#not because these things are untrue but because that's neither the lens through which he sees himself nor where his arc focuses

Text

I've seen a lot of analysis of Chuuya's character focusing on being used or controlled, and I think I see it a bit differenly than most of what I've read, so here's some of my thoughts.

Control and lack thereof is, of course, a major theme in his arc. He was made how he is against his will, had his past taken away from him, and was being used for his strength by the Sheep, before getting blackmailed to join the mafia. However, in present time, and, in my opinion, from Stormbringer and onwards, Chuuya is essentially only being controlled by his own self (excluding the vampirism, of course). Let me explain.

Chuuya, likely because of his need to cling onto his humanity, has always been people-oriented. He knows that he holds more power than most, and is therefore obligated to protect others with it. Shirase and the Sheep don't need to tell him that, even though they do. He knows and believes it himself regardless. We can see that because he acts the same even around people who don't rely on him (the Flags).

Before Stormbringer, he might have acted this way because it was instilled into him by others. Through the events of Stormbringer, Chuuya becomes more confident in his own nature. He understands Verlaine and how he ended up the way that he is, and decides that's not gonna be him. He sees Dazai trying to discard his humanity, and decides that's not gonna be him. He is gonna be his own person, and his own person is someone who puts others before himself. He describes this process himself to Verlaine, saying that even if he wanted to kill N, which he probably did, he can't do that, because he is obligated to find the truth for the sake of his dead friends. That's a decision that's focused on others, but he is the one making it, and it's important to him that he is the one making it.

From that point on, he continues to make similar choices. First of all at the end of Stormbringer, when he immediately decides on saving Yokohama from destruction instead of learning the truth about himself, and the fact that he is the one making the choice is emphasised. Dazai gives him another choice, and he doesn't even need two minutes to consider it, because, by that point, he's only staying true to who he is. The same is true for Dead Apple, when he doesn't hesitate to use corruption without knowing if Dazai is alive.

I think that if we were to pinpoint a specific point in time where this solidified in his mind, it would be right after he was tortured by N. His hallucinations fed him his own doubts and fears, and, by the point he snapped out of them and decided to fight Verlaine instead of N, he knew that, human or not, he is his own person with his own emotions and he will stay true to that. It's likely that he didn't exactly put all of this into words in his mind, but it becomes very clear when he says that Verlaine "is just an ordinary human. He gets mad, he worries... That doesn't seem to be enough for him, though". He's confused when Adam implies so, but what his words mean is that it is, in fact, enough for Chuuya.

My point is that yes, Chuuya has always used his power way more often for the sake of others than himself, but the reason he does so, the reason he allows it, is simply the fact that he is Chuuya. If he's unable to stop acting that way, which he admits that he is, it's not because others are controlling him. It's because he is who he is. Whether or not that means he is free or not is beyond the point of this post, because it's sort of a circular process, where his own will is to act for the sake of others. But I do think, for example, that he wouldn't see himself the way a good chunk of the fandom sees him.

(also this is kind of a continuation of this post, or at least related to it, so check here for more chuuya ponderings)

#chuuya would not complain about being a second choice or being left behind#not because these things are untrue but because that's neither the lens through which he sees himself nor where his arc focuses#the stormbringer reread is taking me so long because i stop and analyse everything (wouldn't have it any other way)#next up another dazai post because i had sort of a moment where thoughts fell into place#or verlaine/rimbaud post because they make me ill#bungou stray dogs#bsd#bsd stormbringer#chuuya nakahara#nakahara chuuya#bsd analysis

124 notes

·

View notes

Text

not to think seriously about the samelia arc but idk something interesting there through the lens of aromantic dean coming back and just. not getting it.

One of the first things he asks Sam about what happened while he was gone is “was there a girl?” and when told there was, he’s very upset by that. There was a girl, and in Dean’s mind, Sam chose her over Dean. And wants to continue choosing her! Wants to go back to her, says as much about wanting to go back to that life and almost does after the text message debacle!

And looking at this from Dean’s POV, Dean who tried to have that same kind of Normal Heterosexual Romance Life with lisa, and who it didn’t work for. could never quite make himself fit into place, couldn’t give her things he wasn’t even aware he couldn’t feel. who, as soon as he knew Sam was alive, made it a priority to stick close to his brother even at the expense of that relationship with Lisa. Like. Of course Dean doesn’t get what Sam wants with Amelia. He tried it! He lived it! For him, it felt wrong!

His life with Sam, for all that it’s a fucked up one, is more fulfilling to him than “being in love” with Lisa, and so even beyond the fact that he’s always going to need to choose Sam because that’s been his job since he was a kid, he’s always going to want to choose Sam.

and the idea that there’s some hierarchy of relationships for Sam where Dean isn’t the one he wants to spend his life with? That’s terrifying and confusing to him (if completely untrue, since Sam also proves time and time again that in the end he’ll always choose Dean.) Dean’s got no idea what being aromantic actually is, he’s Dean. Meaning to him, what he had with Lisa is either what everyone gets out of a romantic relationship or he’s broken in ways other people aren’t, depending on how much he hates himself that day. Neither of which are true, but you can see how, with that assumption, the idea that Sam wants to leave this life with him for a woman he met less than a year ago is kind of hard for him to process.

#does this make any sense lmao#Dean 🤝 me: ‘why is this person so special to u? u love them? that sounds fake. I’m the one you’ve known forever.’#it’s this weird intersection of jealousy society says you’re not allowed to have because your friend/brother is Right to put their romantic#partner before you in every situation (fucked up). and not understanding the hype because. u don’t get those feelings. don’t happen to you#staring at amatonormativity and feeling like shit that you’re on the outside of everything#which. clearly. would aggravate uh All Of Dean’s Issues.#this man can fit so much abandonment in him#anyway. Dean’s reaction to Amelia bad for many reasons but understandable too for many reasons.#but especially if he’s aromantic and Does Not Get why sam thinks loving this woman is a fair enough reason to leave his life with dean#spn#dean winchester#aro!dean

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

These days, my older brother Jake is a calm, competent professional. He’s skilled at his job, and so laid-back and reserved that it actually used to intimidate his students when he TA’d classes. That’s now. Back when he was a little kid, he was scared of everything.

Bugs. Balloons. The vacuum cleaner. Basically any loud noise. The dark. Dogs. The basement.

As I child, I feared neither god nor death, and so it was my job to protect my big brother from all the minutiae of life that he found terrifying.

Being afraid of the basement was a real problem, because his bedroom was in the basement. I used to have to go downstairs every night and turn on all the lights before he would come downstairs. Once I’d done that he was fine.

At least he was fine up until he thought it would be fun to spend an afternoon building a spooky fort in his walk-in closet and tell scary stories in it. The four of us huddled in the dark closet-fort with a flashlight and Jake cooked up the scariest story he could: that our house was actually built on top of an old burial ground, and there were horrible undead monsters under the floors, trying to claw their way up. This was a very scary story indeed, and my younger brother and sister were terrified. I was old enough to remember when the house had been built, however, and therefore knew for a fact that the story was untrue.

Jake, despite also having been there when the house was built, and having made up the story himself, was terrified.

He spent the next week insisting that I not only turn on all the lights for him before bed, but also check all the closets and make sure that there were no sounds coming from the floor under his bed. Which I did, dutifully, every night.

And then came the day that he punched me in the face and broke the lens out of my glasses.

Now, we roughoused a lot. Scraped knees and elbows were absolutely the norm, and mostly that was fine. But an outright punch to the face? Heinous. Unforgivable. Deserving of the direst revenge my seven-year-old brain could concoct.

“Mom and Dad are gonna kill you when they find out you broke my glasses,” I told him, and quietly slid my foot over the fallen lens where it rested in the front lawn. “You better find that lens or you’re gonna be in trouble until you die.”

