#gender history

Text

I'm reading a book named "A Guide to The Correction of Young Gentlemen Or, The Successful Administration Of Physical Discipline To Males, By Females" - essentially, a fantasy femdom BDSM book, written in 1924 by Alice Kerr-Sutherland but first published in 1991.

It has some genuinely fascinating stuff to say about gender, and I feel like it's worth looking at/thinking about in the context of Historical Gender Stuff. This 100 year old book has the following to say:

"The truth is that some young gentlemen would rather they had been born young ladies: they cannot admit this openly, because in the male world to confess as much would lead to instant ostracism if not worse; but they cannot conceal it either, and by preferring the company of girls, and soft, feminine clothing, and by flinching during the rough pursuits to which all boys, willing or no, are occasionally heirs, they attract opprobrium."

"Such boys weep too readily for their fellows' tastes - weeping is a great crime among boys unless it is generally admitted that circumstances left little choice - and are hounded for that reason."

"Just as there are girls who had rather been boys - we all know examples of the type - there are boys who, in a kinder world, would have been born into the gender more suited to their dispositions."

"Many young people of this sort are riven with a guilt they do not deserve but have been forced, by the conventions of society, to adopt; they are confused, ashamed and thoroughly unhappy."

"The ideal thing to do would be to treat these cases on their merits, send them to girls' schools, and so on. (The same thing should happen with those girls who would rather be young gentlemen.) Boys of this sort are girls in any case-in all respects save one."

"Most subjects of this sort have a secret name - a girl's name."

19K notes

·

View notes

Text

"Lively and deeply researched, this remarkable study is an insightful contribution to histories of modernity, comparative performance studies, and culture and gender studies in which the simple act of dressing is a struggle over how the future is imagined.”

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today is the 80th Anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising

In honor of this event, and Monday’s observance of Yom HaShoah, I’m posting a roundup of all of my writings, spanning 2011-Yesterday, on the topic of Jewish women, the Holocaust, the Warsaw Ghetto, and resistance.

A profile of Hannah Szenes, a Hungarian Jewish paratrooper who worked behind Nazi lines in services of the SOE (Special Operations Executive, same as Noor Inayat Khan).

Why Gender History is Important, Asshole. The post that started it all, that made me realize how many of you are passionately curious about the topic of women and the Holocaust, and how many of you share my righteous indignation over the fact that this knowledge is so uncommon.

We need to talk about Anne Frank: a thinkpiece about how we use and misuse the memory of Anne Frank. NOT a John Green hitpiece; if that’s your takeaway you’re reading it wrong.

An 11-part post series about Vladka Meed, a Jewish resistance worker who smuggled explosives into the Warsaw Ghetto in preparation for the Uprising, and set up covert aid networks in slave labor camps, among other things.

Girls with Guns, Woman Commanders, and Unheeded Warnings: Women and the Holocaust: an assessment of how Holocaust memory is shaped by male experiences, and an analysis of what we miss through this centering of the male experience.

Filip Muller’s testimony regarding young women’s defiant behavior in the gas chambers of Auschwitz. [comes with big trigger/content warning]

Tema Schneiderman and Tossia Altman: Voices from Beyond the Grave; paper presented at the Heroines of the Holocaust: New Frameworks of Resistance International Symposium at Wagner College.

A meditation/polemic on Jewish women, abortion, and the Holocaust, and the American Christian far-right’s misuse of Holocaust memory in anti-choice rhetoric. [comes with big trigger/content warning]

Women and the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising; talk presented at the National World War II Museum’s 15th International Conference on World War II.

Women of the Warsaw Ghetto; keynote speech delivered at the Jewish Federation of Dutchess County’s Yom HaShoah Program in Honor of the 80th Anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising.

#warsaw ghetto uprising#jewish women#women and the holocaust#warsaw ghetto#jewish history#holocaust#holocaust history#women's history#gender history

337 notes

·

View notes

Photo

"Charlotte Cushman was an icon of 19th century theatre, competing on equal footing with the greatest male actors of the age and winning a loyal following across the United States and Europe. While Cushman played both male and female roles, she was best known for her male roles including Romeo, Hamlet, and Cardinal Wolsey in Shakespeare's Henry VIII. On stage and off, Cushman challenged conventions of gender and sexuality. In her adult life, she lived in a community of what she called 'jolly female bachelors' or 'emancipated women,' known for producing art, wearing men's clothing, and lobbying for working women."

