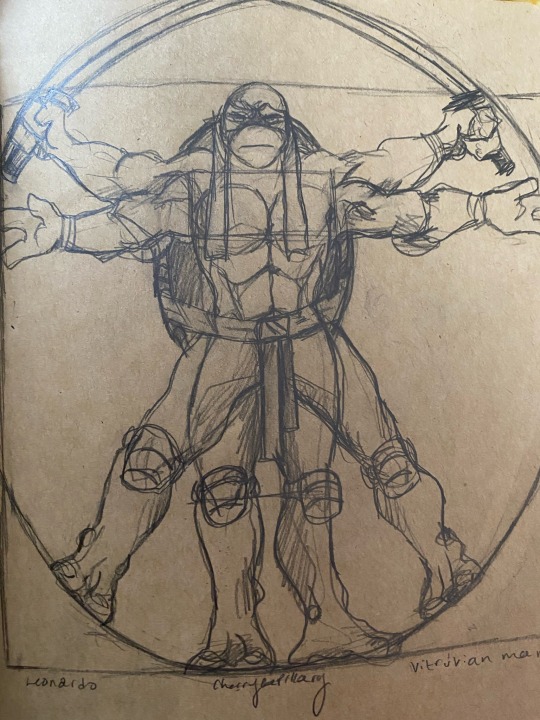

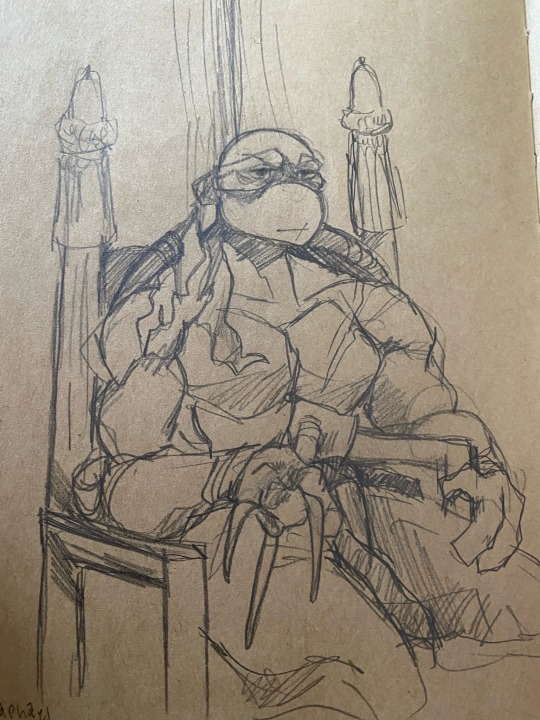

mikey as michelangelo’s david

donnie as donatello’s saint mark

leo as leonardo’s vitruvian man

raph as raphael’s portrait of pope julius ii

#my art#traditional#tmnt#teenage mutant ninja turtles#leonardo#donatello#michelangelo#raphael#portrait of pope francis ii#vitruvian man#saint mark#david#sketch#traditional art

876 notes

·

View notes

Text

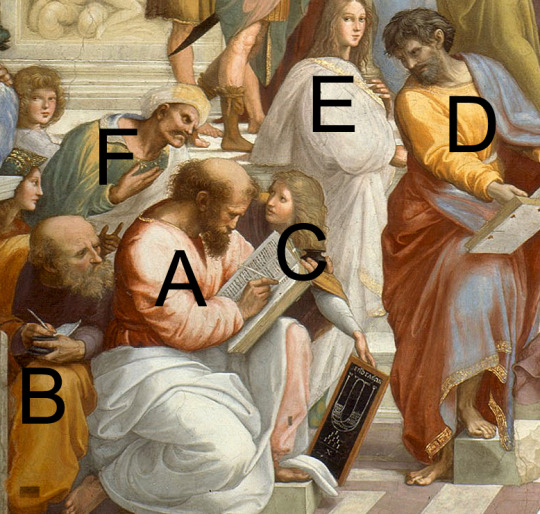

Who painted 'The School of Athens'?

One of the most famous of Raphael’s paintings for the Vatican Palace is 'The School of Athens', painted between 1509 and 1511. The masterpiece reflects the growing interest in Ancient Greek Philosophy in Rome at the time. Several of the figures in the scene have been identified by art historians, including a self-portrait of Raphael posing as Apelles of Kos, a 4th century BC painter.