Jake, who already knew that he’d crossed a line, went pale and immediately began scrabbling through the grass for the lost lens. I waited long enough for him to turn away before lifted my foot, pocketed the lens, and went inside to sit on the couch and watch him freak out.

He spent a good hour looking for the lens before he went inside and realized I’d already fixed my glasses.

I had spent that hour in my most natural state: scheming.

So when night fell, I did my usual basement sweep. I turned on all the lights, loudly opened and closed the closet doors, and then returned upstairs to give Jake the all-clear. “It’s fine,” I told him, “Only....”

“WHAT,” Jake demanded, thoroughly terrified of monsters entirely of his own making, and not at all afraid of the only thing in the house worth fearing, which was, of course, me. (Our ancient and malevolent demoncat, Kitten Little, was also worth fearing, but that is a story for another time.) At age seven, I had never heard of the concept of ‘excessive force.’ I had also never heard of the concept of ‘psychological warfare,’ but that was hardly going to stop me from using it. Jake demanded, “What was down there?? What did you see?”

“Oh, nothing. But maybe...I thought I saw eyes? Glowing eyes? Under your bed.”

“GLOWING EYES UNDER MY BED??”

“Probably it was just Kitten Little. Goodnight!”

I bounced upstairs to my room in the attic of the house. The ceiling was plastered with glowy stars, and I flopped down in my bunkbed and watched them idly while I waited for the rest of the house to settle down to sleep. One by one, lights turned off across the house, and soon the only noise was the creaking of the old oak tree outside my window.

I reached up and removed one of the jumbo-sized stars from my ceiling. There was a wad of sticky tack on the back. Quietly, I slipped into the bathroom, turned on the lights, and carefully drew two eye-shapes on the star, as large as would fit. Using the pair of scissors I’d stashed in a drawer earlier, I cut the shapes out of the heavy plastic star. Then I used the sticky tack to attach one to each of the lenses of my freshly-repaired glasses.

And then I snuck down to the basement, and army-crawled under Jake’s bed.

Now, I’d been patient. It was well after midnight; everyone else was deeply asleep. That was about to change.

I set my nails against the underside of Jake’s bed and dragged them loudly. I pushed up with my legs just enough to shift the bed a little. I could hear him starting to wake up, so quietly, using a deep, grating growl I’d spent all afternoon practicing, (and which, later in life, would scare our class bully so badly he fell backwards out of a hay wagon) I moaned, “JAAAAAAAAAAAKE.”

Slowly, visibly terrified, Jake lowered his head over the edge of the of the bed.

I whipped my head sideways and shoved my legs against the wall as hard as I could, launching my glowing-eyed face towards him like a snake.

Jake shrieked.

Something thumped overhead as everyone in the bedrooms upstairs woke up all at once. I knew I had about sixty seconds of getaway time while Jake cowered under his blankets. I crawled out the door, making sure to move as oddly as possible in case he could see me, and darted into one of the unfinished storage rooms down the hall. I waited until I had heard both parents go into Jake’s room before I sipped out and quietly returned to my room.

Jake insisted on sleeping in my parent’s bedroom for the next month.

At the opposite end of the house, I slept peacefully every night.

On the ceiling over my head, carefully attached with sticky-tack, were two glowing eyes.

30K notes

·

View notes

Note

Communist anon here - Yes to all of them?

@eyeofnewtblog said: I personally would be very interested in hearing an educated opinion on theories and practice

This is going to be a long answer so under a cut it goes. The short answer is no, I do not like either Marxism or communism, to the point where I consider myself anti-communist. The long answer goes under the cut.

First, it’s important to remember where I am coming from, what I am, and what I am not. I’m neither educated in philosophy nor history. I study both, and I have had classes in both, but that doesn’t mean that I’m an expert in either, and my experiences with Marxism have largely been academic, instructors attempting to tell me what Marxism is (fun fact: I once made a lot of these theoretical arguments to a Marxist professor on an exam - I was given an F). So if you’re looking for an educated opinion, depending on what that means, I don’t have one, after all, I got an F on it. Similarly, while I do study some philosophy, it is by no means something I’ve been trained it or seriously articulated; my observations primarily come from observing human nature and studying history and political movements. In that sense, I’m far closer to Eric Hoffer than I am to Hannah Arendt (though both as philosophical scholars far exceed me in every sense that to be compared to them would not be an honor to me but an insult to them). I’m a believer in liberalism and democracy, and a radical individualist, which to me means that people have an inherent dignity, and should be free to determine who they are, what they want to do, and what they value. It’s not a fully-fleshed out philosophy with rules, I’ve already said I’m no philosopher. I just do the best I can and handle situations as they come up.

Those values put me at odds with Marxism from the get-go. Marxism articulates the necessity of a dictatorship, the “dictatorship of the proletariat,” where the government following the revolution seizes the means of production, nationalizing all industries and property, and transition to a communist society, preserving the power of the state to suppress any reactionary or counter-revolutionary activity. I’ve heard this line before; this sounds remarkably similar to authoritarian measures enacted in tinpot dictatorial states meant to preserve order and enforce the power of the government to suppress dissent. The “transitional state” sounds a lot like perpetual “state of emergency” laws enacted to keep the populations in line, a theoretical end-state where such measures are no longer necessary is always on the horizon, but just like the horizon, is never reachable. Call me crazy, but I don’t see how putting people under control of a dictatorship with such unlimited powers is liberating them, save in a metaphorical, dogmatic sense that rationalizes their subjugation as necessary. There’s a broad appeal there, violent mass movements definitely find a lot of support from individuals who see it as a means to finally lord power over those they hate; individuals who want those they despise cowering before them, begging them not to bring the axe down. Such motivations have been an incentive for aspiring foot soldiers to put on their jackboots, so that they eagerly stomp the faces in of the people they despise, and to rationalize it away.

Marxism depends on a lot of things that are untrue, like his assertion that the rate of profit tending to fall, or the labor theory of value which has few serious practitioners and has been widely debunked to the point where Shimshon Bichler was able to criticize the lack of statistical correlation and the degree by which abstract labor must be assumed to see the labor theory of value as purely circular reasoning, hardly compelling for a central tenet of the philosophy to depend on a set of assumptions that rely on others being produced. While I’m no philosopher and reality is impossible to condense into any one singular lens, the degree by which Marxism is riddled with intellectual and logical inconsistencies make it difficult for me as a thinker to take it as seriously as others do. Other matters, while not necessarily untrue, become difficult to function when brought from theory to reality. Take the standard line: “From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs.” How are ability and need for each person assessed? What happens if someone is incapable of producing something to the level of ability that is assessed? What happens if someone needs more than is assessed? What happens if need outpaces supply? What happens if ability cannot meet need? What happens if there’s a disaster and there is a temporary shortage? These extend outwards to questions of land use, industrial capacity, training, etc., these centralized economically planned models failed in the 20th century, and again, this turns me off to the model. This is not simply a matter of corrupt Communist Party officials degrading the functioning of the government for personal enrichment, this is a serious information problem that even the most powerful computers of today cannot model and manage, and the idea of a communist state becomes much diminished in appeal to me.

Other stuff in Marxism goes further into what I consider downright repugnant. The idea of “false consciousness” is particularly disgusting to me, where if someone is not motivated by that which the Marxist believes that they should be motivated, these conceptions are deluded and must be corrected. That is such a statement of such monumental arrogance I’m surprised it doesn’t have its own gravity well. It is to say to one person that whatever meaning they have discovered through their own experiences is less valid; it is to say that the Marxist may state that whatever said person values is not in their own benefit. The logical conclusion from this is that non-Marxists cannot be allowed their own judgment, that they must be shaped until they embody the Marxist conception of reality and only then are they truly full people, capable of making judgments of this fashion and assessing what is to their benefit and what is not. For a movement that espouses equality and liberation, sure as hell doesn’t seem very equal to me; only our practitioners are capable, rational beings? No.

Now, most Marxists I know don’t really believe this, but I think this is more of their own conception. Like most practitioners of religions or other philosophies, they pick and choose what tenets to follow.

