#saint-just

Text

without the Jacobinical "excess", there would be no "normal" pluralist democracy.

Žižek frev commentary compilation

title from For They Know Not What They Do: Enjoyment as a Political Factor (1991).

We must start at the beginning, in The Sublime Object of Ideology (1989). Here, apart from closely examining Walter Benjamin's late (in every sense of the word) writing, Theses on the Philosophy of History, Žižek also quoted Robespierre and Saint-Just directly. (all pink emphases mine.)

Rosa Luxemburg ... her argument against Eduard Bernstein, against his revisionist fear of seizing power 'too soon', 'prematurely', before the so-called 'objective conditions' had ripened ... Rosa Luxemburg's answer is that the first seizures of power are necessarily 'premature'... The opposition to the 'premature' seizure of power is thus revealed as opposition to the seizure of power as such, in general : to repeat Robespierre's famous phrase, the revisionists want a 'revolution without revolution'.

"From Symptom to Sinthome", in Chapter 1, "The Symptom", in The Sublime Object of Ideology, Verso, London and New York, 1989

Žižek's perspective still feels refreshing, not simply because he presented the French Revolution in positive terms, but because he avoided the cliché of a Leninist or Stalinist reading of the French Revolution. Instead, Žižek had a Jacobin reading of various 20th-century revolutions.

The transubstantiated body of the classical Master is an effect of the performative mechanism already described by La Boétie, Pascal and Marx: we, the subjects, think that we treat the king as a king because he is in himself a king, but in reality a king is a king because we treat him like one.

...

The formula of the totalitarian misrecognition of the performative dimension would then be as follows: the Party thinks that it is the Party because it represents the People's real interests, because it is rooted in the People, expressing their will; but in reality the People are the People because ― or more precisely, in so far as ― they are embodied in the Party.

...Because the People cannot immediately govern themselves, the place of Power must always remain an empty place; any person occupying it can do so only temporarily, as a kind of surrogate, a substitute for the real-impossible sovereign ― 'nobody can rule innocently', as Saint-Just puts it. And in totalitarianism, the Party becomes again the very subject who, being the immediate embodiment of the People, can rule innocently.

"You Only Die Twice", in Chapter 2, "Lack in the Other", in The Sublime Object of Ideology, Verso, London and New York, 1989

In his second book, For They Know Not What They Do: Enjoyment as a Political Factor (1991), Žižek expanded on how the Jacobins were not a Party (keep in mind, Žižek uses the word "Jacobin" as more-or-less synonymous with "Robespierrist") :

Within the post-revolutionary "totalitarian" order, we have witnessed a re-emergence of the sublime political body in the shape of Leader and/or Party. The tragic greatness of the Jacobins consists precisely in the fact that they refused to accomplish this step: they preferred to lose their head physically, rather than to take upon themselves the passage to personal dictatorship .

...

The Jacobins lacked the absolute certainty that they were nothing but an instrument fulfilling the Will of the big Other (God, Virtue, Reason, Cause). They were always tormented by the possibility that behind the façade of the executor of the Terror on behalf of revolutionary Virtue, some "pathological" private interest might be hiding.

...

As such they were, so to speak, ontologically guilty, and it was only a matter of time before the guillotine would cut off their heads. It is precisely for this reason, however, that their Terror was democratic, not yet "totalitarian", in contrast to post-democratic totalitarianism, in which the revolutionaries fully assume the role of an instrument of the big Other, whereby their very body again redoubles itself and assumes sublime quality.

"Much Ado about a Thing", in For They Know Not What They Do, Verso, London and New York, 1991

The pessimism here is twofold. The Jacobin project must take place, and the Jacobins themselves must meet unfair and cruel ends for all the good they have done. This pessimism permeates every book that Žižek has written, but all this is in no way a denial of the revolutionary becoming.

For example, the quote before the cut, from Chapter 2 of the Sublime Object, might have made you wonder, "did Žižek say that the People in real-socialist countries are similar to the kings of the ancien régime? "

In which case, let's see what Žižek thinks of even the royals whose function was (or is) that of figureheads:

A distinction between king as a symbolic function and its empirical bearer misses a paradox that we could designate by the term "chiasmic exchange of properties" introduced by Andrzej Warminski.

...

As soon as a certain person functions as "king", his everyday, ordinary properties undergo a kind of "transubstantiation" and become an object of fascination.

...

The more we represent the king as an ordinary man, caught in the same passions, victim of the same pettinesses as we ― that is, the more we accentuate his "pathological" features (in the Kantian meaning of the term) ― the more he remains "king". Because of this paradoxical exchange of properties, we cannot deprive the king of his charisma simply by treating him as our equal. At the very moment of his greatest abasement, he arouses absolute compassion and fascination ― witness the trial of "citizen Louis Capet".

"Much Ado about a Thing", in For They Know Not What They Do, Verso, London and New York, 1991

So much for the tired and depressed and often missing Louis Capet. And therefore:

The paradox of the Hegelian monarch is thus that, in a sense, he is the point of madness of the social fabric; his social position is determined immediately by his lineage, by his biology; he is the only one among individuals who already by his "nature" is what he (socially) is ― all others must "invent" themselves, elaborate the content of their being by their activity. As always, Saint-Just was right when, in his accusation against the king, he demanded his execution not because of any specific deeds but simply because he was king. From a radically republican point of view, the supreme crime consists in the very fact of being the king, not in what one does as a king.

"The Wanton Identity", in For They Know Not What They Do, Verso, London and New York, 1991

This logic extends to the crime of being a hero, and not what one might do that abuses the status as a hero. Danton's crimes of accepting of bribes, association with the embezzling Fabre d'Églantine, encouraging Desmoulins to do journalism of questionable quality, etc, were condemning enough, but the crime of accepting the lauding of the Parisian poor was the last straw.

The director Wajda was therefore unintentionally justifying Danton's death by starting the film with the poor and unfed running to stop the carriage that Gérard Depardieu as Danton was sitting in, and vying to shake his hand like he was a 20th century celebrity. Danton seemed unaware that the people who surrounded him had neither time nor economic stability to celebrate in.

Robespierre's argument against Danton does not consist in any positive evidence of his guilt. It is enough to recall the obvious, purely formal fact that Danton is a revolutionary hero and as such elevated above the mass of ordinary citizens ― that is, claiming a special status for himself. In the Jacobinical universe, the hero of the Revolution is separated from its traitor by a thin, often indefinable line. The very form of hero can turn into a traitor one who, as to deeds, is a revolutionary hero; this form raises him over ordinary citizens and so exposes him to the danger and lure of tyranny. Robespierre himself was quite aware of this paradox, and his tragic greatness expresses itself in his stoic acceptance of the prospect of being decapitated in the service of the Revolution.

"Much Ado about a Thing", in For They Know Not What They Do, Verso, London and New York, 1991

Despite not commenting directly on what impacts the French Revolution had on sexuality (legalisation of divorce, decriminalisation of sodomy, advent of the capitalist notion of the love-couple, etc), Žižek shows that he would extra-doubt those whose only progressiveness lie in their attitude towards sexuality:

Casanova is Don Giovanni's exact opposite: a merry swindler and impostor, an epicure who irradiates simple pleasure and leaves behind no bitter taste of revenge, and whose libertinage presents no serious threat to the environs. He is a kind of correlate to the eighteenth-century freethinkers from the bourgeois salon: full of irony and wit, calling into question every established view; yet his trespassing of what is socially acceptable never assumes the shape of a firm position which would pose a serious threat to the existing order. His libertinage lacks the fanatic-methodical note, his spirit is that of permissiveness, not of purges; it is "freedom for all", not yet "no freedom for the enemies of freedom". Casanova remains a parasite feeding on the decaying body of his enemy and as such deeply attached to it: no wonder he condemned the "horrors" of the French Revolution, since it swept away the only universe in which he could prosper.

"Hegelian Llanguage", in For They Know Not What They Do, Verso, London and New York, 1991

We might be aware that praising Robespierre was not (and is not) an exclusively leftist position; Joseph de Maistre, known as the other dad of modern conservatism along with Edmund Burke, and literal enemy of the republic on the frontline, was in awe with how Robespierre made close to no tactic error in matters political, economical, and military alike, notably without having much knowledge in the latter.

