#anti intellectual

Text

some of yall have completely misconstrued what anti-intellectualism is and all you're doing is indirectly promoting more anti-intellectualism through your misdirection and it's so counterproductive. anti-intellectualism is a hostility or indifference toward knowledge or reasoning. anti-intellectualism is a deprecation of the value of art, culture and literature. anti-intellectualism is the rejection of critical thought. it is the reduction of creation and formal education to void capitalist products.

anti-intellectualism is NOT just enjoying things because they're fun or pleasing to you.

#get it right... it is the unwillingness to value the intellect or engage in critical thinking that is anti-intellectualism#it is not binge-watching [insert tv show] on a saturday night#some of yall sound like henry winter and that's how i know you misread that woman's book on top of everything#anti intellectualism#anti intellectual#media literacy#books and literature

140 notes

·

View notes

Text

#smh#anti intellectual#get a grip jb#a little life#jude st francis#a little life play#een klein leven#a little life book#malcolm irvine#jb marion#jean baptiste marion#willem ragnarsson

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Coleman Hughes

Published: Oct 27, 2019

In 2016, Ibram X. Kendi became the youngest person ever to win the National Book Award for Nonfiction. His surprise bestseller, Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas, cast him in his role as an activist-historian, ambitiously attempting to make 600 years of racial history digestible in 500 pages. In his follow-up, How to Be an Antiracist, Kendi––now 37, a Guggenheim fellow, and a contributing writer at The Atlantic––reveals his personal side, weaving together memoir, polemic, and instruction as he invites the reader to join him on the frontlines of what I like to call the War on Racism.

If the book has a core thesis, it is that this war admits of no neutral parties and no ceasefires. For Kendi, “there is no such thing as a not-racist idea,” only “racist ideas and antiracist ideas.” His Manichaean outlook extends to policy. “Every policy in every institution in every community in every nation is producing or sustaining either racial inequity or equity,” Kendi proclaims, defining the former as racist policies and the latter as antiracist ones.

Every policy? That question was posed to Kendi by Vox cofounder Ezra Klein, who gave the hypothetical example of a capital-gains tax cut. Most of us think of the capital-gains tax, if we think about it at all, as a policy that is neutral as regards questions of race or racism. But given that blacks are underrepresented among stockowners, Klein asked, would it be racist to support a capital-gains tax cut? “Yes,” Kendi answered, without hesitation. And in case you planned on escaping the charge of racism by remaining agnostic on the capital-gains tax, that won’t work either, because Kendi defines a racist as anyone who supports “a racist policy through their actions or inaction.”

Hailed by the New York Times as “the most courageous book to date on the problem of race in the Western mind,” How to Be an Antiracist is certainly bold in its effort to redefine a concept that bedevils American society. On his unusually expansive definition, Kendi sees racism operating not just behind niche issues like the capital-gains tax but also behind problems of civilizational significance. “Racism,” he writes, “has spread to nearly every part of the body politic,” “heightening exploitation,” causing “arms races,” and “threatening the life of human society with nuclear war and climate change.” How, exactly, racism is behind the threat of nuclear holocaust is left to the reader’s imagination.

At times, it’s hard to know whether to interpret Kendi’s arguments as factual claims subject to empirical scrutiny or as diary entries to be accepted as personal truths. Indeed, much of the book reads like a seeker’s memoir or a conversion story in the mold of Augustine’s Confessions. Raised in a rough part of Queens in the 1990s, Kendi recounts his long journey from anti-black racism to anti-white racism, and eventually, to antiracism. In high school, Kendi delivered a speech bemoaning the bad behavior of black youth; by college, he had outgrown that phase and become anti-white, convinced at one point that white people were literal aliens but later scaling down to the belief that they were “simply a different breed of human.” A New Yorker piece cites a column he wrote as an undergraduate, in which he argued that “white people were fending off racial extinction, using ‘psychological brainwashing’ and ‘the aids virus.’”

Having matured out of his anti-white phase, Kendi takes a refreshingly strong stand against anti-white racism in the book, rejecting the fashionable argument that blacks cannot be racist because they lack power. He reflects with embarrassment on his old beliefs, avoiding condescension by lecturing his former self instead of the reader. Still, certain autobiographical details call for embarrassment but don’t get it. He recalls, for example, his first night living in Virginia as a teenager, during which he stayed up all night, “worried the Ku Klux Klan would arrive any minute.” That took place in 1997.

