#madame elisabeth

Text

I commend to God my wife and my children, my sister, my aunts, my brothers, and all those who are attached to me by ties of blood, or by any other manner whatsoever. I pray God especially to cast the eyes of his mercy on my wife, my children, and my sister, who have suffered so long with me; to support them by his grace if they lose me, and for as long as they remain in this perishable world.

#louis xvi#marie antoinette#marie therese charlotte#louis xvii#madame elisabeth#madame victoire#madame adelaide#louis xviii#charles x#house of bourbon#french monarchy#long live the queue

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

A miniature of Madame Elisabeth de France by Ignazio Pio Vittoriano Campana, circa 1785. Via Tajan Auctions.

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Queen is transferred from the Temple to the Conciergerie.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun (French, 1755-1842)

Madame Rousseau, femme de l'architecte Pierre Rousseau, et sa fille, 1789

Musée du Louvre

#Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun#1700s#art#fine art#fine arts#classical art#mother and child#motherhood#woman and child#oil painting#europe#european#culture#western civilization#madame rousseau

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oil Painting, 1789, French.

By Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun.

Portraying Madame Rousseau, the wife of the architect Pierre Rousseau, with her daughter.

Musée du Louvre.

#elisabeth vigee le brun#1789#1780s painting#1780s France#Madame Rousseau#musée du louvre#ancien regime#1780s hair#1780s child#third estate

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

#i've promised i won't say anything#i'll just leave it here...#but you know what i mean#laura roslin#president laura roslin#madam president#mary mcdonnell#sarah jane#sarah jane smith#elisabeth sladen#lis sladen#doctor who#dw#the sarah jane adventures#sja#battlestar galactica#bsg#sci-fi

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun ( FR, 1755- 1842)

#bornonthisday Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun ( FR, 1755- 1842) was a French painter who mostly specialized in portrait painting, in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Via Wikipedia #PalianSHOW

View On WordPress

#art#art by women#art herstory#Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun#Elisabeth loud vibe le brun#Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun#France#French#french painter#herstory#le brun#Louise Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun#Madame Le Brun#painter#PalianSHOW#Women&039;s Art

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

The Jules Simon anecdote made me wonder about Élisabeth and Charlotte’s relationship in general (and what Élisabeth said about Charlotte in her memoirs). Could you tell us more about them?

Thank you!

Sure!

Charlotte on Élisabeth:

I should tell the whole truth. I have nothing but praise for the demoiselles Duplay; but I would not say the same for their mother, who did me much wrong.

I have nothing but praise for Madame Duplay’s second youngest [sic] daughter, the one who married Lebas; she was not, like her mother and older sister, stirred up against me; many times she came to wipe away my tears, when Madame Duplay’s indignities made me cry. Her younger [sic] sister was good like her. Both of them would have made me forget their mother and Éléonore’s lack of courtesy, if it had not been that these things once engraved in such an indelible manner in one’s heart, are not thereafter effaced.

Élisabeth on Charlotte:

It was the day when Marat was borne in triumph to the Assembly that I saw my beloved Philippe Le Bas for the first time. I found myself, that day, at the National Convention with Charlotte Robespierre. Le Bas came to greet her; he stayed with us for a long time and asked who I was. Charlotte told him that I was one of her elder brother’s host’s daughters. He asked her a few questions about my family; he asked Charlotte if we came to the Assembly often, and said that on a particular day there would be a rather interesting session. He urged her to come to it. Charlotte asked my good mother for permission to take me there with her. At that time, my mother liked her a lot; she still had nothing to complain of. My mother was so good that she never refused her anything that could please her. She allowed me to accompany her many times.

Charlotte occupied an apartment in the front, in my father’s house on the Rue Saint-Honoré. I was also good friends with her, and it was a pleasure to go see her often; sometimes I even pleased myself to help her with her hair and her toilette. She too seemed to have much affection for me.

