#chabako

Text

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

Red Crane's new tea shop is open for business!

The tea shop replaces the tea stand in the theatre district and is based on tea shops in and around Uji. I designed the chamusume (traditional tea picker) kimono, tea jar logo, and the shelves of chabako (tea boxes).

#animal crossing#acnh#new horizons#red crane memories#animal crossing new horizons#ac new horizons#acnh build#animal crossing builds#acnh exterior

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

My WVUD playlist and stream, 7/2/2022

The Hardy Tree - Shop Fronts and Parked Cars

Joys Union Group - Fig

Beverly Glenn-Copeland - Ever New (Reworked by Bon Iver & Flock of Dimes)

Ron Trent - Flowers (feat. Venecia)

Deep Throat Choir - Joyful

Syna So Pro - KICK that habit MAN

The Bobs - Psycho Killer

Asha Puthli - We're Gonna Bury the Rock with the Roll Tonight

Danielle Dax - Here Come the Harvest Buns

Gnawa Music of Marrakesh - Chabako

Moktar Gania & Gnawa Soul - Sala Nabina

Innov Gnawa - Baniya

Rabii Harnoune & V.B. Kühl - Foulani

Adrian Quesada - Puedes Decir De Mi (feat. Gaby Moreno)

The Mars Volta - Blacklight Shine

Juanita Euka - Baño De Oro

Suave - Imperatriz (Arcano 03)

Combo Alex Melero - Sentimiento

Kalabrese - Above Everything (feat. Palma Ada)

Lard Free - In A Desert / Alembic

Odd Person - Solstice Celebrations in the Sky Temple

Saqqara Dogs - Young Urban Sprawl

Ryuichi Sakamoto - Tell 'em to Me

Hollie Cook - Unkind Love

Quasi Dub Development - Supper Is Ready Jason

(listen on Mixcloud)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Guide To Japanese Tea Ceremony

The term "tea ceremony" (pronounce "sadou") in Japanese refers to a formal method of making and consuming green tea. This is a fundamental aspect of Japanese culture and is well-known not only in Japan but also throughout the rest of the world. In this post, we'll explain the origins of the Japanese tea ceremony and how to hold one properly.

Tea Ceremony History and Background

The first tea seeds were introduced to Japan during the Tang dynasty (China, 618–907), a time of intense diplomatic and cultural interactions between the two countries, and this is where the history of the Japanese tea ritual began. Beginning in the Nara era (710–794), tea plants were first developed. However, only priests and noblemen typically drank tea as a medication.

Myoan Eisai, a priest from Japan, traveled to China in 1187 to research philosophy and religion. Later, he traveled back to Japan and brought some tea seeds for his temple to flourish. He then wrote Kissa Yojoki, a book about the advantages of tea for your health. The book subsequently began to circulate widely, and ever then, tea ceremony has slowly gained popularity among Japanese Zen masters.

The tea ceremony rose to prominence as a representation of Japan's affluent elite in the thirteenth century. Only the ruling class—the samurai class—was in charge of regulating tea ceremony practices. Following then, it gradually gained popularity among the working class, first just among men. Women were not formally permitted to participate in the tea ceremony until the beginning of the Meiji period (1868–1912). Since that time, the tea ceremony has gained popularity as a distinctive aspect of Japanese culture.

How to Organize the Ceremony

Step 1: Hosting Preparation

All of the required items must be ready before the tea ceremony may start. A cup, a wooden tea stirrer, a small tea scoop, and a few other objects make up the chabako, the set of supplies used for the tea ceremony. The host must concentrate especially during this period of preparation to become serene and a source of comfort for the visitors.

Step 2: Guests' Preparations

Everyone must wash their hands before entering the tea room. In addition to ensuring hygiene, this symbolizes washing away all cares to leave the soul pure and prepared for the tea ceremony. The host will invite the visitors inside the tea room once the tea ceremony is ready. In appreciation for the preparations made by the organizer, guests are required to bow.

Step 3: Warm up the tools

All the utensils, including cups and teapots, must be cleaned with hot water before use and dried with a soft, clean cotton towel to maintain cleanliness and keep the tea warm. Every movement made by the host while warming up the apparatus should be graceful and done with dignity.

Step 4: Making Tea

Put the right amount of tea in the cup, add hot water, and stir with a chasen or tea stirrer. To begin, swirl the tea powder into the liquid at the bottom of the cup. Place the teacup on the tatami in front of the visitors when the froth has formed and you have gently stirred the surface of the cup with your hands. Don't forget to face the front of the cup toward the guests.

Step 5: Enjoying the Tea

After being welcomed by the host, the visitor will first grasp the teacup with his right hand and place it in the palm of his left hand before bowing, lifting the cup just a little, and sipping the tea. Do not drink the entire cup of tea at once. It should be consumed in three sips instead. When you have received and sipped all of your tea, you should then bow your head in appreciation. To show respect for the host, remember to point the front of the teacup when returning it.

If you are interested in Japanese tea ceremony culture and Japanese teacups, welcome to visit kimkiln.com. A variety of Chinese and Japanese vintage teacups are available for you to choose from.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 7 (29c): the Kaki-ire [書入].

◎ Kaki-ire [書入]:

In general, in an ordinary temae, while the [guests] are looking at the chaire, the teishu goes into the katte, and closes the shōji¹.

Nevertheless, there are also certain hosts who leave the shōji open, so they can address [the guests while they are inspecting the chaire]². [Ri]kyū, among others, said that, for the most part, [the shōji] should remain open [at this time]³. On occasions such as this, [when the guests have finished inspecting] the chaire, [it] should be returned to the place on the kagi-datami [to the place where the host originally put it when presenting it to the guests]⁴.

On occasions when the shōji is closed,〚when the guests are ready to return the chaire,〛if the chaire is a treasured piece, then from among the guests the one with the most experience should move onto the utensil mat. Then, one of the other people should take the chaire to the kagi-datami from where [the more experienced guest] accepts it and moves it into a certain place on the daime, so that it carefully corresponds to [its] kane [in the appropriate way]: 〚either placed in the very center as an hitotsu-mono [一ツ物], or else -- if it is an ordinary piece -- oriented so that it overlaps the center by one-third⁵.〛

When [the chaire] will be returned to its seat [after the guests have finished their haiken], if it is an ordinary piece, it is also acceptable to leave it on the kagi-datami [rather than moving it onto the utensil mat]⁶.

〚And again, if the teishu decides to open the shōji, perhaps so that he can speak [to the guests], there is the possibility that he might decide to have usucha brought out [from the katte]⁷. Because, under such circumstances, if [the most experienced guest] is unable to move onto the utensil mat [because the host is speaking to the guests from the open doorway], naturally [the chaire] should be returned to the kagi-datami⁸.

〚This was how [Ri]kyū did things -- though in the present day many chajin have been mislead, [believing that] when the host has entered the katte [even when the shōji is closed], then [the chaire] should be returned to the kagi-datami⁹. But, on the other hand, even if the teishu has left the shōji open, [if he is not actually sitting in the doorway] it may be said to be reasonable to do things in that way: so, by all means, [the chaire] should be carried onto the utensil mat¹⁰.〛

But these days, even when the teishu has closed the shōji, [even a] treasured piece is [often] returned to the kagi-datami¹¹. 〚This [ignorance of the proprieties] makes me laugh out loud¹²!〛

_________________________

◎ As was mentioned previously, this “kaki-ire” has little connection with the entry (on the chabako/sa-tsū-bako) to which it is appended. But since that entry appears to have been edited (to bring it in line with the Sen family’s official practices during the early Edo period), it is possible that this was simply another entry that became conjoined with the other as a result of the manipulation to which it was subjected, with this one reduced to the status of kaki-ire because of the way that the resulting text ended up being apparently formatted (in other words, the space that separated one entry from the next -- the entries are not numbered in the original -- was filled in with spurious text, making this entry appear to have been a part of the other, yet the lack of any real connection between the two, content wise, probably lead Tachibana Jitsuzan to decide that this entry had been added later, as commentary...i.e., as a kaki-ire appended to the other).

In his very brief commentary on this entry (indeed, besides explaining what kagi-datami [鍵疊] and tsune-no-temae [常の手前] mean, Shibayama’s only other remark is to direct the reader to this text), Shibayama says that it is important to refer to entry 36 in the Book of Secret Teachings, since it will help to put the unusual doings described in this kaki-ire, into perspective.

So, before we turn to a discussion of the kaki-ire itself, it might behoove us to look at that teaching (the complete text of which follows):

Hizō no meibutsu nado, toko [h]e bon ni te, cha ato ni agaru-koto, mochiron shōgan no gi nare-domo, toko ni sawari aru-toki ka, mata ha ni-jō-shiki nado no toko nashi no zashiki ni ha, daime ni bon-tomo ni o-kazari sōroe to, tokoro-mochi-suru-koto, toko ni agaru to dōzen no shōgan nari, mochiron chū-ō mine-zuri ni kazaru-koto nari, chawan no meibutsu mo dōzen nari

[秘藏ノ名物抔、床ヘ盆ニテ、茶後ニ上ルコト、勿論賞翫ノ儀ナレ共、床ニサワリアル時カ、又ハ二疊敷抔ノ床ナシノ座敷ニハ、臺目ニ盆共ニ御飾候ヘト、所望スルコト、床ニ上ルト同前ノ賞翫ナリ、勿論中央峰ズリニカザルコトナリ、茶碗ノ名物モ同前也].