The book is weakest in its chapter devoted to capitalism. “Capitalism is essentially racist,” Kendi proclaims, and “racism is essentially capitalist.” To test this claim, a careful thinker might compare racism in capitalist countries with racism in socialist/Communist ones; or he might compare racism in the private sector with racism in the public sector. Kendi does neither. Instead, he presents the link between capitalism and racism as self-evidently true: “Since the dawn of racial capitalism, when were markets level playing fields? . . . . When could Black people compete equally with White people?” Kendi asks, implying that the answer is “never.”

I can think of several historical examples in which capitalism inspired anti-racism. The most famous is the Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court case, when a profit-hungry railroad company––upset that legally mandated segregation meant adding costly train cars––teamed up with a civil rights group to challenge racial segregation. Nor was that case unique. Privately owned bus and trolley companies in the Jim Crow South “frequently resisted segregation” because “separate cars and sections” were “too expensive,” according to one scholarly paper on the subject.

A lesser known example is the South African housing market under Apartheid. Though landlords in whites-only areas were legally barred from renting to nonwhites, vacancies made discrimination against non-white tenants costly. As a result, white landlords often ignored the law. In his book South Africa’s War on Capitalism, economist Walter Williams notes that at least one “whites-only” district was in fact comprised of a majority of nonwhites.

History offers little evidence that capitalism is either inherently racist or antiracist. As a result, Kendi must resort to cherry-picking data to demonstrate a link. Citing a Pew article, he asserts that the “Black unemployment rate has been at least twice as high as the White unemployment rate for the last fifty years” because of the “conjoined twins” of racism and capitalism. But why limit the analysis to the past 50 years? A paper cited in the same Pew article reveals that the black-white unemployment gap was “small or nonexistent before 1940,” when America was arguably more capitalist—and certainly more racist.

Kendi also cherry-picks his data when discussing race and health. He laments that blacks are more likely than whites to have Alzheimer’s disease, but neglects to mention that whites are more likely to die from it, according to the latest mortality data from the Center for Disease Control. In the same vein, he correctly notes that blacks are more likely than whites to die of prostate cancer and breast cancer, but does not include the fact that blacks are less likely than whites to die of esophageal cancer, lung cancer, skin cancer, ovarian cancer, bladder cancer, brain cancer, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and leukemia. Of course, it should not be a competition over which race is more likely to die of which disease––but that’s precisely my point. By selectively citing data that show blacks suffering more than whites, Kendi turns what should be a unifying, race-neutral battle ground––namely, humanity’s fight against deadly diseases––into another proxy battle in the War on Racism.

Worse than the skewed approach to data in Kendi’s book are the factual errors. Citing an entire book by Manning Marable (but no specific page), Kendi claims that in 1982, “[President Reagan] cut the safety net of federal welfare programs and Medicaid, sending more low-income Blacks into poverty.” I could not find any data in Marable’s book showing that the black poverty rate rose during Reagan’s tenure. In fact, the opposite appears to be true, according to the Census Bureau’s historical poverty tables: the black poverty rate decreased for every age group between 1982 and the end of Reagan’s tenure in 1989.

Also erroneous is Kendi’s claim, for which he offers no citation, that “White women” are the “primary beneficiaries” of “affirmative-action programs.” Judging from a similar claim made in Vox, this myth seems to come from a paper published by the critical race theorist Kimberlé Crenshaw in 2006. Crenshaw’s paper, troublingly, contains no data and no empirical analysis. However, a group of political scientists did conduct an empirical study on the relationship between white women and affirmative action in the same year. They found that employers who supported affirmative action were no more likely to employ white women than employers who didn’t. The primary beneficiaries of affirmative action—at least in university admissions—are, in fact, the black and Latino children of middle- and upper-middle-class families.

What Kendi lacks in empirical rigor he makes up for in candor. Whereas many antiracists dance awkwardly around the fact that affirmative action is a racially discriminatory policy, Kendi says what they probably believe but are too afraid to say: namely, that “racial discrimination is not inherently racist.” He continues:

The defining question is whether the discrimination is creating equity or inequity. If discrimination is creating equity, then it is antiracist. If discrimination is creating inequity, then it is racist. . . . The only remedy to racist discrimination is antiracist discrimination. The only remedy to past discrimination is present discrimination. The only remedy to present discrimination is future discrimination.

