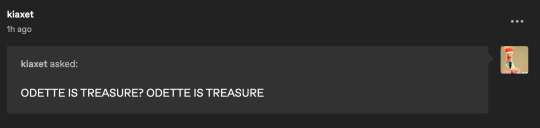

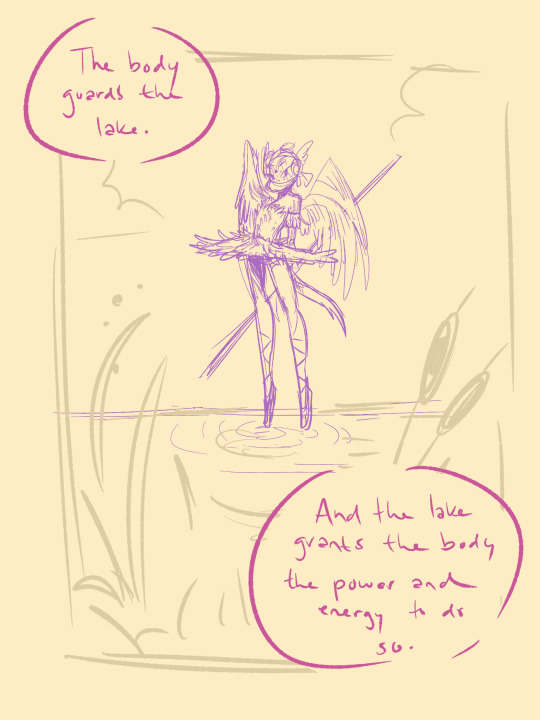

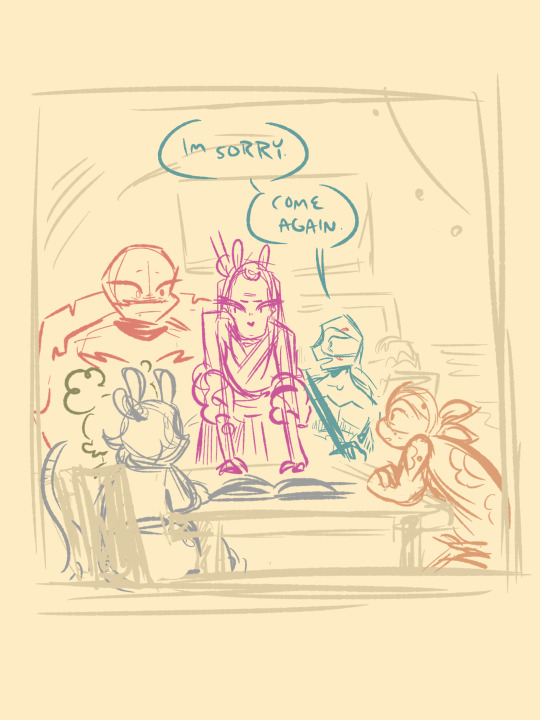

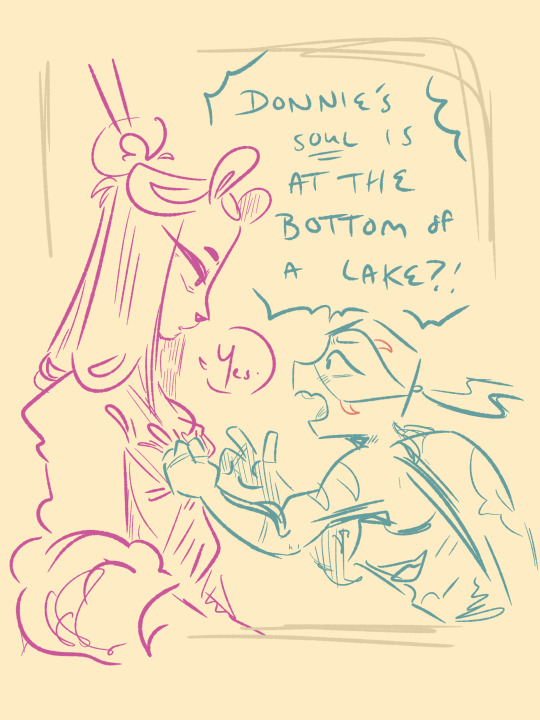

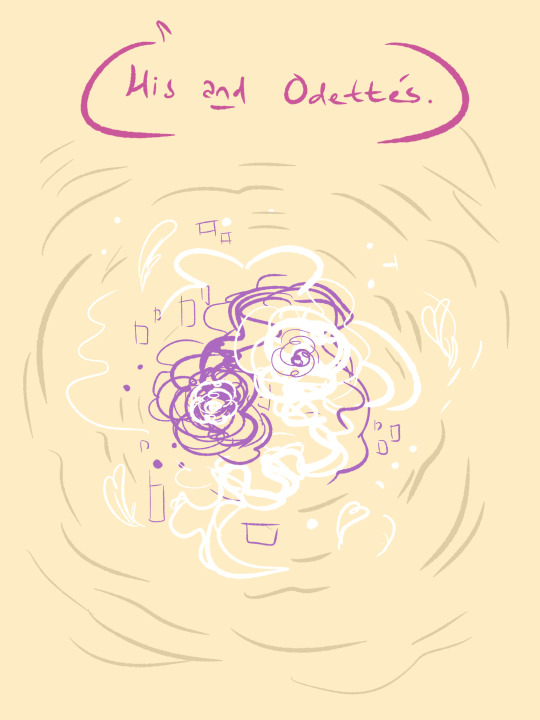

#now are those false memories and other cognitive changes kind of starting to make sense...?

Note

So.... Wait, I'm thinking Donnie may have perhaps confused Odette and Othello together, and because he was responding to it, it triggered something? Just a hunch.

i love it when you guys are right, it's fun.

swanatello.

[ start ] [ prev ] [ next ]

#yeah! swannie is the treasure#kind of#but only because#really#odette is#swanatello#rottmnt#rottmnt au#rottmnt donnie#rottmnt donatello#rottmnt fanart#tmnt#tmnt 2018#rise of the teenage mutant ninja turtles#rise of the tmnt#rottmnt comic#donniesona#fidgetwing#comic#now are those false memories and other cognitive changes kind of starting to make sense...?

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

I think if I had a recognisable writing quirk, a signature of sorts, something that’s recognisably me each time I write... it’d probably be that I never shy away from the consequences of traumatic events, but I also don’t shy away from showing the characters healing.

One of the things I love so much about P5R is how the fandom really gets how the characters - not just the protagonist, but all of them! - have trauma. Palaces as a concept (when used with Akira and/or Akechi) are all about recognising said trauma, and healing from it.

Some of my fics go into this more than others - Cognitive Resonance has the core of the story being Akira pushing everyone away because he’s afraid of how they’ll see him at his lowest points, and having to heal in order to let anyone back in (even Akechi).

Harisen Recovery and “A Little Too Good To Not Be True” are both the idea of “what if Akira was suckered into the false reality, and kept having trouble being sure what’s real after breaking Maruki’s control.” Both of them deal with the aftermath of him not being able to tell anyone when he’s affected, and the courage it takes to talk about it, and especially the coping mechanisms he’d use to remind himself of what’s real.

In Pyrrhic Victories, Akechi has to live with the realisation that his victory was meaningless, and that he has all of the memories of hurting someone he grows to care for even more than he did before.

I have a NG+ role swap AU in the works where one of my favourite things for it is that the boys have a future, one where they’re able to be happy even if they are changed and they’re never going to get back who and what they were.

And talking of NG+ ideas... all this came up because I was reminded of this one idea I’ve never yet written (though given my current feelings, I may be going back to it).

Akira, having gone through an indeterminate amount of time either looping to the start or back to a prior safe room or just a single loop, just... he’s been living parts of the same year for a while now. But he’s already out, and Akechi comes to visit his hometown to tell him that he’s alive after Maruki, and at some point in their conversation the whole “Akira is a time traveller” thing comes out. He remembers things he shouldn’t. More than that, he’s deathly afraid that he’s going to reach a point where he does something wrong and wakes up a week or two in the past. Or he walks down a familiar street at night and he’s back on the night he first got arrested. Or he’ll wake up on the train to Shibuya, and he’ll have to do everything all over again.

And to be honest, as much as I love NG+ time travel stories, this is a big thing that I think gets left out of a lot of them. The sense of - when does it end? Can we be sure it does? Not knowing that a cycle has been broken is a specific kind of horror. There’s no future, because there’s only the past. Nothing you do makes a mark on history, because for you, the world ends and begins with the loop. You can never be sure that the world outside of it moves on without you. If it goes far enough that a person has children, does going back in time erase those children? Does it mean they’ll never be born, or that they’ll grow up into a totally different person?