This means, “in the case of something like a treasured meibutsu, it should be placed in the toko, on a tray: after tea [has been finished] it is lifted up [into the toko]. Naturally, though this is the most ceremonious way to appreciate [the utensil], when it is difficult for [the host] to access the toko, or else in something like a 2-mat room that does not have a toko, [the chaire] should be moved onto the daime, together with [its] tray, and displayed there [after the guests have finished their haiken]. This is what the situation demands; [displaying the chaire on the daime in this way] represents the same degree of treasuring as when [the chaire] would be lifted into the toko. Naturally, it should be displayed in the very center [of the daime], as a mine-zuri [峰ズリ]*.

“If a chawan is a meibutsu, it [should] also [handled] in this same way.”

Having grasped the reason why the chaire is moved to the utensil mat by one of the guests (after they have finished haiken), we are now prepared to consider the teachings described in this kaki-ire.

Shibayama Fugen’s version includes several sentences that are not found in the Enkaku-ji manuscript, and these have been included in the translation, enclosed in doubled brackets, as usual.

And as for Tanaka Senshō’s account of this material, it is fragmentary (and so confusing), in the same vein as what we saw in Appendix II (in the previous post). Furthermore, it combines elements from the kaki-ire that is translated here† with passages from the Book of Secret Teachings (again, in the same way as we saw in the previous post). Since it will not add anything new to our understanding, I think it would be best not to waste any more time on that version.

That said, I would like to include some additional material that has an impact on our understanding of the raison d'être of entry 29, viz. the way to seal the sa-tsū-bako with a paper tape, and the way that tape is to be cut open at the beginning of the goza. These details were conveyed to me by Kanshū oshō-sama, and are not found in any published account or commentary. His explanation will be presented in an appendix that I will attach to the end of this post.

___________

*Mine-zuri [峰摺り] means “to brush against the peak.” In other words, the center of the object is ever-so-slightly displaced from the exact center of the kane -- as a gesture of self-deprecation.

When one of the the guests arranges the chaire on the daime in this way (as will be described in this kaki-ire), he should be careful to arrange the chaire as an hitotsu-mono [一ツ物] -- that is, arrange the chaire exactly with the kane (since it is not his own chaire, but one that belongs to, and is the treasured possession, of his host).

†Subsequently, Tanaka also presents (as a completely separate entry) the kaki-ire that is translated in this post (though why he did not connect that with the marginalia that he associates only with the chabako/sa-tsu-bako entry, is difficult to understand).

Nevertheless, as is frequently the case, his version is identical to the text that is found in the Enkaku-ji manuscript (and so lacks the inclusions found in Shibayama Fugen’s teihon -- which are all found in the marginalia connected with the previous entry, though they have nothing to do with that topic), so nothing more needs to be said about it here.

¹Sōjite tsune-no-temae no toki, chaire mi-mono no aida, teishu katte ni irete, katte-shōji sashi-oku-koto ari [惣而常ノ手前ノ時、茶入見物ノ間、亭主勝手ニ入テ、勝手障子サシヲクコトアリ].

Tsune-no-temae [常の手前] means an ordinary koicha-temae.

Chaire mi-mono no aida [茶入見物の間] means when (the guests are) looking at the chaire, when (the guests are) inspecting the chaire. The haiken of the chaire (at the end of the temae).

Katte-shōji sashi-oku [勝手障子差し置く] means the shōji that acts as the door to the katte is left as it is (after the host exists the room with the last of the utensils that he is removing at that time). The next sentence (where we will consider the case where the shōji was left open) makes it clear that the shōji are closed by the host after he exits, and in that state left alone while the guests inspect the chaire.

²Mata shōji ake-nagara aisatsu-shite-iru-teishu mo ari [又障子アケナガラ挨拶シテ居ル亭主モアリ].

Shōji ake-nagara [障子開けながら] means the shōji continue to remain open.

Aisatsu-shite-iru-teishu [挨拶している亭主] means a host who addresses (the guests, through the open shōji, while they are inspecting the chaire).

In other words, some teishu prefer to leave the shōji open while the guests are inspecting the chaire, so they can interact with the guests directly at this time, and respond to their questions and comments in a timely manner.

³Kyū nado, ō-kata ake-nagara katarite-irareshi nari [休ナド、大方アケナガラ語リテ居ラレシ也].

Kyū nado [休など] means Rikyū, among others.... In other words, the influential chajin of his day.

Ō-kata [大方] means mostly, probably, for the most part. That is, Rikyū (and many of his contemporaries) said that, for the most part, the shōji should remain open at this time.

⁴Sono toki ha kagi-datami no tokoro ni chaire wo modosu nari [其時ハカギ疊ノ所ニ茶入ヲモドス也].

Kagi-datami [鍵疊] means the mat in which the ro is cut (when that mat is not the utensil mat).

In the modern temae, the host offers the chaire to the guests by placing it on the mat next to the ro. After haiken, the guests return it to the same place. This is the situation that is being described here.

While Shibayama Fugen’s teihon generally agrees with what is found in the Enkaku-ji manuscript, this particular sentence is missing.

⁵Shōji sashite-oru toki ha, hizō no mono naraba kyaku no uchi, kōsha-naru-hito, dōgu tatami [h]e itte, sate chaire wo betsu-hito, kagi-datami [h]e yaru wo uke-totte, daime-tokoro ni dōgu sō-ō ni kane yoku-oite [障子サシテヲル時ハ、秘藏ノ物ナラバ客ノ内、功者ナル人、道具疊ヘ行テ、サテ茶入ヲ別人、カギダヽミヘヤルヲ受取テ、臺目所ニ道具相應ニカネヨク置テ].

Shōji sashite-oru toki [障子差しておる時] means when the shōji have been closed (while the guests inspect the chaire).

Hizō no mono naraba [秘藏の物ならば] means if (the chaire) is a treasured piece....

Kyaku no uchi, kōsha-naru-hito [客の内、功者なる人] means among the guests (kyaku no uchi [客の内]), the most experienced person (kōsha-naru-hito [功者なる人]).

Betsu-hito, kagi-datami [h]e yaru wo uke-totte [別人、鍵疊へ遣るを受取って] means a different person (betsu-hito [別人], that is one of the other guests) takes (the chaire) to the kagi-datami (kagi-datami [h]e yaru [鍵疊へ遣る]) where it is received (uke-totte [受取って]) by the experienced guest (who is now sitting on the utensil mat).

Daime-tokoro ni dōgu sō-ō ni kane yoku-oite [臺目所に道具相應にカネよく置いて]: daime-tokoro ni [臺目所に] means on a certain place on the daime; dōgu sō-ō ni [道具相應に] means (a place) that is suitable for the utensil; kane yoku oite [カネよく置いて] means (the chaire) should be very carefully placed on its kane.

In other words, the most experienced among the guests* first moves from his seat to the utensil mat. Then another of the guests (usually the shōkyaku, but sometimes it is the last guest -- especially if the shōkyaku was the most experienced guest†) takes the chaire to the kagi-datami (in other words, to the same spot where the host placed the chaire when offering it to the guests for haiken). After placing the chaire on the kagi-datami, that guest returns to his seat, and the experienced guest (who is sitting on the utensil mat) picks up the chaire, and moves it onto the mat.

After arranging the chaire as shown in the sketch, he returns to his seat.

Here, Shibayama’s text begins to diverge from the Enkaku-ji manuscript version: kyaku chaire wo modosu-toki, teishu katte ni iri, shōji sashite araba, kyaku no uchi, kōsha naru-hito, dōgu-tatami [h]e itte, sate betsu-hito chaire wo kagi-datami [h]e yaru wo uke-totte, chaire shidai, chū-ō no hitotsu-mono, mata sa mo naki tsune-no-mono naraba, chū-ō san-bun kakari ni mo oki [客茶入ヲ戻ス時、亭主勝手ニ入リ、障子サシテアラバ、客ノ内、功者ナル人、道具疊ヘ行テ、扨別人茶入ヲカキ疊ヘヤルヲ請取テ、茶入次第、中央ノ一ツ物、又サモナキ常ノ物ナラバ、中央ノ三分掛リニモ置キ].

This means “when the guests are going to return the chiare -- if the host had closed the shōji after entering the katte -- from among the guests, the one who has the most experience moves onto the utensil mat. Then a different person takes the chaire to the kagi-datami, where it is received [by the more experienced guest] and, according to the proper way to handle [this] chaire, placed [either] in the very center as an hitotsu-mono, or, if it is an ordinary piece, placed so that it overlaps the center by one-third.”

One important point seems to be that the chaire that will be treated in this way does not have to be a meibutsu or karamono. If it is a chaire of that sort, then it is placed so that it rests squarely on the central kane; but if it is an ordinary chaire, then it is arranged so that it overlaps the central kane by one-third.

This text, which actually repeats some of what was said at the beginning of the kaki-ire, parallels more closely what Tanaka found in his “genpon” (or, perhaps, rufu-bon [流布本]) source. Thus, even though Tanaka’s text included this passage among the marginalia, it clearly was part of the kaki-ire (which his book does not designate by name‡).

__________

*This “most experienced guest” might not be the shōkyaku. Indeed, the host often invites just such a person as the second guest, so that he will be able to assist the shōkyaku if and when necessary -- and this is an example of how this may be done.

