#although i can understand him prioritizing saving zuko

Text

i lied it’s more ATLA Time!

Specifically an idea that came to me last night: one where Zuko does not survive the blizzard after the Water Tribe sibs retrieve Aang.

Let to freeze? Katara hit that much harder? Refused aid while conscious and ended up dying?* You decide.

The key here is that post-Yue, Iroh is increasingly frantic trying to retrieve his surrogate son before the locals’ good favor runs dry. Pakku agrees to look because you don’t have time for this, Iroh, Dragon of the West, get out! And Iroh agrees.

And receives correspondence.

If Zhao survived the fish, he sure as hell does not survive Iroh.

(Remember, he was running when Zuko waylaid him, forcing him into a fight and essentially stalling him.)

Iroh is a smart man, and a wise man, now. He grieves.

He does not lay the blame, truly, at the feet of children forced to defend themselves.

Iroh goes home back to the Fire Nation, and deals with the one who is to blame.

Now we have a world with no Ozai, just Iroh and maybe Azula (Azula survived Ozai’s court - it seems safe to assume she’s smart enough to know whether she can survive Iroh’s). I’ll come back to Azula later.

Iroh takes the throne. What else can he do?

So now the world is thrown, the Fire Lord suddenly dead, the new one being the Dragon of the West and also suing for peace.

Does Iroh, the White Lotus Grandmaster, think of the Fire Nation as he moves forward? Or just of the world?

And, of course, for world balance what do you need? That’s right! The Avatar!

So the Gaang, likely short a Toph but plus a few invested adults, goes to the Fire Nation! Yay?

(They may not have really known him before, he may have just been a sidenote in Zuko’s attacks, but they slowly recognize him and you can SEE the dread sinking into them.)

Bonus: The Gaang flitting about the countryside (far from court), only to find that huh, Fire Nation citizens are people, too. And huh, some of them have been hurt by the war just as badly as anyone else**. And huh, things haven’t, um. Really improved for them. But the world’s in better shape! But also the Gaang finds themselves passing out cash and food to kids younger than them in what they thought of as an enemy nation, but world balance, but-

If Azula wisely bounces that leaves potential for her to come back and try to murderlize Iroh at any poetic point (neither the Eclipse nor the Comet have happened probably, after all). Even if you don’t subscribe to Azula caring about her brother at all, I think she’d still be pretty damn mad - in canon she doesn’t really seem to care about actually ruling so much as what it means for her and her family situation (she’s better than Zuko; and Ozai approves). I think she has plenty of impetus for some really creative revenge plots.

*This last option is best for Zuko possibly reappearing later down the line (and Pakku not finding a body means more for an Iroh who’s aware of just how borderline unkillable his nephew is...)

**While ppl from the other nations definitely suffered in great numbers and greater trauma, a world and perpetual culture of war is harmful even to people who seem fine (just look at Azula in canon.... She’s exactly what the Fire Nation and Ozai made her to be, a weapon in a 14-year-old’s form, and we know what happens to her...)

#angst warn ig#death mention#elk text#1st#September#2021#September 1st 2021#atla#ive been reading muffinlance's Towards the Sun recently btw#which has def influenced the tone of this#personally i think azula cares for her brother as much as she's able to care about anyone after her completely messed up childhood#becoming the perfect tool for a megalomaniac warlord doesn't leave much room for sincere emotional connection!#iroh saying 'she's crazy and needs to go down was supposed to be more about how zuo shouldn't think iroh wouldn't stop HIS own sibling#but he truly seems to lack any care for his niece in canon#although i can understand him prioritizing saving zuko#he really couldn't have helped both at the same time#without erasing ozai anyways#also!#thinking about that death scene!#i feel like sokka would be the most aware of how the cold kills and that you shouldn't leave someone to die like that#i feel like there's something i've read abt like#either finish the job or help them but don't just LEAVE them#and if you can't finish the job you DEFINITELY shouldn't leave him#yes zuko was a threat but still#also think about how Aang feels about any of the actual death options#he might have to live with the fact that his best friend and crush is also a killer! :)#probably remorseless at that! :)#im not saying she's cold but i can't see her regretting the death of someone she thought was 'evil' after he kidnapped Aang IN A BLIZZARD#now if she learns more on the other hand...#of zuko himself or just that the fire nation has real people in it .... :)