Insofar as Kendi’s book speaks for modern antiracism, then it should be praised for clarifying what the “anti” really means. Fundamentally, the modern antiracist movement is not against discrimination. It is against inequity, which in many cases makes it pro-discrimination.

The problem with racial equity––defined as numerically equal outcomes between races––is that it’s unachievable. Without doubt, we have a long way to go in terms of maximizing opportunity for America’s most disadvantaged citizens. Many public schools are subpar, and some are atrocious; a sizable minority of black children grow up in neighborhoods replete with crime and abandoned buildings, while a majority grow up in single-parent homes. Too many blacks are behind bars.

All this is true, yet none of it implies that equal outcomes are possible. Kendi discusses inequity between ethnic groups––which he views as identical to inequity between racial groups—as problems created by racist policy. This view commits him to some bizarre conclusions. For example, according to 2017 Census Bureau data, the average Haitian-American earned 68 cents for every dollar earned by the average Nigerian-American. The average French-American earned 70 cents for every dollar earned by the average Russian-American. Similar examples abound. Is it more likely that our society imposes policies that discriminate against American descendants of Haiti and France, but not Nigeria and Russia—or that disparities between racial and ethnic groups are normal, even in the absence of racist policies? Kendi’s view puts him firmly in the former camp. “To be antiracist,” he claims, “is to view the inequities between all racialized ethnic groups”––by which he means groups like Haitian-Americans and Nigerian-Americans––“as a problem of policy.” Put bluntly, this assumption is indefensible.

What would it take to achieve a world of racial equity? Top-down enforcement of racial quotas? A constitutional amendment banning racial disparity? A Department of Antiracism to prescreen every policy for racially disparate impact? These ideas may sound like they were conjured up to caricature antiracists as Orwellian supervillains, but Kendi has actually suggested them as policy recommendations. His proposal is worth quoting in full:

To fix the original sin of racism, Americans should pass an anti-racist amendment to the U.S. Constitution that enshrines two guiding anti-racist principles: Racial inequity is evidence of racist policy and the different racial groups are equals. The amendment would make unconstitutional racial inequity over a certain threshold, as well as racist ideas by public officials (with “racist ideas” and “public official” clearly defined).

Kendi’s suggestion that “racist ideas” would or could be rigorously defined is cold comfort, given his capacious definition of racism. In his book, Kendi calls belief in an achievement gap between black and white students a “racist idea.” Does that mean that President Obama would have violated Kendi’s antiracist amendment when he talked about the achievement gap in 2016? Would we have to overturn the First Amendment to make way for the anti-racist amendment?

Kendi’s proposal continues:

[The anti-racist amendment] would establish and permanently fund the Department of Anti-racism (DOA) comprised of formally trained experts on racism and no political appointees. The DOA would be responsible for preclearing all local, state and federal public policies to ensure they won’t yield racial inequity, monitor those policies, investigate private racist policies when racial inequity surfaces, and monitor public officials for expressions of racist ideas. The DOA would be empowered with disciplinary tools to wield over and against policymakers and public officials who do not voluntarily change their racist policy and ideas.

Kendi’s goals are openly totalitarian. The DOA would be tasked with “investigating” private businesses and “monitoring” the speech of public officials; it would have the power to reject any local, state, or federal policy before it’s implemented; it would be made up of “experts” who could not be fired, even by the president; and it would wield “disciplinary tools” over public officials who did not “voluntarily” change their “racist ideas”—as defined, presumably, by people like Kendi. What could possibly go wrong?

The odds of Kendi’s proposal entering the political mainstream may seem miniscule and therefore not worth worrying about. But that’s what people said about reparations as recently as two years ago. In the long run, American public opinion on race will change. In five, ten, or 50 years, supporting an anti-racist constitutional amendment might become the new progressive purity test.

