#graduate school jeremiad

Text

Once I come up with a killer band name all I'll need to do is actually learn how to sing or play an instrument!

(Honestly this thought exercise is actually a really fun coping mechanism for rejection of any sort I highly recommend it)

#credit to my friends for some of these suggestions#also earnestly if I do end up needing to take a gap year after this year I do want to learn bass guitar#I've wanted to since high school#also Kaeyleighh graph is probably my favorite since my undergrad thesis is on Caley graphs so#the idea of using a Mormon-esque style spelling of Caley is inordinately funny to me for some reason#Two Directions Going the Same Way is what my brother and his best friend wanted to call the band they dreamed of starting in middle school#I've always earnestly found that one really funny#polls#graduate school Jeremiad

99 notes

·

View notes

Note

Did you name your novels or were they just ShoH 1, ShoH 2, ShoH 3, etc.? (If yes, can you also tell their names please?)

Hi there, thanks for the question! In my head they were Volumes 1-20-something--actually, if you’ll believe it, in my head for a long time I named the books after colors, and somehow kept track... but at some point I did put a formal list of potential titles together. I never used the “real” titles mentally, except for The Bridge of Bones, Fortress of the Dead, and the books in Series II and III: I still remember thinking of the first book in Series I as “red” and the second book as “orange”... 😬 And the files/scenes in each book were labelled “aaa”, “bb”, “++”. The more letters there were, the number of times the scene had been rewritten (so “a” was a first draft of the first scene in the book, and “aaa” was the same scene, but more polished... what was I thinking?)

Anyway, I had to go digging to remember my ideas for the titles of some of the earlier books, so please forgive any cringyness lol, I was pretty young when I wrote Series I! I also don’t know if these are all of the ShoH novels--these are just the main chronological ones, but there were some spin-offs and AUs that I don’t name here!

Series I: World Without End

The Witching Wheel

Blood and Fire

Gunpowder Magic

Battle Mage

The Knife That Spoke

Oathbreaker

Shadowsight

The Code of War

The City of Midnight

The Foundling’s Soul

The Silver Covenant

The Gates of the Earth

Child of the Stars

Series II: The Storm of the Worlds

The Thunder March

The Lightning War

The Conquered Sky

Series III: The Land of the Gods

The Eternal Sea

The Country Cloaked in Moon

Bridge Series:

Fortress of the Dead

The Bridge of Bones

The Razor Crown

The God-King’s Sun

Series IV: The Naming of All Things

Harlequin

Valkyrie

Jeremiad

The Council of Kingmakers

Canticle of the Namer

The Blessed Isles

Read below if you want as concise of an explanation for these titles as I can provide!

In case you’re curious, Series I up until Battle Mage follows the protagonist, Arainia, as a young girl (I think 11 or 13) after the death of her mother, being sent to Solhadur amidst family conflict with her father and older sister, her various adventures there at school (meeting Red, Pan, Neon, etc.), graduating, attempting to join the Ket army (it’s complicated), and then deciding to join the Shepherds at around 18 or 19. She undergoes training in the academy, joins her squad (this is where Trouble, Riel, Chase, Halek, and the rest come in), and becomes a Shepherd officer alongside her childhood best friend Blade in Battle Mage. The Knife that Spoke and onward details various missions, investigations, battles, recruitments, and adventures that they all embark on as young adults into their twenties, with some books following different perspectives in the squad (Blade, Riel, Trouble, Chase, Halek, Red, Wintry, and Junoth [the last two not in the game] all get their turn narrating a book or at least a large part of one), with Shery, Ayla, Mimir, Lavinet, Tallys, Neon, Croelle, and many other characters featuring heavily. Around this time, civil war is brewing between the Elves, Ket, and certain factions of Mages, and Endarkened attacks soon begin to rise as the Order struggles to keep the peace.

Series II details the outbreak of total world war that is essentially the Castigation in the game, with Western Norm kingdoms and territories suddenly and unexpectedly marching on the East--except in the novels, demons and demon armies are also involved, and the war is ultimately averted/ended in a truce as both sides finally unite to confront the Endarkened. It’s during this time period that Riel defects and seemingly betrays the group in favor of “the other side.” Blade is also seemingly killed at the end of the first book of this series and doesn’t reappear again until the third book, Arainia is captured and held as a prisoner of war all while thinking her best friend is dead, and it’s an upsetting time for everybody. Junoth also actually dies. RIP. Croelle pops in to save the day!

Series III details the aftermath of the war and a mission to find unoccupied land for displaced factions of soldiers, diplomats, traders, and civilians from the Norm territories (led by Riel), leading to a voyage across the Mirror Sea to explore the vast continent to the south of Blest, called colloquially “the Land of the Gods.” The second book in this series is also when Blade and Arainia FINALLY confess their feelings for each other and get together, and the big love triangle in the series is finally mostly settled. Oh, but things also aren’t perfect because the Order forbids relationships between officers (like they’ll actually be fired, not Blade’s lame rule in the game lmao), so they live in fear of being discovered because neither wants to quit being a Shepherd! Their hope is that Blade will be named Commander when the current one resigns, and then he can just... change the rule LOL.

The Bridge Series has some companion novels that take place in between Series III and IV; Fortress of the Dead is Croelle-centric (this is when he informally joins the Order in the books) and The Bridge of Bones details some political bullshit and coups and conspiracies within the Order when its Commander dies unexpectedly and seemingly names a shady outsider (Edric) as the new Commander instead of Blade. The group is placed on different squads to split them up and prevent rebellion from brewing (it happens anyway), and it’s all very crazy. This is also when Lavinet sort of becomes a good guy, Shery becomes a badass, Shyf Cian first appears as the HR rep everyone hates, and this book is also pretty Chase-centric (he pretty much saves the day) and features a Mage serial killer, a psychopathic criminal syndicate leader, and an evil Changeling! I think it’s my favorite novel of the series. From what I remember, The Razor Crown and The God-King’s Sun are just super angsty for no good reason other than I guess I felt like writing a lot of angst--though the God-King’s Sun is also the first appearance of a true Autarch in the series.

By the time we get to Series IV, the characters are in their thirties, settling into adulthood and their respective roles in life. Blade finally assumes command of the Order, Blade and Arainia get married, Halek and Wintry have a baby (Kana!), Halek turns 33 and has a life crisis, Arainia gets pregnant (and then kidnapped for a large part of her pregnancy lolll), Riel and Chase finally make reluctant peace, some other stuff happens, uh there’s some Mimir stuff in there, Red successfully makes a trip to another world, and Arainia gives birth to a Ket-Mage son in... I think it was either The Canticle of the Namer or The Blessed Isles.

So... yeah! 28+ main novels, and I’m still going, just for me! 😂 I tend to write a lot of AUs of the series in my off-time, though sometimes the AUs are just “what if this took place in the same world but things are totally different--like what if they were politicians instead of Shepherds, what if the Shepherds functioned differently due to a different historical event occurring, what if the Castigation happened but it was Mages who instigated it, what if they were soldiers in a war 5000 years before the main series takes place, etc.”; or they take place in totally different worlds, like the characters as cops in a modern world that has cell phones and cars but also still has the Diminished races and magic somehow!

Thanks for your question, and for reading this long talk! 😅

#...#damn#that's a lot when you list it out lol i just usually hazily think of it as a handful of books but it's like 30 D:#some of these are novellas though!#most of the bridge series except for the bridge of bones are#Shepherds of Haven#ironically 'shepherds of haven' was never used as a title#novel#novels#original novel#original novels#titles#long#long post#anon

87 notes

·

View notes

Photo

So fascist. I’m joking, sort of. When I was trying to make the ‘gram work, I hashtagged a picture of a bookcase I’d fished out of the trash with #cottagecore—and then actual #cottagecore people liked the post. This proves that a hashtag cannot be used ironically. As for #darkacademia, I gave my thoughts a few months ago in my essay on Donna Tartt’s The Secret History:

I am too old, and I have seen too much, to fall in love with the novel that helped to inspire the #darkacademia trend. Granted, as a student who spent four years reading Shakespeare, Dickens, and Joyce under the high, dim vault of the Cathedral of Learning’s commons room, I had the most #darkacademic experience possible at an urban public research university. But then I spent seven years in graduate school, and seven years after that as an adjunct professor; I have seen the true darkness of academia, and it has very little to do with the Gothic trappings of Donna Tartt’s classic 1992 thriller.

