#gulag (literature subject)

Text

Oleg Orlov began his career by protesting against the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in the 1980s. At about the same time, he joined Memorial, Russia’s first and most important historical and human-rights organization—in Russia, the two subjects are organically connected—while it was still an underground, dissident operation. In the 1990s, Memorial emerged into the open and began publishing books detailing the mass arrests and murders committed by the Soviet Union. During the decade I spent researching the history of the Soviet Gulag, I ran into Memorial historians and activists all over Russia, including in their one-person “office” in Syktyvkar and in the spectacular museum, now dismantled, that they built on the site of a former concentration camp near Perm.

Memorial is dedicated to both revealing the truth about the past and preventing that past from repeating itself in the future. Its activists work in archives, but they also monitor human-rights violations in modern Russia. Orlov, who became Memorial’s co-chair, worked especially hard to expose the horrors of Russia’s wars in Chechnya, and the cultural and political destruction that followed. He did so because he wanted to live in a different kind of Russia. Now he will pay a high price for his patriotism.

On the eve of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the regime shut down Memorial, after 30 years of operation. The same regime arrested Orlov, who had criticized the invasion with the same unsparing language he had used for the previous four decades. “This brutal war,” he wrote in an article, is “not only mass murder of people and destruction of the infrastructure, economy, and cultural sites” of Ukraine but also “a severe blow to the future of Russia,” a country that “is now pushed back into totalitarianism, but this time into a fascist totalitarianism.” Like Alexei Navalny, whose funeral took place in Moscow on Friday, Orlov was extraordinarily brave—brave enough to publish his criticism of the war, of President Vladimir Putin, and of Putin’s regime.

On February 27, Orlov received a two-and-a-half-year prison sentence for “discrediting the Russian army.” Following in a long tradition of Soviet dissidents before him, Orlov made a courtroom speech, addressed to those in the room and beyond. Joseph Brodsky, who later won the Nobel Prize in Literature, sparred in 1964 with a Soviet judge who asked him by what right he dared state “poet” as his occupation: Who ranked you among poets?” Brodsky replied, “No one. Who ranked me as a member of the human race?” That exchange circulated throughout the Soviet Union in handwritten and retyped versions, teaching an earlier generation about bravery and civic courage.

Orlov’s speech will also be reprinted and reread, and someday it will have the same impact too. Here are excerpts, translated by one of his colleagues:

On the first day of my trial, terrible news shocked Russia and the entire world: Alexey Navalny was dead. I, too, was in shock. At first, I even wanted to give up on making a final statement. Who cares about words today, when we have not recovered from the shock of this news? But then I thought: These are all links in the same chain. Alexey’s death or, rather, murder; the trials of other critics of the regime including myself; the suffocation of freedom in the country; the invasion of Ukraine by the Russian army. So I have decided to speak.

I have not committed any crime. I am being tried for writing a newspaper article that described the political regime in Russia as totalitarian and fascist. I wrote this article over a year ago. Some of my acquaintances thought back then that I had exaggerated the gravity of the situation.

Now, however, it is clear that I did not exaggerate. The government in our country not only controls all public, political, and economic life, but also aspires to exert control over culture and scientific thought … There isn’t a sphere of art where free artistic expression is possible, there are no free academic humanitarian sciences, and there is no more private life either.

Orlov continued by reflecting on the absurdity of his case, of the legalistic rigamarole in Russia that conceals the regime’s lawlessness. In fact, the law is whatever Putin dictates. Everything else, the lawyers, prosecutors, and judges, are just there for show, to pretend that there is rule of law when there is not.

Let me now speak about my current trial. When it began, I refused to participate. Thanks to that, I had the opportunity to reread The Trial, a novel by Franz Kafka, during the court sessions. The current situation in our country has a lot in common with the world that Kafka’s protagonist inhabits in the book. We live with the same absurdity and arbitrariness, camouflaged by a formal adherence to some pseudo-legal procedures.

Here we are accused of “discrediting the military,” but no one explains what this means or how it differs from legitimate criticism. We are accused of “spreading deliberately false information” without anyone bothering to prove that it is indeed false. The Soviet regime used exactly the same methods when it branded any criticism as lies. Our attempts to prove the veracity of this information are punished as crimes … We are being given prison sentences for doubting that aggression against a neighboring country is being carried out for the sake of international peace and security.

This is absurd.

Kafka’s hero has no idea, until the end of the novel, of the nature of the accusation against him. He is ruled guilty and executed anyway. In Russia, the accusation is formally announced, but it is impossible to understand it within the framework of law and logic. Unlike Kafka’s hero, we do understand why we are being detained, arrested, sentenced, or killed: We are being punished for daring to criticize the authority. That is completely banned in modern Russia.

Orlov listed a few of the thousands of Russians who have been detained for criticizing the Russian government and the war, and then continued:

In recent days, they have grabbed, punished, and even imprisoned people only for coming to memorials to victims of political purges to pay tribute to the murdered Alexey Navalny, a remarkable man, brave and honest. He never lost optimism and faith in our country’s future even in the extremely hard conditions that had been set up especially for him.

The authorities are fighting against Navalny even when he is dead; they are afraid of him even after his death, and they are right to be afraid. They are destroying people’s memorials to his memory. They do this because they hope to demoralize that part of the Russian society that still takes responsibility for their country. This is a false hope.

We remember Alexey’s appeal: “Don’t give up.” I will add to this: Don’t lose your spirits, don’t lose your optimism. The truth is on our side. Those who have led our country into this hole represent the old, the frail, the outdated. They do not clearly see the future, only false images from the past, mirages of “imperial grandeur.”

Finally, Orlov addressed the court itself, the government officials and clerks, the judges, and the prosecutors. Of course, he knows, as any student of Soviet history knows, that a single dictator cannot enforce an authoritarian regime by himself. Thousands of collaborators are required. Orlov’s last words were for them.

Not all of you believed in this repressive system, of course. You sometimes regret that you are forced to participate in all of this. But you tell yourself: And what can I do? I am only following the instructions from my superiors. The law is the law.

I am speaking to you, your honor, and the others accusing me: Are you yourselves not afraid? Are you not afraid to watch what our country is becoming, our country that you, too, probably love? Are you not afraid that not only you, but also your children and, God forbid, your grandchildren, will have to live in this absurdity, this dystopia?

Do you not acknowledge the obvious truth, that the repressive machine will sooner or later also flatten those who launched it and promoted it? This has happened many times in history …

I am not completely sure that those who have created and implemented Russia’s illegal, anti-constitutional “laws” will face judicial persecution. But the punishment will definitely come. Your children or grandchildren will be ashamed to talk about the work and the deeds of their fathers, mothers, grandfathers, and grandmothers. The same will happen to those now committing crimes in the Ukraine. This, I think, is the most terrible punishment. And it is inevitable …

I regret nothing.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Black and British: A Forgotten History

Author: David Olusoga

First published: 2016

Rating: ★★★★★

Absolutely fantastic book, an important part of world history served on a silver platter of historical research goodness, human touch, and wisdom. Perfect if you are looking for a book to read during the next Black History Month. Or really any month.

The Last Bookwanderer

Author: Anna James

First published: 2023

Rating: ★★★★☆

A lovely finale to a lovely series. there was more talking and less actual exploring this time, but I enjoyed it still.

Mary

Author: Anne Eekhout

First published: 2021

Rating: ★★☆☆☆

This book felt like a fevered, confused, depressing, oppressive nightmare. Instead of feeling for Mary, which her biography and the graphic novel Mary's Monster: Love, Madness, and How Mary Shelley Created Frankenstein did, this book turned her into 1) an overtly unreliable narrator and 2) an extremely passive, weary girlfriend. Furthermore, I felt that nothing was moving, that I was stuck in the same place at the beginning as well as the end. There was no journey. Which is so very ridiculous when it comes to a book about Mary Frikkin Shelley.

Sancta Familia

Author: Martin & Tomáš Wells

First published: 2020

Rating: none

Po zralé úvaze jsem se rozhodla tuto knihu nehodnotit. Není to totiž něco, co by mělo výraznou historickou výpovědní hodnotu a ani to není dobrá literatura. Na to je zkrátka příliš navázaná na intimitu jedné rodiny. Celou dobu jsem si připadala, že mi prostě do této věci nic není a nemám na jakoukoliv kritiku ani právo.

