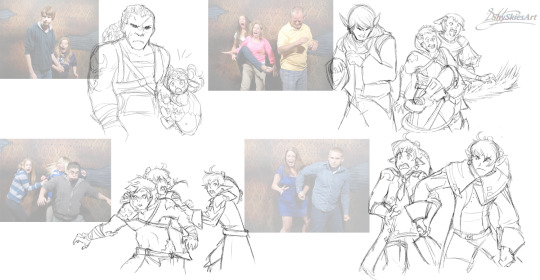

#been kind of a struggle to draw recently but i did manage to crank out some fun doodles at the eleventh hour at least

Text

all else fails, haunted house scare redraws

#been kind of a struggle to draw recently but i did manage to crank out some fun doodles at the eleventh hour at least#shoutout to orion for suggesting estinian for the laughing guy#it is extremely on point#you can probably tell which ones i used references for sdjfjkdsjkffs#'wait isnt that ARR and ShB hallima with SB twins?' yeah dont worry about it#no continuity only funnee#flight's making things again#ff14#ffXIV#holiday spirit

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Choices

Choices: A Iron Man Fanfic

Buy me a coffee with Ko-fi

Word Count: 2548

Pairing: Tony Stark x F!Reader

Warnings: Angst, Hurt no Comfort, Death of a Major Character

Synopsis: When the Earth is under threat the team faces a choice that no one wants to make.

Choices

You had never meant to fall in love with Tony Stark. You had definitely never meant to cause him pain. The level he feels right now was excruciating and while you hold him and stroke his hair whispering that it will be alright, everything will be fine, while Clint, Steve, and Natasha refuse to make eye contact with either of you, you wonder if there is any choice you made that could have ended differently. Where you got to have a life where you both got to lead it and be happy.

It had started so long ago. You were a small child, no more than six and it had called to you. Not that you remembered until recently. Not that you could have resisted then anyway. It was stronger than you and it wanted an owner. No one questioned the ring when you brought it home. You started sleeping with it under your pillow. Somehow, unless you looked directly at it, you never remembered that it existed.

Your powers had started manifesting a few years later. Very small and imperceptible at first. Plants in your house never withered or died despite your parents sometimes forgetting to water them. People found themselves feeling just generally happier to be around you. As time went on they grew. People who were having trouble conceiving found themselves pregnant within a few weeks of coming in contact with you. Flowers turned toward you like you were the sun.

By the time Tony Stark stood in front of the press and announced he was Iron Man you could heal any affliction. It took a lot of energy so curing word disease was not ever an option. On the occasions you’d cured terminal cases, they’d almost taken you in their place and it had taken weeks to recover. You did what you could while attempting to keep your anonymity. You wore the ring on a chain around your neck. No one ever asked about it. If they had it would have surprised you that it was even there.

By the time you came and stood in the lobby of the Avengers compound telling them you needed to speak to one of the Avengers, you could create new life from a few cells. Nothing big, but a leaf could be turned into a butterfly and while you felt tired after you did it, it didn’t need a long recovery time.

It had been Tony that had come to see what you wanted. He was dismissive, expecting that you were yet another crank coming to be an Avenger when they had no particular skills. When you brought one of the plants on the lobby back from the brink of death, he showed you to a room.

You took to the Avengers quite naturally. They took to you too. That was to be expected. Most people did. It was in your power set. Soon you were one of the team. You trained with them. You went on missions. Your powers grew. They gave you the call sign Gaia.

Maybe if you’d stayed away from the Avengers they wouldn’t be feeling this kind of pain right now. Maybe Tony’s heart wouldn’t be so broken.

The relationship with Tony had been unexpected. He sought you out a lot. All the Avengers did to some extent. They were all broken in their own ways, and being in your presence made them feel a little more whole. Tony was different though. It wasn’t just that. He connected to the part of you that wasn’t the powers. You enjoyed his snark. He made you happy in a way no one had. He felt safe to be vulnerable with you.

The day you had healed him, repairing the weakening of his heart muscles and the ventricles and aorta from the shrapnel and subsequent poisoning he received from the arc reactor housed in his chest, and the nerve damage in his left arm, the look of pure bliss on his face was sublime. The day he leaned in to kiss you and you had bridged the gap, your lips touching together and caressing, the feeling you had mirrored how he looked when you’d healed him.

Maybe if you hadn’t returned the kiss he’d be able to see that this was the only way.

Yesterday had started like any other. You woke octopused around him with his face buried in your neck. You’d let him sleep until he woke on his own. He’d drunk coffee and a smoothie while you had pancakes. Then the world had started to fall apart.

The attack had come from space. You, Clint, Tony, Steve, and Natasha had stayed on Earth, helping to protect it from the ground. There were others around who did the same. Well known heroes, such as the Black Panther, Spider-Man, and Ant-Man. Lesser known ones such as the hero of Harlem and the Devil of Hell’s kitchen.

The rest had gone to space to fight it directly. Only the fight was useless. They were winning. People were falling. They weren’t here to conquer they were here to destroy.

You took the ring from around your neck and you slipped it on your finger.

You’re not even sure why you do it. You aren’t even aware you are until it’s on your finger and you feel the crushing weight of another, pressing down on you and forcing you out of your own body. You latch on, trying to keep control but it’s too powerful. No, she’s too powerful. You know it is a she, just like you know your own gender.

The air crackles around you and your eyes glow purple. She draws in the very atoms changing the catsuit you’re wearing into flowing robes. The others all stop and turn to look at you.

“That is very impressive, dear. But now is not a time for a costume change.” Tony says hovering in front of your form in the Iron Man suit.

“What the hell was that?” Natasha asks, looking you over. “You’ve never done anything like that before.”