What we do know about (non-royalist) conservatives, however, is that they tend to praise Bonaparte as a leader worthy of his position. Žižek's labelling of Bonaparte cannot be more different:

The usual critique of patriarchy fatally neglects the fact that there are two fathers. On the one hand there is the oedipal father: the symbolic-dead father, Name-of-the-Father, the father of Law who does not enjoy, who ignores the dimension of enjoyment; on the other hand there is the 'primordial' father, the obscene, superego anal figure that is real-alive, the 'Master of Enjoyment'. At the political level, this opposition coincides with that between the traditional Master and the modern ('totalitarian') Leader. In all emblematic revolutions, from the French to the Russian, the overthrow of the impotent old regime of the symbolic Master (French King, Tsar) ended in the rule of a far more 'repressive' figure of the 'anal' father-Leader (Napoleon, Stalin). The order of succession described by Freud in Totem and Taboo (the murdered primordial Father-Enjoyment returns in the guise of the symbolic authority of the Name) is thus reversed: the deposed symbolic Master returns as the obscene-real Leader. In short, here Freud was the victim of a kind of perspective illusion: 'primordial father' is a later, eminently modern, post-revolutionary phenomenon, the result of the dissolution of traditional symbolic authority.

"From Patriarchy to Cynicism", in The Metastases of Enjoyment, Verso, London and New York, 1994

Žižek's later famous "coffee without caffeine" "cream without fat" "beer without alcohol" pet phrases seemed to have stemmed from Robespierre's "a revolution without a revolution". One would be mistaken to think of Žižek as solely complaining about food products; the "coffee without caffeine" served as metaphor for liberal-conservative attempts at avoiding the their own disintegration: e.g. multiculturalism that focuses on the exotic veneer of the Other without confronting the immanent contradictions in every way of life, and therefore introduces "the Other without Otherness", while decolonisation necessarily involves the abolishing of the western way of life. Liberal multiculturalism therefore constitutes what Saint-Just would call "revolutions done in halves" -- digging one's own grave.

An Act always involves a radical risk, what Derrida, following Kierkegaard, called the madness of a decision: it is a step into the open, with no guarantee about the final outcome – why? Because an Act retroactively changes the very co-ordinates into which it intervenes. This lack of guarantee is what the critics cannot tolerate: they want an Act without risk – not without empirical risks, but without the much more radical 'transcendental risk' that the Act will not only simply fail, but radically misfire. In short, to paraphrase Robespierre, those who oppose the 'absolute Act' effectively oppose the Act as such, they want an Act without the Act.

"Conclusion: The Smell of Love", in Welcome to the Desert of the Real, Verso, London and New York, 2002

Žižek would always admit that any revolution had innocent victims, and even more keenly aware how these victims can be misrepresented and abused yet again by reactionary forces. Significant was the difference between the violence that was visible, had a clear perpetrator, and easy to be the subject of outcry, and the violence that constitutes our daily interactions, our conforming to irrational standards, our objectification and alienation.

When the US media reproached the public in foreign countries for not displaying enough sympathy for the victims of the 9/11 attacks, one was tempted to answer them in the words Robespierre addressed to those who complained about the innocent victims of revolutionary terror: 'Stop shaking the tyrant's bloody robe in my face, or I will believe that you wish to put Rome in chains.'

"Introduction: The Tyrant's Bloody Robe", in Violence, Profile Books Ltd, London, 2008

Apropos Benjamin's Divine Violence, the French Revolution provided good positive examples for what it is.

Divine violence is not the repressed illegal origin of the legal order – the Jacobin revolutionary Terror is not the 'dark origin' of the bourgeois order, in the sense of the heroic-criminal state-founding violence celebrated by Heidegger.

...

This is why, as was clear to Robespierre, without the 'faith' in (a purely axiomatic pre-supposition of ) the eternal idea of freedom which persists through all defeats, a revolution 'is just a noisy crime that destroys another crime'.

...

Or, to paraphrase Kant and Robespierre yet again: love without cruelty is powerless; cruelty without love is blind, a short-lived passion which loses its persistent edge. The underlying paradox is that what makes love angelic, what elevates it over mere unstable and pathetic sentimentality, is its cruelty itself, its link with violence – it is this link which raises it ‘over and beyond the natural limitations of man’ and thus transforms it into an unconditional drive.

"... And, Finally, What It Is!", in Violence, Profile Books Ltd, London, 2008

Hegel, to whom Žižek awards the status of an extra-terrestrial creature, constantly disturbing all other philosophers dead or alive, often thought of by the general public in turn as both incomprehensible and somehow embodying the conservative-essentialist false concept of German essence (which often abhors revolutionary excess), was to Žižek not a counterrevolutionary at all, nor an unconditional singer of the Jacobins' praises, but a pessimistic confirmer of the necessity of the Terror.

Shut up, Barère, the truly radical Anacreon of the guillotine was 3 years younger than Saint-Just.

Let us take Hegel’s critique of the Jacobin Revolutionary Terror, understood as an exercise in the abstract negativity of absolute freedom which, unable to stabilize itself in a concrete social order, has to end in a fury of self-destruction.

...

In other words, the point of Hegel’s analysis of the Revolutionary Terror is not the rather obvious insight into how the revolutionary project involved the unilateral assertion of abstract Universal Reason and was as such doomed to perish in self-destructive fury, being unable to transpose its revolutionary energy into a stable social order; Hegel’s point is rather to highlight the enigma of why, in spite of the fact that Revolutionary Terror was a historical deadlock, we have to pass through it in order to arrive at the modern rational State.

from "In Praise of Understanding", in Chapter 5, "Parataxis: Figures of the Dialectical Process", in Less than Nothing, Verso, London and New York, 2012

In 2012, the same year as he wrote the preface to Sophie Wahnich's La Liberté ou la mort — Essai sur la Terreur et le terrorisme, Žižek also attacked the "1789 without 1793" formula of liberal reactionaries.

It has been said that the French revolution resulted from philosophy, and it is not without reason that philosophy has been called Weltweisheit [world wisdom]; for it is not only truth in and for itself, as the pure essence of things, but also truth in its living form as exhibited in the affairs of the world.

...

one should never forget that Hegel’s critique is immanent, accepting the basic principle of the French Revolution (and its key supplement, the Haitian Revolution). One should be very clear here: Hegel in no way subscribes to the standard liberal critique of the French Revolution which locates the wrong turn in 1792–3, whose ideal is 1789 without 1793, the liberal phase without the Jacobin radicalization―for him 1793–4 is a necessary immanent consequence of 1789; by 1792, there was no possibility of taking a more “moderate” path without undoing the Revolution itself. Only the “abstract” Terror of the French Revolution creates the conditions for post-revolutionary “concrete freedom.”

If one wants to put it in terms of choice, then Hegel here follows a paradoxical axiom which concerns logical temporality: the first choice has to be the wrong choice. Only the wrong choice creates the conditions for the right choice. Therein resides the temporality of a dialectical process: there is a choice, but in two stages. The first choice is between the “good old” organic order and the violent rupture with that order ― and here, one should take the risk of opting for “the worse.” This first choice clears the way for the new beginning and creates the condition for its own overcoming, for only after the radical negativity, the “terror,” of abstract universality has done its work can one choose between this abstract universality and concrete universality. There is no way to obliterate the temporal gap and present the choice as threefold, as the choice between the old organic substantial order, its abstract negation, and a new concrete universality.

from "The Differend", in Chapter 5, "Parataxis: Figures of the Dialectical Process", in Less than Nothing, Verso, London and New York, 2012

Another problem with the ideal of shaking off the old regime, then immediately achieving fully-automated luxury gay space communism is that universality can peek into a liberal democracy in many ways, some more sinister than others.

for Hegel, modern bourgeois society could only have arisen through the mediation of Revolutionary Terror (exemplified by Jacobins); furthermore, Hegel is also aware that, in order to prevent its own death by habituation (immersion in the life of particular interests), every bourgeois society needs to be shattered from time to time by war.

...

In war, universality reasserts its right over and against the concrete-organic appeasement in prosaic social life.

...