Finally Charlotte came to get me to be present at a session which was to be quite noisy. Le Bas came up to me; for the first time, he addressed me to tell me quite good things. He told Charlotte that there would be a night session, that it should be quite interesting, that she should ask permission for me to come with her. Charlotte had no difficulty obtaining it. She was Robespierre’s sister, and my mother regarded her as her daughter. Poor mother! She believed Charlotte as pure and sincere as her brothers. Great God! This was not so!

We went therefore to that session. We had brought oranges and some sweets. Charlotte offered some to Le Bas and to her younger brother. These messieurs, after having stayed with us for some time, left us to go vote. I asked Charlotte if I could offer Le Bas an orange; she said yes. I was happy to be able to show him an attention. He accepted with pleasure. How good and respectful he seemed to me! As I said already, Mademoiselle Robespierre seemed pleased with me.

At another session of the Assembly, where we found ourselves again together, she took a ring from me that I had on my finger. Le Bas saw and asked her to let him see it, which she did. He looked at the figure that was engraved on it, and he was obliged, at that moment, to go away to give his vote, without having the time to return the ring, which caused me great torment; for he could not return it to me, and I no longer had it on my finger. Our good mother was dear to all of us and we trembled to cause her pain. At that same session, Le Bas had lent us, Charlotte and I, a lorgnette. He returned, for a moment, to speak to Mlle Robespierre of what had just happened in the session; I wanted to return his lorgnette to him; he did not want to take it back and said that we were going to have need of it again. He begged me keep it. He went away again, and, at that moment I pleaded with Charlotte to ask him for my ring back; she promised me to do so, but we didn’t see Le Bas again.

I regretted no longer having my ring and not being able to return his lorgnette to him. I feared to displease my mother and be scolded; this was a great torment to me. My mother was good, but very severe. Charlotte said, to console me: “If your mother asks you for your ring, I will tell her how the thing happened.” All this made me quite unhappy: it was the first time such a thing had happened to me. From that time, we did not have occasion to return to the Convention again. Charlotte told me to be calm about what tormented me so. She also told me that M. Le Bas was quite sick and could no longer return to the Assembly.

Upon my return I went to see Charlotte; I feared to speak to her about Le Bas; I was afraid she would think it was only about the ring. She seemed happy to see me and also found me changed. I asked her then if it had been a long time since she had gone to the Convention; she said yes and I could learn no more from her.

Yes, I preferred to go take in wash on a boat rather than ask assistance of our poor friends’ assassins. I feared neither death nor persecution. I was not the one who repudiated my name; it pains me to say it, but Mlle Robespierre was the one who took her mother’s name, Charlotte Carreau [sic].

I think that’s everything we have regarding their relationship, I don’t know of any contemporary who mentioned the two together.

#I wonder who is right about madame duplay here…#elisabeth lebas#elisabeth duplay#charlotte robespierre#ask#frev

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, 1796 - Les Grandes-Duchesses Alexandra et Eléna Pavlovna, Filles de Paul (L'Ermitage) - (Detail) [x]

#Vigée-Le Brun Elisabeth#Madame Le Brun#les grandes duchesses#les grandes duchessses alexandra et elena pavlova#art#art details#art history#russian nobility#alexandra pavlova#elena pavlova#french#french artist#french art#women artists#18th century#18th century art#post rococo#rococo art#french rococo#neoclassical#neoclassicism#aesthetics#royalty#royalty aesthetic

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

Congratulations to everyone on the release of kuroshitsuji season 4 traile

college arc (67-84)The frame itself from the manga from chapter 67Trailer frame timecode 0:45

#our ciel#Ciel phantomhive#Sebastiankuroshitsuji#kuroshitpost#madam red#Sempai#finny#finnian#Lizzy#Elisabeth

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jeanne Bécu, Comtesse du Barry (19 August 1743 – 8 December 1793) was the last maîtresse-en-titre of King Louis XV of France. She was executed, by guillotine, during the French Revolution due to accounts of treason—particularly being suspected of assisting émigrés flee from the Revolution.