“I am sorry, friends and lover of the one you call Gaia.” The being answers, using your voice. “I do not mean to alarm you, and I never meant for this to happen, but your planet and your friends are in peril. If I do not step in, this is the end for all of you.”

The faceplate on the Iron Man suit opens and Tony looks at you with his head cocked to the side. “Okay, honey. That’s a very funny joke, but the timing is terrible.”

“Please forgive me. She is still here.” She pauses for a second as you grapple for control. “Darling, I know. I know it’s scary. I never meant for this to be the way it is.” She says out loud but you know she is addressing you.

“Who are you?” Steve asks.

The being lands gently in front of Steve. “I am ancient. There are no words in your lexicon for me. Goddess perhaps? But that is not quite right. Mother? I’m not sure. Just know I am not here to hurt you.”

“What have you done with our friend?” Steve asks.

“She is still here. Holding on. She fights. She always had such spirit. That’s why I chose her.” She answers.

“Let her go,” Tony growls, raising his repulsor and aiming it at your body. You grapple again and it feels like a physical weight is pushing down on the very essence of who you are.

She laughs. “Oh, my sweet man. I know you love her. It’s why she fights. But you can’t win against me, and I don’t wish you harm anyway. I do this out of necessity.”

“Why don’t you tell us what you want?” Steve asks squaring his shoulders.

“I have looked into the future and this only ends one of two ways. First, this planet is ripped asunder and nothing survives. Your friends in space are less fortunate. They live years being tortured and experimented on until their organs fail and they die in agony.” She answers.

“And the other?” Natasha asks.

“The other is I take this vessel. I remove the threat and I move on from this world. But your friend will die. I must remove the host to claim the vessel to truly have access to my full powers.” She explains. You start to struggle. You manage to take control for a moment and you try to remove the ring, but she takes control before you can even get your hands together. “Oh my most precious one, I know. This is hard. You always had such fight. I admire you for it.” She says to you.

“Listen to me, don’t you stop fighting. Keep fighting her, honey.” Tony says.

Clint raises his bow and just lets an arrow loose at you, aimed for your head. Her eyes flare purple and the atoms from the arrow pass easily between the atoms that make your body and it lands in the ground behind you.

“I am not your enemy here. Please.” She begs. “I have been molding her to fit me her whole life. I used to travel the universe creating. Creating words and life. Then one day a being of death trapped me in a ring. She wanted me dead, but my kind are eternal, so captivity was the only answer. My intention was to let her live it. When death came for her and her light extinguished I was to take the vessel then. Not before. But if these creatures who are so set on destruction win, and they will, it won’t just be her life, it will be everyone on this planet. And everyone on the next. And the next and the next. Until there is nothing left.”

As she speaks you see the future as she does and you realize what’s at stake here. You start to relax and give in to her. Letting her snuff you out. “No, my sweet. Not yet. They need to choose too. They have to understand.” She says.

“Don’t you give in. Don’t you do it. Fight her.” Tony barks at you.

“Tony, I think you need to be reasonable here. We all love her…” Steve says, calmly.

“No, that’s not how we do things. We don’t just trade one of us out. That’s not the answer.” Tony snarls.

“You would choose that you all die? That is the choice you make. No one, for a brief moment more with her?” She asks, floating up in the air and hovering in front of Tony.

“There’s got to be another way. We’re heroes. There’s always another way.” Tony says, almost pleading with her. The desperation drips from his voice.

A loud explosion rattles the ground and she looks up. “We’re running out of time. The decision needs to be made.” She says.

“Why can’t you just borrow her body? Get rid of them and give her back. Return to the original plan?” Steve asks.

She shakes your head. “I wish that I could. I do, truly. But I can only access a small percentage of my power while she still shares the vessel.”

“Stop calling her a vessel!” Tony shouts. “She is a person. She is better than you. Better than all of us.”

“I know that. She is. But she is not nearly as strong. If she were I would let her take care of it.” She explains.

You push the thought to her to let you speak to him. Just give you enough control to say goodbye. She nods. “She wishes to speak to you.” She says and touches back down to Earth. You feel the control return to you, but her essence is still there pressing on you.

“Tony.” You say softly.

He lands on the ground in front of you and you put your hands on his cheeks. “Please don’t do this. What will I do without you?” He pleads.

“You’ll go on. Like you always do. That’s what you do, Tony. You lose people and you go on.” You say, your thumbs stroking his cheeks.

The iron suit opens and he collapses out of it into your waiting arms. You hold him stroking his hair, looking at the others as they refuse to meet your eyes. “I love you, Tony. I want a life with you. The whole thing. Marriage, children. Grandchildren. All of it. But it wasn’t meant for us. This is the end of the road for me. But you have to keep going.”

“I can’t. I can’t.” He says, desperately. “Please. I love you.” It’s the first time you’ve heard the words from him and they’re like a dagger to the heart.

“I love you too. Please always remember that. I do. I have to go now. It will be okay. You will be okay.” You say and give yourself to her.

She takes control again and presses a kiss to Tony’s brow. He crumples to the ground staring up at you. “This is a terrible choice, but it is the right one. She still is here if you wish to say one last thing before she is gone.”

“She knows we love her, doesn’t she?” Clint says, tears running down his cheeks.

“Yes, she knows. She loves you all too.” She answers. “Goodbye, my love. You have made a great sacrifice today.” She says to you.

You feel pressure on you, then warmth, then nothing. She takes your form and floats up into the sky, plasma courses from her body, making the air crackle and boom. She looks out and sees everything and starts to rearrange it. The damage the aliens have caused is undone, she brings your friends back to Earth and they stand looking up not sure what just happened. Finally holding her arms out and her hands up, a beam of light pours from her and the crafts and everything on them ceases to be. They are torn apart atom from atom and those atoms are returned to the universe.

