#handbook of diagnosis and treatment of dsm-5 personality disorders

Text

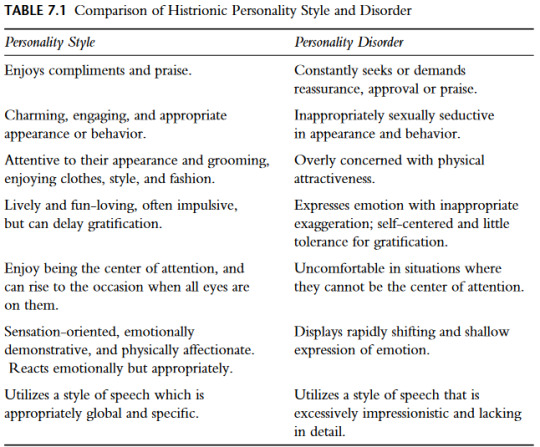

Clinical Formulations of Histrionic PD

Clinical formulations and case conceptualisations are introduced in this post.

These are all generalisations and theories of how HPD develops, not something that is supposed to be true for everyone with HPD.

Psychodynamic model

Histrionics lack relationships with maternal caregivers so turn to paternal caregivers for love and attention

Learn that they can get attention through sexualised behaviours

Men with HPD may be hypomasculine (effeminate) or hypermasculine if their paternal caregiver is emotionally unavailable

Biosocial model

Mood swings, very emotional

Biggest influences are environmental: caregivers’ reinforcement of attention-seeking & manipulative behaviours and histrionic role models

Children learn they can use cuteness, charm, attractiveness & seductive behaviours to get what they want/need (attention from caregivers)

Histrionics are externally focused and largely ignore their internal worlds

Histrionic behaviours are self-perpetuating

Cognitive-Behavioural model

Two main underlying assumptions: “I am inadequate and unable to handle life by myself” and “I must be loved by everyone to be worthwhile.”

Need attention and approval from others, and in a similar way to DPD feel they are inadequate to look after themselves and need others

Hypersensitive to rejection & criticism (similar to DPD, NPD and AvPD)

Feel they must perform for others to gain approval and self-esteem

Thinking is “impressionistic, global, and unfocused” and leads to over-generalisation, emotional dysregulation, and splitting

Two subtypes:

The controlling type, who tries to gain control through dramatics and manipulation; they struggle with reading others’ emotions and are shallow, self-centred, and uncomfortable without immediate assurance; lack empathy.

The reactive type tries to gain approval and reassurance.

Interpersonal model

People with HPD learnt that their entertainment value and appearance was more important to others than their worth as a person

Learnt that physical appearance and charm can be used to manipulate others

Their childhood homes were unpredictable and probably involved substance abuse

The unpredictability was dramatic and interesting (unlike the “primitive” and life-threatening chaos associated with BPD)

Histrionics were likely rewarded (i.e. had their physical and emotional needs met) for their disabilities, illnesses and complaints

Histrionics “exhibit a strange fear of being ignored, together with a wish to be loved and taken care of by important others, who can be controlled through charm or guile.”

Integrative model

Histrionics experience reactive mood swings and have high levels of energy

They are hyper-responsive and externally oriented

“The self-view of the histrionic will be some variant of the theme “I am sensitive and everyone should admire and approve of me.” The world-view will be some variant of “Life makes me nervous so I am entitled to special care and consideration.” Life goal is some variant of the theme “Therefore, play to the audience, and live in the moment.””

Cargivers’ style based in reciprocity, i.e. “I’ll give you attention if you do what I want”, with minimal or inconsistent discipline and probable neglect

Internal experiences of HPD are “denial of one’s real or inner self; a preoccupation with externals; the need for excitement and attention-seeking, which leads to a superficial charm and interpersonal presence; and the need for external approval. This, in turn, further reinforces the dissociation and denial of the real or inner self from the public self, and the cycle continues.”

- From Sperry, Handbook of Diagnosis and Treatment of DSM-5 Personality Disorders (2016)

#clinical formulations#case conceptualisations#case conceptualisation#hpd#hpd info#pd info#dogpost#len sperry#handbook of diagnosis and treatment of dsm-5 personality disorders#this has been in my drafts for 10 months LOL#also re reading this its like 'people w hpd were neglected and so they try to get their needs met thru trying to get ppl to love them#which is OBVIOUSLY manipulative and selfish right?? /sarcasm#personality disorder concepts

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Takahiro A. Kato et al., Multidimensional anatomy of ‘modern type depression’ in Japan: A proposal for a different diagnostic approach to depression beyond the DSM-5, 70 Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 7 (2016)

Abstract

Japan’s prototype of depression was traditionally a melancholic depression based on the premorbid personality known as shūchaku-kishitsu proposed by Mitsuzo Shimoda in the 1930s. However, since around 2000, a novel form of depression has emerged among Japanese youth. Called ‘modern type depression (MTD)’ by the mass media, the term has quickly gained popularity among the general public, though it has not been regarded as an official medical term. Likewise, lack of consensus guidelines for its diagnosis and treatment, and a dearth of scientific literature on MTD has led to confusion when dealing with it in clinical practice in Japan. In this review article, we summarize and discuss the present situation and issues regarding MTD by focusing on historical, diagnostic, psychosocial, and cultural perspectives. We also draw on international perspectives that begin to suggest that MTD is a phenomenon that may exist not only in Japan but also in many other countries with different sociocultural and historical backgrounds. It is therefore of interest to establish whether MTD is a culture-specific phenomenon in Japan or a syndrome that can be classified using international diagnostic criteria as contained in the ICD or the DSM. We propose a novel diagnostic approach for depression that addresses MTD in order to combat the current confusion about depression under the present diagnostic systems.

Clinical Picture

Case: male, 24 years old

Chief complaint: No desire to do anything

Medical history: No previous psychiatric disorder

Family history: Nothing of note

Developmental and social history: He is the first son, with an older sister. His father is a company employee, his mother a full-time homemaker. There was nothing particularly problematic during junior or senior high school, although apparently he sometimes deliberately did not apply himself to the subjects of teachers that he disliked. At university he took part in group activities and had a part-time job, just like other students. He was not terribly enthusiastic about searching for a job and aimed to become a civil servant. After graduation, he attended a vocational college for a year to prepare for the entrance exam to the civil service, and at the age of 23 started to work in the municipal government of a provincial city – he says he just happened to sit the exam and pass it.

History of present illness: He did not particularly dislike the work in the place he was assigned to after being hired, though he was not greatly interested in it either. However, he would occasionally be absent from work; he says this was because he had an annoying boss who he couldn’t stand the sight of. Nonetheless, it was not a case of being unable to go to work because he was depressed, and when he was absent from work he would play slot machines, go to the movies, or go shopping. In June 2010, a year after starting work, he married a female colleague from the same work-place with whom he had fallen in love. In May 2011, his first child was born. He was still halfhearted about his job, but also finding it hard to be at home, he would play slot machines or go to the movies. Raising the child proved to be very difficult, but his wife had stopped working and, together with both his mother and her own mother, managed the household very well.

In December 2011, his boss reprimanded him for his attitude toward his work. He had previously been given warnings on a number of occasions, but apparently this time the reprimand he received was very severe. He subsequently left work early, complaining of feeling unwell. He says that from that day on he was unable to sleep at night. He became easily irritated and tended to have feelings of desperation. Even though, he went to work properly every day. Whilst at work, he had no motivation to do anything and had no energy. He would become angry and did not feel like attending work social events, such as the year-end party or the New Year party. He would tend to stay out of his boss’s sight. He would feel a little more cheerful only when he played slot machines and when spending time in an Internet cafe, but when he went home he would again slip into gloom because, he says, he found it boring. His anger was not toward himself but others, such as his boss and his wife. He sometimes would feel valueless himself; however, he could alleviate such unpleasant feelings by his devotion toward his hobbies. His sleep was constantly mildly disturbed but not severely, and sometimes he would have trouble getting to sleep and fail to get up in the morning. Therefore, from around the middle of January he started to fail to go into his office once/twice a week and during this absence he would surf the net to relax or go out to play slot machines.

In March of 2012, he found a site on the Internet called ‘Mind medicine cures your Depression!!’ which contained a checklist for depression, and he quickly came to believe that he himself must have ‘depression.’ The following day, he decided to go to a local psychiatric clinic for a prescription of antidepressants. He entered the examination room, greeting the doctor politely, then he voluntarily read out his life history and medical history from a memo he had prepared. When he finished, he handed the psychiatrist in charge a depression checklist, which he had found on the Internet, and requested a particular medicine by himself: ‘Doctor, as I have just mentioned, these diagnostic criteria apply to me. I heard that selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors are effective.’ Based on his examination, his score on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression1,2 was 17 (mild depressive level); he met the DSM-IV criteria for a major depressive episode (based on the handbook, entitled Quick Reference to the Diagnostic Criteria from DSM-IV-TR3) and was diagnosed as suffering from depression. He requested a medical certificate then and there. Additional clinical history revealed that he did not meet the diagnostic criteria for avoidant personality disorder, schizoid personality disorder, or narcissistic personality disorder. Also, according to information supplied by his wife, who was present when he was examined, there was nothing particular in the symptoms to suggest that the illness was feigned.