For my own story, I liked the idea of Akechi being the point of view character, having this horror of realising what his rival had been going through without telling anyone up until now (or has he? was there a time when he tried, and it failed? or did it work, and he had to leave that behind?) and, in spite of not having wanted to get back into contact with the Thieves more than necessary, texts Futaba and tells her that they need to get Akira back to Tokyo, because all he has in his hometown is basically silence and Morgana, and Morgana isn’t enough.

(Sometimes, the hope that things will work out and that tomorrow will be tomorrow isn’t enough.)

So, Akira coming back and having everyone support him, remind him that he’s moving forward. Get him tools to help if he ever does get sent back, even if everyone hopes it never happens, because it’s like giving a kid a stick to fight off dragons with (and if the dragons are real - they have a stick to fight with).

Just... if someone’s had something traumatic happen to them, the break isn’t going to happen immediately. And it’ll be like earthquakes, with tremors and aftershocks. Like grief, it comes in waves.

This is one of the reasons I love hurt/comfort, because if I’m gonna traumatise my characters, then no way am I just going to leave them like that! It’s like impaling someone. If I leave them in the situation, it’s like leaving the object inside of them. If I take them out of the situation but I don’t give them the ability to heal from it, it’s like yanking it out and letting them bleed to death. But if I take them out of the situation, if I give them a support network, if I tell them it’s okay to hurt but to say when it’s hurting so that people can help... that’s basic first aid. That’s making sure they don’t die (or, just that they don’t fall into despair, time and time again, or break into something less.)

I see the term “kintsugi” used in terms of letting emotional scarring heal, and to be honest... this is the kind of thing that comes to mind.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

P5R: Rebel Girl (A FeMC Story/P5R Rework) Chapter 45: Old Wounds

Ren was a little anxious waiting on the confession. Yusuke had been keeping them updated about Madarame’s condition, and it seemed good, but Madarame was old. She was worried that all of this might have put too much strain on him, and he couldn’t handle it. Then again, if he had the power to abuse his students, maybe he could make it though.

Still, he felt best to alleviate some of her worries by going to talk to Dr. Maruki about her concerns, both in and out of the metaverse. She shot him a message first, in case anyone else had plans to see him.

Ren: Hey doc, are you available?

Dr. Maruki: The coast is clear.

Ren: OMW then.

She headed over. Once she got there, she knocked on the door. “Come in,” Maruki instructed. Ren walked in. “Have a seat.” Ren did so. “What’s on your mind?”

Ren put her head in her hands. “Well, right now I’m just a bit worried.”

“How come?” Maruki asked.

“Well, it’s just our latest target…” Ren responded.

“Ah yes, I heard about that,” Maruki said. “Madarame, huh. I would never have guessed.”

“Well, it’s becoming more and more apparent to me that not everything is as it seems,” Ren said.

“True” Maruki retorted. “So, what’s the issue then?

“Well, I’m just worried that because of Madarame’s advanced age, the combined stress of almost having his palace taken over and his treasure stolen, it might just be too much for him,” Ren explained.

“I see,” Maruki said. “While it is true that your emotional standing can take a toll on one’s physical health, I don’t think there’s too much to worry about.” Ren looked up. “Remember, the shadows are incomplete, and that includes the shadows of those who have palaces. So, them losing their palace and treasure is more akin to them running out of steam. So long as someone is taking care of him, he should be fine.”

“Hm,” Ren said. “He should be fine then.”

“Well, that sure seems quick,” Maruki said. “Is there anything else you’d like to talk about? How are you outside of being a Phantom Thief?”

Ren seemed a little puzzled. “Fine enough, I guess.”

“Well, you certainly are a strong one,” Maruki remarked.

“What’s that supposed to mean?” Ren asked, slightly indignant.

“Well, it’s just, not a lot of people would say they’re fine after getting falsely accused of assault,” Maruki noted.

Ren sort of pouted. “I guess that’s true.” There was a bit of silence. Ren sighed. “I’ve sort of noticed that Tokyo has changed me.”

“In what ways?” Maruki asked.

“Well, for starters, I have friends now, '' Ren said. She then realized what she had said. She panicked for a second, but decided to keep going. “Back home, I never really connected with anyone. Well, maybe when I was younger. But as things changed, no one really wanted to be friends with me.”

“I see,” Maruki observed. “Might I ask, how did you make your first friend in Tokyo?”

Ren looked at him. “Well, that, um…” She took a deep breath. “On my first day at school, I came across Ann at a crosswalk. Then Kamoshida pulled over and invited Ann in the car. He invited me as well, and we both agreed to it. I went solely to make sure Ann was alright.”

“Hm,” Maruki said, jotting things down. “So, you didn’t know her, but you wanted to keep her safe?”

Ren looked at him. “That’s right. And then when we got out, we just stuck together for the rest of the day. Well, except for when Ann had to use the bathroom. And just my luck, Kamoshida called me to his office then.”

“Oh my” Maruki said, surprised. “What happened then?”

“He tried to make a move on me,” Ren said. “But before anything could happen, Ann came in and took me out of there.”

“Hm. Well, that certainly was lucky, don’t you think?” Maruki asked.

“I guess so,” Ren said.

“Sorry, but that wasn’t entirely the answer I was expecting,” Maruki said. “She saved you because you were friends, correct?”

Ren was shocked. “I guess. But I don’t think Ann was just returning the favor. She felt really bad about not telling me about Kamoshida before that happened.”

“Hm. It seems like you have all the pieces, but you’re having trouble putting them into place” Maruki said.

Ren was confused. “I don’t suppose you have an answer then.”

“I may,” Maruki said. “But let’s see if you can’t find an answer first.” Ren thought for a moment. “If I may, let’s jog that thought process. What do you suppose would happen if you hadn’t met up with Ann but were still called to Kamoshida’s office?”

“I’m not sure,” Ren responded. “I’m not sure what would have happened between me and Kamoshida had Ann not interrupted.”

Maruki laughed. “Sorry, but you sort of touched on the answer.” Ren was perplexed. “You’re wondering what would have happened if Ann hadn’t shown up. But that’s not what I asked.” Ren was surprised. “All I asked was ‘What would happen if you hadn’t met Ann, but Kamoshida called out to you?’ Nowhere in that scenario does it state that Ann wouldn’t come.” Ren was shocked. “I think we’re sort of getting to the heart of the issue.”

“And that would be?” Ren inquired.

Maruki gave a serious look. “It’s hard for you to accept kindness at face value.” Ren was stunned. “This is just a hypothesis, but I’m guessing that due to that lack of connection you talked about in your hometown, you’re not used to receiving kindness from others. So when it does happen, you’re not 100% sure how to handle it.”

en thought about this for a moment. “I’ve been told...similar things...recently… You’re good.”

“I didn’t go to college for nothing,” Maruki said.

“What do you suggest I do?” Ren asked.

Maruki paused. “Well, like most things, this isn’t an overnight fix. But I think this is a case for Ockham's Razor. You have friends now. You should work on accepting their kindness when it is offered.”

Ren seemed a bit disappointed in herself. “I guess that makes sense.” She sighed deeply.

“I guess that’s a bit harder than I thought,” Maruki reacted.

“No, it’s just…” Ren said. “I get what you’re saying, and I think I’ve been getting better at that, but after spending so long putting up walls, it’s hard to know how to take them down without breaking.”

Maruki clearly saw Ren was troubled. The idea that people would be nice to her without reason is something that rarely crossed her mind, and in turn it made her keep people at arm’s length. In an instant, Maruki decided to do something a bit drastic.

“...as Rumi” he said, seemingly randomly. Ren looked up at him, confusion strewn about her face. “‘I’m not as good a cook as Rumi.’ That’s what I was saying at the clean up.”

Ren was curious about this sudden topic shift, but decided to roll with it. “And, who is Rumi?”

“My ex-girlfriend,” Maruki stated.

“Oh” Ren said, trying not to push it.

“Heh,” Maruki chuckled, catching Ren’s attention. “Our break-up was a little unusual.” Tears started to stream down his eyes. “You see, we were engaged to be wed. However, fate can be cruel sometimes. Her family home was robbed, and her parents were murdered. She went into a catatonic shock, and fell into a coma.

I visited her every day in the hospital. I was at a point where I’d give anything to see her smile again. Fate can be funny too. I had been researching cognitive psience a bit, and in the moment I wished for anything to get Rumi back, she woke up. However, she had no idea who I was.

I think whatever power I had was starting to manifest. After she had woken up, the doctors had examined her. Her memory was scuffed, but she was Rumi all the same. However, I decided that if I were to stay in Rumi’s life, it would only serve to hurt her. So, we split up.