Communism is practice has been a disaster. Lenin really ran with the idea of the dictatorship of the proletariat with his vanguard model, making the centralizing dictatorship a core part of his leadership and in charge of everything, to the point where failure to provide the dictatorship with what they demanded was considered treason and grounds for termination, and later communist regimes really ran with this idea, as I’ve mentioned before, Marxism appeals to revolutionary dictatorships because it justifies the dictatorship beyond a naked power grab to better secure it. Similarly, Lenin rationalized ignoring his citizens by simply ignoring elections when he lost; the Leninist model was openly a sham democracy. In the Soviet Union, even Khrushchev, who gave the Secret Speech denouncing Stalin, still sent the tanks into Hungary and forcibly medicated any who disagreed with the principles of communism as mentally ill (my previous paragraph is not jumping to conclusions, this was a documented fact). Mao created the “mass line,” a means to consult the population while mandating interpreting their wishes through the ideology, thus dismissing anything that the dictator doesn’t want, a clever fig leaf. Of course, Mao’s already deeply unworthy with its massive loss of life - the Great Chinese Famine was the largest famine in history and enacted by the ideological dogmas of the Great Leap Forward and Mao’s Cultural Revolution was doubling down on his mistakes, murdering those who opposed him. The brutality though, has been the biggest failure; there’s a reason the European left jumped to the social democrat model with the rise of Keynesian economics in the aftermath of World War II, they felt it was a way to achieve their objectives without the brutality of the Soviet model. The totalitarian conception of power and identity left its mark on the movement, but I don’t see them as inventions by power-mad dictators, they were extensions of the philosophy that saw only its practitioners as fully human.

Even discounting the brutality, the standard of living and industrial capacity of communist countries has been low comparatively. In 1927, the Soviet Union produced a scant 3 million tons of steel despite massive advantages in natural resources and manpower, compared to Germany’s 16 million tons, Britain’s 9 million, and France’s 8 million. Relatively speaking, more resources were wasted in steel production in the USSR, and this was similar across the board in communist countries. Communism lambasted capitalism for its wastefulness, but the numbers show that communism was the far more wasteful, inefficient method of economic organization. Some defenders of the Soviet Union point to the growth under leaders like Khrushchev, but I counter that the exceptional rate of growth was both temporary and comparatively small compared to non-communist states. Francis Spufford may have tried to sell it with the idea of Red Plenty as a fusion of history and fiction, but history has borne out that it was entirely fiction.

The more anarchist sects of the movement, the ones who reject the transitional state, similarly were failures in practice. In Spain, those who did not wish to join were often brutalized, which seems to me to be violating the principal of anarchism in that forced compliance in an anarchist society is an extension and use of state power. This is relatively common throughout history though, particularly when it comes to ideology. The Soviet Union decried “imperialism” but was incredibly imperialist, just as the United States decried the security state apparatus of the Soviet Union as violating the rights of their own citizens while pursuing COINTELPRO when it came to folks like Fred Hampton. In a more practical sense, the anarchists poor training and suboptimal deployment were unable to stop Franco despite having plenty of clear advantages in the Spanish Civil War. While they are by no means the only reason for the Republican failure, the inability for the anarchist faction to defend their people is a failure of their system of government. A lot of anarchist models run into this problem, it should not be thought of as a failure reserved solely for the anarcho-communist model, and anyone who says it doesn’t is ignoring history.

So to sum up, I consider Marxism to be a philosophy which espouses tenets that I find disgusting, and it’s articulation of government to be illiberal, anti-democratic, and founded on the violation of human rights and dignity.

Thanks for the question, Anons who were waiting.

SomethingLikeALawyer, Hand of the King

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Review

Radiance. By Grace Draven. Self-Published, 2014.

Rating: 2/5 stars

Genre: fantasy romance

Part of a Series? Yes, Wraith Kings #1

Summary: THE PRINCE OF NO VALUE

Brishen Khaskem, prince of the Kai, has lived content as the nonessential spare heir to a throne secured many times over. A trade and political alliance between the human kingdom of Gaur and the Kai kingdom of Bast-Haradis requires that he marry a Gauri woman to seal the treaty. Always a dutiful son, Brishen agrees to the marriage and discovers his bride is as ugly as he expected and more beautiful than he could have imagined.

THE NOBLEWOMAN OF NO IMPORTANCE

Ildiko, niece of the Gauri king, has always known her only worth to the royal family lay in a strategic marriage. Resigned to her fate, she is horrified to learn that her intended groom isn’t just a foreign aristocrat but the younger prince of a people neither familiar nor human. Bound to her new husband, Ildiko will leave behind all she’s known to embrace a man shrouded in darkness but with a soul forged by light.

Two people brought together by the trappings of duty and politics will discover they are destined for each other, even as the powers of a hostile kingdom scheme to tear them apart.

***Full review under the cut.***

Trigger/Content Warnings: sexual content, bullying, violence, blood; references to infanticide, ableism, torture, and incest

Overview: I learned of this book when an artist I follow on tumblr mentioned it as one of their favorites. I had high hopes after seeing so many 4 and 5 star reviews, but unfortunately for me, I wasn’t as enthusiastic as most people seem to be. While I did appreciate that the hero wasn’t a gruff, emotionally damaged, violent man, I personally found the story as a whole to be rather dull. There were way too many scenes that focused on domestic life at the Kai castles, and while that could have been an interesting plot in itself if the stakes were high enough, the political drama wasn’t developed enough to be thrilling, nor was the Kai court different enough from the human one to be a tale about immersing oneself in a new culture. Even looking at this book purely through the lens of romance, I don’t think there was enough there; while I don’t think the hero should have been mean to the heroine or something like that, I do think the relationship could have benefitted from developing a little more, and for Draven to have really dug into the nuances of what changes when a couple moves from friends to lovers. Thus, this book only gets 2 stars from me.

Writing: Draven has a simple writing style that fits well within the romance genre. It flows well and balances telling and showing so that worldbuilding doesn’t feel too info-dumpy. My biggest complaints are things that are easily fixable, like correcting typos and moving flashbacks around so that they occur at more appropriate moments. Other than that, I don’t have too much to say about the writing; it was fine.

Plot: In a way, this book is a Beauty and the Beast retelling: two people must overcome their revulsion to the other’s appearance before they fall in love with the good character underneath. Behind this main plot is a political drama in which several kingdoms are vying for territory, making and breaking alliances while a conniving queen does her best to stay in power.

Regarding the Beauty and the Beast plot, I really liked that Radiance seemed to adhere more closely to the core themes of the original fairy tale than a lot of other retellings I’ve encountered; instead of a story about a woman trying to tame the “bestial” man with her womanly charms, both characters in Draven’s book have to learn to see the other as beautiful by learning to appreciate one another’s culture. The main scenes that come to mind that do this well are the times when Ildiko (our heroine) finds beauty in the Kai death ritual (the mortem light) and when her expectations are subverted when it comes to the food the Kai eat (not the scarpatine, but the other dishes). I also liked that Draven devoted a lot of time to detailing why the Kai found human eyes so off-putting, and Brishen (our hero) comes to appreciate them when learning to read his wife’s emotions. If anything, my main complaint is that I think Draven could have done more to enhance these themes by tweaking her worldbuilding; the Kai were different from humans in a lot of ways, but so much was the same (court politics, social hierarchy, etc.) that I think the task of learning to appreciate a different culture wasn’t difficult enough. I would have liked to see the Kai have a completely different social structure, one that was so alien to the human characters that learning to see the beauty in it proved to be more of a challenge. Because adapting wasn’t too hard and Brishen and Ildiko seemed to have no moments where they suddenly realized they loved rather than just respected or liked the other, I was frequently bored, mostly because there were so many domestic scenes without relationship milestones - instances where Ildiko and Brishen came together as a couple, bonding over things that challenged them to grow as people.