This clinical picture was originally used for the symposium during the 109th annual meeting of The Japanese Society of Psychiatry and Neurology in Fukuoka, 2013.

Introduction

Cases like the above have emerged in Japan since around 2000, and these cases have been called ‘modern type depression (MTD)’ – a novel form of depression. This catchy ‘modern’ name has quickly and widely spread to the public via Japan’s mass-media and Internet-related media, while the name itself has not been regarded as an official medical term, and there is no consensus guideline for its diagnosis and treatments, which has led to confusion when dealing with MTD in clinical practice. Scientific literature about MTD remains very limited. In this review paper, we summarize and discuss the present situation and issues regarding MTD – focusing on historical, diagnostic, sociocultural and international perspectives, by referring to our recent international survey.4 Is MTD a phenomenon limited to Japan? The pilot survey has indicated that MTD may exist not only in Japan but also in many other countries with different sociocultural and historical backgrounds. It is therefore of interest to establish whether MTD is a cultural phenomenon specific to Japan or a syndrome that can be classified using the present international diagnostic criteria of the ICD/DSM. Finally, we propose a novel diagnostic system of depression including MTD in order to combat current confusion regarding the diagnosis of depression under the present ICD/DSM diagnostic systems.

Historical Background

Just since the beginning of the 21st century, Japanese psychiatrists have increasingly reported patients with a type of depression that does not seem to fit the criteria of the ICD-10 and the DSM-IV, and which is widely denoted as MTD among Japanese psychiatrists. The Japanese psychiatrist/psychopathologist Shin Tarumi reported the increasing occurrence of MTD and he labeled MTD as Dysthymia-gata utsu-byo (dysthymic type of depression) in the Japanese literature.5,6 Tarumi described the associated premorbid personality as Typus dysthymicus (TD) and compared it with Japan’s traditional type of depression.5,6 Tarumi defined the characteristics of MTD with TD as follows: (i) younger generation; (ii) attachment to oneself with less loyalty for social structures; (iii) feeling distressed about rules/order; (iv) negative feelings about social order/models; (v) vague sense of omnipotence; and (vi) not hard-working by nature (Table 1).6–17 MTD is also characterized by (a) distress and reluctance to accept prevailing social norms; and (b) avoidance of effort and any strenuous work.4,18 Most sufferers of MTD are born after 1970, that is, the generation growing up with home video games in the era of Japan’s high economic growth. Youths with MTD tend to feel depressed only when they are at work; otherwise, they can enjoy the virtual world of the Internet, video games, and pachinko (Japanese pinball). Therefore, sufferers of MTD have difficulties in adapting to work/school and participating in the labor market.

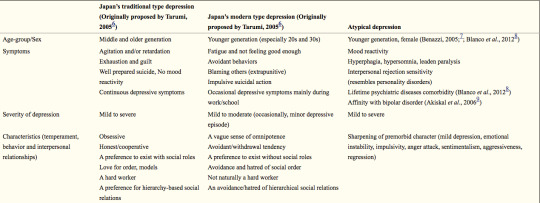

Table 1. Comparison between Japan’s traditional type depression, Tarumi’s Japan’s modern type depression and atypical depression

This table is a proposed comparison between Japan’s traditional type depression, Japan’s modern type depression and atypical depression according to Tarumi 2005,6 Tarumi & Kanba 2005,5 and Kato et al. 2011.4 Data, especially the section on ‘Drug response/Therapeutic intervention,’ has not yet been validated. ECT, electroconvulsive therapy.

Formerly, the melancholic type of depression had been regarded as a typical form of depression amongst the Japanese population, whose premorbid personality was defined as shūchaku-kishitsu (SK) by the Japanese psychiatrist Mitsuzo Shimoda.10,19 Shimoda characterized SK as: (i) middle aged; (ii) strong loyalty to society and community and one’s role within these structures; (iii) a preference for rules and order; (iv) positive feelings about social order/models; (v) attentive and diligent; and (vi) fundamentally hardworking.10,19,20 SK has been discussed in a similar context to Tellenbach’s Typus melancholicus (TM), which was identified amongst Germans after World War II.11 Tellenbach described the premorbid personality of patients with unipolar endogenous depression as orderly, devoted to duty and to family members, and scrupulous.11 Such types of depression based on SK and TM are considerably different from MTD. On the other hand, since the 1970s, different types of depression have been reported by Japanese psychiatrists and psychopathologists, such as taikyaku shinkei-sho (withdrawal neurosis);13 tohi-gata utsu-byo (avoidant type of depression);14 gendai-gata utsu-byo (modern type of depression);15 and mizyuku-gata utsu-byo (immature type of depression).16 Commonalities between the above types of depression and the currently emerging MTD have been pointed out. The former (taikyaku shinkei-sho, tohi-gata utsu-byo, gendai-gata utsu-byo and mizyuku-gata utsu-byo) was limited to highly educated youth, but MTD has been known to affect youth regardless of educational backgrounds.4

The 24-year-old man presented in the above clinical picture expressed moderate depressive symptoms just after a stressful event at his workplace. He came to regard himself as having severe depression, and finally he asked a doctor for sick leave in order to take a rest. His depressive symptoms mainly emerged during working time, and his symptoms were relieved in other situations. His characteristics, including behaviors and interpersonal relationships, contained the following features: not naturally a hard worker; an avoidance/hatred of hierarchical social relations; a preference to exist without social roles; extrapunitive type; and a vague sense of omnipotence. These features are exactly matched with MTD proposed by Tarumi.5,6

Diagnostic Issues of MTD

MTD has not been regarded as an official medical term, and various diagnoses have been applied based on ICD-10 and DSM-IV criteria. Our case vignette survey among Japanese psychiatrists suggests that MTD tends to be diagnosed as a variety of psychiatric disorders, such as mood disorder (296, code of DSM-IV; the same shall apply hereafter), dysthymic disorder (300.4), adjustment disorder (309) and adjustment disorder with depressed mood (309.0) by Japanese psychiatrists.4 Interestingly, some Japanese psychiatrists reported that categorical diagnostic systems, such as the ICD-10 and the DSM-IV, are not applicable to MTD. The case vignette survey was also administered to foreign psychiatrists at the same time, which revealed that they tend to diagnose the MTD case as mood disorder (296), dysthymic disorder (300.4), adjustment disorder (309), adjustment disorder with depressed mood (309.0) and adjustment disorder with mixed anxiety and depressed mood (309.28). Based on the reports and our clinical experiences in Japan, it is challenging to differentiate between MTD and other types of depression, such as atypical depression (AD) and dysthymia.

Atypical depression

It is often difficult to differentiate MTD from AD due to some overlap of their clinical features, including young onset, impulsivity, aggression toward others, behavioral symptoms similar to personality disorders, being refractory to treatment, and severe social disability caused by a chronic clinical course.7,8,21

Patients with MTD tend to have specific features of personality or characteristics, while patients with AD have no such features. However, it is also well known that the characteristics of AD patients would alter dramatically around the onset of AD, showing its aggressive and impulsive aspects. Around the onset of AD, the characteristics in patients with AD often sharpen, and their emotions become unstable. The features and alterations of characteristics in patients with both AD and MTD often lead to interpersonal rejection sensitivity and social disability. Formerly, Klein suggested the concept of ‘hysteroid dysphoria’ in regards to the disease concept related to AD,17 and recently, AD has been suggested to have the affinity of characteristics or symptoms with bipolar II disorder.9 In the present stage, there exists no specific markers to differentiate MTD from AD, but specific symptoms of AD (hyperphagia, hypersomnia, leaden paralysis, and mood reactivity) seem to be useful for the differentiation.

Dysthymia

Dysthymia is also on the differential diagnosis for MTD, because both show a chronic clinical course and less severe depressive symptoms. In regards to this differentiation, the Japanese psychiatrist Shin Tarumi did not refer to the distinct difference between the two diseases and just stated ‘MTD has not completely become dysthymia yet.’5,6

In DSM-5, dysthymia (dysthymic disorder) was combined with chronic major depressive disorder under the name of persistent depressive disorder.22 The DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for persistent depressive disorder still characteristically include subjective superior symptoms, but not some objective depressive symptoms, such as psychomotor agitation/inhibition and suicidal ideation. These would be common features of MTD. Needless to say, the concept of dysthymia itself has not been clearly defined, which makes the differentiation between MTD and dysthymia more difficult.

Previously, Akiskal developed a framework of soft bipolar from subaffective dysthymia to character-spectrum disorders by therapeutic reactions.23 Similar to soft bipolar, the present situation has suggested that MTD might be heterogeneous. Therefore, further studies are needed to clarify the syndrome of MTD, which has important implications for the selection of appropriate interventions.