In order for the king to take Jeanne as a maîtresse-en-titre, she had to be married to someone of high rank so she could be allowed at court; she was hastily married on 1 September 1768, to Comte Guillaume du Barry. The marriage ceremony was accompanied by a false birth certificate, created by Jean du Barry. The certificate made Jeanne younger by three years and dissimulated her “poor” background. Henceforth, she was deemed as an official maîtresse-en-titre to the king.

Her arrival at the French royal court was considered scandalous by some, as she had been a prostitute and a commoner. For these reasons, she was disliked by many, including Marie Antoinette. Marie Antoinette's disfavoring Jeanne and refusing to speak to her was seen as a major issue within the royal court and had to be resolved. On New Year's Day 1772, Marie Antoinette remarked to Jeanne, “There are many people at Versailles today.” This little interaction pleased both Jeanne and the royal court, and the dispute ended, though the latter still disapproved of Jeanne thereafter.

During the Reign of Terror, a subpart of the French Revolution, Jeanne was imprisoned due to accounts of treason, the claims being made by her page Zamor. Soon after her imprisonment, she was executed—by guillotine—on 8 December 1793. Her body was buried in the Madeleine cemetery. The gems she had smuggled out of France during the Revolution were found due to her confession, and were sold at in auction in 1795.

#Jeanne Bécu#Madame du Barry#XVIII century#people#portrait#elisabeth vigee lebrun#paintings#art#arte

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

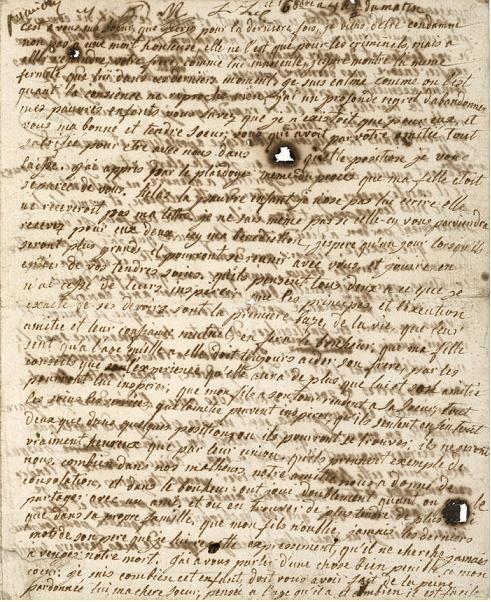

In the early morning hours of October 16th, having been condemned to death by guillotine, Marie Antoinette was led back to her cell in the Conciergerie. She wrote the following letter to her sister in law, Madame Elisabeth, but it would never reach her.

Here is a translation of the letter, images of the original are above.

16th October, 4.30 A.M.

It is to you, my sister, that I write for the last time. I have just been condemned, not to a shameful death, for such is only for criminals, but to go and rejoin your brother. Innocent like him, I hope to show the same firmness in my last moments.

I am calm, as one is when one's conscience reproaches one with nothing. I feel profound sorrow in leaving my poor children: you know that I only lived for them and for you, my good and tender sister. You who out of love have sacrificed everything to be with us, in what a position do I leave you! I have learned from the proceedings at my trial that my daughter was separated from you. Alas! poor child; I do not venture to write to her; she would not receive my letter. I do not even know whether this will reach you. Do you receive my blessing for both of them. I hope that one day when they are older they may be able to rejoin you, and to enjoy to the full your tender care. Let them both think of the lesson which I have never ceased to impress upon them, that the principles and the exact performance of their duties are the chief foundation of life; and then mutual affection and confidence in one another will constitute its happiness. Let my daughter feel that at her age she ought always to aid her brother by the advice which her greater experience and her affection may inspire her to give him. And let my son in his turn render to his sister all the care and all the services which affection can inspire. Let them, in short, both feel that, in whatever positions they may be placed, they will never be truly happy but through their union. Let them follow our example. In our own misfortunes how much comfort has our affection for one another afforded us! And, in times of happiness, we have enjoyed that doubly from being able to share it with a friend; and where can one find friends more tender and more united than in one's own family? Let my son never forget the last words of his father, which I repeat emphatically; let him never seek to avenge our deaths.