This necessity of war should be linked to its opposite: the necessity of a rebellion which shakes the power edifice from its complacency, making it aware of both its dependence on popular support and of its a priori tendency to "alienate" itself from its roots. ... The beauty of the Jacobins is that, in their terror, they brought these two opposed dimensions together: the Terror was simultaneously the terror of the state against individuals and the terror of the people against particular state institutions or functionaries who excessively identified with their institutional positions (the objection to Danton was simply that he wanted to rise above others).

from "Interlude 3: King, Rabble, War … and Sex", in Less than Nothing, Verso, London and New York, 2012

Marat warned of the state spending more on formalities and ceremonies than on meeting the economic needs of the peasants and the urban poor. His advice was not heeded by the National Convention, and his funeral, organised by Jacques-Louis David as a member of the Committee of General Security, was grand and expensive. The Friend of the People was elevated to a status he neither wanted for himself nor posited that anybody deserved. While David was known (and notorious) for taking artistic liberty when it came to his subjects, his subjective view of Marat's "sublime body" was libertied in such a way that betrayed David's own unease between individualism and collectivism:

When the sovereignty of the State shifts from King to People, the problem becomes that of the people’s Body, of how to incarnate the People, and the most radical solution is to treat the Leader as the People incarnated. In between these two extremes, there are many other possibilities―consider the uniqueness of Jacques-Louis David’s The Death of Marat, “the first modernist painting,” according to T. J. Clark. The oddity of the painting’s overall structure is seldom noted: its upper half is almost totally black. (This is not a realistic detail: the room in which Marat actually died had lively wallpaper.) What does this black void stand for? The opaque body of the People, the impossibility of representing the People? It is as if the opaque background of the painting (the People) invades it, occupying its entire upper half.

...

Is this not also the logic of the Jacobin Terror―individuals must be annihilated in order to make the People visible; the People’s Will can be made visible only through the terrorist destruction of the individual’s body? Therein resides the uniqueness of The Death of Marat: it concedes that one cannot blur the individual in order to represent the People directly―all one can do to come as close as possible to an image of the People is to show the individual at the point of his disappearance―his tortured, mutilated dead body against the background of the blur that “is” the People.

...

It is quite impressive that this uneasy and disturbing painting was adored by the revolutionary crowds in Paris―proof that Jacobinism was not yet “totalitarian,” that it did not yet rely on the fantasmatic logic of a Leader who is the People. Under Stalin, such a painting would have been unimaginable, the upper part would have had to have been filled in―with, say, the dream of the dying Marat, depicting the happy life of a free people dancing and celebrating their freedom. The greatness of the Jacobins lay in their attempt to keep the screen empty, to resist filling it in with ideological projections.

from "Presence", in Chapter 10, "Objects, Objects Everywhere", in Less than Nothing, Verso, London and New York, 2012

The "keeping the screen empty" was tragic also in the verbal sense:

Louis Althusser once came up with a typology of revolutionary leaders worthy of Kierkegaard's classification of humans into officers, housemaids, and chimney sweeps: those who quote proverbs, those who do not quote proverbs, those who invent (new) proverbs. The first are scoundrels (Althusser thought of Stalin); the second are great revolutionaries who are doomed to fail (Robespierre); only the third understand the true nature of a revolution and succeed (Lenin, Mao). ... Radical revolutionaries like Robespierre fail because they just enact a break with the past without succeeding in their effort to enforce a new set of customs (recall the utter failure of Robespierre's idea to replace religion with the new cult of a Supreme Being).

"Venezuela and the Need for New Clichés", in A Left that Dares to Speak Its Name, Polity Press, Cambridge, Cambridgeshire, 2020

In a continuation of the refute of "1789 without 1793", Žižek pointed to the proper sequel of the French Revolution as a sequel of 1793, albeit with a twist.

The continuity between the French Revolution and the Commune is at another level. The reception among the enlightened public of the first phase of the French Revolution was enthusiastic, and this enthusiasm turned into horror when the Jacobins took over: 1789 yes, 1793 no. At the level of political dynamic, the Commune was the reappearance of 1793 – but not a precise one. Something happened with the Commune that did not happen in 1793.

"Paris Commune at 150", in Heaven in Disorder, OR Books, New York, 2021.

Despite Robespierre's cult of the Supreme Being being viewed as "utter failure", Robespierre's non-atheist stance was in line with republicanism-as-theology.

Why are so many essays entitled "politico-theological treatise"? The answer is that a theory becomes theology when it is part of a full subjective political engagement. As Kierkegaard pointed out, I do not acquire faith in Christ after comparing different religions and deciding the best reasons speak for Christianity ― there are reasons to choose Christianity but these reasons only appear after I've already chosen it, i.e., to see the reasons for belief one already has to believe. And the same holds for Marxism: it is not that, after objectively analysing history, I became a Marxist ― my decision to be a Marxist (the experience of a proletarian position) makes me see the reasons for it, i.e., Marxism is the paradox of an objective "true" knowledge accessible only through a subjective partial position. This is why Robespierre was right when he distrusted materialism as the philosophy of decadent-hedonist and corrupted nobility, and tried to impose a new religion of the supreme Being of Reason (the main target of his hatred was Joseph Fouche, a radical atheist and an opportunist plotter). The old reproach to Marxism that its commitment to a bright future is a secularization of religious salvation should be proudly assumed.

"Why Politics is Immanently Theological", in Christian Atheism, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2024

Interestingly, Terry Eagleton's attitude of "secularization of religious salvation" in Chapter 3 of Why Marx Was Right (2011) was a much more ambiguous one. Eagleton is also firmly Marxist, but what he is not as firm about is whether this salvation, once achieved, could justify all the sufferings that capitalism, prolonged for two hundred years in its own rotting, has already done to each of us.

In short, the true aim of Robespierre's last two speeches in the Convention was not to further strengthen the Terror but to diminish it, to slowly bring it to an end. As is well-known, he threatened in his last speech that the Convention should be purged of a group of corrupted traitors, and, when repeatedly called to name them, he refused to do it — as we know now, not to spread fear and guilt among the members (each of them afraid that he is on the list), but because the names he targeted were in large majority from his own group of Montagnards. Robespierre's aim was not to spread fear among the enemies but to constrain the need for enemies which led the Jacobins to Terror — in short, he wanted to restrain Terror in order to focus on the ultimate social antagonism in France at that moment: how to save the people's republic from the threat of a military dictator (a threat clearly predicted by him and Saint-Just, and realized with the rise to power of Napoleon).

The complications give us a hint of how Communism will eventually enter the stage: not through a simple parliamentary electoral process but through a state of emergency enforced on us by an apocalyptic threat.

"Why Politics is Immanently Theological", in Christian Atheism, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2024

We can try to answer Eagleton's question, try to imagine what to make of the presence when we arrive at Communism. But what makes Eagleton's question compelling, what makes it an unavoidable question to be pondered upon in the first place, is that divine violence, as supposed to founding violence, is more unskippable than an unskippable ad: some people can block or refuse to experience it some of the time, but never can all people block and refuse to experience it all of the time; yet unlike an ad as the command of the big Other, divine violence has no guarantee from either the Supreme Being or the godess of Liberty, neither Virtue nor Reason nor historical inevitability can confirm that divine violence is truly divine. The risk-taking cannot but be done by the revolutionaries themselves.

The Benjaminian ‘divine violence’ should be thus conceived as divine in the precise sense of the old Latin motto vox populi, vox dei: not in the perverse sense of ‘we are doing it as mere instruments of the People’s Will’, but as the heroic assumption of the solitude of a sovereign decision. It is a decision (to kill, to risk or lose one’s own life) made in absolute solitude, not covered by the big Other. If it is extra-moral, it is not ‘immoral’, it does not give the agent the licence to kill mindlessly with some kind of angelic innocence. The motto of divine violence is fiat iustitia, pereat mundus: it is justice, the point of non-distinction between justice and vengeance, in which the ‘people’ (the anonymous part of no-part) imposes its terror and makes other parts pay the price – the Judgement Day for the long history of oppression, exploitation, suffering.

"Introduction", in Maximilien Robespierre, Virtue and Terror, tr. John Howe, Verso, London and New York, 2007

Happy Birthday, Maximilien.

I would like to thank all my mutuals. I am really enjoying my research and translations more because of your emotional labour (of putting up with my monomania), and this is why Die Partei hat immer recht.

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

okay guys here’s the real footage of Saint-just eating soup with fork

ps. I have no idea what this is.