Svátky krásné hvězdy

Author: František Kožík

First published: 1988

Rating: ★★★★☆

Milý, něžný obrázek Vánoc v dobách minulých, ač ne zcela ještě vzdálených, a tak trochu časová kapsle.

Small Acts of Kindness

Author: Jennifer Antill

First published: 2022

Rating: ★★☆☆☆

The bare bones of the story could have held the weight of a truly Tolstoyan piece of literature. Unfortunately, of the many interesting characters we are stuck with the most boring one and the main event gets an almost shameful sidenote treatment. The latter part of the book is also nothing but characters talking about things the reader already knows. Pity, especially since the historical research here was well done.

The Mayor of Casterbridge

Author: Thomas Hardy

First published: 1886

Rating: ★★★★☆

An extremely well-constructed story where the central theme is the fact of a reaction that inevitably follows any human action. I did not love this as much as I did Tess and I did not really root for any of the characters like I could in Far From the Madding Crowd, but this is definitely a solid read.

Dressed for a Dance in the Snow: Women's Voices from the Gulag

Author: Monika Zgustová

First published: 2017

Rating: ★★★☆☆

I imagine this would be a very good accompanying book to Gulag by Anne Applebaum, mostly because it has the human touch but lacks the more general and detailed realities of the Gulag system. Oral history is possibly the most fascinating way of gathering information, at the same time there will always be a level of unreliability, especially in cases when the author decides to include stories of women she did not interview herself and only learned about them second-hand.

Girl With a Pearl Earring

Author: Tracy Chevalier

First published: 1999

Rating: ★★★★☆

If you ever need a slow, quiet book about an ordinary person, about the intimacy between an artist and his muse, Tracy Chevalier has got your back with this one.

Joy to the World: How Christ's Coming Changed Everything

Author: Scott Hahn

First published: 2014

Rating: ★★★★★

As the Christmas celebrations were canceled in Bethlehem, as the baby Jesus was lying under the rubble in Palestine, there was hardly any joy to be found in our current reality. So I am thankful for this little book, for simply yet deeply touching on the subject of Christmas and its true substance.

The Biggest Prison on Earth: A History of the Occupied Territories

Author: Ilan Pappé

First published: 2016

Rating: ★★★★☆

For over 70 years Palestinians have been paying the prize for Europe failing the Jewish people. And that prize has been intolerably high. It is possibly at its highest right now. October 7th, 2023 did not happen out of nowhere. And the bloody genocide that the Israelis have unleashed after it too has its strong and old roots in previous decades. This is a very balanced account of the history of Palestine post-1948. And with all that balance, it still clearly spells out that Israel is a colonial project that needs to be dismantled.

The Winter Garden

Author: Alexandra Bell

First published: 2021

Rating: ★★★☆☆

If you like The Night Circus, there is a chance you might like The Winter Garden as well. There is a similarly flowery language and fantastical images conjured up after all. Some of the scenes are deeply touching too. But personally, I kept feeling that whilst most of the good parts were there, somehow they did not click into each other the way I would wish. Here are my greatest misgivings: a) The characters in the book are supposed to be intimate friends, but we never really get to see their friendship. We are simply told they are extremely close, but they hardly ever seek out each other and when they do, it is for only a little while and they only talk about themselves, which leads me to... b) There is really only one likable character and he is not either of the two main characters. c) I felt the obsession people had with The Winter Garden rather inexplicable, considering how much magic was obviously readily available in this world. Not a bad book, would read something from the author again, just a pity of a promise unfulfilled.

Gwen & Art Are Not in Love

Author: Lex Croucher

First published: 2023

Rating: ★★★☆☆

Cute YA romance dressed in a historical costume, but the historical aspect has next to no effect on the story (which I personally was a little sad about). There is hardly any story to talk about, but when in the right mindset, I can easily see this one being a favorite for others.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

#finishedbooks The Foundation Pit by Andrey Platonov. Ordered this after reading the previously reviewed book of essays by Joseph Brodsky. In it he was commenting on what if anything was good in Soviet literature after Solzhenitsyn and Grossman were smuggled into the west and the Bulgakov revival around the same time in the 60s. It was Platonov who he was most excited about who's work had only been rediscovered in the late 80s. He wrote the novel here in 1930 right at the time of total collectivism and off the top is the only writer other than Grossman to not only write about the reality of the situation but actually be there and see it first hand as an active participant. Platonov died in 1951 of tuberculosis which he contracted from his son whose release from the gulags he had eventually won, yet died in his arms of the disease. And for such a tragic life, this novel equals it. The story is about a worker who gets fired for thinking. He soon stumbles upon a group of workers who are digging the foundation pit for a gigantic brightly lit housing complex that is to be called socialism. Yet with each day of work, they see less and less meaning in what they do and even more so in the rhetoric they use while doing it....all the while the pit itself engulfs them. So it isn't our hero against the background but rather that background itself devouring the hero. This could be interpreted in a lot of ways. Most simply on its surface, it is another anti-Soviet satire that Brodsky contradicts by pointing out the power of devestation the book inflicts upon its subject matter that in effect exceeds any demands of social criticism. It could also be considered a precursor to dystopian novels that were to come (Brave New World/ 1984) but would prove wrong as the world he describes is actually the present. I saw surrealism as well, but the fact that what he is describing is real destroys a surrealistic interpretation. A philosophical fable would be more adapt but maybe lets draw allusions to a another writer in Dostoevsky. I would put this in a similar category of thematics as the novel could be said to represent the realization of Dostoevsky's Possessed and the absurd political reality his characters had wished for. In broader sense this could also been seen as a sequel but I would just chalk it to the tradition in Russian literature in searching for greater thought...for a more exhaustive analysis of the human condition than is at presently available.

0 notes

Note

awhile ago, you wrote a post about caliban and the witch, how it was formative for you, and a particularly scathing review of it.

would you recommend the book for reading despite its historical errors, along with reviews and commentaries like that one as supplement? and if so, are there any other corrective supplements you'd reccomend?

or do you look at it in hindsight and recommend another text in caliban's place?

xoxo ty

ahh, gosh this is kind of above my pay grade i think.

so, yeah, i read that book, and as dry as it may seem, federici's description of historical persecution of the heretics and witches is certainly very moving. and there's some interesting tidbits, like when she talks about how states suppress sex work at certain points in history. she brought my attention to some really striking images, like (iirc) a shackled woman following an army in the early modern period. back then i was full of fire and anger towards the world, and federici's book gave me that grand, powerful feeling of peeling back the curtain and seeing the horrible underlying mechanism.

nowadays, i guess i burned out of being that angry all the time. if i look at myself with a sad kind of honesty, it's not impressive by my old standards; I've kind of fallen out of the street protest scene and retracted to like, trying to take care of the few people I'm closest to. i look back on posts i made full of fire telling people to join me in the streets, reporting breathlessly on cops doing what they always do, and i kind of cringe a bit. and I tell myself i yet have potential to make some kind of impact with art and writing that i couldn't through other means, but i don't know. I hope it's growing up and getting a better understanding of the world and myself and a real reason to struggle that isn't the zeal of a convert to online cult shit; I'm afraid it's all just excuses for inner emigration.

but that's by the by. the real question is, what do you hope to gain from caliban and the witch? if you wanted to make a detailed study of the witch trials - what they involved, how they spread, how they differed between countries - federici isn't going to help much, since her book is more of a collection of anecdotes martialed to support her theory. and what is that theory? the witch trials, she argues, were crucial to the making of capitalist modernity and its reformulation of gender; they broke the power of women in feudalism and played a part in the imposition of a worldview of manageable, mechanistic order.

to make this case, she makes some historical errors; most infamously it seems she vastly inflates the number of victims of the witch trials. i haven't tried to dig into the historical literature there the way i did with the gulag stats years ago, but the consensus definitely does seem to be much lower.

still, while that may weaken her rhetorically, it doesn't overthrow her argument. my feeling there - and bearing in mind it's been some years since i read this book - is that she probably overstates her case. perhaps that's all right - if something is neglected in a field, a powerful polemical book could be argued as a necessity to open up a new course for inquiry or whatever; the initial strong conclusion will be quibbled down and the 'average consensus view' will shift, hopefully in the right direction.