What is #darkacademia, really, but a response to this genuine darkness? Such Poe-like airs as Tartt and her contemporary devotees put on are an attempt to reenchant the life of the mind after its exsanguination and despiritualization by the increasingly rationalized bureaucracies of the contemporary university. Despite attempts to bring the trend in line with social justice, #darkacademia represents a conservative backlash against both academic leftism and corporatist neoliberalism in our time, with these two tendencies’ routinized subversions and mandatory inculcations and profit-seeking administrations. In reaching back a generation to canonize The Secret History as the inspiration of their aesthetic, today’s gloomy ephebes chose wisely, since Tartt’s novel belongs to the last backlash, coming as it did between The Closing of the American Mind (1987) and The Western Canon (1994)—a black blossom between the Blooms—and deriving some of its emotional impetus, however disavowed, from the same sources as those jeremiads against the leveling of humanities education.

I enjoy issuing such vast historico-aesthetic declarations—it comes from the Marxist side of my education, and anyway, what else can you do with popular fiction?—but I take them very lightly.

What is the Cathedral of Learning? It would be a place of pilgrimage for the darkly academic, the academic darklings, if only they knew about it. You could always look up pictures online, but I’ve always thought “a picture is worth a thousand words” counted as dispraise of images: pictures don’t tell you anything at all—you literally need one thousand words to understand even one! So I give you a couple hundred words from my unpublished manuscript The Class of 2000, both the great Pittsburgh novel and the great turn-of-the-millennium novel, as the world will someday learn. I include, for the #darkacademic fans, the description of the Cathedral of Learning (sorry for the repetition between the Tartt review and the novel of “high, dim vault”—in my defense, it’s a high, dim vault) and a subsequent short dialogue on architecture that reflects a trending controversy of today. All you need to know is that this section is about my narrator and his religious friend, both high-school students, on a field trip. Please enjoy!

from The Class of 2000

Lauren and I were on a lunch break from an art-class field trip to the Carnegie Museum of Art. In a rain-presaging fall wind, we wandered around Oakland.

She had brought a pack of strawberry-flavored clove cigarettes—I don’t know where she got them—and we smoked to try to blend in with the students from Pitt and Carnegie Mellon. Despite the massing clouds, some of them still lounged on the lawn of the Cathedral of Learning, asleep with Plato or Marx propped open on their faces. We circled the Cathedral and stared up at its sooty limestone mass rearing into the clouds—the tallest building for miles.

We put out our cigarettes and walked through the high, dim vault of its first floor. Students at weighty wooden study tables, strangely unaffected by the anachronistic grandeur that rose around them, sighed in frustration over chemistry or French textbooks; their sweatshirts and jeans affronted the solemn Gothic atmosphere.

Between classes, we ducked in and out of the nationality rooms. To promote cultural understanding and civic investment in the university while this vast structure was under construction in the 1920s—I quote from memory the brochure we read that day—the Chancellor had invited the participation of the many immigrant communities who’d raised this city, and the University continued its outreach since then, from the 18th-century English who’d fought off their brethren at Fort Pitt to those who came from Eastern and Southern Europe at the turn of the century seeking work in the factories that made the world’s steel to the recent arrivals from Africa and Asia who wished to compete in the global economy. Representatives of said communities were tasked with proposing, planning, and funding the construction of classrooms to commemorate the nations they’d left and the cultures they carried. We saw samovars, stained glass, calligraphic screens, menorahs, nationalist liberators, bodhisattvas, and Yoruba gods. We discussed the glory of studying human achievement in vast tower consecrated to the genius of all the world’s cultures.

We left the Cathedral and its grounds, lit two more cloves, and walked deeper into the neighborhood, where campus buildings mingled with banks and bookstores and restaurants.

On Fifth Avenue, we found ourselves in front of an odd sight: the bell tower of an old church, a sepia stone spire, stood alone, though the rest of the church had long been demolished. In its place gloated a modern university building, all glass and steel, curved at the edge where it would have abutted the bell tower, as if to avoid a contaminating touch.

“I like the church tower better,” Lauren mused.

We regarded our reflections in the glass of the new building.

“So do I.”

“You know, since you don’t believe in God, you really aren’t entitled to like the tower better. Its purpose is to lift your vision, to point the way to heaven. The modern, godless building just shows you”—she pointed forward, in the flesh and in the glass—“your own small self.”

I pointed to the space over my shoulder in the glass where the Cathedral of Learning hovered behind us in the distance.

“That’s a secular structure,” I said.

“Please,” she said as she turned away in dismissal. “If what I said wasn’t true, would they have to call it a cathedral?”

#darkacademia#donna tartt#literature#cathedral of learning#fiction#creative writing#literary criticism#original writing#architecture

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

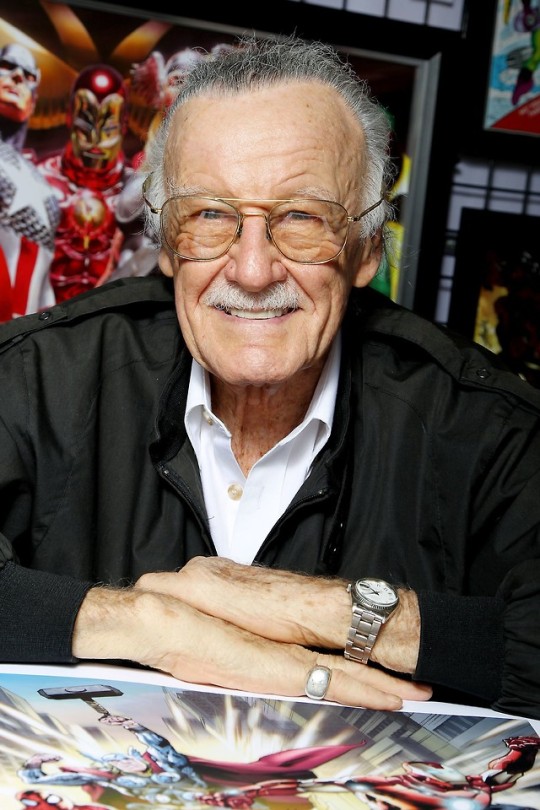

If Stan Lee revolutionized the comic book world in the 1960s, which he did, he left as big a stamp — maybe bigger — on the even wider pop culture landscape of today.

Think of “Spider-Man,” the blockbuster movie franchise and Broadway spectacle. Think of “Iron Man,” another Hollywood gold-mine series personified by its star, Robert Downey Jr. Think of “Black Panther,” the box-office superhero smash that shattered big screen racial barriers in the process.

And that is to say nothing of the Hulk, the X-Men, Thor and other film and television juggernauts that have stirred the popular imagination and made many people very rich.

If all that entertainment product can be traced to one person, it would be Stan Lee, who died in Los Angeles on Monday at 95. From a cluttered office on Madison Avenue in Manhattan in the 1960s, he helped conjure a lineup of pulp-fiction heroes that has come to define much of popular culture in the early 21st century.

Mr. Lee was a central player in the creation of those characters and more, all properties of Marvel Comics. Indeed, he was for many the embodiment of Marvel, if not comic books in general, overseeing the company’s emergence as an international media behemoth. A writer, editor, publisher, Hollywood executive and tireless promoter (of Marvel and of himself), he played a critical role in what comics fans call the medium’s silver age.

Many believe that Marvel, under his leadership and infused with his colorful voice, crystallized that era, one of exploding sales, increasingly complex characters and stories, and growing cultural legitimacy for the medium. (Marvel’s chief competitor at the time, National Periodical Publications, now known as DC — the home of Superman and Batman, among other characters — augured this period, with its 1956 update of its superhero the Flash, but did not define it.)

Under Mr. Lee, Marvel transformed the comic book world by imbuing its characters with the self-doubts and neuroses of average people, as well an awareness of trends and social causes and, often, a sense of humor.

In humanizing his heroes, giving them character flaws and insecurities that belied their supernatural strengths, Mr. Lee tried “to make them real flesh-and-blood characters with personality,” he told The Washington Post in 1992.

Energetic, gregarious, optimistic and alternately grandiose and self-effacing, Mr. Lee was an effective salesman, employing a Barnumesque syntax in print (“Face front, true believer!” “Make mine Marvel!”) to market Marvel’s products to a rabid following.