In the centre of 'The School of Athens', the Greek philosophers Aristotle and Plato are seen in conversation. Plato points his hand towards the sky, signalling his idealism and abstract thinking, while Aristotle gestures at the ground, referencing his study of the natural world and human behaviour. In his other hand, Plato holds a copy of 'Timaeus', a dialogue that responds to the opinions of other scholars. Similarly, Aristotle holds a copy of his 'Nicomachean Ethics', which had a profound influence on Europeans during the Middle Ages. Around Plato and Aristotle, other philosophers are engaged in debates about their ideas and theories.

Raphael was commissioned to paint 'The School of Athens' and many other frescoes by Pope Julius II. Julius was responsible for rebuilding St. Peter’s Basilica and the establishment of the Swiss Guards. When Julius died in 1513, he was replaced by Leon X (1475-1521), who continued to oversee Raphael’s progress in the Vatican Palace.

On Good Friday, 6th April 1520, Raphael passed away after developing a sudden fever. He was only 37 years old.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

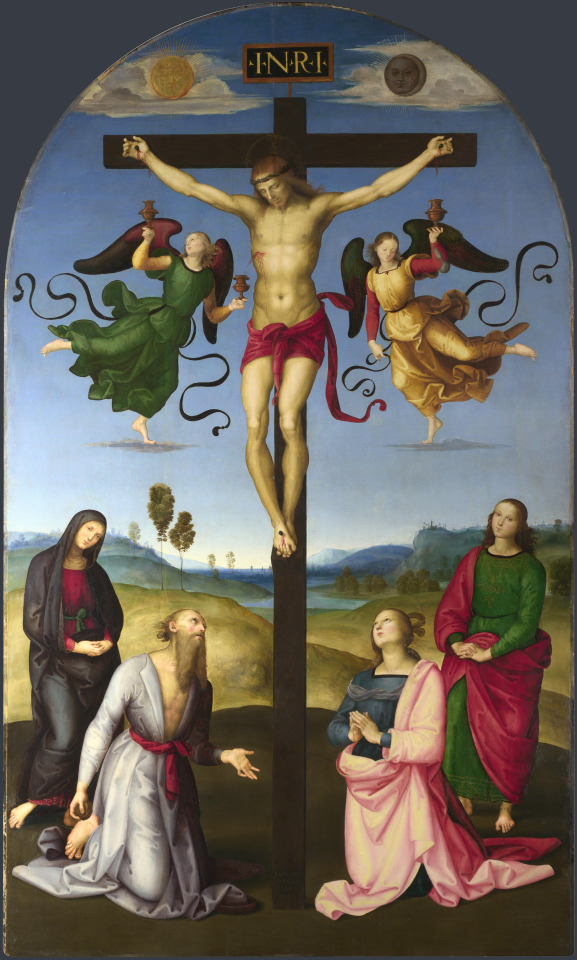

Mond Crucifixion (Raphael)

Portrait of Cardinal Alessandro Farnese (Raphael)

Saint George and the Dragon (Raphael)

Portrait of Pope Julius II (Raphael)

0 notes

Text

youtube

The Disputation of the Holy Sacrament (Raphael 1509-1510) depicts theologians debating, with Pope Gregory I and Jerome on the left, and Augustine and Ambrose on the right, Pope Julius II, Pope Sixtus IV, Savonarola and Dante Alighieri

The fresco can be seen as a portrayal of the Church Militant below, and the Church Triumphant above. A change in content between a study and the final fresco shows that the Disputa and The School of Athens can be seen as having a common theme: the revealed truth of the origin of all things, in other words the Trinity. This cannot be apprehended by intellect alone (philosophy), but is made manifest in the Eucharist.

The painting is built around the monstrance containing the consecrated Host, located on the altar. Figures representing the Triumphant Church and the Militant Church are arranged in two semicircles, one above the other, and venerate the Host. God the Father, bathed in celestial glory, blesses the crowd of biblical and ecclesiastical figures from the top of the composition. Immediately below, the resurrected Christ sits on a throne of clouds between the Virgin (bowed in adoration) and St John the Baptist (who, according to iconographic tradition, points to Christ). Prophets and saints of the Old and New Testament are seated around this central group on a semicircular bank of clouds similar to that which constitutes the throne of Christ. They form a composed and silent crowd and, although they are painted with large fields of colour, the figures are highly individuated.

At the bottom of the picture space, inserted in a vast landscape dominated by the altar and the eucharistic sacrifice, are saints, popes, bishops, priests and the mass of the faithful. They represent the Church which has acted, and which continues to act, in the world, and which contemplates the glory of the Trinity with the eyes of the mind. Following a fifteenth century tradition, Raphael has placed portraits of famous personalities, both living and dead, among the people in the crowd. Bramante leans on the balustrade at left; the young man standing near him has been identified as Francesco Maria Della Rovere; Pope Julius II, who personifies Gregory the Great, is seated near the altar Dante is visible on the right, distinguished by a crown of laurel. The presence of Savonarola seems strange, but may be explained ...