She lands down amongst the group. Most of them are confused. Unaware of what has happened. The rest are crying when normally this would be a celebration. Another threat driven back.

She approaches Natasha. “I shall go. Having me here will only cause you pain, but I wanted you to have the gift of choice.” She says putting her hand on Natasha’s stomach. Her eyes glow as she heals the damage to Natasha’s womb that was caused in the Red Room.

Natasha stares at her for a minute and wipes her eyes. “Thank you.” She whispers.

“There is one last thing. I don’t know if you are aware, but she is with child.” She says.

Tony looks up, terrified. “No. No… no, no, no.”

“You do not wish to keep it?” She asks.

“I - I do. I want it.” Tony says.

She approaches Tony and strokes his hair. “I can return with the child when it is born. Or if you have a host who wishes to bear the child I can transfer it.”

Tony looks around wildly. Not sure what the answer he has is. Not wanting to miss out on the pregnancy but not knowing what other choice he has.

“I’ll do it,” Natasha says. “I’ll carry it.”

She returns to Natasha’s side, touches her own stomach and touches Natasha’s. “So be it.” She says as they both glow. As the light fades, she looks at the group. “I wish you well, Avengers. Know she loved you so I do love you. If you need me, just call to Gaia like you always have.”

And she’s gone. Her form shimmering and disappearing. Tony breaks down into tears and his friends gather around, ready to who help him so he doesn’t have to carry the weight of the loss alone.

#tony stark#tony stark x reader#iron man#iron man fanfic#fanfic#fanfiction#reader insert#angst#choices

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

Windows

If you’ve ever stayed in a European youth hostel, you can picture the kind of room I’m in right now. It’s windowless and Spartan: twin beds, lumpy pillows, an ancient phone on a beat up nightstand between the beds. It’s cold in here because the air is cranked up too high, but there’s no thermostat. There’s also no clock. Time doesn’t matter here, and time also matters a great deal. The main difference between this room and a room at a cheap pensione in Florence is that when you step outside you’re not greeted by the picturesque banks of the Arno. This room is one of the two “sleeping rooms” in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit at Providence Pavilion for Women and Children in Everett, Washington, and I’m here because my baby is across the hall, hooked up to machines.

I was 35 weeks and 5 days pregnant when I woke up at 1:18 am.

“My water just broke,” I said to Flo, and my heart sank. They had told me several days prior that I should “chill out” and “take it easy,” when I visited labor and delivery to talk about the symptoms I was having, which felt suspiciously like pre-term labor. I did do things differently: I stopped going to the gym. I started doing dishes while sitting on a bar stool (for what it’s worth, we should all be doing this. It’s comfortable.) But at the same time, a small voice inside me was egging me on: reminding me to finish little tasks, to tidy up loose ends. By Saturday, I was walking through Safeway with Ladybug slower than I’ve ever walked anywhere. I almost could have predicted I’d go into labor that night. But I was at the grocery store, because we needed milk. (It’s currently turning into yogurt in the fridge. Turns out, we’d never drink the milk after all.)

Regardless, there I was at 1:18 am, trying to be clearheaded about what to do next. I packed a few things (real talk: mostly snacks) and tried calling a couple of friends before realizing that Ladybug would be joining us at the hospital. Unsurprisingly, she was thrilled. She had already packed a bag in case she needed to stay at a friend’s house. But staying at the hospital? Even better. (The next morning she did head to a friend’s for the day, and stayed there that night as well. I’m all for including the family in life events, but I don’t need to be managing a five-year-old between earth-shattering contractions.)

Earlier that week I had gotten a pregnancy update email (baby was the length of a head of Romaine lettuce at that point, I think) which highlighted the need to map out the best route to the hospital. Flo and I giggled about this, thinking back on our interminable drives to and from UCLA Medical Center as we waited for Ladybug to arrive. To get to PeaceHealth Ketchikan, by contrast, the directions were straighforward: turn left out of driveway. Turn right on Carlanna Lake Road. Turn left into the ER. It took us a minute and a half to get there from our house, where we parked steps from the entrance of the ER by a sign that said “Reserved for Patients.”

I will not bore you with my birth story. Was it Chekhov who said, “Every happy family…?” Forget it, I just googled the phrase and will spare you my version (it’s Tolstoy, by the way. Also Russian, so arguably I was close.) “All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” This is true for childbirth too. Every birth story is unique and gnarly and often funny, and the ones that go haywire are unhappy in their own ways. But if you’ve heard one birth story you kind of get the idea: the built-in spoiler alert is that it ends with the birth of a baby. As wild as the story may be, the ending is almost universally the same. All I will say is that Flo and I were holding our son at 5:43 pm, sixteen hours after we packed up our little bag and our little girl and left for the hospital. I am in love with the name we chose for him, but for the purposes of this blog he will be known as Bronson. (Long story. Ask Flo.)

Anyway, in our case it wasn’t labor and delivery that made for the interesting story. A few hours after birth, after the little man had crawled his way up my chest like his sister had done and rooted around for some dinner, the nurses noticed he was struggling to breathe. So began several days of cannulas in his nose to send air more easily to the lungs, and then an IV drip to regulate his blood sugar, and then a 24-hour moratorium on breastfeeding so he wouldn’t aspirate, and then and then and then. In the same way that they say one intervention in labor can lead to a snowball effect, it felt as though Bronson was encountering more and more obstacles day by day. But he seemed well enough by Thursday morning that we were talking about being discharged the next day. Then he stopped breathing. He was in my arms in the tiny nursery—he’d been in my arms most of the night—and he suddenly seemed sleepy. The night shift nurse stared hard at the monitor, adjusting the leads that connected him to it. Within moments, our quiet night together turned loud, bright, busy. A team of nurses, doctors, anesthesiologists, respiratory specialists—they all got to work, drawing blood, inserting a new IV, pumping air back into his lungs. It was quickly decided we would need to be medevaced to to a bigger facility with a proper NICU, which meant Flo raced home to pack me a bag. Ladybug and I cried softly in each other’s arms.