Personality disorder

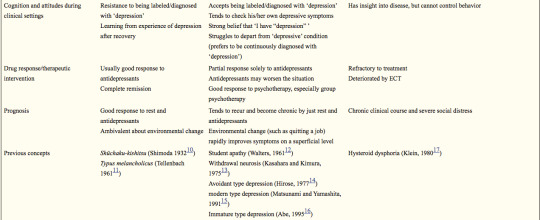

Tarumi did not include the comorbidity of personality disorders (avoidant personality disorder, schizoid personality disorder, or narcissistic personality disorder) in clinical case descriptions of MTD in his original paper.5 However, the international case vignette survey by Kato et al. in 2011 has suggested that personality problem is the most highly influential factor for MTD, and a variety of personality disorders are suggested to be comorbid with MTD.4 The underlying features of personality have yet to been clarified, while psychopathologists have highlighted the temperamental features of MTD syndrome as narcissism (omnipotence) and avoidance.5,6,24 In addition, immaturity may be an important factor.25 People who originally have a tendency toward an immature and narcissistic personality may easily develop depression and evasive behaviors when confronted with stressful situations at school and in the work-place (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Multidimensional understandings of Japan’s modern type depression (MTD). A variety of psychosocial factors, from the early stages of life through to adolescence, have been suggested to contribute to the onset of MTD. Especially important are childrearing, school and later workplace environments. Within this, parent–child relationships, and how/whether good-enough relationships between peers and friends have been established is vital. The establishment of these bonds can facilitate smooth relationships with workplace colleagues and superiors later in life. However, in MTD, the establishment of such fundamental interpersonal skills during the early stages of life may be insufficient, which can induce vulnerability to stress, meaning that mental dysfunctions are more likely to develop. In other words, lower resilience and the greater possibility of experiencing stress traumatically. Regarding the sociocultural impact in Japan, along with modernization and globalization, there has been a continuing shift away from the hitherto respected and venerated ‘group mentality’ to an ‘individualism’ in which individual achievements are pursued and this shift has resulted in rapid changes in school and work environments. In addition, we suppose that such sociocultural factors are occurring along with an interrelated biological basis, and it is important not to ignore underlying biological factors. With regards to diagnosis and evaluation of MTD, we are in a transitional period and a differential method to distinguish from existing psychiatric diagnoses is warranted. HPA, hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal.

On the other hand, in the case vignette survey, only Japanese psychiatrists disregarded the factor of personality – SK, that is, immodithymia – as a component cause of Japan’s traditional type of depression, while many psychiatrists in other countries believed that the SK personality strongly affects the onset of depression as a pathological factor. Generally speaking, the Japanese are regarded to be a diligent, scrupulous and hard-working people, and such personality traits have been positively accepted and moreover encouraged in Japanese society over a long period of history since the Samurai era.26 However, these personality traits are not always considered to be positive but as a cause of illness, such as obsessional personality, by experts, including psychiatrists, anthropologists and sociologists in Japan and other countries.27,28 Therefore, Japanese psychiatrists’ opinions in the case vignette survey indicate that not only lay people but also psychiatrists in Japan have been influenced by such Japanese cultural contexts.4

Interestingly, a Japanese clinical study, published in 1997, suggested that TM, which is similar to SK, is not the premorbid personality trait of unipolar (endogenous) depression in Japan.29 This result might have predicted the recently suggested prototype shift of depression in Japan from TM to TD.30

On the other hand, Kotov et al. performed a meta-analysis regarding the association between the personality traits in the Big Three model (negative emotionality, positive emotionality, and disinhibition vs constraint) and Big Five model (neuroticism, extraversion, conscientiousness, agreeableness, and openness), and common psychiatric disorders, such as depression, anxiety and substance abuse disorders.31 The meta-analysis revealed that these common psychiatric disorders are strongly connected to personality. Both major depressive disorder (MDD) and dysthymic disorder showed a similar tendency for high neuroticism and low conscientiousness. Dysthymic disorder showed the most pathological profile. Actually, more than other ailments, dysthymic disorder showed extremely negative extraversion, negative conscientiousness, and positive disinhibition. There is a fairly small number of studies but this outcome is consistent with the argument that dysthymic disorder may be best seen as a form of personality disorder.32 Indeed, dysthymic disorder tends to be chronic and is often lifelong.33 Hence, prominent personality disturbance can be expected to manifest in dysthymic disorder. Surprisingly, the connection between MDD and extraversion was unexpectedly weak. On the other hand, low extraversion was revealed to play an important role in dysthymic disorder. Prospective studies are extremely rare in this field and a causal relationship is yet to be elucidated. Moreover, there are only a few longitudinal studies, the problem of comorbidity, and other limitations (Japanese clinical data seem not to be included in this meta-analysis). In spite of these limitations, this meta-analysis is an important resource when considering the relationship between MTD and personality.

Further clinical, psychopathological and epidemiological studies are needed to clarify underlying personalities, temperaments and characteristics of depression and MTD among particular cultural groups.

Sociocultural Aspects

Psychiatric disorders are strongly influenced by culture, society, history and region.34,35 In any case, much attention should be paid to any medical culture that allows for an immediate diagnosis and the dispensation of medicines in such cases. Japan’s rapid socioeconomic and cultural changes have affected the lifestyle, behavior and mentality of people of all ages in Japan,36 and new types of psychiatric disorders or behavioral disorders have recently appeared in Japan. Tarumi suggested that MTD is caused by the unique Japanese cultural background and sociocultural changes in Japan.5,6 Tarumi regarded MTD as the byproduct of Japan’s historical socioeconomical shifts; beginning with World War II, the following period of high and rapid economic growth (1960–1980s), the economic crisis (1990s), and the diversity and complexity of modern society in the 21st century.5,6 Traditionally, Japanese society has greatly encouraged immodithymia, but modernization, globalization and the introduction of Western culture have led to a mixture of cultures and the celebration of individualism in Japan. The effects of changes in the education system and a move from its traditional disciplinarian base to Yutori education, a system that emphasizes the individual and freedom, may have been great. In the corporate world, the collapse of the traditional nenkō joretsu or seniority-based promotion system will also have had an effect. With the disintegration of the seniority system, there has been an evolution to an intensely competitive society and a distancing from the traditionally harmonious Japanese sense of group belonging.37 It has been suggested that a lack of a sense of belonging could be behind the increase in middle–older-age suicide.38,39 With regards to MTD, the problem of such a sense of belonging may be another major consideration. In the corporate world, younger employees who do not have such a sense of belonging and exhibit aspects of depression at work are often able to function normally and happily with such a sense on weekends, at places of leisure and/or online (Facebook, etc.), and this may reflect that very lack of a sense of belonging within the traditional Japanese organizations. According to the analysis by Takahashi et al.,40 the Japanese corporate organization gave a sense of belonging and community to workers because of its long-term-based relationship under the systems of seniority and permanent employment. After the burst of the bubble economy in the 1990s, however, these traditional systems collapsed and this organization no longer provides a sense of community or belonging.

Unfortunately, Japanese society had not prepared for the effects of this transition. Thus, patients with symptoms of MTD may have often been judged as lazy or ‘sloths’ because one of the most highlighted characteristics of MTD is the tendency to feel depressed only during work or at school.4,18

MTD and hikikomori based on amae

While the psychopathology of MTD is not well understood, it has been suggested that it is related to amae and other Japanese forms of mentality, a suggestion that raises the possibility of MTD as a cultural syndrome or form of psychopathology that predominates in Japan.28

Takeo Doi, a psychiatrist and psychoanalyst, described Japanese dependent behaviors with the word amae.28 The person who is acting amae may beg or plead, or alternatively act selfishly and indulgently, while secure in the knowledge that the caregiver will forgive this. The behavior of children towards their parents is the most typical example of amae. Doi argued that child-rearing practices in Western society seek to stop this kind of dependence in children, whereas in Japan it persists into adulthood in all kinds of social relationships.28 Even now, compared to Western societies, in Asian societies, including Japan, Korea and Taiwan, young people tend to be more economically dependent on their parents, and this phenomenon seems to be one of the expressed forms of amae.41 Hikikomori, a form of social withdrawal characterized by persistent isolation in one’s home for more than 6 months, may be indirectly promoted by amae to the extent that parents accept their child staying at home for prolonged periods of time.41 Even though the concept of amae was originally considered to be uniquely Japanese, contemporary opinions suggest that amae is actually more universal in nature.42 Thus, there is an interesting parallel to hikikomori that has been thought of as unique to Japan but, as our preliminary results show, is perceived by psychiatrists as occurring in a variety of other countries.41 In addition, our international clinical investigations have revealed real hikikomori persons in different countries, including the USA.43,44 These facts suggest that hikikomori and/or MTD could also be a universally observed psychiatric problem.