After that, I grew even more involved in my research. I was more dedicated than ever to use cognitive psience for good. To make sure no one had to suffer like Rumi did. And when that was taken away from me, my palace appeared. But that didn’t last either.”

Ren was awestruck. Maruki had just said a lot, all the while his eyes were flowing like a river. “Why did you tell me all of that?”

“Well,” Maruki began, tears still erupting from his eyes, “I figured I needed to lead by example.” Ren was a tad puzzled. “You were worried about how to be more accepting of kindness and changing how you relate to people without breaking. The answer to that is break. Breaking is good. It shows that you’re responding to someone’s honest feelings with honesty of your own.”

“And that’s why you decided to spill your guts about what happened to you?” Ren asked.

Maruki nodded. He took his glasses off, dried his eyes, and put his glasses back on. “To be honest, I’ve never really gotten past what happened with Rumi. And I guess that led to the creation of my palace. But now, I have to face it head on if I wanna get anywhere else. And I suggest you do the same. You’re probably stronger than I am, which is why you seemed to hold out in your sense of justice this entire time. But if you wish to let Tokyo mold you into the best person you can be, then it’s important to show weakness when needed.”

Ren nodded. “Right.”

Councilor-Takato Maruki: Rank 2

She got up and bowed. “Thanks doctor.”

She was about to leave, but before she could, Dr. Maruki called out “Wait!” she stopped. “Before you go, would you care for a snack?” Ren smiled and picked something out of his bowl of treats.

As Ren was heading out, eating her snack, Morgana popped out “Um, don’t take this the wrong way, but it seems like you were already doing the stuff Dr. Maruki suggested. So why thank him?”

“Well, it’s complicated,” Ren said, between bites. “It’s like when you have a question in your mind, and it’s plaguing your every thought, but when you say it out loud the answer is crystal clear. I might have been growing, but now I have more of an awareness of it. Does that make sense?”

“I guess,” Morgana said, a little embarrassed. “It’s like when you picked up on my crush on Lady Ann when I told you I only have the mission to think about.”

“There you go,” Ren said. She continued eating and heading out.

Later that night, she arrived at Untouchable. “Hey,” Iwai said.

“How’s business?” Ren asked.

“Business is going fine,” Iwai said. “But I’m also working on something.”

“I hope it’s more customizable parts,” Ren said.

Iwai grinned. “Ha. But no. I’m looking into the information we acquired from the diner the other day.”

“Oh” Ren said, deadpan.

Iwai looked forlorn. He sighed. “I guess I gotta tell ya. Otherwise things won’t make sense. At least, if things play out as expected. That guy, Masa, and the guy he was talking to, Tsuda. Back in the day, the three of us were mafia brethren.” Ren was a little stunned. “Back then, I was just a dumb kid lookin’ for a place to belong. And I found it. At least for a while.”

“What happened that you gave it up?” Ren asked.

“Well…” Iwai began.

The door then opened up. They looked over to see a boy a bit younger than Ren. “Hey” he said.

Iwai was a bit shocked. “What’d I tell you about coming here unannounced?”

The boy was stunned. “...Sorry.”

Iwai sighed. “No. I’m the one who’s sorry. I didn’t mean to snap at you like that.”

The boy looked at Ren. “Who’s she?”

“She’s just some hired help,” Iwai explained.

The boy was surprised. “You hired someone?”

“Yeah, well…” Iwai lamented.

“That’s great!” the boy said. Iwai was surprised. “You've been stressed out lately, so it’ll help to have someone lighten the load.”

wai was still shocked. “Heh. Careful now. With thinking like that, if you start a business of your own, you might run me out.”

The boy’s face was now flush. “Aw stop. You’re embarrassing me.” He turned to Ren. “I’m Kaoru. Kaoru Iwai.”

Ren was a little surprised. “My son,” Iwai said, hoping to clarify, but only serving to confuse Ren some more. “He’s a third year in middle school.”

Kaoru nodded. “And what’s your name?”

Ren was still trying to process everything. Still, she composed herself and introduced herself. “Ren. Ren Amamiya. Second-year high schooler, and part time worker at your father’s store.”

“Wow,” Kaoru said. He bowed. “Nice to meet you.”

“Likewise” Ren said.

“So, what are you doing here anyways?” Iwai asked.

“Oh, right,” Kaoru said. “I’m wondering if you’ll be home for dinner tonight. I headed out shopping and was wondering if I needed to get enough food for the both of us, or just me.” Ren took note of that particular line.

Iwai checked his phone. “You say you just left to go shopping?” Kaoru nodded. “Alright. Get enough for both of us. I’ve gotta finish a few things around the shop, and then I’ll join you, and we can go home together.”

“Oh. OK” Kaoru said. He started to leave. “It was nice meeting you, Ren. Ah. I should be calling you ‘Ren-snepai’.” Ren blushed just a little. “See you later!” He left.

Iwai looked a mixture of relieved, disappointed, and amused. “So, what happened to Kaoru’s mom?” Ren asked.

Iwai was now more surprised than that strange trio of emotions he felt a second ago. He sighed. “Well, for starters, Kaoru isn’t my biological child” he began explaining. Ren felt confused, concerned, and weirdly, relieved. “Do you want the lie or the truth?”

“Both, if possible” Ren said, defaulting on her natural playfulness.

“Hm. Figures” Iwai said. “I told Kaoru, and pretty much everyone who doesn’t know me, that Kaoru’s parents died in a car crash, and I took him in. I figured something must have happened to him. When I first came across him, I noticed he had this scar shaped like a gecko.”

“You mean, like yours?” Ren asked.

“Well, that came after,” Iwai said. “I got it to show solidarity with Kaoru. It’s like a family crest.”

“Softie” Ren teased.

Iwai smiled, unable to deny that. He grew serious again. “What really happened was that Kaoru’s birth mom came to some of us in the Yakuza asking to sell Kaoru for drug money. When we said no, she just left him there. I decided to take care of him then. And that meant going on the straight and narrow.”

Ren was surprised. “Damn and I thought you were a softie with the lie.”

“Heh” Iwai grunted. “I just figured that this kid needed a fighting chance.”

Ren rolled her eyes. “So, Kaoru doesn’t know you are ex-yakuza?” Iwai shook his head. “Why not tell him?”

“Because…” Iwai said. “I don’t want him being dragged down by me. I know my parents never gave enough of a shit about me, so I’m trying to give enough of a shit about him. If he finds out I was a mafia guy, he’ll know I’m a failure, and all of that will go down the drain.”

“I still think you should consider it,” Ren said. “If you’re so worried about him finding out via him walking in, it might be better to explain it on your own terms.”

Iwai thought about it. “Maybe. But he’s got a lot to focus on right now. I don’t wanna drag him down when he needs to focus on things like high school entrance exams.”

“I guess that’s fair” Ren said. “But maybe you should tell him before things get out of hand.”

Iwai sighed. “You’re probably right, but I have my own hang ups.”

“That’s fine,” Ren said. “I’m not hang up free either, so I get it.”

Iwai smiled. “And you call me a softie.”

“What can I say? Birds of a feather…” Ren noted. Iwai got a good chuckle out of that.

Hanged Man-Munehisa Iwai: Rank 3.

“Anyways, you should get going,” Iwai said. “In case you forgot, I've gotta get home for dinner.”

“Right” Ren nodded. She gleefully left the store and went back to Leblanc.

#persona 5#persona fanfiction#persona 5 royal#p5r#p5 femc#p5 rework#p5r rework#p5#FeMC#female ren#ren amamiya#dr maruki#morgana#iwai munehisa#iwai kaoru

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

(1/2)🐛? (on mobile cant find your faq sorry) My mom raped me for years and i recently escaped now that im 18. I didnt remember the sexual abuse when i made the decision to leave but i randomly realized it a few months later. I have found little support and therapy for an hour a week is all i can afford but is not enough. I am at the end of my rope with my trauma and DID and i dont know what to do. The biggest issue is the overwhelming shame, and feeling like i deserved it.

(2/2)🐛 I keep falling into saying it didn't happen/wasn't that bad/others had it worse to the point I get sick when I deny it too much. An alter keeps saying the rest of us are lying and mom is a good person and we should go back. I feel like I made everything up because I read a lot of noncon fic to try to punish myself. Every grounding technique I have tried has failed. Sorry, I know this is a lot. Any resources for female survivors of maternal incest? Or any advice at all? I feel so alone.

Hello,

I’ll separate this into parts to hopefully help with converting clear information.

Denial, believing it’s fake.

Fake memories, or just “made up” memories do not happen commonly, [information here The False Memory Myth & Memory Repression]. there is nothing wrong with feeling that way however, self-denial and downplaying of our one trauma is really common.