#Charlotte Cushman#19th century#queer history#gender history#19th century theatre#actress#lgbtq#lgbt#lgbt+#lgbtq+#theatre#Shakespeare

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

I am reading McPhee's bio on Robespierre and somehow only now I realize his maternal grandmother was 39 when she married and 42 when she had Jacqueline.

I keep finding more and more 18century women who married in their 30s and had children in late 30s/early 40s: Mme Duplay too. Tallien's mother. Also SJ's mother but she is young in comparison since she was in her early 30s.

So that's interesting. For some reason, I assumed a woman was considered past her prime marriageable age by late 20s and that would seriously harm her chances at finding a suitable/good match (vs marrying men who are not ideal candidates but would accept an older bride because beggars can't be choosers). But this doesn't seem to be the case? (At least not among these examples).

I know Mme Roland said in her memoirs that she married kind of late-ish (25-26) but it seems that staying unmarried into 30s was not an absolute catastrophe (if marriage was a goal, and what else could you do realistically). It lowered your chances significantly, yes, but if you wanted a husband and children there was still a chance, and seems like you wouldn't have to settle for someone who was seen as a poor match (as in, someone you wouldn't want to marry if you had a chance to marry in your 20s).

So all in all, it puts a different perspective on my fav spinster. I always assumed Charlotte Robespierre was seen as way (way) too old for marriage during frev, but she was 34 when her brothers died, and it wasn't that old. So what if Thermidor ruined her marriage chances? Look: I have no idea if she even wanted to marry - none of the siblings ever married. (Though she claims she had accepted Joseph's proposal so I guess she wouldn't reject marriage). But it does put into the perspective the whole "jealous spinster" narrative surrounding Charlotte.

(Or maybe I am wrong and marriages in your 30s were a rarity but there are honestly more of them than I expected. In any case, I don't see Charlotte settling for someone just to be married but maybe I am wrong about that, too.) Thoughts?

#also therese gellé's mother was 30 when she had her but only married at 42#but still another case of a woman unmarried at 30#frev#18th century#gender history#charlotte robespierre#robespierre

93 notes

·

View notes

Note

where women expected to shave their legs and chest body hair in the French court? Or even the English? I read medieval it wasn’t expected but I don’t know about the later renaissance

Women shaving their legs and pits wasn’t really a thing until the 20th century.

Now, depilatories were a thing but mostly for facial hair...and pubes, but generally only for sex workers to distinguish them from “proper” women. While this isn’t something that modern audiences pick up on, there is something of an odd anachronism when period pieces show high-status women who are shaved in sex scenes.

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

listen: two genders, but the two are hunters and gatherers.

genitalia? we don't care about such things in our caveman-cavewoman-and-caveenby society. do you have long legs? can you run, like, real fast? that's all that matters. if you are born a gatherer but have long legs and big lungs and strong muscles or know what to do with a bow and a spear, you are... shit, who said you even were a gatherer? who the hell assignes you a profession at birth, that's crazy. anyways, if you don't have these, but instead have large palms and long fingers and a lot of back strength and good vision or know a lot about plants, the community of gatherers welcomes you.

and if you happen to have neither... then... well... you see there are some seeds on the ground... wait, what are you doing. you are supposed to eat those, not plant them. what does it even mean. stop it. STOP IT. sigh congrats we now have 0 seeds AND patriarchy.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

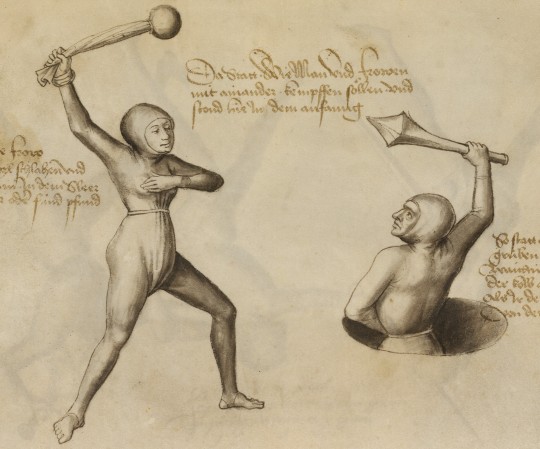

a woman and a man competing in a medieval judicial duel. the man is standing in a pit to even out their chances of winning

detail from Hans Thaldorfer's "Fechtbuch" (martial arts manual), german manuscript, 1467

source: München, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Cod. icon. 394 a, fol. 122v and 124v

#medieval#medieval illustrations#fechtbuch#medieval manuscripts#martial art#history of law#gender history#15th century#gender

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

"American white women also stressed the need for new forms of dress that they believed would help to clean and protect indigenous women and be more suitable to their transformed role within the home. Indian women who had worn loose clothing that was adapted to their work of growing and gathering food also needed to be fitted into more appropriate attire. Some of the new clothing promoted as cleaner and more helpful actually imposed new restrictions on indigenous women's movement, and was even opposed by women's dress reform advocates. For example, Walter West, a Southern Ute Reservation superintendent, requested funds from the government in 1916 to buy corsets for Indian girls to improve the 'general health and appearances of the girls.'"