0 notes

Photo

Wolfgang Tillmans, Kate sitting, 1996

VS

Raffaello Sanzio, Portrait of Pope Julius II, 1511-1512

#wolfgang tillmans#portrait#kate#kate mos#fashion#model#supermodel#photography#contemporary art#modern art#raffaello#raffaello sanzio#raphael#julius ii#giulio ii#pope#papa#green

153 notes

·

View notes

Text

When You Are Old

by William Butler Yeats

WHEN you are old and grey and full of sleep,

And nodding by the fire, take down this book,

And slowly read, and dream of the soft look

Your eyes had once, and of their shadows deep;

How many loved your moments of glad grace,

And loved your beauty with love false or true,

But one man loved the pilgrim Soul in you,

And loved the sorrows of your changing face;

And bending down beside the glowing bars,

Murmur, a little sadly, how Love fled

And paced upon the mountains overhead

And hid his face amid a crowd of stars.

Raphael 1511-12 Portrait of Pope Julius II, Oil on wood, National Gallery, London, Uffizi

#When You Are Old#William Butler Yeats#WB Yeats#Yeats#Portrait of Pope Julius II#Raphael#Old Age#Julius II#Art#Poetry#Fine Arts#Poems#Painting

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Portrait of Pope Julius II, 1512, Raphael

Medium: oil,poplar

https://www.wikiart.org/en/raphael/portrait-of-pope-julius-ii

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Raphael - Portrait of Pope Julius II, 1511–12

#raphael#italian renaissance#high renaissance#raffaello sanzio da urbino#italian painter#15th century#julius ii#religious art#catholic church#catholicism

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

130 lire Bramante's Design for Spiral Staircase single

On February 22, 1972, Vatican City issued three stamps commemorating the architect Donato Bramante.

Donato Bramante was born circa 1444 in Monte Asdrualdo, Italy. He is best known for his plan for the construction of the new Basilica of St. Peter. The new St. Peter's was to enclose the gigantic tomb of Julius II (1443-1513), which Michelangelo was to design and sculpt. However, the condition of the old St. Peter's demanded the immediate construction of a church, and Bramante laid the cornerstone of the first of the four great pillars in 1506. By 1507, all four piers for the pillars were in position. It was planned to take the form of a Greek cross, with alternate plans for a Latin cross floor plan. Bramante saw only the beginning of his plan executed because he died at Rome in 1514. Bramante's work on St. Peter's Basilica was followed by architects Fra Gioconda, Raphael, San Gallo and Peruzzi, and Michelangelo. Michelangelo raised his own dome on the pillars.

There are three stamps in the series:

25-lire - cutaway design for the dome of St. Peter's

90-lire - medallion with portrait of Bramante

130-lire - cutaway of a section of Bramante's spiral staircase for the Belvedere of Pope Innocent VIII

The stamps are forty to a pane in a 1,600,000 series. The stamps have unlimited validity. The stamps are buff color by rotogravure and black printing by engraving.

https://postalmuseum.si.edu/object/npm_2008.2009.519

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Madonna della Seggiola by Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino

“Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino, an Italian painter and architect of the High Renaissance movement, was so well-known and renowned as a painter during his lifetime he was known simply by his first name, Raphael. He is known so today by only his first name and a master painter during the Italian Renaissance. His contemporaries were Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci. Together these three form the triumvirate of master artists and genius' from this same period of art.

Throughout his short lifetime, Raphael, who died at the age of only thirty-seven, painted many portraits, frescos, and stanzes (room paintings) and left a legacy of prolific works to his adoring public. His paintings are known for their visual achievement of the classical antiquities and the ideal of human grandeur.

His name has become synonymous with 'classical' and his genius was in strengthening and refining painting techniques rather than technical innovation. His paintings show elements of grace and refinement because of the influence of his early teacher, Perugino. There is a subtle elegance to his figures and sweetness in his female faces.

While the paintings and frescos of Michelangelo are bold, wild and unconventional, Raphael maintains a strict attention to the artistic rules and techniques in his paintings. There is a grandeur that is not found in Michelangelo's or da Vinci's paintings as there is in Raphael's.

Raphael's paintings have a more serene and harmonious quality to them and they were regarded as the highest painting models to emulate during the Renaissance period. This was much to the consternation of Michelangelo and caused much friction and inner conflict for Michelangelo.