The political plot, in my opinion, was a little ho-hum and wasn’t nearly present enough to be important. We are told that there are rising tensions between three kingdoms, and some people disapprove of the marriage alliance between Brishen and Ildiko, but it kind of felt like a background threat, in part because there were so many scenes depicting feasts (4, by my count) rather than political intrigue, or we get scenes like Ildiko dropping her mother’s necklace in a vat of dye and then Brishen offers to take her to the next town to repair it. Sure, a couple of bandits try to kill Brishen and Ildiko, and some treachery happens later in the book, but the middle section mainly consists of feast scenes, domestic life, or petty drama. I wanted a little more substance to the non-romance plot; perhaps the marriage could have been more explicitly important for the well-being of the Kai kingdom as a whole, and Ildiko has to use her skills to make the Kai more loyal to her. Or, Draven could have gone another route and made the Kai queen to have a clearer political agenda throughout the book other than just being mean to everyone around her. It is mentioned that Brishen and his brother are afraid to cross her in part because magical ability diminishes with each successive generation; maybe that could have been a major focal point or hurdle when plotting against the Queen, rather than an incidental detail that only returns later in the book. Either way, I wanted the politics to be more than just background, and for there to be much higher stakes that will be felt by more people than just Brishen and Ildiko.

Characters: Ildiko, our heroine, is a human woman who enters into an arranged marriage with a Kai prince in order to seal an alliance. I really liked that a lot of the story was centered on Ildiko learning to acclimate to Kai culture and navigate their court politics, and I think it was smart to show that her experience as a courtier in the human kingdom helped her survive the Kai one. I do wish Ildiko’s personal arc had been more about her overcoming her prejudices to appreciate a different culture; while Ildiko isn’t outright racist or resistant to adapting, I do think it would have been more emotionally satisfying if she had clearly entered the marriage with a lot of assumptions about the Kai that turned out to be untrue. If that didn’t sound appealing, maybe Ildiko’s ability to navigate court politics could have been more integral to the plot as a whole, rather than her rather passive role during the final showdown.

Brishen, our hero, was a pleasant surprise; he was kind and considerate, and he didn’t let his power-hungry parents turn him into a gruff, emotionally-unavailable husband. While I did like that he was kind, I also wish his personal arc had been more about overcoming his assumptions about humans or overcoming some other personal conflict, such as balancing his duty to his people/kingdom with his desire to escape the more toxic elements of it. In that regard, I think his romance with Ildiko could have served an interesting purpose: by teaching Ildiko about his culture, he learns to appreciate it more while also finding an escape in her. It would also be cool if he realized that duty doesn’t necessarily mean obeying the monarchs, but doing what’s best for the people.

Supporting characters were a mixed bag. Some, like Brishen’s cousin Anhuset, were interesting but didn’t seem to have a subplot of their own, while others, like Queen Secmet, seemed one-dimensional. In some ways, the one-dimensional characters ensured that most of the focus was on Brishen and Ildiko, but I would have liked a little less feasting and a little more high-stakes conflict that involved these side characters functioning in ways that developed their own arcs.

Romance: Ildiko’s and Brishen’s romance follows a friends-to-lovers arc. When the characters first meet, they instantly bond over their willingness to be honest about their feelings regarding the other’s appearance and culture. I liked that they didn’t start out as completely repulsed by one another, and the friendship bond made for a good safety net when Ildiko has to face the Kai court. I do wish, however, that there had been more explicit developments in showing how the relationship moves from friendship to romantic love. For example, I would have liked scenes where Ildiko has moments of realization regarding what a good man Brishen is, and where Brishen realizes how good a woman his wife is, both in reaction to major plot points (rather than what we get, which is stuff like Ildiko watching Brishen prepare to spar or something). Some of those moments are there in the plot as-is - I’m thinking scenes like when Ildiko learns what an honor it is to have Brishen carry a mortem light for someone beneath his class - but I think there could have been a more defined romance arc.

Worldbuilding: I really liked that Draven didn’t feel the need to overwhelm the reader with worldbuilding details, but I also think she should have done more to make the world feel more purposefully crafted. My biggest problem with Draven’s worldbuilding is that certain elements seemed to be present for no reason at all, or because they were convenient details. For example, the Kai make this very expensive dye called amaranthine, and though we’re told that humans benefit from trading for it, the amaranthine isn’t really involved in an interesting way other than for Ildiko to accidentally stain her skin with in a moment of thoughtlessness. Also, during the last big showdown, we’re randomly told that there are magefinders and a temple which shields the Kai from these magefinders. It felt like these details were inserted for convenience, and I wish more was done to make the setting feel like a character itself.

TL;DR: Radiance does a good job at subverting some expectations, but ultimately doesn’t have a plot that challenges the characters to grow, either individually or as a couple.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

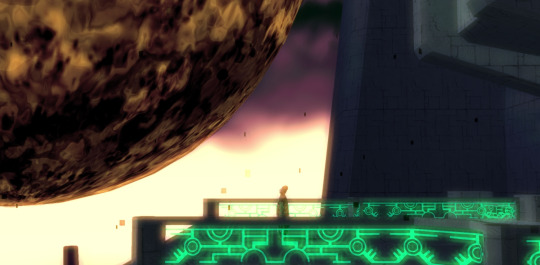

The Fate of Zant

The Usurper King’s is a story with which we are all intimately familiar; angry at the injustice of his people’s banishment and estranged by those who refused his rule, he flees the Palace of Twilight in a fit of anger one day, where he looks to the sky and finds his salvation in the form of Ganondorf, whom he believes to be a god. With his newfound power, he banishes the true ruler of the Twili and usurps her throne, transforming his own people into dark and malformed Shadow Beasts - and with them at his side he invades the World of Light, storming Hyrule Castle and scattering the land’s Light Spirits in all but one fell swoop. He commits countless atrocities, reducing Kakariko Village to a mere village of three, murdering the Zora Queen as a sheer display of power, and possibly even killing the King of Hyrule himself - but when all is said and done, he meets his demise at the hands of Hyrule’s hero and the very princess he had cursed, exploding in an agonizing but powerful display of the Fused Shadow’s might.

However, there is one scene in particular that always struck me as out-of-place in this overall narrative. It comes when Ganondorf finally meets his own demise at the hands of Link, and he stands alone on a hill, Master Sword struck center in the scar he received over a century ago. He gives us his last words - “The history of light and shadow will be written in blood!” he spits menacingly - but before he perishes, we cut to another scene, and are greeted with this:

It’s Zant, another evil man who recently perished himself, and he ostensibly looks down upon Ganondorf, before cracking his neck in a very morose, very fatal way. We cut back to Ganondorf, and only then do his eyes go white, and the wind blows over the field, signalling that finally, it’s over.

For a long time, I had assumed that this scene was meant to be symbolic: that Ganondorf, having had such a strong connection with Zant, was only able to perish because Zant, too, was already dead. But now - an incredible thirteen years later - I have come to believe that this isn’t the case, or, at the very least, there’s a chance it might not be, and I’d like to take a moment to talk about that here.

(Credit for this one 100% goes out to @therealflurrin, who also gave me permission to make this write-up. Their conversations are always an excellent source of primo TP content.)

Something that is important to understand about the relationship between Zant and Ganondorf is that it is one of co-dependence; Zant, angry but utterly powerless to do what he thinks needs to be done, is found by the bearer of the Triforce of Power in a moment of outrage and weakness. Ganondorf, reduced to mere a giant mass of malice and darkness in the Twilight Realm, tells Zant: “I shall house my power in you… If there is anything you desire, then I shall desire it, too.” From Zant’s perspective, it’s not hard to believe why he believed this to a blessing from a god; in a great moment of need, a powerful entity appeared before him, offering him seemingly unlimited power. But we know that Ganondorf is no god; that he only approaches Zant for reasons that are entirely self-serving, as a twisted and misshapen light dweller trapped in the realm of shadows. He allows Zant to house him and his power with the ultimate goal of being “reborn” and returning to Hyrule, tricks the Twili into believing him to be a “god” so that he will carry out his will unquestioningly - but ultimately, Ganondorf needed Zant just as much (if not far more) than Zant ever needed him.