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

I deeply appreciate how ATLA depicts all the main characters responses to trauma. Aang’s, for me, however, stands out for its rareness in media. And we are not hammered over the head with the idea that Aang (or any other characters) repeatedly act certain ways because of a single traumatic event. Sure, there are key moments in our lives when a certain event comes to the forefront, but no one experiences the world as constant flashbacks. Rather, we see only in retrospect the way our sarcastic sense of humor or our heightened friendliness were protective responses to a deep emotional injury.

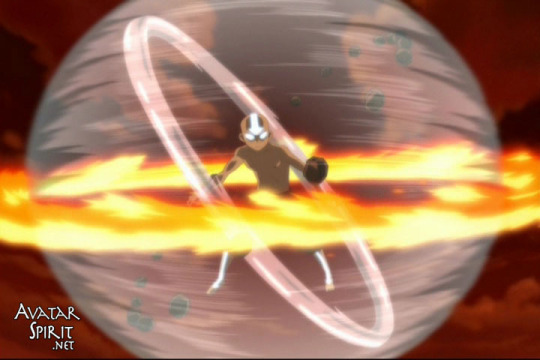

Being able to understand Aang’s approach to loss is essential for the show. The structure of the series is founded on his arc (despite an incredible foil provided by Zuko). Our little air nomad initially confronts the loss of his people with a full-on meltdown in the episode “The Southern Air Temple,” where Katara’s offering of familial belonging soothes him. But this kind of outburst is not Aang’s primary response (and actually the literally out-of-character apocalyptic tantrums align with Aang’s overall process of grieving). Instead of constantly brooding (hey Zuko!), Aang leans heavily toward the monk’s pacifist teachings and toward his assumed destiny “to save the world.” He becomes overtly accommodating and joyful, constantly trying to see “the good” in everything with a perfectionist’s zeal. This is not to ascribe his bubbliness only to his trauma. Rather, he comes to emphasize this part of his personality for reasons related to the negative emotions he struggles to face.

Book 1: Water

In the first season, Aang is simply rediscovering his place in the world. “Water is the element of change. The people of the water tribe are capable of adapting to many things. They have a sense of community and love that holds them together.” This is vital to Aang as he initially faces his experience. He won’t get through this if he is not prepared for his life to change. Even if he hadn’t been frozen for 100 years, his world would never be the same. This fact involves eventually finding new people that he feels safe with. After such a massive loss, he’s learning who to trust, and also often making mistakes; not only does he find Sokka and Katara (and I’d argue he’s actually slow to truly open up to them), this is the season where he helps save a fire nation citizen who betrays him to soldiers, befriends the rebel extremist Jet, and attempts to befriend an actively belligerent Zuko (his moral complexity had only JUST! been revealed to the kid!). He’s constantly offering trust to others and seeking their approval in opposition to the deep well of shame and guilt he carries as a survivor of violence.

This is also the season where Aang swears off firebending after burning Katara in an overeager attempt to master the element (one will note how fire throughout the series is aligned with, above all else, assertiveness and yang). Aang is so eager to be seen as morally good to others that he refuses to risk any possible harm to them. And asserting himself carries a danger, in one sense, that he might make a mistake and lose someone’s positive regard, and, in another sense, that he is replicating the anger and violence he’s witnessed. He has no relationship to his anger at this stage of his grief, so it comes out uncontrollably, both in firebending and the Avatar State. It’s through the patience of his new family that he can begin to feel unashamed about his past and about the ways his shame is finding (sometimes violent) expression in the present.