Kendi, however, doesn’t think it’s likely. Despite the wild success of his own book tour––drawing crowds “so large that bookstores have resorted to holding readings in churches, synagogues and school auditoriums”––he nevertheless thinks that the antiracist project will probably fail. For one thing, he doesn’t believe that people can be persuaded out of racism. “People are racist out of self-interest, not out of ignorance,” Kendi writes. Thus, racists can’t be educated out of their racism. “Educational and moral suasion is not only a failed strategy,” he laments, it’s a “suicidal” one.

This is a tough claim to square with the rest of the book, which contains story after story in which Kendi gets persuaded out of his racist beliefs––including one where a friend named Clarence reasons him out of believing that white people are extraterrestrials. Indeed, what makes Kendi’s personal story so compelling is precisely the fact that he’s constantly changing. That said, when reflecting on his college days, Kendi describes his former self as “a believer more than a thinker,” so perhaps not everything about him has changed.

How to Be an Antiracist is the clearest and most jargon-free articulation of modern antiracism I’ve read, and for that reason alone it is a useful contribution. But the book is poorly argued, sloppily researched, insufficiently fact-checked, and occasionally self-contradictory. As a result, it fails to live up to its titular promise, ultimately teaching the reader less about how to be antiracist than about how to be anti-intellectual.

==

"I would define [racism] as a collection of racist policies that lead to racial inequity that are substantiated by racist ideas."

-- Ibram X. Kendi

-

"I take umbrage at the lionization of lightweight, empty-suited, empty-headed mother-fuckers like Ibram X. Kendi, who couldn’t carry my book-bag."

-- Glenn Loury

#Coleman Hughes#Kendi is a racist#Ibram X. Kendi#Henry Rogers#How to Be an Antiracist#antiracism as religion#antiracism#anti intellectualism#anti intellectual#intellectual fraud#religion is a mental illness

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

the funniest thing about tumblr fandoms for good well-made thought out media is seeing people point shit out while saying "i know its not that deep but-" girl it literally is. sometimes good writers will make the curtains blue on purpose to symbolize something. you are analyzing and interpreting bro

13K notes

·

View notes

Text

ngl, I'm beginning to take issue with how in conversations about anti-intellectualism almost automatically, the face of girls and women will be slapped on the problem.

#'all those tiktok girls who only like marvel films and' - why do you always say girls and women? are the guys filling opera halls instead?#'women in their mid 20s who still only read YA novels' okay sure that's an example and relevant discussions can be had#but it reminds me of the mocking tone in which people speak of 'chick-lit' to use women's interest as an indicator of lower value#while in fact women are reading more than men in EVERY single genre of fiction. Women are doing a lot of (often unpaid) labour#supporting libaries supporting theatres supporting cultural events#meanwhile there is a pretty big overlap between toxic masculinity and anti-intellectualism#(especially misogyny and homophobia)#especially when it comes to things like ballet or opera or musical or generally dance#in fact it is often the female investment in specific things that makes them less 'valuable' in general consciousness#for thousands of years the theatre was well-respected and a high form of art - and now it's a 'wife-thing'#the father who will teach his son that theatre and dance are for girls - how is that never an example for anti-intellectualism

16K notes

·

View notes

Text

saw one too many dark academia posts in the classics tag and became evil

#tagamemnon#heres the thing. i dont care if you enjoy the aesthetic or whatever#BUT the complete lack of sourcing and checking if quotes are real and also. the weird anti-intellectual and racist vibes??#cant do it. i cant#queueusque tandem abutere catilina patientia nostra

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

the nouvelle vague

on the deck of nouvelle the sunlight falls through slats that should remind one of soneva - nothing is straight, everything is crooked. like sonu.

jk.

it's an interesting place because downstairs it has an almost posh, leafy feel. and up here it's still fairly neat, but beyond us, near the walls that overlook the sea, the restaurant is surprisingly hotaa-like.

thakuru and i are sitting by the canopy of the banyan tree. it's uncanny how greenery can transform a place, lighten the mood.

'you see the fruit of this tree?' says thakuru.

'what fruit? this tree bears no fruit, stupid.'

'look carefully,' says thakuru smiling. 'for once, be observant. you're supposed to be a writer, aren't you?'

'all right, all right,' i tell him. and then i see them, reddish balls about as big as kaani seeds.

'what's so special about those?' i ask thakuru.

'it's evolution in action,' he says. 'the tree is pollinated by a wasp, a special wasp that evolved with the tree.'