-Margaret D. Jacobs, White Mother to a Dark Race: Settler Colonialism, Maternalism, and the Removal of Indigenous Children in the American West and Australia, 1880-1940 (Lincoln: University of of Nebraska Press, 2009), 309.

#gender history#colonialism#indigenous history#history#me tapping the sign#'you cannot talk about corsets or women's dress without connecting it with larger ideas of empire and colonialism'

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

guys you do NOT want to know how the guy who popularised the difference between gender and sex came to popularise it, it is one of the most disgusting thing’s I’ve ever had the misfortune to read. I’ve read a LOT of psychology experiments too. The psychologist coined the terms gender roles and sexual orientation. It was a sweedish guy who coined the term gender identity though

In 1968, Stoller wrote Sex and Gender, where he hypothesized "The sense of core gender identity...is derived from three sources: the anatomy and physiology of the genitalia; the attitudes of parents, siblings and peers toward the child's gender role; and a biological force that may more or less modify the attitudinal (environmental) forces."

Interesting for something from 1968! I believe all these things definitely come into play some way or another. Although Robert Stoller would end up condoning conversion therapy and attempting to erase the the idea of sexual perversions, blaming it on gender identity. These psychologists, am I right? Even next to Frued, they don’t look too great

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reading for my EMA (externally-marked assignment) and I just came across this:

“Duden’s close examination of the casebooks an early eighteenth-century German physician, Johann Storch (1681–1751), kept on his female patients, allows us a fascinating glimpse into how people, and especially women, sensed the workings of their bodies. Storch and his female patients accepted the basic opacity of the body; its interior remained inaccessible. His patients spoke most frequently of the osmotic and fluid processes they felt viscerally. They tied femaleness, for instance, to no particular organ, neither to womb nor breasts. Rather, rhythms and periodicity – menstruation, for instance – defined the female. For them, the mental and physical permeated each other, and they viewed the body as easy prey to outside influences that could permanently alter it.” (Mary Lindemann, Medicine and Society in Early Modern Europe, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

And all I can think is quite how infinitely more accurate, useful and subtle this is as an understanding of sex and gender, from a number of white Europeans living in the early 18th century, of various genders (though I would guess mostly from the middle and upper classes) when general human understanding of anatomy and medicine was much less complete than it is now and people of their cultural background were still highly affected by humoural theory, than the oversimplified-to-the-point-of-meaninglessness bullshit TERFs keep putting out in the present day.

It’s a long way from *perfect*, don’t get me wrong; it’s still very based on a binary. But it has room for the messy realities and complexities of existence and the bizarre experience of being embodied.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lillian Harman, anarchist feminist

Harman, an anarchist feminist, was born in Missouri in 1869. She campaigned in support of sexual freedom and for marriage outside the bounds of state and church control. Harman criticised the ways the state used marriage to enforce women's legal subservience to their husbands. She entered a "free marriage" (getting married without any legal documentation and keeping her surname). For this, Harman was sent to prison for contravening the 1867 Kansas Marriage Act. After this, she continued to push for sexual freedom and to publish anarchist feminist works.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The first Bond movie and the first Beatle single, Dr No and "Love Me Do", were both issued on October 5, 1962, and from this remarkable coincidence, John Higgs weaves a daring, dazzlingly entertaining pop cultural critique. It’s smart and analytical, yes, but it’s also enormously good fun. There’s something provocative or revelatory on every page."

#uwlibraries#history books#british history#cultural history#gender history#history of music#history of film

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Voices From Beyond the Grave: Tema Schneiderman and Tossia Altman; paper presented at the Heroines of the Holocaust Symposium

Many of you requested it, and the conference organizers gave me the all clear to post it here. Please note that this was written for an audience already conversant in the admittedly niche sub-subfield.