Cultural/social psychological understandings of MTD and hikikomori

The sociocultural background and tradition of amae is related to hikikomori and MTD. On the other hand, as another research stream, cultural psychologists and social psychologists have focused on the cultural uniqueness of inter-dependence with experiment and quantitative methods.45–49 A common argument being that East Asians are more collectivistic and/or more inter-dependent than Westerners.50–52 In a collectivist culture, inter-dependence is emphasized and in an individualist culture, independence has more value than inter-dependence. A common traditional assumption of these concepts is that collectivistic people tend to prefer harmonious inter-dependence to individual motivation or self-interest. This means that collectivists are ‘harmony seekers.’ On the other hand, Hashimoto and Yamagishi have claimed that the above assumption is not necessarily true, and have recently proposed a novel dimension, namely ‘dis-engaging inter-dependence.’53 They have claimed that the conventional distinction has focused only on dis-engaging independence and engaging interdependence, and relatively ignored the opposite (engaging independence and dis-engaging interdependence). Engaging independence is characterized as voluntary formation of interaction relationships with others to find desirable interaction partners and to prove to others that one is a desirable interaction partner. Hence, individualistic and harmonious. On the other hand, dis-engaging interdependence is characterized as ‘rejection avoidance’ to try to confirm qualification of informal membership in a given social group by following the group norm and informal rules. It is not voluntary adaptation for the group, but motivated to avoid being ostracized by other group members. Hence, collectivistic but not harmonious.

Of these categories, dis-engaging inter-dependence may be deeply related to MTD and also hikikomori. Patients with MTD tend to avoid many interpersonal relationships because they are so afraid of being hurt and humiliated by others. They are always scared of potential psychological attack from others. In particular, hikikomori persons do not want to leave their homes. For them, their family is the only group that they are convinced will not hurt them. This is consistent with the characteristics of dis-engaging interdependence. Although an empirical demonstration has yet to be carried out, it would be plausible to consider MTD patients as having much higher levels of dis-engaging inter-dependence than normal and healthy people. According to Hashimoto and Yamagishi,53,54 comparing student samples from the USA and Japan, the Japanese showed significantly higher scores on dis-engaging inter-dependence than Americans. This may be indirect evidence that it can be related to MTD because currently MTD is frequently observed among youth in Japan. Interestingly, a recent review article by Li and Wong has indicated the interaction between hikikomori and inter-dependence.55 It is necessary to conduct systematic empirical research to investigate the relationship (and/or causality) between MTD and dis-engaging inter-dependence.

Biological Factors

While the biological foundation of MTD is unknown, some specific biological mechanisms are worth speculation. The frequently observed clinical viewpoint that treatment with only the standard pharmacological therapies for depression is not successful for patients with MTD has strongly suggested that a different biological mechanism from traditional depression may exist in the biological features of MTD.

Abnormal function of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis has long been proposed as a candidate biological foundation of depression.56 A number of studies using the dexamethasone (DEX)/corticotrophin-releasing hormone (CRH) test have been conducted for the assessment of HPA axis function in patients with depression, while these outcomes have been inconsistent.57 The inconsistency may result from the heterogeneity of depression. Hori et al. have reported key findings in elucidating the heterogeneity of depression using the DEX/CRH test and the Temperament and Character Inventory in patients with MDD.58 MDD patients with high cooperativeness showed exaggerated cortisol reactivity; on the contrary, patients with low cooperativeness and high reward dependence showed blunted cortisol reactivity.58 In addition, Hori et al. revealed that MDD patients with escape-avoidance coping showed blunted cortisol reactivity.59 On the other hand, schizotypal personality traits60 and low novelty-seeking with harm avoidance61 in healthy adults are reported to be correlated with exaggerated cortisol reactivity, which proposes the possibility that functions of the HPA axis differ with character and temperament. Low cooperativeness and escape-avoidance coping coincide with the features of MTD, thus the biological foundation of MTD may, at least to some extent, result from abnormal functions of the HPA axis. While not MTD, abnormal function of the HPA axis (abnormal cortisol reactivity in DEX/CRH test) has also been observed in patients with borderline personality disorder62 and atypical depression.63 Based on the above data, Kunugi et al. has recently proposed a classification of depression focusing on the HPA axis functions.64

Interestingly, a recent clinical research regarding atypical depression has suggested a significantly higher comorbidity with metabolic syndrome.65 Metabolic syndrome has recently been suggested to be related to oxidative stress and inflammation.66 Our pilot study has indicated a correlation between serum proinflammatory cytokines and depressive symptoms/personality traits in Japanese university students (unpub. data). We propose an inflammation hypothesis of psychiatric diseases, including depression, via microglia, brain immune cells.67–71 These data may suggest that inflammation and oxidative stress may link to MTD. Further translational studies are needed to clarify the biological foundation of MTD.

Therapeutic Approach

No systematic data have been reported regarding therapeutic interventions of MTD. While our previous case vignette survey has suggested that both psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy were recommended to treat MTD, psychotherapy was especially preferred by psychiatrists in all countries.4 Interestingly, Japanese psychiatrists seemed to hesitate to recommend pharmacotherapy for MTD. In addition, some Japanese psychiatrists hesitated to treat MTD at all. These data have indicated that Japanese psychiatrists, at least to some extent, regard MTD as a non-medical condition. This was in contrast to most psychiatrists in other countries endorsing the need for active treatments to MTD.4 Why is there a discrepancy in psychiatrists’ attitudes toward MTD? These findings may suggest that Japanese psychiatrists themselves are bound to their own socio-cultural and historical contexts.4

The arrival of new antidepressants to Japan in 1999 has also been suggested to have influenced the public view toward depression,72 and may have led to a similar phenomenon occurring in Western countries.73 Previously, depressed persons had tended to hesitate to visit psychiatrists, and Japanese psychiatrists had tended to equate depression only with the traditional melancholic type. Perhaps with the introduction of public awareness campaigns for depression and antidepressants, people who considered themselves depressed began to feel less self-conscious about visiting psychiatrists. This may have been a contributing factor leading to increasing numbers of visits of depressed persons to psychiatrists in Japan.4 However, as the case vignette survey implies, this popular shift has not been accompanied by similar changes in the perception of Japanese psychiatrists, who have very much remained deeply bound to earlier, more traditional conceptions of depression. On the other hand, the results of the case vignette survey indicate that psychotherapy was regarded to be of importance for MTD patients with Japanese psychiatrists who did not see a role for pharmacotherapy.4 Therefore, public education about depression and psychotherapy as a treatment should also be considered as one of the possible solutions to alleviate this discrepancy between the general population and psychiatrists in Japan.

Therapeutic strategies regarding MTD based on pathophysiological understandings should be established. We hypothesize that child and adolescent development has been impacted by rapid environmental changes, which may cause the novel phenomenon. The ways of ‘playing’ among children and adolescents have dramatically shifted from ‘direct playing’ (direct communication in a physical space, such as outdoors or in parks) to ‘indirect playing’ (indirect virtual communication via video games and Internet-related materials) within the past decades.36 People who have grown up in such new environments may become confused and depressed when they enter the traditional workforce and encounter the need for real direct communication. Therefore, psychoeducation and (group) psychotherapy may be the recommended approaches in order to develop skills of direct communication, which may lead to a smoother adjustment to adult communication environments. In addition, pharmacological and social approaches may also be effective. Clinical research to measure therapeutic responses should be performed to dig up the appropriate intervention.

How to Solve the Issues Associated with MTD

Blind-spots of the DSM system

Recently, early-career psychiatrists in Japan have considered that it is possible to make diagnoses based solely on the abbreviated pocket-sized DSM-IV-TR. This book, entitled the Quick Reference to the Diagnostic Criteria from DSM-IV-TR,3 states that it is intended to be used in combination with the unabridged version of the DSM-IV-TR (which is 900+ pages in length).74 In fact, the DSM-IV-TR also states in an introductory section entitled ‘Cautionary Statement’ that ‘the proper use of these criteria requires specialized clinical training that provides both body of knowledge and clinical skills.’ Many early-career psychiatrists seem to be unaware of these facts. The DSM-IV-TR includes detailed explanations of diagnostic criteria, diagnostic features, and differential diagnoses for each disorder. However, even in the unabridged version, there is no mention of which examinations should be performed in the garnering of information for each disorder. This can only be achieved through not only reading of psychiatric textbooks but also the accumulation of real clinical experiences with supervisory psychiatrists involving the joint examination of patients in a hospital/clinic setting. However, in reality, early-career psychiatrists who are actually willing to accumulate such valuable experiences are on the decline. In addition, there are some problems based on the nature of operational diagnosis in DSM. Parker indicated that operational criteria of the depression dimensional model in DSM has made it easy to diagnose depression, and also resulted in loose diagnostic practice blunting clarification of causes and treatment specificity of depression.75

On the other hand, the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) is considered the best available method for diagnosis of psychiatric disorders, but in reality there are limitations to its applicability. When applying the systematic diagnostic criteria for MDD based on the DSM-IV (and also DSM-5), whilst being relevant, a difficulty arises when strictly applying the criteria. In particular, within the definition of MDD, a continuous depressed mood of more than 2 weeks is one of the criteria for diagnosis, and in reality it is difficult to judge whether this criteria has been met for this continuous period for almost every day for 2 weeks. Furthermore, ambiguity exists regarding the extent at which ‘continuous’ may be defined. In MTD, depressive symptoms are exhibited at work or at school but during weekend rest times or when at home these symptoms are not exhibited. In such cases, are the DSM criteria of ‘for more than 2 weeks’ met? Depending on the psychiatrist, there are those who would diagnose MDD and others who would not. In Japanese clinical settings, for such cases and similar cases where symptoms are even less frequent, there is still a high probability that a diagnosis of MDD will eventuate.