Bronson and I were loaded onto an ambulance, which drove onto the airport ferry, which then headed around the backside of the airport to a police escort and a waiting Lear jet. Bronson’s tiny body was dwarfed by the enormity of his incubator. The kind man who worked for LifeMed and sat next to me on the plane briefed me on flying in a Lear jet: basically, it goes very fast, and might make you sick, and you’ll get there in no time.

The whole time we were in the air, I honestly felt like I was dying. I was semi-reclined (perhaps in a nod to my recently revoked status as a patient.) I couldn’t breathe well, and it felt as though the top of the plane was pressing down on my chest. I stared out the window at the clouds and drifted off, out of exhaustion and terror. I couldn’t see my baby, but partway through the flight, the EMT who was sitting next to him asked for my phone. She took a picture of my beautiful boy, his eyes open and bright. He seemed to be doing better than I was.

We landed in an airfield in Everett and a firefighter walked me to the bathroom in a huge hanger. The whole thing felt so absurd that I wanted to make a joke, but for once in my life I really couldn’t think of anything to say. So I said thank you. En route to the hospital, the ambulance driver pointed through the window at the largest building in the world (so he said); a huge sign on the front of it said Boeing. I felt like I did the first time I stepped off the subway in Tokyo—that everything was big, foreign, pulsing with life in a language I didn’t understand. Bronson had another apnea episode when we arrived at the hospital but I wasn’t there to see it. I had been shunted upstairs to Admitting, where a woman who looked exactly like Iris Apfel spent ten minutes misunderstanding our primary insurance. (I think it’s in the middle of Mr. and Mrs. Smith that Angelina Jolie and Brad Pitt get into an elevator and hear The Girl From Ipanema; after a few seconds of calm and muzak, they get to the next floor and step out, guns blazing. This is what it felt like in Admitting.) Soon, though, I was back downstairs, staring into Bronson’s room as a soft spoken doctor stood next to me and plied me for information about what had happened. I turned to him.

“To be clear,” I said, asking the thing I realized I’d been wondering all day. “This isn’t a question of, ‘My baby may not make it.’ Right…?”

“No,” he said firmly. “He will be fine.”

Still. After my baby settled down for the night, his room buzzing with machines, his body a tangle of wires, I wandered across the hall to the sleeping room and made a few sobbing phone calls. I was decidedly not okay, because I was pretty sure my baby wasn’t either.

That was ten days ago. It’s been two weeks since I glanced around my living room to make sure I hadn’t forgotten anything, turned off the lights and drove away. Two weeks since I wandered the halls of PeaceHealth Ketchikan, looking through the windows at the wintry darkness between mind bending contractions. Two weeks since they said, “Pushpushpushpushpushpush,” and I did and I did and I did and then I held a small red-faced boy in my arms and cried. Two weeks of living in hospitals, he and I — and things seem easier. I chatted with a couple of nurses just now, using words I didn’t know two weeks ago, talking diagnoses and comparing the opinions and temperaments of attending neonatologists. Bronson can breathe on his own, though we’re still figuring out the root cause of his problem, which (it’s becoming clear) may extend beyond his prematurity and into something congenital or structural. Stay tuned; when I know, you’ll know. He’s eating, and sleeping, and pooping, and generally doing all the things babies do.

The other day, Flo smiled a little when he saw the blankets in the sleeping room. (He and Ladybug and my mom are staying at a Hampton Inn a few blocks away, which feels like the premise of a bad sitcom.) “We used to have these blankets in our house,” he said. This baby, our baby, who lives in a crisp clean room in a state of the art hospital — his grandfather raised five children as a single dad cleaning hospitals like this one. Our little guy has his middle name. There’s been so much talk in the last few years about privilege, but I’ve come to realize from this experience that privilege extends beyond race, class, gender, and so much else that we’ve addressed in the conversation. Privilege extends to access. Privilege extends to the ability to be relieved of pain and suffering. (That is, at least as far as medically possible.) Privilege means a shared language, and the ability to speak up for ourselves. Privilege gives us a window to look through: we can choose to see all the beauty others seem to have that we have been denied, or we could recognize the beauty we ourselves have been given that others may not have access to. All we have to do is open the window, and breathe. It’s the breathing, of course, that is the hard part. But we’re working on it.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Susan Reynolds Whyte, Health Identities and Subjectivities: The Ethnographic Challenge, 23 Med Anthro Quart 6 (2009)

Abstract

The formation of identity and subjectivity in relation to health is a fundamental issue in social science. This overview distinguishes two different approaches to the workings of power in shaping senses of self and other. Politics of identity scholars focus on social movements and organizations concerned with discrimination, recognition, and social justice. The biopower approach examines discourse and technology as they influence subjectivity and new forms of sociality. Recent work in medical anthropology, especially on chronic problems, illustrates the two approaches and also points to the significance of detailed comparative ethnography for problematizing them. By analyzing the political and economic bases of health, and by embedding health conditions in the other concerns of daily life, comparative ethnography ensures differentiation and nuance. It helps us to grasp the uneven effects of social conditions on the possibilities for the formation of health identities and subjectivities.