'ok. so, what? you kill the wasp and that kills the tree?'

thakuru looks at me in mock surprise.

'would that it were so simple,' he says.

'would that it 'twere.'

'no that's not how you -' begins thakuru and then he lets out a sigh of relief.

'our food is here,' he announces. the server places two plates of chicken rice on the table.

'my god it's good,' i say. the chicken is deliciously moist, the soy and sesame seed dip bringing out the richness of the meat.

'good pick,' says thakuru. 'so, what's new with you?'

'well, i went to that new gallery.'

'ah!' he says. 'very much your speed, eh?'

'i don't know about that. but yeah, i really liked the art. it was awesome.'

'except?' asks thakuru, noticing my expression.

'hmm. it felt like the gallery wanted to intellectualise stuff.'

'ah,' says thakuru. 'but what do you mean exactly?'

'like you know. it implored visitors to think. but i mean, why? this is art! it doesn't need to justify itself on reason's terms.'

'oh, just ignore the writing and engage with the art,' thakuru smiles.

'i would but WHY have writing at ALL?' i scream.

'all right, settle down now,' says thakuru looking around to see if anybody's noticed us.

'why can't an exhibition say for once 'here's some art, enjoy yourselves bitches!''

'calm down, i said,' says thakuru paying for us. 'time to go.'

'i mean, you see what i mean...' i say, following thakuru down the stairs.

'YES, man, YES!'

0 notes

Text

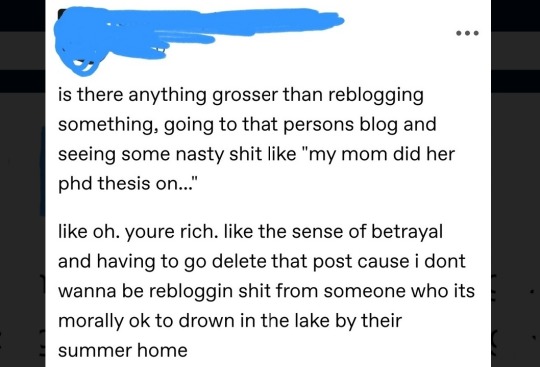

y'all ever see a take so maliciously dumb you don't even know where to start?

anyway I've been thinking about this post for *days* so I've decided y'all have to see it with your eyes too

*edit* y'all I shouldn't need to say this, but do not attempt to track this person down or harass them or interact with them. we can discuss a dumb concept without dogpiling some random whoever on the internet

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

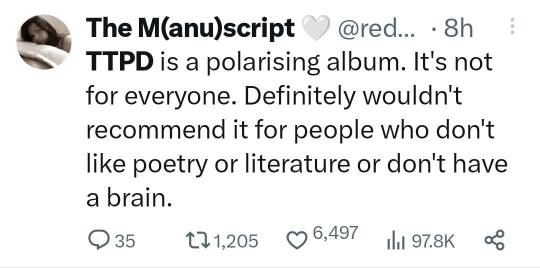

and are the poetry or literature or brains in the room with us right now?

#anti taylor swift#anti intellectualism#MAN everytime i think someone couldn't possibly say something stupider than this some swiftie comes along and pulls this garbage#OP IS AN EX SWIFTIE. BY THE WAY

688 notes

·

View notes

Text

don't complain about anti-intellectualism when people ask for simplified language, or ask you what something means. simplified language can help neurodivergent/intellectually disabled people, people without much formal education, and people who aren't fluent in whatever language you are using

anti-intellectualism is when governments and other powerful institutions try to silence teachers, scientists, artists, among others, because they don't want people to question their power or learn things that those in power disagree with

two very different things

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

a book blog: I am against anti-intellectualism and the way consumerism has overtaken modern literature

me: cool! me too! so-

the blog: yeah idk why these bougeois tiktokers who shop at BOOK STORES have the gall to not love BOOKS MADE FOR GROWN UPS instead of their stupid little romance and fantasy books like I'd rather read something that CHALLENGES MY BRAIN as leisure everyday instead of the homogenous mess that of consumable media like I may not be smart but I still read SHAKESPEARE for fun and so-

#yall know who#anti intellectualism#anti intellectual#intellectualism#intellectual#books and literature#books#book blog#ya books#booktok#bookish#consumerism#publishing

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

i don't understand simple economic concepts but that's okay because it's just #girl maths and i love being lazy but that's fine because it's my #girl job and this movie was complicated until i replaced nuclear war with the idea of me losing my favourite lipstick thank god for explanations for the #girls and yes i have an eating disorder but don't worry it's just #girl dinner and men love the roman empire but #girls care more about pop culture... like omfg are you people hearing yourselves?!??!