He is best known for his stanze, or room, paintings done in the Papal apartments at the Vatican in Rome, Italy, and these are the greatest masterpieces left behind by Raphael today. He is best known for his stanze, The School of Athens, his finest and most perfect fresco left behind.

His early series of Madonna paintings, painted while he lived in Florence, are also considered the best in the world even today.

"Wedding of the Virgin", one of Raphael's early completed altarpiece frescoes.

Early life

Raphael was born in Urbino in the central Marche region of Italy. His father was Giovanni Santi, a court painter and poet to the Duke of Urbino. Therefore, Raphael grew up in this Italian court, known to set the model throughout Italy for its grace and manners. Here, Raphael learned excellent, refined manners and social skills. He mixed easily with the highest circles throughout his life because of his father's position at court.

His father is said to have apprenticed him out to the Umbrian artistic workshop of Piero Perugino who was an early influence in Raphael's paintings and other artistic pursuits at the young age of eight. This was a rare occurrence at such a young age, but Raphael's mother, Magia died in 1491, when he was eight. It is believed his father, busy with his own workshop, wanted Raphael busy during his days without his mother.

Perugino's workshop was active in both Perugia and Florence and Raphael was a master of Perugino's workshop and fully trained when he left.

Three years later, Raphael's father died and at the young age of eleven, along with his step-mother, he successfully took over and ran his father's workshop. By now, Raphael was a master painter and so began painting frescoed altarpieces at churches around Umbria. Some of these only partially survive today.

Wedding of the Virgin, pictured above, is Raphael's most sophisticated altarpiece he painted from this period of his paintings.

"Madonna della Sedia" (The Virgin Enthroned) 1516-17. Part of Raphel's Madonna series.

Florence 1504 - 08

Raphael spend these years living and working in Florence, Italy and this is known as the 'Florentine period' of his art. Here Raphael was greatly influenced by Leonardo da Vinci and his paintings.

Raphael's painted figures began to take more dynamic and complex positions. His drawings of portraits of young women used da Vinci's three quarter length pyramidal composition as seen in da Vinci's Mona Lisa.

Raphael continued with his tranquil paintings but he also branched out into drawings of fighting nude men so popular at this time in Florence. He also perfected da Vinci's sfumato technique to give subtlely to his painting of flesh on canvas. He also developed the interplay of glances between his groups of figures but they are much less enigmatic than those of da Vinci.

This was Raphael's period of painting Madonnas and though he assimilated da Vinci's techniques in his paintings he kept the soft clear light in his paintings he had learned from Perugino as a youth. His Madonnas portray a tender humanity along with the divine that shines forth in these paintings. The subtle use of colors and the sfumato technique are evidence of da Vinci's influence in his paintings.

Raphel also adapted the lessons of tone, color and light from da Vinci and then added his grace and harmony to his faultless paintings.

In his painting, Depostion of Christ (1507), Raphael draws on a classical sarcophagi for his composition. He spread his figures across the front of the canvas space in a complex and not wholly, successful arrangement. So, although, he was influenced by da Vinci, not every painting included da Vinci's techniques.

The Madonna della Sedia, pictured above, although painted after his period in Florence, is still considered one of Raphael's great Madonnas. It has the perfect balance of curving forms in round frame and the harmonious colors are not rich and glowing but subtle yet full. This Madonna shows perfect balance, harmony, and untroubled radiance.

Within these four years in Florence, Raphael had achieved so much success that he was now a well known painter throughout Italy and all of Europe and became very popular with the public.

"Stanza della Segnatura", 1511, one of the "Raphael rooms" he painted in the Papal apartments and Sistine Chapel. To the right is his famed "School of Athens" the most famous and renowned fresco painted by Raphael.

Rome 1508 - 20

Raphael moved to Rome in 1508 at the request of Pope Julius II and he was commissioned to fresco paint the Papal apartments and the walls of the Sistine Chapel. Meanwhile, Michelangelo was painting the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

This is when Michelangelo began his great dislike in Raphael and his paintings, believing that Raphael and the Pope were conspiring against him. Michelangelo even went so far as to accuse Raphael of plagiarism, but his accusations were not taken seriously.

Raphael's stanze paintings, or room paintings, in the papal apartments and Sistine Chapel are considered the great masterpieces by Raphael. These paintings show all the gatherings of High Renaissance principles and techniques Raphael used in his paintings. They represent the intellectual reconciliation of Christianity and classical antiquity.