#saint-just#frev#louis antoine de saint just#frev shitposting#frev memes#what the fuck#why did i draw this

162 notes

·

View notes

Text

Frev Friendships — Saint-Just and Robespierre

You who supports the tottering fatherland against the torrent of despotism and intrigue, you whom I only know, like God, through his miracles; I speak to you, monsieur, to ask you to unite with me in order to save my sad fatherland. The city of Gouci has relocated (this rumour goes around here) the free markets from the town of Blérancourt. Why do the cities devour the privileges of the countryside? Will there remain no more of them to the latter than size and taxes? Support, please, with all your talent, an address that I make for the same letter, in which I request the reunion of my heritage with the national areas of the canton, so that one lets to my country a privilege without which it has to die of hunger. I do not know you, but you are a great man. You are not only the deputy of a province, you are one of humanity and of the Republic. Please, make it that my request be not despised. I have the honour to be, monsieur, your most humble, most obedient servant.

Saint-Just, constituent of the department of Aisne.

To Monsieur de Robespierre in the National Assembly in Paris.

Blérancourt, near Noyon, August 19, 1790.

Saint-Just’s first letter ever written to Robespierre, dated August 19 1790

Citizens, you are aware that, to dispel the errors with which Roland has covered the entire Republic, the Society has decided that it will have Robespierre's speech printed and distributed. We viewed it as an eternal lesson for the French people, as a sure way of unmasking the Brissotin faction and of opening the eyes of the French to the virtues too long unknown of the minority that sits with the Mountain. I remind you that a subscription office is open at the secretariat. It is enough for me to point it out to you to excite your patriotic zeal, and, by imitating the patriots who each deposited fifty écus to have Robespierre's excellent speech printed, you will have done well for the fatherland.

Saint-Just at the Jacobins, January 1 1793

Patriots with more or less talent […] Jacquier, Saint-Just’s brother-in-law.

Robespierre in a private list, written sometime during his time on the Committee of Public Safety

Saint-Just doesn’t have time to write to you. He gives you his compliments.

Lebas in a letter to Robespierre October 25 1793

Trust no longer has a price when we share it with corrupt men, then we do our duty out of love for our fatherland alone, and this feeling is purer. I embrace you, my friend.

Saint-Just.

To Robespierre the older.

Saint-Just in a post-scriptum note added to a letter written by Lebas to Robespierre, November 5 1793. Saint-Just uses tutoiement with Robespierre here, while Lebas used vouvoiement.

We have made too many laws and too few examples: you punish but the salient crimes, the hypocritical crimes go unpunished. Punish a slight abuse in each part, it is the way to frighten the wicked, and to make them see that the government has its eye on everything. No sooner do we turn our backs than the aristocracy rises in the tone of the day, and commits evils under the colors of liberty.

Engage the committee to give much pomp to the punishment of all faults in government. Before a month has passed you will have illuminated this maze in which counter-revolution and revolution march haphazardly. Call, my friend, the attention of the Jacobin Club to the strong maxims of the public good; let it concern itself with the great means of governing a free state. I invite you to take measures to find out if all the manufactures and factories of France are in activity, and to favor them, because our troops would within a year find themselves without clothes; manufacturers are not patriots, they do not want to work, they must be forced to do so, and not let down any useful establishment. We will do our best here. I embrace you and our mutual friends.

Saint-Just

To Robespierre the older.

Saint-Just in a letter to Robespierre, December 14 1793

Paris, 9 nivôse, year 2 of the Republic.

Friends.

I feared, in the midst of our successes, and on the eve of a decisive victory, the disastrous consequences of a misunderstanding or of a ridiculous intrigue. Your principles and your virtues reassured me. I have supported them as much as I could. The letter that the Committee of Public Safety sent you at the same time as mine will tell you the rest. I embrace you with all my soul.

Robespierre.

Robespierre in a letter to Saint-Just and Lebas, December 29 1793

Why should I not say that this (the dantonist purge) was a meditated assassination, prepared for a long time, when two days after this session where the crime was taking place, the representative Vadier told me that Saint-Just, through his stubbornness, had almost caused the downfall of the members of the two committees, because he had wanted that the accused to be present when he read the report at the National Convention; and such was his obstinacy that, seeing our formal opposition, he threw his hat into the fire in rage, and left us there. Robespierre was also of this opinion; he believed that by having these deputies arrested beforehand, this approach would sooner or later be reprehensible; but, as fear was an irresistible argument with him, I used this weapon to fight him: You can take the chance of being guillotined, if that is what you want; For my part, I want to avoid this danger by having them arrested immediately, because we must not have any illusions about the course we must take; everything is reduced to these bits: If we do not have them guillotined, we will be that ourselves.

À Maximilien Robespierre aux enfers (1794) by Taschereau de Fargues and Paul-Auguste-Jacques. Robespierre and Saint-Just had also worked out the dantonists’ indictment together.

…As far from the insensibility of your Saint-Just as from his base jealousies, [Camille] recoiled in front if the idea of accusing a college comrade, a companion in arms. […] Robespierre, can you really complete the fatal projects which the vile souls that surround you no doubt have inspired you to? […] Had I been Saint-Just’s wife I would tell him this: the sake of Camille is yours, it’s the sake of all the friends of Robespierre!

Lucile Desmoulins in an unsent letter to Robespierre, written somewhere between March 31 and April 4 1794. Lucile seems to have believed it was Saint-Just’s ”bad influence” in particular that got Robespierre to abandon Camille.

In the beginning of floréal (somewhere between April 20 and 30) during an evening session (at the Committee of Public Safety), a brusque fight erupted between Saint-Just and Carnot, on the subject of the administration of portable weapons, of which it wasn’t Carnot, but Prieur de la Côte-d’Or, who was in charge. Saint-Just put big interest in the brother-in-law of Sijas, Luxembourg workshop accounting officer, that one thought had been oppressed and threatened with arbitrary arrest, because he had experienced some difficulties for the purpose of his service with the weapon administration. In this quarrel caused unexpectedly by Saint-Just, one saw clearly his goal, which was to attack the members of the committee who occupied themselves with arms, and to lose their cooperateurs. He also tried to include our collegue Prieur in the inculpation, by accusing him of wanting to lose and imprison this agent. But Prieur denied these malicious claims so well, that Saint-Just didn’t dare to insist on it more. Instead, he turned again towards Carnot, whom he attacked with cruelty; several members of the Committee of General Security assisted. Niou was present for this scandalous scene: dismayed, he retired and feared to accept a pouder mission, a mission that could become, he said, a subject of accusation, since the patriots were busy destroying themselves in this way. We undoubtedly complained about this indecent attack, but was it necessary, at a time when there was not a grain of powder manufactured in Paris, to proclaim a division within the Committee of Public Safety, rather than to make known this fatal secret? In the midst of the most vague indictments and the most atrocious expressions uttered by Saint-Just, Carnot was obliged to repel them by treating him and his friends as aspiring to dictatorship and successively attacking all patriots to remain alone and gain supreme power with his supporters. It was then that Saint-Just showed an excessive fury; he cried out that the Republic was lost if the men in charge of defending it were treated like dictators; that yesterday he saw the project to attack him but that he defended himself. ”It’s you,” he added, ”who is allied with the enemies of the patriots. And understand that I only need a few lines to write for an act of accusation and have you guillotined in two days.”

”I invite you, said Carnot with the firmness that only appartient to virtue: I provoke all your severity against me, I do not fear you, you are ridiculous dictators.” The other members of the Committee insisted in vain several times to extinguish this ferment of disorder in the committee, to remind Saint-Just of the fairer ideas of his colleague and of more decency in the committee; they wanted to call people back to public affairs, but everything was useless: Saint-Just went out as if enraged, flying into a rage and threatening his colleagues. Saint-Just probably had nothing more urgent than to go and warn Robespierre the next day of the scene that had just happened, because we saw them return together the next day to the committee, around one o'clock: barely had they entered when Saint-Just, taking Robespierre by the hand, addressed Carnot saying: ”Well, here you have my friends, here are the ones you attacked yesterday!” Robespierre tried to speak of the respective wrongs with a very hypocritical tone: Saint-Just wanted to speak again and excite his colleagues to take his side. The coldness which reigned in this session, disheartened them, and they left the committee very early and in a good mood.

Réponse des membres des deux anciens Comités de salut public et de sûreté générale (Barère, Collot, Billaud, Vadier), aux imputations renouvellées contre eux, par Laurent Lecointre et declarées calomnieuses par décret du 13 fructidor dernier; à la Convention Nationale (1795), page 103-105

My friends, the committee has taken all the measures within its control at this time to support your zeal. It has asked me to write to you to explain the reasons for some of its provisions. It believed that the main cause of the last failure was the shortage of skilled generals, it will send you all the patriotic and educated soldiers that can be found. It thought it necessary at this time to re-use Stetenhofen, whom it is sending to you, because he has military merit, and because the objections made against him seem at least to be balanced by proofs of loyalty. He also relies on your wisdom and your energy. Salut et amitié.