He charmed readers with jokey, conspiratorial comments and asterisked asides in narrative panels, often referring them to previous issues. In 2003 he told The Los Angeles Times, “I wanted the reader to feel we were all friends, that we were sharing some private fun that the outside world wasn’t aware of.”

Though Mr. Lee was often criticized for his role in denying rights and royalties to his artistic collaborators , his involvement in the conception of many of Marvel’s best-known characters is indisputable.

He was born Stanley Martin Lieber on Dec. 28, 1922, in Manhattan, the older of two sons born to Jack Lieber, an occasionally employed dress cutter, and Celia (Solomon) Lieber, both immigrants from Romania. The family moved to the Bronx.

Stanley began reading Shakespeare at 10 while also devouring pulp magazines, the novels of Arthur Conan Doyle, Edgar Rice Burroughs and Mark Twain, and the swashbuckler movies of Errol Flynn.

He graduated at 17 from DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx and aspired to be a writer of serious literature. He was set on the path to becoming a different kind of writer when, after a few false starts at other jobs, he was hired at Timely Publications, a company owned by Martin Goodman, a relative who had made his name in pulp magazines and was entering the comics field.

Mr. Lee was initially paid $8 a week as an office gofer. Eventually he was writing and editing stories, many in the superhero genre.

At Timely he worked with the artist Jack Kirby (1917-94), who, with a writing partner, Joe Simon, had created the hit character Captain America, and who would eventually play a vital role in Mr. Lee’s career. When Mr. Simon and Mr. Kirby, Timely’s hottest stars, were lured away by a rival company, Mr. Lee was appointed chief editor.

As a writer, Mr. Lee could be startlingly prolific. “Almost everything I’ve ever written I could finish at one sitting,” he once said. “I’m a fast writer. Maybe not the best, but the fastest.”

Mr. Lee used several pseudonyms to give the impression that Marvel had a large stable of writers; the name that stuck was simply his first name split in two. (In the 1970s, he legally changed Lieber to Lee.)

During World War II, Mr. Lee wrote training manuals stateside in the Army Signal Corps while moonlighting as a comics writer. In 1947, he married Joan Boocock, a former model who had moved to New York from her native England.

His daughter Joan Celia Lee, who is known as J. C., was born in 1950; another daughter, Jan, died three days after birth in 1953. Mr. Lee’s wife died in 2017.

A lawyer for Ms. Lee, Kirk Schenck, confirmed Mr. Lee’s death, at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles.

In addition to his daughter, he is survived by Ms. Lee and his younger brother, Larry Lieber, who drew the “Amazing Spider-Man” syndicated newspaper strip for years.

In the mid-1940s, the peak of the golden age of comic books, sales boomed. But later, as plots and characters turned increasingly lurid (especially at EC, a Marvel competitor that published titles like Tales From the Crypt and The Vault of Horror), many adults clamored for censorship. In 1954, a Senate subcommittee led by the Tennessee Democrat Estes Kefauver held hearings investigating allegations that comics promoted immorality and juvenile delinquency.

Feeding the senator’s crusade was the psychiatrist Fredric Wertham’s 1954 anti-comics jeremiad, “Seduction of the Innocent.” Among other claims, the book contended that DC’s “Batman stories” — featuring the team of Batman and Robin — were “psychologically homosexual.”

Choosing to police itself rather than accept legislation, the comics industry established the Comics Code Authority to ensure wholesome content. Gore and moral ambiguity were out, but so largely were wit, literary influences and attention to social issues. Innocuous cookie-cutter exercises in genre were in.

Many found the sanitized comics boring, and — with the new medium of television providing competition — readership, which at one point had reached 600 million sales annually, declined by almost three-quarters within a few years.

With the dimming of superhero comics’ golden age, Mr. Lee tired of grinding out generic humor, romance, western and monster stories for what had by then become Atlas Comics. Reaching a career impasse in his 30s, he was encouraged by his wife to write the comics he wanted to, not merely what was considered marketable. And Mr. Goodman, his boss, spurred by the popularity of a rebooted Flash (and later Green Lantern) at DC, wanted him to revisit superheroes.

Mr. Lee took Mr. Goodman up on his suggestion, but he carried its implications much further.

In 1961, Mr. Lee and Mr. Kirby — whom he had brought back years before to the company, now known as Marvel — produced the first issue of The Fantastic Four, about a superpowered team with humanizing dimensions: nonsecret identities, internal squabbles and, in the orange-rock-skinned Thing, self-torment. It was a hit.

Other Marvel titles — like the Lee-Kirby creation The Incredible Hulk, a modern Jekyll-and-Hyde story about a decent man transformed by radiation into a monster — offered a similar template. The quintessential Lee hero, introduced in 1962 and created with the artist Steve Ditko (1927-2018), was Spider-Man.

A timid high school intellectual who gained his powers when bitten by a radioactive spider, Spider-Man was prone to soul-searching, leavened with wisecracks — a key to the character’s lasting popularity across multiple entertainment platforms, including movies and a Broadway musical.

Mr. Lee’s dialogue encompassed Catskills shtick, like Spider-Man’s patter in battle; Elizabethan idioms, like Thor’s; and working-class Lower East Side swagger, like the Thing’s. It could also include dime-store poetry, as in this eco-oratory about humans, uttered by the Silver Surfer, a space alien:

“And yet — in their uncontrollable insanity — in their unforgivable blindness — they seek to destroy this shining jewel — this softly spinning gem — this tiny blessed sphere — which men call Earth!”

Mr. Lee practiced what he called the Marvel method: Instead of handing artists scripts to illustrate, he summarized stories and let the artists draw them and fill in plot details as they chose. He then added sound effects and dialogue. Sometimes he would discover on penciled pages that new characters had been added to the narrative. Such surprises (like the Silver Surfer, a Kirby creation and a Lee favorite) would lead to questions of character ownership.

Mr. Lee was often faulted for not adequately acknowledging the contributions of his illustrators, especially Mr. Kirby. Spider-Man became Marvel’s best-known property, but Mr. Ditko, its co-creator, quit Marvel in bitterness in 1966. Mr. Kirby, who visually designed countless characters, left in 1969. Though he reunited with Mr. Lee for a Silver Surfer graphic novel in 1978, their heyday had ended.

Many comic fans believe that Mr. Kirby was wrongly deprived of royalties and original artwork in his lifetime, and for years the Kirby estate sought to acquire rights to characters that Mr. Kirby and Mr. Lee had created together. Mr. Kirby’s heirs were long rebuffed in court on the grounds that he had done “work for hire” — in other words, that he had essentially sold his art without expecting royalties.

In September 2014, Marvel and the Kirby estate reached a settlement. Mr. Lee and Mr. Kirby now both receive credit on numerous screen productions based on their work.

Mr. Lee moved to Los Angeles in 1980 to develop Marvel properties, but most of his attempts at live-action television and movies were disappointing. (The series “The Incredible Hulk,” seen on CBS from 1978 to 1982, was an exception.)

Avi Arad, an executive at Toy Biz, a company in which Marvel had bought a controlling interest, began to revive the company’s Hollywood fortunes, particularly with an animated “X-Men” series on Fox, which ran from 1992 to 1997. (Its success helped pave the way for the live-action big-screen “X-Men” franchise, which has flourished since its first installment, in 2000.)

In the late 1990s, Mr. Lee was named chairman emeritus at Marvel and began to explore outside projects. While his personal appearances (including charging fans $120 for an autograph) were one source of income, later attempts to create wholly owned superhero properties foundered. Stan Lee Media, a digital content start-up, crashed in 2000 and landed his business partner, Peter F. Paul, in prison for securities fraud. (Mr. Lee was never charged.)

In 2001, Mr. Lee started POW! Entertainment (the initials stand for “purveyors of wonder”), but he received almost no income from Marvel movies and TV series until he won a court fight with Marvel Enterprises in 2005, leading to an undisclosed settlement costing Marvel $10 million. In 2009, the Walt Disney Company, which had agreed to pay $4 billion to acquire Marvel, announced that it had paid $2.5 million to increase its stake in POW!