Voices From Beyond the Grave: Tema Schneiderman and Tossia Altman

“Over 20 times she crossed borders that separated different parts of Poland…Tema visited every ghetto, knew Jewish life and troubles in every town and city. She was a living treasure of information… She brought messages from the movement to every area…Even Poles and Germans could not reach every part of Poland as she did. And when she came, there was such joy.”

-Mordechai Tennenbaum, leader of the Jewish resistance in the Bialystok Ghetto, and boyfriend of Tema Schneiderman.1

“Tossia came. It was like a blessing of freedom. Just the information that she came. It spread among the people. That we have Tossia visiting us from Warsaw. As if there was no ghetto. As if there were no Germans. As if there was no death around. As if we were not in this terrible war. A beam of love. A beam of light.”

-Rushka Korczak, member of the Vilna Jewish underground, and comrade of Tossia Altman.2

Part of the reason we’re all here is because we see the silences and gaps in Holocaust memory where the stories, narratives, and experiences of all the women we’re discussing this week should be. We want to do our parts to fill in those gaps, and we all go about that differently.

This paper comes about as part of a larger work of public-facing narrative history focused on Zivia Lubetkin, Vladka Meed, Rachel Auerbach, Tossia Altman, and Tema Schneiderman that I’ve been working on for the past 5 years. Zivia, Vladka, and Rachel survived the war, wrote about their experiences, and gave their testimonies. Tema and Tossia were murdered in 1943. What they left in the way of writings are political essays and coded letters; which were not spaces in which they could be unguarded and candid.

Through writing a narrative history based not simply on action, but on personality and emotion, I aim to do my part to fill in the gap by presenting these women to general readers as not simply courageous heroines, but as distinct individuals; people readers can grow to care about beyond simply a recitation of their accomplishments. For many laypersons, Anne Frank is the only female experience, or narrative they associate with the Holocaust, and that is because she is a figure they feel they can connect with. People can read her diary and feel that they know her, that they can see her; who she was, who she wanted to be, who she could have been.

Finding hints of personality reconstructed through secondary sources, public letters, and the writings of others is an imprecise art, but if we gather enough of those hints, we can present these women to students, readers, and other lay audiences as fully formed human beings, and give that population something, someone to connect with.

And this brings me back to Tema and Tossia. Due to the limited and/or public nature of their extant writings, we have only the diaries, memoirs, oral histories, and testimonies of their peers and comrades who a. survived, or b. wrote a diary which survived the Holocaust, even if its writer did not. This in turn leads me to the central question: how do we as historians reconstruct personalities through the writings of others? This is the question I will attempt to answer in this time, using Tema Schneiderman and Tossia Altman as case studies.

We know that memoirs, autobiographies, and oral histories are imperfect sources. Their narratives are invariably shaped and influenced by time, trauma, politics, and personal considerations. As a result, we must individually assess and contextualize each source of this type in order to adjust for these mis-recollections and omissions.

That said, while a singular memoir must be rigorously interrogated, a collection of memoirs all recounting the same set, or sets, of events can, together, paint an accurate picture of personalities and events where individual testimonies may not. And this very much holds true for the numerous memoirs, autobiographies, testimonies, and oral histories we have from Polish Jewish underground workers, denizens of the Warsaw Ghetto; and specifically, survivors of the Warsaw Ghetto and its Uprising.

Tossia Altman and Tema Schneiderman were vital members of the Polish Jewish underground. They were couriers who traveled to Jewish ghettoes across and beyond the General Government, delivering documents, money, and information to their far-flung comrades; they were both Zionists, albeit within different movements; and they both fell in 1943.

Because of the importance of their work to the resistance, these two women are frequently mentioned in the diaries, memoirs, and testimonies of their peers and comrades. Please note here that the writing and research for the larger project this paper emerged from is ongoing, and I’m still in the process of acquiring and translating a wide variety of sources.

That said, I’d like to begin this analysis first by presenting each woman’s biography with a quick overview of their resistance work, followed by a discussion of what we can glean from the sources regarding their personalities and inner lives. I will begin with Tema Schneiderman, and then move on to Tossia Altman.

