#cyclicaltime

Text

“When I did the bulk of the work on my two published novel-length books (Birding in the Face of Terror, published in 2020, and The Peasant and the King in 2022), I thought I was a fairly standard issue neo-Advaita pantheist, even though both manuscripts were filled with evidence to the contrary. My social media presence back then was peppered with frequent quotes from Ramana Maharshi, Rupert Spira, Maharaj Nisargadatta, Adyashanti et al about transcending the ego and overcoming the illusion of self, while my books offered an approach to non-duality in direct contradiction to all of it, with notions I often didn’t fully understand but felt compelled to write.

As it turns out, my neo-Advaita phase probably stemmed from a rough chapter of mid-life, during which I would’ve gladly disappeared at times. I wanted to escape the consequences of a life that had seemed to go off the rails and become a slow-motion train wreck. In truth, it didn’t and wasn’t, and I’m forever grateful I stuck around to find that out. I’m not saying this is the reason why everyone who follows these modern non-duality salesmen is attracted to neo-Advaita metaphysics, but it is a common reason, I believe, why “overselved,” oppositional mystics raised in the hyperindividualistic West are eager to settle for its half-truth. These familiar characters are given names as the dual narrators of Birding and backstories detailing their irreligious desire to disappear — Pedro on a mountaintop and Joseph in a man cave — whereas the anonymous protagonist of Peasant navigates a new trail along a more traditional path beyond the stultifying confines of exoteric religion. In both cases, the answers they find are world-affirming and life-embracing. In spite of what I believed at the time, given the self-appointed task of laying down written testimony in paperback form for posterity, I took aim for the whole truth and nothing but nor short of the whole truth.

This book, I believe, became a necessary effort to unpack the difference between them, the half and the whole.”

— excerpt from the Introduction to “I and I: A Perennialist Theory of Reincarnation and Cyclical Time”

Coming to the ND Media Bookstore in June

#I_and_I #perennialism #reincarnation #CyclicalTime #waldonoesta #NDMedia

0 notes

Photo

[MOFATEOAGD C11 a pregnant silence]

#MountainsOfFlame#hunting#farming#stalker#dagaz#DagazRune#MarketDay#deadHour#night#pasture#PublicHoliday#vacation#ChatteringClasses#CyclicalTime#AgriculturalRevolution#BriefLives#borderless#darkness#sing#sculpt#dawn#PrimalWar#AboveAndBeyond#LoversOfTheEarth#SpiritualCourage#atavistic#promethan#AtavisticPrometheanism

0 notes

Text

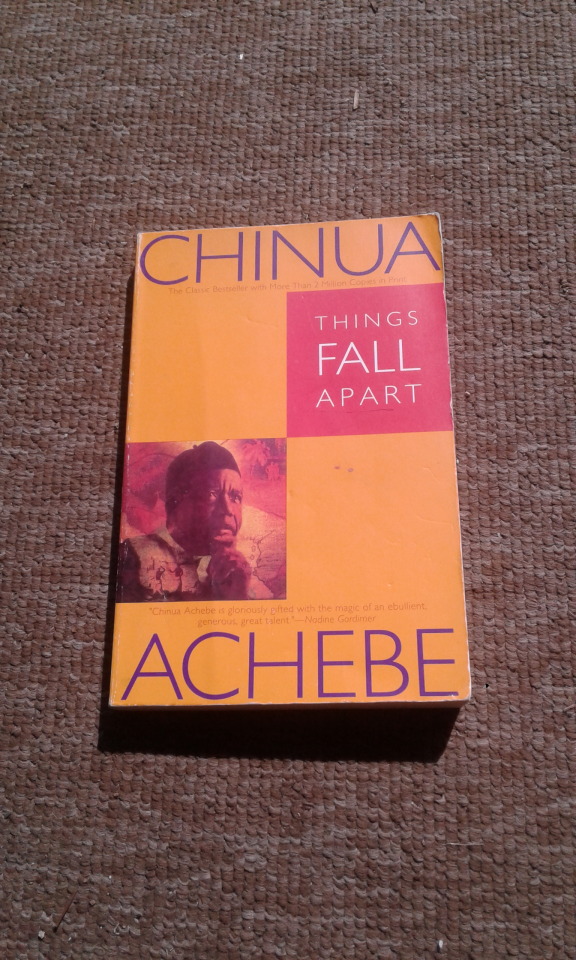

“The Second Coming” Keeps On Coming: Re-examining Yeats, in the Context of the Recent American Election, Through the Works of Joan Didion and Chinua Achebe

“Things Fall Apart" by Chinua Achebe; Didion's book not pictured as I have lent it out.