but that said, do i recommend it? to be honest, i think it was a mistake to read nothing but federici's book as a sole piece of writing on early modern history. but given where i was ideologically at the time, and how hard i found (and still find) it to read longform works that aren't immediately intrinsically engaging through adhd or w/e, it's maybe better than not having read about that period at all. this is where we hit the problem that history is fractal; there is always more to read about any given subject.

the Caliban in the title refers to colonisation, and federici spends a chapter a half developing the links between witch trials in Europe and in primarily Spanish colonies which invoked the notion of witchcraft to justify genocide and enslavement. i certainly learned a bit from this, notably about the encomienda, but as a piece of writing about colonisation, it's not going to teach a lot since federici's primary lens is establishing commonalities with the European witch trials, to demonstrate their function in primitive accumulation.

my feeling today is, well, federici is sitting in between two milieus: the marxist tradition and a feminist tradition that puts a lot of emphasis on the witch trials, and she wants to reconcile them; the way she unifies them is to present primitive accumulation as ongoing and necessarily about imposing a brutal order on women in particular. there's certainly some truth here: it took capital a very very long time to dissolve the global peasantry and create a world where everyone depends on the market, and many episodes in modern history can be usefully understood as furiously violent efforts accomplish this. federici, with her taste for a grisly anecdote, creates a compelling story of the scale of violence and trauma inflicted in this process and foucauldian view of like Power getting obsessed with The Body(tm); she's also right to say that gender changed a lot with the arrival of capitalist modernity. I'm not sure the witch trials, though certainly a very illustrative symptom of how things were going, were quite the cornerstone of the whole thing though.

i think her discussion of the rise of a mechanistic scientific worldview to suppress the unproductive magical worldview is, well, very incomplete; it comes across as a sort of conspiracy to get the workers in line and nothing more, and the whole discussion sits a bit oddly when she's everywhere else a very strict materialist. i think developing the relationship between science and capitalist modernity needs a bit more care, especially if we're faced with the question of what to salvage from this mess.

one book i have never gotten round to reading but really should is Arthur Evans' Witchcraft and the Gay Counterculture. you can try in vain to find a discussion of gender variance and the categories used in federici; she talks a lot about how women were subjugated and brutalised as a class, but very little about how the categories of "men" and "women" were created and maintained/inculcated/regulated psychically, which i consider absolutely key to what gender 'is'. i also don't recall her ever really dealing with the fact that in many countries, many of the witches executed were at least considered to be 'men' by the authorities... so certainly doesn't touch the tricky subject of like, well should we take those authorities at their word or look at the long association between magic and effeminacy (c.f. ergi); with that in mind I hope Evans is some remedy even if he doesn't make her gestures towards ~materialism~ and rigour for his polemic. (it's not that surprising in retrospect that federici more recently started showing terfy leanings.)

i think my advice to you would be: if you think that sounds interesting, it's a powerful read, just don't take it to be the final word on well, anything. if you want to learn about early modern history and the witch trials, or the transition to capitalism, federici makes for an interesting framing to have in your toolbox, but her work should be understood as a theoretical polemic, and you should definitely go somewhere else if you want a more complete picture of the state of idk witch trial studies...

i can't really make recommendations there though, because I'm just a girl who has read like... four or five books on history in the last few years (apart from Federici, I can think of Graeber's Debt, Endnotes' A History of Separation, Chuang's Sorghum & Steel, Gelderloos' Worshipping Power) and generally they've been quite ideological ones that push a specific thesis. (of those, Endnotes and Chuang are definitely the most rigorous and careful). the next one I'm meaning to tackle is C Scott's Seeing Like A State or Against the Grain, but it would probably do me some good to read books that aren't by anarchists once in a while lmao

I don't think I've said anything that other Federici reviewers haven't said better, but that's basically my current stance; hope it's interesting/helpful. i definitely don't put much stock in devotion to Federici herself; i am very prone to these kinds of obsessions with seeing something as the key insight to 'how it all works', that feeling of finding the burning secret at the heart of it all is very addictive, but hopefully I've gotten a bit better at keeping critical distance and developing my own opinions by now...

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anonymous asked: Have you read Anne Applebaum’s new book The Twilight of Democracy? I’d be curious to hear your thoughts as a Brit living and working in Europe about how she writes about the schism in conservatism around democracy in the post 1989 era.

I must thank you for dropping this question because I would not have got around to finishing this book if I hadn’t been prompted by your question. I was sent The Twilight of Democracy: The Failure of Politics and the Parting of Friends some time ago by a good friend of mine who works as a newspaper foreign correspondent and knows Anne Applebaum well. I don’t know her but I have read a few of her journalistic pieces over the years when she was with the Economist and the Spectator.

I also read her harrowing book The Gulag: A history (2003). Applebaum's account of the Gulag was majestic and full of pathos. Almost 40 years after Robert Conquest's classic, The Great Terror (1968), she brought the terrible history of the Soviet camps to life again. She made brilliant use of Gulag and secret police archives to write a compelling history of how cruel and evil the Soviet system really was. Her book is one of the most vivid histories we have of a system - "the meat grinder", Russians called it - that marked or destroyed the lives of millions.

So it was with trepidation I approached this latest book because it’s dealing with weighty stuff. It’s partly a brilliant political reportage, partly a Central European-style psychodrama, partly a political analysis, and partly a personal diary. It is also a postscript to a distinct epoch when the Berlin Wall comes down and we enter the post-Cold War. The story Applebaum tells is that of the death of anti-communism as the public philosophy of the West. During the Cold War, the Soviet Union wasn’t only America’s principal military adversary but also its ideological and moral “other.” Both left and right in America and Western Europe defended their competing visions of a liberal society in reaction to the Stalinist nightmare. But in the absence of the Red Menace both the left and the right turned on liberalism and that continues today with Trump in America, Brexit and the EU, and Victor Orban in Hungary.

I cowardly put it near the back of my reading queue because I already reading more than a few weighty tomes (mostly history and literature books) and I didn’t want my senses to be overloaded. I typically have fifteen books on the go and I travel with four whenever I’m stuck in a business class lounge or in a hotel room and so I can switch according to my mood. With Applebaum’s book I also wanted to take notes and so I took my time with it. I’ve finished it but I’m still processing my thoughts on it. I hope to write up a book review as part of my on going Treat Your S(h)elf post in my blog. So don’t hold your breath.

I’m glad that I’ve read it, but it’s a haunting book, that’s for sure. It’s a potent, and somewhat apocalyptic, reminder that democracies are only as strong as the people who live in them, that there is nothing about them that is ontologically strong and secure. In order to continue to function as they should, they require buy-in and maintenance and support and, above all, faith. Without those things they are subject to corrosion and destruction from within.

I love how she mixes the personal with the political because Applebaum as a Yale and Oxford educated historian and journalist, and as someone who is married to then Polish deputy foreign minister, Radek Sikorski, was as connected as anyone in the 1990s and 2000s to both liberal and conservative wings in Western democracies.

It’s a great opening to start at a soirée of the great and the good to see the dramatic scene.

On New Year’s Eve in 1999, Applebaum and her husband Radek Sikorski, who was then Poland’s deputy foreign minister, hosted what sounded like a really great party. Their home was filled with American and British journalists, Polish dignitaries, and some of their neighbours. Applebaum characterises them as representatives of “the right,” which at the time meant something vastly different from what it means today. They were staunch anti-communists in the Thatcherite tradition, who were optimistic about Poland’s embrace of democracy and free markets. The gathering was held at an old manor house that had been abandoned in 1945 by its previous owners, who had fled from the advancing Red Army. It turns out Sikorski’s family had purchased and renovated the dilapidated house, making it the perfect metaphor for a nation rising from decades of oppression at the hands of the Soviet Union.

Unfortunately, the friendships and the optimism that animated that celebration have largely evaporated in the past 20 years or so. According to Applebaum, “Nearly two decades later, I would now cross the street to avoid some of the people who were at my New Year’s Eve party. They, in turn, would not only refuse to enter my house, they would be embarrassed to admit they had ever been there.”