†In this case, when he notices that the last guest is finishing his inspection of the chaire, the shōkyaku moves to the utensil mat (so that the chaire will not be returned to him, as is usual). Then, when he is finished looking at the chaire, the last guest takes it to the kagi-datami, and places it there (after which he goes back to his seat). And then the shōkyaku lifts it onto the utensil mat, arranging it carefully as shown in the sketch. After which the shōkyaku also returns to his seat.

‡Perhaps to make the text appear different, rather than naming this part of the text as a kaki-ire, the editor of that edition kept it among the marginalia, as if this was something newly discovered that had not been known to the people who produced earlier versions of the Nampō Roku.

⁶Za ni kaeru, tsune-no-mono naraba, kagi-datami ni kaesu mo yoshi [座ニカヘル、常ノモノナラバ、カギ疊ニカヘスモヨシ].

Za ni kaeru [座に返る] means when (the chaire*) is returned to its seat....

Tsune no mono naraba [常の物ならば] means if it is an ordinary piece.

Kagi-datami no kaesu mo yoshi [鍵疊に返すもよし] means it is also acceptable to (simply) return it to the kagi-datami (rather than lifting it onto the utensil mat and arranging it so that it overlaps the central kane by one-third -- as Shibayama’s version indicated).

__________

*This is actually more of a guess than a literal interpretation of what is written -- though borne out by the last phrase of the statement.

⁷Mata teishu yori katte-guchi hiraki, aisatsu-shite-iru ka, arui ha usucha yō-i hakobi nado suru mo ari [又亭主ニヨリ勝手口開キ、挨拶シテ居ルカ、或ヒハ薄茶用意ハコビナドスルモアリ].

This and the next three sentences (footnotes 7 to 10) are found only in Shibayama’s version. They are missing from the Enkaku-ji manuscript (which concludes its explanation with the sentence discussed in footnote 11 -- which, in its turn, is missing from Shibayama’s account). As a result, this section of the entry has been enclosed in doubled brackets in the translation.

Teishu yori katte-guchi hiraki [又亭主により勝手口開き] means the katte-guchi is opened by the host (not by one of the guests).

Aisatsu-shite-iru ka [挨拶して居るか] means to voice a greeting; to address (the guests). In other words, the host addresses the guests after he opens the katte-guchi*.

Arui ha usucha yō-i hakobi nado suru mo ari [或は薄茶用意運びなどするもあり] means perhaps (arui ha [或は]) usucha has been prepared (usucha yō-i [薄茶用意]) to be carried out or something of that sort (hakobi nado [運びなど]), may also be done (suru mo ari [するもあり]).

As mentioned in the previous post, this statement is not entirely lucid†, though it seems to be suggesting that usucha might be served by carrying it out from the katte (rather than by performing the temae in the room).

Alternately, it could mean that the usucha utensils are carried out from the katte. But since that would seem to be the usual way things are done, it would hardly demand the special mention.

__________

*At this time, the host would discuss the chaire, and answer the guests’ questions and comments, in much the manner that things are done today.

However, it is important to point out that nothing resembling the modern stylized dialog of

“o-chaire ha...”

“Seto de gozaimasu.”

“O-saku ha...”

“Katō Gentarō de gozaimasu.”

existed before the early 20th century. Prior to that time, the exchange between host and guests was perfectly natural, and unstructured -- and lasted as long, or as briefly, as everyone felt necessary.

†Shibayama does not attempt to comment on this; and the confusing nature of the statement might be why Tachibana Jitsuzan did not copy it into the Enkaku-ji manuscript.

⁸Sayō no koto ni te dōgu-tatami sawari araba, mochiron kagi-tatami ni modosu-beshi [サヤウノコトニテ道具疊サハリアラバ、勿論カキ疊ニ戻スベシ].

Sayō no koto ni te [然様のことにて] means something like under these circumstances..., in this situation....

Dōgu-tatami sawari araba [道具畳障りあらば] means if there is some hindrance (to displaying the chaire) on the utensil mat....

Because the host would be sitting in the doorway, speaking with the guests, it would be extremely rude if one of them were to move onto the utensil mat to arrange the chaire there. The host’s presence in the doorway is what prevents them from doing this (even though he is sitting outside of the room).

Mochiron kagi-datami ni modosu-beshi [勿論鍵疊に戻すべし] means naturally (the chaire) should be returned to the kagi-datami.

⁹Kyū no sarare-shi ha kaku-no-gotoki nari-shi ni, chika-goro fu-ryōken no chajin, shu katte ni iru mo kagi-datami [h]e modoshi [休ノサラレシハ如此ナリシニ、近頃不了簡ノ茶人、主勝手ニ居ルモカキ疊ヘ戻シ].

Kyū no sarare-shi ha kaku-no-gotoki nari-shi [休のさられしはかくのごときなりしに] means Rikyū’s way of doing things was like this.

Chika-goro [近頃] means in the present day*.

Fu-ryōken no chajin [不了簡の茶人] means misguided chajin; chajin who have been misinformed.

Shu katte ni iru mo kagi-datami [h]e modoshi [主勝手に居るも鍵疊へ戻し] seems to contain a miscopied word: it should be shu katte ni iru mo kagi-datami [h]e modoshi [主勝手に入るも鍵疊へ戻し], which would mean “even if the host has entered the katte, [the chaire] is returned to the kagi-datami” -- which is what the misinformed chajin were doing†.

In other words, they misunderstand that the return of the chaire to the kagi-datami is connected with the host’s having gone into the katte. But that is not what is being said, however. When the host goes into the katte and closes the shōji, then the rule was that the chaire should be returned to the daime by the most experienced of the guests‡. But when, even though he has entered the katte, the shōji remain open so that he can interact with the guests from the doorway, it is only in this case that one of the guests should not move onto the daime; thus, the chaire should be left on the kagi-datami in this situation.

__________

*While such an expression would never have been used during Rikyū's lifetime, it is possible that three years after his death Sōkei would have written in this way, to show how Rikyū’s legacy had been repudiated by the machi-shū.

†In fact, this is the way things are always done today.

‡The reason why it was the most experienced among them who was charged with this responsibility is because he will understand where to place the chaire (so it is associated with the central kane -- which, on account of the presence of the naka-bashira and sode-kabe, is not in what appears to be the center of the mat), and whether to orient it squarely on the kane, or so that it overlaps the kane by one-third. A guest who lacks sufficient experience will likely make a mistake when trying to judge these things (thereby potentially insulting the chaire, and so, through it, the host).

¹⁰Mata ha shu no shōji-biraki iru ni mo kotowari wo mōshite, zehi-tomo dōgu-tatami ni jisan-suru mo ari [又ハ主ノ障子開キ居ルニモコトワリヲ申シテ、是非共道具疊ニ持參スルモアリ].

Shu no shōji-biraki iru ni mo [主の障子開き居るにも] means even if the teishu’s shōji has been left open (apparently this is supposed to be referring to the case where the shōji was left open after the host left the room).

Kotowari ni mōsu [理を申す] means (moving the chaire onto the utensil mat after the guests have finished their haiken) may be said to be reasonable.

Zehi-tomo [是非とも] means by all means, absolutely.

In other words, even when the host has left the katte-guchi open*, it is logical for the guests to want to move the chaire onto the utensil mat (for its own safety), so, by all means, they should do so -- this way of thinking about the situation is also possible.

___________

*The implication seems to be that perhaps this can be done even if the host has returned to the doorway, and is waiting there for the guests to finish their haiken.

¹¹Kinrai ha teishu shōji sashite-iru ni mo, hizō no mono kagi-datami [h]e modosu [近來ハ亭主障子サシテ居ルニモ、秘藏ノモノカギ疊ヘモドス].

Kinrai [近來] means these days, recently.

Teishu shōji sashite-iru ni mo [亭主障子差して居るにも] means even when the teishu has closed the shōji (after himself)....

Hizō no mono kagi-datami [h]e modosu [秘藏の物鍵疊へ戻す] means the treasured (chaire) is returned to the kagi-datami.

This is how we are taught to do things today.

As mentioned above, this concluding sentence is missing from Shibayama's version of this kaki-ire.

¹²Daishō no koto nari [大笑ノコトナリ].

Daishō no koto [大笑のことなり] means to laugh out loud; burst out laughing.

In East Asia, laughing out loud (especially in a situation where laughter would not be expected) is often a way to cover ones embarrassment, particularly when in the presence of a serious faux pas. This may be what is intended here.

==============================================

❖ Appendix: Kanshū Oshō-sama’s Explanation of an Alternative Way to Seal, and Cut Open, the Sa-tsū-bako.

According to what Kanshū oshō-sama related to me, it appears that the way the sealing of the sa-tsū-bako is described in entry 29 of the Nampō Roku is flawed (at least if the idea was to protect the integrity of the tea, as well as physically preserve it from degradation). Pasting a strip of tape around the box (or, even more, encircling the box with a piece of tape that is pasted together only at the point where the ends overlap) can hardly be said to offer anything more than token security -- and, indeed, it would not require three cuts of a knife (or even one, truth be told) to open.

Beginning when matcha came to be sold commercially in generic containers (such as tin-cans), the seal was effected by pasting a tape around the entire circumference of the can over the point where the lid joined the body. This practice has continued to be observed into modern times by certain traditional tea merchants¹³, and is said to have been based on how the wooden box in which the tea was sent to the customer (i.e., a sa-tsū-bako [茶通箱], though here we are talking about a commercial product) was prepared for dispatch to the customer¹⁴.