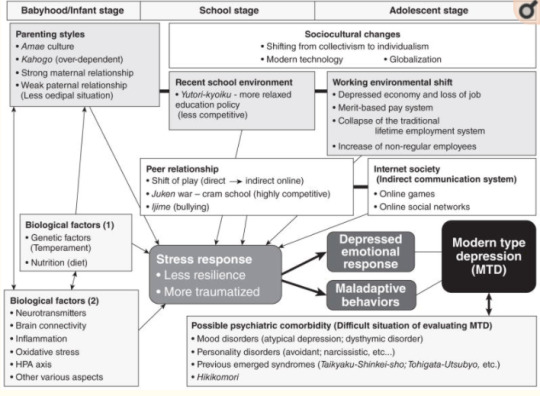

Proposing a novel diagnostic approach to depression

The greatest difficulty in the evaluation and diagnosis of depression is the gap between subjective patient symptoms and objective realities. It is a well-known given among experienced psychiatrists that information garnered from the individual only is not enough in the diagnosis of depression. Information regarding psychiatric symptoms from an individual is no more than ‘subjective symptoms’ and in many cases differs from objective realities. It is particularly difficult for inexperienced psychiatrists to reach a diagnosis for depression based on information garnered solely from the individual but it is also often the case that treatment is commenced without understanding this reality. Moreover, it is important to note that recently not only psychiatrists but also physicians are diagnosing depression and tend to prescribe antidepressants. In order to improve this situation, changes must be made to allow for a more detailed assessment of the individual’s situation. Along with the individual, the collection of information from family members and other third parties is incredibly important (Fig. 2). When an individual claims to be depressed, an objective assessment is required that cannot be limited to the individual. Because of this, when the only obtainable information is from the individual, a diagnosis of ‘possible’ depression may be preferable. This aspect has not been included in many guidelines of depression; however, it must be of great importance, especially in diagnosing MTD.

Figure 2. Multi-axial assessments of modern type depression (MTD). In order to evaluate MTD, we recommend utilizing the 1–6 assessment methods directly to depressed persons. In addition, information from others is essential to evaluate such persons. Objective biomarkers of MTD have not been developed until now. Some biomarkers of MTD may overlap with major depressive disorder and other psychiatric diagnosis/syndromes, while some data from brain imaging/neurophysiological analysis and peripheral blood analysis may help to distinguish MTD from other psychiatric conditions. Further investigations should be developed to dig up such biomarkers. CRH, corticotrophin-releasing hormone; DEX, dexamethasone; DTI, diffusion tensor imaging; EEG, electroencephalography; HAM-D, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; fMRI, functional magnetic resonance imaging; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; MRS, magnetic resonance spectroscopy; PET, positron emission tomography; SCID, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV; TCI, Temperament and Character Inventory.

Using a three-tier diagnostic system (possible/probable/definite)

Here, we propose a novel criteria that can make evaluation/diagnosis of depression understandable even for less experienced psychiatrists.76 Along the lines of a diagnostic system for many physical illnesses (cancer, etc ) and dementia, we propose that diagnosis of depression should be divided into the three tiers of ‘possible,’ ‘probable’ and ‘definite.’ The first tier (possible) would be ‘diagnosis based on information from the subject only,’ the second tier (probable) would be ‘diagnosis based on the information from the subject and other sources (family or colleagues, etc.),’ and the third tier (definite) would be ‘diagnosis based on information from the subject + (family, colleagues, etc.) + (intensive clinical examination during outpatient clinic and/or hospitalization).’ Furthermore, we believe that each tier should have a different treatment guideline.77 By utilizing this novel diagnostic system, we can avoid the tendency to overdiagnose depression in persons with MTD tendencies (Fig. 2).

Investigating research into adjunctive measures, such as economic games

In addition, economic games, such as the trust game, have been utilized to evaluate real-world interpersonal relationships as a novel candidate for psychiatric evaluations. Economic games have been developed in the field of social psychology and economics, and have been proposed as a novel tool for evaluating interpersonal psychiatric problems. Clinical studies using economic games (prisoner’s dilemma, the public goods game, the ultimatum game and the trust game) have revealed some difficulties of social decision-making in individuals with MDD and personality disorders.77–80 The trust game, an economic game, has been widely used to evaluate a person’s trust toward others.81 In this two-person game, the first player has to make a risky financial decision depending on how much s/he would trust the second player (partner). Recent studies have examined whether other factors, such as personality and psychiatric conditions, influence trusting behaviors and cooperation.79,80,82–84 As a pilot study, we recently conducted a trust game experiment with 81 Japanese university students.85 Clinical case reports have indicated that people with MTD and hikikomori have difficulties in developing trust among family members, and colleagues in schools and working places.86–88 Therefore, a common feature of modern psychiatric syndromes may be induced through difficulty in trusting others, and these features may not be limited to patients but also to the wider contemporary populations, especially the young. In the economic experiment, participants made a risky financial decision about whether to trust each of 40 photographed partners.85 Participants then answered a set of questionnaires, including the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)-9. Regression analysis revealed that item 8 of the PHQ-9 (subjective agitation and/or retardation) for female participants was associated with participants’ trusting behaviors. Women with higher subjective agitation (and/or retardation) gave less money to men and highly attractive women, but more to less attractive women in interpersonal relationships. This indicates that women with high subjective agitation may tend to make more defensive and cautious decisions in daily life, which may cause difficulties in various social interactions. These data indicate the possible impact of economic games in psychiatric research and clinical practice, including MTD, and further validation should be investigated.

Conclusion

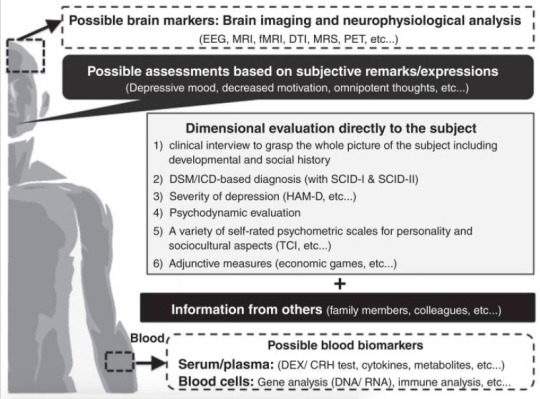

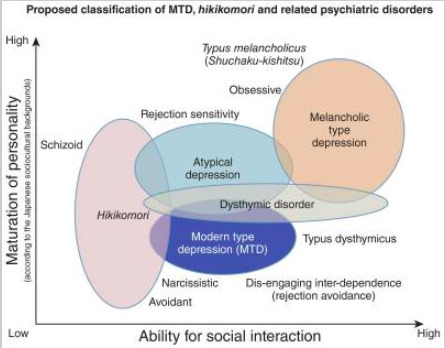

In this review paper, we introduced MTD, citing the few scientific reports available and offered our collective experiences and perspectives on its diagnosis and treatment. In Japan, MTD refers to a syndrome with predominant symptoms of depression and withdrawal that has rapidly increased among youth since around 2000. It is worth recalling that the phenotype of mental illness – be it the appearance of late-19th century hysteria, the appearance of post-1950 eating disorders, or post-1970 borderline personality disorders – is transforming along with society. Despite the lack of agreement upon diagnostic criteria of MTD, it may be considered that cultural, social, and biological factors are all involved in its development and Japanese cultural and social influences may be creating MTD (Fig. 1). In Japan, along with MTD, social withdrawal syndrome (i.e. hikikomori) is concurrently prevalent amongst youth and is considered a great social problem. We hypothesize that the onset of MTD and a prolonged maladaptive social situation may be one of the causal factors of hikikomori. As we may consider ‘withdrawal/avoidance’ to be a common factor in both syndromes, further research regarding shared psychopathology and risk factors in modern society is necessary. We believe that combating MTD may also rescue hikikomori. Differentiation of MTD from other psychiatric disorders has not been established under the present situation, while we have newly classified MTD and related psychiatric disorders (syndromes) from the following two aspects: maturation of personality and ability for social interaction (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Proposed classification of modern type depression (MTD), hikikomori and related psychiatric disorders. Based on the maturation of personality and ability of social interaction, we have classified the five psychiatric disorders (syndromes), including MTD and hikikomori. The level of personality maturation in this figure is based on the Japanese sociocultural contexts. In Japan, melancholic personality (Typus melancholicus or Shūchaku-kishitsu) has long been regarded as matured personality, while this perspective may not be applied in other countries with different sociocultural backgrounds.

