#marmion

Text

#knights#medieval#combat#duel#yield#art#armour#knight#marmion#sir walter scott#walter scott#england#scotland#britain#illustration#middle ages#jousting tournament#tournament#duelling#history

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

A note for readers of Wildfell Weekly (as well as others): the book that Gilbert buys for Helen Graham, Marmion by Sir Walter Scott, appears to have been extremely popular in its time; it is mentioned by characters in several other famous novels of the 1800s.

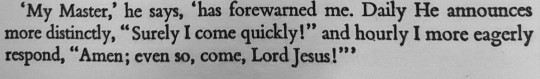

St. John Rivers buys it for Jane in Jane Eyre:

“I have brought you a book for evening solace,” and he laid on the table a new publication—a poem: one of those genuine productions so often vouchsafed to the fortunate public of those days—the golden age of modern literature. Alas! the readers of our era are less favoured.”

…While I was eagerly glancing at the bright pages of “Marmion” (for “Marmion” it was)…

…I had closed my shutter, laid a mat to the door to prevent the snow from blowing in under it, trimmed my fire, and after sitting nearly an hour on the hearth listening to the muffled fury of the tempest, I lit a candle, took down “Marmion,” and beginning—

“Day set on Norham’s castled steep,

And Tweed’s fair river broad and deep,

And Cheviot’s mountains lone;

The massive towers, the donjon keep,

The flanking walls that round them sweep,

In yellow lustre shone”—

I soon forgot storm in music.

It is also mentioned by Mina in Dracula (though she, or Stoker, makes a small error - the scene mentioned involves characters from Whitby Abbey, but occurs in Lindisfarne, a tidal island that was also, long ago, the home of the illuminated Lindisfarne Gospels):

Right over the town is the ruin of Whitby Abbey, which was sacked by the Danes, and which is the scene of part of “Marmion,” where the girl was built up in the wall.

The book is a poetic epic set at the time of the Battle of Flodden Field (1513); I like the poetry a great deal, and the plot is nicely dramatic and Romantic, despite values dissonance (I do not find the title character as sympathetic as Scott does).

All this is to say - would people be interested in reading this story beloved by so many of our favourite characters? I could put it together as a Substack newsletter and email it out a little a day (probably for a few months total) starting in the new year. It’s not long (about 150 pages), it’s a good read with excellent poetic cadences and lots of high drama and imagery, and it gives a sense of what was popular among people who enjoyed the Gothic and Romantic.

#wildfell weekly#jane eyre#dracula#dracula daily#mina murray#the tenant of wildfell hall#marmion#sir walter scott

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Do you think the title of A Tangled Web could also have been inspired by that line in Marmion? Oh what a tangled web we weave when we practice to deceive. Not that they deceive, at least nobody gets up to anything dishonest (as far as I remember, I'm not participating in the book club (already doing other readalongs)) but they do get tangled up in the pursuit of the jug. So idk I'm probably way off, maybe LMM just liked the sound of it.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Have set on Sir Albany Featherstonhaugh,

And taken his life at the Deadman’s-shaw.

Sneaky little pronunciation guide for the worst of English surnames, here.

(it's Fan-shaw)

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mina's Fun Seaside Getaway

Here goes Bram Stoker again, peppering in extremely ominous references to popular literature. It’s true that Marmion was written close to a century before Dracula, but it was written by the one and only Sir Walter Scott, whose works were wildly popular and widely reprinted throughout the 19th century. And Mina Murray, nerd queen, arriving in Whitby, is very excited to see not only the graveyard, but also:

the scene of part of "Marmion," where the girl was built up in the wall.

I was a bit surprised, to be honest, not to find people in the Dracula Daily tag going “where the girl was what?!?” Because yes. Not that Sir Walter had any real historical evidence for this practice (I have lovingly ragged on him elsewhere for his... idiosyncrasies in this regard.) Nevertheless, this is the climactic episode of Canto II of Marmion, which is almost exclusively devoted to history. The poem takes place in the very early 16th century, before the dissolution of the monasteries, but this section is mostly dedicated to discussing the history of Whitby Abbey, including its history of connections to the otherworldly. And Mina alludes to the key feature of Whitby Abbey in Marmion: it features people who are buried but not dead. Two people, to be precise. One is a wicked man who does murder for fun and profit. This might remind you of someone in our narrative. The other is a beautiful, sensual, trusting young woman with gorgeous golden ringlets. This might also remind you of someone in our narrative.

Everything is fine.

#dracula daily#marmion#sir walter scott#gothic#mina my love i am glad you are genre savvy you just need to apply this more#angst and literary allusions

343 notes

·

View notes

Text

The disonance between the cantos of "In which Judgement is passed" and "In Which We Stop at an Inn" is truly fucked when we compare the situation between Constance de Beverley, and lord Marmion side by side.