Many of her Polish friends, colleagues, and acquaintances have abandoned their belief in classical liberalism and embraced an illiberal right-wing authoritarianism that sees democracy as flawed and free markets as rigged by elites. She maintains that the bitter political divisions that developed among those who attended this party in Poland are similar to those now found in many countries today, including Hungary, Spain, Italy, Great Britain and the United States.

“Were some of our friends always closet authoritarians?” Applebaum wonders. “Or have the people with whom we clinked glasses in the first minutes of the new millennium somehow changed over the subsequent two decades?” The book is an admirable quest for answers and goes a long way toward providing them.

Applebaum identifies several factors that have contributed to the rise of twenty-first-century illiberal movements, often using personal anecdotes to illustrate her points. She is not then particularly concerned with theories, nor is she attempting to offer a grand thesis about the phenomenon. She makes a few passing references to the ideas of Hannah Arendt and Theodor Adorno among others, and relies on the work of a behavioural economist, Karen Stenner, to point out that about a third of the world’s population simply has an authoritarian disposition that makes them deeply suspicious of views different from their own.

Indeed throughout the book, Applebaum is as concerned with people as she is with processes, in that she often focuses on the individuals whose choices and political actions have led to the current state of affairs. There’s a potent truth here, for it’s a fact that no authoritarian is able to rise to power without having the support of at least some of those in positions of cultural authority to buy in, what Applebaum, following in the footsteps of Julien Benda’s classic 1927 book, The Treason of the Intellectuals, refers to these sycophants as clercs. These are the people who make authoritarianism palatable to the masses, whether through their positions in powerful media or by distorting museum exhibits to support a dominant agenda (which has happened in Hungary).

Applebaum helps us better understand the disturbing increase in division, the roiling anger, the willingness to discard democracy by not just the elites but also the masses and especially the populists. It used to be we understood revolution by charting the inequality and desperate poverty that led to them, but in Hungary, Poland, Spain, the UK, and in the United States, while many may be hungry few are starving. And those in the streets of London and Washington are hardly destitute.

Applebaum writes, “They have food and shelter. They are literate. If we describe them as ‘poor’ or ‘deprived,’ it is sometimes because they lack things that human beings couldn’t dream of a century ago, like air-conditioning or Wi-Fi. In this new world, it may be that big, ideological changes are not caused by bread shortages but by new kinds of disruptions. These new revolutions may not even look like the old revolutions at all. In a world where most political debate takes place online or on television, you don’t need to go out on the street and wave a banner to assert your allegiance. In order to manifest a sharp change in political affiliation, all you have to do is switch channels, turn to a different website every morning, or start following a different group of people on social media.”

Applebaum is a very good writer; her style is lucid, and her arguments are bracing. This has made her one of the most powerful voices of the anti-populist resistance. But the strength of her new book is not so much in exposing the authoritarian nature of populists in power but in revealing the intellectual hollowness of the anti-communist consensus. I didn’t find myself agreeing to everything in the book because it’s not always easy to compare apples to oranges when one looks at the USA, Britain, Europe, and Eastern Europe. Culture and history gets in the way of easy generalisations.

Overall, this book is, at least my first impressions, something of an intellectual call to arms. It reaches out to each of us, asking us to do our part to ensure that democracy doesn’t go the way of so many other failed political systems. As she reminds us near the end of the book: “no political victory is ever permanent, no definition of ‘the nation’ is guaranteed to last, and no elite of any kind […] rules forever.” There’s something more than a little terrifying about the idea that history is one long cycle, that every political victory must be re-fought again and again and again. But such, alas, is the nature of modernity.

Thanks for your question.

#question#ask#anne applebaum#books#tys#reading#history#politics#society#culture#twilight of democracy#eastern europe#usa#britain#elites#populism#rightwing#leftwing#ideology

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

R.I.P. (Rest in PDFs), Part II

in progress ...

Part I (A-M) is here.

Note: If you see your work on here and prefer that it not be made freely accessible, please email me at: [email protected], and I will remove it. Thank you!

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Naomi Murakawa, The origins of the carceral crisis: Racial order as "law and order" in postwar American politics

Natasha Ginwala, Maps That Don’t Belong

Nathaniel Mackey, Other: From Noun to Verb

Nawal El Saadawi, Woman at Point Zero. Translated by Sherif Hatata.

Nick Estes, Liberation, from Our History Is the Future: Standing Rock versus the Dakota Access Pipeline, and the Long Tradition of Indigenous Resistance

Occupy Poetics. Curated by Thom Donovan

Patricia Hill Collins, Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment

Patrick Chamoiseau, School Days. Translated from the French by Linda Coverdale

Patrick Wolfe, Settler colonialism and the elimination of the native

Pëtr Kropotkin, Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution

Phil Cordelli, New Wave

Phil Cordelli, Tidal State

Poetry of Resistance in Occupied Palestine, translated by Sulafa Hijjawi

Reece Jones, Violent Borders: Refugees and the Right To Move

Rinaldo Walcott, Moving Toward Black Freedom, the first chapter of The Long Emancipation

Rinaldo Walcott, The Problem of the Human: Black Ontologies and “the Coloniality of Our Being”

Rinaldo Walcott, Queer Returns: Human Rights, the AngloCaribbean and Diaspora Politics

Rizvana Bradley, Aesthetic Inhumanisms: Toward an Erotics of Otherworlding

Robert Yerachmiel Sniderman, from CEDE; [Truesse, Unknown Worker, Charles]; Chaos and Rectification

Roberto Tejada, In Relation: The Poetics and Politics of Cuba’s Generation-80

Robin D.G. Kelley, Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination

Robin D.G. Kelley, Hammer and Hoe: Alabama Communists During the Great Depression

Roland Barthes, A Lover’s Discourse. Translated by Richard Howard.

Roland Barthes, Mythologies. Translated by Annette Lavers.

Roland Barthes, The Pleasure of the Text. Translated by Richard Miller.

Roland Barthes, Roland Barthes. Translated by Richard Howard.

Rosemary Sayigh, Palestinians: From Peasants to Revolutionaries

Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States

Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Fatal Couplings of Power and Difference: Notes on Racism and Geography

Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Forgotten Places and the Seeds of Grassroots Planning

Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Globalisation and US prison growth: from military Keynesianism to post-Keynesian militarism

Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis, and Opposition in Globalizing California

Saidiya Hartman, The Plot of Her Undoing (Notes on Feminisms)

Saidiya Hartman, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America

Samuel Delaney, Times Square Red, Times Square Blue

Saniya Saleh, Seven Poems. Translated from the Arabic by Robin Moger.

Saniya Saleh, Seven Poems. Various translators

S*an D. Henry-Smith, Flotsam Suite

Shosana Felman & Dori Laub, Testimony: Crises of Witnessing in Literature, Psychoanalysis, and History

Simone Browne, Introduction, and Other Dark Matters; Notes on Surveillance Studies; Branding Blackness (from Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness)

Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace. Translated by Emma Crawford and Mario von der Ruhr

Simone Weil, The Iliad, or the Poem of Force. Translated by Mary McCarthy

Simone Weil, The Need for Roots: Prelude to a Declaration of Duties towards Mankind. Translated by Arthur Wills

Simone Weil, Oppression and Liberty. Translated by Arthur Wills and John Petrie

Simon Leung and Marita Sturken, Displaced Bodies in Residual Spaces

Solidarity Texts: Radiant Re-Sisters

Sophia Terazawa, I Am Not A War

Sora Han, Letters of the Law: Race and the Fantasy of Colorblindness in American Law

#StandingRockSyllabus, compiled by NYC Stands with Standing Rock Collective

Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study

Steve Biko, Black Consciousness and the Quest for True Humanity

Stokely Carmichael and Charles V. Hamilton, the Black Power chapter of Black Power: The Politics of Liberation in America

Sukoon Magazine, Volume 4, Issue 2, Winter 2017

Suzanne Césaire, 1943: Surrealism and Us; The Great Camouflage (from The Great Camouflage: Writings of Dissent (1941-1945)

Sylvia Wynter, Black Metamorphosis: New Natives in a New World

Sylvia Wynter, “No Humans Involved:” An Open Letter to My Colleagues

Sylvia Wynter, Novel and History, Plot and Plantation

Tamara K. Nopper, The Wages of Non-Blackness: Contemporary Immigrant Rights and Discourses of Character, Productivity, and Value

