#napoleonic naples

Text

Excerpt from ‘Gioacchino Murat e l’Italia meridionale’ -- presentation of the King

Sooo guys. Some time ago i got a book, ‘Gioacchino Murat e l’Italia meridionale’ which was introduced to me by @joachimnapoleon and after reading it I thought of making a post about it. Hope you will enjoy it!

So let’s get started! In the third part of the book we have a focus on the people who actually governed Naples, starting with the King and the Queen and proceeding with the ministers, describing how their personalities fitted in their roles and how they actually got their work done; this post will be about our favourite King of Naples, Joachim Murat. (the mistakes in the translation are entirely mine)

Here the original text in italian

Much has been written on Murat, but in a discordant manner. While French historical tradition appreciates the magnificent soldier and exalts his deeds on one hand, on the other hand it sees too much of him as the traitor of Napoleon and of France in 1814 and so it’s brought to judge him with excessive severity; being worth of all Espitalier and Garnier who in his recent ‘Murat roi de Naples’ uses a caricatural tone that cannot not harm the seriousness and the accuracy of the judgment. The Italian liberal tradition is in his favour instead because it mainly appreciates the man of proclama di Rimini and the man of the 1815 constitution: while in reality Murat decided about creation of it lately and reluctantly, brought there by his entourage, as the only thing that could still give a chance of realization of his ambitious dream of his kingdom's conservation and expansion. However, the concept of the state that Murat must have had – a poor concept, even if it can be called such – seems to us paternalistic and absolutistic: he wished he could say ‘l’état ce moi!’ like Louis XIV but in a generous and good-natured manner. Being said so, for us Murat is neither Napoleon’s bad copy, as the French writer judged him, nor Italy’s paladin of independence and unity, as in Manzoni’s Il proclama di Rimini.

But, since we are interested in him as the head of the Neapolitan government, where he brought his personality, we’ll try to draw this one by using mainly our unpublished sources.

AAAAAND HERE WE START GUYS!!

In them Murat is revealed to us as an enthusiastic and naive (and this is sure not a positive quality for a head of government); ambitious and vain in a somewhat childish way, impressionable and susceptible to the influences of those who surround him: be them the man from the Napoleonic court or the italian intellectuals; or even the good cossaks from Russia, who went to tell him of their enthusiastc admiration. But he’s sincere in his changeable resentment of men and of the environment in which he lives: honest if he says he loves Napoleon, even when he disobeys and detaches himself from him; sincere in trusting the allies, and then grieving of the deception that they brought him; true in sharing the feelings of italianness of some of the best in his retinue, as in the disappointment of the abandonment by the Italian patriots and his generals, who are full of encouragement and good words, but when it comes to acting they draw back and criticize him. His greatest enemy, Lord Bentick, believed him, why shouldn’t we?

Murat loves his subjects, and believes he understands them. Berthier, who loves him, has warned him that Napoleon told him “Murat gave me some services, but works to weaken their merit by not following my system. The king of Holland has lost himself by forgetting France and Frenchmen to be Dutch. The Realm of Naples will lose itself if it doesn’t follow the empire, which it is a part of”. And begs him to shut his ears to ‘perfidious’ advices, and tells, even while knowing that this will be painful for him: “Neopolitans are Neopolitans, make them French. Don’t do anything that’s not for the Emperor and for the Empire”. Murat defends his Neopolitans, and Writes to Napoleon: “May I say, this country is not well known to you” (and this was truth because Napoleon has never known or appreciated Neopolitans); “His inhabitan’s character is completely oriental, a nothing sways it, a nothing bring it to the two extremes”; and elsewhere “VM has a too bad opinion of the Neopolitans, VM believes that 12000 Englishmen could kick me out from the kingdom, I’ve known them for three years, and I esteem them more, and I don’t fear the English”. And adds with an Irony that doesn’t lack finesse: “Let’s admit that 12000 English would manage to beat all the Neopolitans. There are 25000 French ”from the occupating troops“ and then you will come here in forced marches to rescue me”.

Ooops naps, how will you answer this?

The fact is, Murat took his job as a king seriously, and “the king was not made to obey”, and even less to be subject to anyone; instead he has duties towards his subjects that are superior to the bonds like blood and gratitude. Nothing in his pure expression can be more expressive than a drawing that I saw on a paper in Naples’ Archive, drawn by the king’s hand, at the side of a note answering on the stern reprimands that came from France demanding the absolute severity in the application of the Continental Blockade: a little doll made of colored cardboard, with neither arms nor legs, filled with pebbles, which a poor Neapolitan mum put gave to her little girls so that they would have fun shaking them. Now there’s no more on the market. Was it what Napoleon wanted from him?

