#farming

Text

In a conversation with Civil Eats, lead author Jason Hawes, a Ph.D. student at the University of Michigan, said this his team compiled “the largest data set that we know of” on urban farming. It included 73 urban farms, community gardens, and individual garden sites in Europe and the United States. At each of those sites, the research team worked with farmers and gardeners to collect data on the infrastructure, daily supplies used, irrigation, harvest amounts, and social goods.

That data was then used to calculate the carbon emissions embodied in the production of food at each site and those emissions were compared to carbon emissions of the same foods produced at “conventional” farms. Overall, they found greenhouse gas emissions were six times higher at the urban sites—and that’s the conclusion the study led with.

But not only is 73 a tiny number compared to the data that exists on conventional production agriculture, said Omanjana Goswami, an interdisciplinary scientist at the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS), but lumping community gardens in with urban farms set up for commercial production and then comparing that to a rural system that has been highly tuned and financed for commercial production for centuries doesn’t make sense.

“It’s almost like comparing apples to oranges,” she said. “The community garden is not set up to maximize production.”

In fact, the sample set was heavily tilted toward community and individual gardens and away from urban farms. In New York City, for example, the only U.S. city represented, seven community gardens run by AmeriCorps were included. Brooklyn Grange’s massive rooftop farms—which on a few acres produce more than 100,000 pounds of produce for markets, wholesale buyers, CSAs, and the city’s largest convention center each year—were not.

And what the study found was that when the small group of urban farms were disaggregated from the gardens, those farms were “statistically indistinguishable from conventional farms” on emissions. Aside from one high-emission outlier, the urban farms were carbon-competitive.

157 notes

·

View notes

Text

MY strawberries are blooming, which makes me think back to this photo from when I was doing a major "update" of the beds. I hope we have BUCKETS of them this year. This was 2019. The next year we were into the pandemic, and nothing has ever felt the same.

I had supervision and help. Of course. Always.

[ID: A woman in tank top and shorts, kneeling by raised beds of strawberries. There are several trays of new plants to be planted, and everything looks springlike and green. The second photo is a folded piece of black landscape fabric. Two large white paws and a tabby tail sticking out of the folds are a cue that there is a concealed cat.]

#strawberry#cat#farmblr#farming#permaculture#grow your own food#planting#solarpunk#gardening#cats man

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

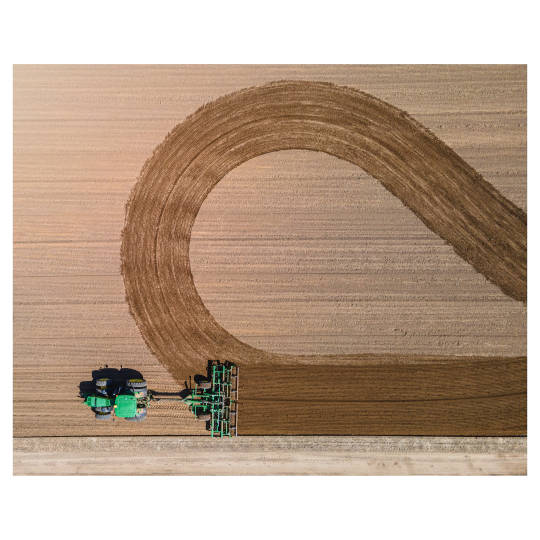

chemin champoux, saint-paul-de-joliette champoux

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

#i just kinda want to see what happens#kets kerfuffle#soil#dirt#farming#geology#agriculture#rocks#science

28K notes

·

View notes

Text

12K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Credit: Backroad-life

#horse#horse head#nature#winter#snow#snowflakes#animal#equine#equestrian#equestrainlife#farm#ranch life#ranching#farming#farmcore#bridle#tack#horse riding#mammal#horseback riding#rustic#countryside#wild west#cowgirl#horseblr

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

#kerits for everyone!!#cottagecore#my gifs#winnie the pooh#cartoon#nostalgia#nostalgiacore#farmcore#farming#nature#naturecore#animation#gif

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Bat pest.

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

So I'm trying to make folk linen pants from sowing to sewing.

Second post (here's first)

It's been about 60 days since sowing (it's 22nd of June). It's looking so pretty and started blooming about 55th day. I've been watering it one or two wheelbarrows of every 2 weeks, which I thought would be too little but it's growing pretty good. It's still not that high (about over the knee) and I doubt it'll get much higher sadly. That means lower grade of fibers but whatever. It'll be fine.

Every now and again there are parts laying down and I've been seeing some hares running about so they probably hide in it tramping down the plants. But it gets up no problem so all good. Maybe next time I'll put up a little fence around it.

Also idk when should I harvest it bc all the info is about oil flax, not textile flax, and even then it's contradictory sometimes. But either way it's around 100-120th day, so we're still only halfway.