#i will single handedly bring down bimboism if thats what it takes like ENNOUGHHHGHGHGHHGHG#sorry like as women can we please not encourage this bizarre wave of anti intellectualism#shakes you by the shoulders Men want you to be pliable and stupid and silly and ignorant so you must not !!!!!!#you absolutely must not!!!

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

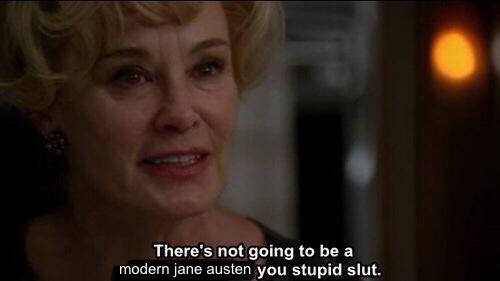

“colleen hoover is the new modern day jane austen” “emily henry is the new modern day jane austen” “tessa bailey is the new modern day jane austen”

#jane austen#booktok#anti intellectualism#sorry you guys don’t know what you’re talking about!! couldn’t be me!!#xoxo gossip belle#belle going unhinged

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

does anyone have some evidence/sources for “newton didn’t discover anything, he read indian scientists”? when i google it i find some vaguely indian-nationalist sources talking about how indian scientists (either brahmagupta II or bhaskaracharya) had discovered gravity 1000 years earlier. it definitely seems to be the case that the mathematician brahmagupta wrote about earth having an attractive force that makes things fall down, but (1) did he mathematically model it? i thought that was one of newton’s big innovations, building on earlier european and islamic theories about gravity, and (2) did newton know about or read brahmagupta? people independently come up with the same ideas all the time, there’s enough credit to go around

#seeing this claim without nuance or explanation in an otherwise amazing thread was the tipping point toward not reblogging it#the hall of fame#i don’t think this is anti intellectualism i think it’s just clickbaity soundbite pophist

10K notes

·

View notes

Text

Think I have to take classes all summer….lol

0 notes

Text

say it with me everybody: personal health is completely immaterial to morality, including mental health. leading a mentally unhealthy lifestyle (or what you perceive as a mentally unhealthy lifestyle) does not a bad person make. no one has to socialize, exercise, have healthy coping mechanisms, or lead (what you perceive as) a fulfilling life with fulfilling hobbies in the same way that no one has to go to the doctor to get a broken bone reset. both of those types of management of personal health are likely to be beneficial to the individual, but they are in no way moral requirements or debts owed to society. they do not actually say anything about a person's principles, personality, or actions towards others. additionally, people know themselves and their own situations better than you do. maybe a person judges that the physical and financial toll of going to the doctor outweigh the benefit of getting their bone reset, maybe a person just does not have the capacity to develop healthy coping mechanisms at this point in their life, and yes, maybe a person feels like they are totally fulfilled by "media based" hobbies alone and would feel no difference in their life if they picked up a loom. just like. let people be sick without accusing them of being representative of the lazy, degenerated state of modern society.

#marina marvels at life#there's a way people on here have been talking about ai/tiktok/movies/anti intellectualism/media hobbies/self care that all jives together#that just. really icks me out.#sometimes it comes through pretty transparently with people claiming that you must have regular sex to be a healthy/good person#or conversely that people are more sex crazed now than they've ever been and it's destroying literacy or whatever#or that cheating at school is scandalously immoral and only 'soft brained' bad people would do it#or that collectivism means you have to dress the right way and feel the right way and talk the right way#because your actions affect Others and you might upset someone or give off bad messages if you wear a crop top or are too sad#but a lot of the time it's just this strange plausibly-deniable tone I keep encountering that crept up some time in like 2021 I think#like. am I going crazy here or has anyone else been feeling this?

896 notes

·

View notes