The School of Athens, 1509-11, is Raphael's first history painting and it is near perfect in composition and construction The perfect structure of reason built by the classic philosophers is symbolized by the architecture of the paintings. Raphael, who bore Michelangelo no ill will, even painted Michelangelo in this fresco as Heraclitus.

Raphael completed a sequence of three rooms in the papal apartments each with paintings on each wall.

With the death of Pope Julius II in 1513, the succeeding Pope Leo X kept Raphael on and commissioned him to not only paint but as architect and archaeologist. Raphael at one point was named the architect of St. Peter's for the papal court. But, it is his masterpiece paintings and frescos that are his greatest legacy.

His frescoes display harmony, movement within strict symmetry and the merging of the real and the ideal. In his later stanzes we see Michelangelo's influence. In The Expulsion of Heliodorus (1511-13) we see the beginnings of the Mannerist and Baroque movements, with the dramatic contrasts of light and dark and the stronger and richer colors of those movements.

In painting these rooms, Raphael achieved 'sprezzatura' which is a certain nonchalance that conceals all artistry and makes whatever he painted to look uncontrived and effortless. It was this 'effortlessness' of Raphael's paintings that drove Michelangelo mad with jealousy.

Raphael died suddenly at the age of thirty-seven after a brief illness. His last painting, The Transfiguration (1520), was left unfinished and eventually completed by his pupils of his workshop.

Raphel had never married, but in 1514 became engaged to a Maria Bibbiens. It is unknown why they never married, but it is believed Raphael had a mistress, Margherita Luti.

With the death of Raphael came the end of the High Renaissance movement in painting and the Mannerism movement began. Michelangelo was named architect of St. Peter's and he discarded Raphael's designs for the great basilica and created his own.

Raphael was buried in The Pantheon in Rome at his bequest and his funeral was large, grand and attended by large crowds of his public who adored him.

Giorgio Vasari, the 16th century art historian and artist in his own right, called Raphel 'the prince of painters' for the simple yet majestic dignity of his paintings.”

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Лондонская Национальная галерея

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

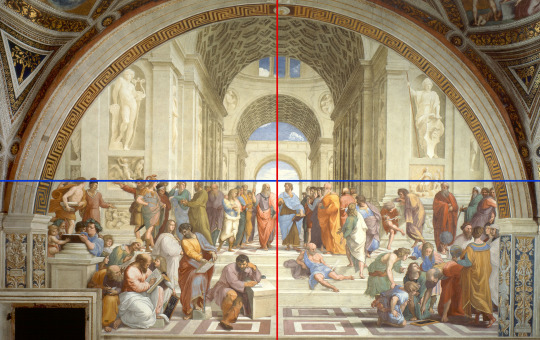

ANALYSIS of The School of Athens

Denada Permatasari. 6 November 2017.

Fig 1.0 Fresco of Raphael's Scuola di Atene (The School of Athens), 1509-11 (courtesy of the Musei Vaticani).

The School of Athens by Raphael Sanzio, or more accurately, Raphael and his studio. This elaborate wall mural is a fresco in the Stanza della Segnatura, Vatican. Measuring 584 cm in length, this artwork was made in 1509 and finished in 1511.

I think that this artwork is a phenomenal masterpiece. From a technical standpoint, it is no debate that the scale and the mastery of human figures are impressive. Every single aspect is carefully planned, apparent from the detail of the backdrop to the individually distinctive figures present in the artwork. The symbolism in this work represent the core of Philosophy through subtle means of the wall division, the composition, down to the character’s body language, where they are situated, and even from the clothes they wear. In this essay, I discuss what all of the previously-stated elements mean and how they come together to give this artwork its meaning, and its significance.

Before delving into analysis of the artwork’s components, it is important to discuss why this artwork was made. This wall mural is part of Pope Julius II’s commission to decorate his private library (Zucker and Harris). The room has four sides, with each side representing the four branches of human knowledge at the time of High Renaissance: Philosophy, Divinity, Poetry, and Justice. The School of Athens, located on the east wall, represents Philosophy and is directly facing Disputa, representing Divinity (Zucker and Harris).

This placement, and the fact that this artwork is no less impressive than Disputa, can be seen as one of the defining attitudes of the High Renaissance: secularization. Here, the religiosity and philosophy are seen as equals, alongside poetry and justice. This is a big step from pre-Renaissance times when religion tended to dominate and rule above all aspects of life (qtd. in Toman iii).

Fig 1.1 Imagined horizontal and vertical lines of The School of Athens.