We know from the very scene where Ganondorf’s death unfolds just how deep this co-dependency runs. It is my belief that the two formed a sort of “soul bond” following their initial encounter, intertwining their fates so that neither could perish while the other still lived; although Zant is not entirely aware of Ganondorf’s true nature, he is at least somewhat aware of this bond:

“As long as my master, Ganon, survives, he will resurrect me without cease!”

These are his very last words before Midna strikes him down, in a move that ultimately seems to be very final, indeed. But now we must return to the death of his supposed “master,” and the implications Zant’s appearance has in that moment. Ganondorf is on death’s doorstep for the second time; the first, at the hands of the Great Sages, it was the Triforce of Power that saved him - and now, here, he sees Zant in his final breaths, a beacon of hope in a great moment of need. But the scene plays out how we expect: Zant is already dead, and with nothing yet tethering him to life, Ganondorf meets his end, this time, for good.

Except there’s one teensy, tiny problem here, and I’m sure you can see where I’m going with this: Zant and Ganondorf’s relationship is one of co-dependency, as you’ll remember, their souls bound to one another in a fashion not entirely dissimilar to Zelda and Midna’s after the former gave up her own light in order to save the latter. If this were untrue, then we would not see Zant in the moments leading up to Ganondorf’s death; furthermore, if Zant were somehow already dead despite this co-dependency, then Ganondorf would simply keel over sometime shortly thereafter following Link’s decisive blow with the Master Sword.

Instead, there is a pivotal moment where Ganondorf’s fate is evidently sealed, and it’s the moment where we see Zant snap his neck - a display, which, frankly, was probably far too gruesome for a 10-year-old me playing through the game for the first time. It is immediately following this scene where Ganondorf reels back, releasing one final, raspy grunt as his life leaves his eyes, and Hyrule again knows peace. If Zant had died X amount of time before this ultimate battle, it seems very peculiar that Ganondorf would have such a sudden and visceral reaction to it, as if it had happened elsewhere, simultaneously.

So, let’s scrutinize this scene under the lens of their co-dependency; let’s say that, despite the destruction of his body, Zant was able to survive his final blow in some way, as his master still lived on. Following this, and going back to the initial scene, we can arrive at two simple conclusions:

That Zant was alive up until the very moment that Ganondorf perished, and

in that final, critical moment, he chose to sever their bond.

The question, then, is…why? Why would the Usurper King, who had once thought the Gerudo King his god, choose to sever the only thing keeping him alive? It’s true that Zant was undoubtedly a deeply troubled and hateful man; he was angry at the world of light and its inhabitants, whom he saw as oppressors, perhaps even rightly so - and he was angry at the Twilight Realm’s own “useless, do-nothing royal family that had resigned itself to [a] miserable half-existence.” But Ganondorf’s spirit is one of pure malice, and it had invaded the world on the other side of the mirror long, long before the story of Twilight Princess begins. One cannot help but wonder exactly what kind of effect such evil might have had on the realm and its denizens, though it is not hard to imagine the harborer of Demise’s Curse slowly and carefully plotting from the shadows, decades spent as whispers in the ears of the unknowing Twili until, finally, one suitable enough to become his vessel appeared - one who was vulnerable and angry enough to listen to those whispers, and would submit to anyone and anything if it meant obtaining the power to do what they thought was right.

Perhaps, then, Zant’s story is not one of an evil, bloodthirsty tyrant who met his rightful end at the hands of Link and Midna; perhaps his is a tragedy, the story of a man who fell victim to the malice residing within Ganondorf, only worsened the moment he became the Gerudo King’s vessel. Perhaps - lost in fugue state in the Twilight Realm, formless and lost, but still otherwise alive - it took the apparent death of a particular someone at the hands of his “god” in order to finally snap him back to his senses.

(Zant could have simply killed Midna when he usurped her throne, yet he didn’t. I personally think the two are related, but I can talk more about that in a different at a different time, as it is far more headcanon than analysis.)

Ultimately, nothing Zant could do could ever wash his hands of the blood that stained them, no matter how much Ganondorf might have in part been responsible - but in this one, critical moment, Zant, who had done such wrong and hurt so many, chose to do the right thing, even though that meant saving Hyrule, a world which he had so despised. Maybe he, too, perished when he severed his bond with Ganondorf - one final, noble act - or maybe he didn’t. Maybe, just maybe, on the other side of the mirror, there is yet another story waiting to unfold, one of a man who had done such wrong and hurt so many, willing to do anything and everything necessary to prove that he, too, is capable of change…

#zant#ganondorf#twilight princess#loz#legend of zelda#this didn't seem like the right post to talk about this#but i actually think that zant's anger toward the world of light is justified#the man deserves redemption#i think midna and zant are like...cousins#but like i said i can talk more about that later#tp!ganondorf#text#headcanons#analysis#mywriteups*#myposts*

161 notes

·

View notes

Note

you said something last night about the good place and the incantation, and I don't know what that means but I would very much like to if you can explain it.

::claps hands::

Necessary throat clearing I: I do not think Christianity is the thesis statement of The Good Place; Mike Schur has been extremely clear this story is not an argument for a particular philosophy. I’m not arguing that anything about the show is particularly religious, but rather that there are some natural analogues (from my point of view). The show is about philosophy, which has a natural overlap with theology at large. I’m not a pastor person, but I do have the same education as one. I’m also trained to look closely at narrative “texts.” Thus, here we are.

Back in 2012, Helen Sword wrote about nominalization – she coined the name zombie words because it’s easier to remember – which is when you take an adjective (implacable) or a verb (calibrate) or even another noun (crony) and add a suffix like ity, tion or ism. Think: implacability, calibration, cronyism, heteronormativity, etc.

Academics, scientists, - and philosophers/theologians eat nominalization for breakfast. They litter their writing with them. At best – nominalization help us put a name to big, complex ideas, and at worst it can be a tripping hazard to communicating with clarity. Sword cites a pretty famous essay by George Orwell Politics and the English Language, written in 1946.

Orwell warns how language isn’t just political in its content but in its form as well. He quotes a passage from the Bible, Ecclesiastes 9:11

I returned and saw under the sun, that the race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, neither yet bread to the wise, nor yet riches to men of understanding, nor yet favour to men of skill; but time and chance happeneth to them all.

Then Orwell wrote a modern version:

Objective considerations of contemporary phenomena compel the conclusion that success or failure in competitive activities exhibits no tendency to be commensurate with innate capacity, but that a considerable element of the unpredictable must invariably be taken into account.

Sword and Orwell argue that concrete language – that tethered to our five senses – is clearer. It endures, evocates, and energizes your audience. Nominalization has its uses, but should be used sparingly when communication – always a two-way street – is the goal. Cluttering our language with these zombie words is the best strategy for anyone who wants to talk, but cares very little about being heard.

I think The Good Place is an example of a story told in concrete language - though its a visual medium, and it is very much on purpose. But I’ll get to that...

First, let’s define the term Incarnation...Simply put, it is a theological assertion that Jesus Christ was both fully God and fully human. It is one of those key beliefs - take it away and whatever you’ve got isn’t Christian; This isn’t one of those down in the weeds, who cares? theological arguments.

Second, let’s talk about why the points system on The Good Place is fundamentally broken…

Remember Chidi’s breakdown earlier in the season with the peeps chili?

In that scene, he describes 3 main approaches in the last 2500 years of western philosophy to this question: how to live an ethical life?

· Virtue Ethics – (think Aristotle) There are certain virtues of the mind like courage, generosity, etc. One should develop oneself in accordance to those virtues. The emphasis is on human reason or our minds – what do I do with my mind

· Consequentialism - Is it right or is it wrong? is based on the consequences of that action - how much utility/good vs. how much pain/bad? The emphasis is on the result instead of the action - what happens to your [neighbor’s] body?