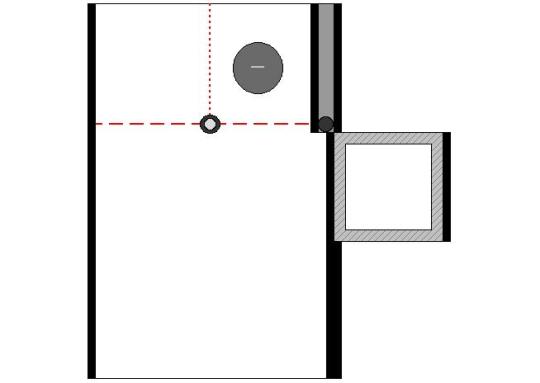

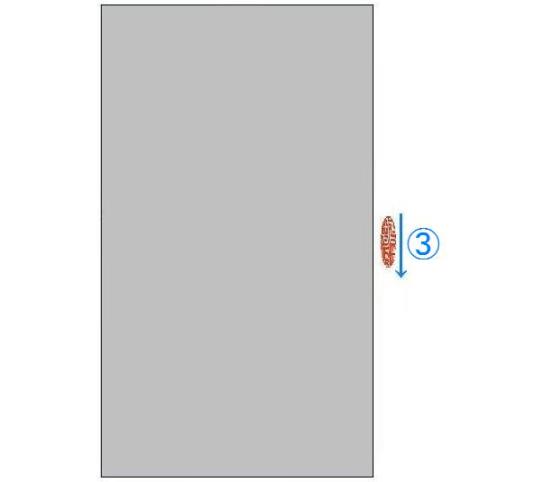

The traditional way of sealing the sa-tsū-bako, then, was for the tape to be pasted horizontally, so that it covered the place where the lid matched the body, as shown below.

The sealed sa-tsū-bako was displayed in the tearoom during the shoza (either in the toko, or on the tana)¹⁵. At the beginning of the goza, as the first step in the koicha-temae, the host would cut open the sa-tsū-bako, using a small knife (that was usually displayed on the tana beside the box).

First, the host made two cuts, as shown below.

Then the sa-tsū-bako was passed around so that the guests could inspect the box and the still-intact name-seal¹⁶. After it was returned, the host took up the knife again and cut through the name-seal, which allowed the box to be opened.

These three cuts of the sealing tape were referred to as fū no mi-katana [封ノ三刀]¹⁷.

After the box was cut open, the container of tea was taken out and placed in front of the mizusashi, and the lid of the box was then passed around (if it contained written details describing the tea that the box had contained), so that the guests could inspect that as well; after which the box was moved to the katte.

When Hideyoshi visited someone (such as Rikyū) for chanoyu, the tea was usually tea from one of Hideyoshi’s own jars that had been ground in his palace (under the watchful eyes of his personal guards)¹⁸. Thus, the inspection to make sure the seal had not been tempered with was always a part of the procedures. However, since Hideyoshi objected to the knife, an alternate way of opening the box was devised: a thread was glued to the back side of the paper tape before it was pasted over the box. Thus, once the paste was dried, the host only had to pull on the thread to tear through the paper tape, and so open the box without need for a knife¹⁹.

Kanshū oshō-sama had no good answer for how or why the way to paste the paper tape onto the sa-tsū-bako changed -- other than to speculate that doing so made it easier to open the box.

In the Nambō-ate no densho [南坊宛の傳書], there is a drawing of the way the kiji-tsurube is sealed with a paper tape. Rikyū’s drawing from that document is shown below. (The semi-circle at the top was supposed to represent the hole in the handle of the kiji-tsurube: the paper tape is passed through this hole, so that it can encircle the whole tsurube; the line down the front is the paper tape, while the tsurube is depicted from the side.)

Beginning with Furuta Sōshitsu (during the time when he was supposed to be overseeing the decimation of Sakai and its incorporation into the Japanese state), a knowledge of the documents preserved in the Shū-un-an began to spread throughout the tea communities of Ōsaka and Kyōto, and efforts were made by different people to access, and copy, part of this collection. Since these copies were usually made very quickly, they often contain errors -- and one of the most commonly seen errors is when drawings became disassociated from the text that describes them (for example, even Oribe’s copy of the above-cited densho is missing several of Rikyū's sketches, while one or two others are found in completely different places in Oribe’s copy).

Given the similarity between Rikyū's drawing of the kiji-tsurube sealed with a paper tape (left) and the sketch of the sa-tsū-bako sealed with a paper tape from Tachibana Jitsuzan’s personal notes, shown on the right (these were the notes taken with the Shū-un-an documents spread in front of him, which he subsequently edited and recopied into the notebooks that he presented to the Enkaku-ji), it seems at least plausible that, at some point, the earlier drawing had become orphaned from its text, and was then reinterpreted as being a sketch of the latter concept, thus giving rise to the idea that the sa-tsū-bako was supposed to be sealed with a tape passed around the box the same way one was passed around the kiji-tsurube²⁰.

The matter is complicated by the fact that Rikyū did not leave us any drawings of the way the sa-tsū-bako was supposed to be sealed²¹ (though, since this action would have been intuitive, making sketches would have been unnecessary: indeed, the sketch of the tsurube might have been desirable, at least in his mind, precisely because the tsurube does not need to be sealed as carefully as the sa-tsū-bako). Nevertheless, Kanshū oshō-sama’s explanation is convincing, especially in light of the Nampō Roku’s text (if we simply ignore the sketch).

_________________________

¹³Chaho [茶舗], which is a shop that sells sencha, matcha, and so forth, such as the famous house Ippodō [一保堂] (as opposed to a “teahouse”).

¹⁴This was told to me by Watanabe Kyōko-san, the owner/manager of Ippodō at that time.

¹⁵It is important to point out that, while sa-tsū-bako that hold two containers of tea are the best known today, in the sixteenth century (and continuing into the early Edo period), sa-tsū-bako were made in various sizes -- that held one, two, or three containers of tea, according to what the donor required.

The number three was selected as the upper limit because the large tea jars traditionally were packed with three kinds of tea leaves: hatsu-no-mukashi koicha [初昔濃茶] (produced from tea leaves picked between the 77th and 87th day of the Lunar year), ato-no-mukashi koicha [後昔濃茶] (made from leaves harvested between the 89th and 99th days of the year), and the lower quality leaves (made from an unspecified mixture of inferior leaves from both harvests) that were used as packing material (these leaves were also suitable for use as usucha [薄茶]).

During Rikyū's period, sa-tsū-bako holding a single container of matcha seem to have been most common (the idea of storing chaire in wooden boxes arose during this time when people recycled these boxes to protect their chaire when not in use -- since specially turned hikiya [挽家] were very costly, and so out of keeping with the idea of wabi, while reusing a box intended for another purpose agreed exactly with this kind of approach), while boxes holding two containers overwhelmingly became the sa-tsu-bako of choice during the Edo period, once it became the established custom to serve both koicha and usucha, using a different variety of tea for each, during the goza.

¹⁶Originally as a security precaution (to verify that the box had not been tampered with); later usually as a sort of status symbol -- that the host was in a position to receive a gift of tea from the esteemed sender.

¹⁷The way the sa-tsū-bako was cut open is, in fact, the same way that the paper tape sealing the lid of the cha-tsubo is cut open. This is completely logical, since both actions share a common purpose.

¹⁸Hideyoshi received the finest tea available each year. Thus, the tea available to anyone else would necessarily have been inferior (and, more commonly than not, markedly so).

Furthermore, since the beginning of chanoyu in Japan, in the early fifteenth century, all of the practitioners had belonged to the Ikkō-shū [一向宗], the Amidist sect of Buddhism that had been responsible for the overthrow of the Koryeo dynasty (using names that ended in -ami [-阿彌] was the way that followers of the Ikkō-shū identified themselves to each other). While the monumental bureaucracy of the Ashikaga family had served as a sort of safeguard, to people like Nobunaga and Hideyoshi there remained a perpetual fear of revolution at the hands of the followers of the Ikkō-shū (since power, in their cases, was still wholly concentrated in a single man, so that the assassination of that single man would necessarily precipitate political change). Unfortunately, it was impossible to have chanoyu without also granting access to his person to followers of this politically dangerous sect (while most followers of the Ikkō-shū seem to have been pacifists, there was a radicalized faction that congregated around the Ishiyama Hongan-ji [石山本願寺] in Ōsaka, which actively opposed both Nobunaga and Hideyoshi, which is why both of these military men went to war against that temple -- and why, once Hideyoshi prevailed, he razed the temple and used the land as the site for his Ōsaka castle; and later attempted to dilute the power of the Ikkō-shū by moving their headquarters to Kyōto, and then dividing the temple into two, in the hopes that the factions would become antagonistic to each other). Thus, while he deeply enjoyed chanoyu, Hideyoshi remained hyper-vigilant (to a point that bordered on paranoia) to the potential threat posed by his intimate association with the chajin of his day.

¹⁹Later, in the Edo period, more attractive (though technically less secure) methods of keeping the box closed appeared, using attractive silk ribbons attached to the box in different ways. This is where the different styles of himo on utensil boxes originated.