In Mr. Lee’s final years, after the death of his wife, the circumstances of his business affairs and contentious financial relationship with his surviving daughter attracted attention in the news media. In 2018, Mr. Lee was embroiled in disputes with POW!, and The Daily Beast and The Hollywood Reporter ran accounts of fierce infighting among Mr. Lee’s daughter, household staff and business advisers. The Hollywood Reporter claimed “elder abuse.”

In February 2018, Mr. Lee signed a notarized document declaring that three men — a lawyer, a caretaker of Mr. Lee’s and a dealer in memorabilia — had “insinuated themselves into relationships with J. C. for an ulterior motive and purpose,” to “gain control over my assets, property and money.” He later withdrew his claim, but longtime aides of his — an assistant, an accountant and a housekeeper — were either dismissed or greatly limited in their contact with him.

In a profile in The New York Times in April, a cheerful Mr. Lee said, “I’m the luckiest guy in the world,” adding that “my daughter has been a great help to me” and that “life is pretty good” — although he admitted in that same interview, “I’ve been very careless with money.”

Marvel movies, however, have proved a cash cow for major studios, if not so much for Mr. Lee. With the blockbuster “Spider-Man” in 2002, Marvel superhero films hit their stride. Such movies (including franchises starring Iron Man, Thor and the superhero team the Avengers, to name but three) together had grossed more than $24 billion worldwide as of April.

“Black Panther,” the first Marvel movie directed by an African-American (Ryan Coogler) and starring an almost all-black cast, took in about $201.8 million domestically when it opened over the four-day Presidents’ Day weekend this year, the fifth-biggest opening of all time.

Many other film properties are in development, in addition to sequels in established franchises. Characters Mr. Lee had a hand in creating now enjoy a degree of cultural penetration they have never had before.

Mr. Lee wrote a slim memoir, “Excelsior! The Amazing Life of Stan Lee,” with George Mair, published in 2002. His 2015 book, “Amazing Fantastic Incredible: A Marvelous Memoir” (written with Peter David and illustrated in comic-book form by Colleen Doran), pays abundant credit to the artists many fans believed he had shortchanged years before.

Recent Marvel films and TV shows have also often credited Mr. Lee’s former collaborators; Mr. Lee himself has almost always received an executive producer credit. His cameo appearances in them became something of a tradition. (Even “Teen Titans Go! to the Movies,” an animated feature in 2018 about a DC superteam, had more than one Lee cameo.) TV shows bearing his name or presence have included the reality series “Stan Lee’s Superhumans” and the competition show “Who Wants to Be a Superhero?”

Mr. Lee’s unwavering energy suggested that he possessed superpowers himself. (In his 90s he had a Twitter account, @TheRealStanlee.) And the National Endowment for the Arts acknowledged as much when it awarded him a National Medal of Arts in 2008. But he was frustrated, like all humans, by mortality.

“I want to do more movies, I want to do more television, more DVDs, more multi-sodes, I want to do more lecturing, I want to do more of everything I’m doing,” he said in “With Great Power …: The Stan Lee Story,” a 2010 television documentary. “The only problem is time. I just wish there were more time.”

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at http://justforbooks.tumblr.com

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

By Jonathan Kandell and Andy Webster

Nov. 12, 2018

Leer en español

Stan Lee, who as chief writer and editor of Marvel Comics helped create some of the most enduring superheroes of the 20th century and was a major force behind the breakout successes of the comic-book industry in the 1960s and early ’70s, died on Monday in Los Angeles. He was 95.

His death, at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, was confirmed by Kirk Schenck, a lawyer for Mr. Lee’s daughter, J. C. Lee.

Mr. Lee was for many the embodiment of Marvel, if not comic books in general, and oversaw his company’s emergence as an international media behemoth. A writer, editor, publisher, Hollywood executive and tireless promoter (of Marvel and of himself), he played a critical role in what comics fans call the medium’s silver age.

Many believe that Marvel, under his leadership and infused with his colorful voice, crystallized that era, one of exploding sales, increasingly complex characters and stories, and growing cultural legitimacy for the medium. (Marvel’s chief competitor at the time, National Periodical Publications, now known as DC — the home of Superman and Batman, among countless other characters — augured this period but did not define it, with its 1956 update of its superhero the Flash.)

Mr. Lee was a central player in the creation of Spider-Man, the X-Men, the Fantastic Four, Iron Man, the Hulk, Thor and the many other superheroes who, as properties of Marvel Comics, now occupy vast swaths of the pop culture landscape in movies and on television.

Under Mr. Lee, Marvel revolutionized the comic book world by imbuing its characters with the self-doubts and neuroses of average people, as well an awareness of trends and social causes and, often, a sense of humor.

In humanizing his heroes, giving them character flaws and insecurities that belied their supernatural strengths, Mr. Lee tried “to make them real flesh-and-blood characters with personality,” he told The Washington Post in 1992.

“That’s what any story should have, but comics didn’t have until that point,” he said. “They were all cardboard figures.”

Energetic, gregarious, optimistic and alternately grandiose and self-effacing, Mr. Lee was an effective salesman, employing a Barnumesque syntax in print (“Face front, true believer!” “Make mine Marvel!”) to market Marvel’s products to a rabid following.

He charmed readers with jokey, conspiratorial comments and asterisked asides in narrative panels, often referring them to previous issues. In 2003 he told The Los Angeles Times, “I wanted the reader to feel we were all friends, that we were sharing some private fun that the outside world wasn’t aware of.”

Though Mr. Lee was often criticized for his role in denying rights and royalties to his artistic collaborators , his involvement in the conception of many of Marvel’s best-known characters is indisputable.

Reading Shakespeare at 10

He was born Stanley Martin Lieber on Dec. 28, 1922, in Manhattan, the older of two sons born to Jack Lieber, an occasionally employed dress cutter, and Celia (Solomon) Lieber, both immigrants from Romania. The family moved to the Bronx.

Stanley began reading Shakespeare at 10 while also devouring pulp magazines, the novels of Arthur Conan Doyle, Edgar Rice Burroughs and Mark Twain, and the swashbuckler movies of Errol Flynn.

He graduated at 17 from DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx and aspired to be a writer of serious literature. He was set on the path to becoming a different kind of writer when, after a few false starts at other jobs, he was hired at Timely Publications, a company owned by Martin Goodman, a relative who had made his name in pulp magazines and was entering the comics field.

Mr. Lee was initially paid $8 a week as an office gofer. Eventually he was writing and editing stories, many in the superhero genre.

Stan Lee

At Timely he worked with the artist Jack Kirby (1917-94), who, with a writing partner, Joe Simon, had created the hit character Captain America, and who would eventually play a vital role in Mr. Lee’s career. When Mr. Simon and Mr. Kirby, Timely’s hottest stars, were lured away by a rival company, Mr. Lee was appointed chief editor.

As a writer, Mr. Lee could be startlingly prolific. “Almost everything I’ve ever written I could finish at one sitting,” he once said. “I’m a fast writer. Maybe not the best, but the fastest.”

Mr. Lee used several pseudonyms to give the impression that Marvel had a large stable of writers; the name that stuck was simply his first name split in two. (In the 1970s, he legally changed Lieber to Lee.)

During World War II, Mr. Lee wrote training manuals stateside in the Army Signal Corps while moonlighting as a comics writer. In 1947, he married Joan Boocock, a former model who had moved to New York from her native England.

His daughter Joan Celia Lee was born in 1950; another daughter, Jan, died three days after birth in 1953. Mr. Lee’s wife died in 2017. He ism, survived by Ms. Lee and his younger brother, Larry Lieber, who drew the “Amazing Spider-Man” syndicated newspaper strip for years.

In the mid-1940s, the peak of the golden age of comic books, sales boomed. But later, as plots and characters turned increasingly lurid (especially at EC, a Marvel competitor that published titles like Tales From the Crypt and The Vault of Horror), many adults clamored for censorship. In 1954, a Senate subcommittee led by the Tennessee Democrat Estes Kefauver held hearings investigating allegations that comics promoted immorality and juvenile delinquency.

Feeding the senator’s crusade was the psychiatrist Fredric Wertham’s 1954 anti-comics jeremiad, “Seduction of the Innocent.” Among other claims, the book contended that DC’s “Batman stories” — featuring the team of Batman and Robin — were “psychologically homosexual.”

Opting to police itself rather than accept legislation, the comics industry established the Comics Code Authority to ensure wholesome content. Graphic gore and moral ambiguity were out, but so largely were wit, literary influences and attention to social issues. Innocuous cookie-cutter exercises in genre were in.