Moving on to the aspects of form of the artwork itself, I will first talk about its composition. In Fig 1.1, it is shown from the horizontal blue line that “… below the vaulted architecture and celestial backdrop, [Raphael] set the assembly of philosophers in the lower half field, on earth” (Rosand). This means that Raphael deliberately separated man, who is concrete and earthly, from the abstract.

Fig 1.2 Areas of interest in The School of Athens, as labeled with numbers.

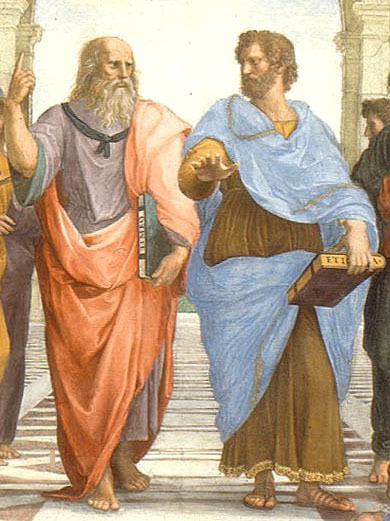

Next, the vertical red line between the two figures in the center of the artwork (Area 1 in Fig 1.2). This imagined line serves as a divider for the opposing school of thoughts in Philosophy: Plato, the older man on the left, represents the ethereal and the abstract. He represents the belief that “… there is a realm that is based on mathematics, on pure idea that is truer than the everyday world that we see” (Zucker and Harris). Whereas Aristotle, the younger man on his right, represents the belief “… on the observable, the actual, [and] the physical” (Zucker and Harris).

This divide can be seen from the other characters’ placement in the artwork. In Area 2 (Fig 1.2), which is Plato’s side, are a cluster of people who are also concerned who explains the world from an abstract, cosmic lens (Rosand). This is contrasted by the group of people (Area 3) in Aristotle’s side, who explains the world through factual and concrete means (Rosand). I shall explain how I know the aforementioned observations through analyzing the elements, aspects of form, and the identity of each figure that makes up The School of Athens.

Fig 1.3 Zoom in of Plato and Aristotle.

First, the two main figures (Fig 1.3) in the center of the fresco (Area 1). They are separated from the others by the arc frame of the background. I have said before that the older man on the left is Plato, and the younger man is Aristotle, Plato’s pupil. They are also holding their own books, Plato with his Timaeus, and Aristotle with his Ethics. This section of the essay will highlight how the subject matter and design elements reflect the meaning of the divide in schools of Philosophy.

Plato, representing the ideal and the abstract, wears purple and red. “… The purple, referring to the ether, what we would call the air, [and] the red to fire, neither of which have weight” (Zucker and Harris). Whereas “Aristotle wears blue and brown, that is colors of earth and water, which have gravity [and] weight” (Zucker and Harris). This contrast between the abstract versus the concrete is further compounded by their body language: Plato, pointing up to the heavens, to the realm of high thinking, his bare feet just merely planted on the ground. Aristotle, his hand splayed downwards to the ground, wearing gilded sandals, feet firm on the tiles (Rosand).

Second, the homage to ancient antiquity, apparent in the pagan sculptures of Apollo on the top left and Athena on the right (Rosand). The design of the architecture, with coffered barrel vaults, pilasters, et cetera, is ancient Roman design as well. The god and goddess of the ancient times only reinforce the conceptual divide of the artwork, with Apollo, the god of music and poetry, things that are appropriately platonic (Rosand). Then there is Athena, the goddess of war and wisdom, who is more involved in the practical affairs of man (Zucker and Harris).

The architecture design, which is equal throughout the artwork, represents the unifier in this artwork full of divides. They serve as a reminder that even though there is a fundamental divide in perspective, all of them are still under the same branch, Philosophy (Rosand).

Fig 1.4 The labeling of figures in Plato’s side using capital alphabets from A to F.

Third, the groups of people on Plato’s lower side in Area 2 (Fig 1.2). These figures are labeled with letters (Fig 1.4). Though the identities of many of the figures here is much debated, since Raphael did not leave any notes or annotations, let’s agree for the sake of discussion that:

A: Pythagoras, a Greek philosopher and mathematician who is arguably in the center of this group gathering. He sought to discover the mathematical principles of reality through musical harmony and geometry (Rosand).

B: Boethius, a Greek philosopher who wrote The Consolation of Philosophy (Lahanas).

C: Anaxagoras, a Greek philosopher that correctly explains solar eclipses and the presence of small particles (atoms) in all objects (Agutie).

D: Parmenides, a Greek philosopher who founded the method of reasoned proof for assertions (Agutie).

E: Hypatia, an Alexandrian philosopher, mathematician, and astronomer. She is considered to be the most famous student in the School of Athens (Lahanas).