Next up I need to start thinking about scuthing it, and it requires some equipment. But it's easy enough to build on my own probably. It should be something like this flax-brake:

And then this kind of metal comb, which I'll make just by densly putting nails in a blank:

So yeah, that's the plans for the near future. Here's a bonus flax video if you stayed till the end ❤️

#mine#flax#linen#cottagecore#light academia#goblincore#farmcore#farming#gardening#folk#stroje ludowe#ludowe#len#earth to garment#sowing to sewing#fiber art#fiber crafts#textiles#textile art

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

I went down the internet rabbit hole trying to figure out wtf vegan cheese is made of and I found articles like this one speaking praises of new food tech startups creating vegan alternatives to cheese that Actually work like cheese in cooking so I was like huh that's neat and I looked up more stuff about 'precision fermentation' and. This is not good.

Basically these new biotech companies are pressuring governments to let them build a ton of new factories and pushing for governments to pay for them or to provide tax breaks and subsidies, and the factories are gonna cost hundreds of millions of dollars and require energy sources. Like, these things will have to be expensive and HUGE

I feel like I've just uncovered the tip of the "lab grown meat" iceberg. There are a bajillion of these companies (the one mentioned in the first article a $750 MILLION tech startup) that are trying to create "animal-free" animal products using biotech and want to build large factories to do it on a large scale

I'm trying to use google to find out about the energy requirements of such facilities and everything is really vague and hand-wavey about it like this article that's like "weeeeeell electricity can be produced using renewables" but it does take a lot of electricity, sugars, and human labor. Most of the claims about its sustainability appear to assume that we switch over to renewable electricity sources and/or use processes that don't fully exist yet.

I finally tracked down the source of some of the more radical claims about precision fermentation, and it comes from a think tank RethinkX that released a report claiming that the livestock industry will collapse by 2030, and be replaced by a system they're calling...

Food-as-Software, in which individual molecules engineered by scientists are uploaded to databases – molecular cookbooks that food engineers anywhere in the world can use to design products in the same way that software developers design apps.

I'm finding it hard to be excited about this for some odd reason

Where's the evidence for lower environmental impacts. That's literally what we're here for.

There will be an increase in the amount of electricity used in the new food system as the production facilities that underpin it rely on electricity to operate.

well that doesn't sound good.

This will, however, be offset by reductions in energy use elsewhere along the value chain. For example, since modern meat and dairy products will be produced in a sterile environment where the risk of contamination by pathogens is low, the need for refrigeration in storage and retail will decrease significantly.

Oh, so it will be better for the Earth because...we won't need to refrigerate. ????????

Oh Lord Jesus give me some numerical values.

Modern foods will be about 10 times more efficient than a cow at converting feed into end products because a cow needs energy via feed to maintain and build its body over time. Less feed consumed means less land required to grow it, which means less water is used and less waste is produced. The savings are dramatic – more than 10-25 times less feedstock, 10 times less water, five times less energy and 100 times less land.

There is nothing else in this report that I can find that provides evidence for a lower carbon footprint. Supposedly, an egg white protein produced through a similar process has been found to reduce environmental impacts, but mostly everything seems very speculative.

And crucially none of these estimations are taking into account the enormous cost and resource investment of constructing large factories that use this technology in the first place (existing use is mostly for pharmaceutical purposes)

It seems like there are more tech startups attempting to use this technology to create food than individual scientific papers investigating whether it's a good idea. Seriously, Google Scholar and JSTOR have almost nothing. The tech of the sort that RethinkX is describing barely exists.

Apparently Liberation Labs is planning to build the first large-scale precision fermentation facility in Richmond, Indiana come 2024 because of the presence of "a workforce experienced in manufacturing"

And I just looked up Richmond, Indiana and apparently, as of RIGHT NOW, the town is in the aftermath of a huge fire at a plastics recycling plant and is full of toxic debris containing asbestos and the air is full of toxic VOCs and hydrogen cyanide. ???????????? So that's how having a robust industrial sector is working out for them so far.

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

Agroecology in the global north needs to fully reckon with its position in the global system of imperialism and incorporate that into its analysis and demands. Our global class position as small farmers in the colonial core necessitates reckoning with class as a global phenomenon and hierarchy, before discussing it within regional or national bounds. Imperialism here taken simply as the enforced flow of value from south to north as a result of militarised capital. Agroecology (or food sovereignty movements, either way) needs to recognise how European farmers benefit from the flow of value from the lands, labour and resources of the global south. That’s not to say that capitalist competition can’t undermine efforts towards agroecological farming, but how we parse that challenge matters. It changes our focus from “globalisation” which is a critique now most commonly wielded by the far right, to capitalism. It allows us to name the system’s dynamics. Capitalist competition is what drives down production standards and with it incomes. Our demand should become to stop competing with each other and whatever that takes.