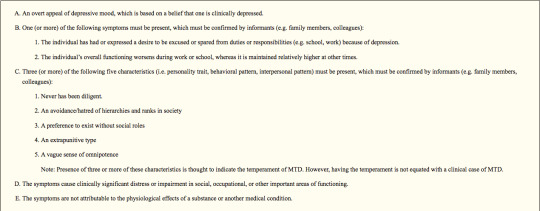

We have suggested the necessity for the introduction of novel methods of evaluation, not only limited to the diagnosis of MTD but to depressive disorders in general, as we consider the modern usage of psychiatric tools that rely on subjective claims by patients to be insufficient. In particular, we recommend the addition of: third-party evaluations to the diagnostic criteria; the usage of economic game experiments and the like; and the evaluation of actual behavioral characteristics. It is hoped that through the introduction of these tools, a more accurate diagnosis of depressive disorders will become possible. The development of a new multi-axial evaluation and diagnostic tool that incorporates such new tools is required (Fig. 2). As the nosology of MTD has not been validated, we need to keep in mind that the presented data shown in the ‘biological factors’ and ‘therapeutic approach’ sections does not directly provide the findings of MTD (mixed with issues regarding major depression in general). In order to advance MTD research, we have proposed research-based draft operational criteria for MTD (Table 2). The draft operational criteria are limited to research use at the present stage. We hope that in the near future, a breakthrough diagnostic and treatment methodology for MTD will be developed based on these draft criteria.

Table 2. Proposed research-based operational criteria and intervention for ‘modern type depression (MTD)’: Provisional –recommended only for research use.

In order to advance MTD research, MTD should be defined with more systematic methodology. Thus, we herein propose operational criteria for MTD based on the present knowledge of MTD. The draft operational criteria are for research use at the present stage. Based on research with the draft criteria, clinically useful operational criteria should be developed in the near future. Of note, five components are listed as representative of MTD in Item C. In order to evaluate the temperament of MTD, the person must be comprehensively assessed, including personality, development, life history and present status. In order to help conduct the assessment more efficiently, a self-report questionnaire (‘MTD-trait scale’) for evaluation of MTD temperament is being developed (Kato et al. unpub. material). HAM-D, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; MDD, major depressive disorder; MTD, modern type depression.

References

1. Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960; 23:56–62. [PubMed: 14399272]

2. Furukawa TA, Streiner DL, Azuma H, et al. Cross-cultural equivalence in depression assessment: Japan-Europe-North American study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2005; 112:279–285. [PubMed: 16156835]

3. American Psychiatric Publishing. Quick Reference to the Diagnostic Criteria from DSM-IV-TR. American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; Arlington, VA: 2000.

4. Kato TA, Shinfuku N, Fujisawa D, et al. Introducing the concept of modern depression in Japan: An international case vignette survey. J Affect Disord. 2011; 135:66–76. [PubMed: 21782250]

5. Tarumi S, Kanba S. Sociocultural approach toward depression – Dysthymic type depression. Jpn Bull Soc Psychiatr. 2005; 13:129–136. (in Japanese).

6. Tarumi S. The ‘new’ variant of depression: The dysthymic type. Jpn J Clin Psychiatr. 2005; 34:687– 694. (in Japanese).

7. Benazzi F. Testing atypical depression definitions. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2005; 14:82–91. [PubMed: 16175877]

8. Blanco C, Vesga-Lopez O, Stewart JW, Liu SM, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Epidemiology of major depression with atypical features: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). J Clin Psychiatry. 2012; 73:224–232. [PubMed: 21939615]

9. Akiskal HS, Akiskal KK, Perugi G, Toni C, Ruffolo G, Tusini G. Bipolar II and anxious reactive ‘comorbidity’: Toward better phenotypic characterization suitable for genotyping. J Affect Disord. 2006; 96:239–247. [PubMed: 16973219]

10. Shimoda M. On the treatment of involutional depression in my department. Taiwan Igaku Zasshi. 1932; 31:113–115. (in Japanese).

11. Tellenbach, H. Melancholie. Springer; Berlin: 1961.

12. Walters, PA, Jr. Student apathy. In: Blame, GB., Jr, McArthur, CC., editors. Emotional problems of the student. Appleton-Century-Crofts; New York: 1961. p. 129-147.

13. Kasahara Y, Kimura B. Utsu-byo no rinshoteki-bunrui ni kansuru kenkyu. Seishin Shinkeigaku Zasshi. 1975; 77:715–735. (in Japanese). [PubMed: 1243687]

14. Hirose, T. Tohi-gata utsu-byo ni tsuite. In: Miyamoto, T., editor. Sou-utsu-byo no seishin-byori 2 [Psychopathology of Manic-Depressive Illness 2]. Kobundo, Tokyo: 1977. p. 61-86.

15. Matsunami K, Yamashita Y. Syakai-hendo to utsu-byo [Social changes and depression]. Jpn Bull Soc Psychiatr. 1991; 14:193–200. (in Japanese).

16. Abe T, Otsuka K, Nagano M, Kato S, Miyamoto T. A consideration on ‘Immature Type of Depression’: Premorbid personalities and clinical pictures of depression from the structural- dynamic viewpoint (W. Janzarik). Jpn Clin Psychopathol. 1995; 16:239–248. (in Japanese).

17. Klein DF, Liebowitz MR. Hysteroid dysphoria. Am J Psychiatry. 1982; 139:1520–1521. [PubMed: 7137409]

18. Kato TA, Shinfuku N, Sartorius N, Kanba S. Are Japan’s hikikomori and depression in young people spreading abroad? Lancet. 2011; 378:1070. [PubMed: 21924990]

19. Shimoda M. Shuchaku-kishitsu ni tsuite. Yonago Igaku Zasshi. 1950; 2:1–2. (in Japanese).

20. Kanba S. Modern interpretation of Shimoda’s shuchaku-kishitsu. Kyushu Neuro-Psychiatry. 2006; 52:79–88. (in Japanese).

21. Ohmae S. The modern concept of atypical depression: Four definitions. Seishin Shinkeigaku Zasshi. 2010; 112:3–22. (in Japanese). [PubMed: 20184236]

22. American Psychiatric Publishing. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5. American Psychiatric Publishing; Arlington, VA: 2013.

Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2017 August 17.

VA Author Manuscript VA Author Manuscript VA Author Manuscript

Kato et al.

Page 16

23. Akiskal HS. Dysthymic disorder: Psychopathology of proposed chronic depressive subtypes. Am J Psychiatry. 1983; 140:11–20. [PubMed: 6336637]

24. Hirose T. Depression of avoidant type compared with depression of dysthymic type. Jpn J Clin Psychiatr. 2008; 37:1179–1182. (in Japanese).

25. Abe T. Depression from the viewpoint of life stage: Diagnosis and treatment. Jpn J Psychosom Med. 2009; 49:987–993. (in Japanese).

26. Nitobe, I. Bushido: The Soul of Japan. G. P. Putnam’s Sons; New York: 1906.

27. Benedict, RF. The Chrysanthemum and the Sword: Patterns of Japanese Culture. Houghton Mifflin; Boston, MA: 1946.

28. Doi, T. The Anatomy of Dependence. Kodensha International; Tokyo: 1973.

29. Furukawa T, Nakanishi M, Hamanaka T. Typus melancholicus is not the premorbid personality trait of unipolar (endogenous) depression. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1997; 51:197–202. [PubMed: 9316163]

30. Kanba S, Kano R, Eguchi S, Utsumi T, Abe T. Has the prototype of depression been shifted? Jpn J Clin Psychiatr. 2008; 37:1091–1109. (in Japanese).

31. Kotov R, Gamez W, Schmidt F, Watson D. Linking ‘big’ personality traits to anxiety, depressive, and substance use disorders: A meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2010; 136:768–821. [PubMed: 20804236]

32. Watson D, Clark LA. Depression and the melancholic temperament. Eur J Pers. 1995; 9:351–366.

33. Klein DN, Shankman SA, Rose S. Ten-year prospective follow-up study of the naturalistic course of dysthymic disorder and double depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2006; 163:872–880. [PubMed: 16648329]

34. Tseng, WS. Handbook of Cultural Psychiatry. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 2001.

35. Alarcon RD. Culture, cultural factors and psychiatric diagnosis: Review and projections. World Psychiatry. 2009; 8:131–139. [PubMed: 19812742]

36. Ogata Y, Izumi Y, Kitaike T. Mobile-phone e-mail use, social networks, and loneliness among Japanese high school students. Nippon Koshu Eisei Zasshi. 2006; 53:480–492. (in Japanese). [PubMed: 16944832]

37. Watabe, M. Social exchange; transition from ‘embedded long-term relationships’ to ‘voluntary short-term relationships’. In: Hibino, A.Watabe, M., Ishii, K., editors. Disconnected Society (Tsunagarenai Shakai). Nakanishiya, Kyoto: 2014.