Paris, 15 floréal, year 2 of the Republic.

Robespierre.

Robespierre to Saint-Just and Lebas, May 4 1793

Dear collegue,

Liberty is exposed to new dangers; the factions arise with a character more alarming than ever. The lines to get butter are more numerous and more turbulent than ever when they have the least pretexts, an insurrection in the prisons which was to break out yesterday and the intrigues which manifested themselves in the time of Hébert are combined with assassination attemps on several occasions against members of the Committee of Public Safety; the remnants of the factions, or rather the factions still alive, are redoubled in audacity and perfidy. There is fear of an aristocratic uprising, fatal to liberty. The greatest peril that threatens it is in Paris. The Committee needs to bring together the lights and energy of all its members. Calculate whether the army of the North, which you have powerfully contributed to putting on the path to victory, can do without your presence for a few days. We will replace you, until you return, with a patriotic representative.

The members composing the Committee of Public Safety.

Robespierre, Prieur, Carnot, Billaud-Varennes, Barère.

Letter to Saint-Just from the CPS, May 25 1794, written by Robespierre. It was penned down just two days after the alleged attempt on Robespierre’s life by Cécile Renault.

Robespierre returned to the Committee a few days later to denounce new conspiracies in the Convention, saying that, within a short time, these conspirators who had lined up and frequently dined together would succeed in destroying public liberty, if their maneuvers were allowed to continue unpunished. The committee refused to take any further measures, citing the necessity of not weakening and attacking the Convention, which was the target of all the enemies of the Republic. Robespierre did not lose sight of his project: he only saw conspiracies and plots: he asked that Saint-Just returned from the Army of the North and that one write to him so that he may come and strengthen the committee. Having arrived, Saint-Just asked Robespierre one day the purpose of his return in the presence of the other members of the Committee; Robespierre told him that he was to make a report on the new factions which threatened to destroy the National Convention; Robespierre was the only speaker during this session. He was met by the deepest silence from the Committee, and he leaves with horrible anger. Soon after, Saint-Just returned to the Army of the North, since called Sambre-et-Mouse. Some time passes; Robespierre calls for Saint-Just to return in vain: finally, he returns, no doubt after his instigations; he returned at the moment when he was most needed by the army and when he was least expected: he returned the day after the battle of Fleurus. From that moment, it was no longer possible to get him to leave, although Gillet, representative of the people to the army, continued to ask for him.

Réponse de Barère, Billaud-Varennes, Collot d’Herbois et Vadier aux imputations de Laurent Lecointre (1795)

On 10 messidor (June 28) I was at the Committee of Public Safety. There, I witnessed those who one accuses today (Billaud-Varenne, Barère, Collot-d'Herbois, Vadier, Vouland, Amar and David) treat Robespierre like a dictator. Robespierre flew into an incredible fury. The other members of the Committee looked on with contempt. Saint-Just went out with him.

Levasseur at the Convention, August 30 1794. If this scene actually took place, it must have done so one day later, 11 messidor (June 29), considering Saint-Just was still away on a mission on the tenth.

Isn’t it around the same time (a few days before thermidor) that Saint-Just and Lebas would dine at your father’s house with Robespierre?

Lebas often dined there, having married one of my sisters. Saint-Just rarely there, but he frequently went to Robespierre’s and climbed the stairs to his office without speaking to anyone.

During the dinner which I’m talking about, did you hear Saint-Just propose to Robespierre to reconcile with some members of the Convention and Committees who appeared to be opposed to him?

No. I only know that they appeared to be very devided.

Do you have any ideas what these divisions were about?

I only learned about it through the discussions which took place on this subject at the Jacobins and through the altercation which was said to have taken place at the Committee of Public Safety between Robespierre older and Carnot.

Robespierre’s host’s son Jacques-Maurice Duplay in an interrogation held January 1 1795

Saint-Just then fell back on his report, and said that he would join the committee the next day (9 thermidor) and that if it did not approve it, he would not read it. Collot continued to unmask Saint-Just; but as he focused more on depicting the dangers praying on the fatherland than on attacking the perfesy of Saint-Just and his accomplices, he gradually reassured himself of his confusion; he listened with composure, returning to his honeyed and hypocritical tone. Some time later, he told Collot d'Herbois that he could be reproached for having made some remarks against Robespierre in a café, and establishing this assertion as a positive fact, he admitted that he had made it the basis of an indictment against Collot, in the speech he had prepared.

Réponse des membres des deux anciens Comités de salut public et de sûrété générale… (1795) page 107.

I attest that Robespierre declared himself a firm supporter of the Convention and never spoke but gently in the Committee so as not to undermine any of its members. […] Billaud-Varenne said to Robespierre, “We are your friends, we have always walked together.” This dishonesty made my heart shudder. The next day, he called him Peisistratos and had written his act of accusation. […] If you reflect carefully on what happened during your last session, you will find the application of everything I said: a man alienated from the Committee due to the bitterest treatments, when this Committee was, in fact, no longer made up of more than the two or three members present, justified himself before you; he did not explain himself clearly enough, to tell the truth, but his alienation and the bitterness in his soul can excuse him somewhat: he does not know why he is being persecuted, he knows nothing except his misfortune. He has been called a tyrant of opinion: here I must explain myself and shine light on a sophism that tends to proscribe merit. And what exclusive right do you have to opinion, you who find that it is a crime to touch souls? Do you find it wrong that a man should be tenderhearted? Are you thus from the court of Philip, you who make war on eloquence? A tyrant of opinion? Who is stopping you from competing for the esteem of the fatherland, you who find it so wrong that someone should captivate it? There is no despot in the world, save Richelieu, who would be insulted by the fame of a writer. Is it a more disinterested triumph? Cato is said to have chased from Rome the bad citizen who had called eloquence at the tribune of harangues, the tyrant of opinion. No one has the right to claim that; it gives itself to reason and its empire is not the in the power of governments. […] The member who spoke for a long time yesterday at this tribune did not seem to have distinguished clearly enough who he was accusing. He had no complaints and has not complained either about the Committees; because the Committees still seem to me to be dignified of your estime, and the misfortunes that I have spoken to you of were born of isolation and the extreme authority of several members left alone.

Saint-Just defending Robespierre in his last, undelivered speech, July 27 1794

One brings St. Just, Dumas and Payan, all of them shackled, they are escorted by policemen. They stay a good quarter of an hour standing in front of the door of the Committee’s room; one makes them sit down onto a windowsill; they have still not uttered a single word, pleasant people make the persons who surround these three men step aside, and say move back, let these gentlemen see their King sleep on a table, just like a man. Saint-Just moves his head in order to see Robespierre. Saint-Just’s figure appeared dejected and humiliated, his swollen eyes expressed chagrin.

Faits recueillis aux derniers instants de Robespierre et de sa saction, du 9 au 10 thermidor (1794) by anonymous.

The Committee of General Security was being spied on by Héron, D…, Lebas: Robespierre knew, through them, word for word, everything that was happening at said committee. This espionage gave rise to more intimate connections between Couthon, Saint-Just and Robespierre. The fierce and ambitious character of the latter gave him the idea of establishing the general police bureau, which, barely conceived, was immediately decreed.

Révélations puisées dans les cartons des comités de Salut public et de Sûreté générale ou mémoires (inédits) (1824) by Gabriel Jérôme Sénart.

Intimately linked with Robespierre, [Saint-Just] had become necessary to him, and he had made himself feared perhaps even more than he had desired to be loved. One never saw them divided in opinion, and if the personal ideas of one had to bow to those of the other, it is certain that Saint-Just never gave in. Robespierre had a bit of that vanity which comes from selfishness; Saint-Just was full of the pride that springs from well-established beliefs; without physical courage, and weak in body, to the point of fearing the whistling of bullets, he had the courage of reflection which makes one wait for certain death, so as not to sacrifice an idea.

Memoirs of René Levasseur (1829) volume 2, page 324-325.

Often [Robespierre] said to me that Camille was perhaps the one among all the key revolutionaries whom he liked best, after our younger brother and Saint-Just.

Mémoires de Charlotte Robespierre sur ses deux frères (1834) page 139.