Tavia Nyong’o, Racial Kitsch and Black Performance

Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, Dictee

Thom Donovan, “In The Dirt of the Line”: On Bhanu Kapil’s Intense Autobiography

Tina Campt, Listening to Images

Tina Campt, The Lyric of the Archive

Toni Cade Bambara, The Lesson

Toni Morrison, The Future of Time: Literature and Diminished Expectations

Toni Morrison, Memory, Creation, and Writing

Trinh T. Minh-ha, Documentary Is/Not a Name

Trinh T. Minh-ha, The Walk of Multiplicity

Trinh T. Minh-ha, Woman, Native, Other: Writing Postcoloniality and Feminism

Veena Das, Life and Words: Violence and the Descent into the Ordinary

Võ Nguyên Giáp, People’s War, People’s Army

Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project. Translated from the German by Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin

Walter Rodney, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa

W.E.B. Du Bois, Black Reconstruction

W.E.B. Du Bois, The World and Africa: Color and Democracy

Wendy Brown, States of Injury: Power and Freedom in Late Modernity

Wendy Trevino, Brazilian Is Not A Race

Wendy Trevino, narrative

Winona LaDuke, Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Environmental Futures

Worker-Student Action Committees, France May ‘68, by R. Gregoire and F. Perlman

Yanara Friedland, Abraq ad Habra: I will create as I speak

Ye Mimi, eleven poems

Yerbamala Collective, Our Vendetta: Witches vs Fascists

Yi Sang, The Wings. Translated from the Korean by Ahn Jung-hyo and James B. Lee

You Can’t Shoot Us All: On the Oscar Grant Rebellions

Youna Kwak, Home

Yūgen, edited by LeRoi Jones & Hettie Cohen (1958-1962), #1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8.

Yuri Kochiyama, The Impact of Malcolm X on Asian-American Politics and Activism

Yuri Kochiyama, Then Came the War

Zora Neale Hurston, Mules and Men

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

BNHA 314, Lady Nagant and war crimes, the take of history nerd.

This text will contain a discussion of war crimes, human experimentation, and genocide. Please, if you find such topics uncomfortable and upsetting, don't read.

When I was twelve years old, I visited what remains of the Auschwitz-Birkenau death camp complexes in Oświecim, Poland. I heard about the utter torture people of various nations had to go through. I walked through the cells in which people were starved. I saw names long gone written upon the thousand of thousands of luggage left behind. I saw shoes, belonging to men, women, and children alike. I saw where those alive slept, the pits in which you wouldn't hold a dog, much less a human. I saw the walls against which people were slaughtered.

I looked at what remains of the endless list of names of people who died to the Third Reich's death machine.

Arbeit macht frei, says the slogan atop of the gates, Work sets you free.

Our guide told us the nazis used to smile and add, Durch Krematorium Nummer drei. Through the Crematorium Number three.

The Auschwitz Museum is not all of the testimony of the pain the people suffered under Nazi Germany, but it's the symbol. I can talk much more about it, about the horror of living in Nazi-occupied Poland, about the terror the Jews come through, about the evil residing in the hearts of men but I can never describe it all. You can't really describe the horror of those times.

During the Nuremberg Trial, the war criminals responsible for it all, one after another, claimed they did it all because they were told to.

This argument didn't hold.

In 1942 Erwin Rommel, the Desert Fox, was ordered to execute the war prisoners in Africa. Supposedly, he burned Hitler's orders. Nothing happened to him. He was never punished by the nazi regime for disobeying their leader.

Most of the war criminals on the Nuremberg Trial were sentenced to death. Society decided that the excuse of being ordered to do something meant nothing.

The year is 2021. The leaks of the BNHA 314 chapter are out. I feel... complicated.

I did it because I was ordered to.

It could mean nothing. Just coincidence, right?

But.

The name of the character who said it is mocking me. Lady Nagant is badass; she is the female villain character I was waiting for. She is powerful, she is interesting, she has such potential.

But.

Her name.

People pointed it up already. Rifle Mosin-Nagant, one most famously used by both Simo Häyhä, the White Death, and Lyudmila Pavlichenko, the Lady Death. It seems so badass and cool at the first glance but I always felt somewhat iffy about it. She is named after a weapon, and yes, a weapon is not responsible for committing the crimes, it's always the people.

But for me, this weapon screams the Soviet Union and they didn't use it only in wars. Soviets committed unspeakable crimes, the ones for which they were never punished. They slaughtered people, they starved people, they committed genocide. Soviet Regime was not better than the nazis.

Deportations. Massacres. Gulags. All of it is not as widely discussed but I always felt there was a good, macabre example of how cruel they could be.

There is a book in Polish I read for my literature classes, The Another World by Gustaw Herling-Grudzieński. It talks about the author's memories of living in a Soviet gulag, in starvation and cold, working in inhuman conditions. What heinous crime did he commit to ending up on the end of the world?

You see, Mr. Herling-Grudzieński was wearing the army's boots. And yeah, his name sounded somewhat German. That's all. Only those boots and last name for years of painful labor, starvation, and death.

Am reaching with all of it? Probably. But emotions are not logical. It feels wrong for me to call a character after a weapon that committed genocide but maybe it's just me. After all, I know I'm biased, I was listening to all those things since I was a little girl.

I just don't like the connotation of Lady Nagant's name and those words. Even more, because we see people threatening her while something like that never happened in reality. Are we supposed to feel sorry for her? Are we supposed to forgive her and Hawks?

And that, for me goes further: Are we supposed to forgive war criminals now because of orders? Is that what he is trying to say? What is your manga about now, Mr. Horikoshi?

Because I can't. I will not. Too many people suffered because of them. Too many people died.

My thinking does sound like reaching and overinterpretation, but then, I remember the last straw of it all, something I really can't forgive because of how malicious it felt.

When Ujiko's real name was revealed as Maruta Shiga in reference to the human experimentation on the Chinese civilian population by Imperial Division 731, I didn't understand what exactly it means. I don't speak Japanese. But then, oh, god, I learned.

Japanese war crimes, compared to those committed by nazis, are controversial topics. Most of them were swept under the rug by the politics of that time. I wish I could not judge those people for the choices they made. I wish I could say I'm not utterly disgusted by how the perpetrators of those crimes were never truly punished. I can't. Like said, I'm very biased about the subject, I feel strongly about all of it.

I'm not Chinese, though, I can't even imagine how they feel about all of it.

I never learned about what the Japanese did in school, I had to uncover the depravity of Imperial Japan myself. Is it wrong? Absolutely yes. Does the educational system suck? Yes. The thing is, people just try and try to keep those heinous crimes under this stupid rug and I'm ashamed of that, I'm ashamed of myself, and most of all, I'm ashamed of what Horikoshi did as a human being.

I learned that the only country in which nazi is treated as a hero in China. Why? Because even he was so disgusted by what the Japanese did. Because he actually tried to protect the Chinese people.

A nazi.

What does it say?

What did the Imperial Division 731 did, though? Human experimentation, as I mentioned earlier. They infected people with viruses, they tested flamethrowers and weapons on them, they poisoned people, they vivisected humans. They were not better than their western allies, nazis which people are so afraid to speak of.

What happened to them? They exchanged their freedom and lives for the results of their experiments. They were never punished.

I'm going to be cruel: Horikoshi and all of the Jump deserved the backlash they got, their apologies mean nothing. How the hell they let it through in the first place? How the fuck all those editors, all of the staff, saw it and nobody cared? Nobody thought oh, that's a bad idea, let's change it? If they didn't know, it doesn't help either! It only confirms the stereotype of Japanese people not knowing and not caring about the crimes they committed.

Hot take: In some way, calling him that is just as bad as if he was named after Mengele.

All of the people who suffered under the Japanese regime deserved better than being a footnote, a simple reference in Japanese manga of all things. Those were the people we are talking about, for fuck's sake, people who went through hell and never saw justice.

That's... my take on all of it.

All of my words are pretty emotional but the subject is very emotional; it's hard not to feel in such a way when you know what happened. The sheer lack of respect BNHA holds toward the people who suffered through those awful things is astounding.