Having “denial of parts/alters” is really common. I personally have DID as well and we have alters who deny our abuse, blame our abuse or have a deep attachment to our abusers. That is so normal! You are not alone, In this struggle. If you have any internal communication you can talk to the other alters who share this trauma for support these internal connection are god for recovery.

If you have the stability or any parts wh are good at working with there might also am them why they feel the need to defend the mother. communicating can also help ease your feeling of overwhelming and denial.

One key way to help with downplaying of abuse is to imagine a friend came to you and told you what happened to you happened to them. And think about what you would tell them, I bet it’s not. “it wasn’t bad” or “well other people got it worse”.

When you have worked out the kind of compassionate language, start picture the little girl inside you who went through the trauma. This can include talking to some of your young alters if you have any communication methods with them. Sometimes pulling them forward through focusing on your internal child might happen and sometimes those with DID can access the internal child through more basic IFS (internal family system) and Part Work methods. And offer them compassion for what they are going through.

Shame

When you find thoughts of shame start to spiral, not the thoughts and the feelings in your body. But then take a long breath and work to not identify with that thought. The emotion and thoughts exist but you don’t have t push yourself to think about it r feel it. Picture the emotion and try and let it pass.

Working towards self neutrality is also a good goal. Refraimging the language you use to talk about yourself, and in your case, your alters, to something that lacks overly negative connotation ill help change the schemas of shame. Coping Skills: Ditch Value judgments

Those words of compassion we talked about early when you find yourself starting to feel so down on yourself and shameful try saying these words to yourself. Along with some positive self aspirational mantras, you can help start to reshape the patterns your neurology follows. You won’t believe them at first but saying these will help with healing.

Practising good self-care can be super important. When we can treat our body with honesty and respect that helps shape our internal sense of being respected and being care for. It’s also just good for general depression and health. [Coping Skills Masterposts: Self-Care]

I know how hard things like showers can be but starting with just tooth brushing and face washing can be important. If brushing of teeth is a trigger I suggest buying a smaller toothbrush like a kids size and changing toothpaste to one tat either foams less, is another colour or if the taste carries. Using baby whips or a wet cloth to areas like the groin, armpits, under breasts and behind knees would be another important step towards overall health.

Keeping the living space as neat as possible also counteracts feelings of overwhelming shame and self-esteem issues.

The use of sexual material to cope

When we struggling to deal our tendency to self-harm is very common as it’s a maladaptive attempt to cope. Using the stories as a way to in your words punish is a form of self-injurious behaviour. Factors like lack of regulation, compulsive behaviour, intrusive thoughts and being manipulated by users to believing this is a reaction to perceived threats. [Coping Skills: Combating Self-Harm Urges]

This doesn’t invalidate abuse as having been abused is not contingent in never interacting with sexual content, up to and including having sex, afterwards. CSA often predates other unhealthy sexual behaviours as a reaction to our sexual traumas. No way our trauma reactions show mean our abuse didn’t happen or didn’t hurt us deeply.

Coping Skills

It makes sense a lot of the mainstream grounding is hard and lack effectiveness. Much of the meditative type skills intensify dissociation. We also often struggle with our automatic nervous systems being even more fractured than those with PTSD. Our neurological behaviour will also be more likely to take any stress or confusion and push us to dissociate. Visualization also tends to work poorly for many of us with dissociative disorders for the same issue of a tendency to dissociate. Focusing on a singular self to ground into can also become hard for us too and trigger depersonalization.

If there are skills you liked in theory and didn’t have direct negative effects it might be worth trying them again. I do understand the frustration I really really do but it can be worth it. especially as you learn what coping skills can work with different somatic sensations and cognitive distortions.

I would suggest using some of the most basic coping methods of deep breathing. I would guess this already takes a lot of brainpower as even basic things like breathing regularly can be hard for those who have extreme dissociation. So it takes a huge amount of practice for us and time for it to be effective but it’s so very important.

I would suggest still trying to practice focusing on our body sensations even if we don’t add the subsequent suggestions for grounding. Knowing what sensations tend to present themselves when certain stimuli and thoughts are present is really important for coping. It can be true that the coping skill you are working at isn’t addressing where you are. For examples, our nervous system can be in hyperarousal but many grounding skills counteract hyperarousal. So try and look for engagement over relaxation or visa versus.

I am a big believer in the body-mind connection and import of the brain-body connection and coping that is body focused. Cogntive skills like thought stopping and replacing can be truly helpful in the short term for trauma survivors.

Talk to your alters as well, coping can be influenced by the emotions land somatic states trauma we are carrying along with the ones within our consciousness. They might also just have opinions on what you ought to do. This can be done internally or through other means like writing notes.

Mother-daughter incest

I have found very little survivor orientated material that could be helpful, I found mostly news sources about how it exists and academic texts.

If any of our community knows of survivor focused materials for survivors of mother-daughter incest please reply or submit them.

We do have a discord that you could join and we have an incest support channel we are still growing the members of the server but it might be a place to have peer support.

Be Blessed,

-Admin 2

#ask#advice#coping skills#dissociative identity disorder#did#dissociation#incest cw#mother mention#rape cw#noncon mention#Anonymous

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Edit: it won't let me put this in normal title format, so:

Almost Peaceful

-_-_-_-_-_-_-_

Four thousand planets in the Great Unity. Six thousand sentient species, give or take. Technology so complicated it could only be repaired by crews with multiple different cognition types on the team. And that's not even mentioning the violent flare-ups that had brought the Great Unity down from eight thousand planets and fourteen thousand species. It was entirely understandable for the humans to be intimidated. But no, that wasn't quite it.

To the species with similar intelligences and social structures, it almost seemed that the humans were embarrassed, of all things. But nobody paid them any mind. Their insistence on using the freely given technologies to outphase the signals that they had been broadcasting for cycles? Odd. Same with their social quarantining of all human history, and with the electromagnetic shielding of their quadrant. The only thing people really paid attention to was when this backwater nothing asked for the other species to delete the preliminary data gathered earlier. Some worlds balked at that, but this tiny, flimsy race was so obviously terrified that even the most predatory of the war races consented to the purge. It didn't really matter anyways - their quadrant, an even mix of death worlds and featureless rocks, was otherwise entirely empty of life, sentient or otherwise.

The Alab were the first to realize how strange that had been. If humanity had then hidden itself away, kept from the rest of the universe, it would have been as expected (there were many shy, prey-evolved races), and they would have been ignored, as seemed their wish. But no. The flimsy bipeds built ships of their own, founded settlements on half a dozen worlds. And these places weren't shielded like Earthspace was; instead they were as obvious and unshielded as possible. Curious about the oddity - they were a plains evolution, so curiosity fit them - the Alab ventured as close as they could to the strange cities without being spotted, hidden beneath the best cloaking the Great Unity had to offer.

As it turned out, they didn't need to hide. Partially because the Humans saw them, somehow, and partially because the Humans invited them down. By now the Alab's interest had attracted the attention of most of the Great Unity, who telepathically watched through the Alab sensory hearts as a world opened up around them.

This colony was not the tarnished scar they would have expected of a nascent race. Even the planet was different from the dusty rock it had started as.

A cool breeze touched the Alab delegation. It was scented with so many things that, for a moment, the Alab was frozen in simply trying to process the variety. The variety, of course, came from the masterpiece of terraforming before them: where there were one craters, glittering pools shimmered with the reflective scales of aquatic creatures; the star-burnt ridges now housed both massive, rigid photosynthetic organisms and prancing furred quadrupeds.

Even that brief glimpse sparked massive speculation on the universal scale. Were the humans genetic engineers whose art surpassed even that of the Tra'di? Did their planet simply have that many organisms, with an evolutionary history far enough beyond anything seen elsewhere, to create such variety of perfectly proportioned life? Landscape designers hurriedly took notes and scans, preparing for the unavoidable rush of requests for the new style.

But that wasn't the mission, as stunning as the landscape was. The Alab turned around, clicking their hearts at the abrupt change in input. The city was massive, a gleaming wonder in stone and steel, somehow surpassing the crystal forests of the Mavse in elegance. The ships soaring through the skies above shone like the stars they sought, yet the Alab could pick out individual details on the designs adorning them.

Not long after this event, other species began to visit Humanity's homes. Without fail, each and every one of them was uniquely beautiful. Their ships weren't the fastest, but one couldn't help but be impressed at their symmetry. Their music wasn't the most complex, but it often gave rise to more emotion than actual empathic abilities. And each colony had its own biome, its own set of unique species, each more impressive than the last.

Rumors began to grow, as they do, surrounding the home world of the greatest artists the universe had ever seen. Some said that it was drab, focused on training the artists they sent out rather than on making the art itself. Others declared that Earth obviously was a religious secret (they had found out that humans had religion only a few cycles earlier. Of course, their prayers and monuments were the most beautiful anyone had ever seen), but that was scoffed at. The sheer breadth of human religions wouldn't allow a decision that unified, the debaters pointed out, and at least one human would have given it away before now if it was something centered on faith.