After the month of March, 1794, Robespierre's conduct appeared to me to change. Saint-Just was to a great degree the cause of this, and this leader was too youthful ; he urged him into the vain and dangerous path of dictatorship which he haughtily proclaimed. From that time all confidences in the two committees were at an end, and the misfortunes that followed the division in the government became inevitable. […] We did not hide from [Robespierre] that Saint-Just, who was formed of more dictatorial stuff, would have ended by overturning him and occupying his place ; we knew too that he would have us guillotined because of our opposition to his plans; so we overthrew him.

Memoirs of Bertrand Barère (1896), volume 1, page 103-104.

About this time Robespierre felt his ambition growing, and he thought that the moment had come to employ his influence and take part in the government. He took steps with certain members of the committee and the Convention, asking them to show a desire that he, Robespierre, should become a member of the Committee of Public Safety. He told the Jacobins it would be useful to observe the work and conduct of the members of the committee, and he told the members of the Convention that there would be more harmony between the Convention and the committee if he entered it. Several deputies spoke to me about it, and the proposal was made to the committee by Couthon and Saint-Just. To ask was to obtain, for a refusal would have been a sort of accusation, and it was necessary to avoid any split during that winter which was inaugurated in such a sinister manner. The committee agreed to his admission, and Robespierre was proposed.

Ibid, volume 2, page 96-97

The continued victories of our fourteen armies were as a cloud of glory over our frontiers, hiding from allied Europe our internecine struggles, and that unhappy side of our national character which acts and reacts so deplorably as much on the whole population as on our nghts and our manners. The enthusiasm with which I announced these victories from the tnbune was so easily seen that Saint- Just and Robespierre, being in the committee at three in the morning, and learning of the taking of Namur and some other Belgian towns, insisted for the future that the letters alone of the generals should be read, without any comments which might exaggerate their contents. I saw at once at whom this reproach was directed, and I took up the gauntlet with the deasion of a man willing to once more merit the hatred of the enemies of our national glory, and the bravery of our armies. Then Samt-Just cried, “ I beg to move that Barère be no longer allowed to add froth to our victories.” […] While Saint-Just was reproving me, Robespierre supported the longsightedness of his friend… […] The next day my report on the taking of Namur was somewhat more carefully drawn up, and I alluded to the observation of my critics, who were envious of the power of public opinion in favour of our troops, then busied in saving the country. This phrase in my report was much commented on, although its meaning was only clear to those who had heard the debate in the committee on the previous evening “Sad are the tunes, sad is the period, when the recital of the triumphs and glories of the armies of the Repubhc is coldly hastened to in this place! Henceforth liberty will be no longer defended by the country, it will be handed over to its enemies!”This pronouncement was not of a nature to be forgiven by Saint-Just and Robespierre, so they determined to supplant me with regard to these reports. They forced that idiot Couthon to attend the Committee of Public Safety at eleven in the morning, before I got there Couthon asked for the letters of the generals that had come in during the night, and took his usual seat at the back of the hall, waiting until the assembly was sufficiently full for him to announce the victones. About one, Couthon, being paralysed and unable to stand up in the tribune, coldly read the news from the armies from his place. This time, no effect was produced in the Assembly, or upon the public. This attempt, authorised by Robespierre and Saint-Just, having missed fire completely, the committee signified its dissatisfaction at the innovation.

Ibid, volume 2, page 123-125

After his return from Fleurus, Saint-Just remained some time in Paris, although his mission as representative to the armies of the Sambre and Meuse and the Rhine and Moselle was unfinished. The campaign was only beginning, but he had several projects in hand, and he stayed in committee, or rather his office, where he was always absorbed and thoughtful. Robespierre, in speaking of him at the committee, said familiarly, as if speaking of an intimate friend: ”Saint-Just is silent and observant, but I have noticed, in his personality, he has a great likeness to Charles IX.” This did not flatter Saint-Just, who was a deeper and cleverer revolutionist than Robespierre. One day, when the former was angry about several legislative propositions or decrees that did not please him, Saint-Just said to him, “Be calm, it is the phlegmatic who govern.”

Ibid, volume 2, page 139

This tyrannical law was the work of Saint-Just Consult the Momteuv of the 22nd of Germinal, where it is reported with the explanation of his motives, and you will see that, if there had been no committee, SamtJust would have used his power with as much dictatorial fanaticism as did Manus, that great enemy of the Roman anstocracy. Robespierre’s fnend never forgave me for having dimmished the force of this blow. Whilst I was at the tnbune of the Convention, he came, with someone unknown, and perused my register of requisitions. He took down certain names, and some days after, towards midnight, Robespierre and Saint-Just entered the committee, where they did not usually come (for they worked in a private office, under pretext that their duties were completely private) A few moments after their entry Saint-Just complained of the abuse I had made of the requisitions, which had been granted, said he, in such profusion that the law of the 21st of Germinal had become null and void.

Ibid, volume 2, page 146

Robespierre, Saint-Just and Couthon were inseparable. The first two had a dark and duplicitous character; they pushed away with a kind of disdainful pride any familiarity or affectionate relationship with their colleagues. The third, a legless man with a pale appearance, affected good-nature, but was no less perfidious than the other two. All three of them had a cold heart, without pity, they interacted only with each other, holding mysterious meetings outside, having a large number of protégés and agents, impenetrable in their designs.

Révélations sur le Comité de salut public by Prieur-Duvernois

Robespierre, who had great confidence in Le Bas because he knew his wise and prudent character well, had chosen him to accompany Saint-Just, whose burning love of the fatherland sometimes led to too much severity, and who had a tendency to get carried away. […] [Saint-Just] also had friendship for me and came often enough to our house. […] Finally our providence, our good friend Robespierre, spoke to Saint-Just to engage him to let me depart with them, along with my sister-in-law Henriette. He consented, but with some conditions.

Memoirs of Élisabeth Lebas (1901)

Volume 8 — page 153. ”Saint-Just, his (Robespierre’s) only confident.” His only confident?

Élisabeth Lebas corrects a passage in Alphonse de Lamartine’s Histoire des Girondins (1847)

The Lamenths and Péthion in the early days, quite rarely Legendre, Merlin de Thionville and Fouché, often Taschereau, Desmoulins and Teault, always Lebas, Saint-Just, David, Couthon and Buonarotti.

Élisabeth Lebas regarding visitors to the Duplay’s during the revolution

—

When arriving in Paris in September 1792, Saint-Just first lived on No. 7 rue de Gaillon up until March 1794, and then on No. 3 rue de Caumartin (today’s No. 5) up until his death. Both those places were within a ten minute walking distance from Robespierre’s home on 398 Rue Saint-Honoré.

Saint-Just was away from Paris (and therefore Robespierre) on missions between March 9 to March 31, October 17 to December 4, December 10 to December 30 (1793), January 22 to February 13, April 30 to May 31 and June 10 to June 29 (1794).

#sj and max holding hands 🤗💓#robespierre#saint-just#maximilien robespierre#louis antoine de saint just#barère#élisabeth lebas#philippe lebas#frev#frev friendships#long post#saintspierre