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

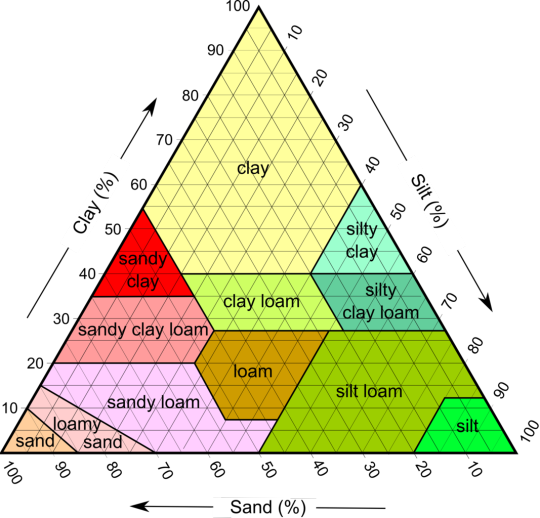

"Marginal improvements to agricultural soils around the world would store enough carbon to keep the world within 1.5C of global heating, new research suggests.

Farming techniques that improve long-term fertility and yields can also help to store more carbon in soils but are often ignored in favor of intensive techniques using large amounts of artificial fertilizer, much of it wasted, that can increase greenhouse gas emissions.

Using better farming techniques to store 1 percent more carbon in about half of the world’s agricultural soils would be enough to absorb about 31 gigatons of carbon dioxide a year, according to new data. That amount is not far off the 32 gigaton gap between current planned emissions reduction globally per year and the amount of carbon that must be cut by 2030 to stay within 1.5C.

The estimates were carried out by Jacqueline McGlade, the former chief scientist at the UN environment program and former executive director of the European Environment Agency. She found that storing more carbon in the top 30 centimeters of agricultural soils would be feasible in many regions where soils are currently degraded.

McGlade now leads a commercial organization that sells soil data to farmers. Downforce Technologies uses publicly available global data, satellite images, and lidar to assess in detail how much carbon is stored in soils, which can now be done down to the level of individual fields.

“Outside the farming sector, people do not understand how important soils are to the climate,” said McGlade. “Changing farming could make soils carbon negative, making them absorb carbon, and reducing the cost of farming.”

She said farmers could face a short-term cost while they changed their methods, away from the overuse of artificial fertilizer, but after a transition period of two to three years their yields would improve and their soils would be much healthier...

Arable farmers could sequester more carbon within their soils by changing their crop rotation, planting cover crops such as clover, or using direct drilling, which allows crops to be planted without the need for ploughing. Livestock farmers could improve their soils by growing more native grasses.

Hedgerows also help to sequester carbon in the soil, because they have large underground networks of mycorrhizal fungi and microbes that can extend meters into the field. Farmers have spent decades removing hedgerows to make intensive farming easier, but restoring them, and maintaining existing hedgerows, would improve biodiversity, reduce the erosion of topsoil, and help to stop harmful agricultural runoff, which is a key polluter of rivers."

-via The Grist, July 8, 2023

#agriculture#sustainable agriculture#sustainability#carbon emissions#carbon sequestration#livestock#farming#regenerative farming#native plants#ecosystems#global warming#climate change#good news#hope

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

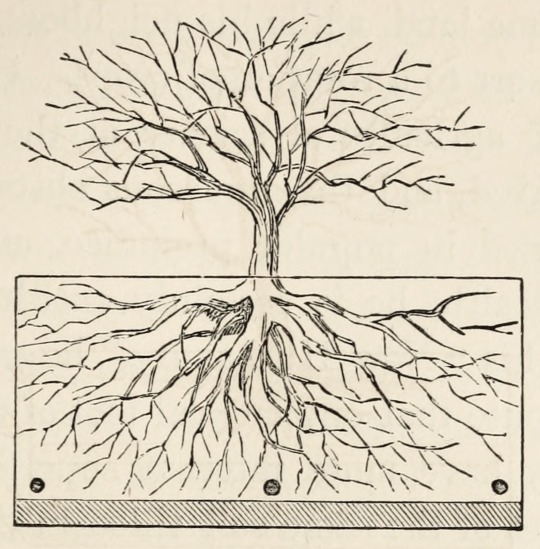

The root system of a fruit tree. Practical and scientific fruit culture. 1866.

Internet Archive

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

y’all look at my babies growing and thriving

also please ignore my other babies (my dogs) barking like they’re witnessing a murder in the background. they literally saw a strange looking leaf or something and collectively decided to go unhinged together

#mine#life updates#farmcore#cottagecore#naturecore#farming#farmlife#farm#farmers daughter#animals#baby animals#gardencore#rural#rural life#ruralcore#rural living#garden#wholesome#cowboycore#farmer’s daughter#farmers market#southern gothic#southern style#farmer’s market

2K notes

·

View notes