I always had problems with BNHA, okay? I disagreed about a lot of things Horikoshi did, but I always kept quiet, not wanting to speak up because there were some things I loved.

But it makes me so angry, how the author does things like that. If they did it one time, it could be an accident. Two times would be dangerous. But three? Three creates a habit.

Please, stop that, Mr. Horikoshi.

Your manga is about heroes and their corrupted society. It's action shounen, not a dark story about the war which still haunts people. It's not about our rotten world and making all of those references is disrespectful toward the victims. Stop playing with history like that.

TLDR; Soviets bad. Nazis bad. Imperial Japan bad. Hori, stop this pls, and let me see Dabi already.

31 notes

·

View notes

Note

Have any advice for incoming 9th graders?

here’s a list

- if you don’t trust counselors and or don’t feel like trekking from your location to the counselor’s office just to talk to a wall about how you feel, keep a notebook that’s specifically used as a diary. jotting my feelings down instead of keeping them pent up really helped me stay sane throughout high school

- going to tutorials if you’re not understanding a subject will show your teacher that you want to learn and actually pass their class

- hollywood/pop culture’s portrayal of high school is completely false for a majority of the time. when i trudged through gulag/high school, everyone suffered and the true villain is the administration. cliques did exist but it wasn’t a large scale case of conflict theory (us v. them mentality in sociology)

- spark notes are online and free, i heavily advise using them in literature classes (especially if you’re forced to read jane eyre)

- if you don’t have any friends in your lunch hour, ask a teacher you’re comfortable with if you could have lunch with them if their lunch break is at the same time as yours (got that idea from my brother)

- thriftbooks.com is a great website to get used books from for english

- desmos.com is a life saver for math that requires a graphing calculator, it’s also free and online

- if you experience menstruation once a month and or suffer from chronic pain and don’t feel like waiting for someone to bring you ibuprofen or whatever pain reliever you take, keep your own pills in an altoids container. nobody will suspect a thing

- if you feel like on-level classes are too slow and not detailed enough for you, i recommend looking into ap (advanced placement) classes

- if you’re taking an ap class and unsure if you want to take the ap test, talk to your teacher about it since they know more about that than a counselor

- not taking an ap test for whatever reason is hella okay! some folks are there for the credit, some folks are there to get away from essentially being babysat in on-level classes, some folks are there for more content, and some are there for a combination of those reasons

- watch crash course on youtube if you just need a refresher on a topic, especially good for history

- if you know you’re not going to be in class, email your teacher ahead of time

- if a teacher is restricting you from taking a restroom break despite the fact you’re about to have an accident, break their rules and go to the restroom. if they give you trouble about it, ask them if they want to deal with the stench of human excrement in their precious classroom for the rest of the day

- don’t be one of those folks who go out of their way to break rules, it just makes the administration create tougher and more absurd rules to make everyone suffer

i can’t think of anything else. i hope my tips come in handy, live long and prosper 🖖

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

School of Horror

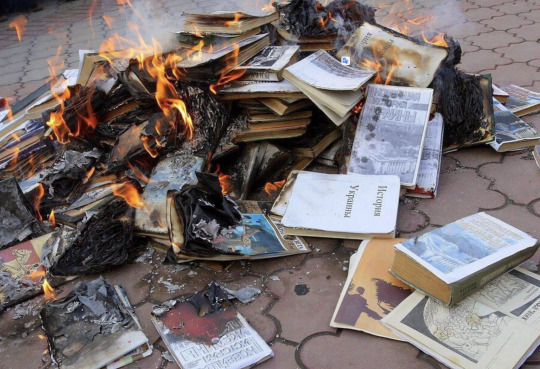

In Mariupol, the occupiers canceled the summer holidays to teach Ukrainian children the history of Russia and the Russian language until September 1. Ukrainian books are burned.

The occupying so-called "government organizations" decided to remove the summer holidays and until September 1 to arrange an accelerated course for Ukrainian children in the Russian school curriculum. The lessons will be taught in Russian, and the subjects will also be Russian: the Russian language, the history of Russia, etc.

"The main goal is de-Ukrainization and preparation for the school year according to the Russian program. Children will be taught Russian language and literature, Russian history, and mathematics in Russian all summer long. The occupiers plan to open 9 schools. However, so far, only 53 teachers have been persuaded. 6 teachers per school — a vivid illustration of Russian education in Mariupol during the occupation" Petro Andryushchenko, advisor to the mayor of the city.

All Ukrainian textbooks have been burned: literature written in the state language has been destroyed by the Russians as "nazi". Russians pay special attention to textbooks on the history of Ukraine. Following the logic of the Russians, the language of the Ukrainians and the Ukrainians themselves are nazis, and everything nazi must be destroyed. Is this not proof that the Russians staged a genocide of the Ukrainian people?

"All textbooks of the History of Ukraine are extremist. Because of the liberation movement and Muscovy. I generally keep quiet about the URA (Ukrainian rebel army — ed.) and Stepan Andreyevich (Bandera — ed.). The same textbooks in literature. And Vasyl Stus (Ukrainian poet, killed by the Russians in the Gulag for his patriotic position) is again an extremist," Petro Andryushchenko.

Remarkably, many books are written in Russian. But the fact that they contain information about Ukraine makes the books nazi in Russian eyes. The British Ambassador to Ukraine posted a photo of the occupier fire from Ukrainian books and signed: "Burning Ukrainian history books is not denazification. It is the opposite. #RussianAggression"

An essential fact about Vasyl Stus: before killing the poet, the Soviet authorities provided him with their lawyer at the trial. This lawyer, who did not defend Stus, but deliberately sent him into exile, is Viktor Medvedchuk.

0 notes

Photo

“And how we burned in the camps later, thinking: What would things have been like if every Security operative, when he went out at night to make an arrest, had been uncertain whether he would return alive and had to say good-bye to his family? Or if, during periods of mass arrests, as for example in Leningrad, when they arrested a quarter of the entire city, people had not simply sat there in their lairs, paling with terror at every bang of the downstairs door and at every step on the staircase, but had understood they had nothing left to lose and had boldly set up in the downstairs hall an ambush of half a dozen people with axes, hammers, pokers, or whatever else was at hand?… The Organs would very quickly have suffered a shortage of officers and transport and, notwithstanding all of Stalin’s thirst, the cursed machine would have ground to a halt! If…if…We didn’t love freedom enough. And even more – we had no awareness of the real situation….”

~ Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago

[What a Freedom, 1903 - Ilya Repin]

• “I was born at Kislovodsk on 11th December, 1918. My father had studied philological subjects at Moscow University, but did not complete his studies, as he enlisted as a volunteer when war broke out in 1914. He became an artillery officer on the German front, fought throughout the war and died in the summer of 1918, six months before I was born. I was brought up by my mother, who worked as a shorthand-typist, in the town of Rostov on the Don, where I spent the whole of my childhood and youth, leaving the grammar school there in 1936. Even as a child, without any prompting from others, I wanted to be a writer...” More: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/1970/solzhenitsyn/biographical/

• Ilya Efimovich Repin was born in the town of Chuguev near Kharkov in the heart of the historical region called Sloboda Ukraine. His parents were Russian military settlers. In 1866, after apprenticeship with a local icon painter named Bunakov and preliminary study of portrait painting, he went to Saint Petersburg and was shortly admitted to the Imperial Academy of Arts as a student. More: https://www.ilyarepin.org/biography.html

#aleksandr solzhenitsyn#solzhenitsyn#freedom#shame#the gulag archipelago#ilya repin#ukrainian art#painting#russian art

1 note

·

View note

Text

Nothing to Envy: Ordinary Lives in North Korea

Nothing to Envy: Ordinary Lives in North Korea by Barbara Demick

Nothing to Envy follows the lives of six North Koreans over fifteen years—a chaotic period that saw the death of Kim Il-sung, the unchallenged rise to power of his son Kim Jong-il, and the devastation of a far-ranging famine that killed one-fifth of the population.

Taking us into a landscape most of us have never before seen, award-winning journalist Barbara Demick brings to life what it means to be living under the most repressive totalitarian regime today—an Orwellian world that is by choice not connected to the Internet, in which radio and television dials are welded to the one government station, and where displays of affection are punished; a police state where informants are rewarded and where an offhand remark can send a person to the gulag for life.