203 notes

·

View notes

Text

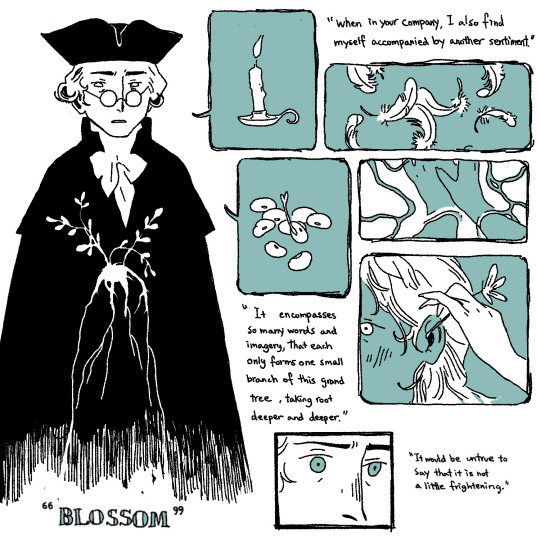

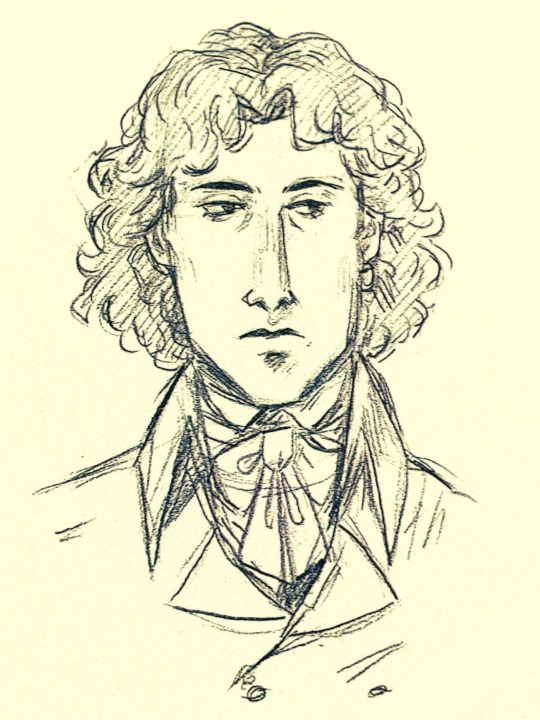

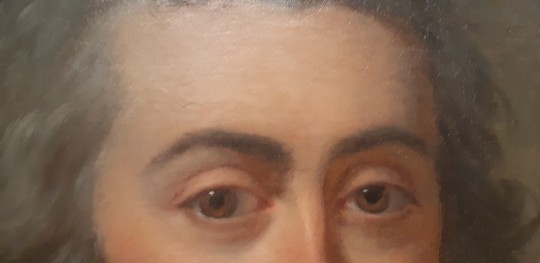

Every few months I’ll drop a sj headshot and then forget about this app

214 notes

·

View notes

Text

Je ne suis d'aucune faction; je les combattrai toutes

#My art#Yeah right#Saint-Just#French Revolution#Referenced off the Prud'hon and Verrier-Maillard portraits

130 notes

·

View notes

Text

Changes in the Committee of the Public Safety:

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

a colorful cast of characters (real)

#saint-just#oh god do i tag them all#saint just#frev#ltelv#la revolution francaise#terror bbc#un peuple et son roi#saint just et la force des choses#les visiteurs 3#danton 1983#art#please do not mind me i am hungry for notes

103 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Happy Valentine’s Day!

747 notes

·

View notes

Text

back for thermidor..

323 notes

·

View notes

Text

154 notes

·

View notes

Text

What was the police générale (Police Bureau) ?

Long post! I missed doing these analysis posts! More under the cut. Please feel free to let me know if I need to correct/add any info!

There is a lot of confusion amongst frev hobbyists and historians alike regarding the Police Bureau set up by the Committees in April 1794. Hopefully this analysis will better present it to the frev community here. The Bureau is often wrongly presented as a "Robespierrest power-grab" when in hindsight and more careful analysis has taken place, it appears to be more of an unfortunate coincidence that Robespierre, Saint-Just, and Couthon were signing a majority of the decrees and statements put out from the Bureau. The rest of the CSP, and including Saint-Just- who gave the speech presenting it to the Convention on behalf of both of the leading committees were all largely preoccupied with military matters and missions to the provinces. In fact, Saint-Just, Robespierre, and Couthon did attempt and succeed in passing Bureau document reviews off to other CSP members like Carnot, in some instances. Robespierre's reviews of many documents were vague and often called for further examination- not immediate trial, or let alone condemnation. Robespierre (and likely Couthon's) ill-health left them confined to Paris- someone still had to be there to oversee matters in a committee stretched to its very limits.

The idea that Robespierre, Couthon, and Saint-Just- who was gone away to mission only days after the Bureau came into existence were "terrorizing" the public with this measure is entirely anachronistic reactionary propaganda. Also, it is important to acknowledge the ever-growing rift between the CSP and the CSG- although this bureau in theory was probably intended to be reconciliatory (as many of SJ's proposals were) and alleviate the strain the vast amount of these sorts of cases had on the CGS, it really only divided them further in many ways. Regardless of SJ's and the entire CSP's intent with creating this bureau, in reality it sowed more seeds of envy and distrust amongst the two leading Convention committees.

The two leading Convention committees issued these 18 decrees in alignment with the speech Saint-Just gave on the CSP and CSG's behalf on the creation of the police générale on 26 germinal an II ( 15 April 1794). This is approximately 10 days after the Indulgents/Dantonists' trial and executions, for a timeline reference. However, Saint-Just was never one to willingly make a speech without carefully preparing it. Couthon originally presented amendments 1-7, which passed unanimously. Saint-Just modified Article 7 and introduced Articles 8-15 during his speech. This post is quite long but I recommend checking out Saint-Just's personal script for the articles he introduced (These can be found in the 2004 folio-histoire edition of his Oeuvres complètes, and probably other editions too.)

Articles:

Art. 1- Les prévenus de conspiration seront traduits de tous les points de la République au tribunal révolutionnaire à Paris.

Art. 2- Les Comités de salut public et de sûreté générale rechercheront promptement les complices des conjurés, et les feront traduire au tribunal révolutionnaire.

Art. 3- Les commissions populaires seront établies pour le 15 floréal.

Art. 4- Il est enjoint à toutes les administrations et à tous les tribinaux civils de terminer dans trois mois, à compter de promulgation du présent décret, les affaires pendantes, à piene de destitution ; et, à l'avenir, tous les affaires privées devront être terminéés dans le même délai, sous la même piene.

Art. 5- Le Comité de salut public est expressément chargé de faire inspecter les autorités et les agents publics chargés de coopérer à l'administration.

Art. 6- Aucun ex-noble, aucun étranger des pays avec lesquels la République est en guerre, ne peut habiter Paris, ni les places fortes, ni les villes maritimes, pendant la guerre. Tout noble ou étranger dans le cas ci-dessus, qui y serait trouvé dans dix jours, est mis hors la loi.

Art. 7- Les ouvriers employés à la fabrication des armes, à Paris, les étrangères qui ont épousé des patriotes français ne sont point compris dans l'article précédent.

Art. 8- Le séjour de Paris, des places fortes, des villes maritimes, est interdit aux généreux qui n'y sont point en activité de service.

Art. 9- Le respect envers le magistrats sera religieusement observé; mais tout citoyens pirranse plaindre de leur injustice, et le Comité de salut public les fera punir selon la rigueur des lois.

Art. 10 - La Convention nationale ordonne à toutes les authorités de se refermer rigourousement dans les limites de leurs institutions, sans les étendre ni les restreindre.

Art. 11- Elle ordonne au Comité de salut public d'exiger un compte sévère de tous les agents, de poursuivre ceux qui serviront les complots et auront tourné contre la liberté le pouvoir qui leur aura été confié.

Art. 12- Tous les citoyens sont tenus d'informer les autorités de leur ressort et le Comité de salut public, des vols, des discourses inciviques et des acts d'oppression dont ils auraient été victimes ou témoins.

Art. 13- Les représentants du peuple se serviront des autorités constitutées et ne pourront déléguer de pouvoirs.

Art. 14- Les réquisitions sont interdites à tous autres que la commission des subsistances et les représentants du peuple près les armeés, sous l'autorisation expresse du Comité de salut public.

Art. 15- Si celui qui sera convaincu désormais de s'être plaint de la Révolution vivait sans rien faire et n'était ni sexagénaire, ni infirme, il sera déporté à la Guyane. Ces sortes d'affaires seront jugées par les commissions populaires.

Art. 16 - Le CSP encouragera, par des indemnités et des récompenses, les fabriques, l'exploitation des mines, les manufactures, le dessèchement des marais; il protégera l'industrie, la confiance entre ceux qui commercent; il dera des avances aux négociants patriotes qui offriront des approvisionnements au maximum; il donnera des ordres de garantie à ceux qui amèneront des merchandises à Paris, pour les transports ne soient pas inquiétés; il protégera la circulation des rouliers dans l'intérieur, et ne souffrira pas qu'il soit porté atteinte à la bonne foi publique.

Art. 17- La Convention nationale nommera dans son sein deux commissions, chacune de trois membres: l'une chargée de rédiger en un code succinct et complet les lois qui ont été rendues jusqu'à ce jour, en supprimant celles qui sont devenues confuses; l'autre commission sera chargée de rédiger un corps d'institutions civiles propres à conserver les moeurs et l'espirit de la liberté. Ces commissions feront leur rapport dans un mois.

Art. 18- Le présent décret sera proclamé dès demain à Paris, et son insertion au Bulletin tiendra lieu de publication dans les départements.

English translation:

Art. 1- Those accused of conspiracy will be brought before the Revolutionary Tribunal in Paris from all parts of the Republic.