²⁰The idea was to protect the water drawn at dawn from contamination. The primary problem was that the half lids of the kiji-tsurube tend to warp (as the top side dries while the inner side continues to absorb more water vapor from within). The paper tape will not prevent warping, but it will keep the lid from flaring upward on the outer edge, leaving a large gap through which dust could easily enter, while also keeping pressure on the lid so that the warping will be minimized. The paper tape passes through the half-circular hole in the middle of the handle (this is where a rope was passed so that a pair of tsurube could be balanced on a shoulder pole for the trip from well to mizuya -- two tsurube of water being usually enough for most days).

²¹It is certainly possible that many of Rikyū’s densho were lost over the years, though the ones that Suzuki Keiichi did inspect (which is larger than the number of examples quoted in his Sen no Rikyū zen-shū [千利休全集]) seem to have been a representative selection of his writings. (Rikyū, as I mentioned during the translation of his densho, gives evidence of having been dyslectic. As a result, once he managed to produce a densho, he seems to have kept a copy in his archive, and then reused the text as often as possible, only changing certain minor details so that each version appeared as if it had been written specifically for his interlocutor. As the documents were supposed to be kept secret, there was little chance of his disciples comparing notes; as a result their thank-presents were usually quite lavish: these gifts played an important role in Rikyū’s restoration of his personal wealth, the foundation of which had been laid by the sale of the utensils that he brought back from the continent. As the fourth son of the family, he was basically forced to look after himself for the rest of his life, following their bankruptcy.)

1 note

·

View note

Photo

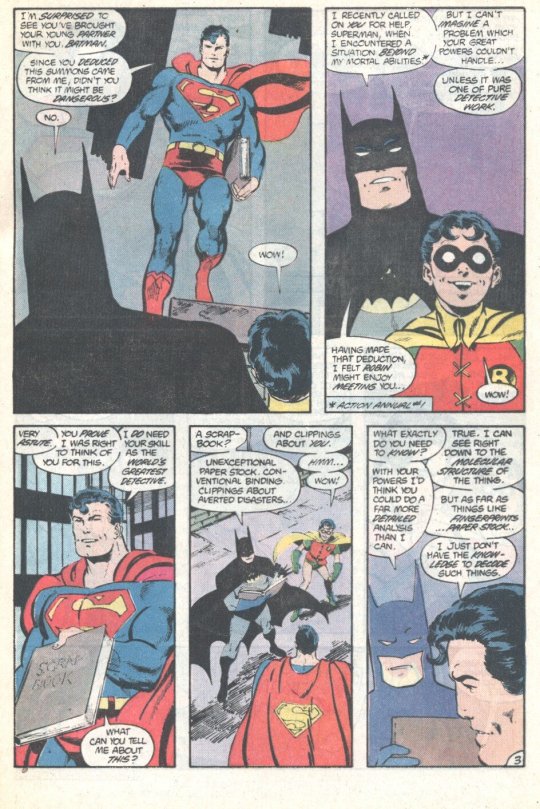

tea lessons お茶のお稽古 . . . お茶の先生方、先輩方、仲間達に感化され 茶箱を身の周りにあるもので作ってみました。 茶筅筒、茶巾筒は竹をきり、振出は少し小ぶりの茶入に桐の木を和紙で包んだ蓋で代用。その過程や実際に使用してみると沢山の ‘なるほど’ が出てきました。 このような機会をいただけたのも サンフランシスコのお茶の先生方、先輩方、仲間達 のお蔭です。そして現代のテクノロジー。 有り難うございます。 只今振出を試作しています。 もう少し作って次の窯焚きに追加します。 . i’ve got inspired by my tea teachers and tea mates and tried making a chabako set with the things found around here. used bamboos for the chasen zutsu & chakin zutsu. for a furidashi, i picked a small chaire and used a small paulownia piece wrapped with japanese washi paper for the lid instead. there have been lots of ‘I see’ moments during the making and using of those items. I really appreciate that my tea teachers and tea mates in San Francisco have given such opportunities and also feel thankful to the current technologies we have. I’ve also tried making some furidashi. will make some more and add them to the next firing. . . . #chanoyu #tea #chabako #furidashi #bizen #pottery #茶の湯 #茶箱 #振出 #備前 #やきもの https://www.instagram.com/p/CD6EF__DkXV/?igshid=x337gc44g9u1

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

. #茶箱 #chabako #一日集中稽古 #茶道 #chado #wayoftea #teaism #茶の湯 #chanoyu #抹茶 #matcha #greentea #japanesetea #tea #星窓 #星窓茶道 #東京 #tokyo #日本 #japan #zen #禅 #インスタ茶道部 #tea #wabisabi (Tokyo 東京, Japan) https://www.instagram.com/p/B3SBFVDFdkT/?igshid=ico06psohsap

#茶箱#chabako#一日集中稽古#茶道#chado#wayoftea#teaism#茶の湯#chanoyu#抹茶#matcha#greentea#japanesetea#tea#星窓#星窓茶道#東京#tokyo#日本#japan#zen#禅#インスタ茶道部#wabisabi

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Кто ещё убеждён, что магия чая надумана)? Развею последние сомнения) Рассказываю: Стоило нам вместе с чайным мастером Татьяной Глотовой провести чаепитие «Чабако Уно-Ханадате» Chabako Uno-Hanadate, как сразу температура воздуха с 35 упала до 25С) Ветерок. Прохлада. Наслаждаемся. 🍵 #чайнаяцеремония #матча #чай #чаепитие #мастеркласс #сладости #tea #love #tealover #teacup #teaceremony #tealife #teastyle #odessa #одесса #chado #matcha #matchalover #япония #chabako #urasenke #matchatea https://www.instagram.com/p/CRlUYObANi_/?utm_medium=tumblr

#чайнаяцеремония#матча#чай#чаепитие#мастеркласс#сладости#tea#love#tealover#teacup#teaceremony#tealife#teastyle#odessa#одесса#chado#matcha#matchalover#япония#chabako#urasenke#matchatea

0 notes

Photo

All’Orto per l’Aperiorto con una nuova amica abbiamo fatto Chabako per alcuni soci, nuovi e storici ❤️ Grazie ancora Alessandro per l’ospitalità e @mangiappone per i Bento 🍱. @lailacfirenze #lailac #aperiorto #bento #chabako #spaventapasseri #kimono #kimonoestivo #viadelte #maccha #teverde #cerimoniadelte #scandicci #mangiappone #cateringgiapponese #umeboshi #ortodellolmo https://www.instagram.com/p/CCVHepKFs0E/?igshid=68i2b1a4bc3l

#lailac#aperiorto#bento#chabako#spaventapasseri#kimono#kimonoestivo#viadelte#maccha#teverde#cerimoniadelte#scandicci#mangiappone#cateringgiapponese#umeboshi#ortodellolmo

0 notes

Text

36 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A LACQUER CHABAKO [TEA CEREMONY UTENSILS BOX]

EDO PERIOD (19TH CENTURY)

The rectangular box with angled corners, with the flush-fitting cover and an inner tray, the black lacquer ground decorated in gold and silver hiramaki-e [low relief lacquer], togidashi [sprinkled designs revealed by polishing], kirikane [cut out pieces of gold leaf] and gradational nashiji [sprinkled gold lacquer] with a pine tree, the fitted inner tray with a branch of persimmon in gold and red takamaki-e [high relief lacquer], the interior in sparse nashiji, fundame [dull gold lacquer ground] rims

16 cm. wide here

24 notes

·

View notes

Note

Kogitsunemaru wasn't really sure what to get for his mate, but when he walked past that traditional tea shop, he went inside and came out with a box, which he tried to wrap himself later. It was obvious he had wrapped it as he had small cuts on his fingers from the paper. The fox may seem smart and all, but he's clumsy with stuff like this. It was a Lacquer Chabako with flower design and the cups had the same design. "Merry Christmas Souji.." the fox told his mate as he handed the gift.

@howtolove-a-gentlefox

Souji had a gift, himself, a yukata that he found which would look quite handsome on his mate, but the box presented to him caught him off guard, smiling at the attempt to wrap, the small cuts on the other’s hands. He tried really hard...

The box was beautiful, the teapot and cups the same lovely design. “Kogi this is...” He looked up and grinned, taking the other’s hands and pressing a soft kiss to the alpha’s lips before some small pecks to the poor suffering hands. “I love it so much. Thank you...”

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 7 (29b): Tanaka Senshō’s Genpon [原本] Version of the Text of Entry 29.

29) When we speak about the chabako-temae [茶筥手前], there are two [different] kinds¹. If it is an occasion where [the kama is] hung up in the wilds, and the tea utensils are collected together [in a box, for transport to the site], [the box in which the utensils are carried] is sometimes referred to as a chabako [茶筥], and sometimes as a cha-bentō [茶辨當]².

This is all we shall say about the handling of the no-gake [野ガケ], [because] the details are difficult to describe³.

Now, as for the other, [this refers to the case where] tea is being sent to a certain person -- [that is,] the tea is sent to them so they may enjoy it⁴.

Or, to accompany the announcement that in the evening, or on that night, [the sender] is intending to pay a visit (or something of that sort), [the tea] is being sent⁵.

If the koicha-ire [濃茶入] is a treasured object, even so it may be included [in the box]⁶; and, [of course,] there is also the case where a brand-new chaire is put into [the box]: there is no problem with [the host's] either⁷. It would be better if usucha is put into something like a natsume or a nakatsugi⁸.

A high-quality box is made of paulownia wood, and it should be one that can accommodate two [containers of matcha]⁹. The lid should be a san-buta [サン蓋]¹⁰, and a himo should not be attached [to the box]¹¹.