I have to speak to you of one thing which is very painful to my heart, I know how much pain the child must have caused you. Forgive him, my dear sister; think of his age, and how easy it is to make a child say whatever one wishes, especially when he does not understand it. It will come to pass one day, I hope, that he will better feel the value of your kindness and of your tender affection for both of them. It remains to confide to you my last thoughts. I should have wished to write them at the beginning of my trial; but, besides that they did not leave me any means of writing, events have passed so rapidly that I really have not had time.

I die in the Catholic Apostolic and Roman religion, that of my fathers, that in which I was brought up, and which I have always professed. Having no spiritual consolation to look for, not even knowing whether there are still in this place any priests of that religion (and indeed the place where I am would expose them to too much danger if they were to enter it but once), I sincerely implore pardon of God for all the faults which I may have committed during my life. I trust that, in His goodness, He will mercifully accept my last prayers, as well as those which I have for a long time addressed to Him, to receive my soul into His mercy. I beg pardon of all whom I know, and especially of you, my sister, for all the vexations which, without intending it, I may have caused you. I pardon all my enemies the evils that they have done me. I bid farewell to my aunts and to all my brothers and sisters. I had friends. The idea of being forever separated from them and from all their troubles is one of the greatest sorrows that I suffer in dying. Let them at least know that to my latest moment I thought of them.

Farewell, my good and tender sister. May this letter reach you. Think always of me; I embrace you with all my heart, as I do my poor dear children. My God, how heart-rending it is to leave them forever! Farewell! farewell! I must now occupy myself with my spiritual duties, as I am not free in my actions. Perhaps they will bring me a priest; but I here protest that I will not say a word to him, but that I will treat him as a total stranger.

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I don’t know why it is, but I am always ready to hope. Do not imitate me; it is better to fear without reason than to hope without it; the moment when the eyes open is less painful. –Madame Elisabeth, 1789.

Élisabeth Philippine Marie Hélène de France, better known as Madame Élisabeth, was executed by guillotine on May 10th, 1794. Élisabeth had chosen to remain with her brother and the rest of the royal family during the revolution and was imprisoned in the Temple Tower alongside them in the fall of 1792. She was brought before Revolutionary Tribunal on May 9th, 1794 and was condemned to die the next day, along with 23 other men and women.

Élisabeth was the last of the group to die; according to witnesses, she offered every one of the prisoners encouraging words and recited the De profundis until she mounted the scaffold.

After being strapped to the plank of the guillotine, her fichu came loose, exposing her; her last words were “In the name of your mother, monsieur, cover me.”

115 notes

·

View notes

Text

'We are not asked to sacrifice our faith like the early martyrs, but only our miserable lives; let us offer this little sacrifice to God with resignation'. Madame Elisabeth of France

1 note

·

View note

Text

The gardens of Montreuil

Versailles, France

#montreuil#versailles#france#europe#travel#travelling#garden#nature#bee#flowers#domaine de madame elisabeth#mme elisabeth#my photos

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A mythological portrait of King Louis XIV and the French royal family by French painter Jean Nocret.

#king louis xiv#philippe duke of orleans#henriette anne stuart#anne marie louise of orleans#queen henrietta maria#anne of austria#maria theresa of spain#louis grand dauphin#marie therese madame royale#philippe charles duke of anjou#marguerite louise of orleans#elisabeth marguerite of orleans#francoise madeleine of orleans#royal painting#art

14 notes

·

View notes