Art. 2- The CSP and CSG will promptly seek out the conspirators' accomplices, and have them brought before the revolutionary tribunal.

Art. 3- The People's Commissions will be established by 15 Floréal.

Art. 4- All administrations and civil tribunals are enjoined to complete all pending cases within three months of the promulgation of the present decree, under penalty of dismissal; and, in the future, all private cases must be completed within the same time-frame, under the same penalty.

Art. 5- The Committee of Public Security/Police Bureau is expressly charged with inspecting the authorities and public officials charged with cooperating with the administration.

Art. 6- No ex-noble or foreigner from countries with which the Republic is at war may live in Paris, or in fortified towns or maritime cities, during the war. Any nobleman or foreigner in the above situation, who is found there within ten days, is outlawed.

Art. 7- Workers employed in the manufacture of weapons in Paris and foreign women who have married French patriots are not included in the preceding article.

Art. 8- Generous citizens who are not on active service are forbidden to stay in Paris, fortified towns and maritime cities.

Art. 9- Respect for magistrates will be religiously observed; but all citizens will complain of their injustice, and the CPS will punish them according to the rigor of the laws.

Art. 10 - The National Convention orders all authorities to remain rigorously within the limits of their institutions, without extending or restricting them.

Art. 11- It orders the Committee of Public Security to demand a strict account from all agents, and to prosecute those who serve plots and turn the power entrusted to them against liberty.

Art. 12- All citizens are required to inform their local authorities and the CSP of thefts, uncivil discourse and acts of oppression of which they have been victims or witnesses.

Art. 13- The people's representatives will use the constituted authorities and will not be able to delegate powers.

Art. 14- Requisitions are forbidden to anyone other than the subsistence commission and the people's representatives to the armed forces, subject to the express authorization of the CSP.

Art. 15- If the person convicted of having complained about the Revolution lives without doing anything, and is not in his sixties or infirm, he will be deported to French Guiana. These kinds of cases will be judged by popular commissions.

Art. 16 - The CSP will encourage, through indemnities and rewards, factories, the exploitation of mines, the draining of marshes; it will protect industry, the confidence between those who trade; it will give advances to patriotic merchants who offer supplies to the maximum; it will give guarantee orders to those who bring merchandise to Paris, so that transporters will not be troubled; it will protect the movement of supply ships in the interior, and will not allow public good faith to be undermined.

Art. 17- The National Convention will appoint two commissions from among its members, each with three members: one will be charged with drafting a succinct and complete code of the laws that have been passed to date, deleting those that have become confused; the other commission will be charged with drafting a body of civil institutions suitable for preserving morals and the spirit of liberty. These commissions will report within one month.

Art. 18- The present decree will be proclaimed tomorrow in Paris, and its insertion in the Bulletin will take the place of publication in the departments.

70 notes

·

View notes

Note

Can you tell me the story of the relationship between saint-just and desmoulins? . ..

Because I couldn't understand it properly so yeah ...

The first connection between Desmoulins and Saint-Just is from 2 January 1790, when the former publishes an annonce for the latter’s recently published Organt in number 6 of Révolutions de France et de Brabant:

Organt, poem in twenty verses, with this epigraph: Vous, jeune homme, au bon sens avez-vous dit adieu ? And this preface: J’ai vingt ans, j’ai mal fait, he pourrai faire mieux.

A few months later, we find the following letter from Saint-Just to Desmoulins. It is undated, but can be traced to May 1790. The letter makes Desmoulins, alongside Robespierre, who he wrote a letter to the following year, the only revolutionaries Saint-Just is confirmed to have contacted prior to heading to Paris in 1792. Unlike in the case of Robespierre however, the letter to Desmoulins implies a correspondence was actually picked up between the two:

Monsieur,

If you were not so busy I would tell you some more details about the Chauni assembly where one can find men of considerable calibre and quality. I was received in spite of my youth. Sieur Gelli, your compatriot from Vermandois had denounced me. He was thrown out bodily. We saw your compatriots, M. Saulce, M. Violette and others, by whom I was received with great courtesy. There is no point telling you (because you are not fond of foolish praise) that your region is proud of you. You will have known before I did that the department is fixed at Laon. Is that good or is that bad for one or other of the towns? It seems to me that it is no more than a point of honour between the two towns and points of honour are of little importance. I took the tribune; I worked with the intention of carrying the day on the question of the chief place but I did not follow on, I left, weighed down with compliments like a donkey burdened with relics, having, however, the assurance that at the next legislature I could be with you in the national assembly. You had promised to write to me, but I see clearly that you will not have the time. I am free as of now. Should I return to you or remain amongst the foolish aristocrats in this part of the world. At the time of my return from Chauni the peasants from my region came to look for me at Manicamp. The Comte de Lauraguais was greatly astonished by this rustic-patriotic ceremony. I led them all to his house for a visit. They said that he was out in the fields, however, like Tarquin, I had a rod with which I cut off the head of a nearby fern beneath the window of the castle and without a word we made a volte face. Farewell my dear Desmoulins. Write to me if you have need of me. Your latest issues are full of excellent things. Apollo and Minerva are still with you and are not displeased. If you have anything to say to your people in Guise I will be seeing them again in eight days’ time from Laon where I will be going on specific business.

Goodbye again: glory, peace and patriotic rage.

Saint-Just

I will read you this evening since I have only spoken to you of your recent issues by saying yes.

Different feelings can however be found a year later, in a letter Saint-Just adressed to Villain Daubigny on July 20 1791 (it is dated 1792 in Oeuvres complètes de Saint-Just, but Saint-Just’s biographer Bernard Vinot points out that this is most likely an error, since all the events it makes allusions to took place the previous year):

…Go and see Desmoulins, embrace him for me, and tell him that he will never see me again, that I esteem his patriotism, but that I despise him, because I have penetrated his soul, and because he fears that I will betray him. Tell him to not abandon the good cause, and recommend it to him, because he does not yet possess the audacity of magnanimous virtue.

What exactly had happened between the two for Saint-Just to write this about Desmoulins is unknown. The same can be said about the question regarding where and when the meeting between them he alludes to here played out, since neither of them are confirmed to have left their respective cities in 1791.

Yet another year later, in September 1792, both Saint-Just and Desmoulins were elected deputies for the National Convention, meaning the former came to settle in Paris on Rue de Gaillon 7, around 2,5 km from the latter’s home on Rue du Théâtre 1 (today Rue de l’Odeon 28). Aside from the fact both were fervent montagnards, I have not been able to find any connection between them until the second half of the following year, with the release of Desmoulins’ Lettre de Camille Desmoulins, député de Paris à la Convention, August général Dillon en prison aux Madelonettes. In it, Saint-Just, who had accused Dillon of having been asked to lead an uprising to put the dauphin on the throne and declare Marie-Antoinette regent on June 2 1793, got described the following way in a footnote:

After Legendre, the member of the Convention who has the highest opinion of himself is Saint-Just. One can see by his gait and bearing that he looks upon his own head as the corner-stone of the Revolution, for he carries it upon his shoulders with as much respect and as if it was the Sacred Host. But what makes his vanity killing is, that some years ago he published an epic poem in twenty-four cantos entitled Argant [sic]. Rivarol and Champcenetz, from whose microscope, used in the interests of the Almanach des grands hommes, not a single verse, not a single hemistich in France has ever escaped, have in vain gone searching for this; they who have hunted up even the least little scrap of literature have not seen Saint-Just’s epic poem in twenty-four cantos. After such a misadventure, how can he show himself?

According to some sources, the ”he carries his head like the Sacret Host” comment was a reply to something Saint-Just had himself said about Desmoulins. Marcellin Matton published in 1834 an anecdote (which it is presumed he obtained from Desmoulins’ mother- or sister-in-law) in which Guillaume Brune has a meeting with the Desmoulins couple at the time of the numbers of the Vieux Cordelier being released. The following conversation would then have played out:

”…You [Brune said] are also read by Barère who recognizes himself; by Saint-Just, who promised to make you carry your head like Saint Denis.”

”That’s true,” [Desmoulins] replied, ”I remember it: it was a very bad joke, and my answer was much better. Have you seen my letter to Dillon? In the approach and posture of Saint-Just, we see that he regards his head as the cornerstone of the republic, and that he carries it on his shoulders with respect like a holy sacrament. Was I wrong, and do you think that for such a good joke he would want to kill me? I only ask him for one favor, and that is to wait until he has given a valid response.”