There exist at least two books in the world that are titled after lines in “The Second Coming”, a poem written in 1919 by William Butler Yeats; and when I say “the world” I mean “the world”. I know that they exist because I have read them. The first of these is called “Slouching Towards Bethlehem”, and it is by California journalist and fiction writer Joan Didion. It is a collection of narrative essays built around the concept of society’s increasing atomization. The second is called “Things Fall Apart”; it is a fictional narrative by Nigerian Igbo writer Chinua Achebe, and its topic is very similar: the fictional story of an Igbo man’s tribal and familial relationships, and his first encounters with white missionaries, are used to illustrate the erosion of group solidarity. And so from opposite corners of the globe we hear the warning that “things fall apart; the center cannot hold”. Our bonds and our social ties are becoming ever more fractionalized as our people and our systems remove relationships from their context and as we bask conveniently in our individualism. We do not stand together for long before we begin to stand against one another or retreat into our own isolations.

I spoke about these books in the order in which I read them, but that is the reverse order in which they were written. Chinua Achebe published “Things Fall Apart” in 1958; Joan Didion published the pieces in her collection during the period between 1961 and 1968, although the particular essay for which the collection was named was published in 1967 - almost ten years after Achebe’s novel. Whether she was aware of Achebe or not during this time is unclear, but there is certainly ample reason for the contemporaries to have been thinking along similar lines. And what is this reason? It is simple: Yeats believed in circular time.

A poem entitled “The Second Coming” already implies a sense of repetition. When Yeats wrote it in 1919, the effects of modernization were already in full swing. Industrial capitalism and globalization were fueling the rise of a consumer society through an emerging middle class. There had been globalization before, and capitalism before, and technological advances and even consumers before, but Yeats lived on the cusp of a change in the scale of all these things that served to make them stand out. The atomization that flourishes alongside an individualist and worldly middle class is not an event or a moment in time so much as it is a tendency. Moreover, it is a tendency that will continually be captured in stop-motion every couple of decades.

That is why, in 1958 and again in 1967, Yeats was resurrected twice at opposite ends of the earth, but for the same reason. Achebe was writing about the past; Joan Didion was writing about the present and future - but they wrote about the same phenomenon. Didion had gone to Haight-Ashbury to live with the hippies, talk to the runaway youths, and to try to understand the social and systemic tides behind the blooming counterculture. She writes of them, “We were seeing something important. We were seeing the desperate attempt of a handful of pathetically unequipped children to create a community in a social vacuum. Once we had seen these children, we could no longer overlook the vacuum, no longer pretend that society’s atomization could be reversed [...] we had somehow neglected to tell these children the rules of the game we happened to be playing” (p. 122-123). Everybody is on their own “trip” here - symbolically, not just the children, but the adults of America as well. Because of this, the youth have no concept of their relationship to society, or how to find a meaningful place within it. There seems to be no way to gracefully accommodate the needs of both the parents and the children; they’ve lived in such separate worlds for too long, and the world has changed too much, too quickly.

Meanwhile, the children of Achebe’s Igbo clan, presumably a hundred years before the hippie children stormed Haight-Ashbury, are facing a similar problem. There are holes in the fabric of their tribal education that have left them feeling isolated and hungry. Nwoye, son of the wrathful warrior Okonkwo, feels betrayed by his father’s prideful bouts of cruelty. It is these holes that the English missionaries exploit when they come to assemble converts to their church. In Nwoye’s case, “the hymn about the brothers who sat in darkness and in fear seemed to answer a vague and persistent question that haunted his young soul” (p. 147). Thus, it is their own clansmen who establish the English government on tribal land; it is the Igbo people who whip and fine them for pursuing their own customs against the will of the white man; it is their own race acting as interpreter in favor of the British crown, and because their numbers have dwindled or have become divided and filled with doubt, they have no force for resistance.