The ways that health is invoked in the formation of identity and subjectivity is a fruitful field for anthropologists, whether or not they consider themselves “medical.” That is because they touch on fundamental issues in social science: the workings of power in relation to social differentiation and senses of self and other. In this article, I review some of the theoretical issues at stake here, to underline the contribution of detailed ethnography to these discussions. In the interest of oversight, I will radically simplify by distinguishing two approaches: the focus on politics of identity and the concern with subjectivity and biopower. Both themes are part of a wider intellectual discussion in cultural studies, sociology, political science, history, and philosophy. Anthropologists have found inspiration here, but the commitment to comparative ethnography means that our contributions have problematized both approaches. We are concerned to specify: What particular political, historical, technological, and cultural circumstances facilitate, shape, and constrain the working of health identities? How and when do specific situated concerns move some social actors, but not others, to think and act in terms of health? What resources are at stake?

Identity Politics

The link between health and identity is not a new topic for social scientists. Goffmanput it firmly on the agenda with his magnificent essay on stigma from 1963. Health issues—disability and mental illness—provided some of his most striking examples of the management of spoiled identity. Sociologists working with labeling theory in the 1960s and 1970s emphasized the formative effects of diagnostic practices for people who learned how to be different after being so identified by authorities. In anthropology, research on spirit possession and initiation to the role of healer, shaman, or diviner often focused on identity and its transformation. Ethnic or national identity, indeed identification with any kind of imagined community, can be linked to therapeutic systems. Pride in, or allegiance to, Ayurveda or African traditional medicine or homeopathy is a kind of medicinal cultural politics that places a person by expressing loyalty to one system in opposition to another.

Identity is about similarity and difference between selves and others. But as Richard Jenkins points out, it is the verb to identify and not the noun identity that opens the richest analytical perspectives. The verb makes identity a process that happens between people. He quotes Boon to the effect that social identity is a game of playing the vis-à-vis; and he underlines that identities work and are worked (Jenkins 1996:4–5). It is this practicing of identities with an eye to consequences that forms the first part of the opposition I wish to explore.

Identity politics is about the revaluation of difference: the assertion of a difference that had been disvalued, the witnessing of discrimination, and the struggle for recognition, rights and social justice. Sometimes called the politics of difference or of recognition, it is at once personal and collective. As noted in an early article on mental illness and identity politics: “insofar as they seek to effect changes in public policy, [such social movements] consciously endeavor to alter both the self-concepts and societal conceptions of their participants” (Anspach 1979:766).

Identity politics is a child of the 1960s and very much a part of U.S. social history. The philosopher Richard Rorty traces a transformation in U.S. leftist thinking from the pre-1960s Reformist Left to the Cultural Left that marked the 1970s, 80s, and 90s. Where the old Left was concerned with economic injustice, the new one took on prejudice. As Rorty puts it, the new “politics of difference” was about stigma and humiliation, rather than greed and money: sadism not selfishness (Rorty 1998:76–77). He thus sets up a dichotomy between a politics of recognition and a politics of redistribution (Fraser 1998).

From the civil rights movement to Black power, feminism, gay rights, and multi-

culturalism, the politics of identity put recognition of difference on the agenda. Recognition was a first and necessary step toward action for change. As Terence Turner argued concerning multiculturalism, identity politics was about “collective social identities engaged in struggles for social equality” (Turner 1993:412). There is always a possibility that politics of identity can fetishize difference and tend toward separation, but it can also make a critical contribution to politics in the sense of discussion and action among a plurality of people.

In the arena of health, the disability movement is perhaps the clearest example of identity politics. The militant campaign for disability rights in many countries was accompanied by an increased sensitivity about identity and respect, as expressed in language, law, and even architecture. In the academy, the field of Disability Studies emerged with a strong focus on recognition, personal experience, and the social and cultural processes of disablement. The interest in identity spread beyond the “classic” motor, sensory, and intellectual handicaps to encompass obesity, chronic illnesses, infertility, old age, and even traumatic experiences like being raped or tortured (see the range of contributions in Ingstad and Whyte 2007).

There is often an overlap between movements making claims for justice from the larger society and support groups for people sharing a common problem. Between the two poles of identity politics, the collective and the personal, different balances are made between common political efforts and individual endeavors to rework a devalued identity. The whole continuum of health rights movements and support groups is better represented in the global north than in the resource-poor settings of the south. But scholars are beginning to examine the emergence of identity politics of health in developing countries, and their research can provide a needed comparative perspective.

One of the best studies from Africa is a historical work on leprosy and identity in twentieth-century Mali (Silla 1998). Silla shows how the establishment of leprosaria by missionaries and later the implementation of vertical treatment programs by WHO facilitated the transition from commonality to community. People with leprosy left their rural homes to move near clinics and remained in town with others like themselves after being cured. Silla shows that a group identity as lepers developed out of an interplay of institutional catalysts, a critical mass of similarly disabled people, and common interests in survival strategies (including begging). In 1991, a formal association of leprosy patients emerged to overshadow earlier informal groupings, such as the one formed by women beggars. The new organization had more educated leaders, and it joined the national disability federation and took up an agenda of disability rights.

I and Herbert Muyinda (2007) trace the mobilization of people with mobility disabilities in two border towns in eastern Uganda. Accused of being smugglers, they counter by asserting their rights as disabled people. Unlike the situations of lepers in Mali described by Silla, or that of mobility-disabled people in Western Tanzania studied by Van den Bergh (1995), there were neither treatment institutions nor training programs that drew disabled people to town. They came seeking economic opportunities they did not have in their villages. People used connections with relatives and friends to make a start in town, and to get enough cash to obtain their most essential capital: a hand-crank tricycle. Physical mobility was necessary for social extension and political mobilization. Getting a life in the particular niche of cross-border trade that they were exploiting brought them together around common interests; they formed an association to support those interests and took advantage of the national requirement that disabled people be represented on district and municipal councils. Although the political organization of people with disabilities is countrywide, some people identify themselves as disabled far more actively than others. In Busia and Malaba, men with motor impairments form the core of organization, whereas women and people with other disabilities are far less active. We draw connections to the political economy of the border region, to the role of donors in supporting rehabilitation projects, and to Uganda's policy on disability.