Murat was chivalrous, and may Guglielmo Pepe's words be the testimony; He nourished sensitivity and kindness of affections, as very intelligent daughter Luisa testifies in her Memoirs; he was not even insensitive to the suggestion of the first romantic currents, typical of his time: the relations with the Italian patriots prove it; and even the text of a song he wrote to escape the tedium in the breaks of war in Russia, poor testimony of poor vein: song that is there, between the His cards together with the music that for it composed the first squire, Carafa'.

Nor, like all truly courageous and generous, was Murat cruel, so we believe he speaks the truth when he excuses himself about the part he was said to have taken in the assassination of the Duke of Enghien: and some then wanted to see in the trial and death of Murat the coming of the true historical nemesis. He wrote - and we note it because this is of big interest that he was in bed sick when the decree of convocation of the Commission that was to judge the prince was brought to him, and to have told his wife, foreseeing the death sentence of the unfortunate man, that «he would rather be fighting, rather than signing the decree». He added that the list of commissioners was not written by him, but by the minister secretary of state; and that he learned of the sentence and of the execution only when the general commander the gendarmerie came to give him an account, as he was the governor of Paris.

We said Murat was basically naive. I bear proof of this: his behaviour at the council of the great dignitaries of the empire and of the members of Napoleon’s family, when he, repudiated Josephine, decided on a new marriage, and invited the summoned to give their advice about a choice between an Austrian archduchess, a Russian grand duchess, and a Saxon princess. There was a somewhat perfidious backstory, in which Napoleon’s brothers, hostile to Murat (Elisa and Pauline, on the other hand, had a liking for him) «because they had badly endured that a royal crown had been given to those who were not of the first branch of the family». And the emperor must have known something about the little ambush.

Murat was invited to speak immediately after the Archchancellor Combacérès who had shown himself to be unfavorable at the Austrian wedding, but with much circumspection. The king of Naples, however, spoke with conviction and warmth, and said he was in favour of marriage to a Saxon princess. Only when all were convinced of their marriage to an archduchess, did he realize that he was the only one to ignore the secret of the emperor, because Combacérès had to have an assigned part to better induce him to speak. And he also had the pleasure of grieving with his brother-in-law: When your determination was taken, why did I not know of the secret, why interrogate me, and expose me to the enmity of Austria and the Archduchess? You know that, after the marriage of Eugene, I am small partisan of the alliances of your family with the old dynasties».

Joachim had a boundless admiration and love for Napoleon. He, for his part, treated him as a good horse, which occasionally rears, but, will always remain in the subjection of the master, knowinghowtohandleit. But the emperor often lacked tact in the relations with his brother-in-law, answering long silences with some scornful praises, and harsh reproaches, which sounded like stirrups for Joachim, sensitive and shady, and that much presumed of himself, as a warrior and as a ruler. In addition, the Emperor made enormous demands, which certainly met the needs of France, but they went beyond the possibilities of the realm of Naples, which were not as large as one persisted to believe. And the king felt he could not give in to the demands because that would be against the interests of the crown, in order to preserve which he was ready to make any sacrifice: even of his attachment to France and Napoleon. About which Carducci was right to write

“onda procellosa procellous wave

di Murat che s'abbatte a una corona.” Of Murat falling to a crown.

It must be recognized that keeping that crown was a very difficult thing, even impossible for a poor politician like Joachim. Everything conspired against it: the lability of the diplomats of the coalition who acted with him as cat playing with mouse and ended up killing him without any static; the Neapolitan generals, demanding, presumptuous, unruly, who let themselves be lured by England. The Italian people’s inertia, for whose cause he had finally voted, believing that, with its independence, it would achieve its own independence, and with the unity of Italy, an enlargement of its dominion. It seemed to conspire against Murat even the exceptional temperament of the opponent, who seemed tailor-made to win the game last: that Ferdinand IV who, apart from the divine right and the solidarity of the other Bourbons, against the Joachim’s restlessness used his sly policy of doing nothing, only not to give in an inch, as well as waiting for the events to ripen.

Perhaps, in her great common sense, Madame Mère was right when she said that «Napoleon had been wrong in making a king; but Napoleon was not infallible, he was not the son of Mary, he was the son of Letizia».

I hope you enjoyed this and i thank @tairin for having been a real sweetheart in accepting to beta this and @joachimnapoleon for having talked to me about this great book... it took me a while to finish it but it was really a great reading!! I will probably try to translate some other passages so stay tuned... i suppose?