· Deontology - There are strict rules that everyone must adhere to in a functioning society; an ethical life is identifying & following those rules. The emphasis is on the action instead of the result - what do I do with my body?

(::screeches:: I’m VASTLY over-simplifying here.)

Each philosophical system Chidi outlines makes a priority choice with regards to my mind, my body, and your body. Each takes the mind, body, and other’s bodies into account, but each prioritizes one over the other as the loci – or starting place/lens - from which to answer the question, how to live an ethical life?

The Good Place uses Doug Forcett as the prime example this dynamic because he’s as close to a control group you can have in the story. He is the story-telling embodiment of this tension:

In any ethical system you cannot separate your mind (what you think/believe) from your body (your actions in the real world) or from the bodies of others (the consequences of those actions).

Please hear what I’m not saying - that these ethical systems are wrong. I am simply saying that none of them completely account for how three parts are inter-connected.

Doug’s attempt to live an ethical life is endlessly, hopelessly tangled in this ethical web. This is the catalyst for Michael to go to Accounting because he thinks the Bad Place is rigging the points system. But when that proves to be untrue – he jumps to another theory. He makes the case to the Judge that that modern life is so vastly complicated and fraught with moral quandaries that living any sort of morally positive life is impossible.

Yet, it’s total hubris to think our way of life is worse-better than the human condition 500+ years ago. It’s a fetishization of a single era. Even if we’re arguing that that era damns everyone. It simplifies and romanticizes the past and that is very dangerous because that sentimentality lets us lie to ourselves. We can excuse all kinds of human behavior by slapping the term modernity on it; our world made us do it. It’s a great example of how nominalization can be dangerous.

I’m confident the show knows this and Michael’s current theory will be proven to be as hollow as the ‘Bad Place is rigging it’ theory. Michael does not know how but he knows with the core of his demon-being that the merit-based “points” system is fundamentally broken.

Let’s talk about systems & power for a moment…

Last year I did some training with the Race Equity Institute for work. They started by talking about systems. We can all name systems: weather and water systems, the systems of the body and universe, economic and political ones, etc. Social systems – inter-connected people – are maybe the messiest systems there are.

Two important characteristics of any system are 1) the “parts” of the system are inter-connected and 2) the system self-perpetuates, i.e. the power lies in the inter-connectedness of the parts. Your mind & body – as well as the bodies of others – are part of an ethical system. They are inter-connected and there is power in that inter-connectedness.

An ethical life is always bound up in the systems to which we belong, and those systems create mindsets. Yet, the power of those systems is not in the nominalization: racism, sexism, classcism, etc. we use to describe them. Power lies in the inter-connectedness of the parts – here, people. The last two years of the Angry Cheeto have made that particularly plain, I think.

Enter Big Noodle & the Incarnation

Jason is the character version of from the mouths of babes – his point with Big Noodle is you can’t judge what you don’t know.

So, the Judge goes down to Earth.

That is what prompted me to think about The Good Place and the Incarnation.

Remember, the Incarnation is a theological assertion who God is, specifically who Jesus Christ is. The church spent a long time arguing about it (like in the hundreds of years) and they did because how do you define God? In the world of The Good Place, where we’re dealing with philosophy and not Christian theology, that question is analogous to how to live an ethical life? because who God is – in the Judeo-Christian tradition – is the starting place for what the meaning of human life is.

(Here I’m going to delve into a little Christian theology, but I PROMISE I have a reason.)

Did God create Jesus in the same way God created trees and elephants and the stars? Was Jesus the highest created being of God? A sort-of demi-god? A movement called Arianism argued this, but in the long run it was rejected because it didn’t fit with the Bible. There were a lot of opinions and theories – I’m skimming over A LOT, but in the end the church basically punted.

The Good Place took Michael through a conversion-like storyline in Season 2 when he became a demon who cares for others – his humans & Janet. Since then he has pursued the question of how behind the points system. He knows it shouldn’t have been possible for his humans to get better after they died, which undermines the whole argument for an earth-bound points system. But they did. If that is true, then the system itself is not the right answer to how to live an ethical life?

Remember: You cannot judge what you do now know.

At the Council of Chalcedon (451), it was decided to define God’s nature by what we know God is rather than what we know God is not. It’s called the Chalcedon formula, and it begins with we confess. In Christian tradition, confession is a different kind of knowing; it is rational, but it is also embodied. One can only confess what one knows because it has be proven to be true in one’s own life. It’s not about having the right answers, but saying - to me this is true.

The formula states that Jesus is God and Jesus is human, two natures without confusion, and how that exists we don’t entirely understand. It is a union of the human and divine that is not a blending of the two to make one, like the combination of two primary colors to create a new one. Jesus’ birth, life, and death is not somehow less human because of his divinity, but what comes next – the whole rising from the dead thing – definitely is divine. Even writing that sentence makes me itch a little because the Incarnation is an assertion that you can’t divide Christ’s biography into part 1: human, part 2: divine. Rather, the body of Christ – the very nature of who he was, is, and will be – is both human and divine.

The Power of Both/And

Think about this: what confirmation do we have there is a Good Place?

The only characters we’ve seen that come from there are the not-people from The Book of Dougs. Were they angels? Anti-demons? I don’t think we’ve been given a definition. Why should we trust they are what we’re told they are the first go-round? We already know characters are not always who we’re told they are. Further, the judge doesn’t reside in the Good Place. The accountants don’t. We have a door to the Good Place that only non-humans can pass through. Okay, but have we seen anyone pass through it? Assuming there is a Good Place assumes that all the other kinds of characters exist to be part of the machinery that is the human after-life. Demons torture. The judge judges. The accountants tally. Janets help.

You’ve got a system of interconnected parts: humans, demons, Janets, needlenoggles, a judge, accountants, etc., and you’ve got this points system in which they all play some part. What Schur & co. have quietly been doing with Team Cockroach is showing how these different types of beings are all changing: Janet falling in love, Michael’s conversion to caring for others, and the humans changing after they died. None of these things are supposed to be happening in that system.

I wonder if Schur & co. are playing another sleight of hand in their story telling akin to the Season 1 reveal. What if the world of The Good Place isn’t either you belong (not just humans either, but all kinds of creatures) to the GOOD PLACE or the BAD PLACE. What if - instead - they are making an argument that how to live an ethical life is not about getting the answer to the question, but about seeing the world (here the story-world of The Good Place) in new, transformative ways.

In that REI training, the facilitators asked everyone if you were proud to be an American. This was the beginning of the training. It was one of those questions that you don’t know the right answer to, but you do know what the wrong answers might be. No one said anything. The trainers started listing things they like about living in America: public education, running water, our national parks, etc., and then they listed things they didn’t like: history of slavery, the Flint water crisis, etc. They said for the work we were going to be doing in our training they wanted us to resist language of either/or – you are either a racist or you are not. You either love America or you don’t. Rather, they said, embrace the power in both/and language. You can both love the systems in which you live and work, and you can recognize their brokenness, pain, and hurt. You can be both angry at and thankful for your community. That, they said, is how we transform ourselves and our communities.

The both/and shows up in the Incarnation too – it is a theological assertion that Jesus was BOTH human AND divine. Jesus’ very body rejects that the laws of nature are either/or. Either them or me. Either good or bad. Either/or is a way of seeing the world that is human – we do it as naturally as breathing - but it is not the only way to see. There are more humane ways to exist.

I don’t know what story Schur & co. are telling, but I struggle to see where they are going to land if there is a Good Place without turning the story into a confession of a particular ethical or religious system. Because if there is a Good Place you’ve created an either/or world that needs a system for how it works.