Tema Schneiderman was born in Warsaw in 1917 to a Polish-speaking Jewish family.3 She studied nursing and worked at a hospital after graduating from a Polish public high school.4 It was during this period of her life that she met her future boyfriend, Mordechai Tennenbaum, who brought her into the Dror movement.5

Most of her family was killed the September 1939 invasion of Poland.6 During the first years of the war, Tema worked as an underground courier.7 Some of her exploits include organizing the Jewish underground in Bialystock, and forging identity papers for Jews in hiding.8 On January 11, 1943 Tema traveled to Warsaw to deliver documents to allies in the Polish Underground; money, and instructions regarding the manufacture of homemade explosives to the Jewish Fighting Organization.9 Two days later, she sent a telegram to her comrades verifying her arrival in Warsaw.10 She then, most likely entered the Warsaw Ghetto on the same day as she sent the telegram. She disappeared five days later during the “Little Uprising” of January 18, 1943.11 She was most likely killed in a roundup, or in the fighting.12

One essay authored by her survives, signed with the initials of her Aryan alias, Wanda Majewska. Titled “In the Path of Hitlerite Bestiality,” she wrote it to serve as propaganda for German soldiers.13

Nearly everyone who wrote about Tema Schneiderman did so in glowing terms, focusing on her beauty and vivacity with loving descriptions of her hair, eyes, and clothing. They also tended to refer to her as “Mordechai Tennenbaum’s girlfriend.” This identification of women in terms of the men they were romantically attached to is not unusual in this grouping of memoirs—written by both men and women—but it is still noteworthy here. Indeed, underground courier and future Knesset-member Chaika Grossman wrote the following in her memoir, The Underground Army: Fighters of the Bialystok Ghetto:

“In the afternoon Tema and I went to the nuns’ restaurant, where meals were cheap and one could take food home ... Tema decided to go into the ghetto. She insisted, and I could not dissuade her. I had barely gotten used to this deli¬cate girl. At first I believed that she was a spoiled child and would not be able to hold out. I don’t know why I always thought her more fit for picking flow¬ers than for the underground. After a few days I was ashamed of these ideas. I realized that she was stubborn, brave and firm in her views. The greater the difficulty, the greater her daring. Suddenly I saw in her innocent and gentle wide-open eyes a small flame that lit up. That was the center of gravity of her daring character.”14

Here, Grossman reflects on that instinct to characterize and judge Tema based solely on her appearance, and expresses shame for doing do when Tema was, in fact, a brave, daring, and stubborn young woman; one who seemed to fear nothing, and established her own boundaries.

In her memoir They Are Still with Me, courier and arms smuggler Havka Folman-Raban adds nuance to this portrait of Tema. She wrote:

“For a short while I lived in the same room with Tema Schneiderman …Under the bed was…a suitcase containing pistols and grenades … Tema and I brought the grenades to the ghetto ... Each of the girls hid a grenade in her most intimate place, her undergarments. From a suburb of the city we took a streetcar in the direction of the ghetto. I recall our odd behavior during the ride. Tema stood at my side and asked: ‘What would happen if a gentleman invited us to sit beside him?’ We broke into laughter; hiding our fear in this way…”15

From this excerpt we learn that Tema had strong leadership qualities, and natural instincts for covert action. Tema understood that to carry out this type of mission successfully, one had to blend in—to look like a happy, carefree young woman out with friends, and not like a frightened Jew on a deadly serious mission.

Noting Havka’s fear, Tema distracted her with a simple, absurd statement. Even Zivia Lubetkin noted this incident, writing that “There was even humor amidst the danger, as in what happened to Tema. She was standing in a crowded train with a hand grenade hidden in her underwear…”16 Zivia Lubetkin portrayed herself in her writings and comported herself publicly—and was noted in the memoirs and testimonies of her friends and comrades—as an extraordinarily serious person, so her noting of Tema’s humor further emphasizes Tema’s emotional intelligence and demeanor.

Though this is a small amount of evidence to build an argument on, put together, and in the context of the source pool, these recollections demonstrate that Tema was an extraordinarily brave, canny, charismatic, and emotionally intelligent young woman; not just a beautiful woman, and not simply someone’s girlfriend.

Tossia Altman left us with more writings than did Tema, most likely due to her leadership role in Hashomer Hatzair, and later, in the Jewish Fighting Organization. Tossia was born in 1919 in Lipno, Poland.17 She spoke Hebrew and Polish, and was active in the Hashomer Hatzair youth movement.18 Within this movement, she quickly earned a reputation as a talented leader.19 After the German occupation of Poland, she traveled to cities across the General Government, encouraging the young people she encountered to engage in clandestine educational and social activities.20

When movement representatives met in Vilna on December 31, 1941, Abba Kovner delivered in Yiddish a famous speech calling for armed resistance (“Let us not go like sheep to the slaughter...”).21 He then turned to Tossia, freshly arrived from Warsaw, and had her deliver the same speech in Hebrew.22 This speaks to the respect she was accorded within the movement, and the respect given to the female couriers.23