Demick takes us deep inside the country, beyond the reach of government censors. Through meticulous and sensitive reporting, we see her six subjects—average North Korean citizens—fall in love, raise families, nurture ambitions, and struggle for survival. One by one, we experience the moments when they realize that their government has betrayed them.

Nothing to Envy is a groundbreaking addition to the literature of totalitarianism and an eye-opening look at a closed world that is of increasing global importance.

Download :

Nothing to Envy: Ordinary Lives in North Korea

More Book at:

Zaqist Book

0 notes

Note

I can totally relate, getting a smartphone and joining tumblr drastically decreased my reading time. And I'm a slow reader in general! I'm getting back into reading now though :) I read a lot of different genres but I really like mysteries, thrillers, true crime stuff and historical fiction and I also love contemporary. Right now I'm really into survival/adventure books or whatever that's called, Ive read like books about '96 Everest disaster and I'm about to move on to K2. (1/2)

(2/2)Idk why, I don’t even like mountaineering. What Russian authors have you read? I tried a few when I was a teen but I never enjoyed them and I don’t know if it’s because I’m from a former USSR country and we have this irrational aversion to all things Russian or if I was just too young/not picking up the right books. I couldn’t really pick my faves but right now I love Ali Smith,Jeanette Winterson,John Irving. Could you recommend something from Kazuo Ishiguro, Ian McEwan, Margaret Atwood? x

I think we share a lot of the same reading tastes, Anon. I really like ‘survival’ stuff too - I’m a sucker for frontier history - and went through a stage of reading lots about Everest expeditions too. I’m sure that if you’ve been reading about the ‘96 Everest expeditions you’ve read ‘Into Thin Air’by Jon Krakauer - but if not, I thoroughly recommend it!! And the feature documentary Touching The Void about the 1985 expedition directed by Kevin MacDonald is AMAZING!

Yeah, I can imagine if you’re from the former USSR you might not be inclined to pick up Russian authors. I read a lot but the two that I loved most were Dostoevsky (maybe try ‘Notes From Underground’) and Solzhenitsyn (not sure what to recommend of his. Everything? ‘The Gulag Archipelago’. The horror of it all is almost unbearable, but as you’re from a former USSR country you’ll know far more about that than me of course)

I love Ali Smith, Jeanette Winterson and John Irving too!

Kazuo Ishiguro’s work varies massively in subject and tone. But based on the books you’ve said you’d like I would recommend ‘Never Let Me Go’. It’s very different to his other books but it’s a real page-turner. It was made into a film a few years ago. Ishiguro just won the Nobel Prize for Literature this week!!

For Ian McEwan, that’s a tough one. I just looked at the novels he’s written and I’ve read all of them over the years (I hadn’t even realised!). So try his very first novel ‘The Cement Garden’ (it’s kinda creepy and weird, and was made into a film). Then his big famous books like ‘Atonement’ and ‘Enduring Love’ (actually also films) and more recently try ‘The Children Act’ which has just been filmed with Fionn Whitehead and will be out next year.

And Margaret Atwood…the master! You’ve got to read ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’ and then try ‘Alias Grace’ which is very different but a great old yarn.

And then just another random recommendation that you might like is ‘The Tenderness of Wolves’ by Stef Penney. A big page-turning yarn, frontier history, survival, murder…I think you’ll like it!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nothing to Envy - Barbara Demick

Nothing to Envy

Ordinary Lives in North Korea

Barbara Demick

Genre: Social Science

Price: $9.99

Publish Date: December 29, 2009

Publisher: Random House Publishing Group

Seller: Penguin Random House LLC

An eye-opening account of life inside North Korea—a closed world of increasing global importance—hailed as a “tour de force of meticulous reporting” ( The New York Review of Books ) NATIONAL BOOK AWARD FINALIST • NATIONAL BOOK CRITICS CIRCLE AWARD FINALIST In this landmark addition to the literature of totalitarianism, award-winning journalist Barbara Demick follows the lives of six North Korean citizens over fifteen years—a chaotic period that saw the death of Kim Il-sung, the rise to power of his son Kim Jong-il (the father of Kim Jong-un), and a devastating famine that killed one-fifth of the population. Demick brings to life what it means to be living under the most repressive regime today—an Orwellian world that is by choice not connected to the Internet, where displays of affection are punished, informants are rewarded, and an offhand remark can send a person to the gulag for life. She takes us deep inside the country, beyond the reach of government censors, and through meticulous and sensitive reporting we see her subjects fall in love, raise families, nurture ambitions, and struggle for survival. One by one, we witness their profound, life-altering disillusionment with the government and their realization that, rather than providing them with lives of abundance, their country has betrayed them. Praise for Nothing to Envy “Provocative . . . offers extensive evidence of the author’s deep knowledge of this country while keeping its sights firmly on individual stories and human details.” — The New York Times “Deeply moving . . . The personal stories are related with novelistic detail.” — The Wall Street Journal “A tour de force of meticulous reporting.” — The New York Review of Books “Excellent . . . humanizes a downtrodden, long-suffering people whose individual lives, hopes and dreams are so little known abroad.” — San Francisco Chronicle “The narrow boundaries of our knowledge have expanded radically with the publication of Nothing to Envy. . . . Elegantly structured and written, [it] is a groundbreaking work of literary nonfiction.” —John Delury, Slate “At times a page-turner, at others an intimate study in totalitarian psychology.” — The Philadelphia Inquirer http://dlvr.it/R6HtQ6

0 notes

Text

11 Questions

I was tagged by @a-study-in-shakespeare. Thank you!!

1. What subject would you like to write a thesis on? How WW1 and its aftermath shaped our modern era.

2. Favourite guilty musical pleasure? Do you mean favorite musical that is a guilty pleasure, or favorite music that is a guilty pleasure? Either way, I’ll answer both. My favorite musicals are Wicked, Jesus Christ Superstar (I love singing along to Judas’ parts), Hairspray, and 1776. Music that is my guilty pleasure: “Crazy in Love” era Beyonce, “Firework” by Katy Perry, “Alejandro” and “Bad Romance” by Lady Gaga, Latin pop (courtesy of my Zumba class), industrial metal (Otep, Kidneythieves, Rammstein, Heimataerde), pop and soul from the 1950s/1960s

3. Oldest movie you’ve seen? Definitely a Charlie Chaplin film. I don’t remember which one, but it was from 1919 I think. I had his whole collection on VHS waaaaay back in the day when I went through my silent movie phase in high school.

4. Favourite song in your native language? Ahahaha! You know I can’t pick just one ;).

5. You get to spend one day in a place of your choice. Where do you go and why? I recently discovered this café downtown and fell in love with it! Too bad it’s only open until 5:30pm Monday-Friday, never on the weekends. I would love to spend a day there tucked in a corner reading a book and catching up on writing.

6. Which book would you recommend to anyone and why? Ooof…again, I cannot pick just one, so I’ll do three!. All the Light We Cannot See, by Anthony Doerr – I can’t recommend this book enough, especially if you’re like me and love historical fiction. Good Omens, by Terry Pratchett and Neil Gaiman – leave it to an angel and a demon who have grown accustomed to their comfy life on earth to sabotage the prophesied End of Times. Hilarity ensues. In the First Circle, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn – semi-autobiographical account of life in a Soviet sharashka (research and development lab in Soviet gulag labor system, typically composed of imprisoned scientists and engineers). Don’t let the length scare you, it is totally worth the read! The events take place just over three days, but like all Russian literature, there is so much going on! The cast of characters and how they interweave would put George R.R. Martin to shame.

7. How do you motivate yourself to get stuff done? I…don’t really? I usually go through a mental list of what needs to be done and order it by importance, then assess how I’m feeling that day. If I’m feeling kind of down, I pick easier things to accomplish and save the other stuff for days when I have more energy. I’ve found as long as I do something, no matter how small, I stay motivated to complete bigger tasks when the time comes instead of letting it all pile up.

8. Top thing on your bucket list? Eurotrip! Preferably with my two best friends.

9. What is the quality you look for in new people you meet? It may sound weird, but I always look for a twin. I like seeing where people’s similarities to me start and how far or close they get to being another me.