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lady Hamilton and Horatio Nelson, Naples by Frank Moss Bennett

#lady hamilton#horatio nelson#art#frank moss bennett#naples#italy#europe#european#napoleonic#history#great britain#britain#england#royal navy#napoleonic wars#architecture#ships#mediterranean

246 notes

·

View notes

Text

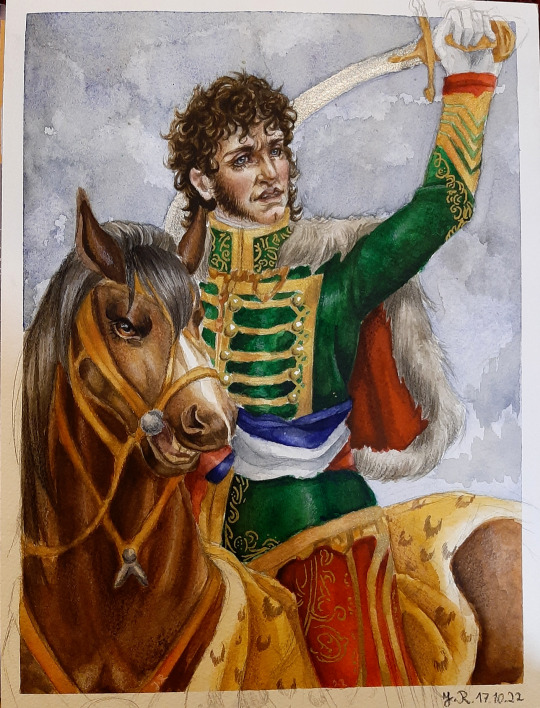

And here is the finished painting of murat and three of his children. Maybe im going to post some Detail shots too

#napoleonic era#napoleonic wars#napoleon#joachim murat#marshal murat#murat#king of naples#napoleon's marshals#marshalate#watercolor art#history art#artists on tumblr#original art

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

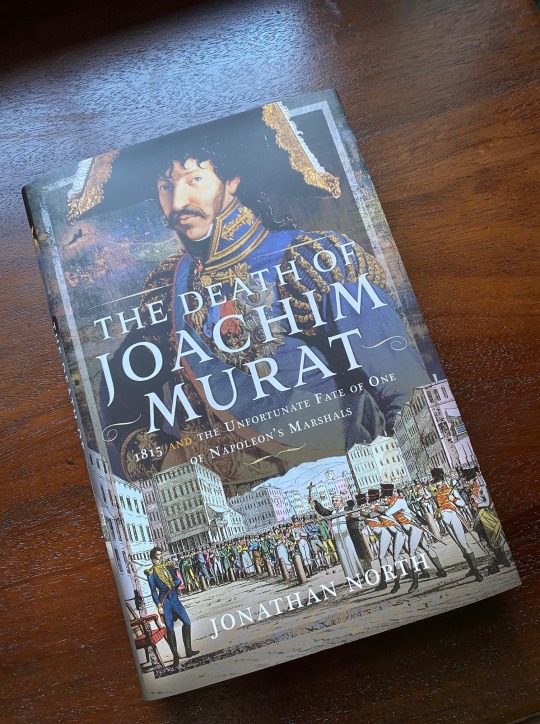

Just released:

I had the privilege of reading the first draft of this, so I’m really looking forward to the final, polished version. Jonathan North has utilized archival sources from both France and Naples, including the diary of one of Murat’s aides who accompanied him on his final journey, to put together the most thorough examination of the events leading up to Murat’s death ever published.

The book is available now in the UK (see the post on Jonathan’s page linked below for where you can buy it from) and should be available in the US next month (Amazon shows December 30).

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Naples a l'époque de Napoléon : Rebell et la lumières du golfe

Naples in the time of Napoleon. Rebell and the light of the Gulf

Naples in the time of Napoleon. Rebell and the light of the Gulf restores the atmosphere and image of the city in the years from 1808 to 1815, when Joachim Murat and his consort Caroline Bonaparte, the youngest of Napoleon's three sisters, were the much-loved rulers of Naples. This was a period of progress and renewed splendour for the kingdom, marked by extraordinary social, economic and urban transformations and particular attention towards the territory. The culture of the Murats and their modern taste acquired in Paris gave the arts a considerable boost, dividing their time between the official royal palaces of Naples and Caserta and their favourite private residence in Portici.

Patrons of the great portrait painters, Joachim and especially Caroline showed a particular sensitivity for veduta and landscape painting, calling French masters in the genre to their court, Special protection was reserved for the Viennese artist Joseph Rebell, who, along with other specialists in veduta painting, features prominently in this exhibition. Rebell spent several periods of time in Italy between 1812 and 1824, particularly in Naples.

Views of the city, its gulf and magnificent surroundings were his favourite subjects, even after leaving Naples in 1815, fuelling in Europe the myth of the unique nature of this enchanted land celebrated by the painters of the Grand Tour. His training and success are evoked and set against the backdrop of the cosmopolitan Neapolitan scene between the end of the 18th century and the second decade of the 19th century, marked by the presence of numerous travellers and landscape painters who profoundly renewed the vision of reality.