On July 28 1942, the date of the establishment of the Jewish Fighting Organization, or ZOB, in Warsaw, its command selected four representatives to operate on the Aryan side of the city, and acquire weapons: Frumka Plotnicka, Leah Perlstein, Ariyeh Wilner, and Tossia, signaling once more the high esteem in which her colleagues held her.24 Tossia was also charged to liaise with the Armja Krajowa, and the Armja Ludowa (the main Polish underground, and the Communist Polish underground, respectively).25

On April 18, 1943, the day of the breakout of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, Tossia reported on the action to Yitzhak Zuckerman—who was stationed on the Aryan side of the city—via a phone in one of the ghetto’s factories.26 She continued to relay updates to comrades on the outside over the course of the Uprising.27

On May 8, 1943, the Germans discovered the ZOB command bunker at Mila 18, and piped in poison gas to force out those hiding within.28 Tossia was one of six who managed to escape from the bunker alive.29 Zivia Lubetkin, Marek Edelman, and Haim Frymer came upon these injured survivors later that night outside the ruins of Mila 18.30 They were barely conscious, and covered in blood; Tossia bore terrible wounds to the leg and the head.31

On the morning of May 9, Tossia escaped the burning ghetto through the sewers with a group lead by Zivia Lubetkin and Simha Rotem.32 After a brief stint hiding in the Lumianki Forest (about 7 km from Warsaw), she was housed with several comrades in the attic of a celluloid factory.33 On May 24, 1943, Tossia’s attic hideout caught fire and the fire spread rapidly. According to varying accounts, the fire either started when a young man struck a match, or when Tossia heated up some ointment for her wounds. Likewise, some of her contemporaries claim that Tossia died in the fire; while others say that she escaped the burning factory, was handed over to the Gestapo, and then was either tortured to death, or taken to a hospital where the Gestapo interrogated her, and then left her to die.34

Havka Folman-Raban worked closely with Tossia on a number of occasions, and wrote in her memoir:

“She was a few years older than I and more experienced. When I was with her, which was not often, I felt that I was in the presence of a worthy person. Although she radiated authority, our friendship was genuine. When I returned from my missions she welcomed me in such a way that I was aware of how worried she had been about me.”35

Vladka Meed also discusses Tossia in her memoir, On Both Sides of the Wall:

“Yurek (Aryeh Wilner) had succeeded in buying a considerable quantity of revolvers and hand grenades … But as soon as he had brought the valise with the ‘merchandise’ to his apartment, the Gestapo swooped down on him, found the weapons, and arrested Yurek … When Yurek’s close friend, Tossia Altman of Hashomer Hatzair told us the news, we were stunned ... But Tossia was not to be deterred; she had come seeking advice from Stephan Machai; perhaps he knew someone who could be bribed.”36

These recollections, combined with Tossia’s leadership positions in the various iterations of the Polish Jewish underground, paint the picture of a stubborn, thoughtful, immensely courageous woman. However, what complicates this picture is Yitzhak Zuckerman’s portrayal of Tossia Altman in his memoir, A Surplus of Memory.

Zuckerman includes several less-than-flattering comments about Tossia, though always taking care to point out that these things weren’t his opinions, but that he simply felt obligated to include them. These include such tidbits as: writing that the Hashomer members didn’t respect Tossia, and perhaps found her irritating; and implicitly criticizing her for entering the ghetto the night before the Uprising when she was supposed to be stationed on the Aryan side with him.37

Now, obviously that Zuckerman wrote these things does not make them fact, and Zuckerman’s memoirs and testimonies have been critiqued in the past for distortion and incorrect recollections of events. However, they do add nuance to our ability to assess Tossia’s personality, or behavior around others.

In her last letter, written to the Zionist leadership in Palestine regarding the free Jewish world’s seeming abandonment of the Jews of Europe, Tossia wrote:

“I think you’ll agree with me that one shouldn’t draw strength from a poisoned well. I am trying to control myself not to vent the bitterness that has accumulated against you and your friends for having forgotten us so utterly. I blame you that you didn’t help me with a few words at least. But today I don’t want to settle my accounts with you. It was the recognition and certainty that we will never see each other again that impelled me to write . . . . Israel is vanishing before my eyes and I wring my hands and I cannot help him. Have you ever tried to smash a wall with your head?”38

The majority of this letter constitutes a fairly eloquent, poetic, even, reprimand, but then Tossia ends it with a line tonally out of place with the rest of the letter, to the extent that it sparks amusement. If Tossia was willing to write this informally, casually, and in so darkly humorous a manner, it’s reasonable to deduce between that, and Zuckerman’s statements, that her behavior around other movement members may have been decidedly quirky, or out of keeping what they considered to be an appropriate demeanor.