Judgement is finally given to Constance, and her cellmate like it's a herald from god itself.

Till thus the Abbot’s doom was given, Raising his sightless balls to heaven:— “Sister, let thy sorrows cease;

Sinful brother, part in peace!”

From that dire dungeon, place of doom, Of execution too, and tomb,

Paced forth the judges three,

Part in peace... there is something so dark about telling the people that you are condemning to a possible death to go in peace, or that their sorrows will cease.

Although, I have to ask if in this canto is where Constance gets... put into a wall because of the metaphors used to convey the sheer terror that comes to the unsuspecting people that are not aware of the judgement.

That conclave to the upper day;

But, ere they breathed the fresher air, They heard the shriekings of despair, And many a stifled groan:

With speed their upward way they take, Such speed as age and fear can make, And crossed themselves for terror’s sake,

Are these shrieks of despair Constance's doing? Because as the canto goes to describe the overall ambiance that surrounded this unsettling moment, the shrieks got duller, and quieter.

Meanwhile this fucked up idea of justice is happening, or happened depending on the timeline, we start the third canto in an inn where lord Marmion and his army are staying for the time being.

No summons calls them to the tower,

To spend the hospitable hour.

To Scotland’s camp the lord was gone; His cautious dame, in bower alone, Dreaded her castle to unclose,

So late, to unknown friends or foes,

On through the hamlet as they paced, Before a porch, whose front was graced With bush and flagon trimly placed,

Lord Marmion drew his rein:

The village inn seemed large, though rude:

Yeah Constance is going to get trapped inside a fucking wall, but look! Lord Marmion found a problem! The poor lord, and his army didn't get the hospitality they wanted because the Dame rightfully didn't want to open her home to a bunch of men she didn't know while her husband was gone.

And now we are in a inn. There is laughter, food, and a very warm reading in what we now as modern readers can associated with what a medieval inn constitutes. And yet, the dread didn't left because the Palmer, once again a theme figure in contrast to Marmion, and his army, acts in a ominous manner.

Resting upon his pilgrim staff,

Right opposite the Palmer stood;

His thin dark visage seen but half,

Half hidden by his hood.

Still fixed on Marmion was his look, Which he, who ill such gaze could brook, Strove by a frown to quell;

But not for that, though more than once Full met their stern encountering glance, The Palmer’s visage fell.

Even if Constance's revenge is slowly building towards victory, she is still going to end up dead while Marmion enjoys (for now I hope) all of the privilegues of being an emisary to the king. It's literally a methaporical situation of the people serving the elite, Constance escaped with Marmion and dedicated a good chunk of her life to him, and he repaids her with abandoning her to force Clare to marry him.

The power imbalance is unreal, and it will feel so good when Marmion does a single misstep that brings all of his good fortune crashing down. Well, I hope it happens.

#Poor Constance tho#She still tried to kill Clare for “stealing” Marmion from her but being imprisoned inside a wall sounds like a nightmare#marmion daily#marmion#poetry

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

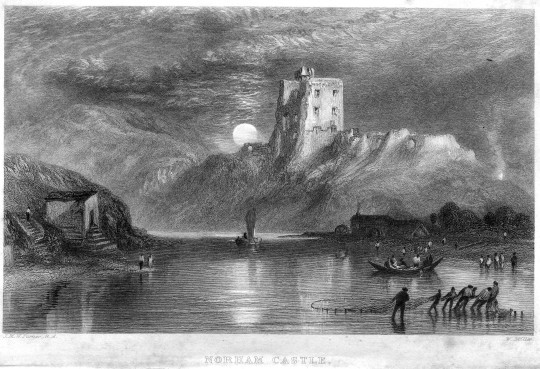

"Day set on Norham's castled steep,

The battled towers, the donjon keep..."

Norham! I stumbled across this imposing pile a few years ago while exploring the Tweed. It struck me as a very practical castle; not somewhere you would fight a tournament, but somewhere you would fight. In the first stanza we're told of captives weeping in the dungeon, which sets the tone: despite the lazy breeze and the sagging flag, the slow sunset and idly humming watchman, this is a frontier outpost under constant threat of invasion. Marmion's bugle-blast breaks the peace and plunges us towards the action of the poem.

Scott liked his visual setpieces. Norham Castle is one, painted by Turner below. Lord Marmion is another. We don't need to know all this about his charger, his charger's rein, or indeed his charger's mane, but Scott likes to illustrate. Why not? If you don't have the internet - if you don't have another book to follow - then you want vivid images to savour for as long as possible. You might not have a picture of a medieval lord on hand, so Scott gives you one through text.