F: Ibn Rushd (Latin: Averroes), a Spanish-Arab philosopher who wrote commentaries on almost all of Aristotle’s writings and major works of Plato (Agutie).

All of the figures in this cluster are concerned with the cosmic, bigger-picture truths, echoing Plato’s ideals. Moreover, two figures in this cluster deserve special attention: Hypatia and Ibn Rushd. Hypatia’s placement in Plato’s side is reminiscent of Plato’s principle of women’s equality (Fakhry), in fact she is the only woman in the whole artwork. On the other hand, Ibn Rushd’s placement in Plato’s side is curious, since he is more associated with Aristotle’s works more so than that of Plato’s (Fakhry). Even so, Raphael must be commended for including a woman as an equal with men and a Muslim figure, which was seen as radical and out of line in his era.

Fig 1.5 The labeling of figures in Aristotle’s side using capital alphabets from G to J.

Fourth, the group that represents Aristotle’s way of thought in Area 3 (Fig 1.2), concerned with the physical and the concrete. They are labeled with letters (Fig 1.5), with identities as follows:

G: Euclid, a Greek mathematician. He is the father of geometry and is seen bent down, applying geometry with a compass to a tablet, flat on the ground (Rosand).

H: Zoroaster, a Greek astronomer, founder of Zoroastrianism, holding a celestial orb (Agutie).

I: Ptolemy, the royal astronomer, who was the first to believe that all heavenly bodies revolve around the earth (Agutie).

J: Raphael, the artist himself in black, and his mentor in art, Sodoma, in white (Lahanas).

The figures in Aristotle’s side are arguably more interesting than Plato’s, as there is more diversity in terms of the principles that the figures represent. Of course, they are all still united in their more earthly and human-centric concerns, but the inclusion of the artist’s self-portrait is the main highlight of this area of interest. For Raphael to include himself is a historical statement, as stated by Dr. Beth Harris, “… here, the artist is considered an intellectual, on par with some [of] the greatest thinkers in history” (Zucker and Harris).

Fig 1.6 Zoom in detail of Heraclitus.

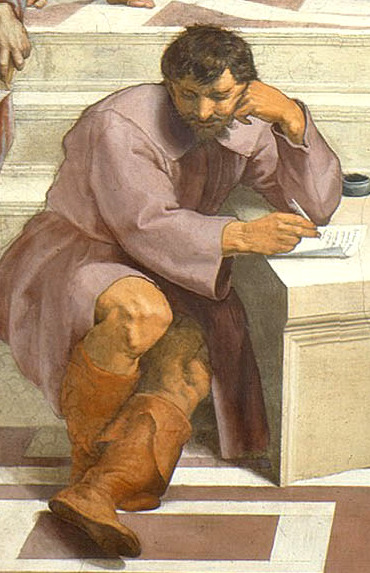

Last, but certainly not least, is the lone figure of Heraclitus (Fig 1.6), an ancient philosopher that sits and thinks alone, separated from the others (Area 4 in Fig 1.2). What makes this figure stand out is the fact that he is a deviation from the orthogonal perspective of the whole artwork. Apart from Diogenes, who is sprawled on the steps, also by himself, Heraclitus feels out of place in the artwork. This is because Heraclitus was actually added after the fresco was finished (Rosand).

At this point, I will discuss the personal aspect that Raphael weaved throughout this commission; Heraclitus’ figure is one of them. The model for this ancient philosopher is actually based off of Michelangelo, and this insertion, this acknowledgment of the older artist is very curious in of itself. The personal antipathy between them is well known; Raphael, the sociable and cultured artist was intensely disliked by Michelangelo, the brooding and melancholic artist, who accused him of stealing his ideas from the Sistine ceiling (Hale 274). For Raphael to include him in his impressive fresco can be said as an homage or a tribute to Michelangelo (Rosand). This speaks of Raphael’s respect and regard for the other artist despite their differences.

Heraclitus is not the only figure who is modeled after someone else –in fact, most of the major figures in this artwork are modeled after someone else- take, for instance, Plato who is actually modeled after Leonardo da Vinci (Toman 336), an artist that highly inspired Raphael. For him to model Plato, the central figure of his fresco and one of the greatest thinkers of all time after Leonardo is a significant honor to his person. Another instance is Euclid. The geometer is actually modeled after Bramante the architect, Raphael’s friend and professional companion (Toman 336). His tribute for Bramante doesn’t end there; the architectural design of the background is actually inspired by Bramante’s architectural design and vision (Martindale 83).