Book 2: Earth

In the second season he begins to trust himself and stand his ground. Earth, after all, is the element of substance, persistence, and endurance. The “Bitter Work” episode encapsulates how Aang must come to a more sturdy sense of his values. First, there is the transition of pedagogical style. While Katara emphasized support and kindness, Toph insists on blunt and threatening instruction, not for a lack of care towards Aang. Instead, it’s so Aang learns how to stop placing the desires of others above his own--to stop accommodating everyone else above his own needs. Toph taunts Aang by stealing one of the few keepsakes from the monastery that he holds onto. This attachment to the lost airbending culture is echoed in the larger arc with Appa. And, by the end of this episode, it is Aang’s attachment to Sokka that allows him to stand firm. This foreshadows the capital T Tragic downfall in the “Crossroads of Destiny.” Aang gives up his attachment to the other member of his new found family, Katara, despite his moral qualms. Although he has access to all the power of the Avatar state, his sacrifice is not rewarded. Season 2 illustrates Aang coming to terms with his values. He is learning about what he stands for, what holds meaning to him.

Understanding himself also includes integrating his grief, and there’s a lonely and dangerous aspect to that exploration. We see Aang’s anger and hopelessness over longer stretches rather than outbursts in this season. It’s hard to watch and hard to root for him. That depressive state leads to actions that counter his previous sense of morality, as he decisively kills an animal, treats his friends unkindly, and blames others for his loss. Letting these harsher feelings emerge is an experiment, and most people discover their boundaries by crossing them.

Finding ways to hold compassion for himself, even the harm he causes others, is the other side of this process. Our past and our challenging emotions are a part of us, but they are only a part. Since Aang now has a strong sense of community and is learning to be himself rather than simply seeking validation, we also see him having more healthy boundaries with new people. He’s no longer befriending villains in the second season! He’s respectful and trusting enough, but he’s not putting himself in vulnerable situations nor blindly trusting everyone. Instead, he’s more likely to listen to his friends’ opinions or think about how the monks might’ve been critical towards something (they’re complaints about Ba Sing Se, for example). By knowing what he cares for, he can know himself, the powerful, loving, grief-struck monk. And he can trust that, though he might not be everyone’s favorite person, he does not need to feel ashamed or guilty for who he is or what he’s been through.

Book 3: Fire

However, despite a sense of self and a sense of belonging, Aang and the group still find themselves constantly asking for permission throughout their time in Ba Sing Se. It’s in the third season, Fire, that initiative and assertiveness become the focus. And who better to provide guidance in this than the official prince of “you never think these things through,” Zuko. It’s no longer a time for avoidance or sturdy defensiveness. It is the season of action. Fire is the element of power, desire, and will, all of which require us to impact others. We see the motif of initiative throughout the season: the rebels attempt to storm the Firelord on the Day of the Black Sun; Aang attempts to share his feelings and kiss Katara; Katara bends Hama and a couple of fire nation soldiers to her will. In each of these examples, the initiators face disgrace. Positive intent does not bring forth success, by any means, only more consequences to be dealt with. This is perhaps Aang’s biggest challenge. He is afraid that his actions will fail, or worse, they will succeed but he will be wrong in what he has chosen. The sequencing in the series, here, is important. We have already seen how Aang has worked to care for (and appreciate) the well-being of others and how he has learned to care for his own needs. With this in mind, he should be able to trust that his actions will derive from these wells of compassion. But easier said than done. Compassion can also trap him into indecision, hearkening back to his avoidant mistake in the storm, in which the whole mess began. Aang’s internal conflict, here, becomes more pronounced as the finale draws nearer.

I think it’s especially significant that we witness Aang disagreeing with his mentors and friends. He must act in a way that will contradict and even threaten his sources of support if he is to trust his own desires. Even the fandom disagrees about the choice Aang makes, which further highlights the fact that making a decisive choice is contentious. There is no point in believing it will grant you love or admiration or success. For someone who began (and spent much of) the series regularly sacrificing himself just to bring others peace, Aang’s decision to prioritize his own interests despite the very explicit possibility of failure is the ultimate growth his character can have and the ultimate representation of him processing his trauma. (This arc was echoed and made even more explicit in many ways with Adora in the She-ra finale.) The last significant time Aang followed his desire, in his mind, was when he escaped the Air Temple in the storm. To want something, to trust his desire and act on it, is an act of incredible courage for him, and whether it succeeded or failed, whether anyone agrees or disagrees with it, it offered Aang a sense of peace and resolution. Now I appreciate and love Zuko’s iconic redemption arc, but Aang’s subtler arc, which subverts the “chosen one” narrative and broke ground to represent a prevalent emotional experience, stands out to me as the foundation for the show I love so much.