Both the lepers in Mali and the mobility-disabled people in eastern Uganda came together around common interests in particular local worlds. From there they made contacts with national and even international organizations. They connected with people from outside their immediate localities who passed on new ideas and new social technologies that they could use in their own local situations. Even in European countries, where institutions and organizations have been in place for some time to provide services or advocate for people with disabilities, the importance of grounding fellowship in specific projects and experiences of commonality should not be underestimated, as shown in Priestley's work (1995) on an organization of blind Asians in Leeds.

These examples of identity politics fit well with current paradigms for health and development that emphasize the “rights-based” approach. Whether the theme is sexual and reproductive health, disability, or health care services, people are to be seen as citizens having rights, rather than mere beneficiaries, clients, or customers. They are to make claims and participate in decisions that affect their lives. Their own understandings and actual struggles, not the programs of outside agencies, should be the basis for change (Institute of Development Studies [IDS] 2003). But of course their own understandings include their perceptions of the possibilities and rationalities of programs. Ethnographic approaches to health identity politics often focus on the way people use agencies and discourses to make claims that further their own projects and agendas.

Ethnography does not assume identity politics but questions the conditions for its existence, as exemplified by a study of diabetes in Beijing by Mikkel Bunkenborg (2003). In the liberalizing political economy of China, where multinational drug companies play an important role in providing information about diabetes, patients become consumers and are rather left to their own devices to manage their condition. They feel unjustly treated, and they carry a heavy economic burden in having to finance their own treatment while they also risk losing their jobs. Bunkenborg describes the informal circles of fellow patients who support one another and pass on knowledge. But he doubts whether there is a politics of identity at work here. It is not a case of diabetic identity as a basis for a social organization of equals with common interests making claims for recognition and rights. Rather he sees these networks as part of the politics of the self in which people cultivate moral character and interact in differentiated and more hierarchical networks of particularistic relations. This is not just a legacy of Confucianism, but a function of the difficulty of forming civil society organizations in China, the insecurity of an unregulated market, unequal access to health care and knowledge, and the management of a disease that requires discipline of the self (Bunkenborg 2003:89–91). Bunkenborg's analysis leads on to the second way of approaching the link between health and identity, which is perhaps better phrased as a relation between health and subjectivity.

Biopower

Michel Foucault's influence in problematizing health and power has been enormous, although perhaps more profound for medical sociology than anthropology. His concept of biopower focuses on discourses and practices that work both at the level of the self and at the level of whole populations. In this sense, it is relevant to consider biopower in relation to health and the politics of identity. However, unlike identity politics, biopower approaches are not generally concerned with explicit political action and debates about social justice. Rather they point toward the much more subtle shaping of subjectivity, of assumptions and bodily practice and attentiveness. Knowledge, technologies, and control are the watchwords.

Inspired by his writings and deeply immersed in the significance of new developments in biological science, Paul Rabinow (1996) launched the term biosociality to capture the ways that biological nature, as revealed and controlled by science, becomes the basis for sociality. His examples are the ways that genetic testing and other kinds of medical technology yield social–biological classifications that are practiced in new kinds of organizations.

I will underline … the likely formation of new group and individual identities and practices arising out of these new truths. There already are, for example, neurofibromatosis groups whose members meet to share their experiences, lobby for their disease, educate their children, redo their home environment, and so on. That is what I mean by biosociality. [Rabinow 1996:102]

Whereas an older generation of social scientists was concerned with the relation between health and bioidentities like race, gender, and age, we must now, according to Rabinow, examine the ways that diagnostic technology actually creates social difference and social groupings. Maybe this is beginning to happen even in developing countries. In Uganda, people who have been screened for HIV are encouraged to join post-test clubs. Although Rabinow emphasizes diagnostics, therapeutic technology can also form the basis for biosociality as in the case of support groups for people who have had mastectomies, colostomies, and transplants, or who are on lifelong antiretroviral therapy.

Here too ethnography is the test. Biosociality is not a given, but an empirical question. How does it work in particular circumstances? A beautiful example is Rayna Rapp's monograph on amniocentesis in the United States (1999). Her study differentiates “the subject,” which includes a whole range of people who live in New York, whom she identifies by age, ethnicity, and job.

Biosociality, “the forging of a collective identity under the emergent categories of biomedicine and allied sciences” (Rapp 1999:302) was one possibility for the parents of Down syndrome children. But it was mostly for a minority: mothers from two-parent families, middle-class, white, having resources of time and income. Although Rapp describes with sympathy the communities of difference, the friendship, the sharing of experience that these parents found in support groups, she also conveys critical voices, like that of Patsy DelVecchio, a recovering alcoholic who expresses resentment of class and of what she sees as self-promotion through identifying with difference.