Fast forward to the “now”. A little bit of research yields some quick results: Yeats has infiltrated book title after book title. Time is cyclical, but like a spiral it trends outward. The atomization is not repeating itself - rather, it is increasing in entropy. It is a trend that is trending ever more towards the extreme of itself. We talk to people, in moments, from all over the world. The ether is constantly abuzz with the voices of billions. There has been another technological revolution, which has left us with the same types of benefits and problems as the ones before, without first having rectified the old problems. The children of Haight-Ashbury were left to their “trips”, the people who read Joan Didion’s essay enjoyed it but completely missed its point, and the isolation brought about by individualist consumerism and technologically driven capitalism continued to grow. It wasn’t painful for everyone, and often the pain wasn’t even immediate when it existed, but still it affected us; and for many of us who believed we were happy, it came in the form of a “vague and persistent question”, like the one that had haunted Nwoye. “Things fall apart; the center cannot hold…”

Now we are turned against ourselves due to that atomization, due to the individualism that we had been taught to think of as “good” because it allowed us to come to our full potential, because it allowed us to manifest progress. We are so specialized and specific that we have found seemingly insurmountable differences even among those of us who are supposed to be our greatest allies. It has been like this, but I write about it now because the recent American election has splattered it with such stark colors. We are seeing something important. We are seeing citizen against citizen, working class against working class, feminist against feminist, racial minority against racial minority, neighbor against neighbor, friend and family against friend and family, and so on. It is the schisms of our own tribe that really bring disintegration. And in a global society, it becomes increasingly clear that these struggles are just variations on the simple, age-old theme of human against human, spurred by the isolation that is a guard to our self-interest. We tried to create community, but there is still a vacuum.

In the preface to the collection “Slouching Towards Bethlehem”, Joan Didion talks about not being heard. “I suppose,” she writes, “almost everyone who writes is afflicted some of the time by the suspicion that nobody out there is listening” (p. xii). Perhaps that is why our writers feel the need to say the same things over and over again. I’m sure that is why I am writing this now. She’d painted this elaborate picture of life up in Haight-Ashbury; she’d drawn the vivid comparison to the Yeats poem; she’d implicated the structure of American society in the shattering of the mirrors that displayed the youth; but people thought that she was merely covering a fashion trend. The gyre is still widening. But despite entropy, I wonder to myself: might we still prove Didion wrong? Might we yet stop living cyclically Achebe’s tragedy, which we are cursed to enact again and again as we get lost inside our differences? Can we stop referencing “The Second Coming”? Can we, in fact, reverse the atomization of society?

#chinuaachebe#joandidion#yeats#thesecondcoming#thingsfallapart#socialdivision#americanelection#election2017#capitalism#industrialization#globalism#technology#cyclicaltime#circulartime#repeatinghistory#human relationships#joan didion#chinua achebe#american election#cyclical time#the second coming#poetry#mythology#culture#sacred experience#religion#spirituality#colonialism#racism#africa

1 note

·

View note

Photo

#fbf to our time in #duvall a few weeks ago. ⏳ ⏰ ⏳ This beauty was in the final stretch of arriving at the girl's #survivalskills camp. 💚So much love to #was #wildernessawarenessschool for all they are and all they do, 💚 but this post is mostly about my love for #cyclicaltime #cyclesoflife 《《《 True confession: I shrieked with joy on the first morning when I saw this. 😍 So many teaching moments came from this aztec/maya inspired sculpture. 》》》 On our final day, we were blessed with the light of a sweet little sun goddess in the car with us. Inbetween conversations about chosen pronouns, myself + 5yo & 3 yo, dove into convos about #cycles and the cycles of cycles (because she wondered why I was IN LOVE with this structure) Death & rebirth of seasons ❄🌱☉🍁❄, days 🌞🌚🌞, people/bodies, and the moon 🌕🌖🌗🌘🌑🌒🌓🌔🌕 Shaking the concepts of linear time ⌛ and scarcity early, because who needs that??!? 😁 Reminding tiny human of their innate power and ability to move with their own energy cycles - not externally imposed systems that try to shame us for moving in rhythm with our own magic. But mostly as usual, just talking to remind myself. 😜

0 notes