By far the most popular opinion was that even the most wondrous works on the colony worlds paled in comparison to the splendor of Earth. Tales spread, saying that anyone nonhuman who saw Earth in all its glory would be struck silent by awe, never to speak again, for fear of diminishing the memory of what they saw. That Earth was so wondrous that the colonists saw their own worlds, home to more abstract riches and honor than most of the rest of the universe, as hopelessly utilitarian, as gray and lifeless in comparison as Raner Alikrem to Ormek 8.

Over the Human cycles, Earth grew in fame and mystery. Despite taking advantage of every advancement shown to them, Humanity never once volunteered knowledge or technology beyond that of their art and culture. Nobody minded, though, as said art was definitely worth the cost. Humans got more and more famous, and continually better educated, as the Great Unity slowly funded and rewarded their astounding work. But they retained their peculiar aversions, never accepting any weapons, or training, or even remotely militant designs, acting almost horrified at the thought of violence. It made sense, in an odd way. The fragmentary human history that had been gathered from the occasional interview with the taciturn race was as pure as it came, one where even hinting at conflict would see one shunned. Traders and scholars learned this quickly, taking specialized training in avoiding the subject just to avoid scaring their precious artists.

It was with this in mind that the Gald set out for Earth. They were one of the oldest species in the galaxy, and undoubtedly one of those for whom the times of peace chafed the most. It was in seeking both truth and conquest that they sent out their expeditionary force towards Earth. The logic was plain even to the most sedentary of species - if the most fascinating mystery in all the universe was being guarded by the eleventh most physically weak of the races, and the second least violent (the least being an immobile, telepathic cellscape that covered a small moon), then of course a predator-evolved race with an undeniable urge to spread their reach, grow their power, would eventually come after them.

The first fleet was more of a team of armed ambassadors than an armada. Even as they attacked, the Gald hoped to stay in Humanity's good graces. The Gald kept in careful contact with them up until the moment they crossed over into the shielded Earthspace.

The first fleet was never heard from again. The Gald, logically assuming that some standard space disaster had befallen their fleet, sent another, this one with precautionary reconnaissance and messenger ships. Again, all was well up to the shielded space. The Gald, sure that the new fleet was safe from all but the strangest disasters, waited with bated breath for the return of the messenger ships.

The first one came back early, not only with a report from the fleet (no notable planets had been found yet, other than twelve deathworlds. The fleet continued its search for Earth), but with cargo. That was unexpected, to say the least. The messenger ships had been intended to fly back and forth across the shield, transmitting messages from one side to the other. That one had been used instead to transfer what looked like an derelict satellite meant that, whatever was on that satellite, it was worth looking in to.

The satellite proved a welcome distraction from waiting for the return of the second fleet. It had turned out to be an old mining surveyor, sent into what would become Earthspace mere ertd before the humans entered the Great Unity. It had been destroyed - they couldn't tell by what - only twelve Human cycles before said entrance.

Excitedly, the Gald searched the recorded scans from the surveyor for images of Earth. It only took them a few hundred false positives - deathworlds and wastelands all - before they found it. A world, extremely high in water content, of substandard gravity. Cloaked, seemingly unintentionally, in a cacophony of electromagnetic signals, the world had all the readouts of a near-spacefaring race. The Gald, elated at their discovery of Earth's exact location (what kind of planet hides themselves in the exact center of the protective shielding?), sent the messenger ship back across, with new commands for the fleet.

There was no response. The second fleet had, somehow, vanished.

Frustrated now, the Gald sent a proper fleet for the third time, targeting the exact location of their quarry. Armed with the most formidable equipment the Great Unity (home to almost a thousand intelligent warlike species) had to offer, and with a borderline-forbidden Breacher signal processing unit that would allow them to transmit past the shielding back to their home planet, they closed in.

Everything was going well - the invasion force was actually feeling a bit pointless - when they reached the first field of wreckages. They stopped for just long enough to check that there were no survivors of their fleet, and that there were no intact ships or weapon systems to harvest. It was when they reached the second fleet that they realized something might actually be wrong - these ships were perfectly bisected along the power cores, the corpses of their crew shot midfloat even as they died in the depressurization of space. But again, scans revealed no useful resources, personnel, or information about the opposing force.

By then the crews had begun to mutter. Nobody had any idea of what could have done all of this - the technology was far beyond that of the rest of the Great Unity. Some said that it was a rogue member of the Great Unity who had gotten there first. Others said that it was even a species from outside the known, who was trying to infiltrate the Great Unity through their physically weakest link. Either way, the mission of the Gald shifted in a new direction: save the humans from this strange new threat. The fact that doing so would net them the secrets of Earth was simply a bonus to a glorious war.

The high command glinted at that - it was a political win/win from something that they had expected to bring them only hatred. As the Gald, weapons primed against the unknown threat, passed into the solar system that Earth was supposed to be located in, they began to broadcast their oncoming victory across the universe. Every member of the Great Unity guiltily watched, greedy for the final answer to the Question of Earth.

The Gald passed the star that Earth circled. They counted planets our from the center, pausing when they got to the third nearest. It wasn't Earth. Or at least, it didn't look like it. There were no towering cities of light, nor were there full monasteries of inspiration. There were no massive tracts of wildlife, no "forests", no poles of ice, no massive mountains. Even the water, which had before been one of the natural wonders of this world according to the mining satellite, had vanished, leaving the continents indistinguishable from the sea floor.

Horror and sadness filled the galaxy - clearly whatever had destroyed the Gald fleets had also smote the Earth into oblivion, leaving slag where there were once mountains, and radioactive craters where the satellite showed had once been glorious cities.

It was while the Gald drifted in shock that the armada appeared, dropping cloaks unlike anything the Great Unity had ever seen before unleashing whirlwinds of light and kinetics upon the unfortunate war fleet.

The signal cut off. Silently - so as not to alarm the human colonies, who had, of course, not watched - the myriad worlds of the Great Unity came to a consensus. They would keep this horrendous act of violence from the Humans for as long as possible. They would arm themselves, surrounding Earthspace with the best and brightest of every militant force the Great Unity had to offer. And they would study every recorded trace of the Gald transmission until they knew everything possible about those monstrous destroyers who came to be called the Worldbreakers.

Several erdt passed, with no trace of the Worldbreakers. Another fleet, armed again with a Breacher, was sent into Earthspace. They didn't last long.

A pattern developed, over time. A fleet would go in, armed with the newest equipment, often technology inspired by their very foes. They would briefly be able to scan Earth and the neighboring systems, often places with even more melted planets, before being extinguished by the Worldbreakers. It happened again and again. The newest of weapons would be blocked with shields specifically designed against their unique energy signatures. The most outlandish of strategies was outdone as if textbook. Nothing could phase the Worldbreakers; it became clear that they had played at war at extremes beyond the imaginations of even the sadistic Denwim.

The Worldbreakers became a common component of human-free discussions. Cults formed around them, both worshipping their undefeated might and fearing the eventuality that they would notice the rest of the intelligent universe. And then the day came. The day that turned everything around. It was a combination of three simultaneous events, between an obsessive astronomical historian, a lab treating a Human child for brain damage, and a student's analysis of the Gald transmissions.

The historian was comparing old electromagnetic transmission records to the current species database, to track how many near-spaceflight species actually developed it and entered the Great Unity. It was quite surprised when it found a plethora of electromagnetic records, all obviously from different species, from all across what became Earthspace. It wondered to its colleagues what could have happened to seventy-three distinct species that would leave no trace of their civilization. No disaster they could imagine would have allowed the survival of only the Humans, a race too fragile to survive much of their own planet, much less interstellar catastrophes.

The doctor who headed up the lab was doing routine lobe simulations, checking that each repaired part of the Human child's brain worked as properly. He was quite interested in this, as Humans generally performed their own operations, and the Human brain was largely a mystery to most of the universe. He was hoping for some distinctive part that would explain Humanity's artistic skills, so his simulations were very in depth.

One can imagine his surprise when, instead of symmetry and resonance being the core of the Human biopsychological makeup, his simulation showed little other than pure, unadulterated aggression and greed. Uncertain, he ran it again. And again. Then he called the other interspecies doctors he knew to have them replicate the results. It was confirmed - Humans, the race so famous for hating the mere thought of conflict, was at its core the most hateful species the Great Unity possessed, orders of magnitude worse than the Gald.