My pet theory is that this is what makes Marmion difficult. You're not just reading a poem; you're looking at a moving picture.

Pause and paint the canvas on your mind, then continue on, the world a little brighter...

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

#marmion#A Tale of Flodden Field#Sir Walter Scott#poetry#jane eyre#novel#book#reading material#classic literature#1800s#19th century#charlotte brontë#currur bell#victorian literature#romance#gothic fiction#period drama

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jane Eyre - Charlotte Brontë (1847)

#jane eyre#charlotte bronte#currer bell#classic literature#books#novels#readingmaterial#paperback#quotes#favourites#1800s#19th century#Shakespeare#Macbeth#poetry#poem#Sir Thomas Moore#Fallen is Thy Throne#Marmion#Sir Walter Scott#romance#gothic fiction#nineteenth century#commonplace book

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

MARMION, A TALE OF FLODDEN FIELD by Sir Walter Scott. (London: Tilt, 1839) Illustrated edition. Cover designed by Henry Shaw.

#beautiful books#book cover#books books books#book blog#illustrated books#sir walter scott#marmion#vintage books#poetry

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

November’s sky is chill and drear,

November’s leaf is red and sear:

Late, gazing down the steepy linn,

That hems our little garden in,

Low in its dark and narrow glen,

You scarce the rivulet might ken,

So thick the tangled green-wood grew,

So feeble trilled the streamlet through:

Now, murmuring hoarse, and frequent seen

Through bush and brier, no longer green,

An angry brook, it sweeps the glade,

Brawls over rock and wild cascade,

And, foaming brown with doubled speed,

Hurries its waters to the Tweed.

No longer Autumn’s glowing red

Upon our Forest hills is shed;

No more, beneath the evening beam,

Fair Tweed reflects their purple gleam;

Away hath passed the heather-bell,

That bloomed so rich on Needpath-fell;

Sallow his brow, and russet bare

Are now the sister-heights of Yair.

The sheep, before the pinching heaven,

To sheltered dale and down are driven,

Where yet some faded herbage pines,

And yet a watery sunbeam shines;

In meek despondency they eye

The withered sward and wintry sky

And far beneath their summer hill,

Stray sadly by Glenkinnon’s rill:

The shepherd shifts his mantle’s fold,

And wraps him closer from the cold;

His dogs no merry circles wheel,

But, shivering, follow at his heel;

A cowering glance they often cast.

As deeper moans the gathering blast.

Walter Scott, from Marmion. Introduction to Canto I.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Marmion" (1885) by Sir Walter Scott

#marmion#sir walter scott#walter scott#knight#slain#knights#armour#england#scotland#britain#bosworth field#battle of flodden#art#illustration#image#engraving#history#medieval#middle ages#andrew varick stout anthony#1885#poem#book#page 170#a. fredericks

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy first day of both Silmarillion Daily (2024) - lasts all year, covers the Silmarillion in chronological order, posts intermittently based on (from the Awakening of the Elves onward) covering 3 years of in-universe time per day - and Marmion (covers the epic poem by Sir Walter Scott, a bit a day, from now until February 14)!

From now until January 19th, Silmarillion Daily will be covering the events of The Silmarillion (including the Ainulindalë and Valaquenta) that occur prior to the awakening of the Elves, a few pages at a time. Today’s entry covers the parts of the Ainulindalë prior to the entry of the Valar into Arda.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oh, this is even better:

Some lovelorn fay she might have been,

Or, in romance, some spell-bound queen;

For ne’er, in work-day world, was seen

A form so witching fair.

I love the expression "lovelorn fay". So beautiful!

#marmion#i bet anne of green gables loved this#right up her street#or right up her lane i should say. lovers lane#mypost

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Something I'm finding interesting about Marmion so far is how hard I find it to read. I think it's because it has such a strong rhyme scheme and rhythm (and Scott is happy to contort meaning and grammar to make the rhyme and rhythm work) so I just spend the whole time going tumpetty-tumpetty-tum instead of actually following what's going on.

Which led me to wonder how this would have been read at the time. The 19th century was fascinating for changing patterns of reading. In 1800 about 60% of men and 40% of women in the UK were literate, or at least literate enough to sign a marriage register, which might still have meant struggling with "Two pursuivants, whom tabarts deck/ With silver scutcheon round their neck" and similar. By 1900 97% were literate.

Another thing that changed over the course of the century was the gradual move away from reading aloud to an audience (who might or might not have been literate themselves), towards reading as a solitary and silent activity.

I find this interesting from the perspective of Marmion, since it was written at the start of the 19th century, and - at least to me - feels like it strongly lends itself to being read aloud. But it was a bestseller for the whole century, even as reading patterns changed.

11 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

marmion -- the secret plant

1 note

·

View note