Many found the sanitized comics boring, and — with the new medium of television providing competition — readership, which at one point had reached 600 million sales annually, declined by almost three-quarters within a few years.

With the dimming of superhero comics’ golden age, Mr. Lee grew tired of grinding out generic humor, romance, western and monster stories for what had by then become Atlas Comics. Reaching a career impasse in his 30s, he was encouraged by his wife to write the comics he wanted to, not merely what was considered marketable. And Mr. Goodman, his boss, spurred by the popularity of a rebooted Flash (and later Green Lantern) at DC, wanted him to revisit superheroes.

Mr. Lee took Mr. Goodman up on his suggestion, but he carried its implications much further.

Enter the Fantastic Four

In 1961, Mr. Lee and Mr. Kirby — whom he had brought back years before to the company, now known as Marvel — produced the first issue of The Fantastic Four, about a superpowered team with humanizing dimensions: nonsecret identities, internal squabbles and, in the orange-rock-skinned Thing, self-torment. It was a hit.

Other Marvel titles — like the Lee-Kirby creation The Incredible Hulk, a modern Jekyll-and-Hyde story about a decent man transformed by radiation into a monster — offered a similar template. The quintessential Lee hero, introduced in 1962 and created with the artist Steve Ditko (1927-2018), was Spider-Man.

A timid high school intellectual who gained his powers when bitten by a radioactive spider, Spider-Man was prone to soul-searching, leavened with wisecracks — a key to the character’s lasting popularity across multiple entertainment platforms, including movies and a Broadway musical.

Mr. Lee’s dialogue encompassed Catskills shtick, like Spider-Man’s patter in battle; Elizabethan idioms, like Thor’s; and working-class Lower East Side swagger, like the Thing’s. It could also include dime-store poetry, as in this eco-oratory about humans, uttered by the Silver Surfer, a space alien:

“And yet — in their uncontrollable insanity — in their unforgivable blindness — they seek to destroy this shining jewel — this softly spinning gem — this tiny blessed sphere — which men call Earth!”

Mr. Lee practiced what he called the Marvel method: Instead of handing artists scripts to illustrate, he summarized stories and let the artists draw them and fill in plot details as they chose. He then added sound effects and dialogue. Sometimes he would discover on penciled pages that new characters had been added to the narrative. Such surprises (like the Silver Surfer, a Kirby creation and a Lee favorite) would lead to questions of character ownership.

Mr. Lee was often faulted for not adequately acknowledging the contributions of his illustrators, especially Mr. Kirby. Spider-Man became Marvel’s best-known property, but Mr. Ditko, its co-creator, quit Marvel in bitterness in 1966. Mr. Kirby, who visually designed countless characters, left in 1969. Though he reunited with Mr. Lee for a Silver Surfer graphic novel in 1978, their heyday had ended.

Many comic fans believe that Mr. Kirby was wrongly deprived of royalties and original artwork in his lifetime, and for years the Kirby estate sought to acquire rights to characters that Mr. Kirby and Mr. Lee had created together. Mr. Kirby’s heirs were long rebuffed in court on the grounds that he had done “work for hire” — in other words, that he had essentially sold his art without expecting royalties.

In September 2014, Marvel and the Kirby estate reached a settlement. Mr. Lee and Mr. Kirby now both receive credit on numerous screen productions based on their work.

Turning to Live Action

Mr. Lee moved to Los Angeles in 1980 to develop Marvel properties, but most of his attempts at live-action television and movies were disappointing. (The series “The Incredible Hulk,” seen on CBS from 1978 to 1982, was an exception.)

Avi Arad, an executive at Toy Biz, a company in which Marvel had bought a controlling interest, began to revive the company’s Hollywood fortunes, particularly with an animated “X-Men” series on Fox, which ran from 1992 to 1997. (Its success helped pave the way for the live-action big-screen “X-Men” franchise, which has flourished since its first installment, in 2000.)

In the late 1990s, Mr. Lee was named chairman emeritus at Marvel and began to explore outside projects. While his personal appearances (including charging fans $120 for an autograph) were one source of income, later attempts to create wholly owned superhero properties foundered. Stan Lee Media, a digital content start-up, crashed in 2000 and landed his business partner, Peter F. Paul, in prison for securities fraud. (Mr. Lee was never charged.)

In 2001, Mr. Lee started POW! Entertainment (the initials stand for “purveyors of wonder”), but he received almost no income from Marvel movies and TV series until he won a court fight with Marvel Enterprises in 2005, leading to an undisclosed settlement costing Marvel $10 million. In 2009, the Walt Disney Company, which had agreed to pay $4 billion to acquire Marvel, announced that it had paid $2.5 million to increase its stake in POW!

In Mr. Lee’s final years, after the death of his wife, the circumstances of his business affairs and contentious financial relationship with his surviving daughter attracted attention in the news media. In 2018, Mr. Lee was embroiled in disputes with POW!, and The Daily Beast and The Hollywood Reporter ran accounts of fierce infighting among Mr. Lee’s daughter, household staff and business advisers. The Hollywood Reporter claimed “elder abuse.”

In February 2018, Mr. Lee signed a notarized document declaring that three men — a lawyer, a caretaker of Mr. Lee’s and a dealer in memorabilia — had “insinuated themselves into relationships with J. C. for an ulterior motive and purpose,” to “gain control over my assets, property and money.” He later withdrew his claim, but longtime aides of his — an assistant, an accountant and a housekeeper — were either dismissed or greatly limited in their contact with him.

In a profile in The New York Times in April, a cheerful Mr. Lee said, “I’m the luckiest guy in the world,” adding that “my daughter has been a great help to me” and that “life is pretty good” — although he admitted in that same interview, “I’ve been very careless with money.”

Marvel movies, however, have proved a cash cow for major studios, if not so much for Mr. Lee. With the blockbuster “Spider-Man” in 2002, Marvel superhero films hit their stride. Such movies (including franchises starring Iron Man, Thor and the superhero team the Avengers, to name but three) together had grossed more than $24 billion worldwide as of April.

“Black Panther,” the first Marvel movie directed by an African-American (Ryan Coogler) and starring an almost all-black cast, took in about $201.8 million domestically when it opened over the four-day Presidents’ Day weekend this year, the fifth-biggest opening of all time.

Many other film properties are in development, in addition to sequels in established franchises. Characters Mr. Lee had a hand in creating now enjoy a degree of cultural penetration they have never had before.

Mr. Lee wrote a slim memoir, “Excelsior! The Amazing Life of Stan Lee,” with George Mair, published in 2002. His 2015 book, “Amazing Fantastic Incredible: A Marvelous Memoir” (written with Peter David and illustrated in comic-book form by Colleen Doran), pays abundant credit to the artists many fans believed he had shortchanged years before.

Mr. Lee continued writing to the end. His first novel, “A Trick of Light,” written with Kat Rosenfield, is scheduled to be published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt next year.

Recent Marvel films and TV shows have also often credited Mr. Lee’s former collaborators; Mr. Lee himself has almost always received an executive producer credit. His cameo appearances in them became something of a tradition. (Even “Teen Titans Go! to the Movies,” an animated feature in 2018 about a DC superteam, had more than one Lee cameo.) TV shows bearing his name or presence have included the reality series “Stan Lee’s Superhumans” and the competition show “Who Wants to Be a Superhero?”

Mr. Lee’s unwavering energy suggested that he possessed superpowers himself. (In his 90s he had a Twitter account, @TheRealStanlee.) And the National Endowment for the Arts acknowledged as much when it awarded him a National Medal of Arts in 2008. But he was frustrated, like all humans, by mortality.

“I want to do more movies, I want to do more television, more DVDs, more multi-sodes, I want to do more lecturing, I want to do more of everything I’m doing,” he said in “With Great Power …: The Stan Lee Story,” a 2010 television documentary. “The only problem is time. I just wish there were more time.”

Correction: November 12, 2018

An earlier version of this obituary misstated the amount of money the Marvel movie “Black Panther” has made worldwide. It is more than $1.3 billion, not $426 million.

Correction: November 12, 2018

An earlier version of this obituary misstated the last year of the animated “X-Men” series that made its debut on Fox in 1992. It lasted until 1997, not 1995.