All of the analysis of the components, and how even the smallest things contribute to a greater meaning, is the main reason why I think this artwork is phenomenal. If anything is to be obvious from my essay, is the amount of planning, effort, and thoughtfulness that Raphael did for this fresco. For me, personally, there is nothing more impressive than a successful execution with an underlying concept that is well thought of in every step of the way. In this, I am very pleased with Raphael’s technical skill to make something so legible on an intimidating scale, yet still retaining a degree of thoughtfulness that is apparent in every single dot of his fresco.

To further compound this, I am not the only one who thinks that this artwork is extraordinary. The School of Athens has received high regard from the moment of its completion, even until the present day. The Stanza della Segnatura has been a famous tourist attraction because of the wall frescoes that Raphael made, and The School of Athens is arguably the main attraction in the Vatican Palace.

Most importantly, however, is Raphael’s own influence on the High Renaissance, and what follows after. As Johan Huizinga, a Dutch art historian has stated:

The Renaissance marks the rise of the individual, the awakening of a desire for beauty, a triumphal procession of joyful life, the intellectual conquest of physical realities, … a dawning of consciousness of the relationship of the individual to the natural world around him (qtd. in Toman i).

To attribute all of those values of the Renaissance to just The School of Athens is optimistic at best and naïve at worst, but it is worth acknowledging that The School of Athens is one of the main highlights of the High Renaissance, and certainly sums up the entirety of the High Renaissance. In this light, Raphael deserves much acclaim, as written by Luitpold Dussler in his book Raphael:

Raphael has left an indelible mark on art. He revolutionized portrait painting … and epitomized the style which has come to be known as High Renaissance. … Perhaps Raphael’s greatest achievement is that he appeals on all levels and makes something profoundly deep and complex appear simple and comprehensible (qtd. in Hale 275).

In conclusion, the value of Raphael’s The School of Athens is that it is invaluable. It was significant by the time it was completed, and is still significant even today, more than five hundred years later. More than just a room decoration, it speaks of the general perspective of Philosophy during the early 16th century. Raphael’s ability to condense such a difficult, multi-faceted discipline into a thoughtful work of art that can be appreciated by anyone, at any level, is a testament to his remarkable technical skill and conceptual knowledge.

I will end my essay with one conviction: that The School of Athens is one of the definitive artworks of the High Renaissance, and I hope that the significance of attributing an entire period to one single artwork is realized and acknowledged.

Works Cited

Zucker, Steven and Beth Harris. “Raphael, School of Athens.” Smarthistory. 27 Jul. 2014. 3 Nov 2017.

Toman, Rolf. Introduction. The Art of the Italian Renaissance. Germany: Könemann, 1995. Print. i, iii, 336.

Rosand, David. “Raphael’s Fresco of The School of Athens in the Stanza della Segnatura of the Vatican Palace.” Columbia University. New York. N.d. 3 Nov 2017.

Lahanas, Michael. “The School of Athens, ‘Who is Who?’ Puzzle.” Hellenica World. N. d. 3 Nov 2017 <http://www.hellenicaworld.com/Greece/Science/en/ SchoolAthens.html>.

Agutie. “Raphael (1483-1520): The School of Athens, 1509. Interactive Map.” Geometry from the Land of the Incas. 13 Jul 2014. 3 Nov 2017 <http://agutie.homestead.com/files/school_athens_map.html>.

Fakhry, Majid. Averroes (Ibn Rushd) His Life, Works and Influence. London: Oneworld Publications, 2001. N. p.

“Raphael.” Encyclopaedia of the Italian Renaissance. Ed. J. R. Hale. Lindon: Thames and Hudson,1981. Print. 274-275.

Martindale, Andrew. Man and the Renaissance. London: Paul Hamlyn Limited. 1966. Print. 83.

#raphael#the school of athens#athens#fresco#mural#renaissance#art#stanza della segnatura#vatican#city#plato#aristotle#scuola di atene#essay#analysis#heraclitus#michelangelo#philosophy#steven zucker#beth harris#rolf toman#david rosand#michael lahanas#agutie#majid fakhry#andrew martindale#italy#italian#malphigus#malphiguswrites

38 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Portrait of a Cardinal is a painting by the Italian Renaissance artist Raphael. It is housed in the Prado Museum in Madrid. It depicts an unidentified cardinal in the court of Pope Julius II. The portrait was acquired by Charles IV of Spain when he was still a prince, and the picture was attributed to Antonio Moro, due to its technique, considered unusual in Raphael. [Oil on wood, 79 x 61 cm]

3 notes

·

View notes