I cannot see myself sitting with a bunch of petty little women, talking about their children like they were some kind of topic of conversation. This is just life … You get a lot of mothers that's behaving just like in AA, like, “Yeah, I'm an alcoholic,”“Yeah, I'm the mother of a Down's child.”… You get these Park Avenue high-society women with charge accounts saying, “I have my daughter at the institute, I have a private tutor for my daughter.”[Rapp 1999:299–300]

Concerning biosociality, Rapp concludes:

Biomedicine provides discourses with hegemonic claims over this social territory, encouraging enrollment in the categories of biosociality. Yet these claims do not go uncontested, nor are these new categories of identity used untransformed. … At stake in the analysis of the traffic between biomedical and familial discourses is an understanding of the inherently uneven seepage of science and its multiple uses and transformations into contemporary social life. [Rapp 1999:302–303]

It is the uneven seepage of science, the multiple uses and transformations that catch the ethnographer's eye, and not any straightforward working out of biopower expressed in bioidentities, subjectivities, and socialities.

The influence of Foucault is further refracted in the notion of biological (or biomedical or therapeutic) citizenship. Two sociologists, Nikolas Rose and Carlos Novas (2005), use “biological citizenship” to call attention to the way that conceptions of citizens are linked to beliefs about biological existence. Like Rabinow, they are interested in the implications of new biomedical technology for forms of biosociality, although they also note that biosocial groupings are far older than recent developments in genomics and biomedicine—and they make the link to earlier forms of activism and identity politics. Biological citizens are “made up” from above (by medical and legal authorities, insurance companies). And they also make themselves. The active biological citizen informs herself, and lives responsibly, adjusting diet and lifestyle so as to maximize health. “The enactment of such responsible behaviors has become routine and expected, built in to public health measures, producing new types of problematic persons—those who refuse to identify themselves with this responsible community of biological citizens” (Rose and Novas 2005:451).

This discussion of biological citizenship is programmatic and decontextualized. Most of the examples come from Internet sites; there are no lifeworlds here and no social differences of the kind Rapp reported. In this formulation, politics concerns an all-pervasive power that shapes perceptions and subjectivity. Citizens are categorized and behave (or not) in conformity with a biologically oriented discourse. In contrast, the ethnographic uses of the concept of citizenship are more focused on the variety of ways in which actors try to make claims and relate to agencies and institutions through health identities.

Adriana Petryna's original concept of biological citizenship was developed to analyze the struggles and strategies of Ukrainians exposed to radiation when the Chernobyl nuclear reactor exploded in 1986 (Petryna 2002). Skillfully she weaves the original Soviet denial of extensive damage together with the acceptance of state obligations to its citizens by the new government of independent Ukraine. She shows how damaged biology became the basis for making citizenship claims in the difficult conditions of a harsh market transition, increasing poverty, and loss of security. Biopower is part of her story, in that access to treatment, pensions, and other welfare benefits was based on medical, scientific, and legal criteria: “… science has become a key resource in the management of risk and in democratic polity building” (Petryna 2002:7).

Citizens have come to rely on available technologies, knowledge of symptoms, and legal procedures to gain political recognition and access to some form of welfare inclusion. Acutely aware of themselves as having lesser prospects for work and health in the new market economy, they inventoried those elements in their lives (measures, numbers, symptoms) that could be connected to a broader state, scientific, and bureaucratic history of error, mismanagement, and risk. The tighter the connections that could be drawn, the greater the probability of securing economic and social entitlements—at least in the short term. [Petryna 2002:15–16]

In a sense Petryna is describing what Rose and Novas call “making up biological citizens.” To “make the Chernobyl tie” and thus gain recognition by the state, people have to identify themselves in terms of certain symptoms. But Petryna is not talking about some general biopower; she specifies in terms of Ukrainian political history and the international humanitarian aid that made a disabled identity a survival strategy. She brings in the Ukrainian (and Soviet) cultural economy showing how those with good blat connections, or those who could exchange favors or money, were able to negotiate “better” diagnoses, higher disability status, and more entitlements. She gives examples of people who chose to neglect their symptoms, to keep working in the contaminated zone where salaries were much higher. Through her descriptions, we see situated actors who get drunk and beat their wives, try to avoid being drafted into the army, fail to play their sick roles convincingly, or succeed brilliantly as members of disability organizations.

Also anthropologists working with responses to AIDS have taken on the concept of biological citizenship to illuminate issues of rights, claims, and social exclusion. Like Petryna, they place health identities in the context of national history and global connections. Biehl (2004), writing about the activist state in Brazil, shows that “biomedical citizenship” includes those who identify themselves as having AIDS and actively struggle for treatment from public services. Those who do not assert their AIDS identity and rights to treatment—people marginalized by poverty, drug use, prostitution, homelessness—are excluded and made invisible. Community-run houses of support provide a chance for some of these “disappeared” people to be included in the “biocommunity” of AIDS patients: “in such houses of support, former noncitizens have an unprecedented opportunity to claim a new identity around their politicized biology” (Biehl 2004:122).

In a similar approach Nguyen analyses access to antiretroviral drugs in Burkina Faso in terms of a kind of biopolitics that he calls “therapeutic citizenship.” Unlike Brazil, most African states have so far been unable to include those identified as having AIDS within a supportive national community. Instead, local mobilization appeals to a global therapeutic order. Therapeutic citizenship is “a form of stateless citizenship whereby claims are made on a global order on the basis of one's biomedical condition” (Nguyen 2005:142). Activism on behalf of a wider community—a kind of identity politics—is one outcome of identification as HIV+ in Burkina Faso. But Nguyen's ethnographic analysis, like Petryna's, reveals a differentiated situation, in which some people form a vanguard of activists, whereas others are discrete about their identity as HIV+.

Toward Comparative Ethnography

At the risk of caricature, I have contrasted two different approaches to the study of health, identity, and politics. Identity politics focuses on social movements and organizations that reject neglect and discrimination and look to gain recognition and change social conditions. Scholars and activists in this tradition tend to assume conscious actors with intentions. Their questions move forward from the present: who is suffering? what is just? what can be done? The biopower approach problematizes the workings of discourse and technology in the shaping of subjectivity and new kinds of social relations. Its actors are not necessarily conscious of the processes affecting them. The questions here look back to explain the present: how is it that we have come to think like this? associate like this? act like this?