The Murat family itself is also a protagonist of the exhibition, with the presence of numerous portraits, paintings and sculptures bearing witness to the important role it played at that time.

The works are on loan from prestigious organisations, including the Belvedere of Vienna, partner of the exhibition, other major Austrian museum, such as the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts and the Austrian National Library, and French museums such as the Château of Fontainebleau and Versailles.

The exhibition is curated by Sabine Grabner, Luisa Martorelli, Fernando Mazzocca and Gennaro Toscano, with the collaboration of the Institut français in Naples.

Dates: November 23 2023 - April 7 2024

(Gallerie d’Italia)

#Gallerie d’Italia#napoleonic era#napoleonic#Caroline#Murat#Caroline Bonaparte#Joachim Murat#napoleon bonaparte#first french empire#napoleon#french empire#france#19th century#Naples#Napoli#Italy#Joseph Rebell#Rebell#Neapolitan#Naples a l'époque de Napoléon : Rebell et la lumières du golfe#Naples in the time of Napoleon#Naples in the time of Napoleon. Rebell and the light of the Gulf#Rebell and the light of the Gulf#art#Rebell et la lumières du golfe#19th century art#1800s art#veduta

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

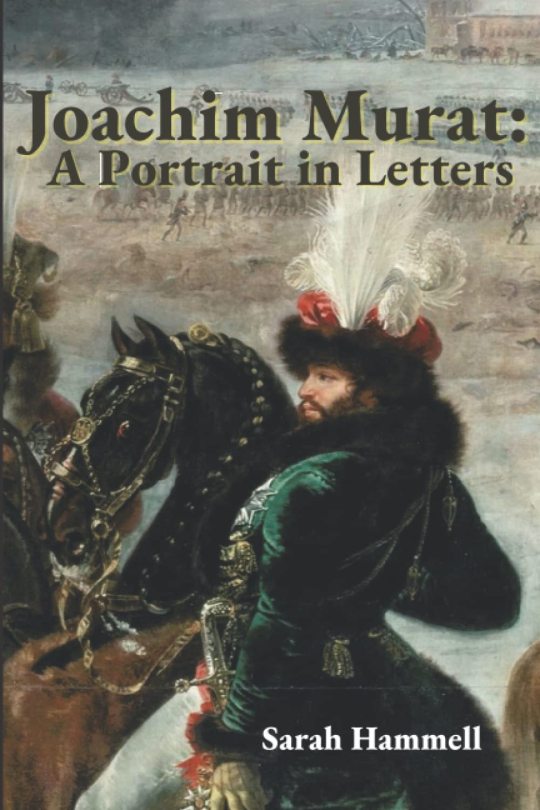

*Book Report!*

I'd just like to start off by saying that one of the first people in the Napoleonic community that I found on here, was @joachimnapoleon , the author of this book! I've learned so much from her blog, specifically about Joachim Murat, but also about all our other beloved Napoleonic characters. Murat is definitely a big character in the story of Napoleon. I'll admit I didn't know much about him, other than the basics that all the Napoleon biographies listed. Dashing cavalry man that married Napoleon's sister, Caroline, and eventually betrayed him. Based on that, I didn't particularly like him, as I tend to see things from Napoleon's point of view. This book changed my outlook and I saw, through Murat's own words, that he was just looking out for his family and his kingdom. It was so much deeper than just "betraying" Napoleon. I would not have liked to be in his situation! It was sweet to see the letters to his family, specifically to his daughter, Letitia. I think my favorite part was in the earlier letters to his parents though, when he was repeatedly asking for his baptismal certificate. It reminded me of myself when I moved out from my parents house and I had to keep asking my mom for my birth certificate so I could get my license changed. It's also interesting to see how people wrote to each other back then, so dramatically if they didn't get a reply and constantly referencing their health. I very much enjoyed the introduction as well, where Sarah Hammell explains how she got into Napoleonic history and Murat in particular. My only complaint about this book, is some sort of editing error I assume, where sometimes the footnote numbers are small and sometimes the same size as the normal font. Just a small inconsistency. I hope that this book opens the door and inspires more authors to write books on Murat in English, something that we are very lacking.

#joachim murat: a potrait in letters#sarah hammell#book report#joachim murat#marshal murat#king of Naples#napoleonic#napoleonic marshals

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

Still looking for a list of people decorated with Murat's (or Joseph's) order of the Two Sicilies. I've found several websites listing names, but no mention of either Eugène or Bessières. Considering that Napoleon claimed Murat was handing out that order to whoever he ran into, I'm starting to suspect they really never received it.