And the student's work sealed the matter. In a thermometric readout of the planets destroyed by the Worldbreakers, she found that, according to standard interplanetary cooling formulas, the Earth had to have been destroyed long ago, before even the Humans reached out to the Great Unity to ask for privacy. Unity laws prevented locations with signs of unknown species from being placed under electromagnetic shielding and social quarantine, so the Worldbreakers couldn't have been there to destroy Earth before the shield was placed. The paradox did not lend itself at all to any known theories.

The logic was clear. Even the hive minds agreed. Humanity was not the docile race of scholars and artists that they appeared. Nor were they shy about their homeworld. Not shy, but paranoid. Sensibly paranoid that, should the Great Unity discover their war-torn past, that they had not only destroyed at least seventy-three sentient species but also their own planet in the short time between when they had developed space flight and joined the Great Unity, the other members would have either fled or tried and failed to exterminate them. So they went with their other option - beauty. They hid their ugliness under a veil of wonder, only sending their unstoppable armada after those who came close to finding out their secret past.

The understanding rocked the galaxy. Nobody sane had even contemplated this before, that one species could appear so innocent and yet be so terrifying. Their worlds would never be the same.

Despite all of this, little to nothing changed for the Humans. Aliens still came from all over to view their work, even if they now did it with apprehension. Scholars still appreciated their mystery, perhaps all the more.

And, of course, the unofficial rule that the topic of violence was never, ever to be breached while Humans were in contact suddenly became a lot more official.

Tl;dr: Humans are the super shy aliens. Too bad. It's always the quiet ones.

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

trigger warning: this is a meditation on the after-effects of sexual assault and relationship violence, featuring explicit discussion of suicidality and self harm. I know I write on these themes a lot, but I feel like this is more raw than usual and something that could potentially hurt a few of you - even if we are close friends, please don’t feel pressured to read it.

reassuring comment added now that I’ve written everything: I’m posting this as an exercise in vulnerability and a cry for comfort. that said, I am safe and feel like I should reassure everyone of that. I am safe and now that this is over I will crochet, eat some soup, and go to two yoga classes. maybe play some piano. writing like this externalizes the heaviness and makes me see it from an outsider’s perspective, which helps me pull out a lot of self-compassion. though I feel this way on some level, I also feel an urgent need to care for myself on other levels, and reach out when in crisis - in short, I am safe but have a lot to process. and processing it publicly like this helps with the shame I feel and will likely help me bring this up in my next therapy phonecall.

I finally have a day off and haven’t written about my mind in a really long while. but, before I write (which may take an hour and my god is it an hour that I need) I will put some salmon on my plate and brew a cup of black cherry tea. let me get back to you.

I’m letting hayley kiyoko’s girls like girls finish playing before I put on my spotify daily mix number 4 (hozier, bon iver, handmouth and more, apparently). there’s a cut grapefruit and salmon and tea near me, and my coffee cup that’s almost finished but has gone a bit cold by now. I don’t know why it is that writing through tumblr makes me express myself most truthfully, more truthfully than if I opened evernote or textedit or wrote on paper or if I spoke to someone directly via voice or text. the liminal space of having no audience while having a vast audience is comforting, I guess. a different kind of false vulnerability coupled with a kind of anonymity.

now that I’ve put on daily mix 4, let me start by saying what I thought to say when I got up to make tea: I am permeated by sadness.

it is exhausting to be permeated by sadness. I feel it at the base of my sternum, stirring gently, right at home in my very core. agitated when something goes wrong, and peacefully present otherwise. this is all a cliche, I know. I know. but lately my sadness feels like its own separate entity, living comfortably in me, and almost harmoniously. it keeps quiet sometimes, which I am grateful for, but still nuzzles into me just to remind me - I’m here and will always be here and that’s ok.

and that’s ok.

I’m trying to make peace with who I am. I know that self-identity shapes perception. I know that thinking of myself as a cook makes me cook more, that thinking of myself as a yogi makes me take advantage of my unlimited classes more, that thinking of myself as mentally ill probably exacerbates symptoms (just think positive!).

I’m trying to make peace with my limitations. my need for regularity in sleep and diet, my rapid exhaustion, my failing memory. my tendency to shut down completely. my readiness to cry when something hits me hard.

when something hits me hard.

I just paused in writing this to read a reference letter that my old volunteer coordinator wrote for a big national scholarship (she emailed it to me as I was writing this). and I cried. I cried at the cognitive dissonance of my brain repeatedly telling me how worthless I am and this person tangibly proving the wonderful things they have to say about me. it’s funny because I really believe that those two people exist at once.

“I love me but I don’t love me back” to paraphrase a post I recently reblogged.

how can I exist as selfish, unloveable, and needing to be hurt punished destroyed when I also exist as compassionate, kindhearted, intelligent, successful, and supportive?

and yet my brain is convinced, convinced, that this is how this works. when I’m tired, I have less energy to devote to silencing the ever-pressing thought of “you don’t deserve to be alive”. I am not suicidal, per se, because I want to be alive. things are really looking up lately, and really working out, and I am involved in exciting initiatives and have mutually cared about wonderful and interesting people and am growing all the time... but I do not feel like I deserve it.

how do I fight for the things I should be fighting for (like scholarships, authorship, opportunities, attention?) when I feel like I don’t deserve to relax, to eat, to laugh.

my homework for therapy for these two weeks was to think about shame. let me say this: I am ashamed to tell anyone how I feel. I am ashamed of these complex feelings of no self worth, I am ashamed of my urge to self destruct, I am ashamed of my shame. I am ashamed to say the truth about how I feel, about what I experience, about how I react.

two weeks ago, at the doctor’s, I cried uncontrollably. and I mean that literally. I cry a lot, maybe once a week, and it’s often dramatic and torrential (and necessary). but these tears were... different somehow. I don’t remember a lot from the winter of 2014, when I spent more of my time awake in flashbacks to the past than in the present, but I suspect that these recent tears were similar to those days.

“that’s not supposed to hurt” the doctor said very kindly very gently and I am on my back crying crying crying unable to see and I barely hear her and I am afraid and ashamed and crying.

“I’m sorry, I have a history” was all I could choke up and she wouldn’t let it go. I know why, I know it’s her training, she needs to make sure it’s ok and not believe me when I say “it’s nothing, it’s fine, I’m ok” she’s supposed to push, to ask, to make me tell her. and I cry, I cry and I make it off the exam table to the chair where she writes my prescription and I cry I cry I cry. I step out of the office, to the lab to drop off the swab for testing (the poor lab tech does not acknowledge I am crying but is clearly uncomfortable), to the bathroom to cry more. fifteen minutes later I am unable to stop and I am hungry and want to go home so I walk through campus, first inside then outside, crying quietly, effortlessly. my face barely moves and tears just go and go and go and it’s raining outside and I keep crying.

I walk home slowly and pick up my prescription close to the house, so nearly an hour has past since I started crying. I am more in control now, thankfully. the pharmacist says, in a whisper as she hands me the prescription “just try not to have relations with anyone” and something breaks more. tears and shame.

this is all a fucking cliche.

I tell my therapist about it a week later, when I call him by the river, but I change the subject right after. we revisit it three times during the hour, always briefly, three sentences. how do I talk about it?

I know that there is so much I don’t remember. I know. the fall of 2013 is a blur of pain and I have recurring visions that I don’t know if they were true. when I am upset and think that I deserve to be hurt, I see myself getting pushed into a wall, right shoulder and bicep first, hip and head next. always the same image. but I don’t think that happened, because I would remember it.

(but what about the gap in my memory after he takes my phone from me?)

I estimate: how many times? first maybe two times a week, by the end every day. does every day count? when did it start being every day? it couldn’t have been every day.

I know when the last times were with certainty. I know the dates and even the times of day. the circumstances. those are clear.

the cliche of talking about this (I don’t call it by the word almost ever I don’t call it by any word sometimes and today is one of those days) almost four years after it happened. over two weeks after my amygdala relived it anew.

I think that’s the real trouble with these things. they feel like they keep happening. first, it wasn’t once. it was at least two times, but probably not more than a few dozen worth. probably. do the math.

(god you’re pathetic, how could you ever let that happen a few dozen times? no one would do that, you must be making it up so that you can have an excuse to feel sorry for yourself)

and since it happened a lot (or didn’t happen at all, I made it up), the memories all muddled together, the fearshame returning all the time... it’s a cliche, I know, I know it’s a cliche, but it feels so recent. it feels like I can’t tell the difference between the act and the memory. the replica is the real thing, the same fearshame (I like putting those words together because that is the thing that feeds my sadness and it is one and the same).

cliche, really.

how do I cure this? how do I stop being stuck and having this on replay again and again and again.

I feel like I’m dishonest with people who don’t know. if someone doesn’t know about this, well, they have the wrong idea about me. they don’t see the rot.