Daniel E. Slotnik contributed reporting

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

“Words like “mansplaining” and “gaslighting” were suddenly in heavy rotation, often invoked with such elasticity as to render them nearly meaningless. Similarly, the term “woke,” which originated in black activism, was being now used to draw a bright line between those on the right side of things and those on the wrong side of things. The parlance of wokeness was being used online so frequently that it began to strike me as disingenuous, even a little desperate. After all, these weren’t just meme-crazed youngsters flouting their newly minted critical studies degrees. Many were in their forties and fifties, posting photos from their kids’ middle school graduations along with rage-filled jeremiads about toxic masculinity. One minute they were asking for recommendations for gastroenterologists in their area. The next, they were adopting the vocabulary of Tumblr, typing things like I.Just.Cant.With.This., and This is some fucked, patriarchal bullshit, amiright?” - Meghan Daum

0 notes

Link

AMERICAN HIGHER EDUCATION has been about to ruin the country for a long time.

William F. Buckley first sounded the alarm in his 1951 jeremiad God and Man at Yale, and politicians and pundits have echoed him ever since. Soon and very soon, this chorus cries, in unison and across the years, tenured radicals will indoctrinate a generation. Today’s student protestors will capture the commanding heights of American politics and culture tomorrow. Taught to despise capitalism, religion, even Western civilization itself, they will imperil it all.

But the red brigades never take charge. Canonical authors survived the upheavals of the 1960s, and the political correctness craze of the 1990s. Outside of campus, a free enterprise system based on competition and self-interest survived both, too. Perhaps America has her right-wing Cassandras to thank. If not for the occasional broadside like Heather Mac Donald’s The Diversity Delusion: How Race and Gender Pandering Corrupt the University and Undermine Our Culture, every collegiate football game might begin with a rousing rendition of “The Internationale.”

Or maybe the Cassandras are wrong, and have always been wrong. As far back as 1963, University of California president Clark Kerr was already calling campus radicalism one of the “great clichés about the university.” No matter how wild Berkeley looked on the nightly news (or online today), “the internal reality is that it is conservative.” He was referring to academia’s internal organization, which was and remains steeply hierarchical. But higher education also plays a conservative role in American life. Consider academia’s history or social function at any length, and the cliché of the radical campus becomes difficult to believe. The real question is why it persists.

¤

With no less vigor than Buckley, Mac Donald charges higher education with corrupting the youth and endangering Western culture. While he decried atheism and collectivism, she singles out race and gender studies, which in her mind “dominate higher education.” Today “the overriding goal of the educational establishment is to teach young people […] to view themselves as existentially oppressed.” True to the old formula, Mac Donald warns that what happens on campus won’t stay on campus. Those who cry #MeToo and chronicle microaggessions will one day “seize levers of power.” The stakes, as always, couldn’t be higher: “[A] soft totalitarianism could become the new American norm.”

Trained as a lawyer, Mac Donald offers a one-sided brief, a classic polemic. The book is full of anecdotal evidence and statistical sleight-of-hand, with partial truths and gross distortions on almost every other page. Mac Donald is aghast, for example, when UCLA’s English Department drops its Shakespeare requirement, detecting “a momentous shift in our culture that bears on our relationship to the past — and to civilization itself.” She never mentions the department’s extensive historical requirements, or the fact that it will offer 16 courses on Shakespeare this academic year. Outside of higher education, the National Science Foundation is “consumed by diversity ideology” because it offers a few $1 and $2 million-dollar grants for implicit bias research and promoting women and minorities in STEM fields. For context, the NSF’s 2017 budget was $7.4 billion.

In any case, the real problems with the book go beyond shoddy sourcing. Start with the “dominance” of race and gender theory. Departments like African American and Women’s Studies tend to be relatively small, and although race and gender are popular topics across the humanities, an honest look at top university presses, as opposed to small and specialized journals, would find nothing close to dominance. (Harvard University Press’s winter catalog opens with a biography of Charles de Gaulle.) Nor are these issues omnipresent on campus. Mac Donald describes higher education as something like a one-party state, but aside from the occasional banner celebrating “diversity” or a poster asking students not to don a sombrero this Halloween, the supposed ruling party has a suspiciously light touch. From community colleges to the Ivy League, the vast majority of teaching and research proceeds without any reference to race or gender whatsoever.

But surely the professors are as radical as ever, poisoning young minds? It’s true that the professorate sits to the left of the general population, especially at selective liberal arts colleges. But in the most comprehensive survey of higher education available, conducted by the sociologists Neil Gross and Solon Simmons in 2007, more of the faculty was “moderate” (46 percent) than liberal (44 percent). And while 17.2 percent of older faculty claimed to be “liberal activists,” the percentage of young faculty members who said the same was minuscule: 1.3 percent. Even if the number of activist professors has grown since 2007, they aren’t necessarily radicalizing their students. A good deal of research suggests otherwise. According to the political scientist Mack Mariani and education specialist Gordon Hewitt, students become slightly more liberal during college, but no more than their non-collegiate peers do during the same time period. Fearsome as they seem to Mac Donald, student radicals are like their mentors: met more often online than on campus.

But wait, Mac Donald might reply, what about those posters and banners you mentioned? Like the ones at Berkeley reading “I will acknowledge how power and privilege intersect our daily lives,” or “I will be a brave and sympathetic ally.” Or what about Berkeley’s Division of Equity and Inclusion with its bulging staff and $20 million budget? In Mac Donald’s lone innovation to the campus polemic genre, she pays more attention to administrative press releases and campus decorations than she pays to professors’ books. Yet while diversity initiatives (and bunting) are indeed prevalent around many campuses, she misunderstands them. She believes that they reveal “the contemporary university’s paramount mission: assigning guilt and innocence within the ruthlessly competitive hierarchy of victimhood.” What they really reveal, although indirectly, is the present state of one of American higher education’s oldest and most intractable tensions.

Professors and administrators may consider themselves egalitarians, but especially in the top tiers, their schools create elites. As Paul Mattingly writes in American Academic Cultures: A History of Higher Education, colleges and universities have long been “highly selective devices for producing not only trained minds but also a social leadership class […] in a society formally committed to democratic equality.” Back in the early 1960s, Berkeley’s Kerr thought he had a way to ease this tension between elitism and democracy. “The great university is of necessity elitist — the elite of merit — but it operates in an environment dedicated to an egalitarian philosophy.” This prompted a question: “How may an aristocracy of intellect justify itself to a democracy of all men?”

Yale and Harvard once groomed the sons of the nation’s great families, Bushes and Cabots and so on. In postwar America, Berkeley would justify itself on the grounds that it produced “the elite of merit,” a meritocracy. Kerr’s vision of the university is now a reality. A college degree is all but necessary for entry into managerial, professional, or creative fields, which comprise the heart of the nation’s upper middle classes.

The trouble is that in order for a meritocracy to be fair, the competition has to take place on a level playing field: in order to have true equality of opportunity, one’s background shouldn’t determine where one ends up in life. In the United States, it largely does. According to studies headed by the economist Raj Chetty, America’s social mobility rate lags behind that of Canada, Denmark, and even the United Kingdom, a famously class-bound society. Although college admissions looks like a level playing field (anyone can apply to Harvard), SAT scores follow family income, and the overall admissions process favors those who can pay the sticker price, even after taking affirmative action into account.

Once enrolled in selective institutions, students compete with each other again — for grades, prestigious extra-curricular positions, and internships. They build social networks and learn to work and behave in line with the norms of the upper middle class. After graduation the victors, bedecked with honors, can pursue lucrative careers, or even rise to positions of prominence in American public life. But despite all that competition, a 2015 Pew study still found that “a family’s economic circumstances play an exceptionally large part in determining a child’s economic prospects later in life.” To the extent that its sorting process reflects existing inequalities, higher education can’t help but replicate and thereby reinforce inequalities in society at large. There’s a word for an institution that does that, and it isn’t radical.

In this context, diversity banners are not evidence of Maoism on the march. They are evidence of an institution whose ideals are at odds with its social function. Few in higher education want to work in a laundering operation that exchanges parental capital for students’ social capital so that they can turn it back into material capital again. The promise of affirmative action is that it will work against this tendency, at least a little. Affirmative action policies often assist students from poor families, and after college they do about as well as their wealthier peers.