By giving [the tape] a small twist, the seal[ing tape] is bound around the very center [of the box]¹². [One should] practice cutting the [ends of the] seal[ing tape] with three slices, as this is a secret¹³.

Generally speaking, [the box] is sealed by twisting [the ends of the paper sealing-tape] like this, with one end [cut] so that it resembles the point of a sword, while one end is straight¹⁴.

Depending on the size of the chaire, the box should be different¹⁵.

_________________________

◎ In this post we will look at Tanaka Senshō’s genpon [原本] version of entry 29, including the marginalia that were appended to this entry in said source.

¹Chabako temae to iu ni, ni-yō ari [茶筥手前ト云ニ、二樣アリ].

Chabako [茶筥] is a non-standard way of writing chabako [茶箱]. The rarely seen the kanji hako [筥]* appears to have been somewhat popular in certain tea circles during the Edo period.

__________

*While the kanji refers to a box-like container, it appears to have originally meant a tightly-woven round-shaped bamboo basket for holding rice (so something like a han-ki [飯器], the round lidded box in which additional rice is served during the kaiseki). As has been mentioned before, during the Edo period, with its culture of secrecy, it became fashionable to use antiquated kanji as one way to disguise ones meaning, or render texts unreadable to anyone other than those who were party to the secret meaning. (The attitude persists in modern-day chanoyu, though with the governmental insistence on keeping to the approved set of kanji, this mechanism has largely disappeared from contemporary tea literature.)

²No-gake no toki, cha-gu wo iri-kumi-taru wo mo, chabako to mo cha-bentō to mo iu [野ガケノ時、茶具ヲ入組タルヲモ、茶筥トモ茶辨當トモ云].

No-gake [野懸け] means to hang up (the kama) in nature (that is, in an uncultivated or undeveloped natural area).

Chabako to mo cha-bentō to mo iu [茶筥とも茶辨當とも云う] means “it may be called a chabako [tea box] or it may be called a cha-bentō [tea bentō].”

³Kore ha no-gake sabaki ni te sumu-koto nari, isai shirushi-gatashi [是ハ野ガケサバキニテスムコト也、委細記シガタシ].

The first part of the sentence (kore ha no-gake sabaki ni te sumu-koto nari, isai shirushi-gatashi [これは野懸け捌きにて濟むことなり]), which is all that is found in the other versions of this entry, means “this is all that needs to be said about the conduct of a no-gake (gathering).”

Isai shirushi-gatashi [委細記し難し] means “(because) the details are difficult to describe.”

Thus, according to this version, more is not said about the no-gake use of the chabako because it would be too hard to set everything down here.

⁴Ima ichi-yō ha, hito-no-kata [h]e cha wo okuru-toki, nagusami ni cha wo okuri-sōrō [今一樣ハ、人ノ方ヘ茶ヲ送ル時、ナグサミニ茶ヲ送リ候].

Hito-no-kata [h]e cha wo okuru-toki [人の方へ茶を送る時] means “when sending tea to someone....”

Nagusami ni cha wo okuri-sōrō [慰みに茶を送り候う] means “the tea is being sent so as to give pleasure (to that person).”

In other words, this seems to be qualifying* that the sending of the tea is not a commercial activity, but done, person to person, so that the other person can enjoy the tea.

___________

*It could, however, also be understood to be an admonition. That is, that when sending matcha to someone in this way, the sender should not be doing so in the expectation of receiving something in return (as a thank-gift).

⁵Arui ha kon-ban, arui ha kon-ya nado motte mairi mōsu-beku nado itte okuru-koto ari [或ハ今晩、或ハ今夜ナド以參可申ナド云テ送ルコトアリ].

Arui ha kon-ban, arui ha kon-ya nado motte mairi mōsu-beku...itte [或は今晩、或は今夜など以て參り申すべく...云って]: arui ha kon-ban [或は今晩] means perhaps this evening; arui ha kon-ya [或は今夜など] means perhaps tonight or other such times; motte [以て] means on account of, or because of; mairi mōsu-beku...itte [參り申すべく...云って] means (I) am saying that (I) am intending to visit....

Here, the gift of tea accompanies the announcement that the sender is planning to visit the recipient that evening, or night, or whenever.

In other words, the gift of tea (i.e., refreshments) is intended to soften the imposition (on the recipient’s time and resources) that the sender will be making, to be received and entertained.

⁶Koicha-ire ha hizō-no-mono ni mo iru [濃茶入ハ秘藏ノモノニモ入ル].

Koicha-ire ha hizo-no-mono ni mo [濃茶入は秘藏の物にも] means “even if the koicha-ire is a treasured piece....”

Iru [入る] means put in(to the sa-tsū-bako).

In the present context (where this sentence follows the one that indicates that the tea may be sent along with a message that the sender is intending to pay a visit to the recipient), the inclusion of one of the sender’s treasured chaire might be interpreted as a way of suggesting something like “let’s enjoy this tea together” -- since, obviously, this would not be the usual way for that person to be making a gift of the chaire to the recipient.

However, since that may not have been the intention* (in other words, the text has simply shifted its focus to the way to assemble the contents of the box, thus the author might not be thinking about sending the box to someone as a gift at all, but to the case where the host is using the gift tea he received from someone else during his own chakai), it might be appropriate to repeat something of the history of the sa-tsū-bako here, for clarity. From the fifteenth century† until the time of Rikyū, at least, the sa-tsū-bako contained only gift tea -- which could number up to three tea containers (since a cha-tsubo was traditionally packed with three kinds of tea leaves: hatsu-no-mukashi koicha [初昔濃茶]‡, ato-no-mukashi koicha [後昔濃茶]**, and the lower quality leaves that had been used as packing material, but which were still suitable to be used for usucha††), though often fewer (since this gift tea was usually what was left after the tea that had been ground for some special purpose had been used). Thus, since the early days, sa-tsū-bako had been made in three sizes -- to hold one, two, or three containers of gift tea.

During Hideyoshi’s time as de facto ruler of Japan, fresh matcha was ground every day, whether Hideyoshi was in residence or not, for the use of his household. This tea was used between early morning (the fires in the household were usually started at dawn) and around 10:00 PM (when the fires were traditionally removed). Any tea remaining after the fires were taken away could not be used (since fresh tea would be ground the next morning), and, because Hideyoshi’s personal tea-jars were filled with the finest tea leaves available, rather than discard this tea, Hideyoshi made it available for free to any of his subjects, for which one simply had to apply by having ones name put on the list. Distributing this left-over tea was one of the responsibilities of the sadō [茶頭] -- the eight officials in charge of Hideyoshi’s tea, and his tearooms -- and, at least in theory, they were supposed to send off the tea (apportioned into ko-natsume or chū-natsume) to the next name on the list (though, in practice, people often paid the sadō a substantial tip for moving their name to the top of the list -- and, because Rikyu seems to have remained indifferent unless the tip was very large, this resulted in complaints lodged against him by Imai Sōkyū). This system not unpredictably ground to a halt after Hideyoshi’s death in 1597.

The way that the host handled the sa-tsū-bako had become standardized during the late sixteenth century (primarily based on Furuta Sōshitsu’s personal inclinations), and, once peace had been restored and the place of the machi-shū affiliated with Sōtan recognized, the idea of the sa-tsū-bako (and its special rules and conventions) was revived. And the thriving tea business (the result of Hideyoshi’s encouragement for the establishment of tea plantations all over the country) meant that tea was now more readily available than ever. Furthermore, the intense competition eventually resulted in certain shops offering to grind the matcha for their customers (for free -- which is actually still the case today). Thus matcha could be procured quite easily, easily enough that it became a popular gift‡‡.

Since commercially purchased matcha was generally given to the customer in the shop’s proprietary packaging (either a lacquered container resembling a natsume or nakatsugi, an inexpensive ceramic chaire with ivory lid, usually with the details of the shop stamped onto the side in place of the potter’s seal, or, as the Edo period deepened, and influence from the continent increased, metal cans shaped like a nakatsugi), it seems that the idea of transferring the matcha into one of the host’s own tea containers arose, and this seems to have been the state of things at the time when this entry was modified (to reflect Sen family-approved practices). Thus, when the sa-tsū-bako (which was now provided by the host) was used, even though the tea containers were the property of the host, the tea they contained was gift tea. It was in this context that the chaire contained the koicha-quality tea, while the natsume (or other lacquered container) was filled with the usucha-quality matcha; and it was in this context that the question of whether or not a treasured chaire may be used as the chaire came to be discussed.

Later in the Edo period, this idea evolved further, so that the chaire that was placed inside the sa-tsū-bako contained matcha that had been prepared by the host (meaning he purchased it from a shop for the occasion), while the second container (usually a natsume) contained the tea that the host had received as a gift (often from one of the guests). Whether the natsume contained usucha-quality tea, or tea suitably to be served as koicha, was now an open question (with public opinion generally falling on the side that considered it impolite to give only usucha-quality tea as a gift; thus, if there was only one kind of gift tea, it should be of the highest quality possible, and so should be served as koicha). This generally remains the case today, so the modern version of the sa-tsū-bako temae involves the service of successive bowls of koicha (with no thought given to the possibility of including usucha at all***).

___________

*Though Tanaka asserts that the source of this text was the genpon [原本], which should mean it was part of the original Shū-un-an cache or documents, we must question whether that was, indeed, the case -- since it appears to have been an edited version of the text quoted by Shibayama Fugen. Thus, there may be no intentional, or intended, connection between this sentence and the one that precedes it in this version of the entry.