Conventionally, such a strategy of rhetorical dichotomizing ends with a synthesis. Nancy Fraser (1998), for example, argues that neither the politics of recognition, nor that of redistribution, can stand alone in the pursuit of social justice. Both are necessary. In the same classic style, I could point out that newer work on biocitizenship combines identity politics with biopower. The Foucauldian interest in the state and the self, the two poles of biopower, is enlarged with a focus on biosocial groups that make claims for inclusion and justice.

Yet I think it is more important to draw another point from this brief overview. There are pitfalls in both approaches. There is a danger that we lose sight of the political and economic bases of health in our concern with identity, recognition, and the formative effects of biomedical and social technology. By concentrating on the emergence of identities based on health categories, we may ignore other fundamental differences at the root of health inequities. Moreover, focusing narrowly on relations among people with the same health condition excludes all the other relations and domains of sociality that actually fill most of their daily lives. In fact, those other relations may strongly influence the ways that health comes to shape their identities and subjectivities. By defining research problems based on identifications like diabetic, Down syndrome, HIV+, we essentialize, fragment, and decontextualize what is really only part of a life. And it is, after all, a life and not an identity that people are usually seeking, as Michael Jackson reminds us (2002:119).

I have tried to show how detailed, comprehensive ethnography avoids these pitfalls and thereby problematizes identity politics and biopower in more interesting ways. By specifying history and political economy, the examples I have adduced allow us to examine the conditions under which identity politics and biopower might come into play. By describing patterns of social interaction, morality, and meaning, they suggest the processes through which assumptions and consciousness about health assume significance. Finally they are richly textured because the researchers have talked to many kinds of people and considered the multiplicity of domains in social life. The differentiated picture they paint shows not only the uneven seepage of science and medicine into social life, but also the uneven effects of different social conditions on the possibilities for the formation of health identities and subjectivities. With such ethnography in hand, we can begin to make comparisons over time and across social settings—still a major task for anthropology, medical and otherwise.

References

Anspach, Renee 1979 From Stigma to Identity Politics: Political Activism among the Physically Disabled and Former Mental Patients. Social Science and Medicine 13A:765–773.

Biehl, João 2004 Global Pharmaceuticals, AIDS, and Citizenship in Brazil. Social Text 22(3):105–132.

Bunkenborg, Mikkel 2003 Crafting Diabetic Selves: An Ethnographic Account of a Chronic Illness in Beijing. Masters thesis in Chinese Studies. Copenhagen : University of Copenhagen.

Fraser, Nancy 1998 Social Justice in the Age of Identity Politics: Redistribution, Recognition and Participation. Tanner Lectures on Human Values 19:1–67.

Goffman, Erving 1963 Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. Englewood Cliffs , NJ : Prentice-Hall.

Ingstad, Benedicte, and Susan ReynoldsWhyte, eds. 2007 Disability in Local and Global Worlds. Berkeley : University of California Press.

Institute of Development Studies (IDS) 2003 The Rise of Rights: Rights-Based Approaches to International Development. IDS Policy Briefing 17. Sussex : IDS.

Jackson, Michael 2002 The Politics of Storytelling: Violence, Transgression and Intersubjectivity. Copenhagen : Museum Tusculanum Press.

Jenkins, Richard 1996 Social Identity. London : Routledge.

Nguyen, Vinh-kim 2005 Antiretroviral Globalism, Biopolitics, and Therapeutic Citizenship. InGlobal Assemblages: Technology, Politics, and Ethics as Anthropological Problems. A.Ong and S. J.Collier, eds. Pp. 124–144. Malden , MA : Blackwell.

Petryna, Adriana 2002 Life Exposed: Biological Citizens after Chernobyl. Princeton : Princeton University Press.

Priestley, Mark 1995 Commonality and Difference in the Movement: An “Association of Blind Asians” in Leeds. Disability and Society 10(2):157–169.

Rabinow, Paul 1996 Artificiality and Enlightenment: From Sociobiology to Biosociality. In Essays on the Anthropology of Reason. P.Rabinow, ed. Pp. 91–111. Princeton : Princeton University Press.

Rapp, Rayna 1999 Testing Women, Testing the Fetus: The Social Impact of Amniocentesis in America. New York : Routledge.

Rorty, Richard 1998 Achieving Our Country: Leftist Thought in Twentieth-Century America. Cambridge , MA : Harvard University Press.

Rose, Nikolas, and Carlos Novas 2005 Biological Citizenship. In Global Assemblages: Technology, Politics, and Ethics as Anthropological Problems. A.Ong and S. J.Collier, eds. Pp. 439–463. Malden , MA : Blackwell.

Silla, Eric 1998 People Are Not the Same: Leprosy and Identity in Twentieth-Century Mali. Portsmouth , NH : Heinemann.

Turner, Terence 1993 Anthropology and Multiculturalism: What Is Anthropology that Multiculturalists Should Be Mindful of it? Cultural Anthropology 8(4):411–429.

Van den Bergh, Graziella 1995 Difference and Sameness: A Socio-Cultural Approach to Disability in Western Tanzania. MA thesis, Social Anthropology, University of Bergen.

Whyte, Susan Reynolds, and Herbert Muyinda 2007 Wheels and New Legs: Mobilization in Uganda. In Disability in Local and Global Worlds. B.Ingstad and S. R.Whyte, eds. Pp. 287–310. Berkeley : University of California Press.

#identity#identityformation#subjectivity#identity politics#ethnography#health#biomedicine#technology#biosociality

0 notes