(the feeling of being fundamentally rotten and flawed, shame around who you are, the feeling of being destined to hurt anyone in the end, the feeling of being broken, the feeling of being fundamentally evil, the feeling of imposter syndrome on a greater scale, the feeling of inadequacy, the feeling of deserving this pain and so much more pain, the feeling of deserving getting slammed into a wall right shoulder first)

but I am ashamed. ashamed of the trauma rot pain.

(hasthag bell let’s talk day and pretend that mental health exists in isolation of abuse and flawed power dynamics and people getting profoundly hurt by other people and that if we all just talked more it would go away but talking remains frightening when it’s not self contained in the conventional narrative)

how to combat the sense of “no, you don’t understand, I’m not legitimately ill. I deserve to feel this way. I am doomed to sadness.”

I hate the just world hypothesis, that bad things happen to bad people and good things happen to good people. but I believe it.

and if bad things happened to me, it is because I am bad, and therefore I don’t deserve to be alive. but I am ashamed of that thought because if I say it out loud people will know how bad I am, how rotten, how destroyed, how obsessed with self pity. they will know and they will agree.

how can I be the worst human on earth and trick others into thinking that I am kind, loving, smart, supportive?

it is comical when the mental illness tricks you and you find yourself thinking “well, I couldn’t possibly be worse than hitler” and it says “oh no, trust me, you’re way worse than hitler”. I chuckle but the sadness stirs at the base of my sternum, awake and nuzzling into me.

how do you heal when you remain convinced that you deserve to have your bones broken instead?

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

RHR: How to Use Tech to Improve Your Sleep, with Harpreet Rai

In this episode, we discuss:

What the Oura Ring can do

The importance of sleep

Why your brain needs downtime

Using technology to improve your health

How to measure your stress levels

How your sleep reflects the way you spent your day

What’s next for the Oura Ring

How you can get $50 off your Oura Ring purchase

Show notes:

Oura Ring

“Sleep Quality and Adolescent Default Mode Network Connectivity.”

Learning How to Learn from Coursera

The Moment app

The Center for Humane Technology from Tristan Harris

youtube

[smart_track_player url="https://ift.tt/2EHFkKZ" title="How to Use Tech to Improve Your Sleep, with Harpreet Rai" artist="Chris Kresser" ]

Hey, everybody, Chris Kresser here. Welcome to another episode of Revolution Health Radio. This week I’m excited to welcome Harpreet Rai as my guest. He is the CEO of Oura Ring.

The Oura Ring is, I think, the most effective device on the market today for tracking things like heart rate variability, sleep, and physical activity. I have one myself and we use it extensively with our patients in the clinic. So I wanted to talk with Harpreet about heart rate variability, what it can tell us, how we can use it to improve our health, the sleep tracking technology in the Oura Ring and why that’s important, and just what the general value is of increasing our awareness about the various behaviors and interventions that we do on a daily basis and how they impact our sleep and our stress as measured by heart rate variability and our overall health. All right, let’s dive in.

Chris Kresser: Harpreet, such a pleasure to finally have you on the show. I’ve been looking forward to this for a long time.

Harpreet Rai: Likewise, Chris. Yeah, it was awesome to connect early in the year at Paleo f(x), and glad we finally got to reconnect now.

Chris Kresser: Cool, so I'm looking at my Oura Ring right now on my finger. It's funny, I've been in the clinic, I've had at least five or six patients say, “Oh, you’ve got your ring. How did you get yours already in the new version?” And I’ve sensed some Oura Ring envy among my people. But I know that the new version is shipping out now. Because I preordered one, so now I have two. So if anyone needs a size 10 … Oh, actually I’m just noticing that my other one is a different color.

Harpreet Rai: Okay, nice.

Chris Kresser: So maybe I can fashionably go back and forth between two different rings here. So yeah, the reason I wanted to have you on is not to create more ring envy, but to talk about the really cool technology behind this ring. And just even step back further and discuss why someone like me would wear a ring like this.

Harpreet Rai: Sure.

Chris Kresser: What it can do for us and why you’ve made some of, at Oura, made some of the decisions that you made. Because the tracking industry is pretty big now. There's so many different devices and things you can choose from, Apple watch, Fitbit, Garmin, etc. And in a way you could look at it like, “Why did we need another one?”

Harpreet Rai: Right.

What the Oura Ring Can Do

Chris Kresser: But I think there are some really clear and interesting answers to that question. You at Oura have chosen to focus on sleep, which is interesting in itself, because so many others focus on things like steps and activity. And even some on, like Apple watch is really kind of promoting health protection. Like you fall down, or if you're having a heart attack or something like that, which is great. But why sleep?

Harpreet Rai: Yeah. Look, thanks for the question, and maybe just to make sure we don’t create more anger, potential Oura envy here, just to let everyone know we put this on our blog as well. We've now shipped over 10,000 gen two Oura Rings. We’re shipping, we’ve sent thousands per week. So people, they are coming soon. Frankly, we got more demand than we expected, and we’re a small company, and we’re trying to grow as fast as we can, but we do apologize, and our team is working around the clock, literally, to get them out as fast as we can.

Chris Kresser: Let me just give full disclosure. I was provided an Oura Ring to evaluate and I also bought one. So you can take my recommendations with that in mind. I paid money for one, and I’m very happy that I did. And I was also generously provided one for evaluation by Harpreet. So always important for me to get that out there.

The Importance of Sleep

Harpreet Rai: Appreciate that. But yeah, look, I think you’re right, the wearable market, they’ve been around for quite some time now. I think Fitbit was started even a little bit around 10 years ago. But our view was, as you mentioned, like, we wanted to focus on sleep. I think there's a couple reasons as to why we wanted to focus on it, but literally from the health aspect—and I think this is more longer term—but still there is a clear link between lack of sleep and all types of chronic disease like cardiovascular disease, cancer, longevity, just length of life, diabetes, and also Alzheimer's.

But if you look a little bit shorter term, we also think about it as it's literally the best performance-enhancing drug out there. I think Matt Walker said this, and he's absolutely right. If I told you or any of your patients or people that hey, or any of my friends, that you can take a drug that will increase your testosterone, literally improve your memory recall the next day, right? Will help you cognitively and emotionally, will help keep your insulin levels in check and prevent cardiovascular disease and help create more killer T cells that help fight off cancer, I feel like everyone would take that pill.

Chris Kresser: That’d be a trillion-dollar pill.

Harpreet Rai: It would probably be the biggest and most successful drug ever.

Chris Kresser: Yeah, and I tell this to my patients, and I know Pete Attia says this too, if you had to choose between letting your diet slip or letting your sleep slip, what would you choose? And a lot of people say diet over sleep. They’ll protect their diet over their sleep. But really, if you have to make that choice, which hopefully you don’t, diet is the obvious answer because if your sleep slips, you’re going to suffer far more and more quickly than if your diet slips.

Harpreet Rai: Exactly, yeah. So that's one of reasons we really focused on it. I think the other concept that’s starting to change, I think, a little bit now and we’re seeing in sort of the professional sports world, but also frankly, from a Functional Medicine world, thanks to people like you, is that if you want to feel better tomorrow, if you want to perform better tomorrow, you’ve got to start getting ready today before, and that starts with your sleep. So this idea of sleeping is sort of the leading indicator for how you can perform better tomorrow. Something that’s actionable.

Chris Kresser: Yeah.

Harpreet Rai: I think the last thing really is we’re really more distracted than ever. The average person is touching their cell phone about 10 times an hour. We have people who are watching more Netflix than ever, YouTube than ever, spending more time on emails. Frankly, eating later, food-ondemand restaurants open later, and all those things are taking away from our sleep. And so if we just look as a society on average, a third of the population is getting less than six hours.

I think overall, over the last 30 to 40 years, the amount of sleep as a society has fallen by one hour. And so it's also just causing people to be tired the next day, to have brain fog, and frankly, not to be as introspective. So I think it's this idea of being a little bit more conscious and being present. I think sleep is starting to, the lack of sleep is hurting our society as a whole on that.

Why Your Brain Needs Downtime

Chris Kresser: Yeah. I think you know about the default mode network, and in today's technology-addicted world, one of the consequences that we suffer from that is our brains don't enter this default mode network, which is really like, the easiest way to think of it is just downtime for the brain. We used to think that when we’re not, the brain wasn’t active, it was just at rest and nothing was happening. But now we know that's totally false and that when the brain is “at rest,” I’m doing air quotes, “at rest,” if we’re just kind of zoning out, looking out the window, daydreaming, the brain is incredibly active. And that activity is what generates creativity and innovation and new ways of thinking about things. And it’s restorative and rejuvenative.