Interestingly, Marescalchi, the minister of foreign affairs of the Kingdom of Italy - technically Eugène's subordinate - had received it. But as Marescalchi resided in Paris, close to Napoleon, Eugène in Milan at least had no reason to feel bad about it, in case he would have. Which I doubt anyway.

If Bessières really never received Murat's treasured decoration, this could mean two things: Either the two had gotten estranged at some point before 1809, as Bessières' close friendship with Eugène made me suspect. Or - possibly even more likely - Napoleon had at some point stopped the distribution of Sicilian decorations before Bessières had gotten his. 😁

As there was a small annual pension involved, the order might actually have come in handy for Bessières who was always in debt?

#napoleon's marshals#and kings#and family#joachim murat#jean baptiste bessières#eugene de beauharnais#kingdom of naples#order of the two sicilies

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

#beauty#art#love#self love#cinematography#movie#cinema#film#cinephile#sopialoren#italia#sicilia#napoli#napoleon#naples

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

I found this picture of Murat’s execution on Pinterest and I don’t know what exactly it is but this depiction just hurts… I guess it’s the fact that he looks slimmer and you can feel the realisation that he f-ed up big time. He looks so miserable, there is nothing heroic about this. This execution feels as unnecessary as it was.

I want to put him on a ship and make sure that he finds his way to his kids and wife. :(

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vivien Leigh and Laurence Olivier as Lady Hamilton and Horatio Nelson in That Hamilton Woman 1941 ⛲️

#old hollywood#beauty#romantic drama#historical drama#1940s cinema#vivien leigh#laurence olivier#alan mowbray#1700s fashion#emma hamilton#horatio nelson#napoleonic wars#naples

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Horatio Nelson: Adm. Villeneuve’s Death (part 45)

Horatio Nelson: Adm. Villeneuve’s Death (part 45)

Admiral Villeneuve was in Rennes, awaiting instructions from to the Minister of Marine, when he was found dead in his room at the Hôtel de la Patrie, with six stab wounds in his left lung and one in his heart inflicted with an ordinary table-knife with a black handle.

They found a farewell letter to his wife and, next to it, some packets of money, each marked with the name of the recipient (his…

View On WordPress

#assassination#death#fake#grave#knife#Lady Hamilton#letter#name#Naples#Napoleon#Nelson#Queen#suicide#temple#Villeneuve

0 notes

Text

Corinne at Cape Misenum by François Gérard

Showing the title character from Corinne, an 1808 novel by Madame de Stael, at Cape Miseno.

#corinne#cape misenum#françois gérard#art#madame de stael#madame de staël#europe#european#cape miseno#napoleonic#germaine de staël#history#painting#france#french#gulf of naples#campania#southern italy#italy#vesuvius#mount vesuvius#landscape

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

#artwork#illustration#aquarelle#painting#joachim murat#murat#napoleonic era#napoleonic wars#king of naples#myart#watercolor art

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Part two of Napoleon's letters to Murat (3 November - 15 December 1808). This is really where Napoleon starts coming down hard on Murat and criticizing and/or ridiculing practically everything he does. (I had to laugh at the multiple complaints about Murat's doling out of the Order of the Two Sicilies, for, um, reasons.)

#just let him give away the shiny things Napoleon what is wrong with you#Napoleon#Napoleon Bonaparte#Joachim Murat#letters#history#1808#Naples#Order of the Two Sicilies

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Portrait of Caroline Bonaparte Murat, Queen of Naples, c. 1812

Attributed to Étienne-Charles Leguay

The Bay of Naples and Mount Vesuvius can be seen in the background of this portrait of Napoleon’s sister.

(Philadelphia Museum of Art)

#she really loved the Pompeii stuff#Caroline#Caroline Bonaparte Murat#Caroline Bonaparte#Napoelon’s sisters#Napoleon’s family#napoleonic era#napoleonic#Naples#Napoli#Vesuvius#Pompeii#miniature#veils#veil#miniatures#miniature portrait#first french empire#19th century#1800s#empire style#empire#Murat#napoleon#french empire#Italy#history#France#Bonaparte

34 notes

·

View notes

Note

What the tea on Maria Carolina? You said in one of your posts: “Maria Carolina truthers know she's the most interesting daughter and the one there should be hundreds of books and movies about, but the general audiences haven't seen the light yet.” I’m intrigued

Hi! Sorry it took me so long; I was reading a book about the Bourbons in Naples and I wanted to finish it to be able to give a more complete answer… but it ended up taking me MONTHS to be done with it.