#aang#avatar the last airbender#trauma#ptsd#cptsd#atla#atla meta#zuko#redemption arc#adora#spop#catradora#catra#also no one will read this far in the tags but this is phoebe buffay's arc on friends

6K notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you think Aang and Katara would still end up together if Katara killed her mother’s killer? How would that affect their relationship?

Hey anon! Sorry it took me a while to answer your question, but the truth is that there is no clear trajectory regarding Kata/ang in this situation, especially when we take into account that Kata/ang in the show canon was abrupt and significantly underdeveloped. More specifically on Kata/ang, both Katara and Aang’s arcs were twisted to accommodate for their endgame romance, but while Katara’s arc reaches its culmination by the end of the Final Agni Kai, Aang’s character had become inconsistent in its direction throughout all of season 3.

As such, two conflicting outcomes can result from this hypothetical scenario — one outcome which upholds Aang’s flaws and stagnated growth, or another outcome which forces Aang into growing, accepting, and understanding, as was the original intent behind his character.

From a broader context, Aang’s entire journey since he woke up in the iceberg has been about him reconciling his airbender and Avatar identity, and by the end of season 2 when he is with the guru, Aang is on the cusp of fully accepting his Avatar responsibilities, of letting go of his selfish attachments (or in other words, his blinding biases).

Except Aang cannot let go as he hoped he would be able to. Because his attachment to Katara is selfish, but beyond that his attachment to Katara is a replacement for his attachment to the Air Nomads — and it draws him away from his duties as the Avatar, causing him to embrace an ideal he does not comprehend. After all, the Air Nomads were not perfectly pacifistic either.

Still, just as Aang refuses to recognize the complexity in the Air Nomads’ legacies, dismissing what he may deem as an act of violence, Aang refuses to recognize the complexity to Katara’s rage and compassion, to her violent and protective nature. In my meta “On Ideals and Idealization,” I elaborate on Aang’s idealization of Katara:

Aang loves Katara, yes, but he is in love with an idealized version of her. In his mind, he holds close the idea of a gentle Katara, a smiling Katara, a compassionate and all-loving Katara. Even though he has seen her darkest moments when she bloodbends Hama - arms bent in disjointed angles, fingers curled as if manipulating puppet strings - it does not tarnish his image of her because, at this moment, she is not the persecutor, but the persecuted.

After her experience with Hama, Aang is there to comfort her and help her come to terms with the terrifying power she now possesses. With her face streaked with tears and eyes widened with horror, it is clear that this is a power that Katara does not want, that it has been thrust onto her against her own will.

The conclusion that Aang draws from this is that Katara’s inner darkness is a separate entity from her inner light, and he perceives this acquired part of her as a blemish on her inherent goodness. As such, in “the Southern Raiders,” when he witnesses how Katara’s anger and grief drive her to hunt down her mother’s killer, he equates Katara seeking closure to Katara succumbing to darkness, tainting her purity and compassion in the process.

Thus, given Aang’s reaction to Katara’s bloodbending, he may be inclined to love her in a piteous, nearly-obligatory manner. He’ll love her as the victim who lost sight and control and he’ll love her as a being of compassion and pacificity, but nothing more. Just like in the Southern Raiders, he may magnanimously grant Katara his forgiveness and his continued love even when she never asked for it. And in the end, Aang and Katara will kiss on the balcony of Iroh’s tea shop, only this time it’s not only “the hero winning the girl,” but “the bright and cheerful boy fixing the broken girl” as well.

This is the ending where Aang clings onto idealization even when it renders him a hypocrite, in the same way he is a hypocrite for shouting at his friends for pushing him to kill Ozai when it is implied he killed thousands at sea in the Siege at the North Pole.

This is the ending where he does not grow.

Note: Aang retreating into a ball of earth as a narrative parallel to the beginning of the series when he was encased in a ball of ice would have been much more powerful if only Aang entered the Avatar State through character growth rather than by the power of the Pointy Rock of Destiny (TM).