10. Best advice you ever received? I don’t think I’ve ever gotten “good” advice. Sure, people have given me advice, but upon closer analysis, I’ve always found their advice to be strictly from their perspective. They don’t try to see things from my perspective, if that makes any sense? And of course, I’m always putting myself in other people’s shoes and analyzing things from their perspective, so I always assume other people do the same for me, but they really don’t.

11. TV show you watch when you’re feeling down? I’m a sucker for HGTV and the Travel Channel ;).

And now for my questions:

1.) When you eat brownies, do you prefer edge, corner, or middle?

2.) What’s your lucky number?

3.) What are your quirks?

4.) Favorite word or words in a foreign language?

5.) Worst book ever read and why?

6.) Worst movie/TV show ever seen and why?

7.) Do you have a favorite trope?

8.) Do you have a daily “ritual” – like having tea every afternoon?

9.) Favorite villain?

10.) What’s your theme song?

11.) You’re the captain of a spaceship, which fictional characters would you pick to be on your crew?

I tag @nyhne and @gummyboots. No pressure, totally optional as always :)

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

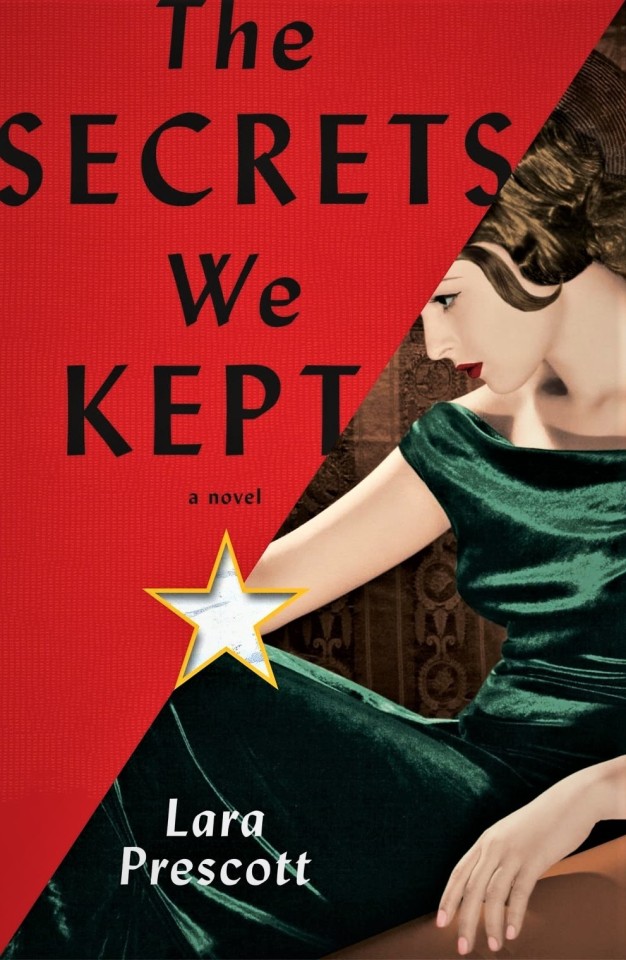

The Secrets We Kept by Lara Prescott review – an impressive debut

The fascinating tale of how the CIA plotted to smuggle Doctor Zhivago back into Russia drives an enjoyable debut

At the height of the cold war, the CIA ran an initiative known as “cultural diplomacy”. Following the premise that “great art comes from true freedom”, the agency seized on painting, music and literature as effective tools for promoting the western world’s values, and funded abstract expressionism exhibitions and jazz tours. But when it came to the country that produced Tolstoy, Pushkin and Gogol – a nation that, according to a character in Lara Prescott’s impressive debut novel, “values literature like the Americans value freedom” – the focus was always going to be on the written word. And her subject, the part the CIA played in bringing Boris Pasternak’s masterpiece Doctor Zhivago to worldwide recognition, was the jewel in cultural diplomacy’s crown.

In 1955 rumours began to circulate that Pasternak, hitherto known largely as a poet, having survived a heart attack and Stalin’s purges, was ailing and politically compromised but had nonetheless managed to finish his magnum opus. The sweeping, complex historical epic – and simple love story – that is Doctor Zhivago had been a decade in the writing under the most adverse circumstances imaginable: the imprisonment of Pasternak’s lover, Olga Vsevolodovna Ivinskaya; the death in the gulag of his friend and fellow writer Osip Mandelstam and the suicides of two others in his circle, Paolo Iashvili and Marina Tsvetaeva; constant surveillance and his own ill health. Because of its subversive emphasis on the individual and its critical stance on the October Revolution, no publishing house in the Eastern bloc would touch it. When an enterprising Italian publisher sent a secret emissary to Pasternak’s dacha, in miserable desperation the writer handed it over, with the inscription “This is Doctor Zhivago. May it make its way around the world.” The manuscript was smuggled out to West Berlin – and the CIA made their move. Their aim was clandestinely to publish a Russian edition and return it to its homeland.

This is remarkable raw material for a novel. Prescott’s book, the subject of a legal row after Pasternak’s great-niece Anna Pasternak accused her of plagiarising her own biography of Olga, has all the ingredients for a spy thriller. It has a great cast of characters and a wealth of historical detail to be mined, plus the potential for insight into a bizarre and compelling point in our history and, of course, a love story. Prescott’s first achievement is her identification of these qualities: weaving them into a complex and involving narrative is altogether more of a challenge, but she works hard and with considerable ambition to meet it, and entwines a surprising love story of her own invention.

Like Doctor Zhivago, her novel follows a number of characters’ viewpoints. There is Pasternak himself and Olga, whom we first encounter as she is arrested, pregnant with his child, and imprisoned for refusing to divulge what she knows of the book. Irina Prozdhova, the Washington-based émigré daughter of a man murdered by the Russian regime, has been newly recruited by the agency; Sally Forrester is an experienced spy and honeytrap or “swallow”. Both these women have secrets of their own. And, most engagingly, we hear from the communal voice of the typing pool of the CIA’s Soviet Russia division.

There are a couple of male walk-on parts, including, in the novel’s only properly bum note, CIA agent Teddy Helms, who courts Irina and whose brief section on a mission to Britain is so full of missteps (his MI6 contact referring to “the little Mrs”, English fish and chips being breaded rather than battered) that one begins to wonder if the author intends it as a riff on his obtuseness. And indeed there is a sly joke against the patriarchy woven into the plot: at a time when women were at their most invisible, expected to confine themselves to traditional roles, they made the best spies. It is the female characters who carry this adventure, from the pragmatic, loyal, indestructible Olga to the marvellous typists. With their Virginia Slims and Thermoses of turkey noodle soup, they make up a kind of smart, gossipy Greek chorus whose commentary begins and ends the novel.

Prescott may not be an accomplished prose stylist, but her characterisation is often deft. Her Pasternak is vividly flawed: histrionic, lachrymose but stubbornly lovable. Her research is thorough if occasionally a little too visible, and the portrayal of the love between Olga and Pasternak is poignant and convincing. Sold in 25 countries, with film rights optioned, The Secrets We Kept is set to be a publishing phenomenon; but more importantly, it is a thoroughly enjoyable read.

• Christobel Kent’s A Secret Life is published by Sphere. The Secrets We Kept is published by Hutchinson (£12.99).

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at http://justforbooks.tumblr.com

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

ТУР ПО «МЕСТАМ НЕ СТОЛЬ ОТДАЛЁННЫМ». ЧАСТЬ III. «СТАРЫЙ КАНЬОН», ЯГОДНОЕ, ЭЛЬГЕН И «СВЕТЛЫЙ»

Третий отрезок пути стал самым экстремальным. Пробираясь к лагерю «Старый каньон», наши «туристы» увязли в болоте. Всей машиной. Выбирались сутки. И это еще не все – после были музей Варлама Шаламова, озеро Джека Лондона, женский лагерь близ поселка Эльген и тряская дорога верхом на УАЗике к лагерю «Светлый».

#гулаг#Колыма#магадан#сталин#Россия#история ссср#репрессии#нквд#лагеря#kolyma#discoveryrussia#russia#gulag (literature subject)#mygulag#gulag museum#soviet-story#political's repressions#gulag

0 notes