Rather, they’ve spent a lot of narrative time doing exactly what the church did when they tried to define God – a lot of guesses that tell you want God is not, but don’t clarify what God is. Michael & co. know that Doug Forcett didn’t get enough points despite his ascetic-like life. They know that demons and humans and Janets can change in ways they are not supposed to be able to. They know that they love and care about each other. They know what they don’t know.

It is counter-intutive, but the best way to communicate big, complex ideas is in concrete, small language. It’s language that is incarnated. The Good Place is a half-hour sitcom about philosophy, and it does that by telling small, incarnated stories. You’ve got 4 humans and they died. What happens next?

But you also have a demon and a Janet. You have a system that appears to not be working. You have two places – good and bad – but actually you don’t. So already that either/or dichotomy is breaking down. There’s the Medium Place and despite the room temperature beer and medium snacks, I wonder if the fundamental geography of the show is a red herring. What if the demons and Janets and all the other kinds of beings are just as caught up in a system of either/or that is patently false? Without a Good Place, the geography of the world isn’t good or bad. It just is. Kind of like our own world. It’s something in between, both joyous and painful. What if the story we’re being told is about how these particular characters – Team Cockroach - challenge and upend a false ethical system in which all creatures in the story are caught?

How to live an ethical life? is a big question that is the wrong question. It posits an either/or world. Human life can be reduced to that, but it is always a reduction based on a lie. We are capable of choosing to see life’s geography - its systems, quandaries, and mysteries - through both/and language. The Christian theology of the Incarnation reminds me that not having all the answers is not only okay, but natural. Life does not occur by knowing the rules and then following them or not. Good living is like good language. It is concrete, small, and embodied. Somehow, it also touches on things bigger than ourselves like love and friendship and the ability to not only change - but transform.

Why would a fictional after-life be any different?

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

[RvB 17.11] Stagnation

FIRST Spoilers

In isolation, Carolina’s Labyrinth scene was not out of character or inconsistent or objectively bad; however, cumulatively it is emblematic of the stagnation in Carolina’s writing since season 13. It undeniably resonates with viewers—but I deeply dislike what it represents and I’m going to talk about why.

So to begin, and to try and give this episode a fair shake, here’s what was good about Carolina in the Labyrinth.

Jen Brown kills it as always. It is no mystery that this scene resonates with people. There is a lot of emotion in it and Jen is a fantastic voice actor who always digs deep and does the best possible work with what she is given. Better than what she is given, in many cases.

Carolina’s self-hatred is, I think, evident in her character as far back as season 10 if you look at all beneath the surface level. I’ve said before that her actions make a lot more sense when viewed through that lens than if you look at her as simply competitive, and at this point I don’t think that’s a particularly radical statement. That self-loathing is given a particularly raw and painful manifestation here.

Carolina’s encounter is also the most on-the-nose representation of what the Labyrinth actually does: it seizes upon a person’s most negative emotions and reflects them again and again, further distorting them each time, until its victim succumbs to despair. The explicit, stated function of the Labyrinth is to drive its victims to suicide, which is dark even for this show. But given that function, it makes sense that the Labyrinth would seize upon the root of Carolina’s most self-destructive impulses.

I would also like to propose a theory that probably wasn’t authorial intent but which I think makes this whole thing read… if not well, at least better. It is already obvious to fans of Carolina that the Labyrinth’s representation of Freelancer Carolina isn’t truly her, and does not accurately represent what she was like in Freelancer. Others have said as much. But I would argue that “present” Carolina isn’t truly herself here either, because she both is not how past Carolina describes her, and says things about her past self that are untrue. Neither of them are real. The real Carolina is an observer in this scene, as we are, and the Labyrinth is subjecting her to two distorted versions of herself, both of them speaking lies.

Like I said, this probably wasn’t the intent, but it’s the only way this scene even begins to work.

Which is a pretty good segue into how it doesn’t.

“I feel so much rage when I look at you,” Carolina says to her past self. “You know that? You prioritize yourself over everything. You’re going to get people killed. Heck, you’re going to kill people. And they won’t always deserve it. Dad won’t love you more if you keep winning. He can’t. He died when Mom died. And you’ll bury him. Your competitive streak stops. I’m demanding it.”

“Oh,” says past Carolina, “you’re done? Okay. You got pretty talkative! No need for the lecture. I can read your whole shitty life from your whiny tone of voice.”

“Oh, you think you’re so—”

“Directionless? Scared? No. No, actually I—” Past Carolina laughs viciously. “I feel great. Weird to hear all that from you, though. Let me unpack this. You’ve now tasted defeat, I’m assuming, and you were—aw, sad? For a while?” Her tone grows taunting. “And you want people around as crutches in case you trip again. When have I ever—think about it!—ever allied with someone I didn’t need? A friend in a high place. A bolt hole. A wing man. To forget how to utilize people is to forget yourself. Forget me. And frankly, that’d be damning enough, but you went further. Carolina, you stripped away what comes without thought. What’s instinctual. Your passion. What greater betrayal is there? You’re not you anymore.”

So let’s unpack this. First of all, how much of what the two Carolinas say is true?

It’s worth noting that it’s present Carolina who immediately goes on the offensive here, spitting venom at the image of her past self before that image has even spoken. And the things she says… “You’re going to get people killed. You’re going to kill people.”

So what is she talking about? Who did Carolina get killed by being competitive? Who did she kill?

If she’s talking about enemy targets that weren’t who she believed they were… I mean, yeah, they didn’t deserve it, but Carolina was acting as a soldier under orders and her being less competitive wouldn’t make those any less her orders.

Is she talking about the other Freelancers? Because… Carolina didn’t get them killed. North, South, York, Wyoming, Florida—none of them were killed by or because of Carolina’s competitiveness. The only one you could really ascribe to her actions is Maine, and there is a case to be made that Carolina gave up Sigma as much to prove she didn’t need an AI as to help Maine after his injury—but that act was based on such incomplete knowledge that to call it a direct result of Carolina’s competitiveness is a stretch. Furthermore, this argument always seems to ignore the fact that if Maine hadn’t gotten Sigma, someone else would have, and while we don’t know how Sigma might have behaved with a different host, it’s hard to imagine it ending without casualties regardless.

Are we talking about Biff? Because… we’ve been over this, but Carolina didn’t kill Biff, and Biff also didn’t die because Carolina was competitive. Biff’s death was an accident; even Tex, who threw the flagpole Carolina deflected, wasn’t intentionally aiming at Biff, though it does seem like she (or someone else inside that helmet, more likely) must have realized she was throwing it with lethal force. Had Carolina been less determined to win that particular match, there’s no reason to assume Tex (and Omega) would’ve dialed back their own aggression.

We also have evidence from other bits of canon that sim trooper deaths during training exercises were disturbingly common within Project Freelancer—a fact not one of the agents, not even Good Guy Do the Right Thing York, are ever shown objecting to.

Let’s look at what past!Carolina says about herself.

“When have I ever—think about it!—ever allied with someone I didn’t need?”

CT.

CT.

You know, that person everyone forgets about when they’re trying to make a case for Carolina being purely self-serving.

I wrote about this one a long time, ago, but for a refresher: the first time we ever see Carolina question the Director’s orders is when he says that CT is an “acceptable loss.” Carolina embarks on that mission with full intent to disregard that order and try to bring CT in alive, despite that fact that doing so will be far more difficult and offers her no personal gain whatsoever and in fact results in her failing the mission. And while Carolina’s motives in the briefing with the Director may be subtle, her intent on the mission itself is not. The first thing she does upon catching up to Tex is to remind her that they only need the armor. And when she tries to pull Tex back from the killing blow, she explicitly, verbally, objects to Tex killing CT, and even knowing that they have failed the mission and that she will take the blame, Carolina still chastises Tex for what she’s done. This is not just subtext. This is text.

And this is not the only instance of Carolina caring about her teammates. The haste with which she calls for medics when York is injured in training, the offer on the Sarcophagus mission to come to Team B’s aid instead of going after their objective, the “No!” she screams out when Maine gets shot—none of these are the behaviors of a person who is only out for herself at everyone else’s expense.