†At the time when a cha-tsubo was cut open for the first time (since it was refilled), Ashikaga Yoshimasa is said to have been in the habit of sharing some of the tea from the first grinding with those among his retainers who were fond of chanoyu. It is said that the sa-tsū-bako was first used at that time.

‡Hatsu-no-mukashi koicha [初昔濃茶] was produced from leaves that had been picked between the 77th and 87th days of the Lunar Year.

Since the Lunar Year is not in sync with the Solar Year, there could be up to a month’s difference between when the leaves were picked from year to year. Since the tea was harvested during the season when cloud-cover was deepening (that is, as the year advanced the number of sunny days versus overcast days was decreasing), the later the leaves were picked meant the less direct sunlight (and correspondingly higher humidity) to which they had been exposed to while alive. Because the leaves picked over a span of ten days were mixed, there was usually a distinct difference in taste between the earlier and later pickings. (Modern matcha producers, particularly in Uji, cover their tea fields with shade-cloth, and mist the plants at 15 minute intervals, meaning the modern product tends to be, if anything, more bland. Traditional hatsu-no-mukashi tea was rather sharp, while ato-no-mukashi tended to have a milder, more subtle flavor.)

**Ato-no-mukashi koicha [後昔濃茶] came from leaves that had been picked between the 89th and 99th days of the Lunar Year.

††This tea had been picked and processed together with the leaves that were ultimately used for koicha. This fraction was separated only later, because the leaves were subjectively deemed inferior (on account of leaf-size, leaf-color, integrity, and weight -- the processed leaves were tossed up into the air and winnowed with a fan, and the leaves that blew away were rejected from being used for koicha). Since it would be used for packing material (to act as a buffer so that moisture could not infiltrate the high-quality leaves, which were segregated into paper packets) the lower-quality leaves from the two pickings were mixed. Nevertheless, they had been picked and processed in exactly the same way as the high-quality leaves, so they were not completely unworthy of being appreciated.

‡‡As alluded to in this version of the entry (cf. footnote 5), where the gift of matcha was considered an appropriate accompaniment to a message indicating that a guest wished to pay a visit.

***At least in theory, serving the gift tea as usucha would be done in the same way -- just that individual bowls of usucha would be prepared from the second tea in the usual way, rather than a single bowl of koicha. (Nevertheless, since such flexibility has been discouraged since the early 20th century, most modern tea people would be nonplussed to find that the second container of tea in the sa-tsū-bako was supposed to be served as usucha, since the sa-tsū-bako temae is always taught as the service of two varieties of koicha)

⁷Shin-chaire ni iru-koto mo ari, izure ni te mo kurushi-karazu [新茶入ニ入ルコトモアリ、イヅレニテモ不苦].

Shin-chaire [新茶入] means a new chaire, a newly-made chaire*. The expression might also be intended to imply that the chaire is being used for the very first time on this occasion.

Izure ni te mo kurushi-karazu [何れにても苦しからず] means “either way, it does not matter†.”

__________

*In Rikyū’s period, and even into the early Edo period, newly-made pieces were considered easily replaceable, expendable, and so could not generally be regarded to be treasured objects.

With the great expansion in the number of people participating in chanoyu that occurred during the early Edo period, coupled with the need for all of those people to be able to serve tea (the rule was still that the host should always use the “best” utensils to serve his guests as possible), the collection of meibutsu tea utensils that had passed through the decades of warfare unscathed proved vastly inadequate; thus a new class of “suitable” utensils had to be created. First, overlooked pieces from the previous century were added (this was one of Kobori Masakazu’s [小堀政一; 1579 ~ 1647] jobs when he was ordered to organize the meibutsu utensils, at which time he created the category of chū-kō meibutsu [中興名物] in an effort to expand the pool of available treasures to satisfy the demands of at least the upper classes), but eventually specific craftsmen had to be designated, whose products would be deemed “suitable” when nothing better was available.

It was at this time, too, that the idea of hako-gaki [箱書] and iemoto-gonomi [家元好み] -- both of which were intended to elevate ordinary pieces to an acceptable standard of quality -- made their appearance.

†Kurushi-karazu [苦しからず] means things like “it doesn’t matter,” “it is not a problem,” “there is no difficulty with doing that,” and so forth. The meaning is related to something that the reader might imagine is a theoretical violation of the rules, which this expression is intended to lay to rest (rather than referring to something that is physically challenging to accomplish).

In this case, the author is saying that enclosing a treasured chaire, or a brand-new chaire (these two possibilities represent the opposite extremes, in so far as the host’s personal collection of utensils is concerned), either is just as acceptable as using the host’s “ordinary” chaire (one that is neither his great treasure, nor one that was just purchased and is being used for the first time on this occasion).

⁸Usucha ha natsume・nakatsugi nado ni ire-beshi [ウス茶ハナツメ・中次ナドニ入ベシ].

Natsume・nakatsugi nado [ナツメ・中次など] is referring to lacquered containers. While a nakatsugi could fit in an ordinary futatsu-ire sa-tsū-bako, it could not be wrapped by a modern-day temae-fukusa (which was based on the size of the purple furoshiki designed by Rikyū* for wrapping a container of gift tea†).

Again, this reflects the evolving interpretation put forth by the machi-shū followers of Sōtan, and has nothing to do with Rikyū or the chanoyu of his period‡.

During the Edo period the rule was articulated that the koicha-ire was supposed to be a ceramic piece, and the usucha-ire was supposed to be a lacquered piece (thus forcing the host to buy at least one example of each) -- and this remains the modern schools’ teaching even today.

__________

*While the purple color of this wrapping cloth was determined by Rikyū, the formula for calculating its size had been developed long before (though in earlier times imported Chinese donsu was used for these furoshiki, rather than Japanese-made purple-dyed silk).

Because the size of this cloth had more or less been fixed by his day, and because this size did not permit the wrapping of a nakatsugi, Jōō created an alternate version of the nakatsugi that had the corners of both the lid and the body beveled to fit. This version of the nakatsugi is known as a fubuki [吹雪].

The reason for his concern over the nakatsugi was because this kind of container provided the best hope of protecting the flavor of the tea, on account of the way the lid fits onto the body. A high-quality nakatsugi was secure enough that it did not need a covering cloth to keep the tea fresh; by contrast, something like a natsume needed to be wrapped in a cloth, in order to press the lid tightly against the body, thus preventing the volatile elements from escaping: this was always the most important consideration, and why chaire were provided with ivory lids backed by gilded paper, and then tied in shifuku (the gilded paper became air-tight when the slightly malleable ivory was pressed against the mouth of the chaire by the pressure of the shifuku, the paper between the ivory and the gold foil allowing the lid to meld into the slight irregularities of the mouth of the chaire). The shifuku, or purple furoshiki, was not there to protect the chaire, but to protect the tea. That was its only purpose.

Of course, in the early days the lids were always custom made, so the fit was good. In the modern day lids are mass produced, and fitting is done based on the outer diameter. As a result, the “sealing” potential of the lid might not always ba apparent.

†This covering was first used as a fukusa by Furuta Sōshitsu.

According to the story, Oribe was hosting a chakai when a container of gift tea arrived (the sending off of this tea, which was from one of Hideyoshi’s tea-jars, had been facilitated by Rikyū). Deciding that he would like to share the tea with his guests (since it would never be any fresher than at that moment), he brought the sa-tsū-bako into the room. But since he did not have a new fukusa (the rule was that when a different kind of tea was going to be served, the fukusa and chakin -- at the very least -- had to be changed). So, when he had taken the gift tea out of the sa-tsū-bako, Oribe got the idea to use the little furoshiki in which the tea container had been wrapped as a temae-fukusa.

At a later time, he told Rikyū what he had done; and, after giving the matter some thought, Rikyū approved of this idea -- and when serving tea from a natsume that had been tied in a furoshiki in this way, Rikyū also did the same thing. The size of the modern temae-fukusa, then, was determined based on the size of furoshiki needed to tie up a small natsume.

‡In Rikyū’s day, the first consideration was the size of the tea container, especially in the small room, since it was supposed to be no larger than necessary to serve the number of guests who had been invited (this would help to prevent the waste of matcha, the leavings of which could not be reused on another occasion; meanwhile the classical rule was that tea container should always be filled fully, since a large amount of empty space would allow the volatile components of flavor and aroma to evaporate into the air, thereby negatively impacting the taste of the tea). After recognizing the size of tea container necessary, the host was supposed to use the best container of that type that he owned when serving tea to his guests. If the best container was a lacquered piece (usually decorated with gold or colored lacquer), then that is what he used; if it was a ceramic piece, then that is what he used. There could not be a rule, because the availability of utensils naturally varied from person to person.

Plain black-lacquered natsume were made as storage containers, and they came in several sizes, since the size used depended on how much tea was left: when the host (or his assistant) ground the matcha in the early morning, the tea container that he intended to use during that day’s chakai was filled first. Then any matcha that remained was put into a black natsume and kept in a cool place until later (for drinking by members of the household -- since usucha was still considered ordinary drinking tea at that time).

If an unexpected guest arrived later in the day, this stored matcha would be used (since tea was only supposed to be ground in the early morning). But since transferring the tea into a chaire would expose it to the air (and so degrade the taste), Rikyū took the black storage container and used that during the temae. This was not an aesthetic choice on his part, but done because, in the small room, the taste of the koicha was the most important element of the chakai.