This answer was a bit difficult to put together because Maria Carolina’s life was very eventful, so I’ll just mention some facts about her life, focusing more on the Napoleonic era and Napoleon specifically because I think you’ll be more interested in that. Also please feel free to correct me If I got something wrong, since this is a time period I’ve only started to learn about recently. So what was the tea?

Born in 1752 Maria Carolina was the thirteenth child of Empress Maria Theresia and Franz I, Holy Roman Emperor. As part of her mother’s policies of rapprochement to the Bourbons, she and her siblings were engaged to different members of the houses of Spain, France, Parma and Naples. Maria Carolina was promised to the Dauphin of France, but when her elder sister, promised to the King of Naples, died of smallpox, she took her place.

Ferdinando of Naples had been a child king, and he remained so for the rest of his life. His only diversions were hunting and pulling pranks on his courtiers, and he had a terrible reputation across the courts of Europe as an uneducated, bad mannered, spoiled man, kept in ignorance by his Ministers so they could control him. Everyone pitied the young Archduchess’ fate, her mother Maria Theresia wrote around the time of Maria Carolina’s wedding that she “trembled in fear for her”. But duty came first, and so she went to Naples, aged only sixteen.

Maria Carolina did not had it easy at first. She was terribly homesick and found herself in a court that could not have been more different to the one she grew up in. When her sister Maria Antonia married the Dauphin of France, she wrote to her former aya:

When I imagine that her fate will perhaps be the same as mine, I want to write volumes to her on the subject, and I very much hope that she has someone like me [to advise her] at the beginning. If not, to be frank, she may succumb to despair. One suffers real martyrdom, which is all the greater because one must pretend outwardly to be happy. I know what it is like, and I pity those who have yet to face it… I would rather die than endure again what I went through at the beginning. Now all is well, which is why I can say—and this is no exaggeration—that if my faith had not told me, ‘Set your mind on God,’ I would have killed myself.

Unsurprisingly Maria Carolina didn’t fall head over heels for her husband, but she did convince him that she had, and eventually won his affection. After she bore a son in 1775 she earned a seat in the State Council (as her marriage contract established), and from that point onward she became an active player in Neapolitan politics. One of her firsts moves was to remove the Secretary of State, Marchese Tanucci, who had been Regent during her husband’s minority and still held a huge influence over him.

After Tanucci’s dismissal she became the person with the most influence over Ferdinando, and she pretty much had him wrapped around her finger for most of their marriage, acting as the de facto ruler of Naples. Every decision the king took was only after consulting his wife, and she often had the final say. However, this didn’t meant Maria Carolina held absolute power: Ferdinando was still a very unpredictable person, and as soon as his wife was out of his favor he stopped listening to her.

Maria Carolina was enthusiastic about the ideas of the Enlightenment, as many other royals were at first, and even protected and encouraged the Masons in Naples during her early years as queen. But she was still the consort of an absolute monarch that believed they were chosen by God to rule, so it shouldn’t come as a surprise that she was horrified by the French Revolution and fervently opposed it. If it were for her, she would've declared war on France immediately, but this was not possible. On the execution of her brother-in-law Louis XVI she wrote:

Knowing your upright mind, I can imagine your emotion on hearing of the appalling crime perpetrated against the unfortunate King of France in all solemnity, tranquillity and illegality (…) He was the head of our family, our kinsman, cousin and brother-in-law. What an atrocious example! What an execrable nation! I know nothing about the other wretched victims in the Temple. If sorrow does not kill them, other horrors may be expected from this horde of assassins. I hope that the ashes of this good Prince, of this too good Prince who has suffered shame and infamy for four years culminating in execution, will implore a striking and visible vengeance from divine Justice, and that on this account the Powers of Europe will have no more than a single united will, since it is a matter in which they are all involved.

She was growing increasingly anxious about her sister, Queen Marie Antoinette, and her hatred for France became an obsession:

I hear horrible details from that infernal Paris. At every moment, at every noise and cry, every time they enter her room, my unfortunate sister kneels, prays and prepares for death. The inhuman brutes that surround her amuse themselves in this manner: day and night they bellow on purpose to terrorize her and make her fear death a thousand times. Death is what one may wish for the poor soul, and it is what I pray God to send her that she may cease to suffer. . . . I should like this infamous nation to be cut to pieces, annihilated, dishonoured, reduced to nothing for at least fifty years. I hope that divine chastisement will fall visibly on France, destroyed by the glorious arms of Austria.

At this point she had lost all hopes of her being rescued, and wished her “a natural death as the best thing that could happen to her”. But even though she had been waiting for it, the news of Marie Antoinette’s execution still shocked her. She wept and prayed with her children for “her wretched sister”.