There’s a rich irony at the heart of the old radical campus cliché. During the postwar period, conservatives feared that higher education was fomenting leftist revolution. In reality, elite institutions like Berkeley and Yale were enshrining meritocracy as the official rule of American life, while more quietly preserving the advantages that come with money. Higher education prepares students to succeed within a competitive, stratified American society, not change it. The fear is always that today’s radicals will implement their ideas tomorrow. Or, in Mac Donald’s words, “a pipeline now channels left-wing academic theorizing into the highest reaches of government and the media.” But will those who attain “the highest reaches of government and media” really be interested in tearing the heights down? It didn’t happen in the 1960s. It didn’t happen in the 1990s. Don’t count on it this time, either.

So why does Mac Donald insist otherwise? Why are conservatives still so afraid of higher education after all these years? Most obviously, demagoging higher education works political wonders. It’s not only Buckley and Mac Donald who sell books against higher education; politicians from Nixon and Reagan to Scott Walker and Donald Trump have sold their campaigns that way, too. While lambasting egg-headed professors, they can both pose as populists and promise tax cuts for the rich.

Even more, though, precisely because higher education turns out the American elite, small disturbances in academia resonate deeply within the conservative soul. The political theorist Corey Robin has argued that reactionaries draw their energy from “the felt experience of having power, seeing it threatened, and trying to win it back.” Whether it’s Burke horrified by the fall of the Bourbons, or Buckley opposing the Civil and Voting Rights Acts, conservative movements thrive on imminent threats to existing hierarchies. Imperiled, they sound the alarm, rally the troops, man the battlements, and eventually ride out to conquer. Robin has suggested that, despite its seeming strength, American conservatism is actually in disarray because it lacks a worthy antagonist. Numerically speaking, the socialist left is tiny, while the Democratic Party embraces “market-based” solutions to health care scarcity and global warming. Without a suitable enemy, the whole movement could collapse.

But what’s that sound? A handful of protestors on the quad? They’ve arrived in the nick of time! Never mind that they’ve been showing up since the 1950s. This time, it’s different. This time, the threat to “our culture” is real. If so, then even modest reforms — meant to do nothing more terrible than diversify the upper middle class — must be opposed as if they were threats to civilization itself.

¤

Paul W. Gleason teaches in the religion departments of California Lutheran University and the University of Southern California. In 2017, he received the National Book Critics Circle’s “emerging critic” award.

The post Why Are Conservatives So Afraid of Higher Education? appeared first on Los Angeles Review of Books.

from Los Angeles Review of Books http://bit.ly/2SJeHaT

0 notes

Text

BEIJING | Now with power to long rule China, Xi beset by challenges

New Post has been published on https://is.gd/KR0mb4

BEIJING | Now with power to long rule China, Xi beset by challenges

BEIJING — As China’s leaders gather for their annual Yellow Sea retreat, the country’s political waters are looking choppy.

Chinese President and ruling Communist Party leader Xi Jinping is beset by economic, foreign policy and domestic political challenges just months after clearing his way to rule for as long as he wants as China’s most dominant leader since Mao Zedong.

Mounting criticism of the Xi administration’s policies has exposed the risks he faces from amassing so much power: He’s made himself a natural target for blame.

“Having concentrated power, Xi is responsible for all policy setbacks and policy failures,” said Joseph Cheng, a retired City University of Hong Kong professor and long-time observer of Chinese politics.

Notably, Xi used to dominate state-run newspapers’ front pages and the state broadcaster CCTV’s news bulletins on a daily basis but has in recent weeks made fewer public appearances. “He can’t shift the blame, so he’s responding by taking a lower profile,” Cheng said.

The challenges so far aren’t seen as a threat to Xi’s grip on power, but for many Chinese, the government’s credibility is on the line.

Of greatest concern to many is the trade war with the U.S. that threatens higher tariffs on hundreds of billions of dollars of Chinese exports. Critics say they’ve yet to see a coherent strategy from Beijing that could guide negotiations with Washington and avoid a major blow to the economy. Beijing instead seems to be opting for defiance and retaliatory measures of its own.

Both the stock market and the currency have weakened in response and the Communist Party itself conceded at a meeting last month that external factors were weighing heavily on economic growth.

At the same time, a scandal over vaccines has reignited long-held fears over the integrity of the health care industry and the government’s ability to police the sprawling firms that dominate the economy.

“Trust is the most important thing and a loss of public confidence in the government could be devastating,” said Zhang Ming, a retired professor of political science in Beijing.

And last week, the authorities mobilized a massive security effort to squelch a planned protest in Beijing over the sudden collapse of hundreds of peer-to-peer borrowing schemes that underscore the government’s inability to reform the finance system to cater to small investors.

Meanwhile, Xi’s signature project, the trillion-dollar “Belt and Road” initiative to build investment and infrastructure links with 65 nations, is running into headwinds over sticker shock among the countries involved. Some Chinese have also questioned the wisdom of sending vast sums abroad at a time when millions of Chinese remain mired in poverty.

That in part plays into concerns over Xi’s abandonment of the highly pragmatic, low-key cautious approach to foreign relations advocated by Deng Xiaoping, the architect of China’s economic reforms that laid the groundwork for today’s relative prosperity.

Leaders are likely to discuss at least some of these challenges during informal discussions at the Beidaihe resort in Hebei province as part of a tradition begun under Mao. Xi and others generally drop out of sight for two weeks or more during the summer session.

Xi’s mildly bombastic brand of Chinese triumphalism “has not been popular with many in the party,” leading critics to speak out, said Steve Tsang, director of the China Institute at London’s School of Oriental and African Studies.

Some have even called for the sacking of one prominent proponent of the rising China theme, Tsinghua University economist Hu Angang, with 27 graduates of the elite institution signing a letter to that effect.

Resentment lingers also over Xi’s moves to consolidate power, including pushing through the removal of presidential term limits in March and establishing a burgeoning cult of personality.

That resentment was given voice in a lengthy jeremiad titled “Imminent Fears, Imminent Hopes” penned by Tsinghua University law professor Xu Zhangrun, who warned that, “Yet again people throughout China … are feeling a sense of uncertainty, a mounting anxiety in relation both to the direction the country is taking as well as in regard to their personal security.”

“These anxieties have generated something of a nationwide panic,” Xu continued before listing eight areas of concern including stricter controls over ideology, repression of the intelligentsia, excessive foreign aid and “The End of Reform and the Return of Totalitarianism.”

Even more boldly, Xu called for a restoration of presidential term limits and a re-evaluation of the 1989 pro-democracy movement centered on Beijing’s Tiananmen Square. The peaceful protests were crushed by the military and remain a taboo topic to this day.

Although Xu is reportedly out of the country and has not been officially sanctioned, another longtime critic, retired professor Sun Wenguang, found himself carted off by police in the middle of a radio interview with the Voice of America in which he railed against China’s lavish spending abroad.

A sign of the Xi administration’s anxieties is a new campaign to promote patriotism among intellectuals — a recurring tactic when public debate is seen as needing a course correction.

The notice of the new campaign, issued July 31, cites “the broad masses of intellectuals” and the “patriotic spirit of struggle,” while giving little in the way of specifics.

Much of the discontent with Xi can be traced to his administration’s perceived ineffectiveness, said Zhang, the retired academic.

“If you want to be emperor, you must have great achievements,” Zhang said. “He hasn’t had any, so it’s hard to convince the people.”