⁹Jō-bako ha kiri-no-ki ni te futatsu-ire ni sasu [上筥ハ桐木ニテ二ツ入ニサス].

Jō-bako [上筥 = 上箱]* means a high-quality box.

Kiri-no-ki ni te futatsu-ire sasu [桐木にて二つ入れ指す] means “this indicates (sasu [指す]) that (the box) is made from paulownia wood (kiri-no-ki ni te [桐木にて]), and accommodates two containers (futatsu-ire [二つ入れ]) of matcha.

__________

*Some commentators interpret this word to be uwa-bako [上箱], which would mean an outer box (since, at least originally, the gift or gifts of matcha were, in turn, put in lacquered containers, which are also a type of box).

¹⁰Futa ha san-buta nari [蓋ハサン蓋ナリ].

San-buta [棧蓋] means the lid consists of a single flat piece of wood, to the underside of which two san [棧] (crosspieces) are attached (these can be seen in the photo, which shows the underside of this kind of lid).

The crosspieces are attached so that they fit inside the mouth of the box*, so they will keep the lid in place without needing to be secured (by a sealing tape, or a himo, or something of that sort).

__________

*The distance between the san and the edge of the lid is the same as the thickness of the walls of the box. The fit is usually fairly tight, in the case of a high-quality box, so that the lid will not fall off easily.

¹¹Himo wa tsukazu [緒ハ不付].

Tsukazu [不付 = 付かず] means not attached.

The box is kept closed by the sealing tape that is bound around it, rather than by a himo (such as is found on tea-utensil boxes).

¹²Ko-yori ni te, mannaka kukurite fū wo tsukuru [小ヨリニテ、眞中クヽリテ封ヲツクル].

The expression ko-yori ni te [小よりにて] is difficult to interpret without further qualification. (This is clarified in the statement that follows the drawing.)

Mannaka kukurite fu wo tsukeru* [眞ん中括りて封を付ける] means the seal is attached by binding it around the very middle (of the box).

___________

*Tsukeru [付ける] is the modern equivalent of the classical verb tsukuru [付くる].

¹³Ji-fū no mi-katana to iu narai hiji nari [自封ノ三刀ト云習秘事ナリ].

This means that the host should practice cutting the ends of the tape using three strokes of his knife (to produce the effect described in the previous footnote).

While mi-katana [三刀] originally referred to the way that the sealing tape was cut off, in the presence of the guests, at the beginning of the koicha-temae, Hideyoshi's objection to the presence of the knife (which was naturally needed to cut through the tape) meant that this practice was discontinued (at least on occasions when he was present)*.

The Edo period machi-shū, remembering the phrase mi-katana, but not knowing to what it referred, interpreted it in the way explained here.

__________

*And it seems that the chance to receive tea leftover matcha from the ruler's household also ended upon Hideyoshi’s death. Thus, all that survived, was the memory that the sa-tsū-bako had been sealed with a paper tape, and that the paper tape was somehow associated with three cuts of a knife.

¹⁴Oyoso kaku-no-gotoki koyori fūjite ippō ha ken-saki, ippō wa ichimonji nari [凡如此小ヨリ封ジテ一方ハ劍先、一方ハ一文字也].

Oyoso kaku-no-gotoki [凡そ此のごとき] means “in roughly the manner shown [in the sketch*]

Koyori fūjite [小縒り封じて] means to seal (the tape) by giving it a small twist. The exact intention is not completely clear†.

Ippō ha ken-saki, ippō ha ichimonji nari [一方は劍先、一方は一文字なり]: this is referring to the two ends of the sealing tape. One end is cut off straight (ichimonji [一文字]), with a single slash of the knife; while the other end is cut into a point, with two slashes, so it resembles the tip of the blade of a sword (ken-saki [劍先]).

The way the ends of the tape are supposed to be cut -- with one cut straight (with a single slice of the knife), and the other pointed (requiring two slices) is interpreted to be the meaning of mi-katana [三刀] (see the previous footnote).

__________

*I have redrawn the sketch because the illustration was reproduced at too small a scale to see what is intended: the end of the paper seal on the left is pointed, while that on the right was cut off straight.

†That is, whether the two ends were literally twisted together, one was twisted around the other, or even the two were tied with a simple knot), but, in any case, the two ends of the tape were supposed to be free and visible.

This is different from what was done in Rikyū’s period, where the tape was actually pasted to the box (so it could not be removed without cutting the tape).

Presumably the reason the tape was not pasted to the box in the present case was because, if that were done, the box could not be reused later. Since it is specified that the box was supposed to be of high quality, it would consequently have been quite expensive -- so throwing it away after a single use would have been wasteful (and so distasteful, at least to chajin of the merchant class).

¹⁵Chaire dai-shō ni yorite hako no dai-shō onaji-karazu [茶入大小ニヨリテ筥ノ大小不同].

Chaire dai-shō ni yorite [茶入大小によりて] means depending on the size of the chaire....

Hako no dai-shō onaji-karazu [筥の大小同からず] means the size of the box is not the same.

In other words, depending on the size of the chaire that will be enclosed in the box, the size of the box needs to be different.

Today the sa-tsū-bako has been standardized, supposedly based on the futatsu-iri sa-tsū-bako [二つ入茶通箱] purportedly used by Rikyū*. And though it is still the rule that the chaire (containing the host’s matcha) is supposed to be enclosed in the box together with the container of gift tea (usually a natsume -- either tied in a fukusa or in a shifuku, depending on the preferences of the school with which the host is affiliated), this not infrequently means that the host has to rework his tori-awase at the last minute†, so he can actually put his chaire of tea into the box‡.

__________

*Though there is no evidence surviving from his period that Rikyū actually used a box with a yarō-buta [藥籠蓋] -- and the fact that one or more sa-tsū-bako would have been dispatched from Hideyoshi’s residence every day (which would just be thrown away after they were opened), tends to argue against the use of a box with an elaborate lid.

Furthermore, the insistence that the box should have a san-buta [棧蓋], in every version of this text, would seem to impute a degree of historical validity to this counter-argument.

The purpose of a yarō-buta [藥籠蓋] was to prevent medicinal herbs, that would be boiled at home, from becoming contaminated with dust while being carried from the shop. And that is logical, since the portions of the herbs were wrapped in paper and then put into the box. But in the case of a sa-tsū-bako, the matcha was placed in lacquered tea containers (usually natsume or fubuki) that usually were made with yarō-buta, and these were tied in individual furoshiki made from new cloth (that was free of lint) -- the purpose of which was to press the lid tightly against the body of the tea container, so that the tea would be completely insulated from any contact with what was outside -- before the containers were put into the box. Thus the question of contamination would seem to be irrelevant (since even if dust somehow got into the box, the furoshiki and the yarō-buta of the lacquered tea containers would prevent its getting into the tea).

†Since very few chaire, of the sort that have been preferred since the Edo period, will actually fit into the box -- they are usually too tall.

‡The necessity of dumping the tea from one chaire into another would have shocked the chajin of Rikyū’s generation, who considered that each time the tea was exposed to the air, its quality decreased. Unfortunately, modern-day chanoyu is not especially concerned about the tea -- koicha (especially) is viewed as something that has to be endured, in order to have the chance to enjoy the more pleasurable elements of the gathering: the delicious meal, the kashi, and the chance to appreciate rare (and costly) utensils.

==============================================

❖ Appendix II: the Way to Handle a Ni-shu-iri Chabako [二種入茶筥]¹⁶.

○ The way to handle a chabako that holds two varieties [of matcha]: after the koicha-ire has been taken out, the usucha-ire is still [in the box]¹⁷. In the sukiya, after the [koi]cha-ire has been brought out, the usucha-ire is also lifted out to the same place [on the mat]¹⁸.

At this time that [paper] seal[ing tape] should be cleaned away, so the seal[ing tape] is placed inside the box, and [the box] is lifted into the katte¹⁹.

Then, when [the service of] koicha has been finished, thereupon, if a mizusashi was placed [on the utensil mat], water is added [to the kama], and then usucha should be [served]²⁰. Because things will be done in this way, after the guests have finished looking at the koicha-ire, it is appropriate for it to be placed on the kagi-datami, approximately midway between the ro and the wall of the katte²¹.

When [the host is using] a fukuro-dana, a kyū-dai, or something like that, when the usucha-ire is taken out as [described] before, it should be raised up onto the shelf²² -- in the case of the kyū-dai, it should be placed on the “right seat²³.”

In general, during an ordinary temae, when the koicha-ire is returned, the teishu enters the katte [taking the chaire with him], and then closes the shōji²⁴. However, when the chaire is brought back to the utensil mat, depending on [the way that the host feels it is appropriate to handle that] chaire, it might be placed in the very center of the mat as an hitotsu-mono (and remain there until the end of the gathering) -- or else, if it is an ordinary chaire, it would be placed so that it overlaps the very center by one-third²⁵.

Or again, depending on the host, while [the guests] are looking at the chaire, there are people who open the shōji and speak with [the guests]²⁶.

Perhaps on other occasions, when deciding about usucha, there is the possibility of its being carried out [from the mizuya], or something of that sort²⁷. But in any such case, if there is something that prevents [the host] from [placing the chaire on] the utensil mat, naturally it should be returned to the kagi-datami²⁸.

_________________________