Naples fell into a social crisis during these years, paranoia, fear and suspicion of the revolution in every corner. There was an active persecution of everyone thought to be a “jacobin”, arrests, trials and executions. But the country couldn’t wage war against France, and eventually they had to sign a peace treaty, which the Queen disapproved: “I am not and never shall be on good terms with the French… I shall always regard them as the murderers of my sister and the royal family”.

It was also during this time that the star of a certain Bonaparte started to rise, and Maria Carolina followed his career with interest and admiration. Before the treaty of Campo Fornio in October 17, 1797, she wrote about Napoleon:

I admire him, and my sole regret is that he serves so detestable cause. I should like the fall of the Republic, but the preservation of Bonaparte. For he is really a great man; and when one can only see ministries and sovereigns with petty and narrow views, one is all the more pleased and astonished to watch such a man rise and increase in power, while deploring that his grandeur is attached to so infernal a cause. This may seem strange to you. But while I loathe his operations, I admire the man. I hope that his plans will miscarry and his enterprises fail; at the same time I wish for his personal happiness and glory so long as it is not at our expense… If he dies they should reduce him to powder and give a dose of it to each ruling sovereign, and two to each of their ministers, then things would go better.

Soon she would have less nicer things to say about Naps, but she never lost that original admiration and astonishment.

In 1798 Ferdinando, encouraged by his wife and the British, led a expedition in December to try to expel the French from Rome. Not only the Neapolitan troops weren’t prepared to defeat the French Army, they were also technically still at peace with France, so this wasn’t a good move at all, and only two days after entering Rome Ferdinando had to retreat. Expectedly, Napoleon’s reaction to such a break of peace was marching over Naples. The royal family had to flee to Sicily, a tragic journey in which Maria Carolina’s six-years-old son Alberto died after a series of convulsions.

This ask is already too long to unpack all the political mess around the short-lived Parthenopean Republic, so to summ it up: it didn’t work out, and by 1799 the Bourbons were back in power. They were unforgiving of the republicans: during the following months there were thousands of arrest and hundreds of executions and deportations. Maria Carolina felt no mercy for them: “Death for the ringleaders, deportation for the rest... Our country must be purged of this infection”.

The Queen returned to Naples in August 1802, after more than three years of absence. She had never been a liked queen, but her unpopularity reached a new low since she was blamed for all the misfortunes of the last years. Having lost the influence she had on her husband, who held her responsible for the Rome expedition fiasco, she meddled a little less in politics now, dedicating mainly to her children and grandchildren, particularly to her unmarried daughters.

Speaking of her children, she had seventeen (!!!) but she would outlive fourteen of them. Part of her masterplan for them was to marry them all to her Habsburg nephews and nieces, and in many cases she succeeded. Just to name one exemple her eldest daughter Maria Theresa married Emperor Franz II/I of Austria. Maria Carolina’s relationship with this son-in-law ended up being a bit tense, since Franz found her mostly meddlesome and never aligned with her plans. On top of that, she was quite hurt when Franz remarried only months after her daughter’s death; after he announced his engagement she stopped adressing him as her son and resorted only to “Your Majesty” instead.

In 1804 Napoleon became Emperor, and we have a letter she wrote to Minister Gallo on this. Buckle up because whatever you imagine her reaction was, you aren’t ready for it:

It was not worth the trouble to condemn and slaughter the best of kings [Louis XVI], dishonour and revile a woman, a daughter of Maria Theresa, a holy princess [Marie Antoinette], to wallow in massacres, shootings, drownings, and kill six hundred prelates in a church, perpetrating horrors of the most barbarous ages at home and abroad, writing whole libraries on liberty, happiness, etc., and at the end of fourteen years become the abject slaves of a little Corsican whom an incredible fortune enabled to exploit all means to succeed, marrying without honour or decency the cast-off strumpet of whom the murderer Barras was surfeited, Turkish or Mohammedan in Egypt, atheist at the start, dragging the Pope after him and letting him die in prison, a devout Catholic after that, practising every deceit, shortening the lives and normal careers of sovereigns who might assert themselves, only allowing the dummies to vegetate, then atrociously, without a shadow of justice, assassinating the Duc d'Enghien, plotting himself (and he did not blush to admit it, so blinded is he by passion) a conspiracy to victimize the rulers he still feared, and on top of all these abominations he is acclaimed as Emperor: he and his race of Corsican bastards are to dominate almost half Europe, yet every thinking person is not revolted. Far from it, their egoism and weakness are such that they study how low they can prostrate themselves before the new idol… Send me word of the august Emperor’s intentions regarding Italy: whether he will deign to accept us as his slaves or will leave us in our obscurity… Tell me what the other Powers are saying. I imagine a Gloria in Excelsis Demonio will be the general refrain…

She took it pretty well right?