And I've seen studies, I'm looking at one right now, actually, it's called “Sleep Quality and Adolescent Default Mode Network Connectivity.” And this study basically found that sleep deprivation, which is really common in adolescents and of course in adults too, led to reduced connectivity in the default mode network. So that would be expected to lead to lower creativity, less capacity to think out-of-the-box and in adolescents, actually, in this study they’re speculating that it interferes with brain development. So this is pretty serious stuff.

Harpreet Rai: Yeah, I think that's without a doubt. It's funny, right? I think there's two aspects where I looked into that on that thread is just think about sleep and when we go into REM sleep. So when you go into REM sleep, your frontal cortex, the sergeant of your brain, shuts off, and so your brain actually literally explores. And it's in this phase that most of our memory consolidation happens. Your brain starts playing those memories of what happened during the day, three times at 3X speed. So it's, like, fast-forwarding everything and it’s literally repetition, repetition, and that helps memory consolidation.

But the other thing on that thread of, like, when your brain is allowed to wander, like you said, during the day, there's a great course on this on Coursera and it’s called Learning How to Learn. And I think it’s created by two professors out at University … UCSD in San Diego, and then also McMaster. And what they talk about is exactly what you're saying that study cited, is that actually this downtime is when diffuse learning happens. It's when that mental conductivity happens. And from digital devices today, if you're literally checking your phone once every 10 minutes, your brain isn’t allowed to wander.

It's coming back, it's checking in, it's actually probably getting back to that addiction type mentality that so many of us have from other things like trading stocks or bitcoin, and frankly, that is without a doubt hurting productivity and just your mental ability as a whole.

Chris Kresser: It’s activating the dopamine reward system over and over again, and that's a certain kind of goal-driven mental state to be in that can be highly productive and useful, but not … that's not a state that we’re supposed to be in 24/7. And if we are, then as you said, we miss out on all of the deeper kinds of learning and growth and evolution that can happen in our brain. And I think it's a … I did a two-hour presentation on technology addiction and its effects on the health and the brain for the Health Coach Training Program.

And in the course of researching for that, I became quite alarmed, to be honest. I mean, this is something I've been aware of for a long time, so it wasn't a surprise, but doing the actual research and pulling it all together, it was like, this is a serious threat to humanity. I mean, I don't think most people actually realize how significant this can be.

Harpreet Rai: I think Tristan Harris, he’s—

Chris Kresser: Former Google.

Harpreet Rai: Exactly. Like, I forget his exact title though. The chief ethical officer? I’m not entirely sure.

Chris Kresser: Yeah, yeah.

Harpreet Rai: But yeah, these things are getting more and more addicting. I use, I think over a billion people use Chrome, the web browser.

Chris Kresser: Right, yes.

Harpreet Rai: And there is this new thing in Chrome on mobile where, I don’t know how they decided to roll this out, but when you open a new tab now, at least for me and I know many others who I’ve checked with on this, is that you’ll have the Google search box and then underneath you’ll see like six or eight stories. And literally they’re all news articles about things that you’ve been searching recently. And what is that designed to do? I mean, let’s get real. It’s designed to keep you clicking more, spend more time in Chrome. Why? If you spend more time in Chrome, you’re looking at more ads.

Chris Kresser: You’re worth more to advertisers.

Harpreet Rai: Yeah, you’re worth more to advertisers. More time spent, right? You’re driving those impressions up, and so it’s amazing. I saw that in myself. Well, okay, I went from having 10 Chrome windows open, or tabs open, to all of a sudden 20 or 30. And I had to find out how to look up, how to remove that from my phone. But what if we started checking with ourselves as often as we check in with our phones? I know there’s been, like, sayings like that before out there on Instagram. But I think it's really true, and sleep is a form of checking in, and I think we’re going to talk about heart rate variability.

But look, we see this from our users. So many users will post stories, will send us screenshots of their data, and they say, “Hey, when I went camping for two weeks” or “I went on vacation or even camping for two nights,” all of a sudden you'll see deep sleep improved, you'll see your heart rate variability improve, not as much disturbances. And we sort of ask ourselves as a company, we’re like, oh, wow, that’s awesome. Why is that happening? Well, there could be a ton of things. It could be happening because actually you’re sleeping outside, the ground is colder, and so as a result, we know that a cool temperature at night helps improve deep sleep. Okay, that could be something. The other reason is the light goes down, right?

So the sun goes down at six, seven o’clock, depending on the time of the year and where you are. Okay, so actually melatonin is being released at the right time. And probably the third reason if I had to guess is, or fourth reason, you’re out in nature, you’re in the trees. We know there’s some positive effects there. But you're probably not looking at your phone as much.

Chris Kresser: Absolutely, 100 percent.

Using Technology to Improve Your Health

Harpreet Rai: Yeah, you’re there in the present, you’re with friends, your mind is being stimulated in nature just walking. And so I think us as a company, I think we’ve thought about using technology for improving our health, using technology to improve our consciousness, and I think that's another reason why we focus more on sleep. Because when some of these things don't happen, you do see that data reflected in your sleep. Or perhaps in your heart rate variability. And so those are a couple reasons as to why we focused on sleep.

Chris Kresser: Yeah. I’m glad you did because people need help. We all need help. Everyone’s susceptible in this society that we live in now. Sleep is not something that's valued. There's all kinds of sayings that reflect that. Like, “I’ll sleep when I’m dead,” is one of the most interesting ones to me because it’s like, well, yeah, you’ll be dead a lot sooner if you don’t sleep. So I guess you’ll get more that way. But it’s just, we live in a culture that is, you’re kind of fighting an uphill battle if you’re trying to get sleep because there's so many influences that interfere with it. From the blue light that devices emit to Netflix’s autoplay feature—now, if you watch something on Netflix, before you can even lean over and turn it off, it’s already going on to the next one. And it’s just another way that our attention is kind of hijacked. So having, to me, that’s when the biggest benefits of a device like this is it’s basically an awareness enhancer. It’s something that can remind us to pay attention.

Harpreet Rai: Yeah.

Chris Kresser: When we bring our attention to something, that’s what enables us to change it. I had a, one of my then-teachers in the past liked to say, “The focus of your attention determines the quality of your experience.” Which really is a powerful saying if you think about it. It's only what we are attending to that is going to drive our quality of life and our experience, and we only experience and remember what we pay attention to.

So the most powerful thing for me around this is thinking about myself, like, I call it the rocking chair test, where I’m 100 years old and I’m looking back, am I going to want to look back on a life where I spent a large part of my day, like, staring at my phone? Or am I going to want to look back on a life that was richer and more fully lived? And I know what the answer to that question is, and that’s what drives a lot of my choices. But like anyone else, I need reminders and help. And that’s where something like this can be really useful because it’s just a non-intrusive guide that I’ll just occasionally … I don’t do it every day because I’m pretty tuned in to my rhythms at this point. But if I make some kind of change or intervention, then I have a way of getting immediate feedback on what the results of that were in terms of my sleep and heart rate variability, which is pretty cool.

That’s something that took longer in the past. More experimentation and trying to figure those things out, but let’s say I’m like, “Okay, I want to check and see what happens if I eat a snack before bed. How does that affect my sleep?” I can immediately get that feedback in a way that I couldn’t get before, which is pretty cool.

Harpreet Rai: I mean, frankly, your example of a snack before bed, I have no problem putting this out there. I love ice cream. I think a lot of Americans do.

Chris Kresser: What’s not to like?

Harpreet Rai: What’s not to like? I think it’s something like, guess how many pounds of ice cream the average American eats in a year.

Chris Kresser: Oh, it’s probably …

Harpreet Rai: Take a guess.

Chris Kresser: Jeez, I don’t know. Let’s see, 100?

Harpreet Rai: Oh, no, it’s not that bad.

Chris Kresser: I think it would be. If you think about, like, if they’re only eating, if that was the only source of sugar, it probably would.

Harpreet Rai: Sure, oh, of course, yeah. I think it’s something like 23 pounds.

Chris Kresser: Yeah.

Harpreet Rai: So or …

Chris Kresser: Twenty pounds is an enormous amount of ice cream, though.

Harpreet Rai: It’s actually, so it’s surprising. It’s actually … it is an … it’s not. It’s, “a pint’s a pound the whole way around,” I think is the saying. So a pint, 16 ounces, what’s in that standard Ben & Jerry’s little thing that people love to eat including myself, that’s a pint. And when I first got an Oura Ring a few years ago when we were working on this and the Kickstarter just launched, I remember like, yeah, every once in awhile, I’m not going to lie, I’d be, “Oh, it would be a cheat day.” Or I’d been keto for about 30 days in a row, I want to start to disrupt the cycle and I reach for something that’s absolutely terrible for me. And normally you’re having a dessert close to your bedtime.

Chris Kresser: Yeah.