38. Hatcher S, Stubbersfield O. Sense of belonging and suicide: A systematic review. Can J Psychiatry. 2013; 58:432–436. [PubMed: 23870726]

39. Kim SY, Kim MH, Kawachi I, Cho Y. Comparative epidemiology of suicide sin South Korea and Japan: Effects of age, gender and suicide methods. Crisis. 2011; 32:5–14. [PubMed: 21371965]

40. Takahashi, K., Kawai, D., Nagata, M., Watabe, M. Fukigen na shokuba [Unpleasant Workplace]. Kodansha, Tokyo: 2008.

41. Kato TA, Tateno M, Shinfuku N, et al. Does the ‘hikikomori’ syndrome of social withdrawal exist outside Japan? A preliminary international investigation. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012; 47:1061–1075. [PubMed: 21706238]

42. Niiya Y, Ellsworth PC, Yamaguchi S. Amae in Japan and the United States: An exploration of a ‘culturally unique’ emotion. Emotion. 2006; 6:279–295. [PubMed: 16768560]

43. Teo AR, Stufflebam K, Saha S, et al. Psychopathology associated with social withdrawal: Idiopathic and comorbid presentations. Psychiatry Res. 2015; 228:182–183. [PubMed: 25977071]

44. Teo AR, Fetters MD, Stufflebam K, et al. Identification of the hikikomori syndrome of social withdrawal: Psychosocial features and treatment preferences in four countries. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2015; 61:64–72. [PubMed: 24869848]

45. Heine, SJ. Cultural Psychology. W. W. Norton & Company; New York: 2011.

46. Yamagishi, T. Trust – The Evolutionary Game of Mind and Society. Springer Tokyo; Tokyo: 2011. 47. Yamagishi T, Cook KS, Watabe M. Uncertainty, trust, and commitment formation in the United

States and Japan. Am J Sociol. 1998; 104:165–194.

48. Cross SE, Hardin EE, Gercek-Swing B. The what, how, why, and where of self-construal. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2011; 15:142–179. [PubMed: 20716643]

49. Markus HR, Kitayama S. Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychol Rev. 1991; 98:224–253.

50. Oyserman D, Coon HM, Kemmelmeier M. Rethinking individualism and collectivism: Evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analyses. Psychol Bull. 2002; 128:3–72. [PubMed: 11843547]

51. Matsumoto D. Culture and self: An empirical assessment of Markus and Kitayama’s theory of independent and interdependent self-construals. Asian J Soc Psychol. 1999; 2:289–310.

52. Levine TR, Bresnahan MJ, Park HS, et al. Self-construal scales lack validity. Hum Commun Res. 2003; 29:210–252.

53. Hashimoto, H., Yamagishi, T. Center for the Study of Cultural and Ecological Foundations of the Mind Working Paper Series. Hokkaido University; 2014. Engaging and disengaging aspects of independence and interdependence: An adaptationist perspective.

54. Hashimoto H, Yamagishi T. Two faces of interdependence: Harmony seeking and rejection avoidance. Asian J Soc Psychol. 2013; 16:142–151.

55. Li TM, Wong PW. Youth social withdrawal behavior (hikikomori): A systematic review of qualitative and quantitative studies. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2015; 49:595–609. [PubMed: 25861794]

56. Holsboer F. The corticosteroid receptor hypothesis of depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000; 23:477–501. [PubMed: 11027914]

57. Holsboer F, von Bardeleben U, Wiedemann K, Muller OA, Stalla GK. Serial assessment of corticotropin-releasing hormone response after dexamethasone in depression. Implications for pathophysiology of DST nonsuppression. Biol Psychiatry. 1987; 22:228–234. [PubMed: 3028512]

58. Hori H, Teraishi T, Sasayama D, et al. Relationship of temperament and character with cortisol reactivity to the combined dexamethasone/CRH test in depressed outpatients. J Affect Disord. 2013; 147:128–136. [PubMed: 23178186]

59. Hori H, Teraishi T, Ota M, et al. Psychological coping in depressed outpatients: Association with cortisol response to the combined dexamethasone/CRH test. J Affect Disord. 2014; 152–154:441– 447.

60. Hori H, Teraishi T, Ozeki Y, et al. Schizotypal personality in healthy adults is related to blunted cortisol responses to the combined dexamethasone/corticotropin-releasing hormone test. Neuropsychobiology. 2011; 63:232–241. [PubMed: 21494051]

61. Tyrka AR, Wier LM, Price LH, et al. Cortisol and ACTH responses to the Dex/CRH test: Influence of temperament. Horm Behav. 2008; 53:518–525. [PubMed: 18294637]

62. Rinne T, de Kloet ER, Wouters L, Goekoop JG, DeRijk RH, van den Brink W. Hyperresponsiveness of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis to combined dexamethasone/ corticotropin-releasing hormone challenge in female borderline personality disorder subjects with a history of sustained childhood abuse. Biol Psychiatry. 2002; 52:1102–1112. [PubMed: 12460693]

63. Gold PW, Chrousos GP. The endocrinology of melancholic and atypical depression: Relation to neurocircuitry and somatic consequences. Proc Assoc Am Physicians. 1999; 111:22–34. [PubMed: 9893154]

64. Kunugi H, Hori H, Ogawa S. Biochemical markers subtyping major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2015; 69:597–608. [PubMed: 25825158]

65. Takeuchi T, Nakao M, Kachi Y, Yano E. Association of metabolic syndrome with atypical features of depression in Japanese people. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013; 67:532–539. [PubMed: 24152284]

66. Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature. 2006; 444:860–867. [PubMed: 17167474]

67. Horikawa H, Kato TA, Mizoguchi Y, et al. Inhibitory effects of SSRIs on IFN-gamma induced microglial activation through the regulation of intracellular calcium. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2010; 34:1306–1316. [PubMed: 20654672]

68. Kato TA, Monji A, Mizoguchi Y, et al. Anti-inflammatory properties of antipsychotics via microglia modulations: Are antipsychotics a ‘fire extinguisher’ in the brain of schizophrenia? Mini Rev Med Chem. 2011; 11:565–574. [PubMed: 21699487]

69. Kato TA, Yamauchi Y, Horikawa H, et al. Neurotransmitters, psychotropic drugs and microglia: Clinical implications for psychiatry. Curr Med Chem. 2013; 20:331–344. [PubMed: 23157624]

70. Mizoguchi Y, Kato TA, Seki Y, et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) induces sustained intracellular Ca2+ elevation through the up-regulation of surface transient receptor potential 3 (TRPC3) channels in rodent microglia. J Biol Chem. 2014; 289:18549–18555. [PubMed: 24811179]

71. Monji A, Kato T, Kanba S. Cytokines and schizophrenia: Microglia hypothesis of schizophrenia. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2009; 63:257–265. [PubMed: 19579286]

72. Schulz, K. New York Times. 2004. Did antidepressants depress Japan?.

73. Healy, D. The Antidepressant Era. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1997.

74. American Psychiatric Publishing. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. American Psychiatric Publishing; Arlington, VA: 2000. text rev

75. Parker G. Is depression overdiagnosed? Yes. BMJ. 2007; 335:328. [PubMed: 17703040]

76. Hashimoto R, Yasuda Y, Yamamori H, et al. Is it possible to make a diagnosis of major depression based solely on the medical interview of the patient? Seishinka. 2013; 22:243–249.

77. Wang Y, Zhou Y, Li S, Wang P, Wu GW, Liu ZN. Impaired social decision making in patients with major depressive disorder. BMC Psychiatry. 2014; 14:18. [PubMed: 24450703]

78. Zhang HJ, Sun D, Lee TM. Impaired social decision making in patients with major depressive disorder. Brain Behav. 2012; 2:415–423. [PubMed: 22950045]

79. Brendan Clark C, Thorne CB, Hardy S, Cropsey KL. Cooperation and depressive symptoms. J Affect Disord. 2013; 150:1184–1187. [PubMed: 23726777]

80. King-Casas B, Sharp C, Lomax-Bream L, Lohrenz T, Fonagy P, Montague PR. The rupture and repair of cooperation in borderline personality disorder. Science. 2008; 321:806–810. [PubMed: 18687957]

81. Berg J, Dickhaut J, McCabe K. Trust, reciprocity, and social history. Games Econ Behav. 1995; 10:122–142.

82. Chiu PH, Kayali MA, Kishida KT, et al. Self responses along cingulate cortex reveal quantitative neural phenotype for high-functioning autism. Neuron. 2008; 57:463–473. [PubMed: 18255038]

83. Kato TA, Watabe M, Tsuboi S, et al. Minocycline modulates human social decision-making: Possible impact of microglia on personality-oriented social behaviors. PLoS ONE. 2012; 7:e40461. [PubMed: 22808165]

84. Watabe M, Kato TA, Monji A, Horikawa H, Kanba S. Does minocycline, an antibiotic with inhibitory effects on microglial activation, sharpen a sense of trust in social interaction? Psychopharmacology. 2012; 220:551–557. [PubMed: 21956241]

85. Watabe M, Kato TA, Teo AR, et al. Relationship between trusting behaviors and psychometrics associated with social network and depression among young generation: A pilot study. PLoS ONE. 2015; 10:e0120183. [PubMed: 25836972]

86. Nakano M. How supervisors deal with subordinates who have characteristics of ‘new-type depression’. Rinsho-Shinrigaku. 2014; 14:235–243.