What emerges from my analysis of these sources in regard to reconstructing the personalities of these two women is that we will never be able to get inside their heads as fully as we could someone who left writings and testimonies. We will always be at a distance. But by reading carefully and keeping our eyes open for the sparks of personality which so easily slip through the cracks of hagiographic postwar writings, we can create a blurred, imperfect impression of Tema as a frequently under-estimated brave, funny, charismatic, and immensely socially intelligent woman; and of Tossia as a courageous, enthusiastic operative who commanded respect from her peers on the basis of her leadership and actions, but who also didn’t quite fit in in terms of social skills and demeanor.

These conclusions, and the framework I used to arrive at them will, I hope, help us do our part to fill in the gaps in Holocaust memory, and imbue it with women the general public feel they can understand.

Thank you.

Footnotes

1 Lenore J. Weitzman, “Women of Courage: The Kashariyot (Couriers) in the Jewish Resistance During the Holocaust,” in Lessons and Legacies VI: New Currents in Holocaust Research, ed. Jeffrey M. Diefendorf (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2004), 114.

2 Weitzman, “Women of Courage,” 115.

3 Bronia Klibanski, “Tema Sznajderman,” Jewish Women’s Archive, December 31, 1999, https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/sznajderman-tema.

4 Klibanski, “Tema Sznajderman.”

5 Klibanski, “Tema Sznajderman.”

6 Klibanski, “Tema Sznajderman.”

7 Klibanski, “Tema Sznajderman.”

8 Klibanski, “Tema Sznajderman.”

9 Klibanski, “Tema Sznajderman;” Yitzhak “Antek” Zuckerman, A Surplus of Memory: Chronicle of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), 254.

10 Klibanski, “Tema Sznajderman.”

11 Klibanski, “Tema Sznajderman.”

12 Klibanski, “Tema Sznajderman.”

13 Klibanski, “Tema Sznajderman.”

14 Chaika Grossman, The Underground Army: Fighters of the Bialystok Ghetto (New York: Holocaust Library, 1987), 17.

15 Havka Folman-Raban, They are Still With Me (M.P. Western Galilee: Ghetto Fighters' Museum, 2001), 82.

16 Zivia Lubetkin, In the Days of Destruction and Revolt (Tel Aviv: Hakibbutz Hameuchad Publishing House, 1981), 80.

17 Ziva Shalev, “Tosia Altman,” Jewish Women’s Archive, December 31, 1999, https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/altman-tosia.

18 Shalev, “Tosia Altman;” Yitzhak Zuckerman, A Surplus of Memory: Chronicle of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, trans. Barbara Harshav (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), 87.

19 Shalev, “Tosia Altman.”

20 Shalev, “Tosia Altman.”

21 Weitzman, “Women of Courage,” 143.

22 Weitzman, “Women of Courage,” 143.

23 Weitzman, “Women of Courage,” 143.

24 Daniel Blatman, For Our Freedom and Yours: The Jewish Labour Bund in Poland, 1939-1949 (Portland, OR: Valentine Mitchell, 2003), 103.

25 Shalev, “Tosia Altman.”

26 Shalev, “Tosia Altman;” Avinoam Patt, The Jewish Heroes of Warsaw: The Afterlife of the Revolt (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2021), 56.

27 Shalev, “Tosia Altman.”

28 Shalev, “Tosia Altman.”

29 Shalev, “Tosia Altman.”

30 Lubetkin, In the Days of Destruction and Revolt, 229-231; Bella Gutterman, Fighting for Her People: Zivia Lubetkin, 1914-1978 (Jerusalem: Yad VaShem, International Institute for Holocaust Research, 2014), 237-238.

31 Lubetkin, Days of Destruction and Revolt, 229-233; Gutterman, Fighting for Her People, 237-238; Marek Edelman, The Ghetto Fights: Warsaw 1943-1945 (London: Bookmarks Publications, 2014), 67; Vladka Meed, On Both Sides of the Wall, trans. Dr. Stephen Meed (Washington DC: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, 1999), 154.