The future of the Bourbons of Naples once again seemed bleak, and this time Maria Carolina resorted to directly appealing to Napoleon. This was the beginning of a very passive-agressive epistolary relationship, both of them trying to be civil but still borderline insulting each other. I honestly find this funny, because you have Maria Carolina swearing to Napoleon that she had nothing against him or France and then she would write this to one of her ministers: “You will never imagine the rage and despair which the extremely insolent screed of the scoundrelly but too lucky Corsican has caused me.”

Despite the passive-agressiveness, when Napoleon was looking for a princess bride for his stepson Eugène he actually considered one of Maria Carolina’s daughters, Maria Amelia, as a possible candidate. But when the Minister of Foreign Affairs Gallo told Maria Carolina of Napoleon’s inquiries about her daughter she was so utterly horrified at the idea of marrying into the Corsican’s family that the project was immediately dropped (eventually Maria Amelia would go on to marry the Duke of Orléans, later King Louis Philippe I, and became the last queen of the French).

After Austerlitz Napoleon pretty much had all of Europe eating from his hand, and the Neapolitan sovereigns felt abandoned by every other power. Maria Carolina tried one last futil attempt to plead to Napoleon, but he had already decided to take Naples. The King was the first to Sicily flee this time, the Queen stayed behind and tried to organize a resistance, but eventually she realized there was nothing they could and also fled with her daughters. Before sailing she wrote to her daughter Empress Maria Theresa of Austria: “I fear we shall never see Naples again”. She was right.

The royal couple spent their second exile the same way they spent their first: Ferdinando living his best life enjoying the freedom he had in Sicily and Maria Carolina being utterly miserable. Her health worsened and she often was in pain, but recovering Naples from the Bonapartes became her obsession. She was the leading force behind every attempt to get the kingdom back, but soon she started to crash with their only allies left, the British. They wanted to keep the Bourbons in Sicily, getting back Naples was not a priority for them.

So remember Maria Carolina’s her reaction when Napoleon suggested to marry her daughter to Eugène? Well she didn’t took her granddaughter’s marriage to Napoleon himself any better: “Only this calamity was held in reserve. To become the Devil’s grandmother”.

But at the end, the final boss in Maria Carolina’s life wasn’t Napoleon, but the British. The Queen was too meddlesome and hindered their plans, and made a personal enemy of the British representative Lord Bentinck. Maria Carolina was accused of conspiring and being a threat to Sicily, and eventually the King was forced by the British to send her away. Exiled in exile, having nowhere else to go, she returned to Vienna in an eight-months-journey. While her son-in-law had no desire to receive her, he couldn’t turned her away either. She got in a better mood once she was once back at her childhood home, spending time with her Austrian grandchildren. It was there that she heard of the French defeats and Napoleon’s abdication.

Even though Maria Carolina made her hatred of Napoleon her personality for fifteen years she felt sympathetic towards him after he was defeated, reproached Marie Louise for not going to Elba with her husband, and told her that if she wasn’t allowed to reunite with him she should tie her bed-sheets to her window and escape, because marriage was for life. She also showed a lot of interest in her great-grandson, little Napoleon II, whom she called “mon petit monsieur”; in a letter to Marie Louise she described him as “very charming, quiet and well behaved” and told her that “may God give you in him every consolation a mother can receive.”

Maria Carolina was not to see the Bourbons restored in Naples. She died of a stroke in September 8, 1814, aged sixty-two-years old. At the time of her death Murat was still King of Naples, and the allies were happy to leave Ferdinando in Sicily. She was buried in the Capuchin Crypt, her death being only a small incident in the Congress of Vienna’s dance.

Overall, I personally find Maria Carolina the most fascinating because of everything she represented: she was a healthy daughter of the ancien régime that saw how the world as she knew it crumbled down and changed forever, to the point that by the time of her death she, the last surviving child of Maria Theresia, was a living relique (and she wasn’t even that old - a testament of how fast everything had changed). And she didn't got there sitting by idly: she fought against this new world every step of the way, made it out alive, but lost the battle still. And I don't know about you, but to me this is just a more interesting story to tell than Unoriginal Marie Antoinette Adaptation Number 7383.

Sources:

Acton, Harold (1998). The Bourbons of Naples (1734-1825)

Castelot, André (1974). King of Rome; a biography of Napoleon's tragic son

Stollberg-Rilinger, Barbara (2020). Maria Theresa: The Habsburg Empress in her Time

#sorry if this answer is too long and messy - i been putting it together little by little for the past month#but this is only the top of the iceberg i left out so many things#queen maria carolina of naples#ferdinando i of the two sicilies#house of habsburg#house of bourbon-two sicilies#napoleon i#cw suicide mention#asks

52 notes

·

View notes