Now, let’s consider an ending where Aang’s perspective broadens rather than narrows and where Aang unroots himself from the past, pulling free from stagnance. Let’s consider a hypothetical scenario in which Aang finds out Katara killed Yon Rha. How may he react?

He may not be able to at first, too torn between his belief that Katara only uses violence as a last resort and the reality that Katara uses violence as a means of agency as well. Revenge corrupts; it is a stain that cannot be washed away. There is no reconciling Katara’s previous compassionate and loving nature with this dark path she has now chosen.

Except this is Katara he’s talking about, Katara who he loves and gave up the Avatar State for. Surely there’s a way to save her, right? Yes, just as Aang told Katara before she left, forgiveness is the answer. And while Katara may not have chosen forgiveness in the end, Aang can guide her by example.

The next day, he approaches her with the offer to exempt her from her wrongdoings.

Katara, tired and mournful, looks down at Aang.

“What was so wrong about what I did?”

Inside she is hurting. There is truth to what Aang said, that revenge is poisonous both to the victim and the perpetrator, but it is not poisonous for the reasons he thinks it is. As George Orwell writes in his essay, “revenge is an act which you want to commit when you are powerless and because you are powerless: as soon as the sense of impotence is removed, the desire evaporates also” (Revenge is Sour). There’s no doubt that Yon Rha was despicable, and there’s only a little doubt in saying that his punishment should fit his crime — the only regret Katara may have here is that killing Yon Rha is a meaningless act, for she has already gained power over him in every meaning of the word. Revenge is only a gateway to senseless violence and hatred; it is not a slope from which there is no recovery, and given Katara’s emotional intelligence, she likely has or will recognize this. Although she may feel regret, she needs no one’s forgiveness.

Aang is shocked. “But violence is never the answer,” he stands by, he pleads by. His voice grows quieter. “You know that… you knew that, didn’t you?”

Katara answers him, but it’s all a blur. She says something about agency, protection, and justice. He remembers something about that too, about the fury that burned in her eyes when she declared, “I will never, ever, turn my back on the people who need me!” Then there was the hostility simmering in her glare towards Zuko, the way she muttered that she didn’t trust him, not when he could still hurt them — hurt Aang — again.

Because Katara’s anger and compassion do not simply split themselves into two identities. Instead, they coexist and coalesce into one. They drive each other; they feed into each other; they are two sides of the same coin.

Excerpt from my meta Rage, Compassion, and the Bridge in Between

The beloved ideal of Katara — the one that he thought was on the verge of being tainted, the one that never existed — shatters. But just because it’s broken doesn’t mean Aang doesn’t want to fix it. So in the days leading up to Sozin’s Comet, he tries to pick up the fragments to the Katara-he-knew and piece them together again, all the while avoiding Katara’s mournful (yet resolved) stare. He ignores the way Zuko and Katara share glances with a heaviness as if they were the only two people in the world, full of some significance he cannot grasp. Still, it haunts him like the way Zuko’s touch lingers on Katara’s shoulder or Katara’s hand brushes Zuko’s briefly whenever they don’t think anyone’s looking, reflecting a togetherness escaping loneliness.

But there’s no answer that arrives quick enough to save Aang from his doubt and confusion. All too soon, Sozin’s Comet is upon them, and Aang wanders to another world on the lion turtle's back — but this time when he listens to the past Avatars’ advice, his perspective undergoes a paradigm shift.

They are right. The Air Nomads that he prioritized, that blinded him to his duties — they do not exist. Their love is still there, pure and human but not all-encompassing, tucked in the corner of his heart. And Katara was the same. She was and is not all-loving or all-compassionate or all-anything, really, because she is more human than that.

This time Katara’s image shatters again. But Aang does not follow the falling pieces to the ground, desperate to find them and force them together again. No, he sees past the remains and sees Katara for who she is. For who she wants to be. For who she can be (around someone else), when she’s not compelled to take on the caretaker role just for him.

(And he thought he was so generous, offering to forgive him. But it was never his forgiveness to give in the first place.)

Aang lets go of his last attachment.