32 Shalev, “Tosia Altman;” Gutterman, Fighting for her People, 260.

33 Shalev, “Tosia Altman.”

34 Gutterman, Fighting for Her People, 263-264; Lubetkin, Days of Destruction and Revolt, 287; Zuckerman, A Surplus of Memory, 395-396; Tuvia Borzykowski, Between Tumbling Walls (Tel Aviv: Beit Lohamei HaGetaot, 1976), 123-124; Meed, On Both Sides of the Wall, 159-160; Patt, Jewish Heroes of Warsaw, 126.

35 Folman-Raban, They are Still With Me, 83.

36 Meed, On Both Sides of the Wall, 154.

37 Patt, Jewish Heroes of Warsaw, 52.

38 Patt, Jewish Heroes of Warsaw, 82-83.

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

@ichabodjane

Why can't they write skilled midwives? Insert patriarchy and historically downplayed importance of midwifery here. 🙄

Years ago I read up on the representation of female healers in mythology/fairy tales/medieval tales and basically this changed at the same time where female healers, midwives included, were actively being relegated to second rank, or even outright forbidden from practice by the rising make class of 'physicians'. The real life events were closely linked to the depiction of female healers in stories and was precipitated by the medieval christianisation movement. Healing as an art did not only consist of physical practices but also the spiritual. Where in the past, healers would not only use herbal/practical remedies but also rely on amulets and spells, from a certain time (I'm not quite sure anymore but I believe this happened around the 10th-13th century) this was increasingly seen as using the devil's powers. Because women were not officially permitted to hold a function in christian religion, the right to saying healing spells (aka prayers) was limited to men of the clergy and women who were doing it were starting to be seen as, you guessed it, witches.

This started a slow and long proces of ousting women in medical roles, like midwives, from their often officially held positions in towns and communities; to be replaced by men.

So yes. You are correct. This is patriarchy and the historical downplaying of midwives and it makes me ANGRY.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blérancourt drama: Thérèse Gellé's mother attacks National Guard and tells them to fuck off

I was going through Monar and I found about an incident from 1790 Blérancourt, involving SJ's arch-enemy (from the village), Gellé. Or, more precisely, his wife, Thérèse's mother. It's a small thing but it's sending me so much.

Background: Gell�� doesn't want to serve in the National Guard because he is a royalist. So a delegation is sent (possibly/probably) by Saint-Just himself to check why he is neglecting his duties.

Monar writes (Google translated; emphasis mine):

At nine o'clock, under the command of Captain Clay-Lefebvre, four men of the National Guard, a cook, a carpenter, a white tanner, and a day laborer, presented themselves with the letter before the Gellé's house. If the social status of the delegation, which was unquestionably quite low in the eyes of a wealthy Notabein, was intended as a provocation, it achieved its goal: Mrs. Gellé stepped out and immediately indulged in such indelicate words against the guardsmen that the expressions in question were only indicated by the first letter in each case in the protocol that was later drawn up.

She [...] continued to shout at the National Guardsmen:

que son mari la [la garde] monterait pas, n'étant pas fait pour se trouver avec des bandes de canailles, de coquins et de geux comme eux et ceux qui composaient leur f... milice.

[her husband won't stand guard, as he was not the kind to find himself among groups of scoundrels, rascals and bandits like them and those who make up their f...(probably "foutu" so "fucking") militia] - translation by @robespapier

Having already thrown ashes at the speechless, she finally picked up a stick to strike a blow at the captain, who flinched and drew his rapier.

It ended up with Gellé and his brother appearing and the delegation went back. But! A detailed report was made about the incident by SJ's best friend Victor Thuiller. Which was later used as a proof of Gellé's anti-revolutionary behaviour.

This hilarious (?) anecdote is just one of the many (many many) instances of Blérancourt bickering and drama early in the Revolution. There were a lot of tensions, often at the Gellé vs SJ front (well, royalist vs revolutionary front), and it's so, so interesting to me. I need to make a list of all the incidents and research them in more depth.

But seriously? SJ had a LOT of practice with political bickering before he got to the Convention. But also, since this is a village of 2.5 600 people, it also reads like a total soap opera.

#to quote#@robespapier#'she was consumed by anti-revolutionary rage'#and remember this is the woman who raised 'a little mouse with no boldness' as SJ described Therese#idk the whole mess is sending me#i apologize in advance for all the blerancourt soap opera posting#i need to grab my popcorn and read about the drama#louis-antoine on louis-antoine violence#fun#frev#gender history#therese gelle#saint-just#not really but they are the closest tags i have

27 notes

·

View notes