87. Tsujii H, Natsuhori K, Uozumi E. Nursing care for an adolescent hikikomori case with domestic violence: A case report. Nihon Seishinka Kangogaku Kaishi. 2010; 52:72–76.

88. Nakagama H. Integration of individual and family conjoint interview: A case study of a social withdrawal adolescent and his family members. Kazoku-Shinrigaku-Kenkyu. 2008; 22:28–41.

#psychiatry#global psychiatry#cross-cultural psychiatry#atypical depression#mental illness#DSM-5#depression#major depressive disorder#shūchaku-kishitsu#diagnosis#diagnostic symptoms#modern type depression#dysthymia#classification#hikikomori

1 note

·

View note

Text

a dissertation nobody asked for, ft. my dysphoric trans ass (on the subject of truscum, cisgender medicine, and stupid assholes)

BOY HOWDY DID THIS GET LONG

I know that nobody asked for this post, and definitely nobody needed it, but you know what? Fuck it. You’re getting this post anyway.

Very recently someone in the community outed himself (himself, because I’m aware that he uses he/him pronouns and am not a piece of shit who will misgender someone under guise of offering anonymity. Cough cough.) as a transmedicalist. A truscum, if you will, because we all know that they mean the same thing and anyone who tries to convince you otherwise is a bitchcoward and a bigot.

Very disappointing, yes, considering the amount of transgender people* I know exist in this community, myself included. Disappointing, frightening, and rage-inducing. Particularly because this revelation followed an encounter said truscum had with a close friend of mine. Which I admit might make me a little biased but shhh. Neither me nor my friend(s) started this. The contents of that conversation had between the truscum and my bro should have been handled privately like an adult but- hey, since we’re putting all this shit out there now, guess I get to put in my two cents! Awesome!

And because we apparently like to bring science into shit, let’s get a lil scientific up in this bitch.

*Note: transgender from here on will be used to refer to as the umbrella of non-cis gender identities just for context and ease of reference. And also because that’s what it is, fuck off.

So, guys. Let’s talk about dysphoria.

PART 1. SEMANTICS

Dysphoria. Most of you have heard of it, particularly those among us (both within and outside of the fantroll community) who happen to be transgender.

But what does it actually mean? Let’s look a little closer. Dysphoria, as defined by Merriam-Webster:

dysphoria (noun)

dys·pho·ria | \ dis-ˈfȯr-ē-ə \

Definition of dysphoria

: a state of feeling very unhappy, uneasy, or dissatisfied

— see GENDER DYSPHORIA

But this is just semantics. Let’s look at it, and gender oriented dysphoria in particular from a mental health perspective-

“Gender dysphoria is the feeling of discomfort or distress that might accompany a difference between gender identity, sex assigned at birth or sex-related physical characteristics. This type of distress doesn't affect everyone who is transgender.

Gender dysphoria is listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), a manual published by the American Psychiatric Association to diagnose mental conditions. Gender dysphoria is a diagnosis that is given to individuals who are experiencing discomfort or distress due to the difference between gender identity, sex assigned at birth or sex-related physical characteristics.”

This is from the Mayo Clinic, a nonprofit academic medical center based in Rochester, Minnesota, lauded as the best hospital in the nation for 2018-2019 by the U.S News and World Report. Do with that information what you will, but most would consider the Mayo Clinic (while not a good replacement for proper doctor’s visits and medical treatment) a pretty credible health resource.

But we’ll come back to this.

For now, let’s look at another definition. That of the word ‘opinion.’

PART 2: FACTS VS. OPINIONS VS. BELIEFS VS. PREJUDICE

opinion (noun)

opin·ion | \ ə-ˈpin-yən \

Definition of opinion

1a : a view, judgment, or appraisal formed in the mind about a particular matter

We asked them for their opinions about the new stadium.

b : APPROVAL, ESTEEM

I have no great opinion of his work.

2a : belief stronger than impression and less strong than positive knowledge

a person of rigid opinions

Opinions are inherently biased. It may be influenced by facts, but opinions in and of themselves are not fact. To borrow and paraphrase from Fowler, H. Ramsey. The Little, Brown Handbook. Boston: Little, Brown, 1986.:

When forming personal convictions, we often interpret factual evidence through the filter of our values, feelings, tastes, and past experiences. Hence, most statements we make in speaking and writing are assertions of fact, opinion, belief, or prejudice. The usefulness and acceptability of an assertion can be improved or diminished by the nature of the assertion, depending on which of the following categories it falls into:

A fact is verifiable. [Determinable by] ...researching the evidence. This may involve numbers, dates, testimony, etc. (Ex.: "World War II ended in 1945.") The truth of the fact is beyond argument if one can assume that measuring devices or records or memories are correct. Facts provide crucial support for the assertion of an argument. However, facts by themselves are worthless unless we put them in context, draw conclusions, and, thus, give them meaning.

An opinion is a judgment based on facts, an honest attempt to draw a reasonable conclusion from factual evidence. [Opinions are] potentially changeable--depending on how the evidence is interpreted. By themselves, opinions have little power to convince. You must always let your reader know what your evidence is and how it led you to arrive at your opinion.

Unlike an opinion, a belief is a conviction based on cultural or personal faith, morality, or values. Statements such as "Capital punishment is legalized murder" are often called "opinions" because they express viewpoints, but they are not based on facts or other evidence. They cannot be disproved or even contested in a rational or logical manner. Since beliefs are inarguable, they cannot serve as the thesis of a formal argument. (Emotional appeals can, of course, be useful if you happen to know that your audience shares those beliefs.)

Y’all get what I’m getting at, right?

Oh, but one more thing I’d like to add- And I think this one is important.

“Another kind of assertion that has no place in serious argumentation is prejudice, a half-baked opinion based on insufficient or unexamined evidence. (Ex.: "Women are bad drivers.") Unlike a belief, a prejudice is testable: it can be contested and disproved on the basis of facts. We often form prejudices or accept them from others--family, friends, the media, etc.--without questioning their meaning or testing their truth. At best, prejudices are careless oversimplifications. At worst, they reflect a narrow-minded view of the world. Most of all, they are not likely to win the confidence or agreement of your readers.”

We’ve all encountered our fair share of these sorts of prejudices, disguised as “opinions.” Because isn’t that a much sweeter word for what it is? It’s not bigotry to delegitimize the experiences of other transgender people, it’s just an opinion. Like which is the best ice cream flavour, or something equally harmless.

But when your opinion involves the dehumanization, invalidation, exclusion and harm of other people… Well, that’s not so harmless, is it?

Racism is prejudice influenced by opinions and beliefs. Transphobia is prejudice influenced by opinions and beliefs. They are not fact, they are not based in rational thinking, and in many cases they cannot be argued because these prejudices are willingly cultivated and held.

‘But, Eli!’ I know at least one truscum who may or may not be reading this might cry, ‘It’s a scientifically proven fact that transgender people need to have dysphoria to be trans!’

To which I say fuck you, this is why that isn’t true.

Let’s go back to the definition of gender dysphoria, shall we?

“Gender dysphoria is the feeling of discomfort or distress that might accompany a difference between gender identity, sex assigned at birth or sex-related physical characteristics. This type of distress doesn't affect everyone who is transgender.”

MIGHT accompany a difference between those things, and DOESN’T affect everyone who is transgender. Interesting take coming from a scientific source, right? It’s almost like transmedicalist/truscum thinking is based off prejudice, rather than opinion; much less fact.

Especially considering dysphoria wasn’t even a word we (we meaning transgender people) chose for ourselves in the first place. It was picked by the American Psychiatric Association’s board of trustees to replace the term “Gender Identity Disorder” (GID)

Disorder. A sickness. Because Western medicine, practiced primarily by cisgender people (be they medical experts or not) has never been kind to transgender people. The word doesn’t mean what transmedicalists or truscum think it does. It doesn’t make you more valid than our fellow trans siblings just because the perceptions held by you or others of what your body and gender are worth make you miserable.