By CHRISTOPHER BODEEN , Associated Press

#Beijing#challenges#Chinese President#Communist Party leader#Mao Zedong#Mounting criticism#political challenges#political waters#Resentment lingers#rule China#TodayNews#Xi administration

0 notes

Text

graduate school application fees have me carefully plotting out how exactly to make $78 in groceries last three weeks. I thought the stressful part would be over once I submitted my last application (which I did yesterday! I am very proud of myself!) but no the financial fallout is just beginning

#I’ll be fine- I’m really lucky my girlfriend’s family is so kind and packed me a bunch of frozen venison#And snacks and all manner of other good food. So that will go a long way#Plus while cleaning out the freezer my housemates and I found a big bag of Lima beans I had forgotten about that’s still good#Which means I’ll still get vegetables in without having to spend money on fresh produce#But gddamn I’m really feeling the expenses pile up- on top of other things like vet bills and money for tickets to fly out to a conference#at the end of this month (although maybe I get get my school to reimburse me for that#I need to get on it). I am proud to have gotten a talk slot though! And I am grateful to be able to pay the application fees at all#Even if it hurts a bit. But also perhaps the system is a bit broken if you need to shell out this much for the privilege of being rejected#(probabilistically speaking)#*sigh*#vent#graduate school jeremiad#personal#finances cw#food cw

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

does anyone have any advice on how to smash rabid perfectionism with a hammer? Particularly with regard to emails? asking for myself

#it is an insidious beast. I would like to sleep but I cannot sleep until I send the email#and I cannot bring myself to send the email even though it's fine. ish. or at least not getting any better. so I'm stuck#vent#graduate school jeremiad#(it is a graduate school email which means it is even WORSE than a classic email)#(graduate school emails are like. email boss fights)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

it would be really cool if I could have a day this month where I wasn’t so chronically afraid it felt like my intestines were twisted into a möbius strip. Because ya’know- I really like my digestive tract being an orientable manifold. If that’s all the same to the universe.

#it’s the grad school applications I think. It’s really really getting to me#I just. I dunno. It’s hard to eat. Sleep. Talk to people. I try my best but yeah. This is most of what I think about all the time.#Is it normal to feel this bad because of them? Like is this typical levels of graduate school application stress?#The stakes feel so high even though I know they’re not. If I don’t get in I just apply for a job and then reapply to grad school later#But I think it goes deeper than that. The idea of grad school applications has got me really closely examining myself and…#I genuinely worry I’m just- a kinda mediocre mathematician at best#I’ve been starting to feel really insecure about how slow my processing speed is. Would anyone want to invest in someone like me??#Who does legitimately have disabilities that make efficiently solving problems harder for me than most?#My dad once told me I’m not capable of thinking like a mathematician. Because I’m so slow. He encouraged me not to major in it.#I’m really happy I disregarded him. I can’t imagine doing anything else. I love math and I love research. But I wonder if he was right#I guess it doesn’t matter. I don’t care. I’m going to do math whether I’m cut out for it or not. And if that has to be recreational#Because no graduate school wants me. Then so be it.#But I do really want to go to graduate school. I really love the grad level classes I’ve done.#I really hope I make it#vent#graduate school jeremiad#research jeremiad

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I swear my advisor is really fucking healing to talk to. Today started off wretchedly (my second graduate school rejection arrived in my inbox, and I haven't received any acceptances as yet) but then I had my research meeting with him and I feel so much lighter now.

He liked my thesis draft!!! and did actually really reassure me about graduate school admissions. So I think things will be okay

#he is just- a wonderful wonderful man#graduate school jeremiad#except like. a hopeful jeremiad? do those exist?#personal

1 note

·

View note

Text

Finally managed to schedule send the two emails that caused multiple stress induced meltdowns in a single day! Now to never check my email inbox ever again so I don't have to subject myself to the mortifying ordeal of knowing the reply!

#I owe most of it to my girlfriend who helped me draft it and motivated me through the process because#GD I needed it#Haven't written an email this anxiety inducing in a long time#(it was rec letter requests which. Terrifying. Asking people for stuff is abjectly terrifying)#But I did it#by the power of Gd and gayness I did it#That is why my girlfriend is the coolest#personal#vent#grad school jeremiad#<- my tag for lamenting about graduate school application stuff

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

BEIJING | China's Xi beset by economic, political challenges

New Post has been published on https://is.gd/XLdwMV

BEIJING | China's Xi beset by economic, political challenges

BEIJING — As China’s leaders gather for their annual Yellow Sea retreat, the country’s political waters are looking choppy.

Chinese President and ruling Communist Party leader Xi Jinping is beset by economic, foreign policy and domestic political challenges just months after clearing his way to rule for as long as he wants as China’s most dominant leader since Mao Zedong.

Mounting criticism of the Xi administration’s policies has exposed the risks he faces from amassing so much power: He’s made himself a natural target for blame.

“Having concentrated power, Xi is responsible for all policy setbacks and policy failures,” said Joseph Cheng, a retired City University of Hong Kong professor and long-time observer of Chinese politics.

Notably, Xi used to dominate state-run newspapers’ front pages and the state broadcaster CCTV’s news bulletins on a daily basis but has in recent weeks made fewer public appearances. “He can’t shift the blame, so he’s responding by taking a lower profile,” Cheng said.

The challenges so far aren’t seen as a threat to Xi’s grip on power, but for many Chinese, the government’s credibility is on the line.

Of greatest concern to many is the trade war with the U.S. that threatens higher tariffs on hundreds of billions of dollars of Chinese exports. Critics say they’ve yet to see a coherent strategy from Beijing that could guide negotiations with Washington and avoid a major blow to the economy. Beijing instead seems to be opting for defiance and retaliatory measures of its own.

Both the stock market and the currency have weakened in response and the Communist Party itself conceded at a meeting last month that external factors were weighing heavily on economic growth.

At the same time, a scandal over vaccines has reignited long-held fears over the integrity of the health care industry and the government’s ability to police the sprawling firms that dominate the economy.

“Trust is the most important thing and a loss of public confidence in the government could be devastating,” said Zhang Ming, a retired professor of political science in Beijing.

And last week, the authorities mobilized a massive security effort to squelch a planned protest in Beijing over the sudden collapse of hundreds of peer-to-peer borrowing schemes that underscore the government’s inability to reform the finance system to cater to small investors.

Meanwhile, Xi’s signature project, the trillion-dollar “Belt and Road” initiative to build investment and infrastructure links with 65 nations, is running into headwinds over sticker shock among the countries involved. Some Chinese have also questioned the wisdom of sending vast sums abroad at a time when millions of Chinese remain mired in poverty.

That in part plays into concerns over Xi’s abandonment of the highly pragmatic, low-key cautious approach to foreign relations advocated by Deng Xiaoping, the architect of China’s economic reforms that laid the groundwork for today’s relative prosperity.

Leaders are likely to discuss at least some of these challenges during informal discussions at the Beidaihe resort in Hebei province as part of a tradition begun under Mao. Xi and others generally drop out of sight for two weeks or more during the summer session.

Xi’s mildly bombastic brand of Chinese triumphalism “has not been popular with many in the party,” leading critics to speak out, said Steve Tsang, director of the China Institute at London’s School of Oriental and African Studies.

Some have even called for the sacking of one prominent proponent of the rising China theme, Tsinghua University economist Hu Angang, with 27 graduates of the elite institution signing a letter to that effect.

Resentment lingers also over Xi’s moves to consolidate power, including pushing through the removal of presidential term limits in March and establishing a burgeoning cult of personality.

That resentment was given voice in a lengthy jeremiad titled “Imminent Fears, Imminent Hopes” penned by Tsinghua University law professor Xu Zhangrun, who warned that, “Yet again people throughout China … are feeling a sense of uncertainty, a mounting anxiety in relation both to the direction the country is taking as well as in regard to their personal security.”

“These anxieties have generated something of a nationwide panic,” Xu continued before listing eight areas of concern including stricter controls over ideology, repression of the intelligentsia, excessive foreign aid and “The End of Reform and the Return of Totalitarianism.”

Even more boldly, Xu called for a restoration of presidential term limits and a re-evaluation of the 1989 pro-democracy movement centered on Beijing’s Tiananmen Square. The peaceful protests were crushed by the military and remain a taboo topic to this day.

Although Xu is reportedly out of the country and has not been officially sanctioned, another long-time critic, retired professor Sun Wenguang, found himself carted off by police in the middle of a radio interview with the Voice of America in which he railed against China’s lavish spending abroad.

A sign of the Xi administration’s anxieties is a new campaign to promote patriotism among intellectuals — a recurring tactic when public debate is seen as needing a course correction.

The notice of the new campaign, issued July 31, cites “the broad masses of intellectuals” and the “patriotic spirit of struggle,” while giving little in the way of specifics.

Much of the discontent with Xi can be traced to his administration’s perceived ineffectiveness, said Zhang, the retired academic.

“If you want to be emperor, you must have great achievements,” Zhang said. “He hasn’t had any, so it’s hard to convince the people.”

By CHRISTOPHER BODEEN , Associated Press

#Beijing#Chinese President#Communist Party leader#discontent#Having concentrated#Mounting criticism#political challenges#Tiananmen Square#TodayNews#Xi administration

0 notes