Freelancer Carolina is not characterized as a ruthless lone wolf who disregards her teammates except when they can benefit her. Not matter how much certain corners of the fandom prefer to read her that way.

But all right. It’s the Labyrinth. It’s a distortion. It’s not supposed to be real. It’s amplifying Carolina’s worst feelings about herself.

Still, that distortion is meant to be reflective of something real. It certainly seems to be so for other characters.

So which of the above would Carolina likely blame herself for?

Well… we actually have canon on how Carolina feels about most of the above.

In season 13, Carolina apologizes to Sharkface for what she and her team did to his squad. “I’m sorry,” she says. “We were on one side of the fight, and you were on the other. We thought we were the good guys. I’m sorry.”

Let’s unpack that for a hot second. In this short line, Carolina:

expresses genuine remorse for what she took part in.

acknowledges that she acted on false information, and by extension, that not everything was her fault.

Season 13 Carolina knew that not everything was her fault.

Let’s go back even further.

In present day season 10, Carolina has a couple of vulnerable moments in which she states her motivations outright. And a large source of that motivation for getting revenge on the Director is the suffering and death of her teammates. She tells Epsilon:

Church, the Director's still out there somewhere. And I need to find him. Not just for what he did to me, but for what he did to York, and to Wash, to Maine, the twins, to all of them.

Even earlier in season 10, when Carolina stands with Wash inside the wind power facility, she says, “Poor Maine,” expressing sorrow over what happened to her teammate. When Wash says, “Carolina, it wasn’t your fault,” she says, “But it was my AI.” There is regret here, obviously, and I think in that statement in particular is no small trace of survivor’s guilt. Carolina knows full well that had she not given Sigma to Maine, the Meta might well have been her.

But that’s not all she says. She goes on voice her suspicions that the Director, at the very least, could have been aware of the dangers of the implantations. That he acted recklessly in his “little experiments.” She places that blame where it’s due.

My point is that even as far back as season 10, Carolina is capable of identifying culpability that was not her own, without outright denying or handwaving her part in it. There’s a balance in what she says there, when she talks about Freelancer. She blames the Director for his part in it, while also feeling the weight of her own involvement.

As for Biff… we can’t know how Carolina feels about that now, because Joe decided it wasn’t important for her to be told onscreen why Temple hated her, so we didn’t get to see a reaction. But we already have a part of Carolina’s arc in which she comes to see sim troopers as people, as friends, and then as family, and based on how she speaks of other parts of her past, it’s hard to imagine she would brush it off.

But Biff’s death is also a part of this arc, and Carolina’s part in the plot of season 15 sets a precedent for how she will be treated for the rest of this storyline.

What about that final accusation: "You're not you anymore."

Is this a real fear that Carolina has in the present? I mean, it could be, but it's not something she's expressed since, arguably, season 13, and even then, Carolina's fear that letting her guard down will get everyone she loves killed doesn't really resemble past Carolina's claim that she's lost the self-serving passion that made her who she was. This doesn’t reflect an expressed fear relevant to any of Carolina’s recent conflicts.

If it reflects something real, it's news to us.

I can accept that the Labyrinth is meant to take the worst things Carolina thinks about herself in her worst and darkest moments and amplify and distort them beyond even that. I’m personally not a fan of plot devices that allow writers to kind of throw characterization at the wall and then say it was bad on purpose. But okay, given the mechanics of this plot device as it’s been established—fine. It’s supposed to be over the top.

All right.

But what I just described isn’t character development.

It’s just putting the characters through an Angst Machine. You notice we’ve had a lot of that lately?

Let’s go back to Chorus again. Let’s look at the plot device this one is ripping off the True Warrior test. Still not my favorite McGuffin ever, but at least the portal on Chorus showed the characters something real. And for multiple characters, including Carolina and also Locus, what they saw in the portal drove some kind of character growth for them.

Because it was, on some level, real.

What is there for Carolina to learn from this experience that she hasn’t learned already—in past seasons and previous arcs which both Joe and Jason seem determined to ignore?

Carolina’s character development since season 13 has stagnated.

In the same way that this arc overall has resorted to recycling character and story beats from past seasons, Carolina’s writing in particular has sunk into a rut.

Season 13 gave Carolina a meaningful mini-arc in which her past came back to haunt her in the form of Sharkface, and collided with her fears of failure and loss in the present. This drove real growth and meaningful change for Carolina as she struggled to avoid falling back to old habits while also giving her all to protect her new family.

Most importantly, season 13 had Carolina engaging with her past in a nuanced manner. Carolina in 13 was able to separate regret from responsibility. Her apology to Sharkface was not self-flagellation. It was real, meaningful, and necessary. It was not Carolina taking on the blame for things she didn’t do.

In recent seasons, however, Carolina's only real plot involvement hinges on the writers beating her guilt like a dead horse and making up new things she did wrong.

Where Sharkface and the death of his squad were drawn from events we saw happen, Biff’s death (already a retread of Sharkface) was invented and inserted into past canon, and showed us a Carolina whose aggression and callousness felt out of place even for her Freelancer self. Carolina never heard Temple’s grievances onscreen and was never allowed to respond to them, so she wasn’t allowed any growth of her own from the experience of being put through the Angst Machine with Wash.

Season 16 invents yet another sin for Carolina: keeping Wash’s memory lapses a secret, because for some reason Dr. Grey doesn’t think it’s important to keep her patients informed personally and instead puts that responsibility on their friends. This of course blows up in Carolina’s face at the worst possible moment, forcing conflict between her and Wash and driving Carolina to make yet another mistake: the decision to time travel to save Wash, the catalyst for season 17.

This season has done some pretty decent damage control in that it has repaired Carolina and Wash’s relationship. Yet it’s still not allowing Carolina to move on from Freelancer. If we had to have a plot device that amplifies negative emotions, why not use Carolina’s more recent struggles, like the way her overprotectiveness and difficulty opening up even with people she loves led to her unintentionally hurting Wash?

There were warning signs, unfortunately. Wash’s time travel to the Freelancer era showed Carolina straight up refusing to speak to him, which… really isn’t something we ever saw Carolina do to her teammates in Freelancer. But despite Wash’s sympathy to Carolina in the present, Jason seems intent on driving home the point that she was unambiguously “mean” in the past. So I guess it’s no surprise that now we get to watch her feel bad about it some more.

In season 13, Carolina called the Reds and Blues her family, and expressed that she would do whatever it took to protect them.

In season 15, Carolina said she wondered if she’d missed her one chance at a fresh start, completely ignoring the fact that she’d already had one several seasons ago.

In past seasons, Carolina’s regrets led to her growing and changing. Now, recent seasons have reduced those regrets to static traits that never change. She was mean in the past (because with few exceptions, “ambitious woman who’s good at her job” is synonymous with “bitch” in RvB), and she’s going to feel bad about it forever. That’s it. That’s her character now. Past growth is discarded and ignored. We’ll continue to hammer on her past wrongs and her regret every single season, but she’s never going to be allowed to move on.

It's bad character writing. Yes, even if the plot provides a mechanic for it.

I’ve said this before, but Joe and Jason are not writing character arcs. They are simply remixing old character beats for Feels and then resetting the characters to status quo. We’ve seen it with Grif, and the same thing is happening with Carolina.

And furthermore, it really feels like a lot of these writing decisions stem from a very shallow impression of “what the fans like.” Fans like Wash angst, so hurt Wash for no reason. Fans didn’t like it when Wash and Carolina were close, so force some conflict, and when they make up be sure to inject a line about how they’re like siblings. Fans didn’t like Tucker being torn down in favor of Grif, so that must mean fans don’t like it when we pay attention to Grif.

Fans liked it when Carolina apologized and was emotional, so that means Carolina should always be feeling bad about something, all the time, regardless of context.