The last airbender lives on, but so does the Avatar.

#atla#atla meta#anti kataang#anti kataang meta#zutara#aang#katara#anti aang#of sorts?#my bated breath's posts#my bated breath analyzes#i kind of rewrote aang's arc in the finale in my mind and a little bit of that slipped through#anon you asked a hard question so i gave you a 1.5k+ meta in response#i hope it's everything you ever hoped it could be#anonymous ask#ask#is tumblr hiding this post from the tags again?

379 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mako Appreciation Post

Mako is generally not appreciated for what he is and is kind of hated. So, I wanted to write this post to appreciate him and show how he is a great character and how much depth he has. I want to write why he is one of my favourite characters in the franchise.

First of all, let's start with his childhood. Mako's parents were killed in front of his eyes, when he was eight, by a firebender. Imagine seeing the murder of your own parents.

Being the elder brother, with no knowledge of his relatives, he was forced to take on adult responsibilities from that point on, depriving him of the majority of his childhood. He took on the parental role for Bolin from the age of eight. Let that sink in. This impacted Mako largely and he became stoic, brooding, aloof and indifferent.

He never allowed this to discourage him though - he did whatever was necessary in order for their survival. Even if it meant dipping his toes into shady criminal activities, Mako prioritized only making sure they'd be able to survive another night. He always protected his brother. Mako used to see it as his sole job to provide for him and keep him safe.

Partially due to Mako doing his best to shield Bolin from the true cruel nature of the world after their parents' death, Bolin's positive nature never left him. We can say it is because of Mako that Bolin is goofy and "likeable". He let Bolin be a child.

Mako is similar to Katara in that both have mothers killed by firebenders, a memento of a parent (Mako's father's scarf and Katara's mother's necklace), both also raised their brothers as a parent would do, a personality contradictory to that of their brothers, and both were love interests of the Avatar of their time.

Next, let's look at the romance part for which he is hated the most. The first thing to note is that he cared for both Asami and Korra, even when he was just friends with them. Also, he never made the first move. It was Korra (in season 1) and Asami (in season 2) who kissed him first. People often say that "Mako did this wrong thing, that wrong thing" but fail to recognise that although not being the sole one wrong he apologizes. He is very bad at relationships and Asami and his cousin, Tu best describe this-

Tu: “It seems like you're so afraid to disappoint anyone that you end up disappointing everyone.”

Asami: “Mako has never been the most "in touch with his feelings" guy.” (probably because of his rough childhood)

But Mako does care about them. Some examples are – he goes with Korra to fight Amon, he consoles Asami when she lost all her supplies, he is concerned when Suyin is taking out the poison from Korra’s body, etc.

The thing here is that most of his actions can be justified and he never did anything really horrible.

Although he is awkward at the beginning of season 3, he eventually gets over it and remains good friends with both Korra and Asami. He cares about them as a friend and we can see it throughout season 3 and 4. He does share a platonic relationship with them.

In short, Mako is a tries-to-be-good-but-not-so-good boyfriend but a great friend and brother.

Also, Mako is very committed to his job. Whether he was a cop, a detective or a bodyguard, he took his job seriously and worked hard.

Another remarkable thing about him is that how good firebender he is although not having any formal training in it. He is a quick-thinker and tactical.

We also see him grow emotionally when he gave his father’s scarf to his grandma understanding that perhaps she needed it more than him.

And now let’s talk about his best scene in the whole series – When he was ready to sacrifice himself in order to stop Kuvira and save the city. This was an act of selflessness.

His character growth in the series is not as big as Korra or Zuko (and it doesn’t have to be) but he does grow just like any other ATLA/TLOK character.

In the end, Mako is a kind person on the inside. He's devoted to the people that are close to him, and you can count on him in any situation.

I don't know how someone can hate him or call him unlikable.

This is Mako from season 1 start who was insensitive to Korra,

And this Mako from season 4 end who said that he has got her back. (The best ending for two good friends.)

From Bryan’s “Korrasami is canon” post, it’s supposed to be that “Mako and Korra break the typical pattern and end up respecting, admiring, and inspiring each other.”

35 notes

·

View notes